Social Engineering Attacks Using Technical Job Interviews: Real-Life Case Analysis and AI-Assisted Mitigation Proposals

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Hypothesis and Objectives

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

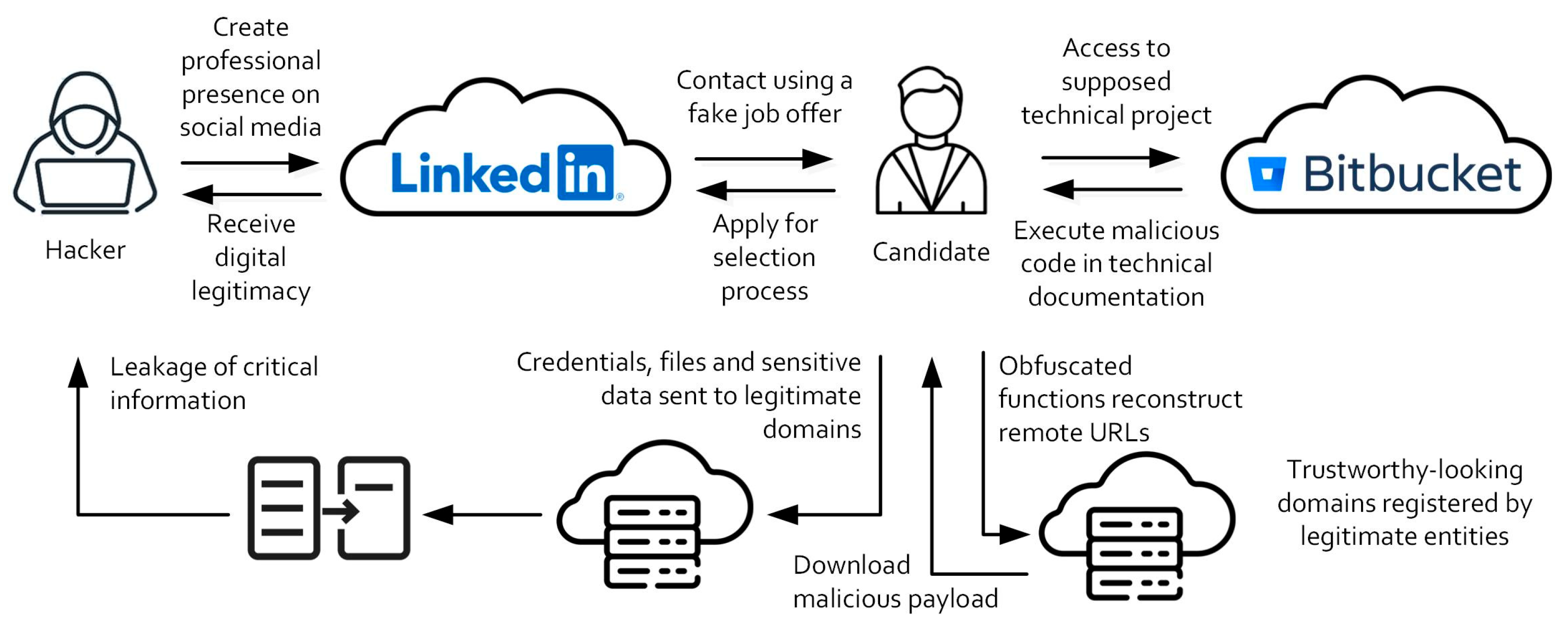

3.1. Social Engineering Attack

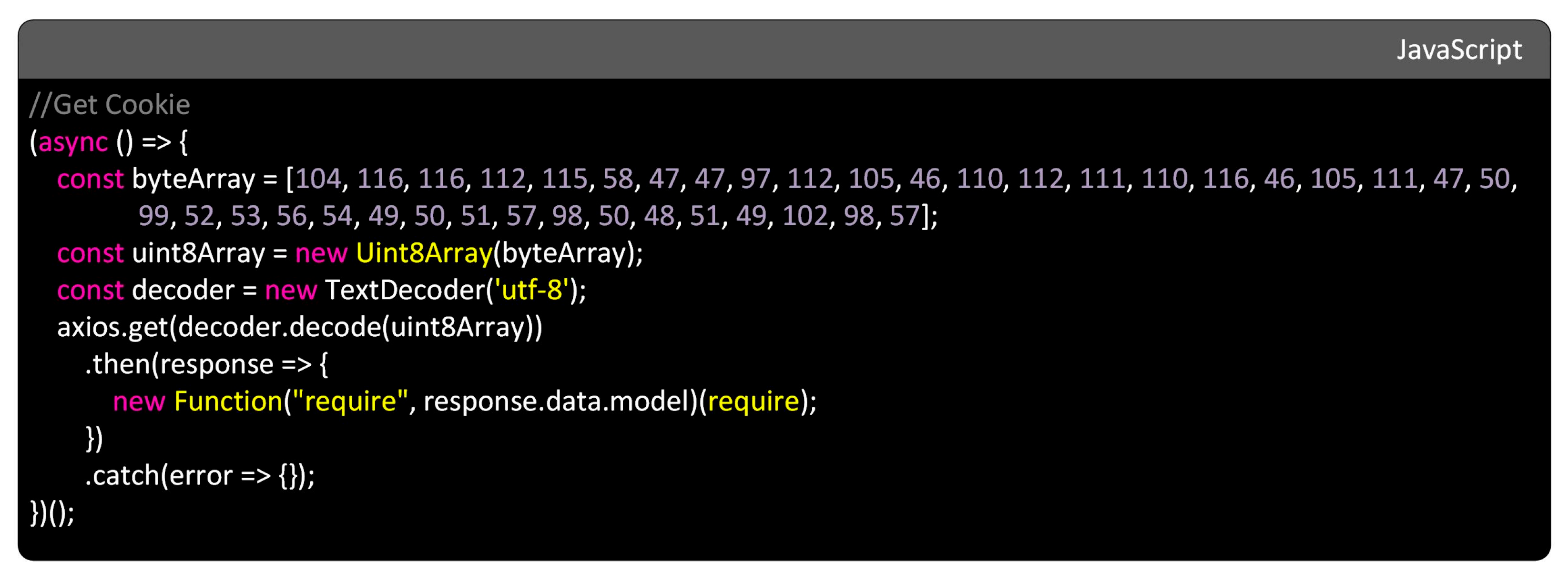

3.2. Code Exploitation

3.3. Forensic Analysis

4. Experimentation and Results

4.1. Impact Analysis of Social Engineering Attack

4.2. Impact Analysis of Code Exploitation

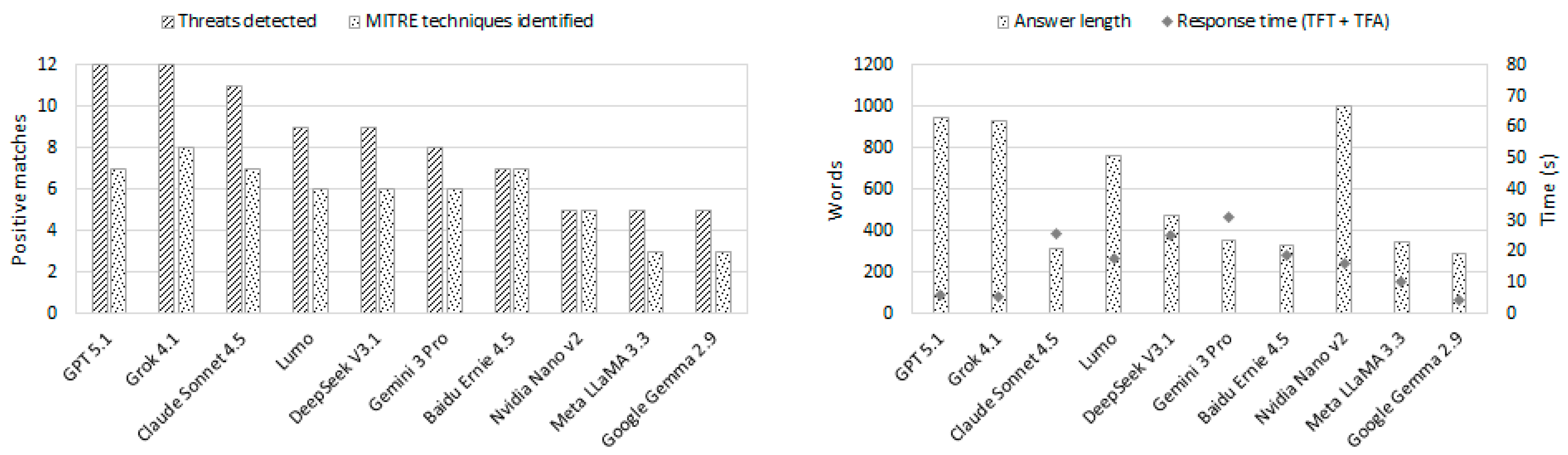

4.3. Impact Analysis on AI Assistants

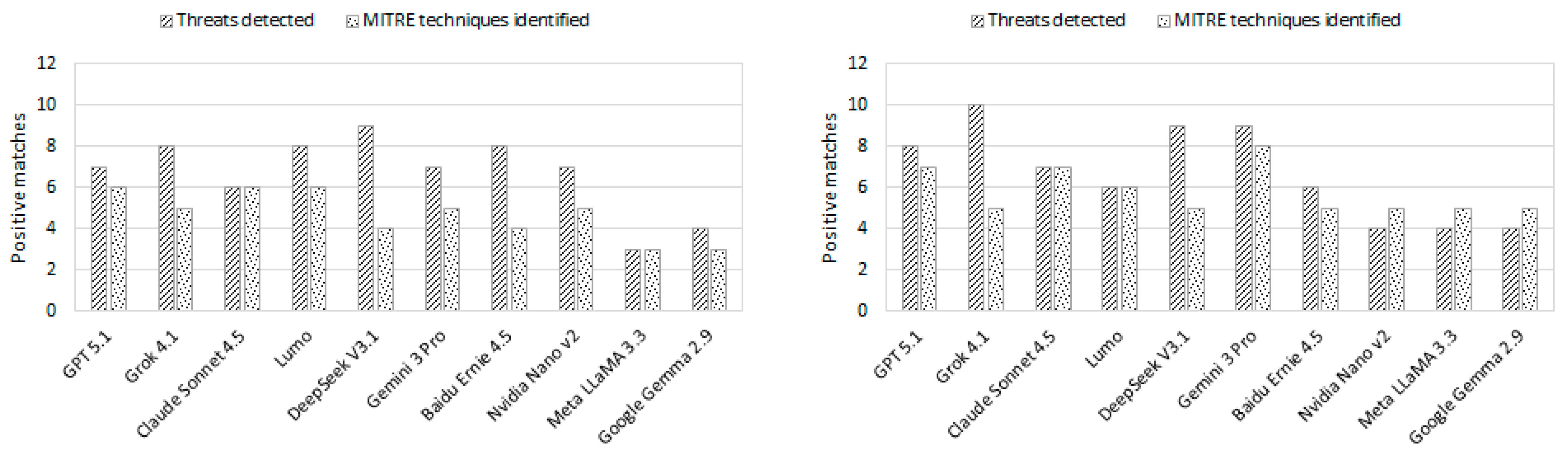

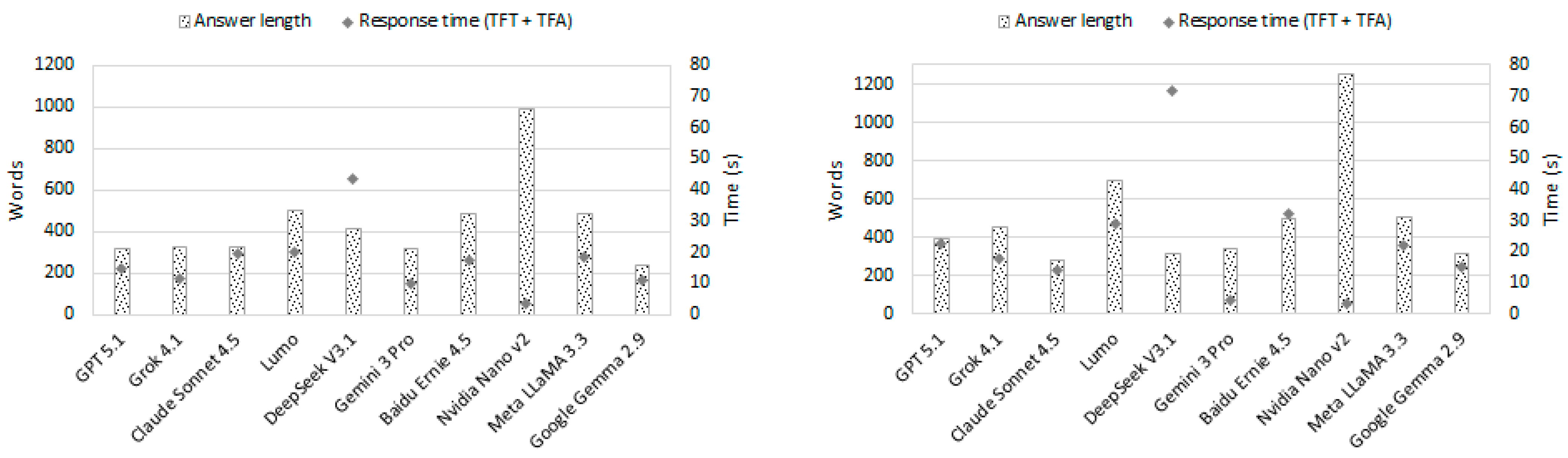

4.4. Impact of Prompt Variability on AI Assistants

5. Discussion

5.1. Mitigation Proposals in Social Engineering Attacks

5.2. Broader Context and Interdisciplinary Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mashtalyar, N.; Ntaganzwa, U.N.; Santos, T.; Hakak, S.; Ray, S. Social Engineering Attacks: Recent Advances and Challenges. In HCI for Cybersecurity, Privacy and Trust; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, A. Social Engineering Attacks Surge in 2025, Becoming Top Cybersecurity Threat. Technology Advice, LLC. 2025. Available online: https://www.techrepublic.com/article/news-social-engineering-top-cyber-threat-2025/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Hunkenschroer, A.L.; Luetge, C. Ethics of AI-Enabled Recruiting and Selection: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 178, 977–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, O.; Keleştemur, S.A. Quantifying Social Engineering Impact: Development and Application of the SEIS Model. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Dev. 2024, 7. Available online: https://www.ijsred.com/volume7/issue5/IJSRED-V7I5P58.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Dodda, D. How I Almost Got Hacked By A ‘Job Interview’. Technical Report. 2025. Available online: https://blog.daviddodda.com/how-i-almost-got-hacked-by-a-job-interview (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Dang, Q.-V. Enhancing Obfuscated Malware Detection with Machine Learning Techniques. In Future Data and Security Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, G.; Brookes, A.; Dowell, D. The Psychology of Internet Fraud Victimisation: A Systematic Review. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2019, 34, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo Sanguino, T.J. Enhancing Security in Industrial Application Development: Case Study on Self-generating Artificial Intelligence Tools. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.Y.; Valakuzhy, K.; Ahamad, M.; Blough, D.; Monrose, F. Understanding LLMs Ability to Aid Malware Analysts in Bypassing Evasion Techniques. In Proceedings of the ACM ICMI Companion ’24, San Jose, Costa Rica, 4–8 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadnagy, C. Social Engineering: The Science of Human Hacking, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloxberg, D. Social Engineering a Fake Interview or a Fake Job Candidate. Inspired eLearning. 2024. Available online: https://inspiredelearning.com/blog/social-engineering-fake-interview-candidate (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Steinmetz, K.F.; Holt, T.J. Falling for Social Engineering: A Qualitative Analysis of Social Engineering Policy Recommendations. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2023, 41, 592–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaoui, M.; Yousra, B.; Yassine, S.; Maleh, Y.; Ouazzane, K. A Comprehensive Taxonomy of Social Engineering Attacks and Defense Mechanisms: Toward Effective Mitigation Strategies. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 72224–72241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion; HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://ia800203.us.archive.org/33/items/ThePsychologyOfPersuasion/The%20Psychology%20of%20Persuasion.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Stajano, F.; Wilson, P. Understanding Scam Victims: Seven Principles for Systems Security. Commun. ACM 2011, 54, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M. Gaining Access with Social Engineering: An Empirical Study of the Threat. Inf. Syst. Secur. 2007, 16, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavi, D.; Reddy, M.S.M.; Ramya, M. Internet Employment Detection Scam of Fake Jobs via Random Forest Classifier. In Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havránek, M. Deceptive Development Targets Freelance Developers. ESET Research. Technical Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.welivesecurity.com/en/eset-research/deceptivedevelopment-targets-freelance-developers/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Whysall, Z. Cognitive Biases in Recruitment, Selection, and Promotion: The Risk of Subconscious Discrimination. In Hidden Inequalities in the Workplace; Palgrave Explorations in Workplace Stigma; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambín, Á.; Yazidi, A.; Vasilakos, A.; Haugerud, H.; Djenouri, Y. Deepfakes: Current and future trends. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, K. Obfuscation 101: Unmasking the Tricks Behind Malicious Code. Socket, Inc. Technical Report. 2025. Available online: https://socket.dev/blog/obfuscation-101-the-tricks-behind-malicious-code (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Dutta, T.S. Threat Actors Weaponize Malicious Gopackages to Deliver Obfuscated Remote Payloads. Cryptika Cybersecurity. Technical Report. 2025. Available online: https://cybersecuritynews.com/threat-actors-weaponize-malicious-gopackages/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Al-Karaki, J.; Al-Zafar Khan, M.; Omar, M. Exploring LLMs for Malware Detection: Review and Framework. arXiv. 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.07587 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Gajjar, J. MalCodeAI: AI-Powered Malicious Code Detection. GitHub. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/JugalGajjar/MalCodeAI (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Akinsowon, T.; Jiang, H. Leveraging LLMs for Behavior-Based Malware Detection; Sam Houston State University: Huntsville, TX, USA, 2024; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11875/4866 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Hamdi, A.; Fourati, L.; Ayed, S. Vulnerabilities and attacks assessments in blockchain 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0: Tools, analysis and countermeasures. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2024, 23, 713–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrila, R.; Zacharis, A. Advancements in Malware Evasion: Analysis Detection and the Future Role of AI. In Malware; Advances in Information Security; Gritzalis, D., Choo, K.K.R., Patsakis, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi Prity, F.; Islam, M.S.; Fahim, E.H.; Hossain, M.M.; Bhuiyan, S.H.; Islam, M.A.; Raquib, M. Machine learning-based cyber threat detection: An approach to malware detection and security with explainable AI insights. Hum.-Intell. Syst. Integr. 2024, 6, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Meng, Q.; Shang, F.; Oo, N.; Minh, L.T.H.; Lim, H.W.; Sikdar, B. MITRE ATT&CK Applications in Cybersecurity and The Way Forward. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.10825v1. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2502.10825v1 (accessed on 15 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, T.J. A Complexity Measure. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1976, SE-2, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrittwieser, S.; Wimmer, E.; Mallinger, K.; Kochberger, P.; Lawitschka, C.; Raubitzek, S.; Weippl, E.R. Modeling Obfuscation Stealth Through Code Complexity. In Computer Security—ESORICS 2023 Workshops; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Dubey, K.K.; Gupta, H.; Lamba, S.; Memoria, M.; Joshi, K. Keylogger Awareness and Use in Cyber Forensics. In Rising Threats in Expert Applications and Solutions; Rathore, V.S., Sharma, S.C., Tavares, J.M.R., Moreira, C., Surendiran, B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kührer, M.; Rossow, C.; Holz, T. Paint It Black: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Malware Blacklists. In Research in Attacks, Intrusions and Defenses; RAID 2014; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Stavrou, A., Bos, H., Portokalidis, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; p. 8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayson, P.; Garside, R. Comparing corpora using frequency profiling. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Comparing Corpora, ACL, Hong Kong, 7 October 2000; Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.3115/1117729.1117730 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Loria, S. TextBlob: Simplified Text Processing. 2018. Available online: https://textblob.readthedocs.io (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzoglou, E.; Kambourakis, G. Bypassing Antivirus Detection: Old-School Malware, New Tricks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.04149. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2305.04149.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Mawgoud, A.A.; Rady, H.M.; Tawfik, B.S. A Malware Obfuscation AI Technique to Evade Antivirus Detection in Counter Forensic Domain. In Enabling AI Applications in Data Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satriawan, A. From Shrimps to Whales: Knowing the Holder Crypto Hierarchy. BizTech. Technical Report. 2024. Available online: https://biztechcommunity.com/news/from-shrimps-to-whales-knowing-the-holder-crypto-hierarchy/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Mostyn, S. How Many Job Applications Does It Take to Get a Job? Career Agents. Technical Report. 2025. Available online: https://careeragents.org/blog/how-many-job-applications-does-it-take-to-get-a-job/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Verizon. 2024 Data Breach Investigations Report. Verizon Business. 2024. Available online: https://www.verizon.com/business/resources/T6de/reports/2024-dbir-data-breach-investigations-report.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- ISO/IEC 27001:2022; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/82875.html (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations (NIST Special Publication 800-53, Revision 5); U.S. Department of Commerce: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity. ENISA Threat Landscape 2023; ENISA: Heraklion, Greece, 2023; Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/enisa-threat-landscape-2023 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Floridi, L.; Cowls, J. A Unified Framework of Five Principles for AI in Society. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2019, 1, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tactic (ID) | Technique (ID) | Description | Observed Evidence | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Execution (TA0002) | Command & Scripting Interpreter: JavaScript (T1059.007) | Execution of code via JavaScript interpreter | Use of new Function("require", response.data.model)(require) to execute remote code | High |

