Identifying Individual Information Processing Styles During Advertisement Viewing Through EEG-Driven Classifiers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The main contributions of this research can be summarized as follows:

- The provision of empirical evidence that the analysis of a subject’s EEG signals during advertisement exposure can predict their classification as either a verbalizer or a visualizer. As a result, our model can assist marketers in tailoring the content of advertisement campaigns according to the consumer’s processing style, aiming to enhance emotional engagement and improve conversion outcomes.

- A comparative evaluation of widely used machine learning classifiers—Support Vector Machine (SVM), Decision Tree, and k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN)—for the task of predicting cognitive processing style from EEG frequency-domain features recorded during exposure to different types of advertisements. Also, we test which frequency bands act as neural markers of cognitive processing style across different advertising types, with a priori emphasis on theta based on the prior literature.

2. Related Work

2.1. Individual Differences Affecting Consumer Behaviour

Information Processing Style and Consumer Response

2.2. EEG in Neuromarketing

2.2.1. General Overview

2.2.2. EEG-Based Consumer Research

EEG and Cognitive Processing Style

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Stimulus Material

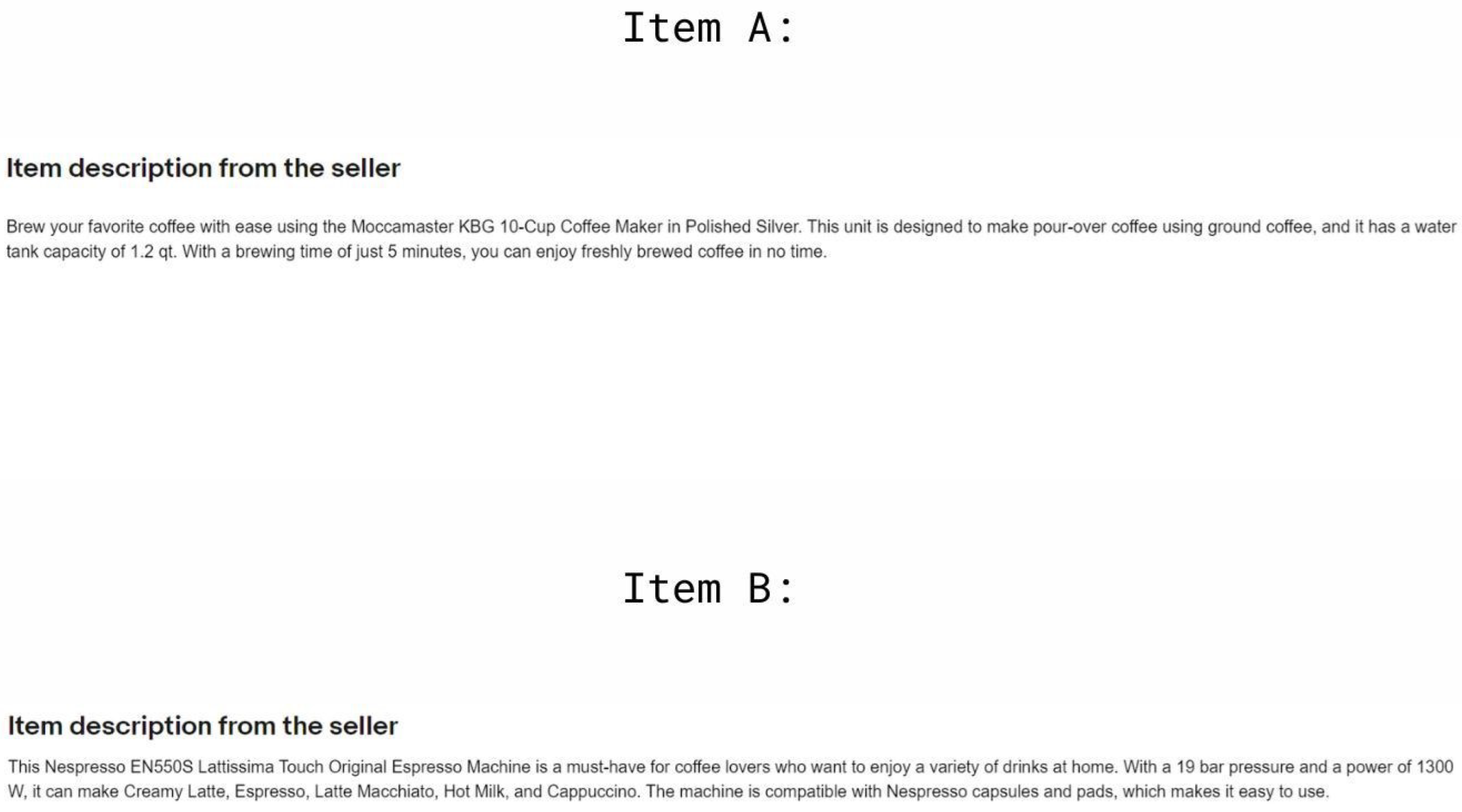

- The verbal version consisted of marketing-oriented text only (e.g., features, benefits, usage scenarios), presented without accompanying images. An example of a verbal stimulus is shown in Figure 2.

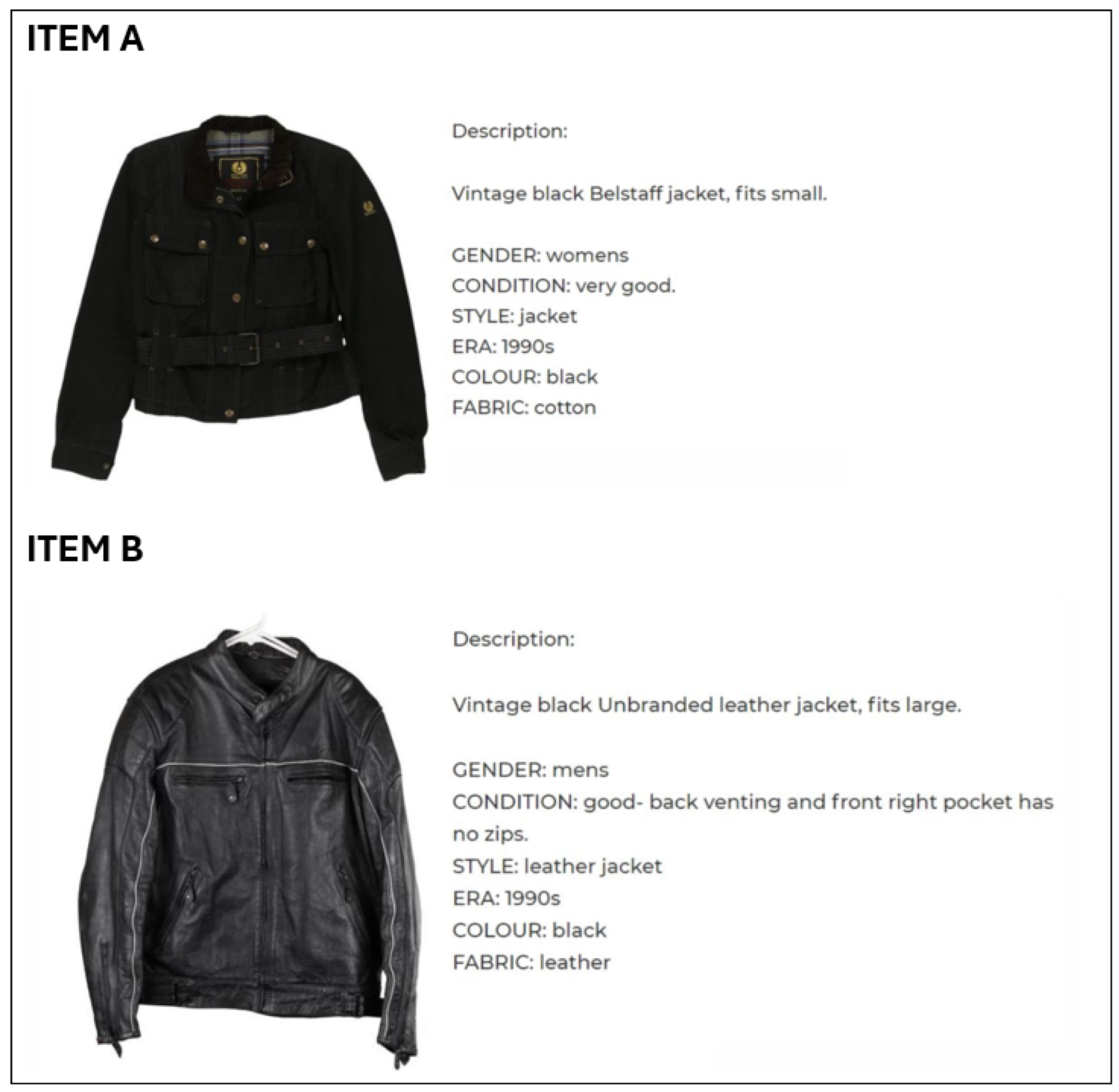

- The visual version included only visual content, such as product photos, icons, and layout designs, without textual information. A sample visual stimulus is presented in Figure 3.

