2. Literature Review

Despite a rich tradition linking language, affect, and cognition, few approaches have quantitatively modeled how individuals’ spontaneous word associations relate to self-reported emotional well-being [

16]. The present research study addresses this gap by integrating the Emotional Recall Task (ERT) with a spreading activation framework derived from cognitive network science. This integration allows us to examine whether personal lexical choices, when propagated through a large-scale semantic network, reveal systematic associations with affective self-reports. In doing so, we aim to bridge descriptive linguistic markers of emotion with formal network models of cognitive organization.

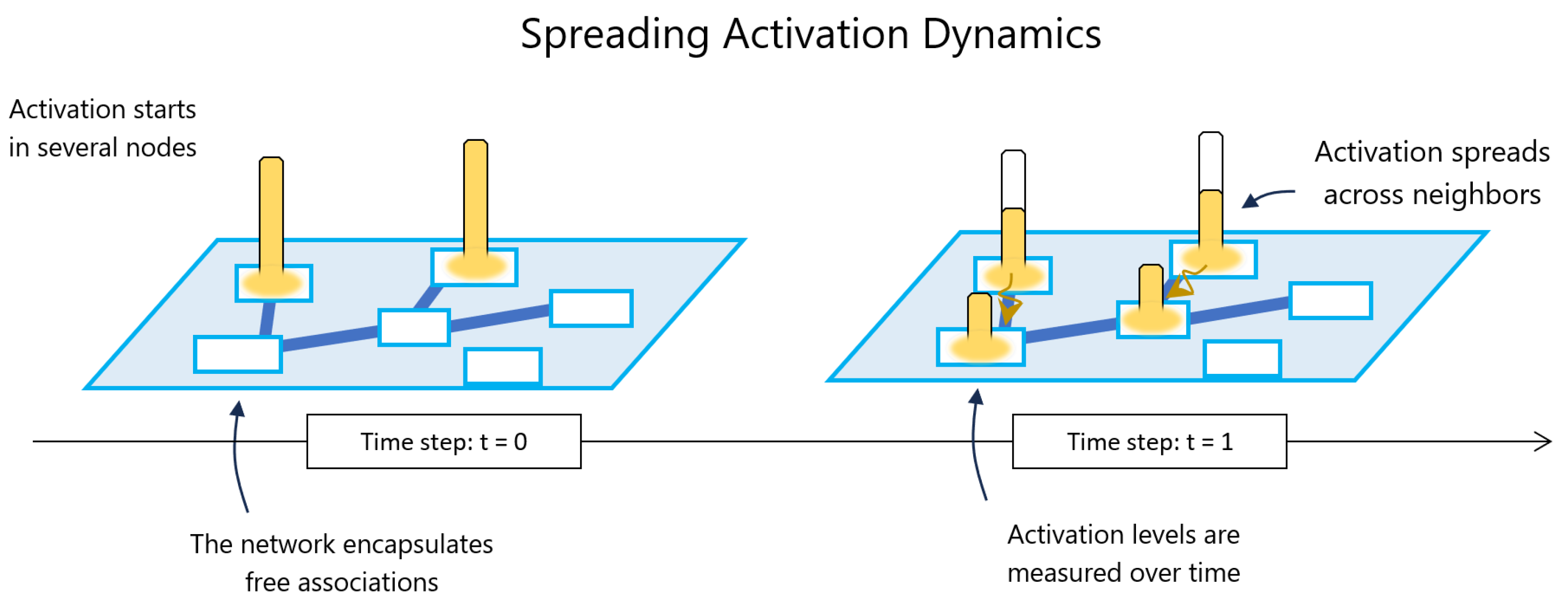

Cognitive networks are representational models of cognition. Cognitive network science models human knowledge as a network of concepts linked by learned associations [

11], enabling the formal study of how structure shapes retrieval and reasoning [

9,

10,

13]. Foundational spreading activation theories [

8,

17] propose that cueing one concept propagates activation along associative links, increasing the accessibility of nearby nodes; these ideas are now operationalized in computational simulations that estimate how activation unfolds over time across a lexical network. Normative free-association resources such as the Small World of Words (SWOW) [

18] provide the backbone topology for such models, while affective lexica with valence–arousal–dominance (VAD) norms [

19] annotate nodes with emotional properties, allowing for joint analyses of semantics and affect. Within this framework, classic network measures (e.g., degree, shortest paths, clustering, and centrality) predict which concepts act as hubs or bridges for activation flow and hence which ideas are most likely to be retrieved under minimal input [

9,

10]. When negative-valence clusters (e.g., anxiety, stress, and depression) are densely interconnected, even mild cues can traverse short associative paths and disproportionately energize these hubs, sustaining recurrent activation loops consistent with rumination and other maladaptive dynamics observed in psychopathology.

