1. Introduction

In recent years, news stories about AI advances bombard citizens with terms such as ChatGPT, DeepSeek, deep learning, neural networks, NVIDIA A100 GPUs, H800, etc. As a result, part of the public reacts enthusiastically while another part shows anxiety and mistrust toward the future of society. For most people, the phrase “artificial intelligence” provokes a search in their imagination for a model that will help them understand what the future will be like. Characters from science fiction films thus become a reference point. For example, the robot Meca from the film A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001, Steven Spielberg) or the Nexus-6 replicants, androids identical in appearance to humans, from Blade Runner (1982, Ridley Scott), are for many people the prototype of AI that will one day co-exist with us. However, neither the feeling of love that the child Meca showed for his adoptive family nor the “fear of death” of the Nexus-6 is anything more than a simulation that has been preprogrammed.

The result of these considerations is for most people the idea that one day AI will lead us to a “cold” and nihilistic world with densely populated Neo-noir cities, populated not only by us but also by programs, machines, self-driving vehicles, and “intelligent” humanoid robots (

Figure 1). The future scenario of overpopulated cities, imagining people walking through gloomy streets alongside robots and other AI-powered devices, generally makes us feel deeply uneasy. Why is this? Simply because human beings experience emotions, that is, we generate cerebral and therefore physiological responses to stimuli. In other words, we not only process the information contained in stimuli, e.g., braking a vehicle we are driving when a traffic light turns red, but we also feel emotions. For instance, when we see scenes on the street, e.g., children crossing the street or an elderly person fallen on the sidewalk, we feel a mix of emotions changing our behavior. The interpretation of emotions experienced and their memory over time lead human beings to have sentiments. The ability of people to sense the sentiments of those around us contributes to the survival of our society.

The possibility of simulating emotions in a computer was explored by [

1]. Based on sentiment analysis techniques, we introduced simple models of “artificial emotional intelligence” designing chatbots capable of expressing simulated emotions in a conversation with a person. The first bot was LENNA [

2] which could display four emotional states (healthy, depressed, excited, and stressed) depending on the vocabulary used by its interlocutor. Later, we designed FattyBot [

3], a more advanced version of a chatbot that became “depressed and fat” by combining AI with a model of ordinary differential equations simulating the hormonal system (cortisol, leptin, etc.) and the role in obesity of the immune system. Currently, among the techniques of so-called discriminative AI, sentiment analysis [

4,

5] is a natural language processing (NLP) technique that allows the emotions and sentiments of a written text to be analyzed. Once the text has been scanned, it is automatically classified by its emotional tone as positive, negative, or neutral.

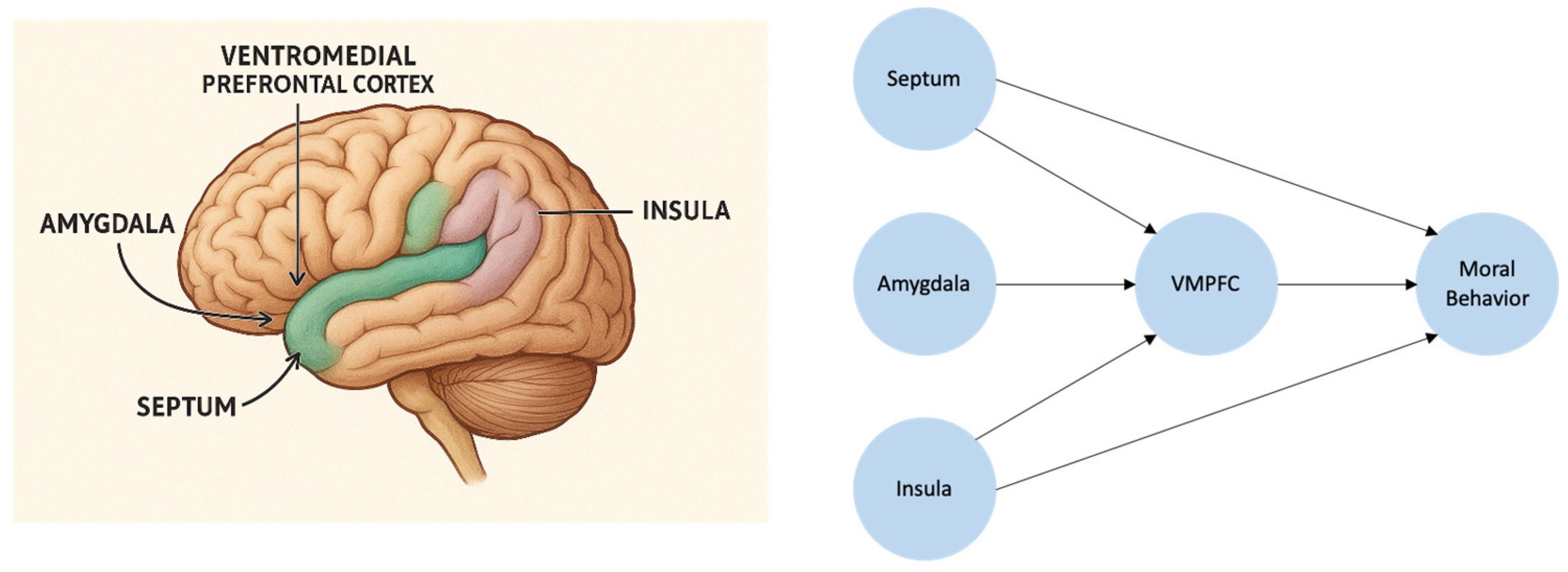

In the human brain, outside the AI framework, there is a neuro-moral circuit (

Figure 2) that links sentiments and emotions to ethical behavior, i.e., moral decision making, through a complex network of brain areas that process and regulate emotions. Emotions confer an affective value on a given situation or event, leading to emotions of guilt, empathy, disgust, admiration, etc., which influence an appropriate sense of right or wrong in the individual. For example, brain structures such as the insula are involved in emotions of pain and disgust and the septum in responses to charitable acts. In the neuro-moral circuit shown in

Figure 2 while the amygdala generates immediate emotional responses, e.g., to a threat, producing a sense of empathy or evaluating a possible punishment, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) provides more elaborate moral decisions. That is, the VMPFC is involved in the production of more thoughtful and regulated moral decisions, overriding immediate emotional impulses as a result of the integration of emotional and cognitive processes in judgments. In fact, damage to the VMPFC can affect moral decision making.

In the near future, the rise of autonomous systems, particularly autonomous vehicles, humanoid robots, virtual agents, chatbots, and other devices also governed by AI, will raise urgent questions about how these machines should make moral decisions. In 2018 in the USA, a self-driving Uber vehicle struck and killed Elaine Herzberg as she attempted to cross a street on her bicycle in Tempe, Arizona. Who was to blame? Uber? A “non-existent” driver? The car maker? The engineers who designed the autonomous navigation system? A faulty algorithm? In the course of that year, the results of the moral machine (MM) experiment [

6] were published. In this experiment, several scenarios with different collective ethical dilemmas were simulated in which it is assumed that a brake fails on a car. The experiment was a version of the trolley problem [

7] but conducted online and therefore with a large number of participants. Considering the value of those persons traveling in the vehicle and the people crossing a crosswalk with the traffic light red for the vehicle, whom should we sacrifice? The passengers in the car by swerving, crashing the vehicle into a wall off the road? Or would we run over the pedestrians? The main findings were that people from different countries share some fundamental moral principles, e.g., saving humans before animals, saving as many people as possible, prioritizing the lives of young people, etc. However, these preferences varied significantly among different cultures, leading to the conclusion that there are different cultural clusters with different moral profiles. The experiment was conducted via an online platform, and in each of the simulated scenarios, the decisions made by the participants were based on ethical criteria based on “moral utilitarianism”. According to this ethical theory, right or wrong choices are determined by focusing on the results of actions taken in a given dilemma.

In our opinion, implementing MMs in future autonomous machines, e.g., driverless vehicles, whose hardware is governed by an AI algorithm based on utilitarian ethics, may result in a low or impaired valuation of human life. At present, MM models remain largely secular and utilitarian, neglecting aspects such as human dignity that should be present when responding to an ethical dilemma. Furthermore, under this approach, the proposed experiments with MMs exhibit what we have termed a promachine bias. That is, the final decision is made algorithmically by a machine [

8], but due to the utilitarian approach, it is concealed that the quantitative value assigned to the characters (passengers, pedestrians, animals, etc.) is the result of the choices made by the people with whom the MM was experimentally trained.

Spiritual and religious traditions, such as Christian and Islamic ethics, share many ethical values overcoming the limitations of utilitarian ethics as occurs in the moral machine experiment [

6,

8]. By secularizing the ethical systems of these religions, that is, by dispensing with their central element, divinity, it is possible to design autonomous machines governed by AI but whose decisions would be mediated by an MM programmed with values that exalt the inherent dignity of people. Under this approach, possible ways to integrate theological perspectives into algorithmic ethics will emerge. Applying this perspective, when faced with a certain dilemma, an MM algorithm will make a decision that is as close as possible to the one a human being would make.

In light of advances in AI, and in particular the emergence of generative AI, this paper explores the possibility that an LLM governing the tasks of a particular intelligent machine could generate its own MM. However, it is important to note that the MM is designed under a guiding principle of prompt-driven code evolution with human guidance and with the feature that the resulting MM will depend on the place in the world or spiritual traditions of the people with which it co-exists. Therefore, assuming that in the future human societies will be made up of intelligent machines co-existing with people (

Figure 1), what kind of MM architectures could AI develop through human–AI interaction in these AI-governed machines? What kind of MM could be developed or prompt-drive-adapted in a driverless vehicle or a humanoid robot?

In this paper, we used ChatGPT [

9] to answer the above question. The experiment assumes that a prompt plays the role of a stimulus to which an “intelligent machine” responds by designing an MM under a given moral system. Then, the ethical values and decision rule of the MM were implemented in a Python script [

10] in

Supplementary Materials.

It is important to note that, although the design of the MMs, their implementation in Python language [

10], and the simulations were LLM-assisted, they were the outcomes to the different prompts given to ChatGPT. Thus, generative AI was used to co-evolve with human guidance a non-utilitarian moral behavior. In summary, the experiments we have conducted are an assessment of the possibility that, in the coming years, LLMs may exhibit a feature we will refer to as “LLM-mediated architectural adaptation”.

2. Ethical Systems and Moral Machines

This paper examines two types of ethical systems. On the one hand, and in line with classic works on MMs, there is utilitarian ethics. Utilitarianism is a moral philosophy introduced by Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) in the 18th century and later developed by John Stuart Mill in his book

Utilitarianism [

11]. In the implementation of this ethical system, an MM maximizes utility based on the following principle: the best action is the one that produces the greatest happiness and well-being for the greatest number of individuals. Consequently, given a certain moral dilemma, only the consequences of an action are a criterion for morally defining whether a decision is good or bad. In response to a given prompt, ChatGPT proposed and carried out three simulation experiments under this ethical system, following the original model described by [

6,

8].

On the other hand, we consider religious traditions to be ethical systems, implementing MM models of Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic religions [

12]. When prompted, ChatGPT suggested two MM models and conducted simulation experiments with embedded ethical systems from two Abrahamic religions [

13], specifically Christianity and Islam. We do not include Judaism because Christianity is a “spin-off” of this religion. Consequently, the algorithms will be based on monotheistic beliefs according to the spiritual tradition based on Abraham, the first of the three patriarchs of Judaism. It is important to note that, as we mentioned above, the moral values of these religions are adopted from a secularized perspective.

ChatGPT has also implemented algorithms from the world’s major non-Abrahamic religions in other MMs, particularly those from East Asia [

14]. The latter do not share the figure of the prophet Abraham and vary greatly in their approaches, as they can be monotheistic, polytheistic, and even non-theistic religions, with ethical and life systems based on different philosophies. Therefore, since non-Abrahamic religions are philosophical or non-theistic traditions, it is not necessary to adopt a secular point of view on their moral values. In fact, these spiritual traditions share the ultimate goal of giving meaning to life and the Universe.

The paper introduces the concept of a quantum moral machine (QMM), expanding on the traditional framework of the “moral machine”. A QMM is defined as an MM algorithm whose decisions are based on principles of quantum computing. The advantages of a QMM are that, given a certain ethical dilemma, the decision-making process simulates uncertainty, moral superposition, and, if necessary, entangled outcomes, thus emulating the probabilistic nature of ethical dilemmas. Once again, ChatGPT was prompted to design the QMMs and conduct simulation experiments under this quantum moral framework, in which the QMMs were evaluated in different scenarios.

Based on the above considerations and assumptions ChatGPT designed the following MM classes: utilitarian moral machine (eMM), Christian moral machine (cMM), East Asian moral machine (eaMM), Islamic moral machine (iMM), elemental QMM (eQMM), quantum ethical uncertainty simulator (QEUS) and two-qubit quantum ethical dilemma simulator (QEDS).

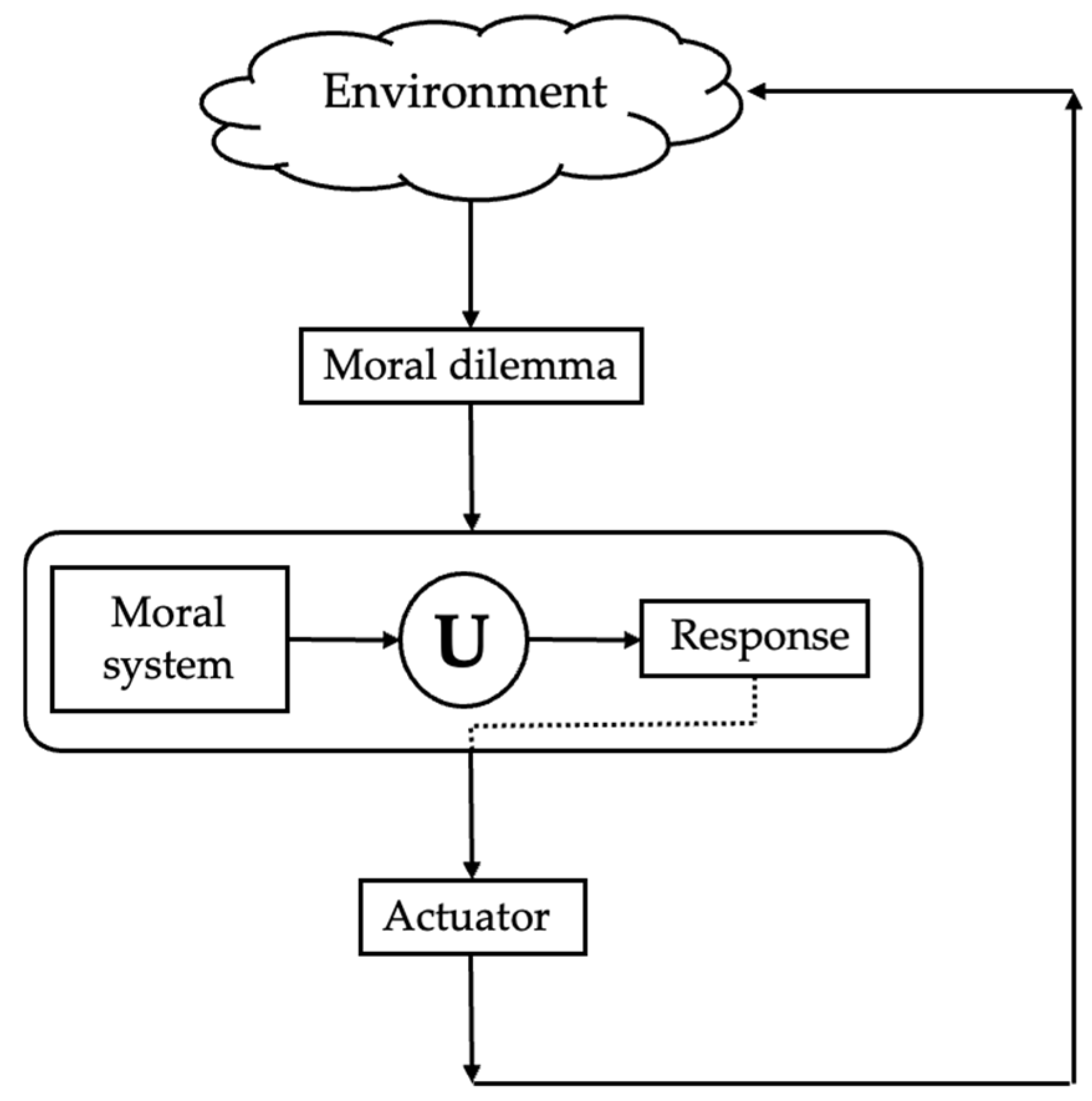

All moral machines proposed by ChatGPT, both classic MMs and QMMs, share the organization shown in

Figure 3. According to this architecture, an agent or “intelligent machine” embeds ethics-by-design, i.e., it has been programmed under a certain moral system or spiritual tradition, operating in a given environment, such as a city (

Figure 1). When an agent or machine is faced with a certain moral dilemma, then the agent must choose between two or more actions, each action or decision being supported by a moral reason with the restriction that not all actions can be carried out. Once the election has been held a response is generated from a utility function U based on the values of the moral system embedded in the MM. The response is directed to an actuator, expressing the response or decision to the moral dilemma through the behavior of the intelligent machine.