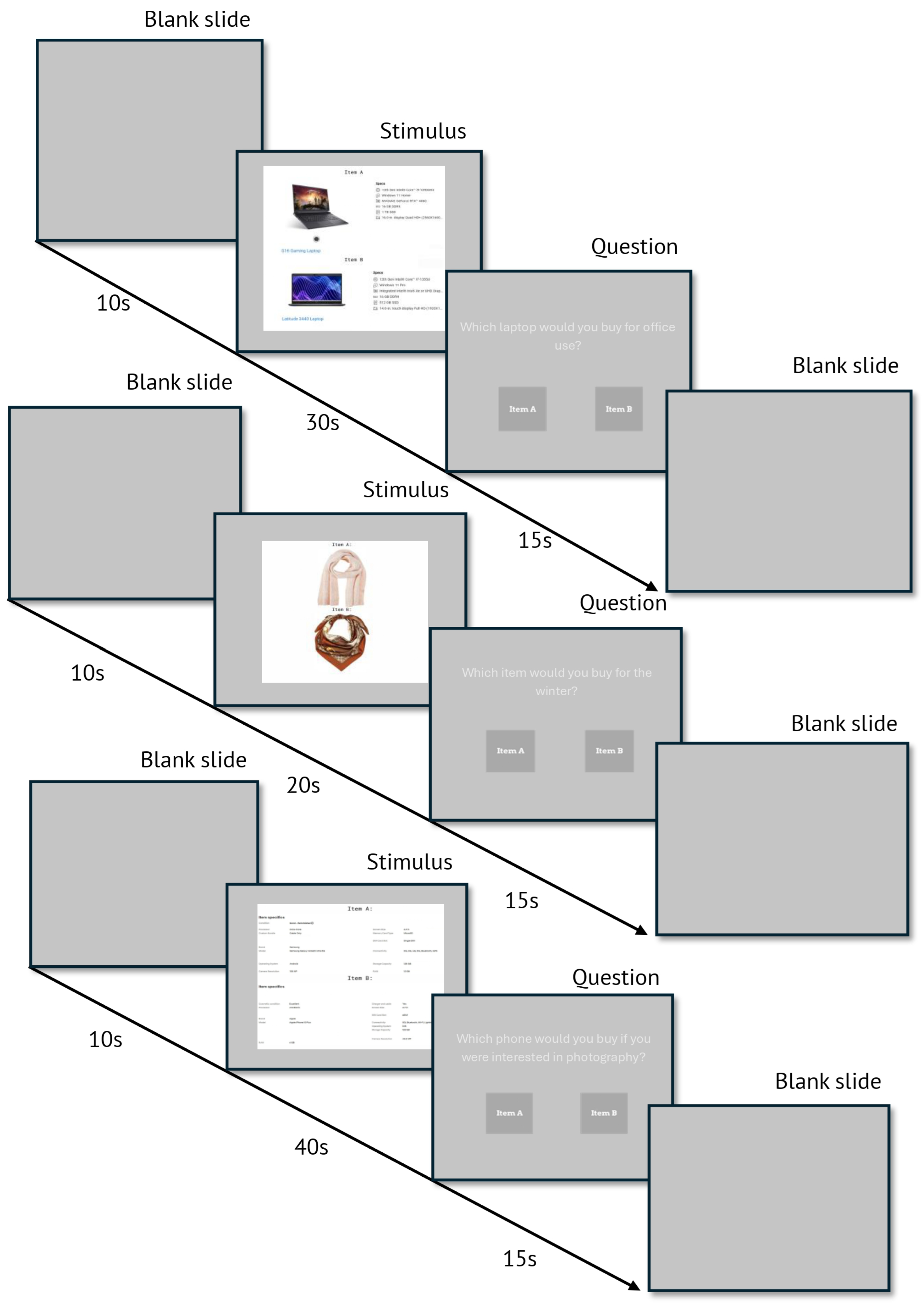

- The mixed version combined both visual and textual elements in a balanced layout. An example of this format is shown in Figure 4.

3.2. Presentation of Stimulus Material to Users

- 40 s for verbal-only ads (text descriptions);

- 30 s for mixed ads (text and image);

- 20 s for visual-only ads (images only).

