Balancing Business, IT, and Human Capital: RPA Integration and Governance Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What is the impact of RPA governance on the dynamic interrelationships among Business, IT, and People, in conjunction with audit practices and organizational policies within organizations?

2. Background

2.1. Definition and Scope of Robotic Process Automation

2.2. Case Studies and Industrial Adoption

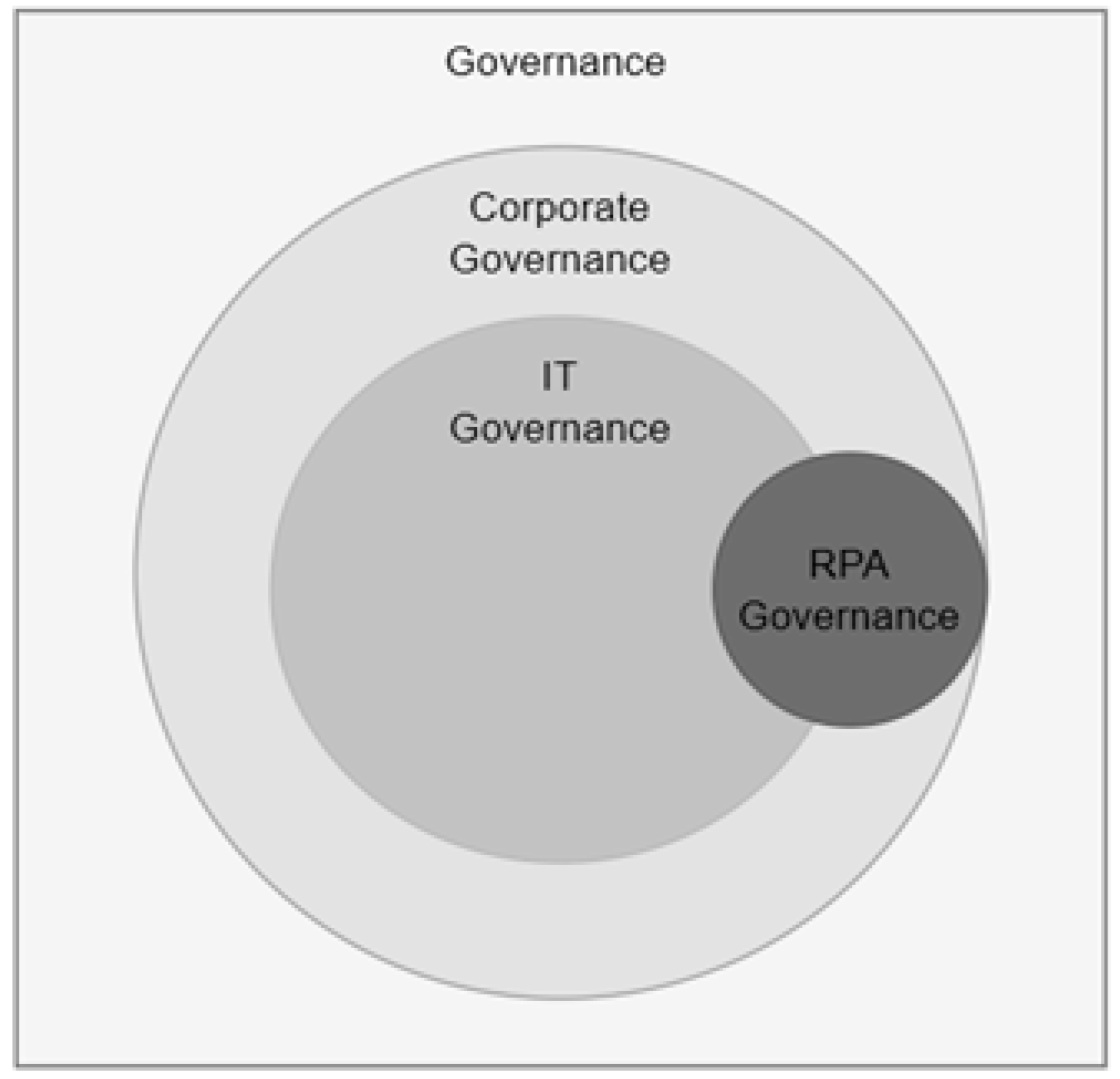

2.3. Governance Models in RPA

2.3.1. Governance–Management Perspective

2.3.2. Corporate Governance

2.3.3. IT Governance

- Value Delivery: This domain concentrates on the efficient provision of IT advantages to other functional areas within the organization.

- Risk Management: This facet is dedicated to the systematic identification, communication, and judicious mitigation of risks associated with IT operations.

- Strategic Alignment: This domain scrutinizes the congruence between the objectives delineated by the IT function and those of the broader organizational framework.

- Resource Management: This area is centered on the appraisal of the appropriate and effective management of IT resources.

- Performance Management: This domain is concerned with the assessment of the efficacy and proficiency in which IT operations are executed.

3. Study Design (Mixed-Methods Overview)

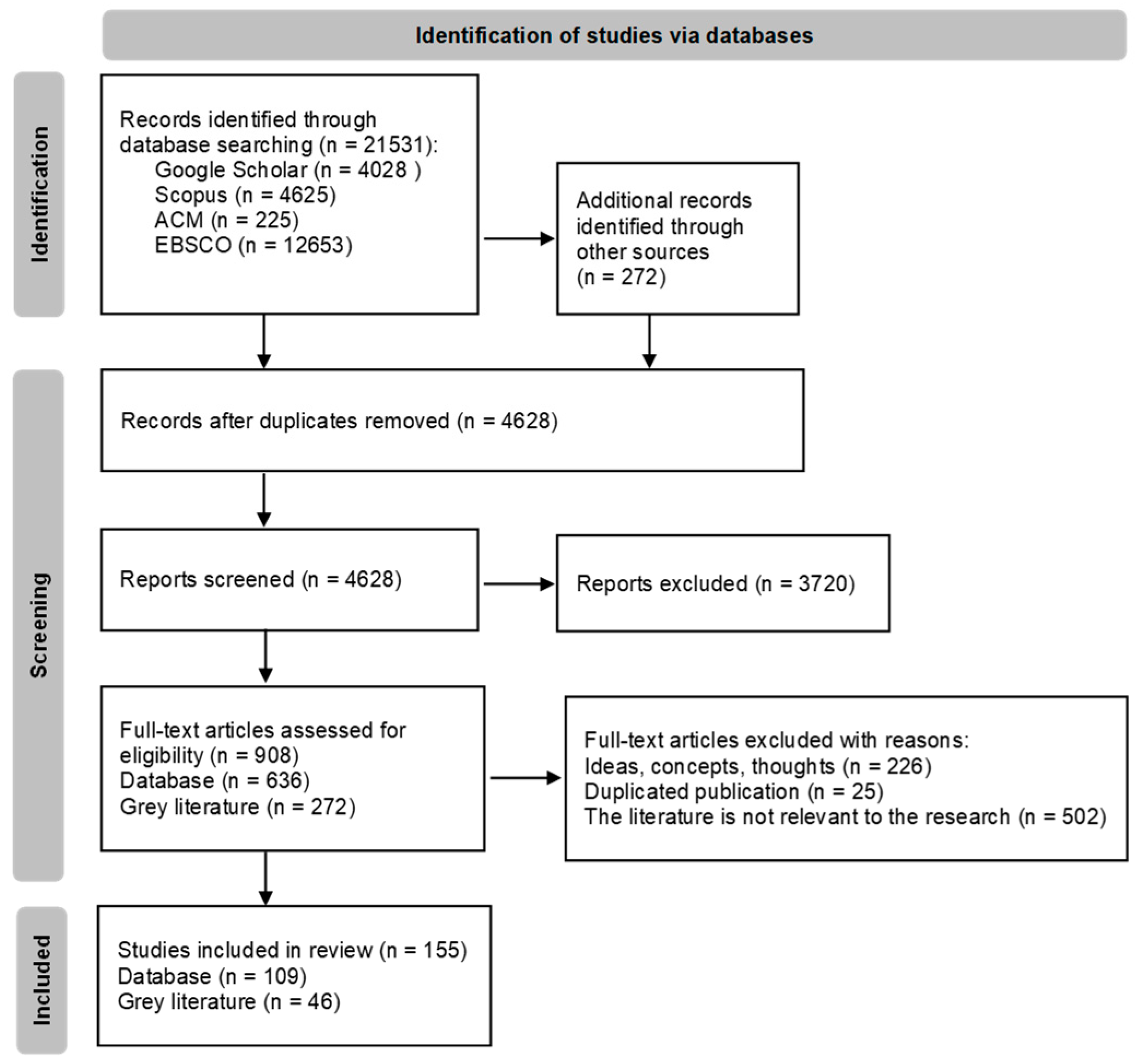

3.1. Phase I—PRISMA-Guided Multivocal Review

3.1.1. Data Sources and Searches

- ACM Digital Library (https://dl.acm.org);

- Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/home.uri);

- EBSCO Information Services (http://search.ebscohost.com/);

- Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/);

- Google Search (https://www.google.com/).

