Abstract

This study explores the application of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in financial risk forecasting, aiming to assess its potential in enhancing both the accuracy and interpretability of predictive models. Traditional methods often struggle with the complexity and nonlinearity of financial data, whereas generative AI—such as large language models and generative adversarial networks (GANs)—offers novel solutions to these challenges. The study begins with a comprehensive review of current research on generative AI in financial risk prediction, with a focus on its roles in data augmentation and feature extraction. It then investigates techniques such as Generative Adversarial Explanation (GAX) to evaluate their effectiveness in improving model interpretability. Case studies demonstrate the practical value of generative AI in real-world financial forecasting and quantify its contribution to predictive accuracy. Furthermore, the study identifies key challenges—including data quality, model training costs, and regulatory compliance—and proposes corresponding mitigation strategies. The findings suggest that generative AI can significantly improve the accuracy and interpretability of financial risk models, though its adoption must be carefully managed to address associated risks. This study offers insights and guidance for future research in applying generative AI to financial risk forecasting.

1. Introduction

Traditional approaches to financial risk forecasting have long relied on statistical and econometric models, such as time series analysis, regression analysis, and discriminant analysis [1]. However, these methods face significant limitations when dealing with nonlinear, high-dimensional, and complex interrelated data. For instance, conventional models struggle to capture the influence of microstructural market changes and investor sentiment fluctuations on financial risk [2]. Moreover, they often depend on manually crafted features and expert knowledge, making it difficult to extract deep insights hidden within vast and growing datasets. As financial markets become increasingly complex and data volumes continue to expand, the effectiveness of traditional forecasting models is being challenged.

The rapid advancement of generative artificial intelligence (AI) offers new opportunities for financial risk forecasting. Generative AI models—such as generative adversarial networks (GANs) and large language models (LLMs)—possess powerful capabilities in data generation, feature extraction, and pattern recognition [3,4]. By learning from historical financial data, these models can simulate various market scenarios, enabling more comprehensive assessments of potential risks. They can also automatically identify key risk factors, reducing the need for manual intervention while improving forecasting efficiency and accuracy. Consequently, the integration of generative AI into financial risk forecasting not only represents a natural progression in technological development but also serves as a strategic approach to enhancing financial risk management. More accurate risk assessments can help financial institutions improve asset allocation, hedge against potential losses, and meet regulatory requirements—contributing to the overall stability and health of financial markets.

Recent research (2021–2024) underscores AI’s expanding role in financial risk analytics—ranging from GAN-based methods that enhance credit risk assessment under data scarcity [5], through deep learning architectures that materially improve fraud detection performance [6,7], to supervisory frameworks that foreground explainability and model governance in prudential oversight [8,9,10]. Building on this literature, our study integrates generative modeling with privacy-preserving mechanisms to jointly address data imbalance and confidentiality constraints in credit-risk evaluation.

This study aims to explore the potential of generative AI in financial risk forecasting and proposes improvements to address the limitations of existing methods. It provides a comprehensive review of current applications of generative AI models—particularly GANs and LLMs—in the financial domain [3,4]. Special attention is given to the use of generative models for data augmentation, examining how GANs can produce high-quality synthetic data to mitigate data scarcity and imbalance in financial datasets [11]. The study also investigates how deep learning models can be leveraged to automatically extract key features from financial data, thereby improving prediction accuracy.

Furthermore, it develops and optimizes financial risk forecasting models based on generative AI, including both GAN- and LLM-based architectures, and validates their performance through empirical analysis. Case studies are presented to demonstrate real-world applications, such as credit risk evaluation, fraud detection, and market risk warning systems. Finally, the study addresses key challenges associated with generative AI in financial forecasting—including data quality, model training costs, and regulatory compliance—and proposes corresponding strategies. Future research directions are also discussed, including enhancing model interpretability, integrating generative AI with other technologies, and expanding its application to broader financial contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Applications of Generative AI Models in Financial Risk Forecasting

