Building a Cybersecurity Culture in Higher Education: Proposing a Cybersecurity Awareness Paradigm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

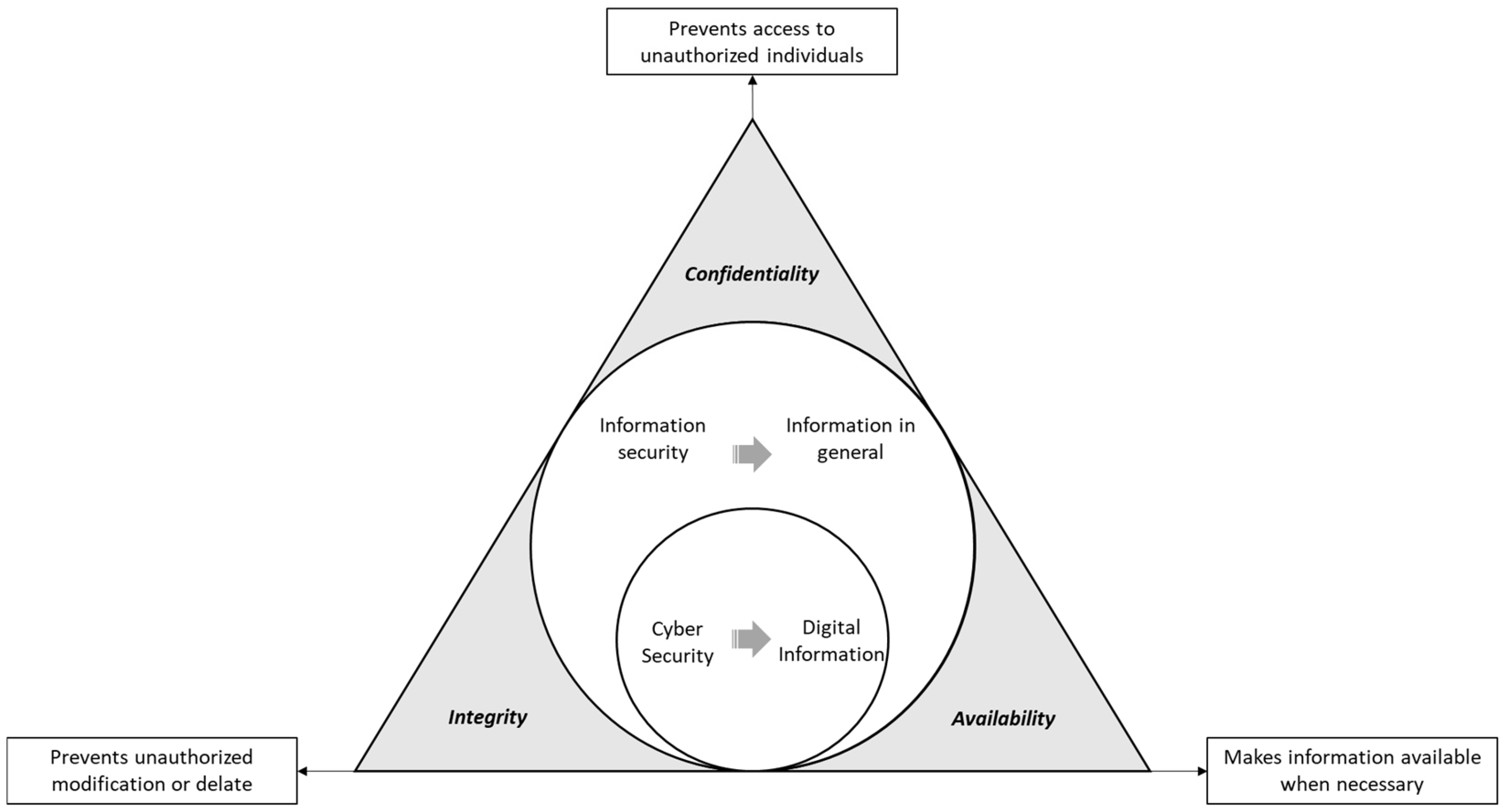

2.1. Information Security and Cybersecurity

- Confidentiality: the prevention of unauthorized people from having access to information;

- Integrity: the prevention of information from being modified or destroyed by unauthorized individuals;

- Availability: making information available for authorized users when necessary.

2.2. Importance of Information Security

2.3. Who Is Information Security for?

2.4. Information Security Training and Awareness

2.5. Benefits of Implementing an Information Security Awareness and Training Program

- Regulatory Benefits: This is one of the primary rationales behind this process. However, while specific laws governing information security and privacy vary across countries, their fundamental purpose remains constant: safeguarding citizens and organizations from potential harm. In most legal and regulatory requirements, the adherence to these protocols is pivotal, and awareness training serves as evidence of compliance. Typically, following the process is mandatory for all employees; such training can also be tailored to cater to the needs of executives and business lines.

- Benefits to Business Organizations: Serving to establish organizational policies, foster a secure environment, and cultivate a uniform security posture throughout the organization. These programs assist in defining the levels of data sensitivity, addressing concerns related to mobile media, and accentuate the prevention of identity theft. Furthermore, they act as a shield for the organization’s reputation by pre-empting security breaches and data losses, ultimately nurturing a secure and compliant operational milieu.

- Personal and Employee Benefits: Beyond the organizational sphere, these training programs extend tangible benefits to individuals and employees. They educate individuals about the legal and ethical aspects of safeguarding data, thereby underscoring personal accountability for data mishandling, particularly within a professional context. By imparting knowledge and promoting responsible cybersecurity practices, employees could also assume the role of mentors, sharing insights into cybersecurity best practices with colleagues. These training programs not only fortify personal cybersecurity but also extend to securing sensitive family information and reinforcing ethical conduct in online interactions.

2.6. The Higher Education Industry

2.7. Why Has the HE Industry Become More Desirable to Cyber Attackers?

2.8. Comparison Between the Security Level Applied in HE and Other Industries

2.9. Information Security Frameworks and Its Contributions to Awareness and Training Programs

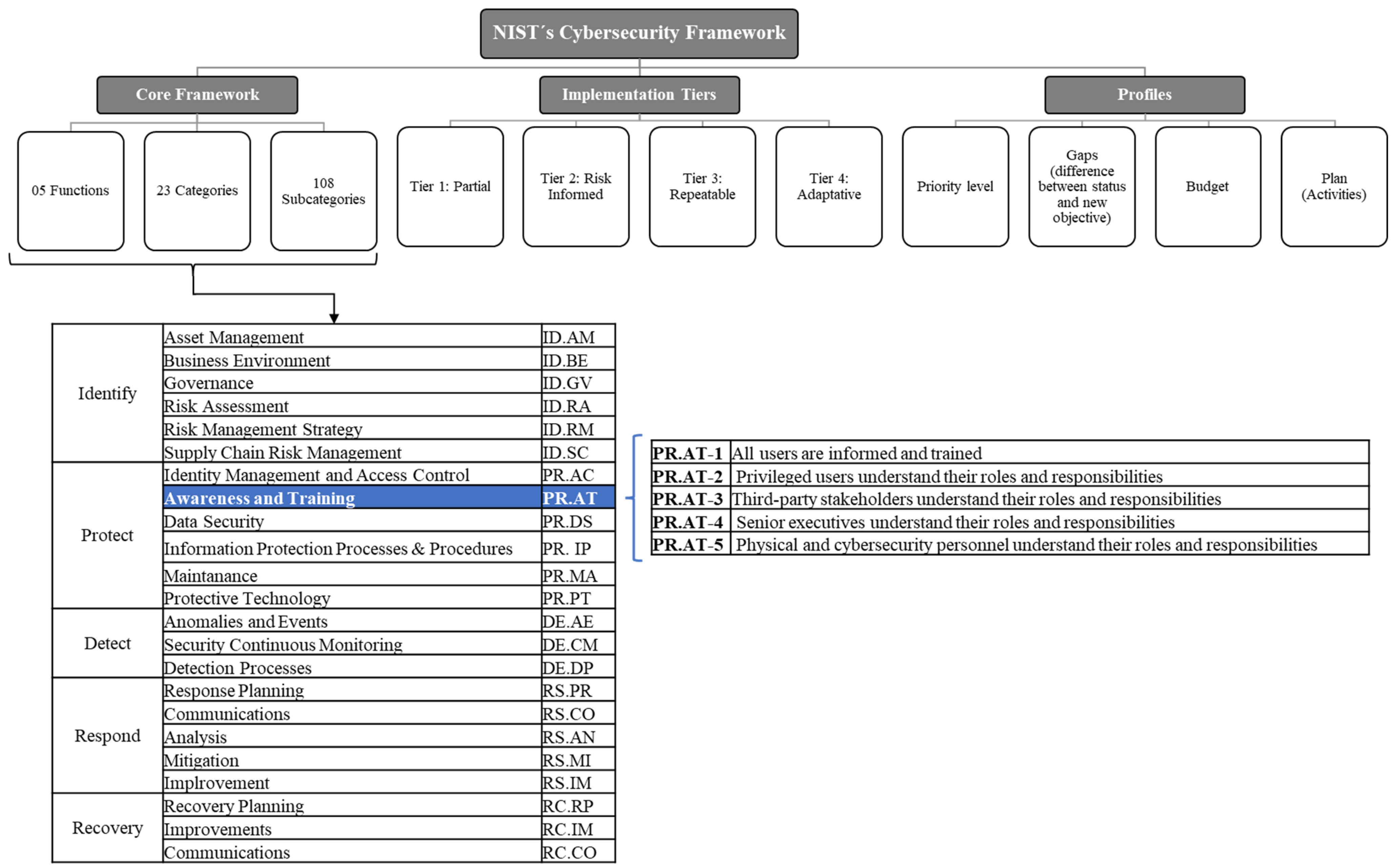

2.9.1. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

- NIST SP 800-16. This special publication contains a model that supports the establishment of a professional team in charge of information security, highlighting the awareness, training, and education that each individual needs according to the role that they play in the institution, thereby providing a guide for management of training programs in information technology and cybersecurity [17].

