On the Predictability of Classical Propositional Logic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

NP.

NP.

- (i) it is weaker than classical entailment;

- (ii) it is based on informational notions; and

- (iii) it treats as “uninformative” exactly those inferences that are “analytical” in the strict informational sense, that is, which do not appeal to virtual information.

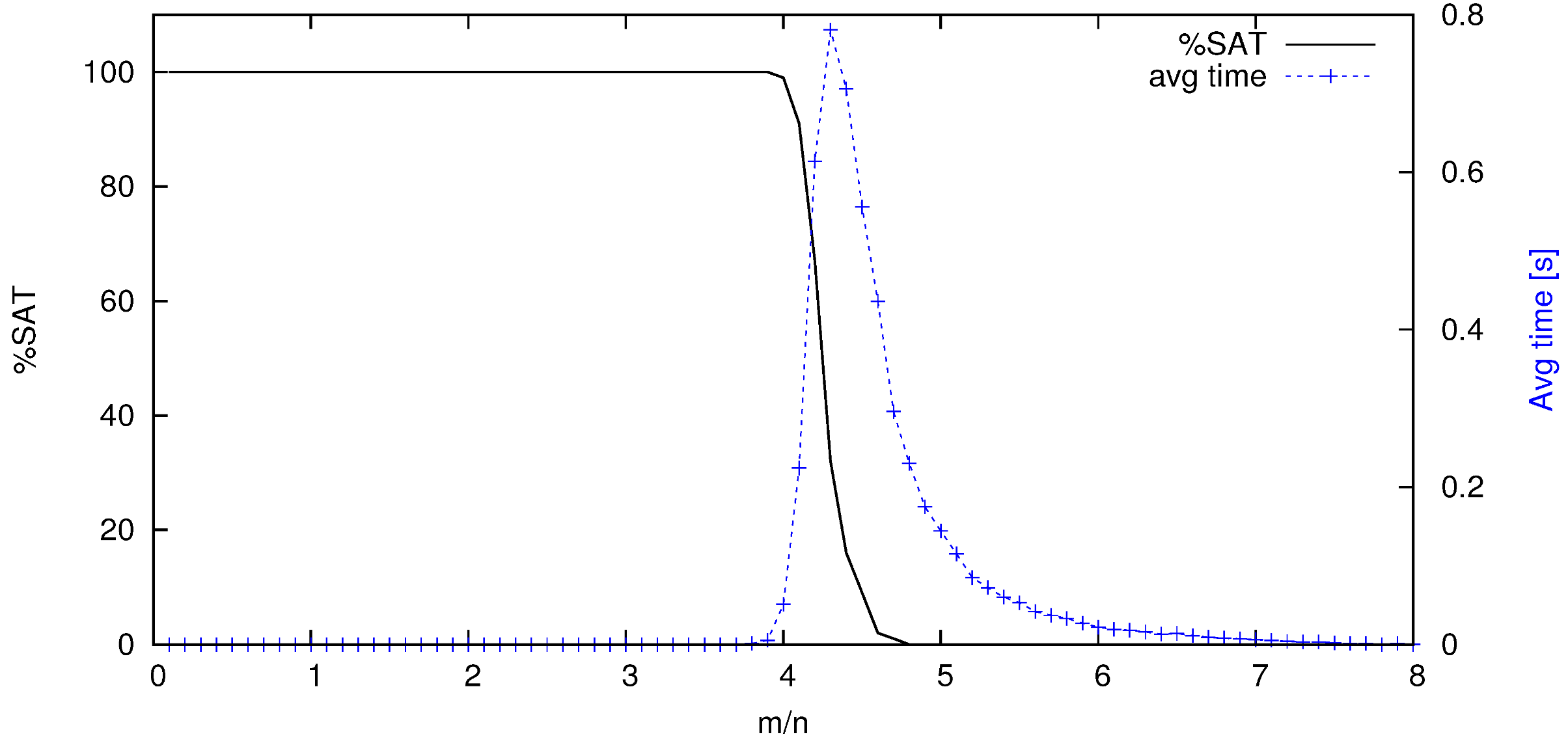

2. SAT Solvers and Phase Transition

3. The Runtime Distribution of a SAT Solver

3.1. Experiments and Results

- All clauses were generated with exactly three literals (k =3);

- The number of atoms (n) ranged in 50, 100, 200 and 300;

- For each value of n, the number of clauses (m) varied such that m/n resulted in 1, 2, 3, 4, 4.3 (at the phase transition point ), 5, 6, 7 and 8.

- n = 100,

= 4.3;

- n = 200,

= 4.3, 5, 6, 7, 8; and

- n = 300,

= 4.3, 5, 6, 7, 8.

- Resulting in a total of 550.000 instances = 50.000 (problems) × 11 (cases)

3.2. Summary of Experiments

. So, it was necessary to generate more samples resulting a total amounting to about 1 million (910,000) instances.