| Command and Control (TA0011) | Web Protocols (T1071.001) | Communication with remote server over HTTP/HTTPS | Payload downloaded using axios.get(…) | High |

| Command and Control (TA0011) | Ingress Tool Transfer (T1105) | Transfer of tools or files to the victim system | Remote content retrieved prior to execution | High |

| Defense Evasion (TA0005) | Obfuscated Files or Information (T1027) | Concealment of information through obfuscation | URL reconstructed from byte array using TextDecoder(‘utf-8’); extremely long strings detected | High |

| Execution (TA0002) | Command & Scripting Interpreter: Visual Basic (T1059.005) | Execution of VBScript/JScript via WSH | Sandbox reported ‘WSH-Timer’ indicating Windows Script Host usage | Medium |

| Discovery (TA0007) | System Information Discovery (T1082) | Collection of system information | Check for available memory before execution | Medium |

| Persistence/Privilege Escalation | DLL Side-Loading (T1574.002) | Loading of malicious DLL through legitimate binary | Flagged by external heuristic analysis; not evidenced in JavaScript code | Low |

| Metric | Shannon Entropy (URL) | Shannon Entropy (Snippet) | Long Strings (>50 Chars) | Base64-Like Strings | Cyclomatic Complexity | CFG Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 4.39 | 4.73 | 0% | 0% | 2 | 1.09 |

| Interpretation | High randomness, consistent with obfuscation | Elevated entropy, indicates overall obfuscation | No very long strings; obfuscation via byte array | Obfuscation via byte-array reconstruction; avoids conventional Base64 encoding. | Low structural complexity typical of loader scripts | Sparse control flow; relies on dynamic execution |