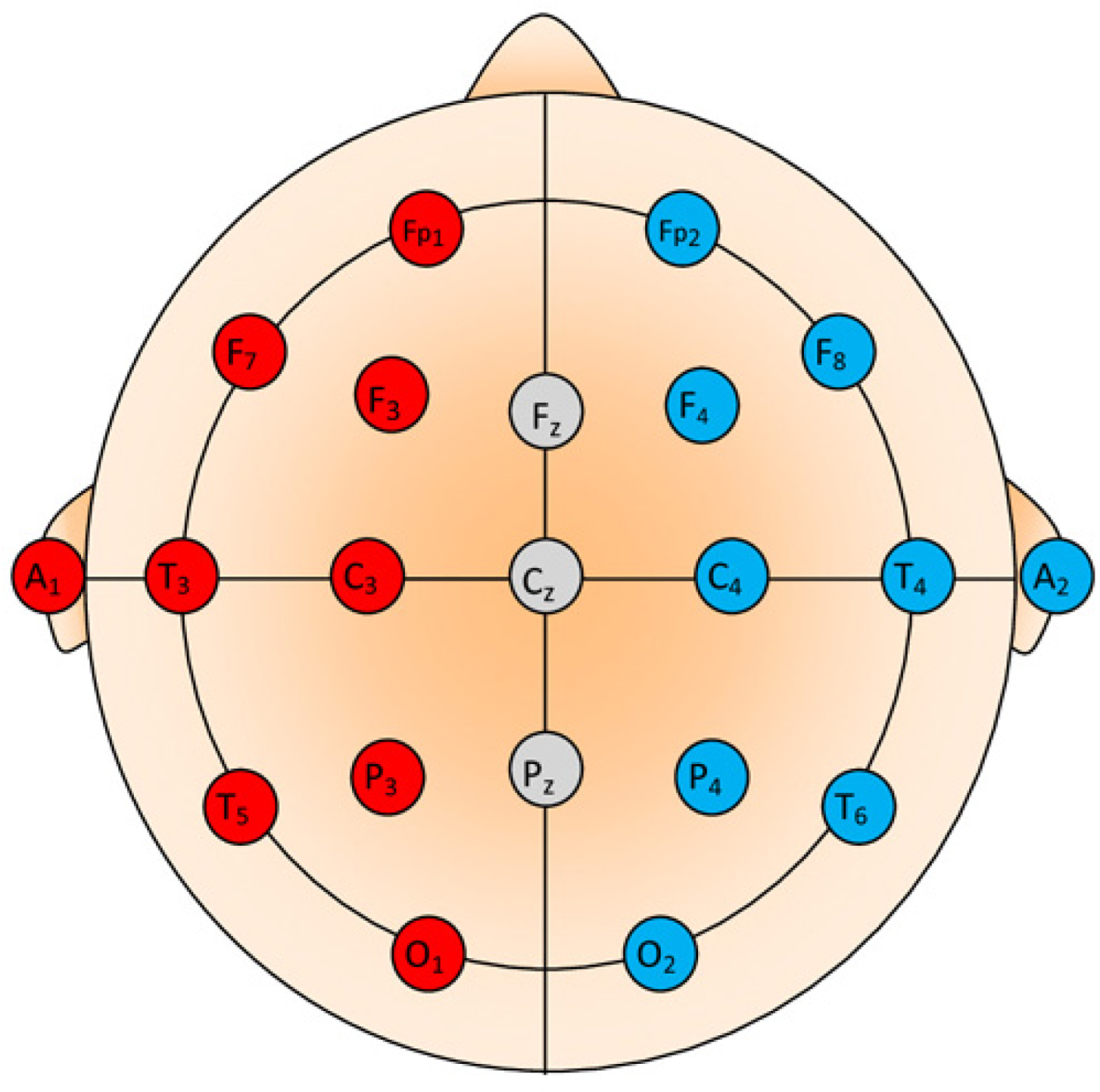

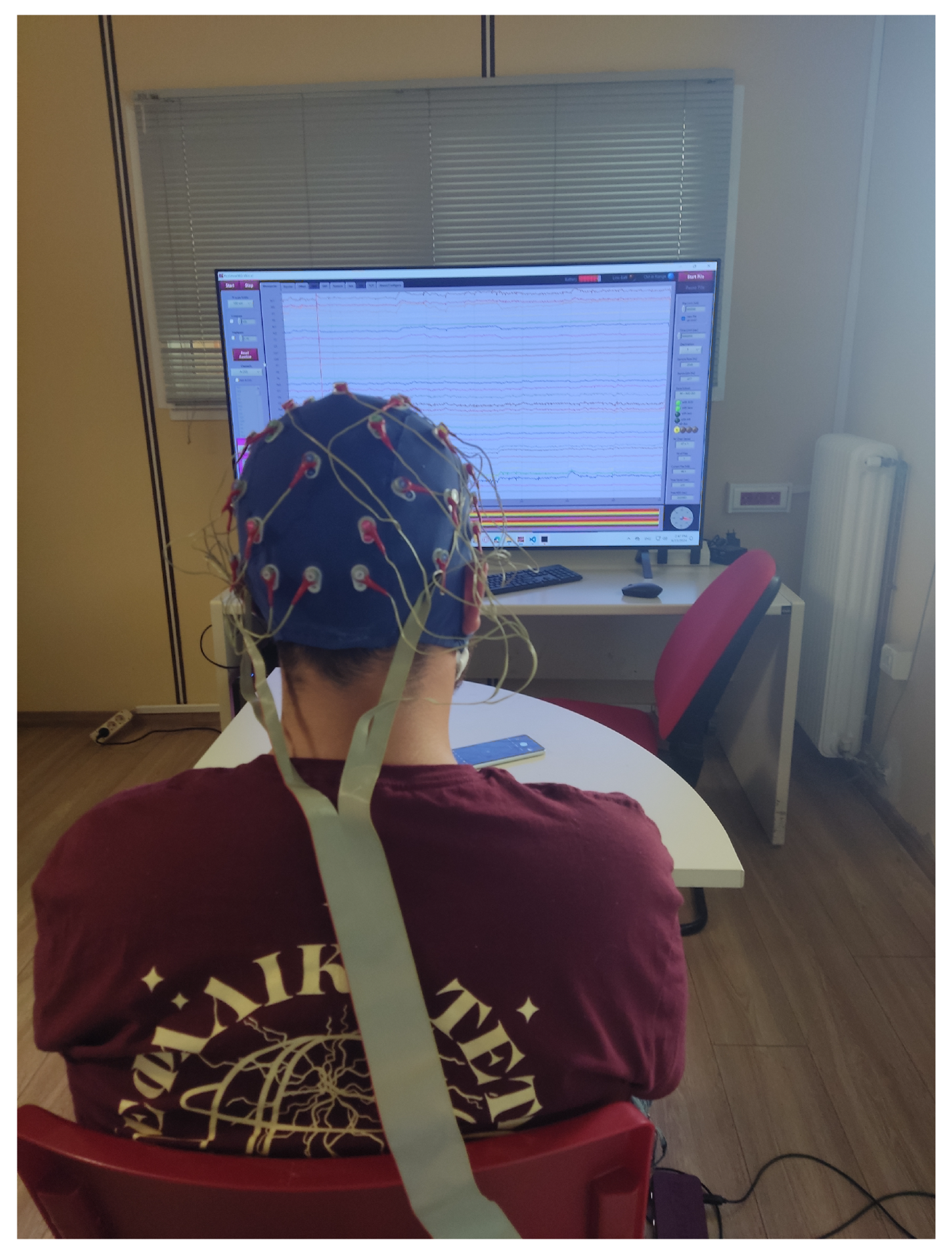

3.3. Equipment

3.4. Participants

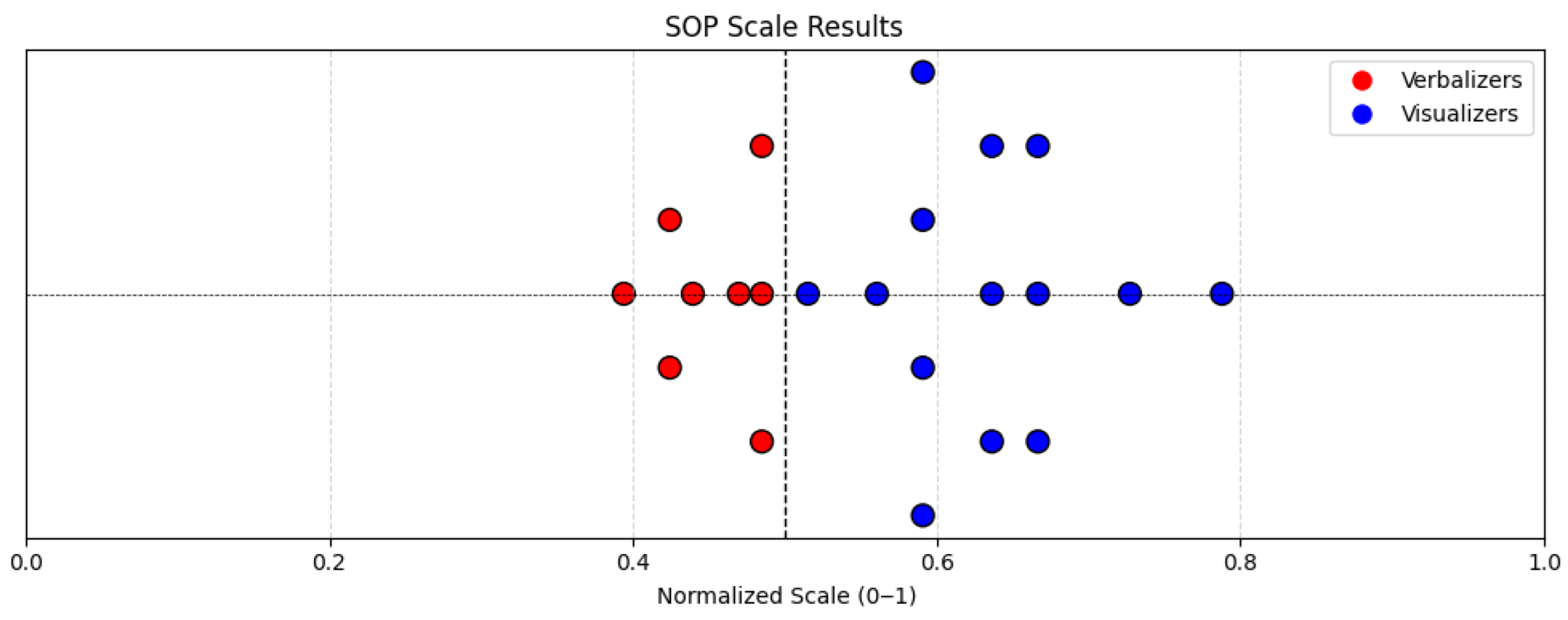

3.5. Ethical Considerations

3.6. Experimental Design and Procedure

3.7. EEG Analysis Pipeline

3.7.1. EEG Signal Pre-Processing

- Bandpass filtering (0.5–45 Hz): An FIR filter was applied to retain frequencies relevant to cognitive processing while eliminating slow drifts and high-frequency noise.

- Line noise removal: A 50 Hz notch filter was used to suppress power line interference.

- Common average referencing (CAR): EEG recordings were re-referenced using the average potential across all electrodes, to reduce spatial bias and improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Bad channel interpolation: Noisy or malfunctioning channels were detected based on deviation metrics such as low correlation with neighbouring electrodes, high-amplitude artifacts, or signal dropout [59]. Only non-frontal bad channels were interpolated to avoid distortion in neuromarketing relevant regions.

- Artifact subspace reconstruction (ASR): Transient high-amplitude artifacts were suppressed using ASR, a method that reconstructs corrupted signal components by comparing them to a clean baseline covariance [60]. ASR is particularly effective at handling high-amplitude transient artifacts, such as sudden movements or muscle contractions, which are difficult to isolate through ICA alone. In contrast, ICA excels at separating spatially stable sources such as eye blinks and sustained muscle activity, making the combination of both techniques highly complementary in cleaning EEG data collected in naturalistic tasks like advertisement viewing.

- Independent component analysis (ICA): ICA was used to decompose the EEG signal into independent components. Artifacts related to eye movements and muscle activity were identified and removed through automated and visual inspection.

