Bridging the Engagement–Regulation Gap: A Longitudinal Evaluation of AI-Enhanced Learning Attitudes in Social Work Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The AI Imperative in Social Work Education

2.2. An Integrated Theoretical Framework

2.3. Research Objectives and Hypotheses

- (1)

- Objective 1: To examine the psychometric performance of the AILAS within the context of an AI-integrated curriculum, focusing on internal consistency and structural coherence at the cohort level rather than on individual change.

- •

- H1a. The AILAS will demonstrate strong internal consistency (α > 0.90) at the post-test stage.

- •

- H1b. Inter-dimensional correlations will remain stable, indicating a coherent attitudinal structure.

- (2)

- Objective 2: To examine whether an AI-integrated curriculum with explicit SRL-oriented scaffolding is associated with cohort-level shifts in students’ AI-related learning attitudes over a short instructional period, with particular attention being paid to behavioral routines, planning-related attitudes and overall engagement while acknowledging the exploratory and non-causal nature of the pre-post cohort-level design.

- •

- H2a. At the cohort level students in the post-test cohort will report higher levels of Learning Habits (E) and Learning Planning (D) than those in the pre-test cohort following exposure to SRL-oriented instructional scaffolding. This hypothesis focuses on whether structured goal-setting activities and routine-building practices are associated with short-term shifts in behavioral engagement and planning-related learning attitudes.

- •

- H2b. This study also seeks to determine whether the Learning Process (F) reflecting students’ perceived engagement and active participation in AI-supported learning activities remains stable or shows modest improvement from the pre-test to the post-test stages. This hypothesis is based on the expectation that SRL-oriented scaffolding does not detract from engagement and may instead help sustain or slightly enhance students’ involvement in the learning processes.

- •

- H2c. Overall, at the post-test stage, the cohort is expected to demonstrate higher aggregate scores in AI-related learning attitudes compared with the pre-test stage. This hypothesis reflects the assumption that continued exposure to SRL-oriented scaffolding may be associated with cumulative shifts across motivational, behavioral, and process-related dimensions of learning, rather than changes confined to a single domain.

- (3)

- Objective 3: To explore potential cohort-level differences in AI-related learning attitudes across selected demographic characteristics (gender and academic level); these analyses are treated as descriptive and exploratory, accounting for the modest sample size and unlinked responses.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Intervention: AI-Integrated Curriculum with SRL Scaffolding

- (1)

- Weekly goal-setting templates (Weeks 1–6): Students set concrete learning goals for their AI use each week (e.g., use AI to generate alternative intervention options, then compare them with textbook guidelines), directly targeting Dimension D (Learning Planning).

- (2)

- Reflection prompts (Weeks 2–6): Beginning in Week 2, students completed short, structured reflection sheets designed to encourage metacognitive review of their AI use. These prompts asked students to consider how they had used AI in their coursework, which approaches they found helpful, which practices felt overly passive and how they might adjust their strategies in subsequent weeks. This reflective activity was intended to support the development of learning methods and to reinforce more consistent Learning Habits (Dimensions C and E).

- (3)

- Peer accountability partnerships (Weeks 3–6): From Week 3 onward, students were paired with a peer partner to share their weekly learning goals and discuss their progress. These brief peer check-ins provided opportunities for mutual feedback and informal accountability, helping students to sustain their planning and reflection routines over time rather than treating them as isolated tasks.

- (4)

- SRL strategy modeling (Weeks 1–6): The instructors explicitly verbalized their own planning, monitoring and evaluation steps when demonstrating AI use, making otherwise-invisible SRL processes observable to the students.

- (5)

- Progress-tracking dashboards (Weeks 5–6): Simple visual dashboards summarized completion rates for goal-setting activities and reflections at the class level, reinforcing collective responsibility and sustaining engagement. These dashboards provided feedback at the group level without evaluating individual performances.

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. AI-Enhanced Learning Attitude Scale

- •

- Item 5: Enhanced AI coursework is difficult for me.

- •

- Item 17: I often memorize AI content without understanding it.

- •

- Item 18: AI learning has little relevance to my life.

3.4.2. Demographic Variables

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

3.5.1. Data Collection

3.5.2. Data Analysis

- •

- Reliability (H1a): Cronbach’s α was computed for the total scale and each subscale at the pre-test and post-test stages.

