From E-Democracy to C-Democracy: Analyzing Transnational Political Discourse During South Korea’s 2024 Presidential Impeachment on Polymarket

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Traditional and Digital Democracy

2.2. Affective and Playful Publics in the Digital Age

2.3. From Affective to Financialized Publics

2.4. Web3, Blockchain Governance, and the Rise of C-Democracy

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Analytical Procedure

3.3. Replicability Statement

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

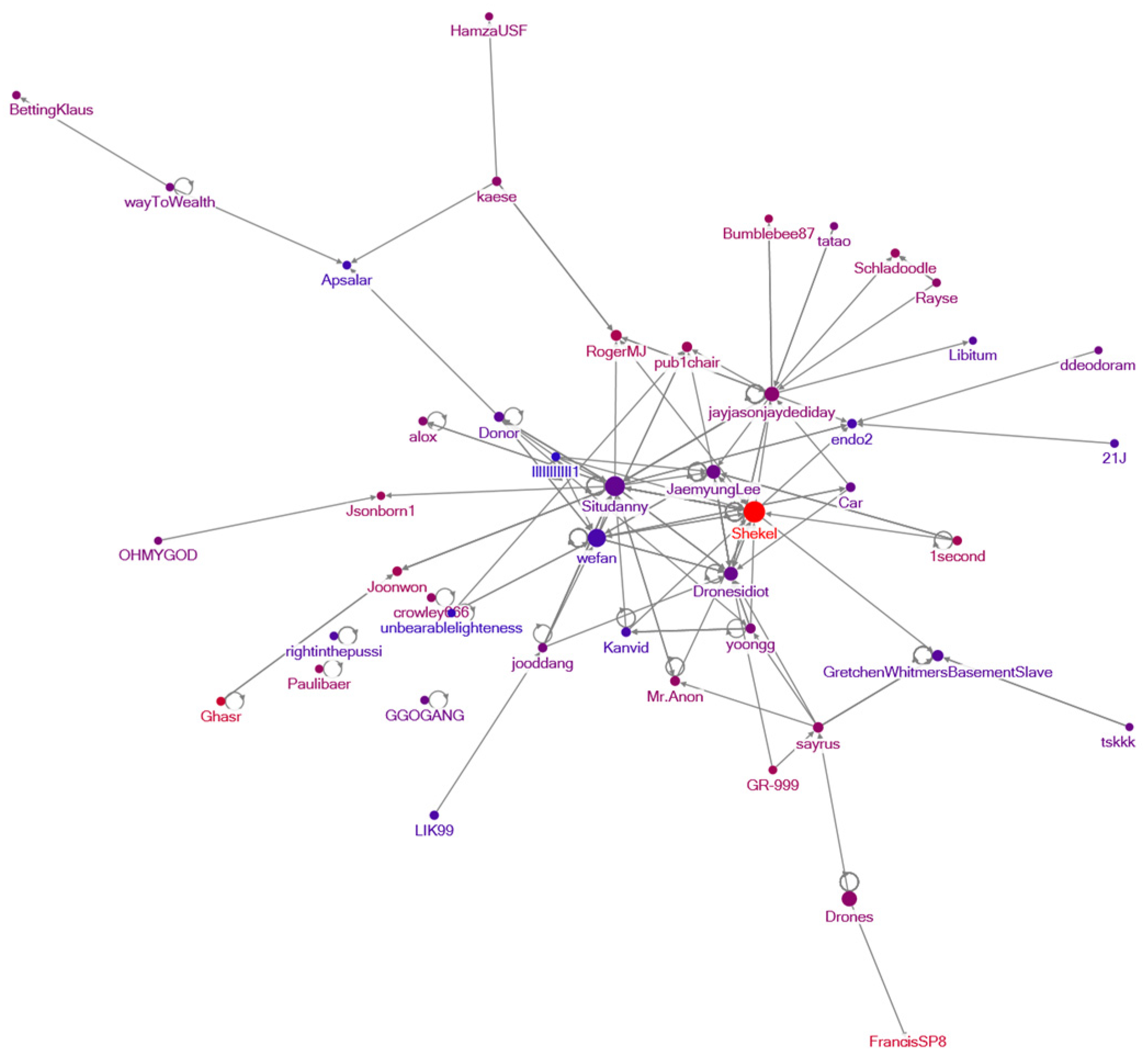

4.2. Network Structure and User Behavior Analysis

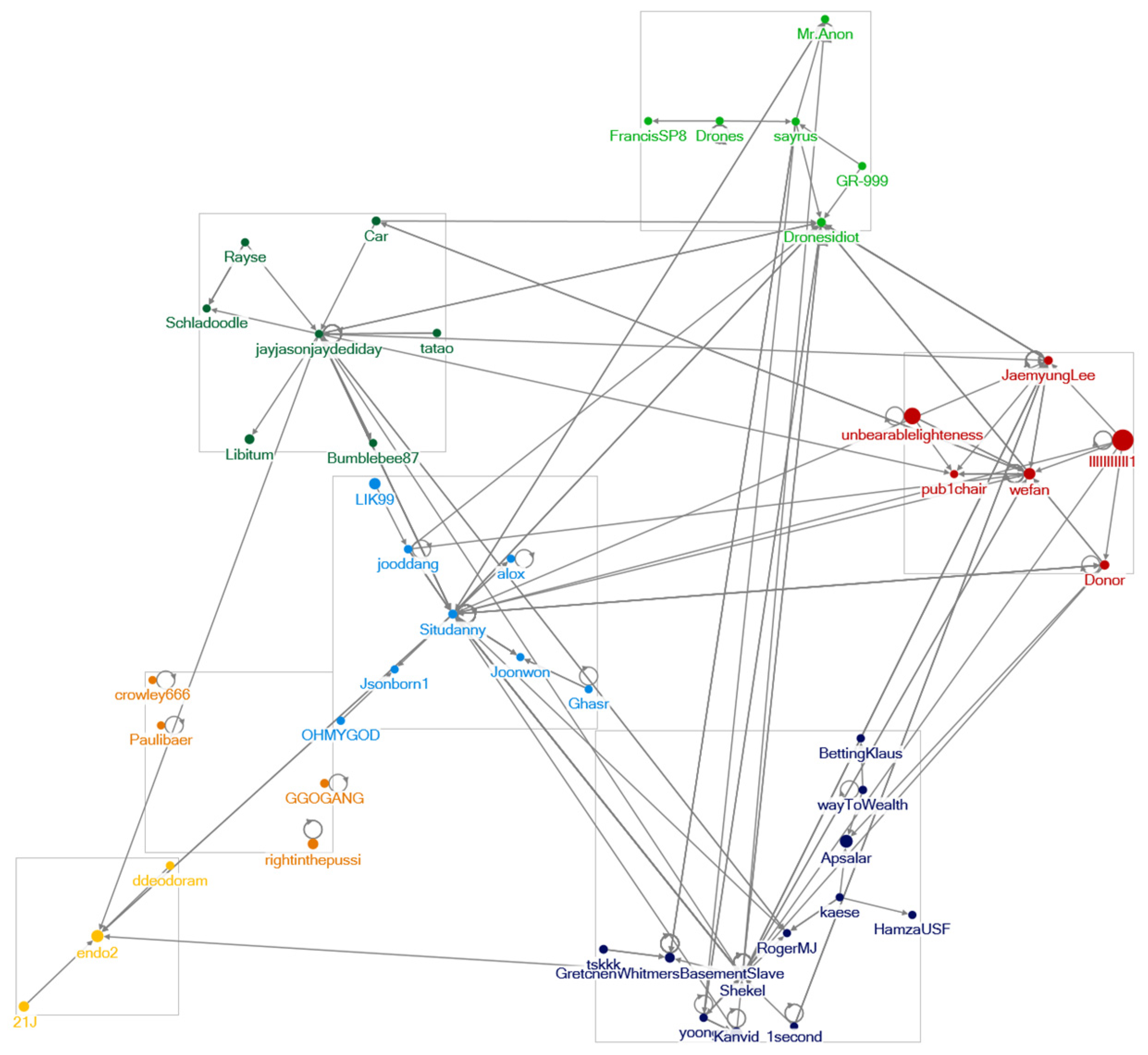

4.3. Discourse Community Analysis

4.4. Quantitative Validation

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindner, R.; Aichholzer, G. E-Democracy: Conceptual Foundations and Recent Trends. Eur. E-Democr. Pract. 2019, 11–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, M. From computational social choice to digital democracy. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Montreal, QC, Canada, 19–27 August 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsangiacomo, C. Clarifying and Defining the Concept of Liquid Democracy. Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 2021, 28, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Papacharissi, Z. The virtual sphere: The Internet as a public sphere. New Media Soc. 2002, 4, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, L.; Divon, T. Playful Activism: Memetic Performances of Palestinian Resistance in TikTok #Challenges. Soc. Media + Soc. 2023, 9, 20563051231157607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divon, T. Playful publics on TikTok: The memetic is political. Soc. Media + Soc. 2023, 9, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kapp-Schwoerer, L. Improved Liquidity for Prediction Markets; ETH Zürich Distributed Computing Group: Zurich, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Papacharissi, Z. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Park, H.W. An exploratory approach to a Twitter-based community centered on a political goal in South Korea: Who organized it, what they shared, and how they acted. New Media Soc. 2013, 16, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highfield, T.; Leaver, T. Instagrammatics and digital methods: Studying visual social media, from selfies and GIFs to memes and emoji. Commun. Res. Pract. 