- NIST SP 800-50. This special publication is a compendium of detailed requirements for the creation of an awareness and information security training program divided into the following four sections: the first is dedicated to the design of the program, the second to the development of material to be used in the program, the third to the implementation of the program, and, finally, the fourth to the processes related to post-implementation [16].

- NIST SP 800-53. Chapter 3.2 of this publication provides specific aspects related to user awareness and training. It provides a list of requirements necessary for developing an awareness and training program based on roles, policy, and procedures, literacy training and awareness, the control of the training carried out, the interpretation of its results, and feedback [51].

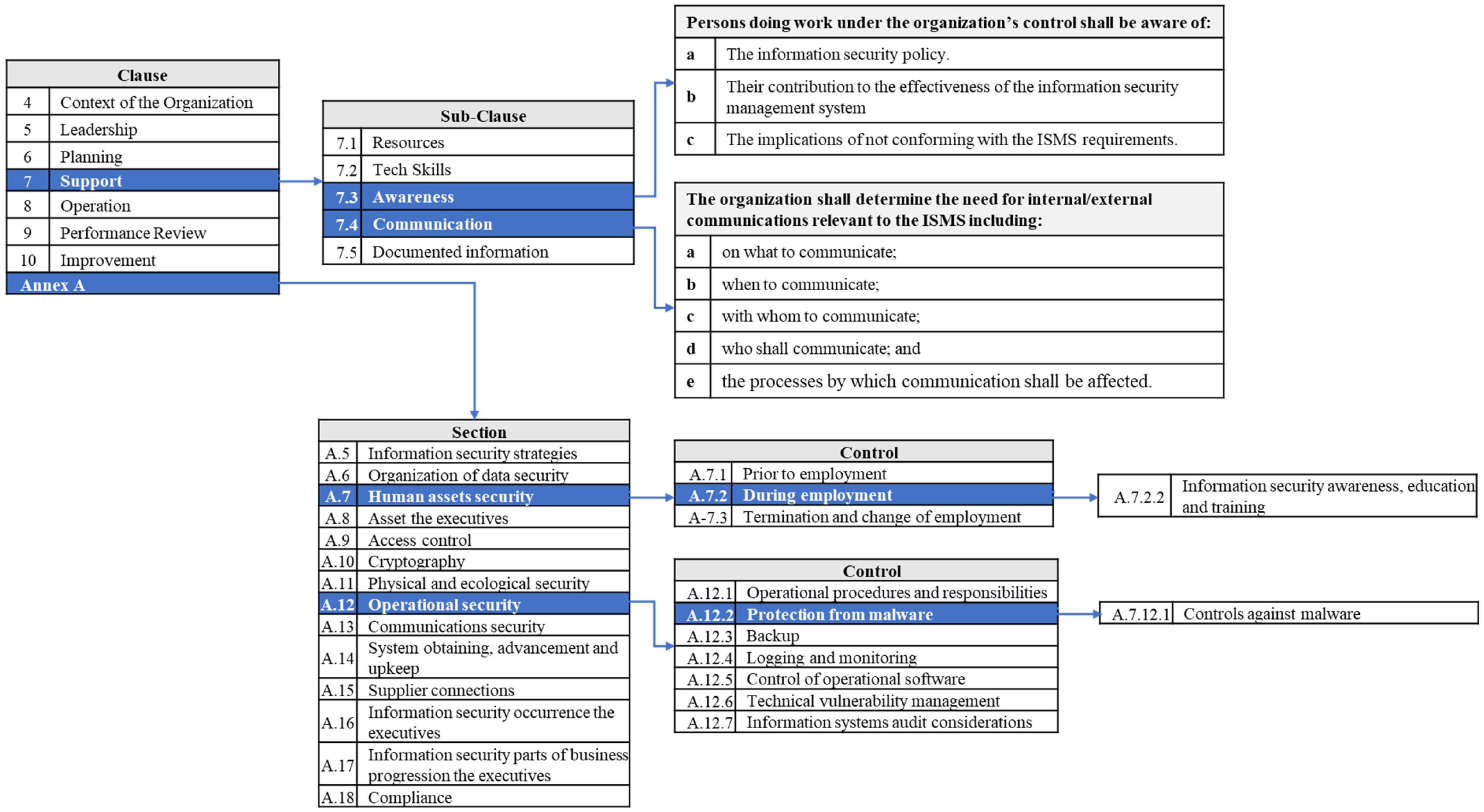

2.9.2. ISO/IEC 27001

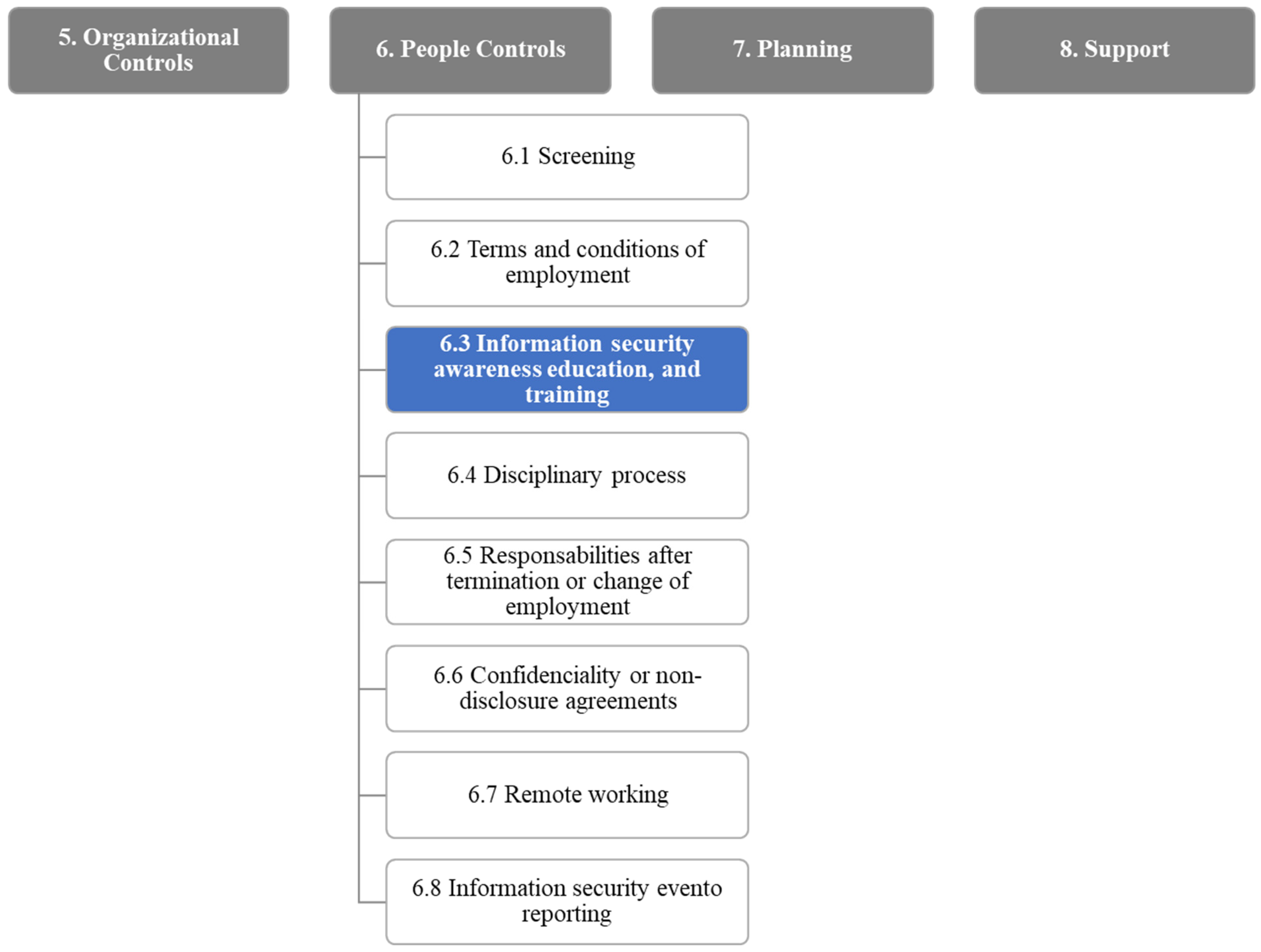

2.9.3. ISO/IEC 27002

2.9.4. SANS Security Awareness Maturity Model

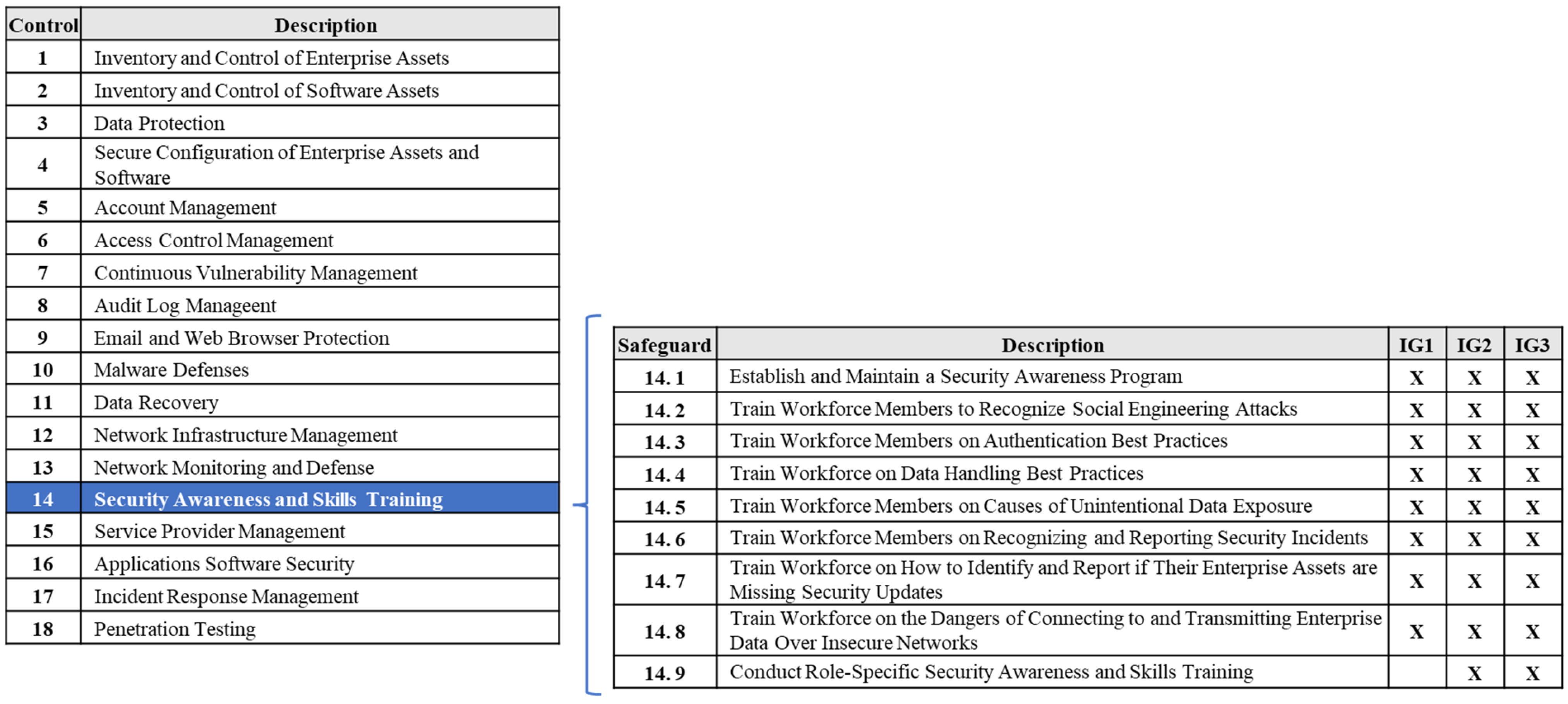

2.9.5. Center for Internet Security Controls Version 8 (CIS Controls v8)

2.9.6. Control Objectives for Information and Related Technologies (COBIT)

2.9.7. Cybersecurity Awareness Framework for Academia (CAFA)

- The framework is mainly aimed at the integration of security modules with study programs, but it does not include other audiences that are also part of the organization; not including them in the program is a risk for the organization. In the specific case of HE, students, administrative staff, professors, senior executives, third-party stakeholders, and physical and cybersecurity personnel clearly define how to classify content according to the type of audience, as the NIST’s Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity recommends [50]. In addition, ISO/IEC 27001 and the CIS Critical Security Controls indicate that every member of the organization must be included in the awareness and training program during the period that they are part of the institution [18,20,50,53].

- Since this is a theoretical framework, this will be felt more in training being evaluated based on games, which represents an opportunity for improvement by combining it with periodic phishing campaigns that allow for the emulation of real attacks, and thus to complement the feedback for the design and program adjustment [18,20,50,53].

