Abstract

Real-time location systems (RTLS) can be implemented in aged care for monitoring persons with wandering behaviour and asset management. RTLS can help retrieve personal items and assistive technologies that when lost or misplaced may have serious financial, economic and practical implications. Various ethical questions arise during the design and implementation phases of RTLS. This study investigates the perspectives of various stakeholders on ethical questions regarding the use of RTLS for asset management in nursing homes. Three focus group sessions were conducted concerning the needs and wishes of (1) care professionals; (2) residents and their relatives; and (3) researchers and representatives of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The sessions were transcribed and analysed through a process of open, axial and selective coding. Ethical perspectives concerned the design of the system, the possibilities and functionalities of tracking, monitoring in general and the user-friendliness of the system. In addition, ethical concerns were expressed about security and responsibilities. The ethical perspectives differed per focus group. Aspects of privacy, the benefit of reduced search times, trust, responsibility, security and well-being were raised. The main focus of the carers and residents was on a reduced burden and privacy, whereas the SMEs stressed the potential for improving products and services.

1. Introduction

Lost and misplaced items are a common cause of inefficiencies in health care, and a source of frustration for staff and care recipients alike. Especially in nursing homes, where residents with dementia deal with the consequences of memory loss, retrieving lost and misplaced items can be quite a challenge. Older people with dementia may engage in hoarding behaviour or hide their personal possessions, including valuables and assets owned by other residents or the nursing home organisation itself [1,2]. In addition, care professionals tend to lose or misplace items, often under the pressure of time, which, in turn, have to be retrieved by colleagues [1,2]. This goes along with high costs when an item has to be replaced by either the relatives of a resident or by the nursing home organisation. The scale of these financial and practical implications is yet unknown. This study is part of a larger programme which aims to solve these problems in a responsible and effective manner by introducing track and trace technologies in the nursing home, taking into account the requirements of all involved stakeholders and especially the privacy of the care professional and the residents [1,2,3]. Systems that use track and trace technology indoors are also known as real-time location systems (RTLS). These technologies were first introduced in industry and later in healthcare, particularly in hospitals [2,4]. Technological developments have led to a wide range of (commercially) available RTLS that vary in price and accuracy. All these systems have one feature in common, namely, that they work with (1) tags that can be attached to assets that are prone to be lost or misplaced; and (2) beacons on fixed locations in the premises that gather information on the location of these tags [2,5].

RTLS have been widely researched in the context of hospitals. From a review study by Oude Weernink et al. [2], it became clear that the adoption of RTLS by care professionals and clients is rather low. There are many different causes of the improper acceptance of RTLS. Often the systems are not well-fitted to the specific requirements of the end-users in a specific context. Furthermore, it is not transparent to the end-users which data are collected and where and for how long these data are stored. In particular, care professionals worry about their own privacy and the privacy of their clients [2]. This hampers the effective implementation of RTLS, and sometimes it leads to a complete rejection of the technology altogether [6,7].

In the Netherlands, the development and implementation of healthcare technology is recognised to be essential for the future of aged care. Many innovations find their way into the hospital environment first, before being introduced to the nursing home context. For instance, the application of RTLS in nursing homes has not been as extensively researched as the use of RTLS in hospitals, although the nursing home environment has its unique set of challenges [2,3]. The most important difference is that hospitals revolve around cure, and patients are discharged at ever increasing rates, while residents of nursing homes often live in these facilities for as long as their lives last. In addition, residents of nursing homes bring a large range of personal items with them.

Different stakeholders are involved when it comes to the implementation of RTLS in nursing homes, for instance, care professionals and managers, but also the residents as well as their relatives, who act as representatives when their loved-ones are no longer able to make decisions about the deployment of technology in their rooms themselves [3]. Also, the vendors of RTLS play an important role in the adoption and acceptance of these systems in practice.

Using RTLS invokes many questions about the aspects of privacy of the various groups of stakeholders. The law seems to keep up with the development of new technologies, but what is lawful is not always ethically correct and desirable. Previous studies have provided in-depth discussions of privacy laws concerning, and the legal implications of, RTLS [8,9]. For many years, smart technologies and home monitoring of people has already provoked ethical discussions in areas such as the autonomy and privacy of older people, as well as data security and protection, and the prevention of harm [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Most of the discussions labelled as ethics are in fact legal discussions that can be solved by applying law [8,9]. Still, the current national and European legislation leaves room for discussions about the ethical boundaries of the application of RTLS for asset management. For instance, being able to locate a wheeled walker, which may go missing, can potentially save time. But usually a wheeled walker belongs to a resident, and when used, the RTLS indirectly tracks the movement and whereabouts of this end-user [8,9].

So, the question is which ethical principles and guidelines can be established when it comes to accounting for the decision whether or not to deploy RTLS in nursing homes? In this study, ethical issues regarding the use of RTLS for person-connected and non-person-connected technologies and items in the nursing home are explored from the perspective of different stakeholders. The exploration encompasses (1) the ethical views and opinions among the various groups of stakeholders (residents, relatives, care professionals, representatives of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and researchers) in relation to the advantages and disadvantages of RTLS, a potential change in roles, beliefs and behaviours; (2) the perceived responsibilities towards the RTLS; (3) the influence of RTLS and their design on the perception of the nursing home environment; and (4) the perceived impact of RTLS on the sense of safety and security in the nursing home. This study aims to explore these aspects by mapping the different attitudes towards the use of track and trace technology, and by considering the different needs and requirements from the involved stakeholders in designing such RTLS. In this way, conflicts as well as a level of potential consensus may be identified and acted upon before implementation. Before discussing the perspectives of the involved stakeholders, a theoretical framework is presented as an introduction to ethics in healthcare.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Ethics: An Overview of Principles

Ethics in research and in health care has the primary goal to make careful considerations to protect participants, care recipients and patients from being harmed. Ethics means thinking about “doing good”. Central to ethics is the question what is the good thing to do in a specific situation. The Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates (470–399 BCE) can be seen as the founder of this discipline. Socrates claimed that everywhere where people meet, ethics is involved. When people live and work together the question arises how this can be done in the best possible way. Ethics is all about considerations, not about answers, or being right or wrong. Ethics is about morality. According to Beauchamp and Childress, the common morality is the set of norms shared by all persons committed to morality by which we rightly judge the conduct of “all persons in all places” [17] (p. 3). In other words, morality is the precipitation of what behaviour is accepted in a given community as a matter of course. It is the expression of a correct way of living or working in a community in which its values and standards are reflected. Values are the starting points for our actions; they are the ideals of good lives that we strive for in our behaviour. Standards are based on those values and forms, as it were the rules of coexistence and cooperation. They allow for good behaviours.