3.1.2. Selection of Studies

3.1.3. Study Selection and Exclusions

3.2. Phase II—Qualitative Interviews

3.2.1. Sampling and Participants

3.2.2. Data Collection Process

3.2.3. Analysis & Trustworthiness

3.2.4. Ethics

4. Multivocal Literature Review

- Interrogate the correlation between RPA governance and its integration with Business, IT, and Human Resources, while also elucidating its interface with audit protocols and organizational policies as evidenced in the scrutinized documents.

- Clearly define the research objectives to guide subsequent analysis.

- Disseminate the identified challenges, opportunities, and results, highlighting their relevance and applicability for both researchers and practitioners in the fields of governance and Robotic Process Automation (RPA).

- Discerning the imperative for conducting an MLR on the specific subject matter.

- Formulating the overarching objective and delineating research questions (RQs) to guide the MLR.

- The subsequent phase, “Conducting the MLR”, encompasses five distinct sub-stages:

- Search and Selection: This involves the formulation of a set of keywords that encapsulate the primary objectives of the study.

- Quality Assessment: It entails the critical evaluation of the credibility and objectivity of selected sources.

- Data Extraction: This step involves the retrieval of pertinent data from the identified studies.

- Data Synthesis: Here, the collated data is combined and analyzed in a manner that facilitates the comprehensive addressing of the research question(s).

4.1. Planning the MLR

4.2. Conducting the MLR

4.3. Reporting the MLR

- Viability and Scalability: These areas address investment evaluation, resource allocation, and cost assessment, while also ensuring that RPA systems can expand and adapt in tandem with organizational growth [10,11,24,68,73,79,81,89,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119].

4.3.1. Integration Between Business and IT

4.3.2. Standardization of Processes

4.3.3. Compliance and Risk Management

4.3.4. Employee Engagement, Changes in Roles, Responsibilities, and Change Management

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Findings from Phase I—Systematic Review

5.2. Findings from Phase II—Qualitative Interviews

- Q1: “Do you think that there should be integration between business and IT?”

- Alignment of Goals: Participants noted that achieving organizational objectives like cost reduction and improved efficiency requires that both business and IT share a clear understanding of priorities. As one interviewee explained, “If IT doesn’t understand what the business needs, automation efforts will miss the mark. Alignment is not optional—it’s critical.”

- Process Quality: Collaboration was seen as essential for identifying process failures early and designing effective solutions. A business analyst mentioned, “We know the customer expectations and planning requirements; IT brings the technical know-how to handle exceptions. Without working together, processes break down.”

- Error Reduction: Interviewees pointed out that business teams’ deep process knowledge complements IT technical expertise to prevent errors and redundancies. For example, an RPA developer shared, “When business and IT collaborate, we catch potential errors before deployment, which saves time and avoids costly fixes.”

- Communication: Effective and ongoing communication was emphasized to ensure shared understanding and timely error resolution. As one manager stated, “Open communication channels between business and IT mean problems get identified and fixed quickly, keeping projects on track.”

- Definition of Responsibilities: Clearly delineated roles prevent misunderstandings and facilitate smooth change management. One interviewee noted, “When responsibilities aren’t clear, people step on each other’s toes. Involving both sides in process changes avoids surprises.”

- Documentation: Comprehensive documentation was described as a vital tool for transparency and process control. A participant explained, “Good documentation helps everyone—from business to IT—stay on the same page about what the process does and how changes should be made.”

- Q2: “Do you think there could be issues if the process is solely defined by the business side or solely by the IT side without following a standard?”

- Knowledge Limitations: Participants noted that relying solely on one side risks critical gaps in understanding. As one interviewee explained, “When business defines the process without IT’s input, technical constraints and integration challenges are often overlooked. Conversely, IT-only designs can miss important business rules.”

- Errors: Several respondents described how insufficient collaboration leads to errors, citing examples of overlooked requirements or inadequate testing. A developer commented, “Errors creep in when one side assumes the other has covered certain aspects. This causes rework and delays.”

- Ambiguity: Interviewees warned that processes crafted by a single party often introduce ambiguity that complicates implementation. As a business analyst stated, “Without shared understanding and standards, process steps can be interpreted differently by teams, leading to inconsistent results.”

- Resource Wastage: The risk of wasted time, effort, and budget was commonly mentioned. For instance, one manager shared, “We’ve seen robots deployed based on incomplete processes that failed to deliver value, wasting resources that could have been avoided with joint planning.”

- Overload: Several highlighted how the lack of collaboration places an unfair burden on either business or IT, causing inefficiencies. A participant noted, “If one side handles everything, they get overloaded and bottlenecks appear, slowing down the whole project.”

- Misalignment of Objectives: The importance of aligning goals was emphasized by all interviewees. One said, “Synchronization ensures we use all expertise effectively. Without it, critical perspectives are missed and the process falters.”

- Q3: “From your perspective, what is the meaning of careful selection of processes to be automated in RPA?”

- Efficiency: Selecting the right processes for automation is crucial to saving resources such as time and money. Processes that are repetitive and rule-based are particularly suitable.

- Error Minimization: Processes that generate frequent known errors can benefit from RPA implementation, as it can reduce execution time and mitigate errors.

- Stability: When choosing a process for automation, stability of the programs used by the robot is paramount. Ensuring that requirements and rules are well-understood, alongside technical stability, is essential for successful automation.

- Viability: An in-depth analysis should be conducted to determine if automation makes sense for each process, factoring in factors like expected return, implementation cost, maintenance, time, and effort. The focus should be on quality rather than volume, as choosing the wrong processes can lead to resource loss.

“Choosing the right process is not about how many you automate, but about which ones will actually deliver value without causing new problems.”

“We focus on stable, rule-based workflows because robots can only perform well when the rules are clear and the environment is predictable.”

“Stability and auditability matter as much as ROI—if screens or rules change every month, you don’t have a good RPA candidate,” noted one RPA lead.

- Q4: “As there are no taxes on robots, but there are many on people, if you were a company owner, would you prefer to retain and prioritize people over replacing them with robots for economic reasons?”

“Robots don’t get tired or distracted, so they’re perfect for repetitive work—but people are still needed for the complex decisions.”

“It’s not about replacing people, but about freeing them to focus on tasks where their expertise really matters.”

- Time Reduction: RPA can operate around the clock, significantly reducing process execution time compared to human counterparts.

- Mitigating Human Error: Robots operate based on rules, minimizing the potential for human error caused by factors such as lack of concentration or inadequate process understanding.

- Profit and Efficiency: the RPA ability to handle large volumes of information quickly can lead to increased efficiency, reduced errors, and ultimately, higher profits.

- Essential Collaboration: Certain employees play pivotal roles in processes that require human intervention, such as analysis or maintenance.

- Reallocation: Employees can be reallocated to roles demanding critical thinking and analysis, with appropriate training to equip them for these functions.

- Cost Reduction: Both the continuous operation of robots and the potential reduction in personnel can lead to cost savings, encompassing salaries, healthcare expenses, and taxes.

- Q5: “Do you think RPA helps or replaces employees?”

“RPA frees people from the mundane so they can focus on what machines can’t do—thinking and problem-solving.”

“When done right, automation doesn’t cut jobs; it changes them.”

- Q6: “Do you believe that all individuals involved in the same project should have the same levels of permissions?”

- Q7: “In your opinion, is understanding and preparing employees important for reducing compliance risks in RPA?”

- Training and Awareness: Employees need comprehensive knowledge of business operations, regulations, data handling, roles, responsibilities, and associated risks.

- Motivation: Understanding the real-world impact of processes can motivate employees to maintain a broad organizational perspective and exhibit conscientiousness.

- Risks and Impacts: Unprepared employees, with limited experience, may inadvertently introduce errors, potentially leading to the compromise of confidential data.

