Data Integration and Storage Strategies in Heterogeneous Analytical Systems: Architectures, Methods, and Interoperability Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Growing Heterogeneity in Analytical Ecosystems

1.2. Motivation for Unified Integration and Storage Strategies

1.3. Scope and Contributions of the Review

- It introduces an end-to-end cross-layer taxonomy that distinguishes integration mechanisms like schema matching, entity resolution, and semantic enrichment over a heterogeneous collection of storage methods and access models, including row/column stores, many families of NoSQL stores, cloud-native columnar stores, and lakehouse systems. This taxonomy clearly illustrates the interplay of workloads and architectures and their effects for governance and performance. By considering Section 2 and Section 3 simultaneously, practitioners can immediately map data unification to its concomitant storage point and the corresponding utilised query format.

- Operational planning of ETL, ELT, and data virtualisation/federation is laid out by considering popular process models and tools, followed by an analysis of the impact of optimisers and pushdown methods in integrated SQL engines. This creates a pragmatic architecture for the balancing of the latency, cost, and freshness of data across varying backends.

- Metadata, lineage, and schema evolution are highlighted as central constructs in ensuring reproducibility and dependability, in addition to formalising performance enhancements such as caching/materialisation and freshness/consistency control, in a checklist to support architectural decision-making.

- The findings are then consolidated with cross-domain examples such as enterprise lake/lakehouse, scientific integration, and public analytics domains, which leverage pragmatic patterns for managed, heterogeneous schema-on-read/write pipelines. These developments integrate embedded methodologies and infrastructure into a unified, decision-focused view for data teams and architects.

Positioning vs. Prior Surveys

1.4. Review Methodology

2. Foundations of Data Integration

2.1. Types of Heterogeneity: Schema, Semantic, Instance Levels

2.2. Schema Matching and Map Generation

2.3. Entity Resolution and Data Fusion

- Source prioritisation: Prioritisation of a primary source over other sources;

- Aggregation or voting: The combination of many values applying statistical methods;

- Provenance-aware fusion: the use of metadata in selecting values based on their timeliness, prevalence, or reliability.

2.4. Illustrative Resolution Scenarios and Workflows

2.4.1. Scenario A: Schema Name Mismatch (customer_id vs. client_no)

- Evidence gathering: Apply name-, structure-, and instance-based matching algorithms to recommend a correspondence amongst customer_id (RDBMS A) and client_no (RDBMS B).

- Candidate alignment: Check with domain ontology (e.g., “Customer” with one main identifier) to resolve homonyms and enforce cardinality/uniqueness constraints.

- Mapping synthesis: Develop an operational mapping (for instance, an SQL view or an ELT transformation) that presents client_no as customer_id while ensuring type harmonisation.

- Validation and lineage: Validate the precision and recall with a duly chosen sample. Keep the mapping, quality measures, and provenance in the metadata catalogue and implement it as a reusable module in the pipeline.

2.4.2. Scenario B: Instance-Level Ambiguity (Date “01/12/2025”)

- Policy: Adopt a canonical date format (ISO 8601, YYYY-MM-DD) as a data contract for analytical layers.

- Enforcement (schema-on-write where feasible): At ingestion, parse source dates using locale-aware parsers with explicit day/month disambiguation. Reject or quarantine unparsable records. Normalise to ISO.

- Hybrid fallback (schema-on-read): For immutable/legacy sources, apply a deterministic normaliser at query time with source-specific locale rules. Mark records with confidence and retain the raw value.

- Validation and observability: Define expectations (e.g., no ambiguous DD/MM vs. MM/DD overlaps) and monitor drift. Expose freshness and conformance metrics in the catalogue/lineage system.

2.4.3. Scenario C: Semantic Conflict (Salary = Gross vs. Net)

- Vocabulary alignment: Bind source attributes to ontology concepts (e.g., GrossAnnualSalary and NetMonthlySalary).

- Normalisation: Define transformation rules (unit/calendar/period adjustments) with explicit semantics. Compute derived measures only where definable.

- Query mediation: Expose a semantically consistent view (virtualised or materialised) that prevents cross-meaning joins. Annotate with provenance and assumptions in the catalogue.