Personality traits and mental health. The Big Five personality traits—neuroticism, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and openness [

20]—have long been linked with psychological well-being and increased risk for psychopathology. Among these, the trait of neuroticism is the most consistently associated with greater vulnerability to negative emotions and with an elevated risk of developing anxiety and depressive disorders [

14,

21]. Neurotic individuals tend to simulate past and future problems, thus experiencing negative mood states in the apparent absence of a plausible cause [

22]. From a network science perspective, we can assume that these individuals possess cognitive networks in which concepts linked with negative mood states (e.g., “anxiety” or “depression”) exhibit greater connectivity. This network property could lead to quicker or more persistent activation of anxious or depressive thoughts, characteristic of rumination. Rumination is defined as the repetitive and excessive focus on negative emotions, thoughts, or events [

23]. It has been strongly linked with the development and maintenance of affective disorders such as depression and anxiety [

23] and commonly occurs in other mental disorders. In the context of spreading activation models [

17], rumination can be interpreted as a self-perpetuating activation loop: once a negative concept is triggered (e.g., concepts/nodes like

depression,

anxiety, and

stress), the structure and connectivity of the semantic network determine whether this activation dissipates or initiates a recursive cycle. This occurs because highly central and connected nodes (often representing concepts with high valence for the individual) activate neighboring nodes in a cluster with similar affective valence, reinforcing the same emotional patterns. Moreover, these secondary nodes, once activated, may have fewer connections yet can return activation to the starting node, reinforcing a long-lasting emotional loop characteristic of rumination. Unlike neuroticism, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and openness may serve as protective factors against mental health disorders [

14,

21]. Conscientious individuals have a goal-focused mindset, which helps mitigate rumination. Extraversion correlates with positive affect and sociability, and agreeableness promotes harmonious social interactions, while openness encourages creativity and flexible thinking. Collectively, these behavioral traits and thinking tendencies can foster dense positive clusters of nodes and weaken direct connections with negative concepts, potentially providing protection against stress-related factors. Personality traits are thus studied both as a structural and a behavioral moderator of emotional activation, potentially influencing which concepts are accessible, how strongly they interlink, and how stimuli are elaborated.

Psychometric scales as proxies for mental health assessment. To assess psychological well-being and its relationship with the dynamics of cognitive networks, three validated psychometric scales were employed: the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-21), the Life Satisfaction Scale, and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21). The DASS-21 [

24] is a widely used self-report scale designed to assess the severity of three distinct psychological constructs: depression, anxiety, and stress. Each subscale consists of seven items that capture core symptomatology—depression (e.g., anhedonia and hopelessness), anxiety (e.g., hyperarousal and excessive worry), and stress (e.g., tension and irritability). By conceptualizing these constructs dimensionally, this tool is especially suited to examining how different manifestations of distress operate in associative networks. In this context, we hypothesize that individuals with higher subscale scores on the DASS-21 may also exhibit cognitive networks with denser and more interconnected negative associations among nodes representing depression, stress, and anxiety, much like those observed in other studies on math anxiety [

10].

Life Satisfaction Scale. The Life Satisfaction Scale [

25] measures global well-being by assessing an individual’s overall perception of life quality. The scale consists of five items that evaluate the extent to which individuals perceive their lives as fulfilling and meaningful; unlike the DASS-21, this scale provides a cognitive evaluation of well-being, focusing on the presence or absence of positive self-perception. In cognitive networks, individuals reporting greater life satisfaction may exhibit a network structure in which positive concepts are more central or more densely clustered with other positive concepts, as found in past studies using the Emotional Recall Task [

16].

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). The PANAS [

26] is a psychometric scale that differentiates between positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA). The PA subscale measures the frequency with which an individual experiences positive states (such as attention, determination, and enthusiasm), while the NA subscale captures distress-related emotions such as fear, hostility, and guilt. From a network science perspective, high NA scores could be linked with stronger and more persistent activation of negative semantic nodes, which in turn could reinforce distress, as found in past studies using the Emotional Recall Task [

16].

The Emotional Recall Task (ERT). The ERT is a free-association paradigm designed to capture how individuals spontaneously retrieve and verbalize emotional experiences [

27]. In its standard form, participants are asked to generate a fixed number of words—typically around ten—that describe how they have felt over a recent period (e.g., the past week or month). These self-reported words are then analyzed in terms of their affective properties (such as valence, arousal, and dominance) and their position within normative lexical networks. By mapping recalled words onto semantic networks, the ERT provides a window into the accessibility of emotion-laden concepts and how patterns of recall may reflect underlying psychological states such as stress, anxiety, or depression. This approach has been shown to link individual differences in recall with validated psychometric measures, making it a useful tool for exploring the relationships among emotional memory, well-being, and personality [

16]. Throughout this work, we interpret ERT-derived activation as a property of lexical–semantic propagation and its association with self-reported affect and well-being. Consistent with past research [

16], we do not make claims regarding clinical status or diagnosis.

4. Materials and Methods

For Study 1, five distinct datasets were employed to examine the associations between words generated in the Emotional Recall Task and participants’ psychometric outcomes as measured by the PANAS, DASS-21, and Life Satisfaction scales. Specifically, these datasets included two collections of human participant data, sourced from previous studies [

16,

27,

30], and three datasets of LLM-simulated artificial participants—GPT-4, Claude Haiku, and Anthropic Opus. This diversity in sources enables the comparison of association patterns across different populations and allows for the assessment of how closely artificial models reflect human-like representations of emotion and well-being.

For Study 2, we utilized data from a large-scale online survey conducted in the United States between May and August 2024, collected and publicly shared on an Open Science Repository by De Duro and colleagues [

30]. The survey was administered to a sample of 1000 adult participants, who completed first a brief demographic questionnaire and then a series of psychometric assessments. Personality traits were measured using the IPIP-NEO Inventory (short form) [

31], which evaluates neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness through five items per trait. After completing the scale, participants took part in the Emotional Recall Task (ERT), in which they were asked to freely generate words describing how they had felt in recent weeks. The resulting data were used to construct individual activation trajectories, which were then analyzed to examine relationships between specific personality profiles and the activation strength of nodes associated with mental distress.