- Creating an environment of awareness and accountability within an organization is deemed instrumental in minimizing compliance risks, enhancing the likelihood of successful RPA implementations, and safeguarding sensitive data.

“When employees truly understand the why and how behind RPA, they’re more careful and aligned with compliance goals,” noted one participant.

“Training isn’t just a checkbox; it’s what keeps the process safe and effective,” emphasized another interviewee.

Practical Implications Based on Interview Findings

5.3. Integration/Triangulation of Findings

6. Conclusions

6.1. Emerging Trajectory

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| # | Q1-Do You Think That There Should Be Integration Between Business and IT? |

|---|---|

| 1 | The interviewee spoke about the importance of the union between business and IT because each one has a type of responsibility and expertise. |

| 2 | The combination of IT and Business can optimize the way business is done when compared to traditional business. |

| 3 | Process should be improved collaboratively by the IT and business for greater efficiency and success. |

| 4 | There should be a balance so that both areas can contribute their specialties, increasing the quality of processes, and aiding in standardization and knowledge transfer through documentation. |

| 5 | IT is a mean to achieve business goals. So, those two sectors must be integrated, somehow. |

| 6 | Integration between the two areas is crucial as they complement each other. The business is vital in identifying processes and monitoring them, while the IT area is better suited for implementing solutions and solving technical issues. |

| 7 | An organization where IT and business strategy are integrated can improve agility and operational efficiencies while also enterprises function better, make more profit and hit their goals with less effort. |

| 8 | Working together could reduce costs, align goals and promote process improvement |

| 9 | Important because if it’s only in IT and separate from the business, it won’t address the organization as a whole; it will be from a single perspective. |

| 10 | The best way would be to come together for process understanding and follow-up when it goes into production. |

| 11 | It’s important because it bridges the languages of business and IT, which are different, and this translation of language is crucial for correct interpretation. |

| 12 | Certainly, the connection is critical; if there isn’t that connection between the two, it can generate many risks for the organization, not just financial risks. |

| 13 | Collaboration between these two functions is very important for reasons such as alignment of objectives and effectiveness. |

| 14 | With the help of IT, the improvement and facilitation of many business processes can be achieved. |

| 15 | I know of a department that created their own robots without specialized employees, resulting in poor development and maintenance difficulties, which can harm the institution. |

| 16 | I think one doesn’t exist without the other; you need the business part well defined first, and then you can have software that works well. |

| 17 | There should always be communication between the two; otherwise, it can go wrong for both sides. |

| 18 | The business understands more about the business rules, while IT is more focused on the technical aspects. |

| 19 | That’s exactly what prevents errors because there is the person who develops the process and the person from the business who understands the day-to-day work to be executed. |

| 20 | One evolves with the other; if the business part doesn’t work well, technology cannot execute. |

| 21 | It’s important that the department also has some understanding of how the processes to be automated work in order to communicate effectively with those handling the technical aspects. |

| 22 | Collaboration between the two areas is essential, as well as clear alignment, communication, and well-defined roles and responsibilities. |

| 23 | Collaboration is necessary; those who will develop lack knowledge in the business area, and vice versa. |

| 24 | I believe that the business and IT should maintain unity, as I think it would optimize time, service, and contribute to the product’s quality. |

| 25 | Both sides bring something valuable to the process. On one hand, there’s business knowledge, and on the other, technical knowledge. Robots work better when both are present. |

| 26 | Collaboration between the two is important, and there should be alignment so they can work together and avoid conflicts of interest. |

| 27 | Integration between the business and IT is important because it streamlines the work of both, reducing time as each is an expert in their respective areas, and it decreases costs by preventing errors. |

| 28 | The business needs to focus on the analysis and process documentation, while IT should handle the development and maintenance of those processes. |

| 29 | Each one plays their part in the area they know best: the business side analyzes and documents processes, while IT develops, aiding in organization and preventing overload. |

| 30 | Working together, the goals are more likely to be achieved, and the union of these two areas will combine their respective strengths. |

| 31 | It’s important to always have a bridge between the two areas for better understanding of the contexts each part executes. It’s also essential to have someone who understands both sides to facilitate the connection between them. |

| # | Q2-Do You Think There Could Be Issues If the Process Is Solely Defined by the Business Side or Solely by the IT Side Without Following a Standard? |

| 1 | In agreement with the previous response, if each department works within its specialization, it will decrease the likelihood of errors and consequently losses to the organization. |

| 2 | The business knows how the process works and the IT knows how to implement. One without the other could lead to errors in the process or non-ideal scenarios. |

| 3 | The lack of collaboration between these areas can result in unnecessary resource expenditure due to misalignment of objectives or even a lack of necessary knowledge. |

| 4 | If the process is solely defined and executed by one of the departments, errors can be made, and collaboration between them is crucial to ensure everything progresses smoothly. |

| 5 | The business side must consider IT potentialities and limitations as well the IT side must know what the business goals are to focus on delivering what is required. |

| 6 | IT may need the business due to a lack of sufficient knowledge in the business area, and the business may need IT to overcome technical issues. |

| 7 | The lack of standard processes involving both areas can lead to unmet business expectations. |

| 8 | It is essential that both sides work together, follow determined processes and communicate well, to ensure that initiatives generate value for the organization. |

| 9 | Yes, because they wouldn’t address the topics comprehensively. |

| 10 | There is a lack of technology knowledge, especially for maintenance if it’s done solely by the business, and if done solely by IT, there would be a lack of business knowledge for automation. |

| 11 | If it were done by the business, they probably wouldn’t be implemented efficiently, and if it were done by IT, the business details wouldn’t be considered. |

| 12 | All the problems, primarily a waste of time and money. |

| 13 | Problems such as lack of standards, lack of alignment of objectives and inefficiency may arise. |

| 14 | It should never be defined by just one party. The business should define rules and provide examples of how the process is done manually, and IT will assess the feasibility and suggest possible step-by-step improvements. |

| 15 | The business side doesn’t understand the technical aspects, and IT doesn’t know how to gather requirements or manage processes. |

| 16 | The robot might not be useful in the end; it might not solve the business problem if it wasn’t well-defined from the beginning or executed well. |

| 17 | A businessperson may have an easier time understanding and communicating with the client, while a developer has more knowledge of what can be done at the code level. |

| 18 | It would be much more difficult to reach the end goal as the number of processes scales up. |

| 19 | Yes, because each person has knowledge of their part, that’s why there should be a union between the two. |

| 20 | The person who writes the process knows about the business logic and not about the execution part, and vice versa. |

| 21 | On the IT side, people may not have a complete understanding of the process, and on the business side, they may not have a complete understanding of the tools. |

| 22 | The combination of both areas is an asset, merging business knowledge with IT expertise. |

| 23 | IT may not know how to gather the process correctly, and the business side may not develop as efficiently. |

| 24 | IT without full knowledge of the business and the business without full knowledge of IT could lead to a series of errors. |

| 25 | If only IT handles everything, the business knowledge will be missing, and if it’s solely the business side handling it, they might not do it as efficiently, potentially not saving the money and time intended. |

| 26 | The business side wouldn’t be able to provide the necessary maintenance and effective development, whereas the IT side may not understand the business’s gains and losses. Each area has its focus, and their union is ideal. |

| 27 | There needs to be unity so that the IT department can complement the knowledge of the business area. |

| 28 | The business may not possess as much technical knowledge, which could lead to errors or process inefficiencies. Conversely, a developer without business knowledge would struggle to analyze the necessary or unnecessary steps in building a process. |

| 29 | Overloading, as the business may not know how to develop and maintain processes, and IT may not understand the business enough, leading to future problems. |

| 30 | It can bring problems like a lack of specialized knowledge, which can translate into significant business impacts. |

| 31 | Handling processes individually can lead to limited knowledge, a lack of effective documentation, and communication with the potential for negative impacts. |

| # | Q3-From Your Perspective, What Is the Meaning of Careful Selection of Processes to be Automated in RPA? |

| 1 | Processes that don’t require human critical thinking and accurate choices save time and money. |

| 2 | Processes need to be repetitive for maximum optimization, and making the wrong choice can lead to future losses. |

| 3 | A process should have well-defined rules and minimal changes to prevent discontinuation or resource losses in the future. |

| 4 | RPA processes should be the ones where tasks are repetitive and follow a specific standard that is not being altered very often. |

| 5 | Prioritizing the right processes ensures that RPA implementation delivers the desired benefits while minimizing potential risks and challenges. |