- Another opportunity for improvement comes from other complementary activities, such as sending periodic newsletters, where, in addition to delivering content related to the organization’s cybersecurity culture, it is also constantly reporting on latent threats [16].

- Finally, the development of an Information Security Culture that constantly promotes and serves as a reminder on the topic of information security across the organization is encouraged through awards and recognition [51].

2.10. Technical Enhancements and Emerging Technologies

2.10.1. AI/ML for Adaptive Training and Threat Prediction

2.10.2. Blockchain for Data Integrity and Privacy Protection

2.10.3. Zero-Trust Architecture (ZTA)

3. Materials and Methods

- Prove that there is a need for a tailored Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Framework that contributes to improving the security levels of HE institutions, specifically in aspects related to people’s behavior and the implementation of best security practices, so to protect the information that these users handle during their time in the organization; this information is explained and developed in the Problem Statement section of this document.

- Analyze the best-known international information security frameworks and previous studies, as well as their contribution/recommendations in establishing user awareness and training programs, which are presented in the Literature Review section of this research work.

- Make use of the information collected to create a framework specifically adapted to the HE industry, with the flexibility that it can be adapted for organizations of different sizes and at different levels of maturity. This, in turn, will allow HE institutions to stay updated and remain in a process of continuous improvement in the construction of information security systems, supported by trained users capable of identifying threats related to social engineering and errors due to lack of knowledge or lack of education in this matter, which is explained in the next section of this document.

4. Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Framework for Higher Education (CA&TF for HE)

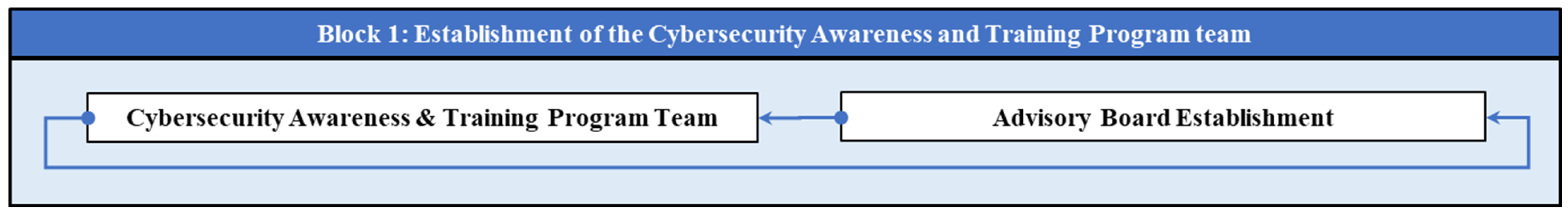

4.1. Block 1: Establishment of the Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program Team

4.1.1. Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program Team Establishment

