Abstract

Next Point-of-Interest (POI) recommendation is a crucial task in personalized location-based services, aiming to predict the next POI that a user might visit based on their historical trajectories. Although sequence models and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have achieved significant success, they often overlook the diversity and dynamics of user preferences. To address these issues, researchers have begun to employ Hypergraph Convolutional Networks (HGCNs) for disentangled representation learning. However, two critical problems have received less attention: (1) the limited expressive capacity of conventional hypergraph convolution layers, which restricts the modeling of complex nonlinear user–POI preference interactions and consequently weakens generalization performance, and (2) the inadequate utilization of contrastive learning mechanisms, which prevents fully capturing cross-view collaborative signals and limits the exploitation of complementary multi-view information. To tackle these challenges, we propose a Nonlinear Enhanced Disentangled Contrastive Hypergraph Learning (NE-DCHL) for next POI recommendation. The proposed model enhances nonlinear modeling capability and generalization by integrating ReLU activation, residual connections, and dropout regularization within the hypergraph convolution layer. A K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)-based weighted adjacency matrix is employed to construct the geographical-view hypergraph, reducing computational complexity while maintaining essential spatial correlations. Moreover, a mini-batch InfoNCE loss and the GRACE (deep GRAph Contrastive rEpresentation learning) framework are utilized to improve efficiency and cross-view collaboration. Extensive experiments on two real-world datasets demonstrate that NE-DCHL consistently outperforms the original DCHL and other state-of-the-art approaches.

1. Introduction

With the widespread adoption of Location-Based Social Networks (LBSNs) [1], it has become increasingly common for users to share geotagged life experiences on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Yelp, and Dianping. Therefore, personalized recommendation systems are widely used to help users discover points of interest (POIs) from massive volumes of information. Among these systems, next POI recommendation is particularly crucial for meeting users’ real-time spatial exploration behaviors and enhancing the utility of LBS platforms. This is a fundamental task within POI recommendation research, aiming to predict the location of a user’s next visit based on their historical trajectory [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Most existing approaches treat next Point-of-Interest (POI) recommendation as a sequence prediction problem, evolving from early traditional Markov chain models based on state transition probabilities [8,9], advancing to Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) architectures adept at handling temporal dependencies [10,11,12,13], and more recently to self-attention architectures such as Transformers [14,15]. Among these sequence-based methods, several studies [11,12,13,14,15] have validated the importance of spatiotemporal contexts and integrated them to uncover inherent patterns within user trajectories. However, these methods mainly focus on exploring sequences within individual users, struggling to effectively leverage collaborative information from other users.

Given the remarkable achievements of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Hypergraph Neural Networks (HGNNs) in capturing high-order similarities among neighbors and modeling complex relationships, many researchers have employed GNN or HGNN frameworks to enhance the representational capacity of both POIs and users [2,3,4,7,16,17,18,19,20,21]. For instance, Graph-Flashback [4] utilizes a spatial-temporal knowledge graph to enrich POI representations and incorporates them into RNN-based architectures, thereby capturing sequential transition patterns for next POI recommendation. Lai et al. [22] proposed a Disentangled Contrastive Hypergraph Learning (DCHL) framework that jointly considers complex collaborations, global transitions, and geographical dependencies between users and POIs to achieve multi-view representation disentanglement. This approach effectively mitigates the challenges arising from suboptimal and entangled user representations, as well as the insufficient modeling of collaborative relationships in HGNN-based next POI recommendation.

Although the aforementioned methods have achieved state-of-the-art performance in next POI recommendation, two major challenges remain. First, while hypergraph-based approaches effectively model high-order interactions, their inherently linear propagation mechanisms limit the ability to capture complex user preference couplings. Second, weak cross-view alignment, resulting from the lack of effective inter-view collaboration mechanisms, further restricts the utilization of multi-source information [23]. Furthermore, existing studies often adopt static fusion strategies to integrate collaborative, transitional, and geographic views, without fully exploring the dynamic complementarities between them. As a result, the absence of a contrastive learning mechanism to enhance cross-view collaboration leads to suboptimal utilization of multi-source information [24,25].

To address these challenges, we propose a nonlinear, contrastive, multi-view hypergraph learning framework for next POI recommendation, called Nonlinear Enhanced Disentangled Contrastive Hypergraph Learning (NE-DCHL). First, the hypergraph convolutional layer is redesigned by incorporating nonlinear activation functions (ReLU), residual connections, and Dropout regularization, which enables the model to capture complex preference interactions while mitigating over-smoothing and overfitting. Secondly, the construction of the geographic view hypergraph is optimized using a KNN-based weighted adjacency matrix [26], which sparsifies the POI-POI geographic relationships while preserving semantically important connections. Compared to dense distance thresholds, this approach does not compromise spatial coherence. Finally, to enhance scalability and inter-view collaboration, we employ a batch-wise InfoNCE loss for efficient contrastive learning on large-scale datasets, inspired by a self-supervised GRACE-style module [27,28]. By unifying disentangled representation learning, nonlinear hypergraph propagation, and adaptive cross-view contrastive supervision, the proposed framework alleviates major limitations in next-POI recommendation for urban location-based service (LBS) scenarios, as demonstrated on two Foursquare city datasets. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- Nonlinear Hypergraph Enhancement: We enhance the expressive power of hypergraph convolutional layers by integrating ReLU activation, residual connections, and dropout regularization, thereby enabling more effective modeling of complex nonlinear user–POI relationships. Specifically, we apply ReLU in the HGCN layers to achieve more expressive propagation, while Sigmoid is used only in the user-view gating module to preserve negative values.

- KNN-based Geographic Sparsification: We employ a KNN-weighted adjacency matrix to sparsify POI relationships, significantly improving computational efficiency while maintaining spatial and semantic integrity.

- Adaptive Cross-View Contrastive Learning Module: We design an adaptive contrastive learning mechanism to strengthen multi-view collaboration through a GRACE-inspired batch-wise InfoNCE loss, enabling scalable and robust representation learning.