| 6 | The processes to be selected should add value to the company, based on well-defined and repetitive rules. |

| 7 | Carefully check the complexity, stability, scalability and importance of the process. |

| 8 | Thorough analysis to select processes in line with the organization’s objectives and suitable for automation, thereby increasing the likelihood of success and financial return. |

| 9 | If the right process selection is not made, there can be a loss of time in implementation, and maintenance ends up with higher costs and a greater risk of poor results. |

| 10 | The risk is to continue having people with repetitive tasks and automating processes that don’t need it. Sometimes there is too much concern about the volume of automation and not enough focus on quality. |

| 11 | Processes should always have a hierarchy and consider profitability. FTEs means people are reallocated and not fired, and in FSTS cost reduction or elimination should be prioritized. |

| 12 | Adding value, a good selection increases the added value to the organization, and a poor selection is a waste. |

| 13 | Can significantly impact the success and efficiency of an implementation. |

| 14 | Automating daily and repetitive processes should involve analyzing the cost of automation, including licenses and infrastructure, when choosing a process. It’s essential to balance the benefits of automation with the required investment. |

| 15 | It’s very important because there are things that can meet customer expectations and others that can’t, and this analysis and realism are necessary in this regard. |

| 16 | It’s what solves the problem; it’s better to invest in processes that can contribute than in processes that don’t save as much work. |

| 17 | There should be attention in the process selection; it should be a process that saves someone’s time, which can be used for more critical tasks. |

| 18 | It depends on whether the development is feasible, feasibility analysis is one of the key aspects of a process. If not done correctly, it can lead to overspending of resources. |

| 19 | Time savings, fewer errors, reduced costs, and consequently, having time for other activities that require greater human intelligence. |

| 20 | The wrong choice can generate costs, loss of time, and labor. |

| 21 | This can lead to application errors, business errors, data non-conformity errors; the processing can be done incorrectly, resulting in an unexpected outcome. |

| 22 | Loss of time, money, and resources. A process that won’t yield returns is a detriment to the organization, impacting both its reputation and finances. |

| 23 | The choice of processes to be automated is those that bring time and cost savings to the organization. |

| 24 | If a process is not chosen carefully, it may lack data and knowledge about the process, which can result in a loss of time, money, and other resources. |

| 25 | They should have certain characteristics such as being repetitive and having as few special exceptions as possible to avoid resource loss. |

| 26 | If the choice is not made carefully, it can result in the loss of money and time. If the goal is to reduce time spent on repetitive tasks, selecting the wrong processes can hinder achieving that objective. |

| 27 | It can lead to errors, unnecessary time and money spent because not every process is feasible to automate. Some processes may not be repetitive, or the economic benefit for the organization may not justify automation. |

| 28 | It’s essential to choose what truly needs to be automated, as otherwise, it could be discontinued for various reasons. |

| 29 | It can have an impact because the robot may not be able to do what the business requires, which can affect other areas that depend on correct execution. |

| 30 | There should be stability in the process to be automated, it must be a well-structured process, using stable applications, and estimating and analyzing the impact in terms of resource allocation is crucial. |

| 31 | The choice of a process should consider the benefits to the organization, the cost of execution, and the time saved. |

| # | Q4-Since There Are no Taxes on Robots, But There Are Many on People, If You Were a Business Owner, Would You Prefer to Retain and Prioritize People Over Replacing Them with Robots for Economic Reasons? |

| 1 | I would prioritize the implementation of RPA, reducing process time, increasing profits, and lowering various unnecessary costs while retaining essential employees and reallocating others. |

| 2 | It mainly depends on the task. If the task is repetitive, the robot is perfect. But if there are exceptions, the human does it better. |

| 3 | Robots would perform the work more efficiently and quickly, but can fail, so human oversight is necessary. |

| 4 | People must be present to maintain the robots and people offer certain skills that robots cannot mimic. |

| 5 | We live in a competitive market so reducing costs without losing quality is mandatory to “survive”. |

| 6 | I’d prefer robots, not only for economic reasons but also due to their greater efficiency compared to humans and I’d adapt employees to new roles integrated with RPAs. |

| 7 | This means RPA would replace humans and many would be out of a job, but as a business owner everything is a transaction so I would try to save as much money as possible. |

| 8 | People need to be present to maintain the robots, and people offer specific skills that robots cannot mimic. Robots can be present in repetitive tasks, reducing possible human errors. |

| 9 | Economically, I would choose to replace people, but in other aspects, there is the analysis and evaluation of results that must be done by a human. |

| 10 | Prioritize robots, saving money and having everything done the same way, and reallocate the necessary employees to higher-value activities. |

| 11 | But there should always be a human foundation. |

| 12 | It’s not about paying taxes; humans should add value and not be engaged in repetitive activities. |

| 13 | People are still needed because automatism can generate errors that have to be corrected by a human. |

| 14 | The ideal strategy would be to reduce resources per process instead of replacing them completely. |

| 15 | Economically, I would prefer the robot and hire experienced people to manage it. |

| 16 | For purely economic reasons, I would prioritize robots, but for other issues, a robot wouldn’t replace a human. |

| 17 | I would prioritize robots and keep only the necessary people. |

| 18 | Robots because they are more efficient and competent. |

| 19 | I would prioritize people because I understand that there could be a union between humans and robots, but robots alone wouldn’t be able to complete the work entirely. |

| 20 | I would replace everything possible with robots for repetitive tasks and would place people in roles requiring critical thinking. |

| 21 | If the robots are well-developed, they can work 24 h a day, and the likelihood of errors is lower. The volume of work they can handle is higher than what a human can do, even though it’s still necessary to have humans involved. |

| 22 | Functions can be performed by robots, saving money. However, it is necessary because humans possess critical thinking abilities that robots do not. |

| 23 | Only in functions that can be automated and provide a return, saving time for employees to perform other tasks. |

| 24 | I would prioritize robots because they would lead to more financial gains and select specialized individuals for the management and maintenance of the robots. |

| 25 | I would prioritize people by reallocating them to other tasks and investing in training so that these employees could perform activities requiring critical thinking, while I would keep robots for repetitive tasks. |

| 26 | If RPA was chosen to reduce costs and time, it doesn’t make sense to prioritize or keep people in roles that RPA can perform. People are required for evaluation and execution, especially in case of failures. |

| 27 | Economically, I would prefer to prioritize robots for tasks that can be automated and keep the necessary employees in other roles. |

| 28 | I would prioritize robots because I would want to save money on both salaries and other expenses. The fewer human errors, the greater the financial return for the organization, while people would be assigned to essential functions. |

| 29 | I would prioritize robots for tasks that are time-consuming for humans and keep employees engaged in activities that require human analysis and thinking. |

| 30 | I would prioritize robots for economic reasons, mitigating human error, and exponentially increasing the value added to my company. It would accomplish the same work while reducing costs related to human labor, including salaries, healthcare expenses, taxes, and saving time. |

| 31 | I would prioritize people, using robots for repetitive tasks and reallocating individuals. If the company’s goal is to expand, there are always tasks for people to do. It’s important to assess medium and long-term objectives, provide training for people who will be reallocated, and prepare them for this transition. |

| # | Q5-Do You Think RPA Helps or Replaces Employees? |

| 1 | Depending on the company’s objectives, it can either replace people or assist with the workload of others. |

| 2 | It helps as it reduces repetitive workload from employees. |

| 3 | RPAs help people by handling the most tedious tasks at work and completing certain steps much faster than humans can. |

| 4 | It doesn’t fully replace them, but it definitely helps them. |

| 5 | If an employee or a group of employees are only performing tasks that could be fully automated, the company has the choice to reassign the attributions of that employee or dismiss them, totally or partially. |

| 6 | They help workers by freeing up humans for more analytical and higher-value tasks in the company. |

| 7 | RPA is here to replace tedious and repetitive tasks that humans have. It mimics human behavior without the human errors while the performance is also better. |

| 8 | If implemented correctly, it can increase employee satisfaction by allowing them to focus on tasks that generate more value. Therefore, RPA, along with a human touch, can be the key to a higher likelihood of process success. |

| 9 | If they are small, repetitive processes, it replaces tasks and not people, activities without the need for analysis. |

| 10 | RPA helps with the most repetitive parts, and people focus on what generates value. |

| 11 | It helps with replacements but also aids in maintaining tasks that couldn’t be ensured because the number of hires decreases while tasks do not. |