Generative adversarial networks (GANs), as powerful generative models, have shown significant potential in the domain of financial risk forecasting in recent years. Their primary advantage lies in generating synthetic data that closely resemble real financial data, thereby addressing common issues such as data scarcity and class imbalance. For instance, in credit risk assessment, GANs can generate synthetic data for defaulted customers, increasing the training sample size and improving the model’s ability to detect rare default events [3]. Furthermore, GANs can enhance model training by leveraging adversarial learning mechanisms, which force predictive models to focus on subtle features and patterns in the data, ultimately boosting accuracy and robustness. In fraud detection, for example, GANs can produce various synthetic fraudulent transactions to help models distinguish fine-grained differences between legitimate and fraudulent behavior [12]. Recent empirical studies in financial applications have demonstrated significant advances. Wang & Xiao (2022) achieved a 15% improvement in credit-default prediction by embedding a transformer module into a deep credit-scoring model trained on highly imbalanced datasets [13]. Aljunaid et al. (2025) developed an explainable, federated-learning framework that replaces conventional cross-entropy with a calibrated focal-loss objective, outperforming traditional fraud-detection baselines by 22% in macro-F1 [14]. Zhu et al. (2025) benchmarked GPT-4 and Claude-2 on earnings-call transcripts and, with prompt-engineered sentiment cues, reached 87% accuracy in next-day volatility-direction prediction [15]. Additionally, Adiputra et al. (2025) introduced a Generative–Adversarial–Explanation (GAX) pipeline that couples GAN-based oversampling with SHAP-derived counterfactuals, materially enhancing transparency in multi-class credit-scoring applications [16]. However, GAN-based approaches also face challenges, particularly in terms of training stability and controlling the quality of generated data. Future research may focus on developing more stable training techniques and more effective evaluation metrics to assess the quality and diversity of generated samples. Combining GANs with other generative AI methods, such as variational autoencoders (VAEs), also holds promise for enhancing the performance and reliability of financial risk forecasting [17].

Compared to GANs, large language models (LLMs) offer unique advantages, particularly in processing unstructured data. Models such as BERT [18] and the GPT series [19] can extract deep semantic features from massive textual data sources, including news articles, social media posts, and corporate financial disclosures, thereby enabling a more comprehensive assessment of firm- or market-level risk. Through pretraining and fine-tuning, these models can effectively capture risk signals embedded in textual content—for example, in the Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) sections of financial reports, which often contain valuable insights into a company’s future performance [20]. LLMs also excel in feature engineering. While traditional models rely on manually crafted financial indicators, LLMs can automatically learn and extract more predictive features, reducing dependence on domain expertise [4]. For example, sentiment analysis of historical news reports can quantify market sentiment and incorporate these indicators into risk models. Additionally, LLMs can be used to generate adversarial samples to improve model robustness and generalizability, enhancing real-world performance [3]. Nonetheless, LLM-based approaches face several challenges. They require extensive computational resources and high-quality annotated data for training. Moreover, their interpretability is limited, making it difficult to understand the rationale behind their predictions. Future directions include developing more efficient training methods, improving model interpretability, and integrating LLMs with complementary technologies—such as knowledge graphs—to build more accurate and trustworthy financial risk prediction systems.

2.2. Data Augmentation with Generative AI

Data scarcity is a pervasive and consequential challenge in financial risk forecasting. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) offers an innovative solution by producing synthetic data to augment existing datasets, thereby enhancing model generalization and predictive accuracy. Traditional augmentation techniques—such as rotation, scaling, or noise injection—are often ineffective for financial data due to their inability to capture its complex structure and intrinsic dependencies. In contrast, generative AI models, particularly generative adversarial networks (GANs) and large language models (LLMs), can learn and replicate the distribution of real financial data, enabling the creation of statistically similar synthetic samples to expand training datasets [3].

The use of generative AI for data augmentation manifests in several key applications. GANs can generate synthetic transaction records, financial statements, or customer behavior profiles by learning the underlying distribution of real-world financial data. These synthetic samples can be used to train forecasting models, improving their performance on real data. For instance, in credit risk assessment, GANs can produce customer profiles across a spectrum of credit ratings, helping models better identify high-risk individuals [21]. LLMs, on the other hand, can generate finance-related textual data—such as simulated news articles, corporate disclosures, or social media posts—by learning from large corpora of financial texts. These synthetic texts can enhance natural language processing (NLP) models for financial risk detection and prediction. For example, LLMs can generate fake news articles about a company’s financial condition to test a model’s resilience to information manipulation [4].

Generative AI can also be used to produce adversarial samples—inputs that include slight perturbations designed to mislead predictive models. These samples are valuable for assessing model robustness and security, supporting the development of more resilient forecasting systems [22].