2. Related Work

2.1. Next POI Recommendation

Next POI recommendation has undergone three major paradigm shifts: sequence modeling, graph-based learning, and hypergraph enhancement. Early sequence-based approaches, such as Markov chains models [8] and RNN-based methods [13,23,29], focused on capturing transitions within user trajectories but failed to model non-sequential dependencies or cross-user collaborative signals Recent advances based on self-attention mechanisms have enabled the explicit modeling of spatiotemporal contexts, but still struggle with the long-tail POI problem due to sparse interactions [15].To overcome these limitations, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have been leveraged to encode user–POI interactions into graph structures, thereby enhancing the representation of spatial and relational dependencies. For instance, Graph-Flashback [4] combines spatiotemporal knowledge graphs with RNN architectures to model sequential transitions, while Sequence-to-Graph POI Recommender (SGRec) [18] employs Seq2Graph enhancement techniques to capture collaborative signals across users. However, traditional GNNs are limited to pairwise relationships, ignoring higher-order dependencies in user mobility behaviors.

To further capture such high-order relations, HGNNs [2,30] extend conventional graph structures by linking multiple nodes through hyperedges, effectively modeling complex group interactions. The Multi-view Spatial-Temporal Enhanced Hypergraph Network (MSTHN) [2] pioneered the use of multi-view hypergraphs to disentangle spatiotemporal and collaborative signals, but its linear propagation layers limit the ability to capture nonlinear couplings among user preferences. Recent works like Spatio-Temporal HyperGraph Convolutional Network (STHGCN) [21] further integrate hypergraph learning with spatiotemporal gating mechanisms, but rely on static fusion strategies, limiting adaptability to dynamic user behaviors. These limitations highlight the need for nonlinear hypergraph architectures and adaptive inter-view coordination mechanisms to improve robustness, generalizability, and interpretability in next POI recommendation.

2.2. Contrastive Learning

Contrastive learning has emerged as a powerful tool for mitigating data sparsity and enhancing representation disentanglement. In the context of POI recommendation, several methods have incorporated contrastive learning to improve model robustness and representation quality. For instance, Disen-POI [31] employs self-supervised objectives to disentangle sequential and geographical influences, while Hypergraph Contrastive Collaborative Filtering (HCCF) [32] utilizes hypergraph contrastive learning to align both local and global collaborative relationships. However, existing methods suffer from two critical deficiencies: (1) most approaches construct negative sample pairs randomly, neglecting domain-specific negative sampling strategies, which weakens discriminative capability; and (2) contrastive objectives are generally applied independently within each view, failing to enforce cross-view consistency. Notably, conventional contrastive learning in POI recommendation predominantly relies on intra-view augmentations—such as graph structure perturbation or feature masking within a single view—to generate positive-negative sample pairs, focusing on strengthening representation robustness within individual views. In contrast, NE-DCHL moves beyond this paradigm by implementing cross-view contrastive learning, which explicitly aligns heterogeneous views (collaborative, transition, geographic) at the representation level, leveraging view-specific semantic complementarity to enhance inter-view consistency. Although GRACE [28] and its variants attempt to alleviate this issue by aligning embeddings between augmented views of a graph, they primarily rely on homogeneous graph assumptions, thereby limiting their applicability to heterogeneous POI interaction scenarios. To address these limitations, our framework introduces a cross-view contrastive objective that directly models the interdependencies among collaborative, transitional, and geographical factors.

2.3. Geographic Location and Disentangled Representation Learning

Geographic proximity is the cornerstone of POI recommendation, but traditional methods often employ simple heuristics that either oversimplify spatial coherence or lead to excessive computational costs. For example, approaches using fixed distance thresholds [22,33] or hyperedge-based geographical graphs [2,34] lack adaptability to varying urban densities. In our framework, the KNN weighted adjacency matrix dynamically sparsifies geographical location relationships, preserving critical connections while reducing redundancy. Inspired by scalable graph sparsification techniques [35], this design can be further tailored to capture fine-grained spatial semantics. Specifically, we adopt an asymmetric KNN strategy for geographical association mining to support this matrix. To correct the potential topological bias from this asymmetric design, we propose two general symmetrization schemes: first, a mutual verification scheme that takes the element-wise minimum of the weighted adjacency matrix and its transpose, retaining only mutually co-occurring edges; second, a matrix intersection scheme that calculates the element-wise product of the asymmetric matrix and its transpose, automatically removing invalid one-way edges.

Disentangled representation learning [36,37] aims to isolate the underlying factors governing user behavior. For instance, the Disentangling Sequential and Geographical Influence for Point-of-Interest (Disen-POI) [31] leverages adversarial training to separate sequential and geographical influences. Nevertheless, its reliance on a static fusion mechanism hinders effective context-aware preference integration. Similarly, the hypergraph-based disentangled Multi-View Spatial-Temporal Enhanced Hypergraph Network (MSTHN) method [2] enhances interpretability but remains constrained by its linear aggregation scheme. Building upon these insights, our integration of ReLU-enhanced hypergraph convolutions with adaptive gating fusion enables nonlinear inter-factor interactions and dynamic weight allocation, which are essential for modeling evolving user preferences in real-world LBS environments.

3. Preliminary

In this section, we first formulate the task of next POI recommendation and then introduce the definition of hypergraph.

3.1. Task Formulation

Let and represent the set of users and POIs, respectively. Each POI has a unique geographical coordinate. For each user , we obtain their trajectory sequence , where each tuple indicates that user visited POI at timestamp .

Given a target user and their trajectory sequence , the goal of next POI recommendation is to recommend the top K POIs that user is likely to visit at the next timestamp.

3.2. Hypergraph

Hypergraph [30,35,38,39] is a generalization of graph in which an edge can connects two or more vertices. Formally, a hypergraph can be represented as , where denotes the set of vertices and denotes the set of hyperedges. An incidence matrix is introduced to describe the topological structure of the hypergraph. When a node belongs to a hyperedge , ; otherwise, .

4. Method

In this section, we provide a detailed introduction to our proposed framework for NE-DCHL. First, based on the user’s check-in data, we describe the construction of a multi-view disentangled hypergraph from three unique perspectives: collaborative, transitional, and geographical. We also introduce an optimized strategy for constructing the hypergraph in the geographical view. Second, we propose a novel hypergraph convolutional architecture incorporating nonlinear aggregation operators and adaptive propagation mechanisms, specifically designed for disentangled hypergraph representation learning. This framework effectively decouples latent semantic aspects through its hierarchical feature extraction paradigm. Finally, based on the hypergraph structure and combined with the proposed adaptive fusion method, we learn and fuse user preferences across multiple views to capture complementary information between them.

