1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (2024), worldwide, approximately 466 million individuals with hearing impairments and 36 million people with visual impairments face significant challenges in communication. These barriers are primarily manifested in conflicts between sensory channels, real-time bottlenecks, and the loss of emotional conveyance [

1,

2]. There are significant communication barriers between deaf–mute and visually impaired populations in daily interactions. How artificial intelligence technology can provide real-time end-to-end feasibility [

3] has become a key focus in the research on accessible information technology. Deep learning-based sign language recognition has achieved breakthrough advancements in accuracy and robustness [

4,

5]. However, single-gesture information exhibits inherent ambiguity in certain contexts, limiting its ability to meet complex communication demands. Meanwhile, micro-expression recognition can complement gesture understanding by providing affective and semantic cues; however, interactive scenarios involving deaf–mute and visually impaired individuals have rarely been studied. Therefore, integrating gesture and micro-expression recognition through multimodal fusion while enabling speech output emerges as a pivotal approach to enhance communication efficiency and naturalness.

In the field of gesture recognition, current research has evolved from traditional static gesture classification to complex dynamic continuous sign language understanding [

6]. Early studies primarily focused on static gesture feature extraction using convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which achieved high recognition accuracy [

7,

8,

9]. However, to address the temporal dependencies inherent in continuous sign language, most researchers have gradually incorporated recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [

10,

11], especially long short-term memory (LSTM) networks and gated recurrent units (GRUs), to model cross-frame sequence information. In addition, Transformer architecture, with its powerful global context modeling capability and parallel computation efficiency, has achieved breakthrough progress in the field of sign language recognition. Its core self-attention mechanism effectively balances the importance of all frames within a video sequence, enabling more accurate semantic understanding of long-sequence sign language gestures. Meanwhile, to meet the real-time deployment requirements for assistive tools on mobile and embedded platforms, lightweight model design has emerged as a critical trend. The current research focus has shifted from solely pursuing high accuracy to seeking a balance between precision and efficiency. Lightweight networks such as MobileNet, ShuffleNet, and GhostNet have been integrated into single-stage detectors such as YOLO and SSD [

12] or customized through neural architecture search (NAS) techniques [

13], significantly reducing the model parameters and computational complexity. This advancement lays the foundation for low-power real-time interactive systems [

14,

15].

In the domain of micro-expression recognition, due to the subtle facial action amplitude and transient temporal duration characteristics, the recognition process is prone to inaccuracies [

16]. Early methods heavily relied on high-frame-rate cameras and complex optical flow techniques to capture subtle facial muscle movements. With the introduction of deep learning technologies, especially 3D convolutional neural networks (3D CNNs) [

17], models have been able to simultaneously learn spatial features and short-term temporal characteristics from raw video clips, marking a milestone in this field [

18]. Subsequently, to more accurately model long-term temporal dynamics, researchers proposed hybrid architectures based on CNN-RNN. After CNNs extract spatial features, RNNs are employed to learn the inter-frame temporal variation patterns. Recently, Transformer models and their variants have also begun to be applied to micro-expression recognition, leveraging the self-attention mechanism to compute the correlation between feature pixel blocks in both the spatial and temporal dimensions, showing superior performance [

19]. Similar to gesture recognition, research into micro-expression recognition also faces challenges in transitioning from controlled laboratory settings to unconstrained real-world environments, which has motivated researchers to develop algorithms with enhanced robustness to head movements and illumination variations, as well as to explore lightweight deployment strategies suitable for resource-constrained devices [

20].

Although the aforementioned studies have achieved significant progress within their respective domains, a notable research gap still exists—the deep integration of gesture and micro-expression recognition for facilitating communication between deaf–mute and visually impaired individuals remains at a nascent stage of development [

21]. Most existing systems remain ‘isolated’, either exclusively focusing on the semantic content of gestures or solely analyzing facial emotional states. However, human communication is inherently a multimodal and affect-rich process [

22], where gestures convey core information, while micro-expressions carry crucial emotional nuances and intent. This fragmentation renders existing interaction systems rigid and unnatural, failing to achieve truly “barrier-free” communication. To address this issue, we propose and implement a multimodal system tailored for bidirectional communication between deaf–mute individuals and visually impaired individuals. The system consists of three well-defined stages—the perception stage, the recognition stage, and the speech stage—as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The main contributions of this research are as follows:

- (1)

Lightweight network optimization: we optimize the YOLOv5s backbone network by introducing fusion residual modules and downsampling modules, achieving a better balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency.

- (2)

Multimodal fusion mechanism innovation: we design an attention-based feature-level fusion strategy that dynamically integrates the skeletal semantic information of gestures with the textural and affective features of micro-expressions, thereby enhancing the accuracy and stability of joint recognition.

- (3)

End-to-end system construction and validation: we successfully integrate the improved visual recognition model with the speech synthesis module, building a complete real-time communication system, whose feasibility and efficiency are validated on the integrated project platform.

2. Related Work

2.1. Gesture and Sign Language Recognition

Gesture and sign language recognition is a key technology in human–computer interaction, and its development has reflected the paradigm shift in the field of computer vision. Traditional methods relied on carefully designed handcrafted features. Before the era of deep learning, researchers primarily completed recognition tasks by extracting features that could describe the shape, texture, and motion information of the hands. Among these, scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) and histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) were widely used to capture the static appearance features of the hand. For dynamic gestures or continuous sign language, the dynamic time warping (DTW) algorithm was used to align and compare time-series data at different speeds. However, these handcrafted features often performed unstably in the presence of complex backgrounds, lighting variations, and individual differences. Moreover, the feature design was heavily dependent on expert knowledge, limiting the generalization ability. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), with their spatial feature extraction capability, quickly became the mainstream architecture for static gesture recognition. Researchers have designed various CNN models to automatically learn the mapping from raw pixels to gesture categories, significantly outperforming handcrafted features.