3.7.2. Feature Extraction

3.7.3. Classification

4. Experimental Results

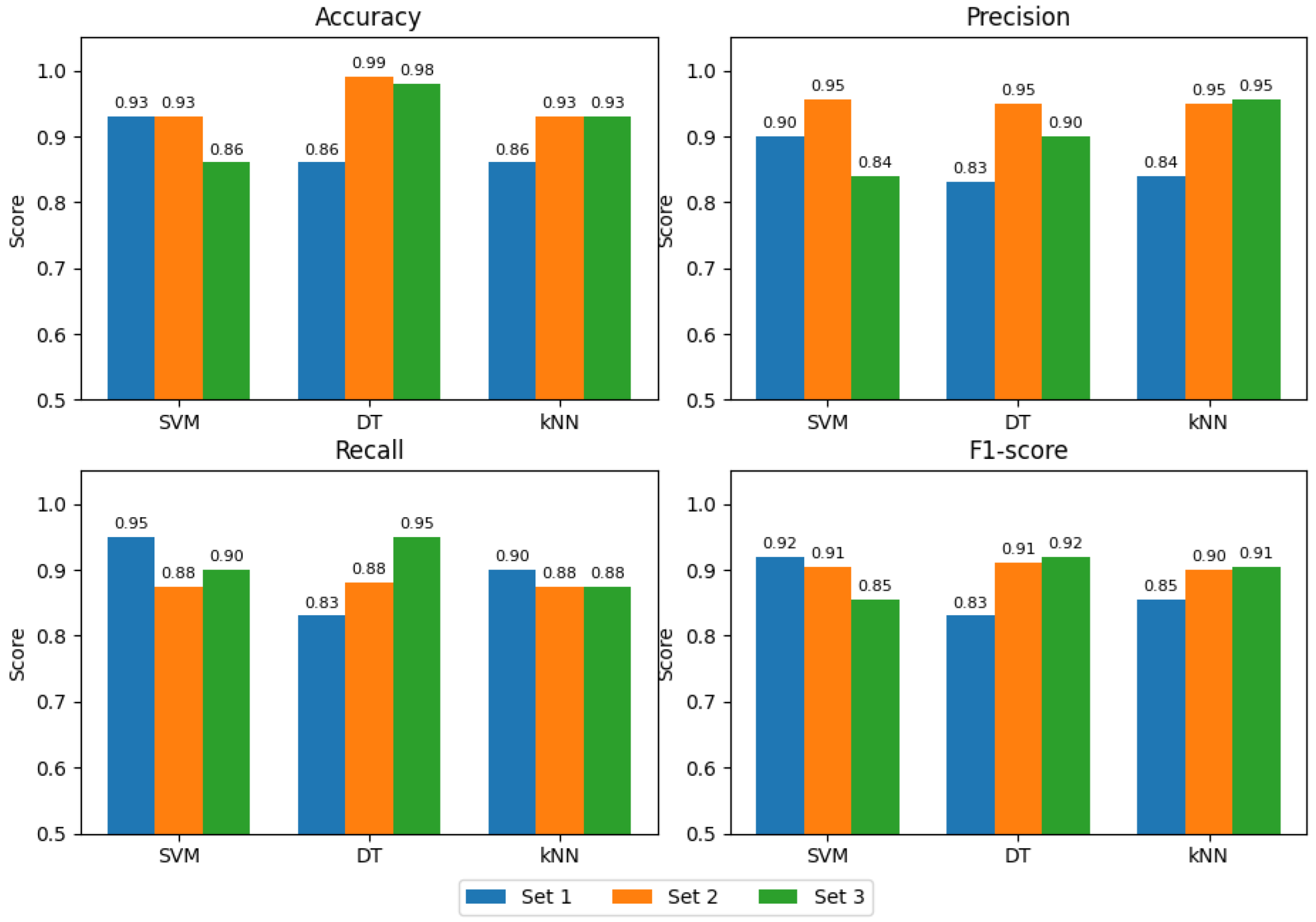

4.1. Classification Results

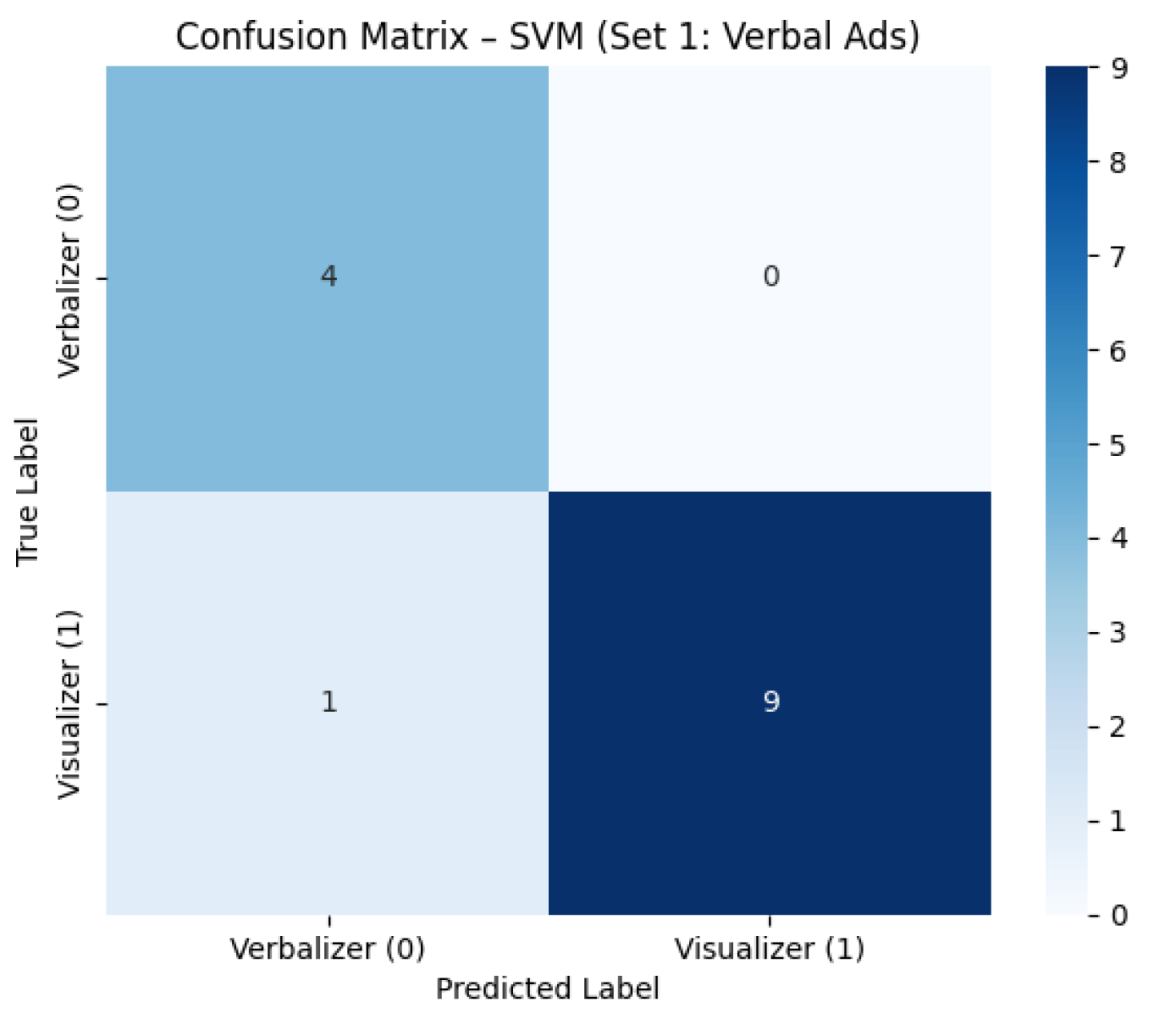

- Set 1—Verbal Advertisements

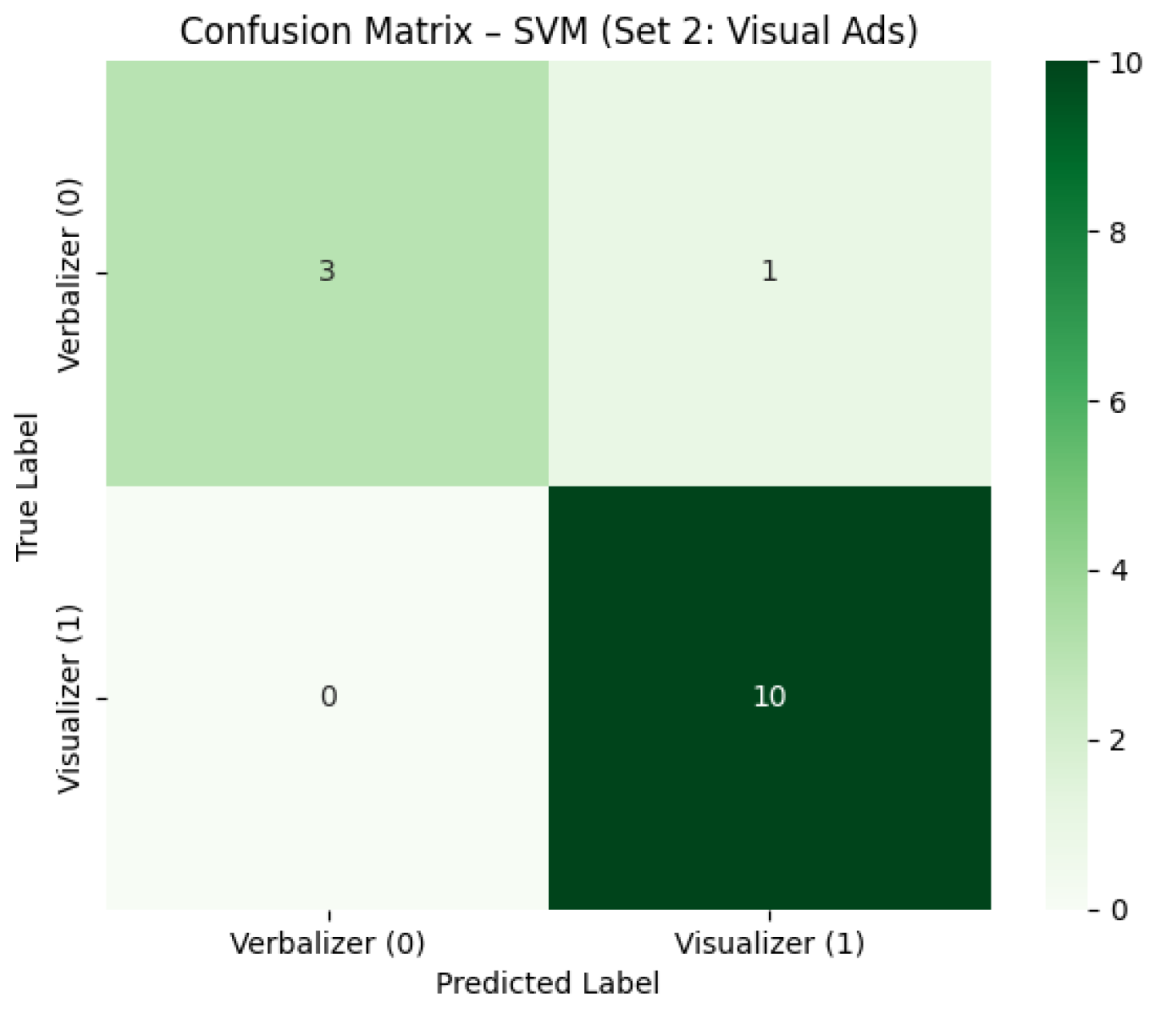

- Set 2—Visual Advertisements

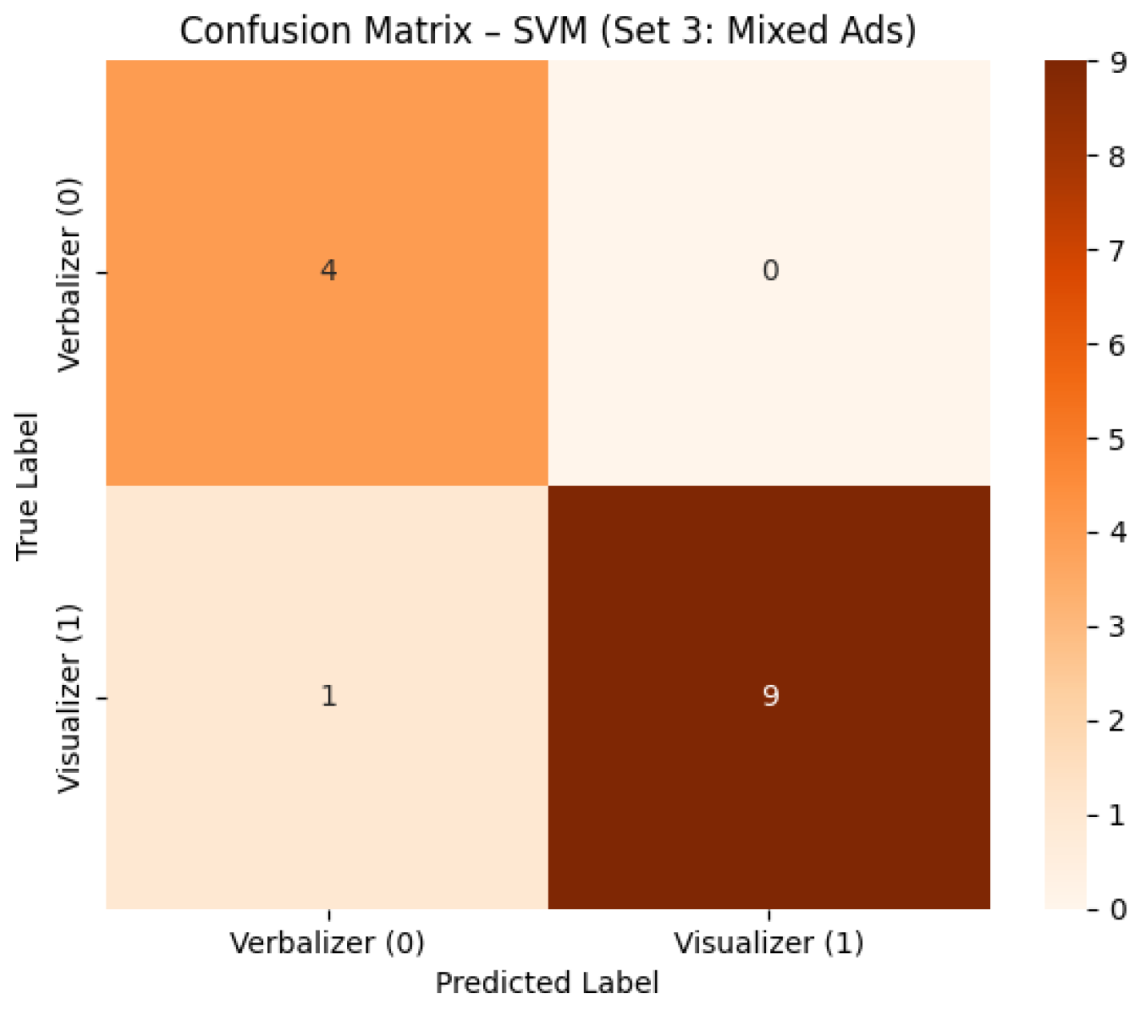

- Set 3—Mixed Advertisements

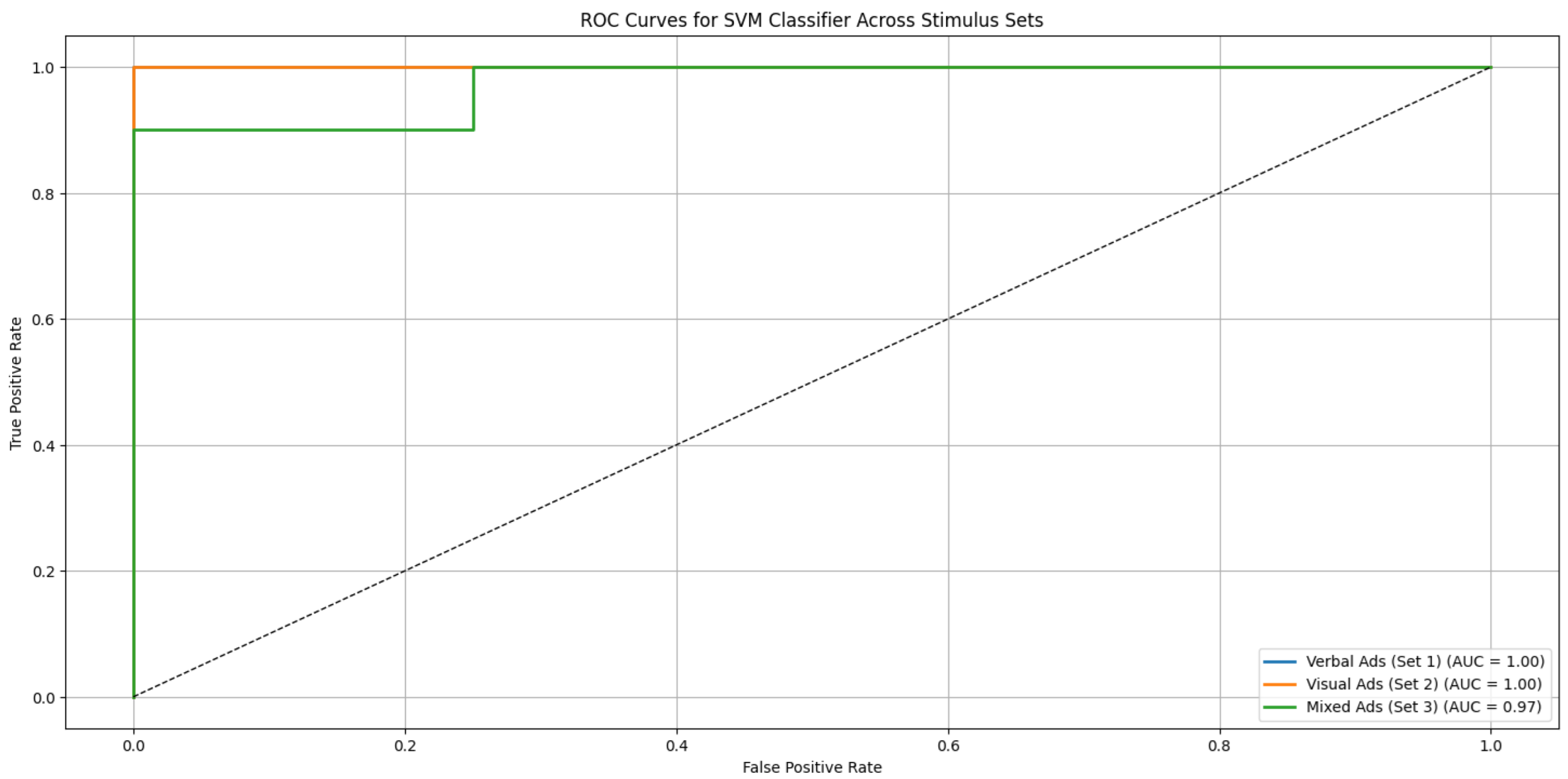

- Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curves

4.2. Statistical Analysis of EEG Frequency Bands

- Set 1—Verbal Advertisements

- Set 2—Visual Advertisements

- Set 3—Mixed Advertisements

4.3. Depth Analysis of the Viewing Phase Among Participants

- Verbal ads (Set 1). The largest effects appeared over the parietal theta and posterior sites (with negative d values indicating higher power in verbalizers). For example, P4–Theta (), P8–Theta (), Pz–Theta (), and Parietal–Theta ().