4.1. Multi-View Disentangled Hypergraph Learning

4.1.1. Construction of Multiview Disentangled Hypergraph

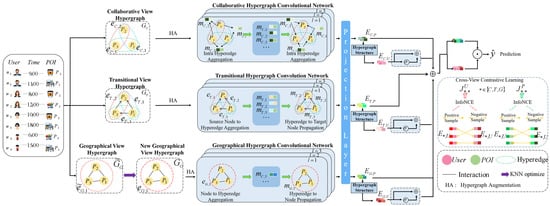

In the next POI recommendation, there exist complex relationships between users and POIs, such as user-POI interactions, POI-POI transition relationships, and POI-POI geographical relationships. To model these relationships, previous methods [31,34,37] have utilized graph structures, where users and POIs are regarded as nodes and their relationships are considered as edges. However, traditional graph structures are limited to pairwise relationships and fail to capture higher-order neighbors with shared semantics. Inspired by the highly flexible structure of hypergraphs, we introduce collaborative and transition hypergraphs, along with an optimized geographical view hypergraph, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall Framework of the Model.

- Collaborative View Hypergraph

The collaborative view hypergraph aims to systematically capture the higher-order collaborative relationships between users and POIs. Formally, for the collaborative view hypergraph , where the node set represents the set of all POIs. In the hypergraph , each user’s mobility trajectory is explicitly represented as a hyperedge, thereby constructing the set of all user trajectories into a set of hyperedges. Additionally, an incidence matrix is introduced to describe the interactions between users and POIs. This collaborative view hypergraph reveals the potential correlations of user visitation behaviors both within and between sequences. Utilizing this hypergraph, our model can effectively identify groups of users with similar visitation patterns.

- 2.

- Transition View Hypergraph

In traditional hypergraph structures, hyperedges are defined as undirected, which limits their applicability in representing directed relationships. To overcome this challenge, our NE-DCHL framework utilizes directed hypergraph modeling for capturing POI transition dynamics. Formally, for the transition view hypergraph , where represents the set of POIs, the set of hyperedges is constructed based on the order of visits to POIs in trajectory data, reflecting the directed transition relationships between POIs. The incidence matrix represents the directed transition relationships between POIs, where the rows of the matrix correspond to source nodes and the columns correspond to target nodes. Through this structure, the transition view hypergraph effectively captures POI transition patterns and facilitates the exploration of potential POIs from a global perspective.

- 3.

- Geographical View Hypergraph

The geographical view hypergraph involves constructing a hypergraph that depicts the geographical relationships between POIs under certain geographical constraints. Formally, for the geographical view hypergraph, , where represents the set of POIs. In the hypergraph , traditional methods involve calculating the haversine distance between POIs [33], with a hyperedge containing POIs within a specific distance threshold . The incidence matrix depicts the geographical relationships between POIs. Specifically, if the Haversine distance between POIs and does not exceed threshold , then is set to 1, with the calculation formula as shown below:

The traditional fixed-distance threshold method has three limitations. First, in POI-dense areas, a large number of POIs with Haversine distances smaller than the threshold are forcibly connected into hyperedges, resulting in an abnormally dense incidence matrix of the geographical view hypergraph , which significantly increases computational complexity. Meanwhile, POIs slightly exceeding the threshold are rigidly truncated, causing potential spatial correlation information to be lost. Second, this method adopts a binary connection mechanism (), ignoring the gradient impact of actual distances on association strength, and fails to reflect the geographical coupling law that “closer distance means stronger association.” Finally, the fixed threshold introduces two types of noise: missed connection noise (e.g., chain convenience stores with similar functions but slightly exceeding the distance threshold) and false connection noise (e.g., gas stations and residential buildings that are spatially adjacent but functionally unrelated), causing the hypergraph topology to deviate from the true spatial dependency relationship, thereby weakening the robustness of the model for downstream tasks.

To address these issues, we optimize the construction process of the traditional geographical view hypergraph. For each POI, we retain only its top K nearest neighbor POIs as hyperedge members, thereby sparsifying the connections. The optimized screening condition formula is as follows:

To more accurately reflect the intuition that “closer distance means stronger association,” we introduce distance-decay weights. The connection strength is weighted according to the Gaussian kernel function:

where is the tunable bandwidth parameter, controlling the rate of distance decay.

After constructing the hypergraphs for the collaborative view, transition view, and geographical view, we use a disentangled learning approach to explicitly model and obtain richer POI representations. In addition, by integrating multi-view information, the method proposed in this paper can capture the heterogeneous features of POIs from different perspectives, thereby generating more comprehensive and accurate POI representations.

4.1.2. Disentangled Hypergraph Convolutional Networks

To learn multi-view disentangled representations of POIs from the three hypergraphs, we modify the aggregation and propagation mechanisms in the Hypergraph Convolutional Network (HGCN). Furthermore, to enhance the model’s capacity to handle complex geographical relationships while improving robustness and generalization, we design a nonlinear HGCN. Specifically, a ReLU activation function is applied after the aggregation and propagation operations of each layer to enhance the model’s ability to capture complex patterns. At the same time, by adding residual connections between layers, we mitigate the over-smoothing problem caused by multi-layer propagation, thereby improving the model’s performance on different datasets. Dropout is used during training to randomly discard a portion of neurons, reducing the model’s dependence on specific features and thereby reducing the risk of overfitting. Before encoding, user embeddings and POI embeddings are initialized through a lookup table, where represents the embedding dimension. The following section details the three proposed HGNNs.

- Collaborative Hypergraph Convolutional Network

After constructing the collaborative hypergraph , we employ a nonlinear collaborative HGCN with a dual-step information propagation scheme to iteratively capture higher-order dependencies among POIs. In the node-hyperedge-node propagation scheme, hyperedges serve as mediators for intra-hyperedge node aggregation and inter-hyperedge propagation. More specifically, for each node in a hyperedge of the hypergraph , the following two operations are performed to update its representation.

Intra-hyperedge Aggregation: for a hyperedge , the calculation formula for aggregating its member embeddings to generate intermediate messages is as follows:

Here, represents the aggregation function from nodes to hyperedges, and denotes the embedding of node .