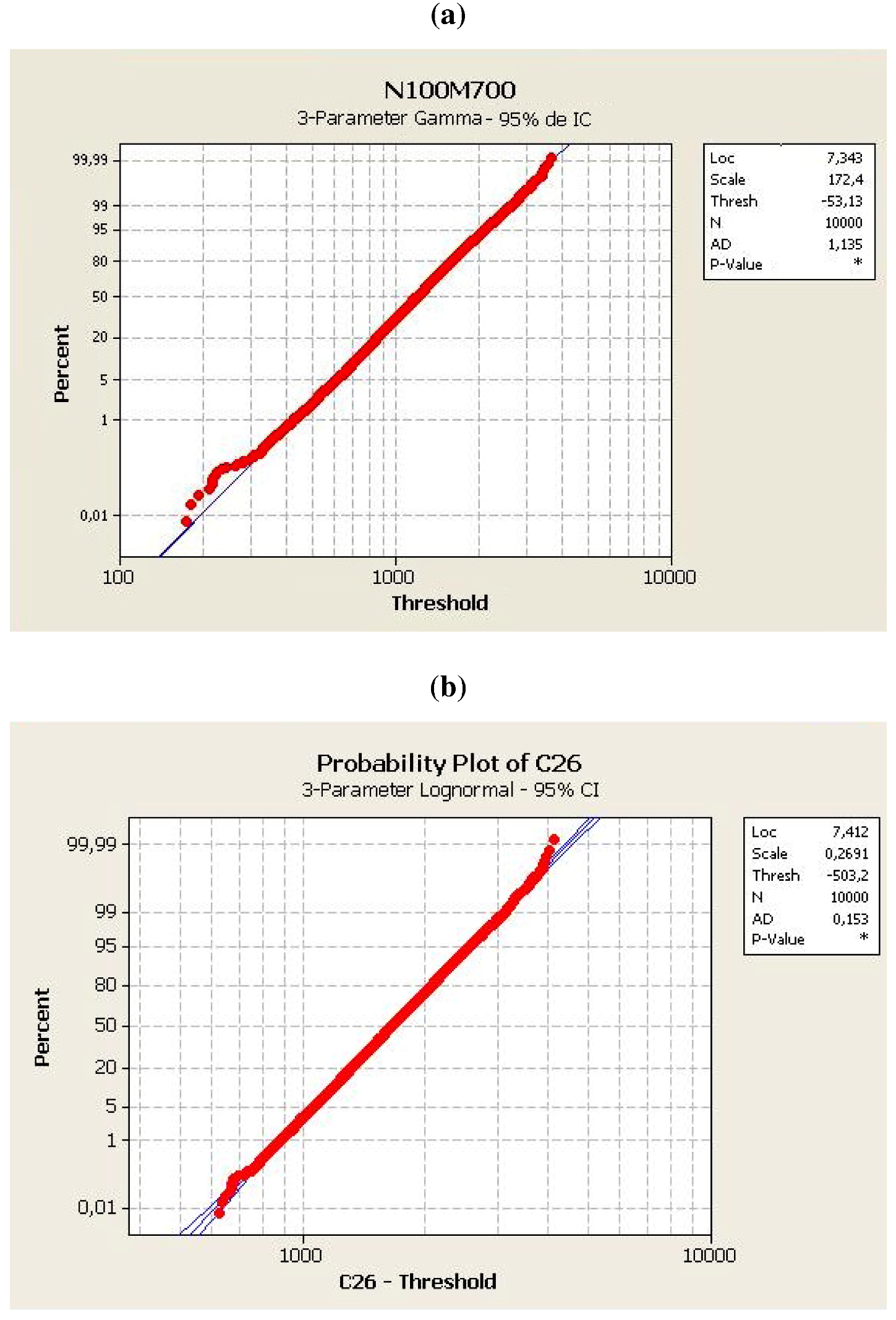

. So, it was necessary to generate more samples resulting a total amounting to about 1 million (910,000) instances. 3.3. Compliance with a Known Distribution

For a given set of data and distribution, the lower the statistical distribution for a better fits the data.

- AD The probability of rejecting the distribution in question

- N Number of samples

- P-value Descriptive level

. The cases were:

. The cases were:  ≤ 2 In these cases, zChaff behaves as a discrete distribution of unknown origin where the tails have similar lengths. As an example we present the Figure 2.

