1. Introduction

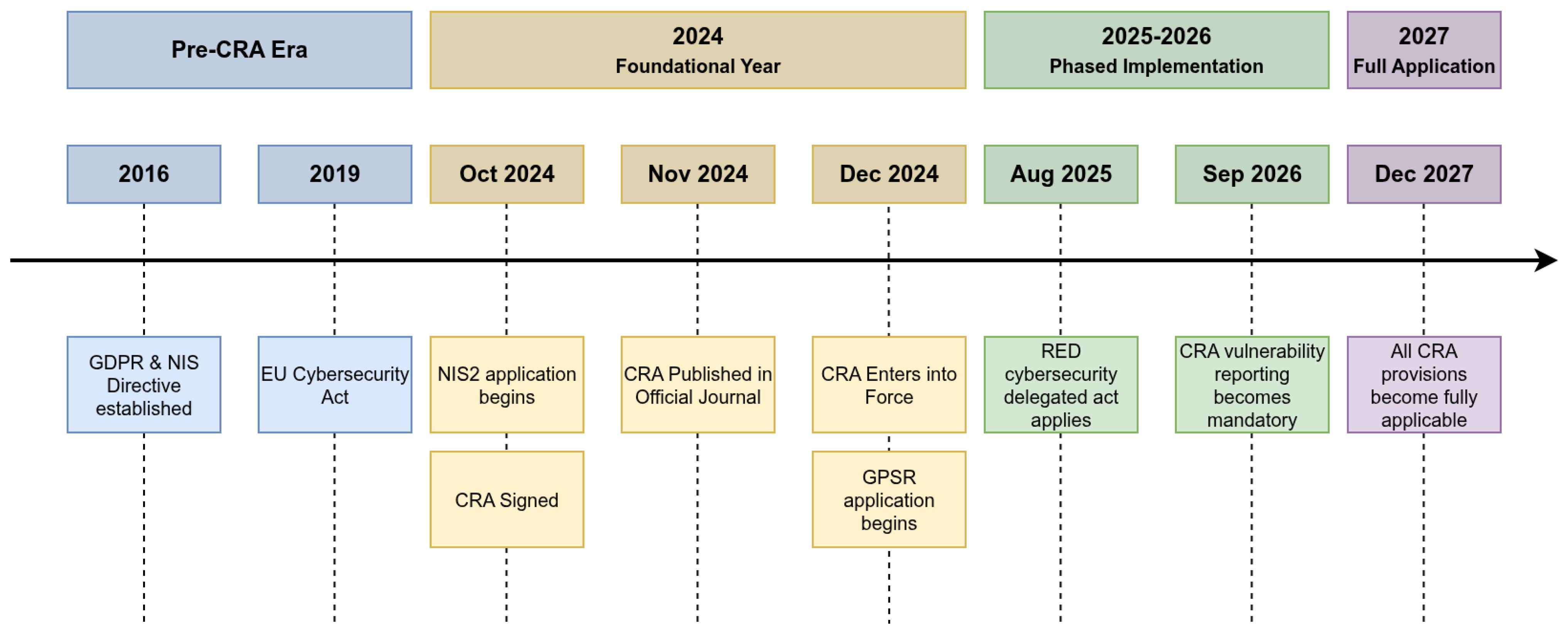

The European Union’s Cyber Resilience Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/2847, or the CRA) officially came into force on 10 December 2024 following its signing on 23 October and publication on 20 November of that year [

1]. While its main provisions will become fully applicable from 11 December 2027, it is crucial to recognize that the regulation introduces a phased timeline; for instance, the mandatory reporting of security vulnerabilities will take effect as early as September 2026. The act establishes a baseline for cybersecurity for all products with digital elements (PDEs) placed on the market across the European Economic Area, with particular relevance for the Internet of Things (IoT). The intent is clear: security must be an intrinsic property of connected products throughout their entire lifecycle, not merely an afterthought.

The expansion of the IoT has been striking. Figures often cited—based on Statista’s series—show around 11.7 billion IoT devices in 2020 and a projection of roughly 30.9 billion by 2025 [

2]; more recent market trackers (e.g., IoT Analytics) revise the 2025 expectations downward to ∼27 billion [

3]. This illustrates the sheer scale of deployment across domestic, industrial, and urban environments, widening the attack surface and increasing users’ exposure to risk, stretching the limits of the existing security arrangements.