- •

- Structural consistency (H1b): Pearson correlations among the six dimensions were computed at each time point. Absolute differences between corresponding coefficients (pre vs. post) were used to assess stability, with |Δ| ≤ 0.10 considered indicative of high stability.

- •

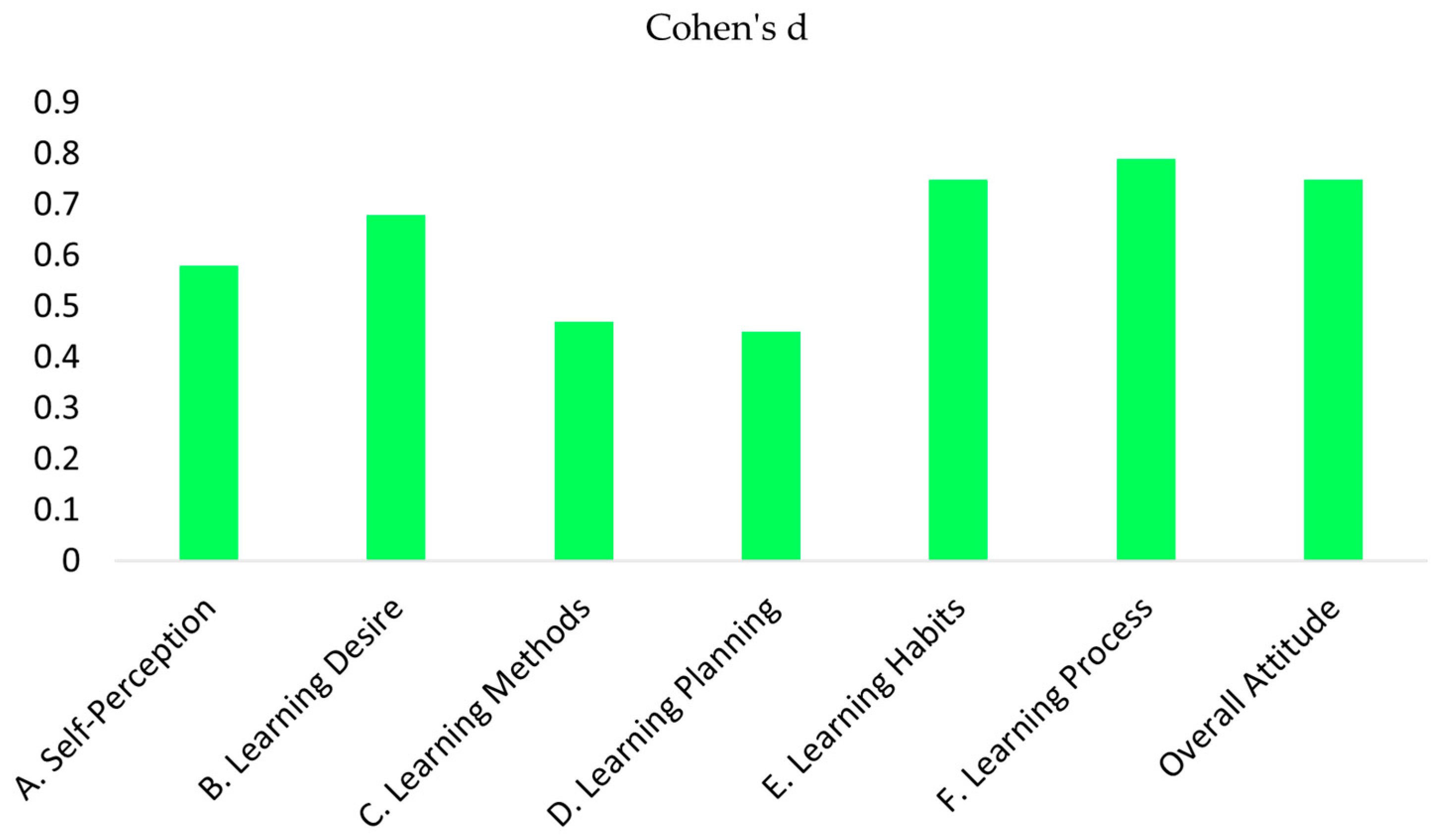

- Intervention effectiveness (H2a–H2c): Because the pre-test and post-test questionnaires were administered anonymously and individual responses could not be linked across time, inferential pre-post comparisons were conducted at the cohort level. Independent-samples t-tests were used to compare the pre-test (N = 37) and post-test (N = 35) cohort means for each AILAS dimension and for the Overall Attitude score. Effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d for independent groups, calculated as the mean difference between cohorts divided by the pooled standard deviation. Consistent with conventional benchmarks, values of 0.20, 0.50 and 0.80 were interpreted as small, medium and large effects, respectively.

