5. Experimental Evaluation

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed DAHG framework in long-term precipitation forecasting, we conduct comprehensive experiments on real-world meteorological and remote sensing datasets. This section introduces the datasets, evaluation metrics, baseline methods, and implementation details used in our evaluation.

5.1. Datasets

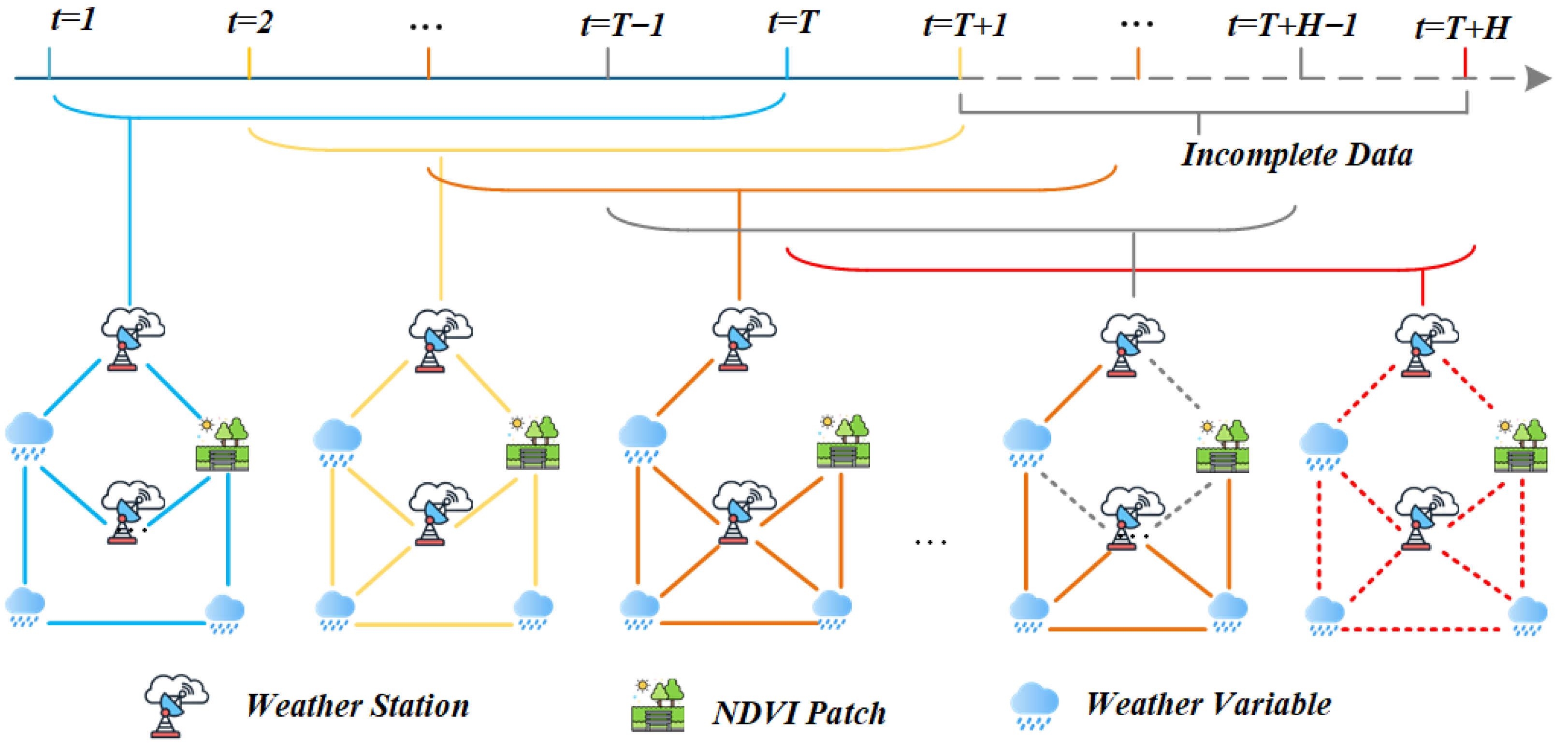

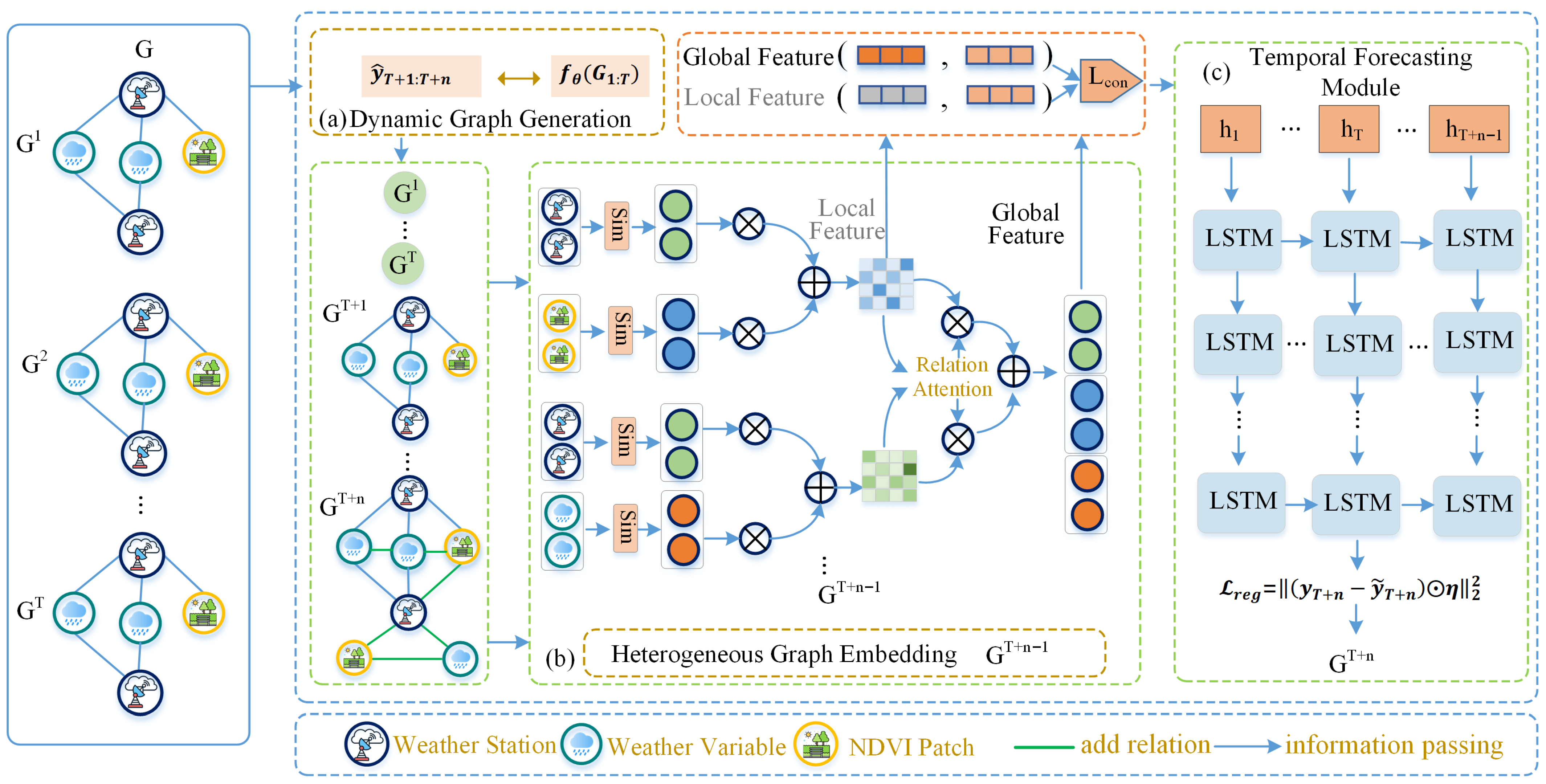

To evaluate the model’s capacity for multi-source fusion, heterogeneous spatial modeling, and temporal forecasting, as detailed in