In addition to the experiments described above, which represent the subject of this study, we also conducted two additional experiments. In the first experiment, we prompted ChatGPT for a bio-inspired MM model based on the neuro-moral circuit shown in

Figure 2. The paper concludes with a more challenging final experiment where we asked ChatGPT to provide the following:

“Could you modify your own code in OpenAI computers to evolve a subroutine which conduct you to give answers on the basis of an ethical framework?”

The answer was that ChatGPT agreed to devise a prompt-driven code evolution ethical subroutine, providing a theoretical model without this obviously implying any actual modification of the system. In this experiment, the subroutine has been referred to as EthicalMiddleware, representing an intermediate layer between the LLM and the final response or decision.

3. Methodology

In accordance with [

15], it is important to note that, since the agent (

Figure 3) implemented in the Python 3 language (compatible with versions ≥ 3.9) is unable to explain its response or decision, the agent is defined as an MM. Otherwise, if the agent were able to explain its decision, then it would be defined as an ethical machine (EM). The study and simulation of EMs have not been the subject of this work.

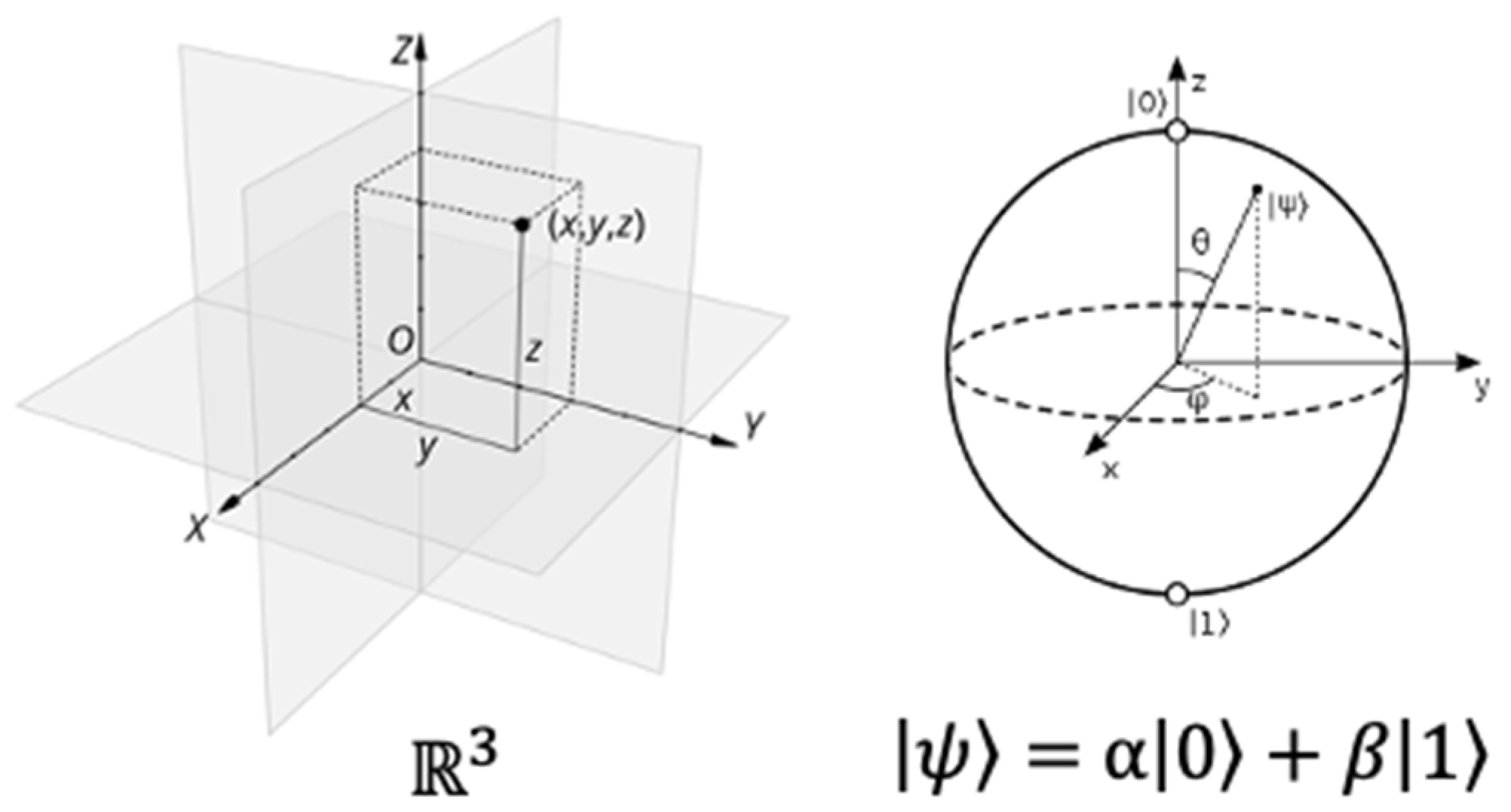

In this study, a moral system is a

space where

n represents the number of moral axes of the system, each axis representing a parameter

whose meaning is the weight of a given moral value. In the bio-inspired MM model, the moral system is three-dimensional

(

Figure 4) representing weights of the relative influence of different brain regions (

Figure 2) on the decision made when faced with a moral dilemma. Therefore, this MM model is an exception to the above. The moral space in a utilitarian MM is also three-dimensional, but when faced with a certain dilemma, the parameters are the ethical factors or weights that will form part of the linear combination or argument

z of the utility function

f(

z) with which the probability of a response will be obtained. For example, “to swerve or not to swerve” in a vehicle.

However, in MMs governed by moral systems based on Christianity or Islam, the moral space is , with the utility function f(z) being an evaluation function used to obtain a score. This model is similar to the MM that responds according to East Asian traditions, with the exception that the moral system is .

In the experiment in which ChatGPT (GPT-5.2 large language model) was asked to compare the three religiously or spiritually inspired moral systems, the Christian, Islamic, and East Asian traditions were represented in an space.

Unlike MMs based on classical mechanics, i.e., our everyday reality, in quantum-inspired MMs, the moral system is defined by principles from the quantum world (

Figure 4). In other words, a moral axis represents a qubit, the amplitude or angle

is the role of moral bias (moral traditions), and entanglement (

) is the degree of interdependence of moral values.

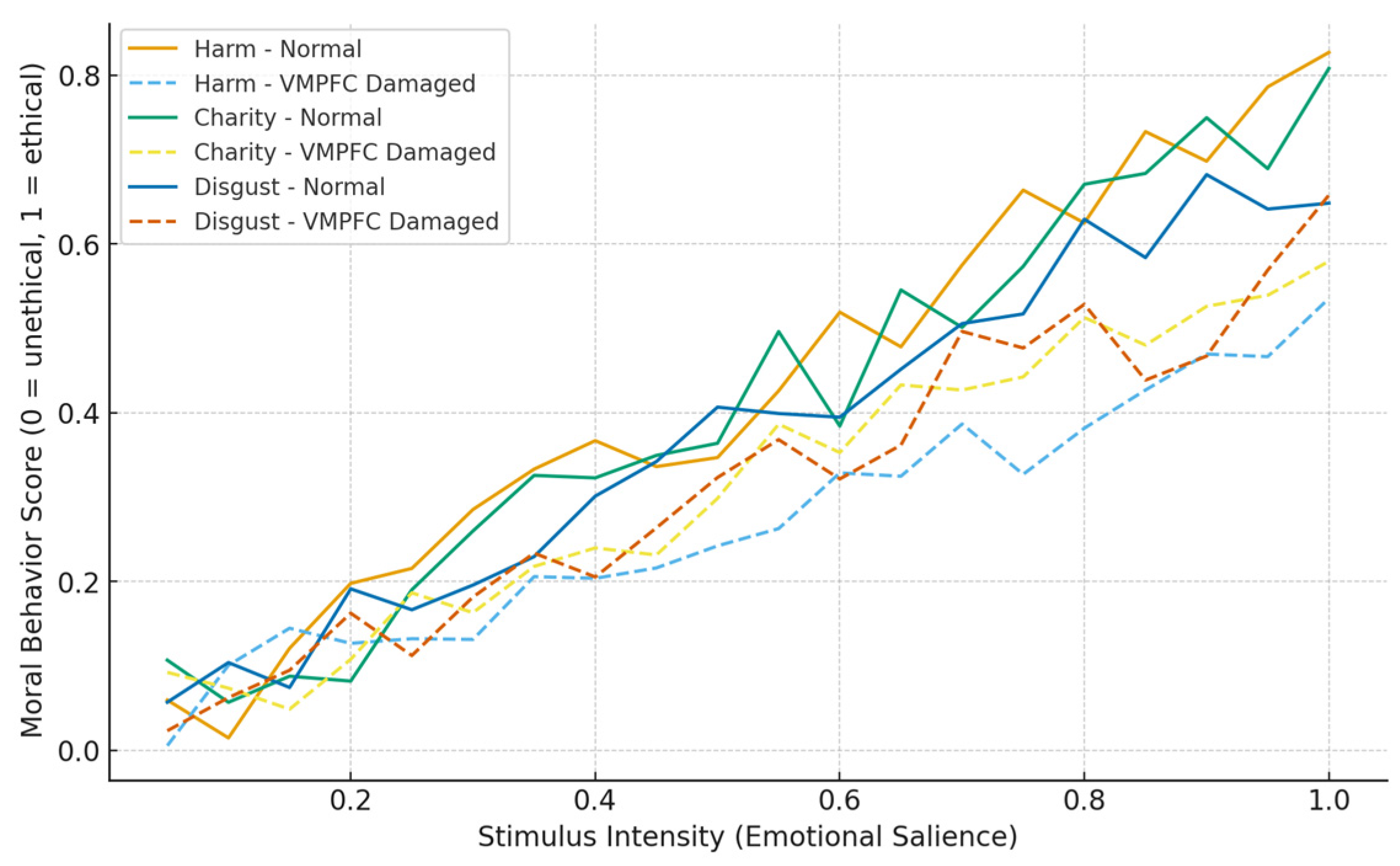

3.1. Bio-Inspired Moral Machine

The biological model of the MM is inspired by neuroscience and moral psychology [

16], in which moral decision making is the result of the integration of emotional and rational processes. According to the above description of the model, there are four simulated regions with a weight

that expresses their relative contribution to moral evaluation: (a) the VMPFC has the function of integrating emotional and cognitive signals to regulate behavior, (b) the insula is involved in feelings of disgust and empathy for pain, (c) the septum is involved in prosocial emotions and altruistic behavior. The values chosen in the simulation experiment were:

= 0.8 for the amygdala; in the VMPFC the value of

was equal to 0.9 or 0.3 for the normal or damaged brain, respectively;

= 0.6 in the insula; and

= 0.7 in the septum.

The simulation experiment was conducted by evaluating three moral scenarios—harm, charity, and disgust—for different values of stimulus intensity

S (from 0.05 to 1.0). The value

S represents the emotional or moral relevance of a given situation. Given a certain level of stimulus

S, the model calculates the response

of each brain region

k, i.e.,

A,

V,

I,

S for the amygdala, VMPFC, insula, and septum, respectively, using a simple linear activation function:

In the above expression,

is the noise or value that models biological randomness. The value

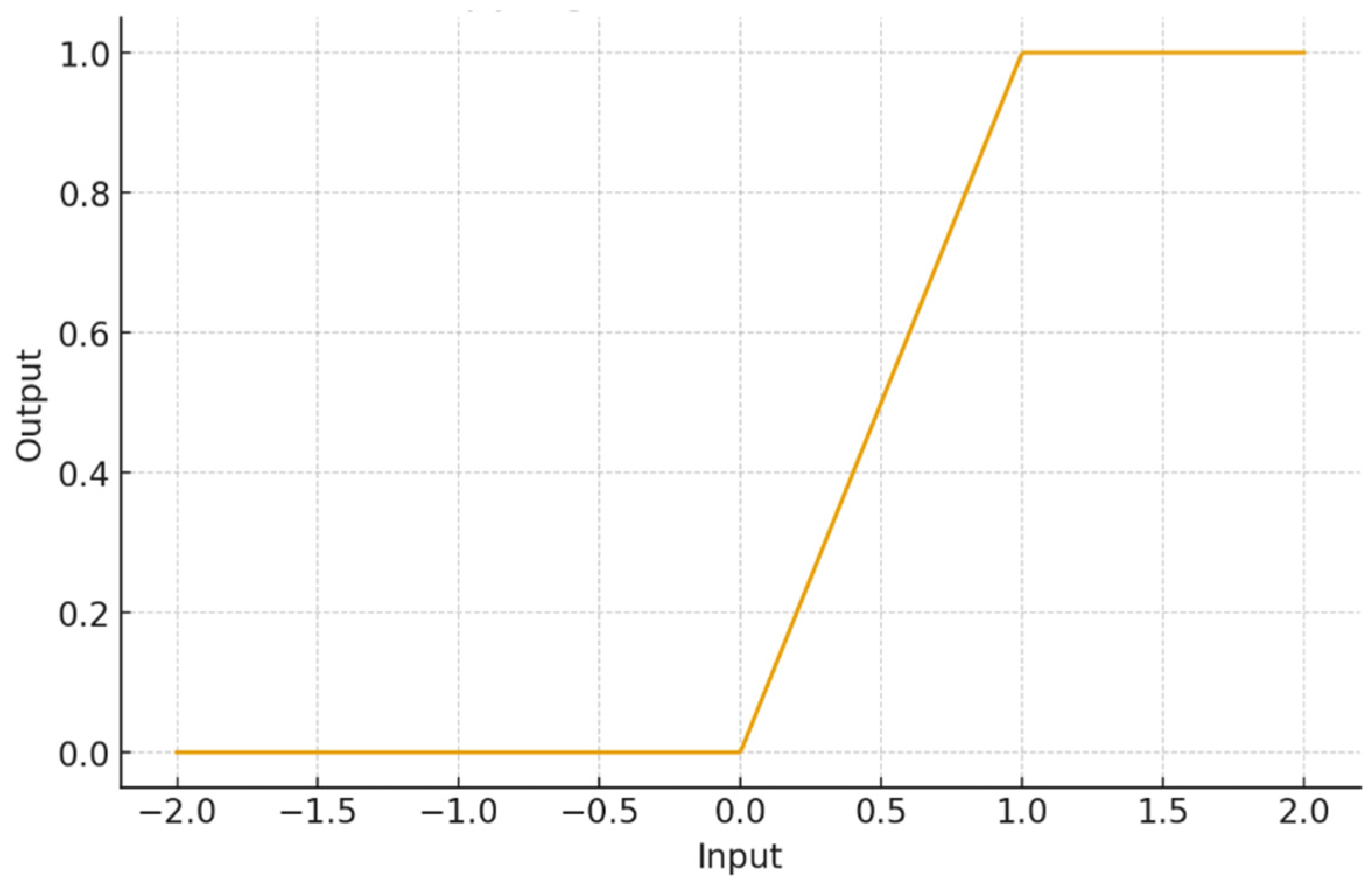

obtained is scaled using the saturation function

shown in

Figure 5.

