Abstract

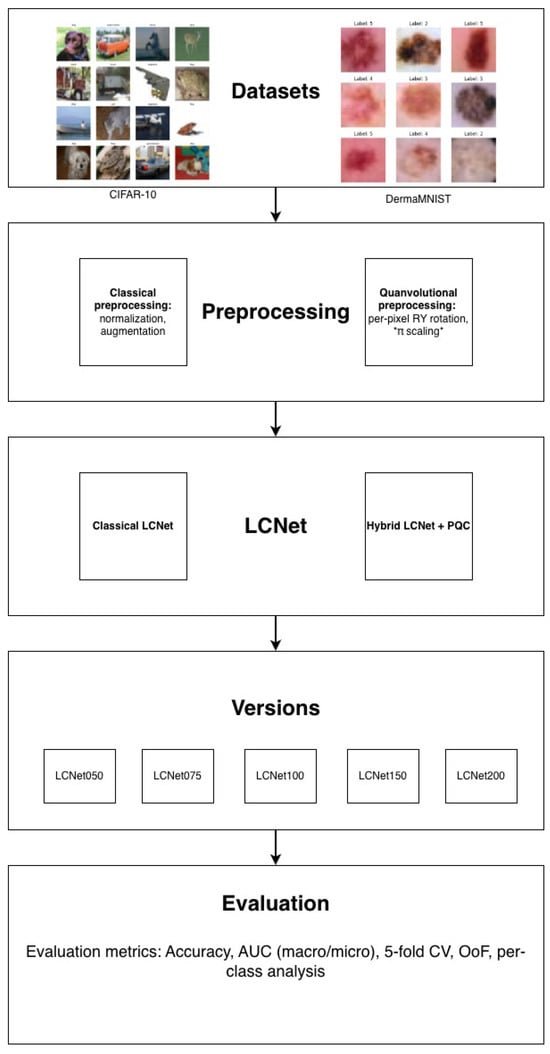

Purpose: While hybrid quantum–classical neural networks (HNNs) are a promising avenue for quantum advantage, the critical influence of the classical backbone architecture on their performance remains poorly understood. This study investigates the role of lightweight convolutional neural network architectures, focusing on LCNet, in determining the stability, generalization, and effectiveness of hybrid models augmented with quantum layers for medical applications. The objective is to clarify the architectural compatibility between quantum and classical components and provide guidelines for backbone selection in hybrid designs. Methods: We constructed HNNs by integrating a four-qubit quantum circuit (with trainable rotations) into scaled versions of LCNet (050, 075, 100, 150, 200). These models were rigorously evaluated on CIFAR-10 and MedMNIST using stratified 5-fold cross-validation, assessing accuracy, AUC, and robustness metrics. Performance was assessed with accuracy, macro- and micro-averaged area under the ROC curve (AUC), per-class accuracy, and out-of-fold (OoF) predictions to ensure unbiased generalization. In addition, training dynamics, confusion matrices, and performance stability across folds were analyzed to capture both predictive accuracy and robustness. Results: The experiments revealed a strong dependence of hybrid network performance on both backbone architecture and model scale. Across all tests, LCNet-based hybrids achieved the most consistent benefits, particularly at compact and medium configurations. From LCNet050 to LCNet100, hybrid models maintained high macro-AUC values exceeding 0.95 and delivered higher mean accuracies with lower variance across folds, confirming enhanced stability and generalization through quantum integration. On the DermaMNIST dataset, these hybrids achieved accuracy gains of up to seven percentage points and improved AUC by more than three points, demonstrating their robustness in imbalanced medical settings. However, as backbone complexity increased (LCNet150 and LCNet200), the classical architectures regained superiority, indicating that the advantages of quantum layers diminish with scale. The mostconsistent gains were observed at smaller and medium LCNet scales, where hybridization improved accuracy and stability across folds. This divergence indicates that hybrid networks do not necessarily follow the “bigger is better” paradigm of classical deep learning. Per-class analysis further showed that hybrids improved recognition in challenging categories, narrowing the gap between easy and difficult classes. Conclusions: The study demonstrates that the performance and stability of hybrid quantum–classical neural networks are fundamentally determined by the characteristics of their classical backbones. Across extensive experiments on CIFAR-10 and DermaMNIST, LCNet-based hybrids consistently outperformed or matched their classical counterparts at smaller and medium scales, achieving higher accuracy and AUC along with notably reduced variability across folds. These improvements highlight the role of quantum layers as implicit regularizers that enhance learning stability and generalization—particularly in data-limited or imbalanced medical settings. However, the observed benefits diminished with increasing backbone complexity, as larger classical models regained superiority in both accuracy and convergence reliability. This indicates that hybrid architectures do not follow the conventional “larger-is-better” paradigm of classical deep learning. Overall, the results establish that architectural compatibility and model scale are decisive factors for effective quantum–classical integration. Lightweight backbones such as LCNet offer a robust foundation for realizing the advantages of hybridization in practical, resource-constrained medical applications, paving the way for future studies on scalable, hardware-efficient, and clinically reliable hybrid neural networks.

1. Introduction

In recent years, deep learning has become the foundation of modern artificial intelligence (AI), achieving high performance across vision, language, and multimodal tasks [1]. Yet, the growing demand for computational power has highlighted the limitations of classical architectures, both in scalability and efficiency. At the same time, the rapid development of quantum computing [2] has opened the possibility of combining classical and quantum paradigms to build hybrid models that may overcome some of these limitations. Quantum machine learning (QML) integrates quantum computing with traditional machine learning. Unlike classical computation, which operates on bits, quantum systems exploit superposition and entanglement, enabling richer representational capacity. A particularly promising direction is the design of hybrid quantum–classical neural networks [3], where parameterized quantum circuits (PQCs) are embedded into deep learning architectures as additional layers. Such models aim to combine the expressive power of quantum circuits with the maturity of classical optimization frameworks. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are natural candidates for hybridization, as they already excel in learning hierarchical visual features. However, CNN backbones differ greatly in structure and complexity. Efficient models such as MobileNet and LCNet, originally designed for constrained devices, appear especially suitable for integration with quantum layers, as their lightweight design aligns with the current limitations of quantum simulators and hardware. This study systematically investigates which classical CNN backbones are better suited for hybrid quantum–classical networks. We focus on two families—MobileNetV3 and LCNet—embedding Ry-based quantum circuits as hidden layers and evaluating them on both a general-purpose dataset (CIFAR-10) and a medical imaging dataset (DermaMNIST). By including DermaMNIST, which contains dermatological images for multi-class classification, we assess not only the theoretical potential of hybrid architectures but also their applicability to sensitive, real-world domains such as computer-aided medical diagnosis.