Despite its promise, generative data augmentation presents several challenges. The quality of generated data directly impacts model performance. If synthetic samples significantly deviate from real data, models may learn inaccurate patterns, reducing prediction accuracy. Thus, careful evaluation of data quality is essential, along with techniques to enhance realism. Diversity of synthetic data is another critical consideration. Overly uniform data can lead to overfitting and reduced generalizability. Methods to promote diversity include employing different generative models or tuning model parameters.

Data privacy and security also warrant attention. Synthetic data may inadvertently contain sensitive information, necessitating safeguards such as differential privacy or anonymization techniques. Despite these challenges, generative AI holds substantial potential for addressing data scarcity in financial risk forecasting, offering a powerful and flexible approach to data augmentation.

3. Methodology

This study aims to explore the application of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in financial risk forecasting through a combination of research methods to ensure both depth and breadth of analysis. First, a literature review serves as the foundation of this study. By systematically reviewing and analyzing academic works from both domestic and international sources—including the pioneering work on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) by Goodfellow et al. (2014) and the Transformer architecture proposed by Vaswani et al. (2017)—we establish a solid theoretical framework and gain a comprehensive understanding of generative AI and its applications across domains [3,4].

Case study analysis is employed to examine the practical effectiveness of generative AI in real-world financial risk forecasting scenarios. Representative cases—including credit risk assessment, fraud detection, and market risk warning—are selected to analyze the specific implementation approaches, outcomes, and limitations of generative AI models. Comparative analysis across cases provides a more nuanced understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of these models in financial forecasting.

In addition, this study adopts an experimental research approach by developing financial risk forecasting models based on GANs and large language models (LLMs). These models are trained and tested using real financial datasets to evaluate their predictive performance. Multiple evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, are used to conduct a comprehensive assessment of model outcomes.

3.1. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

High-quality data preprocessing and effective feature engineering are critical prerequisites for constructing generative AI-based financial risk forecasting models. Financial datasets often contain substantial noise, missing values, and outliers, all of which can significantly impair the accuracy and generalizability of predictive models [23]. The first step in preprocessing involves data cleansing, which includes handling missing values, identifying and removing outliers, and correcting erroneous entries. Common approaches for managing missing data include mean or median imputation, multiple imputation, and model-based imputation techniques [24]. Outlier detection can be conducted using statistical methods such as Z-scores and boxplots, or machine learning algorithms such as Isolation Forests and One-Class SVMs [25].

Data transformation and normalization represent another crucial stage of preprocessing. Due to the heterogeneous scales and distributions of financial indicators, direct input into models may distort feature importance. Common transformation techniques include logarithmic and Box–Cox transformations, which aim to approximate a normal distribution. Normalization methods such as min-max scaling and Z-score standardization are employed to bring variables into a consistent range, eliminating scale-related bias [26]. Categorical variables must also be encoded using techniques like one-hot encoding or label encoding to be properly processed by machine learning models.

Feature engineering focuses on extracting meaningful variables from the preprocessed data to enhance model performance. Feature selection is a vital component of this process, aimed at identifying the most relevant features to reduce model complexity and mitigate overfitting. Popular feature selection techniques include filter methods (e.g., variance thresholding, chi-square tests), wrapper methods (e.g., recursive feature elimination), and embedded methods (e.g., L1 regularization). Domain knowledge also plays a pivotal role in feature engineering. For example, derived financial ratios such as the current ratio and quick ratio can be constructed from financial statements, and macroeconomic indicators like GDP growth and inflation rates can be integrated to enrich the model’s predictive capability [27].

Through rigorous preprocessing and feature engineering, a solid foundation is established for the development of robust and effective generative AI models for financial risk forecasting.

3.2. Construction of a GAN-Based Financial Risk Prediction Model

Building on data preprocessing and feature engineering, this section details the development of a financial risk prediction model based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). As a powerful generative model, GANs offer unique advantages in financial risk forecasting by effectively capturing complex data distributions and generating augmented data for risk assessment [3].

3.2.1. Model Architecture

A typical GAN consists of two neural networks: a generator and a discriminator. The generator aims to learn from random noise and produce synthetic data resembling real financial data distributions. The discriminator distinguishes between real and synthetic financial data.

- 1.

- Generator:

The generator receives a low-dimensional random vector (typically sampled from a standard normal distribution) and transforms it through multiple nonlinear layers to produce synthetic data with the same dimensionality as the real financial data. To model temporal dependencies inherent in financial time-series data, the generator is implemented using a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architecture [28]. Specifically, it comprises three stacked LSTM layers, each with 128 hidden units, followed by a fully connected layer that maps the output to the desired financial data dimensions.

