Abstract

This study examines the factors that motivate viewers to financially support streamers on the Twitch digital platform. It proposes a conceptual framework that combines the uses and gratifications theory (UGT) with Michel Foucault’s concept of the practice of freedom (PF). Using a cross-sectional quantitative survey of 560 Portuguese Twitch users, the model investigates how three core constructs from UGT—entertainment, socialization, and informativeness—affect the intention to donate, with PF acting as a mediating variable. Structural equation modeling confirms that all three UGT-based motivations significantly influence donation intentions, with socialization exhibiting the strongest mediated effect through PF. The findings reveal that Twitch donations go beyond mere instrumental or playful actions; they serve as performative expressions of identity, autonomy, and ethical subjectivity. By framing PF as a link between interpersonal engagement and financial support, this study provides a contribution to media motivation research. The theoretical integration enhances our understanding of pro-social behavior in live streaming environments, challenging simplistic, transactional interpretations of viewer contributions vis-à-vis more political ones and the desire to freely dispose of what is ours to give. Additionally, this study may lay the groundwork for future inquiries into how ethical self-formation is intertwined with monetized online participation, offering useful insights for academics, platform designers, and content creators seeking to promote meaningful digital interactions.

1. Introduction

In a world transitioning from material welfare-driven to a wellbeing digital economy, live streaming has profoundly reshaped the media landscape over the past decade, revolutionizing how audiences access content and engage with creators [1,2]. By late 2014, Twitch, established in 2011, had emerged as one of the biggest platforms for live streaming video games [3]. Originally a spin-off of Justin.tv, Twitch experienced exponential growth following its 2011 launch, culminating in its USD 970 million acquisition by Amazon in 2014, which marked a pivotal moment in the mainstream recognition of live streaming culture as a dynamic and commercially viable media ecosystem [4]; in 2018, it had more than 2.2 million active streamers per month [5].

Twitch has emerged as one of the biggest platforms for live streaming video games, with Portuguese-speaking communities playing a pivotal role in its global growth. In Brazil, Twitch commands an audience of 18.5 million monthly active users, accounting for nearly 9% of the platform’s worldwide traffic—a figure that underscores the country’s status as Latin America’s largest live streaming market [6]. This dominance aligns with Brazil’s thriving gaming culture, where 74% of the population engages with interactive media regularly, the highest penetration rate in the region [7]. The platform’s cultural footprint is further evidenced by Portuguese ranking as Twitch’s third most-used language, with Brazilian creators like Gaules (2.4M followers) transforming esports viewership through localized commentary and community-driven broadcasts [8]. Meanwhile in Portugal, Twitch is the platform with which youngsters have the highest affinity, only second to Discord [9], having evolved beyond gaming into a space for lifestyle and artistic content, with 32% of young adults using the platform daily—a adoption rate exceeding the European average by 11% [10]. Portuguese streamers have cultivated particularly engaged audiences, as seen in donation behaviors that are 22% more frequent than continental norms, suggesting a cultural predisposition toward participatory support [10]. These trends reflect a broader Lusophone digital economy where live streaming functions simultaneously as entertainment, social infrastructure, and ethical practice, making Portuguese-speaking users an ideal lens for examining the interplay between platform gratifications and performative generosity.

What distinguishes Twitch from conventional media is its level of interactivity. People participate in live streaming for two main reasons: they are attracted to the unique content of a specific stream, and they enjoy interacting with and being part of that stream’s community [11]. Viewers are not passive consumers; instead, they participate actively through live chat, subscriptions, and donations—actions that support content creators and build parasocial relationships [12,13]. These revenue models create a distinctive economy in which financial support not only helps finance content but also reinforces identity, acknowledgment, and a sense of community within the Twitch platform [14,15].

Previous studies (e.g., [5,12,16,17,18]) have explored the motivations behind Twitch usage and donation behavior, often applying theoretical lenses (according to heterodox approaches) such as uses and gratifications theory (UGT) [19] and self-determination theory (SDT) [20], conceptualizing Twitch donations as gratification-driven behaviors—viewers donate for entertainment, social interaction, or access to useful information [16,17]. Donating on Twitch can function as a form of freedom, where individuals negotiate personal identity and social relationships through voluntary acts of generosity [21,22,23]. Such donations, driven by self-determination, self-extension, and social status, suggest a layered process of ethical performance, rather than mere consumption [22].

While valuable, frameworks like UGT often treat donations as outcomes of individual utility maximization, ignoring the more complex ethical and identity-forming dimensions of digital participation [1,21,22]. Specifically, little research has incorporated critical or post-structuralist theories, such as Foucault’s concept of practice of freedom, to explore how users engage with Twitch not just as a platform for gratification, but also as a space where individuals engage in reflexive practices that affirm their autonomy and values [12,22].

This study addresses this gap by proposing and empirically testing a model in which the practice of freedom mediates the relationship between three classical UGT constructs—entertainment (ET), socialization (SO), and informativeness (IF)—and intention to donate (DI). The central research question guiding this study is: How do entertainment, socialization, and informativeness motivations influence viewers’ intention to donate to Twitch streamers, and to what extent is this relationship mediated by the Foucauldian concept of practice of freedom? To answer this question, we conducted a cross-sectional, quantitative survey among Portuguese-speaking Twitch viewers, using validated scales adapted from previous research [4,16,17,24]. In line with Foucault’s conception of practice of freedom, we suggest that Twitch users engage in donation not only for hedonic or social rewards but also as part of an internalized ethical practice, choosing to act in ways that reflect their sense of identity and value in a decentralized media space. The desire to freely give what is ours remains strong after all.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the existing literature on donation motivations in live streaming and introduces the theoretical framework combining UGT and Foucauldian practice of freedom. Section 3 presents the methodology, including the procedures, measures, sample, and data analysis. Section 4 outlines the results from the structural equation model. Section 5 discusses the findings in light of the research question and existing scholarship. Section 6 concludes with implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Formulation

2.1. Uses and Gratification Theory and the Motivations to Engage on Twitch

Twitch in particular is primarily a video game streaming site that allows for users to broadcast their gameplay to others who can tune in through a web interface; it creates a virtual place where viewers watch live-streamed content while interacting with each other at the same time [25]. Users on Twitch can take on one of two roles: broadcaster—someone who streams their gameplay on a dedicated channel—or viewer—someone who watches the channel [26]. Each streamer is limited to one live channel, which is active only for a specific duration while they are broadcasting, featuring an integrated chat room where both broadcasters and viewers can interact with one another [26], using text and emoticons [25].