Currently, research into gesture and sign language recognition is evolving in two directions: more accurate fine-grained recognition and more efficient lightweight deployment. Although existing technologies have matured, a key challenge remains to be addressed: in real-world unobstructed scenarios, how can we implement a system on embedded platforms that can accurately understand complex sign language semantics (including subtle finger gestures), while maintaining low power consumption and high frame rates? Against this backdrop, the present study performs a targeted structural optimization of the lightweight YOLOv5 network, aiming to enhance its detection capability for subtle gestures, while ensuring it meets the strict requirements for real-time interaction.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed method, this study selects representative single-stage and two-stage detection architectures as the baseline models. YOLOv5s, one of the most widely adopted lightweight detectors, achieves a favorable balance between accuracy and speed; Ulrich et al. [

23] demonstrated its effectiveness in gesture recognition teaching, using an earlier version of YOLO. YOLOv7 establishes a higher accuracy benchmark through efficient architectural design. SSD (Single Shot MultiBox Detector), a classic single-stage detection algorithm, is characterized by its uniform multi-scale prediction strategy. EfficientNet, an efficient convolutional network based on compound scaling principles, has shown strong parameter efficiency across various visual detection tasks. These baseline models provide a spectrum of design paradigms from classical to state-of-the-art, providing a comprehensive reflection of the current average performance level in lightweight detection technologies. Although newer architectures such as YOLOv8 and RT-DETR have emerged, YOLOv5s remains one of the preferred choices in industrial applications due to its stability, mature ecosystem, and extensive deployment experience on embedded platforms. Therefore, using YOLOv5s as the baseline for improvement in this study carries substantial practical relevance.

2.2. Micro-Expression Recognition

Micro-expression refers to a brief facial muscle movement. Research in this field closely relies on advancements in feature extraction and modeling techniques [

24]. Early studies heavily depended on handcrafted features and optical flow methods. Before the rise of deep learning, researchers focused on capturing subtle facial movements from video sequences. Optical flow methods, particularly Cartesian optical flow and local directional optical flow, have been widely employed to quantify the motion vectors of facial muscles. In addition, several feature descriptors specifically designed for facial behavior representation have been proposed and applied [

25]. Among them, the most representative is the local binary pattern on three orthogonal planes (LBP-TOP), which can extract texture features simultaneously across three orthogonal planes, thereby capturing spatiotemporal information effectively. However, these handcrafted features are highly sensitive to image quality, head pose variations, and illumination conditions, and their feature representation capability is limited, resulting in insufficient generalization in complex real-world scenarios. Deep learning, particularly three-dimensional convolutional neural networks (3D CNNs), has led to the first paradigm shift in this field [

26]. The rise of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) has enabled models to automatically learn more discriminative features. Conventional 2D CNNs struggle to effectively capture the temporal dynamics of micro-expressions; therefore, 3D CNNs have been introduced into this domain. The convolutional kernels of 3D convolutional neural networks (3D CNNs) simultaneously slide across both spatial and temporal dimensions, enabling direct learning of spatiotemporal features from video clips, thereby establishing a milestone in micro-expression recognition. For instance, architectures such as 3D Flow CNN process appearance and motion information end to end, significantly enhancing the recognition performance.

One of the current research trends focuses on lightweight model design while maintaining high performance. For example, a practical strategy that balances accuracy and computational efficiency is to employ efficient lightweight 2D convolutional neural networks (CNNs) such as ShuffleNetV2 and MobileNet as backbone architectures, combined with temporal modeling modules. This study aligns with this trend, aiming to provide an efficient and reliable micro-expression analysis component for end-to-end real-time multimodal systems. Furthermore, some recent studies focused on the influence of demographic factors on gesture and expression recognition. For example, Nirmalya Thakur et al. [

27] investigated the differences in gesture usage habits and facial expression patterns among different age and gender groups, while Liselot Hudders et al. [

28] analyzed the impact of cultural background on non-verbal communication behaviors. These studies remind us that, when building universal accessible communication systems, the diverse characteristics of user groups need to be considered.

