Types of Intelligence and Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

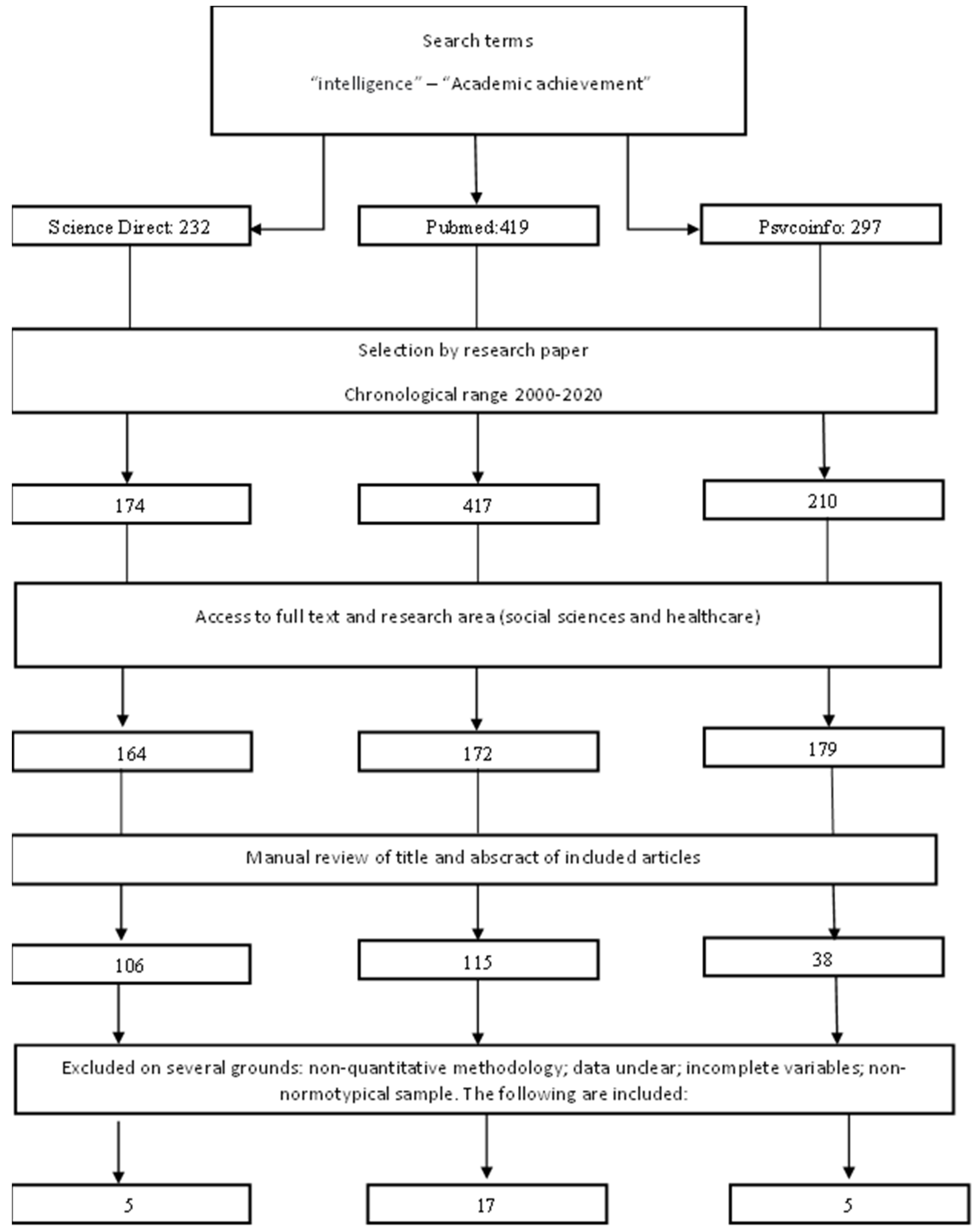

2. Method

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Description

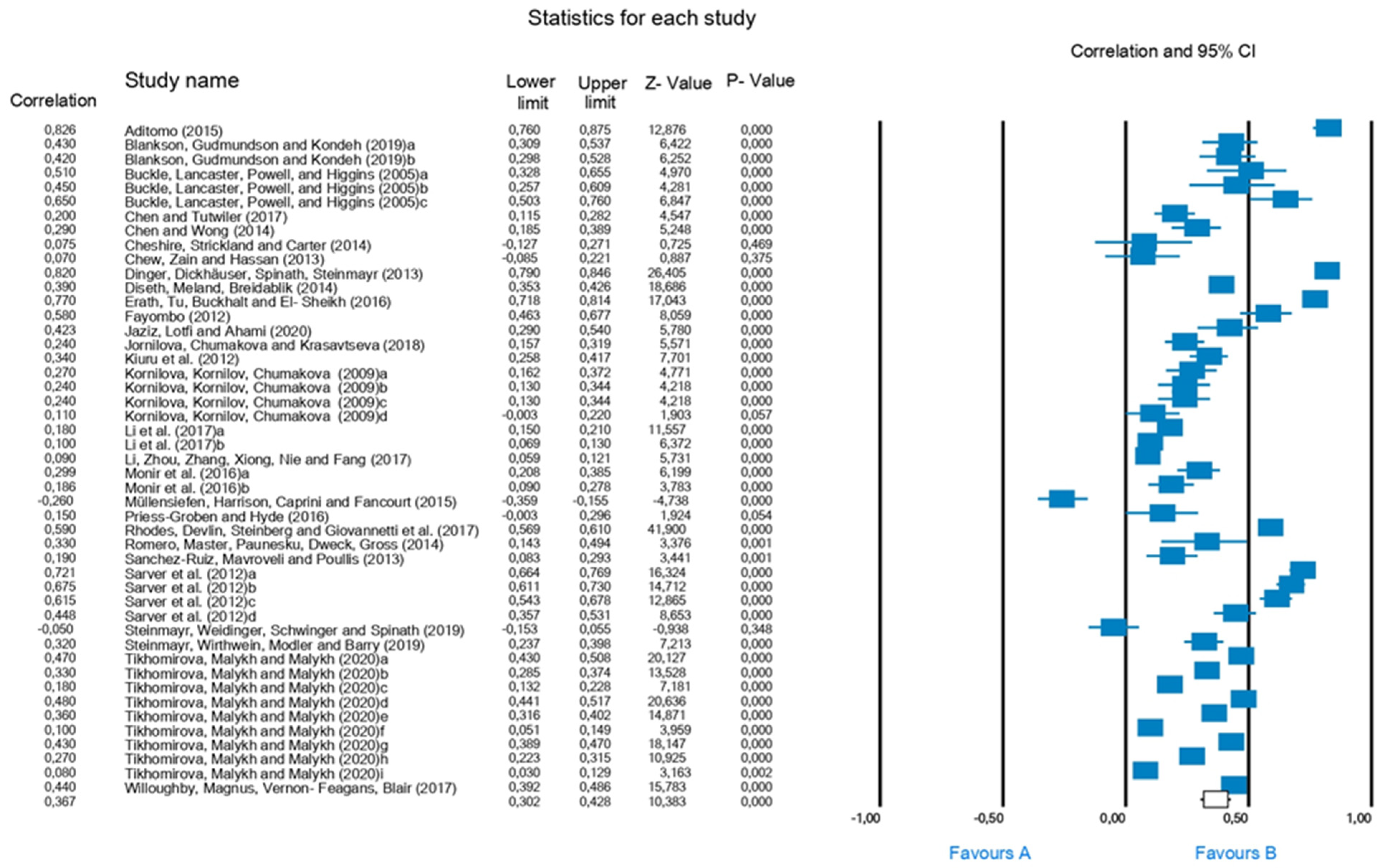

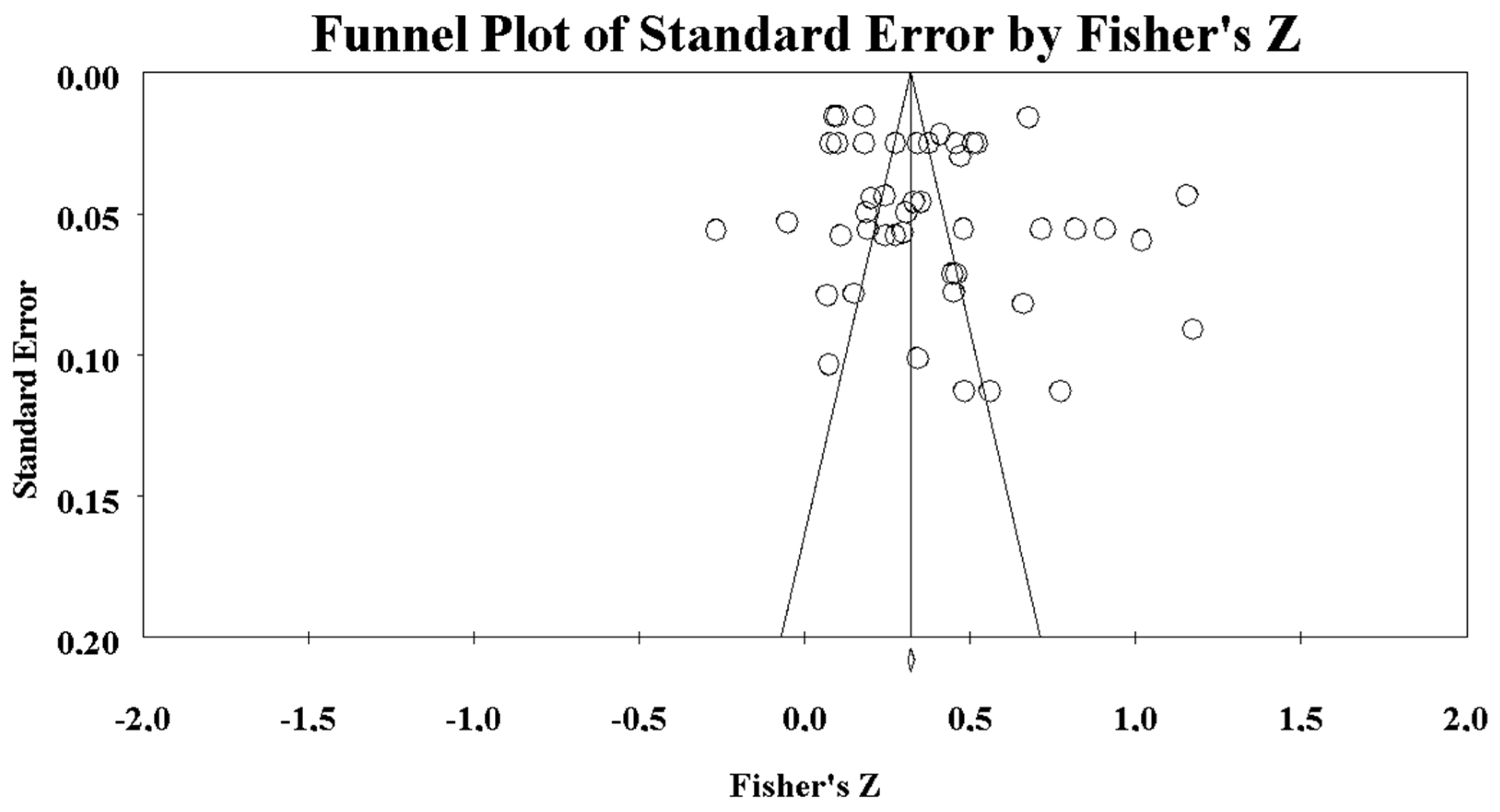

3.2. Statistical Analysis

3.3. Moderating Variables and Meta-Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aditomo, Anindito. 2015. Students’ response to academic setback: “Growth mindset” as a buffer against demotivation. International Journal of Educational Psychology 4: 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alquichire R, Shirley Lorena, and Juan Carlos Arrieta R. 2018. Relación entre habilidades de pensamiento crítico y rendimiento académico. Voces y Silencios. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación 9: 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Hafeez Ullah, Aamir Saeed Malik, Nidal Kamel, Weng-Tink Chooi, and Muhammad Hussain. 2015. P300 correlates with learning & memory abilities and fluid intelligence. Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation 12: 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariza, Carla Patricia, Luis Ángel Rueda Toncel, and Jainer Sardoth Blanchar. 2018. El rendimiento académico: Una problemática compleja. Revista Boletín Redipe 7: 137–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ausina, Juan Botella, and Julio Sánchez-Meca. 2015. Meta-Análisis en Ciencias Sociales y de la Salud. Madrid: Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- Balkis, Murat. 2018. Desmotivación académica e intención de abandono escolar: El papel mediador del logro académico y el absentismo. Asia Pacific Journal of Education 38: 257–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankson, A. Nayena, Jessica A. Gudmundson, and Memuna Kondeh. 2019. Cognitive predictors of kindergarten achievement in African American children. Journal of Educational Psychology 111: 1273–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, Douglas G. 2006. Robust Confidence Interval for a Ratio of Standard Deviations. Applied Psychological Measurements 30: 432–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, Juan, and Hilda Gambara. 2002. Qué es el Meta-Análisis. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva. [Google Scholar]

