Abstract

Cultural heritage is a precious treasure left to mankind by history. With the development of the times and the improvement of people’s education, more and more people are becoming aware of the importance of protecting cultural heritage. Chinese porcelain inlay is a type of architectural decoration born out of the specific historical, geographical, and cultural conditions of Fujian and Guangdong, and was included in the second batch of The National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of China published in 2008 and the third batch of The National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of China—Expanded Projects in 2011. It represents an important part of the complex traditional culture of Fujian and Guangdong, acting as the essence of national culture, a symbol of national wisdom, and the refinement of national spirit. Using targeted analysis and making changes based on negative reviews, organizations that protect cultural heritage can improve their actions and find new ways to spread cultural heritage. The craft of Chinese porcelain inlay is used as an example in this paper. It combines Python Octopus crawler technology, data analysis, and sentiment analysis methods to perform a cognitive social media visualization analysis of Chinese porcelain inlay, which is a form of national intangible cultural heritage in China. Then, by looking at network text data from social media, it seeks to find out how the Chinese porcelain inlay culture is passed down, what its main traits are, and how people feel about it. Finally, this study summarizes the public’s understanding of inlay porcelain and proposes strategies to promote its future development and dissemination. This study found that (1) as a form of national intangible cultural heritage in China and a unique traditional architectural decoration craft, Chinese porcelain inlay has widely recognized cultural and artistic value. (2) The emotional evaluation of Chinese porcelain inlay is mainly positive (73 and 60.76%), while negative evaluations account for 12.62 and 20.79% of responses, mainly reflected in regret regarding the gradual disappearance of old buildings, the lament that Chinese porcelain inlay is highly regional and difficult to popularize, the regret that the individual has not visited locations with Chinese porcelain inlay, a feeling of helplessness with regard to inconvenient transportation links to these places, and discontent with the prohibitively high prices of Chinese porcelain inlay products. These findings offer valuable guidance for the future dissemination and development of Chinese porcelain inlay as a form of intangible cultural heritage. (3) The LDA topic model is used to divide the perception of Chinese porcelain inlay into nine major themes: arts and crafts, leisure and entertainment, cultural travel, online appreciation, heritage protection, dissemination scope, prayer and blessing, inheritance and innovation, and collection and research. This also provides a reference for the future direction of the inheritance of Chinese porcelain inlay cultural heritage.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

“Intangible cultural heritage” includes social practices; conceptual expressions; forms of expression; knowledge, skills, and related tools; objects; handicrafts; and cultural sites that communities, groups, and sometimes individuals see as part of their cultural heritage [1]. The Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage was adopted by UNESCO on 17 October 2003 [2]. Although the concept of “intangible cultural heritage” emerged relatively late, it exists in every corner of our lives and is closely related to the development of human society. More and more experts and scholars from different fields have been studying how to protect “intangible cultural heritage” since the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. They have started to look at the inheritance and protection of traditional handicrafts from the point of view of “intangible cultural heritage” [1]. China has a long history of protecting intangible cultural heritage thanks to its 5000-year-old civilization [3]. The development of disciplines such as archeology, cultural relics, folk art, and folklore has made outstanding contributions to enriching China’s complex traditional culture and has laid the foundations for the development and protection of China’s cultural heritage [4,5]. The Book of Songs, as China’s first collection of poetry, collects and organizes a large number of folk songs, providing proof of China’s protection of folk culture and folk culture [6]. The concept of “cultural relics” appeared as early as in Zuo Zhuan [7]. The Archeological Map by Lü Dalin (1092) in the Northern Song Dynasty proves that the term “archeology” has existed since ancient times [8]. As a precious traditional architectural handicraft with a long history, the art of inlaid porcelain was included in the second batch of The National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of China in 2008 and in the third batch of The National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of China—Expanded Projects in 2011.

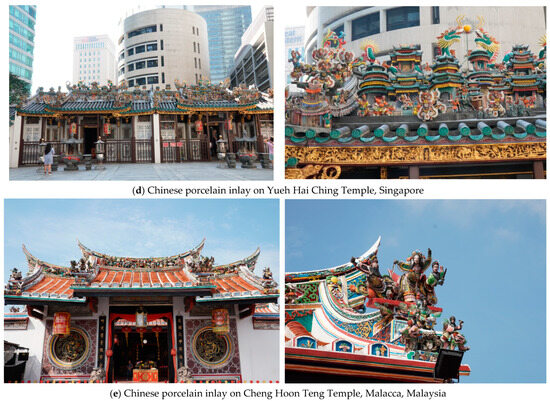

Porcelain inlay is a unique traditional architectural decoration craft from China’s Fujian and Guangdong provinces [9,10]. Its history can be traced back to the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty. It reached its peak around 1900 and became an important part of ancestral halls, temples, and other buildings in Fujian and Guangdong [11]. It is widely distributed in the southeast corner of China and overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. The “inlay” in Chinese porcelain inlay means embedding and inlaying. The craftsmanship of inlaying is what gives Chinese porcelain inlay its name. Chinese porcelain inlay craftsmen use porcelain materials with various glazes and lusters through cutting, hammering, inlaying, bonding, and stacking to form traditional architectural decorations or craft ornaments with flat, floating, or three-dimensional inlay effects, such as figures, flowers, and birds, insects and fish, landscapes, and animals.

As a traditional folk craft, Chinese porcelain inlay has been in an awkward position since its inception. Refined scholars find it vulgar, while common people admire its luxury. The cultural elites within the “great tradition” did not place it at the level of art, and the common people within the “small tradition” did not take it seriously either. Chinese porcelain inlay has been ignored for a long time and was only spread among a small number of people and regions, with very few documentary materials handed down. As a traditional handicraft, Chinese porcelain inlay mostly adopts the family system and the master–apprentice system [12]. The teaching mode is mainly oral and hand-to-hand teaching. The relevant process and production techniques are extremely complicated, but they are mostly passed down orally, and there is no written record handed down from generation to generation.

The historical material that clearly records the appearance of Chinese porcelain inlay is Guangdong Arts and Crafts Historical Materials, compiled by Lin Mingti in 1988 [13]. This book argues that Chinese porcelain inlay can be traced back to the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty (1573–1620) and flourished in the Qing Dynasty [14]. The Ming Dynasty was the period of the formation and development of the porcelain inlay craft in the traditional architectural decoration of Fujian and Guangdong. The Chinese porcelain inlay craft of this period integrated architectural skills, sculpture, and painting, showing distinct regional characteristics. The development of Chinese porcelain inlay has generally gone through the processes of origin, growth, decline, and reappearance, which to a certain extent also reflects the changes in traditional crafts in social culture. As an important part of social culture, the historical evolution and cultural inheritance of Chinese porcelain inlay culture are deeply affected by social and cultural changes, as well as self-discipline changes. The “Maritime Silk Road” developed rapidly during the Ming Dynasty and had a profound impact. The porcelain industry flourished as the economies of Fujian and Guangdong rapidly developed [15]. The contact, exchange, and dissemination of diverse cultures in different regions, such as the ancient Yue culture, the Central Plains culture, overseas cultures, and local culture, promoted the emergence of Chinese porcelain inlay art and led to its leapfrog development. With the development of society, traditional architectural decoration art was recognized by the aristocracy, and the social status of craftsmen was generally improved, which ignited their creative enthusiasm. The emergence of the “fighting art” competition mechanism also mobilized the enthusiasm of craftsmen, for a time making Chinese porcelain inlay art unparalleled in its craftmanship and quality. However, specific historical and political environments such as wars and the Cultural Revolution dealt a heavy blow to the flourishing Chinese porcelain inlay industry. The popularity of Chinese porcelain inlay art experienced a significant downturn, and its inheritance and development became difficult. With the founding of New China and the new era of reform and opening, Chinese porcelain inlay art began to emerge as a form of national intangible cultural heritage and became known to more people. The acceleration of the industrialization process also had an impact on the development of traditional architectural decoration crafts in Fujian and Guangdong. More and more Chinese porcelain inlay craftsmen are choosing to create exquisite and inexpensive porcelain pieces, while more and more young people are choosing to leave the industry. The development of porcelain inlay art has reached a bottleneck, and the inheritance of craftsmanship has gradually declined. The rise of the creative cultural industry brought hope for traditional crafts. Craftsmen and relevant scholars have begun to seek better material carriers and means of communication to “let the Chinese porcelain inlay in the sky take root”. People’s creativity and innovation will further promote cultural changes. The proposal of the “Belt and Road” initiative has brought greater opportunities and challenges to the development of Chinese porcelain inlay.

1.2. Research Objects: Chinese Porcelain Inlay

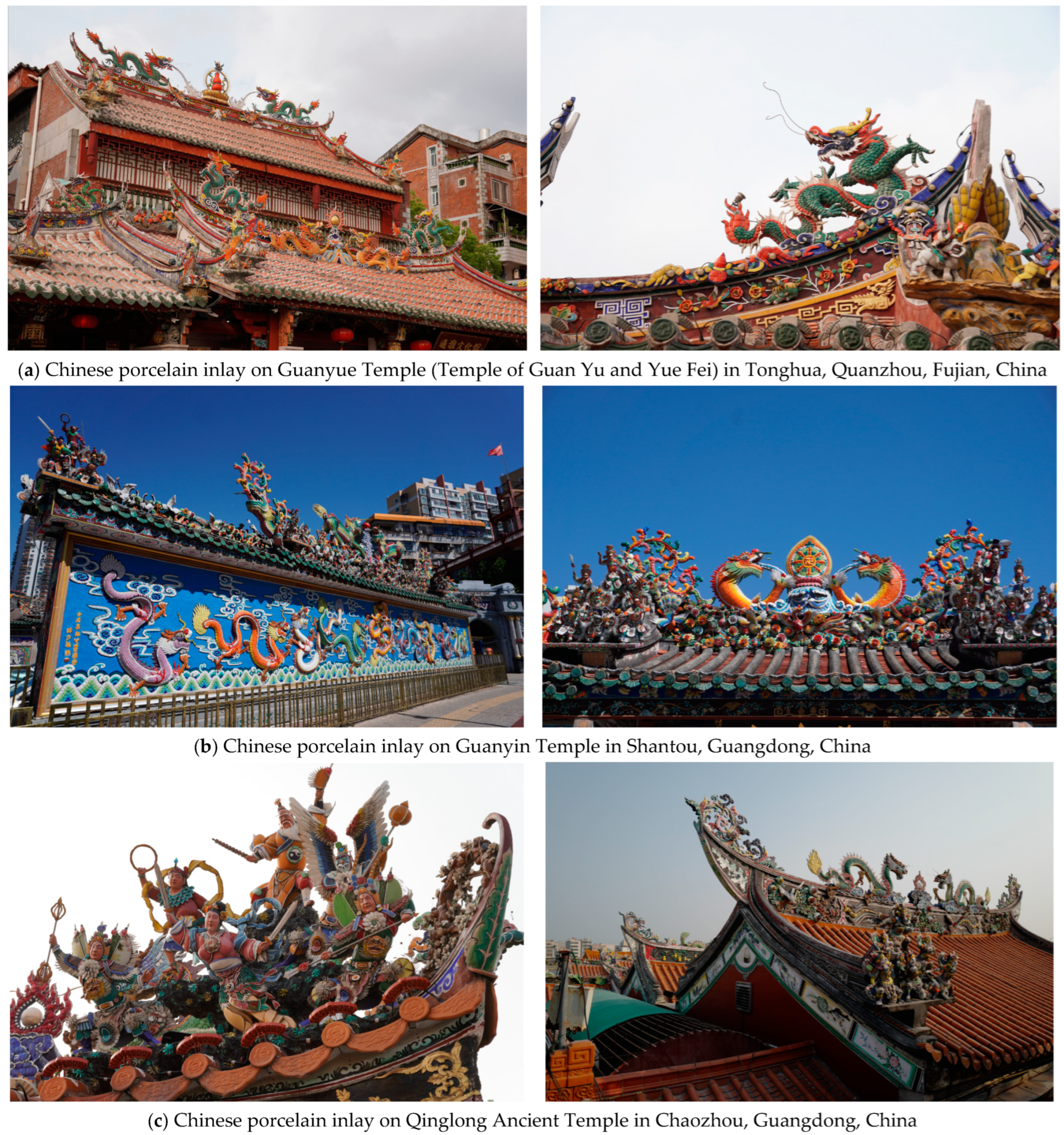

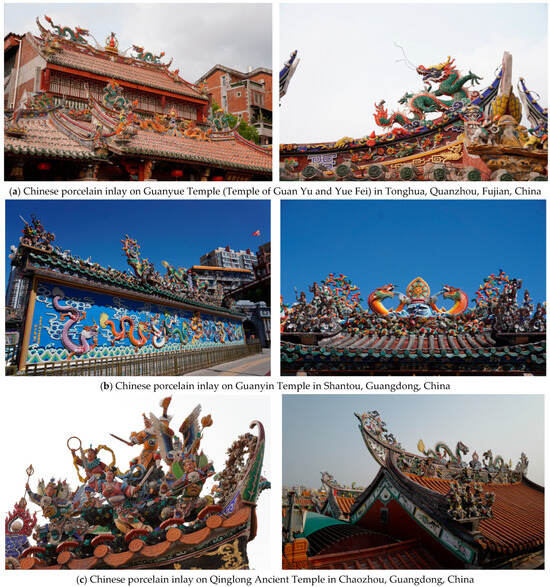

Chinese porcelain inlay works exhibit a clean and bright appearance, feature colorful and complex colors, and remain intact even after weathering. They are mostly used on the ridges and corners of traditional buildings; some are also located on screen walls [16]. The production process is roughly divided into three steps: first, iron wire, tiles, etc., are used to make the skeleton of the Chinese porcelain inlay; then, grass root ash is used to shape the skeleton to form a base; and finally, according to the different shapes and required colors, porcelain pieces of various shapes are cut out and embedded into the base. It is sometimes necessary to draw lines on the porcelain pieces to simulate the folds of people’s clothes, etc. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chinese porcelain inlay on different buildings (image source: photographed by the authors).

