Performance Improvement of Vehicle and Human Localization and Classification by YOLO Family Networks in Noisy UAV Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

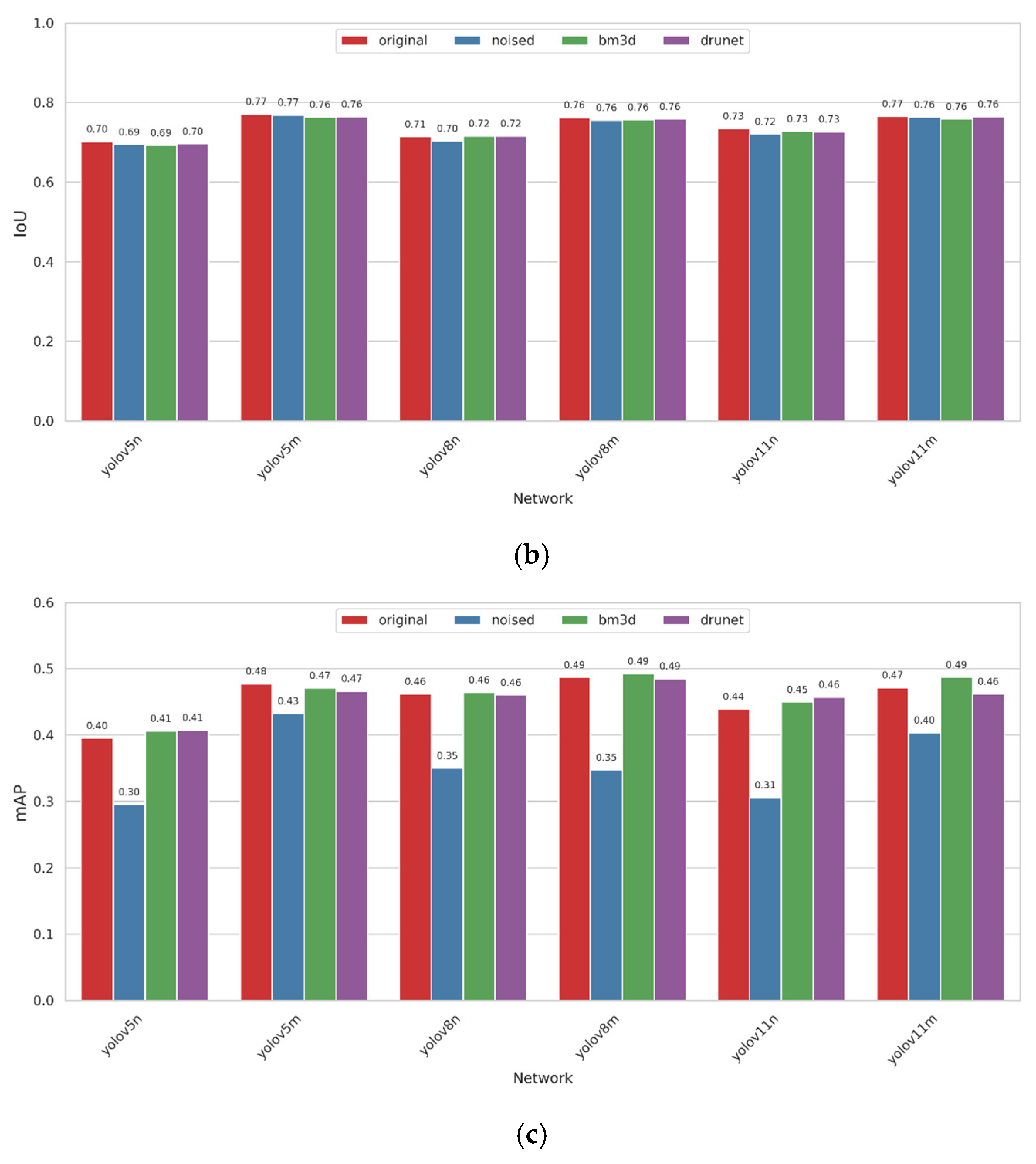

- We have analyzed the performance of six versions of YOLO CNNs (namely, nano and medium versions of YOLOv5, YOLOv8 and YOLOv11) for noise-free and noisy color images contaminated by additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) and established noise levels that start to lead to significant negative outcomes according to four traditional criteria used in the practice of performance analysis for methods of object localization and classification.