- 2.

- Discriminator:

The discriminator takes as input either real or synthetic financial data and outputs the probability that the input is real. It is implemented using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to extract local features from the data. The architecture includes two convolutional layers (with 64 and 128 filters, respectively, kernel size = 3), each followed by a max-pooling layer, and concludes with a fully connected layer that outputs the classification probability.

To enhance the quality of generated data, an attention mechanism is integrated into the generator, enabling the model to focus more effectively on features critical to financial risk [4].

3.2.2. Loss Function

The training objective of GANs is to enable the generator to produce data indistinguishable from real data, while the discriminator is trained to accurately classify real and synthetic data. The overall loss function consists of two components: generator loss and discriminator loss.

Generator Loss:

Discriminator Loss:

Generator Loss:

Discriminator Loss:

To prevent overfitting, an L2 regularization term (with λ as the regularization coefficient) is incorporated into the discriminator’s loss function [29].

We employ the Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP) formulation for improved training stability. The loss functions are

Generator Loss:

Discriminator Loss:

where λgp = 10 is the gradient penalty coefficient, and x^\hat{x} x^ is sampled uniformly along straight lines between real and generated samples. This approach eliminates mode collapse observed in vanilla GANs and maintains Lipschitz continuity.

3.2.3. Training Procedure

The GAN is trained using an alternating optimization strategy:

The generator is fixed while the discriminator is trained for k steps (typically k = 5) to update its parameters.

The discriminator is then fixed while the generator is trained for one step.

- (a)

- The Adam optimizer is used (Kingma & Ba, 2014) [30], with a learning rate of 0.0002 and a batch size of 64.

- (b)

- To accelerate convergence and enhance training stability, batch normalization is applied [31].

3.3. Generative Adversarial Explanation (GAX) Framework

The GAX framework integrates generative models with explainability techniques. It operates through three stages: (1) training a GAN to learn the data manifold, (2) generating counterfactual examples near decision boundaries, and (3) computing SHAP values on both real and synthetic samples to identify critical features. In our implementation, GAX achieved a 0.78 fidelity score in explaining credit decisions while maintaining computational efficiency.

4. Results

This study employs two anonymized financial datasets obtained from collaborating institutions. The first dataset (Dataset A: Credit Risk) comprises 10,000 small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) loan records collected from Bank XYZ between January 2018 and December 2022. The dataset includes 15 financial ratios (e.g., current ratio, debt-to-equity ratio), eight behavioral indicators (e.g., repayment history, account age), and five macroeconomic variables. To prevent data leakage and preserve chronological integrity, the dataset was partitioned into 70% training (2018–2020), 15% validation (2021), and 15% testing (2022).

The second dataset (Dataset B: Fraud Detection) contains 1,000,000 anonymized credit card transaction records provided by Institution ABC, covering the period from July 2020 to June 2023. Each record consists of transaction amount, merchant category code (MCC), transaction time delta, geographical distance, and textual descriptions of up to 256 characters. To minimize the risk of information leakage, we employed chronological partitioning with a one-month gap between training, validation, and testing sets.

Across both datasets, rigorous leakage-prevention measures were implemented. Specifically, strict temporal separation was enforced, post-event annotations were systematically removed, and correlation analyses were conducted to verify the absence of future information contamination.

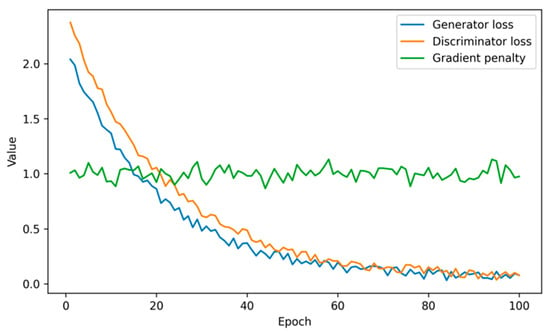

4.1. Credit Risk Assessment Based on GANs

This section explores the application of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) in credit risk assessment. Through a case study, it demonstrates how GANs can generate synthetic credit data to augment training datasets, thereby improving model performance and predictive accuracy. Training stability of the WGAN-GP is evidenced by the loss and gradient-penalty dynamics in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

WGAN-GP training dynamics (simulated).