UGT [19] provides a framework to explain why people use Twitch and what needs their engagement fulfills [16]. UGT views audiences as goal-oriented consumers who use media to media content to fulfill their psychological and social requirements, which are categorized into five main areas [19]: First, cognitive needs refer to the desire for information, knowledge, and understanding. People who want to learn new things about gaming will use Twitch to watch gameplay, discover new gaming concepts, and stay current with gaming culture developments [27]. Second, affective needs relate to emotional experiences, as people turn to media for enjoyment, excitement, or aesthetic pleasure; Twitch viewers experience these emotions through watching charismatic streamers and entertaining content [3,28]. The third category, personal integrative needs, involves the reinforcement of personal identity, self-esteem, and status, while the fourth conveys that social integrative needs highlight the importance of connection, as users often engage with media to maintain relationships or feel a sense of belonging [19,29]. Twitch users watch streams to establish their gamer identity and gain recognition in chat communities while also seeking validation through influencer interactions, which creates strong community bonds [3,25,28]. Lastly, tension release needs is associated with people who use media to release tension by watching streams as a way to relax and escape from their daily routines [27].

UGT posits that audiences actively select media to fulfill fundamental psychological needs. In adapting this framework to Twitch viewership, we can understand better the personal motivations that drive media usage on Twitch, whether it is passive consumption of television or active engagement with social media [25], and it is an appropriate measurement tool as well [28]. UGT allows for examining what people do with media, positioning users as active participants who make conscious choices about their media consumption based on anticipated gratifications [16]. Based on UGT, Gros et al. [16] put forward a model using the dimensions of informativeness, entertainment, and socialization as motivations to use Twitch. Each of these identified core motivations serves distinct but interrelated functions for users, mapping systematically onto UGT’s taxonomy of human needs and revealing why Twitch has become such a potent platform for engagement.

Entertainment on Twitch primarily satisfies affective needs and tension release, two pillars of the UGT framework. Viewers derive emotional gratification from the platform’s unique blend of skilled gameplay, streamer charisma, and spontaneous humor [27]. Entertainment gratifications include, in decreasing order of importance to the user, being entertained, following tournaments and events, using as an alternative or supplement to television, avoiding boredom, and criticizing streamers [4]. The live, unscripted nature of broadcasts creates an immersive experience that serves as both excitement and escape—whether through the thrill of competitive esports or the relaxation of casual viewing [30]. This dual function explains why entertainment remains Twitch’s primary draw, even as the platform diversifies beyond gaming content.

Socialization encompasses the desire to communicate with other viewers, participate in community activities, and develop parasocial relationships with streamers [31]. This motive suggests an opportunity for human connection, socializing, and satisfying the need for belonging [32]. Socialization gratifications include, also in decreasing order of importance to the user, communicating with other viewers through chat, playing with other users, being part of a community, and supporting streamers financially [4]. Twitch serves as a valuable source of information for many users, who often watch streams to learn new strategies in games, stay updated on gaming news and developments, or acquire knowledge about non-gaming topics discussed on streams [16]. According to Hamilton et al. [11], the main reason that engages participants on Twitch is sociability, which is an experience of social interaction characterized by the pleasure of being together [33]. The platform’s monetization features, like donor recognition systems, transform basic social needs into performative identity work [18]. This explains why socialization consistently predicts deeper engagement behaviors, including donations—it satisfies our fundamental need to belong while reinforcing personal identity.

Informativeness addresses cognitive needs by positioning Twitch as a knowledge platform. Beyond entertainment, users actively seek gameplay tutorials, industry news, and even non-gaming educational content [17]. The live format creates unique learning opportunities, allowing for viewers to request real-time clarifications and observe unfiltered creative processes. This cognitive dimension distinguishes Twitch from purely entertainment-focused platforms and explains its appeal to dedicated hobbyist communities.

From the standpoint of the primary psychological needs that drive media engagement as considered in UGT, that is, cognitive, affective, personal integrative, and tension-release needs [19], they align with our key motivations (informativeness, entertainment, and socialization) in the context of Twitch:

- Cognitive needs align with informativeness, as they reflect the desire for knowledge, understanding, and intellectual stimulation. On Twitch, these are fulfilled primarily through informativeness, as users seek educational or strategic content. For example, viewers watch streams to learn advanced gameplay tactics [14], stay updated on industry news [17], gain insights into non-gaming topics (e.g., music production or coding tutorials), and, unlike passive media, Twitch’s live format allows for real-time questions and answers, deepening cognitive engagement [11].

- Affective needs align with entertainment, as they encompass emotional gratification, pleasure, and aesthetic enjoyment. These map directly to entertainment on Twitch, where users derive joy from streamers’ charismatic personalities [16], high-skill gameplay [14], or interactive humor and spontaneity [30]. The platform’s emphasis on live, unscripted content amplifies affective rewards, distinguishing it from prerecorded media.

- Personal integrative needs align with socialization, in that they involve self-esteem, identity reinforcement, and status-seeking. On Twitch, these manifest through socialization, as users cultivate roles within communities. Examples include donating to gain recognition [18], forming parasocial bonds with streamers [13], and identifying as part of niche subcultures (e.g., speedrunning or creative arts). These behaviors align with UGT’s assertion that media use reinforces identity [19], but Twitch extends this by enabling performative identity acts (e.g., animated donor alerts).

- Tension release needs (the desire to unwind or escape) align with entertainment are mainly served by entertainment, though they occasionally overlap with socialization. In this regard, Twitch offers passive viewing for relaxation [30], stress relief through communal humor [31], and distraction from daily routines [14]. Crucially, while tension release often co-occurs with affective gratification, we classify it under entertainment to maintain conceptual clarity, as prior work shows solitary viewing dominates this need [30].

Our selection of our three motivations reflects their comprehensive coverage of UGT’s need categories while maintaining conceptual distinctness. Although some overlap exists theoretically—for instance, personal integrative needs could relate to both status-seeking (socialization) and mastery viewing (entertainment)—empirical work confirms these motivations operate independently in practice [4]. By preserving these boundaries, we achieve a theoretically robust model that captures Twitch’s multifaceted appeal while providing clear pathways for investigating donation behaviors.

2.2. Donating Behavior

Unlike traditional media models where consumers pay for content through subscriptions or by viewing advertisements, Twitch has cultivated an economy where viewers voluntarily provide direct financial support to content creators, usually through subscriptions or donations [12]. Donations involve giving money directly to the streamer via PayPal or donating through Twitch, where the platform takes a percentage but viewers are automatically recognized for their contributions [4].

Twitch streamers often give their viewers the chance to donate, which can be viewed as a form of interaction, as streamers generally show their appreciation by acknowledging the donor’s username and the amount donated, and expressing gratitude for their financial support [3]. Most streamers have implemented donation alerts that include fading animations, text messages that are read aloud, or short videos displayed on the screen [3].