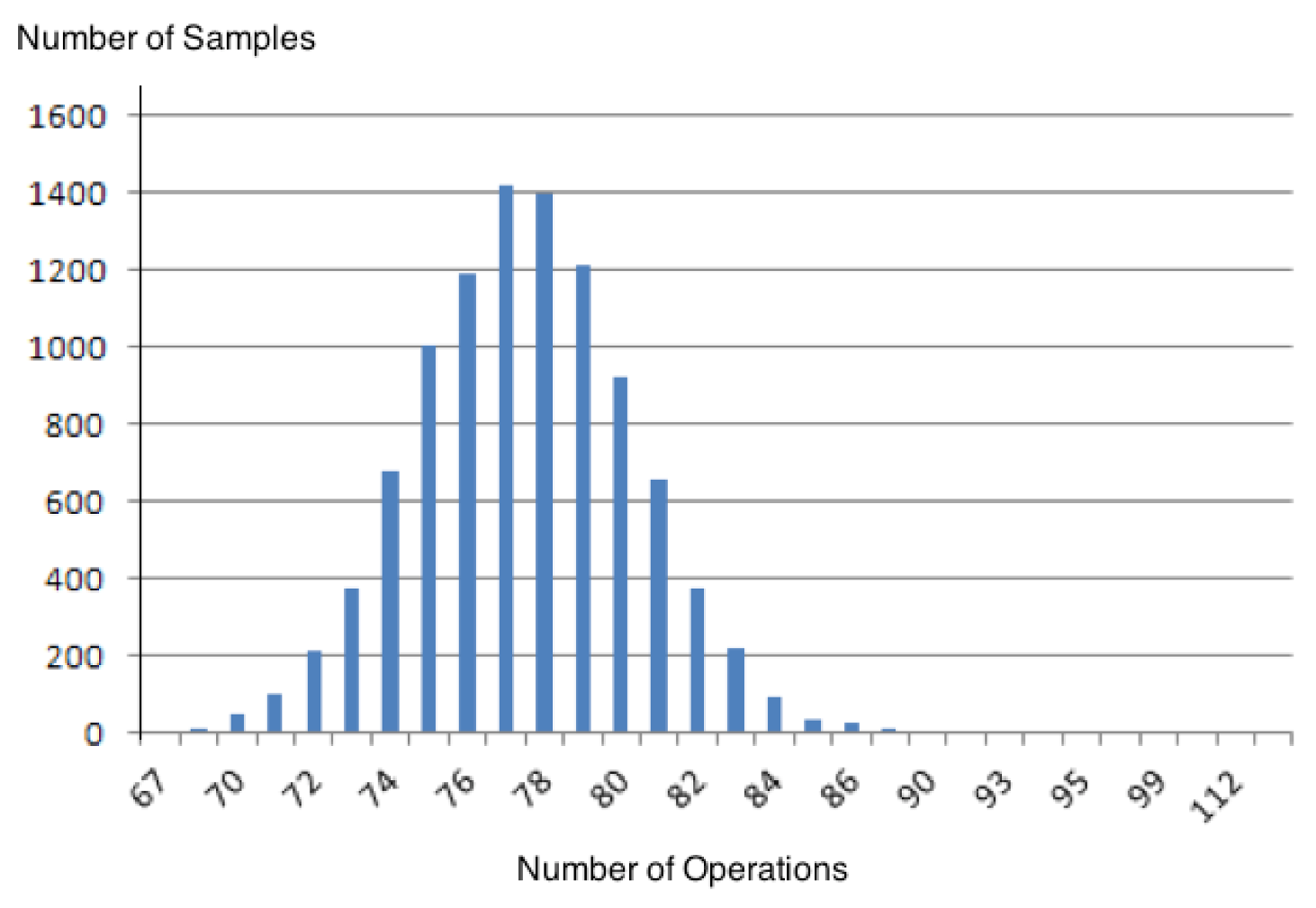

≤ 2 In these cases, zChaff behaves as a discrete distribution of unknown origin where the tails have similar lengths. As an example we present the Figure 2.  = 1

= 1

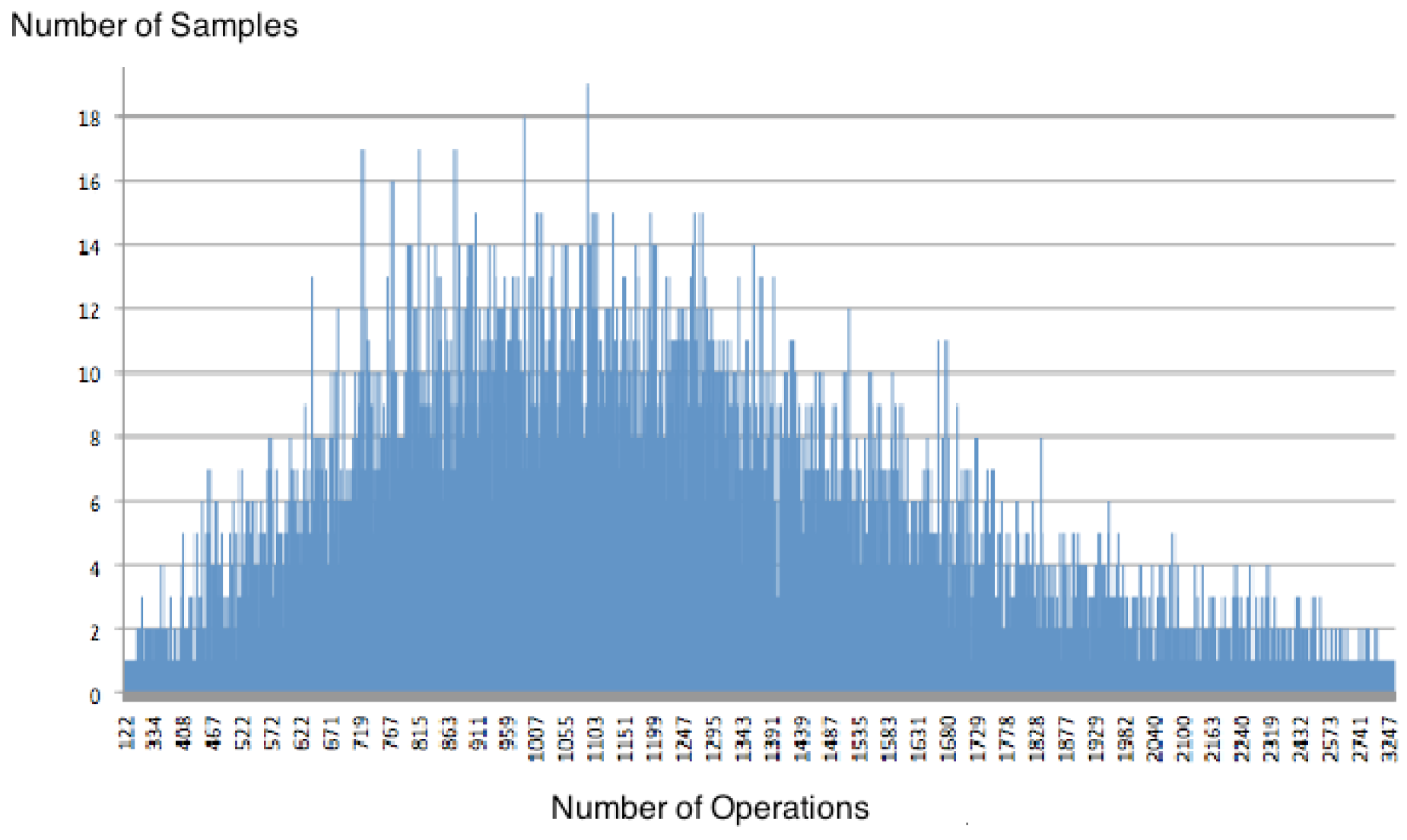

=3 As the ratio

=3 As the ratio  increases, the tail of the distribution begins to extend to the right and also increases the frequency of events. The distance between points decreases, approaching a continuous distribution. Figure 3 is an example for n = 50 and m = 150.

increases, the tail of the distribution begins to extend to the right and also increases the frequency of events. The distance between points decreases, approaching a continuous distribution. Figure 3 is an example for n = 50 and m = 150.  = 3.

= 3.

= 4, a graphical distribution resembles an exponential shape. Figure 4 displays this behaviour for n = 50 and m = 200.

= 4, a graphical distribution resembles an exponential shape. Figure 4 displays this behaviour for n = 50 and m = 200.  = 4.

= 4.