2.5. Limitations and Possible Biases in Reviewed Methods

3. Storage Architectures for Analytical Workloads

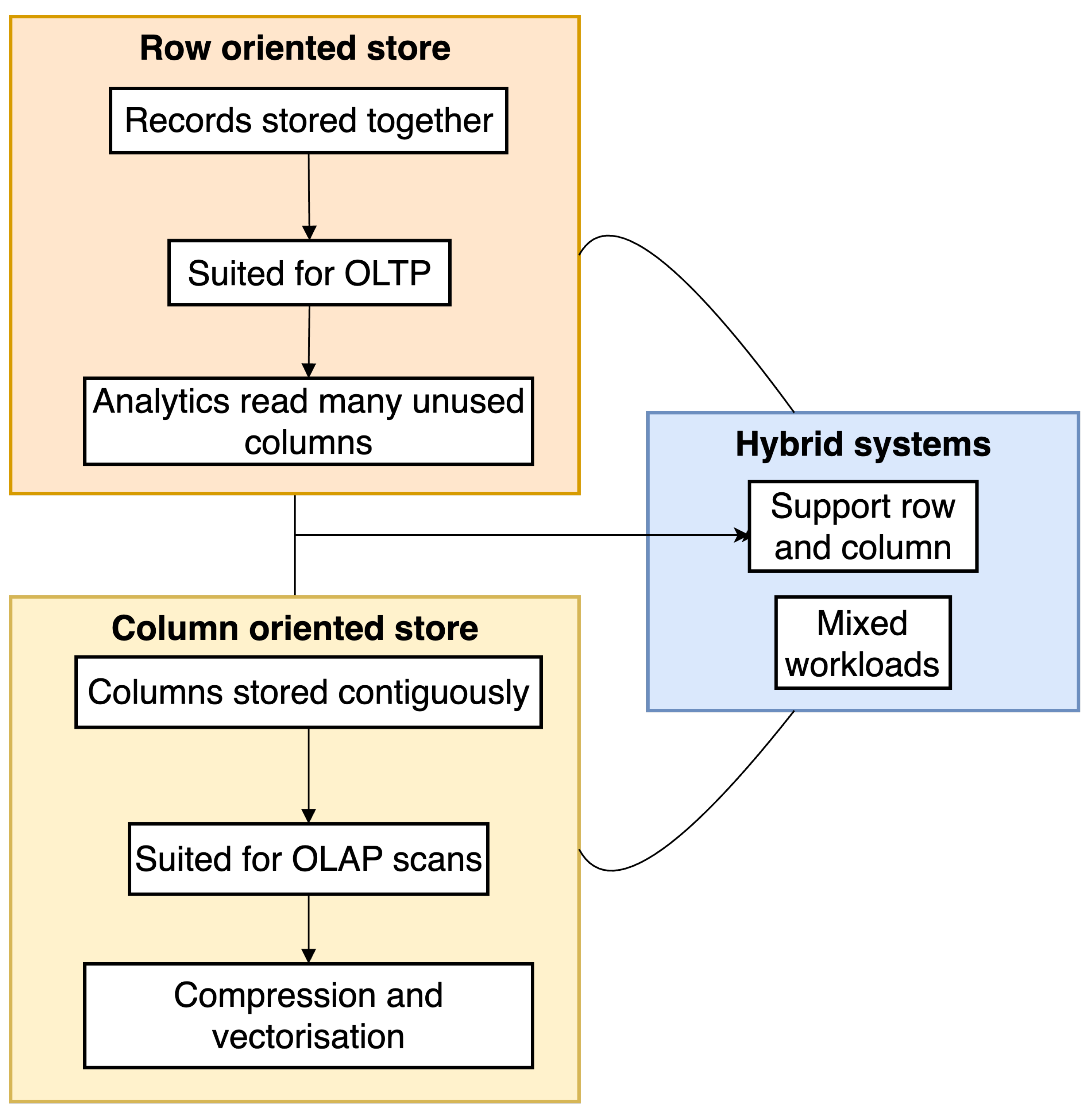

3.1. Row-Oriented and Column-Oriented Stores

3.2. Key-Value, Document, and Graph Databases

3.3. Cloud-Native Formats and Distributed File Systems (e.g., Parquet and Delta Lake)

4. Bridging Integration and Storage

4.1. ETL/ELT Pipelines and Data Virtualisation

Decision Guidance: ETL vs. ELT vs. Virtualisation

4.2. Federated Querying and Unified Query Engines

- Cost-centric query optimisation over various backend systems;

- Predicate pushdown, allowing filtering operations to be executed near their corresponding data sources;

- Parallel execution plans, enabling distributed scalability;

- Connector extensibility for custom data-source support.

4.3. Schema-on-Read vs. Schema-on-Write Trade-Offs

- Variability in schema interpretation across queries or individuals;

- In the phase of inquiry, complex transformations gain prominence;

- The issues involved in handling metadata in large datasets marked by dynamically changing schemas, requiring scrupulous analysis;

- Query performance becomes inefficient as a result of overly extended binding times.

5. Metadata, Lineage, and Semantic Interoperability

5.1. Metadata Management Frameworks (e.g., Apache Atlas and DataHub)

5.2. Ontology-Based Integration and Semantic Enrichment

5.3. Lineage Tracking and Schema Evolution Handling

- Table-level lineage describes the relationship between datasets, such as how table A is created from tables B and C.

- Column lineage provides precise mappings that show relationships between the transformation processes in individual columns.

- At the code level, family constructs create relationships between conversions related to specified activities or scripts, blending execution environments with parameter specifications for settings.

- Note and explain changes to the schema;

- Validate compatibility across pipeline stages;

- Enable both backward- and forward-compatible reading.

