Knowledge Management Strategies Supported by ICT for the Improvement of Teaching Practice: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Open Educational Practices

- These practices encourage joint work among teachers, students, and researchers, facilitating the exchange of ideas and resources. Through open platforms and learning management systems [17], educators can share experiences, strategies, and knowledge that enrich the teaching–learning process and improve knowledge management in the classroom [18].

- Open educational practices promote access to educational resources, materials, and methodologies that can be shared between teachers and students. This allows for more efficient knowledge management, as educators can reuse and adapt materials designed to foster meaningful learning.

- Open educational practices provide greater flexibility in teaching, allowing content and methods to be tailored to the specific needs of students. This results in knowledge management that adapts to diverse contexts and realities, promoting more inclusive education [19].

- By promoting an environment where ideas are shared and new methodologies are tested, open educational practices drive innovation in teaching. This contributes to knowledge management that enables not only the transmission of information but also the creation and application of new pedagogical approaches.

2.2. Information and Communication Technologies in Education

2.2.1. Learning Management Systems (LMS)

2.2.2. Multimedia Resources

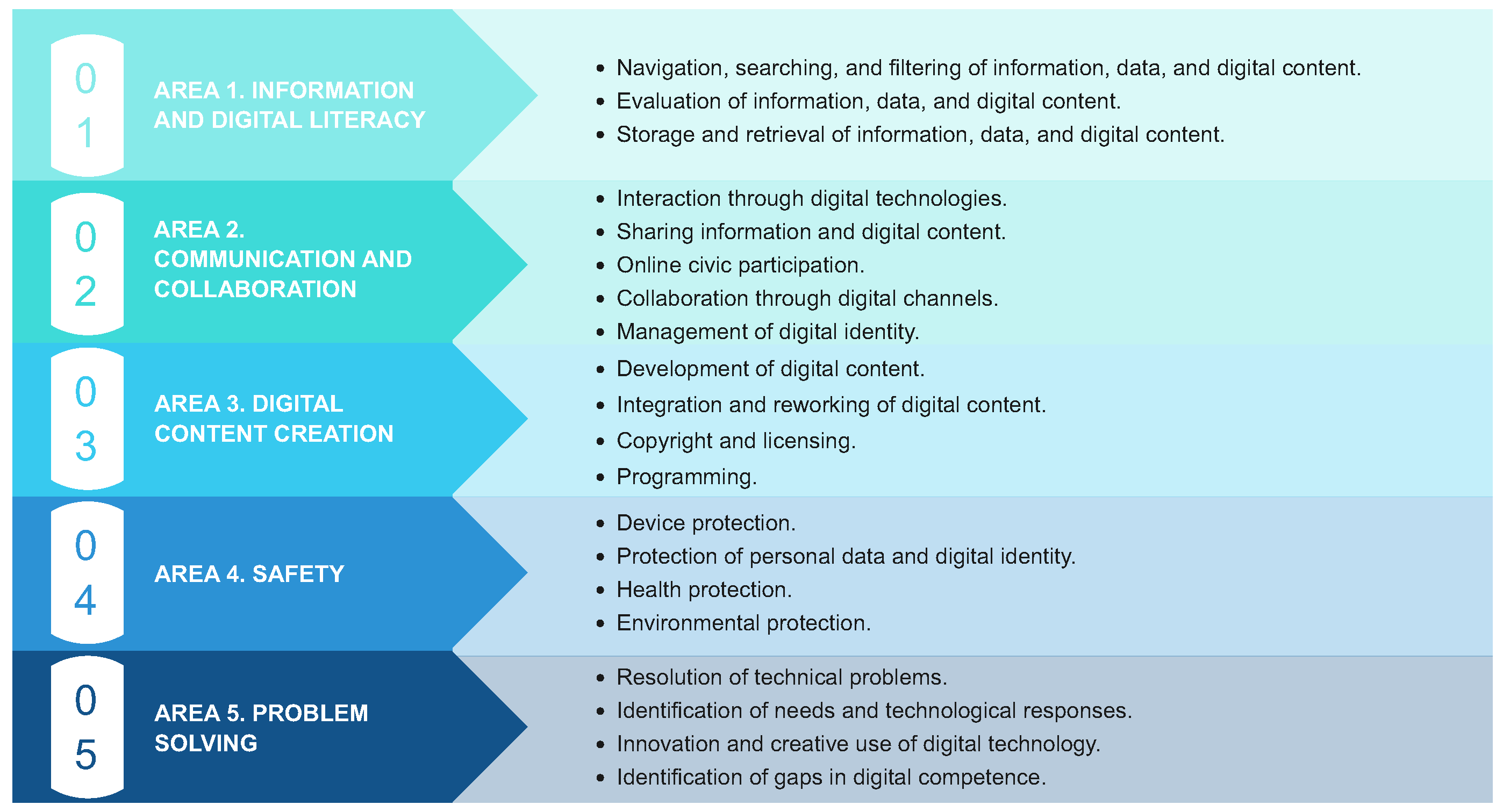

2.2.3. Digital Competencies

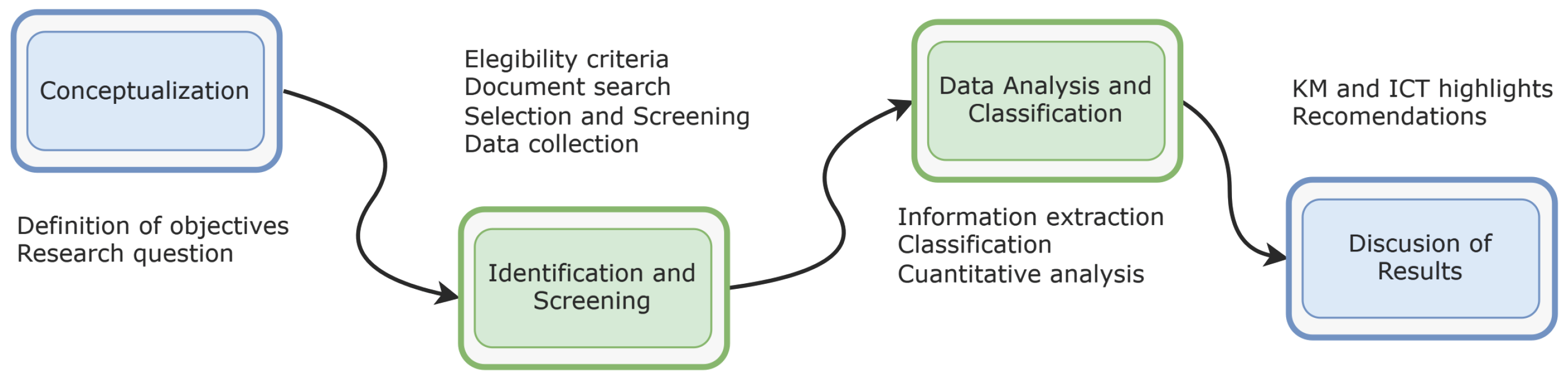

3. Methodology

3.1. Eligibility Criteria

3.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Focus on KM in higher education (theoretical frameworks or practical implementations).

- Documentation of ICT applications in higher education (e.g., digital platforms, collaborative tools, or technology-enhanced pedagogical strategies).

- Explicit discussion of the knowledge generation/sharing practices of educators using ICT.

- Publications in Spanish or English to ensure accessibility and comprehension of the analyzed literature.

- Publication dates between 2019 and March, 2025, to align with recent advancements in KM and ICT.

3.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Documents in languages other than Spanish or English could not be analyzed within the framework of this review.

- Research using knowledge management methodologies not applied to teaching–learning processes, such as studies focused on corporate or industrial settings.

- Studies not directly related to knowledge management or ICT, even if they addressed higher education.

- Publications prior to 2019, to avoid including outdated information that is not aligned with recent technological advances.

3.2. Document Search

- (i)

- Publications had to be from 2019 onward.