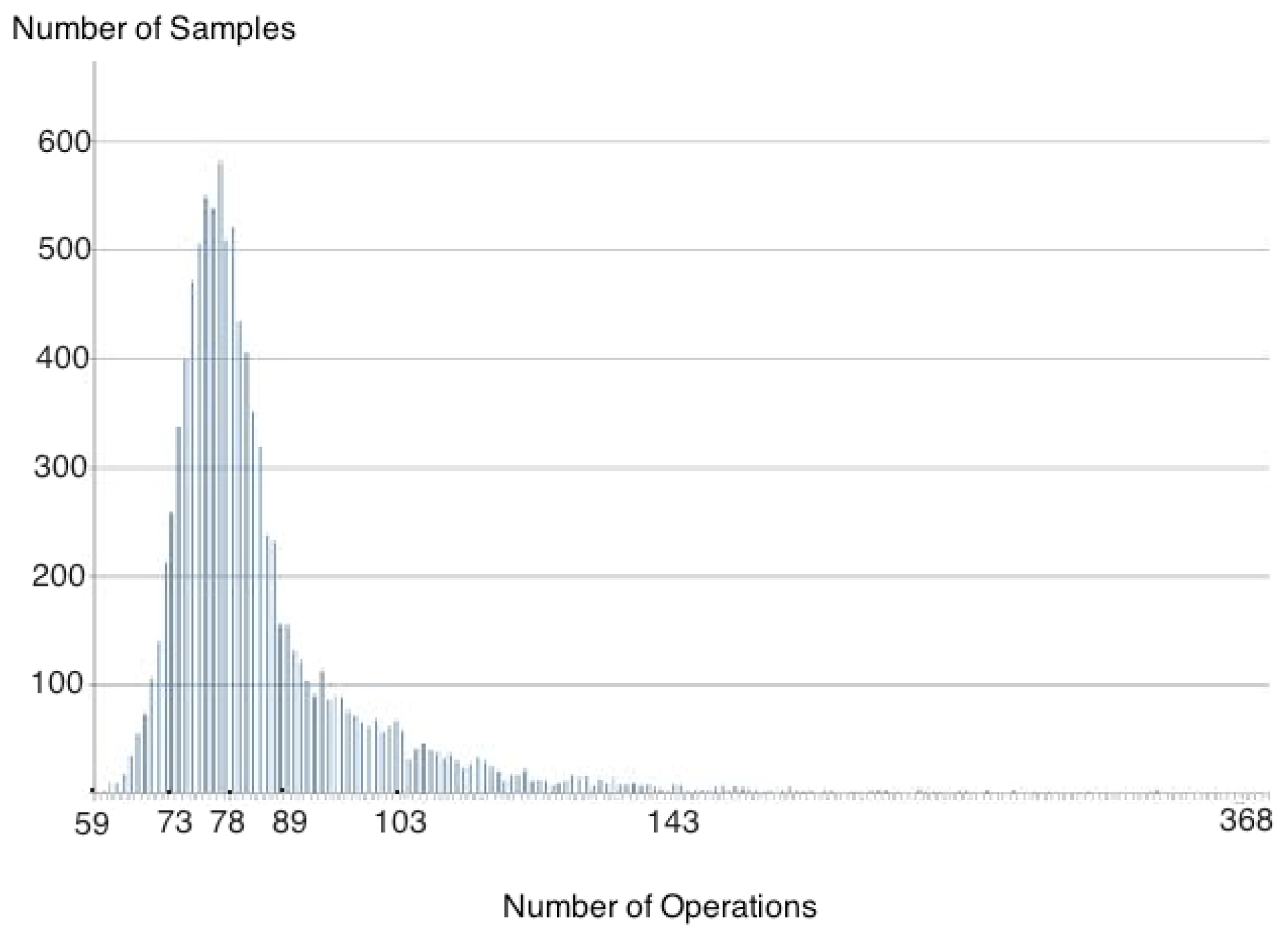

≥ 6 For cases with values of

≥ 6 For cases with values of  = 6, 7 and 8, zChaff behaviour approximates a log-normal distribution, as confirmed by GoF tests, as illustrated in Figure 5.

= 6, 7 and 8, zChaff behaviour approximates a log-normal distribution, as confirmed by GoF tests, as illustrated in Figure 5.  = 7.

= 7.