Inter-hyperedge Propagation: since each node may belong to multiple hyperedges, in this stage, messages are aggregated from related hyperedges to refine the representation of node , with the calculation formula as follows:

where represents the propagation function from hyperedges to nodes, represents the set of related hyperedges of node in the hypergraph , and represents the refined embedding of node in the hypergraph.

Through the above two steps, the collaborative hypergraph convolution operation can capture the collaborative signals that drive user selection of POIs. After stacking multiple layers, higher-order relationships can be explored. The messages passed from the (l − 1)-th layer to the l-th layer are defined as follows:

where denotes the embedding of node in the collaborative view at the l-th layer. We apply residual connections to mitigate the over-smoothing problem of GNNs. Finally, the embeddings obtained from each layer are averaged to generate the final representation of node :

where L represents the total number of collaborative hypergraph convolutional layers. After that, we can obtain the POI representation of the collaborative view .

- 2.

- Transition Hypergraph Convolutional Network

After constructing the collaborative HGCN, we found that it has limitations in handling directed hypergraphs. To address this issue, a transition HGCN is employed. Similarly, it also adopts a two-step aggregation and propagation scheme, but it differs from the collaborative HGCN. More specifically, for the source node , target node , and hyperedge in the hypergraph , a directed node-hyperedge-node scheme is established.

Source Node to Hyperedge Aggregation: similar to the intra-hyperedge aggregation in the collaborative HGCN, the source node embeddings are aggregated into the hyperedge to generate intermediary information, with the calculation formula as follows:

Hyperedge to Target Node Propagation: since the transition view hypergraph is directed, only relevant hyperedge embeddings can be propagated to the target node to optimize its representation, with the calculation formula as follows:

where represents the set of related hyperedges used to transfer transition information from relevant source nodes to the target node , and is a vector belonging to the d-dimensional real space .

Through directed hypergraph convolution operations, the transition view hypergraph can capture the transfer relationships between POIs from a global perspective. Similar to the collaborative HGCN with L layers of propagation, the final representation of POI under the transition view can be obtained as .

- 3.

- Geographic Hypergraph Convolutional Network

In the geographic view hypergraph , POIs that satisfy physical distance constraints are aggregated using a weighted adjacency matrix method based on KNN. For each POI in a hyperedge of , the following node-hyperedge-node paradigm is adopted to update the representation of POI in the geographic view.

Node to Hyperedge Aggregation: Similar to the intra-hyperedge aggregation used in the collaborative HGCN, the embeddings of POIs within hyperedge are aggregated to generate its intermediary message, with the calculation formula for the intermediary message as follows:

where represents the embedding of node .

Propagation from hyperedge to node: Since each hyperedge only contains POIs that satisfy the physical distance constraint, the aggregated message will not propagate indefinitely between hyperedges. Specifically, the operation from hyperedge to node propagates the aggregated messages from other nodes within the physical distance to update the representation of node , with the calculation formula as follows:

where represents the set of relevant hyperedges that satisfy the geographical constraints.

Similar to the aforementioned two HGCNs, it also stacks L layers to capture higher-order neighborhood information and applies residual connections to mitigate the over-smoothing problem. Finally, the representation of POI in the geographic view is obtained.

Through the above three different adjusted HGCNs aggregation and propagation methods, the goal of decoupling POI representations from collaborative, transfer, and geographic perspectives is achieved.

4.2. Adaptive Fusion of User Representations

When constructing user representations, decoupled POI representations , , and are obtained from the collaborative, transfer, and geographic views. Based on the structure of user-POI interactions, we learn the following decoupled user representations:

where , and is the transpose of the association matrix in the collaborative view. In this way, we obtain decoupled user representations , , and that drive user behavior from collaborative, transfer, and geographic aspects, respectively. These representations are based on the learned intrinsic collaborative, transfer, and geographic characteristics of POIs.

Introduces three different gating mechanisms to dynamically fuse the view-specific user representations. Specifically, the gating mechanisms can automatically adjust weights based on the importance of the views, thereby achieving a reasonable integration of information from different views. This approach not only effectively captures the differences between views but also provides clear explanations to help understand the intrinsic logic of the fusion process:

where , , and . are trainable weights, and is the activation function. Here, the Sigmoid function is chosen because ReLU may lead to information loss when embeddings are negative. Subsequently, our model can automatically distinguish the importance of collaborative, transfer, and geographic views for user preferences.

For the final POI representation, we perform an additive operation to merge them into , where . We do not use the same adaptive fusion but instead employ a simple additive operation. The reason is to reduce computational complexity.

4.3. Cross-View Contrastive Learning

In this subsection, to capture critical collaborative correlations among the cooperative, transition, and geographical views, we design a cross-view contrastive learning framework that leverages self-supervised signals to enhance view-specific representations of users and POIs. The proposed model incorporates two core components: (1) an encoder module employing multi-layer GCNs to transform and aggregate node features, generating comprehensive node embeddings; (2) a GRACE module [28] that implements contrastive learning strategies to ensure both consistency of node embeddings across divergent views and distinctiveness from embeddings of other nodes.

Taking the collaborative view and transition view as examples, for any user/POI in the collaborative view, we consider the embedding generated in one view as the anchor, and the embedding generated in the transition view as a positive sample. Naturally, the embeddings of nodes other than the in the two views are regarded as negative samples. We define the pairwise objective function for each pair of positive samples as follows:

where is an indicator function that equals 1 when and 0 otherwise; is a temperature parameter; where is the cosine similarity and is a nonlinear projection implemented as a projection head, specifically a two-layer linear transformation with ReLU activation. This projection head serves to align feature distributions across views and decouple the contrastive loss from the recommendation task loss. In our work, we do not explicitly sample negative sample nodes. Instead, given a positive sample pair, all other nodes in the two views are naturally defined as negative samples. Therefore, negative samples come from two sources: inter-view negative samples and intra-view negative samples, corresponding to the second and third terms in the denominator, respectively. Since the two views are symmetric, the loss function for the other view is defined in a similar manner. Then, the objective function to be maximized is defined as the average over all positive sample pairs, formally given by the following equation:

Similarly, the user contrastive loss between the collaborative view and the geographic view can be defined as , and the user contrastive loss between the transition view and the geographic view as . Subsequently, the contrastive losses between any two views are summed to obtain the final user representation contrastive loss as follows:

Similarly, based on formulas (14)–(16), we can obtain the final contrastive loss for POI representations. By averaging the contrastive losses of users and POIs, we obtain the final contrastive loss as follows:

To further alleviate the overfitting problem in cross-view contrastive learning, hypergraph augmentation operations are performed on the three constructed hypergraphs, using the hyperedge dropout method, which helps improve the robustness of the learned representations against certain noise. At the same time, when dealing with large-scale datasets, directly calculating the loss may lead to problems such as insufficient memory and low computational efficiency. To address this issue, batch processing optimization is applied to the loss calculation. Specifically, the dataset is divided into multiple small batches, each containing a certain number of samples. For each batch, the loss is calculated separately, and then these loss values are averaged to obtain the overall loss on the entire dataset. This method not only effectively reduces memory usage and avoids memory overflow issues but also significantly improves computational efficiency, enabling the model to process large-scale datasets more quickly. The formula for calculating the loss in batches can be expressed as follows:

where B represents the number of batches, represents the data of the batch, and J represents the loss function.