2. Literature Review and Problem Statement

Quantum machine learning (QML) has rapidly evolved as a field that integrates the representational power of quantum computation with the methodological framework of classical machine learning [4,5,6]. Unlike conventional computation based on binary logic, quantum computation [7,8] operates on qubits capable of existing in superposition and entanglement, thereby enabling richer data transformations and more expressive representational capacity. This paradigm has motivated the development of hybrid quantum–classical architectures [9,10,11,12] that combine parameterized quantum circuits (PQCs) [13] with traditional neural network layers. Within the current technological constraints of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, PQCs—most commonly composed of rotation gates such as —serve as the core mechanism for embedding quantum layers into differentiable models.

Existing research on hybrid architectures dem onstrates both potential and inconsistency [11,14,15]. On one hand, several studies report that the inclusion of quantum layers can enhance performance on small-scale benchmarks such as MNIST or CIFAR-10, occasionally outperforming shallow classical networks and improving generalization. On the other hand, other works have found negligible or unstable benefits, with hybrid models failing to converge or providing marginal gains compared to classical baselines. These divergent outcomes underscore a fundamental gap in current understanding: the performance of hybrid networks appears to depend not only on the design of the quantum layer itself but also on its integration with specific classical backbones and the scale of the underlying architecture.

In the classical domain, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have long been the dominant paradigm for image recognition [16,17], yet CNN families differ substantially in structure, depth, and computational efficiency. High-capacity networks such as ResNet or DenseNet [18,19] achieve strong predictive accuracy but require extensive computational resources, which complicates their adaptation to hybrid frameworks under NISQ [20] limitations. In contrast, lightweight CNNs, including MobileNet and LCNet, offer compactness, efficiency, and modularity—characteristics that align naturally with the constraints of near-term quantum hardware. Their reduced parameter count and streamlined architecture make them ideal candidates for systematic hybridization and comparative analysis.

Beyond general-purpose image classification, QML has shown growing relevance in the medical imaging domain, where robustness and interpretability are of particular importance. Recent studies suggest that hybrid models may enhance diagnostic classification by exploiting quantum-induced stochasticity and representational diversity [21]. However, most existing works remain at the proof-of-concept stage, typically limited to small datasets and isolated architectures. Only a few studies examine how different CNN backbones interact with quantum layers or how hybrid performance scales with model complexity. Moreover, prior research rarely addresses key evaluation aspects such as per-class discrimination, cross-validation stability, or out-of-fold generalization—factors that are critical for assessing the reliability and clinical applicability of hybrid models.

The current state of the literature therefore reveals a clear gap: there is no comprehensive, systematic analysis of how lightweight CNN backbones behave when partially replaced by quantum layers across varying architectural scales and data domains. While early studies have shown promising results on simple datasets, it remains uncertain whether such improvements extend to more complex and imbalanced datasets, particularly in medical contexts such as dermatological image classification.

The present research aims to address this gap by conducting a structured and comparative evaluation of hybrid quantum–classical LCNet architectures size against their classical counterparts. The analysis is performed on two datasets of contrasting nature: CIFAR-10, a balanced and widely used benchmark for general-purpose image recognition, and DermaMNIST, a medical dataset characterized by class imbalance and diagnostic heterogeneity. By embedding -based parameterized quantum circuits into LCNet backbones of varying scales, the study systematically investigates how quantum layers affect accuracy, loss, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC), while also examining per-class behavior, cross-validation consistency, and out-of-fold generalization.

The overarching objective of this research is to determine under what conditions quantum integration contributes to measurable improvements in performance and stability. More specifically, it seeks to identify the architectural scales and data domains in which hybridization yields tangible benefits, and to evaluate whether the observed advantages on general-purpose datasets translate to the more demanding and clinically relevant domain of medical imaging. Through this analysis, the study aims to provide a rigorous foundation for understanding the role of quantum layers in enhancing lightweight neural networks and to clarify the practical value of hybrid models in real-world applications.

Previous work comparing MobileNetV3 and LCNet [22,23] in hybrid quantum–classical models has indicated that LCNet backbones integrate more smoothly with quantum layers, while MobileNetV3 exhibits scale-dependent instability. Yet, these studies were limited in scope and provide no systematic analysis across backbone sizes or datasets, leaving the architectural determinants of successful hybridization largely unexplored.

3. The Aim and Objectives of the Study

The aim of this study is to investigate the suitability of lightweight convolutional neural network backbones for hybrid quantum–classical architectures, with a focus on LCNet. While parameterized Ry-based quantum layers have demonstrated promise, little is known about how their integration interacts with different classical designs and whether such benefits extend beyond generic benchmarks. To address this, we embed quantum layers into multiple scales of LCNet and evaluate both classical and hybrid variants on two datasets: CIFAR-10, representing a standard benchmark in computer vision, and DermaMNIST, a medical dataset of dermatological images. By combining these evaluations, the study seeks to provide a systematic comparison of hybrid and classical networks using accuracy, validation loss, area under the ROC curve (AUC), and per-class analysis, while also assessing stability through cross-validation and out-of-fold predictions. In doing so, we aim to identify not only the conditions under which hybrid models outperform classical baselines, but also whether performance improvements observed on CIFAR-10 can be generalized to medical imaging tasks where diagnostic reliability is of critical importance.

4. Methodology

To evaluate the influence of backbone architecture on the performance of hybrid quantum–classical neural networks (HNNs), we developed multiple model configurations combining parameterized quantum circuits with lightweight convolutional neural networks. The models differ in their classical backbones, drawn from the LCNet (050, 075, 100, 150, 200) families, enabling a systematic comparison across architectures and scales. This section outlines the evaluation metrics, dataset, quantum layer design, integration strategy, backbone architectures, and the experimental workflow adopted in the study.