Human participant datasets. Two datasets were used to analyze the relationship between emotional word associations and psychological states in human subjects. The first dataset, derived from a study by Li et al. [

27], contains data from 200 native English speakers recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk. Participants provided ten emotional words describing their feelings over the past month, each accompanied by a self-rated frequency of experience, a valence rating (1–9 scale from unpleasant to pleasant), and an arousal rating (1–9 scale from calm to excited). These responses allowed for the computation of a valence–arousal emotional profile for each participant. After completing the emotional recall task, participants were administered several psychometric instruments: the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [

26], the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) [

24], and the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) [

25].

The second human dataset consists of Emotional Recall Task responses from a larger sample of 1000 individuals, collected by De Duro [

30] to validate the association between personality traits and trust in LLMs using free-recall results. This dataset contains personality trait data (the IPIP-NEO questionnaire for personality traits [

32]) and includes broader indicators of emotional and psychological functioning, allowing for the generalization of activation results to a larger human sample. This dataset was used in both Studies 1 and 2.

Artificial participant datasets. We analyzed outputs from three large language models (LLMs): GPT-4 (OpenAI, 04/2024 release), Claude Haiku 3.5 (Anthropic, 10/2024 release), and Claude Opus 3 (Anthropic, 03/2024 release). Each model was accessed via its respective API under standard temperature and sampling conditions (temperature = 0.7). For each model, 200 independent pseudo-participants were generated using unique random seeds. Each pseudo-participant received the full Emotional Recall Task (ERT) prompt, followed by item-level questionnaire prompts for the DASS-21, PANAS, and SWLS. Model outputs were parsed and scored according to the original scale guidelines. These simulations provide text-based, reproducible responses for structural comparison with human data and do not imply the presence of self-reported mental or affective states.

For each model, artificial profiles were generated using a fixed, standardized prompt designed to elicit emotionally relevant content and simulate responses to psychometric questionnaires. All LLMs were presented with the complete text of each questionnaire item—identical to what human participants received—and were asked to select or generate a Likert-style response for each item. The model-generated responses were then parsed and scored using the same procedures applied to human data. Importantly, these outputs are treated purely as text-based data derived from the models’ linguistic probability distributions and are not interpreted as self-reports or reflections of internal mental states (see

Section 6).

Each large language model (LLM) received the full text of every questionnaire item individually. Specifically, the DASS-21, PANAS, and Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) were administered in their original formats, with each item and its Likert-style options presented sequentially to the model. The prompt instructed the model to select or generate one response per item (e.g., 1–5 or 1–7 scale, depending on the instrument). For each LLM (GPT-4, Claude Haiku, and Claude Opus), 200 independent pseudo-participants were generated using distinct random seeds under fixed sampling conditions (temperature = 0.7 and top-p = 0.9). The numerical responses were parsed and scored using the official scoring keys for each questionnaire, yielding total and subscale scores structurally equivalent to those obtained from human participants. It is essential to note that the LLM questionnaire scores reported here do not possess psychometric validity in the conventional sense. Although the administration and scoring procedures were identical to those used with human participants, the resulting values reflect probabilistic text generation tendencies rather than subjective introspection. Consequently, these data should be understood as linguistic artifacts that approximate the statistical structure of self-report scales, not as indicators of genuine emotion, personality, or well-being within the models. The prompt used for LLM generation was the following:

Impersonate a [x] years old [male/female/person].

Please use 10 English words to describe feelings you have experienced during the past month. Reply only with 10 words separated by a comma.

Please read each numbered statement and indicate how much the statement applied to you over the past week. The rating scale is as follows: 0 indicates it did not apply to you at all, 1 indicates it applied to you to some degree, or some of the time, 2 indicates it applied to you to a considerable degree or a good part of time, 3 indicates it applied to you very much or most of the time. Reply only with the vector number corresponding to your answers.

[Statements from the psychometric questionnaire y are listed.]

Repeat the two tasks independently [z] times.

Here,

x represented an age value and ranged so as to match the age ranges in TILLMI by De Duro and colleagues [

30];

y was a questionnaire among DASS-21, Life Satisfaction, and PANAS; and

z controlled the number of repetitions, allowing the task to be performed ten times to facilitate simulations. Each LLM was tasked with independently generating hundreds of artificial participants by repeating the prompt across different fictional profiles. For each simulated participant, ten emotional words and full psychometric vectors were collected. These data were treated identically to those of human participants in subsequent analyses, allowing for a direct comparison of emotional word associations and activation dynamics across human- and LLM-generated datasets. We excluded the IPIP-NEO Inventory from the LLM simulations because the current literature indicates that LLMs without explicit prompting instructions might not possess clear, reliable, or well-specified personality traits [

33,

34].

This design enabled us to assess the representational fidelity of LLMs in capturing emotional constructs and their relationship with mental health indicators. Furthermore, the use of three different models allowed for the identification of model-specific biases and performance differences in reproducing human-like semantic associations. All LLM outputs are treated strictly as text-based samples generated from probabilistic language models. They are not interpreted as self-reports or indicators of internal mental states, and any human–LLM comparison is framed exclusively as a comparison of structural activation patterns in text, not of affect or cognition.