| 12 | It helps humans with repetitive activities. It can free up those at the end of their careers for retirement, but the intention is to complement or free up for other activities. |

| 13 | It helps because people are still necessary; robots can generate errors that need to be corrected by human hands. |

| 14 | We can’t claim that we’re always helping or always replacing; it’s usually a combination of both. It all depends on the perspective and how they are implemented. |

| 15 | It replaces, some RPAs can replace an entire department, and people are not always reallocated. |

| 16 | It helps more than it replaces, but in some cases, it does replace when the work is repetitive and doesn’t require creativity and critical thinking, and there is no possibility of reallocation. |

| 17 | It helps because employees can move to more important roles. |

| 18 | In most cases, it helps people with significant roles rather than those with repetitive tasks. |

| 19 | It helps the employees because it optimizes time and reduces costs. |

| 20 | It helps the employees because it is essential for optimizing time and resources. People should be placed in non-repetitive areas and in critical areas that require human thinking. |

| 21 | Human knowledge about the process is essential, as is human intervention for development and maintenance. |

| 22 | They help; robots don’t replace human analysis. However, people aren’t always reassigned, it depends on the company’s plan, and it can hinder the knowledge transfer for RPA development. |

| 23 | They help employees have more time to engage in more important activities. |

| 24 | It aids people by replacing repetitive tasks, requiring individuals to specialize in handling tasks that involve critical thinking. |

| 25 | It helps because it allows employees to focus on tasks that require critical thinking, while robots are used for more repetitive tasks. |

| 26 | Helps essential personnel and replace individuals in mechanical roles that don’t require human reasoning because it doesn’t always make sense to relocate these individuals to other functions. |

| 27 | It can replace tasks that can be fully automated and can assist individuals in roles requiring analytical thinking. |

| 28 | It helps with repetitive processes and replaces humans in functions where they are not necessary. |

| 29 | It helps employees by freeing them from repetitive tasks so they can focus on other things. |

| 30 | I believe RPA helps people by relieving them of a lot of repetitive tasks and replacing employees who are no longer needed. |

| 31 | It helps employees in repetitive activities. |

| # | Q6-Do You Believe That All Individuals Involved in the Same Project Should Have the Same Levels of Permissions? |

| 1 | There should be project management, and accesses should be requested and granted based on each collaborator’s responsibilities. |

| 2 | Security. A developer should not have access to financial records as it could be a breach in security. |

| 3 | Each person should have the appropriate permissions for their role and the tasks they need to perform. |

| 4 | There are confidential and sensitive data that should only be accessed by whoever is needed. |

| 5 | Is important to protect business from data breaches or unauthorized changes. |

| 6 | There must be different permission levels due to data confidentiality issues and project vulnerabilities. |

| 7 | I believe they should have the level of permission of the job category they are currently performing to avoid confidentiality risks, for example. |

| 8 | Increased security, risk minimization, and role-based hierarchy are crucial as not all individuals require the same levels of access. |

| 9 | There are confidential data and each person’s seniority to consider. Very junior employees don’t need access to confidential information. |

| 10 | It should be segmented to eliminate risks. |

| 11 | They should be segmented according to functions, but there can be a person with access to everything. |

| 12 | Not everyone, needs to be a mix of experiences and responsibilities. |

| 13 | Having different levels of permissions and access rights can be a critical aspect of security and management. |

| 14 | I don’t think all individuals on a project should have the same permissions, but there should be autonomy to fully carry out our work. |

| 15 | Should be a hierarchy; a junior should not have the same level as a senior who has a certain level of trust from the client. |

| 16 | Difficult to manage due to security reasons. Access should be based on each employee’s responsibility. |

| 17 | There must be a hierarchy; people with more knowledge have higher levels of access. |

| 18 | No, for data security, access levels must be well-defined. |

| 19 | There are people with less knowledge than others, there needs to be a hierarchy. |

| 20 | There should be a hierarchy for direction; a junior doesn’t reason like a senior and doesn’t know the risks and processes. Knowledge is necessary for decision-making. |

| 21 | People may not always have access to all the information. |

| 22 | It’s challenging to manage and analyze everything; however, it can hinder the speed and efficiency of the process. |

| 23 | Considering that processes involve confidential data, access should be limited according to the hierarchy. |

| 24 | People should only access what they need to know, limiting it to the area in which they specialize according to their responsibilities. |

| 25 | I believe so because it streamlines the work and eliminates the wait for permissions, always with supervision, regulation, and data encryption. |

| 26 | For security reasons, hierarchy must be respected to prevent errors, fraud, and other issues. People without sufficient knowledge and with high levels of permission can have a negative impact on the organization. |

| 27 | There are confidential pieces of information, and a certain level of trustworthiness is necessary to access and handle this type of information. |

| 28 | Because not everyone has the same perception and sensitivity regarding the systems and data used, they may end up making errors that could tarnish the organization’s image, in addition to incurring costs and wasting time. |

| 29 | Because of the levels of responsibility, for example, a junior employee may not have as much knowledge about risks as a senior employee. |

| 30 | Because there should be an assignment of responsibility, and those who hold these responsibilities should be individuals whose roles in the project follow a hierarchy. Additionally, for security reasons, there should be a separation of functions and responsibilities. |

| 31 | For security reasons, and because not everyone applies knowledge in the same way, people should have permissions according to their responsibilities. |

| # | Q7-In Your Opinion, Is Understanding and Preparing Employees Important for Reducing Compliance Risks in RPA? |

| 1 | The knowledge and ongoing training of employees are essential to prevent compliance risks such as regulatory violations, fraud, or data leaks. |

| 2 | It’s always good to prepare employees to deal with anomalies that come from robotic processes, as they would more efficiently respond to what happened. |

| 3 | RPA is a simple technology; however, it can cause significant issues if those who use it lack basic knowledge of the process/technology. |

| 4 | If you are dealing with sensitive data, it is important that people are aware and know how to deal to avoid breaches. |

| 5 | Employees can have insights that help identify risks and address them before they escalate further. |

| 6 | If workers were better informed about the reality of RPAs and even involved in their management, there would be fewer associated operational risks. |

| 7 | It is important in order to protect data integrity, data security, and employee and customer privacy. |

| 8 | Training employees is a fundamental aspect of reducing compliance risks in RPA and data protection. There should be a culture of awareness and responsibility. |

| 9 | This should be part of the onboarding for each project, there should be a framework to understand the risk of actions. |

| 10 | It’s important to be aware of the risks because sometimes tasks are carried out without awareness of the impact. |

| 11 | Training is very important; the structure of RPA, cross-modules, impacts, and risks should be explained. |

| 12 | It’s very important because using robots for operations instead of humans, if there is any damage, it will be faster and on a larger scale. |

| 13 | Understanding and preparing employees is essential, so that they are aware of compliance, risks, and how to deal with them. |

| 14 | It’s an important part of appropriate training according to roles, enabling preparation to face all difficulties, a very important factor in a company’s growth. |

| 15 | Important are trainings, test environments, and permissions, as well as an employee to validate so that when there is an audit, an error is not considered fraud. |

| 16 | To mitigate risks, everyone should be aware. Sensitive data is used, and often, developers may not be aware of what type of data it is and how dangerous it can be. |

| 17 | Employees must be prepared because otherwise, the company is at risk due to poor preparation and understanding. |

| 18 | It’s very important for employees to be more careful when developing and understand the impact it can have. |

| 19 | There should be a lot of awareness of the entire process; people need to understand what each permission can cause. |

| 20 | Everyone must be aware of the risks associated with the process and the tools to be used. Risks should be well understood, and it’s very important to know what one is doing to avoid causing losses to the business. |

| 21 | It’s necessary; people should understand the risks of their actions and the need as well. |

| 22 | It’s essential, it’s important to grasp the business, understand the technology being used, comprehend the access levels, and the purpose of each activity within the process. |

| 23 | So that employees understand and become more proactive in seeking solutions, thereby reducing risks. |

| 24 | Preparation is necessary; employees must understand what they are working on and the risks of their actions to the organization. |

| 25 | it’s very important. It helps to better understand the business, avoiding future constraints, makes the work more direct, and regarding IT, it can even help developers feel more motivated by knowing what they are doing and the impact on people’s daily lives. |

| 26 | Crucial to extract the best from the business and the process. If people are well-trained and comprehend what they are working on, the risks and real-life impact, the chances of errors occurring decrease. |

| 27 | The higher the level of knowledge, the lower the chance of making errors. People should be informed about the risks and benefits of what they are creating and handling. |

| 28 | I find it important both to avoid losses and to help and motivate each employee in their respective roles. |

| 29 | People need to understand the area they are working in, the real-life impact, and the risks. |

| 30 | Employees need to understand what they have access to, the information, and their responsibility to protect and handle that information as sensitive. They should also know how to handle this information to prevent data breaches. |

| 31 | It is necessary because an individual may not know the entire context, but they should understand the risks that execution can bring, including impacts on the company such as a bad reputation and significant losses. |