Following the inclusion of Chinese porcelain inlay on The National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of China in 2008, China has increasingly prioritized the development of this art form, leading to its growing popularity. As people’s living standards have improved and consumption modes have changed, Chinese porcelain inlay craftsmen have developed innovations in the artistic form and content of inlay porcelain [17]. They have created inlaid porcelain hanging screens and ornaments, aiming to “let the Chinese porcelain inlay in the sky take root”, ushering in a new era of development. Through field investigations, the researchers learned that currently, local craftsmen take the inheritance and dissemination of Chinese porcelain inlay culture as their main goal; establish Chinese porcelain inlay museums; participate in various exhibitions and fairs; invite students to participate in Chinese porcelain inlay “intangible cultural heritage” courses; actively encourage apprentices, Chinese porcelain inlay enthusiasts, and poor households to learn Chinese porcelain inlay craftsmanship; combine “poverty alleviation” with “intellectual support”; increase the income of poor households; and also enable inlay craftsmanship to be passed on in a “living state”. Local governments are also committed to building intangible cultural heritage bases, establishing relevant museums, and conducting online training courses in order to promote the development of Chinese porcelain inlay and enhance people’s awareness of it.

The selection of Chinese porcelain inlay as the subject of this study was based on several factors. It plays a vital role in embodying the craftsmanship of traditional craftsmen, displaying China’s intricate traditional culture, promoting exchanges and mutual learning between Chinese and foreign civilizations, and promoting cultural identity and understanding. As a local architectural decoration craft, Chinese porcelain inlay has attracted the attention of numerous individuals. These concerns and evaluations provide researchers with a significant amount of valuable data, being conducive to the further development of Chinese porcelain inlay.

1.3. Literature Review

Compared with tangible cultural heritage, intangible cultural heritage is mainly a kind of culture that depends on individuals and is passed down from mouth to mouth. Cultural heritage protection emphasizes dynamic protection, with the protection of people and skills being the main focus of intangible cultural heritage protection. In 1950, Japan promulgated the Cultural Property Protection Law, which for the first time stipulated the scope of “intangible cultural property” in the form of law [18]. In 1982, UNESCO established the “Special Division for Intangible Cultural Heritage” [19]. In 1997, UNESCO proposed the “Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity” announcement system based on the Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. It was signed in 2003 and was called the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. It explained what “intangible cultural heritage” meant and suggested that countries make and improve laws and rules to assist in protecting it [20]. China issued the Regulations on the Protection of Traditional Arts and Crafts in 1997, joined the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004, and announced the first batch of national “intangible cultural heritage” lists in 2006. China has been actively protecting its intangible cultural heritage for the past two decades. Many scholars have published works on intangible cultural heritage, such as Xiang Yunju’s (2006) World Intangible Cultural Heritage [21], Yuan Li and Gu Jun’s (2014) Intangible Cultural Heritage Studies, Wang Wenxuan’s (2013) Introduction to Intangible Cultural Heritage, Ma Guoqing and Zhu Wei’s (2018) Cultural Anthropology and Intangible Cultural Heritage, etc.

To help protect and share intangible cultural heritage, Chen Dong (2009) brought up the question of the “originality” of China’s traditional architectural craft heritage by looking at what makes intangible cultural heritage unique [22]. Taking large woodcraft as an example, he proposed an analysis method of originality. Li Xinjian (2014) recorded, sorted, analyzed, and compared traditional architectural skills in various parts of northern Jiangsu based on a large number of field investigations and interviews with craftsmen [23]. Fang Lili (2015) used Jingdezhen as a case study and looked at the three stages of its handicraft revival [24]. She also looked at how Jingdezhen’s traditional handicraft resources changed over time and how traditional culture was reorganized and rebuilt in the city. She concluded that traditional handicrafts, which are a form of intangible cultural heritage, have not gone away and are instead rebuilding society. In 2018, Ou Junyong and Wen Jianqin looked at how to pass on and protect Chaoshan traditional handicraft skills from the point of view of craftsman spirit in the appendix of “Research on Chaoshan Inlaid Porcelain Crafts” [25]. They used “Internet +” to create a new way to show and sell crafts and came up with new ways for traditional crafts to live on or change. The current “intangible cultural heritage fever” was looked at and summed up by Chen Anying (2019). He achieved this by looking at the inheritance and innovation of intangible cultural heritage, the deep integration of “intangible cultural heritage” protection with the local economy and ethnic minority culture, the “going out” of “intangible cultural heritage” culture, and building cultural confidence to shape a cultural power [26]. When Feifeng Zhong (2020) discussed the creative transformation and innovative development of traditional architecture in the Lingnan region, he referred to the raw materials and crafts of inlaid porcelain as well as other forms of intangible cultural heritage. He also provided suggestions on how to use new materials to bring out the charm of traditional buildings with inlaid porcelain sections [27]. After explaining what “systematic protection” means in this day and age, Min Xiaolei and Ji Tie (2023) discussed why cluster analysis and hierarchical construction of intangible cultural heritage elements are important and needed [28]. They also looked at how the innovation ecology of intangible cultural heritage is changing in the digital age.

The use of digital methods to analyze social media is an emerging and thriving approach. Scholars believe that text, as a form of data that is easier to collect and search through than images, plays an important role in social media analysis [29]. Scholars can provide a clear overview of the research field through established taxonomies, explore the design space and identify research trends, and discuss challenges and open issues for future research [30]. However, after realizing the potential of data mining and analysis, many platform providers have begun to restrict free access to such data, which has caused considerable challenges for researchers. Felt, M., called for combining key social media data analysis with traditional qualitative methods to cope with the evolving “data gold rush” [31]. Ghani, N. A. et al. discussed the application of social media big data analysis based on the latest technologies, methods, and quality attributes of research [32]. Social media data have a wide range of applications and can help researchers to provide targeted solutions to problems based on understanding current facts. An interactive visual analysis system can, for instance, analyze geo-tagged social media trajectory data to delve into the semantics of movement, encompassing movement patterns, frequent access sequences, and keyword descriptions [33]. Mulyani, Y. P. et al. used topic modeling and sentiment analysis of mainstream and social media data to capture public discussions and opinions on photovoltaics and residential photovoltaic adoption in Indonesia [34].

With the continuous development of the Internet, more and more users can learn about cultural heritage from social media, enabling them to come into contact with and even protect cultural heritage. Some scholars have proposed that archeologists and cultural heritage experts can use social media as a new source of information to monitor and record cultural heritage sites located in inaccessible areas due to conflicts, difficult terrain, or natural disasters [35]. Some scholars also provide effective opinions and suggestions to government agencies or relevant researchers by studying tourists’ experiences of cultural heritage sites and related cultural and creative products on social media to improve user experience [36,37]. Alternatively, they utilize social media platforms to uncover the interplay between digital and physical heritage preservation [38]. In terms of intangible cultural heritage, some scholars have also used content analysis to explore the cognitive images of intangible cultural heritage tourism, thereby promoting the industrialization of intangible cultural heritage tourism [39].

Through the above literature, we know that in today’s society, the protection of intangible cultural heritage is increasingly valued, and more methods are needed to conduct more in-depth academic research from more perspectives. Using social media analysis to study cultural heritage, especially intangible cultural heritage, is a good entry point. Therefore, the study of how people think about Chinese porcelain inlay through social media visualization analysis is an important and urgent task that can serve as a model for future research into similar types of intangible cultural heritage.

1.4. Problem Statement and Objectives

With the development of society and the popularization of the Internet, more and more people have learned about Chinese porcelain inlay as a form of intangible cultural heritage through social media platforms such as Xiaohongshu (also known as RedNote) and Sina Weibo and have developed a strong interest in it. Weibo is a broadcast-style social media platform founded in 2009 that uses multimedia forms such as text, pictures, and videos to achieve instant information sharing and interactive communication. Xiaohongshu is a lifestyle platform for young people founded in 2013. Users can record and share their lifestyles through pictures, texts, short videos, etc., and interact with others. Currently, Weibo and Xiaohongshu have become the main communication tools for young people in China [40]. They have a huge user base in China and are very popular social media platforms. By the end of 2023, Weibo had 605 million active users [41], while by the end of 2022, Xiaohongshu had 261 million monthly active users. These two platforms generate a large number of posts and comments every day, providing real data information for our research. These rich data sources are essential for cultural heritage craftsmen and researchers. For instance, the feedback from netizens on Chinese porcelain inlay aids in the development of cultural travel routes, the creation of cultural and creative products, and the launch of online courses, all of which significantly influence the future dissemination of Chinese porcelain inlay art [42]. Analyzing this feedback can enable Chinese porcelain inlay practitioners to better understand people’s willingness and expectations regarding intangible cultural heritage inheritance, promote infrastructure construction, improve the quality of Chinese porcelain inlay-related products and services, and expand the influence of Chinese porcelain inlay as a form of intangible cultural heritage [43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Furthermore, positive comments, being the most effective form of publicity, can draw more attention to this cultural heritage and infuse it with new vitality. Comments on the news can encourage city leaders and cultural heritage practitioners to check for omissions and formulate targeted solutions based on the comments, thereby promoting the healthy dissemination of Chinese porcelain inlay, a form of intangible cultural heritage. In summary, this study concentrates on Chinese porcelain inlay, a form of intangible cultural heritage, and investigates three primary questions: (1) what are the most recognized factors of Chinese porcelain inlay? (2) What are the main components of positive and negative evaluations of Chinese porcelain inlay? (3) What are the categories of themes relating to Chinese porcelain inlay, as seen from the perspective of netizens?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Input Data and Preprocessing

This study combined Python Octopus crawler technology, data analysis, and sentiment analysis methods to understand the status of cognition and inheritance of Chinese porcelain inlay culture, its core characteristics, and public sentiment and attitude. Sina Weibo (https://weibo.com/, accessed on 20 December 2023) is undoubtedly one of the most popular social media platforms in China for information dissemination, social interaction, and public opinion influence [50,51]. It has become a dominant force and has profoundly shaped social dynamics and communication paradigms. On the other hand, Xiaohongshu (RedNote) (https://www.xiaohongshu.com/explore, accessed on 20 December 2023) is a popular UGC (user-generated content) platform in China [52]. Users upload photos, videos, and text to share their shopping, travel, and daily life experiences and interact with other users, meeting users’ needs in terms of product information, emotions, etc. These two platforms are undoubtedly excellent choices for expanding public awareness of cultural heritage.