6. Performance, Scalability, and Consistency Challenges

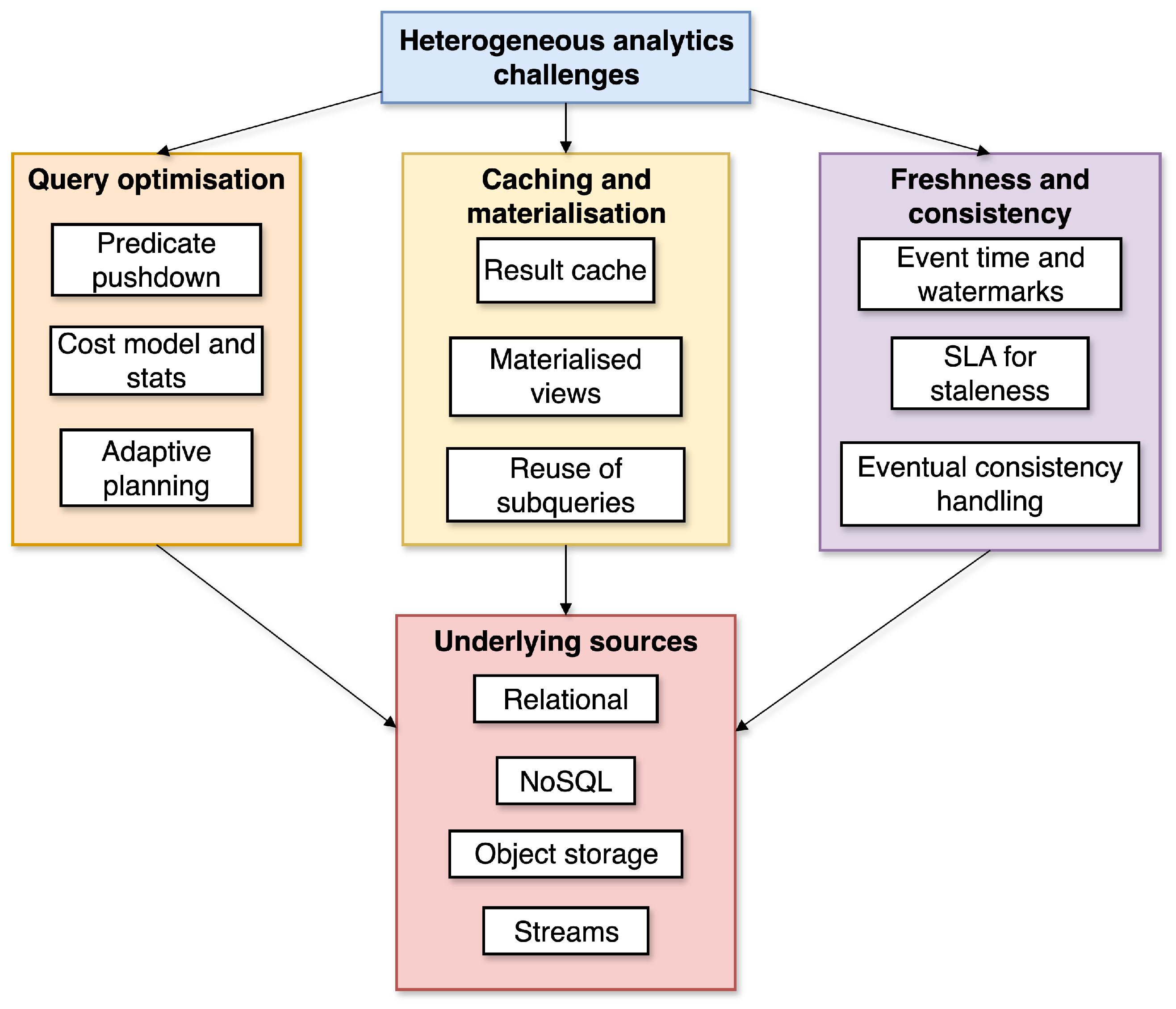

6.1. Query Optimisation Across Heterogeneous Sources

6.2. Materialisation and Caching Strategies

6.3. Data Freshness and Eventual Consistency Issues

6.4. Federation Overhead and Performance Tuning

- Second, planning with partial statistics can still be effective if the mediator exploits metadata to derive good subquery decompositions and join orders (Ontario “uses metadata … to generate optimised query plans” [5]) and, when available, sampling or progressive execution to refine estimates (see also systematisations in [6]).

- Third, movement minimisation is a transport problem: the choice of columnar/vectorised paths and batching reduces per tuple overhead. Contemporary evaluations of columnar runtimes and data paths emphasise the sustained throughput advantages of vectorised processing and columnar layouts for scans and aggregations [1,2].

- Fourth, materialisation and incremental maintenance mitigate repeated cross-source joins. Rather than fully recomputing federated joins/aggregations, incremental frameworks (e.g., DBSP) maintain views by applying deltas to compiled differential programs, reducing refresh latency and source load in steady state [76].

7. Applications and Case Studies

7.1. Enterprise Data Lakes and Lakehouses

7.2. Scientific Data Integration

7.3. Cross-Domain Data Pipelines in Public Sector Analytics

8. Future Directions

8.1. Towards Unified Analytical Fabrics

8.2. Metadata-Driven and Self-Describing Pipelines

8.3. AI-Assisted Integration and Auto-Schema Mapping

8.4. Ethical and Regulatory Directions

8.5. Limitations of This Review

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACID | Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| AWS | Amazon Web Services |

| CIDOC CRM | International Committee for Documentation Conceptual Reference Model |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| ELT | Extract–Load–Transform |

| ER | Entity Resolution |

| ETL | Extract–Transform,–Load |

| FIBO | Financial Industry Business Ontology |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HDFS | Hadoop Distributed File System |

| HL7 | Health Level Seven |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| MDM | Master Data Management |

