Super Encryption Standard (SES): A Key-Dependent Block Cipher for Image Encryption

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Proposed Algorithm

3.1. Preparation Stage

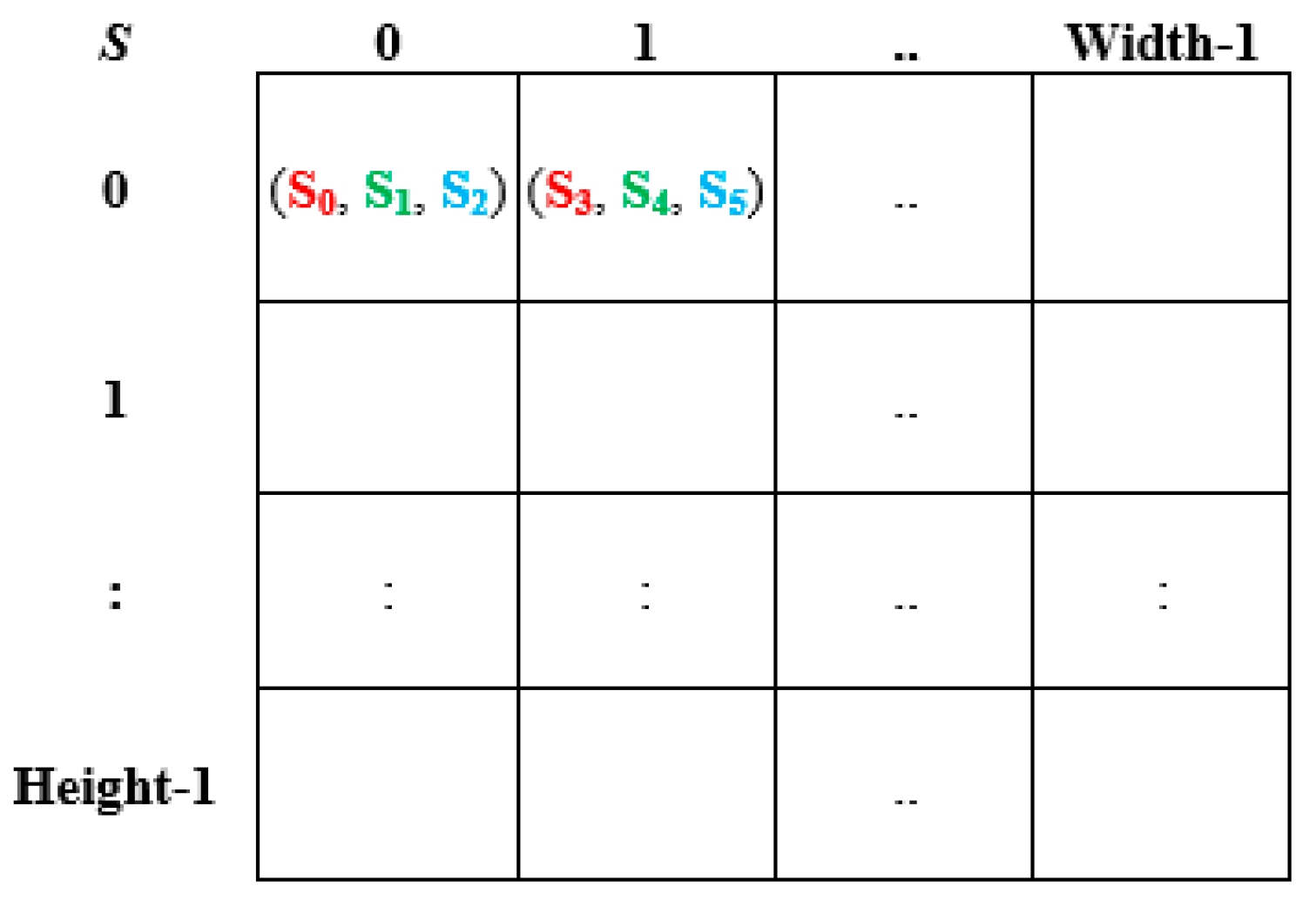

- Enter the source digital image S that will be encrypted with SES to produce an encrypted image E. S is an image with dimension n × m, where n is the width of the image in pixels, m is the height of the image in pixels and each pixel is represented as a vector of three bytes/colors (Red, Green, and Blue) as shown in Figure 1.

- 2.

- Enter a digital file of any type to use it as a key K. KSize represents the size (in bytes) of the K. The secure utilization of SES requires a safe sharing mechanism for key file K between the sender and receiver. The exchange of key file K can be accomplished through public key encryption methods, including RSA or ECC, or by utilizing Diffie–Hellman protocols to establish shared keys between parties. Secure key transfer may be accomplished by adding timestamp and nonce values and signature features to the key file, which guarantees authentication and tamper resistance and protects confidentiality.

- 3.

- Specify the dimension D of the data block. Where D is one of seven choices: (4 × 4, 8 × 8, 16 × 16, 32 × 32, 64 × 64, 128 × 128, 256 × 256).