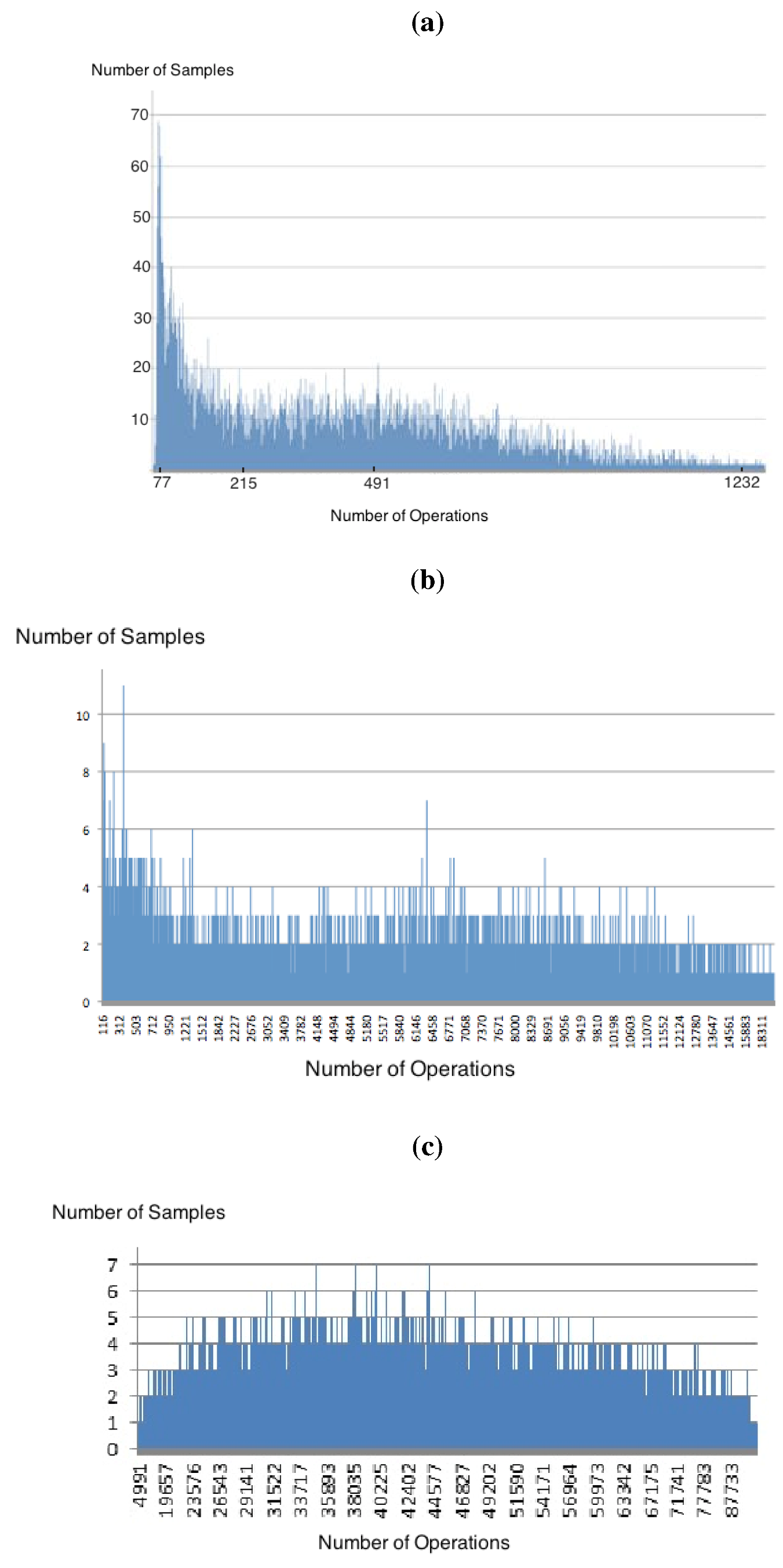

3.4. The Inconclusive Cases

= 4.3) and points with values of

= 4.3) and points with values of  slightly higher, such as

slightly higher, such as  = 5, the data distribution did not fit any of the patterns listed above. Furthermore, the shape of the data distribution is not preserved for different values of n, a fact that is also very different from the well behaved cases “away from the transition point”.

= 5, the data distribution did not fit any of the patterns listed above. Furthermore, the shape of the data distribution is not preserved for different values of n, a fact that is also very different from the well behaved cases “away from the transition point”.  = 4.3 ). (a) Distribution found for n = 50 and m = 215,

= 4.3 ). (a) Distribution found for n = 50 and m = 215,  = 4.3; (b) Distribution found for n = 100 and m = 430,

= 4.3; (b) Distribution found for n = 100 and m = 430,  = 4.3; (c) Distribution found for n = 200 and m = 860,

= 4.3; (c) Distribution found for n = 200 and m = 860,  = 4.3.

= 4.3.

= 4.3 ). (a) Distribution found for n = 50 and m = 215,

= 4.3 ). (a) Distribution found for n = 50 and m = 215,  = 4.3; (b) Distribution found for n = 100 and m = 430,

= 4.3; (b) Distribution found for n = 100 and m = 430,  = 4.3; (c) Distribution found for n = 200 and m = 860,

= 4.3; (c) Distribution found for n = 200 and m = 860,  = 4.3.

= 4.3.