- Visual ads (Set 2). Differences peaked occipitally/parieto-occipitally, especially in theta and delta: O2–Theta (), Occipital–Theta (), and Pz–Theta ().

- Mixed ads (Set 3). A similar occipital/parietal pattern emerged, notably in delta and theta: P4–Theta (), Oz–Delta (), Occipital–Delta (), O1–Delta ().

Interpretation

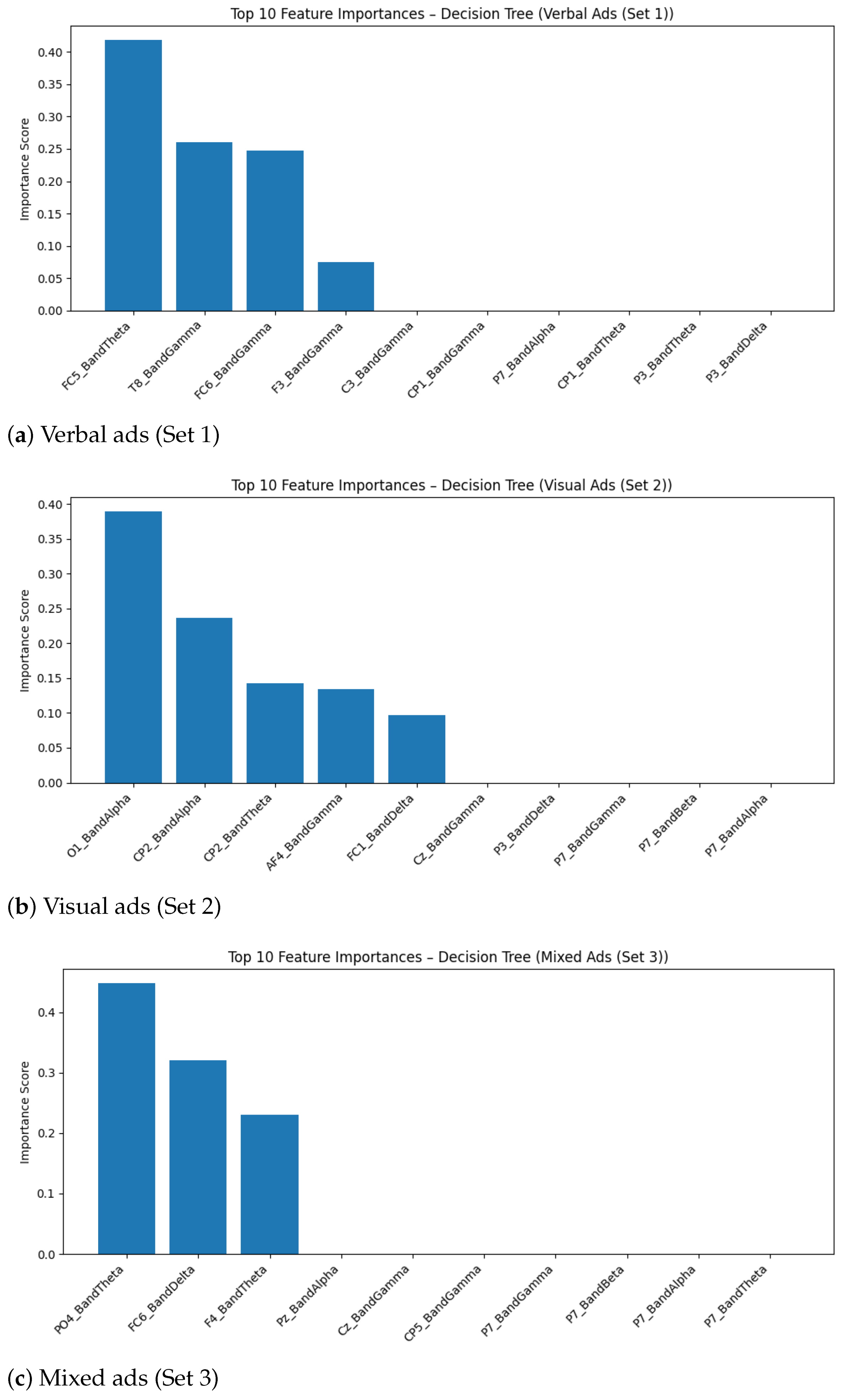

4.4. Feature Importance Analysis

4.5. Summary and Interpretation

5. Discussion

5.1. Advancing Prior Research

5.2. Main Findings

5.3. Empirical and Practical Implications

- Dynamic ad personalization: Wearable or BCI (brain–computer interface) environments can integrate EEG-driven classifiers in order to adapt advertisements’ content or type (visual vs. verbal) in real time according to consumer’s processing style preference. Such systems can lead to better fluency of advertisement messages, emotional engagement, and ultimately conversion rates.

- E-commerce and recommendation systems: Online platforms, especially in mobile-based shopping contexts, where screen space is limited, can adapt product presentations (e.g., image-dominant or text-rich formats) according to inferred user style, thereby enhancing decision satisfaction and reducing cognitive load.

- e-Learning and educational content: In digital education platforms, instructional materials can be adapted according to learners’ dominant processing modes. In this way, factors such as retention, comprehension and motivation can be improved.

- Healthcare and mental wellness applications: Personalized therapeutic content (e.g., cognitive-behavioural interventions, mental health messaging) can be adapted to patients’ cognitive preferences, possibly leading to increased adherence and emotional engagement.