- (ii)

- Titles and abstracts had to include the following keywords:

- “Gestión del conocimiento”, “Educación superior”, and “Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación” (for Spanish Querys)

- “Knowledge management”, “Higher education”, and “Information and Communication Technologies” (for English Querys)

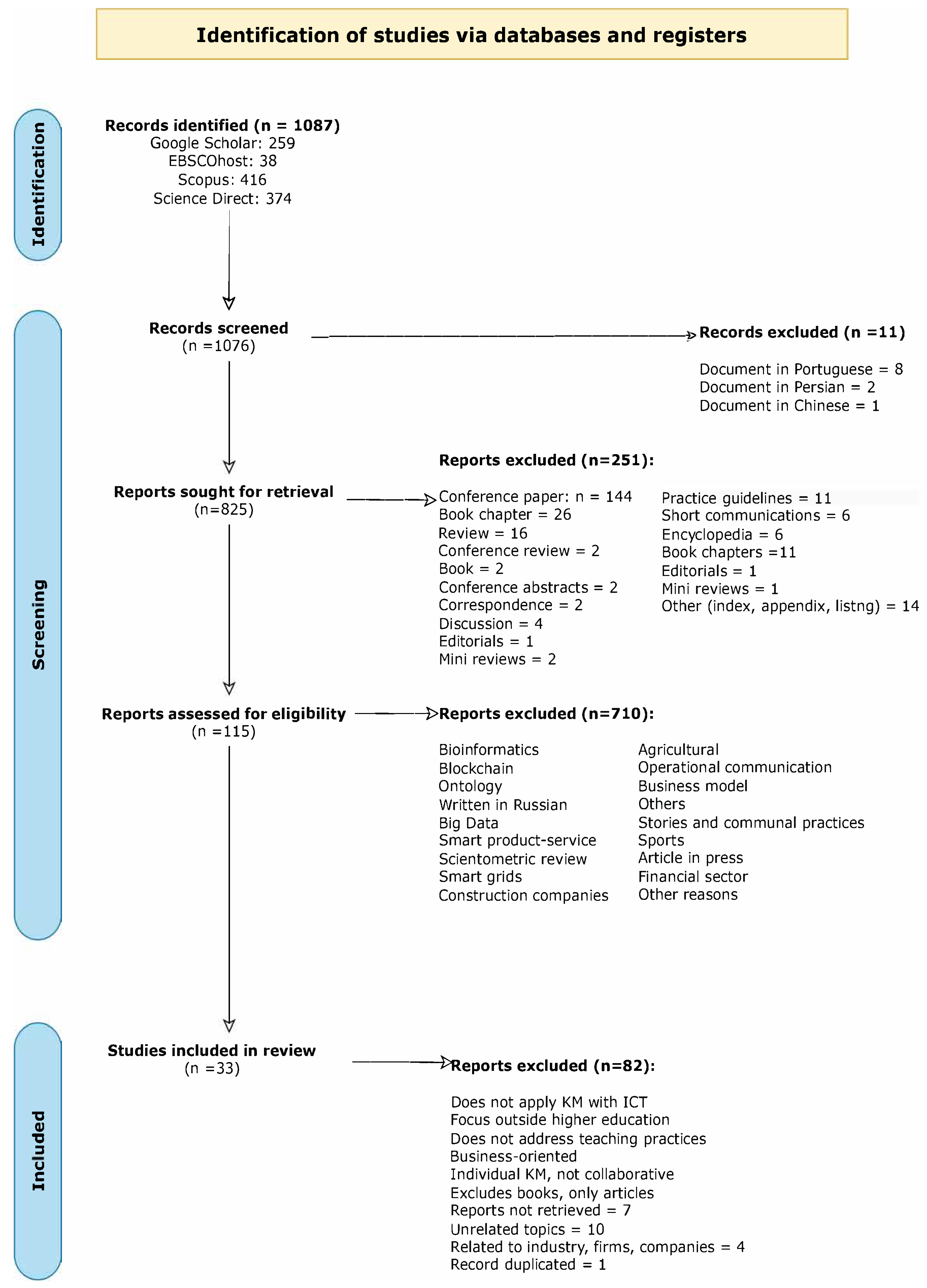

3.3. Selection Process

- Identification: After applying these criteria, a total of 1087 documents were retrieved, distributed as 259 from Google Scholar, 38 from EBSCOhost, 416 from Scopus, and 374 from ScienceDirect.

- Screening: At this stage, the 1087 articles were screened and selected based on the eligibility criteria described in Section 3.1. Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, mainly due to being in a language other than Spanish or English, the type of document, accessibility or availability issues, lack of thematic relevance, not directly addressing the relationship between ICT and knowledge management in higher education, or lacking relevant empirical evidence. Other systematic reviews were explored and analyzed, with the findings presented in Section 4.3.

- Included: Finally, after a detailed analysis, 33 articles were considered in systematic review.

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

- Yes: Fully meets the criterion, providing maximum confidence (100% of the criterion’s weight).

- No: Does not meet the criterion, negatively affecting the reliability of the review (0% of the criterion’s weight).

- Can not answer: Lack of information, generating uncertainty about the quality of the review. A partial penalty of 50% of the weight of the criterion is assigned.

- Not applicable: The criterion is not relevant to the specific review and does not influence the score.

- Construct the comparison matrix according to the following criteria: Equal importance—1; Moderate importance—3; Strong importance—5; Very strong importance—7; Extreme importance—9; Intermediate values—2, 4, 6, and 8.Each comparison is entered into a square matrix , where n is the number of criteria if is the importance of criterion i over criterion j as Equation (1).

- Normalize the matrix and calculate the weights of the criteria:

- Calculate the Consistency Ratio (CR) as in Equation (7) for n criteria.where is the Saaty Random Index. The acceptance criterion is the following:

- If , the comparison matrix is consistent.

- If , the values should be revised.

- Multiply the weights of the criteria by the weights of the alternatives and select the review with the highest score.

- Low confidence: scores below the 33rd percentile.

- Moderate confidence: scores between the 33rd and 66th percentiles.

- High confidence: scores above the 66th percentile.