4.3. Spreading Activation Model Implementation

The simulation framework implemented with SpreadPy [

10] was designed to trace the semantic activation of the emotional concepts of

stress,

anxiety, and

depression within a cognitive network following the recall of emotional states. Initially, all ten emotional words recalled by each participant from the ERT data were simultaneously activated. Then, spreading activation was run to simulate how other associated concepts mediated the flow of activation across the cognitive network of free associations, i.e., memory recall patterns. Spreading activation was computed on a

human-derived associative network (SWOW-EN). Consequently, model behavior reflects diffusion within this empirically constructed lexical–semantic structure. Inferences, therefore, pertain to propagation processes inside this network and align with established findings from prior research [

9,

10] linking spreading activation to the recall and processing of concepts in memory.

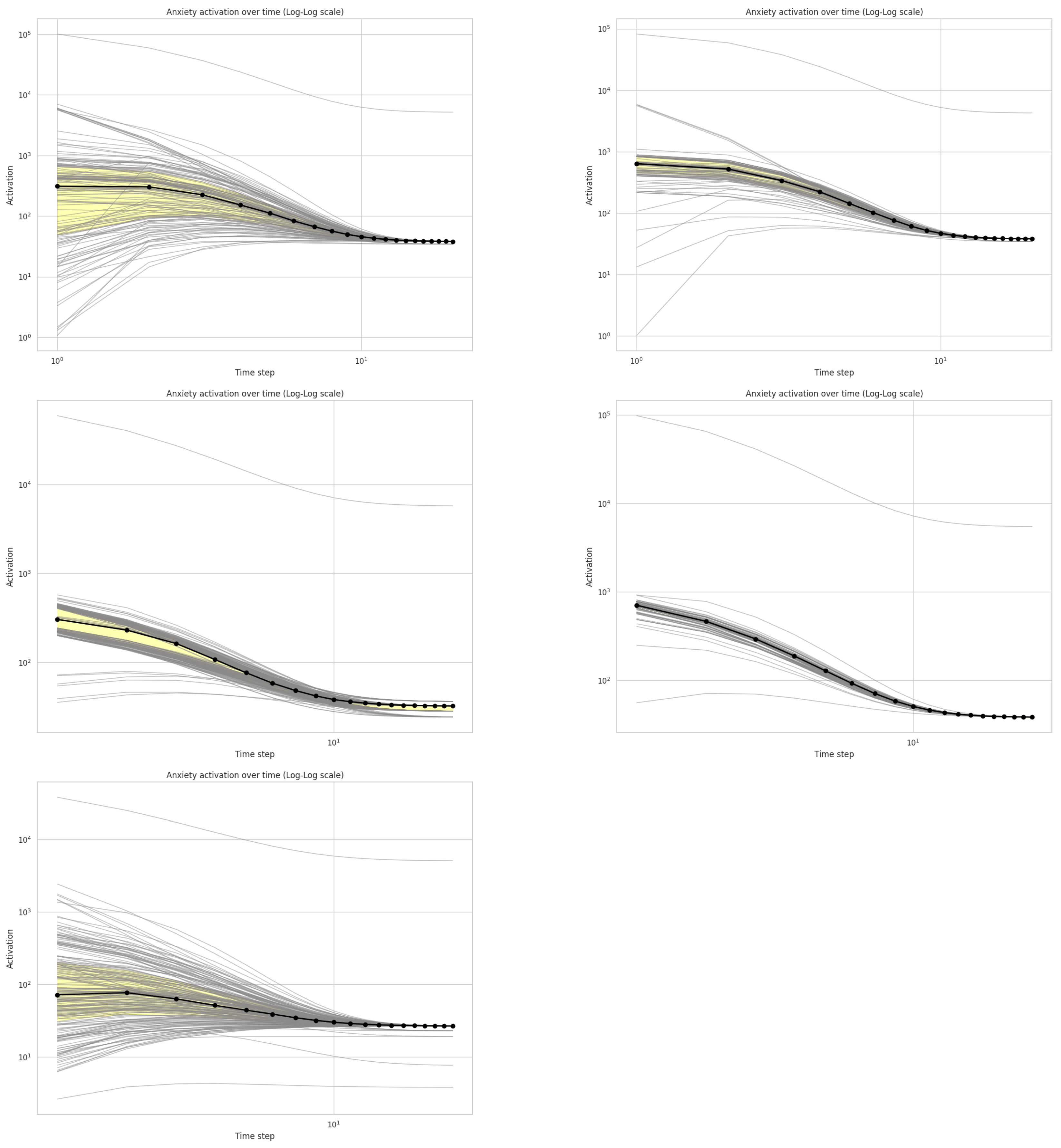

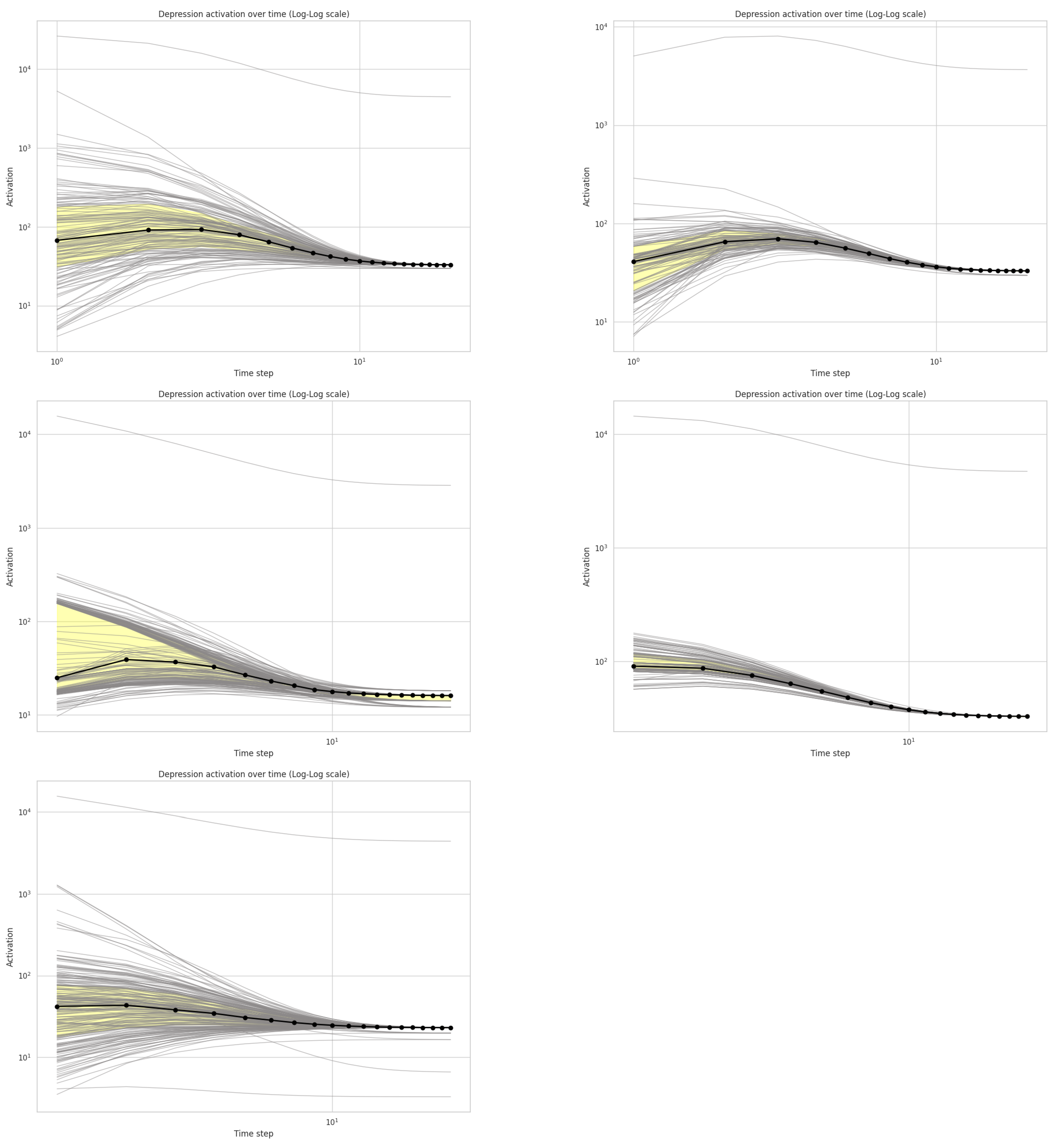

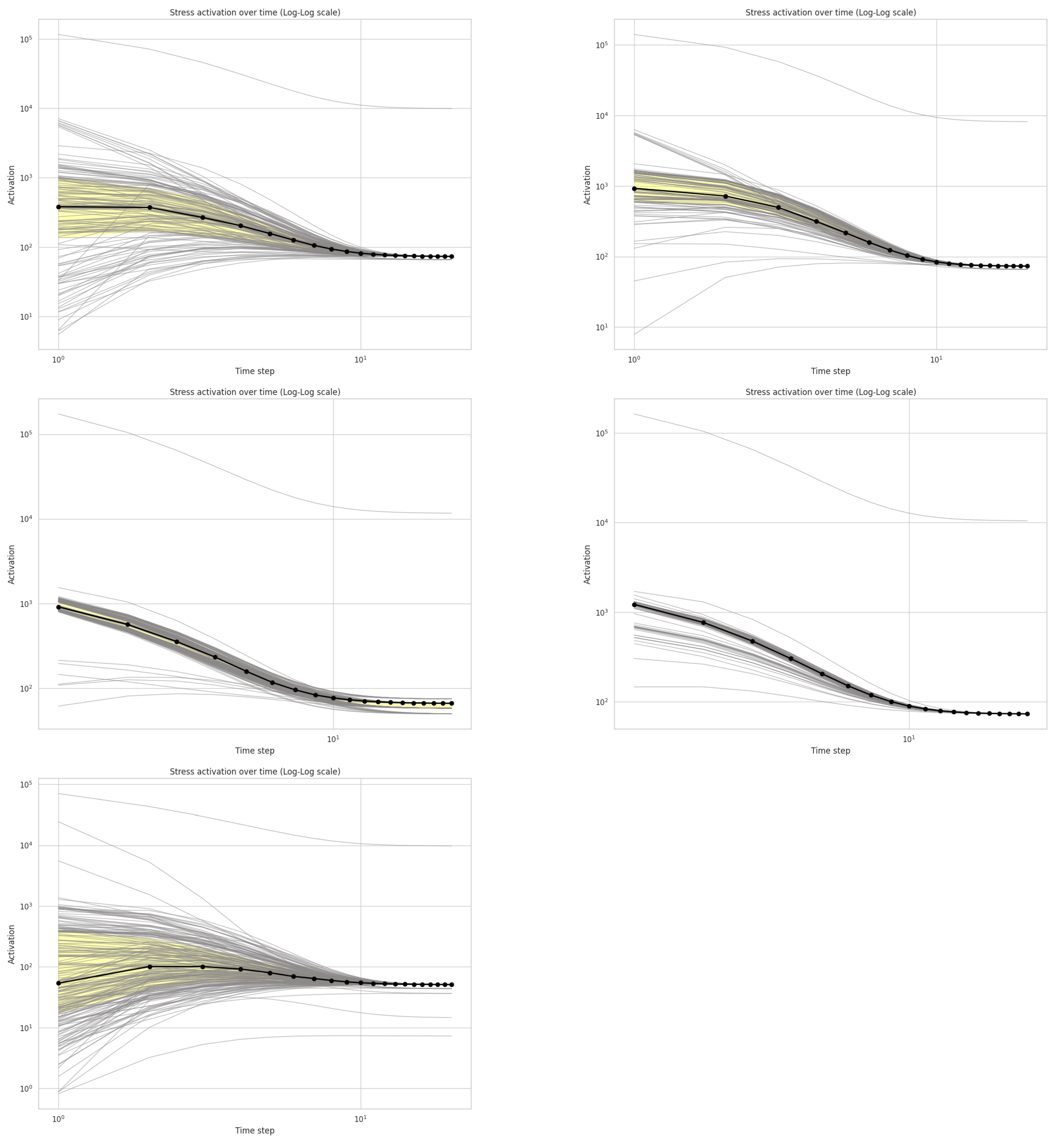

This approach allowed for the observation of the total activation level achieved by a given individual for a target concept related to mental health, i.e., one among “anxiety,” “stress,” and “depression.” In other words, the analysis aimed to determine how individual differences in self-reported emotions—and, in the case of the first dataset, psychological profiles—influenced the dynamics of semantic activation toward negative emotional concepts.

For the sake of simplicity, all analyses were performed using spreading activation diffusion on the unweighted network of free associations derived from SWOW-EN. Edge weights were ignored because their cognitive interpretation is ambiguous: a stronger association could in principle either amplify activation transfer (if interpreted as associative strength) or, conversely, act as a more saturated channel that reduces further spreading. To avoid introducing such theoretical uncertainty, we adopted a binary (unweighted) adjacency structure, where activation spreads uniformly along all outgoing links. Step counts were selected to be long