- User interface (UI) and experience (UX) design: EEG-based style classifications can be used by designers to customize interface layouts, menu structures, or onboarding sequences. For example, visualizers may prefer icon-heavy dashboards, while verbalizers may prefer instructional tooltips and detailed menus.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alsharif, A.H.; Salleh, N.Z.M.; Baharun, R.; Rami Hashem, E.A. Neuromarketing research in the last five years: A bibliometric analysis. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1978620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damião de Paula, A.L.; Lourenção, M.; de Moura Engracia Giraldi, J.; Caldeira de Oliveira, J.H. Effect of emotion induction on potential consumers’ visual attention in beer advertisements: A neuroscience study. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 202–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarrone, F.; Van Hulle, M.M. Measuring brand association strength with EEG: A single-trial N400 ERP study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, M.C.; Yen, C.; Chen, H.L. Does Age Matter? Using Neuroscience Approaches to Understand Consumers’ Behavior towards Purchasing the Sustainable Product Online. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, A.; Kalaitzi, E.; Fidas, C.A. A review on the use of eeg for the investigation of the factors that affect Consumer’s behavior. Physiol. Behav. 2024, 278, 114509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.J.; Jones, W.; Childers, T.L. Neuromarketing as a scale validation tool: Understanding individual differences based on the style of processing scale in affective judgements. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, T.L.; Houston, M.J.; Heckler, S.E. Measurement of Individual Differences in Visual Versus Verbal Information Processing. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riding, R.; Burton, D.; Rees, G.; Sharratt, M. Cognitive style and personality in 12-year-old children. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1995, 65, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, R.E.; Massa, L.J. Three facets of visual and verbal learners: Cognitive ability, cognitive style, and learning preference. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBarbera, P.A.; Weingard, P.; Yorkston, E.A. Matching the message to the mind: Advertising imagery and consumer processing styles. J. Advert. Res. 1998, 38, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, S.; Sicilia, M. The impact of cognitive and/or affective processing styles on consumer response to advertising appeals. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchiato, G.; Astolfi, L.; De Vico Fallani, F.; Cincotti, F.; Mattia, D.; Salinari, S.; Soranzo, R.; Babiloni, F. Changes in brain activity during the observation of TV commercials by using EEG, GSR and HR measurements. Brain Topogr. 2010, 23, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Zahhad, M.; Ahmed, S.M.; Abbas, S.N. A new EEG acquisition protocol for biometric identification using eye blinking signals. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2015, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paivio, A. Mind and Its Evolution: A Dual Coding Theoretical Approach; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. Multimedia Learning, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pieters, R.; Wedel, M. Attention Capture and Transfer in Advertising: Brand, Pictorial, and Text-Size Effects. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A. The Effect of Verbal and Visual Components of Advertisements on Brand Attitudes and Attitude Toward the Advertisement. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Learning-Style Inventory: Self-Scoring Inventory and Interpretation Booklet; TRG Hay/McBer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Emami, A.; Taheri, Z.; Zuferi, R. The interplay between framing effects, cognitive biases, and learning styles in online purchasing decision: Lessons for Iranian enterprising communities. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2024, 18, 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadikoglu, G.; Dovlatova, K.J.; Akyurek, S. The Effect of Locus of Control and Thinking Style on Impulse Buying Behaviour from the Perspectives on Gender Differences. In Proceedings of the 12th World Conference “Intelligent System for Industrial Automation” (WCIS-2022); Aliev, R.A., Yusupbekov, N.R., Kacprzyk, J., Pedrycz, W., Babanli, M.B., Sadikoglu, F.M., Turabdjanov, S.M., Eds.; Spinger: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie, R.; Main, K. Optimizing product trials by eliciting flow states: The enabling roles of curiosity, openness and information valence. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 50–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Sudarshan, S.; Sussman, K.L.; Bright, L.F.; Eastin, M.S. Why are consumers following social media influencers on Instagram? Exploration of consumers’ motives for following influencers and the role of materialism. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defta, N.; Barbu, A.; Ion, V.A.; Pogurschi, E.N.; Osman, A.; Cune, L.C.; Bădulescu, L.A. Exploring the Relationship Between Socio-Demographic Factors and Consumers’ Perception of Food Promotions in Romania. Foods 2025, 14, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanim, J.; Alghifari, E.S.; Setia, B.I. Exploring advertising stimulus, hedonic motives, and impulse buying behavior in Indonesia’s digital context: Demographics implications. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2428779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, G.; Ha-Brookshire, J. Gender differences in information processing and transparency: Cases of apparel brands’ social responsibility claims. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandler, G. The Structure of Value: Accounting for Taste; CHIP Report; Center for Human Information Processing, Department of Psychology, University of California: San Diego, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Pruysers, S. Supermarket politics: Personality and political consumerism. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2025, 2025, 01925121241308213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, X.; Wu, Z.; Du, J.; Zhu, L. The busier, the more outcome-oriented? How perceived busyness shapes preference for advertising appeals. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handrich, M. Alexa, you freak me out-Identifying drivers of innovation resistance and adoption of Intelligent Personal Assistants. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACIS 19th International Conference on Computer and Information Science (ICIS), Shanghai, China, 23–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Correa, P.E.; Grandón, E.E.; Arenas-Gaitán, J. Assessing differences in customers’ personal disposition to e-commerce. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 792–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumanov, M.; Cooper, H.; Ewing, M. Using AI predicted personality to enhance advertising effectiveness. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 1590–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Gunn, F. The Impact of Image Dimensions toward Online Consumers’ Perceptions of Product Aesthetics. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2016, 26, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Kim, M. The effects of online product presentation on consumer responses: A mental imagery perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2464–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.C.; Biswas, A.; Babin, L.A. The operation of visual imagery as a mediator of advertising effects. J. Advert. 1993, 22, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bellis, E.; Hildebrand, C.; Ito, K.; Herrmann, A.; Schmitt, B. Personalizing the customization experience: A matching theory of mass customization interfaces and cultural information processing. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 1050–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Grace, D.; Ross, M. Self-regulatory focus and advertising effectiveness. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Kwak, D.H.; Bagozzi, R.P. Cultural cognition and endorser scandal: Impact of consumer information processing mode on moral judgment in the endorsement context. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.K.; Pandey, P.K. Examining the potential effects of augmented reality on the retail customer experience: A systematic literature analysis. Int. J. Netw. Virtual Organ. 2024, 31, 191–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Attri, R. Physimorphic vs. Typographic logos in destination marketing: Integrating destination familiarity and consumer characteristics. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, J.N.; Hani, A.J.; Cheek, J.; Thirumala, P.; Tsuchida, T.N. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society Guideline 2: Guidelines for Standard Electrode Position Nomenclature. Neurodiagnostic J. 2016, 56, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.P. Preprocessing of EEG: Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Bian, G.B.; Tian, Z. Removal of Artifacts from EEG Signals: A Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Beadle, P. Independent component analysis of EEG signals. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Workshop on VLSI Design and Video Technology, Suzhou, China, 28–30 May 2005; pp. 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Y.; Hsu, S.H.; Pion-Tonachini, L.; Jung, T.P. Evaluation of Artifact Subspace Reconstruction for Automatic EEG Artifact Removal. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 17–21 July 2018; pp. 1242–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBME. Introduction to EEG; EBME: Bedford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aldayel, M.; Ykhlef, M.; Al-Nafjan, A. Deep Learning for EEG-Based Preference Classification in Neuromarketing. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.; Seal, A. A Deep Convolution Neural Networks Framework for Analyzing Electroencephalography Signals in Neuromarketing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Frontiers in Computing and Systems, IIT Mandi, Mandi, India, 16–17 October 2023; Basu, S., Kole, D.K., Maji, A.K., Plewczynski, D., Bhattacharjee, D., Eds.; pp. 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, A.; Riding, R.J. EEG differences and cognitive style. Biol. Psychol. 1999, 51, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riding, R.; Cheema, I. Cognitive styles—An overview and integration. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A. Verbalizer-visualizer: A cognitive style dimension. J. Ment. Imag. 1977, 1, 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, T.; Sreejesh, S.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Brand logos versus brand names: A comparison of the memory effects of textual and pictorial brand elements placed in computer games. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünzli, F.; Eppler, M.J. How verbal text guides the interpretation of advertisement images: A predictive typology of verbal anchoring. Commun. Theory 2024, 34, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K.; Schotter, E.R.; Masson, M.E.J.; Potter, M.C.; Treiman, R. So Much to Read, So Little Time: How Do We Read, and Can Speed Reading Help? Psychol. Sci. Public Interest A J. Am. Psychol. Soc. 2016, 17, 4–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, M. How many words do we read per minute? A review and meta-analysis of reading rate. J. Mem. Lang. 2019, 109, 104047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, S.; Fize, D.; Marlot, C. Speed of processing in the human visual system. Nature 1996, 381, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, M.C.; Wyble, B.; Hagmann, C.E.; McCourt, E.S. Detecting meaning in RSVP at 13 ms per picture. Atten. Percept. Psychophys 2014, 76, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweller, J.; Ayres, P.; Kalyuga, S. Altering Element Interactivity and Intrinsic Cognitive load. In Cognitive Load Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khondakar, M.F.K.; Trovee, T.G.; Hasan, M.; Sarowar, M.H.; Chowdhury, M.H.; Hossain, Q.D. A Comparative Analysis of Different Pre-Processing Pipelines for EEG-Based Preference Prediction in Neuromarketing. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Pune Section International Conference (PuneCon), Pune, India, 14–16 December 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigdely-Shamlo, N.; Mullen, T.; Kothe, C.; Su, K.M.; Robbins, K.A. The PREP pipeline: Standardized preprocessing for large-scale EEG analysis. Front. Neuroinform. 2015, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, S.; Jacobsen, N.S.; Bleichner, M.G.; Debener, S. A Riemannian modification of artifact subspace reconstruction for EEG artifact handling. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BioSemi. ActiveTwo System: Technical Manual. 2025. Available online: https://www.biosemi.com (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Welch, P. The use of fast Fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. 1967, 15, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, R. Machine learning techniques for electroencephalogram based brain-computer interface: A systematic literature review. Meas. Sens. 2023, 28, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khondakar, M.F.K.; Sarowar, M.H.; Chowdhury, M.H.; Majumder, S.; Hossain, M.A.; Dewan, M.A.A.; Hossain, Q.D. A systematic review on EEG-based neuromarketing: Recent trends and analyzing techniques. Brain Inform. 2024, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, J. SMOTE for Imbalanced Classification with Python. Anal. Vidhya 2025, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Klem, G.H.; Lüders, H.O.; Jasper, H.H.; Elger, C. The ten-twenty electrode system of the International Federation. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Suppl. 1999, 52, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jurcak, V.; Tsuzuki, D.; Dan, I. 10/20, 10/10, and 10/5 systems revisited: Their validity as relative head-surface-based positioning systems. NeuroImage 2007, 34, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, J.F.; Frank, M.J. Frontal theta as a mechanism for cognitive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmony, T. The functional significance of delta oscillations in cognitive processing. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikhi, S.; Matton, N.; Blanchet, S. EEG power spectral measures of cognitive workload: A meta-analysis. Psychophysiology 2022, 59, e14009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarnecchi, E.; Sprugnoli, G.; Bricolo, E.; Costantini, G.; Liew, S.L.; Musaeus, C.S.; Salvi, C.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Rossi, A.; Rossi, S. Gamma tACS over the temporal lobe increases the occurrence of Eureka! moments. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.; Khuc, J.; Saccani, M.S.; Zokaei, N.; Cappelletti, M. Gamma oscillations modulate working memory recall precision. Exp. Brain Res. 2021, 239, 2711–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacigalupo, F.; Luck, S.J. Alpha-band EEG suppression as a neural marker of sustained attentional engagement to conditioned threat stimuli. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2022, 17, 1101–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Sun, J.; Bengson, J.J.; Mangun, G.R.; Tong, S. Normal aging selectively diminishes alpha lateralization in visual spatial attention. NeuroImage 2015, 106, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamia, A.; Terral, L.; D’ambra, M.R.; VanRullen, R. Distinct roles of forward and backward alpha-band waves in spatial visual attention. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Reinhart, R.M.G.; Choi, I.; Shinn-Cunningham, B. Causal links between parietal alpha activity and spatial auditory attention. bioRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, N.; Ray, W.; Slobounov, S. Encoding of visual-spatial information in working memory requires more cerebral efforts than retrieval: Evidence from an EEG and virtual reality study. Brain Res. 2010, 1347, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberry, C.; Commins, S. Frontal delta and theta power reflect strategy changes during human spatial memory retrieval in a virtual water maze task: An exploratory analysis. Front. Cogn. 2024, 3, 1393202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: A review and analysis. Brain Res. Rev. 1999, 29, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.S., II; Bruner, G.C.; Kumar, A. Webpage Background and Viewer Attitudes. J. Advert. Res. 2000, 40, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.S.; Stammerjohan, C.A.; Coulter, R.A. Banner advertiser-web site context congruity and color effects on attention and attitudes. J. Advert. 2005, 34, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Set | Stimulus Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Set 1 | Verbal Advertisements | Text-based ads describing product features. |