4.1.2. Cybersecurity Advisory Board Establishment

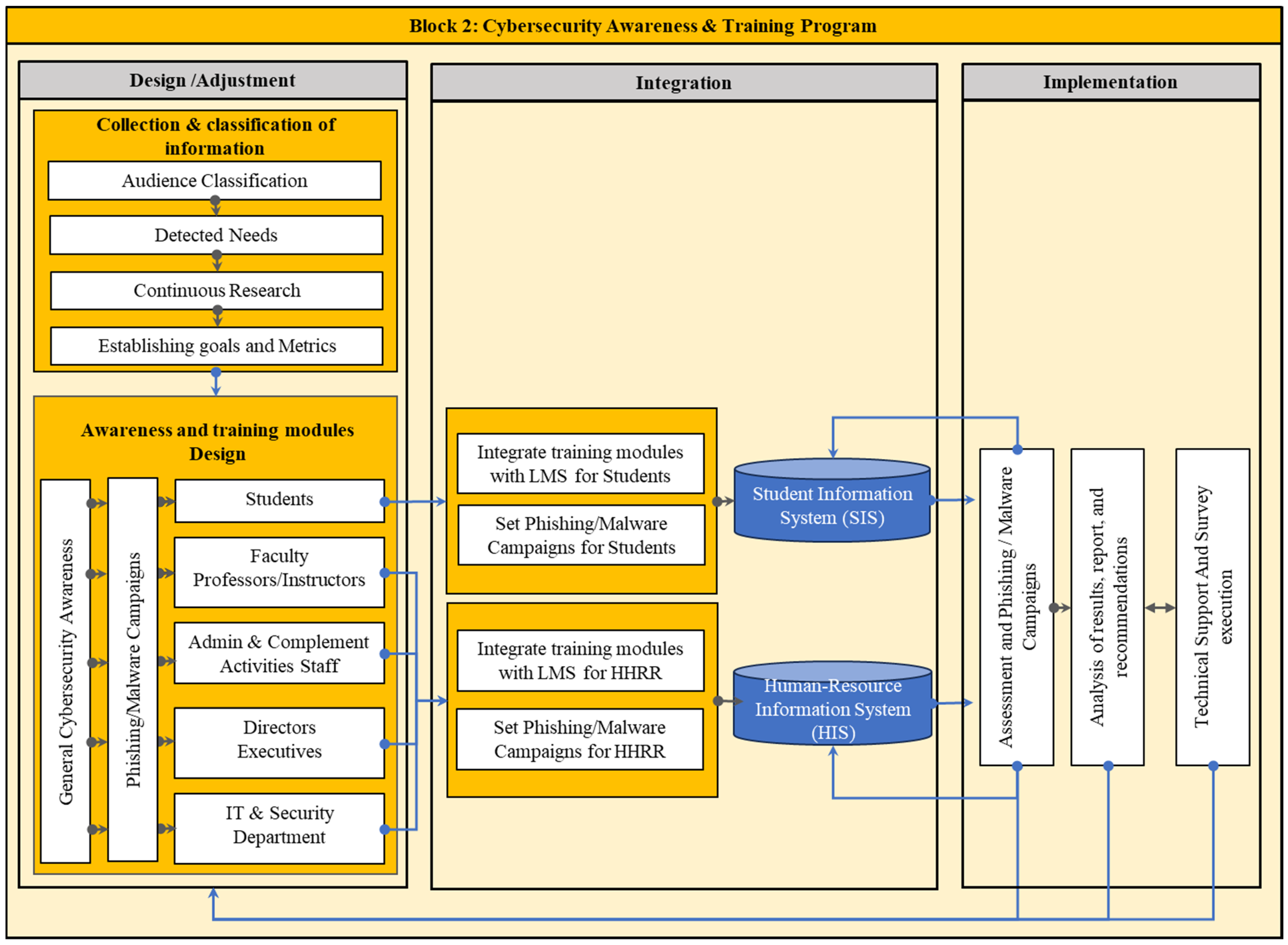

4.2. Block 2: Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program

4.2.1. Design/Adjustment

- Students: the largest group/audience.

- Faculty: professors and instructors.

- Administration and Support Activities Staff: Finance, Human Resources, the Registry Office, Student Services, and Marketing, Legal, and Compliance.

- Directors and Executives: President or Chancellor, directors, deans, and executives.

- Information Technology (IT) and Security Department: This department oversees the technology infrastructure, including networks, computer labs, and academic technology support. They will define and implement security controls and ensure the security, integrity, and availability of information assets.

- General and transversal alignment with the Cybersecurity Awareness Strategy of the institution;

- Institutional cybersecurity policies alignment;

- Users’ accountabilities;

- Good practices of information security;

- General IT security concerns and those related to the HE industry;

- Threat and vulnerability trends related to the users;

- Focused attention and recognition of threats and vulnerabilities;

- A process to report detected and possible threats, vulnerabilities, and incidents;

- Cybersecurity news;

- Implications for not accomplishing the institutional policies and cybersecurity best practices.

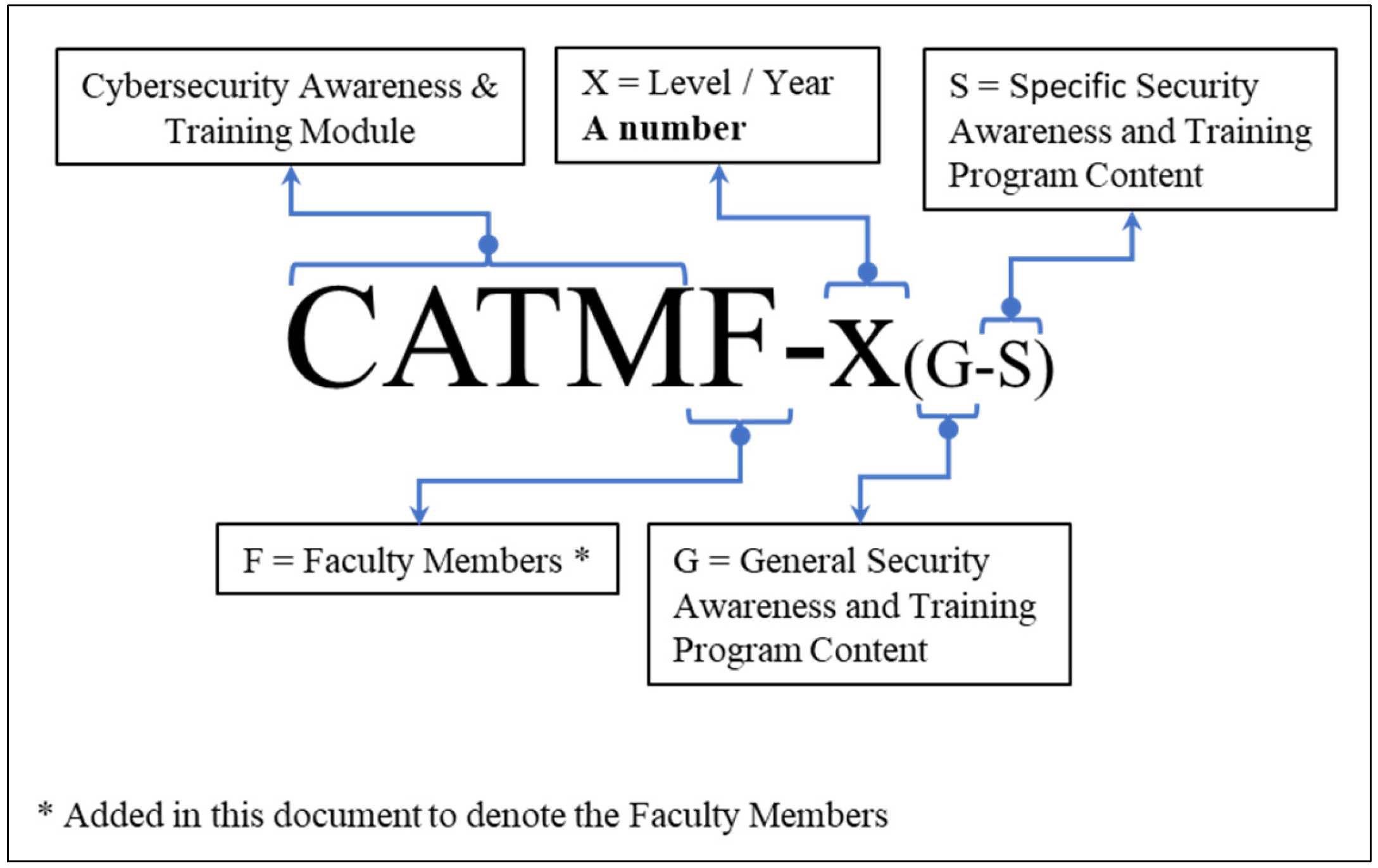

- Role-Based Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program—Students. As recommended by [59], a basis for the design of this subprogram is the creation of educational modules that can be merged with the academic content taught in each year of study of the program (in the case of studies that are completed in at least one year). However, to adjust this model to any program taught by HE institutions, regardless of their completion time, it is established that all students should at least be enrolled in the General Security Awareness and Training Program and the first module of Role-Based Awareness and Training for Students in such a way that this program may also include short academic programs.

- Role-Based Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program—Faculty Members: Faculty members fulfill a dual role within the program; in the same way, they are the audience, as they support the creation of the CATMS, which is why they require prior training on the topics defined in the continuous research phase, including recommendations from the report of results of previous cycles of evaluation and feedback obtained from the student audience. This is to provide them with a better definition of the material with cybersecurity information, which will complement and adjust the academic content and the CATMS according to the needs of each course. Therefore, following what was suggested by [59], faculty members will receive an induction consisting of a workshop that contains all of the information prepared in the Continuous Research section whenever it is necessary to modify or adjust the program for the student’s audience.