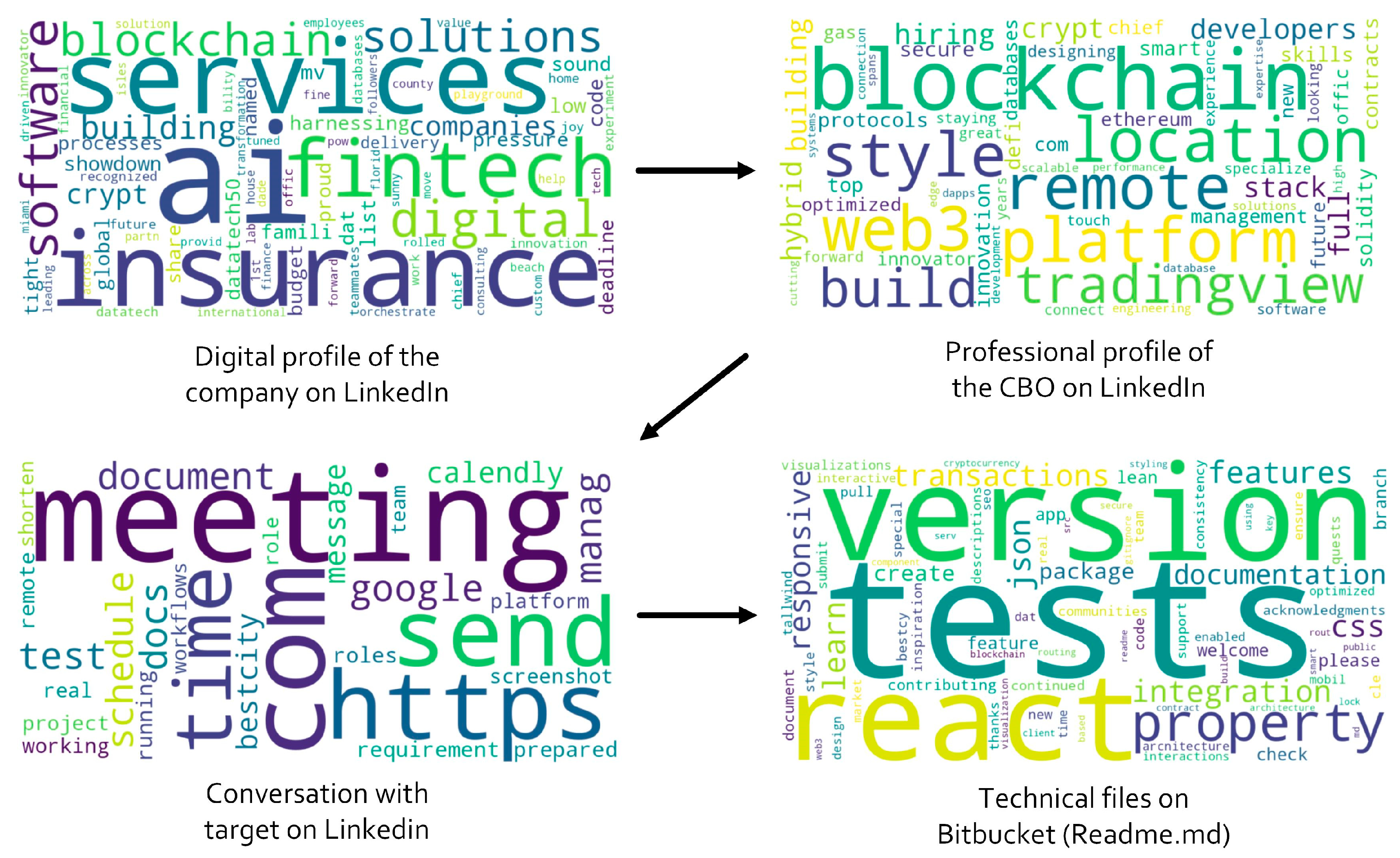

| Stage | Discursive Evolution | Syntactic Patterns | Persuasive Techniques | Credibility Markers | Action Triggers | Frequently terms (Top Terms per 1k) | Example of Expressions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

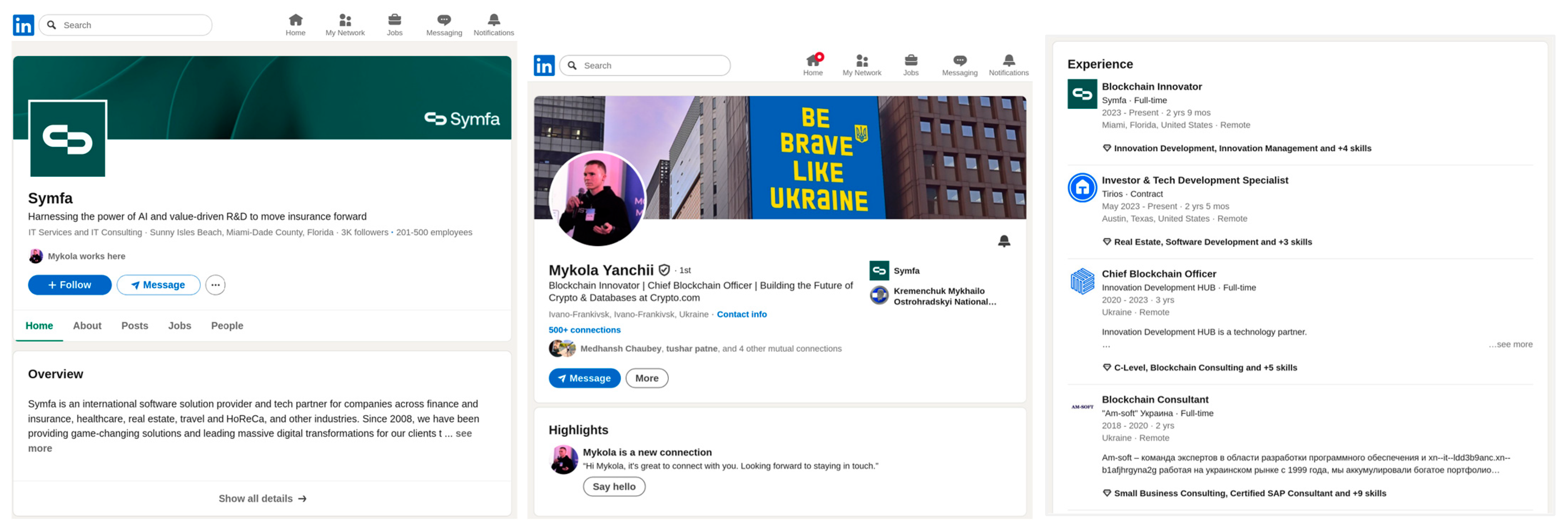

| Corporate digital profile on LinkedIn | Institutional → emphasis on capabilities & achievements; encourages engagement | Informative & passive declarative statements of legitimization; concise CTAs | Institutional authority, awards/listings & technical branding | References to awards, corporate language, specific technical names; history/collaborations | Contact Sales; reactivate premium; learn more; contribute | AI (36.4), solution (27.3), digital (18.2), fintech (18.2), software (18.2), service (18.2), blockchain (18.2), company (18.2) | Symfa has been named to the #DataTech50 list; contact Sales |