3. Proposed Methods

3.1. Overall System Framework

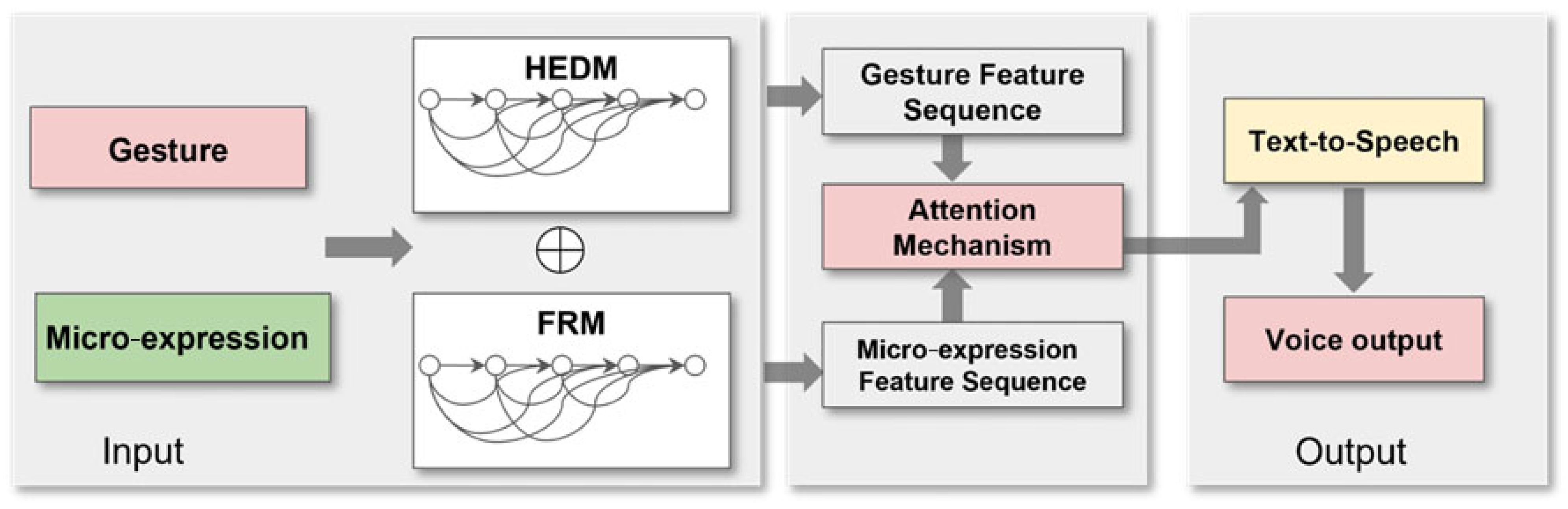

The overall system follows a “perception–cognition–interaction” paradigm and is composed of three core modules: a multimodal input module, a collaborative recognition and fusion module, and a natural speech output module. This framework achieves a seamless transformation from raw visual signals to natural speech streams, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