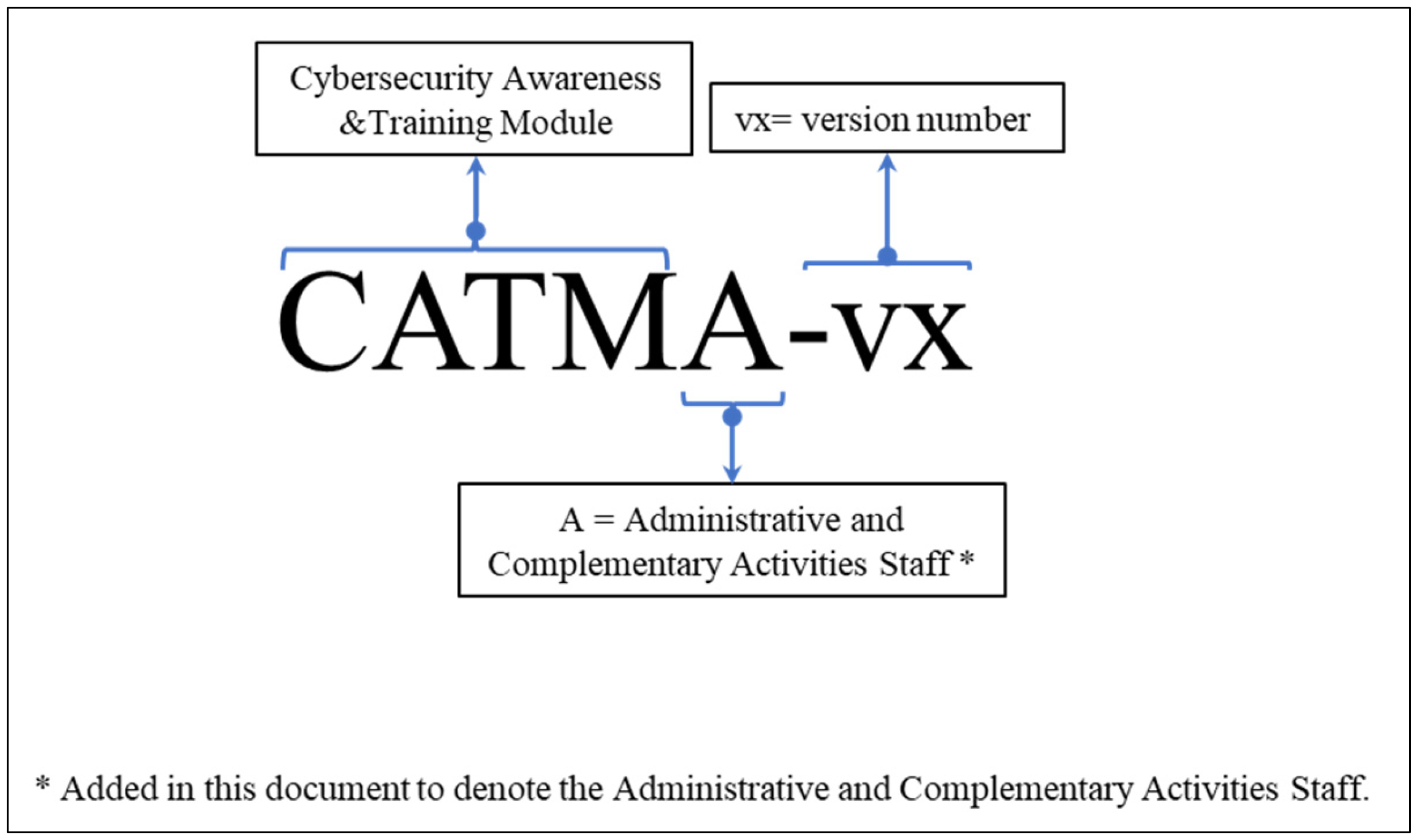

- Role-Based Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program—Administrative and Complementary Activities Staff. As for the two previous audiences, for the Administrative and Complementary Activities Staff, the creation of modules based on gamification/interactive exercises, specifically adjusted to the type of information, systems managed, and possible attack vectors related to this type of roles within of the institution, is recommended [17].

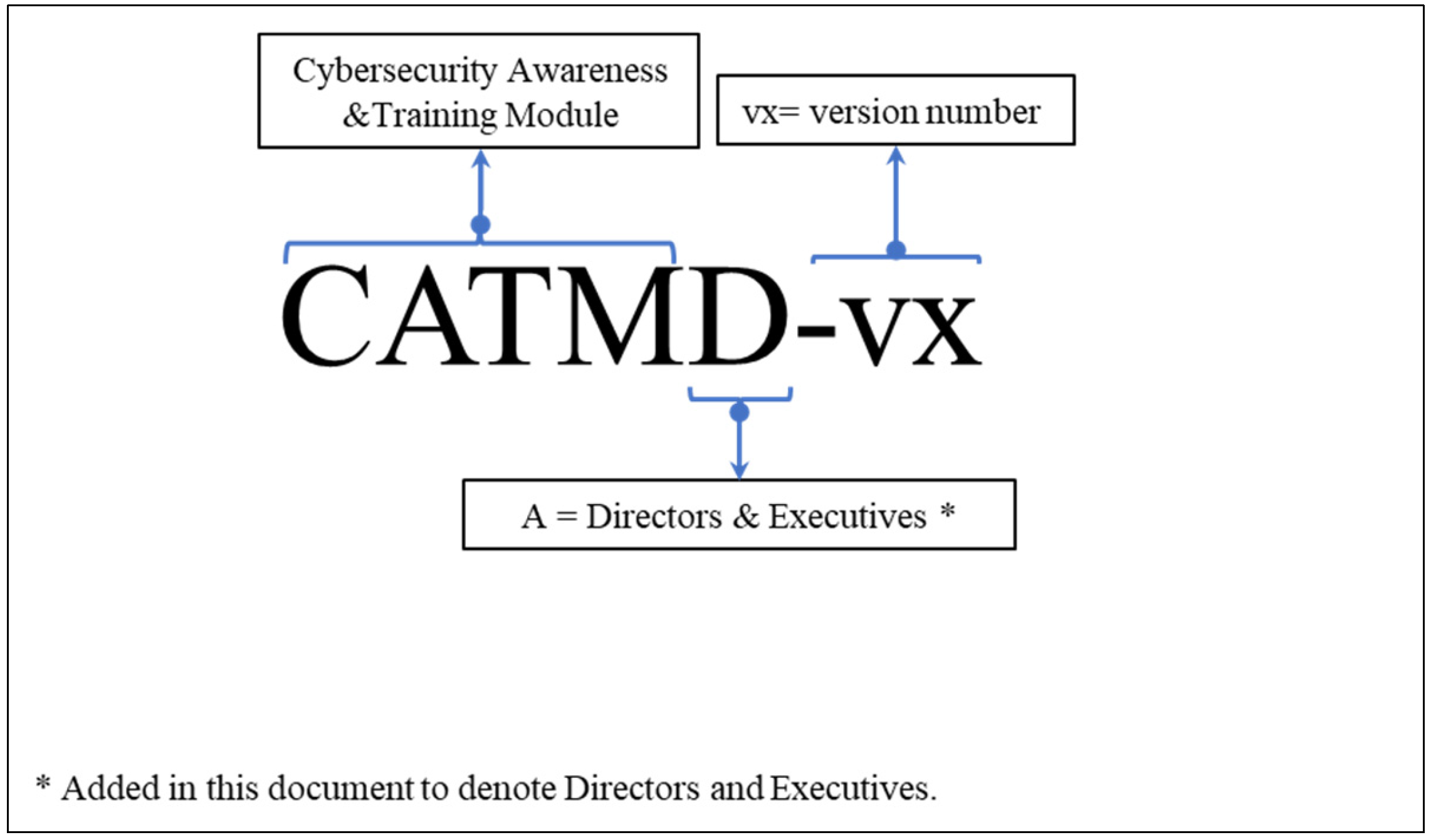

- Role-Based Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program—Directors and Executives Members. The description of this subprogram is very similar to the previous one, only adapted to the specific needs of this audience. Figure 14 shows a scheme for the proposed nomenclature for the Role-Based Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Module for Directors and Executive Members through the interpretation and adaptation of previous works by [59], where D refers to the audience in question and vx corresponds to the version of the module.

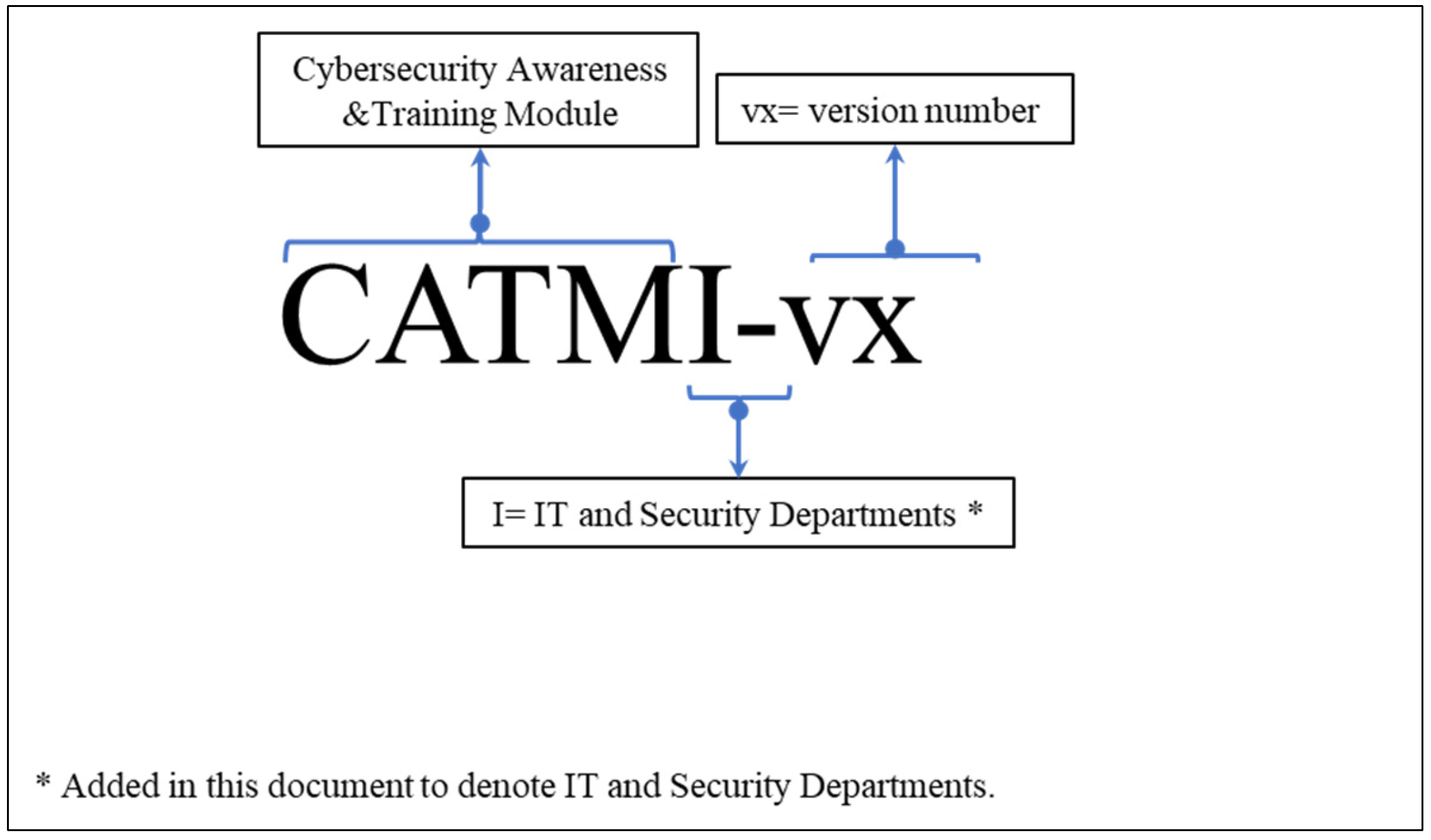

- Role-Based Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program—IT and Security Departments. The content of the program for this audience points more to specific technical knowledge of the subject, adapted to the roles that make up the area, the technology on which the organization’s infrastructure is based, and its internal processes. Figure 15 shows a scheme of the proposed nomenclature for the Role-Based Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Module for IT and Security Departments through the interpretation and adaptation of previous work by [59], and the requirements from NIST Especial Publication 800-16 [17] and NIST Special Publication 800-50 [16].