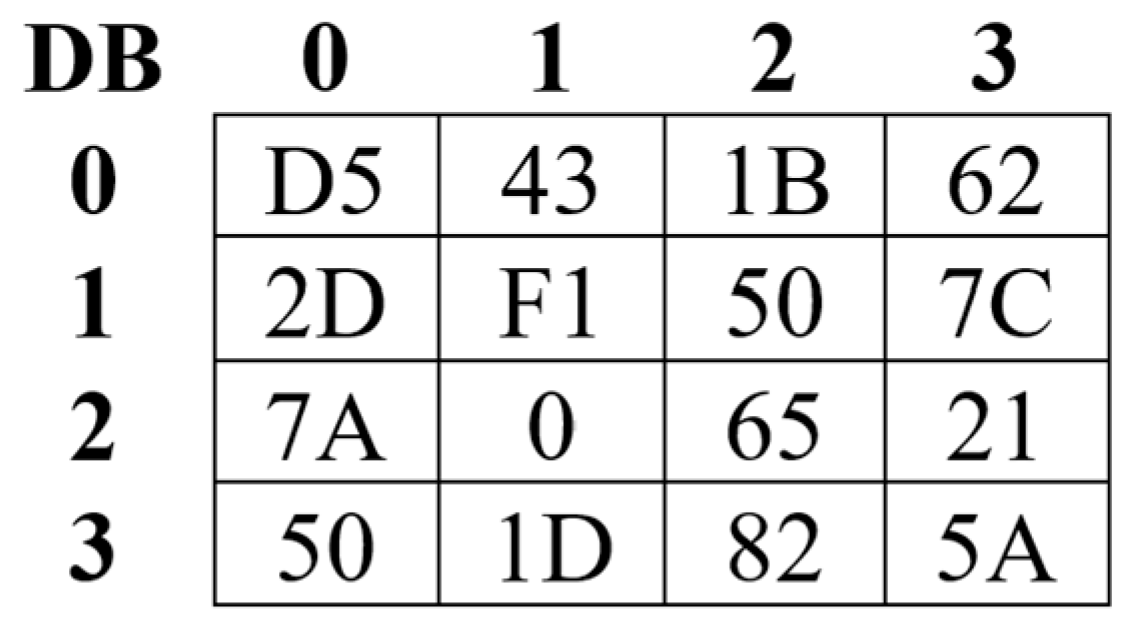

- SBox: represents a two-dimensional block (16 × 16) containing non-repeating values between (0…FF)16 distributed randomly in the SBox. The seed value Seedv of the pseudo-random generation algorithm is used here to distribute the values in SBox. This means that the generated SBox will differ based on the initial key K. The pseudo-random generation of the SBox in SES ensures that substitution layers are dynamic, adding a layer of unpredictability compared to AES’s static S-Box. The process uses a secure random number generator to construct S-Boxes that satisfy cryptographic properties like high nonlinearity and differential uniformity. Figure 2 shows an example of an SBox, where the numbers in each cell are represented in the hexadecimal number system.

- 2.

- DataBlocks (DB): represents a set of two-dimensional blocks (D × D) containing the bytes of the source image S. Where the number of these block NoDataBlocks (NDB) is calculated using Equation (4). Figure 3 shows an example of a DB with dimensions (4 × 4). The numbers in the cells are represented in the hexadecimal number system.

- 3.

- KeyBlocks (KB): represents a set of two-dimensional blocks (D × D) containing the bytes of the key K. In SES, encrypting each block in DB needs a different block in KB. So, the number of blocks NoKeyBlocks (NKB) in KB is the same as that of NDB. The first block KB0 of the KB is filled by sequentially reading the necessary bytes from K and filling them into KB0. The key generation process, as shown in Algorithm 1, successively generates the remaining blocks of the KB. Figure 4 shows an example of a KB with dimensions (4 × 4).

| Algorithm 1: Key Generation Process |

| For (b: 1 … NKB1) For (r: 0 … D − 1) For (c: 0 … D − 1) Row = Left (KBb−1 (r, c)) Column = Right (KBb−1 (r, c)) KBb (r, c) = SBox (Row, Column) KBb (r, c) = KBb (r, c) XOR KBb−1 (r, c) |

- 4.

- RowVector (RV): for each KBb, an RVb is generated that is a vector containing D elements, each RVb (j) element at index j (where j: 0 … D1) has a value that is calculated by performing an XOR operation between the values in row j in KBb using Equation (5). Figure 6 shows an example of an RV.

- 5.

- ColumnVector (CV): for each KBb, a CVb is generated that is a vector containing D elements, each CVb (j) element at index j (where j: 0 … D − 1) has a value that is calculated by performing an XORring operation between the values in column j in KBb using Equation (6). Figure 6 shows an example of a CV.

3.2. Encryption Stage

- The XOR Operation

| Algorithm 2: XOR Operation |

| For (b: 0 … NDB − 1) For (r: 0 … D − 1) For (c: 0 … D − 1) DBb (r, c) = DBb (r, c) XOR KBb (r, c) |

- 2.