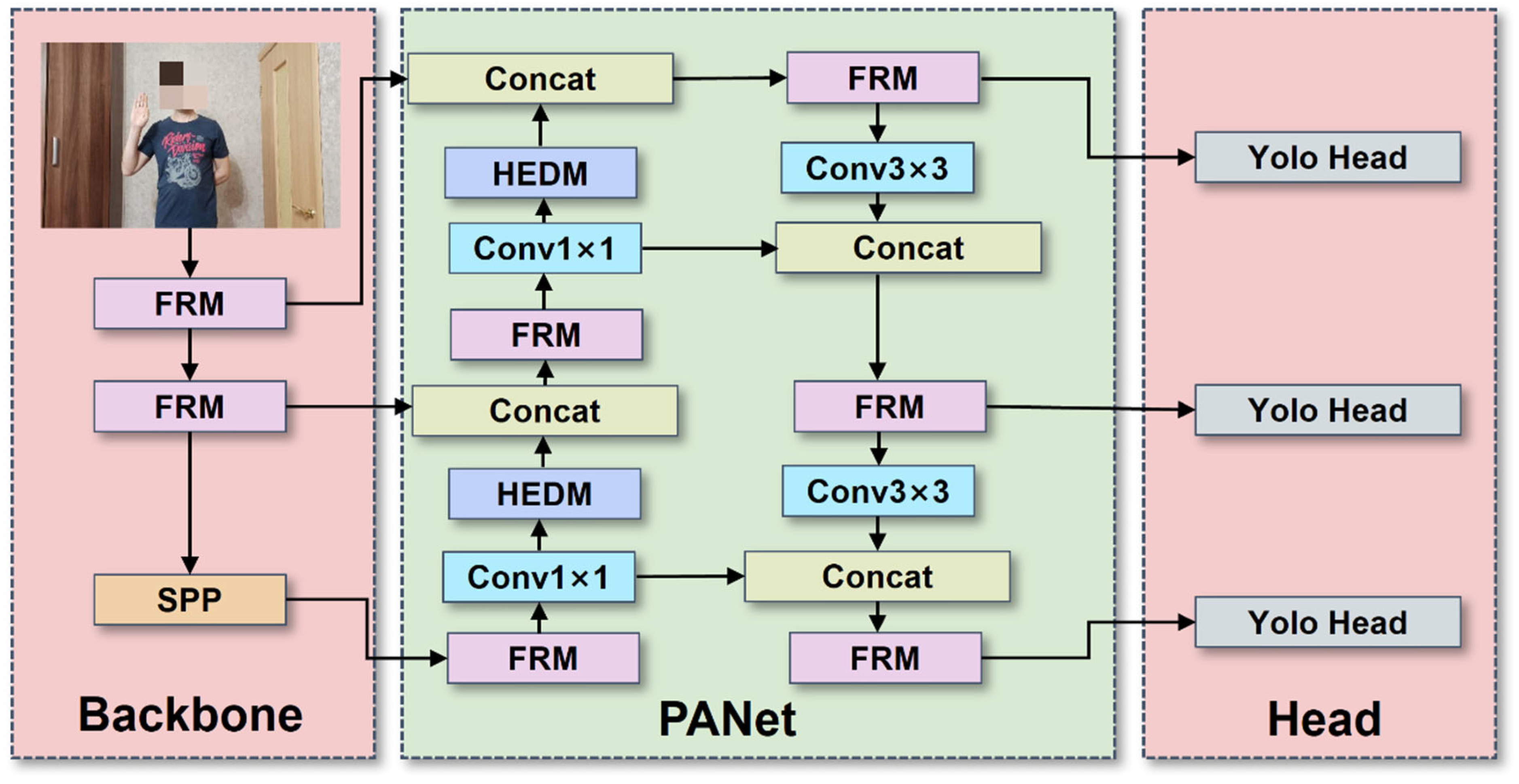

3.2. Improved YOLOv5s-Based Gesture and Micro-Expression Recognition Network

YOLOv5 is a single-stage object detection model with four main components: the input layer, backbone network, feature fusion neck, and detection head. In this study, we introduce a fusion residual module (FRM) and a high-efficiency downsampling module (HEDM) based on the YOLOv5s architecture. These modules significantly reduce the model complexity and computational cost while maintaining the detection accuracy. The fusion residual module (FRM) is embedded after the C3 layer of the backbone network. Its input channel number is 256, and the output channel number is 128. This module employs a combination of 3 × 3 and 1 × 1 convolutional kernels, with a stride of 1 and padding of 1, containing approximately 0.18 M parameters. By constructing residual connections between layers, the FRM enables more direct gradient backpropagation, effectively mitigating the vanishing gradient problem associated with increasing network depth. The module contains multiple sub-paths with varying depths, each possessing differentiated receptive fields, allowing it to extract features incorporating multi-scale contextual information, which is crucial for recognizing gesture targets and micro-expression regions of different sizes.

The hybrid efficient downsampling module (HEDM) is applied during the network’s downsampling stages. Its input channel number is 512, and the output channel number is 256. This module integrates 3 × 3 convolutions, max-pooling operations, and identity mapping, with a stride of 2 and padding of 1, containing approximately 0.32M parameters. By fusing features from multiple downsampling operations, the HEDM maximizes the retention of fine-grained information that is easily lost during downsampling, providing more discriminative feature representations for subsequent network layers.

The structure of the proposed module is illustrated in

Figure 3.

3.3. Multimodal Feature Fusion Algorithm

A single-modality gesture recognition system can convey core semantic information but lacks emotional expressiveness, resulting in rigid and unnatural communication. For instance, when expressing affirmation, a firm gesture (such as a strong nod in sign language) serves as the primary information source, whereas when conveying apology, subtle micro-expressions of guilt carry more critical affective cues. To build a more comprehensive and human-like communication system, we propose an attention-based multimodal fusion method that adaptively and efficiently integrates the complementary information of gestures and micro-expressions.

The gesture feature Fg and the micro-expression feature Fe originate from different modal spaces, possessing distinct statistical properties and semantic granularities. First, the feature vector Fg ∈ Rdg output by the gesture recognition subnetwork and the feature vector Fe ∈ Rde output by the micro-expression recognition subnetwork are projected into a shared common feature space through their respective fully connected (FC) layers, in order to unify their dimensionality and enhance the consistency of feature representations.

The projected features are denoted as

where W

g and W

e are learnable weight matrices, and b

g and b

e denote the bias terms. At this stage, F

g′, F

e′ ∈ R

d. The projected feature vectors are concatenated and fed into an attention network to compute their respective attention scores. This network consists of a fully connected layer followed by a Softmax function:

Here, Wa and ba are learnable parameters of the attention network. The computed αg and αe denote the dynamically learned attention weights, satisfying αg + αe = 1. These weights directly indicate the relative importance of the gesture and micro-expression modalities in the final decision for the given input sample.

Finally, the learned attention weights are applied to perform a weighted summation over the original projected features, yielding the final multimodal fused feature F

fusion:

The fused feature function Ffusion simultaneously encodes gesture semantics and micro-expression affective information, with adaptive information flow regulation achieved through the weight α. Ultimately, Ffusion is fed into a shared classifier (typically composed of multiple fully connected layers) for joint recognition, outputting concrete semantic text labels (e.g., “joyful greeting”). This fusion mechanism forms the core of human-like intelligent communication systems, ensuring both the contextual accuracy of output statements and the conveyance of the corresponding emotional intonation.

3.4. Speech Synthesis Module

The speech synthesis module serves as a key component in achieving the system’s ultimate goal—establishing a closed-loop human–computer interaction framework to enable barrier-free communication. This module receives the semantic text output from the multimodal fusion recognition module and converts it into natural, fluent, and intelligible speech signals, ensuring that visually impaired users can intuitively perceive the conveyed information. The core design principles of this module emphasize high naturalness, low latency, and seamless system integration. In the output stage, the recognized results are transformed into human-like speech through a text-to-speech (TTS) module, which can be implemented using technologies such as Google TTS API or PaddleSpeech. This process enables real-time delivery of recognition results to visually impaired individuals, ultimately forming a natural interaction loop of “gesture/expression → speech.”

4. Experiment and Analysis

4.1. Datasets

Training and validation for gesture recognition were primarily based on the HaGRID dataset [

29], which contains over 20 gesture categories, a large sample size, and diverse backgrounds. We randomly selected 9935 high-quality images from the dataset and divided them into training, validation, and testing sets in an 8:1:1 ratio. To ensure balanced representation, we employed a stratified sampling strategy, maintaining similar class distributions across all splits. Our data augmentation strategy included mosaic augmentation (using 4-image mosaics during training), HSV color space adjustments (±30% for hue, saturation, and value), random horizontal flipping (50% probability), and scale variation (±20% scaling). Background negative samples were evenly distributed across all splits to prevent data leakage. The histogram of the dataset categories is shown in

Figure 4.