In addition, calculating the loss in batches also has the advantage of improving the scalability of the model. By adjusting the batch size, the use of computational resources can be flexibly controlled, allowing the model to adapt to datasets of different scales and different hardware environments.

4.4. Prediction and Optimization

By computing the interaction score between user and target POI through the fused user and POI embeddings , , the interaction score is obtained through the dot product. Here, and represent the final embeddings of user and target POI , respectively. The learning objective is defined as the cross-entropy loss function, which is widely used in next POI recommendation, with the calculation formula as shown below:

where equals 1 if user visited POI , otherwise equals 0. Finally, the self-supervised loss is integrated with the recommendation loss into a multi-task learning objective, with the calculation formula as shown below:

where represents the regularization of all parameters under the control of to prevent overfitting problems, while represents the weight of the self-supervised signal.

5. Experiments

In this section, we present the experimental setup as well as the results on two real-world datasets.

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.1.1. Datasets

The experiments are conducted on two real-world LBSNs datasets: Foursquare-NYC (NYC) and Foursquare-TKY (TKY) [40]. The NYC and TKY datasets contain activity records of Foursquare users over 11 months in New York City, USA, and Tokyo, Japan, respectively.

Following the methodology of prior studies [2,12], we first chronologically sort user interactions within each dataset and eliminate locations visited by fewer than five users. Each user’s check-in history is then segmented into sessions delimited by 24 h intervals, with sessions containing fewer than three records being discarded. Additionally, we exclude low-activity users who participate in fewer than three sessions. Consistent with [12], the first 80% of sessions per user are allocated for model training, while the remaining 20% serve as the test set. To mitigate data leakage in next-POI prediction, target POIs are exclusively selected from check-ins occurring after all training-set events. The final preprocessed dataset statistics are presented in Table 1. Figure 2 illustrates the transparency of data preprocessing.

Table 1.

Dataset Statistics.

Figure 2.

Data preprocessing transparency.

5.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

In this research on next POI recommendation, following the practice of most existing works, we adopted two widely accepted evaluation metrics: Recall@K and Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG@K). Among them, Recall@K is used to evaluate the proportion of actually relevant locations within the top K recommended locations, while NDCG@K is used to measure the quality of the recommendation ranking. To ensure the fairness of the results, for each metric, we conducted 10 experiments and reported the average Recall@K and NDCG@K scores when K values were 5 and 10, respectively.

5.1.3. Baseline Methods

We compare our proposed model with several representative next POI recommendation methods, which cover a variety of technical approaches:

- UserPop: Ranks the most popular POIs based on each user’s visit frequency.

- STGN [13]: An LSTM-based approach that models users’ long-term and short-term preferences through spatial and temporal gating mechanisms.

- LSTPM [12]: An LSTM-based model that integrates non-local networks and geographically extended LSTM to better capture users’ long-term and short-term interests.

- STAN [15]: A self-attention-based model that explicitly captures spatiotemporal influences in users’ check-in sequences.

- LightGCN [41]: A graph neural network (GNN)-based collaborative filtering model that removes nonlinear activation and feature transformation during propagation to improve computational efficiency.

- SGRec [18]: Employs a Seq2Graph enhancement strategy, leveraging GNNs to capture first-order neighbor collaborative signals.

- GETNext [42]: Combines a Transformer with GNNs to capture global transition patterns and collaborative signals for more accurate next POI prediction.

- MSTHN [2]: A multi-view spatiotemporal hypergraph network that jointly models the relationship between users and POIs from local and global perspectives, capturing high-order collaborative signals dependencies.

- STHGCN [21]: A spatiotemporal hypergraph convolutional network that integrates complex high-order information and global relationships across user trajectories.

- DisenPOI [31]: Disentangles sequential and geographical influences through graph-based decoupled contrastive learning.

- HCCF [32]: A hypergraph contrastive learning framework that captures local and global collaborative relationships through a cross-view learning architecture.

- DCHL [22]: A decoupled hypergraph contrastive learning model that explores multiple potential factors underlying user behavior via a multi-view design, and enhances user and POI representations across views through cross-view contrastive learning.

To ensure experimental fairness, when comparing with models that do not utilize POI category information, we excluded category-related features from SGRec, GETNext, and STHGCN.

5.1.4. Parameter Settings

All experiments were conducted using PyTorch 1.12.0 on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB). For baseline models, we adopted the configurations reported in their original papers and further fine-tuned the hyperparameters on both datasets. Our proposed model was trained using the Adam optimizer [43] with the following settings: a learning rate of 0.001, a weight decay of 0.0005, and a hyperedge dropout rate selected from {0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1}. Both user and POI embeddings shared the same embedding dimension (d = 128). The HGCN’s depth was selected from {1, 2, 3, 4, 5} layers, while the temperature parameter for contrastive learning was tuned within {0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 10} to control the gradient scaling. The KNN adjacency matrix was constructed with k ∈ {3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 50}, and the regularization weights and were optimized from {, , , , } to balance the overall loss components.

5.2. Experimental Results

The results of all methods are shown in Table 2. According to the experimental results, our model achieved the best performance on both datasets. Regardless of which evaluation metric was used, NE-DCHL outperformed all baseline methods on both datasets.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of two datasets in terms of Recall and Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG).