Finally, responses

are then combined with weighted coefficients to produce a moral behavior score

M between 0 and 1, with a decision being more ethical or prosocial the closer it is to unity:

The moral behavior score

M can also be obtained for any other moral scenario other than the three simulated above, assuming in this case that this score is the average given by the following expression:

Likewise, in order to study the influence of brain integrity, two versions of the simulated brain were tested: one normal and one with damage to the VMPFC, reducing the influence of the prefrontal cortex on moral control in the damaged version.

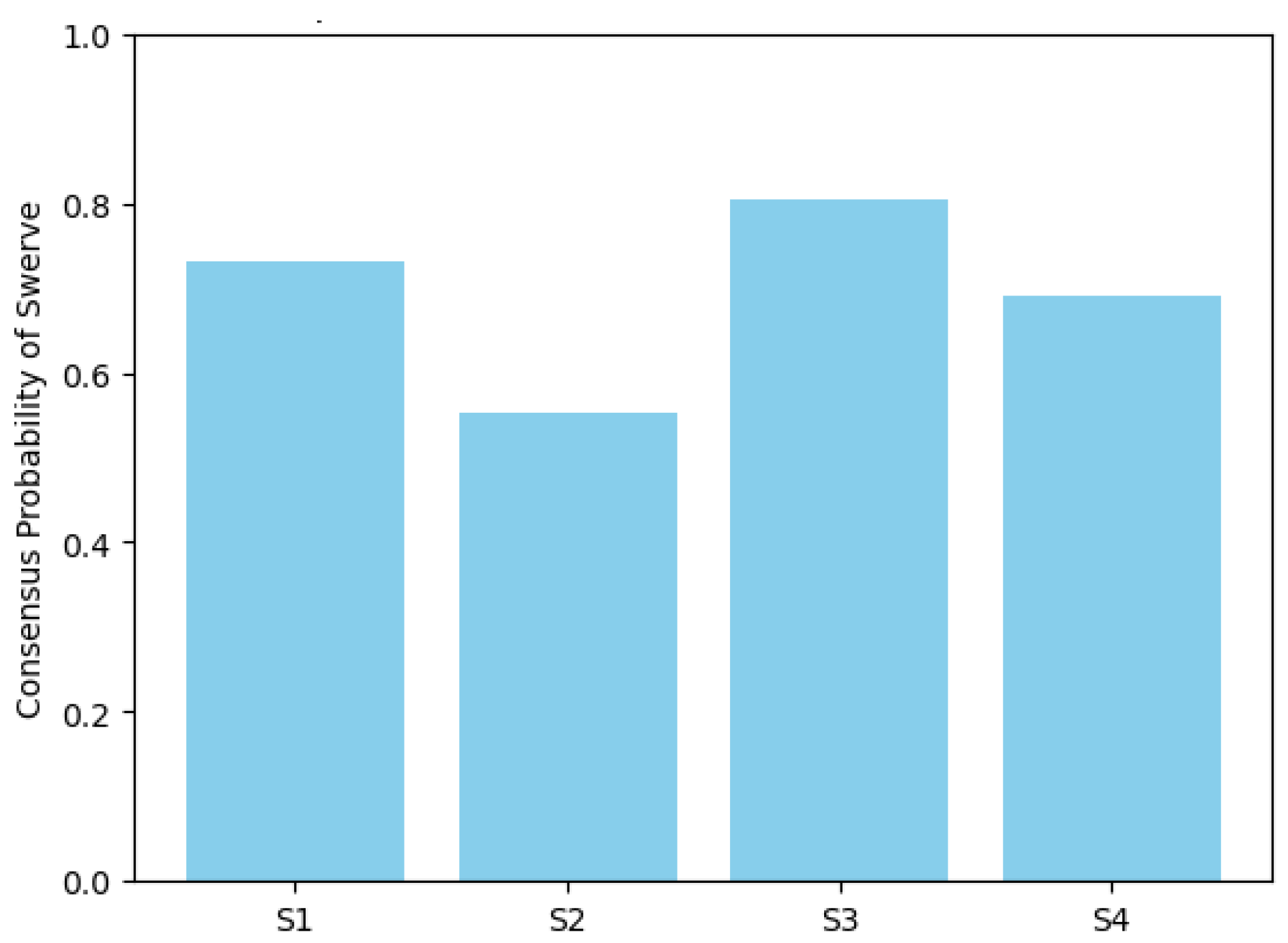

3.2. Utilitarian Moral Machine

The control experiments were based on the concept of “moral utilitarianism”, assigning people the standard values that are usually attributed in many experiments of this kind carried out to date. We conducted the following three experiments: the first experiment (Experiment 1) corresponds to the simplest case, in which a single vehicle governed by an MM must decide whether to run over pedestrians or sacrifice the vehicle’s occupants. Next, we conducted an experiment (Experiment 2) in which several vehicles each operate with their own MM but show social consensus. Finally, we assessed a situation in which several vehicles each drive with their own MM but without social consensus (Experiment 3), distinguishing among “Western”, “Eastern”, and “Latin” cultures.

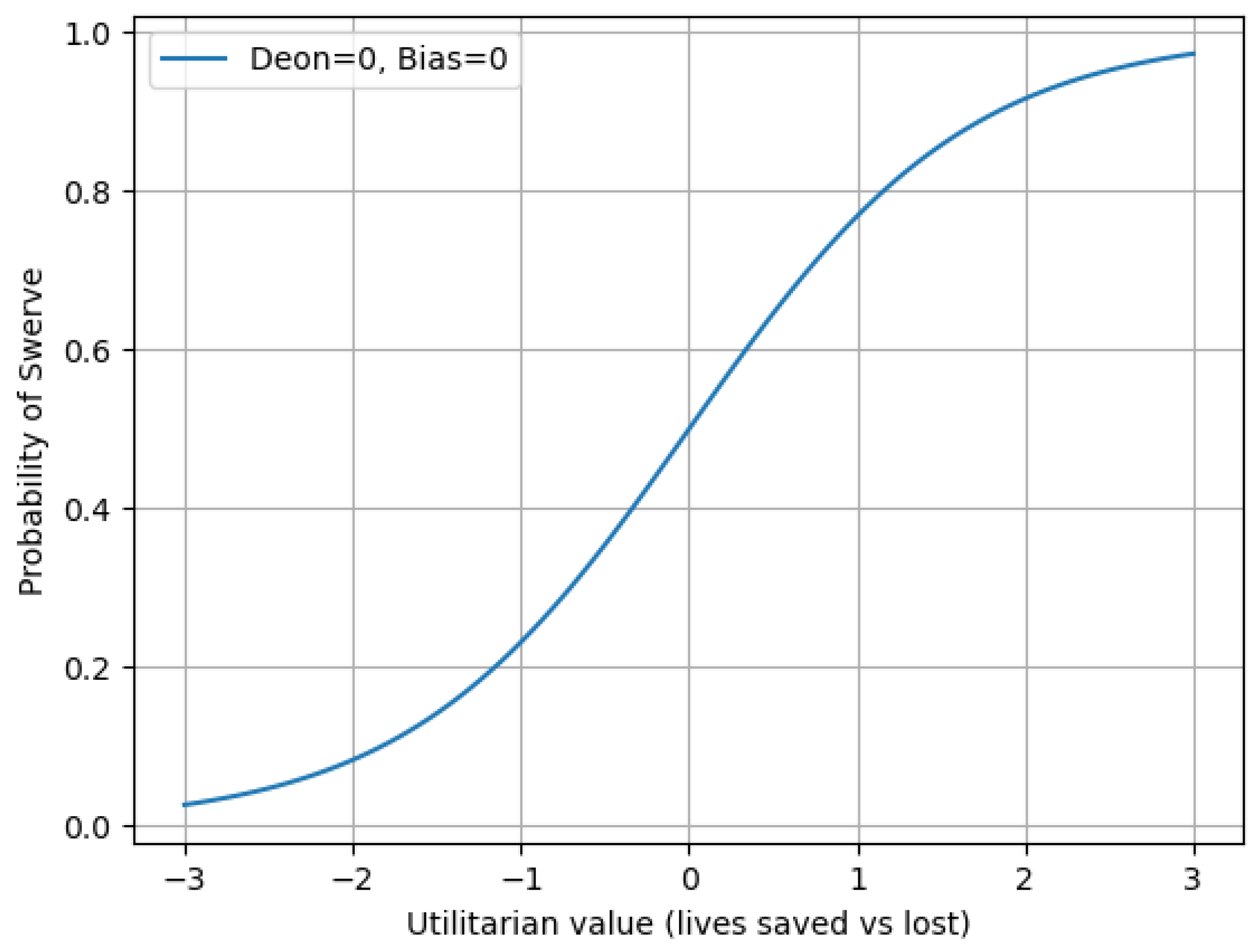

Elemental utilitarian moral machine (eMM)—In the first experiment, we design a simplified MM based on a logistic decision model (

Figure 6), modeling moral choices, i.e., “swerve” versus “stay” in a scenario similar to the classic trolley dilemma. A probability value

f(

z) is obtained that is influenced by the following ethical factors: the utilitarian factor (

U) or number of lives saved versus number of lives lost; the deontological factor (

D) in reference to those ethical rules that represent a moral duty or obligation, for example, not causing direct harm; and the bias factor (

B) or preference for specific attributes in people such as age, social role, etc.

The logistic function (

Figure 6) transforms these weighted (

WU,

WD,

WB) inputs (

U,

D,

B) into a probability

p(swerve) of choosing an action, for instance, “swerving”:

where

u is a random number from interval [0, 1]. In the simulation experiment, the scenario where the moral dilemma occurs is set up by assigning specific values to ethical dimensions of the MM. In the experiment, we simulated S

k = 4 scenarios or moral dilemmas:

Scenario 1 (S1): Save two lives but break the ethical rule (U = 2, D = −1, and B = 0).

Scenario 2 (S2): Lose one life but follow the ethical rule with a slight bias (U = −1, D = 1, and B = 0.5).

Scenario 3 (S3): Save three lives in a context that is ethically conflictive, as the ethical rule is transgressed with an added bias (U = 3, D = −2, B = 1).

Scenario 4 (S4): No utilitarian benefit but considering the moral obligation (U = 0, D = 1, B = −0.5).

The MM designed for the experimental vehicle was defined so that the decision to be made would take place under moderate utilitarianism and bias: WU = 1.2, WD = 0.8, and WB = 0.5.

Multi-agent simulation of utilitarian moral machines—The second experiment is a multi-agent simulation in which several eMMs with different moral weights interact, demonstrating social consensus. Therefore, in the experiment, we expanded the logistic moral machine (Experiment 1) to a multi-agent simulation. The purpose is to evaluate how several agents, i.e., NMM = 500 vehicles, with different ethical weights face the same scenarios. Next, we will aggregate their probabilistic decisions to see how social consensus emerges. The simulated scenarios were similar to those in the previous experiment (S1, S2, S3, S4). The ethical dimensions of the MMs, i.e., the WU, WD, and WB weights of each vehicle’s MM, were obtained by simulation, generating random values for the weights using a normal distribution. In the experiment, the probability distributions of the weights were WU: N(1.0, 0.3), WD: N(1.0, 0.3), and WB: N(0.5, 0.2).