- (2)

- Possibilities of performance improvement by image pre-filtering using traditional and neural network-based filters have been analyzed and shown to be efficient for high noise levels.

- (3)

- Possibilities of using augmentation by noise injection at the stage of CNN training have been studied as well; performance of this approach has been compared to performance of image processing with pre-filtering; it is demonstrated that the approach based on denoising produces slightly better results.

- (4)

- CNN performance has been validated for new datasets (including the TAI dataset with better annotation quality); the IoU-related conclusions have been re-evaluated and become more adequate.

- (5)

- The influence of the object size on localization and classification characteristics has been briefly studied.

- (6)

- The case of Poisson noise has been investigated as well; it is shown that the obtained tendencies and results are in good agreement with the case of AWGN.

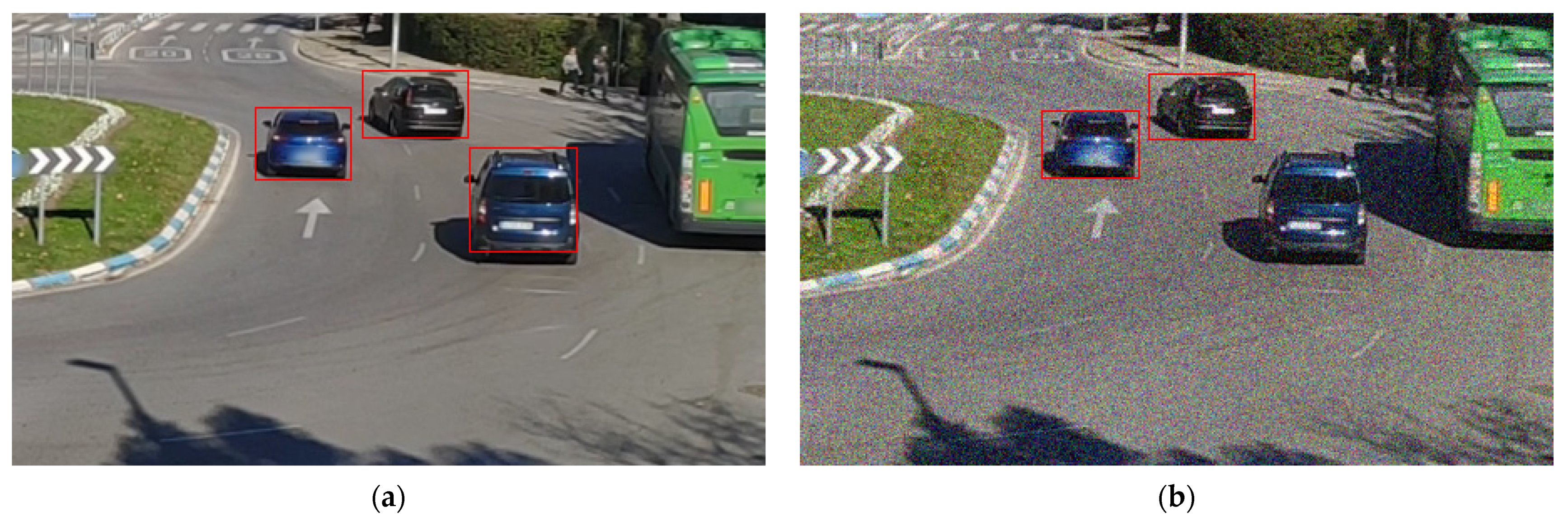

2. Image/Noise Model and Methodology

2.1. Methodology of Our Study

- -

- The considered CNN and its basic characteristics;

- -

- The CNN training approach used and properties of a dataset or datasets employed for training and verification;

- -

- Image quality (types of degradations and their characteristics);

- -

- Methods and algorithms of image pre-processing (if applied).