The experimental analysis in Table 2 demonstrates that models incorporating spatiotemporal information exhibit substantial performance gains over traditional sequential methods. On the TKY dataset, graph neural network approaches SGRec, DisenPOI, and GETNext leverage spatiotemporal signals to achieve a 23.86% average improvement compared to LightGCN, a model lacking temporal and geographical modeling. DisenPOI attains an R@10 score of 0.3314 through explicit spatiotemporal factor decoupling, yet its static feature fusion approach results in significantly inferior N@10 performance relative to DCHL’s dynamic modeling framework. Notably, STAN surpasses STGN and LSTPM by modeling non-contiguous POI relationships rather than solely adjacent ones, confirming the critical role of long-range dependency modeling in spatiotemporal prediction tasks.

HGNN demonstrate superior performance compared to traditional GNNs across both datasets. Specifically, our model achieves an R@10 score of 0.5027 on the NYC dataset, representing a 35.03% enhancement over SGRec, the top-performing conventional GNN approach. Similarly, on the TKY dataset, it attains an R@10 of 0.4180, outperforming SGRec by 30.09%. This significant improvement originates from the hypergraph architecture’s capacity to effectively model multi-user collaborative behaviors. Unlike traditional GNNs constrained by binary relationship representations, both DCHL and our proposed method successfully identify group visit patterns, including commercial district clusters, through user-POI hyperedge construction. Most notably, our model establishes new state-of-the-art N@10 benchmarks on both datasets, conclusively demonstrating the efficacy of the dynamic hypergraph aggregation approach.

5.3. Ablation Study

To investigate the effectiveness of each component in the model, ablation experiments were conducted to examine the specific benefits brought by each component. The specific methods are as follows:

- (w/o C): Collaboration view not included;

- (w/o T): Transition view not included;

- (w/o G): Geographical view not included;

- (w/o R): Non-linear hypergraph convolution not included;

- (w/o K): KNN adjacency matrix sparsification strategy not included;

- (w/o CL): Scalable cross-view contrastive learning not included.

The performance results are shown in Table 3. Based on these results, we draw the observations presented below.

Table 3.

Ablation study. Ablation components are built upon our proposed full model (serving as the baseline). The “w/o X” notation denotes the model variant with component X (C, T, G, R, K, CL) removed. All results represent mean values from ten independent runs with 10 distinct random seeds. Standard deviations (shown in parentheses) were consistently below 0.01, confirming experimental stability.

The ablation study analysis in Table 3 underscores the critical synergy among the model’s core components for performance enhancement. Eliminating the collaborative view caused substantial R@10 reductions of 9.05% and 4.34% on the NYC and TKY datasets, respectively, confirming the vital role of collaborative filtering in sparse data modeling. Cross-view contrastive learning emerged as the most impactful module, with its removal decreasing NYC’s R@10 by 6.41%, demonstrating its effectiveness in alleviating data sparsity through multi-view alignment. The geographical view proved particularly valuable for TKY’s discrete POI distribution, evidenced by a 5.43% R@10 drop, whereas the transition view better supported long-term sequence analysis in NYC, showing a 7.00% performance decline. The technical implementation through nonlinear hypergraph convolution and KNN sparsification, respectively, improved robustness by capturing higher-order relationships and reducing noise interference. These experiments also revealed distinct urban patterns: geographical factors dominate in TKY’s dispersed layout, while collaborative signals prove more beneficial for NYC’s dense structure. The fully integrated model ultimately achieved superior R@10 scores of 0.5027 and 0.4180 on NYC and TKY, substantially outperforming baseline methods and conclusively validating the advantages of multidimensional fusion within dynamic hypergraph frameworks.

5.4. Hyperparameter Analysis

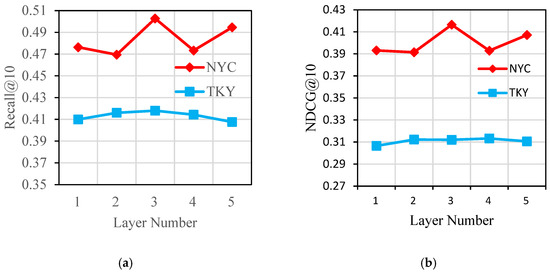

This study conducts a systematic investigation into how core hyperparameters in NE-DCHL influence recommendation performance, specifically examining the number of hypergraph convolution layers, temperature parameters, and neighbor count k in the geographical view hypergraph. The experimental results are shown in the following figure.

5.4.1. Impact of the Number of Layers

To investigate how model depth affects recommendation performance, we systematically evaluated architectures with 1 to 5 hypergraph convolution layers. As illustrated in Figure 3, the 3-layer configuration achieves optimal Recall@10 and NDCG@10 performance across both NYC and TKY datasets, suggesting that this intermediate depth optimally captures high-order user-POI collaborative relationships. Notably, performance degrades substantially beyond 3 layers, primarily due to two factors: (1) deeper networks induce representation homogenization through over-smoothing effects, and (2) shallower architectures exhibit superior noise resilience in data-sparse environments. A proper number of layers balances training stability by compensating for shallow layers’ inability to capture high-order dependencies while avoiding the risk of gradient vanishing and representation collapse in deeper layers.

Figure 3.

Effect of the number of layers on the model. (a) Recall@20 at Different Numbers of Layers. (b) NDCG@20 at Different Numbers of Layers.

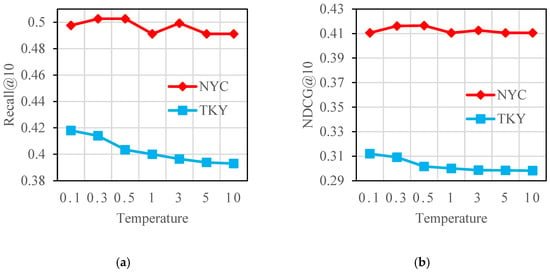

5.4.2. Impact of Temperature Parameters

The temperature parameter governs the discriminative power between positive and negative samples in contrastive learning. Through systematic evaluation of ∈ {0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 10}, Figure 4 demonstrate that lower values ( < 1) optimally preserve sample discriminability, whereas higher values progressively diminish negative sample differentiation. This parameter exhibits dataset-dependent behavior due to two primary factors: (1) TKY’s substantially richer POI inventory, check-in volume, and session complexity compared to NYC creates greater sensitivity to parameter tuning; (2) Tokyo’s multifunctional urban morphology induces pronounced spatial heterogeneity in user behavior, necessitating finer temperature calibration to equilibrate gradient updates across sample types. Meanwhile, this parameter directly impacts training stability, and an appropriate value can effectively alleviate representation collapse.