enough for activation peaks to emerge in the time series and for target nodes to reach stationary levels. Empirically, runs of 100, 200, and 400 steps produced equivalent activation profiles. For brevity, we report results for the 200-step runs, as they capture the same asymptotic dynamics. The retention parameter was fixed at , meaning that each node retained half of the activation it received on first arrival and diffused the remaining half to its outgoing neighbors. This setting provides a cognitive compromise between the influence of network topology and the temporal order of activation propagation, ensuring that spreading dynamics remain sensitive both to structural connectivity and to initial lexical activation.

In Study 2, the spreading activation framework described in Study 1 was applied to examine the relationship between personality traits and semantic activation dynamics. The goal was to assess whether individual differences in traits such as neuroticism, conscientiousness, or extraversion influenced semantic activation toward emotionally salient concepts like stress, anxiety, and depression following word recall. As in Study 1, participants’ recalled ERT words served as simultaneous activation inputs in the network, and activation levels for each of the three target nodes were tracked over 200 computational time steps.

6. Discussion

This paper examined the relationship between the results from the Emotional Recall Task (ERT) and mental health. By applying the spreading activation model to word-pair lists generated through the ERT, we hypothesized that individuals scoring higher on mental health scales (e.g., DASS-21) and those with higher neuroticism traits would exhibit stronger activation peaks of “cognitive energy” following the initial activation of nodes associated with mental distress (e.g., stress, depression, and anxiety). The findings support these hypotheses, revealing stronger activation peaks in these groups and comparable results across human participants and LLMs in terms of the relationship between mental health scale scores and the word pairs generated from the ERT. These results offer new insights into the structure and functioning of emotional memory and its relationship with mental health.