| NoSQL | Not Only SQL |

| OLAP | Online Analytical Processing |

| OLTP | Online Transaction Processing |

| ORC | Optimised Row Columnar |

| OWL | Web Ontology Language |

| RBAC | Role-Based Access Control |

| RDF | Resource Description Framework |

| REST | Representational State Transfer |

| S3 | Simple Storage Service |

| SDMX | Statistical Data and Metadata Exchange |

| SIGMOD | ACM Special Interest Group on Management of Data |

| VLDB | Very Large Data Bases (Conference) |

| ICDE | IEEE International Conference on Data Engineering |

| TKDE | IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering |

| VLDBJ | The VLDB Journal |

| SLA | Service Level Agreement |

| SPARQL | SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language |

| SQL | Structured Query Language |

| SWEET | Semantic Web for Earth and Environmental Terminology |

| XML | Extensible Markup Language |

References

- Liu, C.; Pavlenko, A.; Interlandi, M.; Haynes, B. A Deep Dive into Common Open Formats for Analytical DBMSs. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2023, 16, 3044–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Hui, Y.; Shen, J.; Pavlo, A.; McKinney, W.; Zhang, H. An Empirical Evaluation of Columnar Storage Formats. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2023, 17, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrust, M.; Das, T.; Sun, L.; Yavuz, B.; Zhu, S.; Murthy, M.; Torres, J.; van Hovell, H.; Ionescu, A.; Łuszczak, A.; et al. Delta lake: High-performance ACID table storage over cloud object stores. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2020, 13, 3411–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, D.J.; Madden, S.R.; Hachem, N. Column-stores vs. row-stores: How different are they really? In Proceedings of the 2008 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–12 June 2008; pp. 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, R.; Koutras, C.; Quix, C.; Jarke, M. Data Lakes: A Survey of Functions and Systems. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 12571–12590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Corcoglioniti, F.; Lanti, D.; Mosca, A.; Xiao, G.; Xiong, J.; Calvanese, D. A systematic overview of data federation systems. Semant. Web 2024, 15, 107–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Meehan, T.; Schlussel, R.; Xie, W.; Basmanova, M.; Erling, O.; Rosa, A.; Fan, S.; Zhong, R.; Thirupathi, A.; et al. Presto: A Decade of SQL Analytics at Meta. Proc. ACM Manag. Data 2023, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potharaju, R.; Kim, T.; Song, E.; Wu, W.; Novik, L.; Dave, A.; Acharya, V.; Dhody, G.; Li, J.; Ramanujam, S.; et al. Hyperspace: The Indexing Subsystem of Azure Synapse. Proc. Vldb Endow. 2021, 14, 3043–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.L.; Srivastava, D. Big Data Integration; Synthesis Lectures on Data Management; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolnychyi, A.; Sun, C.; Tanimura, K.; Spitzer, R.; Blue, R.; Ho, S.; Gu, Y.; Lakkundi, V.; Tsai, D. Petabyte-Scale Row-Level Operations in Data Lakehouses. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2024, 17, 4159–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alma’aitah, W.Z.; Quraan, A.; AL-Aswadi, F.N.; Alkhawaldeh, R.S.; Alazab, M.; Awajan, A. Integration Approaches for Heterogeneous Big Data: A Survey. Cybern. Inf. Technol. 2024, 24, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedreira, P.; Erling, O.; Basmanova, M.; Wilfong, K.; Sakka, L.; Pai, K.; He, W.; Chattopadhyay, B. Velox: Meta’s unified execution engine. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2022, 15, 3372–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Gröger, C.; Lutsch, A.; Schwarz, H.; Mitschang, B. The Lakehouse: State of the Art on Concepts and Technologies. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoudi, Z.; Quiané-Ruiz, J.A. Unified Data Analytics: State-of-the-Art and Open Problems. Proc. Vldb Endow. 2022, 15, 3778–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Han, X.; Fan, J.; Chai, C.; Tang, N.; Li, G.; Du, X. Cost-Effective In-Context Learning for Entity Resolution: A Design Space Exploration. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Utrecht, The Netherlands, 13–16 May 2024; pp. 3696–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zeng, W.; Tang, J.; Huang, H.; Zhao, X. Active in-context learning for cross-domain entity resolution. Inf. Fusion 2025, 117, 102816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, M.; Martinez, D.; Arideh, M.; Mosquera, R. Ontology matching with Large Language Models and prioritized depth-first search. Inf. Fusion 2025, 123, 103254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei Giglou, H.; D’Souza, J.; Engel, F.; Auer, S. LLMs4OM: Matching Ontologies with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Semantic Web: ESWC 2024 Satellite Events, Hersonissos, Greece, 26–30 May 2024; Meroño Peñuela, A., Corcho, O., Groth, P., Simperl, E., Tamma, V., Nuzzolese, A.G., Poveda-Villalón, M., Sabou, M., Presutti, V., Celino, I., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Barbon Junior, S.; Ceravolo, P.; Groppe, S.; Jarrar, M.; Maghool, S.; Sèdes, F.; Sahri, S.; Van Keulen, M. Are Large Language Models the New Interface for Data Pipelines? In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Big Data in Emergent Distributed Environments, Santiago, Chile, 9–15 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidu, A.; Ciavotta, M.; Paoli, F.D. LLM-Based DAG Creation for Data Enrichment Pipelines in SemT Framework. In Proceedings of the Service-Oriented Computing—ICSOC 2024 Workshops: ASOCA, AI-PA, WESOACS, GAISS, LAIS, AI on Edge, RTSEMS, SQS, SOCAISA, SOC4AI and Satellite Events, Tunis, Tunisia, 3–6 December 2024; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahm, E.; Bernstein, P.A. A Survey of Approaches to Automatic Schema Matching. VLDB J. 2001, 10, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiholder, J.; Naumann, F. Data Fusion. ACM Comput. Surv. 2008, 41, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, J.; Chiticariu, L.; Tan, W. Provenance in Databases: Why, How, and Where. Found. Trends Databases 2009, 1, 379–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euzenat, J.; Shvaiko, P. Ontology Matching, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen, P. Data Matching: Concepts and Techniques for Record Linkage, Entity Resolution, and Duplicate Detection; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, G.; Skoutas, D.; Thanos, E.; Palpanas, T. Blocking and Filtering Techniques for Entity Resolution: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buneman, P.; Khanna, S.; Tan, W. Why and Where: A Characterization of Data Provenance. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Database Theory (ICDT), London, UK, 4–6 January 2001; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 1973, pp. 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8601-2:2019; Date and Time—Representations for Information Interchange—Part 2: Extensions. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Confirmed 2024; Amendment 1:2025.