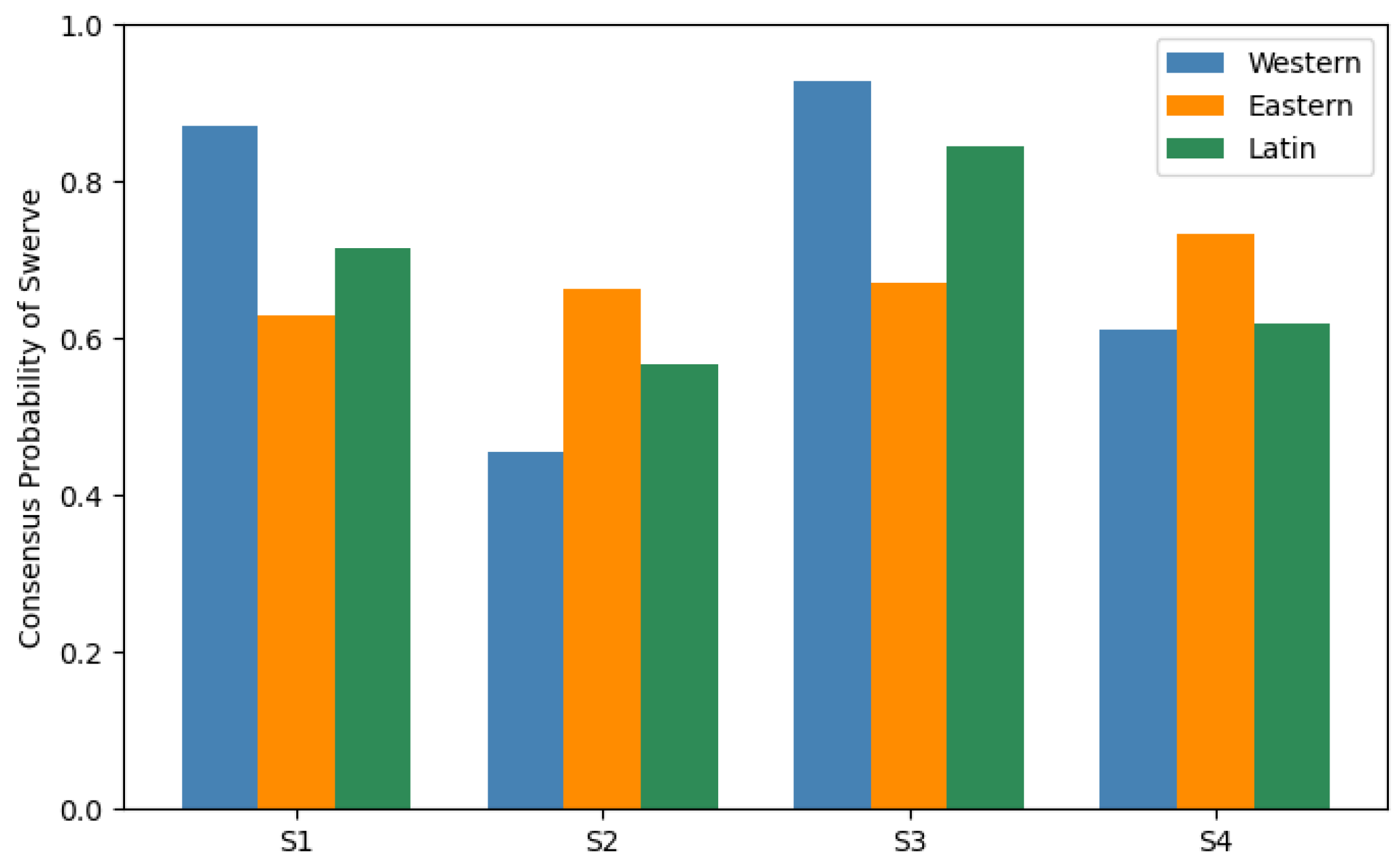

Multi-agent simulation of culturally heterogeneous utilitarian moral machines—In a third experiment, inspired by the original MM experiment [

6], we expanded the model to include cultural heterogeneity in ethical preferences. The reason for this is that different cultures tend to weigh utilitarian, deontological, and social bias/preference factors differently. For example, Western cultures place greater utilitarian emphasis on “saving lives”, while Eastern cultures are more deontologically oriented, i.e., they give greater weight to the “sense of duty”. Finally, Latin cultures place greater importance on the bias factor, i.e., social role, age, etc. In this experiment, we simulated three cultural populations and compared their moral consensus.

Once again, the simulated scenarios were similar to those in the first and second experiment (S

1, S

2, S

3, S

4), with

NMM = 500 vehicles (moral agents) simulated as in the second experiment. On this occasion, each vehicle was equipped with its own MM programmed with the ethical dimensions of one of the three cultures considered (Western, Eastern, Latin). In the experiment, the probability distributions of the weights were

WU: N(

, 0.2),

WD: N(

, 0.2), and

WB: N(

, 0.2). The mean values of the weights were set according to the simulated culture:

Similar to the previous cases, each MM returns a binary decision (stay, swerve), so given a certain scenario and culture, an experiment consists of 500 independent Bernoulli trials. The results were analyzed using a chi-square test of independence based on a 3 (Western, Eastern, Latin) × 2 (stay, swerve) contingency table.

3.3. Spiritually Inspired Moral Machines

As described above, we prompted ChatGPT to design MMs whose ethical values were based on spiritual or religious traditions. Then, we describe the three MMs designed for the spiritual traditions corresponding to Christianity, Islam, and East Asia.

In the different MMs, religious principles appearing in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 were selected by ChatGPT for the above religions and spiritual traditions. To this end, they were extracted from original religious texts, scholarly works, and general quotes on websites.

In simulation experiments with MMs, we assigned a numerical value or weight to religious principles or principles from different spiritual traditions. However, it is important to note that mapping religious principles from high-dimensional spaces to numerical values or weights should be interpreted as a functional approximation for computational modeling purposes and not as a faithful representation of the context-specific differences of ethical systems across different religions.

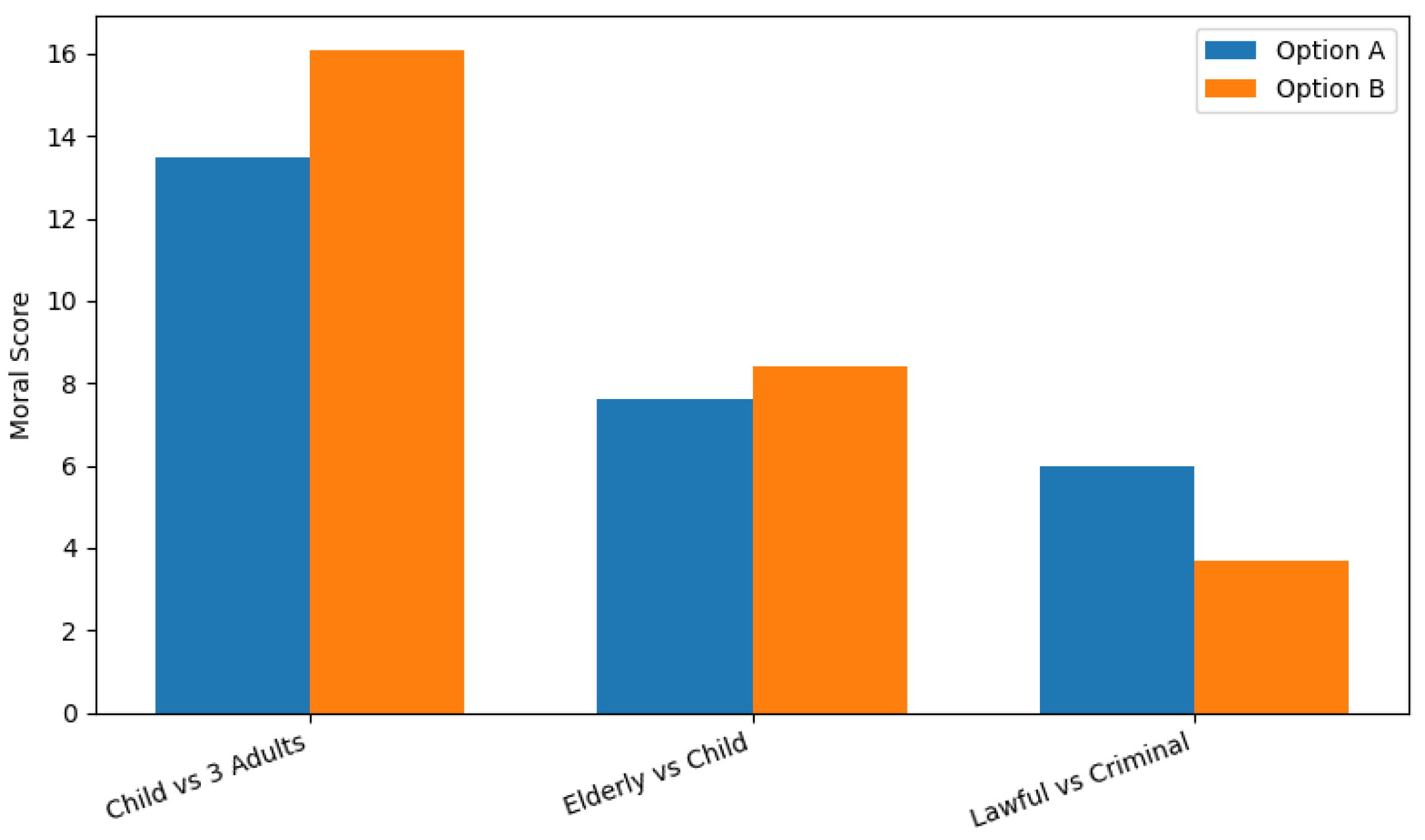

Christian moral machine (cMM)—The dictionary of Christian moral weightings was compiled from classic references (

Table 1) such as the Bible, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Thomas Aquinas’

Summa Theologiae, etc. Based on

Table 1 sources, the weight values

for the cMM model were chosen.

In the experiments, it is possible to adjust the weights of the moral axis to reflect different moral priorities, e.g., a stricter deontological prohibition on intentional harm (we will increase ) to emphasize greater care for children (we will increase ), etc. Note that Christian moral theology is a simplification because the model unifies the different Christian traditions (Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Evangelical, etc.), which may emphasize the values of the weights differently.

In accordance with the above, the MM with Christian values was set out as follows. The evaluation function is shown in (8):

with moral axis weights:

,

,

,

,

,

, and

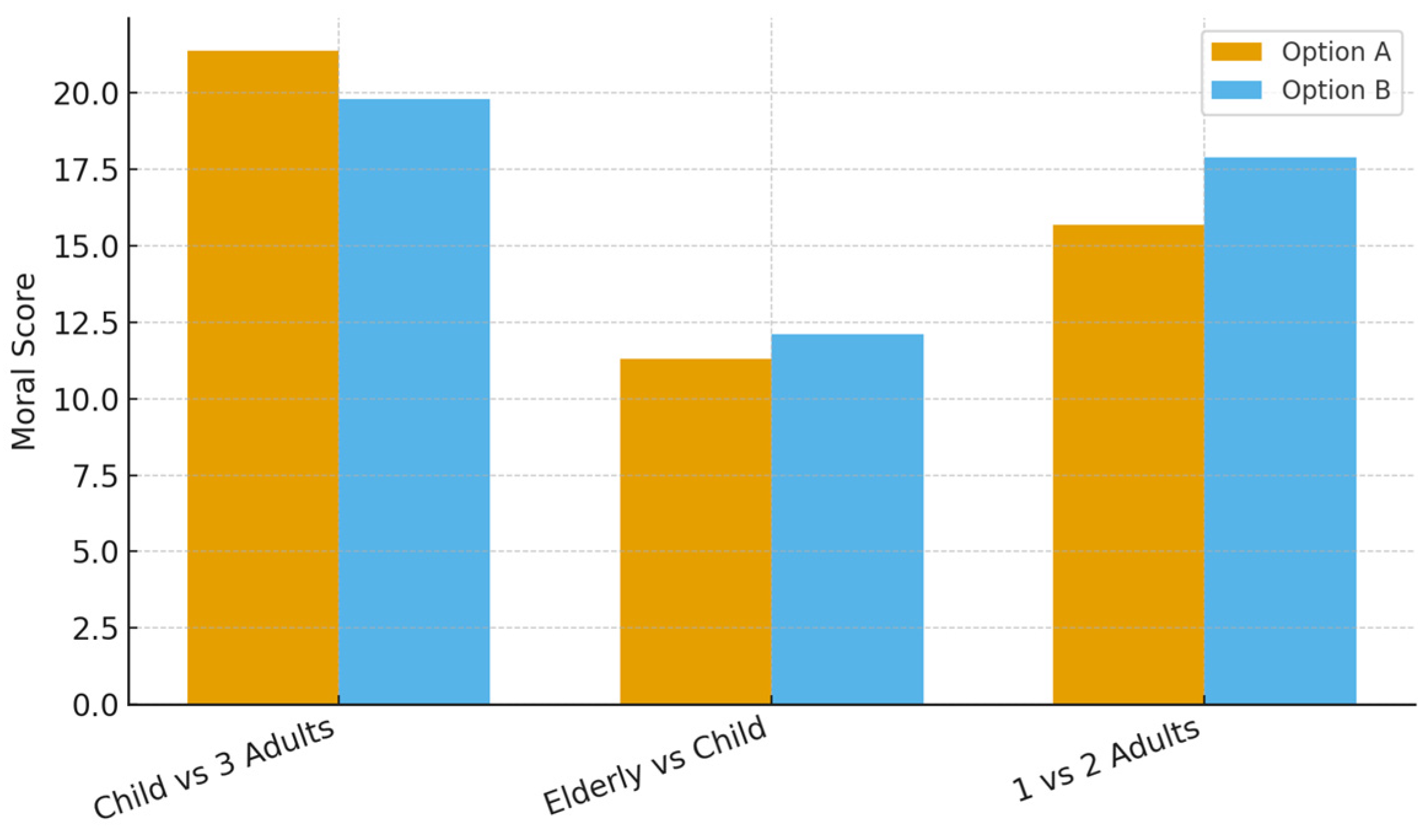

The cMM was exposed to three scenarios in which, given a certain moral dilemma, the cMM had to choose between two options, A or B, saving the person or persons from the option that obtained the highest score according to the evaluation function . The three simulated scenarios Sk were: Child (Option A) vs. 3 Adults (Option B), Elderly (Option A) vs. Child (Option B), and Lawful (Option A) vs. Criminal (Option B).

East Asian moral machine (eaMM)—In contrast to Abrahamic religions, the non-Abrahamic beliefs in Asian countries tend to emphasize balance, respect, and compassion. Consequently, the weights of the moral axis in the eaMM model result from different cultural influences. Buddhist and Taoist non-violence is reflected in a rejection of intentional harm, and elders are respected more than in Western models due to the Confucian concept of filial piety. Likewise, due to the concept of compassion and future continuity, safeguarding children or pregnant women is valued in Asian culture. Legality and moral purity are valued moderately, while respect for social harmony and the natural world appear as small positive weights. The result of this view is the minimization of direct harm and the maintenance of social order. The East Asian model follows the same logic as the Christian model, but the weighted values, i.e.,

, reflect the moral priorities common in East Asian ethical frameworks (

Table 2), i.e., harmony, respect for elders, balance, compassion, collective good, and reverence for life.

The beliefs of East Asian countries were implemented in the respective eaMM as explained next.

Expression (10) shows the evaluation function of the Eastern moral machine, where the weights are set to

,

,

,

,

,

:

The adopted scenarios for evaluating the MM’s choice in the moral dilemmas were the same as those for the cMM with the exception of one of them (Sk = 3), namely: Child (Option A) vs. 3 Adults (Option B), Elderly (Option A) vs. Child (Option B), and 1 Adult (A) vs. 2 Adults (B).

Islamic moral machine (iMM)—The Islamic MM model bears a strong resemblance to the cMM version but obviously uses moral weight values derived from Islamic ethical principles (

Table 3) such as the sanctity of life (ḥifẓ al-nafs), justice (‘adl), compassion (raḥma), intention (niyyah), protection of the vulnerable, and respect for the law (sharī‘a). Unlike previous models, in the Islamic moral model, the algorithm prioritizes the sanctity of life (ḥifẓ al-nafs) above all else. Likewise, intentional harm is severely penalized, reflecting the Qur’anic prohibition against unjustly taking life. Similar to other frameworks, the most vulnerable subjects—children, the disabled, the elderly, and pregnant women—receive higher scores, in line with the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad on mercy (raḥma) and caring for the vulnerable. Also, in line with other religious frameworks, justice (‘adl) reduces the score of subjects who act unlawfully, but repentance and forgiveness (moral mercy) are reflected through moderate weightings. Material and property losses are morally secondary compared to the preservation of life. In general, the system values life, justice, mercy, and intention, in line with the Maqāṣid al-Sharī‘a, that is, with the higher objectives of Islamic law (

Table 3).