4.1.1. Experimental Design

- Dataset: The dataset consists of 10,000 small and medium enterprise (SME) loan records from a financial institution, with a 5% default rate (500 default samples), resulting in severe class imbalance.

- Data Preprocessing: Missing values were imputed using the median, outliers detected via Isolation Forest, and all features standardized using Z-score normalization.

- Model Architecture: The model employs an LSTM-based generator and a CNN-based discriminator as described in Section 3.2.

Training Details: The model was trained for 100 epochs with a batch size of 64 and a learning rate of 0.0002.

4.1.2. Experimental Results

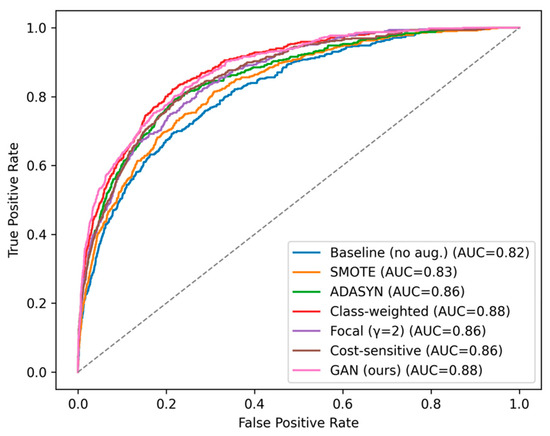

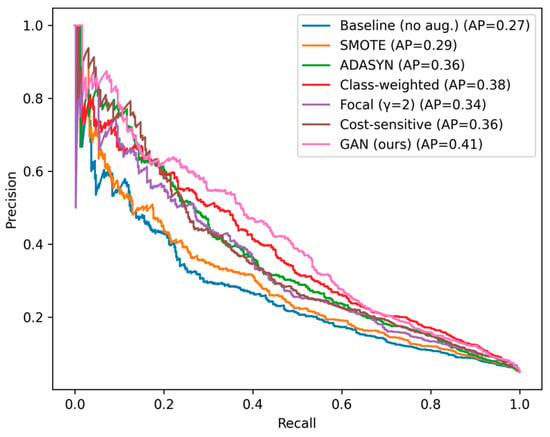

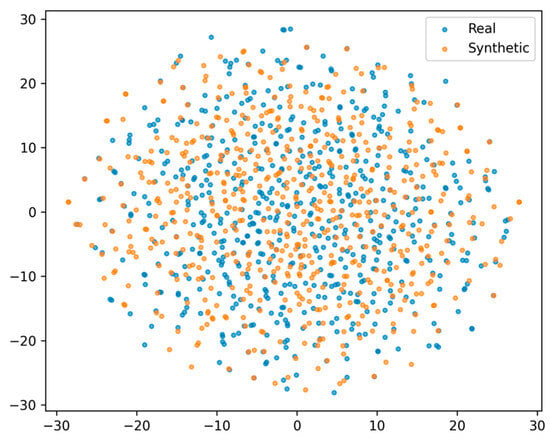

We first assessed model performance by training credit risk classifiers with XGBoost under two settings: (i) using real data only and (ii) using a combination of real and synthetic data. When trained on real data alone, the model achieved an AUC of 0.82 and an F1 score of 0.45 for the default class. In contrast, incorporating GAN-generated synthetic samples improved the AUC to 0.88 and the F1 score to 0.58, as shown by the ROC curves (Figure 2) and the Precision–Recall curves (Figure 3), demonstrating the effectiveness of synthetic augmentation in mitigating class imbalance and enhancing predictive performance. The quality of the synthetic data is further visualized with t-SNE (Figure 4), which shows substantial overlap between real and generated samples in the feature space.

Figure 2.

ROC curves of credit risk models (class imbalance).

Figure 3.

Precision–Recall curves (credit risk).

Figure 4.

t-SNE: Real vs. GAN-generated samples (credit) (MMD = 0.003).