| Set 2 | Product Images | Visual-only stimuli showing product images. |

| Set 3 | Images with Text Descriptions | Product images combined with short textual descriptions. |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | 5-Fold CV | SMOTE (CV) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std | Mean | Std | |||||

| Set 1—Verbal Ads | ||||||||

| SVM | 93% | 90% | 95% | 92% | 0.80 | 0.13 | 0.89 | 0.04 |

| DT | 86% | 83% | 83% | 83% | 0.79 | 0.12 | 0.80 | 0.06 |

| kNN | 86% | 84% | 90% | 85.5% | 0.65 | 0.18 | 0.84 | 0.10 |

| Set 2—Visual Ads | ||||||||

| SVM | 93% | 95.5% | 87.5% | 90.5% | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.03 |

| DT | 99% | 95% | 88% | 91% | 0.77 | 0.16 | 0.86 | 0.03 |

| kNN | 93% | 95% | 87.5% | 90% | 0.78 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.11 |

| Set 3—Mixed Ads | ||||||||

| SVM | 86% | 84% | 90% | 85.5% | 0.83 | 0.07 | 0.84 | 0.05 |

| DT | 98% | 90% | 95% | 92% | 0.79 | 0.13 | 0.88 | 0.07 |

| kNN | 93% | 95.5% | 87.5% | 90.5% | 0.77 | 0.14 | 0.88 | 0.04 |

| Frequency Band | Set | Mean (Verbalizers) | Mean (Visualizers) | T-Statistic | p-Value | Significant () |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.2712 | 0.0268 | Yes | |

| Delta | Set 2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 3.5202 | 0.0012 | Yes |

| Set 3 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.6064 | 0.0116 | Yes | |

| Set 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 3.9145 | 0.0002 | Yes | |

| Theta | Set 2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 4.1294 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Set 3 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.6334 | 0.0106 | Yes | |

| Set 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.6309 | 0.1079 | No | |

| Alpha | Set 2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.1695 | 0.0338 | Yes |

| Set 3 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.2446 | 0.2183 | No | |

| Set 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.1212 | 0.0409 | Yes | |

| Beta | Set 2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.6734 | 0.0118 | Yes |

| Set 3 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.0867 | 0.0432 | Yes | |

| Set 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.3655 | 0.1792 | No | |

| Gamma | Set 2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.0417 | 0.0467 | Yes |

| Set 3 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.2656 | 0.2103 | No |

| Set | Feature | d |

|---|---|---|

| Set 1 (Verbal) | P4_BandTheta | |

| Parietal_Theta | ||

| P8_BandTheta | ||

| Pz_BandTheta | ||

| Set 2 (Visual) | Pz_BandTheta | |

| P4_BandTheta | ||

| O2_BandTheta | ||

| Set 3 (Mixed) | P4_BandTheta | |

| Oz_BandDelta | ||

| O1_BandDelta |

| Set | Feature | Verbalizers (CoV) | Visualizers (CoV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Set 1 (Verbal) | Occipital_Delta | 0.082 | 0.114 |

| Occipital_Theta | 0.055 | 0.085 | |

| Parietal_Theta | 0.046 | 0.091 | |

| Set 2 (Visual) | Occipital_Delta | 0.120 | 0.123 |

| Occipital_Theta | 0.150 | 0.097 | |

| Parietal_Theta | 0.148 | 0.120 | |

| Set 3 (Mixed) | Occipital_Delta | 0.117 | 0.103 |

| Occipital_Theta | 0.183 | 0.094 | |

| Parietal_Theta | 0.103 | 0.094 |

| Stimulus Set | Top EEG Features | Neurocognitive Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Set 1—Verbal Ads | FC5_BandTheta | Verbal processing and attention (left frontal) |

| T8_BandGamma | Right temporal gamma—cognitive effort [71] | |

| FC6_BandGamma | Right frontal gamma—working memory [72] | |

| Set 2—Visual Ads | O1_BandAlpha | Visual cortex—alpha suppression (visual attention) [73,74,75] |

| CP2_BandAlpha | Right parietal alpha—spatial attention processing [76] | |

| CP2_BandTheta | Theta—integrative visual encoding [77] | |

| Set 3—Mixed Ads | PO4_BandTheta | Parieto-occipital theta—multimodal engagement |

| FC6_BandDelta | Frontal delta—attentional shift or integration [78] | |

| F4_BandTheta | Right frontal theta—cognitive control and attention [68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panteli, A.; Kalaitzi, E.; Fidas, C.A. Identifying Individual Information Processing Styles During Advertisement Viewing Through EEG-Driven Classifiers. Information 2025, 16, 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16090757

Panteli A, Kalaitzi E, Fidas CA. Identifying Individual Information Processing Styles During Advertisement Viewing Through EEG-Driven Classifiers. Information. 2025; 16(9):757. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16090757

Chicago/Turabian StylePanteli, Antiopi, Eirini Kalaitzi, and Christos A. Fidas. 2025. "Identifying Individual Information Processing Styles During Advertisement Viewing Through EEG-Driven Classifiers" Information 16, no. 9: 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16090757

APA StylePanteli, A., Kalaitzi, E., & Fidas, C. A. (2025). Identifying Individual Information Processing Styles During Advertisement Viewing Through EEG-Driven Classifiers. Information, 16(9), 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16090757