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

The assessment of hybrid and classical models relied on several complementary measures to capture different aspects of performance. The primary metrics were validation accuracy and validation area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), computed using both macro- and micro-averaging to account for class balance and overall discrimination power. Validation loss was tracked to assess learning stability and potential overfitting. In addition, per-class accuracy was computed to identify whether certain categories benefited more strongly from quantum layers. For classical models, we also considered backbone complexity, expressed in terms of parameter count and computational cost. For quantum components, execution time was not included since all experiments were performed on simulated hardware; instead, we recorded the number of quantum circuit evaluations required for training and inference. Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive view of both predictive accuracy and model efficiency. The same evaluation protocol was consistently applied to both CIFAR-10 and DermaMNIST to enable direct comparison of results across generic and medical imaging domains.

4.2. Quantum Circuits

All hybrid models employed a four-qubit parameterized quantum circuit based on Ry rotations. Each qubit was initialized with a Hadamard gate to establish superposition, followed by a trainable Ry gate that introduced one parameter per qubit [24]. Measurement was performed in the computational basis, and the expectation values of each qubit formed a four-dimensional vector passed to the classical network. This design was motivated by prior studies indicating that Ry-based circuits achieve a good balance between expressiveness and training stability in hybrid architectures. The dimensionality of the circuit was deliberately chosen to match the embeddings produced by the classical backbones, allowing for seamless integration without architectural mismatches. Importantly, inputs to the circuit were normalized and -scaled to ensure compatibility with the rotation parameters of the quantum gates.

4.3. Datasets

The CIFAR-10 dataset (Figure 1) served as the benchmark for evaluating the hybrid architectures in a general-purpose vision task [25]. It contains 60,000 color images of size 32 × 32 pixels, evenly distributed across ten object classes: airplane, automobile, bird, cat, deer, dog, frog, horse, ship, and truck. Of these, 50,000 images were used for training and 10,000 for testing. During cross-validation, a portion of the training data was reserved for validation to monitor learning progress and prevent overfitting. All images were normalized per channel to zero mean and unit variance, ensuring consistent scaling across models. Standard data augmentation techniques—random horizontal flipping and random cropping—were applied to increase robustness and improve generalization. The choice of CIFAR-10 was motivated by its balanced class distribution, moderate complexity, and widespread use in both classical and hybrid quantum–classical learning research, which allows for fair comparison with previous studies.

Figure 1.

Examples of images from the CIFAR-10 dataset used to train and evaluate models.

The DermaMNIST dataset (Figure 2), derived from the MedMNIST collection, was included to assess the applicability of hybrid architectures in the medical imaging domain [23]. It consists of 10,015 dermatoscopic images categorized into seven diagnostic classes representing various benign and malignant skin conditions. Each image was resized to 28 × 28 pixels and normalized to unit variance, with stratified sampling applied to preserve class proportions across folds. Unlike CIFAR-10, DermaMNIST is inherently imbalanced, with significant disparities in class frequency that mirror real-world diagnostic challenges in dermatology. This imbalance makes metrics such as the area under the ROC curve (AUC) particularly important for a reliable evaluation of model performance across classes. In this study, DermaMNIST provides a meaningful testbed for exploring how quantum-enhanced hybrid models handle complex, data-limited, and clinically relevant tasks. Its inclusion not only broadens the scope of evaluation beyond standard benchmarks but also emphasizes the potential of quantum–classical hybridization to improve diagnostic reliability, stability, and efficiency in medical contexts where even small gains in classification accuracy can have high clinical value.

Figure 2.

Examples of dermatoscopic images from the DermaMNIST dataset used to assess model performance on imbalanced medical data.

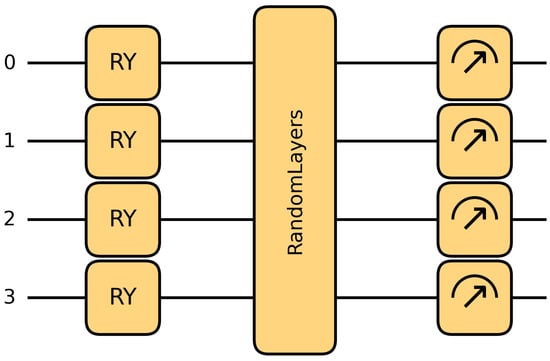

4.4. Quantum Layer

The integration of the quantum layer into classical backbones followed a consistent and modular pipeline. The classical network produced a four-dimensional embedding that matched the number of qubits in the quantum circuit, ensuring dimensional compatibility and eliminating the need for additional encoding or compression schemes. Before being passed to the circuit, the embedding was normalized and scaled by , as the Ry gates interpret input values as rotation angles within the range . After quantum evolution, the circuit generated four expectation values, which were concatenated into a feature vector. This vector was then processed by a fully connected layer projecting to ten class logits, followed by a softmax activation to obtain class probabilities. This consistent design ensured that the differences between classical and hybrid variants could be attributed solely to the presence of the quantum layer, rather than architectural mismatches.

In addition to this architectural integration, the quantum layer incorporated quantum data transformations that simulate the behavior of quanvolutional filters [26]. The underlying idea was that the randomness and noise introduced by quantum operations could serve as a non-classical data augmentation technique, enriching the model’s representational diversity. This approach is particularly relevant for near-term noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, where limited qubit counts and decoherence can be exploited constructively rather than treated as limitations. In this study, we employed combinations of Y-axis and X-axis qubit rotation gates, implemented in the Pennylane framework. Each input feature was multiplied by and used as a rotation angle for the corresponding qubit, effectively embedding the normalized data into the quantum state space. The Ry and Rx gates performed rotations of single qubits around the Y and X axes of the Bloch sphere, respectively, creating transformations that are both nonlinear and inherently stochastic.