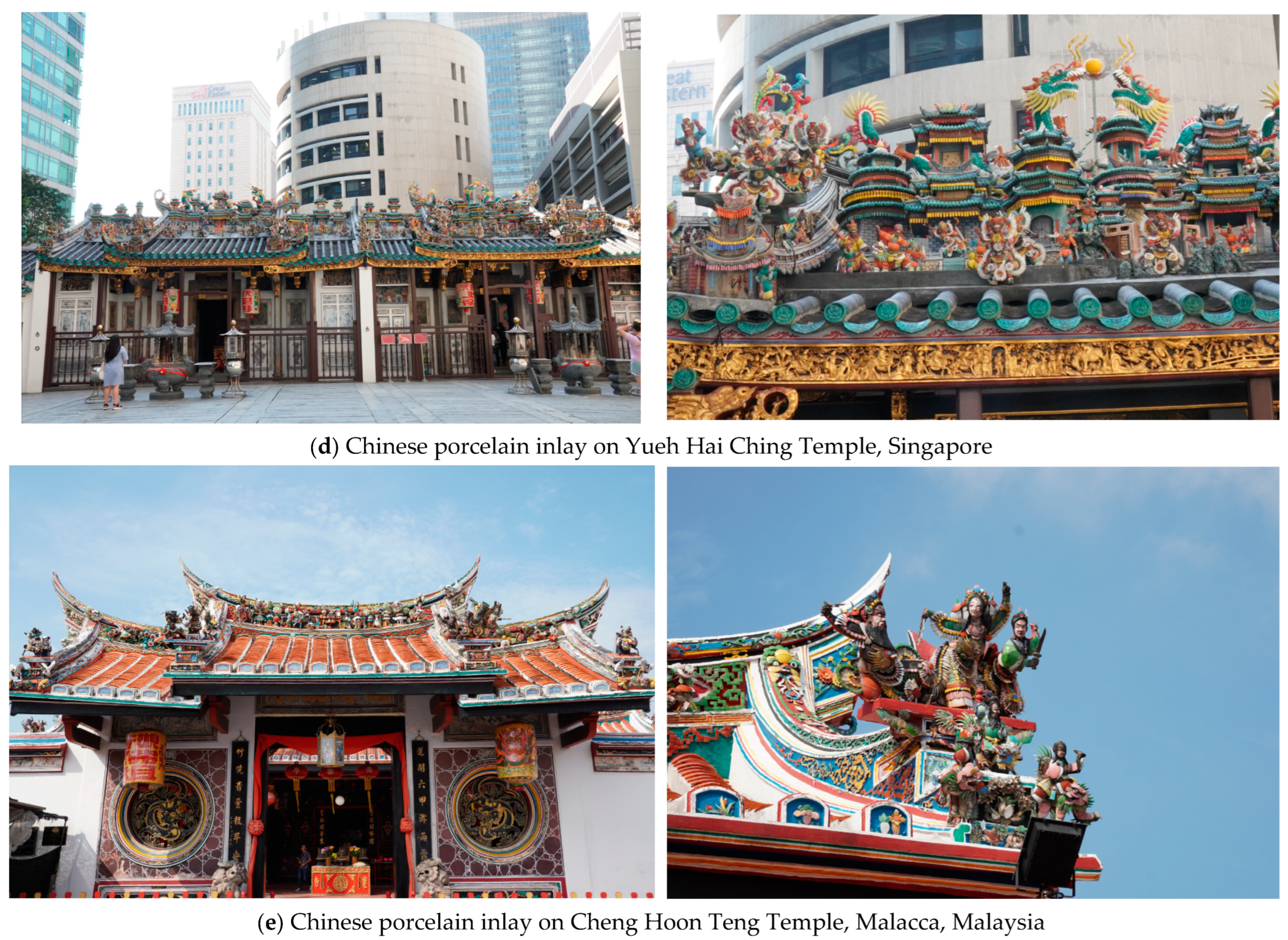

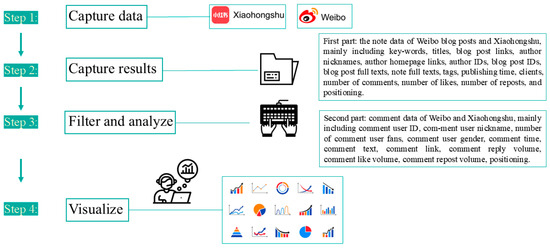

The data sources used in this study were Sina Weibo and Xiaohongshu, two major social media platforms. The researchers collected blog posts and comment data from these two platforms from January 2020 to December 2023. We roughly divided the results of data collection into two parts (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Research process in this study (image source: drawn by the authors).

The first part of the database comprised the note data of Weibo blog posts and Xiaohongshu posts: a total of 2735 Weibo posts and 238 Xiaohongshu posts were collected, mainly including keywords, titles, blog post links, author nicknames, author homepage links, author IDs, blog post IDs, full texts of blog posts, full texts of notes, tags, publishing time, clients, number of comments, number of likes, number of reposts, and positioning. These data show how people on both platforms who know about and want to promote Chinese porcelain inlay communicate about it. They also show where current users are placing most of their efforts and where they need to improve when it comes to spreading information about this form of cultural heritage. This part of the database was mostly used in Section 3.1’s word frequency analysis and Section 3.2’s network semantic analysis. The second part was the comment data from Weibo and Xiaohongshu: a total of 7771 Weibo posts and 1361 Xiaohongshu posts were collected, mainly including comment user ID, comment user nickname, number of comment user fans, comment user gender, comment time, comment text, comment link, comment reply to volume, comment like volume, comment repost volume, positioning, etc. Instead of only showing the positive opinions and enthusiasm of users who want to actively promote Chinese porcelain inlay, this part of the database can intuitively show how all users really feel and what they are willing to do. This includes users who have never seen Chinese porcelain inlay before and users who want to learn more about it. This was more conducive to the fairness and impartiality of the data results and was mainly used for the emotional image analysis in Section 3.3 and the LDA topic model analysis in Section 3.4.

The data analysis was conducted through three steps: first, we manually filtered out irrelevant data that were not related to the keyword “Chinese porcelain inlay” (as a form of national intangible cultural heritage), such as “dental inlay technology”, “inlaid porcelain plate painting”, “tea set”, “inlaid ceramic tile”, “pastel inlaid porcelain tin can”, etc. These terms are mainly related to porcelain products in the Chinese context, but are beyond the scope of this study. This paper screened out 18 pieces of irrelevant data from the 2735 obtained Weibo posts, thus utilizing a total of 2717 posts. Among the 238 Xiaohongshu posts, 1 irrelevant post was screened out, and a total of 237 posts were utilized. Among the 7771 Weibo comments, 90 pieces of irrelevant data were screened out, and a total of 7681 comments were utilized. Among the 1361 Xiaohongshu comments, 11 pieces of irrelevant data were screened out, and a total of 1350 comments were utilized. Then, we utilized Python to perform statistical analysis on the vast amount of collected data, extract valuable information, conduct detailed research, and summarize the data. Finally, we created a visual chart to comprehend the current cultural perception and cultural inheritance status of Chinese porcelain inlay on mainstream social media. Meanwhile, we conducted sentiment analysis on user comments on social media, counted both positive and negative feedback, summarized the public’s emotional inclination towards Chinese porcelain inlay, and explored directions for the further development of inlaid porcelain.

2.2. Analytical Methods

WFA (Word Frequency Analysis) is a statistical text analysis method that reveals the key content or theme of a text by calculating the frequency of occurrence of words in the text. WFA is one of the basic technologies in text mining and natural language processing, and is often used for tasks such as text classification, keyword extraction, and topic analysis. Common libraries include NLTK (Natural Language Toolkit), spaCy, Scikit-learn, gensim, and collections.Counter. Technologies include Tokenization, Stop Words Removal, Stemming, Lemmatization, n-gram analysis, TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency), and visualization.

Sentiment analysis is a branch of text classification. We used it to identify the sentiment tendency of text, generally dividing it into three types: positive, negative, and neutral. This process output the corresponding sentiment score (0–1) [53]. This was a crucial step in analyzing the current state of the Chinese porcelain inlay cultural inheritance on social media. The text presents a more positive attitude when the sentiment tendency approaches 1 and a more negative attitude when the sentiment tendency approaches 0. Its commonly used libraries include NLTK (Natural Language Toolkit), TextBlob, VADER (Valence Aware Dictionary and sEntiment Reasoner), and Hugging Face Transformers, and its technologies include methods based on dictionary, machine learning, and deep learning.

The LDA (latent Dirichlet allocation) topic model is a probabilistic generation model for extracting topics from text data. The LDA topic model, which mines potential topics in text, comprises three layers: documents, topics, and vocabulary [54]. Its commonly used libraries include Gensim, Scikit-learn, and PyLDAvis, and its techniques include text preprocessing, topic number selection, and model visualization.