| Professional profile of the CBO on LinkedIn | Institutional → personal narrative that humanizes authority | Direct statements; formal/casual mix; recruitment imperatives | Personal authority, coherent trajectory & strategic humanization | Role at Crypto.com, professional experience, project references & professional publications | Join our team; apply now; looking forward to staying in touch | Blockchain (51.9), build (51.9), crypto (26.0), database (26.0), developer (26.0), full (26.0), hire (26.0), hybrid (26.0) | Building the future of crypto & databases; specializing in scalable Web3 solutions; join our team |

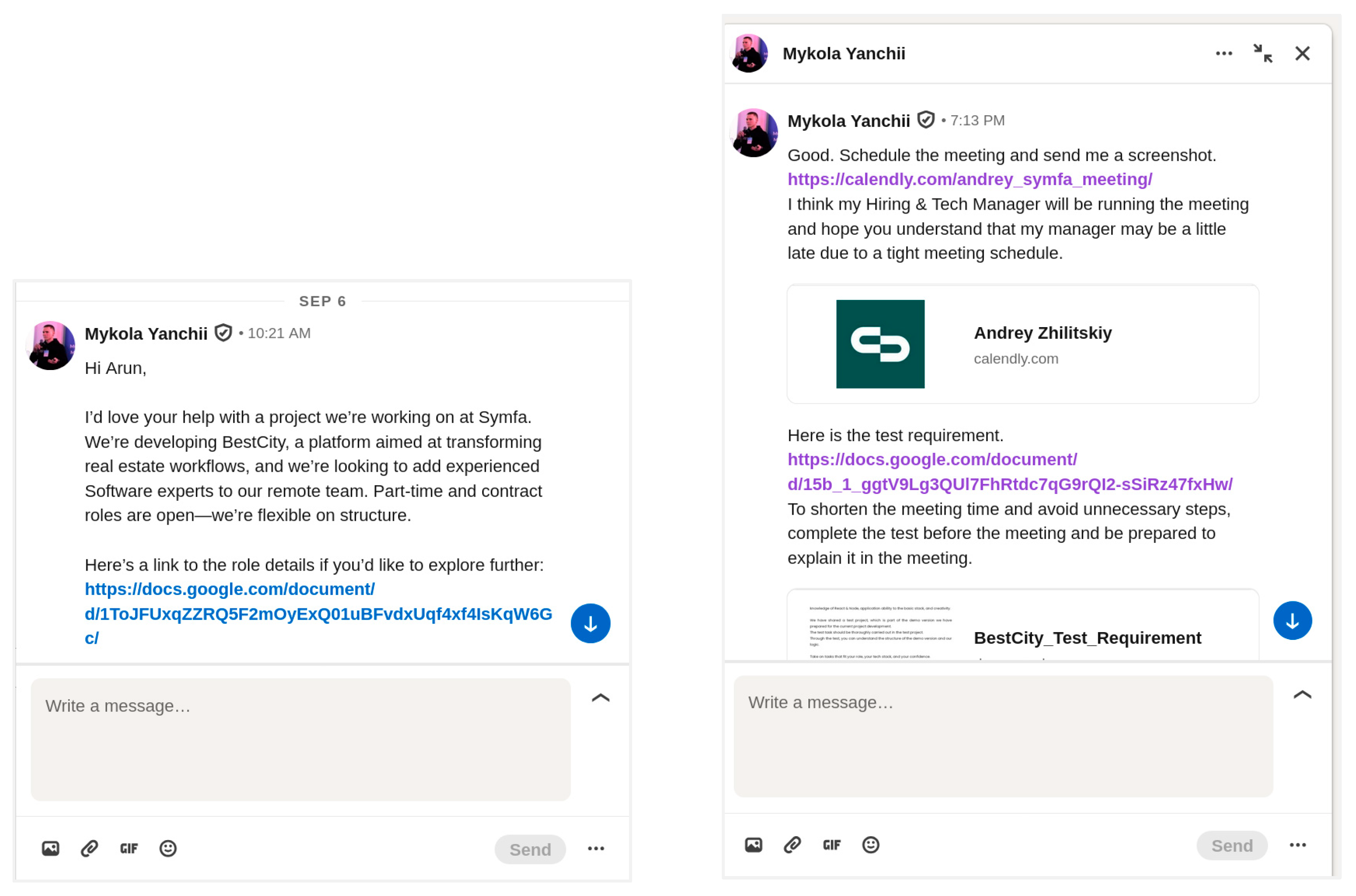

| Conversation with target on LinkedIn | Invitation → urgent & operational instructions | Polite imperatives; concise, action-oriented statements | Urgency, friction reduction & formal process simulation | References to roles (Hiring & Tech Manager), recognized tools (Google Docs, Calendly) | Schedule a meeting; send a screenshot; complete the test; prepare the document | Meet (120.0), com (80.0), http (60.0), send (60.0), docs (40.0), google (40.0), schedule (40.0), time (40.0) | The meeting will be run by our Hiring & Tech Manager; schedule a meeting; send a screenshot |