Before the CRA, regulation of cybersecurity in connected environments was anchored in instruments such as the Network and Information Systems Directive (NIS) (EU 2016/1148) [

4], the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (EU 2016/679) [

5], and the EU Cybersecurity Act (Regulation (EU) 2019/881) [

6]. While these laid important foundations—risk management, resilience, and trust services—they did not impose detailed enforceable obligations for security by design and by default, mandate secure automatic updates, or set strict timelines for reporting vulnerabilities and incidents. Closely related developments include the Radio Equipment Directive (RED) [

7] and its cybersecurity delegated act [

8], as well as the European Common Criteria-based certification scheme (EUCC) [

9].

The CRA introduces a step change. It requires risk assessment from the earliest design stages, continuous vulnerability testing, secure automatic update mechanisms, the generation and maintenance of a machine-readable Software Bill of Materials (SBOM), and time-bound notifications of vulnerabilities and incidents to competent authorities and end-users. In consequence, practical guidance is needed that goes beyond legal exposition.

This study proposes a CRA compliance framework: a pragmatic methodology to guide IoT manufacturers from initial assessment to full compliance. To this end, this work makes three contributions. First, it introduces a transparent legal-to-engineering methodology that converts CRA provisions into atomic lifecycle-mapped requirements with end-to-end traceability. Second, it operationalizes a quantitative rating tree, deriving defensible domain weights via the AHP and verifying judgment consistency. Third, it provides a reproducible evidence rubric and aggregation formula that yield auditable readiness scores, demonstrated in the TRUEDATA case. Based on these contributions, this article pursues the following objectives:

To analyze the essential requirements of the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA), positioning the CRA within the wider European regulatory fabric (including NIS2, the Radio Equipment Directive—RED [

7], the GDPR, and the EU Cybersecurity Act/EUCC) and highlighting what materially changes for IoT manufacturers.

To formalize and detail a two-phase methodology. Phase 1 consists of a systematic process for extracting, normalizing, and mapping legal requirements from the CRA onto the Development, Security, and Operations (DevSecOps) lifecycle. Phase 2 introduces a quantitative assessment model, using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), to derive consistent risk-informed weights for compliance domains and enable a structured evaluation of readiness.

To demonstrate practical feasibility through a site-agnostic case study in the TRUEDATA project, including a rating-tree evaluation and a balanced radar profile of control effectiveness.

To identify the principal technical and organizational challenges for manufacturers and to discuss the lessons learned, common pitfalls, and improvement pathways for organizations seeking readiness ahead of 2027 while outlining areas where further standardization and research are needed.

The article is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the European regulatory framework.

Section 3 surveys the literature and industrial practice.

Section 4 presents the two-phase methodology for operationalizing the CRA.

Section 5 sets out the practical implications and best practices.

Section 6 reports the TRUEDATA case study and project-wide scoring.

Section 7 discusses the open challenges and lessons learned.

Section 8 concludes with recommendations.

3. Related Work

The evolution of the IoT has generated a growing volume of heterogeneous devices operating under power, capacity, and connectivity constraints, which poses new cybersecurity challenges that the regulatory framework—and the CRA specifically—must address. The existing literature reveals a multi-faceted approach, spanning from deep technical analyses of firmware and software components to regulatory mappings, socio-technical studies, and initial industry experiences. This section synthesizes these diverse contributions to build a comprehensive picture of the current landscape, critically analyses the most relevant technical standards and methodologies (ETSI EN 303 645 [

21], IEC 62443 [

22], NIST IR 8259 [

23], Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF), and OWASP Software Assurance Maturity Model (SAMM)/Building Security In Maturity Model (BSIMM)), and contrasts them with the existing literature to identify the gap this paper aims to fill.

From a technical standpoint, a significant body of research has focused on the foundational challenges of firmware security, which is central to the CRA’s objectives. The work of Butun et al. [

24] provides a comprehensive catalogue of over one hundred attacks, highlighting the breadth of the threat landscape. This is complemented by extensive surveys from Bakhshi et al. [

25] and Haq et al. [

26], which offer a holistic view of the firmware environment, covering architecture, extraction techniques, and vulnerability analysis frameworks. A key takeaway from these studies is the complexity manufacturers face in securing the core of their products. Delving deeper, Feng et al. [

27] describe specific analysis methods like emulation, static analysis, and fuzzing, concluding that hybrid solutions are necessary to handle the diverse architectures of IoT devices—a conclusion that directly informs the technical feasibility of complying with the CRA’s mandate to ship products free of known exploitable vulnerabilities.