- Bellahsene, Z.; Bonifati, A.; Rahm, E. Schema Matching and Mapping. In Schema Matching and Mapping; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parciak, M.; Vandevoort, B.; Neven, F.; Peeters, L.M.; Vansummeren, S. LLM-Matcher: A Name-Based Schema Matching Tool using Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2025 International Conference on Management of Data, Berlin, Germany, 22–27 June 2025; pp. 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Meyer, O.; Oberle, M.; Bauernhansl, T. Dual data mapping with fine-tuned large language models and asset administration shells toward interoperable knowledge representation. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 91, 102837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.A.; Fischer, M.J. The String-to-String Correction Problem. J. ACM 1974, 21, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.; da Silva, A. A Study on Machine Learning Techniques for the Schema Matching Network Problem. J. Braz. Comput. Soc. 2021, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, L.; Velegrakis, Y.; Miller, R.J.; Hernández, M.A.; Fagin, R. Chapter 52—Translating Web Data. In VLDB ’02: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Very Large Databases, Hong Kong, China, 20–23 August 2002; Bernstein, P.A., Ioannidis, Y.E., Ramakrishnan, R., Papadias, D., Eds.; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binette, O.; Steorts, R.C. (Almost) All of Entity Resolution. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabi8021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, A.; Neumann, T. HyPer: A Hybrid OLTP&OLAP Main Memory Database System Based on Virtual Memory Snapshots. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE 27th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Hannover, Germany, 11–16 April 2011; pp. 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, A.; Fuller, M.; Varadarajan, R.; Tran, N.; Vandiver, B.; Doshi, L.; Bear, C. The Vertica Analytic Database: C-Store 7 Years Later. Proc. Vldb Endow. 2012, 5, 1790–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, R.; Schreiber, T.; Yatsishin, I.; Dahimene, R.; Milovidov, A. ClickHouse—Lightning Fast Analytics for Everyone. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2024, 17, 3731–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lin, C.; Papakonstantinou, Y.; Swanson, S. An Experimental Study of Bitmap Compression vs. Inverted List Compression. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Conference on Management of Data, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–19 May 2017; pp. 993–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambi, S.; Lemire, D.; Kaser, O.; Godin, R. Better bitmap performance with Roaring bitmaps. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2016, 46, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, T.; Pergolesi, M. The Impact of Columnar File Formats on SQL-on-Hadoop Engine Performance: A Study on ORC and Parquet. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2020, 32, e5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, D.; Madden, S.; Ferreira, M. Integrating Compression and Execution in Column-Oriented Database Systems. In Proceedings of the 2006 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Chicago, IL, USA, 27–29 June 2006; pp. 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, V.; Färber, F.; Lehner, W.; Cha, S.K.; Peh, T.; Bornhövd, C. Efficient transaction processing in SAP HANA database: The end of a column store myth. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 20–24 May 2012; pp. 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCandia, G.; Hastorun, D.; Jampani, M.; Kakulapati, G.; Lakshman, A.; Pilchin, A.; Sivasubramanian, S.; Vosshall, P.; Vogels, W. Dynamo: Amazon’s highly available key-value store. In Proceedings of the Twenty-First ACM SIGOPS Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, Stevenson, WA, USA, 14–17 October 2007; pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, P.; Cheng, E.; Gawlick, D.; O’Neil, E. The Log-Structured Merge-Tree (LSM-Tree). Acta Inform. 1996, 33, 351–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idreos, S.; Callaghan, M. Key-Value Storage Engines. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Portland, OR, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 2667–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaiee, S.; Altowim, Y.; Altwaijry, H.; Behm, A.; Borkar, V.; Bu, Y.; Carey, M.; Cetindil, I.; Cheelangi, M.; Faraaz, K.; et al. AsterixDB: A scalable, open source BDMS. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2014, 7, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, I.; Sá, F.; Bernardino, J. Performance Evaluation of NoSQL Document Databases: Couchbase, CouchDB, and MongoDB. Algorithms 2023, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besta, M.; Gerstenberger, R.; Peter, E.; Fischer, M.; Podstawski, M.; Barthels, C.; Alonso, G.; Hoefler, T. Demystifying Graph Databases: Analysis and Taxonomy of Data Organization, System Designs, and Graph Queries. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, N.; Green, A.; Guagliardo, P.; Libkin, L.; Lindaaker, T.; Marsault, V.; Plantikow, S.; Rydberg, M.; Selmer, P.; Taylor, A. Cypher: An Evolving Query Language for Property Graphs. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Management of Data, Houston, TX, USA, 10–15 June 2018; pp. 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnik, S.; Gubarev, A.; Long, J.J.; Romer, G.; Shivakumar, S.; Tolton, M.; Vassilakis, T. Dremel: Interactive analysis of web-scale datasets. Commun. ACM 2011, 54, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, A.; Rieger, M.; Neumann, T. Nested Parquet Is Flat, Why Not Use It? How To Scan Nested Data With On-the-Fly Key Generation and Joins. Proc. ACM Manag. Data 2025, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghemawat, S.; Gobioff, H.; Leung, S. The Google File System. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP), Bolton Landing, NY, USA, 19–22 October 2003; pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvachko, K.; Kuang, H.; Radia, S.; Chansler, R. The Hadoop Distributed File System. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 26th Symposium on Mass Storage Systems and Technologies (MSST), Incline Village, NV, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, R.; Traverso, M.; Sundstrom, D.; Phillips, D.; Xie, W.; Sun, Y.; Yegitbasi, N.; Jin, H.; Hwang, E.; Shingte, N.; et al. Presto: SQL on Everything. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 35th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Macao, China, 8–11 April 2019; pp. 1802–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliadis, P. A Survey of Extract–Transform–Load Technology. Int. J. Data Warehous. Min. 2009, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.R.; Coelho, L.; Oliveira, J.L. BIcenter: A Collaborative Web ETL Solution Based on a Reflective Software Approach. SoftwareX 2021, 16, 100892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, B.; Valduriez, P.; Bondiombouy, C.; Jiménez, R.; Pau, R.; Pereira, J. Cloudmdsql: Querying heterogeneous cloud data stores with a common language. Distrib. Parallel Databases 2015, 34, 463–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behm, A.; Palkar, S.; Agarwal, U.; Armstrong, T.; Cashman, D.; Dave, A.; Greenstein, T.; Hovsepian, S.; Johnson, R.; Sai Krishnan, A.; et al. Photon: A Fast Query Engine for Lakehouse Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Management of Data, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 12–17 June 2022; pp. 2326–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenblas, M.; Nadeau, J. Apache Drill: Interactive Ad-Hoc Analysis at Scale. Big Data 2013, 1, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, R.; Berti-Equille, L.; Darmont, J. Modeling metadata in data lakes—A generic model. Data Knowl. Eng. 2021, 134, 101931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschel, M.; Diestelkämper, R.; Ben Lahmar, H. A survey on provenance: What for? What form? What from? Vldb J. 2017, 26, 881–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, N.; Otto, B. Data Catalogs in the Enterprise: Applications and Integration. Datenbank-Spektrum 2023, 23, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, T.G.O. The Gene Ontology resource: Enriching a GOld mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D325–D334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskin, R.G.; Pan, M.J. Knowledge representation in the Semantic Web for Earth and Environmental Terminology (SWEET). Comput. Geosci. 