- •

- Demographic moderators (RQ1, RQ2): We examined gender differences at each measurement occasion using independent-samples t-tests and additionally tested a time (pre vs. post) × gender interaction using a two-way between-subjects ANOVA (given anonymous, unlinked responses). Academic-level comparisons were descriptive only, given the small number of upper-level students (n = 3). Because responses were unlinked, time was treated as a between-subject factor rather than a within-subject repeated measure.

4. Results

4.1. Participant Characteristics

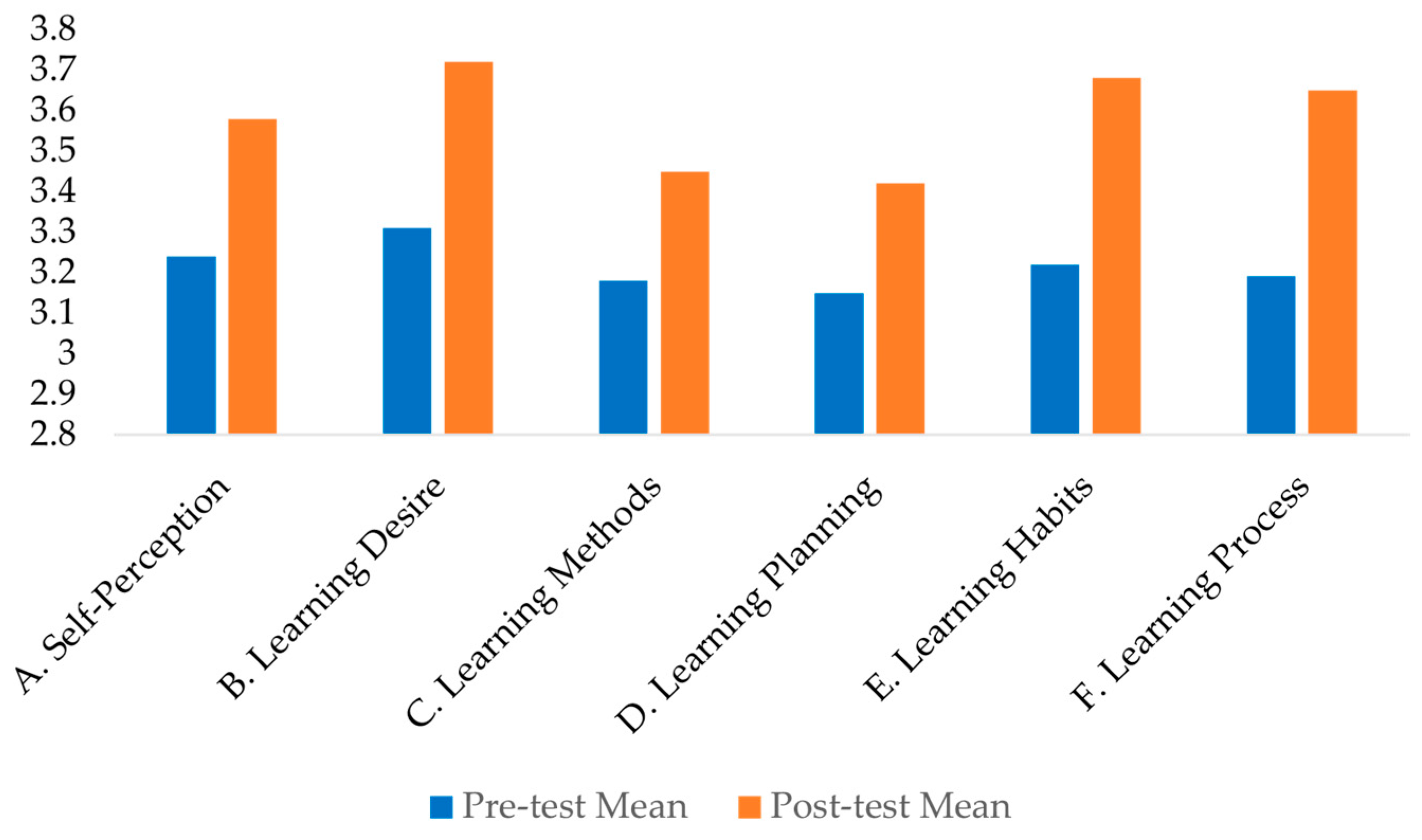

4.2. Intervention Effectiveness: Pre–Post Changes

4.3. Psychometric Robustness: Structural Stability and Item Analysis

Psychometric Properties: Item Analysis

4.4. Demographic Variations

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications: From Motivation to Behavioral Habituation