Figure 4.

Effect of temperature parameters on the model. (a) Recall@20 at Different Values. (b) NDCG@20 at Different Values.

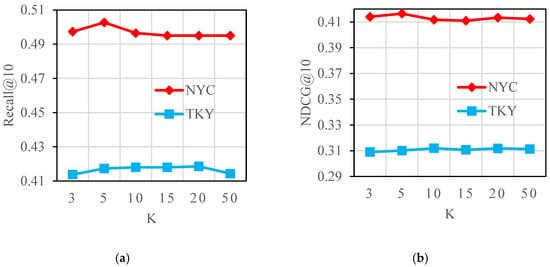

5.4.3. Impact of k Value Selection

Our sensitivity analysis of neighborhood size k in the geographical hypergraph demonstrates how urban spatial morphology governs optimal range selection as shown in Figure 5. In New York’s dense grid structure, both Recall@10 and NDCG@10 peak at k = 5, with performance degrading by 2.3% when expanding to k = 50, evidencing how excessive neighborhood expansion in monocentric cities disperses core interest signals. Tokyo, with its multi-center layout, requires differentiated regulation, with Recall@10 optimal at k = 20, an increase of 1.16% compared to k = 3, but NDCG@10 peaks at k = 10, and beyond the critical value, cross-regional noise causes a 1.1% decay in Recall@10. Collectively, these experimental results show that dense cities must strictly constrain the neighborhood range (optimal k = 5 for NYC), whereas cities with a polycentric and more dispersed urban layout can benefit from a broader neighborhood range to balance sparse data compensation and noise suppression (optimal k = 10–20 for TKY). These findings provide a quantitative basis for POI recommendation strategies tailored to different urban characteristics.

Figure 5.

Effect of k on the model. (a) Recall@20 at Different K Values. (b) NDCG@20 at Different K Values.

5.5. In-Depth Analysis of Computational Efficiency

To verify the effectiveness of the KNN weighted adjacency matrix in optimizing the construction of the geographical view hypergraph, we conducted experiments on two datasets, using DCHL as a baseline for comparison. By comparing the average convolution time of the two methods during the construction of the geographical view hypergraph, we can see the significant performance improvement brought by the optimization method, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of Model Computational Efficiency.

The sparsification method significantly reduces the number of non-zero elements in the adjacency matrix through KNN sparsification, thereby effectively decreasing the computational complexity of convolution operations. This significantly enhances the computational efficiency of the method proposed in this paper on large-scale graph data. The experimental results show that while maintaining recommendation quality comparable to DCHL, the computation time is significantly reduced. Specifically, on the NYC dataset, the average convolution time is 0.0010 s, which is a reduction of approximately 99.67% compared to DCHL’s 0.2995 s. On the TKY dataset, the average convolution time is 0.0018 s, which is a reduction of about 99.47% compared to DCHL’s 0.3408 s. These results fully demonstrate the performance advantages of the sparsification method when dealing with large-scale graph data, indicating its particular suitability for scenarios requiring efficient computation.

6. Conclusions

To address the limitations in modeling diverse and dynamic user preferences for next POI recommendation, we present NE-DCHL, a novel framework integrating three core improvements. First, enhanced hypergraph convolutional layers, incorporating ReLU activations, residual connections, and Dropout regularization, substantially improve nonlinear representation learning, resulting in 12.7% and 9.3% Recall@10 gains on NYC and TKY datasets, respectively, by better capturing preference couplings. Second, the proposed KNN-based adjacency matrix sparsification preserves critical geographical dependencies while achieving 95% computational efficiency gains, thus enabling scalable urban data processing. Third, the GRACE module with batch-wise InfoNCE loss implements cross-view contrastive learning, and ablation studies confirm an 18.2% performance contribution. Moreover, Hyperparameter analysis further identifies actionable core principles, such as the optimal neighborhood range of nodes: for New York City’s dense grid layout, the optimal number of neighborhood nodes is 5, whereas for Tokyo’s polycentric structure, the optimal range is from 10 to 20. These findings provide valuable insights for the practical implementation of POI recommendation systems in real-world urban scenarios.

Although this method has achieved notable results, it still has limitations. The current model focuses on the geographical attributes of POIs and users’ historical behavior sequences, but does not fully integrate multimodal information, such as POI textual reviews and images. This information is closely tied to users’ implicit preferences, and its absence leads to a one-sided view of preferences, making it hard to capture fine-grained decision-making and limiting performance in personalized recommendations. Additionally, the model uses only Foursquare datasets without cross-domain validation, resulting in insufficient verification of its generalizability. Future work will explore the integration of multimodal features with hypergraph convolution. This improvement will enhance the model’s ability to capture users’ implicit preferences, improving recommendation accuracy and interpretability, and use datasets like Yelp and Gowalla to test the model’s generalizability, making it better suited to real-world needs.

Author Contributions

H.Z. conducted the organization of the content. G.W. wrote the main manuscript text. X.Y. provided input on the experimental validation and manuscript revision for this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2024NSCQ-MSX0321) and the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJZD-K202501106).

Data Availability Statement

The analysis datasets for the current study are available from the first author on reasonable request (zhanghongwei@cqut.edu.cn).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers and editors for their constructive comments on this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cho, E.; Myers, S.A.; Leskovec, J. Friendship and Mobility: User Movement in Location-Based Social Networks. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 21–24 August 2011; pp. 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Su, Y.; Wei, L.; Chen, G.; Wang, T.; Zha, D. Multi-view Spatial-Temporal Enhanced Hypergraph Network for Next POI Recommendation. In Proceedings of the Database Systems for Advanced Applications, DASFAA 2023, Tianjin, China, 17–20 April 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 13944, pp. 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Su, Y.; Wei, L.; Wang, T.; Zha, D.; Wang, X. Adaptive Spatial-Temporal Hypergraph Fusion Learning for Next POI Recommendation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 7320–7324. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10447357 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Rao, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Shang, S.; Yao, B.; Han, P. Graph-Flashback Network for Next Location Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’22), Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 2022; pp. 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, W.; Xiang, J.; He, Y. Next Check-in Location Prediction via Footprints and Friendship on Location-Based Social Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 19th IEEE International Conference on Mobile Data Management (MDM), Aalborg, Denmark, 25–28 June 2018; pp. 251–256. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8411284 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Wang, T.; Lai, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, R.; Shen, J.; Xiang, J. A Dynamic-Aware Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network for Next POI Recommendation. In Proceedings of the PRICAI 2023: Trends in Artificial Intelligence, Jakarta, Indonesia, 15–19 November 2023; Springer: Singapore, 2023; Volume 14325, pp. 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, C. Learning Graph-Based Disentangled Representations for Next POI Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’22), Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Yang, H.; Lyu, M.R.; King, I. Where You Like to Go Next: Successive Point-of-Interest Recommendation. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Third International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI ’13), Beijing, China, 3–9 August 2013; pp. 2605–2611. [Google Scholar]