Table 1, we adopt two representative datasets covering distinct spatial scales and climate regions:

ERA5-Land Reanalysis Data (ECMWF) (

https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-land?tab=overview): This dataset provides hourly meteorological variables including surface precipitation, temperature, humidity, and wind speed, with a spatial resolution of 0.25°. The temporal coverage spans from 2010 to 2020. We focus on the agricultural regions of Eastern China (longitude: 105–125° E; latitude: 25–40° N) as our study area.

MODIS NDVI (MOD13Q1) (

https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/search/order/1/MODIS:Terra:MOD13Q1): This dataset provides a 16-day composite Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) at 250 m resolution, serving as a proxy for vegetation health. NDVI is also relevant for precipitation forecasting as it reflects vegetation–climate feedback (e.g., vegetation influences evapotranspiration and surface energy balance). NDVI time series are aligned with meteorological data using nearest-neighbor interpolation. For MODIS NDVI (MOD13Q1, 16-day temporal resolution), we aligned the values to the hourly ERA5-Land series by nearest-neighbor expansion. This introduces stepwise plateaus, but these are acceptable here since vegetation indices vary slowly compared to hourly meteorological dynamics. Our code is available on the Github repository (

https://github.com/zllovegy/DAHG_Framework) (

Supplementary Materials) to afford the reader validating our results.

The combination of ERA5-Land meteorological variables and MODIS NDVI is motivated by the well-documented interactions between precipitation and vegetation dynamics: Rainfall influences vegetation growth, while vegetation cover, in turn, modulates land–atmosphere exchanges of water and energy [

43]. Incorporating both climate drivers and vegetation indicators thus enables a more holistic representation of the factors shaping regional precipitation variability.

The preprocessing pipeline includes missing value imputation, min–max normalization, spatial regridding, and the construction of dynamic heterogeneous graphs. Each graph frame consists of station nodes, variable nodes, and remote sensing nodes, with edges defined based on spatial proximity and semantic correlation. In total, we construct over 80,000 temporal graph frames, with an hourly sampling rate. All raw ERA5-Land variables are regridded to a uniform resolution using bilinear interpolation, while MODIS NDVI patches are aggregated to match ERA5-Land grid cells. We apply min–max normalization separately for each modality to ensure numerical stability. Quality control procedures include the removal of physically implausible values (e.g., negative precipitation, NDVI outside ) and linear interpolation for short gaps (less than two time steps). Station-level outliers exceeding three standard deviations from the local temporal mean are initially flagged as candidates for correction. To ensure that genuine extreme rainfall events are not inadvertently removed, we apply a multi-criteria validation before any smoothing: A candidate spike is corrected only if (i) it lacks temporal persistence (no supporting increase at or ), (ii) it is not corroborated by any of the K nearest stations, (iii) it is inconsistent with auxiliary meteorological indicators (e.g., relative humidity or convective indices), and (iv) when available, it is not supported by contemporaneous radar or satellite precipitation estimates. Suspect spikes that do not meet these conditions are preserved and annotated with QC flags for downstream handling. This multi-stage procedure balances the need to remove spurious sensor errors while preserving meteorologically plausible extreme events.