A second critical technical area is ensuring the integrity and transparency of software components, a cornerstone of the CRA through its mandate for a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM). The importance of an SBOM is explored from a business perspective by Kloeg et al. [

28], who identify the stakeholder-specific risks and benefits that drive or inhibit adoption. Their finding that System Integrators and Software Vendors are the most likely drivers highlights the complex ecosystem dynamics that will shape CRA compliance. Nocera et al. [

29] provide empirical evidence of this slow adoption, showing that many SBOMs in open-source projects are incomplete or non-compliant. This research grounds the CRA’s SBOM requirement in reality, showing that, while the mandate is clear, its practical and effective implementation remains a significant challenge.

Beyond the device itself, ensuring its integrity in a networked environment is crucial. The work by Ankergård et al. [

30] and the comprehensive survey by Ambrosin et al. [

31] are highly relevant. These studies review protocols designed to remotely verify the software integrity of single or entire networks of devices, offering potential technical solutions for manufacturers to meet the CRA’s implicit requirement for post-market monitoring and to ensure that devices remain secure throughout their lifecycle.

On the regulatory and socio-technical front, several studies have analyzed the CRA’s place within the existing legal framework. Ruohonen et al. [

32] conduct a systematic cross-analysis, confirming the CRA’s role in filling specific gaps left by previous legislation. Shaffique [

33] takes a more critical stance, underscoring the ambiguity of key regulatory terms like “limited attack surface.” He argues that, without harmonized technical specifications from the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), often based on standards such as ETSI EN 303 645 or IEC 62443, these concepts lack the necessary concreteness for effective implementation. This critique is echoed by Vescovi [

34], who argues that regulatory effectiveness depends on creating bidirectional channels of trust with consumers, suggesting that mere compliance is insufficient without a focus on user experience. A critical and often overlooked issue is addressed by van ’t Schip [

35], who investigates the problem of “orphan devices” when a manufacturer ceases operations. This work highlights a significant gap in the current legislation, including the CRA, which assumes manufacturer longevity for providing security updates, pointing to the need for solutions like interoperability and open-source software to ensure long-term device resilience.

Finally, a few studies provide insights from early industrial experiences. The work of Jara et al. [

36] describes the TRUEDATA project, demonstrating the technical feasibility of meeting CRA-like requirements in industrial settings. In contrast, the survey by Risto et al. [

37] reveals significant organizational challenges faced by heavy machinery manufacturers, including immature secure development processes and difficulties in producing SBOMs. This contrast illustrates the critical gap between what is technically possible and what is organizationally practical for many companies.

While the existing literature provides a solid foundation by exploring technical solutions, analyzing regulatory overlaps, and highlighting industrial challenges, a significant gap remains. The existing landscape of security standards and models, while comprehensive, is often fragmented by scope and focus. As summarized in

Table 2, these standards provide vital distinct pieces of the compliance puzzle.

At the organizational level, ISO/IEC 27001:2022 is the pre-eminent standard for an Information Security Management System (ISMS). Its focus is holistic and process-driven, auditing the organization’s capacity to manage information security. However, its scope is a key limitation for the CRA: ISO 27001 is a high-level voluntary management standard, not a product-level engineering guide. It does not, by itself, provide a direct translation of the CRA’s specific legal articles (e.g., on SBOMs or vulnerability timelines) into verifiable technical requirements for a given product with digital elements (PDE).

At the product level, ETSI EN 303 645 has become a key baseline for consumer IoT security, defining what constitutes a secure product by specifying core provisions, such as the prohibition of universal default passwords and the need for a vulnerability disclosure policy [

21]. While its principles are foundational, it remains a high-level list of goals, not a methodology for auditable integration throughout the DevSecOps lifecycle.