Furthermore, to evaluate the model’s generalization ability, we conducted zero-shot gesture detection experiments on static frames from the RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather [

30] dataset, using only the hand region annotations from its frame-level annotations as detection targets, without involving sequence modeling or translation tasks. For the RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather evaluation, we mapped gesture categories based on semantic similarity. The correspondence between HaGRID gesture labels and RWTH sign language glosses was established through annotation, focusing on shared semantic concepts (e.g., “call” → “TELEFONIEREN”, “stop” → “STOPPEN”). Micro-expression categories were aligned with sequence-level semantics through emotion-intention mapping rules validated by domain experts. The label mapping between HaGRID and RWTH-PHOENIX is shown in

Table 1.

For categories that could not be directly mapped, we applied the following rules: direct one-to-one mapping for exact semantic matches (high confidence); mapping based on gesture form similarity for partial semantic matches (medium confidence); and exclusion from zero-shot evaluation for categories with no clear correspondence.

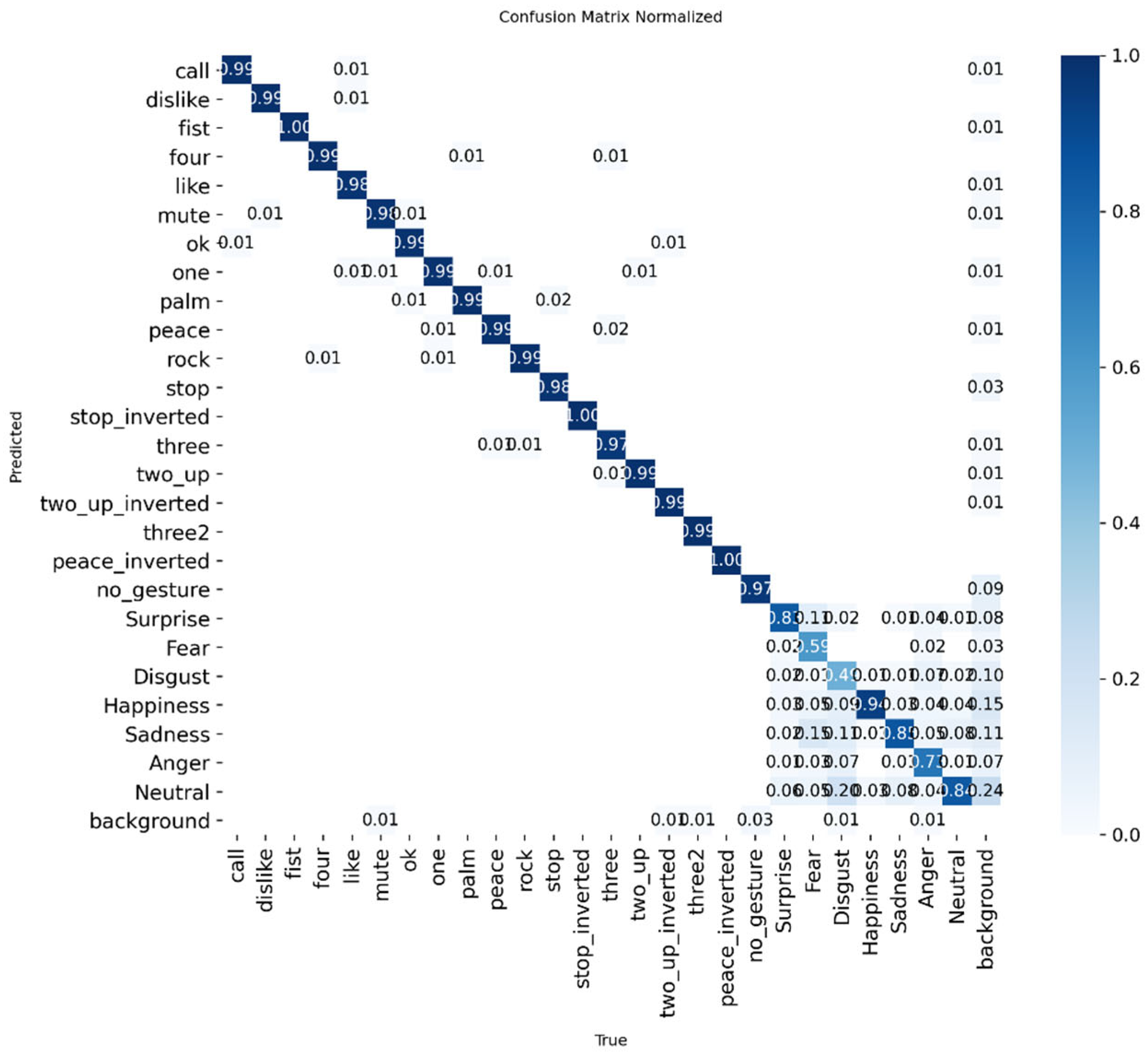

For micro-expression training and validation, we employed a curated and cleaned dataset comprising seven prototypical facial expression categories: surprise, fear, disgust, happiness, sadness, anger, and neutral. The dataset ensures data integrity, class balance, and high-quality annotations, with a total of 15,500 valid images.

This study adopted the unweighted average recall (UAR) and unweighted F1-score (UF1) to address class imbalance issues. All samples from the same individual appeared only in either the training set or the testing set to prevent identity information leakage. During the annotation process, three annotators were invited, and their inter-rater agreement was 0.75, indicating good annotation quality. These protocols ensured the reliability and comparability of the evaluation results.

After merging the two datasets for training, the resulting dataset confusion matrix is shown in

Figure 5.

4.2. Experimental Platforms and Related Indicators

The experiments in this study were conducted on an Ubuntu operating system with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB VRAM) and an AMD EPYC 7502 CPU. The training environment was configured with Python 3.8.20, PyTorch 2.0.1, and CUDA 11.7. To ensure consistency across experiments, no pre-trained weights were used for any of the models. The detailed training parameters are listed in

Table 2.