For example, consider a transient spike in precipitation at station s. If at least two of the nearest stations exhibit aligned peaks within h and auxiliary signals such as relative humidity and convective index anomalies show coherent changes (e.g., a rise in relative humidity and a positive convective index anomaly), the spike is retained. In this case, we would report the focal station’s time series (mm ), the neighbor mean (mm ), and the aligned (%) and (unitless) to support the decision. Alternatively, in the case of an isolated spike at station s that lacks temporal persistence (i.e., no supporting increase at or ) and is not corroborated by any of the nearest stations, we would correct the spike. If the auxiliary meteorological indicators, such as relative humidity and convective indices, do not support the spike, it is replaced with the local temporal mean . The same set of auxiliary indicators, including , RH, and CI, would be reported to document the correction decision. These examples demonstrate how the QC rules are applied in practice, ensuring that extreme precipitation events are accurately handled and that meteorologically plausible anomalies are preserved.

5.5. Performance Evaluation

We compare the performance of DAHG with a set of representative baseline models on the task of 24 h ahead precipitation forecasting. The evaluation is conducted using four widely adopted regression metrics:

MAE (↓) (—lower is better (metric decreases indicate better performance)): mean absolute error, measuring average absolute deviation between predictions and observations;

RMSE (↓): root mean square error, penalizing large deviations more heavily;

(↑) (—higher is better (metric increases indicate better performance)): coefficient of determination, indicating the proportion of variance explained;

MedAE (↓): median absolute error, providing a more robust measure of a typical forecasting error that avoids instability around near-zero rainfall. In operational precipitation forecasting, an MAE or MedAE below 1.5 mm and an RMSE below 2.5 mm are generally regarded as good performance for regional-scale models. Values between 1.5–2.5 mm (MAE/MedAE) and 2.5–3.5 mm (RMSE) are considered acceptable, whereas errors above these ranges indicate poor reliability. For

, values greater than 0.80 are usually considered indicative of strong predictive skill, 0.60–0.80 as moderate/acceptable, and below 0.60 as weak. These thresholds are consistent with prior meteorological forecasting studies and provide practical context for interpreting our reported results [

44,

45].