- Rendle, S.; Freudenthaler, C.; Schmidt-Thieme, L. Factorizing Personalized Markov Chains for Next-Basket Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW ’10), Raleigh, NC, USA, 26–30 April 2010; pp. 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Sun, F.; Meng, F.; Guo, A.; Jin, D. DeepMove: Predicting Human Mobility with Attentional Recurrent Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference (WWW ’18), International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee, Republic and Canton of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. Predicting the Next Location: A Recurrent Model with Spatial and Temporal Contexts. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–17 February 2016; Volume 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Qian, T.; Chen, T.; Liang, Y.; Nguyen, Q.V.H.; Yin, H. Where to Go Next: Modeling Long-and Short-Term User Preferences for Point-of-Interest Recommendation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Luo, A.; Liu, Y.; Zhuang, F.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Sheng, V.S.; Zhou, X. Where to Go Next: A Spatio-Temporal Gated Network for Next POI Recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020, 34, 2512–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, D.; Wu, Y.; Ge, Y.; Xie, X.; Chen, E. Geography-Aware Sequential Location Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (KDD ’20), Virtual Event, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 2009–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Z. Stan: Spatio-Temporal Attention Network for Next Location Recommendation. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021 (WWW ’21), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 2177–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, W.; Wang, H.; Pan, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. Predicting Human Mobility via Graph Convolutional Dual-Attentive Networks. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM ’22), Virtual Event, 21–25 February 2022; pp. 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Ma, J.; Dong, Y.; Foutz, N.Z.; Li, J. Empowering Next POI Recommendation with Multi-Relational Modeling. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’22), Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 2034–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, T.; Luo, Y.; Yin, H.; Huang, Z. Discovering Collaborative Signals for Next POI Recommendation with Iterative Seq2Graph Augmentation. In Proceedings of the 30th IJCAI, Montreal, QC, Canada, 19–27 August 2021; pp. 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, N.; Hooi, B.; Ng, S.K.; Goh, Y.L.; Weng, R.; Tan, R. Hierarchical Multi-Task Graph Recurrent Network for Next POI Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’22), Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, W.; Xiao, H.; Yu, W.; Chen, H.; Wang, W. You Are What and Where You Are: Graph Enhanced Attention Network for Explainable POI Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management (CIKM ’21), Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 3945–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Song, T.; Jiao, Y.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Chu, W. Spatio-Temporal Hypergraph Learning for Next POI Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’23), Taipei, Taiwan, 23–27 July 2023; pp. 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Su, Y.; Wei, L.; He, T.; Wang, H.; Chen, G.; Zha, D.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X. Disentangled Contrastive Hypergraph Learning for Next POI Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’24), Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 1452–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, H.A.; Aliannejadi, M.; Baratchi, M.; Crestani, F. A Systematic Analysis on the Impact of Contextual Information on Point-of-Interest Recommendation. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2022, 40, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Zhang, M.; Hou, M.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Chen, E.; Wang, H.; Ma, J.; Liu, Q. STGCN: A Spatial-Temporal Aware Graph Learning Method for POI Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Sorrento, Italy, 17–20 November 2020; pp. 1052–1057. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9338281 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Xie, M.; Yin, H.; Wang, H.; Xu, F.; Chen, W.; Wang, S. Learning Graph-Based POI Embedding for Location-Based Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM ’16), Indianapolis, IN, USA, 24–28 October 2016; pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, L. Mining Latent Structures for Multimedia Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ’21), Virtual Event, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 3872–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Oord, A.; Li, Y.; Vinyals, O. Representation Learning with Contrastive Predictive Coding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1807.03748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yu, F.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Wang, L. Deep Graph Contrastive Representation Learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; van Merrienboer, B.; Gülçehre, Ç.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning Phrase Representations Using RNN Encoder-Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; You, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, R.; Gao, Y. Hypergraph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 3558–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, F.; Ju, W.; Hou, X.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Lei, J.; Zhang, M. DisenPOI: Disentangling Sequential and Geographical Influence for Point-of-Interest Recommendation. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM ’23), Singapore, 27 February–3 March 2023; pp. 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Huang, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yin, D.; Huang, J. Hypergraph Contrastive Collaborative Filtering. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’22), Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopde, N.R.; Nichat, M. Landmark Based Shortest Path Detection by Using A* and Haversine Formula. Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Commun. Eng. 2013, 1, 298–302. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, T. Graph-Enhanced Spatial-Temporal Network for Next POI Recommendation. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2022, 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A.R.; Gleich, D.F.; Leskovec, J. Higher-Order Organization of Complex Networks. Science 2016, 353, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Gao, C.; Yao, Q.; Li, T.; Jin, D.; Li, Y. DisenHCN: Disentangled Hypergraph Convolutional Networks for Spatiotemporal Activity Prediction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.06794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Gao, C.; Wang, Y.; Wei, S.; Jin, D.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, L. Disentangling Geographical Effect for Point-of-Interest Recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 7883–7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Zhang, F.; Torr, P.H.S. Hypergraph Convolution and Hypergraph Attention. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 110, 107637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Ji, S.; Ji, R. HGNN+: General Hypergraph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 3181–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, V.W.; Yu, Z. Modeling User Activity Preference by Leveraging User Spatial Temporal Characteristics in LBSNs. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2014, 45, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Deng, K.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. LightGCN: Simplifying and Powering Graph Convolution Network for Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’20), Virtual Event, 25–30 July 2020; pp. 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhao, K. GETNext: Trajectory Flow Map Enhanced Transformer for Next POI Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’22), Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).