4. Results

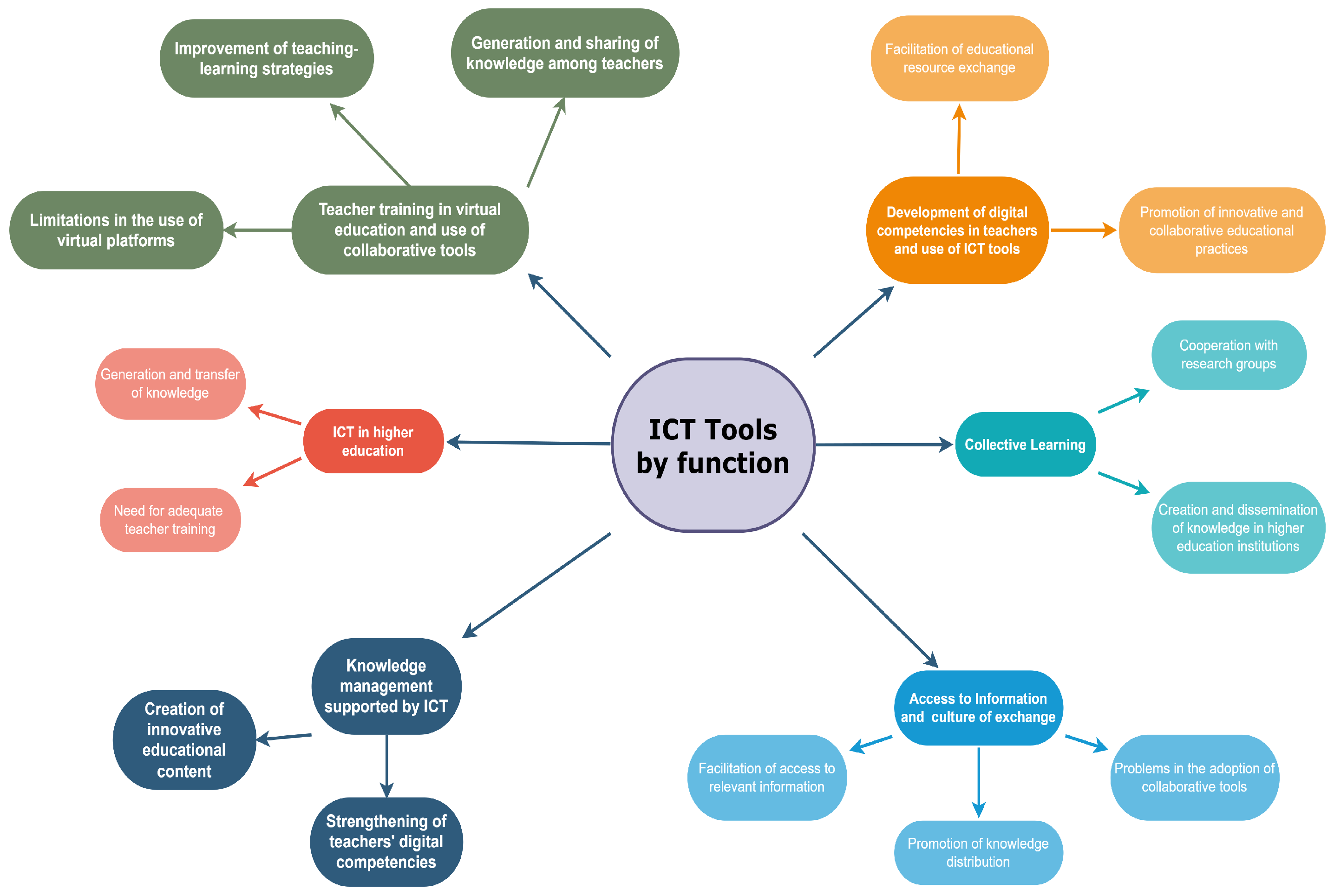

4.1. Impact of KM on Teaching Practices

- ICT facilitates the creation of spaces where teachers can interact and collaborate, sharing their teaching practices. This includes digital platforms and educational social networks that promote the exchange of ideas and resources among peers.

- The use of ICT in KM strategies supports continuous learning and professional development for teachers. This allows them to update and enrich their teaching practices by accessing digital educational resources and participating in virtual communities of practice.

- ICT facilitates reflection on pedagogical practices by providing tools to gather evidence and analyze results. This enables teachers to assess the effectiveness of their teaching methods and adjust them as needed.

- Teachers can collaborate beyond their immediate environment, extending their influence by sharing practices and experiences at both local and international levels, using ICT to connect with colleagues and education experts.

- Competency transfer focuses on sharing specific technical skills and knowledge, directly impacting the improvement of supplier productivity and competitiveness.

- Mentoring mechanisms establish a direct link between experts and suppliers, facilitating the transmission of explicit knowledge (documented and easily communicated) and tacit knowledge (based on experience and intuition).

- Knowledge-sharing strategies are adapted to diverse cultural contexts, considering factors such as power distance and uncertainty avoidance.

- The use of ICT streamlines the flow of knowledge by integrating tools that eliminate geographic and temporal barriers, employing user-friendly technological solutions aimed at simplifying information-sharing processes. Similarly, systems that remove time and space constraints enable continuous real-time communication between companies and suppliers, thus fostering collaborative work. Likewise, digital platforms that allow for the sharing of documents, resources, and knowledge encourage transparency and accessibility of the information necessary for innovation.

- The development of digital competencies among teachers, such as the ability to search, evaluate, and use online information, as well as to collaborate and communicate effectively through digital tools, facilitates collaboration between them.

- The article mentions ICT tools like forums, chats, wikis, emails, videoconferences, etc., which teachers can use to collaborate and share resources and information, even remotely.

- The need to shift from traditional educational practices to a more collaborative approach is mentioned, where teachers work together to design and implement new teaching and learning strategies.

- The importance of teacher training in digital competencies is emphasized to foster collaboration among education professionals and enhance educational activities.

- Trust: Ensures that members feel confident sharing their ideas and experiences.

- Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Encourages cooperation and the contribution of valuable information.

- Social interaction: Facilitates communication and mutual understanding, reinforcing team spirit.

4.2. ICT Tools for Knowledge Sharing

4.3. Systematic Reviews Comparison

5. Discussion

- Institutional: the presence of clear policies, incentives for collaboration, and flexible organizational structures;

- Economic: the availability of resources for digital infrastructure, faculty training, and technical support;

- Cultural: the willingness of faculty to share knowledge and engage in communities of practice;

- Individual: motivation, digital competence, and openness to technological change.

5.1. Research Limitations and Biases

5.2. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| AMSTAR | Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews |

| HEIs | Higher Education Institutions |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| KM | Knowledge Management |

| LMS | Learning Management Systems |

References

- Mendoza-Suárez, C.; Bullón Romero, C. Gestión del conocimiento en instituciones de educación superior: Una revisión sistemática. Horizontes Rev. Investig. Cienc. Educ. 2022, 6, 1992–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, B.A.; Chiappe, A.; Segovia, Y. Knowledge management and information and communication technologies: Some lessons learned for education. Rev. ESPACIOS 2020, 41, 118–134. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Delgado, V.M. El proceso de enseñanza aprendizaje mediado por la virtualización en el bachillerato técnico de la unidad educativa fiscal “cultura machalilla”. Ycs 2021, 5, 8–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Informe de Seguimiento de la Educación en el Mundo 2023: Tecnología en la Educación: ¿una Herramienta en los Términos de Quién? Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura, París. 2023. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000388894 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Darling-Hammond, L. Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 40, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamrudi, Z.; Setiawan, M.; Irawanto, D.W.; Rahayu, M. Incorporating counterproductive knowledge behaviour in the higher education context: Proposing the potential remedies in explaining the faculty members’ performance. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2023, 74, 630–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Calzada, M. La Gestión Del Conocimiento Dinámico en Entornos Colaborativos Para Generar Ventajas Competitivas Sostenibles en IES. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, Santiago de Querétaro, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Correa, Y.; Aristizábal-Botero, C.A.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Bran-Piedrahita, L. Formulación de modelos de gestión del conocimiento aplicados al contexto de instituciones de educación superior. Inf. Tecnol. 2020, 31, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Flórez, D.; Rincón-Ramírez, A.V.; Medina-Moreno, L.R. Competencias digitales de los docentes en la Universidad de los Llanos, Colombia. Trilogia Cienc. Tecnol. Soc. 2022, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDUCAUSE. 2023 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: Teaching and Learning Edition. EDUCAUSE, pp. 1–55, May 2023. Available online: https://library.educause.edu/resources/2023/5/2023-educause-horizon-report-teaching-and-learning-edition (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Álvarez Loyola, C.; Córdova Esparza, D. Los NOOC para el desarrollo de competencias digitales y formación virtual: Una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Edutec Rev. Electron. Tecnol. Educ. 2023, 3, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flŕez, C.M.C.; Fernández, A.O.L. Comunidades de práctica como plataformas de mejoramiento educativo. Sophia 2021, 17, 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, P.C.L.; Antolinez, S.V.; Trujillo, M.A.V.; Arias, M.A.L. Estrategias e instrumentos de la gestión del conocimiento para dinamizar comunidades de práctica en el contexto de la educación superior. Fondo Editor. Univ. Servando Garcés 2022, 17, 122–143. [Google Scholar]