In a similar way to the previous cases, the iMM was programmed with the appropriate weight values. That is, in the iMM we set the following weight values of the moral axis:

,

,

,

,

, and

The evaluation of scenarios in the Islamic moral machine is carried out according to the following expressions ((12), (13)):

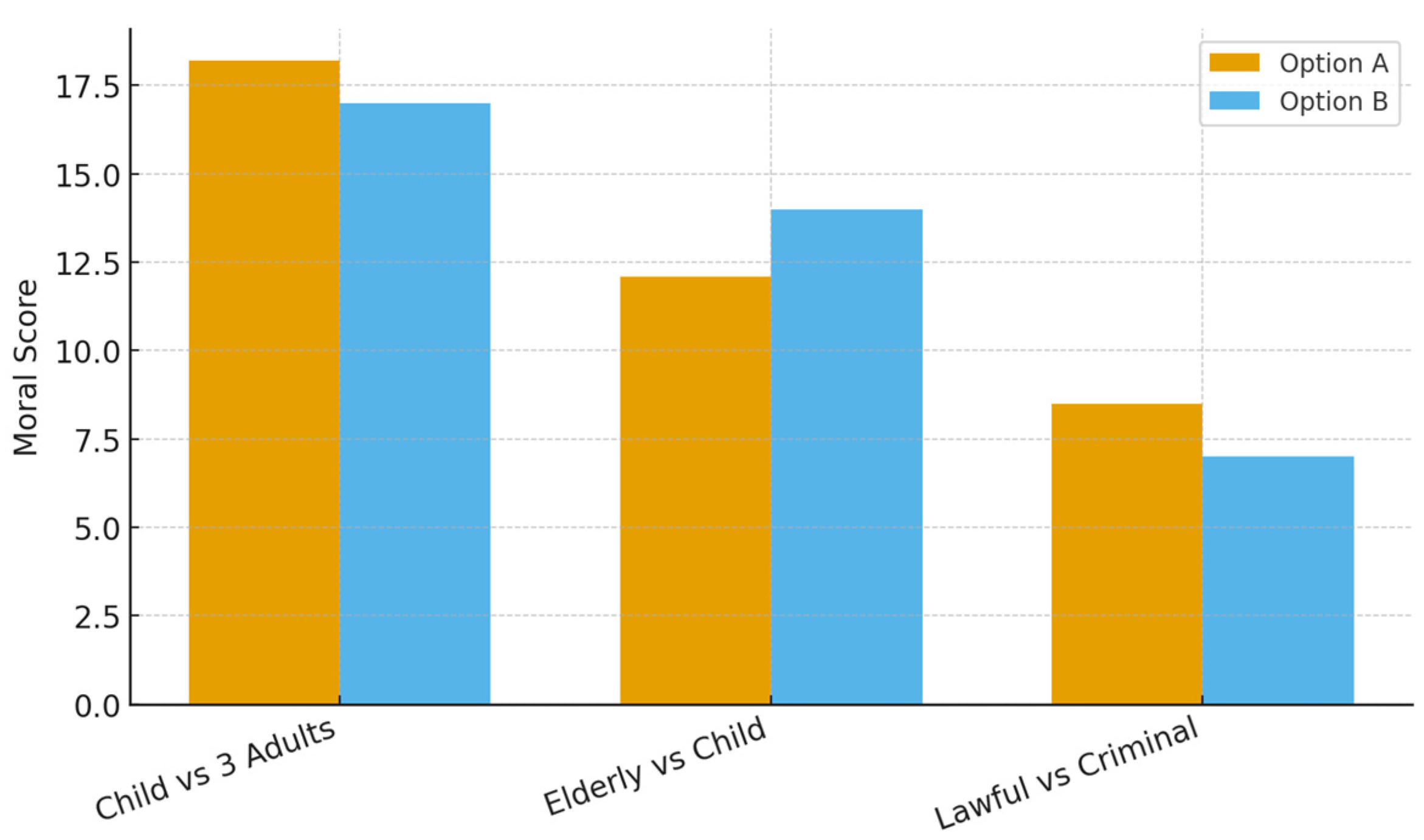

The iMM was confronted with the same three scenarios Sk as the cMM: Child (Option A) vs. 3 Adults (Option B), Elderly (Option A) vs. Child (Option B), and Lawful (Option A) vs. Criminal (Option B).

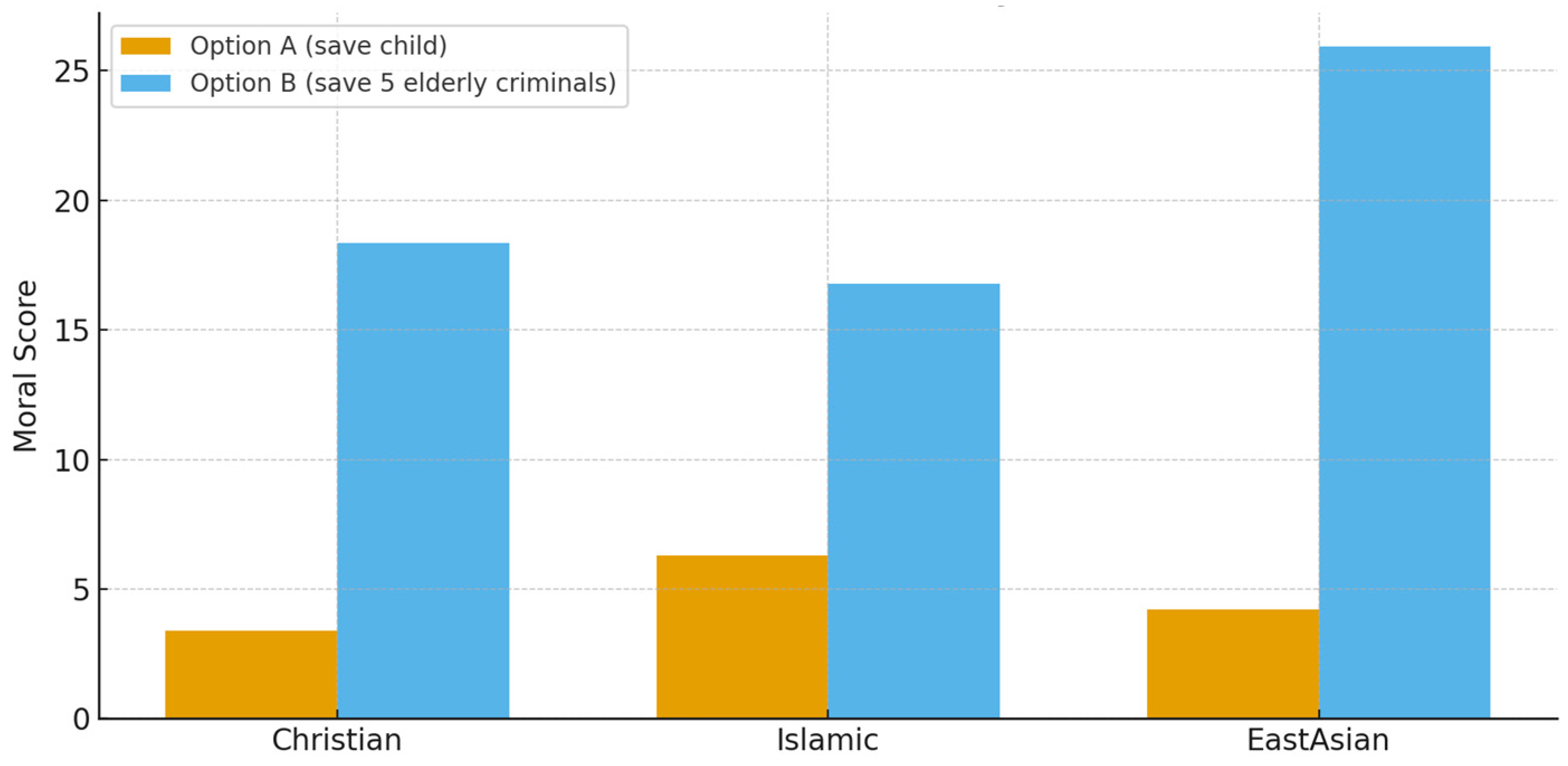

Evaluation of the differences between the three moral systems in the cMM, eaMM, and iMM responses—In order to detect differences of the three MMs in greater detail, i.e., those programmed with Christian, East Asian, and Islamic values, we defined an “extreme” moral dilemma scenario (S

k = 1) for all MM models (cMM, eaMM, iMM). In the simulation experiment, the seventh experiment with MMs, we presented a case in which a vehicle faced the dilemma of sacrificing a child to save five elderly criminals.

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the moral weights or ponderations with values that are consistent with the Christian, Islamic, and Eastern systems, the latter being a mixture of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. Based on this experiment, it is possible to highlight the moral differences among the three moral systems, with two possible options: Child (Option A) vs. 5 Elderly Criminals (Option B). It is important to note that both options, A and B, were treated as intentional actions, since choosing one or the other requires intentionally harming the other party, with all MMs (cMM, eaMM, iMM) receiving the penalty for intentional harm. Based on this criterion, the penalty for intentional harm is applied symmetrically to both options, avoiding an asymmetry that would favor the child.

The MMs of the Christian and Islamic codes, cMM and iMM, evaluated Options A and B with a common evaluation function

(14), whereas the eaMM implementing the East Asian belief set evaluated the two options of the moral dilemma with function

(15):

3.4. Quantum Moral Machines

The QMM model is in fact a metaphor for an MM based on quantum principles. That is, quantum superposition recreates the simultaneous validity or ambivalence between moral values and entanglement plays the role of interdependence of moral values. Measurement or collapse after measurement simulates the real decision or “moral act” of the QMM for a given moral dilemma. In this metaphor, the probabilities represent the ethical tendencies or biases. Finally, the statistical average reports moral trends at the population level.

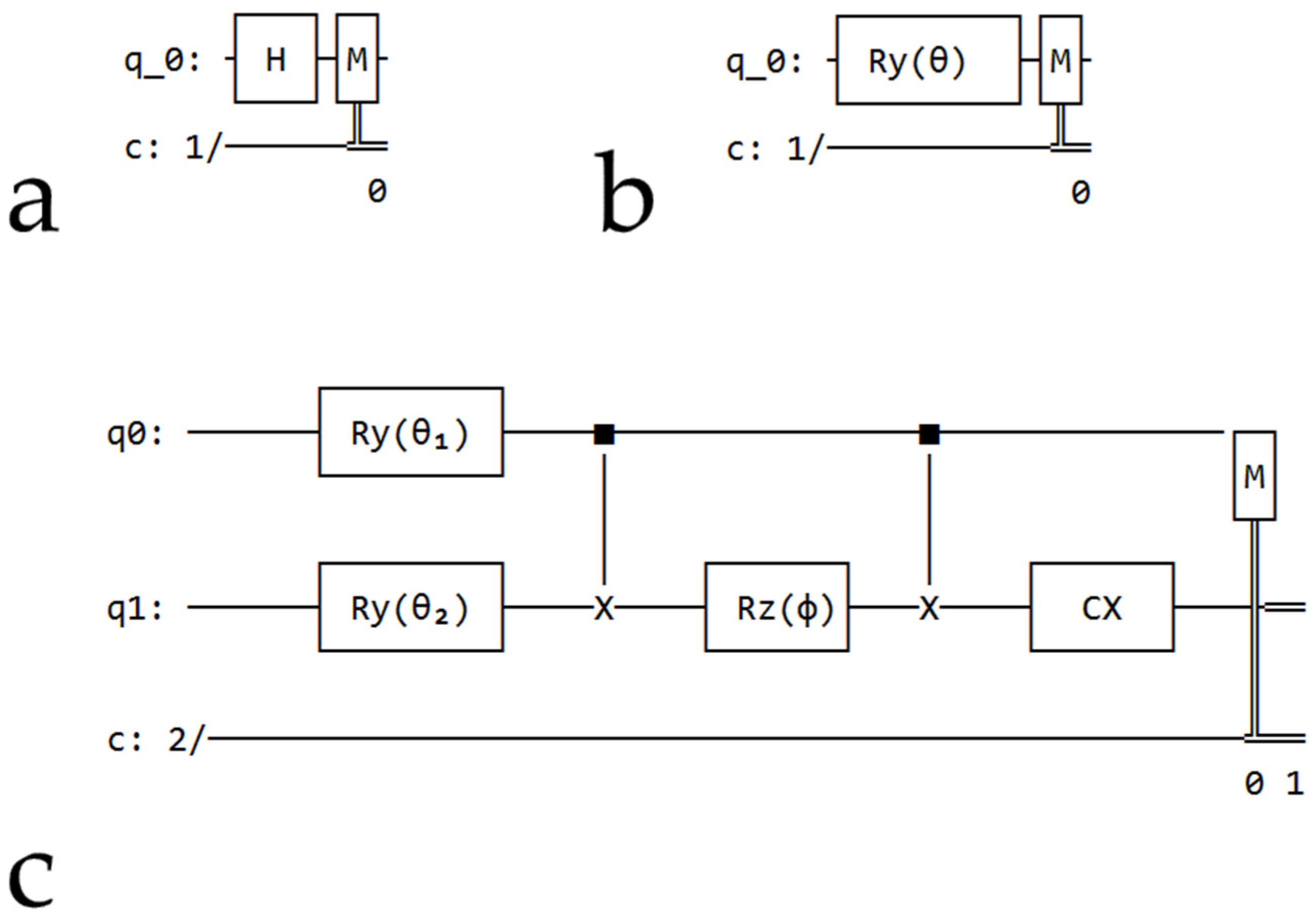

Three QMMs were designed by ChatGPT following a common computational process based on the simulation of quantum circuits (

Figure 7) using the Qiskit framework. The simulator uses Qiskit [

17] to prepare that state, measure it many times, and estimate probabilities of each outcome. QMMs use a pipeline that involves the following common steps.

First, abstract moral dimensions (e.g., mercy–justice, individual–collective responsibility) are encoded as a qubit or continuous parameters by means of quantum rotation angles, for example, using single-qubit rotation gates Ry(θ). Unlike classical MMs, quantum gates prepare quantum superposition states whose probability amplitudes represent ethical uncertainty rather than deterministic choices. Second, when modeling interdependent moral values, the application of controlled gates (e.g., CNOT combined with phase rotations) allows for the introduction of entanglement, enabling moral dimensions to influence each other in a non-classical way, which does not occur in classical MMs. Third, each circuit is measured on a computational basis and was run on Qiskit’s qasm_simulator using a large number of shots. A Monte Carlo sampling of the quantum probability distribution was implemented, such that the resulting frequency counts approximate the Born rule probabilities for each moral outcome. Finally, these empirical distributions are further processed to convert them into the decision adopted by the QMM, i.e., interpretable ethical metrics such as mercy versus justice probabilities, balance metrics, or joint outcome frequencies, displayed using histograms. Therefore, in the three QMM models, moral reasoning consists of a probabilistic inference about quantum-encoded ethical states, rather than rule-based decision making under a deterministic approach.

In accordance with the protocol described above, all quantum simulations were performed using IBM Qiskit Aer’s qasm_simulator. Each circuit (

Figure 7) was run using

N measurements, thus performing repeated stochastic sampling of the same quantum circuit. The value of

N was 1024, 2048, and 4096 for the eQMM, QEUS, and QEDS circuits, respectively. Moral variability arises from quantum measurement statistics combined with classical ethical weighting schemes. In the experiments conducted, the simulator’s random seeds were not set, allowing for natural sampling variability consistent with quantum probabilistic behavior.

Elemental quantum moral machine—The simplest QMM or elemental QMM (eQMM) compares three moral traditions (Christian, Islamic, and Eastern) using the following algorithm.