2016, 2, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M.J. Humour in Political Activism; Palgrave Macmillan UK eBooks: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, N.S.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Park, H.W. Identifying the Impacts of Social Movement Mobilization on YouTube: Social Network Analysis. Information 2025, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, J. ‘It’s So Hard Not to be Funny in This Situation’: Memes and Humor in U.S. Youth Online Political Expression. Telev. New Media 2019, 21, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drina, I.; Qasim, M.; Anter, V.; Kusumajanti; Windhi, T.S. Media Use and Online Political Participation: The Mediating Roles of Media Credibility and Political Trust in Jakarta and Islamabad. J. Contemp. East. Asia 2025, 24, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, M. The maturing concept of E-Democracy: From E-Voting and online consultations to democratic value out of jumbled online chatter. J. Inf. Technol. Politics 2009, 6, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Park, H.W. Comparing news and non-news sites in Web3 domain. ROSA J. 2024, 1, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.C.; Lee, J.; Yoon, H.Y. Harnessing Earned Media: A Comparative Analysis of Landmark Digital Signage Impact on Social Media. J. Contemp. East. Asia 2025, 24, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Kamath, S.; Ramani, S.; Sonawane, P. BetNation—A Decentralized Bookmaking Platform. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on IoT and Blockchain Technology (ICIBT), Ranchi, India, 6–8 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatarneh, A. Blockchain technology and corporate governance: The issue of smart contracts–current perspectives and evolving concerns. ética Econ. Bien Común 2024, 17, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A.B.; Miyazaki, S. What Happens When Anyone Can Be Your Representative? Studying the Use of Liquid Democracy for High-Stakes Decisions in Online Platforms; Stanford University Graduate School of Business: Stanford, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.S.; Park, H.W. The structural relationship between politicians’ web visibility and political finance networks: A case study of South Korea’s National Assembly members. New Media Soc. 2012, 15, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Park, H.W. Four. Digital Media and the Transformation of Politics in Korea; Stanford University Press eBooks: Redwood, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.W.; Jankowski, N.W. A hyperlink network analysis of citizen blogs in South Korean politics. Javn.