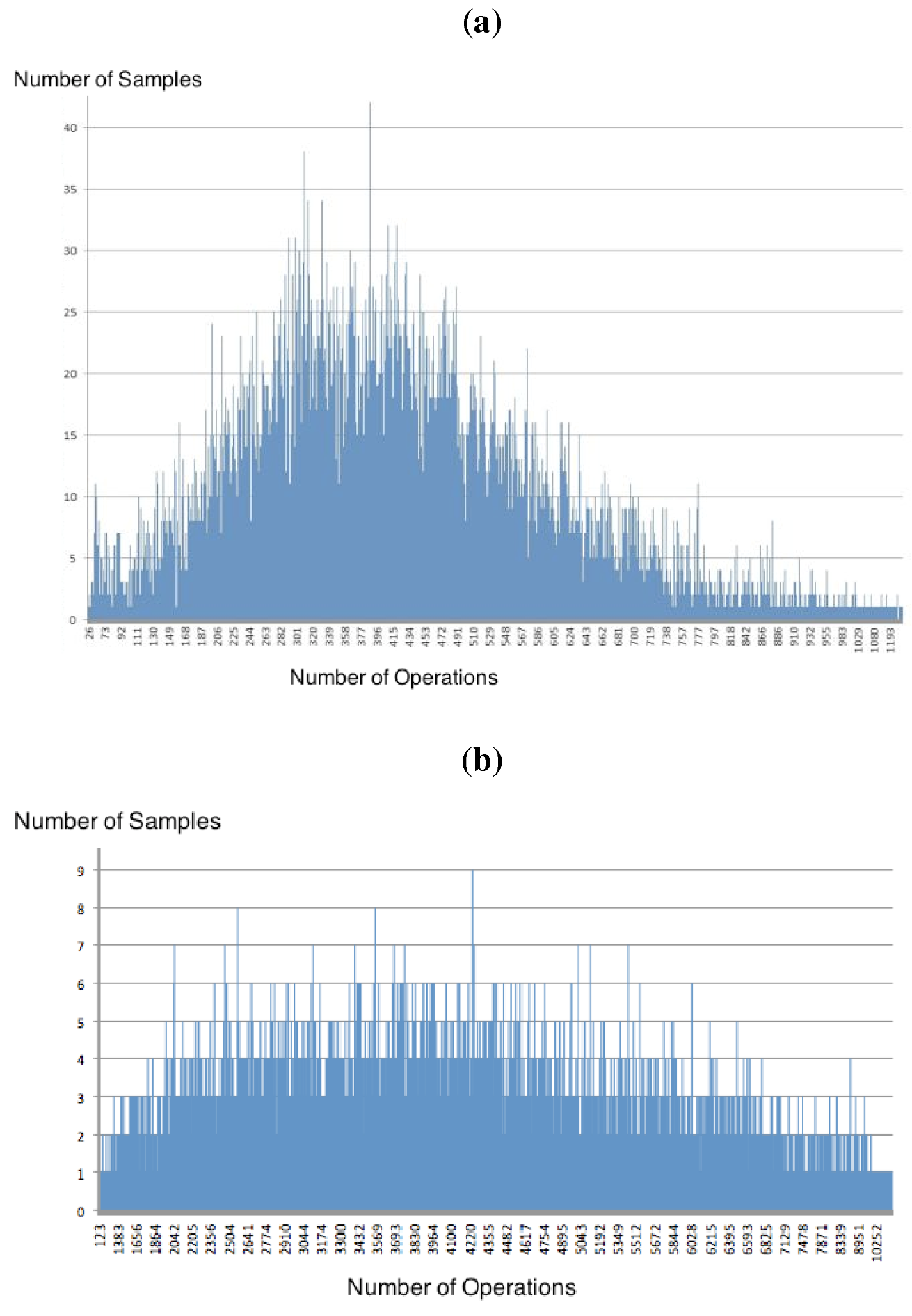

= 4, but the non-uniform behaviour persists a little bit after the phase-transition point, when

= 4, but the non-uniform behaviour persists a little bit after the phase-transition point, when  = 5, as illustrated in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

= 5, as illustrated in Figure 8 and Figure 9. = 5). (a) Distribution found for n = 50 and m = 250,

= 5). (a) Distribution found for n = 50 and m = 250,  = 5; (b) Distribution found for n = 100 and m = 500,

= 5; (b) Distribution found for n = 100 and m = 500,  = 5.

= 5.

= 5). (a) Distribution found for n = 50 and m = 250,

= 5). (a) Distribution found for n = 50 and m = 250,  = 5; (b) Distribution found for n = 100 and m = 500,

= 5; (b) Distribution found for n = 100 and m = 500,  = 5.

= 5.