Specifically, Y-axis quanvolutional transformations with stride 1 were applied to generate multi-channel quantum-transformed representations for both CIFAR-10 and DermaMNIST. The operation, defined as

rotates each qubit around the Y-axis of the Bloch sphere by angle , enabling the encoding of pixel intensities into quantum states. For every group of pixels, independent quantum circuits were executed to produce quantum-transformed feature maps that enrich the classical embedding with additional representational capacity (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Examples of Y-axis quanvolutional transformations implemented with Pennylane for 4-qubit circuits applied to 4-pixel patches.

In all experiments, these circuits were evaluated in a simulated environment rather than on physical quantum hardware, so the reported effects should be interpreted as arising from quantum-inspired transformations implemented by Pennylane simulation software. The resulting quantum-enhanced features were then integrated back into the hybrid architecture, allowing the network to leverage both classical spatial hierarchies and non-classical transformations derived from quantum operations. This hybrid integration strategy—combining learned embeddings with stochastic quantum rotations—enables the architecture to capture a broader range of correlations within the data while maintaining efficient compatibility with existing deep learning frameworks and remaining, in principle, extendable to future NISQ quantum processors.

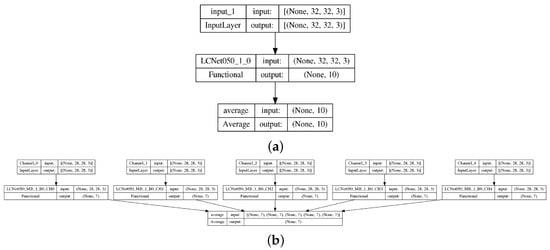

4.5. Classical Backbone

The choice of backbone architecture is a central focus of this study. We selected two families of lightweight convolutional neural networks: LCNet [27]. Both are designed for efficiency and are widely used in mobile and resource-constrained environments, making them natural candidates for quantum integration. LCNet represents a more recent architecture optimized for compactness. It employs linear convolutions, lightweight channel interactions, and efficient bottleneck structures. LCNet is explicitly designed to reduce redundancy while maintaining feature expressivity. Importantly, its simpler and more structured design makes it especially attractive for integration with quantum layers, as it minimizes the risk of parameter explosion or incompatibility with small quantum circuits. For both backbones, the last classical layer before the quantum circuit was implemented with a tanh activation to constrain outputs to (–1, 1), ensuring they aligned with the expected ranges of quantum gates. This detail was critical, as unconstrained values could destabilize quantum training. In LCNet intermediate layers employed ReLU activations (Figure 4). The classification stage, shared across all models, consisted of a fully connected layer projecting quantum outputs into 10 logits, followed by softmax. By comparing multiple scales of LCNet, we aimed to isolate how backbone complexity, parameter count, and architectural design influence the success of hybrid quantum integration.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the classical LCNet-based CNN with only original image channels (a) and the hybrid neural network with additional quanvolutional channels (b).

4.6. Workflow

The rigorous workflow was implemented to ensure fair and robust comparison between classical and hybrid models. Training and validation were conducted using stratified 5-fold cross-validation (CV). After five folds, OoF predictions were aggregated and used to compute final performance metrics, including overall accuracy, macro- and micro-averaged AUC, and per-class accuracy. Confusion matrices were also constructed to assess class-specific performance. This workflow was applied consistently to both CIFAR-10 and DermaMNIST, ensuring methodological comparability between experiments on general-purpose and medical datasets. This strategy provided several advantages. First, it mitigated overfitting by ensuring that evaluation was always performed on unseen data. Second, stratification preserved class balance across folds, which is essential for multiclass tasks such as CIFAR-10. Third, it enabled aggregation of predictions across all folds into a complete set of out-of-fold (OoF) predictions, which served as the basis for computing unbiased performance metrics. During training, models were optimized using stochastic gradient descent with appropriate learning rate scheduling. At the end of each epoch, validation accuracy, AUC, and loss were recorded. After five folds, OoF predictions were aggregated and used to compute final performance metrics, including overall accuracy, macro- and micro-averaged AUC, and per-class accuracy. Confusion matrices were also constructed to assess class-specific performance. To ensure reproducibility, the following configuration was applied consistently across all folds. The experiments used quantum-augmented inputs consisting of the original RGB channels and four additional quantum-generated channels (QC5 configuration, total channels). Each experiment was trained using 6-fold cross-validation, with a batch size of 64, and optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of . Training was conducted for 10 epochs without early stopping or other adaptive termination criteria. All random seeds were fixed to 42 for NumPy 2.0.2, TensorFlow 2.15.1, and Python 3.10 to ensure deterministic behavior. The implementation used TensorFlow in a single-replica Kaggle environment without TPU acceleration. Due to the preprocessing overhead introduced by the generation of quantum-enhanced channels, a direct wall-clock time comparison with purely classical baselines was not performed. This preprocessing step introduces additional latency that is independent of model optimization, and thus not representative of training efficiency differences between classical and hybrid architectures.

This workflow (Figure 5) ensured that all results reported in the study were derived from strictly unseen data and were free from information leakage or overly optimistic validation scores. Moreover, it allowed us to quantify model stability across folds by computing standard deviations of the metrics. In practice, this provided deeper insight into the robustness of hybrid models compared to their classical counterparts.

Figure 5.

Overview of the training and evaluation workflow with stratified K-fold cross-validation, out-of-fold (OoF) predictions, and metric computation for classical and hybrid LCNet models.

5. Results

The experiments were designed to assess how the choice of classical backbone influences the performance of hybrid quantum–classical neural networks (HNNs). We report results for two datasets: CIFAR-10, representing a standard vision benchmark, and DermaMNIST, representing a medical imaging dataset with imbalanced diagnostic classes. All results are averaged across stratified 5-fold cross-validation, and both mean accuracy and standard deviation are presented to capture stability across folds.

5.1. CIFAR-10 Results

To evaluate the effect of hybridization on general-purpose image classification, we compared hybrid LCNet backbones with their classical counterparts on the CIFAR-10 dataset. Results were obtained using stratified 5-fold cross-validation, and both mean values and standard deviations are reported. Out-of-fold (OoF) predictions were aggregated to ensure unbiased estimates.