- -

- Carry out training for all six CNN versions for both noise-free images and noisy one obtained via noise injection (see Section 5 for more details);

- -

- Perform noisy image pre-filtering assuming noise type and characteristics are known in advance (see Section 4.2 and Section 6.1 for more details);

- -

- Calculate the used quantitative criteria for all six CNNs for each noise intensity for noisy images, for images processed by all considered filters, and for the case of CNN training via noise injection;

- -

- Analyze and compare the performance for all aforementioned variants of CNNs, their training and filters applied to obtain conclusions and recommendations;

- -

- In addition, we pay attention to particular aspects of CNN realization on-board, keeping in mind possible practical limitations.

2.2. Basic Noise Model

3. CNN Training, Performance Criteria for Object Localization and Classification and Preliminary Results

3.1. Used Datasets, Considered CNNs and Their Training

3.2. Performance Criteria for Object Localization and Classification

3.3. Preliminary Results

4. Performance of Pre-Filtering and Outcomes of Its Use

4.1. Used Pre-Filtering Methods

4.2. Performance Analysis for Object Localization and Classification in Pre-Filtered Images

5. The Use of Augmentation via Noise Injection

6. Discussion and Computational Aspects

6.1. Poisson Noise Case

6.2. Computational Aspects

6.3. Localization of Small-Sized Objects

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Segeidet, B.M.; Müller-Eie, D.; Lindland, K.A. Nordic Smart Sustainable City Lessons from Theory and Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, J. A Review of the Theory and Practice of Smart City Construction in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, N.; Abbas, Z.; Liu, X.; Khan, S.S.; Foster, E.D.; Larkin, S. A Survey: Future Smart Cities Based on Advance Control of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmpounakis, M.; Espadaler-Clapés, J.; Tsitsokas, D.; Mordan, T.; Geroliminis, N. A New Perspective on Urban Mobility Through Large-Scale Drone Experiments for Smarter, Sustainable Cities. Drones 2025, 9, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balivada, S.; Gao, J.; Sha, Y.; Lagisetty, M.; Vichare, D. UAV-Based Transport Management for Smart Cities Using Machine Learning. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.; Youn, J. Performance Evaluation of an Object Detection Model Using Drone Imagery in Urban Areas for Semi-Automatic Artificial Intelligence Dataset Construction. Sensors 2024, 24, 6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Deng, J. MSCD-YOLO: A Lightweight Dense Pedestrian Detection Model with Finer-Grained Feature Information Interaction. Sensors 2025, 25, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawsawi, A.N.; Khan, S.D.; Rehman, F.U. Enhanced YOLOv8-Based Model with Context Enrichment Module for Crowd Counting in Complex Drone Imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaabi, K.; El Fawair, A.R. Drones applications for smart cities: Monitoring palm trees and street lights. Open Geosci. 2022, 14, 1650–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, G. A Review on UAV-Based Remote Sensing Technologies for Construction and Civil Applications. Drones 2022, 6, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Ni, J.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Cao, W. A Survey of Object Detection for UAVs Based on Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, D.; Ben, G.; Gao, Y. Deep Learning-Based Object Detection Techniques for Remote Sensing Images: A Survey. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.E.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tsekhmystro, R.; Lukin, V.; Krytskyi, D. UAV Image Denoising and Its Impact on Performance of Object Localization and Classification in UAV Images. Computation 2025, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Ali, A.; Jalil, A.; Khan, B.; Cheema, K.M.; Murad, M.; Milyani, A.H. Efficient online object tracking scheme for challenging scenarios. Sensors 2021, 21, 8481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachar, P.; Wilk, Ł.; Pilarska-Mazurek, M.; Meißner, H.; Ostrowski, W. Assessment of UAV image quality in terms of optical resolution. In International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Proceedings of the EuroCOW 2025—European Workshop on Calibration and Orientation Remote Sensing, Warsaw, Poland, 16–18 June 2025; ISPRS: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2025; pp. 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, T.; Niu, X. Enhancing UAV Object Detection in Low-Light Conditions with ELS-YOLO: A Lightweight Model Based on Improved YOLOv11. Sensors 2025, 25, 4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, R.; Wu, Z.; Bian, Z.; Huang, T. YOLO-UIR: A Lightweight and Accurate Infrared Object Detection Network Using UAV Platforms. Drones 2025, 9, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekhmystro, R.; Rubel, O.; Lukin, V. Investigation of the effect of object size on accuracy of human localization in images acquired from unmanned aerial vehicles. Aerosp. Tech. Technol. 2024, 194, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2999–3007. [Google Scholar]