5.3. Practical Implications for Social Work Educators

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5.5. Conclusion of Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chan, C.K.Y.; Hu, W. Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Weng, X.; Ouyang, F.; Lin, T.J.; Chiu, T.K. A scoping review on how generative artificial intelligence transforms assessment in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kshetri, N.; Hughes, L.; Slade, E.L.; Jeyaraj, A.; Kar, A.K.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Koohang, A.; Raghavan, V.; Ahuja, M.; et al. “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 71, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. Artificial intelligence in higher education: The state of the field. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, D. Open AI in Education, The Responsible and Ethical Use of ChatGPT Towards Lifelong Learning, in FinTech and Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Development: The Role of Smart Technologies in Achieving Development Goals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 387–409. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Garkisch, M.; Goldkind, L. Considering a Unified Model of Artificial Intelligence Enhanced Social Work: A Systematic Review. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work. 2025, 10, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reamer, F.G. Artificial intelligence in social work: Emerging ethical issues. Int. J. Soc. Work. Values Ethics 2023, 20, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Miao, F. Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research; Unesco Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Susnjak, T.; McIntosh, T.R. ChatGPT: The end of online exam integrity? Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.; Tan, S.; Tan, S. ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education? J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K. What is the impact of ChatGPT on education? A rapid review of the literature. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Thierry-Aguilera, R.; Gerardou, F.S. Challenges and opportunities of generative AI for higher education as explained by ChatGPT. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Lal, J.; Liao, A.; Magee, L.; Soldatic, K. Algorithmic decision-making in social work practice and pedagogy: Confronting the competency/critique dilemma. Soc. Work. Educ. 2024, 43, 1552–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Fernández-Cerero, J.; Fernández-Batanero, J.M.; López-Meneses, E. Impact of the implementation of ChatGPT in education: A systematic review. Computers 2023, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boetto, H. Artificial Intelligence in Social Work: An EPIC Model for Practice. Aust. Soc. Work. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A. To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 32, 5142–5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hwang, J.; Kim, T.; Choi, M.; Lee, D.; Ko, J. Impact of generative artificial intelligence on learning: Scaffolding strategies and self-directed learning perspectives. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Sha, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Martinez-Maldonado, R.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Jin, Y.; Gašević, D. Practical and ethical challenges of large language models in education: A systematic scoping review. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, H.; Ahn, S.; Lee, J. A competency framework for AI literacy: Variations by different learner groups and an implied learning pathway. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, 2146–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearman, M.; Ajjawi, R. Learning to work with the black box: Pedagogy for a world with artificial intelligence. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 54, 1160–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, K.J. Paying the Cognitive Debt: An Experiential Learning Framework for Integrating AI in Social Work Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Shehata, B.; Adarkwah, M.A.; Bozkurt, A.; Hickey, D.T.; Huang, R.; Agyemang, B. What if the devil is my guardian angel: ChatGPT as a case study of using chatbots in education. Smart Learn. Environ. 2023, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Xiao, J.; Lambert, S.; Pazurek, A.; Crompton, H.; Koseoglu, S.; Farrow, R.; Bond, M.; Nerantzi, C.; Honeychurch, S.; et al. Speculative futures on ChatGPT and generative artificial intelligence (AI): A collective reflection from the educational landscape. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2023, 18, 53–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T. Factors influencing teachers’ intention to use technology: Model development and test. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 2432–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use and User Acceptance of Information Technology; MIS Quarterly: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E. A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Pract. 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollick, E.; Mollick, L. Assigning AI: Seven approaches for students, with prompts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.10052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Business Machines Corporation. Statistics for Windows, version 25.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017.