2.2. General Ethical Principles in Care

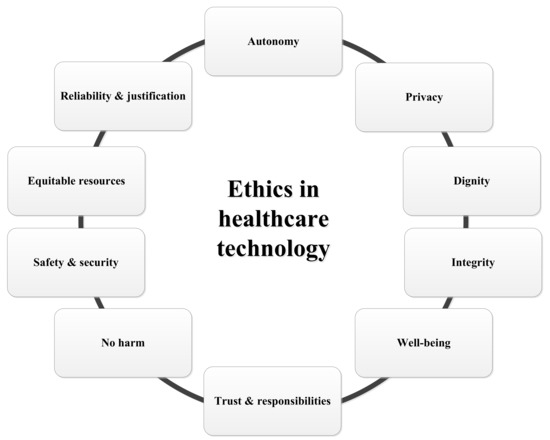

Two different types of ethics exist: obligatory ethics and virtue ethics. Obligatory ethics is focused on rules and regulations; what you should or should not do. Virtue ethics in healthcare is characterised by showing the right attitude, the right character or manner in professional acts. The assumption here is that when good people determine the policy, it leads to a good result. Among care professionals this can be seen in traits like regularity, patience, wisdom and caring. Before we discuss ethical principles related to the implementation of technology in healthcare, four general ethical health principles are explained: autonomy, doing no harm, well-being and the equitable distribution of sources (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ethics in healthcare technology.

2.2.1. Autonomy

In health care it is considered to be self-evident that, for example, physicians and nurses inform care recipients about what happens to them. This is a standard originating from the value or ideal of autonomy. The concept of autonomy refers broadly to independence. In relation to quality of life, autonomy refers to the sense of being able to give form and content to the private life itself; being able to manage day-to-day business oneself. This is consistent with the meaning given to the concept of autonomy in healthcare and medical ethics: the right to determine for oneself what is going to happen.

2.2.2. No Harm to the Client and Well-Being

The second ethical health principle is to do no harm and try everything in your power to improve the well-being of the client is the third principle. But as clear as it sounds, doing no harm is not one-sided. For instance, when you plan extra investigations before acting, the investigations may entail physical harm, as well as the time and cost of attending for diagnostic procedures, anxiety while waiting for results, and any side effects or complications from treatment [18]. Secondly, the decision what to do for a certain individual can be made on rational thinking and by acceptance of someone else’s opinion. Meanwhile, it is widely accepted that individuals are the best judge of their own interests, and should be allowed to make decisions that affect their own well-being, as long as others are not harmed [18]. But what is good for one person can negatively affect someone else.

2.2.3. The Equitable Distribution of Resources

The healthcare infrastructure has a massive impact on improving the overall health in the society. It is an important component in the development of a country, and, consequently, the investments in healthcare systems are significant. Two major considerations should guide the evaluation of healthcare projects: (1) efficiency, a measure of the degree to which system outputs achieve a theoretical maximum (minimum) using the same level of inputs, and (2) equity, a measure of the distribution of outputs (or inputs) across the population [19]. However, the most commonly used tool for policy analysis is the so-called cost benefit analysis, which leads to a focus on efficiency aspects rather than on equity [20].

Reducing the per capita cost of health care has a downside risk in discriminating against older people. Sometimes medical doctors decide not to treat a person because his life expectancy is short and by not treating, high costs can be prevented. Discrimination against older persons on the basis of their age has been identified as the major barrier to accessing primary care and preventing chronic illness [21]. Grover [22] noted that discriminatory attitudes of medical professional towards older persons could also undermine meaningful communication with their patients and care recipients, and as a result may affect the accuracy of diagnosis and the quality of treatment. He called upon United Nations’ member states to respect the right to health by refraining from various discriminatory practices [22].

2.3. Triple or Quadruple Aim of Care

The Triple Aim is an approach to optimising the performance of a healthcare system, proposing that institutions simultaneously pursue three dimensions of performance: improving the health of populations, enhancing the experience of care, and reducing the per capita cost of health care [23]. The compass points described in the Triple Aim are (1) better care; (2) better health; and (3) lower costs. Leaders and providers of healthcare should consider adding a fourth dimension to the Triple Aim, namely, improving the work life of those who deliver care [23]. Bodenheimer and Sinsky [23] stated that the outcome of health care processes is negatively affected by work stress, few changes of personal innovation and low work motivation. In order to deal with conflicts around complex actions in a professional manner, care professionals should thoroughly weigh the basic principles of medical ethics on an individual basis [24].

2.4. Ethical Issues Related to Healthcare Technology

Besides the general ethical health principles, several other ethical issues surround the use of monitoring technology such as track and trace systems in nursing homes. According to van den Hoven [25], one obstacle to an adequate view of the relation between ethics and technology stems from Aristotle, namely the radical distinction between genuine action and production including engineering (praxis versus poesis). Praxis is the domain of ethics (phronesis), whereas poesis is the domain of instrumental reasoning (techne), not ethics. In modern times, praxis and poesis are inextricably linked [25]. In Figure 1, ethical principles related to healthcare technology are displayed: trust, responsibilities, autonomy, security, safety, privacy, integrity, dignity, reliability and justification. All these issues can coincide with each other. For instance, privacy matters can have an impact on trust, autonomy and security/safety and lead to responsibilities of all involved. At the same time when a person’s autonomy is at risk based on his health condition, that justifies the use of a technological aid, one needs to trust someone else in choosing the best fit aid in order to retain one’s autonomy.