- Buckle, Sarah K., Sandra Lancaster, Martine B. Powell, and Daryl J. Higgins. 2005. The relationship between child sexual abuse and academic achievement in a sample of adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Child Abuse & Neglect 29: 1031–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, John. 1992. ¿Qué es la inteligencia? In ¿Qué es la Inteligencia? Enfoque Actual de su Naturaleza y Definición. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg and Douglas K. Detterman. Madrid: Pirámide, pp. 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Castejon, Juan L., Antonio M. Perez, and Raquel Gilar. 2010. Confirmatory factor analysis of Project Spectrum activities. A second-order g factor or multiple intelligences? Intelligence 38: 481–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, Raymond B. 1963. Theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence: A critical experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology 54: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jason A., and M. Shane Tutwiler. 2017. Implicit theories of ability and self-efficacy. Zeitschrift für Psychologie 225: 127–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Wei-Wen, and Yi-Lee Wong. 2014. What my parents make me believe in learning: The role of filial piety in Hong Kong students’ motivation and academic achievement. International Journal of Psychology 49: 249–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheshire, Michelle H., Haley P. Strickland, and Melondie R. Carter. 2015. Comparing traditional measures of academic success with emotional intelligence scores in nursing students. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing 2: 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Boon How, Azhar Md Zain, and Faezah Hassan. 2013. Emotional intelligence and academic performance in first and final year medical students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education 13: 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés Pascual, Alejandra, Nieves Moyano Muñoz, and Alberto Quílez Robres. 2019. Relación entre funciones ejecutivas y rendimiento académico en educación primaria: Revisión y metanálisis. Frente. Psicol. 10: 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deary, Ian J., Steve Strand, Pauline Smith, and Cres Fernandes. 2007. Intelligence and educational achievement. Intelligence 35: 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dersimonian, Rebecca, and Nan Laird. 1986. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 7: 177–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinger, Felix C., Oliver Dickhäuser, Birgit Spinath, and Ricarda Steinmayr. 2013. Antecedents and consequences of students’ achievement goals: A mediation analysis. Learning and Individual Differences 28: 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diseth, Åge, Eivind Meland, and Hans Johan Breidablik. 2014. Self-beliefs among students: Grade level and gender differences in self-esteem, self-efficacy and implicit theories of intelligence. Learning and Individual Differences 35: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, Matthias, George Davey Smith, and Andrew N. Phillips. 1997. Meta-analysis: Principles and procedures. Britihs Medical Journal BMJ 315: 1533–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Jaziz, Anas, Said Lotfi, and Ahmad O. T. Ahami. 2020. Interrelationship of physical exercise, perceptual discrimination and academic achievement variables in high school students. Ann Ig 32: 528–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enea-Drapeau, Claire, Michèle Carlier, and Pascal Huguet. 2017. Implicit theories concerning the intelligence of individuals with Down syndrome. PLoS ONE 12: e0188513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engin, Melih. 2017. Analysis of Students’ Online Learning Readiness Based on Their Emotional Intelligence Level. Universal Journal of Educational Research 5: 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erath, Stephen A., Kelly M. Tu, Joseph A. Buckhalt, and Mona El-Sheikh. 2015. Associations between children’s intelligence and academic achievement: The role of sleep. Journal of Sleep Research 24: 510–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayombo, Grace A. 2012. Relating emotional intelligence to academic achievement among university students in Barbados. The International Journal of Emotional Education 4: 43–54. Available online: https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/6141 (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Friese, Malte, and Julius Frankenbach. 2020. p-Hacking and publication bias interact to distort meta-analytic effect size estimates. Psychological Methods 25: 456–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Howard. 1985. The Mind’s New Science: A History of the Cognitive Revolutión. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Geary, David C. 2011. Cognitive predictors of achievement growth in mathematics: A 5-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology 47: 1539–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, Gerard A., Peter Isquith, Steven C. Guy, and Lauren Kenworthy. 2017. Santamaria (Adapters), BRIEF-2. Evaluación Conductual de la Función Ejecutiva. Edited by María Jesús Maldonado, María de la Concepción Fournier, Rosario Martínez-Arias, Javier González-Marqués, Juan Manuel Espejo-Saavedra and Pablo Santamaría. Madrid: TEA Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, Daniel. 1996. Inteligencia Emocional. Barcelona: Kairós. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, Daniel. 1999. La Práctica de la Inteligencia Emocional. Barcelona: Kairós. [Google Scholar]

- González, Gustavo, Alejandro Castro Solano, and Federico González. 2008. Perfiles aptitudinales, estilos de pensamiento y rendimiento académico. Anuario de Investigaciones 15: 33–41. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3691/369139944035.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2020).

- Higgins, Julian P. T., and Sally Green. 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. London: The Cochrane Collaboration. Available online: www.cochrane-handbook.org (accessed on 4 January 2020).