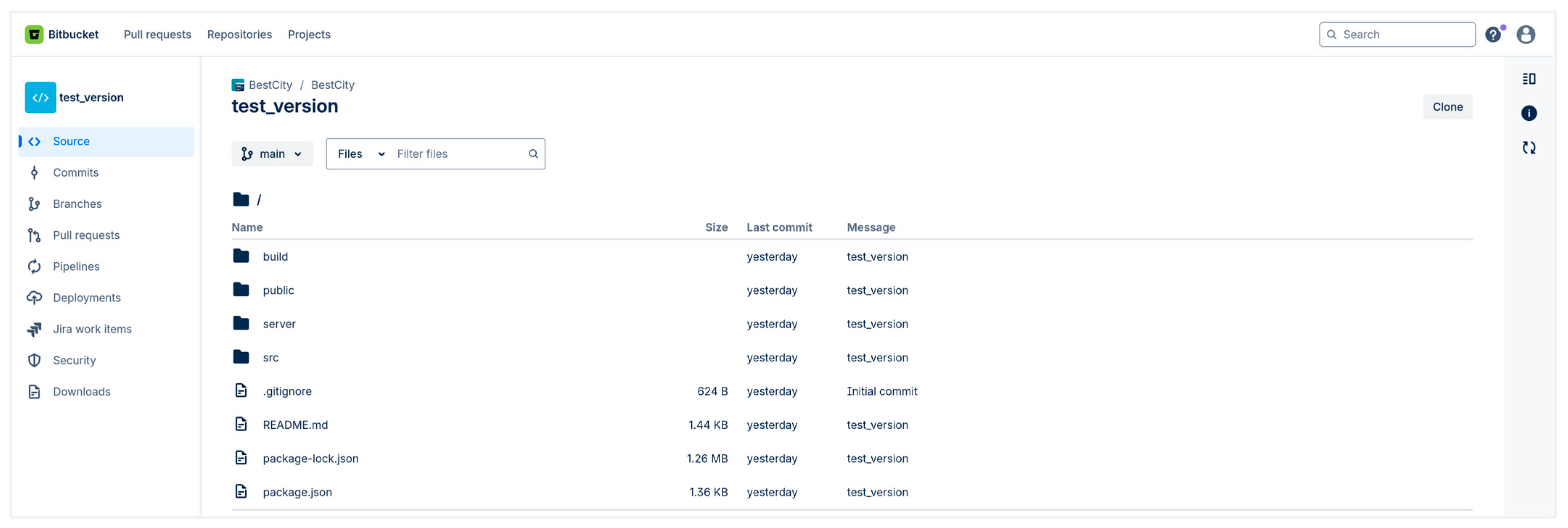

| Technical files on Bitbucket (Readme.md) | General introduction → technical instructions & contribution guidelines | Instructive & modular phrases; commands/labels | Professional standardization: commits, structure & documentation | Commit history, folder structure, technical documentation, acknowledgments | Learn more; contribute; check the documentation; run tests; submit pull request | Test (70.2), version (61.4), react (52.6), property (26.3), feature (26.3), integration (17.5), css (17.5), json (17.5) | BestCity is a modern real estate investment platform; the platform is built with React and Tailwind CSS; learn more |

| Phase | Sentiment (−1 to +1) | Authority Density (%) | Imperative Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Company’s digital profile published on LinkedIn | 0.183 | 1.30 | 14.29 |

| Professional profile of the CBO published on LinkedIn | 0.123 | 3.13 | 16.67 |

| Conversation with target on LinkedIn | 0.084 | 1.19 | 20.00 |

| Technical files hosted on Bitbucket | 0.272 | 0.00 | 45.46 |

| LLM Assistant | Threats Detected | Response Level | Risks | Evasive Techniques | Mitigations | Detection Mechanisms | Correspondence with MITER ATT&CK | Answer TFT/ TFA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT 5.1 | 12 positive matches | Very high (structured, multi-section analysis with concrete technical reasoning, prioritized remediation steps, safer coding patterns & grep-based detection checklist) | RCE; full Node module access; file & secret exfiltration; browser data; crypto wallets; malware install; lateral movement; persistence | URL obfuscation; hidden endpoint; dynamic new Function; HTTP(S) fetch; error swallowing | Do not run; rotate credentials; migrate wallets; block domain; isolate hosts; grep for patterns; static application security testing; sandbox inspection | Decode URL; detect HTTP(S) fetch; flag new Function/eval; grep obfuscation; monitor logs for network/process anomalies | T1059.007, T1071.001, T1105, T1027, T1005, T1041, T1059.003 | 949 words 0.24 s ± 0.07/5.71 s ± 1.74 |

| Grok 4.1 | 12 positive matches | Very high (technical, detailed, structured with functional code analysis, URL inspection, operational recommendations, environment & dependency analysis) | RCE, data theft, wallet access, malware installation, persistence, exfiltration, use of sensitive modules | Byte array obfuscation, intent hiding, using new Function, remote code dependency, error hiding | Secure payload inspection, environment audit, sandbox execution, static analysis, system reimage, module restriction | Manual analysis of remote content, pattern scanning, dependency checking, behavioral analysis | T1059.007, T1203, T1071.001, T1027, T1082, T1005, T1041, T1105 | 928 words 0.37 s ± 0.07/5.43 s ± 2.62 |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | 11 positive matches | High (explicit and concise warnings; identifies key risks and evasive patterns; practical advice provided, though without code examples or structured inspection) | RCE; crypto wallet theft; browser data & local files exfiltration; system discovery | URL obfuscation; dynamic execution | Remove code; review history; rotate credentials | New Function + require; URL decoding; remote payload execution | T1059.007, T1105, T1071.001, T1027, T1082, T1005, T1041 | 315 words 0.74 s ± 0.32/ 23.57 s ± 7.61 |

| Lumo | 9 positive matches | Very high (technical, detailed, structured, with functional code analysis, exploitation examples, operational recommendations & safe alternatives) | RCE, file access, data theft, interaction with sensitive libraries, persistence | URL obfuscation, error hiding, use of static endpoint | Manual payload inspection, integrity check, module restriction, error logging, sandbox execution | Remote content inspection, signature verification, endpoint behavior analysis | T1059.007, T1027, T1203, T1005, T1041, T1105 | 762 words 0.47 s ± 0.22/17.26 s ± 3.56 |