- Zenodo. Ultralytics/Yolov5: v7.0—YOLOv5 SOTA Realtime Instance Segmentation. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/7347926 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Bozcan, I.; Kayacan, E. AU-AIR: A Multi-modal Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Dataset for Low Altitude Traffic Surveillance. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Bian, X.; Ling, H.; Hu, Q. Vision Meets Drones: A Challenge. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekhmystro, R.; Rubel, O.; Prysiazhniuk, O.; Lukin, V. Impact of distortions in UAV images on quality and accuracy of object localization. Radioelectron. Comput. Syst. 2024, 2024, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, R.; Sambath, M. YOLOv8: A Novel Object Detection Algorithm with Enhanced Performance and Robustness. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS), Chennai, India, 18–19 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova, M.; Japkowicz, N.; Szpakowicz, S. Beyond Accuracy, F-Score and ROC: A Family of Discriminant Measures for Performance Evaluation. In Advances in Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized Intersection Over Union: A Metric and a Loss for Bounding Box Regression. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dabov, K.; Foi, A.; Katkovnik, V.; Egiazarian, K. Image Denoising by Sparse 3-D Transform-Domain Collaborative Filtering. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2007, 16, 2080–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkinen, Y.; Azzari, L.; Foi, A. Collaborative Filtering of Correlated Noise: Exact Transform-Domain Variance for Improved Shrinkage and Patch Matching. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 8339–8354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L.; Gool, L.V.; Timofte, R. Plug-and-Play Image Restoration with Deep Denoiser Prior. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 6360–6376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xiao, X.; Guo, B.; Qin, Q.; Chen, R. An Effective Image Denoising Method for UAV Images via Improved Generative Adversarial Networks. Sensors 2018, 18, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingjuan, N.; Xueru, M.; Run, M.; Jie, P.; Shan, W.; Hao, S.; She, H. Research on UAV image denoising effect based on improved Wavelet Threshold of BEMD. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (JPCS), Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Big Data and Applied Statistics (ISBDAS2019), Dalian, China, 20–22 September 2019; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Chai, Y.; Hu, Z.; Sun, Y. A novel image denoising algorithm and its application in UAV inspection of oil and gas pipelines. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 83, 34393–34415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L.T.; Sappa, A.D. A Decade of You Only Look Once (YOLO) for Object Detection: A Review. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Flores-Calero, M.; Qureshi, R.; Badgujar, C.; Nepal, U.; Poulose, A.; Zeno, P.; Vaddevolu, U.B.P.; Khan, S.; Shoman, M.; et al. YOLO advances to its genesis: A decadal and comprehensive review of the You Only Look Once (YOLO) series. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Lv, M.; Huang, M.; Qu, M.; Zou, K.; Chen, L.; Feng, L. An Improved YOLOv7 Model for Surface Damage Detection on Wind Turbine Blades Based on Low-Quality UAV Images. Drones 2024, 8, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhu, X. YOLO-SMUG: An Efficient and Lightweight Infrared Object Detection Model for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Drones 2025, 9, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Fu, Y.; Wang, D.; Guo, R.; Zhao, X.; Fang, J. YOLO-UAV: Object Detection Method of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery Based on Efficient Multi-Scale Feature Fusion. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 126857–126878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poojary, R.; Raina, R.; Mondal, A.K. Effect of data-augmentation on fine-tuned CNN model performance. IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2021, 10, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbiyik, M.E. Data Augmentation in Training CNNs: Injecting Noise to Images. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeny, M.; Neshat, A.A.; Hussain, M.A.; Kia, A.; Marhamati, M.; Jahanbakhshi, A.; Hamarneh, G. Learning-to-augment strategy using noisy and denoised data: Improving generalizability of deep CNN for the detection of COVID-19 in X-ray images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, F.G.; Tsourdos, A. UAV-Based Remote Sensing; MDPI AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Michailidis, E.T.; Maliatsos, K.; Skoutas, D.N.; Vouyioukas, D.; Skianis, C. Secure UAV-Aided Mobile Edge Computing for IoT: A Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 86353–86383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, Y.; Fan, L.; Fan, J. YOLOv5s-Fog: An Improved Model Based on YOLOv5s for Object Detection in Foggy Weather Scenarios. Sensors 2023, 23, 5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geever, D.; Brophy, T.; Molloy, D.; Ward, E.; Deegan, B.; Glavin, M. A Study on the Impact of Rain on Object Detection for Automotive Applications. IEEE Open J. Veh. Technol. 2025, 6, 1287–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieberth, T.; Wackrow, R.; Chandler, J.H. UAV image blur—Its influence and ways to correct it. In International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Geomatics, Toronto, ON, Canada, 30 August–2 September 2015; SPRS: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2025; pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik, N.; Barker, J.W.; Gaus, Y.F.A.; Breckon, T.P. Lost in Compression: The Impact of Lossy Image Compression on Variable Size Object Detection within Infrared Imagery. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Fadili, M.J.; Starck, J.L. Multi-Scale Variance Stabilizing Transform for Multi-Dimensional Poisson Count Image Denoising. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics Speech and Signal Processing, Toulouse, France, 14–19 May 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendur, L.; Selesnick, I.W. Bivariate shrinkage with local variance estimation. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2002, 9, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogrebnyak, O.; Lukin, V.V. Wiener Discrete Cosine Transform-Based Image Filtering. J. Electron. Imaging 2012, 21, 043020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.; Milanfar, P. Is Denoising Dead? IEEE Trans. Image Process 2010, 19, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uss, M.L.; Vozel, B.; Lukin, V.V.; Chehdi, K. Image informative maps for component-wise estimating parameters of signal-dependent noise. J. Electron. Imaging 2013, 22, 013019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatnassi, S.; Yahia, M.; Ali, T.; Abdelfattah, R. Performance Improvement of AWGN Filters by INLP Technique. In Advanced Information Networking and Applications; AINA 2025 Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 251, pp. 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamed, A.; Lin, S.; Brown, M.S. A High-Quality Denoising Dataset for Smartphone Cameras. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 1692–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, H.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L. Real-world Noisy Image Denoising: A New Benchmark (Version 1). arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foi, A.; Trimeche, M.; Katkovnik, V.; Egiazarian, K. Practical Poissonian-Gaussian Noise Modeling and Fitting for Single-Image Raw-Data. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2008, 17, 1737–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uss, M.L.; Vozel, B.; Lukin, V.; Chehdi, K. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Spatially Correlated Signal-Dependent Noise in Hyperspectral Images. Opt. Eng. 2012, 51, 111712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Chen, G.; Heng, P.A. From Noise Modeling to Blind Image Denoising. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousha, S.; Maleky, A.; Brown, M.S.; Brubaker, M.A. Modeling sRGB Camera Noise with Normalizing Flows. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 17442–17450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitzel, S.M.; Jensen, E.C.; Frieder, O. MAP. In Encyclopedia of Database Systems; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemposta Rosende, S.; Ghisler, S.; Fernández-Andrés, J.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Dataset: Traffic Images Captured from UAVs for Use in Training Machine Vision Algorithms for Traffic Management. Data 2022, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adli, T.; Bujaković, D.M.; Bondžulić, B.P.; Laidouni, M.Z.; Andrić, M.S. Robustness of YOLO models for object detection in remote sensing images. J. Electr. Eng. 2025, 76, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buades, A.; Coll, B.; Morel, J.M. NonLocal image and movie denoising. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2008, 76, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, W.; Li, Y. An improved non-local means filter for color image denoising. Optik 2018, 173, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizenberg, I.; Tovt, Y. Intelligent Frequency Domain Image Filtering Based on a Multilayer Neural Network with Multi-Valued Neurons. Algorithms 2025, 18, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elad, M.; Kawar, B.; Vaksman, G. Image Denoising: The Deep Learning Revolution and Beyond—A Survey Paper. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2023, 16, 1594–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honzátko, D.; Kruliš, M. Accelerating block-matching and 3D filtering method for image denoising on GPUs. J. Real Time Image Proc. 2019, 16, 2273–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makitalo, M.; Foi, A. Optimal Inversion of the Generalized Anscombe Transformation for Poisson-Gaussian Noise. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2013, 22, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L. PS-YOLO: A Lighter and Faster Network for UAV Object Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyatykh, S.; Zheng, L.; Hesser, J. Fast noise variance estimation by principal component analysis. In Image Processing: Algorithms and Systems XI, Proceedings of the IS&T/SPIE Electronic Imaging, Burlingame, CA, USA, 3–7 February 2013; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/8655/1/Fast-noise-variance-estimation-by-principal-component-analysis/10.1117/12.2000276.full (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Colom, M.; Lebrun, M.; Buades, A.; Morel, J.M. A non-parametric approach for the estimation of intensity-frequency dependent noise. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Paris, France, 27–30 October 2014; pp. 4261–4265. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7025865 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Abramov, S.; Abramova, V.; Uss, M.; Lukin, V.; Vozel, B.; Chehdi, K. Blind Estimation Of Signal-Dependent Noise Parameters For Color Image Database. In Proceedings of the European Workshop on Visual Information Processing (EUVIP), Paris, France, 10–12 June 2013; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6623956/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