-Public 2008, 15, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palak, R.; Nguyen, N.T. Prediction markets as a vital part of collective intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Innovations in Intelligent Systems and Applications (INISTA), Gdynia, Poland, 3–5 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernov, M.; Vadim, E.; Song, D. The Comovement of Voter Preferences: Insights from U.S. Presidential Election Prediction Markets Beyond Polls; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Leighley, J.E. Attitudes, Opportunities and Incentives: A Field Essay on Political Participation. Political Res. Q. 1995, 48, 181–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, W.D. The Political Economy of Collective Action, Inequality, and Development; Stanford University Press: Redwood, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Winecoff, A.A.; Lenhard, J. Techno-Utopians, Scammers, and Bullshitters: The Promise and Peril of Web3 and Blockchain Technologies According to Operators and Venture Capital Investors; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, L.; Eich, S. Crypto-politics and counterfeit democracy. Financ. Soc. 2023, 9, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.W. Web3 Technology and Democracy; Yeungnam University Press: Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Barbereau, T.; Smethurst, R.; Papageorgiou, O.; Sedlmeir, J.; Fridgen, G. Decentralised Finance’s timocratic governance: The distribution and exercise of tokenised voting rights. Technol. Soc. 2023, 73, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Gupta, D. Appropriate tokenomics: Ensuring equitable incentives in decentralized ecosystems. Sci. J. Metaverse Blockchain Technol. 2025, 3, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Duan, X.; El Saddik, A.; Cai, W. Political leanings in Web3 betting: Decoding the interplay of political and profitable motives. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.14844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroll, L. The Principles of Parliamentary Representation; Harrison and Sons: High Wycombe, UK, 1884. [Google Scholar]