2.4.1. Privacy, Dignity and Integrity

In the context of the well-being of older persons, promotion and protection of human rights become difficult due to social exclusion of older citizens as persons with disabilities and/or the “poorest of the poor” [26]. This is also true for people with complex health needs. The human right to health, understood as the right to the highest attainable standard of health, has appeared on international agendas as one of the most current and complex issue of human rights law. Undoubtedly, there is a close link between international human rights law and ethics. They both operate at different levels, but their aims are convergent. Both aim to preserve human dignity, also in situations of illness, disability and at the final stages of human life. We will delve into the ethical and legal issues related to the allocation of technical solutions to support people with a demand for care or with a certain health problem.

When discussing human rights, the issue of inalienable human dignity is usually considered. In general, at international forums, the notion of human dignity means the equal and inherent value of every human being, regardless of gender, race, nationality, origin, religion, political opinion, property status, sexual orientation and, certainly, age [21]. The concept of dignity generally enjoys common appreciation at the international level, but currently its contents are unclear and disputable. It is evolving due to new achievements of medicine and allied healthcare [25], including those aimed at the prolongation of human life. The question that rises is “to what extent can technology be helpful in maintaining human dignity in care processes?”

2.4.2. Trust and Responsibilities

Trust and responsibilities are closely linked with autonomy. People with health-related problems need to trust other people and give away responsibilities they were used to take themselves, to professional carers. But, likewise the professionals need to give back responsibilities to the people with health-related issues when they are able to make their own decisions (self-management) if, when and what type of technological aid one will use to cope with the health or social burden. It is also about the right of patients to make decisions about their medical care, without their health care provider trying to influence the decision-making process. Patient autonomy does allow for health care providers to educate the patient but does not allow the health care provider to make the decision for the patient.

2.4.3. Security and Safety

Security and safety are important concepts in relation to the use of track and trace technology in nursing homes. Safety is a basic human need, which can be interpreted in many different ways, depending on one’s personal context and standpoint. In research by Musschenga et al. [27], cameras were placed throughout the nursing home in order to improve the residents’ safety and security. However, although the intention was to improve safety by enhancing surveillance at the residents and the environment, the actual result was a deprivation of freedom for both the residents and the care professionals of this nursing home. Some residents showed behavioural symptoms, which required the care professionals to find out why these residents showed such behaviours. This is an example of how autonomy and freedom collide with safety and security.

2.5. The Ethics of Monitoring Technologies

In the study by Leikas and Kulju [10], technology ethics is described as a field of applied ethics that examines ethical problems that can be created, transformed or exacerbated by technology. The impact of RTLS, for instance, can be assessed against a number of ethical principles that are considered universal ethical values, which should be discussed in a practical manner in order to be useful for technology design. When discussing the ethics of monitoring technologies in the context of the everyday lives of older people, Leikas and Kulju [10] described a number of theoretical frameworks that are relevant for the ethical design of technology. In such frameworks, ethical choices and values are reflected and resolved within the design decisions; and ethical issues may concern the adoption and use of technology-supported services for older people in daily life as well as in responsible research and innovation. Moreover, Leikas and Kulju [10] identified a number of relevant ethical principles and values in their study including integrity and dignity; privacy; autonomy; reliability; justification and e-inclusion; the role of technology in society (improving quality of life, not causing harm); informed consent; and meaningfulness (having added value for the individual). As modern ICT solutions go through an ever increasing process of miniaturisation, van Hoof et al. [28] and Niemeijer et al. [29] addressed the fact that monitoring technologies that seem invisible to the normal eye may be considered as “out of sight, out of mind”. People may have a diminished awareness of such technologies and may be less outspoken in any complaints or objections. One could question if informed consent may reflect a true state of informedness, especially when dealing with residents living with dementia. Marshall [30] asked herself a number of ethical questions on the use of technology at home by older people with dementia. For instance, how can we know if the person with dementia consents to the use of technology? Or, do people with dementia and their family carers have equal access to technology, and which person benefits most from the technology? According to Marshall [30], “the person with dementia ought to be the person who benefits at least as much as other people, but I am sure we can all think of situations where this would not be the case”. Similar ethical questions are posed by Bjørneby et al. [12] and van Berlo [31], who stated that the following issues should be considered in the use of technology: (i) the purpose of introduction; (ii) degree of involvement and consent of the person with dementia; (iii) who is to benefit most; (iv) is technology replacing human input; and (v) effects on the person with dementia.

In addition, Hertogh and Wouters [32] discussed that the relationship between the professional carers and residents can change due to the implementation of surveillance and monitoring technologies in aged care. For instance, the interaction between the two groups will lessen during the night hours as technology substitutes night-time visits. At the same time, groups of residents who need attention the most may find themselves in a situation where there is more time available for a chat. Other residents may get less attention, which may in turn lead to feelings of loneliness among those who value having contact with others more than their personal sense of autonomy. In the studies above, the technologies in question encompass the monitoring of human beings in a certain context. In the present study, the RTLS are implemented to track assistive technologies, not nursing home residents themselves.

2.6. Different Perspectives

Using the four general ethical principles as described in the aforementioned paragraphs, namely, autonomy, doing no harm, well-being and the equitable distribution of sources, should be the backbone of the treatment of a care recipient [33]. But, this explanation of ethics in care and technology is not complete if the well-being of the professional is not acknowledged too. In dealing with clients one should consider the care professionals’ perspective and their virtues as empathy, caring, wisdom and patience. Besides the care professionals, other stakeholders like the residence management and the product developers of technological aids and monitoring devices need to address ethical considerations during the whole process of product development.