- Higgins, Julian P. T., Craig Ramsay, Barnaby C. Reeves, Jonathan J. Deeks, Beverley Shea, Jeffrey C. Valentine, Peter Tugwell, and George Wells. 2013. Issues relating to study design and risk of bias when including non-randomized studies in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Research Synthesis Methods 4: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Ying-yi, Chi-yue Chiu, Carol S. Dweck, Derrick M-S. Lin, and Wendy Wan. 1999. Implicit theories, attributions, and coping: A meaning system approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 588–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, John E., and Frank L. Schmidt. 2004. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings. New York: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Jak, Suzanne, and Mike W-L. Cheung. 2020. Meta-analytic structural equation modeling with moderating effects on SEM parameters. Psychological Methods 25: 430–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, Ronnel B., Dennis M. McInerney, and David A. Watkins. 2012. How you think about your intelligence determines how you feel in school: The role of theories of intelligence on academic emotions. Learning and Individual Differences 22: 814–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuru, Noona, Katariina Salmela-Aro, Jari-Erik Nurmi, Peter Zettergren, Håkan Andersson, and Lars Bergman. 2012. Best friends in adolescence show similar educational careers in early adulthood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 33: 102–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornilova, Tatiana V., Maria A. Chumakova, and Yulia V. Krasavtseva. 2018. Emotional intelligence, patterns for coping with decisional conflict, and academic achievement in cross-cultural perspective (evidence from selective Russian and Azerbaijani student populations). Psychology in Russia: State of the Art 11: 114–33. Available online: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/index.php?article=7230 (accessed on 4 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kornilova, Tatiana V., Sergey A. Kornilov, and Maria A. Chumakova. 2009. Subjective evaluations of intelligence and academic self-concept predict academic achievement: Evidence from a selective student population. Learning and Individual Differences 19: 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegbaum, Katharina, Malte Jansen, and Birgit Spinath. 2015. Motivation: A predictor of PISA’s mathematical competence beyond intelligence and prior test achievement. Learning and Individual Differences 43: 140–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncel, Nathan R., Sarah A. Hezlett, and Deniz S. Ones. 2004. Academic performance, career potential, creativity, and job performance: Can one construct predict them all? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 86: 148–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidra, Kaia, Helle Pullmann, and Jüri Allik. 2007. Personality and intelligence as predictors of academic achievement: A cross-sectional study from elementary to secondary school. Personality and Individual Differences 42: 441–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Ping, Nan Zhou, Yuchi Zhang, Qing Xiong, Ruihong Nie, and Xiaoyi Fang. 2017. Incremental theory of intelligence moderated the relationship between prior achievement and school engagement in Chinese high school students. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, Christin, Rebecca Schneider, and Jörn R. Sparfeldt. 2018. Differential relevance of intelligence and motivation for grades and competence tests in mathematics. Learning and Individual Differences 65: 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Dasen, Lee A. Thompson, and Douglas K. Detterman. 2006. The criterion validity of tasks of basic cognitive processes. Intelligence 34: 79–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCann, Carolyn, Yixin Jiang, Luke E. R. Brown, Kit S Double, Micaela Bucich, and Amirali Minbashian. 2020. Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 146: 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín Andrés, A., and J. D. D. Luna del Castillo. 2004. Bioestadística para las Ciencias de la Salud. Madrid: Capitel Ediciones, SL. [Google Scholar]