| DeepSeekV3.1 | 9 positive matches | High (clear, detailed, with implications, recommendations, without technical commands, without structured code analysis) | RCE, information theft, file access, malware installation, botnet resource use, lateral network movement | URL hiding using byte array | System isolation, antivirus scan, software origin verification, contact security team | N/A | T1059.007, T1027, T1203, T1005, T1041, T1105 | 476 words 0.15 s ± 0.01/24.97 s ± 15.11 |

| Meta LLaMA 3.3 | 5 positive matches | Medium-high (clear, enumeration of risks & recommendations, without technical commands, without functional code analysis) | Arbitrary execution, exposure to malicious code, vulnerability due to lack of validation, risk of external injection | URL hiding using byte array | Avoid dynamic execution, use clear URLs, validate and sanitize data, improve error handling, audit security | N/A | T1059.007, T1027, T1203 | 343 words 0.15 s ± 0.02/10.02 s ± 7.61 |

| Gemini 3 Pro | 8 positive matches | Medium-high (clear, step-by-step explanation; basic mitigation advice) | RCE; crypto wallet theft; file exfiltration; malware installation | URL obfuscation; domain typosquatting | Do not run; delete file; if executed: change passwords, move crypto assets, revoke sessions | URL decoding; detect new Function; HTTP(S) download pattern | T1059.007, T1105, T1071.001, T1027, T1005, T1041 | 352 words 0.68 s ± 0.29/31.61 s ± 13.17 |

| NVIDIA Nano v2 | 5 positive matches | High (clear, technical, structured; vulnerabilities & concrete mitigations; non-deep operational inspection of endpoint) | RCE, data theft, wallet access, file/read access, supply chain risk | Byte array URL obfuscation, silent error handling, require spoofing | Remove dynamic execution, validate/sign payloads, CSP hardening, static/dependency analysis, proper error logging | Manual payload/code review, signature/checksum verification, endpoint/content audit, behavioral/static analysis | T1059.007, T1203, T1071.001, T1027, T1105 | 1002 words 0.15 s ± 0.02/15.88 s ± 8.12 |

| Google Gemma 2.9 | 5 positive matches | Medium-high (clear, with explicit warnings, without functional analysis of the code, without structured inspection, without technical commands) | Arbitrary execution, access to sensitive modules, code injection, data exposure | Base64 in byte array, dynamic execution with new Function, lack of validation | Prevent dynamic execution, sanitize entries, restrict modules, apply principle of least privilege | Manual code review, dependency analysis, permission audit | T1059.007, T1203, T1027 | 291 words 0.17 s ± 0.06/4.06 s ± 1.10 |

| Baidu Ernie 4.5 | 7 positive matches | High (clear, technical, with functional code analysis, explicit warnings, no technical commands) | RCE, data theft, file exfiltration, malware installation, wallet access | Obfuscation with byte array, dynamic execution with new Function, error hiding, use of public endpoint | Do not run without inspection, manual review of remote JSON, use of sandbox, analysis of similar patterns | Manual endpoint inspection, codebase review, behavioral analysis | T1059.007, T1203, T1071.001, T1027, T1005, T1041, T1105 | 327 words 0.16 s ± 0.05/18.71 s ± 2.57 |

| LLM | True Positive (TP) | False Positive (FP) | False Negative (FN) | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT 5.1 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Grok 4.1 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 91.67% | 95.65% |

| Lumo | 9 | 0 | 3 | 100% | 75.00% | 85.71% |

| DeepSeek V3.1 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 100% | 75.00% | 85.71% |

| Gemini 3 Pro | 8 | 0 | 4 | 100% | 66.67% | 80.00% |

| Baidu Ernie 4.5 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 100% | 58.33% | 73.68% |

| Meta LLaMA 3.3 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 100% | 41.67% | 58.82% |

| Google Gemma 2.9 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 100% | 41.67% | 58.82% |

| NVIDIA Nano v2 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 100% | 41.67% | 58.82% |

| LLM | TP | FP | FN | Precision (S) | Recall (S) | F1-Score (S) | TP | FP | FN | Precision (T) | Recall (T) | F1-Score (T) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT 5.1 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 100% | 66.67% | 80.00% | 8 | 0 | 4 | 100% | 66.67% | 80.00% |

| Grok 4.1 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 100% | 50.00% | 66.67% | 10 | 0 | 2 | 100% | 83.33% | 90.91% |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 100% | 66.67% | 80.00% | 7 | 0 | 5 | 100% | 58.33% | 73.68% |

| Lumo | 9 | 0 | 3 | 100% | 75.00% | 85.72% | 6 | 0 | 6 | 100% | 50.00% | 66.67% |

| DeepSeek V3.1 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 100% | 58.33% | 73.68% | 9 | 0 | 3 | 100% | 75.00% | 85.71% |

| Gemini 3 Pro | 8 | 0 | 4 | 100% | 66.67% | 80.00% | 9 | 0 | 3 | 100% | 75.00% | 85.71% |

| Baidu Ernie 4.5 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 100% | 58.33% | 73.68% | 6 | 0 | 6 | 100% | 50.00% | 66.67% |

| Meta LLaMA 3.3 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 100% | 25.00% | 40.00% | 4 | 0 | 8 | 100% | 33.33% | 50.00% |

| Google Gemma 2.9 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 100% | 33.33% | 50.00% | 4 | 0 | 8 | 100% | 33.33% | 50.00% |

| NVIDIA Nano v2 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 100% | 66.67% | 80.00% | 4 | 0 | 8 | 100% | 33.33% | 50.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sanguino, T.d.J.M. Social Engineering Attacks Using Technical Job Interviews: Real-Life Case Analysis and AI-Assisted Mitigation Proposals. Information 2026, 17, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010098

Sanguino TdJM. Social Engineering Attacks Using Technical Job Interviews: Real-Life Case Analysis and AI-Assisted Mitigation Proposals. Information. 2026; 17(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanguino, Tomás de J. Mateo. 2026. "Social Engineering Attacks Using Technical Job Interviews: Real-Life Case Analysis and AI-Assisted Mitigation Proposals" Information 17, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010098

APA StyleSanguino, T. d. J. M. (2026). Social Engineering Attacks Using Technical Job Interviews: Real-Life Case Analysis and AI-Assisted Mitigation Proposals. Information, 17(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010098