- Cybersecurity Essentials Program. This section is most related to roles in the Tech and Security team, and aligned with NIST SP 800-16 [17]. It recommends continuously updating the specialists and technical team in the fundamental base of knowledge aligned to the processes, infrastructure, and technology implemented in the organization. Therefore, it is recommended that the topics that the training of this audience can at least cover aspects such as basic concepts related to information security, cybersecurity, intrusion, social engineering, and challenges associated with the HE industry; common vulnerabilities and threats related to the type of system implemented in HE institutions, for example, eLearning systems; the most common attack vectors and those related to the HE industry; the weaknesses found in successful attacks; cryptography; perimeter defense infrastructure, incident prevention, security status monitoring, event log, attack prevention, and security controls; and the construction and development of information security and cybersecurity.

- Education/Specialization Cybersecurity Program. In favor of the continuous development and specialization of the relevant roles that require it, it is highly recommended that the organization develop a specialized education program for those professionals who must occupy positions with highly critical functions and which serve as experts in the subjects, thereby allowing them to keep the knowledge base updated and aligned with the latest technologies, trends, certifications, and high-level education. This will direct the formation of a robust technical team capable of delivering the most accurate recommendations and with the level of depth required for decision-making support, both at the high levels of governance and the direction of the organization, as well as in more specific aspects [17].

- Prepare periodic phishing campaigns where the contents of the theoretical modules can be evaluated in a real environment.

- Design campaigns that allow for the determination of the level of education of the users and that, in turn, is related to the risk levels of the organization according to the type of information and access to the system managed by each audience and each role. For example, a phishing campaign based on sending a trap email that contains a link, a downloadable file, and a request for data delivery. Each action can be associated with the level of risk it represents, allowing for adjustments to be prioritized in the design of the content based on risk mitigation.

- Design campaigns adjusted to real scenarios where each audience develops, to the season of the year, and to the specific events of the moment so to make them more realistic. For example, an email promoting the purchase of a book associated with a specific program at the beginning of an academic cycle.

4.2.2. Integration

- Integrate Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Modules on the LMS. For this specific case, the CATMS is integrated into the LMS that the institution uses to deliver the academic content of each course [59]. In the case of the rest of the audience, if the company has a training platform for its employees, the module groups CATMF, CATMA, CATMD, and CATMT can be integrated into this tool. Another option to make the content of the modules available can be on an Intranet. Other institutions may choose to purchase an eLearning platform license that allows them to adapt/customize/update the content to the context of each audience.

- Set Phishing/Malware Campaigns. Once the phishing campaigns are designed, they must be integrated and programmed to run on the systems used by the audiences, for example, email and directory service-developed whitelists within the company’s systems, so to prevent these campaigns from being blocked by the security infrastructure of the institution [82]. This activity is based on the configuration/activation of the program modules for each of the audiences according to the needs detected and the modules assigned, thus giving the level of awareness and training for each individual [16,17,55,56,58].

- It is important to note that the execution of phishing campaigns must be carried out in a controlled manner and by the support areas that will be involved in the activity [82]. For example, the institution may have a process for reporting attacks or threats detected by end-users, and already educated and trained users are expected to report the threat; if, in this case, the support or management team of this type of report is not aware of the exercise, the entire process is activated, and resources will be used unnecessarily.

- Integration with Information Systems. The organization’s information systems will integrate the information available from the Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program with the information and management of processes within the organization, thereby allowing the registration of available material, the results obtained, and the feedback resulting from the activities carried out in this process [59].

4.2.3. Implementation/Execution

- Specific individuals. For example, those individuals who occupy critical positions and manage the relevant information of the organization, as well as individuals who remain at a low level of awareness and training, and who possibly require greater attention and focus to advance through the levels of the program [82].

- The integration of the modules with the LMS, SIS, and SIHR.

- Monitoring of the correct functioning of the program modules.

- Attention to issues reported with the operation of the systems.

- In addition, it can also serve as the first instance in receiving reports of incidents and threats detected by users so to make a first filter or to discard false positives, for example, those reports made during a phishing/malware campaign, or errors in linking harmless emails with threats detected by a user.

- Additionally, the support team must record metrics related to the reports made by users and the generation of surveys related to the technical functioning of the program. These last two points serve as relevant inputs that must be included in the results report of the cycle in execution.

4.3. Block 3: Information Security Culture Program for Higher Education (ISCP for HEIs)

4.3.1. Awareness

- Sending periodic newsletters with information relevant to audiences and updated according to data linked to the industry.

- Information pill videos that are sent periodically through emails or work groups, for example, weekly 3-min videos.

- Posting on the institution’s communication channels.

- Workshops that educate people about information security in general (applied in the personal sphere).

- ISCPs for HEI mascot election.

- The celebration of Cybersecurity Day/Week.

- A cybersecurity-themed brunch.

- Posters in places with a greater influx of people, among others.

4.3.2. Desire

4.3.3. Knowledge

4.3.4. Ability

4.3.5. Reinforcement

- Criteria for Awards

- Performance Metrics. Awards will be based on specific performance metrics aligned with the objectives of the information security strategy. These metrics may include adherence to security protocols, participation in training, incident response efficiency, or other relevant key performance indicators established by the Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program team leaders and the Advisory Board.

- Impact on Culture. Nominees will be evaluated not only on their adherence to security practices but also on their contributions to fostering a culture of information security. This can encompass efforts to promote awareness, mentorship, or innovative solutions.

- Leadership as Change Agents. A key criterion for awards will be the extent to which individuals have acted as effective change agents, driving positive behavioral changes in their departments or teams.

- Nominations. Nominations for awards can come from peers, supervisors, or self-nominations, highlighting a democratic and inclusive approach to recognizing achievements.

- Selection Process

- An Award Committee: A dedicated Award Committee will be established, consisting of representatives from various organizational levels, including senior management, information security professionals, and key stakeholders. The committee will ensure a fair and unbiased selection process. This activity could also be carried out by the Advisory Board.

- Evaluation and Scoring: The Award Committee will evaluate nominations based on the established criteria and score each nominee. This evaluation will be data-driven, with a focus on quantifiable achievements.

- Transparent Process: The selection process will be transparent and communicated to all stakeholders. The award categories and criteria will be publicly available.

- Award Ceremony: A culminating event, such as the closing ceremony of Cybersecurity Week, will serve as the platform for announcing and celebrating the award recipients. This ceremony will be an opportunity to share best practices and inspire others to excel in the realm of information security.

- Award Categories

5. Discussion

5.1. Establishment of the Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program Team and Cybersecurity Advisory Board

5.1.1. Creation of the Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program Team

5.1.2. Cybersecurity Advisory Board Establishment

- Strategic objectives of the institution.

- Institutional culture.

- Operation and integration of processes, systems, and people.

- Learned lessons.

5.2. Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program

5.2.1. Design/Adjustment

- Based on the information obtained from the organizational analysis meetings between the Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program team and the Advisory Board, the organization must be segmented into audiences according to the groups that make it up (students, faculty/professors, administrative staff, directors/executives, the IT and Security Department, and others that cannot be classified in the previous groups).

- Identify the awareness and training needs of each audience according to their role, and the information and systems that they manage.

- Establish a continuous research process that can be based on, but which is not limited to, the investigation of HE industry trends, tech trends, incidents, vulnerabilities trends, and case studies of cyberattacks in other institutions in the same and different areas. This activity can be performed in parallel with the beginning of the organization’s analysis, so that people’s knowledge needs also influence the research strategy and objectives.

- Based on the above, the Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program team and the Advisory Board must establish metrics and indicators to monitor compliance with the strategy. An awareness and training schedule must also be established.

- At this point, it is important to have defined the scope of the program and whether the design of the awareness and training modules will be developed partially or completely.

5.2.2. Integration

- Once the program design is completed, it will be important to confirm the systems and areas with which it must interact and that were initially identified by the Cybersecurity Advisory Board. This is to ensure that all actors are involved in the process.

- Develop an integration plan for the training modules with the LMS for students and the HHRR of the institution, as well as the student and HHRR information systems.

- Establish test times before releasing the program into production so to validate that the system and the program are working without problems.