- Kasneci, E.; Sessler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; et al. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K. The impact of Generative AI (GenAI) on practices, policies and research direction in education: A case of ChatGPT and Midjourney. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 32, 6187–6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.R.; Cotton, P.A.; Shipway, J.R. Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2024, 61, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theory | Key Constructs | AILAS Dimensions Informed |

|---|---|---|

| Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [28] | Perceived usefulness; perceived ease of use; behavioral intention | A (Self-Perception) F (Learning Process) |

| Attitude Theory/Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [29] | Cognition–affect–behavior structure; perceived behavioral control | B (Learning Desire) F (Learning Process) |

| Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) [30,31] | Forethought–performance–self-reflection cycle; metacognitive strategies; goal-directed regulation | C (Learning Methods) D (Learning Planning) E (Learning Habits) |

| Characteristic | Pre-Test (N = 37) | Post-Test (N = 35) | Characteristic | Pre-Test (N = 37) | Post-Test (N = 35) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Grade Level | ||||

| Male | 15 (40.5%) | 13 (37.1%) | Year 1 | 34 | 32 |

| Female | 22 (59.5%) | 22 (62.9%) | Year 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Department | Year 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Social Work | 35 | 34 | Other/Unknown | 1 | 0 |

| Other/Unknown | 2 | 1 |

| Dimension | Pre-Test M (SD) | Post-Test M (SD) | M Diff | 95% CI [Lower, Upper] | t Value | p | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Self-Perception | 3.24 (0.61) | 3.58 (0.54) | +0.34 | [0.06, 0.62] | −2.45 | 0.017 * | 0.59 |

| B. Learning Desire | 3.31 (0.64) | 3.72 (0.55) | +0.41 | [0.13, 0.69] | −2.88 | 0.005 ** | 0.69 |

| C. Learning Methods | 3.18 (0.58) | 3.45 (0.56) | +0.27 | [−0.01, 0.54] | −1.95 | 0.055 | 0.47 |

| D. Learning Planning | 3.15 (0.65) | 3.42 (0.53) | +0.27 | [−0.02, 0.55] | −1.88 | 0.064 | 0.46 |

| E. Learning Habits | 3.22 (0.66) | 3.68 (0.56) | +0.46 | [0.16, 0.76] | −3.10 | 0.003 ** | 0.75 |

| F. Learning Process | 3.19 (0.64) | 3.65 (0.52) | +0.46 | [0.18, 0.74] | −3.25 | 0.002 ** | 0.79 |

| Overall Attitude | 3.21 (0.55) | 3.58 (0.43) | +0.37 | [0.13, 0.61] | −3.12 | 0.003 ** | 0.75 |

| Dimension Pair (Theoretical Path) | Pre-Test r | Post-Test r | Difference (Δ) | Stability Status (|Δ| ≤ 0.10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAM Path: A (Self-Perception)-F (Process) | 0.65 | 0.68 | +0.03 | Stable |

| TPB Path: B (Learning Desire)-F (Process) | 0.72 | 0.75 | +0.03 | Stable |

| SRL Path: C (Learning Methods)-D (Planning) | 0.62 | 0.60 | −0.02 | Stable |

| SRL Path: C (Learning Methods)-E (Habits) | 0.58 | 0.65 | +0.07 | Stable |

| SRL Path: D (Learning Planning)-E (Habits) | 0.68 | 0.80 | +0.12 | Slightly above threshold |

| SRL Path: E (Learning Habits)-F (Process) | 0.61 | 0.66 | +0.05 | Stable |

| Item | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|

| D1: AI learning is not helpful (Reverse). | 0.08 | 0.66 |

| D2: Study schedule. | 0.42 | 0.54 |

| D3: Improving after poor results. | 0.48 | 0.51 |

| D4: Plan to study daily. | 0.55 | 0.48 |

| D5: Stick to plan regardless of mood. | 0.51 | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, D.-H.; Wang, Y.-C. Bridging the Engagement–Regulation Gap: A Longitudinal Evaluation of AI-Enhanced Learning Attitudes in Social Work Education. Information 2026, 17, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010107

Huang D-H, Wang Y-C. Bridging the Engagement–Regulation Gap: A Longitudinal Evaluation of AI-Enhanced Learning Attitudes in Social Work Education. Information. 2026; 17(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Duen-Huang, and Yu-Cheng Wang. 2026. "Bridging the Engagement–Regulation Gap: A Longitudinal Evaluation of AI-Enhanced Learning Attitudes in Social Work Education" Information 17, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010107

APA StyleHuang, D.-H., & Wang, Y.-C. (2026). Bridging the Engagement–Regulation Gap: A Longitudinal Evaluation of AI-Enhanced Learning Attitudes in Social Work Education. Information, 17(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010107