Different perspectives of clients, SMEs, care professionals or medical doctors require a careful comparison and weighing, in order to come to an ultimate judgement. Often these different perspectives lead to more detailed but even so less clear insight in the whole picture [34]. Additionally, developers of technological aids and monitoring devices need to address ethical considerations during the whole process of product development. Choices in the production process need to be based mainly on end-user demands and preferences. Finally, in case of nursing homes, management decisions have an important impact on choices too. In this research project we wanted to clarify the different perspectives of all stakeholders on the general and technology-related ethical issues, by mapping the different attitudes towards the use of track and trace technology and considering the different needs and requirements from the involved stakeholders in designing such RTLS.

3. Methodology

3.1. Focus Groups

An interactive, qualitative study design was chosen for the study, namely, a multi-focus group study, which followed an earlier study by van Hoof et al. [35]. A focus group approach enables insights to be gained into participants’ shared understanding of the issues [36,37]. According to Kitzinger [36], focus groups are a form of group interview that capitalises on communication between research participants in order to generate data. Focus groups explicitly use group interaction as part of the method. This means that instead of the researcher asking each person to respond to a question in turn, people are encouraged to talk to one another. The method is particularly useful for exploring people’s knowledge and experiences. Focus groups can encourage participation from those who are reluctant to be interviewed on their own, and encourage contributions from people who feel they have nothing to say. Focus groups are useful when exploring subjective meanings and understandings from the research participants’ perspective, particularly when it is useful to explore similarities and differences in participants’ views and experiences [38]. Between-group differences were investigated in this study. The purpose of this methodology was to present a picture of the needs of three stakeholder groups, i.e., residents/relatives, professional carers and SMEs/researchers.

3.2. Participants and Procedure

A total of 25 participants joined in three focus group sessions that were held in December 2016 and January 2017. Each session lasted for 60 to 90 min. The participants were either (1) care professionals; (2) residents and their relatives; and (3) researchers with a background in healthcare and technology and representatives of SMEs that were members of the project consortium (Table 1). This approach allowed for a comparison of the results of the various stakeholders. The focus groups consisted of 6 care professionals, 2 residents and 4 relatives, and 6 researchers and 7 representatives of SMEs. The first two sessions were held in the nursing home environment for logistical reasons (i.e., nursing home residents and the carers did not have to travel far), and the third session at the university campus. Recruitment took place with the help of the nursing home organisation participating in the research consortium (groups 1 and 2), and via the project coordinators (group 3). All participants signed informed consent forms at the beginning of the sessions when the procedure of the focus group was explained. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [39], but the need for ethical approval was waived (Fontys Committee for Ethics in Research) due to the character of the study, given that data were presented anonymously.

Table 1.

Study participants.

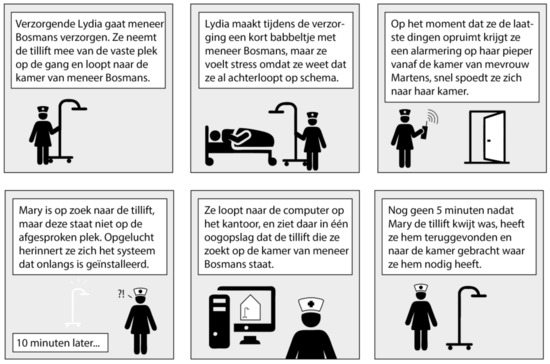

First, the goal of the focus group session was explained to the participants. The focus groups were based on propositions (that were first answered to by yes/no/neutral by using three types of coloured hands (Figure 2)) and an extended topic list for questioning. At the start of each session, a scenario was read out aloud (as presented in a Microsoft PowerPoint presentation), which explained the RTLS as a technological concept (Figure 3). This was followed by a short brainstorming session discussing what privacy meant to the individual participants.

Figure 2.

Overview of thumbs used for the focus group sessions.

Figure 3.

Overview of the scenario presented to the participants in Dutch.

Each of the three focus groups made use of a topic list, which was customised for each session, and based on the roles of the stakeholders and grounded in the available literature [29,40,41]. After the “what does privacy mean to you” question, the focus group started, and dealt with the following topics: (1) personal perception of privacy; (2) change in roles; (3) attitudes and behaviours during activities; (4) responsibilities; (5) perception and safety & security; (6) efficiency versus privacy; and (7) an open question.

3.3. Data Analysis

During the focus group sessions, conversations were audiotaped. These conversations were afterwards transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were anonymised to ensure confidentiality. All transcripts were read and the analysis included a process of open, axial and selective coding. Quotes that summarised the essence of the participants’ experiences were recorded (REL = relative; CP = care professional; SME = representative of small and medium-sized enterprise; RES = researcher). Researcher triangulation was applied during the entire process, for example, separate analyses of the transcripts were conducted by three of the authors (JV, YvZ, JvH). The results of the three focus groups were compared for between-group differences in perspectives and attitudes.

4. Results

4.1. Insights Concerning Benefits and Disadvantages, Changing Roles And Behaviours

Informal carers do not experience any burden when care professionals are looking for missing items, but stressed that it would be desirable if items could be returned as soon as possible. This would also reduce the risk for panicking. In other cases, such as with wheeled walkers, other residents may accidently take the item.

“It is matter of simply asking the system where [it] is, and you will easily find it!”[REL2]

An RTLS solution may provide a quick fix, which may relieve the burden for the busy professional carers. Trust and mistrust play a significant role among informal carers, such as the risks concerning fraud, and poor security of data. A lack of trust may result in a lower acceptance of the RTLS solution. Informal carers do not see a potential change in the role and interaction between the stakeholders with the introduction of the RTLS. Care professionals would remain as helpful as usual, and residents would not even notice the fact that items are being traced.