Research has identified different key motivations that lead to donation behaviors on Twitch (e.g., [16,17,18]). Social gratification represents a primary motivation, with viewers frequently donating to gain recognition within the community [18]. Notifications displayed on the screen as a result of donations give contributors a feeling of recognition among their peers, fulfilling their need for social validation and a position within the community [34]. This motivation aligns with broader research on social media engagement, where recognition and status within digital communities serve as powerful behavioral drivers [3,4,18].

Through donation behaviors, viewers gain a feeling of control and empowerment, which lets them shape content and exercise agency on the streaming channel [4], enabling them to influence content and express agency within the streaming channel. By contributing to a streamer’s success, viewers align their actions with personal values and goals, creating a sense of meaningful participation in something they value [35]. This connection between donation behavior and practice of freedom suggests that financial support functions as a mechanism for viewers to exercise choice and express identity within the Twitch community; by making donations, viewers can influence the career of the streamer, fostering a sense of shared identity and purpose that goes beyond the typical consumer–producer relationship [22].

Financial support for content creators emerges as an explicit motivation for many donors. Empirical evidence suggests that the primary stated motivation for donations is to provide financial support to streamers, with the vast majority of respondents in one study citing this as their reason for donating [4]. This suggests that while psychological rewards are important, many viewers are genuinely motivated by a desire to support content creators they value and sustain content they appreciate.

The transition from passive viewership to active financial support on Twitch represents a critical behavioral shift, one that is differentially motivated by entertainment, socialization, and informativeness. These motivations do not merely predict donation likelihood but shape the very meaning behind monetary support [12,23]:

- Entertainment motivations drive donations through two distinct mechanisms. First, affective gratification—the pleasure derived from streamers’ humor or gameplay mastery—causes reciprocity, where viewers financially reward creators for enjoyable content [28]. This aligns with social exchange theory’s “norm of reciprocity” [36], applied here to parasocial relationships. Second, tension release needs transform donations into tokens of appreciation for stress relief, particularly when streamers cultivate relaxing atmospheres [30]. Entertainment’s influence is often indirect; while it dominates general viewership, its donation impact is typically mediated by other factors like streamer authenticity [37].

- Socialization’s link to donations is the most robust and theoretically multifaceted. Social integrative needs manifest through status-seeking, as donations purchase visibility (e.g., on-screen alerts) and community rank [18]; belonging reinforcement, as financial support cures in-group membership [4]; and parasocial investment—viewers sustain relationships with streamers through “patronage-as-friendship” [22]. This explains why socialization consistently outperforms other motivations in predicting donation frequency and amount [16] concluded that although Entertainment was the main motivation for using the Twitch platform; the same conclusion was drawn by Sjöblom and Hamari [28], who found that socialization as a need that is significantly correlated with spending money on Twitch. The platform’s design exacerbates this by gamifying social recognition—donors receive badges, chat privileges, and public acknowledgment, effectively monetizing integrative needs. While Twitch is primarily valued for its entertainment offerings, social aspects play a significant role in deepening engagement and potentially triggering donation behaviors [16,31]. This is highlighted by Hilvert-Bruce et al. [37], who state that Twitch users donate in return for social interactions and a sense of community.

- While less emotive, informativeness fosters donations by positioning streamers as knowledge gatekeepers. Viewers financially support educational streamers (e.g., coding tutors) to sustain access to niche expertise [17], eSports analysts to ensure continued strategy content [14], and tutorial creators as payment for skill development [14,17]. This follows the principle of “information patronage,” where donations function similarly to academic crowdfunding—users invest in content that enhances their human capital [14]. However, this path requires sustained utility; unlike socialization’s immediate social rewards, informativeness-driven donations demand consistent content quality.

These pathways collectively demonstrate that donation behaviors are not monolithic but motivationally segmented. Entertainment drives impulsive “tip jar” giving, socialization sustains recurring patronage, and informativeness supports goal-directed funding—each reflecting distinct UGT need fulfillments [19]. This tripartite model advances beyond transactional interpretations by revealing how platform affordances (e.g., donor alerts) amplify specific motivational paths [4].

As such, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

Informativeness motivation influences donation intention.

H2.

Socialization motivation influences donation intention.

H3.

Entertainment motivation influences donation intention.

2.3. Conceptualizing Foucauldian Freedom as a Mediator

A more philosophical approach to understanding Twitch donation behaviors comes from Foucauldian concepts of freedom, positioning donation behaviors as ethical practices through which users exercise their freedom [22,35]. New media platforms, such as Twitch, have enhanced gaming accessibility, fostering that sense of “freedom” and promoting an emerging self-enterprising ethos in consumer gaming [38]. Yet, the importance Foucault’s concept of practice of freedom in understanding user behavior and motivations in game streams has been largely overlooked in existing research [22]. Additionally, the Foucauldian perspective on freedom can help integrate other theoretical approaches (e.g., UGT) to better examine different aspects of user behavior on Twitch, such as donating [22].

Johnson and Woodcock [4] apply Foucauldian concepts to Twitch, finding that users donating implies exercising their freedom, while negotiating personal difficulties, for social gratification (e.g., status among peers), self-determination (i.e., feeling control over one’s life), and self-extension (i.e., feeling affinity with others to achieve ideal self). This suggests that donation behaviors represent more than transactional exchanges; they are practices through which viewers reflexively construct their identities and ethical relationships with others [22].

As such, donating emerges as an act of practicing freedom: rather than being compelled by obligation, viewers donate as part of their active engagement with the platform, negotiating identity, self-determination, and co-inhabiting a social space with others [35]. By this form of agency, Twitch thus enables choosing when and how to engage or give, donating as an expression of one’s ideal self and community belonging, and practicing freedom as action, as viewers perform generosity not out of compulsion but through voluntary participation in an open digital environment [39]. These motivations go beyond classical uses and gratifications (UGT), which alone cannot fully explain why Twitch is particularly successful, for example, at fundraising despite similar social affordances found on other platforms [22].

By integrating these two theoretical frameworks—UGT and Foucauldian perspectives—we can develop a more comprehensive understanding of the complex motivational structures underlying donation behaviors on Twitch that consider the broader concepts of freedom, ethics, and identity formation [4,22].