- The Swap Operation

| Algorithm 3: Swap Operation |

| For (b: 0 … NDB − 1) For (r: 0 … D − 1) For (c: 0 … D − 1) If (RVb(r) = CVb(c)) DBb (r, c) = Swap (Left (DBb (r, c)), Right (DBb (r, c))) |

3.3. Design Rationale

4. Experimental Results and Evaluation

4.1. Key Size and Key Space

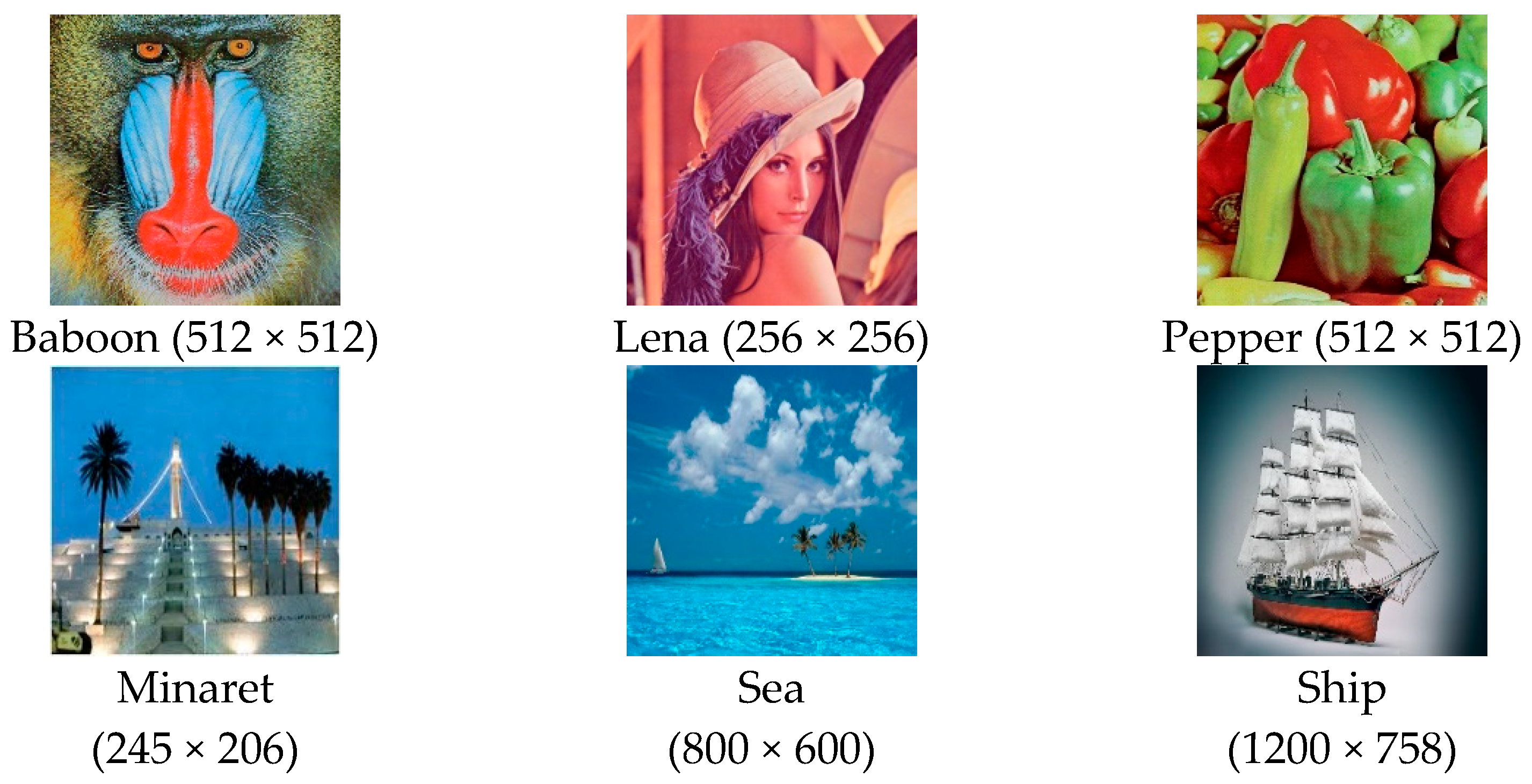

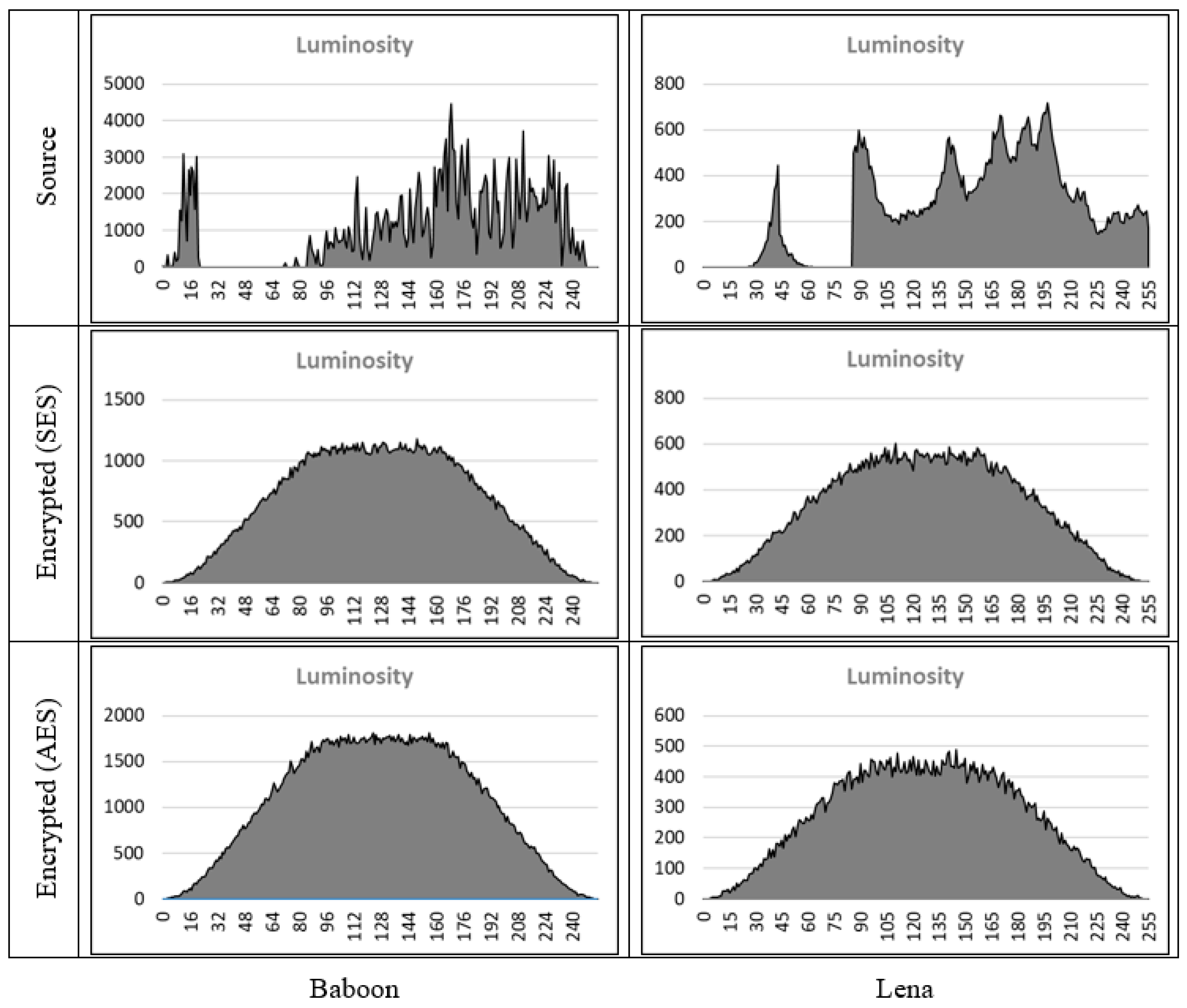

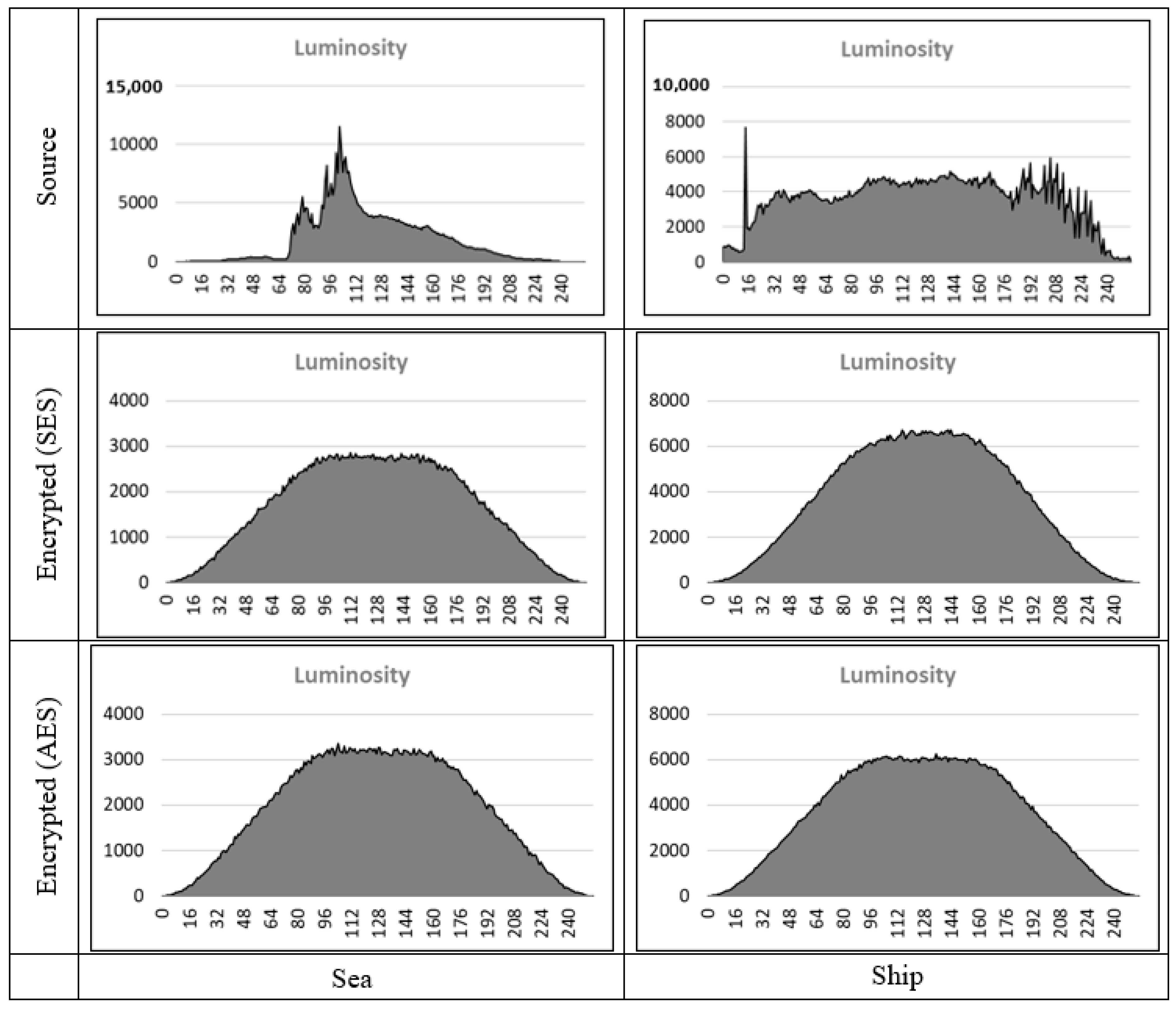

4.2. Visual and Statistical Tests

4.3. Encryption Execution Time

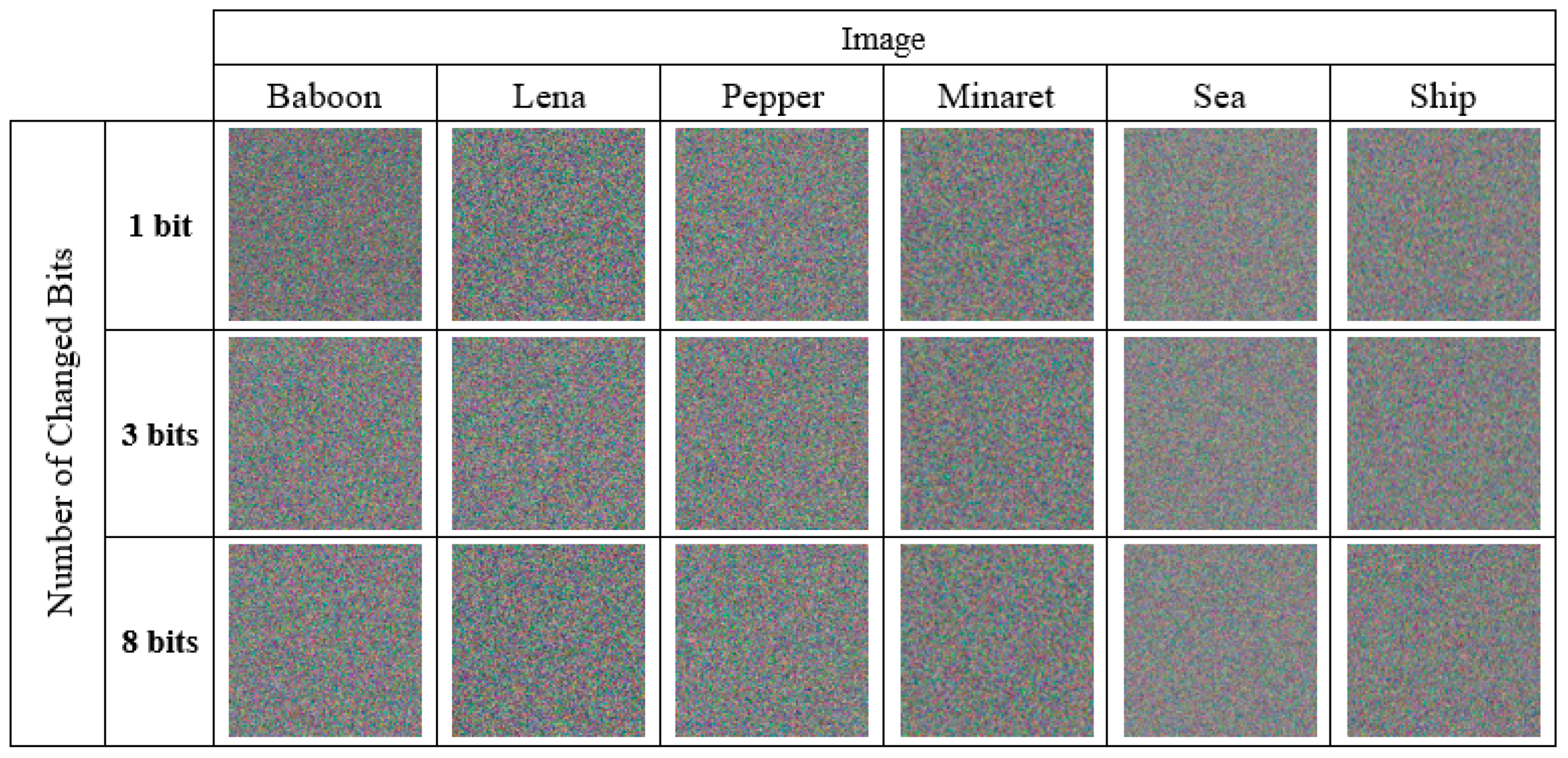

4.4. Avalanche Effect

4.4.1. The Resulting Changes in the Encrypted Image