“I think their attitude towards the residents would never change, with or without the use of a new system.”[REL1]

Informal carers do not have the need for access to the RTLS solution in order to look for missing items. Reducing the time needed to search for items may lead to more time that is available for personal engagement. Being able to trace indispensable items as glasses and walkers is seen as essential in being able to function well. The RTLS solution is expected to be accessed only in cases of emergency, when something is lost that needs to be found back.

“I don’t want to access the system. It is probably too complicated for me to learn, but it may save me money and stress.”[REL4]

Professional carers see advantages in being able to trace assistive devices that are being used on a daily basis, such as blood pressure meters and oxygen saturation meters. Being able to trace keys, which go missing on a regular basis, is seen as convenient. Managers should, however, not be able to see where the keys have been as a part of monitoring work routines of staff. Care professional expect that roles and attitudes may change over time, as more time may become available for personal attention as less time is wasted on searching for items. One would no longer have to make unnecessary phone calls asking for the whereabouts of an item, which is seen as invasive, but move to a central device to track an item.

“I do spend quite a lot of time calling colleagues to ask where items have gone.”[CP3]

Residents would not notice much of the RTLS device in practice, as long as it is not used for tracing people. When tracing assistive devices goes together with monitoring of the residents, a limit is encountered by the professional carers, for instance, in terms of privacy loss. In addition, the care professionals also expect a higher degree of disregard in the daily work patterns, as a machine takes over when things are lost. Care professionals put the well-being of the residents first, and do not want the RTLS solution to trace people.

“Without or without the use of technology, my top priority will also be the resident.”[CP2]

The representatives of the SMEs and research group see benefits in tracing items in terms of the potential for commercial use of data. The daily process of the provision of care may even be improved based on these data. The availability of data may lead to alterations and optimisations to existing assistive devices such as measures that are related to maintenance and the resistance to wear and tear. Quotes for future projects and maintenance may even be tuned to the outcomes of data processing. The group members stated that one needs to be careful about which type of data is being gathered, and stress the potential benefits for relatives and professional carers when items can be easily retrieved.

“Data on the use of items may help me improve my services to nursing homes.”[SME5]

Group members see benefits when motion patterns of devices are known, in order to see if devices are being used, and how often. Still, one would not know how the devices are actually being used in practice, for instance, they could just be moved around for the purpose of cleaning. SMEs are wary of sharing data with other commercial parties about the use of their devices, which is a risk if the data are clustered in one file produced by the RTLS. Furthermore, there are concerns about disregard and carelessness, and care professionals may use the RTLS solution as a backup, which is an excuse for poor work routines.

“Some nurses may develop sloppy routines, as they might think that technology will compensate for that.”[SME6]

4.2. Sense of Responsibility

The main responsibility that informal carers experience is related to “being there” for the resident they are informal carer of.

“They are our parents, and they have always taken care of us. Now they need us.”[REL1]

This responsibility results in the search for personal belongings, such as jewelry, necklaces, and wheeled walkers. Informal carers expressed that data of the RTLS solution should not be visible outside of the nursing home. They stated that the responsibility for, as well as access to the data lies with the care professional of the nursing home.

“I don’t want to have any responsibility; it is part of the work flow of the nursing home organisation.”[REL4]

Professional carers experience a large responsibility concerning retrieving missing items. As they are responsible for the sense of well-being of the residents, care professionals consider retrieving missing personal belongings of the resident as a self-evident part of their responsibilities. Professional carers express a different level of responsibility depending on who lost the missing item, for instance, if the lost items belongs to a person with dementia, or if the item was lost by a colleague with poor work routines. An RTLS solution, however, is indiscriminate of the reason or person who lost or misplaced an item.

“Well, I do think it matters. I mean, of course you’ll start searching, and you want to get it back, and you will call your colleagues, but once you have searched for two hours without success, then that’s it. They’d better arrange an area where people have to return the devices to.”[CP1]

The sense of responsibility mainly involves putting out assistive devices for the next user. This is considered as a mutual responsibility. In case an assistive device is not put out in time––or is missing––care professionals do not consider it as disregard, but as an incident due to the hectic circumstances in care. There is no mutual annoyance or frustration for not putting out an assistive device or not knowing where it is. The team of care professionals feels responsible for retrieving missing items. An e-mail can be sent to inquire possibilities where to find missing items. Borrowing assistive devices (such as posey beds) does not occur that often, but puts a strong sense of responsibility onto professional carers.

“Some of the assistive devices are very expensive, and you don’t want to lose them. It is not like it should be done the proper way.”[CP4]

Most participants of the representatives of the SMEs and research group do not feel responsible for the privacy of the care professionals and residents of the nursing homes. While they may disagree with written standards and legislation, these documents supports a straightforward design and implementation of RTLS technologies in practice. For instance, a supplier may take care of anonymity of data as part of adhering to a standard. However, there are boundaries to the responsibilities for the supplier.

“What the care professional eventually does with [the RTLS], is his or her own concern.”[SME2]

Suppliers do feel responsible for the protection of data within the software they supply. Although this responsibility declines once data arrives at the workplace, security inside the data collection is considered as a high responsibility. In case of medical devices, personal data can be used and connected for medical predictive purposes. When suppliers make sure that data are encrypted as anonymous numbers, the care professional has to be able to connect and translate numbers to patients. The current discussion also involves hospitals, who guarantee anonymity of data within the building. Once care organisations outside the hospital connect those data to products, patients, personnel, and more, it is questionable whether this is done carefully. Examples are known of the loss of confidential data by care professionals, for which suppliers will not be responsible and cannot be made accountable for.

“We cannot be held accountable for the use of technology in hospitals and nursing homes. We just have to make sure the design and installation is done correctly.”[SME4]

4.3. Impact of RTLS on the Perception Of Space

Informal carers do not experience any impact on the perception of the built environment and the space. There are critical remarks about the residents and whether they truly understand what the system is about. If the system is clearly visible, participants believe that they will not experience any hindrance, even when sounds are produced by the RTLS solutions. Cameras are seen as a different league, and live imaging is not acceptable. Tracking devices are seen as more distant and less invasive as tracking people and observing emotions.