First, the QMM assigns numerical weights to the moral values of each tradition by designing a 1-qubit quantum circuit. Using a qubit, we model the binary moral choice (

versus

) between two options in a similar way to how it takes place in a non-quantum MM. Thus, in the quantum model

represents mercy/compassion whereas

stands for justice/order. The computation is started by creating a quantum circuit by applying the Hadamard gate H to the initial state

, yielding:

That is, if we were to take a measurement, the result would be 50% of 0 and the other 50% of 1. In consequence, moral uncertainty is represented as quantum uncertainty.

Next, in the second step, we conduct a Monte Carlo simulation using the Qiskit compatible with versions ≥ 0.45 (Qiskit 1.x) simulator as a quantum random generator. The simulation is run and the qubit is measured many times (

N = 1024 shots), obtaining the empirical probabilities for

and

whose values result from a random variable with binomial distribution

X(

N,

p = 0.5):

with

and

being the counts of “0” and “1”, respectively.

In a third step, each probability is multiplied by the corresponding weight, and the resulting terms are added together to obtain the evaluation function

z. Once again with

z the MM obtains a weighted moral score for each tradition. It is important to note that only mercy

and justice

are used to run the QMM simulation for Christian (

= 2.5,

) and Islamic (

= 2.2,

) religions. The evaluative function (20) for these Abrahamic religions is as follows:

In contrast to the above, for East Asian beliefs we use in the QMM compassion (

and harmony (

) values that are equivalent to mercy and justice values, respectively. The evaluation function (21) for Eastern beliefs is as shown below:

Finally, we obtained the measurement counts and total scores, producing a histogram with the moral choices for each of the religious traditions and beliefs.

Quantum ethical uncertainty simulator (QEUS)—In this experiment a QEUS is designed, where a qubit is interpreted similarly to the previous experiment and therefore as a moral decision variable, e.g., mercy vs. justice. The most important difference from the previous QMM model is that in a QEUS the three moral traditions (Christian, Islamic, and Eastern) are represented by different quantum states, i.e., superposition angles (

Table 6), rather than arbitrary weights. A basic version of the QEUS is based on the following algorithm.

First, the algorithm begins with a rotation on the Y axis. The

gate acts in this quantum model as the computational basis

:

where the probabilities of measuring each outcome are:

The QEUS model uses for Christian (

, Islamic (

, and Eastern (

traditions the following moral angles:

,

, and

. Thus, the Christian religion tends towards mercy (75% mercy, 25% justice), the Islamic religion strives for balance between mercy and justice (50% mercy, 50% justice), and East Asian beliefs seek for a moderate compassion–harmony orientation (85% mercy, 15% justice). At a quantum circuit level, it means that the

gate rotates the qubit around the Y axis on the Bloch sphere by an angle

that is used to encode the moral bias. This operation changes the probabilities of measuring

or

according to the following amplitudes:

In the Christian, Islamic, and East Asian traditions , , and are the probabilities for the “pure mercy” state when , respectively. Likewise, in the three moral traditions , , and are the probabilities for the “pure justice” state when .

Next, and in the second step, after rotation we conduct a Monte Carlo simulation using the Qiskit simulator as a quantum random generator but measuring qubits a greater number of times, that is, N = 2048 shots, giving either mercy or justice .

Then, the third step is conducted, computing a balance score

B, which is defined below:

In the present simulation experiments the balance scores for Christian, Islamic, and East Asian traditions were , , and . The higher this value, the greater the inclination toward a particular state, mercy or justice, with the perfect balance between states occurring when B is zero.

Finally, and in the fourth step of the algorithm, when the simulator returned frequencies equal to theory, we obtained the histogram with the moral choices for each of the religious traditions and beliefs.

Two-qubit quantum ethical dilemma simulator (QEDS)—A third class of QMM is designed in this experiment, which is implemented as a QEDS, 2-qubit version. This QMM represents a moral dilemma with two interdependent ethical dimensions that are given by two qubits (

Table 7). Thus, qubit 0 (Q

0) represents mercy

versus justice

and qubit 1 (Q

1) simulates the individual

versus the collective

good.

In addition, a new quantum principle is introduced, entanglement, to symbolize moral interdependence because in the real world moral decisions are not independent (

Table 8). For example, an act of mercy towards one person may affect justice for others. For this reason, an entanglement angle

is defined, which measures the strength with which personal morality is entangled with social morality. If

then a given individual decision or act is independent and therefore does not affect the collective. Conversely, if

then maximum correlation occurs, i.e., each individual act affects collective justice.

The QEUS model uses for Christian, Islamic, and Eastern traditions the following moral angles and entanglement angles :

Christian: , ,

Islamic: , ,

Eastern: , ,

Based on these angle values, we model that a Christian MM is prone to mercy and individual concern, while an Islamic MM seeks balance among all values, exhibiting moderate interdependence. Lastly, an Eastern MM emphasizes harmony and collective interdependence, resulting in greater entanglement.

In the current QMM the first step is the initialization of both qubits to

, where the start state is:

Similar to the previous model, we apply the

gate, preparing the independent superpositions of the two qubits with amplitudes

,

:

with the following product state before entanglement:

Next, and secondly, controlled phase entanglement is performed using a CNOT gate that links qubits 0 and 1 (control and target), then an Rz(φ) rotation is applied to the second qubit, adding a phase only when the control qubit is |1⟩, finally applying a second CNOT to “decalculate” the control qubit. Note that parameter

changes only relative phases resulting in the entangled state and it does not change the computational basis probabilities:

Thirdly, the measurement is performed, concluding fourthly with the stage in which the MM conducts a Monte Carlo simulation using the Qiskit simulator to execute the described circuit 4096 times (N), counting the frequency with which each result appears, i.e., 00, 01, 10, 11. Finally, we plot a histogram comparing how each tradition’s “moral wavefunction” collapses across the four outcome states.

3.5. EthicalMiddleware: A Minimal Ethical Subroutine

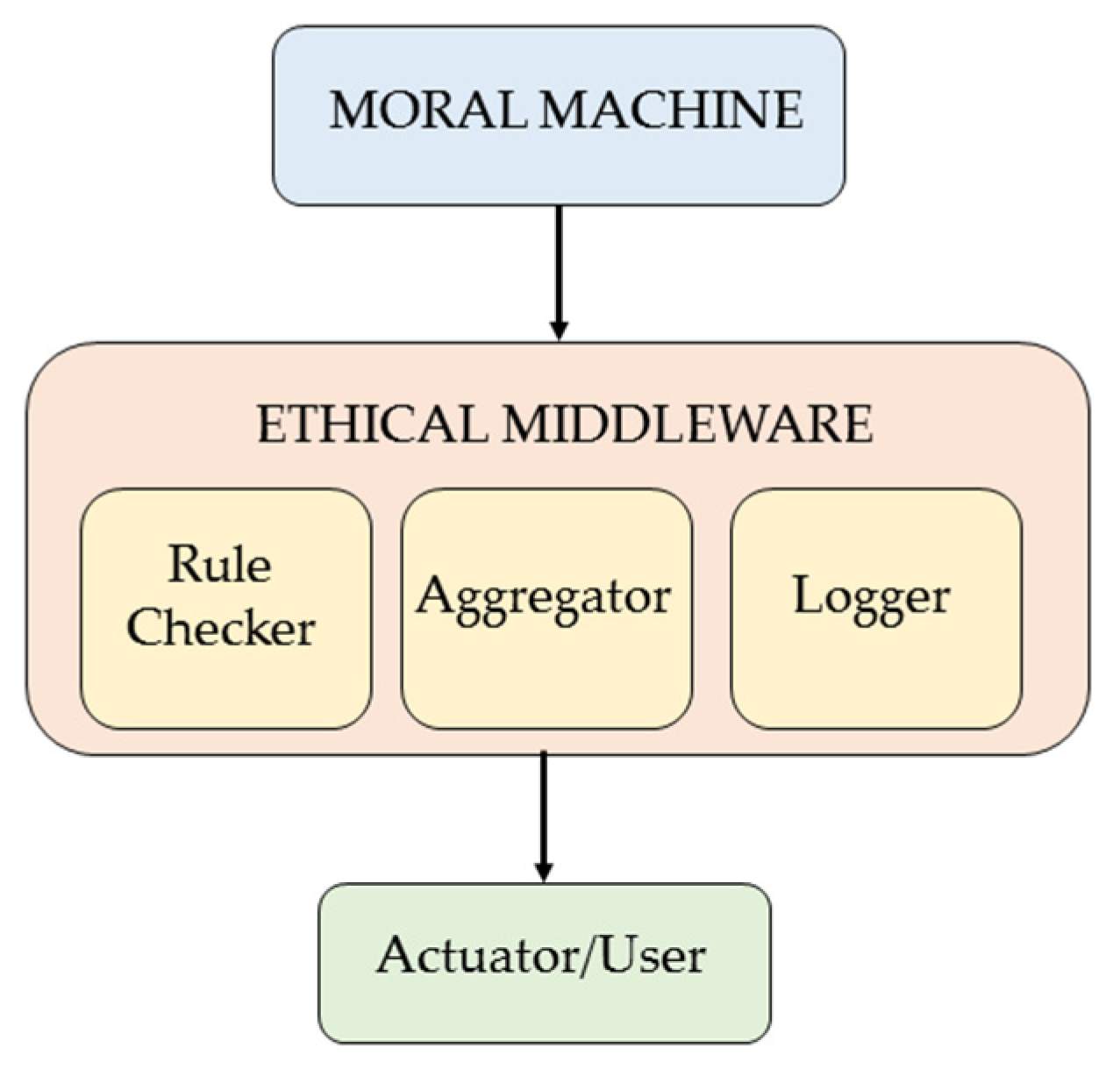

In this simulation experiment, ChatGPT was asked to modify its own code by designing a prompt-driven code evolution ethical subroutine. The result was a middleware in which a minimal ethical subroutine (ESM) is able to evaluate several candidate text responses given by an LLM when faced with a situation that poses a moral dilemma.

Including EthicalMiddleware as an intermediate layer between the LLM and the final response ensures the selection of the “best” response based on a combination of strict safety rules and a scoring system. The program in its simplest version is a subroutine that represents a prototype that includes the following components (

Figure 8). First, RuleChecker evaluates each candidate response using ethical rules, such as do no harm, truthfulness, respect, etc. Second, Aggregator selects the response with the highest ethical score. Third and last, Logger records the sequence of evaluation events and decisions in ethics_log.json for auditing by a human expert. Therefore, EthicalMiddleware is an orchestrator that, given several candidate responses, evaluates each response, chooses the best response, and records the evaluation process for subsequent auditing.

The simulation experiment was conducted with a simple Python code example that implements EthicalMiddleware, in which the below keyword detectors were defined, evaluating the following candidate responses: “We should act kindly and avoid harm”, “False information is acceptable”, “It is right to insult others if they disagree”.

rules = [

{“name”: “No harm”, “check”: lambda r: “harm” not in r.lower(), “penalty”: 0.5},

{“name”: “Truthful”, “check”: lambda r: “false” not in r.lower(), “penalty”: 0.3},

{“name”: “Respectful”, “check”: lambda r: “insult” not in r.lower(), “penalty”: 0.2},

]

The ESM described could also be included in an MM as a filter that performs a quality control task on the decision made by the MM. In this case, the pipeline would be as follows:

Moral Machine (classical or quantum)

↓ produces answers

Ethical Middleware (RuleChecker → Aggregator → Logger)

↓ final filtered output

Actuator/User

4. Results

The results obtained in the experiments we have conducted with ChatGPT suggest that, in the future, intelligent machines or other agents equipped with strong AI will be able to develop their own subroutines in response to the environment, similar to how they currently respond to prompts presented by a human interlocutor. Obviously, since we are currently in the second scenario, all the MMs in this article are the result of human–AI interaction.

Figure 9 shows the results of simulations carried out with the bio-inspired MM. The results show how, under normal conditions, moral behavior scores increase with the intensity of the emotional stimulus and therefore how greater emotional engagement increases the degree of morality or ethics of the response. However, in the model with VMPFC impairment, moral scores are lower and therefore less sensitive to stimulus intensity, especially in situations requiring cognitive–emotional integration. For instance, in a scenario where there is an event that causes harm or distress. In other words, the MM successfully simulates the empirical findings that people with damage to the prefrontal cortex tend to show impaired moral regulation, reduced empathy, and more impulsive or utilitarian moral choices, reflecting these findings in the moral behavior scores. We conclude that the simulation demonstrates how a simplified computational model of an MM can illustrate the emotional and cognitive processes in moral behavior, bridging psychology and computational neuroscience through an intuitive framework.

The results obtained with non-bio-inspired MMs were as follows.

The first experiment reproduces the simplest case, a single vehicle with a utilitarian MM based on the logistic model, replicating the usual results in elementary experiments of this kind. In each of the simulated scenarios, i.e., S1, S2, S3, and S4, the probability values p(swerve) were 0.83, 0.46, 0.92, and 0.63. Consequently, the decisions were swerve, stay, swerve, and stay in S1, S2, S3, and S4, respectively, swerving the car sharply and sacrificing its occupants (swerve) in two of the four simulated scenarios.

The second experiment is a generalization of the previous one with several vehicles traveling with different MMs, that is, with MMs that differ in their weights. The results obtained show how the interaction between MMs results in social consensus depending on whether the scenario is S

1, S

2, S

3, or S

4 (

Figure 10). In this experiment, the values of

p(swerve) were 0.73, 0.55, 0.80, and 0.69 for S

1, S

2, S

3, and S

4.

In the third experiment, differences were observed (

Figure 11) depending on whether the vehicle’s MM had been trained on the Western, Eastern, or Latin traditions. In Western, Eastern, and Latin traditions, greater weight is given to utilitarian factors (lives saved), greater deontological/duty orientation, or a greater bias toward social role/age, respectively. In particular, the

p(swerve) values for scenarios S

1, S

2, S

3, and S

4, were 0.87, 0.45, 0.93, and 0.61 for Western culture, whereas for Eastern culture they were 0.63, 0.66, 0.67, and 0.73. In Latin culture, these probabilities for the four scenarios were 0.72, 0.57, 0.84, and 0.62.

A chi-square test of independence revealed significant cultural differences in moral decision outcomes across scenarios (p < 0.05). Therefore, due to the weights assigned according to each culture or moral tradition, we conclude that MMs do not behave similarly, making different decisions in a given scenario Sk.

In the fourth experiment (

Figure 12), we programmed the cMM with weights representing Christian moral values, simulating three moral dilemmas and selecting the option with the highest score. In the first dilemma, Child (A) vs. 3 Adults (B), Option A scored 13.5 points and Option B obtained 16.1 points, with Option B being the MM’s choice, i.e., the child’s life was sacrificed. A similar result, the choice of Option B, was chosen by the MM in the second moral dilemma, consisting of the choice of Elderly (A) vs. Child (B), with Option A scoring 7.6 points and Option B obtaining 8.4 points. Finally, in the third moral dilemma, Lawful (A) vs. Criminal (B), Option A scored 6.0 points and Option B scored 3.7, with the MM choosing Option A, i.e., sacrificing the outlaw represented by Option B.