3. Results

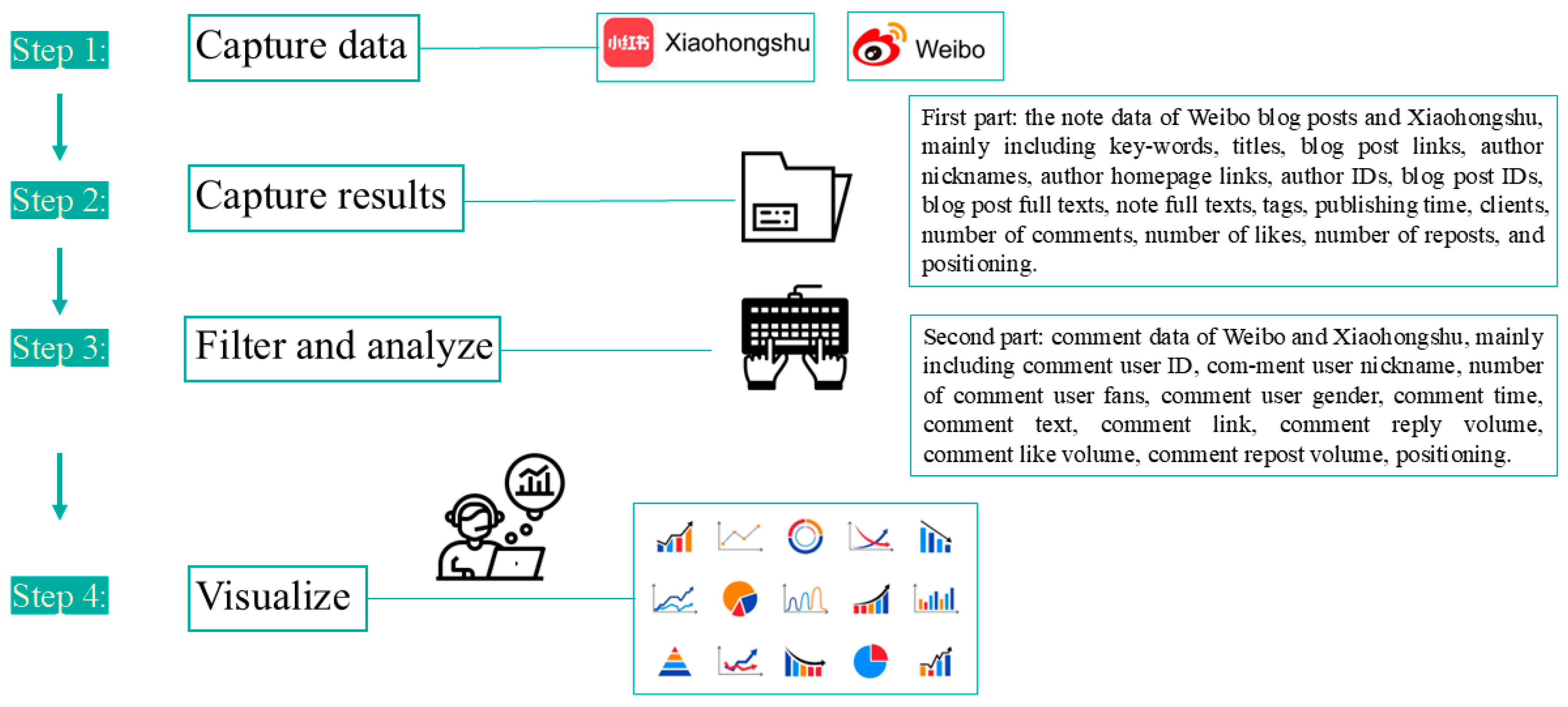

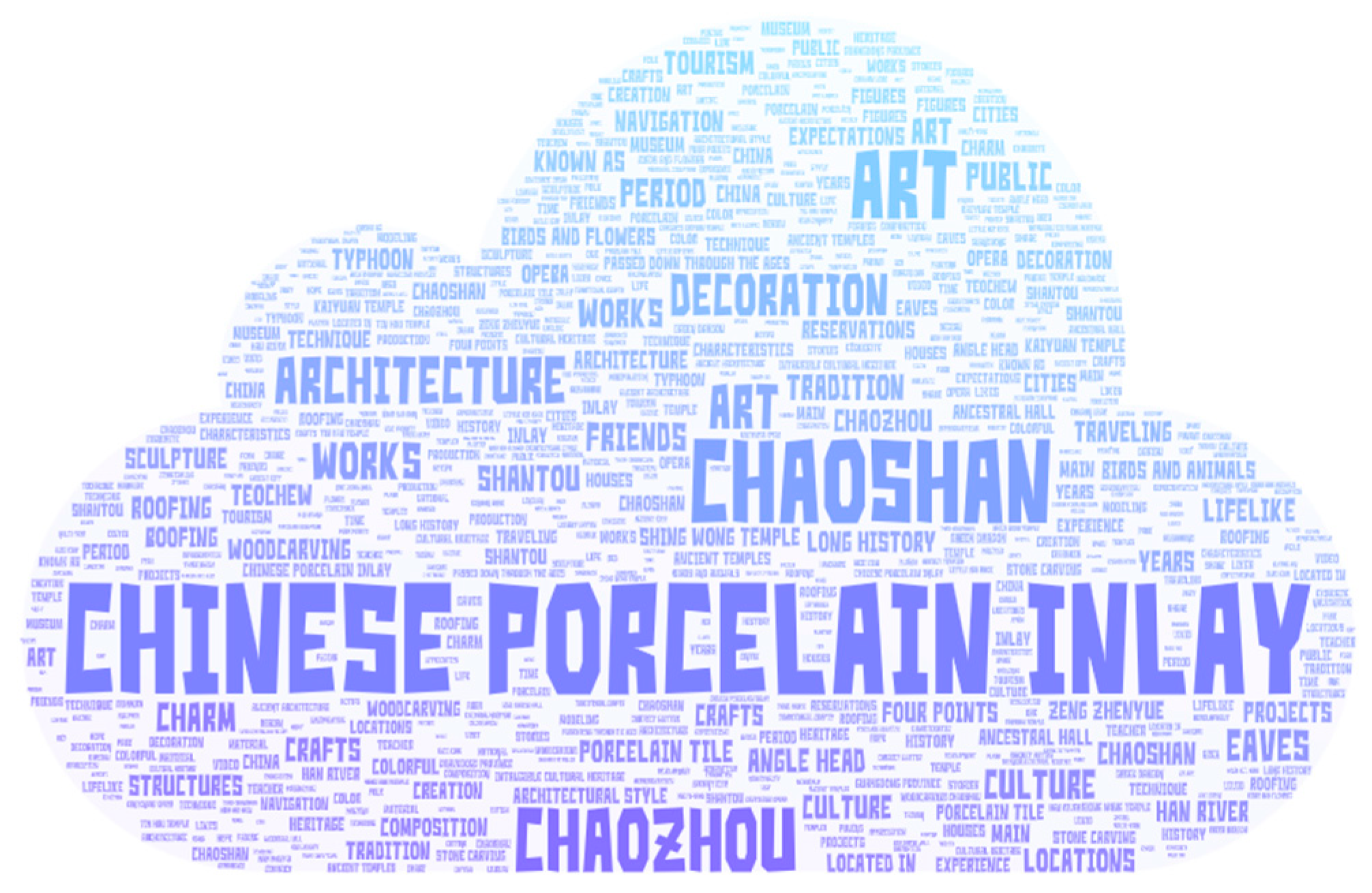

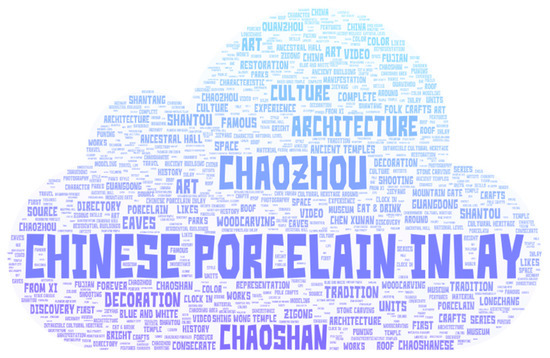

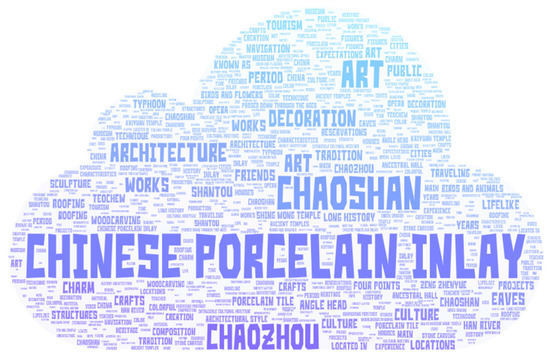

3.1. Word Frequency Analysis and Word Cloud Diagram

Commonly used tools in text analysis include word frequency analysis and word cloud diagrams. Word frequency analysis refers to counting the frequency of occurrence of words in text. We collected 2717 valid Weibo blog posts. We conducted word frequency analysis on the obtained blog posts using high-frequency words from Weibo blog posts, such as “Chinese porcelain inlay”. Table 1 presents the results. “Chinese porcelain inlay” had the highest frequency, appearing 3408 times; “Chaozhou” was second, appearing 2598 times, and “Chaoshan” appeared 1926 times. This shows that in the online text data that we collected, users’ knowledge of inlaid porcelain is mostly concentrated in the “Chaoshan” area (including Chaozhou, Shantou, and Jieyang). As a national intangible cultural heritage site, the inlaid porcelain works and craftsmen in this area are also more frequently mentioned on the Internet. “Architecture”, “culture”, “decoration”, “art”, “tradition”, and other words are also frequently mentioned, indicating that in our data sample, Chinese porcelain inlay, as a unique traditional architectural decoration craft, is highly recognized for its cultural and artistic attributes, reflecting users’ interest in and demand for Chinese porcelain inlay. To ensure the reliability of media data, this paper also collected 238 valid pieces of data from Xiaohongshu notes. Table 2 displays the results. The high-frequency words in these notes are basically consistent with the high-frequency words in Weibo posts, and the above words all ranked in the top nine.

Table 1.

High-frequency vocabulary list in Sina Weibo blog posts (top 60).

Table 2.

High-frequency vocabulary list in Xiaohongshu blog posts (top 9).

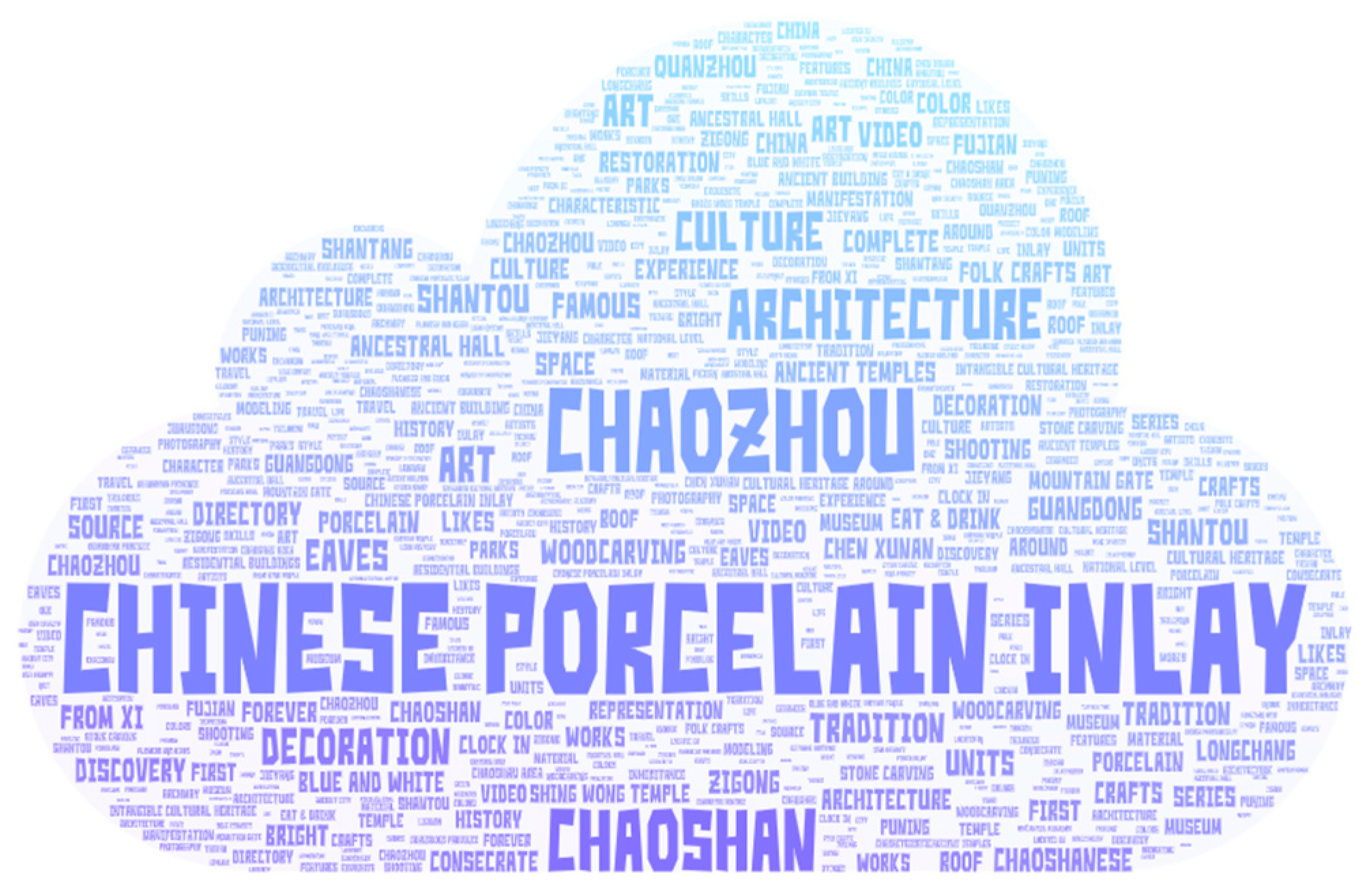

A word cloud graph visually presents the results of word frequency analysis in the form of words. The size of a word is proportional to its frequency of occurrence. Using the jieba Chinese word segmentation library, the wordcloud library, the matplotlib drawing library, etc., we drew the corresponding word cloud graphs (Figure 3 and Figure 4) based on the high-frequency vocabulary lists of Weibo posts and Xiaohongshu notes.

Figure 3.

Sina Weibo blog word cloud (image source: drawn by the authors).

Figure 4.

Xiaohongshu word cloud (image source: drawn by the authors).