4.4.2. The Resulting Changes in the Recovered Source Image

4.5. Correlation Analysis

4.6. NMAE and PSNR Metrics

4.7. Information Entropy

4.8. NPCR and UACI Metrics

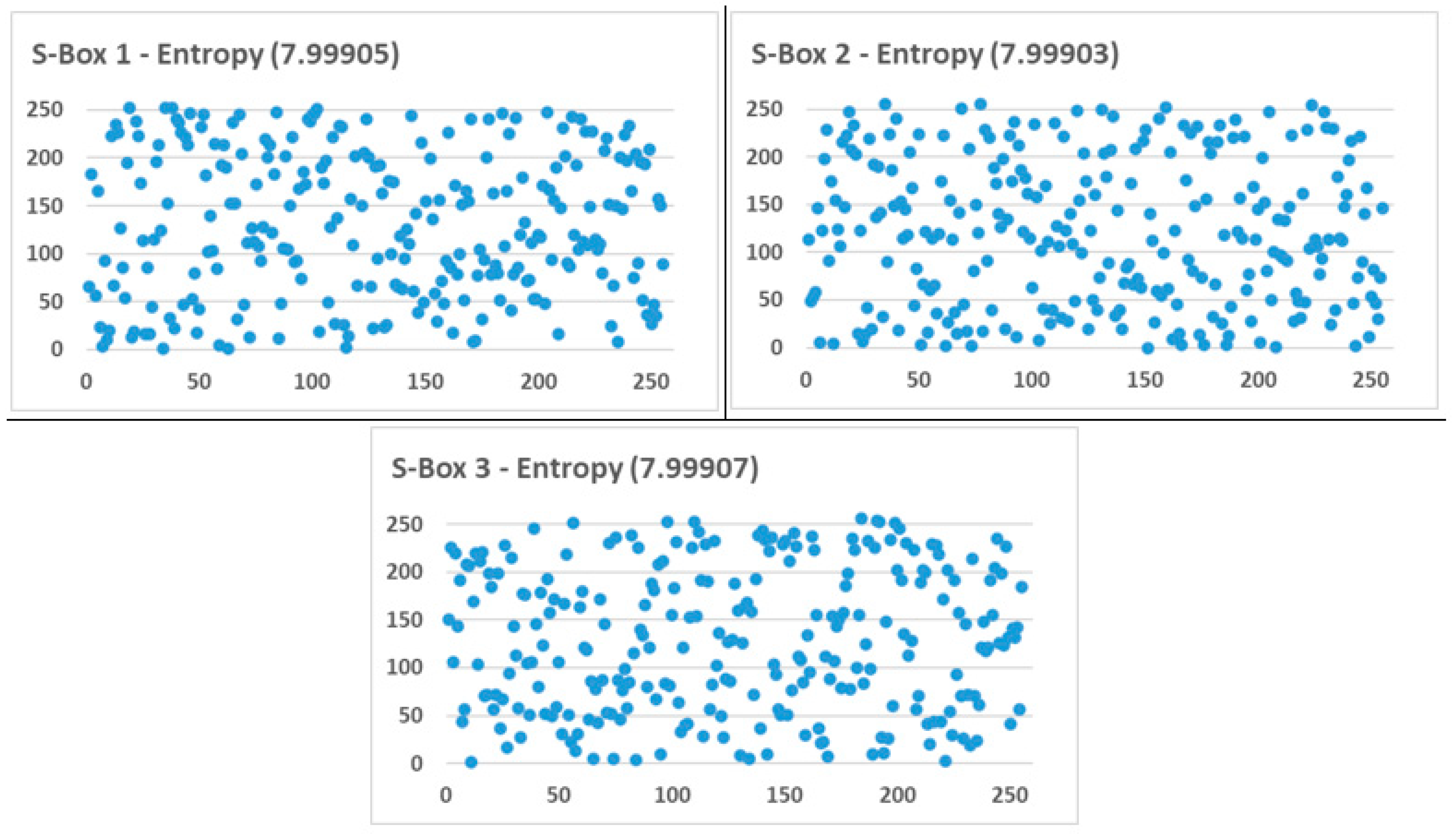

4.9. S-Box Properties

4.9.1. Random Distribution of Bytes

- Initialize Value List: Create a list of 256 unique values from 00 to FF.

- Shuffle the Value List: Use a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) seeded with SeedV to shuffle the list using the Fisher–Yates shuffle.

- Fill the S-Box Matrix: Map the shuffled 1D list into a 16 × 16 matrix SBox[i][j], filling rows left to right, top to bottom.

- Output the S-Box: The resulting SBox[16][16] matrix is used as the substitution table for SES encryption.

4.9.2. Differential Cryptanalysis of S-Box

4.9.3. Linear Cryptanalysis of S-Box

4.10. Performance Discussion and Limitations

5. Security Analysis

5.1. Differential Cryptanalysis

5.2. Linear Cryptanalysis

5.3. Related-Key Considerations

5.4. Algebraic Attacks

5.5. Summary of Security Assessment

6. Conclusions

7. Declarations

- The authors have no financial interest or claim to any aspect of this research paper.

- The authors of this research paper have been directly involved in the design, execution, or analysis of this study.

- The authors of this manuscript have read and approved the final draft that was submitted.

- Material contained in this manuscript has not been previously copyrighted or published.

- The material in this manuscript is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

- The material in this manuscript will not be copyrighted, submitted, or published in any other venue while its acceptance by the Journal is under consideration.