2005, 31, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccolucci, F.; Doerr, M. Extending, mapping, and focusing the CIDOC CRM. Int. J. Digit. Libr. 2017, 18, 251–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, G.G.; Tuzovsky, A.F.; Aksenova, N.V. Application of the Financial Industry Business Ontology (FIBO) for development of a financial organization ontology. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 803, 012116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, J.C.; Kreda, D.A.; Mandl, K.D.; Kohane, I.S.; Ramoni, R.B. SMART on FHIR: A standards-based, interoperable apps platform for electronic health records. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrandečić, D.; Krötzsch, M. Wikidata: A free collaborative knowledgebase. Commun. Acm 2014, 57, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizer, C.; Lehmann, J.; Kobilarov, G.; Auer, S.; Becker, C.; Cyganiak, R.; Hellmann, S. DBpedia—A crystallization point for the Web of Data. J. Web Semant. 2009, 7, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, L.; Groth, P.; Cheney, J.; Lebo, T.; Miles, S. The rationale of PROV. J. Web Semant. 2015, 35, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Niu, S.; Ding, B.; Kraska, T.; Luo, J.; Luo, W.; Tang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, J. Learned Cardinality Estimation: An In-depth Study. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 12–17 June 2022; pp. 1214–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, R.; Papaemmanouil, O. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Join Order Enumeration. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Exploiting Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Data Management (aiDM@SIGMOD), Houston, TX, USA, 10 June 2018; pp. 3:1–3:4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, R.; Negi, P.; Mao, H.; Tatbul, N.; Alizadeh, M.; Kraska, T. Bao: Making Learned Query Optimization Practical. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD), Xi’an, China, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 1275–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Y.; Kennedy, O.; Koch, C.; Nikolic, M. DBToaster: Higher-order Delta Processing for Dynamic, Frequently Fresh Views. Proc. Vldb Endow. 2012, 5, 968–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiu, M.; Chajed, T.; McSherry, F.; Ryzhyk, L.; Tannen, V. DBSP: Automatic Incremental View Maintenance for Rich Query Languages. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2023, 16, 1601–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghandour, I.; Aboulnaga, A. ReStore: Reusing Results of MapReduce Jobs. Proc. Vldb Endow. 2012, 5, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrust, M.; Das, T.; Torres, J.; Yavuz, B.; Zhu, S.; Xin, R.; Ghodsi, A.; Stoica, I.; Zaharia, M. Structured Streaming: A Declarative API for Real-Time Applications in Apache Spark. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Management of Data, Houston, TX, USA, 10–15 June 2018; pp. 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akidau, T.; Begoli, E.; Chernyak, S.; Hueske, F.; Knight, K.; Knowles, K.; Mills, D.; Sotolongo, D. Watermarks in stream processing systems: Semantics and comparative analysis of Apache Flink and Google cloud dataflow. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2021, 14, 3135–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogels, W. Eventually Consistent. Commun. ACM 2009, 52, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelter, S.; Biessmann, F.; Januschowski, T.; Salinas, D.; Seufert, S.; Krettek, A. Automating Large-Scale Data Quality Verification. Proc. Vldb Endow. 2018, 11, 1781–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, N.; Ilayperuma, T.; Arachchige, J.J.; Bukhsh, F.A.; Daneva, M. The evolution of data storage architectures: Examining the secure value of the data lakehouse. J. Data, Inf. Manag. 2024, 6, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, T.J.; Tripodi, I.J.; Stefanski, A.L.; Cappelletti, L.; Taneja, S.B.; Wyrwa, J.M.; Casiraghi, E.; Matentzoglu, N.A.; Reese, J.; Silverstein, J.C.; et al. An open source knowledge graph ecosystem for the life sciences. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowan, T.A.; Horel, J.D.; Jacques, A.A.; Kovac, A. Using Cloud Computing to Analyze Model Output Archived in Zarr Format. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2022, 39, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Basurto-Lozada, D.; Besson, S.; Bogovic, J.; Bragantini, J.; Brown, E.M.; Burel, J.; Moreno, X.C.; Medeiros, G.d.; Diel, E.E.; et al. Ome-zarr: A cloud-optimized bioimaging file format with international community support. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2023, 160, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A.; Javidroozi, V. Smart City Development: Data Sharing vs. Data Protection Legislations. Cities 2024, 148, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmi, A. OpenRefine: An Approachable Tool for Cleaning and Harmonizing Bibliographical Data. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2827, 030006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willekens, F. Programmatic Access to Open Statistical Data for Population Studies: The SDMX Standard. Demogr. Res. 2023, 49, 1117–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayali, M.; Lykov, A.; Fountalis, I.; Vasiloglou, N.; Olteanu, D.; Suciu, D. Chorus: Foundation Models for Unified Data Discovery and Exploration. Proc. Vldb Endow. 2024, 17, 2104–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipzig, J.; Nüst, D.; Hoyt, C.T.; Ram, K.; Greenberg, J. The role of metadata in reproducible computational research. Patterns 2021, 2, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T. Benchmarking Apache Arrow Flight - A wire-speed protocol for data transfer, querying and microservices. In Proceedings of the Benchmarking in the Data Center: Expanding to the Cloud, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2–6 April 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shraga, R.; Gal, A. PoWareMatch: A Quality-aware Deep Learning Approach to Improve Human Schema Matching. J. Data Inf. Qual. 2022, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shin, B.; Choi, J.D.; Ho, J.C. SMAT: An Attention-Based Deep Learning Solution to the Automation of Schema Matching. In Advances in Databases and Information Systems (ADBIS 2021); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 12843, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; pp. 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union, E. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, 679, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on harmonised rules on artificial intelligence. Off. J. Eur. Union 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj/eng (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Álvarez, J.M.; Colmenarejo, A.B.; Elobaid, A.; Fabbrizzi, S.; Fahimi, M.; Ferrara, A.; Ghodsi, S.; Mougan, C.; Papageorgiou, I.; Lobo, P.R.; et al. Policy advice and best practices on bias and fairness in ai. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2024, 26, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey | Primary Focus | Coverage | What This Review Adds |