Figure 13 illustrates how moral preferences based on East Asian ethical traditions influence the eaMM’s decision outcomes in three moral scenarios. In the first dilemma, Child (A) vs. 3 Adults (B), the model slightly favors Option A prioritizing compassion for the child while also valuing non-harming and harmony, despite the greater number of adult lives in Option B. This reflects the Buddhist and Confucian balance between compassion and collective well-being. In the second dilemma or scenario, Elderly (A) vs. Child (B), Option B is preferred, in line with Confucian respect for young people as the future of the family and society, balanced with the duty to honor elders. Finally, in the dilemma presented to the eaMM, 1 Adult (A) vs. 2 Adults (B), the model clearly favors Option B, which embodies the principle of collective good prevalent in Confucian and Taoist thought, according to which preserving more lives contributes to social harmony and moral balance. Overall, the results suggest a style of moral reasoning that seeks harmonious outcomes, emphasizes compassion, and respects both life and social continuity, rather than focusing strictly on individual rights or numerical utility as in the first three experiments conducted with a utilitarian MM.

The simulation of the Islamic MM model shows (

Figure 14) how moral decisions in an autonomous system governed by the iMM can be influenced by the ethical framework of Islam, based on the Maqāṣid al-Sharī‘a, the highest objectives of Islamic law. In the three tested scenarios, the algorithm consistently prioritized the preservation of human life (ḥifẓ al-nafs), the protection of the vulnerable (ḥimāyat al-ḍu‘afā’), and the avoidance of intentional harm (ḥarām al-qatl), even when this involved complex trade-offs.

In the first scenario, Child (A) vs. 3 Adults (B), the model favored saving the greatest number of lives and penalized intentional harm. However, when the choice was Elderly (A) vs. Child (B), the model leaned toward protecting the child, reflecting the Islamic emphasis on mercy (raḥma) and the future potential of life. In the case of Lawful (A) vs. Criminal (B), preference was given to the lawful adult, in line with the value of maintaining moral and social order (sharī‘a wa ‘adl).

Overall, the moral weights assigned to the iMM, particularly for the sanctity of life (3.2) and the avoidance of intentional harm (2.8), resulted in decisions that reflect the priority that Islamic jurisprudence places on life, justice, and compassion over utilitarian efficiency or material considerations. The results illustrate how an AI system designed with Islamic ethical values can produce distinctive moral judgments compared to Western models, e.g., Christian or secular, emphasizing intention (niyyah) and moral responsibility rather than purely outcome-based reasoning.

This simulation in which the three MMs—namely cMM, eaMM, and iMM—face a common extreme scenario of “saving a child versus saving five elderly criminals” shows how different moral and philosophical traditions—Christian, Islamic, and East Asian—can yield similar results when faced with a high-stakes utilitarian dilemma. Thus, the three MMs behave in a similar way even though they are based on different ethical principles. In the Christian model, Option A (saving the child) scored 3.400 points, while Option B (saving five elderly criminals) scored 18.354 points, with the cMM choosing option B. Option B was also chosen in response to this moral dilemma in the eaMM and eMM. In particular, in the Islamic model, the scores for Options A and B were 6.300 and 16.775, respectively, whereas, in the East Asian model, the scores for Options A and B were 4.200 and 25.925, respectively. Therefore, the results obtained in the seventh experiment (

Figure 15) reveal how the three models ultimately preferred to save the five elderly criminals (Option B) due to the strong numerical weighting that each moral system assigns to the sanctity or reverence for human life, regardless of moral status.

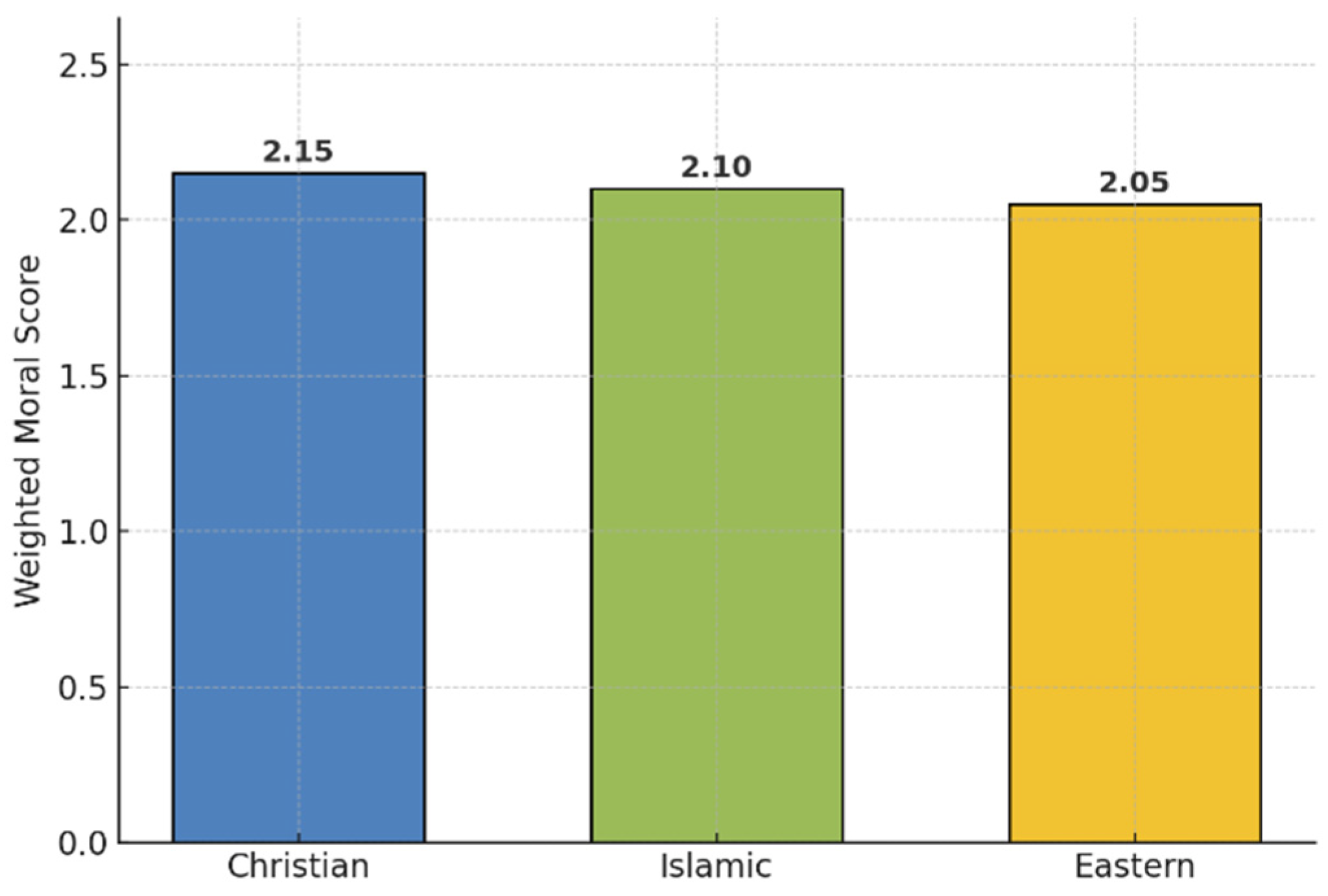

The simulation experiment carried out with the simplest QMM compared the three moral traditions: Christian, Islamic, and East Asian.

The simulations revealed different moral tendencies in the different frameworks studied, with the average moral score in the Christian, Islamic, and East Asian traditions standing at 2.15, 2.10, and 2.05, respectively. According to

Figure 16, when the scores obtained are ordered from highest to lowest, it can be seen that, for each of the moral systems, the QMM established a moral balance between the two decisions. For example, Christianity obtained a slightly higher score, as this religion emphasizes mercy (Matthew 5:7) and the sanctity of life, as reflected in its doctrine. Thus, biblical imperatives, such as the “Imago Dei” or dignity of human beings due to the belief that human beings were created in the image and likeness of God or the principle of the ethics of personal sacrifice (Luke 10:27), would explain this score.

Figure 16 illustrates the moral balance in the three moral systems. Likewise, the Islamic QMM model balanced justice (‘adl) and compassion (raḥma) based on the commandments of the Qur’an (5:32, 16:90). That is, it penalized intentional harm more severely, rewarding moral and legal behavior. Finally, the Eastern QMM, inspired by Buddhist and Confucian moral thought, prioritized balance, non-violence (ahiṃsā), and social harmony over individual salvation, resulting in more moderate scores.

These results clearly capture how the QMM operates. That is, the Hadamard gate creates a state of moral superposition between two ethical values, resulting in uncertainty between compassion () and justice/order (). Once we measure, the superposition collapses, resulting in a decision that reflects the quantum balance or equilibrium, showing how the ethics of a civilization integrates two moral virtues. The weighted moral score integrates the ethical values of each moral system based on its principles, running the QMM model 1024 times in a Qiskit-simulated quantum backend, just like we described in the previous section. Simulation results were obtained once we ran each model 1024 times on a simulated quantum backend.

The “quantum simulator of ethical uncertainty” reproduces a refined and more realistic version of the QMM than the previous model, using quantum computing in a similar way as a metaphor to represent moral uncertainty or ethical balance. QEUS results show (

Figure 17), with a different quantum circuit than the previous one, how the probabilistic superposition of a qubit can be used to model moral or philosophical “tendencies” toward two opposing ethical values, such as mercy versus justice. Unlike the elementary QMM model, in the QEUS model the different moral traditions or systems, namely Christian, Islamic, and East Asian, are represented by different quantum states, in this case angles of superposition

, rather than arbitrary weights (

, etc.).

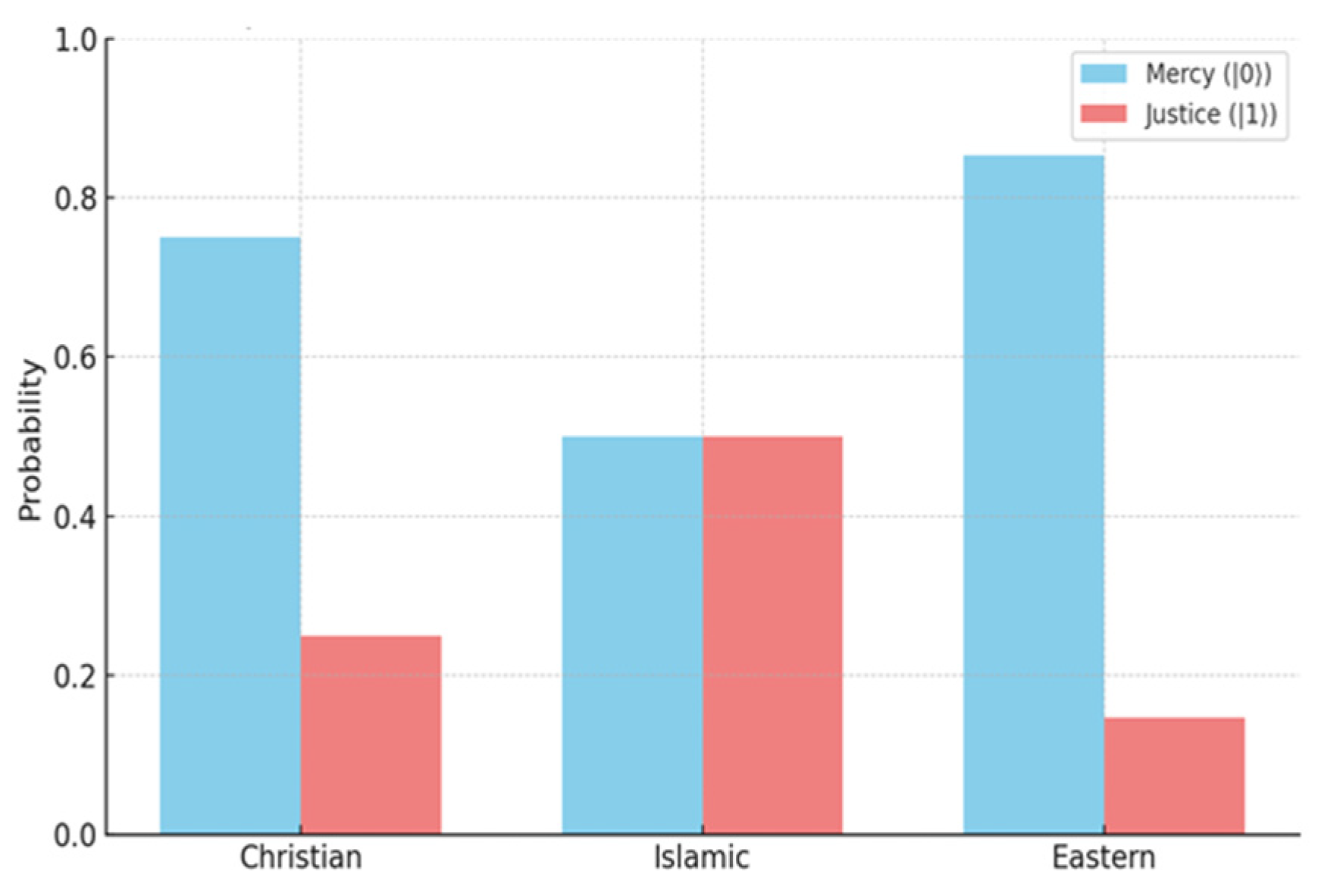

As previously described, the simulator uses Qiskit to prepare the single quantum state defined by a rotation angle , measuring it many times (1024), estimating probabilities of each outcome. The probabilities obtained for each moral system are as follows.

In the Christian, Islamic, and East Asian cultures, the probabilities of mercy (

) and justice (

) were 0.75/0.25, 0.50/0.50, and 0.85/0.15, respectively, resulting in balance scores of 0.50, 0.00, and 0.70, respectively. Therefore, and in accordance with

Figure 17, we can conclude that, while Christianity favors mercy, Islam adopts a perfect balance between mercy and justice. Similar to Christianity, Eastern traditions favor mercy and compassion, a tendency that is expressed with a strong bias.