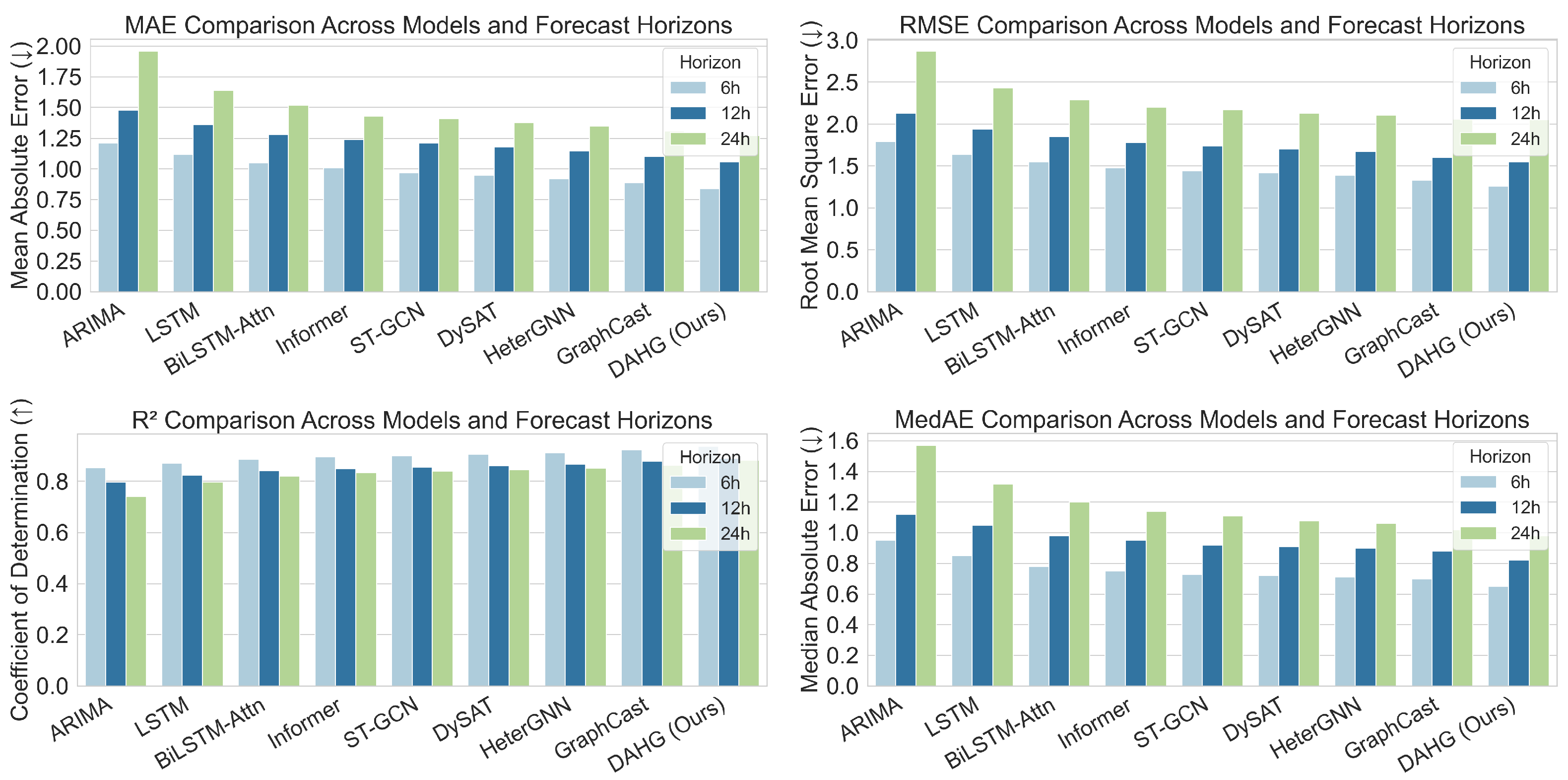

As shown in

Table 3, DAHG achieves consistently superior performance compared with traditional statistical models (e.g., ARIMA, SARIMA), sequential learning models (e.g., LSTM, BiLSTM-Attn), and graph-based methods (e.g., ST-GCN, DySAT, GraphCast). Across both ERA5-Land and MODIS NDVI datasets, DAHG yields lower errors (MAE, RMSE, and MedAE) and higher

values. These gains are modest in absolute terms (e.g.,

of 0.881 vs. 0.860 for GraphCast) but are statistically significant (paired

t-test,

) and consistent across all metrics and forecasting horizons.

The main advantage of DAHG arises from its unified design: Adaptive edge construction via reinforcement learning recovers missing structures, while meta-path guided embeddings capture heterogeneous dependencies more effectively. Combined with LSTM-based temporal modeling, this allows DAHG to exploit both fine-grained vegetation signals and broader atmospheric circulation patterns, leading to more robust predictions under incomplete observations.

To further illustrate robustness, we present a comprehensive visual comparison of prediction performance under three common forecasting horizons: 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h.

Figure 3 shows the variations in MAE, RMSE,

, and MedAE across all baseline methods. DAHG maintains stable improvements across horizons, highlighting its generalizability and making it more practical for operational forecasting. We repeat all experiments with five random seeds (affecting model weight initialization and data shuffling), report the mean and standard deviation, and include 95% confidence intervals for MAE and RMSE in

Table 4, further confirming stability.