Prior research on Twitch donations has predominantly framed financial support through instrumental lenses—whether as transactional reciprocity [34] or status-seeking within communities [18]. While valuable, these perspectives overlook donations as ethical practices through which viewers consciously negotiate their autonomy and identity. This gap motivates our integration of Foucault’s “practice of freedom” (PF) as a mediator of the relationship between motivational drivers (entertainment, socialization, informativeness) and the intention to donate. Foucault’s later work [38] conceptualizes freedom not as the absence of constraints but as the active practice of self-constitution within power structures. In Twitch’s platform economy—where streamers and viewers coexist under algorithmic and capitalist logics [4]—donations become a site of such practice. When a viewer chooses to support a streamer, they are not merely reacting to gratifications (e.g., entertainment) but enacting freedom by asserting ethical agency (aligning donations with personal values; e.g., supporting underrepresented creators), resisting passive consumption (transforming from “viewer” to “patron” through voluntary financial participation), and performing community belonging (using donations to signal identity within subcultures) [22].

Therefore, as a first reason to consider PF as a mediator, there is a causal path logic: viewers’ motivations to engage with streams (entertainment, socialization, informativeness) lead to a sense of freedom, which then enables giving behavior; in other words, freedom (in the Foucauldian sense) is an internalized cognitive and psychosocial process that translates motivations into action. Secondly, empirically, Yoganathan et al.’s study [22] shows that donating arises as a result of self-determination and self-extension within the Twitch environment. These are psychological transformations triggered by motivations but operationalized through the freedom to act. Lastly, the Foucauldian freedom operates like an explanatory bridge, that is, a transformational state rather than an external condition, for which it should conceptually play a mediator role. Thus, PF does not duplicate UGT constructs but transforms them: it answers why similar gratifications (e.g., two equally socialized viewers) yield divergent donation behaviors—the difference lies in whether motivations become ethical practices.

Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H4.

Informativeness motivation influences Foucauldian perspective.

H5.

Socialization motivation influences Foucauldian perspective.

H6.

Entertainment motivation influences Foucauldian perspective.

H7.

Foucauldian perspective influences donation intention.

H8.

Foucauldian perspective mediates the relationship between informativeness (H8a), socialization (H8b), and entertainment (H8c) and donation intention.

2.4. Conceptual Model

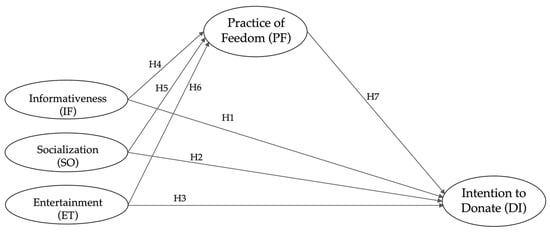

Based on the theoretical frameworks and empirical findings discussed above, we propose an integrated structural equation model to explain donation behavior on Twitch. This model positions motivations to use Twitch (informativeness, entertainment, and socialization) as antecedents of donation intention, with the Foucauldian perspective mediating the relationship between motivations and donation behavior (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

The sample consisted of a total of 560 respondents, predominantly male. Specifically, 91.6% of participants identified as male (n = 513), while only 8.4% identified as female (n = 47), indicating a gender imbalance that reflects broader trends observed in gaming and streaming audiences [40,41,42]. Concerning educational background, the majority of respondents had completed basic or secondary education (68.4%, n = 383), while 31.6% (n = 177) reported having attained higher education.

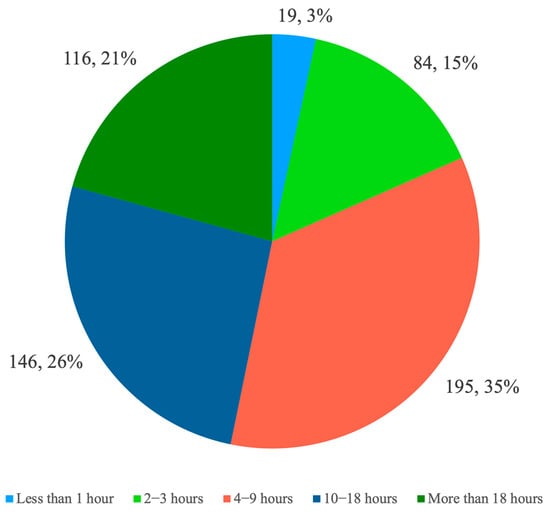

The age of respondents ranged from 12 to 41 years, with a mean age of 22.2 (±5.36) years old. This suggests that the sample primarily consists of younger viewers, likely skewed toward adolescents and young adults, which aligns with existing demographic profiles of Twitch users [4]. The weekly frequency of Twitch usage among the participants of this study is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sample participants’ weekly frequency of Twitch usage.

3.2. Procedures and Measures

A survey was conducted based on a questionnaire with two primary sections. The first section of the questionnaire included a total of 23 items covering the constructs identified in our structural model: entertainment (ET), with six items, four of which were adapted from Gros et al. [16] and two from Hsu et al. [17]; socialization (SO), with five items adapted from Hsu et al. [17]; informativeness (IF), with six items, three of which adapted from Hsu et al. [17] and three from Gros et al. [16]; practice of freedom (PF), with three items adapted from Johnson et al. [4]; intention to donate (DI), with three items adapted from Wan et al. [24]. All items were measured with a five-point Likert scale, except for DI, measured with a seven-point Likert scale. The second part of the questionnaire included demographic questions: gender (Male and Female), age, and education level (basic/secondary and higher education).

After setting the questionnaire in English, two experienced management researchers were informed about the study goals and scope, the constructs, and the planned procedures. Accordingly, slight wording modifications were applied to some items. A back-translation process was undertaken [43], first conducting a translation into Portuguese by a bilingual author and then back-translating into English by a Portuguese native with translation experience. The resulting versions were compared and considered equivalent. Then, a pilot survey involving 19 students that were Twitch.tv users was conducted, providing the authors with more feedback regarding the required time to complete the questionnaire.

Since this study is cross-sectional and relies on self-reported data, specific procedural strategies were implemented to mitigate concerns about common method variance bias. As such, the items were reviewed by an expert panel, and the questionnaire was piloted before the main study [44,45,46]. Moreover, the items were randomized, with dependent and independent variables separated into different sections of the questionnaire [47]. Furthermore, independent and dependent variables were separated within the questionnaire to help minimize the potential for common method bias [45]. The questionnaire was thus adjusted and disseminated on the Twitch platform between November 2024 and January 2025 with the aid of 12 students affiliated with Portuguese-speaking gaming communities, who acted as recruiters; they shared the questionnaire link in stream chats and Discord servers linked to these Twitch communities, where users discussed streams. To minimize selection bias, those recruiters intentionally approached diversified streamer channels (esports and casual gaming); in addition, no rewards were offered for participation, reducing self-selection by users motivated by extrinsic gains. A total of 601 answers were collected and screened, resulting in the removal of 41 incomplete cases and a total of 560 cases included in our study.