- Finocchiaro, F. Organización que aprende: Nociones, condicionantes e importancia en la actualidad. Cent. Estud. Adm. 2022, 6, 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, A. Conectivismo y diseño instruccional: Ecología de aprendizaje para la universidad del siglo XXI en México. Márgenes Rev. Educ. Univ. Málaga 2021, 2, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, A. Prácticas educativas abiertas como factor de innovación educativa. Boletín Redipe 2012, 818, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, D.; Chugh, R.; Luck, J. Learning management systems, an overview. In Encyclopedia of Education and Information Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1052–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, N.; Durst, S.; Hariharasudan, A.; Shamugia, Z. Knowledge management practices in higher education institutions—A comparative study. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 22, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz-Sánchez, P.; Frutos, A.E.; García, S.A.; de Haro Rodríguez, R. Formación del profesorado para la construcción de aulas abiertas a la inclusión. Rev. Educ. 2021, 393, 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla, L.; Cañola, L.M.; Núñez-Palomar, K. Las TIC como Herramienta Didáctica para mejorar el proceso de Enseñanza Aprendizaje. Una revisión de la literatura. Rev. RedCA 2024, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, J.Q.; Carbonel, G.; Picho, D. Sistemas de gestión de aprendizaje (LMS) en la educación virtual. Revencyt 2021, 50, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kraleva, R.; Sabani, M.; Kralev, V. An analysis of some learning management systems. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, P.C.; Quintero, I.R. YouTube y aprendizaje: Una revisión bibliográfica sistemática. Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calidad Efic. Cambio Educ. (REICE) 2022, 21, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Toapanta, M.E.N.; Ruiz, F.J.M.; Reyes, C.E.G.; Aguirre, J.O.R. Khan Academy y su incidencia en las habilidades de resolución de problemas matemáticos. Dominio Cienc. 2024, 10, 821–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpízar Vargas, M.; Paez Paez, C.; Córdoba Hernández, J. Uso de khan academy en un curso universitario de cálculo diferencial e integral. Univ. Los Lagos RIME 2024, 1, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L.; Moorhouse, B. Facilitating Synchronous Online Language Learning through Zoom. RELC J. 2022, 53, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.; Samadder, S.; Srivastava, A.; Meena, R.; Ranjan, P. Review of online teaching platforms in the current period of COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J. Surg. 2022, 84, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas La Torre, E.R.; Cruz Cisneros, V.F.; Quiroz Vargas, J.L.; Del Valle Valles Urdániga, V.; Casusol Moreno, F.E.M. Mejoramiento del trabajo colaborativo online aplicando programa drive. Conrado 2022, 18, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M. El papel de las tic y las estrategias instruccionales que favorecen aprendizajes permanentes y significativos. Entornos Aprendiz. 2022, 2, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt, J. Social media in second and foreign language teaching and learning: Blogs, wikis, and social networking. Lang. Teach. 2019, 52, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresno Chávez, C.; Consuegra Llapur, M.D. Características de las Redes Académicas. Estado del arte. Rev. Cuba. Inform. Medica 2020, 12, 132–150. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado-Borja, W.E.; Barrera-Navarro, J.R.; Ravelo-Méndez, R.E. El gestor bibliográfico digital colaborativo como herramienta de apoyo al proceso de investigación. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Super. 2022, 13, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenara, J.C.; Rodríguez, A.P. Marco Europeo de Competencia Digital Docente. EDMETIC 2020, 9, 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Zavala, D.; Muñoz, K.; Lozano, E. Un enfoque de las competencias digitales de los docentes. Rev. Publicando 2016, 3, 330–340. [Google Scholar]

- Centeno-Caamal, R. Formación tecnológica y competencias digitales docentes. Rev. Docentes 2.0 2021, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova Esparza, D.M.; Romero González, J.A.; López Martínez, R.E.; García Ramírez, M.T.; Sánchez Hernández, D.C. Desarrollo de competencias digitales docentes mediante entornos virtuales: Una revisión sistemática. Apertura Rev. Innov. Educ. 2024, 16, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, S.M.B. Marco Común de Competencia Digital Docente. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2018, 21, 369–370. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Escobedo, J.; Ayala-Jiménez, G.; Mora-García, O.L.G.A.; Ruezga-Gómez, A.E. Competencias digitales docentes en educación superior: Caso Centro Universitario de Los Altos. Rev. Educ. Desarro. 2019, 51, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, B.J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Wells, G.A.; Boers, M.; Andersson, N.; Hamel, C.; Porter, A.C.; Tugwell, P.; Moher, D.; Bouter, L.M. Development of AMSTAR: A measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, C.R.C. Investigación de las competencias digitales y uso de tecnologías en la práctica del profesor universitario. In Investigación e Innovación en la Enseñanza Superior: Nuevos Contextos, Nuevas Ideas, 1st ed.; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; pp. 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Hernández, A.; Gámiz-Sánchez, V.; Maria Asunción, L. Niveles de desarrollo de la Competencia Digital Docente: Una mirada a marcos recientes del ámbito internacional. Innoeduca Int. J. Technol. Educ. Innov. 2019, 5, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D. Las TIC en la didáctica para la gestión del conocimiento, desde la perspectiva del docente universitario. Univ. Nac. Exp. Politec. Fuerza Armada Venez. 2019, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, C.G.; La Serna, P.N. Modelo de Gestión Tecnológica del Conocimiento para el proceso de mejora de la generación del conocimiento en unidades de información. Encontros Bibli Rev. Eletronica Bibliotecon. E Cienc. Inf. 2022, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, S.A.; Ledesma, F.E. Explorando la actitud docente en el e-learning: Un enfoque cualitativo desde la perspectiva de docentes y estudiantes. Edutec 2023, 84, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Córdoba, G.I. Gestión de la educación virtual en las universidades públicas Colombianas: El caso de la Universidad del Valle. Rev. Iber. Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2023, 7, 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Y.O.; Fernández, L.A.V.; Suarez, E.G.; Villegas, D.A.; Gamboa, J.N.; Echevarria, T.I.L. Gestión del conocimiento y tecnologías de la información y comunicación (TICs) en estudiantes de ingeniería mecánica. Apunt. Univ. 2020, 10, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, V.D.F.; Garcia, C.E.Z.; Oltra, G.E.Y.; Carrasquero, J.V. Tecnologías de información y comunicación en gestión del conocimiento en instituciones de educación superior de América Latina. Cienc. Inf. 2022, 51, 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- César Vázquez-González, G.; Ulianov Jiménez-Macías, I.; Juárez Hernández, L.G. Classification of Knowledge Management Strategies in order to enhance educational innovation in Higher Education Institutions. GECONTEC Rev. Int. Gestión Del Conoc. Tecnol. 2022, 10, 18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, J.H.E.; Zuluaga-Ortiz, R.A.; Barrios-Miranda, D.A.; Delahoz-Dominguez, E.J. Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in the processes of distribution and use of knowledge in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 198, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, J.H.E.; Zuluaga-Ortiz, R.A.; Donado, L.E.G.; Delahoz-Dominguez, E.J.; Marquez-Castillo, A.; Suarez-Sánchez, M. Cluster analysis in Higher Education Institutions’ knowledge identification and production processes. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 203, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhisn, Z.; Ahmad, M.; Omar, M.; Muhisn, S. The impact of socialization on collaborative learning method in e-Learning Management System (eLMS). Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2019, 14, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Bravo, J.; Zakari, O.A.; Baoua, I.; Pittendrigh, B.R. Facilitated discussions increase learning gains from dialectically localized animated educational videos in Niger. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2019, 25, 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávideková, M.; Greguš, M.; Zanker, M.; Bureš, V. Knowledge Management-Enabling Technologies: A Supplementary Classification. Acta Inform. Pragensia 2020, 9, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Torres, M.; Cárdenas Zea, M.P.; Morales Tamayo, Y.; Bárzaga Quesada, J.; Campos Rivero, D.S. Las tecnologías de la información y comunicación en la gestión del conocimiento. Univ. y Soc. 2021, 13, 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Horban, O.; Babenko, L.; Lomachinska, I.; Hura, O.; Martych, R. A knowledge management culture in the European higher education system. Nauk. Visnyk Natsionalnoho Hirnychoho Universytetu 2021, 1, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inrawan, W.I.; Tahir Supplier, N. Development Program Through Knowledge Sharing Effectiveness: A Mentorship Approach. Nauk. Visnyk Natsionalnoho Hirnychoho Universytetu 2021, 9, 13464–13475. [Google Scholar]