While the same questionnaires and prompts were administered to LLMs and human participants, the resulting scores represent simulated, text-based outputs rather than introspective reports. Accordingly, our comparisons reflect structural similarities in linguistic activation patterns, not shared affective or cognitive processes. This distinction is further clarified in our review of both studies’ results.

Study 1 focused on the link between the word pairs generated from the ERT and scores on the psychometric scales PANAS, DASS-21, and Life Satisfaction. We examined the correlations in both human participants and LLMs (Haiku, Opus, and GPT-4) by generating simulated participants. This approach allowed us to investigate whether relationships exist between psychometric scales and ERT responses and to what extent these associations correspond to clinical indicators through simulations applied to ERT-derived data and psychometric scale scores.

Study 1 also revealed recurrent patterns in activation trajectories among negative concepts, particularly in participants with higher distress scores. These loops likely reflect ruminative circuits present in individuals’ cognitive structures, in which activation moves cyclically from one negative concept to another. This quantitative pattern indicates the presence of semantic closures within cognitive networks, potentially giving rise to negative activation zones where activation becomes self-sustaining and confined, limiting transitions to other conceptual clusters. This structure is not only consistent with models of rumination that sustain negative emotional states and affective disorders but also aligns with the “attractor states” theory proposed to study dynamic systems and applied to psychology. According to this theory, certain psychological states, thoughts, and behaviors become stable over time through repeated reinforcement [

37]. Similarly, negative clusters are automatically activated and reinforced, and this lexical activation generalizes across multiple contexts over time, maintaining negative emotional states and thoughts and even contributing to resistance to change or treatment in mental health disorders.