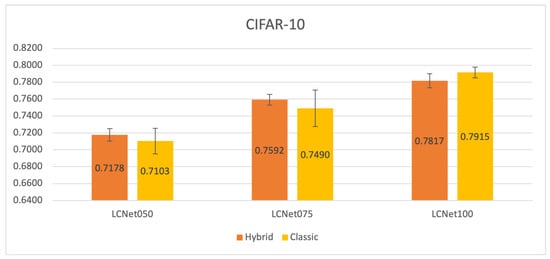

The accuracy results in Figure 6 show that hybrid models consistently outperformed their classical counterparts on smaller and mid-sized backbones. For LCNet050 and LCNet075, the hybrid variants achieved higher mean accuracy while also displaying considerably lower variance across folds. The effect was most pronounced for LCNet075, where hybridization yielded an improvement of about one percentage point in mean accuracy and reduced variability by almost a factor of three, underscoring the stabilizing influence of the quantum layer at this scale. In contrast, for LCNet100 the trend reversed, with the classical model slightly surpassing the hybrid both in accuracy and in stability, suggesting that the relative benefit of quantum integration decreases as the backbone capacity grows.

Figure 6.

Mean out-of-fold accuracy on CIFAR-10 for classical and hybrid LCNet backbones at different scales.

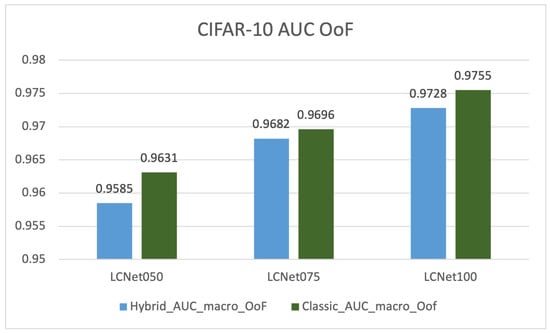

Across all three backbone sizes, the classical networks maintained a small but consistent advantage in both macro- and micro-AUC means which we can see in Table 1. Nevertheless, the hybrid variant of LCNet075 displayed markedly lower variance in micro-AUC, with a standard deviation of 0.0017 compared to 0.0060 for the classical model, indicating more consistent performance across folds even when mean values were nearly identical. This outcome points to a potential regularizing role of the quantum layer, which appears to stabilize learning dynamics most effectively at intermediate model scales. The comparison of hybrid and classical LCNet architectures on CIFAR-10 revealed several noteworthy patterns. In terms of accuracy, the hybrid networks demonstrated clear advantages for smaller and mid-sized backbones. LCNet050 and LCNet075 both achieved higher mean accuracy than their classical counterparts, with improvements of approximately 0.7 and 1.0 percentage points, respectively. These gains were accompanied by a noticeable reduction in variance across folds, indicating that the quantum-enhanced models produced more stable outcomes during cross-validation. At the larger scale, however, this trend did not persist. The classical LCNet100 achieved superior accuracy, outperforming the hybrid model by nearly one percentage point and exhibiting slightly greater stability, suggesting that the benefits of quantum integration diminish as the backbone size increases (Figure 7).

Table 1.

Macro- and micro-averaged AUC on the CIFAR-10 dataset for classical and hybrid LCNet backbones. The Δ columns show differences between hybrid and classical variants.

Figure 7.

Macro-averaged out-of-fold AUC on CIFAR-10 for classical and hybrid LCNet backbones at different scales.

When considering the area under the ROC curve, classical models maintained a modest but consistent advantage across all backbone sizes. Both macro- and micro-AUC means were slightly higher for classical networks, with differences generally below 0.6 percentage points. Despite this, the hybrid models—particularly LCNet075—displayed lower variance in micro-AUC, highlighting improved reliability across folds even when mean performance remained similar. This suggests that the main contribution of hybridization lies not in elevating AUC scores beyond classical baselines but in reducing variability in model behavior. Taken together, these findings indicate that hybrid LCNet architectures provide measurable benefits in terms of stability and robustness at smaller to intermediate capacities, where the regularization effect of the quantum layer appears most effective. At larger scales, however, the representational capacity of classical models becomes dominant, leading to higher accuracy and AUC. Thus, while hybrids do not consistently surpass classical networks in raw performance on CIFAR-10, they offer distinct advantages in stabilizing learning dynamics and ensuring more reliable outcomes, especially when model size is constrained.

5.2. DermaMNIST Results

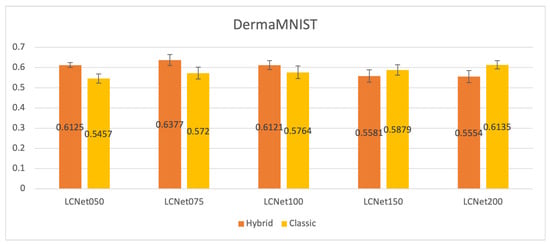

The accuracy results on DermaMNIST (Figure 8) reveal a strong advantage of hybrid models at smaller backbone sizes. LCNet050 achieved an average accuracy of 0.6125 compared to only 0.5457 for the classical variant, while LCNet075 reached 0.6377 versus 0.5720 for its counterpart. These differences, amounting to gains of approximately six to seven percentage points, were also accompanied by slightly lower variance, suggesting that hybridization not only improved predictive performance but also produced more reliable fold-to-fold outcomes. For LCNet100, the hybrid model continued to outperform the classical version, reaching 0.6121 against 0.5764, although the variance remained relatively high in both cases. By contrast, larger backbones shifted the balance in favor of classical architectures. LCNet150 and LCNet200 achieved higher accuracies in their classical configurations, with margins of nearly three and six percentage points, respectively. These results indicate that the benefits of quantum integration are most pronounced in smaller and medium backbones, whereas classical networks retain an advantage once the capacity of the model becomes sufficiently large.

Figure 8.

Mean out-of-fold accuracy on DermaMNIST for classical and hybrid LCNet backbones at different scales.