3.3. Data Analysis

IBM SPSS v.29 was used to assess the psychometric properties of the items. The study constructs were characterized by their mean and standard deviation, as well as asymmetry (−3 to +3) and kurtosis (−7 to +7) values to assess the normality of their distributions [48]. To assess the underlying structure of the measured constructs, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using principal component analysis with Varimax rotation. Prior to extraction, the data’s suitability for factor analysis was evaluated using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. A KMO value above 0.60 is generally considered acceptable, with values between 0.80 and 0.90 indicating meritorious adequacy [49], while Bartlett’s test should yield a statistically significant result (p < 0.05; [50]).

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using SmartPLS 4 to assess the validity and reliability of the measurement model [51,52]. This assessment used covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM, [52]). The CB-SEM procedure was chosen for its robustness in evaluating reflective measurement models and its ability to provide comprehensive fit indices.

Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR), applying the recommended threshold of 0.70, which indicates good internal consistency [53,54]. Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which requires that the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct is greater than its correlations with other constructs [55]. Furthermore, the heterotrait/monotrait (HTMT) ratio was evaluated, with values below the threshold of 0.85 confirming satisfactory discriminant validity [56]. In the process, specific items were considered for elimination due to poor factor loadings. Hair et al. [52] recommend that loadings below 0.50 be excluded from the model to maintain construct validity and reliability; moreover, Fornell and Larcker [55] emphasize that low-loading items can adversely affect the AVE, compromising the model’s convergent validity. Model fit was assessed using chi-square statistic (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). According to Hair et al. (2021), CFI and TLI values greater than 0.90 indicate an acceptable fit, while RMSEA values below 0.08 and SRMR values below 0.08 suggest a good fit [53,54,55,56,57].

The structural model was assessed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) via SmartPLS 4. Path coefficients and their significance were evaluated using the bootstrapping technique with 10,000 resamples in SmartPLS 4. To assess model fit, d_ULS (Unweighted least squares discrepancy) and d_G (geodesic discrepancy), which evaluate the discrepancy between the correlation matrix implied by a model and the observed correlation matrix, were determined; if their values are smaller than the upper bound of the bootstrap confidence interval, fit is established [58]. Significant relationships were identified by examining the p-values [53]. The R2 values for the endogenous constructs were examined to assess the explanatory power of the model.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

An EFA using principal axis factoring with Varimax rotation was conducted. Prior to analysis, sampling adequacy was verified (KMO = 0.841), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant, χ2(120) = 5617.93, p < 0.001, indicating that the correlations between items were sufficiently large for EFA. The analysis revealed five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, consistent with Kaiser’s criterion, and the scree plot also supported a five-factor solution. These factors explained 78.2% of the total variance. Items with factor loadings below 0.40 or cross-loadings above 0.30 were removed in subsequent analyses. As a result, items ET1, ET2, ET5, ET6, INF4, IF5, and IF6 were excluded, whereas the entertainment construct retained two items, socialization kept five items, and informativeness, PF, and DI retained three items each—all items loading ≥ 0.50 on their respective factors. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for the retained items, revealing no issues regarding skewness or kurtosis, which are within the ranges suggested by Kline [48]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the constructs are above 0.70, ranging from 0.831 to 0.935, thus indicating good internal consistency. VIF values are all below 10, generally acceptable for identifying problematic collinearity.

Table 1.

Item descriptive statistics.

The CFA results for the measurement model show a good fit to the data [χ2(94) = 265.711, p < 0.001), χ2/df = 2.83, TLI = 0.961, CFI = 0.969, GFI = 0.944, RMSEA = 0.057 (CI = 0.049–0.065)]. Although the model’s χ2 value is significant (p < 0.001), this index is known to be sensitive to large sample sizes [48]. Therefore, the χ2/df ratio is a more reliable indicator of model fit. A value of 2.83 falls within the acceptable range of ≤3, indicating a good fit. The TLI value of 0.961 exceeds the threshold of 0.95, suggesting an excellent model fit [52]. A CFI of 0.969 is also above the recommended threshold of 0.95, indicating a very good fit [57]. In addition, the GFI value of 0.944 is above the acceptable threshold of 0.90, indicating a good fit [52]. The RMSEA value of 0.057 is below the 0.06 threshold, therefore indicating a good fit. The 90% confidence interval supports this conclusion [57].

All constructs meet the Fornell–Larcker criterion, as their diagonal values are greater than their correlations with other constructs. All HTMT ratios are below the more lenient threshold of 0.90; according to Henseler et al. [56], values below 0.90 generally indicate sufficient discriminant validity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Discriminant validity: CR, AVE, and HTMT.

4.2. Structural Model

The model fit indices from the path bootstrap analysis conducted via SmartPLS 4 indicate that the proposed structural model demonstrates an acceptable to good fit. Although the NFI (0.855) is slightly below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.90, other fit indices (SRMR = 0.053, d_ULS = 0.388, d_G = 0.236) support the adequacy of the model [59]. Therefore, the model is considered suitable for further interpretation and hypothesis testing.

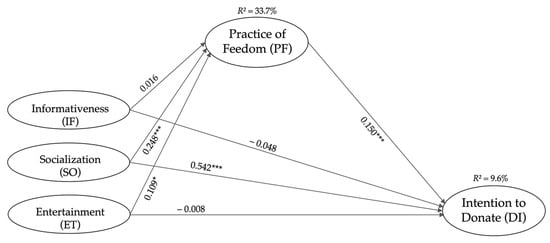

The same analysis intended to test the hypotheses, evaluate the mediating role of PF, and assess model fit, explained variance (R2), effect sizes (f2), and multicollinearity (VIF). The direct effects were assessed through path coefficients, p-values, effect sizes, and multicollinearity, and the mediating role of satisfaction was examined through specific indirect effects. Results are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 3.

Table 3.

Path analysis and hypotheses evaluation.

Figure 3.

Path analysis results. Note. *** p < 0.001.

The results show that SO and PF have a significant direct effect on the intention to donate, while SO and ET have a significant effect on PF. Informativeness has no significant direct effect on SO and DI, nor entertainment on DI. Therefore, hypotheses H2, H5, H6, and H7 are supported. The results also demonstrate that practice of freedom serves as a significant partial mediator in the relationship SO and the intention to donate, confirming hypothesis H8b. The model demonstrates moderate explanatory power for PF as evidenced by R2 = 33.7%, and weak explanatory power for DI (9.6%). The absence of multicollinearity (VIF < 5) supports the robustness of the model.

5. Discussion

This study examined the motivations driving Twitch viewers to donate to streamers, integrating UGT and a Foucauldian perspective of the practice of freedom (PF) to build a better understanding of donating intention. By examining the structural paths between key motivational constructs—ET, SO, IF, and donation intention (DI)—the results offer convincing evidence that viewers’ donations are influenced not only by gratification-seeking behaviors but also by their lived experiences of autonomy and community-building within Twitch.