“Out of sight, out of mind. The system is not like a set of cameras producing clear images.”[REL1]

Professional carers would not perceive their work environment as any different when the devices they use are being monitored in terms of their location.

“Why would I change my work place if the items I use are being tracked by a system that logs data?”[CP2]

One of the care professionals shares her worries about the impact on the privacy, especially about being traced herself. But the system would not be able to change the way items that are owned by the nursing home are being treated. When tracing items concerns the personal belongings of residents, the care professionals speak of ethical dilemmas, as residents have a very limited awareness that their belongings are connected to an RTLS solution. Residents may not be able to make a well-informed choice to participate. In that case, the safety and well-being of a resident should be improved by participating in the RTLS project. The design of the system may also have an impact on the well-being of residents, for instance, when lights flash or sounds are heard and may lead to fear, irritation or anxiety.

“People do not know that their stuff is connected to a system. Maybe, they have never given permission.”[CP4]

The representatives of the SMEs and research group see no reasons to believe that the RTLS solution influences the perception of the nursing home environment.

4.4. Impact of RTLS on the Sense of Safety and Security

Informal carers and residents do not want external stakeholders to be able to access the RTLS solution and its data. Only care professionals of a given nursing home location should be given access, according to this group. The trust in the security of the RTLS solution and the underlying technology plays a role, for instance, the potential for hacking such a system.

“People won’t notice that assistive devices are being monitored. But companies should not have access to data, and no-one should be able to hack the system.”[REL1]

There is no wish to access the data from their own home, to check where items are positioned. People simply do not want to have access to all kinds of data just for the sake of having data available. Informal carers already experience a large burden, and do not wish for more data to take their time and attention.

“I am already way too busy taking care of things. I don’t want any additional tasks.”[REL3]

Professional carers worry most about the security and safety of the residents, and carers relate and compare new technologies with present experiences with exiting sensors in beds. Privacy of the resident is exchanged for an improved security situation. Losing a wheeled walker, for instance, when it is taken by another resident, really hampers the sense of security and freedom of the resident. Safety and security are seen as basic conditions that need to be guaranteed by the nursing home organisation, which can lead to an improved well-being and sense of self-value. Losing items leads to a loss of quality of life, as it may hamper one’s participation. When introducing RTLS solutions, the implementation of such a system needs to be continuously monitored and evaluated by a multidisciplinary group of stakeholders, including representatives of the resident group, in order to improve trust in the system and to see if the system provides an acceptable solution to an actual problem.

“Technology is nice to have. But it needs to be up for discussion and evaluation by all people who use it.”[CP1]

Professional carers express their concerns regarding privacy, security as well as possibilities of technology. While a professional carer may be able to understand privacy laws, residents or informal carers may have difficulty in getting informed. In addition, care professionals doubt whether it is the consumer’s responsibility or that of the companies to provide information about potential risks.

“We are here to safeguard the interests of our residents, also when it comes to the use of technology.”[CP3]

The representatives of the SMEs and research group see safety and security directly connected to privacy. While privacy can increase one’s safety and security, it may also harm one’s security in some ways. One example is the use of data by the government in order to solve crimes, which illustrates the ethical debate between the loss of privacy on the one hand (namely that of a criminal) and increased sense of safety and security in the community. In the context of nursing home care, the constant monitoring of devices may lead to a breach in privacy on the one hand as it provides information about the use of items, and on the other hand it may provide a false sense of safety and security as the movement of a wheeled walker may be misinterpreted as a particular resident walking around. Representatives of the SMEs and research group consider safety and security of residents as more important than privacy, but less important than efficiency. For instance, the search for a wandering resident supported by RTLS is accepted, despite the loss of privacy, for efficiency reasons. In the end, the discussion on what is acceptable should be held with a multidisciplinary group of stakeholders in the nursing home that uses RTLS technologies.

“Efficiency, privacy, better healthcare services… the discussion should be held in an integrated manner. I don’t know who is going to make the final decision on what is best.”[RES2]

4.5. Results in Brief

Care professionals see advantages in tracing everyday assistive devices and keys, for instance, in the reduction of time used for searching. The time gained should not lead to a loss of privacy for residents. Care professionals do not foresee a change in daily roles and attitudes when using smart technologies, but have a critical view on new technologies in general, which in their view “should never be harmful”. They feel a joint responsibility for retrieving lost items.

Relatives and residents do not experience much hindrance from care professionals looking for items. Retrieving items fast may contribute to fewer moments of stress and panic for the residents. Taking away a burden from the care professionals is seen as a welcome benefit. There are fears for the integrity of an RTLS and the security of data. No change in roles and attitudes is foreseen. It is widely expected that the RTLS are only used in cases of emergency and not 24-7. The research and SME group see potential for the use of RTLS in the gathering of data and optimisation of asset management and maintenance.

Ethics and regulations should not be too restrictive regarding the type of data that are to be gathered, according to SMEs. Moreover, care professionals may improve their work hygiene when items are being monitored, thereby reducing the amount of items that get lost. The principle responsibility for ethics and privacy is placed at the nursing home organisation itself, SMEs will make sure the quality of the RTLS is in line with standards.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, the ethical issues concerning RTLS for assistive technologies in nursing homes were explored. Focus groups were organised with three groups of participants to discuss the conditions for implementation and its implications to the context of aged care. The knowledge gained in the sessions helps develop the new RTLS solution within a framework of ethics and best practice in aged-care, which encompasses more than just privacy, but also includes meaningfulness.