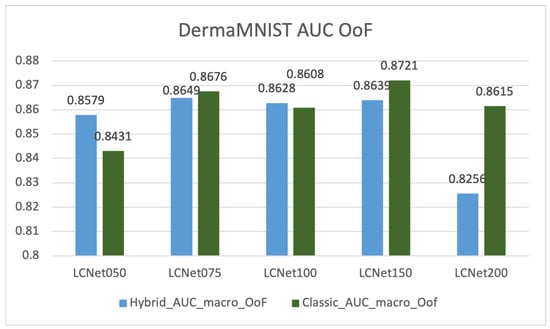

The AUC results in Table 2 provide additional insight into the effect of hybridization on DermaMNIST. For the smaller backbones, the hybrid models consistently outperformed the classical ones across both macro- and micro-AUC. LCNet050 improved macro-AUC from 0.8310 to 0.8647 and micro-AUC from 0.8919 to 0.9080, while also slightly reducing fold-to-fold variance (Figure 9). LCNet075 demonstrated a similar trend, with macro-AUC increasing from 0.8391 to 0.8778 and micro-AUC from 0.9028 to 0.9207. In both cases, the hybrid variants provided more robust discrimination between diagnostic categories, with improvements ranging from 1.5 to almost 4 percentage points. LCNet100 continued this pattern with a more modest advantage, gaining roughly two percentage points in macro-AUC and less than one point in micro-AUC. However, the benefit diminished for larger models. LCNet150 and LCNet200 performed better in their classical versions, which achieved higher macro- and micro-AUC values and displayed lower variance. These results suggest that hybrid architectures improve discrimination at small to medium scales, particularly in handling imbalanced medical classes, but lose this advantage as the backbone grows more complex.

Table 2.

Macro- and micro-averaged AUC on the DermaMNIST dataset for classical and hybrid LCNet backbones. The Δ columns show differences between hybrid and classical variants.

Figure 9.

Macro-averaged out-of-fold AUC on DermaMNIST for classical and hybrid LCNet backbones at different scales.

Taken together, the DermaMNIST experiments show that hybrid LCNet models are highly effective at compact and intermediate scales, where they substantially improve both accuracy and AUC while reducing variability in several cases. At larger scales, however, the advantage shifts back toward classical networks, which deliver higher predictive performance and greater stability. This pattern suggests that the regularization effect of quantum layers is most beneficial in constrained, imbalanced medical settings, but does not scale effectively to deeper architectures.

6. Discussion

6.1. CIFAR-10

On CIFAR-10, the results indicate that hybrid models provide the clearest benefits at smaller and medium backbone scales, whereas their advantage diminishes as the architecture grows larger. As shown in Table 3, hybrid LCNet050 and LCNet075 models achieved higher mean accuracies ( and ) than their classical counterparts ( and ), while also exhibiting notably lower standard deviations across folds ( and versus and ). This reduction in variance—nearly threefold for LCNet075—demonstrates that hybridization enhances training stability and generalization consistency.

Table 3.

Out-of-fold accuracy on the CIFAR-10 dataset for classical and hybrid LCNet backbones. The columns show differences between hybrid and classical variants.

In Table 1, a similar pattern emerges: although classical models retained a marginal edge in mean AUC values, the hybrid LCNet075 achieved substantially lower micro-AUC variability ( vs. ), indicating more uniform performance across folds. Such behavior suggests that quantum layers act as a regularizing mechanism, introducing a controlled form of stochasticity that improves robustness without requiring additional parameters.

The most consistent improvements were therefore observed at smaller and medium backbone scales, where hybrid models not only achieved higher accuracy but also reduced variability across folds—pointing to a synergistic interaction between limited classical capacity and quantum feature transformation. However, once the backbone reached LCNet100, this benefit plateaued: classical models slightly surpassed hybrids in both mean accuracy and AUC, implying that larger networks possess sufficient representational capacity to achieve stable convergence without quantum augmentation. Consequently, the CIFAR-10 experiments reveal that hybridization is most advantageous under constrained model capacity, serving as an implicit regularizer in smaller architectures, whereas classical backbones regain dominance as depth and complexity increase.

6.2. DermaMNIST

The DermaMNIST results further reinforce this scale-dependent behavior while extending its implications to medical data. As shown in Table 4, hybrid LCNet050 and LCNet075 achieved mean accuracies of and , respectively, outperforming the classical baselines ( and ) by approximately six to seven percentage points. Importantly, these gains were accompanied by comparable or reduced standard deviations ( and versus and ), confirming that hybridization improves both predictive power and reliability.

Table 4.

Out-of-fold accuracy on the DermaMNIST dataset for classical and hybrid LCNet backbones. The columns show differences between hybrid and classical variants.

When considering AUC metrics (Table 2), the hybrid models again displayed superior macro- and micro-AUCs at smaller scales, with LCNet075 achieving macro-AUC and micro-AUC, compared to and for the classical counterpart. The improvement in hybrid performance was accompanied by lower or similar standard deviations, emphasizing that quantum integration contributes not merely to higher averages but also to more stable outcomes across folds. Even at LCNet100, hybrids maintained a modest advantage in mean values despite slightly increased variability.

However, for the largest backbones (LCNet150 and LCNet200), the classical architectures regained superiority, showing both higher mean AUCs and smaller variances. This reversal suggests that as the classical network’s representational power increases, the incremental benefits of the quantum layer diminish. At that scale, the added stochasticity may even hinder convergence, producing less stable learning dynamics. Thus, the DermaMNIST experiments corroborate the CIFAR-10 findings: hybrid quantum–classical integration yields measurable benefits primarily in compact architectures, where it compensates for limited expressive capacity and enhances training consistency.

6.3. General Insights and Implications for Medical Data

Collectively, these findings reveal that the primary strength of hybrid quantum–classical models lies not in outperforming classical networks across all configurations, but in enabling smaller architectures to achieve comparable or superior generalization with reduced variability. The combination of higher mean accuracy and lower standard deviation in smaller LCNet hybrids highlights the potential of quantum layers as implicit regularizers, particularly valuable when data or computational resources are limited.

This effect is especially relevant for medical imaging, where class imbalance and small sample sizes often amplify overfitting risks. On DermaMNIST, hybrid models not only improved average accuracy and AUC but also provided more consistent results across folds—an essential property in clinical contexts where stability and reliability are critical. These observations suggest that quantum transformations can act as a controlled source of noise that promotes smoother optimization landscapes, reducing sensitivity to initialization and sample variation.