5.2.3. Implementation/Execution

5.3. Information Security Culture Program for Higher Education (ISCP for HEIs)

5.4. Integration of CA&TF for HE Blocks and Information Flow

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista Research Department. Spending on Digital Transformation Technologies and Services Worldwide from 2017 to 2026 (in Trillion U.S. Dollars); Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Research Department. Global Annual Growth Rate of Spending on Cyber Security from 2019 to 2026, by Industry Sector; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Security. X-Force Threat Intelligence Index 2023; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Amorosa, K.; Yankson, B. Human Error—A Critical Contributing Factor to the Rise in Data Breaches: A Case Study of Higher Education. Holistica J. Bus. Public Adm. 2023, 14, 110–132. [Google Scholar]

- Armas, R. Information Security Awareness in Higher Education: The Need for a Tailor-Made Suit; C2SA: Agadir, Morocco, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Asher, N.; Gonzalez, C. Effects of Cyber Security Knowledge on Attack Detection; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, N.; Ikram, N.; Murtaza, H.; Javed, M. Evaluating Protection Motivation Based Cybersecurity Awareness Training on Kirkpatrick’s Model. Comput. Secur. 2023, 125, 103049. [Google Scholar]

- Ulven, J.; Wangen, G. A Systematic Review of Cybersecurity Risks in Higher Education. Future Internet 2021, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Security. Cost of a Data Breach Report 2023; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- SonicWall. 2023 SonicWall Cyber Threat Report; SonicWall: San Jose, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft Security Intelligence. Global Threat Activity; Microsoft: Redmond, WA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- CheckPoint. Check Point Press Releases; CheckPoint: Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, 2023; Available online: https://www.checkpoint.com/press/2022/check-point-softwares-2022-security-report-global-cyber-pandemics-magnitude-revealed/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Arina, A. Cyber security strategies for higher education institutions. J. Eng. Sci. 2021, 23, 72–92. [Google Scholar]

- Astudillo, F.; Astudillo-Salinas, F.; Tello-Oquendo, L.; Sanchez, F.; Lopez-Fonseca, G. Information security management frameworks and strategies in higher education institutions: A Systematic Review. Ann. Telecommun. 2021, 76, 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- EDUCAUSE. Cybersecurity and Privacy Guide; EDUCAUSE: Louisville, CO, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.educause.edu/focus-areas-and-initiatives/policy-and-security/cybersecurity-program/resources/information-security-guide/security-policies#:~:text=The%202016%20EDUCAUSE%20Core%20Data%20Service%20found%20that,20%25%29%20CIS%20Critical%20Security (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Hash, J.; Wilson, M. NIST Special Publication 800-50: Building an Information Technology Security Awareness and Training Program; NIST Computer Security Resources Center: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, P.; Toth, P. NIST Especial Publication 800—16—A Role-Based Model for Federal Information Technology/Cybersecurity Training; NIST Computer Security Resources Center: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 27001; International Standard: Information Technology—Security Techniques—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. ISO/IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO/IEC 27002:2022; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Controls. Online Browsing Platform (OBP) n.d; ISO/IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso-iec:27002:ed-3:v2:en (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- CIS. CIS Critical Security Controls Version 8; CIS: East Greenbush, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA); Center for Diseases Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1996. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/php/resources/health-insurance-portability-and-accountability-act-of-1996-hipaa.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/hipaa.html (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- NIST. Information Technology Laboratory: Computer Security Resource Center; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/information (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Cawthra, J. Data Integrity: Identifying and Protecting Assets Against Ransomware and Other Destructive Events. Available online: https://www.nccoe.nist.gov/publication/1800-25/VolA/index.html (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- ISACA. Glossary; ISACA: Schaumburg, IL, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.isaca.org/resources/glossary (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- IBM. What Is a Cyberattack? IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.ibm.com/topics/cyber-attack (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Statista. PHISHING. In DIGITAL & TRENDS; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Threat Hunter Team. The Ransomware Threat Landscape: What to Expect in 2022; Symantec by Broadcom Software: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zadelhoff, M.V. The Biggest Cybersecurity Threats Are Inside Your Company. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 19, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Bahorski, Z.C.; Droujkova, M. Personal Computers; EBSCO Research Starters: Ipswich, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/computer-science/personal-computers (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Dobrow, S. Rise of the Internet and the World Wide Web; Salem Press Encyclopedia: Ipswich, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shillair, R.; Esteve-González, P.; Dutton, W.H.; Creese, S.; Nagyfejeo, E.; von Solms, B. Cybersecurity e Ucation, Awareness Raising, and Training Initiatives: National Level Evidence-Based Results, Challenges, and Promise; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Petrosyan, A. Number of Internet Users Worldwide from 2005 to 2022; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. U.S. and World Population Clock; United States Census Bureau: Suitland-Silver Hill, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wlosinski, L. The Benefits of Information Security and Privacy Awareness Training Programs. ISACA J. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Asch, E.; Ballou, J.; Weisbrod, B. Mission and Money: Understanding University; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Research Department. Revenue from Tuition and Fees of Degree-Granting Postsecondary Institutions in the United States from 2010/11 to 2019/20; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Research Department. Estimated Number of Universities Worldwide as of July 2021, by Country; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- El-Azar, D. 4 Trends That Will Shape the Future of Higher Education; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova, E. Enhancing the Organisational CULTURE related to Cyber Security during the University Digital Transformation. Inf. Secur. 2020, 40, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J.; Golden, D.; Nicholson, M. Reshaping the cybersecurity landscape; Deliotte Ingsight: Westlake, TX, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/financial-services/cybersecurity-maturity-financial-institutions-cyber-risk.html (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Clark, C.; Fishman, T. Elevating Cybersecurity on the Higher Education Leadership Agenda; Deloitte Insights: Westlake, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, J.; Kaplan, J.; Kazimierski, B.; Lewis, C.; Telford, K. Organizational Cyber Maturity: A Survey of Industries; McKinsey & Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlin, E. Cybersecurity and Privacy in the Future of Health; Deloitte: Westlake, TX, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/advisory/articles/data-privacy-and-cybersecurity-in-the-future-of-health.html (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Petrosyan, A. Percentage Change in the Cyber Security Budget Allocation in U.S. Healthcare Organizations from 2020 to 2021; Statistic: Suitland, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, T. What Is a Framework in Cybersecurity? (A Beginner’s Guide); Forbes: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2020; Available online: https://books.forbes.com/author-articles/what-is-a-framework-in-cybersecurity-a-beginners-guide/ (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Bhaskar, R. Better Cybersecurity Awareness Through Research. ISACA J. 2022, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Constantin, A. Information Security Management—Part of the Integrated Management System. Acta Univ. Cibiniensis 2015, 66, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- NIST. About NIST; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/about-nist (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- NIST. Cybersecurity Framework Components; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework/online-learning/cybersecurity-framework-components (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- NIST. Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- NIST. Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC. About ISO. n.d. Available online: https://www.iso.org/about-us.html (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- ISO/IEC 27002:2013; INTERNATIONAL STANDARD Information Technology—Security Techniques—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. ISO/IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/54533.html (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- SANS Institute. About SANS Institute; SANS Institute: Cleverdale, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.sans.org/about/?msc=main-nav (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- SANS. SANS Security Awareness Maturity Model TM; SANS: Cleverdale, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- CIS. CIS Critical Security Controls Version 8; CIS: East Greenbush, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.cisecurity.org/controls/v8?sc_camp=BB43A1FDB3874AABA535F539EDD34A19&utm_source=bing&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=bing_controls&msclkid=0df2e9b6556514dcbf8a8ca18af5b7dc (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- CIS. Download the CIS Critical Security Controls® v8; CIS: East Greenbush, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CIS. CIS Controls v8 Mappings to ISACA COBIT 19; CIS: East Greenbush, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Karam, M.; Khader, M.; Fares, H. Cybersecurity Awareness Framework for Academia. Information 2021, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin-Gabriel, B.; Hussain, N.Y.; Ige, A.B.; Adepoju, P.A.; Amoo, O.O.; Afolabi, A.I. Advancing zero trust architecture with AI and data science for enterprise cybersecurity frameworks. Open Access Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2021, 1, 047–055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abikoye, B.; Agorbia-Atta, C. Securing the Cloud: Advanced Solutions for Government Data Protection. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 23, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouças Filho, W.L. The Role of Zero Trust Architecture in Modern Cybersecurity: Integration with IAM and Emerging Technologies. Braz. J. Dev. 2025, 11, e76836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, H. Emerging Technologies Driving Zero Trust Maturity Across Industries. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2024, 6, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S.M.; Prybutok, V. Balancing privacy and progress: A review of privacy challenges, systemic oversight, and patient perceptions in AI-driven healthcare. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanaban, H. Privacy-preserving architectures for AI/ML applications: Methods, balances, and illustrations. J. Artif. Intell. Gen. Sci. (JAIGS) 2024, 3, 235–245. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Li, G.; Gai, K. Blockchain-based secure medical data management and disease prediction. In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM International Symposium on Blockchain and Secure Critical Infrastructure, Nagasaki, Japan, 30 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Daah, C.; Qureshi, A.; Awan, I.; Konur, S. Enhancing zero trust models in the financial industry through blockchain integration: A proposed framework. Electronics 2024, 13, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xia, C.; Lin, W.; Wang, T. PPBFL: A privacy protected blockchain-based federated learning model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.01204. [Google Scholar]