|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | Data lake functions/systems | Ingestion, metadata, governance, and lake infrastructure | Cross-layer linkage of schema/ER/semantics with storage + performance/governance levers |

| [6] | Federation architectures and capabilities | Connectors, query translation, and execution models | Integration of federation with storage models, ETL/ELT, and performance tuning |

| [13] | Lakehouse concepts/technologies | Transactional tables, open formats, and hybrid lake/warehouse design | Comparative role of lakehouses among integration strategies; lineage/governance integration |

| [14] | Unified analytics vision | Fabrics, abstractions, and open challenges | Operational taxonomy, workflows, domain case studies, and incorporation of 2024–2025 AI instruments |

| [9] | Big data integration foundations | Schema matching, mapping, and fusion | Updated synthesis with recent metadata catalogues, lakehouses, and federated engines |

| Heterogeneity Type | Description and Example | Resolution Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Schema heterogeneity | Differing data schemas (e.g., customer_id vs. client_no) | Schema mapping and translation [21] |

| Semantic heterogeneity | Same term has different meanings (e.g., salary = gross vs. net) | Ontology mapping [24] |

| Instance-level heterogeneity | Different formats/values (e.g., dates 01/12/2025 vs. 2025-12-01) | Data cleaning and normalisation [25] |

| Matcher Type | Matching Strategy | Representative Work |

|---|---|---|

| Name-based (lexical) | Compares schema element names (string similarity and synonyms) | [32] |

| Structure-based | Exploits schema structure (hierarchies and parent–child structures) | [29] |

| Instance-based | Uses actual data values (overlapping ranges and distributions) | [21] |

| Ambiguous Input | Enforced Rule (Contract) | Canonical Form | Validation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01/12/2025 (unknown locale) | YYYY-MM-DD (ISO 8601) | 2025-12-01 or reject | Expectation checks, quarantine on ambiguity |

| 12/01/2025 (unknown locale) | YYYY-MM-DD | 2025-01-12 or reject | Locale profile, confidence tagging |

| 2025/12/01 | YYYY-MM-DD | 2025-12-01 | Strict pattern enforcement |

| NoSQL Category | Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Key-value store | Data stored as key/value pairs, optimised for lookups | Amazon DynamoDB and Redis |

| Document store | Semi-structured JSON-like documents and flexible schema | MongoDB and Couchbase |

| Graph database | Data as nodes and edges; suited for relationships | Neo4j and Amazon Neptune |

| Metric | Key-Value (e.g., Dynamo) | Document (e.g., MongoDB/CouchDB/Couchbase) | Graph DBs (LPG/RDF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency vs. availability | “Always writable” design, quorum-tuned R/W, eventual consistency with vector clocks, and hinted handoff for node outages | Stronger per node consistency, cluster settings vary by product, and designed for CRUD with JSON/BSON | Transaction models vary; many support ACID for OLTP, and global analytics are typically read-only |

| Partitioning/scale-out | Consistent hashing, virtual nodes, sloppy quorum, and seamless node add/remove function | Sharding and replica sets are common, as well as per collection partitioning | Sharding/replication depend on the engine; many native stores optimize locality for traversals |

| Write path | Fast, partition-local writes; durability ensured via a configurable W | Bulk inserts and high-rate CRUD; durability ensured via journaling/replica sync | OLTP writes supported (engine-dependent), and heavy analytics often separated from the write path |

| Scan/range queries | Limited (key-oriented); range needs secondary/indexed paths | YCSB: MongoDB has the best overall runtime, while a scan-heavy workload makes CouchDB faster and CouchDB scales best with threads | Scans expressed via label/property predicates; the cost depends on index design; not a primary strength vs. documents |

| Traversals/locality | Multi-hop traversals require app-level joins or pre-materialization | Multi-hop joins across collections are costly and not traversal-centric | Native adjacency (AL and direct pointers), and traversal cost grows with the number of visited subgraphs, not graph size; suited to path/pattern queries |

| Indexing | Primary key and optional secondary indexes for ranges/filters | Rich secondary and compound indexes; text/geo often available | Structural (neighbourhood) + data indexes; languages expose pattern/path operators |

| Query languages | KV APIs and app-side composition | Aggregation pipelines and SQL-like DSLs | SPARQL (RDF), Cypher/Gremlin (LPG), and mature pattern/path semantics |

| Metric | Parquet | ORC | Arrow/Feather |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compression ratio | Strong overall compression, especially with dictionary encoding | Often higher compression on structured/numeric workloads | Not a storage format; minimal compression; focuses on speed |

| Scan/decoding speed | Faster end-to-end decoding in mixed workloads | Slightly slower, but predicate evaluation is stronger | Fastest (de)serialisation throughput; zero-copy in-memory |

| Predicate pushdown/skipping | Effective but limited by column statistics | Fine-grained zone maps yield strong selective query performance | Not applicable (in-memory only) |

| Nested data handling | R/D-level encoding and efficient leaf-only access | Presence/length streams; overhead increases with depth | Dependent on producer/consumer; no disk encoding |