While classical models continue to outperform hybrids at larger scales, the demonstrated efficiency of smaller hybrid architectures offers an appealing pathway for resource-constrained or edge medical applications. By achieving competitive results with fewer parameters and enhanced consistency, hybrid LCNet variants represent a promising direction for practical quantum-assisted medical image analysis under NISQ-era constraints.

From a physical perspective, the present study does not disentangle whether the observed improvements in stability arise primarily from quantum effects such as superposition and entanglement or from the stochastic behavior of the simulated circuits. All quantum layers in our experiments are implemented using Pennylane simulation software on classical hardware, and no explicit modeling of device-level noise is performed. As a result, the reported gains should be interpreted as simulator-based evidence for the usefulness of quantum-inspired transformations in hybrid architectures. Confirming whether the same stability patterns persist on real NISQ hardware, where decoherence and gate errors are inherently present, remains an important direction for future work.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While our study provides evidence for the critical role of classical backbone architecture in HNN performance, several limitations present valuable avenues for future research, particularly in the context of medical applications.

A primary limitation is the phenomenological nature of our findings: we have documented that backbones like LCNet respond differently to hybridization, but a deeper, mechanistic explanation for why should be researched thoroughly. Future work should move beyond performance metrics to analyze the internal representations and training dynamics of these hybrid models. Investigating factors such as gradient flow, the effect of specific classical modules (e.g., in MobileNetV3), and the interaction between classical feature maps and the quantum latent space could yield a principled theory of architectural compatibility, which is essential for rational HNN design.

The use of a simple, -based circuit raises a fundamental question: are the observed benefits uniquely quantum, or do they stem from introducing a well-initialized, non-linear stochastic layer? To isolate the source of improvement, future investigations must include ablation studies with classical probabilistic layers of comparable parameter count. Furthermore, exploring more complex quantum schemes is crucial to determine if more expressive quantum transformations can provide gains that are definitively beyond classical approximation, especially for capturing complex, hierarchical features in medical data. More rigorous statistical analyses—including confidence interval estimation and paired significance testing—represent an important direction for future work and will be incorporated in subsequent studies to strengthen the reliability of performance comparisons.

Our findings on DermaMNIST are promising but preliminary. The term “medical applications” encompasses a vast diversity of imaging modalities (from dermatology and radiology to histopathology and ophthalmology that is partially represented by other subsets in MedMNIST dataset) each with unique challenges. A significant and necessary next step is to validate these architectural guidelines across the broader MedMNIST set of subdatasets including the following aspects.

- Modality Variation: Testing on sub-datasets like PathMNIST (histology), OrganMNIST (CT scans), and PneumoniaMNIST (X-rays) to assess performance across 2D and 3D structures, color vs. grayscale, and different disease paradigms.

- Scale and Resolution: Progressing from the low-resolution (28 × 28, 32 × 32) benchmarks in MedMNIST to its larger variants and eventually to full-scale, high-resolution clinical datasets. This will critically test the scalability of the observed effect for hybridization and its practicality for real-world diagnostic tasks where image detail is paramount.

- Data Imbalance and Generalization: Intentionally studying HNN performance on the more challenging, imbalanced MedMNIST subsets to rigorously evaluate their claimed robustness and generalization, a property of high clinical value.

Addressing these aspects will be critically important in transitioning hybrid quantum–classical neural networks from a promising concept on standardized benchmarks to a reliable tool for computer-aided diagnosis in real-world clinical environments.

7. Conclusions

This study systematically evaluated the influence of lightweight convolutional backbones on the performance of hybrid quantum–classical neural networks for medical applications in MedMNIST dataset. By embedding parameterized quantum layers into LCNet models and testing them on both the general-purpose CIFAR-10 dataset and the medical DermaMNIST dataset, we demonstrated that hybridization can provide measurable benefits under specific conditions. The most consistent improvements were observed at smaller and medium backbone scales, where hybrid LCNet models not only achieved higher mean accuracy but also exhibited markedly lower standard deviations across folds. This dual enhancement—improved central performance and reduced variability—demonstrates that quantum layers contribute to both accuracy and reliability. On DermaMNIST in particular, hybrids delivered substantial gains in both accuracy and AUC, highlighting their potential for handling imbalanced and clinically relevant data. At the same time, the experiments revealed that these benefits do not scale uniformly. For larger backbones, classical models regained their advantage, achieving higher accuracy and more stable AUC values. This indicates that while quantum layers act as an effective regularizer in resource-constrained settings, their contribution diminishes as the expressive power of the classical architecture increases. Overall, the results suggest that hybrid quantum–classical models hold promise as efficient alternatives to purely classical designs, particularly when training data is limited or when model size must remain compact. Their ability to enhance stability and performance in smaller networks points toward practical use cases in medical imaging, where lightweight but reliable models are often required. Future research should explore scalability across broader datasets and investigate hardware implementations that may further unlock the potential of hybrid quantum–classical learning for medical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and Y.G.; funding acquisition, S.S. and Y.G.; investigation, A.K., Y.G. and S.S. (in general); methodology, A.K. and Y.G.; project administration, Y.G. and S.S.; resources, S.S.; software, A.K. and Y.G.; supervision, S.S.; validation, A.K. and Y.G.; visualization, A.K. and Y.G.; writing—original draft, A.K. and Y.G.; writing—review and editing, A.K., Y.G. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the US National Academy of Sciences (US NAS) and the Office of Naval Research Global (ONRG) (IMPRESS-U initiative, No. STCU-7125) as part of exploratory research on new robust machine learning approaches for object detection and classification and by the National Research Foundation of Ukraine (NRFU), grant 2025.06/0100, as part of the research and development of novel neural networks architectures for multiclass classification and object detection.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets of quantum pre-processed CIFAR-10 and DermaMNIST (MedMNIST) are openly available online on the Kaggle platform [28]. The source code of all experiments conducted in this research is also publicly available on the Kaggle platform in the form of Jupyter Notebooks [29,30,31].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| CIFAR | Canadian Institute For Advanced Research |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| HNN | Hybrid Quantum–Classical Neural Network |