For the deployment-phase evaluation, the inference speed was assessed on the Jetson Nano platform, which features an ARM Cortex-A57 CPU and a 128-core Maxwell GPU. The hardware configuration is summarized in

Table 3.

Model detection performance evaluation is a multidimensional process. In this study, the system’s performance was assessed from three perspectives: detection speed, model complexity, and speech quality. The detection speed metrics include floating point operations (FLOPs) and frames per second (FPS). FLOPs measure the number of floating point operations required for a single forward pass—i.e., the entire computation process from input to output. A larger FLOPs value indicates a higher computational demand, while a smaller FLOPs value implies a lower computational cost and reduced resource (GPU/CPU) and time requirements. FPS, on the other hand, represents the model’s processing speed when handling input data. In this experiment, five key evaluation indicators were employed: model weight size, FLOPs, FPS, number of parameters, and mean opinion score (MOS).

The mean opinion score (MOS) evaluation followed the ITU-T P.800 standard. We recruited 30 native Chinese speakers (balanced gender, no hearing impairments) to participate in a quiet indoor environment using headphones. The evaluation used a 5-point scale (1 = Bad, 5 = Excellent). Each evaluator listened to 50 system-generated speech samples played in random order and rated them in terms of naturalness and intelligibility. The final reported MOS was 4.45 ± 0.32 (mean ± 95% confidence interval). The reported latency (<0.8 s) is the end-to-end delay, covering the complete process from input visual signal to output speech.

4.3. Ablation Experiments

To validate the effectiveness of each proposed module in this paper, we extracted continuous sign language videos from RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather frame by frame, used the provided hand bounding box annotations as detection targets, ignored their sequence labels, and conducted systematic ablation experiments. The results are shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

After introducing the HEDM, the model achieved a 2.9% accuracy improvement while reducing the parameters and FLOPs by 0.7 M and 1.8 G, respectively, with a concurrent FPS increase—demonstrating the superiority of our lightweight design. Further integrating the FRM enabled the largest parameter reduction, indicating that the combined HEDM–FRM framework enhances feature interaction and optimizes the lightweight backbone, thereby significantly improving the gesture and micro-expression recognition.