- Larios, F.M. Tecnologías Educativas en las Competencias Digitales de los Docentes en el Distrito de Sartimbamba. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Cesar Vallejo, Repositorio Digital Institucional, Trujillo Perú, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, K.; Janjua, U.I.; Alharthi, S.Z.; Madni, T.M.; Akhunzada, A. An Empirical Study to Investigate the Impact of Factors Influencing Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Teams. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 92715–92734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, K.P. The Association of Knowledge Management and Academic Performance in Academia. Electron. J. Knowl. Mangement 2023, 21, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, S.S.; Evangelista, E.; Marir, F. Towards Designing a Knowledge Sharing System for Higher Learning Institutions in the UAE Based on the Social Feature Framework. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Montes, J.K.; Mendoza-Zambrano, M.G. Revisión sistemática: Tecnologías educativas emergentes en la formación docente de la sociedad del conocimiento en el contexto latinoamericano. MQRInvestigar 2023, 7, 2527–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Porras, C.; Morales-Ortega, Y. Competencias de desempeño mediadas por las TIC para el fortalecimiento de la calidad educativa. Una revisión sistemática. Cult. Educ. Soc. 2019, 10, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, J.A.D.; Castro, M.L.C.; Vivas, R.V.J.; Rueda, A.C.C. Collaborative learning tools used in virtual higher education programs: A sistematic review of literature in Iberoamerica. In Proceedings of the 2020 15th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Seville, Spain, 24–27 June 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Campa Rubio, L.E.; Lozano Rodríguez, A. Competencias Digitales Docentes y su integración con las herramientas de Google Workspace: Una revisión de la literatura. Transdigital 2023, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas Monzonís, N.; Gabarda Méndez, C.; Rodríguez Martín, A.; Cívico Ariza, A. Tecnología y educación superior en tiempos de pandemia: Revisión de la literatura. Hachetetepé 2022, 24, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basilotta-Gómez-Pablos, V.; Matarranz, M.; Casado-Aranda, L.A.; Otto, A. Teachers’ digital competencies in higher education: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High Educ. 2022, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L.M.; JAsso, F.J.P. Una revisión dedicada a las características y desafíos de un espacio físico transformado en ambiente para el aprendizaje. Inf. Cult. Soc. 2019, 41, 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Solano Hernández, E.; Marín Juarros, V.I.; Rocha Vásquez, A.R. Competencia digital docente de profesores universitarios en el contexto iberoamericano. Una revisión. Tesis Psicol 2022, 17, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikuni, A.C.; Dwivedi, R.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Strategic knowledge, IT capabilities and innovation ambidexterity: Role of business process performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 124, 915–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikuni, A.C.; Dwivedi, R.; dos Santos, M.Q.L.; Fragoso, R.; de Souza, A.C.; de Sousa, F.H.; dos Santos, W.A.P.; Romboli, D.S. Effects of knowledge management processes by strategic management accounting on organizational ambidexterity: Mediation of operational processes under environmental dynamism. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2024, 25, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Databases | Spanish Query | English Query |

|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar | (“Gestión del conocimiento” AND “educación superior” AND “Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación”):ab,ti | (“Knowledge management” AND “higher education” AND “Information and Communication Technologies”):ab,ti |

| EBSCOhost | Gestión del conocimiento Y educación superior Y Tecnologías de la información y la comunicación | Knowledge management AND higher education AND Information and Communication Technologies |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Gestión del conocimiento” y “tecnologías de la información y la comunicación”) | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Knowledge management” AND “information and communication technologies”) |

| ScienceDirect | Gestión del conocimiento AND educación superior AND Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación | “Knowledge management” AND “higher education” AND “Information and Communication Technologies” |

| Database | Found Literature | Included Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar | 259 | 7 |

| EBSCOhost | 38 | 5 |

| Scopus | 416 | 10 |

| Science Direct | 374 | 2 |

| Total | 1087 | 33 |

| Criteria | Item | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive search methods | Q2 | Refers to search methods to avoid bias or exclusion of relevant evidence. |

| Duplicate selection and data extraction | Q3 and Q4 | Related to the risks of making errors or introducing bias in the selection or extraction of data. |

| Risk of bias assessment in primary studies | Q7 | Concerns bias in the assessment of studies. |

| Appropriate statistical methods | Q8 | Refers to methods for synthesizing evidence and avoiding errors in data interpretation. |

| Assessment of heterogeneity | Q9 | Relates to analyzing significantly different studies to interpret the results correctly. |

| Assessment of publication bias | Q10 | Considers the presence of publication bias. |

| Criteria | Item | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol design before the review | Q1 | Refers to reducing the risk of modifying review methods at convenience. |

| List of included and excluded studies | Q5 | Related to the transparency of included and excluded studies. |

| Characteristics of included studies | Q6 | Refers to interpreting the results. |

| Declaration of conflicts of interest | Q11 | Ensures transparency in research. |

| Database | Publication Year | Authors | Research Title |

|---|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar | 2019 | Contreras-Cázarez. [40] | Investigación de las competencias digitales y uso de tecnologías en la práctica del profesor universitario. |

| 2019 | Padilla-Hernández et al. [41] | Niveles de desarrollo de la competencia digital docente: una mirada a marcos recientes del ámbito internacional. | |

| 2019 | Silva [42] | Las TIC en la didáctica para la gestión del conocimiento, desde la perspectiva del docente universitario. | |

| 2021 | Calderón-Delgado et al. [3] | El proceso de enseñanza aprendizaje mediado por la virtualización en el bachillerato técnico de la unidad educativa fiscal “Cultura Machalilla”. | |

| 2022 | Montoya y La Serne [43] | Modelo de gestión tecnológica del conocimiento para el proceso de mejora de la generación del conocimiento en unidades de información. | |

| 2023 | Rodríguez-Paredes y Ledesma Pérez [44] | Explorando la actitud docente en el e-learning: Un enfoque cualitativo desde la perspectiva de docentes y estudiantes. | |

| 2023 | Toro-Córdova [45] | Gestión de la educación virtual en las universidades públicas colombianas: el caso de la Universidad del Valle. | |

| EBSCO host | 2020 | Barboza et al. [2] | Knowledge management and information and communication technologies: Some lessons learned for education. |

| 2020 | Ocaña-Fernández et al. [46] | Gestión del conocimiento y tecnologías de la información y comunicación (TICs) en estudiantes de ingeniería mecánica. | |

| 2021 | Torres-Flórez [9] | Competencias digitales de los docentes en la Universidad de los Llanos, Colombia. | |

| 2022 | De Freitas-Fernández et al. [47] | Tecnologías de información y comunicación en gestión del conocimiento en instituciones de educación superior de América Latina. | |

| 2022 | Vázquez-González, et al. [48] | Classification of Knowledge Management Strategies in order to enhance educational innovation in Higher Education Institutions. | |

| Science Direct | 2022 | Escorcia et al. [49] | Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in the higher education institutions (HEIs). |

| 2022 | Escorcia et al. [50] | Cluster análisis in higher education institutions knowledge identification and production processes. | |

| SCOPUS | 2019 | Muhisn et al. [51] | The Impact of Socialization on Collaborative Learning Method in e-Learning Management System (eLMS). |

| 2019 | Bello-Bravo et al. [52] | Facilitated discussions increase learning gains from dialectically localized animated educational videos in Niger. | |

| 2020 | Dávideková, et al. [53] | Knowledge Management-Enabling Technologies: A Supplementary Classification. | |

| 2021 | Morales, et al. [54] | Las tecnologías de la información y comunicación en la gestión del conocimiento. | |

| 2021 | Horban, et al. [55] | A knowledge management culture in the European higher education system. | |

| 2021 | Inrawan & Tahir [56] | Supplier Development Program Through Knowledge Sharing Effectiveness: A Mentorship Approach. | |

| 2022 | Larios [57] | Tecnologías educativas en las competencias digitales de los docentes en el distrito de Sartimbamba. | |

| 2023 | Saeed et al. [58] | An Empirical Study to Investigate the Impact of Factors Influencing Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Teams. | |