Other frameworks complement these: rigorous secure development lifecycle (SDL) frameworks, such as IEC 62443 and the NIST SSDF, provide the process for implementation, while organizational maturity models like OWASP SAMM and BSIMM offer the means to measure corporate capability. However, none of these, in isolation, offers a complete legally traceable methodology for operationalizing and quantifying compliance with the CRA’s specific binding obligations.

However, most studies focus on either a deep technical problem (like remote attestation or SBOM generation) or a high-level legal or industrial analysis. Few, if any, bridge this gap by formalizing a methodology for translating the CRA’s high-level legal obligations into a comprehensive, actionable, and lifecycle-based compliance model. This requires engaging with two specific academic domains: requirement engineering from legal texts and quantitative cybersecurity assessment.

5. Practical Implications of the CRA in the IoT

The entry into force of the CRA not only demands compliance with new requirements but also drives a comprehensive transformation that spans product engineering, internal governance, and auditing. The main technical and organizational implications are outlined below, indicating how to close regulatory gaps and illustrating challenges and solutions through real-world experiences. A concise summary of recommended practices is provided in

Table 4.

To translate the principle of security by design into concrete actions, threat-modeling activities should be embedded from the outset to map critical assets, attack vectors, and realistic exploitation scenarios. These outputs must become visible design requirements in the development backlog and feed automated tests in an expanded Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) pipeline—combining static code analysis, symbolic fuzzing, and dynamic firmware testing in emulation environments (Narrowband Internet of Things (NB-IoT); 4G, Long Range (LoRa))—as captured in

Table 4 (secure design; automated testing).

In parallel, the CRA mandates machine-readable SBOMs and secure automatic over-the-air (OTA) update mechanisms. Every dependency change should trigger SBOM generation (CycloneDX or SPDX), license validation, and Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) queries to spot known vulnerabilities. The OTA channel must use encrypted and digitally signed protocols, include a clear user opt-out, and be complemented by collective remote attestation (e.g., Scanning, Analysis, Response and Assessment (SARA)) to verify the integrity of devices in production (see

Table 4, SBOM and traceability; patch delivery).

At the organizational level, the CRA expects a Cybersecurity Management System (CSMS) that defines roles, responsibilities, and workflows. Under a Development, Security, and Operations (DevSecOps) operating model, Development, Quality Assurance (QA), Operations, and Compliance should review Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) regularly (e.g., vulnerability counts, mean time to remediation, SBOM coverage, and attestation results). A coordinated vulnerability disclosure (CVD) policy is essential. This policy must define the public-facing process for security researchers to report issues and the internal workflows for meeting the CRA’s strict 24 h alert and 72 h initial reporting deadlines. Using standardized formats, such as Structured Threat Information eXpression (STIX) or Common Vulnerability Reporting Framework (CVRF), is recommended to ensure interoperability (

Table 4, coordinated vulnerability disclosure (CVD); DevSecOps Governance).

Document analysis reveals gaps in the precision of essential concepts: terms such as “without exploitable vulnerabilities” or “limited attack surface” lack detailed technical specifications. To bridge these gaps, manufacturers should maintain internal audit guides—grounded in standards like IEC 62443 or ETSI EN 303 645—that specify which fuzzing techniques apply to each device category, how to measure surface reduction on interfaces, and what criteria validate an SBOM.

Real-world experiences echo these points. In Libelium’s TRUEDATA project, integrating Open Mobile Alliance Lightweight Machine-to-Machine (OMA LwM2M) probes with a Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) system (Elasticsearch/Logstash/Grafana) enabled monitoring of tens of thousands of devices, event correlation, and automated responses, albeit with ingestion bottlenecks that required pipeline and parser optimization. Likewise, industrial equipment manufacturers acknowledge that, without up-to-date SBOMs and agile notification processes, regulatory timelines may be missed, increasing operational and reputational risk.

To synthesize these practices into a coherent operational model,

Figure 3 presents a visual map of the DevSecOps lifecycle tailored to CRA compliance. This workflow illustrates how the lifecycle phases and their corresponding actions—detailed further in

Appendix A—integrate into a continuous cycle of development, security, and operations.

To maintain the narrative flow of the analysis whilst still providing a detailed actionable tool for manufacturers, the complete breakdown of this checklist is presented in

Appendix A. This appendix details the specific actions, expected evidence, frequency, and direct references to the CRA articles, serving as a granular implementation guide.