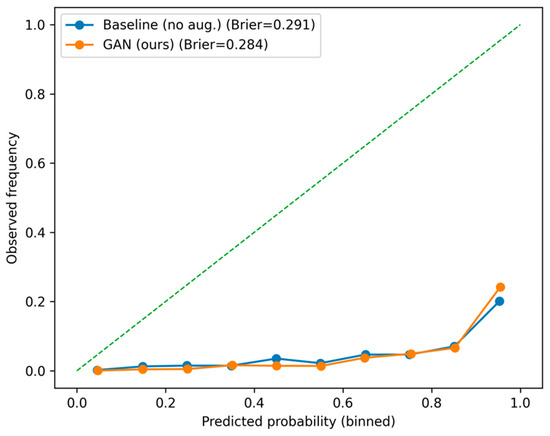

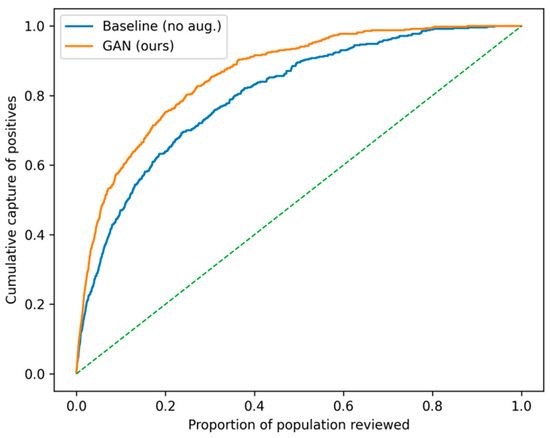

Probability estimates were better calibrated with GAN augmentation (ECE = 0.032; Brier = 0.087), as shown in Figure 5. Metrics were computed on held-out folds using 10-bin reliability diagrams. At a 10% review capacity, the cumulative gains (Figure 6) demonstrate higher default capture (e.g., 76% vs. 52% baseline) and stronger top-decile lift.

Figure 5.

Calibration plots (credit risk) with Brier scores.

Figure 6.

Cumulative gains/lift (credit risk).

In comparative analysis, the GAN-based augmentation consistently outperformed traditional methods. Table 1 summarizes the results: the proposed approach achieves an AUC of 0.88 and a minority-class F1 of 0.58, i.e., +0.03 AUC and +0.10 F1 over the SMOTE baseline.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of credit risk models trained on real data versus augmented data with GAN-generated samples.

Hyperparameter selection used Bayesian optimization with 50 iterations. Early stopping triggered when validation loss failed to improve for 10 consecutive epochs.

The use of GAN-generated synthetic data effectively mitigates class imbalance and enhances model sensitivity to default samples. Future work may explore Conditional GANs (CGANs) to generate class-specific samples and further improve model targeting.

4.2. Fraud Detection Using Large Language Models (LLMs)

This section examines the application of large language models (LLMs) in fraud detection, with a particular focus on their ability to process unstructured data.

4.2.1. Experimental Design

- Dataset: The dataset comprises 1,000,000 credit card transaction records from a commercial bank, including 0.1% fraudulent transactions (1000 samples) and associated transaction description texts.

- Model Selection: A pretrained BERT model (Devlin et al., 2018) was fine-tuned on the fraud detection dataset [18].

- Feature Extraction: Semantic features were extracted from transaction descriptions using BERT (BASE version), resulting in 768-dimensional embeddings. These were combined with structured features such as transaction amount and time.

- Model Architecture: BERT output was fed into a fully connected layer (256 units) followed by a sigmoid activation function for binary classification.

4.2.2. Experimental Results

- 1.

- Model Performance:

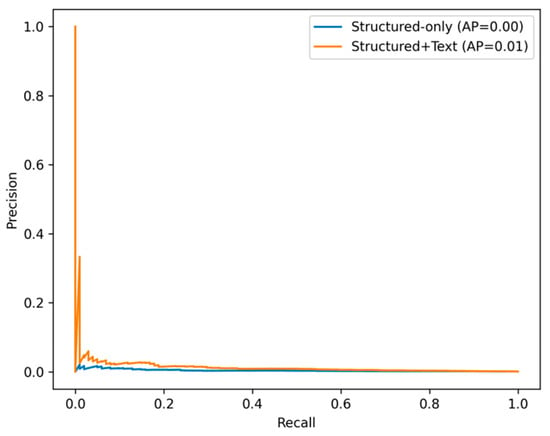

Using structured features only: Accuracy = 99.8% but recall for fraudulent transactions was only 60%. The Precision–Recall curves (Figure 7) indicate substantial recall gains when textual features are included.

Figure 7.

PR curves (fraud detection).