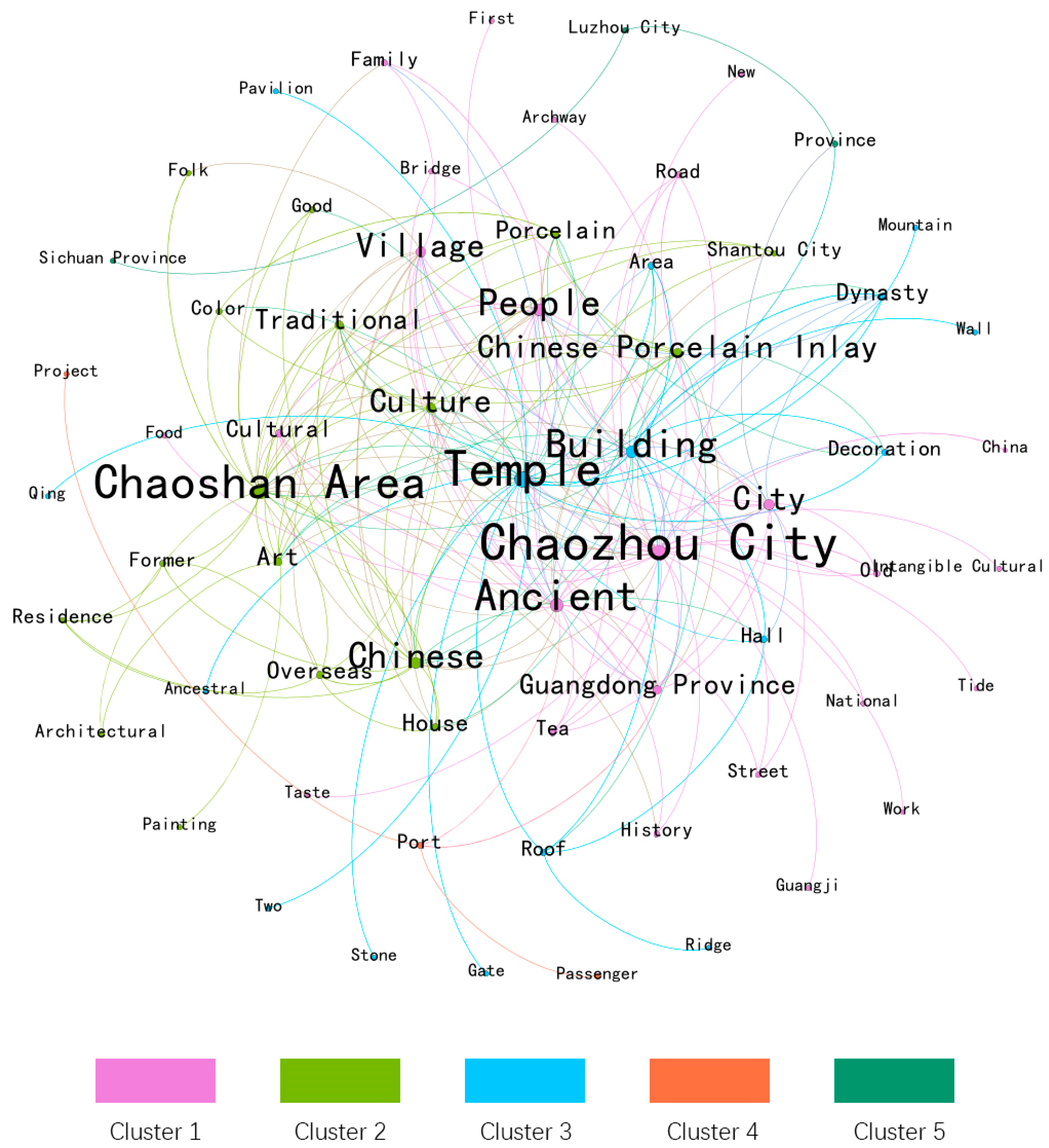

3.2. Semantic Network Analysis

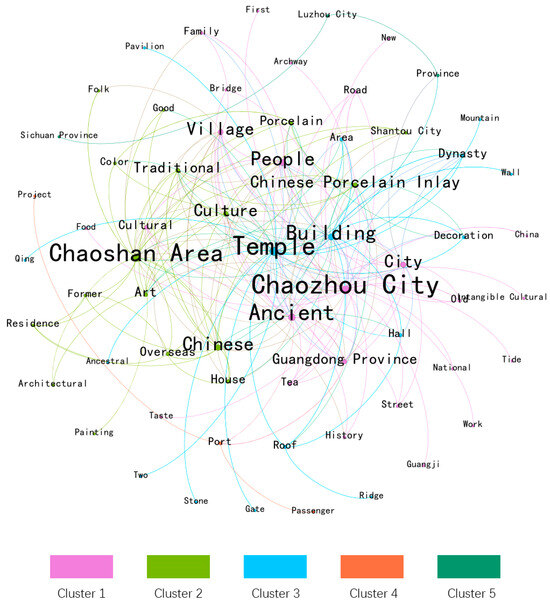

This article uses Gephi software (2022 version) to perform network semantic analysis and shows the keyword co-occurrence network of the top 200 Weibo and Xiaohongshu blog posts. Each dot in the figure represents a keyword, and dots of different colors represent different cluster classifications. Colored lines represent the co-occurrence relationships of keywords. Taking the semantic network analysis diagram of Sina Weibo blog posts as an example, this paper divides the collected Weibo blog keywords into five clusters. As shown in Figure 5, purple represents cluster 1, accounting for 39.06% of keywords, and these include “Chaozhou City”, “Ancient”, “People”, etc. Cluster 1 focuses on the geographical distribution and local customs of inlaid porcelain. Grass green represents cluster 2, accounting for 26.56% of keywords, and these include “Chinese”, “Traditional”, “Overseas”, etc. This cluster focuses on the domestic inheritance and overseas dissemination of inlaid porcelain. Sky blue represents cluster 3, accounting for 25.00% of keywords, and these include “Temple”, “Building”, “Dynasty”, etc. Cluster 3 focuses on the history and carriers of inlaid porcelain. Orange represents cluster 4, accounting for 4.69% of keywords, and these include “Port”, “Taste”, etc. Cluster 4 focuses on the location advantages of inlaid porcelain. Dark green represents cluster 5, accounting for 4.69% of keywords, and these include “Sichuan Province”, “Luzhou City”, etc. Cluster 5 focuses on the introduction of the branches of inlaid porcelain art into Sichuan and Chongqing.

Figure 5.

Semantic network analysis of Sina Weibo posts (image source: drawn by the authors).

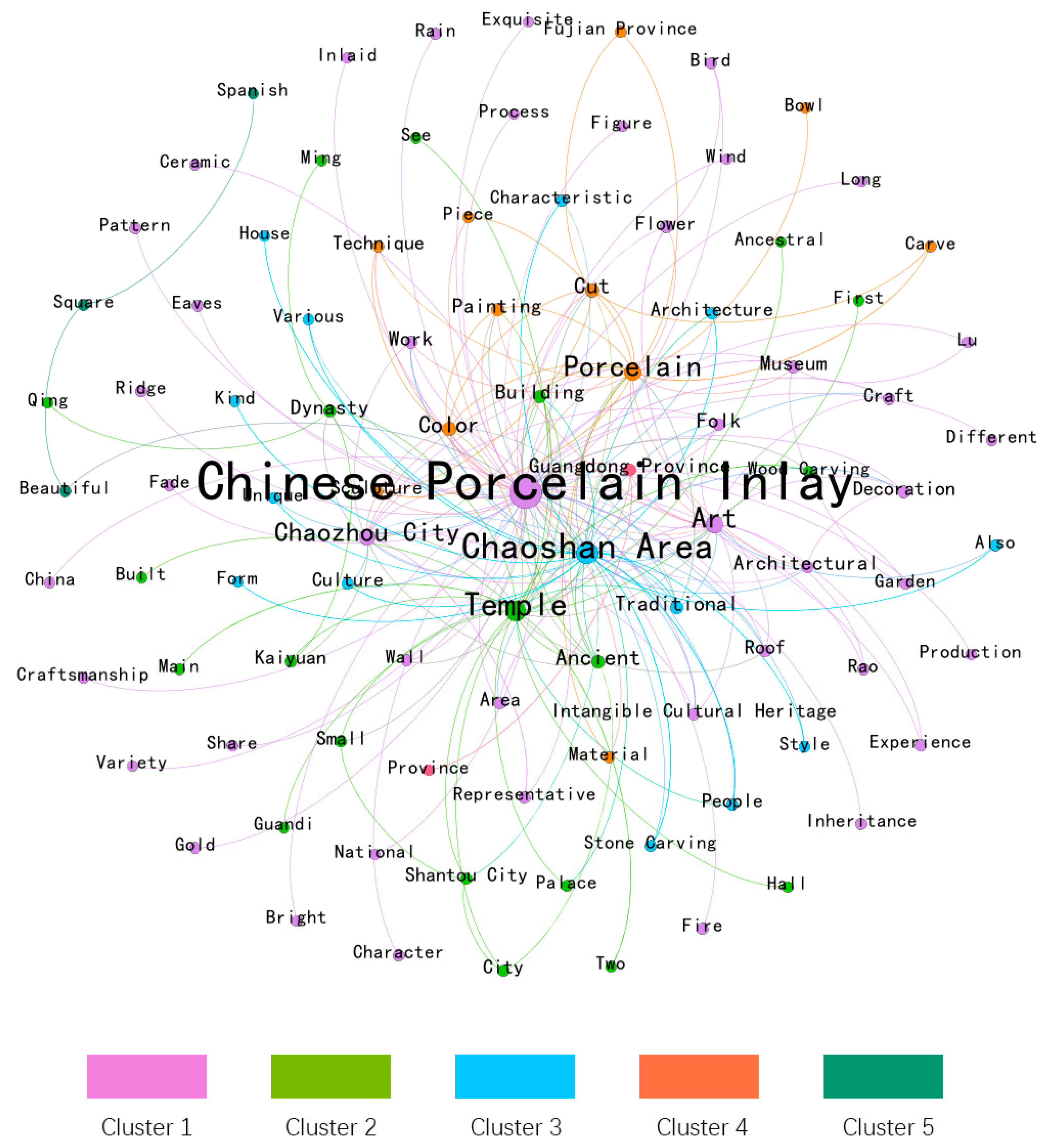

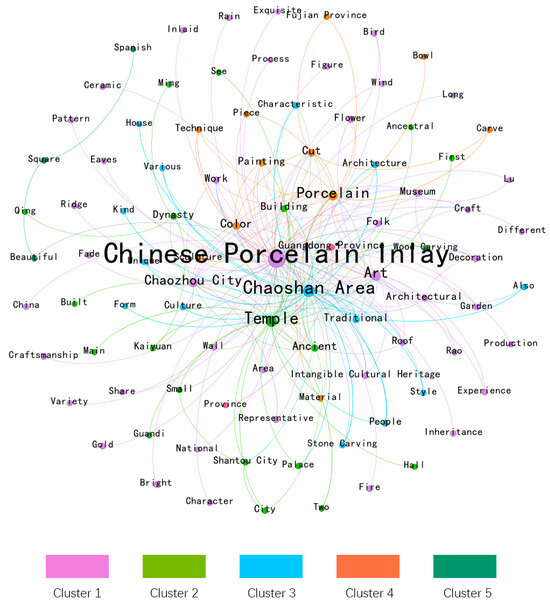

Using the semantic network analysis diagram of Xiaohongshu notes as an example, this paper divides the collected Xiaohongshu blog keywords into five clusters. As shown in Figure 6, purple represents cluster 1, accounting for 46.81% of keywords, including “Chinese porcelain inlay”, “Art”, “Intangible cultural heritage”, etc., and its focus is on the protection and inheritance of the intangible cultural heritage of inlaid porcelain. Grass green represents cluster 2, accounting for 21.28% of keywords, including “Temple”, “Ancient”, “Building”, etc., and its focus is on the carriers and cognition of inlaid porcelain. Sky blue represents cluster 3, accounting for 14.89% of keywords, including “Chaoshan Area”, “Traditional”, “Architecture”, etc., and its focus is on the geographical distribution and local customs of inlaid porcelain. Orange represents cluster 4, accounting for 11.70% of keywords, including “Porcelain”, “Cut”, “Technique”, etc., and its focus is on the craftsmanship and technology of inlaid porcelain. Dark green represents cluster 5, accounting for 3.19% of keywords, including “Spanish”, “Square”, etc., and its focus is on the comparative study of inlaid porcelain art. It is worth mentioning that the peripheral vocabulary, such as “Experience” and “Production”, can reflect Xiaohongshu users’ desire to understand Chinese porcelain inlay and their enthusiasm for experience creation. The platform has greatly promoted the inheritance of Chinese porcelain inlay culture in recent years, showcasing a large number of innovative Chinese porcelain inlay works, Chinese porcelain inlay experience courses, and handmade porcelain inlay experience packages.

Figure 6.

Semantic network analysis of Xiaohongshu posts (image source: drawn by the authors).