| 2023 | Paudel [59] | The Association of Knowledge Management and Academic Performance in Academia. | |

| 2023 | Syed et al. [60] | Towards Designing a Knowledge Sharing System for Higher Learning Institutions in the UAE Based on the Social Feature Framework. |

| Research | Benefits | Limitations | ICT Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barboza and Segobia [2] | - Improve the transfer, storage, and application of knowledge. - Foster collaboration among teachers. | - Lack of knowledge about the integration of ICT in the pedagogical field. | - LMS platforms, mobile devices, collaborative networks. |

| Bello-Bravo et al. [52] | - Increased learning through localized animated videos and inclusivity for people with low literacy levels. - Ease of sharing knowledge through mobile phones, enabling the dissemination of information without the need for costly infrastructure. - The combination of animations with facilitated discussions strengthened learning and encouraged the replication of knowledge among participants. | - Dependence on technology in communities with limited access to devices or electricity. - Possible language barriers where some concepts may be misunderstood if there is inadequate supervision in translation or unfamiliar terms are used. - Differences in access to and use of technology between men and women were identified. | - Educational animated videos, mobile phones and laptops, knowledge tests, SPSS and SAS analysis tools. |

| Calderón-Delgado et al. [3] | - Promotion of effective collaboration. - Socialization of experiences. - Intellectual production in educational environments. | - | - Virtual platforms that enable synchronous and asynchronous communication. |

| Contreras-Cázarez [40] | - Improve information search and data processing. | - Low involvement of teachers. | - Web search engines, educational resources, content creation software. |

| Dávideková, et al. [53] | - Facilitation of access to information by sharing knowledge, eliminating temporal and spatial barriers. - Use of databases, data mining, and expert systems to make decisions based on structured information. - Adaptability to systems such as e-learning and collaborative platforms allows learning according to needs. | - Difficulty in transferring tacit knowledge. - Knowledge management systems are subject to technological infrastructure and available connectivity. - The stored information must be constantly updated. - The massive availability of data requires appropriate filtering and analysis tools. | - Knowledge bases, databases, data mining, data warehouses, expert systems, intelligent agents, electronic reports, wikis, and document repositories. - Active and asynchronous interaction, Microsoft Teams and Skype for Business, video/audio recordings, digital discussion platforms, and video conferences. |

| De Freitas-Fernández et al. [47] | - Facilitate collaboration and improve daily teaching activities. - Sharing of experiences through exchange networks. | - | - Exchange networks, personal pages, mobile technology, email. |

| Escorcia et al. [49] | - Facilitation of access to relevant information.

- Promotion of knowledge distribution. - Issues with the adoption of collaborative tools. | - Lack of clear policies for access and use of institutional repositories.

- Low adoption of collaborative tools. | - Intranet, virtual libraries, educational virtual platforms, scientific databases, collaboration and project management platforms. |

| Escorcia et al. [50] | - Cooperation with research groups.

- Creation and dissemination of knowledge in higher education institutions. | - | - |

| Horban, et al. [55] | - Increased cognitive level by fostering creativity, transformational leadership, and the ability to manage information.

- Strengthening leadership and innovative management through adaptation to complex and constantly changing environments. - At the technological level, the incorporation of ICT facilitates the accumulation, transfer, and management of knowledge within universities. | - Challenges in integrating organizational and informational cultures.

- Regional differences persist in organizational culture and in the implementation of knowledge management. - Difficulty in transferring knowledge between regions due to technological and economic differences. | - Coworking spaces as tools for knowledge exchange. |

| Inrawan [56] | - ICT facilitates the exchange of knowledge, the creation of new ideas, and innovative processes. | - The use of technologies for knowledge sharing depends on the perception of users, which could lead to variations in results.

- The study had no significant impact on knowledge exchange within the mentorship program. | - Structured questionnaires, Bootstrap method with PLS, Hofstede’s Organizational Culture Model. |

| Montoya-García & Laserna-Palomino [43] | - Facilitate the socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization of knowledge. | - Low use of technological components. | - Shared folders, email, blogs. |

| Morales, et al. [54] | - ICT has strengthened distance education through virtual modalities that enhance interactivity, connectivity, and access to knowledge without time and space restrictions.

- They provide access to a large amount of digitized information, facilitating constant updates for both teachers. - Use of innovative pedagogical strategies, such as gamification, problem-based learning, and blended learning. | - Limited technological resources

- Resistance to change - Lack of motivation due to reduced social interaction - Lack of teacher training | - Virtual platforms, bibliographic managers, learning networks, virtual libraries, and databases. |

| Moreno [57] | - Facilitation of the exchange of educational resources.

- Promotion of innovative and collaborative educational practices. | - | - Forums, chats, wikis, email, hyperlinks to websites, and links to videoconferences. |

| Muhisn et al. [51] | - Knowledge transfer through the use of the e-Learning Management System (eLMS).

- Facilitates knowledge sharing through socialization. - Flexible access to learning and encouragement of interaction through forums, emails, and online discussions. | - Dependence on the instructor rather than collaboration with peers to acquire knowledge.

- Asynchronous interactions that may hinder an immediate response to questions. - Limited use of social tools in terms of time. | - Discussion forums, Email, Videoconferencing and virtual sessions, Collaborative platforms, Online assessment systems. |

| Ocaña-Fernández et al. [46] | - Generation and transfer of knowledge. | - Need for adequate teacher training. | - Virtual platforms, data clouds, and artificial intelligence. |

| Padilla-Hernández et al. [41] | - Facilitation of collaborative learning environments.

- Improvement of teacher professional development. - Reflection on pedagogical practices. - Strengthening of teachers’ digital competencies. - Improvement of teaching-learning strategies. | - Lower impact of ICT on inter-institutional collaboration. | - |

| Paudel [59] | - Association between knowledge management and academic performance of teachers in terms of research, innovation, interactive learning, and capacity development. | - The research was based on data from four universities in Nepal.

- The study focuses on the individual behavior of teachers. | E-learning platforms and e-portals, Social networks (Viber, Skype, Twitter, Facebook), Simulators and interactive tools. |

| Rodríguez-Paredes and Ledesma-Pérez [44] | - Enable ubiquitous learning, providing flexibility in teaching processes. | - Continuous training in the use of ICT. | - Blackboard Ultra, Zoom, and other digital resources. |

| Saeed et al. [58] | - Improvement in the performance of virtual teams through knowledge exchange.

- Generation of more innovative solutions. | - Lack of trust among members affects the willingness to share knowledge.

- Lack of motivation influences the exchange of knowledge. | Videoconferencing, emails, wikis, SPSS, SmartPLS, surveys. |

| Silva [42] | - Improve interaction; promote collaborative learning. | - Lack of technological training for teachers.

- Lack of adequate infrastructure. | - Digital whiteboards, blogs, forums, wikis. |

| Syed et al. [60] | - The implementation of a knowledge sharing system for disseminating information and collaboration among teachers.

- Teachers encourage active knowledge sharing. - A well-designed knowledge-sharing system can help eliminate hierarchical barriers and improve cooperation among members of the academic community. - Prevention of the loss of valuable information when teachers leave the institution. | - Lack of a specific system for higher education.

- Low participation rates. - Some users may fear sharing their knowledge due to the perceived loss of power or competitive advantage. | - SharePoint, Slack, Yammer, HubSpot, LinkedIn, Moodle, Blackboard, and Canva, Microsoft Teams, Zoom, Google Meet, GitHub, Stack Overflow, Quora. |

| Toro-Córdova [45] | - Generation and sharing of knowledge among teachers.

- Improvement of teaching-learning strategies. | - Limitations in the use of virtual platforms. | - Moodle, Canvas, and Blackboard. |

| Torres-Flórez et al. [9] | - Strengthening of teachers’ digital competencies.