- Rückel, T.; Sedlmeir, J.; Hofmann, P. Fairness, integrity, and privacy in a scalable blockchain-based federated learning system. Comput. Netw. 2022, 202, 108621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Guan, J. Bio-Rollup: A new privacy protection solution for biometrics based on two-layer scalability-focused blockchain. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngoupayou Limbepe, Z.; Gai, K.; Yu, J. Blockchain-Based Privacy-Enhancing Federated Learning in Smart Healthcare: A Survey. Blockchains 2025, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Hajlaoui, N.; Touati, H.; Hadded, M.; Muhlethaler, P.; Boudjit, S. A Secure Medical Information Storage and Sharing Method Based on Multiblockchain Architecture; IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanmi, H.; Hajlaoui, N.; Touati, H.; Hadded, M.; Muhlethaler, P.; Boudjit, S. Blockchain-cloud integration: Comprehensive survey and open research issues. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2024, 36, e8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsohou, A.; Karyda, M.; Kokolakis, S. Analyzing the role of cognitive and cultural biases in the internalization of information security policies: Recommendations for information security awareness programs. Comput. Secur. 2015, 52, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, W.; Rivera, J.J.D.; Ahmed, K.T.; Muhammad, A.; Song, W.-C. Software Defined Perimeter Monitoring and Blockchain-Based Verification of Policy Mapping. In Proceedings of the 2022 23rd Asia-Pacific Network Operations and Management Symposium (APNOMS), Takamatsu, Japan, 28–30 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abou El Houda, Z.; Moudoud, H.; Khoukhi, L. Blockchain Meets O-RAN: A Decentralized Zero-Trust Framework for Secure and Resilient O-RAN in 6G and Beyond. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2024-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. Research Skills; The Essential Step-By-Step Guide on How to Do a Research Project; Kindle Edition: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, E.; Wang, T. Institutional Strategies for Cybersecurity in Higher Education Institutions. Information 2022, 13, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Usman, Z.; Asif, M.; Muhammad, N. The Power of Adkar Change Model in Innovative Technology Acceptance under the Moderating Effect of Culture and Open Innovation. LogForum 2021, 17, 485–502. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, J.; Jongbloed, B.; Salerno, C. Higher education and its communities: Interconnections, interdependencies and a research agenda. High. Educ. 2008, 56, 303–324. [Google Scholar]

- ISACA. COBIT an ISACA Framework; ISACA: Schaumburg, IL, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.isaca.org/resources/cobit (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Gür, G.; Gür, G.; Sutter, T.; Tellenbach, B. Don’t click: Towards an effective anti-phishing training. A comparative literature review. Hum.-Centric Comput. Inf. Sciences 2020, 10, 33. [Google Scholar]

| Aspect of Importance | For Individuals | For Institutions |

|---|---|---|

| Protection of Personal Data | Safeguards against identity theft and privacy violations. | Compliance with data protection regulations and laws. |

| Financial Security | Prevents financial losses due to fraud and cybercrime. | Avoids financial losses, legal fines, and reputational damage. |

| Online Reputation | Preserves trust and credibility in personal and professional spheres. | Avoids damage to reputation and the loss of customers and partners. |

| Privacy Preservation | Protects personal information and online privacy. | Maintains the privacy of customer and employee data. |

| Protection from Cyber Threats | Guards against malware, phishing, and ransomware attacks. | Mitigates the risk of cyberattacks and data breaches. |

| Data Access Control | Ensures control over personal data and who can access it. | Controls access to sensitive corporate information. |

| Preventing Data Loss | Prevents the loss of personal data and digital assets. | Safeguards intellectual property and sensitive data. |

| Business Continuity | Ensures the ability to access online services and resources. | Maintains business operations during cyber incidents. |

| Trust in Online Services | Enhances confidence in online services and transactions. | Builds trust among customers, clients, and partners. |

| Adherence to Regulations | Ensures compliance with data protection and privacy laws. | Avoids legal penalties and regulatory sanctions. |

| Protection from Insider Threats | Guards against accidental or intentional data leaks. | Prevents insider threats, data theft, and sabotage. |

| Preventing Disruptions | Minimizes disruptions due to cyberattacks and service outages. | Reduces downtime and financial losses from cyber incidents. |

| Intellectual Property | Protects personal creative work and inventions. | Safeguards proprietary information and trade secrets. |

| Group of Causes | Details | Example/Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Source of valuable data and intellectual property | Rich Data Stores | Student records, financial information, and research data. |

| Research and Intellectual Property | Valuable studies and innovation. | |

| Personal Information | Social Security numbers and credit card data. | |

| Financial incentives | Financial Resources | Ransomware attacks for financial gain. |

| Security vulnerabilities | Weaker Security Awareness | Diverse user base with varying security awareness. |

| Limited Resources for Cybersecurity | Budget and resource constraints. | |

| Open Networks | Collaborative and open network environments | |

| Attack methods | Credential Harvesting | Stealing login credentials for various services. |

| Botnets and Distributed Attacks | Compromising connected devices. | |

| Supply Chain Attacks | Targeting the broader supply chain. | |

| Nation-state interest | Nation-State Actors | Espionage, research access, and intelligence gathering. |

| Longer attack windows | Holidays and Vacations | Extended periods of low activity during breaks. |

| Feature | NIST NICE | ISO/IEC 27001 | ENISA Guidelines | CA&TF for HE (Proposed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Sector | General workforce | All organizations | Public/private sectors | Higher education-specific |

| Role-based Segmentation | Partial (job categories) | Not detailed | Limited | Explicit (students, faculty, staff, admin) |

| Training Content Customization | Moderate | Minimal | Moderate | High (based on user role and access level) |

| Adaptive Learning Paths | No | No | No | Yes (AI/ML suggested for future implementation) |

| Feedback Loop for Dynamic Threats | Not embedded | Not embedded | Basic | Yes (threat intelligence integration) |

| Decentralized Institution Readiness | Not addressed | Centralized control model | Not addressed | Yes (designed for distributed HE systems) |

| Integration of Emerging Technologies | Low | Low | Moderate | High (planned AI, blockchain-based protection) |

| Implementation Guidance | Structured | Highly formalized | Guideline-based | Roadmap with practice-oriented stages |

| Evaluation Mechanisms | Not defined | Requires audit | General recommendations | Simulation-based and survey feedback suggested |

| TIER | Risk Management Process | Integrated Risk Management Program | External Participation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Partial | Not formalized; reactive | Limited awareness Case-by-case implementation | Unaware of the cyber supply chain risks. |

| 2: Risk-Informed | Practices are approved but may not be established as policy | There is an awareness of the cybersecurity risk, but an approach to managing this risk has not been established | There is an awareness of the cyber supply chain risks but does not act consistently or formally upon those risks. |

| 3: Repeatable | Formally approved and expressed as policy | Personnel possess the knowledge and skills to perform their roles and responsibilities | There is an awareness of the cyber supply chain risks and formal mechanisms to communicate baseline requirements, governance structures, and policy implementation. |

| 4: Adaptative | Cybersecurity practices are based on previous and current cybersecurity activities, including lessons learned and predictive indicators | Cybersecurity risk management evolves from an awareness of previous activities and continuous awareness of activities on their systems and networks | It receives, generates, and reviews prioritized information that informs the continuous analysis of its risks as the threat and technology landscapes evolve. |

| Safeguard | Description | COBIT 19-Objective # | Management Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14. 1 | Establish and Maintain a Security Awareness Program | BAI08 | Managed Knowledge |

| 14. 2 | Train Workforce Members to Recognize Social Engineering Attacks | DSS05 | Managed Security Services |

| 14. 5 | Train Workforce Members on Causes of Unintentional Data Exposure | DSS06 | Managed Business Process Controls |

| 14. 9 | Conduct Role-Specific Security Awareness and Skills Training | APO01 | Managed IT Management Framework |

| Unmapped COBIT 19-Objective # | |||

| - | - | APO04 | Managed Innovation |

| - | - | MEA02 | Managed System of Internal Control |

| Area Representatives | Accountability and Contribution |

|---|---|

| Information Security |

|

| Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Center (CA&TC) |

|

| Information and Communication Technology Support (ICTC) |

|

| Faculty |

|

| Human Resources |

|

| Marketing and Communication |

|

| Finance |

|

| Student Center |

|

| Department/Area | Specific Role | Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing and Communications | Creates awareness and promotes the Information Security Culture Program. |

|

| Cybersecurity Awareness and Training Program Team | Manages the cybersecurity awareness and training aspects of the program, ensuring that it aligns with the ADKAR model stages. |

|

| Directors, Executives, and Leaders | Drives the Information Security Culture within the institution. |

|

| Student, Faculty, and Complementary Activities Leaders | Leaders within the academic and administrative departments serve as champions for information security and act as role models. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Armas, R.; Taherdoost, H. Building a Cybersecurity Culture in Higher Education: Proposing a Cybersecurity Awareness Paradigm. Information 2025, 16, 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050336

Armas R, Taherdoost H. Building a Cybersecurity Culture in Higher Education: Proposing a Cybersecurity Awareness Paradigm. Information. 2025; 16(5):336. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050336

Chicago/Turabian StyleArmas, Reismary, and Hamed Taherdoost. 2025. "Building a Cybersecurity Culture in Higher Education: Proposing a Cybersecurity Awareness Paradigm" Information 16, no. 5: 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050336

APA StyleArmas, R., & Taherdoost, H. (2025). Building a Cybersecurity Culture in Higher Education: Proposing a Cybersecurity Awareness Paradigm. Information, 16(5), 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050336