- There are no related documents or abstracts, whether published or not, which are authored by the writer of this paper.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahani, S.; Ghaemmaghami, S. Colour image steganography method based on sparse representation. IET Image Process. 2015, 9, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracevic, M.H.; Adamovic, S.Z.; Miskovic, V.A.; Elhoseny, M.; Macek, N.D.; Selim, M.M.; Shankar, K. Data encryption for internet of things applications based on catalan objects and two combinatorial structures. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2020, 70, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, T.; Xiang, Y.; Guo, S.; Rong, Y. Rank-based image watermarking method with high embedding capacity and robustness. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saračević, M.; Adamović, S.; Maček, N.; Selimi, A.; Pepic, S. Source and channel models for secret-key agreement based on Catalan numbers and the lattice path combinatorial approach. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2021, 37, 469–482. [Google Scholar]

- Dridi, M.; Hajjaji, M.A.; Bouallegue, B.; Mtibaa, A. Cryptography of medical images based on a combination between chaotic and neural network. IET Image Process. 2015, 10, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Huang, X. An image encryption algorithm based on autoblocking and electrocardiography. IEEE Multimed. 2015, 23, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.L.P.; Xia, L. Medical image encryption using edge maps. Signal Process. 2017, 132, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haj, A.; Abandah, G.; Hussein, N. Crypto-based algorithms for secured medical image transmission. IET Inf. Secur. 2015, 9, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Han, W.; Yu, H.; Zhu, Z. An image encryption algorithm based on random hamiltonian path. Entropy 2020, 22, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, B. Robust image encryption algorithm in dwt domain. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 39027–39049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, L. Chaos-Based Image Encryption: Review, Application, and Challenges. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakor, M.Y.; Khaleel, M.I.; Safran, M.; Alfarhood, S.; Zhu, M. Dynamic AES encryption and blockchain key management: A novel solution for cloud data security. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 26334–26343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banoth, R.; Regar, R. Asymmetric Key Cryptography. In Classical and Modern Cryptography for Beginners; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 109–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnytskyi, V.; Korchenko, O.; Lada, N.; Ziubina, R.; Wieclaw, L.; Hamera, L. Cryptographic encoding in modern symmetric and asymmetric encryption. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 207, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, J.; Thakur, D. Analysis of symmetric and asymmetric key algorithms. In ICT Analysis and Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, J. A Survey of Data Security Sharing. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.K.; Ghaffari, A.; Besharat, S.; Afshari, H. Security of internet of things based on cryptographic algorithms: A survey. Wirel. Netw. 2021, 27, 1515–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attkan, A.; Ranga, V. Cyber-physical security for IoT networks: A comprehensive review on traditional, blockchain and artificial intelligence based key-security. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 3559–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halak, B.; Yilmaz, Y.; Shiu, D. Comparative analysis of energy costs of asymmetric vs symmetric encryption-based security applications. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 76707–76719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoui, M.; Mestiri, H.; Bouallegue, B.; Hamdi, B.; Machhout, M. An improvement of both security and reliability for AES implementations. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 9844–9851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, F.S.; Ali, M.L. A novel byte-substitution architecture for the AES cryptosystem. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138457. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.L.; Dai, C.R.; Leu, F.Y.; You, I. A secure data encryption method employing a sequential–logic style mechanism for a cloud system. Int. J. Web Grid Serv. 2015, 11, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiessen, T.; Knudsen, L.R.; Kölbl, S.; Lauridsen, M.M. Security of the AES with a secret S-box. In International Workshop on Fast Software Encryption; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidehi, M.; Rabi, B.J. Enhanced mixcolumn design for aes encryption. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, S.M.; Rahma, A.M.S. An innovative method for enhancing advanced encryption standard algorithm based on magic square of order 6. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2023, 12, 1684–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamido, H.V.; Sison, A.M.; Medina, R.P. Modified AES for text and image encryption. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2018, 11, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PPatil, P.; Karoshi, A.; Marje, A.; Desai, V. Enhancing S-Box Nonlinearity in AES for Improved Security Using Key-Dependent Dynamic S-Box. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Communication, Computing and Electronics Systems: ICCCES 2022; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Abikoye, O.C.; Haruna, A.D.; Abubakar, A.; Akande, N.O.; Asani, E.O. Modified advanced encryption standard algorithm for information security. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Jaiswal, M. An enhanced AES algorithm using cascading method on 400 bits key size used in enhancing the safety of next generation internet of things (IOT). In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Computing, Communication and Automation (ICCCA), Greater Noida, India, 5–6 May 2017; pp. 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Qi, Y.; Wan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H. A fast AES encryption method based on single LUT for industrial wireless network. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Identification, Information and Knowledge in the Internet of Things, Beijing, China, 17–18 October 2014; pp. 158–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, O.B.; Kole, D.K.; Rahaman, H. An optimized S-box for advanced encryption standard (AES) design. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Advances in Computing and Communications, Chennai, India, 3–5 August 2012; pp. 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- Farwa, S.; Shah, T.; Idrees, L. A highly nonlinear S-box based on a fractional linear transformation. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q. A secure and highly efficient first-order masking scheme for AES linear operations. Cybersecurity 2021, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Karuppiah, M.; Rajkumar, S.; Niranchana, R. Modification of AES using genetic algorithms for high-definition image encryption. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Technol. Appl. 2018, 17, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghier, A.; Li, J.; Sun, D.Z. Advanced encryption standard based on key dependent S-Box cube. IET Inf. Secur. 2019, 13, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Hani, M.; Al-Husainy, M.; Al-Zu’bi, A.; Al-Asad, G.; Albatienh, S.; Abuoliem, H. Robust Multilayer Encryption for Protecting Healthcare Data in Cloud Computing. IAENG Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2025, 52, 3035–3042. [Google Scholar]