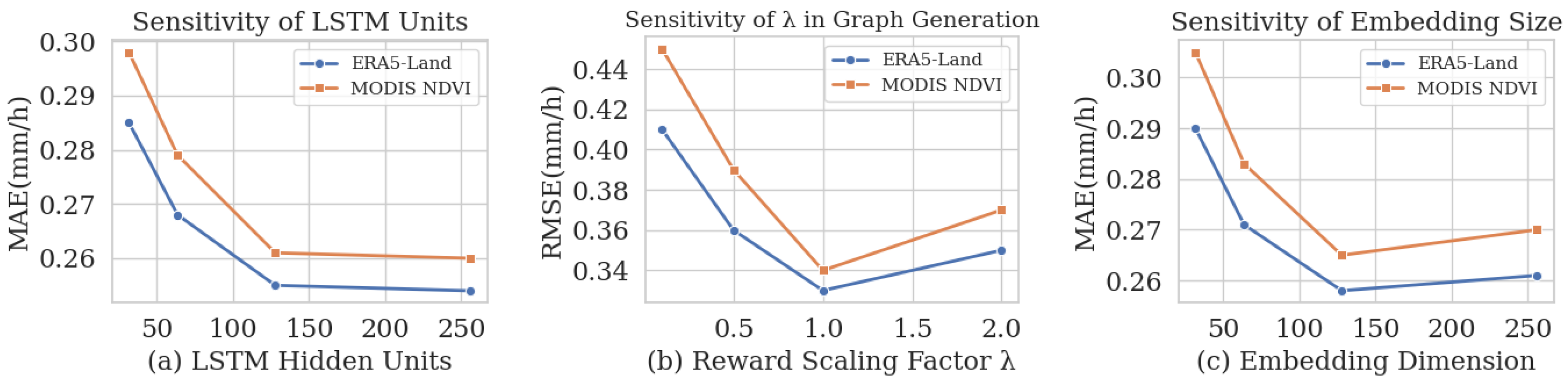

Finally, we assess computational efficiency. The reinforcement learning-based graph generation scales as

with the number of nodes

N, while the meta-path guided embedding scales linearly with relation types. In practice, based on 10 repeated runs on the ERA5-Land dataset with a batch size of 32 and sequence length of 24, DAHG requires about 1.3× the training time of a standard ST-GCN but converges faster due to contrastive pretraining (

Table 5). At inference, one 24 h prediction requires 0.21 s on a single NVIDIA A100 GPU, which is comparable to baseline GNN models such as GraphCast and DCRNN. These measurements demonstrate that the additional complexity is manageable and justified by the consistent performance improvements.

5.6. Baseline Setup and Training Details

To ensure a fair and transparent comparison, we carefully configure all baseline models with consistent inputs, spatial–temporal settings, and training budgets. The baselines cover statistical anchors, sequence models, and graph-based methods:

(1) Simple Anchors:Persistence: The most recent precipitation value at time t is directly used as the forecast for . Seasonal Climatology: The multi-year mean precipitation at the corresponding month and hour is used as the prediction.

(2) Sequence models: LSTM, BiLSTM-Attn, Temporal CNN, and Informer: These models take multivariate ERA5-Land meteorological variables and MODIS NDVI sequences as inputs, aligned on the same hourly grid. Sequence length is fixed to 24 h, with a prediction horizon of 24 h.

(3) Graph-Based Models: ST-GCN, ASTGCN, and DySAT: Precipitation stations (ERA5-Land grid cells) are nodes connected via spatial proximity. Node features include precipitation, temperature, humidity, wind, and NDVI. Sequence length is 24 h. GraphWaveNet: GraphWaveNet employs dilated graph convolutions with adaptive adjacency learning. It has the same node and feature setup as ST-GCN. HeterGNN: HeterGNN models heterogeneous station–variable–NDVI graphs with relation-aware aggregation. GraphCast: GraphCas was originally designed as a medium-range global model. To adapt it to our regional hourly setting, we crop ERA5-Land fields to the Eastern China domain, interpolate to 0.25° resolution, and restrict the horizon to 24 h. The model is retrained from scratch on the regional domain with the same ERA5-Land and MODIS inputs as DAHG.

All neural baselines are trained with an Adam optimizer, learning rate of , batch size of 64, and up to 100 epochs with early stopping. The hidden dimension is set to 128 for graph layers. For fairness, all models are trained on a single NVIDIA A100 GPU. On average, ST-GCN and GraphWaveNet converge within 2 h, while GraphCast requires around 6 h due to its larger architecture. DAHG takes approximately 2.6 h, which is 1.3× the cost of ST-GCN, but it is significantly faster than GraphCast.