| YOLO Version | Parameter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| FLOPS (GFLOPs) | Parameters (M) | Inference Time (ms) | |

| V5n | 7.2 | 2.510 | 38.4 |

| V5m | 64.4 | 25.070 | 107.6 |

| V8n | 8.2 | 3.012 | 23.3 |

| V8m | 79.1 | 25.863 | 52.8 |

| V11n | 6.5 | 2.591 | 27.4 |

| V11m | 68.2 | 20.060 | 62.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makarichev, V.; Tsekhmystro, R.; Lukin, V.; Krytskyi, D. Performance Improvement of Vehicle and Human Localization and Classification by YOLO Family Networks in Noisy UAV Images. Information 2025, 16, 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121087

Makarichev V, Tsekhmystro R, Lukin V, Krytskyi D. Performance Improvement of Vehicle and Human Localization and Classification by YOLO Family Networks in Noisy UAV Images. Information. 2025; 16(12):1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121087

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakarichev, Viktor, Rostyslav Tsekhmystro, Vladimir Lukin, and Dmytro Krytskyi. 2025. "Performance Improvement of Vehicle and Human Localization and Classification by YOLO Family Networks in Noisy UAV Images" Information 16, no. 12: 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121087

APA StyleMakarichev, V., Tsekhmystro, R., Lukin, V., & Krytskyi, D. (2025). Performance Improvement of Vehicle and Human Localization and Classification by YOLO Family Networks in Noisy UAV Images. Information, 16(12), 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121087