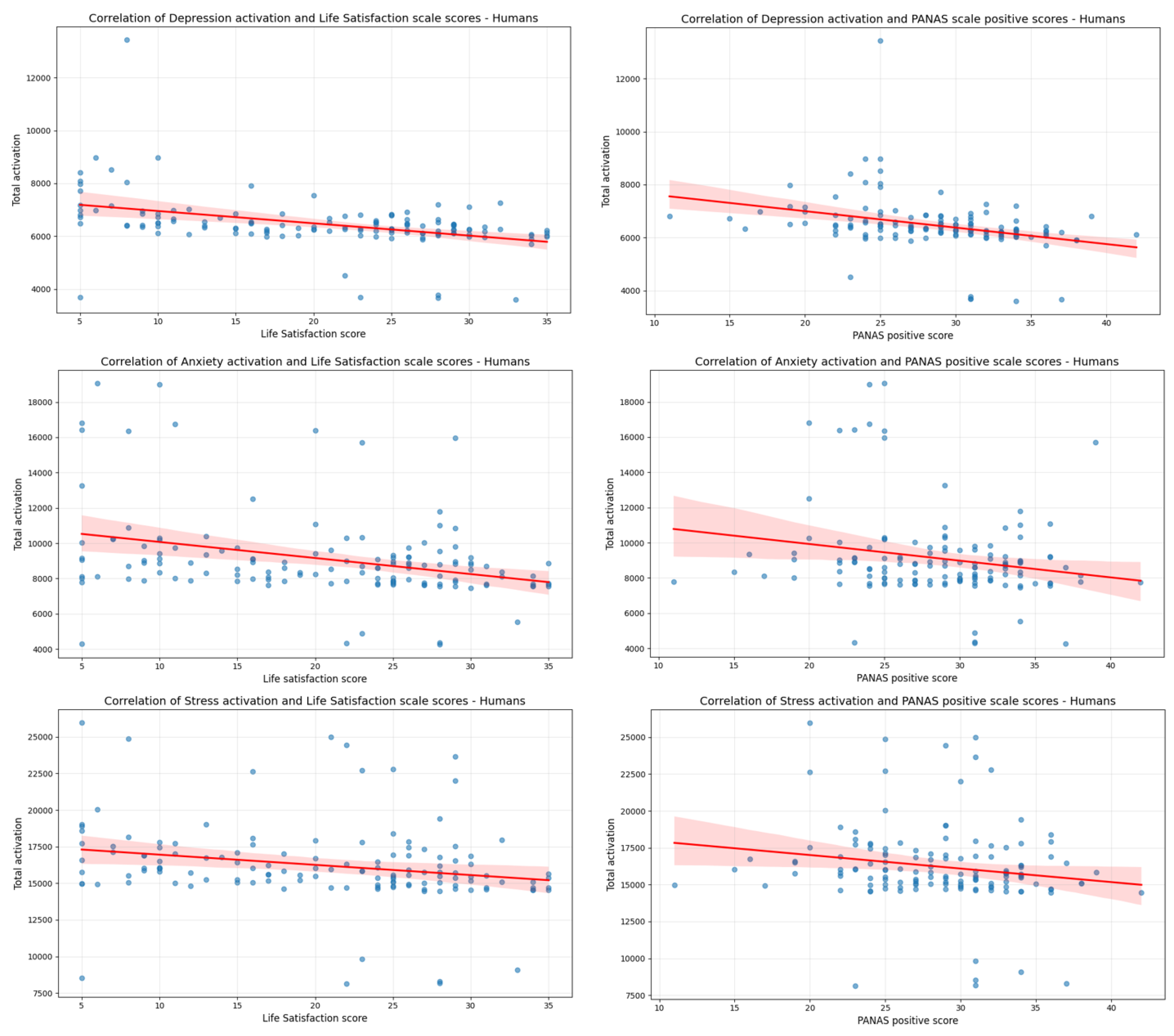

Additionally, Study 1 aimed to determine whether LLMs are able to mirror the same emotional and mnemonic dynamics observed in humans. The results demonstrated that the associations emerging from the ERT in humans positively correlated with scores on psychometric scales. Participants showing higher and faster activation peaks following word recall also scored higher on scales measuring negative affect (such as the DASS-21 and PANAS Negative) and lower on scales measuring positive affect (such as the Life Satisfaction Scale and PANAS Positive). As shown in previous studies [

1], LLMs exhibited variable performance: GPT-4 produced the most human-like results, though with lower activation peaks and less variability among simulated participants. Haiku and Opus, on the other hand, showed weaker and statistically nonsignificant correlations between ERT-generated activation levels and the scores of simulated participants across the different scales.

The significant GPT-4 correlations for

anxiety and

stress, but not for

depression, likely reflect differences in the lexical and corpus-based representations of these constructs. As shown by the SWOW-EN network used in past studies [

35],

stress and

anxiety occupy highly connected, polysemous neighborhoods spanning work, academic, and physiological contexts. In contrast,

depression tends to appear within more specialized or clinical discourse, forming a narrower and less densely connected subnetwork. Consequently, GPT-4’s activation diffusion patterns may mirror the structure of common affective vocabulary but do not extend to conceptually deeper or less frequent terms associated with depressive experience.