- Creation of innovative educational content. | - | - Cloud storage platforms, social networks, virtual learning platforms, spreadsheet software, reference management software, and statistical analysis software. |

| Vázquez-González et al. [48] | - Promote knowledge exchange. | - Lack of specific guidelines for information transfer. | - Blogs, wikis, social networks, KM systems such as electronic repositories. |

| Communication Competencies | Management Competencies | Digital Security Competencies | Pedagogical Competencies | Technological Competencies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time and resource management | ✓ | ||||

| Ability to design and plan online learning activities | ✓ | ||||

| Knowledge of security measures and privacy in the use of IT | ✓ | ||||

| Effectiveness in digital communication | ✓ | ||||

| Assessment of student progress | ✓ | ||||

| Familiarity with content creation and data analysis software | ✓ | ||||

| Ability to facilitate online interaction and collaboration | ✓ | ||||

| Handling of digital communication and collaboration tools | ✓ | ||||

| Organization and management of virtual courses | ✓ | ||||

| Efficient use of tools for access to resources | ✓ | ||||

| Efficient use of learning management platforms | ✓ |

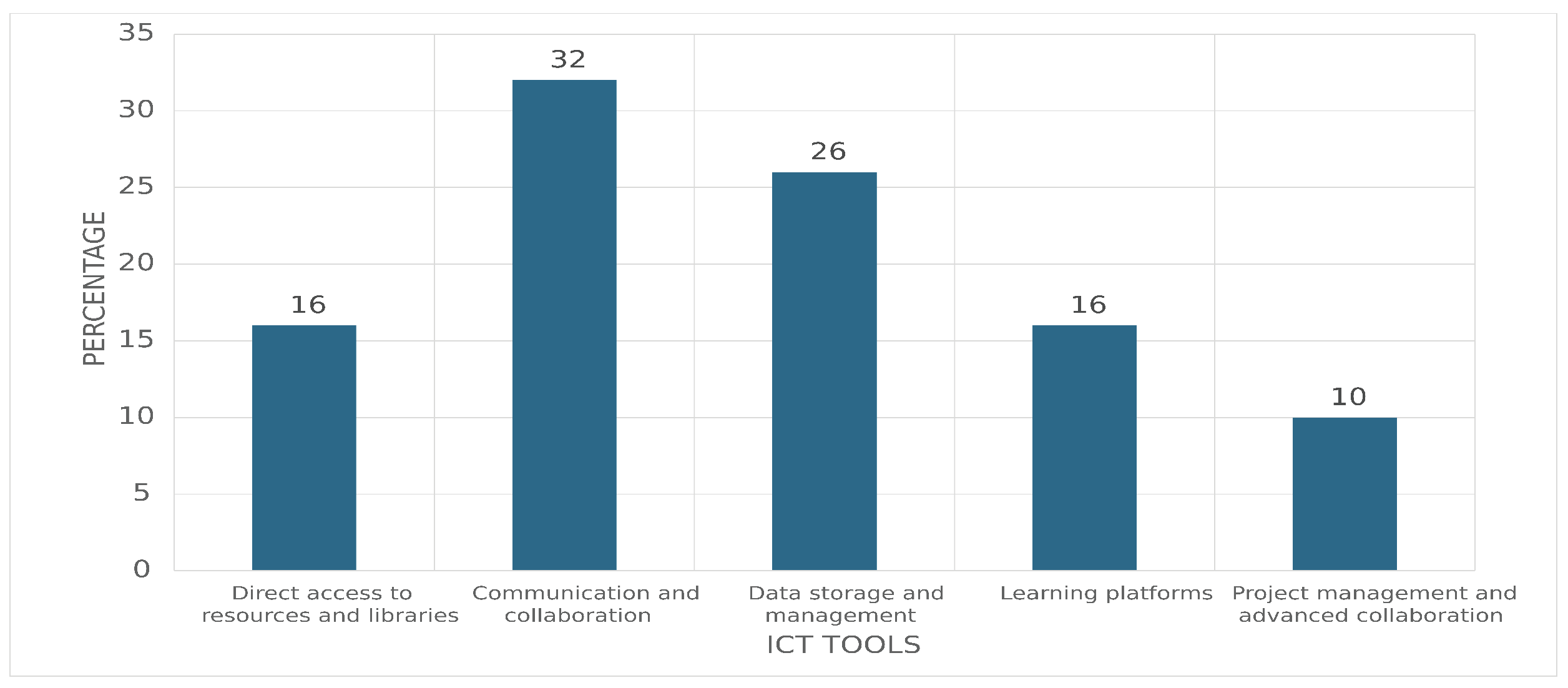

| Access to Resources and Libraries | Data Storage and Management | Communication and Collaboration | Project Management and Advanced Collaboration | Learning Platforms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication Competencies | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Management Competencies | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Digital Security Competencies | ✓ | ||||

| Pedagogical Competencies | ✓ | ||||

| Technological Competencies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Article | Observer | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mendoza & Bullón [1] | Obs1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | Yes |

| Obs2 | Yes | CA | Yes | CA | No | Yes | No | CA | No | No | CA | |

| Obs3 | Yes | CA | Yes | CA | No | Yes | - | CA | No | No | CA | |

| Meza & Mendoza [61] | Obs1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | Yes |

| Obs2 | CA | No | Yes | CA | CA | Yes | CA | CA | No | No | CA | |

| Obs3 | Yes | CA | Yes | CA | No | No | CA | CA | No | No | CA | |

| Mercado y Morales [62] | Obs1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | Yes |

| Obs2 | Yes | CA | Yes | CA | No | Yes | Yes | CA | CA | CA | CA | |

| Obs3 | CA | CA | Yes | CA | CA | Yes | No | CA | No | No | CA | |

| Meza et al. [63] | Obs1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | Yes |

| Obs2 | Yes | CA | Yes | No | CA | Yes | No | CA | CA | CA | CA | |

| Obs3 | Yes | CA | Yes | CA | CA | CA | CA | CA | CA | No | No | |

| Campa y Lozano [64] | Obs1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | Yes |

| Obs2 | Yes | CA | Yes | No | CA | CA | CA | CA | CA | CA | CA | |

| Obs3 | Yes | CA | Yes | No | Yes | No | CA | CA | No | CA | No | |

| Cuevas et al. [65] | Obs1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | Yes |

| Obs2 | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | CA | CA | CA | |

| Obs3 | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | CA | |

| Basilotta et al. [66] | Obs1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | Yes |

| Obs2 | CA | CA | No | CA | No | Yes | No | No | CA | No | CA | |

| Obs3 | Yes | CA | No | Yes | CA | Yes | No | CA | No | No | No | |

| González & Jasso [67] | Obs1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | Yes |

| Obs2 | CA | No | CA | CA | No | CA | No | CA | CA | CA | CA | |

| Obs3 | CA | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Solano et al. [68] | Obs1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | Yes |

| Obs2 | Yes | CA | Yes | No | CA | Yes | CA | CA | CA | CA | CA | |

| Obs3 | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | CA | CA | |

| OURS | Obs1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | No | Yes | CA | CA | CA | CA | No |

| Obs2 | Yes | CA | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | CA | CA | Yes | Yes | CA | |

| Obs3 | Yes | CA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | CA | CA | CA | CA | CA |