As detailed in

Appendix A, the lifecycle framework is broken down into several key phases, each with specific obligations. The governance and scope phase is foundational (see

Table A1): it begins with a formal PDE classification that determines the conformity-assessment route, the establishment of a CSMS (policies, KPIs, and review cadence), the public statement of the security support period, and the publication of a CVD policy with a single point of contact.

The Secure Design and Development phase operationalizes security by design (see

Table A2). Risk is treated as a living artifact, re-evaluated at each milestone. Threat-modeling frameworks such as STRIDE (Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information disclosure, Denial of service, and Elevation of privilege) and LINDDUN (Linkability, Identifiability, Non-repudiation, Detectability, Disclosure of information, Unawareness, and Non-compliance) translate risks into actionable user stories and acceptance criteria. Technical priorities include hardening interfaces to minimize attack surface, enforcing least-privilege defaults, protecting integrity (secure boot, signing, and anti-rollback), and applying data minimization and CIA (Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability) controls—alongside due diligence on third-party and open-source software.

Vulnerability Management and Support sustain resilience over time (see

Table A3). A formal Product Security Incident Response Team (PSIRT) process handles reports under defined SLAs; proactive monitoring of National Vulnerability Database (NVD)/GitHub Security Advisories (GHSAs) feeds triage and patching; CI/CD gates block releases with known exploitable vulnerabilities; OTA updates are automatic by default, securely delivered, and supported for the declared period; every build ships with a machine-readable SBOM (and, where relevant, VEX) and clear user communications.

The CRA also imposes strict timelines for the Notification of Exploited Vulnerabilities and Incidents (see

Table A4), including a 24 h early warning to CSIRTs/ENISA, a 72 h initial notification, and a final report after remediation—together with timely information for affected users.

Post-market obligations ensure continuity of compliance (see

Table A5): manufacturers must uphold the support period, retain technical documentation (including the EU Declaration of Conformity (DoC)), ensure series-production conformity, cooperate with Market Surveillance Authorities, and plan End-of-Life/End-of-Support with appropriate user guidance.

Finally, conformity assessment and CE marking are the gateway to the market (see

Table A6), culminating in the EU Declaration of Conformity and CE marking. Clear and accessible user information (see

Table A7)—from secure installation and updating instructions to contact points and SBOM/VEX access—completes the lifecycle.

By following this structured approach, the CRA’s practical implications become a manageable roadmap that supports both regulatory compliance and genuine cyber resilience across the IoT ecosystem.

6. TRUEDATA Real Experience: CRA in Practice

This section demonstrates the practical application and validates the feasibility of the proposed two-phase compliance framework. The framework is applied to the TRUEDATA project to produce a single project-wide (site-agnostic) score and readiness profile.

The TRUEDATA project was specifically selected for this validation exercise precisely because it represents a high-stakes complex industrial (OT) environment rather than a simpler consumer IoT product. It is a cybersecurity initiative, funded by INCIBE (Instituto Nacional de Ciberseguridad (Spain)) within the European Union recovery and resilience framework, aimed at strengthening the resilience of critical water infrastructures (drinking-water treatment plants, wastewater facilities, desalination plants, pumping stations, and dams). Its scope—protecting essential assets against threats targeting SCADA (Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition) systems, Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs), and Operational Technology (OT)/Information Technology (IT) networks—provides a rigorous test case. The rationale is that a framework proven sufficient for this demanding critical-infrastructure context should be highly adaptable to other IoT domains. As an applied R&D project, its stated goal is to advance a solution from Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 4 to TRL 9, focusing on integrating IoT, AI, and blockchain technologies for active protection and operational resilience. The analysis applies the full framework detailed in

Section 4. First, the checklist derived from Phase 1 (see

Appendix A) was used to assess the project’s current state. Second, the quantitative model from Phase 2 was used to calculate a weighted compliance score.

Following the methodology in

Section 4.2, an AHP analysis was conducted to derive the weights for the eight primary compliance domains used in the assessment. The pairwise comparison matrix, based on the expert judgment of the authors, is presented in

Table 5.