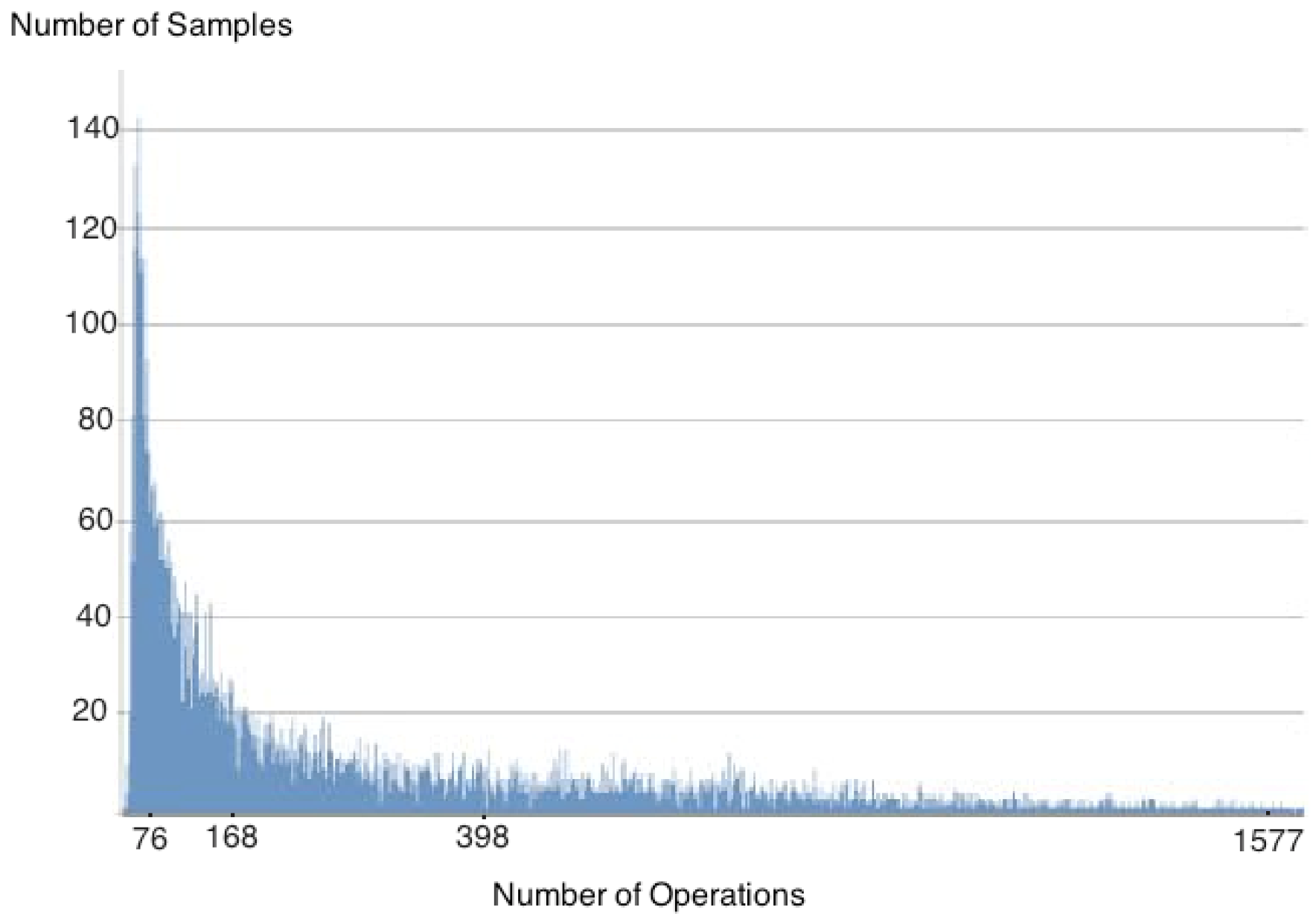

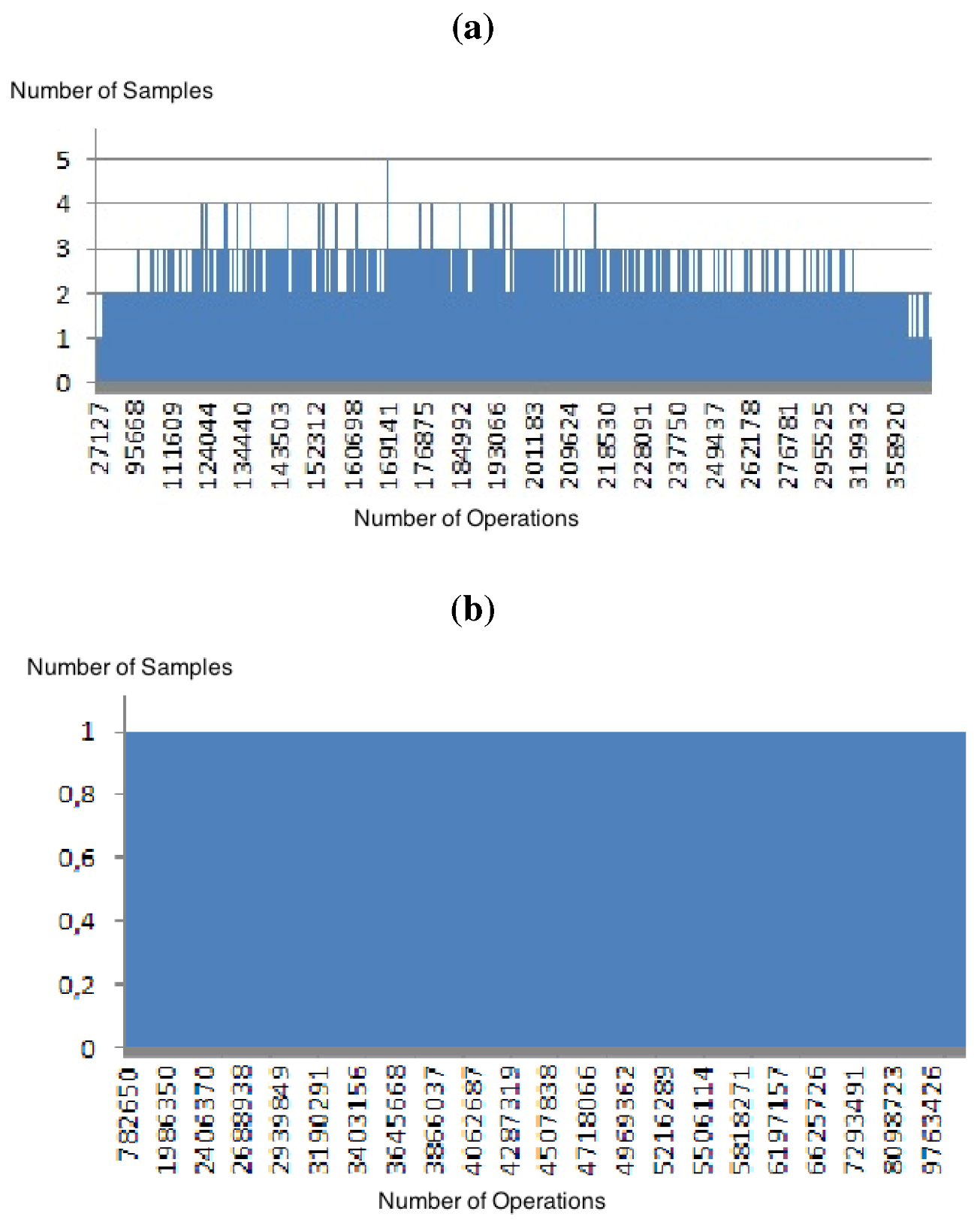

= 5 we can verify the empirical data distribution obtained when n = 50 (Figure 8a), n = 100 (Figure 8b), n = 200 (Figure 9a) and n = 300 (Figure 9b). The non-uniformity is visually apparent, and the compliance tests tell us that none of these empirical data distributions fit any of the distributions known to the tool.

= 5 we can verify the empirical data distribution obtained when n = 50 (Figure 8a), n = 100 (Figure 8b), n = 200 (Figure 9a) and n = 300 (Figure 9b). The non-uniformity is visually apparent, and the compliance tests tell us that none of these empirical data distributions fit any of the distributions known to the tool.  = 5). (a) Distribution found for n =200 and m = 1000; (b) Distribution found for n = 300 and m = 1500.

= 5). (a) Distribution found for n =200 and m = 1000; (b) Distribution found for n = 300 and m = 1500.

= 5). (a) Distribution found for n =200 and m = 1000; (b) Distribution found for n = 300 and m = 1500.

= 5). (a) Distribution found for n =200 and m = 1000; (b) Distribution found for n = 300 and m = 1500.

= 4.3 and

= 4.3 and  = 5 do not resemble each other. In fact, when n = 50, the distribution for

= 5 do not resemble each other. In fact, when n = 50, the distribution for  = 4.3 has the shape of a spiky exponential, while the distribution for

= 4.3 has the shape of a spiky exponential, while the distribution for  = 5 has the shape of a spiky, somewhat distorted normal curve. Even more disturbing is the shape of the curves for n = 300. Due to the long times involved, we did not obtain that curve in the phase transition point, but for

= 5 has the shape of a spiky, somewhat distorted normal curve. Even more disturbing is the shape of the curves for n = 300. Due to the long times involved, we did not obtain that curve in the phase transition point, but for  = 5 the distribution visually looks like a constant distribution.

= 5 the distribution visually looks like a constant distribution. 4. Analysis

| Uniform | Shape |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 2 | yes | binomial/normal |

| ∈ [3, 4] | yes | gamma |

| ∈ [4.3, 5] | no | – |

| ≥ 6 | yes | log-normal |

≤ 2 and

≤ 2 and  ≥ 6 in the following way. When

≥ 6 in the following way. When  ≤ 2, the instances are mostly satisfiable, and the solutions is “easy” in the sense that there are very few restrictions over a large number of variables, so almost any valuation satisfies the formula.