- Molano, Olga Lucía. 2007. Identidad cultural un concepto que evoluciona. Revista Opera 7: 69–84. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4020258 (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Molero-Puertas, Pilar, Félix Zurita-Ortega, Ramón Chacón-Cuberos, Manuel Castro-Sánchez, Irwin Ramírez-Granizo, and Gabriel Valero-González. 2020. La inteligencia emocional en el ámbito educativo: Un metaanálisis. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology 36: 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monir, Zeinab M., Ebtissam M. Salah El-Din, Inas R. El-Alameey, Gamal A. Yamamah, Hala S. Megahed, Samar M. Salem, and Tarek S. Ibrahim. 2016. Academic Achievement and Psychosocial Profile of Egyptian Primary School Children in South Sinai. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences 4: 624–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, David, and Beau Gamble. 2020. Conducting a meta-analysis in the age of open science: Tools, tips, and practical recommendations. Advance online publication. Psychological Methods 27: 426–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllensiefen, Daniel, Peter Harrison, Francesco Caprini, and Amy Fancourt. 2015. Investigating the importance of self-theories of intelligence and musicality for students’ academic and musical achievement. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Navarro, Rubén Edel. 2003. El rendimiento académico: Concepto, investigación y desarrollo. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 1: 1–16. Available online: https://revistas.uam.es/index.php/reice/article/view/5354/5793 (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Nieto Martín, Santiago. 2008. Hacia una teoría sobre el rendimiento académico en enseñanza primaria a partir de la investigación empírica: Datos preliminares. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria 20: 249–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, Richard E., Joshua Aronson, Clancy Blair, William Dickens, James Flynn, Diane F. Halpern, and Eric Turkheimer. 2012. Intelligence: New findings and theoretical developments. American Psychologist 67: 130–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okwuduba, Emmanuel Nkemakolam, Kingsley Chinaza Nwosu, Ebele Chinelo Okigbo, Naomi Nkiru Samuel, and Chinwe Achugbu. 2021. Impact of intrapersonal and interpersonal emotional intelligence and self-directed learning on academic performance among pre-university science students. Heliyon 7: e06611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, Harsha N., and Michelle DiGiacomo. 2013. The relationship of trait emotional intelligence with academic performance: A meta-analytic review. Learning and Individual Differences 28: 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, Paul R. 2002. The role of metacognitive knowledge in learning, teaching, and assessing. Theory into Practice 41: 219–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plomin, Robert, and Ian J. Deary. 2015. Genetics and intelligence differences: Five special findings. Molecular Psychiatry 20: 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priess-Groben, Heather A., and Janet Shibley Hyde. 2017. Implicit theories, expectancies, and values predict mathematics motivation and behavior across high school and college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 46: 1318–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PRISMA. 2015. Grupo PRISMA-P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. British Medical Journal BMJ 349: g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quílez-Robres, Alberto, Alejandro González-Andrade, Zaira Ortega, and Sandra Santiago-Ramajo. 2021a. Intelligence quotient, short-term memory and study habits as academic achievement predictors of elementary school: A follow-up study. Studies in Educational Evaluation 70: 101020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quílez-Robres, Alberto, Nieves Moyano, and Alejandra Cortés-Pascual. 2021b. Motivational, Emotional, and Social Factors Explain Academic Achievement in Children Aged 6–12 Years: A Meta-Analysis. Education Sciences 11: 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbitt, Patrick, and Christine Lowe. 2000. Patterns of cognitive ageing. Psychological Research 63: 308–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Xuezhu, Karl Schweizer, Tengfei Wang, and Fen Xu. 2015. The prediction of students’ academic performance with fluid intelligence in giving special consideration to the contribution of learning. Advances in Cognitive Psychology 11: 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, Emma, Kathryn N. Devlin, Laurence Steinberg, and Tania Giovannetti. 2017. Grit in adolescence is protective of late-life cognition: Non-cognitive factors and cognitive reserve. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition 24: 321–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, Michelle, Charles Abraham, and Rod Bond. 2012. Psychological Correlates of University Students’ Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin 138: 353–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robins, Richard W., and Kali H. Trzesniewski. 2005. Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Current Directions in Psychological Science 14: 158–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodic, Maja, Xinlin Zhou, Tatiana Tikhomirova, Wei Wei, Sergei Malykh, Victoria Ismatulina, Elena Sabirova, Yulia Davidova, Maria Grazia Tosto, Jean-Pascal Lemelin, and et al. 2015. Cross-cultural investigation into cognitive underpinnings of individual differences in early arithmetic. Developmental Science 18: 165–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, Carissa, Allison Master, Dave Paunesku, Carol S. Dweck, and James J. Gross. 