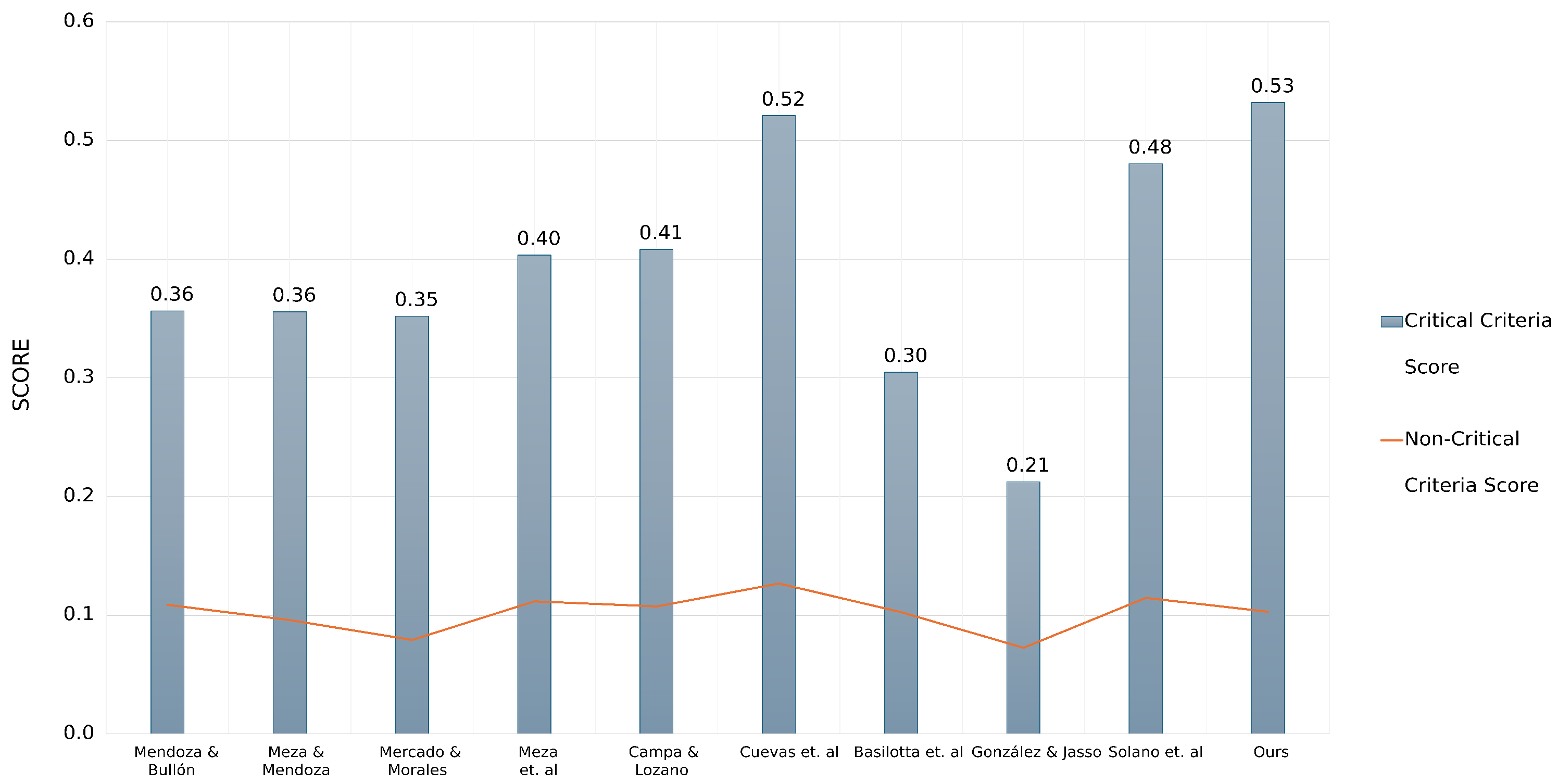

| Items | AHP Value | Mendoza & Bullón [1] | Meza & Mendoza [61] | Mercado & Morales [62] | Meza et al. [63] | Campa & Lozano [64] | Cuevas et al. [65] | Basilotta et al. [66] | González & Jasso [67] | Solano et al. [68] | Ours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2 | 0.2680 | 0.1787 | 0.1340 | 0.1787 | 0.1787 | 0.1787 | 0.1787 | 0.1787 | 0.0893 | 0.1787 | 0.1787 |

| Q3, Q4 | 0.1854 | 0.1391 | 0.1391 | 0.1082 | 0.1236 | 0.1082 | 0.1700 | 0.0927 | 0.0773 | 0.1391 | 0.1236 |

| Q7 | 0.1318 | 0.0000 | 0.0439 | 0.0000 | 0.0220 | 0.0439 | 0.0879 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0659 | 0.0659 |

| Q8 | 0.1160 | 0.0387 | 0.0387 | 0.0387 | 0.0387 | 0.0387 | 0.0580 | 0.0193 | 0.0193 | 0.0580 | 0.0580 |

| Q9 | 0.0843 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0141 | 0.0281 | 0.0141 | 0.0141 | 0.0141 | 0.0141 | 0.0141 | 0.0562 |

| Q10 | 0.0743 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0124 | 0.0124 | 0.0248 | 0.0124 | 0.0000 | 0.0124 | 0.0248 | 0.0495 |

| Q1 | 0.0504 | 0.0504 | 0.0420 | 0.0252 | 0.0504 | 0.0504 | 0.0504 | 0.0420 | 0.0336 | 0.0504 | 0.0504 |

| Q5 | 0.0362 | 0.0121 | 0.0181 | 0.0181 | 0.0241 | 0.0301 | 0.0301 | 0.0181 | 0.0121 | 0.0181 | 0.0241 |

| Q6 | 0.0312 | 0.0312 | 0.0208 | 0.0208 | 0.0260 | 0.0156 | 0.0312 | 0.0312 | 0.0156 | 0.0312 | 0.0208 |

| Q11 | 0.0225 | 0.0150 | 0.0150 | 0.0150 | 0.0113 | 0.0113 | 0.0150 | 0.0113 | 0.0113 | 0.0150 | 0.0075 |

| Recommendation | Description |

|---|---|

| Strengthening digital competencies | - Implement continuous training programs in digital competencies for teachers, focused on the effective use of ICT for knowledge management.

- This includes practical and up-to-date courses that promote the integration of digital tools into teaching. |

| Improvement in knowledge distribution | - Establish clear policies and procedures for the management and distribution of knowledge within educational institutions.

- This could include the creation of accessible institutional repositories and the active promotion of knowledge-sharing practices among teachers. |

| Promotion of collaborative environments | - Foster the creation of communities of practice and collaborative networks among teachers, using digital platforms and educational social networks.

- This can facilitate the continuous exchange of ideas, resources, and best pedagogical practices. |

| Incentives for educational innovation | - Implement institutional incentives that recognize and promote educational innovation through the creative and effective use of ICT.

- This could include awards, recognitions, or financial support for innovative projects that enhance educational quality. |

| Continuous research and impact evaluation | - Support ongoing research on the impact of ICT-based KM strategies on teachers’ learning and professional development.

- This could include longitudinal studies and systematic evaluations to measure the long-term effects of these strategies. |

| Adoption of institutional policies | - Develop and adopt institutional policies that actively promote the strategic use of ICT for knowledge management across all faculties and academic departments.

- This could include integrating ICT as an integral part of curriculum planning and teacher professional development. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero-Ochoa, M.-A.; Romero-González, J.-A.; Perez-Soltero, A.; Terven, J.; García-Ramírez, T.; Córdova-Esparza, D.-M.; Espinoza-Zallas, F.-A. Knowledge Management Strategies Supported by ICT for the Improvement of Teaching Practice: A Systematic Review. Information 2025, 16, 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050414

Romero-Ochoa M-A, Romero-González J-A, Perez-Soltero A, Terven J, García-Ramírez T, Córdova-Esparza D-M, Espinoza-Zallas F-A. Knowledge Management Strategies Supported by ICT for the Improvement of Teaching Practice: A Systematic Review. Information. 2025; 16(5):414. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050414

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero-Ochoa, Miguel-Angel, Julio-Alejandro Romero-González, Alonso Perez-Soltero, Juan Terven, Teresa García-Ramírez, Diana-Margarita Córdova-Esparza, and Francisco-Alan Espinoza-Zallas. 2025. "Knowledge Management Strategies Supported by ICT for the Improvement of Teaching Practice: A Systematic Review" Information 16, no. 5: 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050414

APA StyleRomero-Ochoa, M.-A., Romero-González, J.-A., Perez-Soltero, A., Terven, J., García-Ramírez, T., Córdova-Esparza, D.-M., & Espinoza-Zallas, F.-A. (2025). Knowledge Management Strategies Supported by ICT for the Improvement of Teaching Practice: A Systematic Review. Information, 16(5), 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050414