- Sorce, G.; Dumitrica, D. Transnational dimensions in digital activism and protest. Rev. Commun. 2022, 22, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, D. Cosmopolitan Democracy and the Global Order: Reflections on the 200th Anniversary of Kant’s “Perpetual Peace”. Altern. Glob. Local Political 1995, 20, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D. Social Network Sites as Networked Publics: Affordances, Dynamics and Implications; Papacharissi, Z., Ed.; A Networked Self, Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W.L.; Segerberg, A. THE LOGIC OF CONNECTIVE ACTION: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2012, 15, 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, J.; Maher, T.V.; Pan, J. The digital repression of social movements, protest, and activism: A synthetic review. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl8198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paoli, S. Performing an inductive thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews with a large language model: An exploration and provocation on the limits of the approach. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2023, 42, 997–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Shneiderman, B.; Milic-Frayling, N.; Rodrigues, E.M.; Barash, V.; Dunne, C.; Capone, T.; Perer, A.; Gleave, E. Analyzing (social media) networks with NodeXL. C&T ’09. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Communities and Technologies, University Park, PA, USA, 25–27 June 2009; pp. 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J. Modularity and community structure in networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8577–8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Echeverria, V.; Fernandez-Nieto, G.M.; Jin, Y.; Swiecki, Z.; Zhao, L.; Gašević, D.; Martinez-Maldonado, R. Human-AI Collaboration in Thematic Analysis using ChatGPT: A User Study and Design Recommendations. In Proceedings of the CHI: Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paoli, S.; Mathis, W.S. Reflections on inductive thematic saturation as a potential metric for measuring the validity of an inductive thematic analysis with LLMs. Qual. Quant. 2024, 59, 683–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumler, J.G.; Coleman, S. Realising Democracy Online: A Civic Commons in Cyberspace; Citizens Online: Providence, RI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, C.R. Republic.com; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, A. Internet Politics: States, Citizens, and New Communication Technologies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.C. A program for direct and proxy voting in the legislative process. Public Choice 1969, 7, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P. Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| User | Comments | Bet Amount | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shekel | 86 | 1.007 | Yes |

| Situdanny | 73 | 4807.875 | Yes |

| wefan | 59 | 20,648.850 | Yes |

| Drones | 38 | 592.429 | Yes |

| jayjasonjaydediday | 34 | 807.513 | Yes |

| Group | Size | Avg Comments | Avg Reactions | Avg Betting | Main Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 12 | 12.750 | 9.083 | 3662.810 | Analytical: Links, data, neutral tone |

| G2 | 8 | 12.750 | 9.125 | 3556.999 | Critical: Political evaluation, definitive |

| G3 | 7 | 7.571 | 10.714 | 2266.483 | Informational: Verification, concise |

| G4 | 3 | 15.333 | 9.000 | 894.628 | Emotional: Strong reactions, metaphors |

| G5 | 6 | 19.167 | 14.333 | 34,579.609 | Reactive: Quick exchanges, yes/no |

| G6 | 4 | 3.500 | 3.500 | 4645.089 | Casual: Internet slang, brief |

| G7 | 3 | 3.667 | 2.667 | 13,260.944 | Practical: Simple conclusions, links |

| Comments | Replies Sent | Replies Received | Reactions | Betting Amount | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comments | 1.000 | 0.823 | 0.713 | 0.662 | 0.329 |

| Replies Sent | 1.000 | 0.616 | 0.529 | 0.327 | |

| Replies Received | 1.000 | 0.686 | 0.405 | ||

| Reactions | 1.000 | 0.418 | |||

| Betting Amount | 1.000 |

| G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | G6 | G7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 1.000 | 0.789 | 0.755 | 0.746 | 0.602 | 0.534 | 0.433 |

| G2 | 1.000 | 0.861 | 0.811 | 0.782 | 0.479 | 0.414 | |

| G3 | 1.000 | 0.748 | 0.734 | 0.466 | 0.406 | ||

| G4 | 1.000 | 0.782 | 0.483 | 0.424 | |||

| G5 | 1.000 | 0.418 | 0.518 | ||||

| G6 | 1.000 | 0.246 | |||||

| G7 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, H.-W.; Kim, J.-H.; Osman, N.S. From E-Democracy to C-Democracy: Analyzing Transnational Political Discourse During South Korea’s 2024 Presidential Impeachment on Polymarket. Information 2025, 16, 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110980

Park H-W, Kim J-H, Osman NS. From E-Democracy to C-Democracy: Analyzing Transnational Political Discourse During South Korea’s 2024 Presidential Impeachment on Polymarket. Information. 2025; 16(11):980. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110980

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Han-Woo, Jae-Hun Kim, and Norhayatun Syamilah Osman. 2025. "From E-Democracy to C-Democracy: Analyzing Transnational Political Discourse During South Korea’s 2024 Presidential Impeachment on Polymarket" Information 16, no. 11: 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110980

APA StylePark, H.-W., Kim, J.-H., & Osman, N. S. (2025). From E-Democracy to C-Democracy: Analyzing Transnational Political Discourse During South Korea’s 2024 Presidential Impeachment on Polymarket. Information, 16(11), 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110980