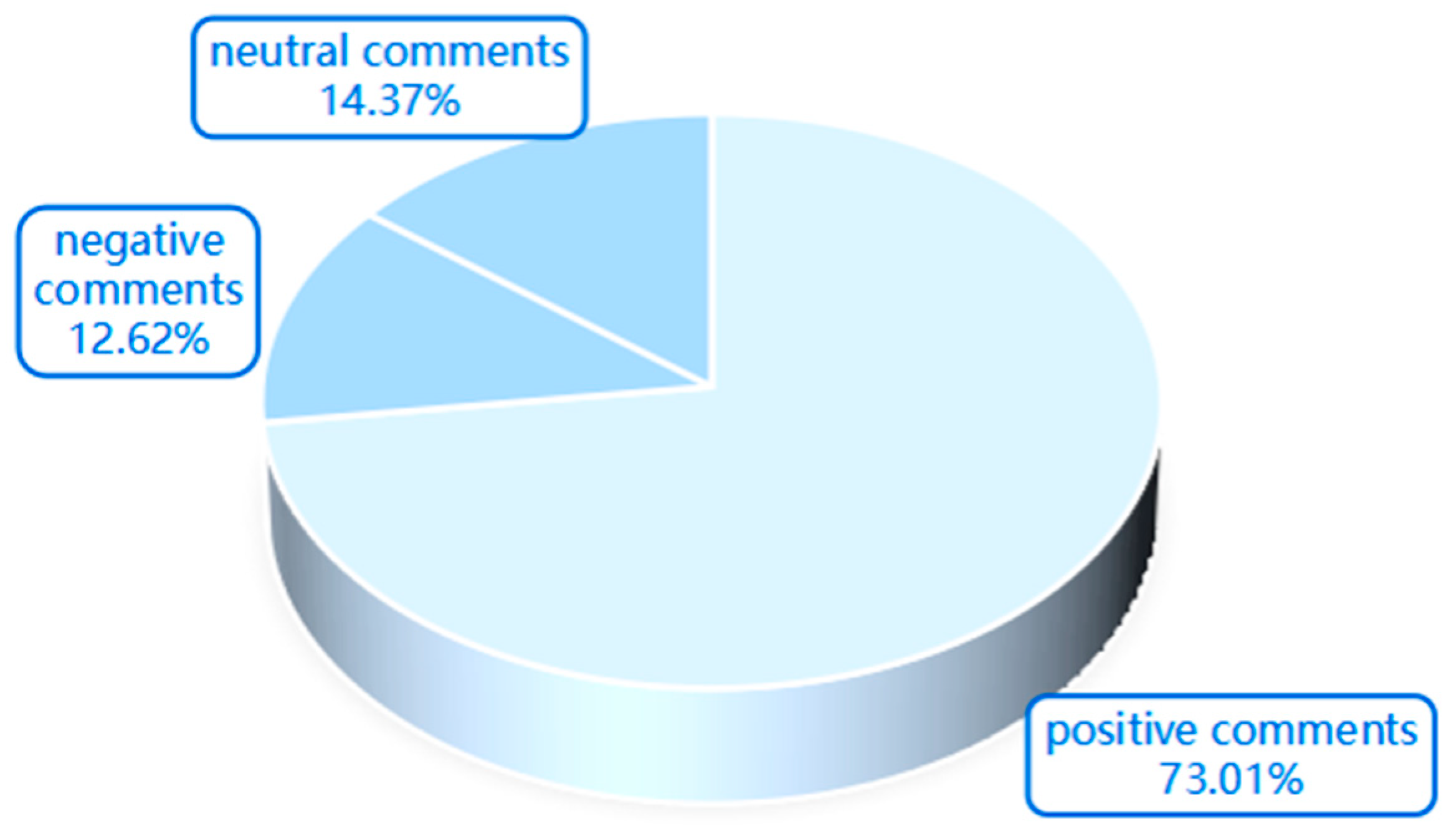

3.3. Emotional Imagery Analysis

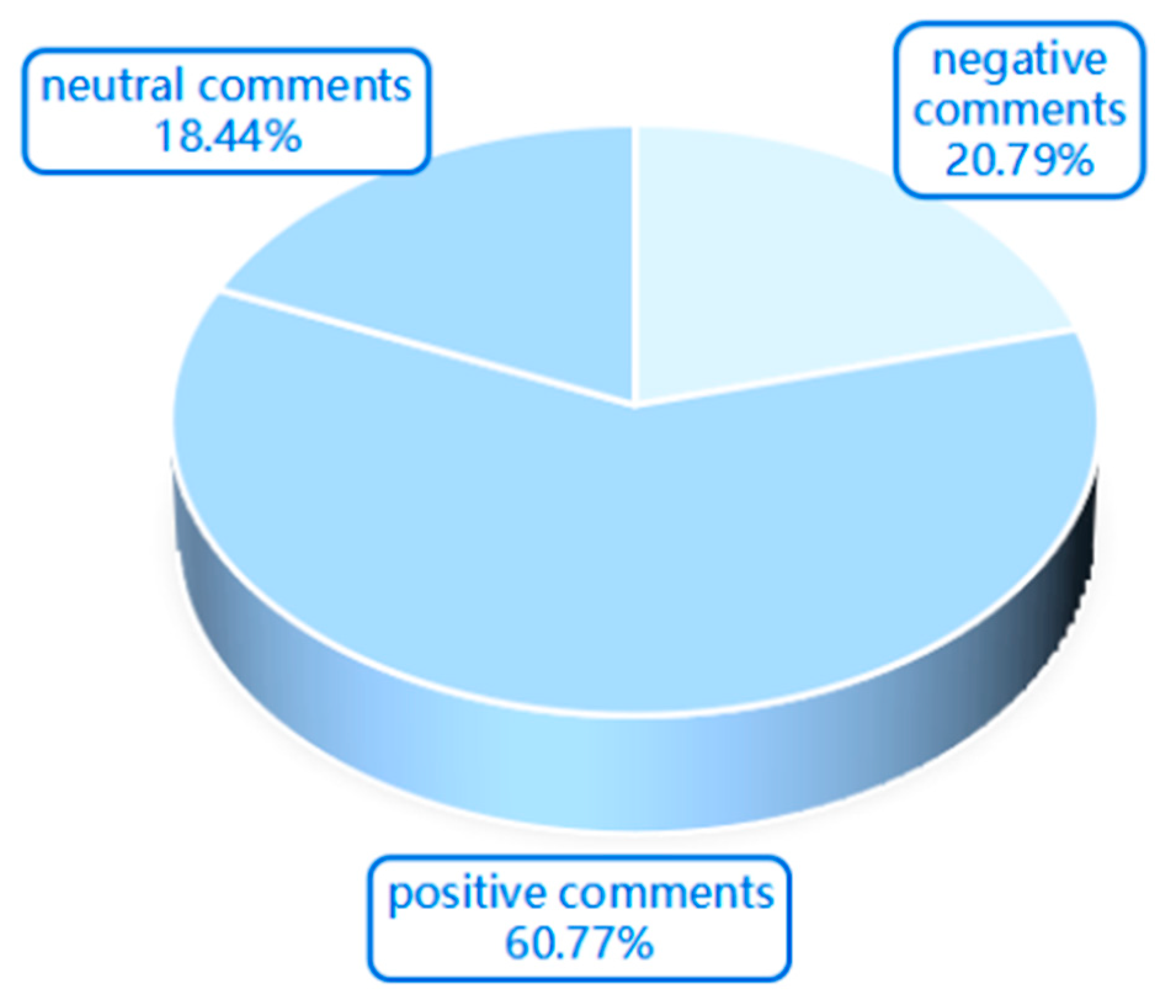

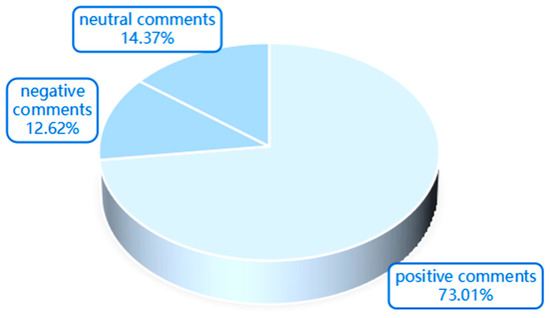

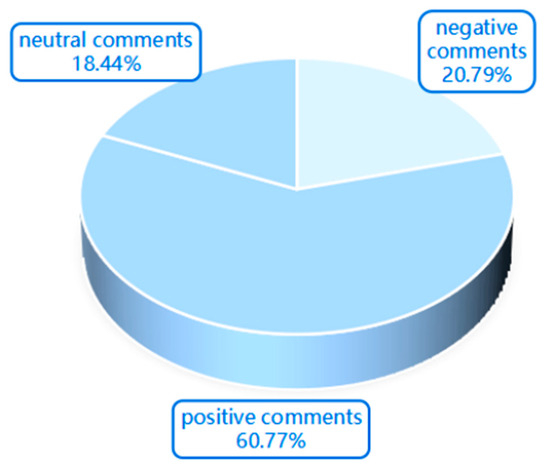

This paper collects 7771 valid Weibo comments and 1361 valid Xiaohongshu comments. We found through Python Snow NLP analysis that there were 5673 positive Weibo comments, accounting for 73.00% of the total; 981 negative comments, accounting for 12.62% of the total; and 1117 neutral comments, accounting for 14.37% of the total (Figure 7). There were 827 positive comments on Xiaohongshu, accounting for 60.76% of the total; 283 negative comments, accounting for 20.79% of the total; and 251 neutral comments, accounting for 18.44% of the total (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Sentiment analysis distribution of Sina Weibo comments. (Image source: drawn by the author).

Figure 8.

Sentiment analysis distribution of Xiaohongshu comments. (Image source: drawn by the author).

The above results show that most users are satisfied with Chinese porcelain inlay as a whole, and very few users are dissatisfied with it. Positive emotions primarily manifest as admiration for the exquisite craftsmanship of Chinese porcelain inlay: “What wonderful craftsmanship!, “So beautiful!”, etc. Chinese porcelain inlay carries the recognition of historical culture: “I am growing increasingly fond of these cultures”. It carries history well, reflected by the admiration for the inheritors of intangible cultural heritage (“It’s really beautiful, and I pay tribute to the inheritors of intangible cultural heritage”) and the strong interest in the inheritance of Chinese porcelain inlay (“Teacher, can I go to your place to learn?”). The recognition of the innovation of Chinese porcelain inlay is evident: “It’s great—the collision of tradition and fashion, with the shadow of Van Gogh’s paintings”. A yearning for the area where the Chinese porcelain inlay is located is also evident: “I love tasting authentic Chaoshan cuisine”, etc. Negative emotions are mainly reflected in the regret over the gradual disappearance of old buildings: “But now many old buildings have been demolished and replaced by new ones”; the lament that Chinese porcelain inlay is highly regional and difficult to popularize: “People in Chaoshan said that it turns out that this is not available all over the country”; the regret that the individual has not visited the city yet: “I haven’t been there yet”; a feeling of helplessness regarding inconvenient transportation: “The only way to get to Chaozhou from Shenzhen is to go to Chaoshan Station, which is far away from the ancient city of Chaozhou”; and discontent with the high prices of Chinese porcelain inlay products: “How expensive is it? I hesitate to inquire about the price”. Comments that draw attention to specific social news events have exacerbated these negative emotions.