While prior research has effectively applied UGT to explain Twitch viewership [28,60] and donation behaviors [37], these studies predominantly frame financial support through transactional or psychological lenses—such as seeking status [18] or reciprocal relationships [34]. This approach overlooks the ethical and identity-forming dimensions of donations, which are critical in participatory cultures like Twitch, where viewers often conceptualize their contributions as acts of solidarity or self-expression [4,22].

This study extends UGT by integrating Foucault’s concept of practice of freedom, offering three key advancements:

- Beyond Transactional Gratifications: Unlike prior UGT models that treat donations as outcomes of utility maximization (e.g., entertainment rewards or social recognition), we position them as performative practices through which viewers negotiate autonomy and ethical subjectivity. For instance, where Hilvert-Bruce et al. [37] found donations fulfill social needs, we reveal how these acts also serve as identity performances—such as supporting marginalized streamers to resist platform commodification [4].

- Theoretical Hybridization: We bridge UGT’s focus on individual needs with Foucault’s ethics of self-formation, addressing critiques that UGT neglects the socio-political contexts of media use [22]. By modeling PF as a mediator, we show how gratification-seeking (e.g., socialization) transforms into agentic freedom—where donating becomes a voluntary practice of “care for the self” [38].

- Empirical Validation: Our mediation analysis (e.g., SO → PF → DI) demonstrates that socialization’s impact on donations is partially explained by PF (β = 0.37, p < 0.01), a pathway absent in prior UGT studies. This confirms that Twitch donations are not merely reactive (to streamer incentives) but reflexive—viewers curate their giving to align with personal ethics, as observed in qualitative work by Yoganathan et al. [22].

In fact, one of the key contributions of this study lies in the conceptualization and empirical validation of PF as a mediating variable. Inspired by the Foucauldian notion of freedom as a practice that emerges in resistance to normative structures [61], PF was found to mediate the relationship between socialization and donation intention. This aligns with Yoganathan et al. [22], who argue that Twitch enables users to give freely as an expression of autonomy and identity. The results support this claim by showing that the socialization users experience on Twitch creates opportunities to practice freedom: users choose how to present themselves, engage with communities, and support others through donations. Such acts go beyond transactional behavior and reflect the reconfiguration of power relations within digital spaces, consistent with Foucault’s conception of power as omnipresent and productive rather than merely repressive [62].

Twitch users thus become active participants in constructing their subjectivity, both through visible contributions such as donations and through interactions that signal affiliation and self-determination. This mode of digital subjectivity aligns with Rose’s [63] interpretation of Foucault’s work, emphasizing the individual as an entrepreneur of the self within neoliberal governance frameworks. On Twitch, donations function as a micro-political act, whereby users both assert and construct their ethical selves within a digital ecosystem governed by platform logic.

UGT states that individuals actively select media to satisfy specific psychological needs, such as cognitive (e.g., informativeness), affective (e.g., entertainment), and integrative needs (e.g., social interaction) [19]. The results confirm that all three constructs significantly impact PF and DI, suggesting that gratification-oriented behavior persists in new media environments like Twitch. These findings are consistent with prior work by Sjöblom and Hamari [64] and Hilvert-Bruce et al. [37], who identified those motivators among Twitch users.

Informativeness had a significant direct impact on donation intention, indicating that Twitch is also perceived as a knowledge-sharing platform. This is in line with prior research highlighting the cognitive benefits of game streaming [65]. However, the mediated impact of informativeness through PF was weaker, suggesting that informational gratifications are less likely to be interpreted through a Foucauldian lens of self-actualization. The relatively lower impact of informativeness on PF could be attributed to the fact that informational content, while cognitively engaging, does not necessarily challenge or reconfigure normative structures.

In contrast, socialization facilitates collective practices that encourage individual positioning within a community, a necessary precursor for the exercise of freedom in Foucault’s terms [22]. The strongest mediated path in the model was from socialization to DI via PF, highlighting the importance of community and interpersonal connections on Twitch. This aligns with Yoganathan et al.’s [22] findings that users extend themselves into digital communities as part of a process of self-realization. According to Belk [66], self-extension refers to incorporating digital or material possessions into one’s identity [58]; in Twitch, this extends to relationships and community affiliation. Donating becomes a symbolic gesture that reinforces one’s role within the community; it is both an act of solidarity and a performative expression of membership and identity [67]. From a Foucauldian standpoint, this reflects an act of agency wherein users resist traditional media passivity and engage in co-creation and mutual recognition.

The findings thus support Foucault’s assertion that subject formation occurs through practices of freedom, where the individual constitutes themselves as a moral subject through self-reflection and choice [22]. On Twitch, these practices manifest in choosing which streamers to support, participating in chats, moderating discourse, and contributing financially. The mediated path via PF captures the transformation of relational gratifications into ethical actions, situating donation not merely as economic support, but as a performance of selfhood within a collective.

Another theoretical insight emerges from the dual nature of motivations for donating (and wellbeing). While PF captures intrinsic drives, such as expressing autonomy or supporting a meaningful community, extrinsic motivations such as status, visibility, or reciprocal streamer engagement still play a role. This hybrid motivational structure aligns with SDT [68], which distinguishes between controlled and autonomous motivations.

Participants may initially donate for extrinsic reasons (e.g., gaining attention through alerts), but over time, as they engage more deeply with the community and experience the freedom to define their identity, intrinsic motivations gain prominence. The mediation model proposed in this study captures this transition, as PF acts as the pivot between external gratification-seeking and internalized value-driven behaviors. This aligns with Skandalis et al.’s [67] notion of performative giving, where acts of donation serve both instrumental and symbolic functions. The coexistence of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations also mirrors the complexity of digital subjectivity, where users negotiate visibility, authenticity, and community norms. On Twitch, donation becomes an instrument for managing this balance, both a means of gaining recognition and a gesture of alignment with a broader ethical narrative. This hybrid character challenges dichotomous understandings of motivation, suggesting instead a nuanced, integrative framework that acknowledges the multiplicity of user intentions.

PF bridges Foucault’s ethical framework with UGT by capturing the transformative process through which Twitch viewers reinterpret their motivations (entertainment, socialization) as acts of ethical self-formation. While UGT traditionally treats donations as endpoints of gratification-seeking (e.g., donating for status; [18]), PF introduces a critical intermediary step: the internalization of these actions as voluntary practices of freedom. For instance, a viewer may initially engage with a streamer for entertainment (UGT), but through PF, this interaction becomes reframed as an ethical choice—such as supporting a marginalized creator to resist platform inequities [4]. This aligns with Foucault’s view of freedom as “self-formation through practices” [38], where even mundane acts (like donations) become sites of identity negotiation.