Similar to Leikas and Kulju [10], it was found that the three groups of stakeholders weighed ethical principles and values differently. Similarly, one of the most important issues is the right balance between value for the end-user (resident) and the value for care professionals. It is about simultaneously pursuing four dimensions of performance: improving the health of populations, enhancing the experience of care, and reducing the per capita cost of health care [23] and improving work satisfaction are some of the goals in healthcare [23]. If the gap continues to widen between society’s expectations for primary care and primary care’s available resources, the feelings of betrayal and the wearing down from daily stress voiced by primary care practitioners will grow [23] (p. 575). Technology can be of help in making this fourth dimension happen. The groups raised various ethical dilemmas in the implementation of RTLS, but there was a constant mix of tracking goods on the one hand, and people on the other. The current project deals with goods, assistive devices in particular. As in the study by Leikas and Kulju [10], participants did not extensively explicate concrete ethical issues. This may, in turn, require further research to reveal tacit ethical understanding of the various groups of participants. One very obvious ethical concern that was hardly shared in the study was informed consent [10,28,29,30], for instance, in relation to tagging personal belongings of residents. Giving informed consent by older people with dementia may be challenging, or in late-stage dementia, rather impossible. This aspect was out of the focus of the professional stakeholders, which had a major focus on privacy in general. Aspects like autonomy, control and freedom were raised in all three groups. Nursing home residents and staff should be able to express a reluctance to participate in such RTLS projects if they do not wish to join. At the same time, new technologies may support daily living or work activities, and improve the degree of freedom as people do no longer have to worry about items that went missing or were misplaced. Still, the balance between sacrificing some of your privacy in order to be able to retrieve missing goods may need an individual discussion for every end-user of an RTLS solution.

One of the benefits of the current structure of the research was the heterogeneity of the groups, which led to a richness of data and perspectives. At the same time, if the three groups vary too much in terms of gender, age and technology experience, it may lead to skewed results which are hard to compare in terms of applicability. Therefore, future research should also include more residents, even though it may be hard to include older people with dementia in rather abstract and in-depth group discussions. In addition, a separate group of representatives of SMEs on the one hand and researcher on the other hand could have led to a better distinction between views of the two groups.

Care professionals stress the convenience of being able to retrieve lost and misplaced items, and make an inventory of the assistive devices used. They estimate a 15 minute time gain per shift per member of staff. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance that the interface of an RTLS solution is well-designed for quick use by the end-users, for instance, by applying a tablet computer or smart phone. There are additional design specifications that need to be considered, such as sound and alarm-free technology which is not intrusive to the residents, and that the use of video images is off limits. It should, therefore, not physically look like a camera system, because it may else be perceived or experienced as one and as a consequence, people may start behaving like a camera is present (withdrawal or aggressive behaviours).

The implementation of RTLS solutions may impact the responsibilities on the work floor and the sense of safety and security. According to the focus groups, there should be a joint responsibility for the operation of the RTLS technology, in which an open dialogue between the stakeholders is considered to be an essential element in acceptance and use of the system. In terms of safety and security, privacy may be offered in favour of an increased sense of security. Although there are no major conflicts between the focus groups, there were some differences in insights concerning the implementation of RTLS in practice. For instance, there were reservations expressed about nursing home staff having to learn about the technology, about less regard because of more dependence on technology, about the privacy of residents, and the potential disturbances of nursing home residents due to the design of technology. In practice, these differences in views should ideally be overcome by having discussions in multi-stakeholder groups. In addition, there was some discussion on the definition of safety and security, and which assistive devices can be qualified as having an impact on safety and security of the resident. Therefore, additional analyses are needed with professional carers, relatives and the residents to make an overview of indispensable assistive technologies that cannot be missed or are essential to safety and security in the nursing home context. According to the participants, there is no wish to access the data from the own home, to check where items are positioned. Therefore, RTLS will have a limited applicability and use in the private real estate sector, prepared especially for the needs of older people wishing to age-in-place [42,43]. Another recommendation for future work is a comparison between the ethical aspects of implementing RTLS with other emerging medical digital technologies and mobile health solutions [44]. A final recommendation for future research would be to see if the managerial culture, service level agreement, or public versus private character of a nursing home organisation would impact the views of the various stakeholders.

In terms of the implementation of RTLS, the acceptance of these technologies can be enhanced if stakeholders are actively informed about new technologies, when worries and objections are taken away through a mutual dialogue, and by the provision of sufficient training and coaching during a prolonged implementation period.

Acknowledgments

The RAAK (Regional Attention and Action for Knowledge circulation) scheme, which is managed by the Foundation Innovation Alliance (SIA—Stichting Innovatie Alliantie) with funding from the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW), is thanked for their financial support (SIA project number 2015-02-24M, Project SCHAT—Smart Care Homes and Assistive Technologies). RAAK aims to improve knowledge exchange between SMEs and Universities of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands. We would like to thank all participants of the sessions at BrabantZorg and Fontys University of Applied Sciences for their willingness to take part in the focus group sessions. Josta Augenbroe, Lucy van den Bosch, Peter Verkuijlen, and Margreet Vossen are thanked for their assistance.