2014. Academic and emotional functioning in middle school: The role of implicit theories. Emotion 14: 227–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, Peter, and John D. Mayer. 1990. Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality 9: 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ruiz, Maria-Jose, Stella Mavroveli, and Joseph Poullis. 2013. Trait emotional intelligence and its links to university performance: An examination. Personality and Individual Differences 54: 658–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarver, Dustin E., Mark D. Rapport, Michael J. Kofler, Sean W. Scanlan, Joseph S. Raiker, Thomas A. Altro, and Jennifer Bolden. 2012. Attention problems, phonological short-term memory, and visuospatial short-term memory: Differential effects on near-and long-term scholastic achievement. Learning and Individual Differences 22: 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, E. Glenn. 2011. Examining the association between music lessons and intelligence. British Journal Psychology 102: 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, Roberto. 2000. Inteligencia y cultura. In Manual de Inteligencia. Edited by Roberto J. Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 549–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Yashpal, Archita Makharia, Abhilasha Sharma, Kruti Agrawal, Gowtham Varma, and Tarun Yadav. 2017. A study on different forms of intelligence in Indian school-going children. Industrial Psychiatry Journal 26: 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmayr, Ricarda, and Birgit Spinath. 2009. The importance of motivation as a predictor of school achievement. Learning and Individual Differences 19: 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmayr, Ricarda, Anne F. Weidinger, Malte Schwinger, and Birgit Spinath. 2019a. The importance of students’ motivation for their academic achievement–replicating and extending previous findings. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmayr, Ricarda, Linda Wirthwein, Laura Modler, and Margaret M. Barry. 2019b. Development of subjective well-being in adolescence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 1985. Beyond IQ: A Triarchic Theory of Human Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 2019. A theory of adaptive intelligence and its relation to general intelligence. Journal of Intelligence 7: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J., and Elena L. Grigorenko. 2004. Intelligence and culture: How culture shapes what intelligence means, and the implications for a science of well–being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 359: 1427–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, Robert J., Elena L. Grigorenko, and Donald A. Bundy. 2001. The predictive value of IQ. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 47: 1–41. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23093686 (accessed on 5 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert, Elena Grigorenko, Mercedes Ferrando, Daniel Hernández, Carmen Ferrándiz, and Rosario Bermejo. 2010. Enseñanza de la inteligencia exitosa para alumnos superdotados y talentos. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 13: 111–18. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2170/217014922011.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Tikhomirova, Tatiana, Artem Malykh, and Sergey Malykh. 2020. Predicting academic achievement with cognitive abilities: Cross-sectional study across school education. Behavioral Sciences 10: 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usán Supervía, Pablo, and Alberto Quílez Robres. 2021. Emotional Regulation and Academic Performance in the Academic Context: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in Secondary Education Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbitskaya, Ludmila A., Yury P. Zinchenko, Sergey B. Malykh, Igor V. Gaidamashko, Olga A. Kalmyk, and Tatiana N. Tikhomirova. 2020. Cognitive Predictors of Success in Learning Russian Among Native Speakers of High School Age in Different Educational Systems. Psychology in Russia. State of the Art 13: 2–15. Available online: http://psychologyinrussia.com/volumes/pdf/2020_2/Psychology_2_2020_2-15_Verbitskaya.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Visser, Beth A., Michael C. Ashton, and Philip A. Vernon. 2006. Beyond g: Putting multiple intelligences theory to the test. Intelligence 34: 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Stumm, Sopfhie, and Phillip L. Ackerman. 2013. Inversión e intelecto: Una revisión y meta-análisis. Psychological Bulletin 139: 841–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigfield, Allan, Stephen Tonks, and Susan Lutz Klauda. 2016. Expectancy-value theory. In Handbook of Motivation in School, 2nd ed. Edited by Kathryn R. Wentzel and David B. Miele. London: Routledge, pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby, Michael T., Brooke Magnus, Lynne Vernon-Feagans, Clancy B. Blair, and Family Life Project Investigators. 2017. Developmental delays in executive function from 3 to 5 years of age predict kindergarten academic readiness. Journal of Learning Disabilities 50: 359–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhoc, Karen C. H., Tony S. H. Chung, and Ronnel B. King. 2018. Emotional intelligence (EI) and self-directed learning: Examining their relation and contribution to better student learning outcomes in higher education. British Educational Research Journal 44: 982–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Number of Samples | Size of Samples | Age | Female | Male | Type of Intelligence | Type of Achievement | Country | Geographical Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aditomo (2015) | 1 | 123 | 18.67 | 99 | 24 | general | general | Indonesia | Asia |