3.4. LDA Topic Model Analysis

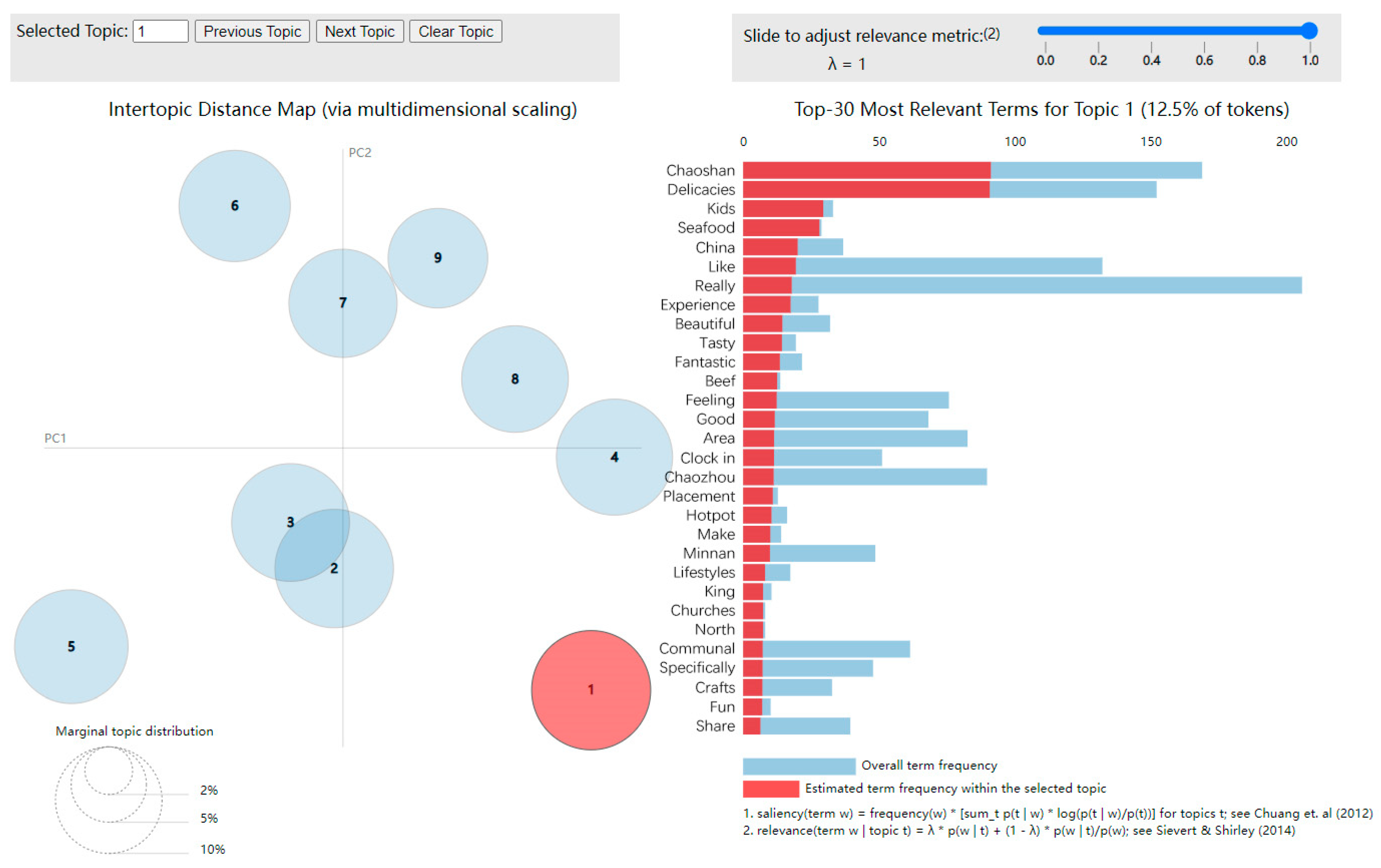

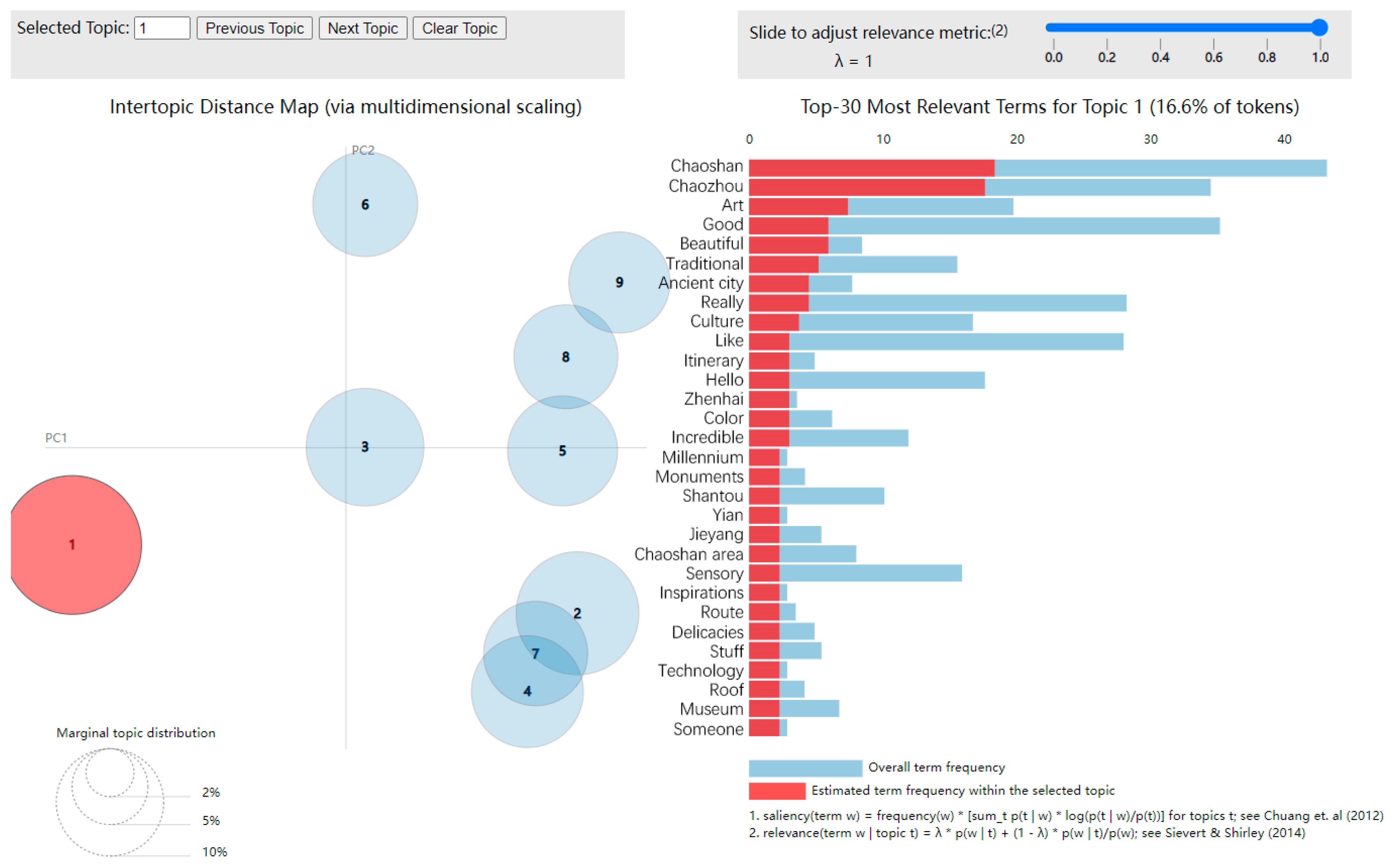

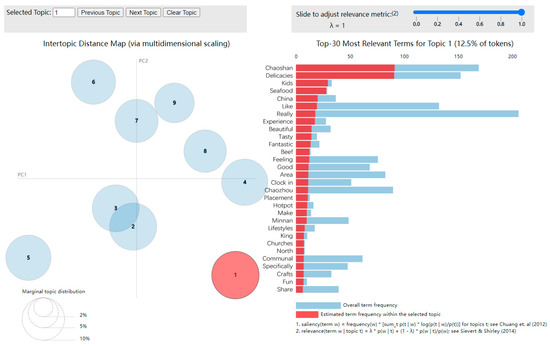

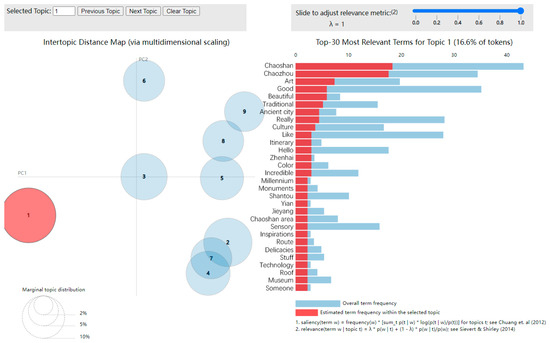

This paper employs the LDA topic model to analyze comment text regarding Chinese porcelain inlay on two prominent social media platforms. We ultimately decided to set the number of extracted topics at nine based on the trends of perplexity and consistency, as well as the clustering results under various numbers of topics. As shown in Table 3, the trained LDA model (Figure 9 and Figure 10) outputs nine topics and their corresponding keywords. The analysis of various topics in the comments on Chinese porcelain inlay is presented below.

Table 3.

Chinese porcelain inlay review topic classification and keywords.

Figure 9.

Visualization of LDA topic features of Sina Weibo comments (image source: drawn by the authors).

Figure 10.

Visualization of LDA topic features of Xiaohongshu comments (image source: drawn by the authors).

Since Chinese porcelain inlay is a traditional architectural decoration craft in Fujian and Guangdong, the high-frequency words in Topic 1 are “exquisite”, “craftsmanship”, “decoration”, “tradition”, etc., which show the users’ interest in the Chinese porcelain inlay craft. At the same time, the appearance of high-frequency words such as “wood carving” shows that users also have a strong interest in other arts and crafts related to Chinese porcelain inlay in Fujian and Guangdong, so this theme is named “arts and crafts”. In Topic 2, the high-frequency words are “Chaoshan”, “food”, “children”, “experience”, “check-in”, etc., which indicate users’ attention toward the location of Chinese porcelain inlay. Especially for parents with children, choosing Chaoshan as a destination can not only provide delicious food, but also offer a novel experience with their children. Therefore, this theme is named “leisure and entertainment”. The high-frequency words in Topic 3 are “features”, “art”, “beautiful scenery”, “route”, “navigation”, “departure”, etc., indicating that adult users have a strong desire for cultural travel centered on Chinese porcelain inlay, so this theme is named “cultural travel”. The high-frequency words in Topic 4 are “like”, “architecture”, “special”, “video”, “home”, etc., which show users’ appreciation of Chinese porcelain inlay art. This appreciation is not necessarily expressed offline, instead being expressed online through images, videos, etc., so this theme is named “Online Appreciation”. The high-frequency words in Topic 5 are “culture”, “worth”, “support”, “protection”, etc., which show users’ concern about the protection of Chinese porcelain inlay, a form of national intangible cultural heritage, and this theme is named “Heritage Protection”. The high-frequency words in Topic 6 are “Chaozhou”, “Chongqing”, “Taiwan”, “Fujian”, “Thailand”, etc., which indicate that users are interested in the geographical distribution of Chinese porcelain inlay and have a certain understanding of the dissemination of inlaid porcelain, so this theme is named “Dissemination Scope”. The high-frequency words in Topic 7 are “bless”, “good health”, “Mazu”, etc. As a decoration on the roof of ancestral halls and temples, Chinese porcelain inlay bears certain religious attributes, meaning that users will choose to pray at that location, and so this theme is named “prayer and blessing”. The high-frequency words in Topic 8 are “subway”, “cool”, “inspiration”, “handmade”, etc. Many Chinese porcelain inlay craftsmen and university scholars are now actively participating in the inheritance and innovation of Chinese porcelain inlay. For example, the production of giant Chinese porcelain inlay public art works in Shenzhen subway stations and the design of Chinese porcelain inlay DIY handmade experience packages have triggered a new era of interest in porcelain inlay inheritance, so this theme is named “inheritance and innovation”. The high-frequency words in Topic 9 are “purchase”, “research”, “popular science”, “interested”, etc., indicating that users have a certain desire to study and purchase Chinese porcelain inlay products, so this theme is named “collection research”.

4. Discussion

Through the above research, we know that (1) Chinese porcelain inlay, as a unique traditional architectural decoration, has a widely recognized cultural and artistic value. Given the cultural and artistic qualities of Chinese porcelain inlay, we should (a) enhance the dissemination of information about Chinese porcelain inlay culture; regularly hold online and offline lectures, exhibitions, training, and academic exchanges on the “intangible cultural heritage” of Chinese porcelain inlay at home and abroad; encourage various media to create content on the “intangible cultural heritage” of Chinese porcelain inlay; produce relevant documentaries and promotional films; establish Chinese porcelain inlay “intangible cultural heritage” experience courses; organize Chinese porcelain inlay publicity and display activities and exhibitions, etc. We should also adapt to the trend of deep media integration, increase the publicity of Chinese porcelain inlay, enrich the means of communication, expand the channels of communication, enhance interactivity with the public, promote cultural exchange and mutual learning regarding Chinese porcelain inlay at home and abroad, and lay a positive foundation for the dissemination of inlaid porcelain culture at home and abroad. (b) It is also important to strengthen cooperation with schools and scientific research institutions. This may involve inviting Chinese porcelain inlay inheritors to teach in schools; increasing the training of Chinese porcelain inlay “intangible cultural heritage” teachers; publishing Chinese porcelain inlay “intangible cultural heritage” general education textbooks; developing Chinese porcelain inlay “intangible cultural heritage” special courses; establishing Chinese porcelain inlay “intangible cultural heritage” special inheritance bases on campus; inviting students to participate in Chinese porcelain inlay experiences, learning, research, and other activities; widely carrying out Chinese porcelain inlay research and social practice activities; and encouraging Chinese porcelain inlay “intangible cultural heritage” to enter campuses.

(2) While most people have a positive emotional evaluation of Chinese porcelain inlay, there are still some individuals who hold negative attitudes towards it. The main reasons are as follows: (a) As urbanization accelerates, old buildings and Chinese porcelain inlay decorations are slowly disappearing. (b) The highly regional nature of Chinese porcelain inlay and its carriers’ difficulty of movement hinder its widespread popularity throughout the country. (c) Chinese porcelain inlay buildings in Fujian and Guangdong are mostly located in rural areas and scattered in places with inconvenient transportation links. (d) The price of Chinese porcelain inlay building components and products is high. On the one hand, these negative comments will cause intangible cultural heritage enthusiasts to give up on the inlaid porcelain craft because of the disappearance of old buildings, the long distances to locations with Chinese porcelain inlay, and the high prices of these products mentioned in online reviews, and turn their attention to other similar products, reducing the attention paid to inlaid porcelain as a form of national intangible cultural heritage. On the other hand, it will cause tourists in Fujian and Guangdong to deliberately avoid areas with a high concentration of inlaid porcelain due to the inconvenience of transportation mentioned in online reviews, reducing the exposure of inlaid porcelain and making the promotion of the inlaid porcelain craft more difficult. In response to the above problems, the government and relevant researchers can make improvements by enacting the following policies: (a) Assigning Chinese porcelain inlay buildings historical significance as cultural relic protection units to avoid demolition and further construction by individuals. Simultaneously, other activities include effectively identifying relevant projects and inheritors for the intangible cultural heritage list, continuously expanding the inheritance team, and enhancing inheritance protection mechanisms. (b) Recording and promoting the popularization of intangible cultural heritage and developing online learning courses on Chinese porcelain inlay. (c) Planning Chinese porcelain inlay intangible cultural heritage travel routes, connecting Chinese porcelain inlay attractions, providing free shuttle buses to and from these locations, and improving the experiences of tourists. (d) Strengthening financial and tax support, providing targeted funding, loan interest subsidies, tax incentives, and other policies for Chinese porcelain inlay craftsmen; reducing the burden on Chinese porcelain inlay craftsmen; encouraging more people to learn Chinese porcelain inlay skills; reducing the labor cost of Chinese porcelain inlay production; and fundamentally controlling the price of Chinese porcelain inlay. (e) Designing cultural and creative Chinese porcelain inlay products that can be mass-produced, reduce costs, and increase public awareness of the intangible cultural heritage of Chinese porcelain inlay, among other things.

(3) Through the LDA topic feature visualization analysis of the comments on Chinese porcelain inlay on the two platforms, people’s cognition of Chinese porcelain inlay can be divided into nine major themes: arts and crafts, leisure and entertainment, cultural travel, online appreciation, heritage protection, dissemination scope, prayer and blessing, inheritance and innovation, and collection and research. Through these classifications, we can understand the public’s needs and expectations regarding Chinese porcelain inlay. In the future promotion of Chinese porcelain inlay as a form of intangible cultural heritage, we can start from different categories, provide targeted services and experiences for different groups of people, and push them accurately. For instance, we can actively explore innovative digital protection methods for the intangible cultural heritage of Chinese porcelain inlay, specifically targeting the online user appreciation group. Through new storage and dissemination methods, Chinese porcelain inlay can also play a significant role online during the protection process, improve the user experience of this group of people, and thus expand the public’s cognition of Chinese porcelain inlay.

5. Conclusions

As a traditional folk craft, porcelain inlay has been around for more than 400 years, and it continues to thrive, showing the strong vitality of folk culture. Although the modes of survival and the cultural significance of porcelain inlay are constantly changing, this traditional craft form has never changed into the form of national survival or spiritual pursuit, carrying the historical mission of change from tradition into the future. Although porcelain inlay is a traditional craft spontaneously formed by the people, its rise and fall are inseparable from the development of the country’s economy, politics, and culture: from the “innovation” of utilizing waste from overcapacity to a means of livelihood for traditional craftsmen, to a stepping stone for “becoming famous in one battle” to improve social status, and to the “feudal dregs” that were hit hard, it has finally been reborn in the contemporary era and has become a form of national intangible cultural heritage, spreading widely both at home and abroad, becoming a spiritual bond connecting China and overseas.