References

- Cabello Ruiz, R.; Jiménez Ramírez, A.; Escalona Cuaresma, M.J.; González Enríquez, J. Hybridizing humans and robots: An RPA horizon envisaged from the trenches. Comput. Ind. 2022, 138, 103615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, I.; Toll, D.; Melin, U. Automation as a Driver of Digital Transformation in Local Government: Exploring Stakeholder Views on an Automation Initiative in a Swedish Municipality. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Omaha, NE, USA, 9–11 June 2021; pp. 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orynbayeva, A. A Governance Model for Managing Robotics Process Automation (RPA); TU Delft—Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management: Delft, The Netherlands, 2019; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- ALSO. Robotic Process Automation (RPA): Potential for Businesses. Available online: https://www.also.com/ec/cms5/en_6000/6000/company/blog/article/future-technologies/robotic-process-automation-rpa-potential-for-businesses.jsp? (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Boulton, C.; Olavsrud, T. What is RPA? A Revolution in Business Process Automation|CIO. Available online: https://www.cio.com/article/227908/what-is-rpa-robotic-process-automation-explained.html (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Wewerka, J.; Reichert, M. Robotic process automation—A systematic mapping study and classification framework. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2023, 17, 1986862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedziora, D.; Penttinen, E. Governance models for robotic process automation: The case of Nordea Bank. J. Inf. Technol. Teach. Cases 2020, 11, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrast, S.A. Robotic process automation in accounting systems. J. Corp. Account. Financ. 2020, 31, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, J.C.; Pereira, R.F.; Fonseca, M.; Ribeiro, R.; Bianchi, I.S. Advances in auditing and business continuity: A study in financial companies. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Schoop, E.; Nichols, J.; Mahajan, A.; Swearngin, A. From Interaction to Impact: Towards Safer AI Agent Through Understanding and Evaluating Mobile UI Operation Impacts. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, Proceedings IUI, Cagliari, Italy, 24–27 March 2025; pp. 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busboom, J.; Boulus-Rødje, N.; Bødker, S. Tracing Transformations of the Modern Workplace and Imagining its Future. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Symposium on Human-Computer Interaction for Work, CHIWORK 2025, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 23 June 2025; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.C.; Chen, R. Scientific measurement analysis of supply chain risk management. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Engineering, ICAICE 2024, Wuhu, China, 8–10 November 2024; pp. 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.H.; Wang, L. Fintech: How technology can change the way banks expand. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Big Data Economy and Information Management, BDEIM 2024, Xiamen, China, 13–15 December 2024; pp. 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. Research on the Construction of Enterprise Financial Sharing Platform in the Background of Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Conference on Cyber Security, Artificial Intelligence and the Digital Economy, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 7–9 March 2025; pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, I. Ironies of Public Service Automation—Bainbridge Revisited. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, New York, NY, USA, 11–14 July 2023; pp. 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoko, B.L.; Lindawati, A.S.L.; Mustapha, M. Robotic process automation in audit 4.0. In Proceedings of the 2021 12th International Conference on E-business, Management and Economics, ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Beijing, China, 17–19 July 2021; pp. 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Money, W.H. Resolving Pressure and Stress on Governance Models from Robotic Process Automation Technologies. 2020. Available online: https://iscap.us/proceedings/conisar/2021/pdf/5570.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- (Abigail) Parker, C.; Issa, H.; Rozario, A.; Søgaard, J.S. Robotic Process Automation (RPA) Implementation Case Studies in Accounting: A Beginning to End Perspective. 1 November 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4008330 (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Marciniak, P.; Stanisławski, R. Internal Determinants in the Field of RPA Technology Implementation on the Example of Selected Companies in the Context of Industry 4.0 Assumptions. Information 2021, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, M.; Erhard, R.; Kaußler, T. Robotic Process Automation (RPA) in the Financial Sector: Technology—Implementation—Success for Decision Makers and Users; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, R.; Suriadi, S.; Adams, M.; Bandara, W.; Leemans, S.J.; Ouyang, C.; ter Hofstede, A.H.; van de Weerd, I.; Wynn, M.T.; Reijers, H.A. Robotic Process Automation: Contemporary themes and challenges. Comput. Ind. 2020, 115, 103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Montero, J.A.; Jiménez-Ramírez; Enríquez, J.G. Towards a method for automated testing in robotic process automation projects. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM 14th International Workshop on Automation of Software Test, AST 2019, Montreal, QC, Canada, 27 May 2019; pp. 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, A.; Ziora, L. The Use of Robotic Process Automation (RPA) as an Element of Smart City Implementation: A Case Study of Electricity Billing Document Management at Bydgoszcz City Hall. Energies 2021, 14, 5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, P.; Samp, C.; Urbach, N. Robotic process automation. Electron. Mark. 2020, 30, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.; Witherick, D.; Gordeeva, M. The Robots Are Ready. Are You? Untapped Advantage in Your Digital Workforce; Deloitte Development LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 24. Available online: https://branden.biz/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/The-robots-are-ready_-Are-you_Untapped-advantage-in-your-digital-workforce.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- UiPath. Speedier Service, Contented Customers: How Automation Gave VPBank a Boost. Available online: https://www.uipath.com/resources/automation-case-studies/vpbank-boosts-productivity-with-automation (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- UiPath. State Street Revolutionizes Banking Reliability Through Test Automation|UiPath. Available online: https://www.uipath.com/resources/automation-case-studies/state-street-revolutionizes-banking-reliability-through-test-automation (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- UiPath. Arnott’s Group Has Embraced a Structured Approach to Enterprise a Automation|UiPath. Available online: https://www.uipath.com/resources/automation-case-studies/arnott-group-embraced-structured-approach-to-enterprise-automation (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- KPMG. KPMG Named a Leader in Automation Fabric Services 2024. Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/our-insights/ai-and-technology/kpmg-named-a-leader-in-automation-fabric-services-2024.html (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- De Haes, S.; Van Grembergen, W. Enterprise Governance of Information Technology; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A. 6 Types of Governance Explained: Meaning and Dimensions. Available online: https://schoolofpoliticalscience.com/definitions-and-types-of-governance/#google_vignette (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Rahim, A. Governance and Good Governance-A Conceptual Perspective. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2019, 9, 133–142. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/mth/jpag88/v9y2019i3p133-142.html (accessed on 20 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. Principles of Corporate Governance, September 2016. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2016/09/08/principles-of-corporate-governance/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Bigelow, S.J.; Lutkevich, B.; Lewis, S. What Is Corporate Governance?|Definition from TechTarget. Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/searchsecurity/definition/corporate-governance (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Diligent. Corporate Governance. Available online: https://www.diligent.com/resources/guides/corporate-governance (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- QUALIFIED AUDIT ACADEMY. IT Governance—Qualified Audit Academy. Available online: https://www.audit-academy.be/en/glossary/it-governance (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Danby, S. IT Governance: Definition, Frameworks, and Best Practices. Available online: https://blog.invgate.com/it-governance (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Fletcher, M. Five Domains of Information Technology Governance for Consideration by Boards of Directors. 2008. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1794/7820 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Goddard, W. What Is IT Governance?—Brought to You by ITChronicles. Available online: https://itchronicles.com/governance/what-is-it-governance/ (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Van Grembergen, W.; De Haes, S.; Guldentops, E. Structures, Processes and Relational Mechanisms for IT Governance. In Strategies for Information Technology Governance; Van Grembergen, W., Ed.; Idea Group Publishing (IGI Global): Hershey, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 1–36. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/structures-processes-relational-mechanisms-governance/29897 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Aughton, J.; Ozer, S. Refocus Your Robotic Process Automation Lens: Internal Control Over Financial Reporting. Available online: https://d2l6535doef9z7.cloudfront.net/Uploads/b/y/f/octroboticprocessautomation_365834.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Willcocks, L.P.; Lacity, M.; Craig, A.; Willcocks, L.P.; Lacity, M.; Craig, A. The IT Function and Robotic Process Automation. 2015. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ehl:lserod:64519 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Kämäräinen, T. Managing Robotic Process Automation: Opportunities and Challenges Associated with a Federated Governance Model. 