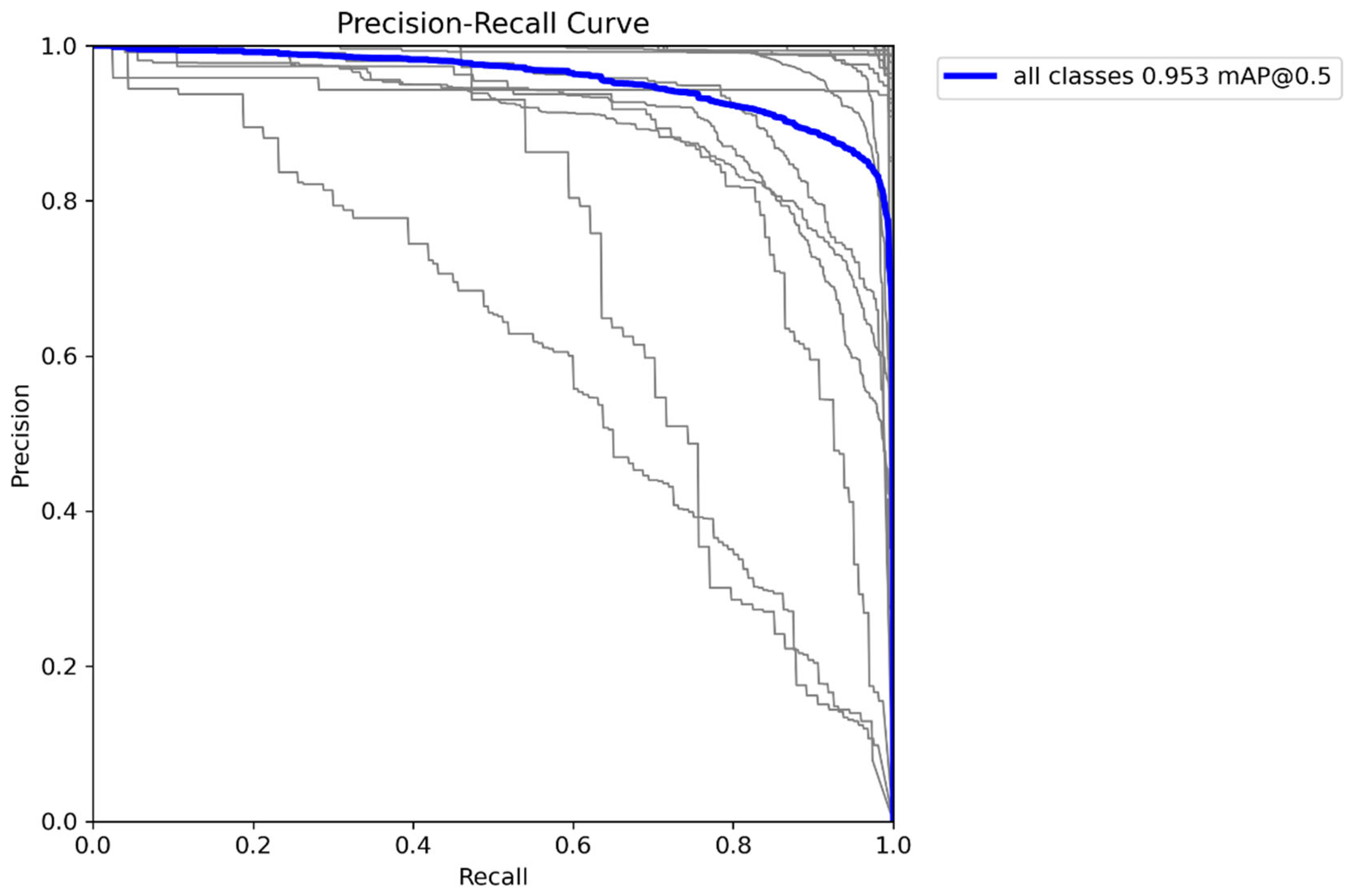

The gesture–micro-expression multimodal fusion achieved a peak accuracy of 95.3%. Although this introduced a slight computational cost increase due to additional parameters, the substantial accuracy gain strongly demonstrates that micro-expression integration compensates for the semantic limitations of gesture-only modalities, thereby enhancing the system’s overall perceptual capability.

4.4. Comparative Experiments

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our multimodal fusion system on gestures + expressions, we compared the complete multimodal fusion system with current mainstream gesture and micro-expression recognition methods, and the results are reported in

Table 6.

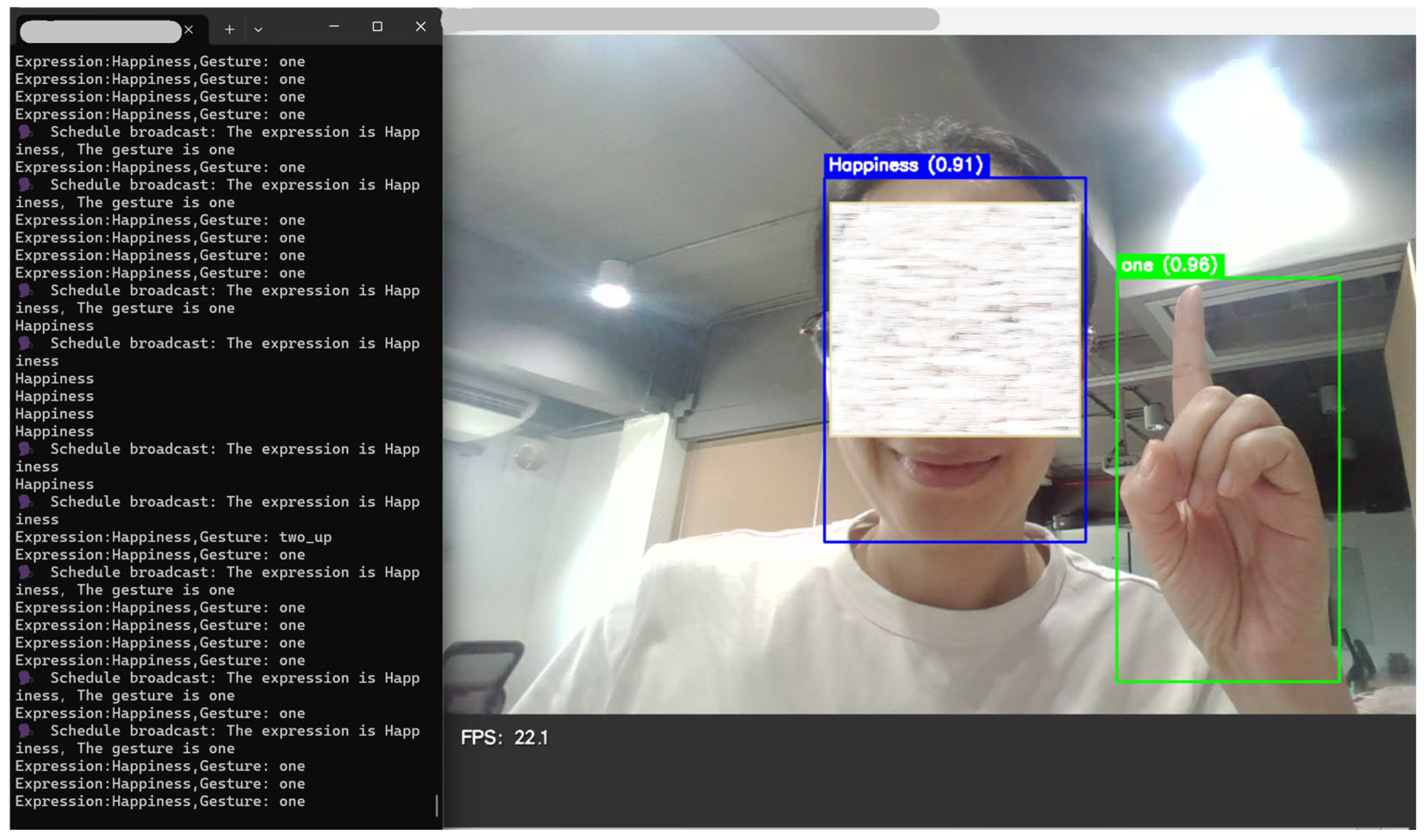

Our model demonstrates superior performance over all the compared methods on both key accuracy metrics (mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95), validating its advanced capability for gesture recognition tasks. In terms of speed, the proposed model maintains highly competitive FPS on both high-end GPUs and embedded devices. Notably, it achieves a peak frame rate of 22 FPS on the Jetson Nano platform, benefiting from its carefully designed lightweight architecture. This design ultimately achieves an optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

From the ablation and comparative experiment results, we observe the following: the ablation study (

Table 4) shows that our model achieves an mAP@0.5 of 95.3%, representing an improvement of 4.1 percentage points over the baseline YOLOv5s (91.2%0.3%). Similarly, in the comparative experiments against the baseline models (

Table 6), our model attains an accuracy of 95.3%, substantially outperforming the other methods and further confirming the reliability of the proposed improvements.