| Blankson et al. (2019) | 2 | 198 | 4.84 | 106 | 92 | fluid | mathematics | USA | North America |

| Buckle et al. (2005) | 3 | 81 | 16.02 | 41 | 40 | general | general | Australia | Oceania |

| Chen and Tutwiler (2017) | 1 | 506 | 11 | 247 | 259 | emotional | general | USA | North America |

| Chen and Wong (2014) | 1 | 312 | 19.88 | 187 | 125 | general | general | China | Asia |

| Cheshire et al. (2015) | 1 | 96 | 21.46 | 71 | 11 | emotional | general | USA | North America |

| Chew et al. (2013) | 1 | 163 | 21.8 | 112 | 51 | emotional | general | Malaysia | Asia |

| Dinger et al. (2013) | 1 | 524 | 17.43 | 278 | 246 | implicit | general | Germany | Central Europe |

| Diseth et al. (2014) | 1 | 2062 | 12 | 1031 | 1031 | emotional | general | Norway | Northern Europe |

| Erath et al. (2015) | 1 | 282 | 10.4 | 154 | 126 | general | general | USA | North America |

| Fayombo (2012) | 1 | 151 | 22.8 | 88 | 63 | emotional | general | Barbados | America |

| El Jaziz et al. (2020) | 1 | 167 | 16.34 | 95 | 72 | kinesthetic | general | Morocco | North Africa |

| Kornilova et al. (2018) | 1 | 521 | 20.56 | 374 | 147 | emotional | general | Russia | Eastern Europe |

| Kiuru et al. (2012) | 1 | 476 | 13 | 290 | 186 | general | general | Finlandia | Northern Europe |

| Kornilova et al. (2009) | 4 | 300 | 19.48 | 221 | 79 | general | general | Russia | Eastern Europe |

| Li et al. (2017) | 3 | 4036 | 15.41 | 2066 | 1970 | emotional | general | China | Asia |

| Monir et al. (2016) | 2 | 407 | 9.5 | 203 | 204 | general | lenguage | Egypt | North Africa |

| Müllensiefen et al. (2015) | 1 | 320 | 14.14 | No data | No data | general | general | UK | Central Europe |

| Priess-Groben and Hyde (2017) | 1 | 165 | 17.35 | 77 | 88 | implicit | general | USA | North America |

| Rhodes et al. (2017) | 1 | 3826 | 71.19 | 2066 | 1760 | general | general | USA | North America |

| Romero et al. (2014) | 1 | 115 | 12.70 | 67 | 48 | emotional | general | USA | North America |

| Sanchez-Ruiz et al. (2013) | 1 | 323 | 23 | 113 | 210 | emotional | general | UK | Central Europe |