- Alabdullah, B.; Beloff, N.; White, M. E-ART: A new encryption algorithm based on the reflection of binary search tree. Cryptography 2021, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husainy, M.A.F.; Al-Sewadi, H.A. Full Capacity Image Steganography Using Seven-Segment Display Pattern as Secret Key. J. Comput. Sci. 2018, 14, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, B.; Mobasseri, M.; Enayatifar, R. A secure, efficient and super-fast chaos-based image encryption algorithm for real-time applications. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2023, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, P.K.; Moon, S.Y.; Park, J.H. Advanced lightweight encryption algorithms for IoT devices: Survey, challenges and solutions. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2024, 15, 1625–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fritts, J.E.; Goldman, S.A. Entropy-based objective evaluation method for image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Storage and Retrieval Methods and Applications for Multimedia 2004, San Jose, CA, USA, 20–22 January 2004; pp. 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Asad, G.; Al-Husainy, M.; Bani-Hani, M.; Al-Zu’bI, A.; Albatienh, S.; Abuoliem, H. Comparative Assessment of Hash Functions in Securing Encrypted Images. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 18750–18755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Encryption Algorithm | Encryption Key | |

|---|---|---|

| Key Size (Bits) | Key Space | |

| AES | 256 | 2256 |

| SES | > | |

| Image | Encryption Time ET (s) | |

|---|---|---|

| SES | AES | |

| Baboon | 0.441 | 0.614 |

| Lena | 0.120 | 0.352 |

| Pepper | 0.431 | 0.61 |

| Minaret | 0.139 | 0.152 |

| Sea | 0.781 | 1.252 |

| Ship | 1.149 | 2.2 |

| Average | 0.510 | 0.863 |

| Image | Number of Bits Changed in the Encryption Key (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Bit | 3 Bits | 8 Bits | |

| Baboon | 49.980 | 50.026 | 50.239 |

| Lena | 50.047 | 50.130 | 50.142 |

| Pepper | 50.041 | 50.199 | 50.210 |

| Minaret | 50.450 | 50.464 | 50.571 |

| Sea | 50.066 | 50.075 | 50.093 |

| Ship | 49.998 | 50.012 | 50.025 |

| Image | H | V | D | A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SES | AES | SES | AES | SES | AES | SES | AES | |

| Baboon | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.015 | 0.02 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| Lena | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.014 | 0.034 | 0.032 | 0.016 | 0.02 |

| Pepper | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.03 | 0.018 | 0.018 |

| Minaret | 0.032 | 0.038 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.012 | 0.021 | 0.049 |

| Sea | 0.004 | 0.045 | 0.009 | 0.029 | 0.021 | 0.027 | 0.019 | 0.016 |

| Ship | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.032 | 0.037 | 0.01 | 0.015 | 0.012 | 0.012 |

| Average | 0.010 | 0.018 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.023 | 0.016 | 0.020 |

| Image | NMAE (%) | PSNR (db) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SES | AES | SES | AES | |

| Baboon | 72.12 | 68.76 | 6.80 | 7.30 |

| Lena | 65.63 | 63.19 | 7.32 | 7.67 |

| Pepper | 90.50 | 89.39 | 6.22 | 6.40 |

| Minaret | 67.46 | 62.99 | 8.78 | 8.53 |

| Sea | 66.99 | 63.94 | 7.52 | 7.32 |

| Ship | 93.52 | 89.06 | 4.85 | 4.81 |

| Average | 76.037 | 72.888 | 6.915 | 7.005 |

| Image | Entropy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Source Image | Encrypted Image | ||

| SES | AES | ||

| Baboon | 7.1079 | 7.9019 | 7.9020 |

| Lena | 7.7300 | 7.9902 | 7.9906 |

| Pepper | 7.1249 | 7.9946 | 7.9934 |

| Minaret | 7.5235 | 7.9998 | 7.9987 |

| Sea | 7.7586 | 7.9886 | 7.9799 |

| Ship | 7.8679 | 7.9989 | 7.9701 |

| Average | 7.7200 | 7.9790 | 7.9720 |

| Image | NPCR | UACI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SES | AES | SES | AES | |

| Baboon | 99.66 | 99.61 | 33.90 | 33.45 |

| Lena | 99.79 | 99.63 | 33.99 | 33.43 |

| Pepper | 99.96 | 99.61 | 33.59 | 33.46 |

| Minaret | 99.79 | 99.63 | 35.40 | 33.50 |

| Sea | 99.81 | 99.62 | 34.82 | 33.44 |

| Ship | 99.87 | 99.60 | 35.65 | 33.46 |

| Average | 99.81 | 99.62 | 34.56 | 33.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abbas Fadhil Al-Husainy, M.; Al-Shargabi, B.; Sabri, O. Super Encryption Standard (SES): A Key-Dependent Block Cipher for Image Encryption. Information 2026, 17, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010002

Abbas Fadhil Al-Husainy M, Al-Shargabi B, Sabri O. Super Encryption Standard (SES): A Key-Dependent Block Cipher for Image Encryption. Information. 2026; 17(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbas Fadhil Al-Husainy, Mohammed, Bassam Al-Shargabi, and Omar Sabri. 2026. "Super Encryption Standard (SES): A Key-Dependent Block Cipher for Image Encryption" Information 17, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010002

APA StyleAbbas Fadhil Al-Husainy, M., Al-Shargabi, B., & Sabri, O. (2026). Super Encryption Standard (SES): A Key-Dependent Block Cipher for Image Encryption. Information, 17(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010002