| LCNet | Lightweight Convolutional Network |

| MedMNIST | Medical MNIST |

| NISQ | Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum |

| OoF | Out-of-Fold |

| PQC | Parameterized Quantum Circuit |

| QML | Quantum Machine Learning |

References

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steane, A. Quantum computing. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1998, 61, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, D.; Date, P. Hybrid quantum-classical neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE), Broomfield, CO, USA, 18–23 September 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.Y.; Broughton, M.; Mohseni, M.; Babbush, R.; Boixo, S.; Neven, H.; McClean, J.R. Power of data in quantum machine learning. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biamonte, J.; Wittek, P.; Pancotti, N.; Rebentrost, P.; Wiebe, N.; Lloyd, S. Quantum machine learning. Nature 2017, 549, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Lu, Y.; Li, J.; Sigov, A.; Ratkin, L.; Ivanov, L.A. Quantum machine learning: Classifications, challenges, and solutions. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 42, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiVincenzo, D.P. Quantum computation. Science 1995, 270, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrazola, J.M.; Jahangiri, S.; Delgado, A.; Ceroni, J.; Izaac, J.; Száva, A.; Azad, U.; Lang, R.A.; Niu, Z.; Di Matteo, O.; et al. Differentiable quantum computational chemistry with PennyLane. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.09967. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Lim, K.H.; Wood, K.L.; Huang, W.; Guo, C.; Huang, H.L. Hybrid quantum-classical convolutional neural networks. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2021, 64, 290311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Huang, M.; Ye, X.; Futamura, Y.; Sakurai, T. Hybrid quantum-classical-quantum convolutional neural networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J. Towards an architecture description language for hybrid quantum-classical systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Software (QSW), Shenzhen, China, 7–13 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, K.; Ahmed, T.; Hanif, M.A.; Marchisio, A.; Shafique, M. A comparative analysis of hybrid-quantum classical neural networks. In Proceedings of the World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering & Applied Computing, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 22–25 July 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 102–115. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti, M.; Lloyd, E.; Sack, S.; Fiorentini, M. Parameterized quantum circuits as machine learning models. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, H.M.; Banka, A.A. Quantum-Classical Hybrid Architectures and How They Are Solving Scientific Problems—A Short Review. SSRN Electron. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchara, M.; Alexeev, Y.; Chong, F.; Finkel, H.; Hoffmann, H.; Larson, J.; Osborn, J.; Smith, G. Hybrid quantum-classical computing architectures. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Post-Moore Era Supercomputing, Dallas, TX, USA, 11 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kattenborn, T.; Leitloff, J.; Schiefer, F.; Hinz, S. Review on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) in vegetation remote sensing. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 173, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.; Ghanshala, K.K.; Joshi, R.C. Convolutional neural network (CNN) for image detection and recognition. In Proceedings of the 2018 First International Conference on Secure Cyber Computing and Communication (ICSCCC), Jalandhar, India, 15–17 December 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Koonce, B. ResNet 50. In Convolutional Neural Networks with Swift for Tensorflow: Image Recognition and Dataset Categorization; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Iandola, F.; Moskewicz, M.; Karayev, S.; Girshick, R.; Darrell, T.; Keutzer, K. Densenet: Implementing efficient convnet descriptor pyramids. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1404.1869. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, J.W.Z.; Lim, K.H.; Shrotriya, H.; Kwek, L.C. NISQ computing: Where are we and where do we go? AAPPS Bull. 2022, 32, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahjalal; Fahim, J.K.; Paul, P.C.; Hossain, M.R.; Ahmed, M.T.; Chakraborty, D. HQCNN: A Hybrid Quantum-Classical Neural Network for Medical Image Classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.14277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmelnytskyi, A.; Gordienko, Y. Comparative Study of MobileNetV3 and LCNet-Based Hybrid Quantum-Classical Neural Networks for Image Classification. Inf. Comput. Intell. Syst. J. 2025; accepted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Shi, R.; Ni, B. Medmnist classification decathlon: A lightweight automl benchmark for medical image analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Nice, France, 13–16 April 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bergholm, V.; Izaac, J.; Schuld, M.; Gogolin, C.; Ahmed, S.; Ajith, V.; Alam, M.S.; Alonso-Linaje, G.; AkashNarayanan, B.; Asadi, A.; et al. Pennylane: Automatic differentiation of hybrid quantum-classical computations. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.04968. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, G. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images. 2009. Available online: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/learning-features-2009-TR.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Henderson, M.; Shakya, S.; Pradhan, S.; Cook, T. Quanvolutional Neural Networks: Powering Image Recognition with Quantum Circuits. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.04767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, L. LCNet: A light-weight network for object counting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–12 December 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 411–422. [Google Scholar]

- Gordienko, Y.; Trochun, Y.; Khmelnytskyi, A. Quantum-Preprocessed CIFAR-10 and MedMnist Datasets. 2024. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/yoctoman/qnn-cifar10-medmnist (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Khmelnytskyi, A.; Gordienko, Y. Example of Baseline Model Based on LCNet Used for Experiments. 2025. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/code/arseniykhmelnitskiy/cifar10-classic-q5-w4-lcnet050-mb1-batch-64-t (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Khmelnytskyi, A.; Gordienko, Y. Example of Implementation of HNN-QC5: Quantum Transformation as Data Augmentation Technique in Hybrid Neural Network Setup with Multiple Backbones and Quantum and Original Channel Inputs for Multiclass Image Classification. 2025. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/code/arseniykhmelnitskiy/cifar10-full-q5-w4-lcnet050-mb1-batch-64-trial11 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Khmelnytskyi, A.; Gordienko, Y. Example of Implementation of HNN-QC5: Quantum Transformation as Data Augmentation Technique in Hybrid Neural Network Setup with Multiple Backbones and Quantum and Original Channel Inputs for Multiclass Image Classification for Medical Application. 2025. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/code/arseniykhmelnitskiy/dermamnist-full-q5-w4-lcnet050-mb1-batch-64-t (accessed on 30 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).