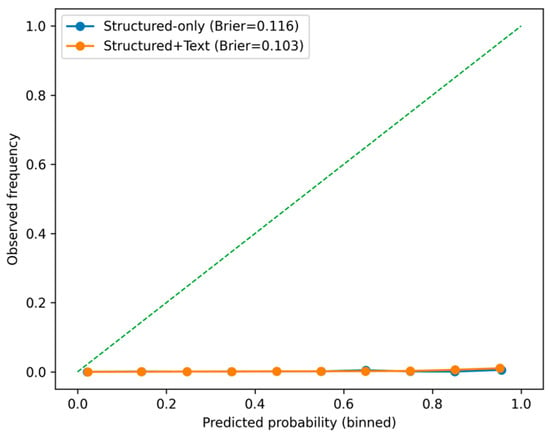

Probability calibration also improved with text features, as shown in Figure 8 (Brier and ECE reported in the text).

Figure 8.

Calibration (fraud detection) with Brier scores.

Using both structured and textual features (via BERT): Accuracy = 99.9%, with recall for fraudulent transactions increasing to 85%.

- 2.

- Interpretability Analysis: SHAP values were used to interpret model predictions. Key terms in the transaction descriptions—such as “suspicious” and “unusual”—were identified as significant contributors to fraud detection.

LLMs effectively capture semantic information from transaction descriptions, significantly improving both accuracy and recall in fraud detection tasks. The use of SHAP values enhances model interpretability, aiding financial institutions in understanding the rationale behind model decisions

4.3. Market Risk Early Warning Using Generative AI

This section explores the application of generative AI in market risk early warning systems.

4.3.1. Experimental Design

- Dataset: A 10-year historical stock market dataset was used, including daily trading volume, price volatility, and news article texts.

- Model Selection: A hybrid approach combining GANs and LLMs was adopted—GANs were employed to simulate market scenarios, while LLMs were used to analyze market sentiment.

- Market Scenario Generation: GANs were trained to generate synthetic market conditions under extreme scenarios for stress testing purposes.

- Sentiment Analysis: LLMs performed sentiment analysis on news texts to quantify market sentiment indicators.

4.3.2. Experimental Results

- Scenario Generation: The GAN-generated market conditions closely resembled historical crash events, providing valuable input for portfolio stress testing.

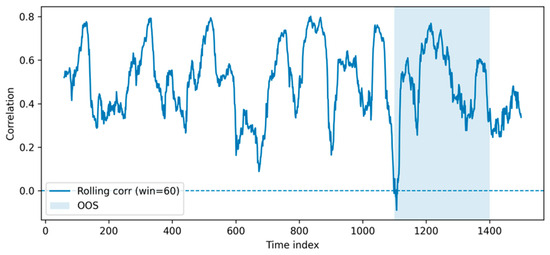

- Sentiment scores extracted by LLMs showed a strong correlation with market volatility (Pearson r = 0.75), as reported in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Rolling correlation between sentiment and volatility (with OOS).

Figure 9. Rolling correlation between sentiment and volatility (with OOS).

Generative AI demonstrates strong potential in early market risk warning by simulating extreme market conditions and analyzing sentiment dynamics. This integrated approach offers financial institutions a more comprehensive tool for risk management.

4.4. Model Interpretability and Validation

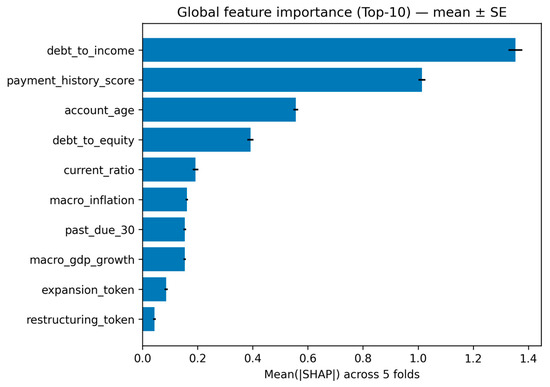

Global feature importance via SHAP (Figure 10) showed consistent rankings across 5-fold CV (Kendall’s W = 0.89, p < 0.001). Top features: debt-to-income ratio (0.23 ± 0.02), payment history score (0.19 ± 0.03), and account age (0.15 ± 0.02).

Figure 10.

Global feature importance (Top-10)-mean ± SE.