4.5. System Performance Analysis and Visualization

Tests were conducted separately on the gesture HaGRID dataset and our curated micro-expression dataset. The gesture recognition accuracy reached 98.6% (UAR: 98.3%, UF1: 98.4%), and the micro-expression recognition accuracy reached 92.4% (UAR: 90.1%, UF1: 89.7%), as shown in

Table 7. Through our system, the multimodal joint recognition accuracy on the combined dataset reached 95.3%, meeting the requirements for high-reliability communication. Here, multimodal joint recognition accuracy is defined as the proportion of samples in the multimodal testing set in which the system correctly outputs the combined gesture + micro-expression label. This testing set contains samples with both gestures and micro-expressions, and the system must correctly recognize both to be considered correct. The final model parameter count was 6.1M, representing a 15.3% reduction compared to the original YOLOv5s; the FLOPs were 13.1G, representing an 18.1% reduction. The inference speed improved significantly, from 3.3 ms for the baseline model to 1.1 ms. The qualitative results are shown in

Figure 6.

To verify whether the attention-based fusion mechanism could adaptively adjust the modality importance based on contextual information, we calculated the average attention weights for different semantic scenarios on the testing set. As shown in

Figure 7, we selected four representative interaction scenarios for analysis: imperative gestures (e.g., “stop”, “quiet”), representational gestures (e.g., the number “three”), and scenarios with strong emotions (e.g., “pleading for quiet helplessly”). This visual analysis proves that our fusion mechanism is not simple feature concatenation but achieves a dynamic, context-dependent information integration, which is key to enhancing the system’s semantic understanding depth and disambiguation.

During comprehensive system testing on the Jetson Nano platform, the average processing speed remained stable at 22 FPS, enabling truly real-time interaction, as shown in

Figure 8. The speech output module achieved an average response latency below 0.8 s and a mean opinion score (MOS) of 4.5, confirming natural and fluent synthesized speech output. The comprehensive experiments validated the effectiveness of the proposed lightweight optimization and multimodal fusion mechanisms. Our system not only outperforms state-of-the-art methods on academic benchmarks but also demonstrates high-precision real-time computation on resource-constrained embedded devices, highlighting its potential for practical assistive applications in barrier-free communication scenarios.

4.6. Qualitative Analysis of Error Samples

To comprehensively evaluate the robustness of the proposed system and identify directions for future enhancement, we conducted a systematic qualitative attribution analysis of misclassified samples in the joint multimodal testing set. Based on an in-depth examination of the error cases, three primary failure modes and their approximate distributions were identified as follows:

Severe occlusion and limb overlap (~45%): This represents the most significant source of recognition errors. When a user’s hands are partially or fully occluded by other objects, clothing, or the opposite hand, the model fails to extract complete structural features. Similarly, in multi-person interaction scenarios, overlapping gestures between individuals often lead to false detections and misclassifications.

Drastic illumination changes and extreme viewpoints (~36%): Sharp variations in environmental lighting—such as overexposure under intense illumination or detail loss in low-light conditions—severely degrade the clarity of gesture contours and micro-expression textures, thereby diminishing the mode’s discriminative capability.

Emotional ambiguity and cultural-context variation (~19%): Certain subtle facial expressions (e.g., contempt vs. disgust) exhibit high visual similarity, making them difficult to distinguish even for human annotators. This inherent ambiguity, combined with cross-cultural differences in interpreting nonverbal cues, contributes to frequent misclassifications.

The above findings clearly highlight the current limitations of the system in real-world deployment. Future work will focus on addressing these weaknesses through adversarial occlusion training, multi-view and perspective-aware data augmentation, temporal modeling to mitigate motion blur, and the collection of culturally diverse datasets, aiming to further enhance the system’s robustness and generalization performance in complex real-world environments.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a real-time barrier-free communication system based on an improved YOLOv5s architecture with multimodal fusion of facial micro-expression and gesture information. By introducing the high-efficiency downsampling module (HEDM) and fusion residual module (FRM), the system reduces the model complexity while improving the gesture recognition mAP to 95.3%. An attention mechanism enables dynamic weighted fusion of gesture and micro-expression features, achieving a multimodal joint recognition accuracy exceeding 95% and addressing the lack of emotional expressiveness in unimodal gesture interaction. The system validation demonstrated real-time performance at 22 FPS, with speech output latency below 0.8 s and a mean opinion score (MOS) of 4.5, confirming its strong potential for practical applications.

Although the proposed system delivers strong performance in both gesture and micro-expression recognition, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, we did not perform a stratified analysis based on demographic attributes (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity) to examine potential group-wise differences in recognition performance. Previous studies have shown that demographic factors can markedly influence gesture patterns and facial expression characteristics. In our current evaluation, we implicitly assumed that the model behaves consistently across all user groups, an assumption that may not hold in realistically diverse populations. In future work, we plan to incorporate more representative and demographically balanced datasets and to conduct comprehensive subgroup analyses to ensure equitable performance across different demographic groups. We also intend to extend the multilingual sign language dataset, explore novel interaction modalities, and adopt more advanced model compression techniques, moving toward a next-generation barrier-free communication platform that is context-adaptive and capable of rich emotional expressiveness.