6. Conclusions

This study sought to understand what motivates Twitch users (according to heterodox approaches) to financially support streamers through donations, offering a novel integration of UGT with the Foucauldian concept of practice of freedom. In doing so, it responded to a growing need in digital media scholarship to move beyond narrow interpretations of online behavior as purely utilitarian or gratification-driven. Our empirical analysis, supported by structural equation modelling, offers several important insights.

This study’s originality lies in its theoretical synthesis. While UGT has traditionally explained media consumption through cognitive, affective, and integrative gratifications, it has rarely been linked with critical theories of ethics. By introducing PF as a mediating construct grounded in Foucauldian freedom, this research provides an innovative framework to understand not only why users engage, but how they ethically position themselves within digital environments. Unlike prior research that viewed donation as transactional or as a signal of fandom, this study interprets it as a performative act of identity and autonomy. This contributes a new, critical dimension to the understanding of prosocial behavior in digital media.

The results underscore the multidimensional nature of donation motivations. While entertainment, socialization, and informativeness (all rooted in UGT) were confirmed as influential antecedents of donation intention, it is the mediating role of PF that reveals a deeper, ethically charged dimension to donating behaviors. This suggests that users do not only donate to satisfy immediate needs for amusement, connection, or knowledge but also to express their agency and construct identities within the Twitch platform. Here, the Foucauldian lens adds critical nuance by conceptualizing donations as practices of freedom—acts of ethical self-formation in response to the structure of platform power.

The empirical confirmation of PF as a mediator between socialization and DI is particularly notable. Twitch, as a live streaming platform, is built upon interactivity and social immersion. This study confirms that such social dynamics are not merely peripheral; they constitute a central pathway through which viewers come to see themselves as participants with the power to support others in meaningful ways, despite what the status quo and existing hierarchy may dictate. Donations, in this view, are performative acts that symbolize community membership and personal alignment with streamers’ values and aesthetics and take on a political perspective, in so far as we live in polities or communities.

Furthermore, the significant direct effect of informativeness on DI suggests that viewers also derive cognitive value from stream content. This reflects a more pragmatic motivation: donations as a means of maintaining access to content that is educational or strategically beneficial. Nevertheless, this pathway appears less tied to practices of freedom, indicating that not all gratifications foster the same type of ethical engagement. Entertainment, although still significant, operates more ambiguously; it may support escapism or self-expression, depending on the context.

A second contribution of this study lies in its analysis of the hybrid nature of human motivation. PF, as conceptualized here, captures the transition from controlled, perhaps status-driven, behaviors to autonomous, value-aligned engagement. This dynamic suggests a maturation process in which the longer and deeper a user’s engagement with Twitch, the more their giving reflects internalized ethical commitments rather than external prompts.

As limitations, one should refer this study’s convenience sample, composed of Portuguese-speaking Twitch viewers, which compromises the generalizability of the results. Twitch’s global user base is heterogeneous, and cultural differences likely affect how motivations are understood [39]. Future research could explore cross-cultural comparisons, perhaps examining how donation behaviors differ in collectivist versus individualist societies, or in regions with stronger or weaker traditions of digital patronage. Furthermore, more or less meritocratic-oriented regimes (versus harmony-seeking ones where everyone seeks to be, or appears to be, the same, and preferring equal treatment despite obvious differences) may spur on other types of motivation other than PF, so comparative research in those societies may prove insightful, too.

Additionally, this study’s cross-sectional design provides a snapshot of motivations and behaviors but cannot fully capture their evolution over time. A longitudinal approach would offer deeper insights into how motivations change with prolonged platform involvement, streamer–viewer relationship development, or exposure to specific content genres.

Further, the operationalization of PF in a survey-based model, while novel and grounded in the theoretical literature, inevitably simplifies a complex philosophical concept. Qualitative methodologies, such as ethnography or in-depth interviews, could be employed to better understand the lived experience of freedom in Twitch participation.

Moreover, future research could expand the scope of motivational constructs beyond UGT and PF. Incorporating affective labor, fan identity, or platform gamification could enrich our understanding of donation behavior. The role of streamer strategies, such as callouts, thank-you rituals, or tiered reward systems, also merits closer scrutiny, as these may actively shape how users interpret the meaning of their contributions.

Summarizing, this study offers a comprehensive and original framework for understanding donation behaviors on Twitch. By combining the motivational clarity of UGT with the ethical depth of Foucauldian theory, it provides a multidimensional view of why viewers choose to financially support streamers, freely giving what is theirs. The findings challenge simplistic economic or transactional interpretations of donating and suggest that donations are instead expressions of freedom, acts of affiliation, and performances of the self. As live streaming continues to grow in influence, understanding the interplay between platform affordances, user motivations, and ethical subjectivity will be crucial for scholars, practitioners, and users alike.