Furthermore, to validate the stability of these priorities beyond the consistency check (CR = 0.014), a sensitivity analysis was performed [

51]. This involved simulating ‘what-if’ scenarios by altering the judgments of the highest-weighted criterion (‘secure by design’) [

52]. Even with a 20% variation in its principal judgments, the criterion remained the top-ranked domain. When propagated to the final assessment, this variation altered the aggregated score (detailed later in this section) by less than ±4%, demonstrating that the model’s overall assessment is robust and not unduly sensitive to minor variations in expert judgment.

The resulting weights clearly prioritize ‘secure by design’ (32.2%) and ‘vulnerability management’ (21.9%) as the most critical domains for overall compliance, reflecting their central role in the CRA’s lifecycle security philosophy.

Figure 4 visualizes the resulting readiness profile against a pilot-ready target.

To provide context for this analysis, the system’s high-level technical architecture is depicted in

Figure 5. This diagram illustrates the flow of data from ingestion at the operational level through the processing and detection components.

TRUEDATA performs strongly in technical execution because its end-to-end data path is explicit, instrumented, and secure by design. The architecture is built on a foundation of robust technologies, including a sophisticated Extract--Transform--Load (ETL) pipeline orchestrated in Node-RED for data validation, AI models such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for OT anomaly detection, and a Snort-based industrial Intrusion Detection System (IDS) for network monitoring. This technical maturity justifies high marks in categories related to monitoring, data integrity, and secure design principles.

Conversely, several scores remain in the medium- or high-risk band, primarily due to deliberate gaps in governance and lifecycle management. These areas, including formalized logging, incident response, vulnerability management, and especially SBOM generation and coordinated vulnerability disclosure, were not prioritized in the initial R&D phase. This reflects a strategic trade-off, common in technology-driven projects, where demonstrating the feasibility of the core AI engine and advancing its TRL took precedence over establishing mature operational and compliance scaffolding.

Applying the aggregation formula from

Section 4.2, the weighted domain scores yield a project-wide score of ≈6.70/10, characterized as partially compliant with medium residual risk. The calculation is performed by multiplying the AHP-derived weight of each domain by its assessed score (derived from the evidence in

Table 6) and summing the results:

This aggregated score of ≈6.70 is the direct result of applying the AHP-derived weights (

Table 5) to the domain-specific scores justified in the subsequent

Table 6. The rationale for this ‘medium-risk’ score becomes clear upon analysis: whilst the project scored highly in technically mature domains (e.g., 9.2/10 for ‘monitoring’ and 8.0/10 for ‘design’), the overall score is quantitatively impacted by significant high-risk gaps in key governance areas. Specifically, the low scores for ‘SBOM and supply chain’ (3.5/10) and ‘coordinated vulnerability disclosure’ (3.0/10)—both fundamental CRA requirements—demonstrate how procedural and documentary gaps directly reduce the measured readiness despite the system’s technical robustness. The gap to the pilot-ready target, which requires closing these specific gaps, is illustrated in

Figure 4.

To provide a granular justification for the assigned scores,

Table 6 maps specific project evidence and quantitative performance metrics to each category of the checklist.

To close these identified gaps and move from partial compliance to a pilot-ready state, the following measurable improvements are proposed. These actions demonstrate the framework’s utility as a decision-support tool, enabling the prioritization of remediation efforts based on the domains with the highest weights and lowest scores.

- (a)

SBOM/VEX in CI/CD. Integrate automated SBOM generation in SPDX or CycloneDX format and vulnerability scanning into the CI/CD pipeline. The primary KPI will be SBOM Component Coverage, with a target of achieving >95% coverage.

- (b)

CVD program. Establish and publish a formal CVD policy compliant with standards such as RFC 2350 and security.txt. The key performance metric will be Mean Time to Acknowledge (MTTA), with a target of <48 h.

- (c)

Centralized logging and alerting. Complete the integration of a centralized logging solution with a defined data retention policy (minimum 12 months) to support forensic analysis.

- (d)

Vulnerability management at scale. Implement periodic automated container image and OS scanning within the CI/CD pipeline, with a target of deploying patches for critical vulnerabilities (Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) > 9.0) within 14 days.

- (e)

Lifecycle and conformity pack. Codify the product support period and create a reproducible conformity dossier containing all evidence required by Annex VII of the CRA.

These actions are consistent with the CRA lifecycle checklist and materially raise the weakest categories, lifting the weighted score into the ∼7.7–7.9 range and nudging residual risk towards medium–low (cf.