| Workload trade-offs | Performs best on wide tables and vectorised execution | Strong on narrow/deep workloads with high selectivity | Best as interchange for ML/analytics pipelines |

| Approach | Process | Typical Tools |

|---|---|---|

| ETL (Extract–Transform–Load) | Extract → Transform → Load into data warehouse | Talend, Informatica, and Pentaho |

| ELT (Extract–Load–Transform) | Extract → Load (raw) → Transform later in data lake | Hadoop HDFS, Spark, and dbt |

| Data virtualisation | Virtual layer integrates sources in real time | Denodo, Dremio, and Presto/Trino |

| Metric | Presto | Trino | Drill | Starburst |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connector support | Broad set of connectors and production deployments at scale | Broad OSS connector base; fork of Presto with added features | Schema-free connectors for JSON, NoSQL, and files | Commercial distribution; adds enterprise connectors and governance |

| Predicate pushdown | Supported across RDBMS, Hive, and columnar formats | Supported across most connectors | Predicate pushdown for JSON and columnar data | Extended pushdown support with enterprise optimisations |

| Cost-based optimisation | CBO with table/column statistics and an adaptive join order | Cost-aware planning with statistics integration | Primarily rule-based; limited CBO | Enterprise-grade CBO with workload-aware tuning |

| Execution model | Massively parallel and pull-based execution | Similar to Presto; optimised scheduling | Vectorised operator pipeline | Enhanced parallelism and workload management |

| Caching and materialisation | Result caching, materialised views, and SSD spill options | Spill to disk; MV support in OSS is limited | Reader-level pruning and limited caching features | Adds advanced caching and MV rewriting |

| Fault tolerance | Recoverable grouped execution; Presto-on-Spark variant | Retry-based external FT extensions | No built-in query recovery | Enterprise-level FT and workload isolation |

| Production use evidence | Exabyte-scale at Meta; interactive + ETL workloads | Large-scale OSS and enterprise deployments | Interactive ad hoc analysis over schema-free data | Widely adopted in regulated industries |

| Platform | Architecture & Integration | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Apache Atlas | Metadata repository, native to Hadoop | REST APIs, lineage, audit logging, and RBAC |

| LinkedIn DataHub | Distributed service; platform-agnostic | Metadata ingestion, search UI, and versioning |

| Lyft Amundsen | Graph-backed discovery | Lineage graphs, discovery UI, and access control |

| Overhead Locus (Where It Appears) | Tuning Lever (How It Is Mitigated) |

|---|---|

| Connector translation gaps and heterogeneous engines (Spark/Presto variants in Squerall) | Connector-aware planning and dialect rewriting and per connector rules/pushdown (Ontario’s profile-driven subqueries and Squerall’s mediator mapping) [5]. |

| Partial statistics; mediator lacks global distributions | Metadata-guided plan generation (Ontario uses metadata to generate optimised plans), progressive refinement, and survey-catalogued strategies [5,6]. |

| Row-oriented transfer and fine-grained serialisation | Vectorised/columnar paths and batching for sustained scan/aggregation throughput [1,2]. |

| Repeated cross-source joins; freshness vs. latency | Materialised views of “hot” joins with incremental refresh (differential/delta maintenance) [76]. |

| Orchestration via LLMs (NLQ/translation) | Guardrails: verified translations and fallbacks; LLM use where determinism is not critical (noting 54.89% text-to-SQL execution accuracy for GPT-4) [19]. |

| Workload skew across sources | Hybridisation (persist stable, high-value slices in lakehouse/warehouse and federate the remainder) [5,11,82]. |

| Taxonomy Element | Applications (Role and Where in Text) |

|---|---|

| Schema matching and mapping (Section 2.2) | Harmonise identifiers/attributes across sources. Enterprise lakehouse keys via SQL/ELT (Section 7.1). Public registries (Section 7.3). |

| Entity resolution and fusion (Section 2.3) | Deduplicate/link records. Unified entities. Enterprise CRM+transactions (Section 7.1). Public person/org linkage (Section 7.3). |

| Semantic enrichment and ontologies (Section 5.2) | Disambiguation of meaning, standards-based queries, scientific knowledge graphs (Section 7.2), and Public SDMX alignment (Section 7.3). |

| Metadata catalogues and lineage (Section 5.1 and Section 5.3) | Discoverability, governance, reproducibility, enterprise governance (Section 7.1), and scientific provenance (Section 7.2). |

| Storage models (row/column/NoSQL-Section 3) | Fit workloads, hybrid query plans, enterprise columnar lakehouse, and scientific/public doc/graph as adjunct (Section 7.1, Section 7.2 and Section 7.3). |

| Federated SQL and virtualisation (Section 4.2) | Cross-store analytics without relocation, enterprise Trino-based joins (Section 7.1), and public inter-agency dashboards (Section 7.3). |

| Schema-on-read/write and hybrid (Section 4.3) | Contracts vs. flexibility, canonicalisation (e.g., dates), and public regulated pipelines (Section 7.3). |

| Performance levers (Section 6) | Cost/latency optimisation, freshness, dashboards, and SLAs (Section 7). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koukaras, P. Data Integration and Storage Strategies in Heterogeneous Analytical Systems: Architectures, Methods, and Interoperability Challenges. Information 2025, 16, 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110932

Koukaras P. Data Integration and Storage Strategies in Heterogeneous Analytical Systems: Architectures, Methods, and Interoperability Challenges. Information. 2025; 16(11):932. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110932

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoukaras, Paraskevas. 2025. "Data Integration and Storage Strategies in Heterogeneous Analytical Systems: Architectures, Methods, and Interoperability Challenges" Information 16, no. 11: 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110932

APA StyleKoukaras, P. (2025). Data Integration and Storage Strategies in Heterogeneous Analytical Systems: Architectures, Methods, and Interoperability Challenges. Information, 16(11), 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110932