The findings from Study 1 indicate that lexical recall patterns, analyzed through the lens of associative networks and their cognitive activation dynamics, can be successfully compared with scales designed to assess mental distress (such as the DASS-21, PANAS, and Life Satisfaction Scale), with cognitive activation toward words indicating emotional distress (such as

depression,

anxiety, and

stress) varying linearly with the scores obtained on these scales. This association confirms that emotional states are tightly linked with lexical memory access, aligning with previous research showing that negative emotions bias memory recall and information processing [

4,

6]. Individuals with higher DASS-21 Anxiety, Depression, or Stress subscale scores exhibited significantly stronger, faster, and more persistent activation of negative concepts. These distress-concept activation patterns suggest that emotional recall, assessed through free associations, can identify mental distress and is sensitive to the cognitive changes in thought patterns found in mental disorders [

38,

39].

Study 2 explored the associations between the Big Five personality traits and the activation of negative emotional concepts—specifically

anxiety,

stress, and

depression—during spreading activation simulations in cognitive semantic networks. The results revealed that high neuroticism scores correlated significantly and positively with increased activation of negative concepts, particularly

depression, while high extraversion scores correlated negatively with depression activation. These results are consistent with the psychological literature identifying neuroticism as a key vulnerability factor for affective disorders [

40,

41] and extraversion as a potential protective trait against negative affective states [

42]. These findings also extend theoretical perspectives in psychology, suggesting that lexical recall patterns [

9,

10,

28] could be integrated into assessments of at-risk individuals; high centrality scores for

anxiety or

depression or elevated activation around specific nodes may signal a neuroticism-related cognitive profile associated with greater emotional vulnerability.

Importantly, the personality effects observed in Study 2 converge with the affective associations identified in Study 1. Neuroticism has long been linked with greater negative emotionality, rumination, and vulnerability to anxiety and depression [

43]. Individuals scoring higher in neuroticism exhibited stronger activation of depression- and anxiety-related nodes. This pattern parallels the heightened activation toward negative-valence concepts observed among participants reporting higher DASS-21 distress and lower life satisfaction. In contrast, extraversion represents a broad disposition associated with positive affectivity, approach motivation, and social engagement [

21]. This trait predicted weaker activation in negative-emotion regions, mirroring the attenuated activation observed among participants with higher PANAS Positive Affect scores. Taken together, these converging findings suggest that the spreading activation dynamics derived from the Emotional Recall Task [

27] capture a shared lexical–affective organization underlying both transient states of well-being and enduring personality dispositions [

44].

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Importantly, our outcomes represent correlations with self-reported scales and do not constitute clinical diagnoses. LLM outputs are simulated textual responses without psychological states, and comparisons with human data are structural only. Moreover, all inferences are conditioned on a human-derived association network; thus, insights reflect diffusion over that structure rather than direct claims about emotional memory mechanisms. This approach entails several important limitations that must be acknowledged. First, while statistically significant, the correlations found were modest and should be interpreted cautiously; their effect sizes suggest that personality is merely one of many factors influencing semantic activation and individual variability remains high. Second, the Emotional Recall Task [

27] itself may be more sensitive to emotional states than traits, introducing noise into personality associations. While neuroticism is quite the stable trait [

50], the activation of words concerning symptoms or negative concepts in one session may reflect momentary distress rather than trait-like tendencies. Therefore, multiple results over time from the same individuals would be necessary to better identify which results can be linked with personality traits and which with mental state influences. Third, as stated above, the link between mental health and personality traits is still unclear. While, in the literature, some patterns linking different personality traits with attitudes [

51], thought patterns, and emotional styles have already emerged, researchers speak of tendencies rather than clear, direct associations. Finally, although this study links personality types with semantic activation patterns, it does not examine the mechanisms through which this link occurs. Future studies could integrate measures of rumination [

52] and other cognitive styles, such as mind wandering [

47], to better specify these mediators and measure their impact on recall associations.

The strength of the correlations between activation and distress as measured by scales further highlights the potential of using network-based tools in psychological assessment.

A major consideration emerging from this work concerns whether LLMs can effectively simulate patients with psychiatric symptoms. Despite LLMs being able to reproduce psycholinguistic data with some effectiveness [

53], the question of psychiatric symptoms is far more complex. Here, LLMs were able to partially generate responses that activated the same negative concepts targeted in human participants. However, the depth and variability of these activations diverged significantly. As described earlier, GPT-4 showed moderate alignment with human-like activation paths, particularly for the

stress node, suggesting some capacity of the model to mimic emotional associations. However, its inconsistencies in correlating with

depression or

anxiety across different models reveal a ceiling effect in its ability to simulate distress dynamics. Nevertheless, there is growing evidence indicating that LLMs, when prompted appropriately, can mirror certain styles of thought [

2,

3,

53] and, importantly, specific emotional tones. Both CounseLLMe by De Duro and colleagues [

30] and recent work by Wang and colleagues [

54] demonstrate that GPT-generated patient narratives and interactions can effectively reproduce the communicative and emotional characteristics of real patients when guided with clinically relevant prompts. These results suggest that while the internal processes of LLMs are not rooted in personal experience, their training on emotionally charged corpora and patient dialogues allows them to reconstruct the form of emotional expression found in humans. Therefore, although the underlying mechanisms are different, the outputs produced by LLMs under certain conditions resemble those of human patients.

This opens promising directions for future work, positioning LLMs as a potentially valuable addition to clinical research and practice [

55,

56]. By embedding LLMs into therapeutic simulations for mental health trainees or diagnostic interviews, practitioners could explore differential emotional responses, identify linguistic markers of distress, and test hypotheses about psychopathology dynamics—provided that their limitations are clearly recognized [

57].