2018. Available online: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/32257 (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Asatiani, A.; Kamarainen, T. Unexpected Problems Associated with the Federated IT Governance Structure in Robotic Process Automation (RPA) Deployment—Göteborgs Universitets. 2019. Available online: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/server/api/core/bitstreams/a1e74a18-9d16-41d3-9adc-211c3d8b7dde/content (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Willcocks, L.; Hindle, J.; Lacity, M. Keys to RPA Success KEYS TO RPA SUCCESS Part 4: Change Management & Capability Development-People, Process, & Technology: How Blue Prism Clients Gain Superior Long-Term Business Value. Knowledge Capital Partners, Executive Research Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.blueprism.com/uploads/resources/white-papers/KCP_Report_Change_Management_Final.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Wei, X.; Zhang, W.; Wei, X.; Tsaur, T.S. The global research status and development trend of artificial intelligence in the field of accounting—Visual analysis based on bibliometrics. In Proceedings of the 4th Asia-Pacific Artificial Intelligence and Big Data Forum, AIBDF 2024, Ganzhou, China, 27–29 December 2024; pp. 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flechsig, C.; Anslinger, F.; Lasch, R. Robotic Process Automation in purchasing and supply management: A multiple case study on potentials, barriers, and implementation. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2022, 28, 100718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serve, O. Robotic Process Automation for Federal Government Programs. Available online: https://business.optum.com/en/insights/robotic-process-automation-federal-government-programs.html (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Carreño, A.M. An Analytical Review of John Kotter’s Change Leadership Framework: A Modern Approach to Sustainable Organizational Transformation; SSRN—Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garousi, V.; Felderer, M.; Mäntylä, M.V. The need for multivocal literature reviews in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Limerick, Ireland, 1–3 June 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garousi, V.; Felderer, M.; Mäntylä, M.V. Guidelines for including grey literature and conducting multivocal literature reviews in software engineering. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2019, 106, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “PRISMA Statement”. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Stansfield, C.; Dickson, K.; Bangpan, M. Exploring issues in the conduct of website searching and other online sources for systematic reviews: How can we be systematic? Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, J.; Pereira, R.; Moro, S. Intelligent Process Automation and Business Continuity: Areas for Future Research. Information 2023, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.; Wright, J.M.; Nixon, J.; Schoonhoven, L.; Twiddy, M.; Greenhalgh, J. Searching for Programme theories for a realist evaluation: A case study comparing an academic database search and a simple Google search. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emily Jones, M.A. LibGuides: Systematic Reviews: Step 8: Write the Review. Available online: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/systematic-reviews/write (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, London, UK, 13–14 May 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleberry, A.; Nolen, A. Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donalek, J.G. The interview in qualitative research. Urol. Nurs. 2005, 25, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Myers, M.D.; Newman, M. The qualitative interview in IS research: Examining the craft. Inf. Organ. 2007, 17, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.D. Qualitative Research in Business and Management, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, Ca, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Questionnaire: Balancing Business, IT, and Human Capital: RPA Integration and Governance Dynamics. Available online: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSd38RoeMZNXgtu6PjzoqORZa8NxTbX6N2t-rb8AfcaJFKbiFQ/viewform (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Regulation—2016/679—EN—Gdpr—EUR-Lex”. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj/eng (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- “Lei n.o 58/2019, de 8 de Agosto | DR”. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/58-2019-123815982 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Neto, G.T.G.; Santos, W.B.; Endo, P.T.; Fagundes, R.A.A. Multivocal Literature Reviews in Software Engineering: Preliminary Findings from a Tertiary Study. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement (ESEM ’19), IEEE, Porto de Galinhas, Brazil, 19–20 September 2019; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8870142 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Kokina, J.; Blanchette, S. Early evidence of digital labor in accounting: Innovation with Robotic Process Automation. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2019, 35, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmundsen, K.; Iden, J.; Bygstad, B. Organizing Robotic Process Automation: Balancing Loose and Tight Coupling. In Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 8–11 January 2019; Volume 2019, pp. 6918–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Green, P.; Robb, A. Information technology investment governance: What is it and does it matter? Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2015, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R. Crafting Information Technology Governance. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2004, 21, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrella, A.; Matulevičius, R.; Gabryelczyk, R.; Axmann, B.; Vukšić, V.B.; Gaaloul, W.; Štemberger, M.I.; Kő, A.; Lu, Q. Business Process Management: Blockchain, Robotic Process Automation, and Central and Eastern Europe Forum; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MuleSoft. Importance of RPA Governance. Available online: https://www.mulesoft.com/automation/rpa-governance (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Understanding RPA Governance Model with Best Practices via CoE. Available online: https://www.xenonstack.com/insights/rpa-governance (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Hartikainen, E.; Hotti, V.; Tukiainen, M. Improving Software Robot Maintenance in Large-Scale Environments-is Center of Excellence a Solution? IEEE Access 2022, 10, 96760–96773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascais Brás, J.; Pereira, R.F.; Moro, S.; Bianchi, I.S.; Ribeiro, R. Understanding How Intelligent Process Automation Impacts Business Continuity: Mapping IEEE/2755:2020 and ISO/22301:2019. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 134239–134258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.A.; Noveck, B.S. Introduction to the Special Issue on ChatGPT and other Generative AI Commentaries: AI Augmentation in Government 4.0. Digit. Gov. Res. Pract. 2025, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, I.; Toll, D.; Johansson, B.; Booth, M.; Rizk, A.; Melin, U. Organizational conditions required to implement RPA in local government Insights from a Swedish case study. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Taipei, Taiwan, 11–14 June 2024; pp. 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Zheng, Z. Design and implementation of intelligent search assistant based on AIGC and RPA. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering, EITCE 2024, Haikou, China, 18–20 October 2024; pp. 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.; Akola, O.; Amer, M.; Mousa, E.K.A. Artificial intelligence in financial statement preparation: Enhancing accuracy, compliance, and corporate performance. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 2025, 8, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, J.M. IT Auditing: The Practitioner’s Guide to Reliable Information Automation. In IT Auditing: The Practitioner’s Guide to Reliable Information Automation; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2025; pp. 1–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, P.; Pon Bharathi, A.; Rathika, S.; Ramamurthy, V. Application of Hyperautomation in COVID-19 Analysis and Management. In Hyperautomation for Next-Generation Industries; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanuarisa, Y.; Irianto, G.; Djamhuri, A.; Rusydi, M.K. Exploring the internal audit of public procurement governance: A systematic literature review. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Qu, W. A Robotic Process Automation-Based System for Intelligent Work Order Management with Active Service in Power System. In Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering (ICAACE), Shanghai, China, 21–23 March 2025; pp. 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokina, J.; Blanchette, S.; Davenport, T.H.; Pachamanova, D. Challenges and opportunities for artificial intelligence in auditing: Evidence from the field. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2025, 56, 100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewpersadh, N.S. Adaptive structural audit processes as shaped by emerging technologies. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2025, 56, 100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J.; Thomsen, M.; Åkesson, M. Public value creation and robotic process automation: Normative, descriptive and prescriptive issues in municipal administration. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2023, 17, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Wade, M. Robotics in securities operations. J. Secur. Oper. Custody 2018, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, K.C.; Rozario, A.M.; Vasarhelyi, M.A. Robotic Process Automation for Auditing. J. Emerg. Technol. Account. 2018, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikas Kumar. Integration of Robotic Process Automation (RPA)|UnivDatos. Available online: https://univdatos.com/blogs/integration-of-robotic-process-automation-rpa (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Chen, X.; Liang, J. Construction and Implementation Strategies of Personalized Learning Paths Based on Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Education, ICAIE 2024, Xiamen, China, 22–24 November 2024; pp. 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedziora, D.; Siemon, D.; Elshan, E.; Sońta, M. Towards stability, predictability, and quality of intelligent automation services: ECIT product journey from on-premise to as-a-service. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM International Workshop on Software-Intensive Business, IWSiB 2024, Lisbon, Portugal, 16 April 2024; pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhou, A.; Sun, Z. Research on the Automatic capture Process of Import and Export Information of RPA in Hainan Free Trade Port. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering, EITCE 2024, Haikou, China, 18–20 October 2024; pp. 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riantono, I.E.; Anggrico, K.; Calvin, C. Robotic Process Automation to Help Auditors to Improved the Audit Quality: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Industrial and Business Engineering, ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Beijing, China, 22–24 September 2023; pp. 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindawati, A.S.L.; Handoko, B.L.; Widayanto, R.K.; Irianto, D.R. Model of Innovation Diffusion for Fraud Detection Using Robotic Process Automation. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Industrial and Business Engineering, ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Beijing, China, 22–24 September 2023; pp. 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstatter, C.; Tschandl, M.; Mitterback, C. A Generic Process Model for the Introduction of Robotic Process Automation in Financial Accounting. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Computer Technology Applications, Vienna, Austria, 10–12 May 2023; pp. 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.H.; Joe, I. AI-Based RPA’s Work Automation Operation to Respond to Hacking Threats Using Collected Threat Logs. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatiani, A.; Hakkarainen, T.; Paaso, K.; Penttinen, E. Security by envelopment–a novel approach to data-security-oriented configuration of lightweight-automation systems. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2024, 33, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; David, A.; Li, W.; Fookes, C.; Bibri, S.E.; Ye, X. Unlocking Artificial Intelligence Adoption in Local Governments: Best Practice Lessons from Real-World Implementations. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1576–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Adi) Stoykova, R.A. A Governance Model for Digital Evidence in Criminal Proceedings. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2024, 55, 106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISACA. ISACA Now Blog 2023 Understanding the Risk of Robotic Process Automation. Available online: https://www.isaca.org/resources/news-and-trends/isaca-now-blog/2023/understanding-the-risk-of-robotic-process-automation?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=21147302543&gbraid=0AAAAAD_A9K_clAQ3sWE_nXKLNlcsizsnL&gclid=Cj0KCQjwkILEBhDeARIsAL--pjwF8rLpqq2AnIO90ChWA3NxPTzSimYotJSep09QHXCbMwLRcGjhbgkaAl-AEALw_wcB (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Solanki, U.; Mehta, K.; Shukla, V.K. Robotic Process Automation and Audit Quality: A Comprehensive Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 11th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions), ICRITO 2024, Noida, India, 14–15 March 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. Robotic Process Automation for Internal Audit: PwC. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/us/en/services/consulting/cybersecurity-risk-regulatory/library/robotic-process-automation-internal-audit.html (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Chugh, R.; Macht, S.; Hossain, R. Robotic Process Automation: A review of organizational grey literature. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2022, 10, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Vasarhelyi, M.A. Applying robotic process automation (RPA) in auditing: A framework. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2019, 35, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, D.; Huang, B. Leveraging NLP in Finance: A Synergistic Approach Using Large Language Models and Chain-of-Thought Reasoning. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Engineering, ICAICE 2024, Wuhu, China, 8–10 November 2024; Volume 7, pp. 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wornow, M.; Narayan, A.; Opsahl-Ong, K.; McIntyre, Q.; Shah, N.; Ré, C. Automating the Enterprise with Foundation Models. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2024, 17, 2805–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X. Application of RPA in Power Grid Industry. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Computer Science and Management Technology, ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Xi’an, China, 13–15 October 2023; pp. 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, S.; Prasanth, A.; Satheesh Kumar, K.; Kadry, S. Artificial Intelligence-Based Hyperautomation for Smart Factory Process Automation. In Hyperautomation for Next-Generation Industries; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 55–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, S.; Ma, X.; Tian, Z.; He, X.; Wang, Y. AI-Based Intelligent Decision-Making Platform for Operational Excellence in the Oil and Gas Industry. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 6th International Seminar on Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Information Technology (AINIT), Shenzhen, China, 11–13 April 2025; pp. 1639–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, H.L.M.; Ferreira, M.A. Automation and public oversight in Brazil: Evaluating the monitoring of fiscal management reports. Adm. Manag. Public 2025, 2025, 114–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, C.; Zhang, W. Research on Electricity Marketing Inspection Methods Applying RPA Informationization Intelligent Management Technology. J. Comb. Math. Comb. Comput. 2025, 127a, 1715–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufi, F.; Alsulami, M. AI-Driven Chatbot for Real-Time News Automation. Mathematics 2025, 13, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M. Does automation improve financial reporting? Evidence from internal controls. Rev. Account. Stud. 2025, 30, 436–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.K.; Hsieh, S.F. Evaluating the Impact of Robotic Process Automation on Earnings Management. J. Inf. Syst. 2025, 39, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamithireddy, N.S. Cash Flow Forecasting in SAP ERP Enhanced by UiPath Automation: A Predictive Analytics Approach. Indian J. Inf. Sources Serv. 2025, 15, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamithireddy, N.H. Automating Foreign Exchange Operations in SAP ERP Using UiPath: A Framework for Improved Efficiency. Indian J. Inf. Sources Serv. 2025, 15, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, L.; Varela, L.; Silveira, Z.; Felgueiras, C.; Pereira, F. A Framework for Integrating Robotic Process Automation with Artificial Intelligence Applied to Industry 5.0. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celonis. Successful RPA Implementation: A Roadmap for Robotic Process Automation. Available online: https://www.celonis.com/blog/successful-rpa-implementation-a-roadmap-for-robotic-process-automation/?creative=763071753522&keyword=&matchtype=&network=g&device=c&utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc_dsa&utm_campaign=evergreen&utm_term=&utm_content=22477180280_en_land_rparoadmap_1maxconv&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22477180280&gbraid=0AAAAADLGpd3G5xFdBA0w81cwOmViHaK4s&gclid=Cj0KCQjwkILEBhDeARIsAL--pjzvxk7OMGSvcIwCVTMSEvAuhXWeDV7ucDpfK7xIbMd1lbEocnwNvkIaAlQgEALw_wcB (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- IBM. What Is Robotic Process Automation (RPA)?|IBM. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/rpa (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Dahiyat, A. Robotic process automation and audit quality. Corp. Gov. Organ. Behav. Rev. 2022, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candide. RPA in Audit: 7 Key Insights for Robust Solutions. Available online: https://www.datasnipper.com/resources/rpa-in-audit-7-insights-building-rpa-solutions (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Rameez Ali. Incorporating Robotic Process Automation (RPA) Capability in Internal Audit|LinkedIn. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/incorporating-robotic-process-automation-rpa-capability-rameez-ali/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- CrossCountry Consulting. Generating Internal Audit Workpapers with Robotic Process Automation—CrossCountry Consulting. Available online: https://www.crosscountry-consulting.com/insights/blog/generating-internal-audit-workpapers-with-rpa/ (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Shaaheen Tar-Mahomed. Robotic Process Automation (RPA) Powering Up the Audit—KPMG South Africa. November 2021. Available online: https://kpmg.com/za/en/home/insights/2021/11/robotic-process-automation--rpa--powering-up-the-audit.html (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Tommervag, A.S.; Bach, T.; Jager, B. Leveraging the competition: Robotic Process Automation (RPA) enabling competitive Small and Medium sized Auditing Firms. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration, SII 2022, Virtual, 9–12 January 2022; pp. 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wan, Y. New Quality Productivity of Enterprises and Artificial Intelligence: Based on A-share High-tech Enterprises. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Big Data Economy and Information Management, BDEIM 2024, Zhengzhou, China, 13–15 December 2024; pp. 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotis, K.; Angoura, E.; Lyngri, E.I. Emerging technologies in smart libraries for visually impaired people: Challenges and design considerations. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2025, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, H.; Tursoy, T. The Effect of Corporate Governance on Financial Performance: Evidence from a Shareholder-Oriented System. Interdiscip. J. Manag. Stud. 2023, 16, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurrahman, A.P.; Yousif, K.A.; Sani, A.A.; Al-Absy, M.S.M.; Abubakar, A.H. Extending UTAUT Through Moderating Effects of Digitalization on the Audit Profession. Stud. Syst. Decis. Control. 2025, 568, 1165–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jnainati, M.; Al Jnainati, J.; Rath, S.; Aujla, S.; Nasir, E.; Govindarajan, A.; Samantaray, Y.; Semy, M. Transforming paperwork with AI: Applications across healthcare and other industries. AI Soc. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Aggarwal, R.; Garg, P.; Aggarwal, D. AI and ESG Performance: An Empirical Study of the High-Tech Sector. Prabandhan Indian J. Manag. 2025, 18, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]