Figure 4).

7. Open Challenges and Lessons Learned

The practical application of the CRA across a vast and varied IoT ecosystem reveals several open challenges. While the regulation sets a necessary horizontal baseline, real success depends on tackling technical complexity, organizational inertia, and market pressures. A first challenge is the meaning of key terms. Phrases such as “appropriate level of cybersecurity”, “limited attack surface”, and “without known exploitable vulnerabilities” are central to the CRA, yet they lack precise harmonized technical definitions. Without clear guidance from the ENISA or standardization bodies, manufacturers must interpret these requirements on their own. This can lead to uneven security across the market and uncertainty during conformity assessment.

Supply chain complexity is another major hurdle. The duty to produce a comprehensive machine-readable Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) is a strong step towards transparency, but its value depends on accurate and complete inputs from upstream suppliers, especially for open-source software. Creating and maintaining high-quality SBOMs for deep dependency trees is still a difficult engineering and operational task.

Long-term support and vulnerability management also carry significant costs, particularly for SMEs. Committing to a support period of at least five years, with timely security updates, requires investment in people, processes, and infrastructure. For low-cost, high-volume devices, this model may be hard to sustain, risking the appearance of orphan devices if a manufacturer leaves the market or ends a product line. This exposes a legislative gap as the CRA’s effectiveness assumes manufacturer continuity. Finally, moving towards DevSecOps may be the most demanding organizational shift. Embedding security into every phase of development means breaking down silos between development, operations, and security. This is not only about tools; it also requires leadership, continuous training, and clear governance.

Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge the methodological limitations inherent in the AHP-based weighting process itself [

53]. While the AHP provides a structured and mathematically consistent framework, its outputs are fundamentally reliant on the subjective judgments of the expert panel [

50]. In this study, the panel was composed of the authors; whilst possessing domain expertise, this introduces a potential source of implicit bias. A larger, more diverse panel of external industry and regulatory experts could certainly yield different domain weights. Moreover, the AHP methodology is subject to well-documented academic critiques, such as the potential for ‘rank reversal’, where the introduction or deletion of a criterion can alter the priority of existing ones [

54], and the artificial constraint of the 1–9 Saaty scale, which can make it difficult to represent exceptionally large differences in importance [

55]. Although our consistency check (CR < 0.10) provided assurance against contradictory judgments, these inherent limitations underscore that the resulting weights should be viewed as a validated starting point for risk prioritization, not as an immutable ground truth.

Experience from the TRUEDATA project suggests a practical approach: treat the CRA not as a checklist but as the governance layer for Zero-Trust engineering in both OT and the IoT. This mindset turns regulatory requirements into a driver for sound security architecture. In practice, it is advisable to start small and improve step by step, focusing first on one high-impact phase rather than attempting a full overhaul. Mirroring OT traffic early provides ground-truth data to train anomaly-detection models and to define a baseline of normal behavior. For operational resilience, keep key inference at the edge so that monitoring and alerts continue even if cloud links fail. Lastly, formalize what matters: publish a public coordinated vulnerability disclosure (CVD) policy (e.g., aligned with RFC 2350), generate complete SBOMs to ensure supply-chain transparency, and run a structured vulnerability-management process. This is “Next-Gen Zero Trust” in practice: explicit continuous verification of device behavior, least-privilege access enforced by policy, and cryptographic integrity for the data that runs the operation.

Looking beyond these immediate lessons, the identified challenges of complexity and continuous oversight point toward a future of automated compliance. The difficulty in managing complex dynamic supply chains, for instance, may be mitigated by future AI-driven compliance systems. Such platforms could utilize advanced graph-based models, like hypergraph neural networks, to map high-order dependencies in a product’s SBOM and model dynamic risk propagation [

47]. In parallel, semantic reasoning engines, drawing on research into semantic-level security, could enable monitoring that ensures the meaning and integrity of data transmissions are protected, fulfilling CRA mandates in a way that simple encryption cannot [

48]. Moreover, the challenge of continuous post-market evaluation could be met by self-adaptive digital twins. This would allow manufacturers to evolve from static point-in-time assessments to a continuous evidenced-based evaluation of CRA readiness, providing a quantifiable and testable metric for requirements such as ‘limited attack surface’.