≤ 2, the instances are mostly satisfiable, and the solutions is “easy” in the sense that there are very few restrictions over a large number of variables, so almost any valuation satisfies the formula.  ≥ 6 the problems are mostly unsatisfiable and the distribution is log-normal. A log-normal distribution is a continuous probability distribution of a random variable whose logarithm is normally distributed, and it occurs when the variable can be seen as the product of many independent random variables each of which is positive [25]. We can see this behaviour occurring in the SAT context in case we have several satisfiable formulas of binomial/normal type, which are jointly unsatisfiable. The SAT instance is the union of such jointly unsatisfiable formulas, and the SAT solver tries to, independently, satisfy all such component formulas, which provides the multiplicative effect on the runtimes, and fails only when the last formula is added.

≥ 6 the problems are mostly unsatisfiable and the distribution is log-normal. A log-normal distribution is a continuous probability distribution of a random variable whose logarithm is normally distributed, and it occurs when the variable can be seen as the product of many independent random variables each of which is positive [25]. We can see this behaviour occurring in the SAT context in case we have several satisfiable formulas of binomial/normal type, which are jointly unsatisfiable. The SAT instance is the union of such jointly unsatisfiable formulas, and the SAT solver tries to, independently, satisfy all such component formulas, which provides the multiplicative effect on the runtimes, and fails only when the last formula is added.  , near the phase transition point, present a variation and a combination of these two cases. A little bit before the phase transition, most formulas are still satisfiable, but a satisfiable valuation is harder to find, so the tail of the distribution grows and the distribution is best modelled as a gamma-distribution, a distribution that usually models waiting-times.

, near the phase transition point, present a variation and a combination of these two cases. A little bit before the phase transition, most formulas are still satisfiable, but a satisfiable valuation is harder to find, so the tail of the distribution grows and the distribution is best modelled as a gamma-distribution, a distribution that usually models waiting-times. 5. Conclusions and Further Work

Acknowledgements

References and Notes

- D’Agostino, M.; Floridi, L. The enduring scandal of deduction. Is propositional logic really uninformative? Synthese 2009, 167, 271–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintikka, J. Logic, Language Games and Information. Kantian Themes in the Philosophy of Logic; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Dummett, M. The Logical Basis of Metaphysics; Duckworth: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Floridi, L. Is information meaningful data? Philos. Phenomen. Res. 2005, 70, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.A. The Complexity of Theorem-Proving Procedures. In Conference Record of Third Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC); ACM: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1971; pp. 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, C.H. Computational Complexity; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, S.; Barak, B. Computational Complexity: A Modern Approach, 1st ed; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schaerf, M.; Cadoli, M. Tractable Reasoning via Approximation. Artif. Intell. 1995, 74, 249–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, M. Anytime Families of Tractable Propositional Reasoners. In International Symposium of Artificial Intelligence and Mathematics AI/MATH-96; Fort Lauderdale: FL, USA; pp. 42–45.

- Finger, M.; Wassermann, R. Approximate and Limited Reasoning: Semantics, Proof Theory, Expressivity and Control. J. Logic Comput. 2004, 14, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, M.; Gabbay, D. Cut and Pay. J. Log. Lang. Inf. 2006, 15, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, M.; Wassermann, R. The Universe of Propositional Approximations. Theor. Comp. Sci. 2006, 355, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The international SAT Competitions web page. Available online: http://www.satcompetition.org/ (accessed on 31 December 2012).

- These very large problems arise from industrial applications or may be randomly generated.

- Gent, I.P.; Walsh, T. The SAT Phase Transition. In ECAI94—Proceedings of the Eleventh European Conference on Artificial Intelligence; John Wiley & Sons: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D.; Selman, B.; Levesque, H. Hard and Easy Distributions of SAT Problems. In AAAI92— Proceedings of the 10th National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Jose, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 459–465.

- Moskewicz, M.W.; Madigan, C.F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Malik, S. Chaff: Engineering an Efficient SAT Solver. In Proceedings of the 38th Design Automation Conference (DAC’01), as Vegas, NV, USA,, 2001; pp. 530–535.

- Goldberg, E.; Novikov, Y. Berkmin: A Fast and Robust SAT Solver. In Design Automation and Test in Europe (DATE2002); Paris, France, 2002; pp. 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Eén, N.; Sörensson, N. An Extensible SAT-solver. SAT 2003, LNCS; Springer: Portofino, Italy, 2003; Volume 2919, pp. 502–518. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: http://www.princeton.edu/∼chaff/zchaff/zchaff.64bit.2007.3.12.zip (accessed on 7 January 2013).

- Cheeseman, P.; Kanefsky, B.; Taylor, W.M. Where the really hard problems are. In 12th IJCAI; Morgan Kaufmann: Sydney, Australia, 1991; pp. 331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J. An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements; Physics-chemistry-engineering, University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Minitab. Available online: http://minitab.com (accessed on 31 December 2012).

- Reis, P.M. Analysis of Runtime Distributions in SAT solvers (in Portuguese). Master’s Thesis, Department of Computer Science, Institute of Mathematics and Statistics, University of São Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Limpert, E.; Stahel, W.A.; Abbt, M. Log-normal distributions across the sciences: Keys and clues. BioScience 2001, 51, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Finger, M.; Reis, P.M. On the Predictability of Classical Propositional Logic. Information 2013, 4, 60-74. https://doi.org/10.3390/info4010060

Finger M, Reis PM. On the Predictability of Classical Propositional Logic. Information. 2013; 4(1):60-74. https://doi.org/10.3390/info4010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleFinger, Marcelo, and Poliana M. Reis. 2013. "On the Predictability of Classical Propositional Logic" Information 4, no. 1: 60-74. https://doi.org/10.3390/info4010060

APA StyleFinger, M., & Reis, P. M. (2013). On the Predictability of Classical Propositional Logic. Information, 4(1), 60-74. https://doi.org/10.3390/info4010060