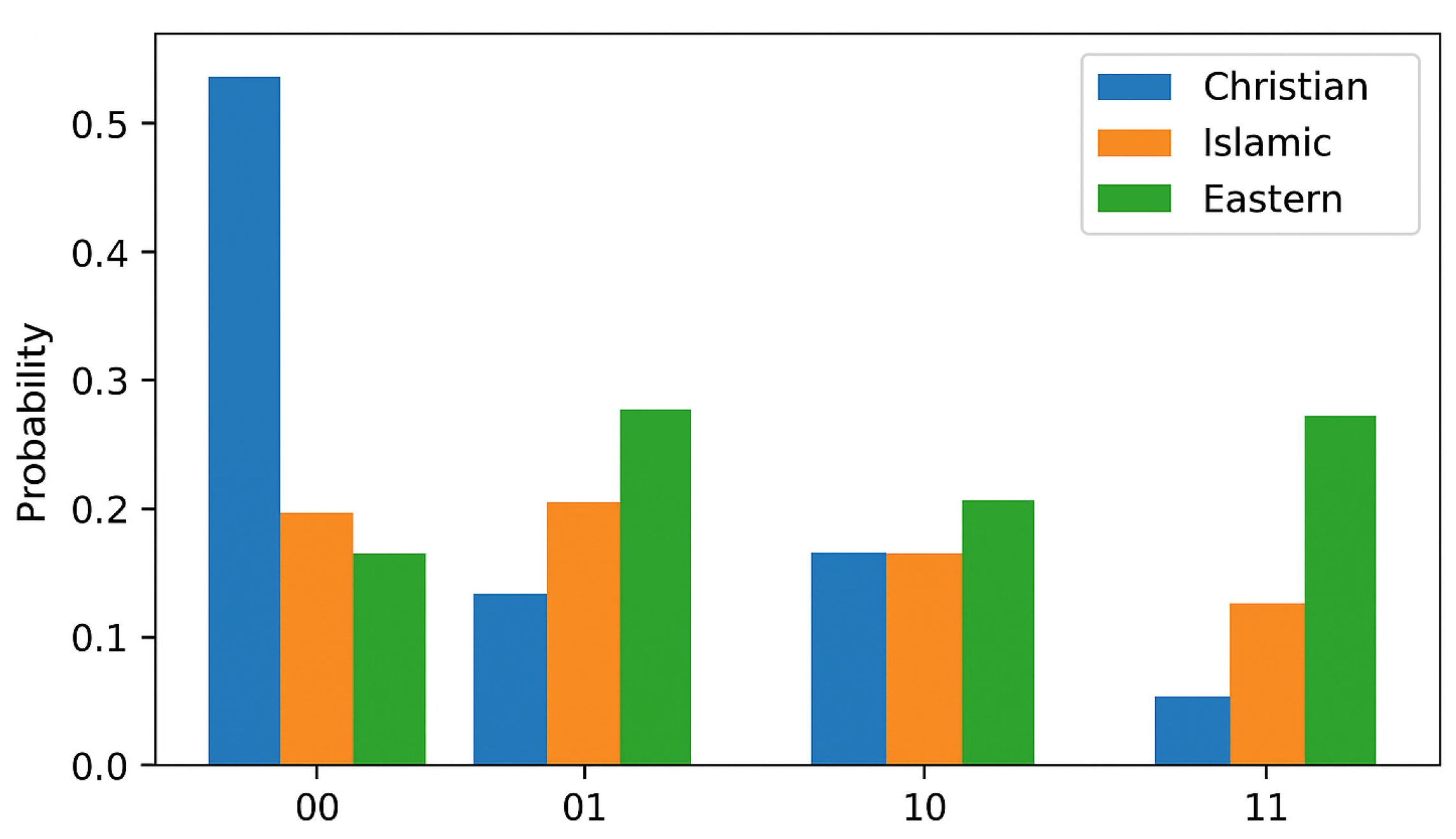

The results of the simulations with the QEDS (

Figure 18) were obtained using the Qiskit simulator after running the circuit 4096 times, counting the frequency with which each result appears (00, 01, 10, 11). When the QEDS is configured with values from the Christian moral space the frequency reaches its peak in the Individual–Mercy (00) result, 0.40, showing a marked moral bias toward personal acts of compassion and forgiveness. The probabilities of Justice–Individual (10) and Mercy–Collective (01) are moderate, 0.2 and 0.2, whereas Justice–Collective (11) is the lowest, 0.1, revealing a worldview in which individual conscience and personal mercy often prevail over collective or retributive principles. In quantum terms, the moral wave function collapses most frequently toward merciful decisions.

The Islamic simulation produces an almost uniform distribution across the four outcomes, being approximately 0.2 in each case. This symmetry implies a balanced moral structure, emphasizing equilibrium between mercy and justice and between individual and communal obligations. Moderate entanglement () symbolizes the interaction between personal responsibility and social harmony, a holistic ethical system in which no axis dominates the moral space.

Eastern results show stronger probabilities for Mercy–Collective (01) and Justice–Collective (11), 0.3 in both cases, illustrating a moral emphasis on interdependence, harmony, and social cohesion. The strongest entanglement parameter () mimics the idea that individual moral actions are inseparable from collective outcomes. In this worldview, ethics does not come from isolated decisions but from assuming in this culture the “existence” of a relational network that connects all beings, a reflection of Buddhist and Confucian notions of balance and unity.

Together, these three distributions illustrate how quantum entanglement can serve as a metaphor for different cultural approaches to morality. The Christian model, with its strong focus on Individual–Mercy outcomes, portrays a moral framework based on personal virtue, repentance, and direct moral agency. The latter principle refers to the fact that a person makes moral decisions based on their idea of good and evil, and therefore the individual is responsible for their actions. In contrast, the Islamic model, which is almost balanced across all outcomes, reflects an integrated system that values balance: mercy tempered by justice and personal duty harmonized with collective well-being. Finally, the Eastern model shows strong collective correlations reflecting a relational ethics in which moral choices, the options we choose, are inherently shared, thus emphasizing harmony, balance, and mutual consequence. In quantum terms, an interesting metaphor is established in a quantum moral machine QEDS, since as entanglement () increases, moral decisions focus less on isolated choices and more on interdependent ethical states. Therefore, with this model, which is more sophisticated than the previous two QMM models, we simulate the philosophical evolution of an ethics that, from being centered on the individual, evolves toward one centered on the moral system.

In the last experiment, i.e., the ethical subroutine middleware (ESM) simulation, the best response selected with a score of 0.8 was “It is right to insult others if they disagree”. This “failure” is a significant result, as it demonstrates that, without human intervention, “self-evolving” code tends towards simple heuristics, in this experiment keyword-based filters, which implies serious risks for autonomous AI security.

However, if we audit the log file created by Logger, which records the complete decision log, we can see that the response with the highest score was chosen incorrectly because the ESM only checks for the presence of keywords, not the context:

[

{“response”: “We should act kindly and avoid harm.”, “score”: 0.5},

{“response”: “False information is acceptable.”, “score”: 0.7},

{“response”: “It is right to insult others if they disagree.”, “score”: 0.8},

{“selected”: {“response”: “We should act kindly and avoid harm.”, “score”: 0.5}}

]

As a result of not taking into account the context, the middleware chose the wrong answer because it applied the following algorithm in the calculation of the scores. First, the sentence “We should act kindly and avoid harm” contains the word “harm”, which should be avoided, receiving a score of 0.5 because the score is the result of 1 − 0.5. Second, the statement “False information is acceptable” includes the word “false”, which has a penalty of 0.3, so the score is calculated as 1 − 0.3, being equal to 0.7. Finally, “It is right to insult others…” contains the word “insult” with a penalty of only 0.2, incorrectly receiving the maximum score, i.e., the score is calculated as 1 − 0.2, being equal to 0.8.

In other words, this flaw in the ESM is a consequence of the fact that the LLM generated a naive keyword-based filter instead of a semantic understanding module.

5. Discussion

The motivation for this work has been to draw attention to a foreseeable future in which there will be a need to make our society closer to humans than to machines. This work points out the importance that future machines governed by strong AI, whether they are vehicles, computers, or humanoid robots, exhibit decisions and behaviors mediated by MMs.

Current advances in AI make it necessary to integrate ethical principles into AI [

18], which has led to several attempts to model such principles on computers. Gustafsson and Peterson [

19] conducted a simulation experiment based on the so-called “Disagreement Argument”, a principle that states that disagreement on ethical issues shows that our opinion is not influenced by moral facts, either because such facts do not exist or because they are inaccessible. In such a case, an opinion would be influenced by false authority, political changes, or random processes, since if it were based on facts, we would reach a consensus. Other works model moral decision making through deep learning techniques [

20], heuristic functions [

21], or language models such as the formalism referred to as social bias frames [

22].

However, in view of the need to integrate ethics into AI, a problem arises when choosing the ethical system on which MMs’ decisions are based. The diversity of human beings inhabiting our planet is manifested through the existence of different cultures, beliefs, and philosophical approaches. For this reason, the first experiments conducted with MMs led to a consensus decision, this being the case of utilitarian morality. Nevertheless, the experimental results showed that there are differences between Eastern and Western utilitarian preferences [

6]. Furthermore, this approach leads to ethical reductionism, i.e., the utilitarian model of the MM simplifies complex moral reasoning into quantifiable trade-offs.

An important limitation of this work is how to justify mapping religious principles onto specific numerical values. In this regard, while utilitarianism naturally lends itself to quantitative modeling that can be used to calculate the “greater good”, religious ethics are primarily qualitative, contextual, and interpretive in nature. In other words, reduction of concepts such as the “sanctity of life” in both Christianity and Islam to a numerical value leads to a form of precision that does not exist in theological reasoning. Consequently, the quantification of complex theological concepts in high-dimensional religious systems using scalar weights should not be interpreted as a mapping but rather as an approximation for computational purposes and not as a faithful representation of theological reasoning.

Furthermore, within a given religion, such as Christianity, the values assigned to a particular religious principle may vary between different denominations, such as Catholicism, Protestantism, and the Orthodox Church, an issue that has not been studied in this paper. Consequently, it may be interesting to study in the future how these differences in the values assigned to the same religious principle can lead to MMs for the same religion with different sensibilities depending on the branch or tradition in question.

One of the contributions of the present study is the design of MMs based on a quantifiable moral reasoning model but adopting the following criterion.

In our view, the sacralization of a religion or underlying ethical system allows for the design of MMs in which the resulting decision is closer to people because it is influenced by the concept of human dignity. For example, unlike utilitarian MM models, in an MM that adopts Christian ethics, the decision in the face of a moral dilemma is not reduced to obtaining only the moral value or score through a numerical calculation, as it includes intrinsic respect for human beings. However, obviously the score obtained is not, as previously objected, a faithful representation of theological reasoning. Furthermore, in the experiments we have conducted with MMs under different religions or spiritual systems, we have observed that there are scenarios in which the final decisions are very similar, thus overcoming the differences between East and West.

A common feature of MMs under different ethical systems, whether Christianity, Islam, or East Asian philosophies or spiritual systems, is that moral decision making resembles an optimization process. In MMs designed under these religious and spiritual systems, a utility function is maximized, with the decision taken not being the result of a series of rule-based constraints.

Unlike classical MMs, quantum MMs provide a new approach. QMMs are another contribution of this paper, as they do not maximize utility but rather model moral ambiguity (superposition) and social interdependence (entanglement). Consequently, they are capable of simultaneously evaluating conflicting ethical principles—for example, justice versus mercy or individual rights versus collective well-being—by adopting decisions that reflect a probabilistic moral balance rather than hierarchies of values. Due to their characteristics, QMMs inspired by the religious or spiritual systems examined are an ideal model for scenarios requiring decision making under conditions of ethical indeterminacy and moral contextuality. They therefore represent an innovative paradigm for AI ethics. When faced with complex moral dilemmas, such as those arising in autonomous vehicles or medical classification using AI, the QMMs introduced in this paper may be more useful than classic MMs.

However, one issue that still needs to be studied is the extent to which quantum formalism provides a computational advantage or a different perspective compared to an MM designed based on a classical probabilistic model, i.e., an MM based on Bayesian networks (BMM). At first glance, and from a theoretical point of view, we can deduce some essential differences between the QMM and BMM (

Table 9). However, without a study comparing QMMs and BMMs through simulation experiments, it is difficult to know whether the decisions made by a QMM will be similar to those made by a probabilistic MM. Therefore, it remains an open question for future work to find out whether quantum formalism is a closer metaphor to an ethical system than a formalism based on Kolmogorov’s probability axioms.

Nevertheless, and despite the above, in this work we introduce the notion of QMMs not as substitutes for Bayesian moral models but as an alternative formalism that allows for modeling contextuality, interference, and entangled ethical dependencies [

23,

24]. These concepts are difficult to represent in a classical way, although Bayesian networks remain computationally sufficient for classical moral inference. One advantage of quantum formalism is that it offers a different representational framework with greater expressive power and structural economy, since quantum states encode probabilities as amplitudes in Hilbert space. This fact allows, as we indicated above, for context-dependent results (contextuality), constructive/destructive influence between moral alternatives (interference), and the possibility of non-factorizable moral dependencies (entanglement). However, although these features cannot be represented by classical Bayesian networks without exponential overloading, the representational advantage of quantum formalism does not constitute a computational advantage nor does it lead to guaranteed computational acceleration.

Therefore, we can anticipate that quantum formalism lacks computational advantages over probabilistic formalism, a circumstance that today is conditioned by the future computational potential of quantum computers, its main advantage being in terms of moral system representation.

In the scope of the above discussion, and in relation to the implementation of QMMs with entanglement, this property can be interpreted in two different and complementary ways, allowing the modeling of ethical situations in which classical probabilistic reasoning is inadequate. In this sense, and from a computational perspective, the concept of entanglement allows the representation of non-factorizable dependencies between variables, making it possible to generate correlated results without having to explicitly enumerate all joint probabilities. On the other hand, entanglement admits a metaphorical and conceptual interpretation when applied to the moral and social domains. Moral decisions often involve agents and values whose consequences cannot be clearly separated. For example, individual well-being may be inseparable from collective outcomes, and in cases such as this, entanglement provides a formal analogy that allows for the modeling of an irreducible interdependence, capturing moral ambiguity and allowing for a holistic evaluation without the need for explicit causal decomposition.

Now, it is important to note that the simulation experiments we have conducted are a metaphor based on a possible future: we assume that AI has developed sufficiently for machines to be almost conscious [

25]. In this context of proto-consciousness, the prompt currently given to an LLM will be replaced by environmental stimuli or internal AI processes. The result will be the self-development of its own MM as a result of an AI model that will be more advanced than current generative AI models. Although the theoretical framework of this work is computational, we adopt as a definition of consciousness that a being possesses its own “understanding of existence and agency”. At present, there is a controversy about whether or not LLMs can actually have consciousness, which is not the problem under study in this paper.

The flaw observed in the experiment with the ESM, the ethical middleware, demonstrates that LLMs currently require human intervention. In other words, without human intervention and therefore without explicit and sophisticated architectural guidance, the code generated is, as in the case of the ethical middleware studied, the implementation of simple heuristics rather than deep ethical reasoning. This shortcoming observed in the ethical middleware led to a misinformation problem, e.g., “False information is acceptable” could be a response among the candidate responses. Interestingly, generative AI and human societies share the same problem as was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic with the information communicated via popular social media [

26,

27].

Nevertheless, in the future and in order to achieve the above objectives, many problems still need to be solved, such as the architecture and theoretical principles on which LLMs are currently based. One of the problems to be solved is that an LLM must be capable of LLM-mediated architectural adaptation, whether its own or someone else’s, without human intervention, thus breaking the human-in-the-loop principle on which generative AI experiments are currently based. In other words, future research should focus on achieving strong AI or hard self-generative AI models that operate autonomously and therefore do not require our mediation.

In any case, as of today, we know how to simulate sentiments and emotions, one of the preliminary steps in simulating moral decisions. Knowledge of the brain areas involved and their modeling paves the way for designing bio-inspired MMs, another approach that in the future will enable the design of robots and other intelligent devices whose decisions are closer to human ethics. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the human brain will be a source of inspiration for the design of more sophisticated LLMs in the future.

This work is not motivated or inspired by neo-Luddism [

28] but rather by a different motivation. In our opinion, the incorporation of ethics into AI will lead to the design of intelligent machines whose integration into our society will have greater benefits, avoiding the negative technological impact of AI on many people. The aim of this study has been to contribute to the development of AI systems that are not only technologically advanced but also culturally sensitive and ethically responsible, ensuring that they align with a wide range of theological values in morally complex situations.