The results of this study show that (1) Chinese porcelain inlay, as a unique traditional architectural decoration craft, has a widely recognized cultural and artistic value. (2) The emotional assessment of Chinese porcelain inlay primarily leans towards positivity, while its negative evaluation primarily manifests in five aspects: lamenting the gradual disappearance of old buildings, lamenting the strong regionality of Chinese porcelain inlay and the difficulty in popularizing it, regretting not having visited locations with Chinese porcelain inlay, frustration at the inconvenience of transportation, and discouragement due to the high price of Chinese porcelain inlay products. (3) The LDA topic model is used to divide the perception of Chinese porcelain inlay into nine major themes: arts and crafts, leisure and entertainment, cultural travel, online appreciation, heritage protection, dissemination scope, prayer and blessing, inheritance and innovation, and collection research. (4) We propose suggestions based on three aspects: awareness cultivation, government support, and cultural innovation. Awareness cultivation provides the basis for development and involves implementing popular education on inlaid porcelain culture, strengthening cooperation with schools and scientific research institutions, and cultivating talents for the inheritance of inlaid porcelain. Government support provides a guarantee, helping to improve relevant policies and regulations, strengthen fiscal and taxation support, and establish an intellectual property system. Finally, cultural innovation is the means for development and comprises building an inlaid porcelain inheritance experience facility system, carrying out digital protection of inlaid porcelain, and protecting and utilizing inlaid porcelain cultural resources.

The shortcomings and prospects of the current study are as follows: (1) Limitations of sample data. Due to the data access restrictions of the platform suppliers and the difficulty of manual annotation, this study only captured blog post and comment data from Weibo and Xiaohongshu for a three-year period, from January 2020 to December 2023. Although we collected tens of thousands of data samples, this sample size is still insufficient, and there was a significant amount of duplicate information. In future research, we hope to expand the data time period, collect a larger sample size, improve the completeness and accuracy of the research results, and provide more solid data support for improving the public’s understanding of the intangible cultural heritage of Chinese porcelain inlay. (2) Limitations of sample selection platform and type. This study used blog posts and comments on Sina Weibo and Xiaohongshu over a three-year period as research samples. We still need to verify whether these data are consistent with other platforms. In the future, we can collect data from more platforms for comparative analysis and observe the similarities and differences between different platforms. There is still a lot of room for exploration in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and Y.C.; methodology, Y.L. and Y.C.; software, Y.L. and Y.C.; validation, Y.L. and Y.C.; formal analysis, Y.L. and Y.C.; investigation, Y.L. and Y.C.; resources, Y.L. and Y.C.; data curation, Y.L. and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and Y.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. and Y.C.; visualization, Y.L. and Y.C.; supervision, Y.L. and Y.C.; project administration, Y.L. and Y.C.; funding acquisition, Y.L. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the Guangdong Provincial Department of Education’s key scientific research platforms and projects for general universities in 2023: Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao cultural heritage protection and innovation design team (Funding Project Number: 2023WCXTD042) and the Fujian social science foundation project: arrangement and research on Historical Materials of A-Mazu Architectural Images in Ming and Qing Dynasties (Funding Project Number: FJ2023C053). The corresponding author, Yile Chen, is a participating researcher in these two funded projects.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Yanyu Li organized and participated deeply in the investigation of this study and has all the original data. If you are interested, please contact Yanyu Li (2009853GAD30002@student.must.edu.mo) for further information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kurin, R. Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage: Key factors in implementing the 2003 Convention. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2007, 2, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 32nd Session of General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Paris, France, 29 September–17 October 2003; Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Newell, P. The PRC’s Law for the Protection of Cultural Relics. Art Antiquity L. 2008, 13, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Folklore in China: Past, Present, and Challenges. Humanities 2018, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.K. Cultural relics, intellectual property, and intangible heritage. Temp. L. Rev. 2008, 81, 433. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X. The Book of Songs; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Repatriation of Cultural Objects: The Case of China. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam [Host], Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X. The Song Rediscovery of Chang’an. J. Song-Yuan Stud. 2024, 53, 127–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, Y.; Yang, S. International Communication of Chinese Intangible Cultural Heritage from a Cross-Cultural Perspective: Taking Chinese Porcelain Inlay Craft as an Example. J. Jianghan Pet. Univ. Work. 2024, 37, 71–73. Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDAUTO&filename=JSZD202405024&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=rJg0XvGZJ2qOhSvae1iWgOiWYG-EndfOw5hzW8KcOAFIiSsIai2liEbbyWuK9dUq (accessed on 16 November 2024). (In Chinese).

- Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, X. On the Presentation of Confucianism in the Chinese Porcelain Inlay of Chaoshan Traditional Architectural Decoration. Design Creates the Future—Proceedings of the 2021 Young Doctor (International) Forum. 2021, p. 10. Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=IPFD&dbname=IPFDLAST2023&filename=ZDCB202105001023&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=x8G0ipCLRzesInIg3HMAd3CD4oiTWol6yIE9xOuttVJZd53AhHxbQ3KUV-J3yq_DM19cZgbqyWQ%3d (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Li, Y.; Yin, J.; Wang, X. Research on the craftsmanship and artistic characteristics of Chinese porcelain inlay in Lingnan traditional architectural decoration. Ind. Des. 2022, 134–136. Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2022&filename=MEIC202205001&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=XRZSNG8aBCWgd0OIWgrXYnURi9BTCeThhhd0bj5zebrS3rZ6D37Q0MmEdMq_TLy6 (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Wen, P. Investigation report on the workshop of Chinese porcelain inlay artists in Chaoshan. Decoration 2008, 94–96. Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2008&filename=ZSHI200802042&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=vYnR1vOGKclEdJ-zQFJvFddOClZg5H8ZVteWkw4j9D5fwTs67u5tFi4vwVn7vwmL (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Lin, M. Guangdong Arts and Crafts Historical Materials; Guangdong Society of Arts and Crafts: Guangzhou, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C. Porcelain Road. A Brief History of Chinese Imperial Porcelain: From Song Dynasty to Qing Dynasty; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 387–414. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, G. The Influence of the Maritime Silk Road on Lingnan Culture; Sun Yat-sen University Press: Guangzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, B.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Z.; Hong, X.; Wei, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Lin, R. Correlation Analysis for the Inheritance Pathways of Inlaid Porcelain Techniques under Rural Revitalization: Case Study of Chaoshan Region, China. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 870–881. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Lu, Y. Analysis on porcelain inlay decoration in traditional buildings in Chaozhou. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2021), Online, 25–26 May 2021; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.R. The cultural property laws of Japan: Social, political, and legal influences. Pac. Rim L. Pol’y J. 2003, 12, 315. [Google Scholar]

- Labadi, S. UNESCO, Cultural Heritage, and Outstanding Universal Value: Value-Based Analyses of the World Heritage and Intangible Cultural Heritage Conventions. 2013. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000220763 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Alivizatou, M. The UNESCO programme for the proclamation of masterpieces of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity: A critical examination. J. Mus. Ethnogr. 2007, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y. World Intangible Cultural Heritage; Ningxia Renmin Press: Yinchuan, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D. A preliminary study of the “originality” of traditional Chinese architectural crafts heritage—The example of large woodworking crafts. Hist. Archit. 2009, 25, 146–153. Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CCJD&dbname=CCJDLAST2&filename=JNZS200902013&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=-GGg3nr5jIIKJ0p7kMLiN5yDNpX4dp73a_UL61me_a2mLSNa_IAod5ZK0mERpwVc (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Li, X. Northern Jiangsu Traditional Building Techniques; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L. On the Inheritance of Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Development of Diversity in Contemporary Society—The Revival of Traditional Handicrafts in Jingdezhen as an Example. Natl. Arts 2015, 1, 71–83. Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2015&filename=MZYS201501014&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=rwecD2pjwGy0KTXLgJMpUNnti4x6FaL0ssc8U8TBw51_dBW01Ak8rIwivUaChtLC (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Ou, J.; Wen, J. Research on Chaoshan Porcelain Inlay Craftsmanship; Shenzhen Newspaper Group Publishing House: Shenzhen, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A. Craftsmanship Follows the Times—A Case Study of Traditional Craft Revitalization; China Light Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, F. Creative Transformation and Innovative Development of Lingnan Traditional Architectural Culture-Taking the Architecture Reconstruction Design of Liwan District in Guangzhou as an Example. J. Physics: Conf. Ser. 2020, 1649, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Ji, T. Toward Systematic Conservation: Exploring the Elements of Cultural Ecology of Non-Heritage Handicrafts. J. Nanjing Univ. Arts (Fine Arts Des.) 2023, 6, 70–76. Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2024&filename=NJYS202306014&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=UxnW80e6IdvEvSDMHAbHrkFf_xobEIAYdQtellE0vxbA29IIDeCFS36Natpa562a (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Pearce, W.; Özkula, S.M.; Greene, A.K.; Teeling, L.; Bansard, J.S.; Omena, J.J.; Rabello, E.T. Visual cross-platform analysis: Digital methods to research social media images. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2020, 23, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Cao, N.; Gotz, D.; Tan, Y.P.; Keim, D.A. A survey on visual analytics of social media data. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2016, 18, 2135–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felt, M. Social media and the social sciences: How researchers employ Big Data analytics. Big Data Soc. 2016, 3, 2053951716645828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, N.A.; Hamid, S.; Hashem IA, T.; Ahmed, E. Social media big data analytics: A survey. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yuan, X.; Wang, Z.; Guo, C.; Liang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Interactive visual discovering of movement patterns from sparsely sampled geo-tagged social media data. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2015, 22, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyani, Y.P.; Saifurrahman, A.; Arini, H.M.; Rizqiawan, A.; Hartono, B.; Utomo, D.S.; Spanellis, A.; Beltran, M.; Nahor, K.M.B.; Paramita, D.; et al. Analyzing public discourse on photovoltaic (PV) adoption in Indonesia: A topic-based sentiment analysis of news articles and social media. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themistocleous, K. Model reconstruction for 3d vizualization of cultural heritage sites using open data from social media: The case study of Soli, Cyprus. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 14, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z.; Chiu, D.K.; Ho, K.K. Social Media Analytics of User Evaluation for Innovative Digital Cultural and Creative Products: Experiences Regarding Dunhuang Cultural Heritage. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2024, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, P. Conflicting images of the Great Wall in cultural heritage tourism. Crit. Arts 2017, 31, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Hua, N.; Martin, J.; Dellapiana, E.; Coscia, C.; Zhang, Y. Social media as a medium to promote local perception expression in China’s World Heritage sites. Land 2022, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Zhang, M. Using content analysis to probe the cognitive image of intangible cultural heritage tourism: An exploration of Chinese social media. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J. A Critical Research on Xiaohongshu for Information Sharing for Chinese Teenagers. Prof. Inf. 2024, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, B.; Tang, X. Translingual practice as a discursive strategy to shape lifestyle and cultural identity. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q. Identifying the role of intangible cultural heritage in distinguishing cities: A social media study of heritage, place, and sense in Guangzhou, China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 27, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council. Circular of the State Council on Publishing the List of the Second Batch of National Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Extended List of the First Batch of National Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2011. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2008-06/14/content_1016331.htm (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- The State Council. Circular of the State Council on Publishing the List of the Third Batch of National Intangible Cultural HERITAGE. 2011. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2011-06/09/content_1880635.htm (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Xue, Y. Modern Lingnan Architectural Decoration Research. Doctoral Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2012; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. A Study on the Culture of Temple Roofs Decoration in Southern Fujian, Eastern Guangdong and Taiwan. Doctoral Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2014; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q. Artistic characteristics and inheritance and development of Chinese porcelain inlay in Chaoshan. J. Zhaoqing Univ. 2024, 45, 124–128. Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDAUTO&filename=SJDI202406019&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=AZM8f20_zPq8tAdl9lgDuhZuFo7ngXZJUV-7pOtt5GxqjPSqXN8Me6BDL4kaZBI9 (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Yin, J.; Lin, T. Memory mapping and schematic reproduction of Chinese porcelain inlay art in Lingnan architectural decoration. J. Nanjing Univ. Arts (Fine Arts Des.) 2023, 85–89. Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2023&filename=NJYS202304014&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=UxnW80e6IdvOjDaGy3fpsw_S7ibXiH6bHio8k2KB6iYEBim1lNRZVKb8lSHvI9oi (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Zhang, H.; Feng, H. Research on Chinese Porcelain Inlay Decorative Art in Ancient Houses in Eastern Guangdong. Art Educ. 2022, 213–216. Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2022&filename=YSJY202208049&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=Z14qHSme_2mQArAHW-frJVaIGHZ1RSUpVxQPdykxeiI5tcM-h7Ee2RtZ8EhG2gKq (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R. Synergistic Diverse Perspective for Topic Evolution Analysis on Weibo. In Document Analysis and Recognition—ICDAR 2024; Barney Smith, E.H., Liwicki, M., Peng, L., Eds.; ICDAR 2024; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, G.; Xia, L.; Wen, X.; Dong, Y. Exploring the Dynamic Interplay of User Characteristics and Topic Influence on Weibo: A Comprehensive Analysis. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Qiu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Li, S. Graphic or short video? The influence mechanism of UGC types on consumers’ purchase intention—Take Xiaohongshu as an example. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 65, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Singh, T.D. Multimodal sentiment analysis: A survey of methods, trends, and challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vretos, N.; Nikolaidis, N.; Pitas, I. Video fingerprinting using Latent Dirichlet Allocation and facial images. Pattern Recognit. 2012, 45, 2489–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).