| Sarver et al. (2012) | 4 | 325 | 10.67 | 146 | 179 | general | musical | USA | North America |

| Steinmayr et al. (2019a) | 1 | 354 | 17.48 | 200 | 145 | verbal | general | Germany | Central Europe |

| Steinmayr et al. (2019b) | 1 | 476 | 16.43 | 244 | 232 | general | general | Germany | Central Europe |

| Tikhomirova et al. (2020) | 9 | 1560 | 6.8 | 718 | 842 | fluid | language | Russia | Eastern Europe |

| Willoughby et al. (2017) | 1 | 1120 | 4 | No data | No data | general | general | USA | North America |

| Models | TauSq | R² | Q | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 Intelligence | 0.03 | 0.35 | 30.49 | 9 | 0.0004 |

| Model 2 Performance | 0.06 | 0.00 | 6.33 | 5 | 0.2758 |

| Model 3 Age | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0,00 | 1 | 0.9754 |

| Model 4 Country | 0.03 | 0.45 | 54.65 | 12 | 0.0000 |

| Model 5 Female | 0.06 | 0.00 | 2.81 | 1 | 0.09 |

| Model 6 Male | 0.05 | 0.03 | 2.92 | 1 | 0.08 |

| Model 7 Geography | 0.03 | 0.37 | 15.73 | 1 | 0.15 |

| Meta-Regression M.1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Coefficient | Standard Error | 95% Lower | 95% Upper | Z | 2-Sided p-Value | Q | df | p |

| Intercept | 0.10 | 0.20 | −0.29 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 30.49 | 9 | 0.0004 |

| Crystallised | 0.34 | 0.29 | −0.22 | 0.91 | 1.19 | 0.23 | |||

| Emotional | 0.13 | 0.21 | −0.27 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.52 | |||

| Spatial | 0.01 | 0.28 | −0.55 | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.97 | |||

| Fluid | 0.24 | 0.20 | −0.17 | 0.65 | 1.15 | 0.25 | |||

| General | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.82 | 2.00 | 0.04 | |||

| Implicit | 1.05 | 0.28 | 0.49 | 1.61 | 3.69 | 0.00 | |||

| Mathematical | 0.14 | 0.28 | −0.42 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.61 | |||

| Synaesthetic | 0.35 | 0.29 | −0.22 | 0.92 | 1.20 | 0.23 | |||

| Verbal | 0.19 | 0.23 | −0.26 | 0.65 | 0.82 | 0.41 | |||

| Meta-Regression M.2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Coefficient | Standard Error | 95% Lower | 95% Upper | Z-Value | 2-Sided p-Value | Q | df | p |

| Intercept | 0.48 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.69 | 4.42 | 0.00 | 54.65 | 12 | 0.0000 |

| Australia | 0.12 | 0.16 | −0.20 | 0.44 | 0.74 | 0.45 | |||

| Barbados | 0.17 | 0.22 | −0.27 | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.43 | |||

| China | −0.31 | 0.14 | −0.60 | −0.03 | −2.22 | 0.02 | |||

| Egypt | −0.23 | 0.17 | −0.57 | 0.10 | −1.36 | 0.17 | |||

| Finland | −0.13 | 0.21 | −0.55 | 0.29 | −0.59 | 0.55 | |||

| Indonesia | 0.69 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 1.14 | 2.97 | 0.00 | |||

| Malaysia | −0.41 | 0.22 | −0.86 | 0.03 | −1.82 | 0.06 | |||

| Morocco | −0.32 | 0.22 | −0.47 | 0.41 | −0.14 | 0.88 | |||

| Norway | −0.07 | 0.21 | −0.49 | 0.34 | −0.34 | 0.73 | |||

| Russia | −0.19 | 0.12 | −0.43 | 0.03 | −1.65 | 0.09 | |||

| UK | −0.52 | 0.17 | −0.86 | −0.17 | −2.98 | 0.00 | |||

| USA | 0.09 | 0.12 | −0.14 | 0.33 | 0.76 | 0.44 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lozano-Blasco, R.; Quílez-Robres, A.; Usán, P.; Salavera, C.; Casanovas-López, R. Types of Intelligence and Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Intell. 2022, 10, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10040123

Lozano-Blasco R, Quílez-Robres A, Usán P, Salavera C, Casanovas-López R. Types of Intelligence and Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Intelligence. 2022; 10(4):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10040123

Chicago/Turabian StyleLozano-Blasco, Raquel, Alberto Quílez-Robres, Pablo Usán, Carlos Salavera, and Raquel Casanovas-López. 2022. "Types of Intelligence and Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Intelligence 10, no. 4: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10040123

APA StyleLozano-Blasco, R., Quílez-Robres, A., Usán, P., Salavera, C., & Casanovas-López, R. (2022). Types of Intelligence and Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Intelligence, 10(4), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10040123