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

This paper has addressed the critical gap between the Cyber Resilience Act’s legal mandates and auditable engineering practice. We introduced and validated a formal two-phase framework that operationalizes the act, providing a transparent methodology for systematic requirement distillation and a quantitative AHP-based model for assessing compliance readiness. This contribution provides a tangible lifecycle-based model that shifts the paradigm from general guidance to binding actionable compliance.

First, the systematic requirement distillation process provides a clear and traceable path from the legal articles of the CRA to concrete lifecycle-mapped engineering and governance tasks. This transforms abstract legal mandates into an actionable compliance blueprint. Second, the AHP-based quantitative assessment model offers a rigorous and consistent method for evaluating compliance readiness. By deriving risk-informed weights for key compliance domains, it moves beyond subjective qualitative assessments and provides a defensible basis for prioritizing investments and tracking progress over time. The value of this framework lies not only in the specific CRA checklist produced but in the adaptable methodology that can be applied to other current and future cybersecurity regulations.

To respond effectively, manufacturers should begin with a rigorous internal maturity assessment against the regulation’s requirements, identifying gaps from threat modeling through the automated generation of machine-readable SBOMs. On the basis of this diagnosis, an actionable roadmap should follow. This plan ought to cover the product backlog—adding security-focused user stories—and extend the CI/CD pipeline to include static analysis, symbolic fuzzing, and dynamic testing in emulated environments. It should also automate SBOM creation and deliver a digitally signed and encrypted OTA channel, ideally complemented by collective remote attestation to verify device integrity in the field at regular intervals.

Compliance, however, goes beyond technology: it requires a clear cultural and organizational shift. A Cybersecurity Management System (CSMS) aligned with a DevSecOps model is key to fostering collaboration among Development, QA, Operations, and Compliance. Teams should share and act on common metrics—such as mean time to remediation, SBOM coverage, and attestation success rates—and refine their approach continuously. Formalizing a coordinated vulnerability disclosure policy, using STIX/CVRF formats and meeting the CRA’s 24 h early-warning and 72 h initial-report deadlines, is essential for both regulatory adherence and building trust. In parallel, internal guidelines based on international standards (e.g., IEC 62443 and ETSI EN 303 645) should translate ambiguous terms like “limited attack surface” into clear audit criteria, making self-assessment and voluntary certification (EUCC) more practical and reliable.

Looking ahead, further research should build upon the methodology presented here. Important technical challenges remain, including more lightweight cybersecurity tools for low-power devices and interoperability models for SBOMs and patches to support the resilience of “orphan devices” if a manufacturer ceases operations. Future work should also focus on refining the framework, for instance by expanding the AHP model with more granular criteria or exploring NLP-based automation for the requirement extraction phase [

56].

Moreover, the framework’s adaptability to other domains is a key area for development. For industrial control (OT) environments, the methodology is directly applicable; the TRUEDATA case study, with its focus on SCADA and PLCs, already validates this. Future work in this area could focus on creating harmonized models that map CRA obligations against established standards, such as IEC 62443-4-1 [

22]. The application to artificial intelligence (AI) systems, which also fall under the CRA’s scope [

1,

14], presents a more complex but equally viable adaptation. The two-phase methodology remains valid, but the content of the ‘secure-by-design’ domain would need to be expanded. This would involve addressing AI-specific vulnerabilities (e.g., data poisoning and adversarial attacks) and adapting the concept of an SBOM to include AI artifacts, such as training data and model parameters, in line with emerging ‘Artificial Intelligence Bill of Materials (AI-BOM)’ concepts [

57].

Furthermore, to broaden the empirical grounding of this work, a follow-on study would be beneficial, applying the framework to a more diverse portfolio of common IoT products (e.g., consumer smart devices) to validate its generalizability beyond the high-complexity industrial domain.

Additional work on dynamic attack surfaces in edge and multi-hub networks—together with the use of artificial intelligence for advanced event correlation and automated response orchestration—will help to anticipate and mitigate emerging threats.

Ultimately, close collaboration with the ENISA and standardization bodies will be vital to pilot, validate, and refine the technical standards that clarify the CRA’s more ambiguous mandates, enabling European industry to build a truly resilient and trustworthy Internet of Things.