Author Contributions

J. van Hoof is the co-project leader of the project, drafted the manuscript and took part in the field work. J. Verboor analysed the data and conducted the field work. C.E. Oude Weernink took part in the field work. A.A.G. Sponselee is co-project leader and drafted the manuscript. Y. van Zaalen drafted the manuscript’s theoretical section and helped with the interpretation of data. J.A. Sturm, J.K. Kazak, and G.M.J. Govers drafted and critically reviewed the manuscript and provided input for the theoretical basis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding organisation had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Van Hoof, J.; Douven, B.; Janssen, B.M.; Bosems, W.P.H.; Oude Weernink, C.E.; Vossen, M.B. Losing items in the psychogeriatric nursing home: The perspective of residents and their informal caregivers. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oude Weernink, C.E.; van Hoof, J.; Felix, E.; Verkuijlen, P.J.E.M.; Dierick-van Daele, A.T.M.; Kazak, J.K. Real-time location systems in nursing homes: State of the art and future applications. J. Enabling Technol. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Oude Weernink, C.E.; Sweegers, L.; Relou, L.; van der Zijpp, T.J.; van Hoof, J. Lost and found: Identifying problems and technological opportunities related to lost and misplaced items in nursing homes through participatory design research. Technol. Disabil. 2017, 29, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krohn, R. The optimal RTLS solution for hospitals. Breaking through a complex environment. J. Healthc. Inf. Manag. 2008, 22, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malik, A. RTLS for Dummies; Wiley Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel Boulos, M.N.; Berry, G. Real-time locating systems (RTLS) in healthcare: A condensed primer. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2012, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, J.A.; Monahan, T. Evaluation of real-time location systems in their hospital contexts. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2012, 81, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbers, C.W.J.M.; van Hoof, J.; Oude Weernink, C.E. Privacyaspecten van track-en-tracetechnologie in de zorg. Priv. Inf. 2017, 20, 24–32. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Ebbers, C.W.J.M.; van Hoof, J.; Oude Weernink, C.E. De toepassing van track-en-tracetechnologie in de zorg (2). Priv. Inf. 2017, 20, 256–263. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Leikas, J.; Kulju, M. Ethical consideration of home monitoring technology: A qualitative focus group study. Gerontechnology 2018, 17, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, R.; Hope, T.; Wilkinson, J. Tracking patients who wander: Ethics and technology. Lancet 1994, 343, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørneby, S.; Topo, P.; Holthe, T. (Eds.) Technology, Ethics and Dementia: A Guidebook on How to Apply Technology in Dementia Care; Norwegian Centre for Dementia Research: Oslo, Norway, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J.C.; Louw, S.J. Electronic tagging of people with dementia who wander. Br. Med. J. 2002, 325, 847–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt, B. Ethics of the health-related internet of things: A narrative review. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2017, 19, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt, B. Designing the health-related internet of things: Ethical principles and guidelines. Information 2017, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, M.; Brittain, K. Technology and trust: Older people’s perspectives of a home monitoring system [Technologie et confiance: Le point de vue des personnes âgées sur un système de télésurveillance à domicile]. Retraite Soc. 2016, 75, 47–72. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Childress, J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, M. Ethics: Harm in the emergency department—Ethical drivers for change. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, W. Time for leadership in teaching about care of chronic illness. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 570–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rietveld, P.; Hensher, D.A.; Button, K.J. Winners and losers in Transport Policy: On Efficiency, Equity, and Compensation. In Handbook of Transport and the Environment; Hensher, D.A., Button, K.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 585–602. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zaalen-op’t Hof, Y.; McDonnell-Naughton, M.; Mikołajczyk, B.; Buttigieg, S.C.; del Carmen Requena, M.; Holtkamp, F.C. Technology implementation in delivery of healthcare to older people: How can the least voiced in society be heard? J. Enabling Technol. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Thematic Study on the Realization of the Right to Health of Older Persons by the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health, Anand Grover; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaertner, J.; Vent, J.; Greinwald, R.; Rothschild, M.A.; Ostgathe, C.; Kessel, R.; Voltz, R. Denying a patient’s final will: Public safety vs. medical confidentiality and patient autonomy. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 42, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Hoven, J. Moral values, design and ICT. J. Hum. 2005, 23, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.M.; Gruskin, S.; Subramanian, S.V.; Heymann, J. Emerging health disparities in Botswana: Examining the situation of orphans during the AIDS epidemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 2476–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musschenga, B.; Schuijer, M.E.; Verstegen, G.; Vonk, M.; Dorrestijn, S.; Kalis, A. Praktische problemen in filosofisch perspectief. Filos. Prakt. 2016, 37, 48–56. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof, J.; Kort, H.S.M.; Markopoulos, P.; Soede, M. Ambient intelligence, ethics, and privacy. Gerontechnology 2007, 6, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeijer, A.R.; Depla, M.F.; Frederiks, B.J.; Hertogh, C.M. The experiences of people with dementia and intellectual disabilities with surveillance technologies in residential care. Nurs. Ethics 2015, 22, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, M. Technology is the shape of the future. J. Dement. Care 1995, 3, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- van Berlo, A. Ethics in domotics. Gerontechnology 2005, 3, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; Wouters, E.J.M. Ethische aspecten bij het gebruik van toezichthoudende domotica. In Het Verpleeghuis van de Toekomst is (een) Thuis; van Hoof, J., Wouters, E.J.M., Eds.; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 73–74. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk, M. (Over)behandelen van kwetsbare ouderen. Een ethische benadering. Bijblijven 2016, 32, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Have, H.A.M.J.; ter Meulen, R.H.J.; van Leeuwen, E. Medische Ethiek, 3rd ed.; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten, The Netherlands, 2009. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof, J.; Dooremalen, A.M.C.; Wetzels, M.H.; Weffers, H.T.G.; Wouters, E.J.M. Exploring technological and architectural solutions for nursing home residents, care professionals and technical staff: Focus groups with professional stakeholders. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Technol. 2014, 1, 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. Br. Med. J. 1995, 311, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects; Adopted by the 18th WMA General Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, 1964 and Last Amended by the 59th WMA General Assembly, Seoul, Korea, 1975; World Medical Association: Ferney-Voltaire, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof, J.; Wouters, E.J.M. Zorgdomotica; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten, The Netherlands, 2012. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Timmer, S. Ehealth in de Langdurige Zorg. De Praktijk van de Ouderen-en Gehandicaptenzorg, 2nd ed.; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten, The Netherlands, 2015. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Kazak, J.; van Hoof, J.; Świąder, M.; Szewrański, S. Real Estate for the Ageing Society—The Perspective of a New Market. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2017, 25, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerenfijn, P.; Kazak, J.K.; Schellen, L.; van Hoof, J. A multi-case study of innovations in energy performance of social housing for older adults in the Netherlands. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersinga, J. Chapter 13 Regulation of Medical Digital Technologies. In Mobile e-Health, Human–Computer Interaction Series; Marston, H.R., Freeman, S., Musslewhite, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 277–295. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).