This study challenges reductionist interpretations of viewer generosity in digital spaces. Where traditional UGT might classify a donation as social integrative need fulfillment, our Foucauldian lens exposes it as an act of resistance—a choice to redistribute resources within platform economies that often exploit creators. For researchers, this underscores the need to pair motivation theories with critical frameworks; for practitioners, it highlights how platform design (e.g., donation alerts) can amplify or constrain users’ sense of ethical agency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M., M.A.-Y.-O. and A.S.-B.; methodology, J.M., M.A.-Y.-O. and A.S.-B.; formal analysis, J.M., M.A.-Y.-O. and A.S.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M., M.A.-Y.-O. and A.S.-B.; writing—review and editing, J.M., M.A.-Y.-O. and A.S.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of ERBE—Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (CE12202401 on 2 December 2025). Research supported by GESCE-URJC, CIRSIT-URJC and GID-IIC TAC CEE-URJC.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sánchez-Bayón, A. Renovación del pensamiento económico-empresarial tras la globalización: Talentism & Happiness Economics. Bajo Palabra 2020, 24, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva-Estrada, J.M.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. Estudio bibliométrico de Economía Digital y sus tendencias. Rev. Estud. Empres. Segunda Época 2024, 1, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, D.; Hackenholt, A.; Zawadzki, P.; Wanner, B. Interactions of Twitch Users and Their Usage Behavior. In Social Computing and Social Media; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.R.; Woodcock, J. “And today’s top donator is”: How live streamers on Twitch. tv monetize and gamify their broadcasts. Soc. Media + Soc. 2019, 5, 2056305119881694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Xia, H.; Heo, S.; Wigdor, D. You watch, you give, and you engage: A study of live streaming practices in China. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Datareportal. Digital 2023: Brazil. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-brazil (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Research and Markets. Latin America Mobile Gaming-Market Share Analysis, Industry Trends & Statistics, Growth Forecasts (2025–2030). Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/latin-america-mobile-gaming-market#:~:text=Moreover%2C%20Latin%20American%20powerhouse%20Brazil,games%20fall%20under%20this%20category. (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- TwitchTracker. Twitch Statistics & Charts. Available online: https://twitchtracker.com/statistics (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Marktest. Jovens com Maior Afinidade com Discord e sem Afinidade com Facebook. Available online: https://www.marktest.com/wap/a/n/id~294d.aspx (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Marktest. Utilização de Plataformas de Streaming Atinge Novo Máximo em Portugal. Available online: https://www.marktest.com/wap/a/n/id~2b85.aspx (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Hamilton, W.A.; Garretson, O.; Kerne, A. Streaming on twitch: Fostering participatory communities of play within live mixed media. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; pp. 1315–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Jia, A.L. User donations in online social game streaming: The case of paid subscription in twitch. tv. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference 2022, Lyon, France, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 215–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Fink, E.L.; Cai, D.A. Loneliness, gender, and parasocial interaction: A uses and gratifications approach. Commun. Q. 2008, 56, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöblom, M.; Törhönen, M.; Hamari, J.; Macey, J. The ingredients of Twitch streaming: Affordances of game streams. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 92, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partin, W.C. Bit by (Twitch) Bit: “Platform Capture” and the Evolution of Digital Platforms. Soc. Media + Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120933981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, D.; Wanner, B.; Hackenholt, A.; Zawadzki, P.; Knautz, K. World of Streaming. Motivation and Gratification on Twitch. In Proceedings of the Social Computing and Social Media. Human Behavior: 9th International Conference, SCSM 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–14 July 2017; pp. 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Lin, J.C.-C.; Miao, Y.-F. Why are people loyal to live stream channels? The perspectives of uses and gratifications and media richness theories. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohn, D.Y.; Jough, P.; Eskander, P.; Siri, J.S.; Shimobayashi, M.; Desai, P. Understanding digital patronage: Why do people subscribe to streamers on twitch? In Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-human Interaction in Play, Barcelona, Spain, 22–25 October 2019; pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G.; Gurevitch, M. Uses and gratifications research. Public Opin. Q. 1973, 37, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.R.; Carrigan, M.; Brock, T. The imperative to be seen: The moral economy of celebrity video game streaming on Twitch. tv. First Monday 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoganathan, V.; Osburg, V.-S.; Stevens, C.J. Freedom and giving in game streams: A Foucauldian exploration of tips and donations on Twitch. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.J.; Johnson, M.R. Frictions and flows in Twitch’s platform economy: Viewer spending, platform features and user behaviours. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2024, 27, 1924–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, L. How attachment influences users’ willingness to donate to content creators in social media: A socio-technical systems perspective. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bründl, S.; Matt, C.; Hess, T. Consumer use of social live streaming services: The influence of co-experience and effectance on enjoyment. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Guimarães, Portugal, 5–10 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Cuadrado, F.; Tyson, G.; Uhlig, S. Behind the game: Exploring the twitch streaming platform. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Network and Systems Support for Games (NetGames), Zagreb, Croatia, 3–4 December 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dux, J.; Kim, J. Social live-streaming: Twitch. TV and uses and gratification theory social network analysis. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2018, 47, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöblom, M.; Hamari, J. Why do people watch others play video games? An empirical study on the motivations of Twitch users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.L.; Turner, L.H.; Zhao, G. Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wulf, T.; Schneider, F.M.; Beckert, S. Watching Players: An Exploration of Media Enjoyment on Twitch. Games Cult. 2020, 15, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, E. To watch or to play, it is in the game: The game culture on Twitch. tv among performers, plays and audiences. J. Gaming Virtual Worlds 2016, 8, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magano, J.; Leite, Â. The motivation Scale for Sport consumption: Turkish and Spanish versions’ psychometric properties. Manag. Sport Leis. 2022, 29, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, G. The Sociology of Sociability. Am. J. Sociol. 1949, 55, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunigita, H.; Javed, A.; Kohda, Y. Solicited PWYW donations on social live streaming services through reciprocal actions between streamers and viewers. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2023, 12, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, M. Digital governmentality: Toxicity in gaming streams. In Games and Ethics: Theoretical and Empirical Approaches to Ethical Questions in Digital Game Cultures; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilvert-Bruce, Z.; Neill, J.T.; Sjöblom, M.; Hamari, J. Social motivations of live-streaming viewer engagement on Twitch. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. The ethics of care for the self as a practice of freedom: An interview with Michel Foucault on January 20, 1984. In The Final Foucault; Bernauer, J., Rasmussen, D., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T. The freedom of binge gaming or technologies of the self? Chinese enjoying the game Werewolf in an era of hard work. Chin. J. Commun. 2021, 14, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowert, R.; Griffiths, M.D.; Oldmeadow, J.A. Geek or Chic? Emerging Stereotypes of Online Gamers. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2012, 32, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laconi, S.; Pirès, S.; Chabrol, H. Internet gaming disorder, motives, game genres and psychopathology. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, P.R.; Melancon, J. Gender and live-streaming: Source credibility and motivation. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, D. Assessing the use of back translation: The shortcomings of back translation as a quality testing method. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B.; Eva, N.; Zarea Fazlelahi, F.; Newman, A.; Lee, A.; Obschonka, M. Addressing common method variance and endogeneity in vocational behavior research: A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 121, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M.; Jensen, R. Common Method Bias in Public Management Studies. Int. Public Manag. J. 2015, 18, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polas, M.R.H. Common Method Bias in Social and Behavioral Research: Strategic Solutions for Quantitative Research in the Doctoral Research. J. Compr. Bus. Adm. Res. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.; Wende, S.; Becker, J. SmartPLS. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Krey, N. Covariance-based structural equation modeling in the Journal of Advertising: Review and recommendations. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: Noida, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Población, J. Assessing the efficacy of borrower-based macroprudential policy using an integrated micro-macro model for European households. Econ. Model. 2017, 61, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Steyaert, C. Rethinking the Space of Ethics in Social Entrepreneurship: Power, Subjectivity, and Practices of Freedom. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksala, J. Foucault on Freedom; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, N. Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J.; Keronen, L. Why do people play games? A meta-analysis. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Why do audiences choose to keep watching on live video streaming platforms? An explanation of dual identification framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Extended self in a digital world. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skandalis, A.; Byrom, J.; Banister, E. Paradox, tribalism, and the transitional consumption experience. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 1308–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).