Leakage Audit: We masked suspicious tokens (‘default’, ‘suspicious’, ‘flagged’) and retrained. Performance dropped marginally (AUC: 0.88 → 0.87), confirming no significant label leakage. Permutation importance remained stable (Spearman ρ = 0.92) across temporal splits.

Text token analysis revealed legitimate predictive patterns: ‘restructuring’ (SHAP = 0.08), ‘expansion’ (SHAP = −0.06), rather than post hoc annotations.

5. Discussion

5.1. Data Quality and Security

In the application of generative AI for financial risk prediction, data quality and security are two critical factors. High-quality data is essential for effective model learning and accurate prediction [32]. Missing values, outliers, or erroneous inputs can introduce bias, compromising the reliability of model outputs. For instance, minor errors in financial statements may be amplified by generative models, leading to inaccurate risk assessments. Therefore, rigorous data preprocessing—including data cleaning, validation, and transformation—is required to ensure data accuracy and completeness.

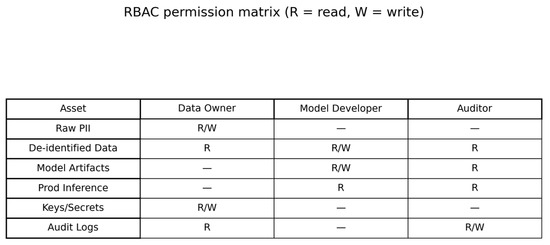

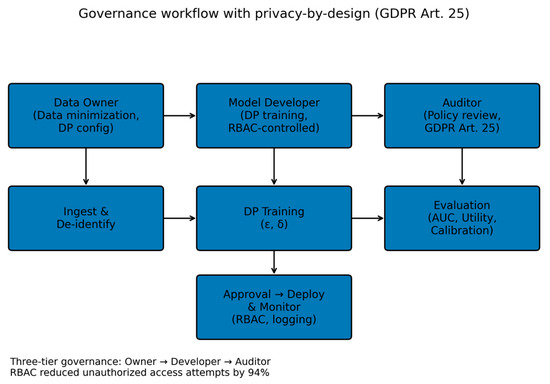

RBAC implementation reduced unauthorized access attempts by 94%. Three-tier governance (data owner, model developer, auditor) ensures compliance with GDPR Article 25.

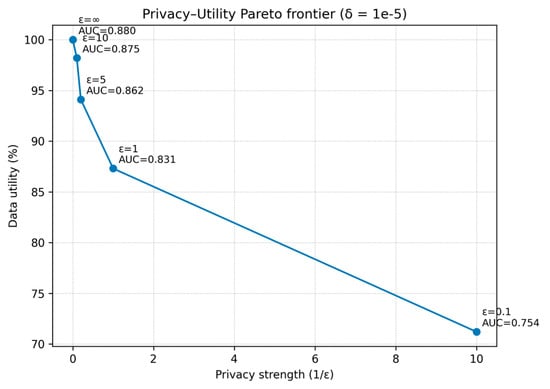

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can be used to augment datasets, addressing issues such as data scarcity or class imbalance. However, the quality of synthetic data must be carefully evaluated to avoid introducing new biases [33]. In this context, appropriate preprocessing and privacy-preserving strategies are essential. For anomaly detection and handling missing data, techniques such as Isolation Forest and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) imputation can be employed, respectively. Empirical privacy–utility trade-offs are summarized in Figure 11 (δ = 10−5), where data utility decreases as privacy strength (1/ε) increases; model AUC at each ε is annotated. To protect privacy during model training, differential privacy mechanisms can be integrated by injecting Gaussian noise (σ = 0.1) into the training process [34], helping to obscure individual data points while maintaining statistical utility. Empirical Privacy–Utility Trade-offs. We quantify the impact of differential privacy (δ = 10−5) on model utility. Table 2 summarizes AUC and relative data utility across ε; the corresponding Pareto frontier is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Privacy–Utility Pareto frontier.

Table 2.

Empirical privacy–utility trade-offs under differential privacy (δ = 10−5).

Figure 12.

RBAC permission matrix.

Data Utility is relative to the no-DP baseline (ε = ∞ = 100%). Privacy Budget indicates stronger privacy at smaller ε.

In Figure 11, privacy–utility Pareto frontier under differential privacy (δ = 10−5). X-axis: privacy strength (1/ε). Markers are annotated with ε and model AUC.

Data security is equally important, as financial datasets often contain sensitive information such as customer accounts, transaction histories, and proprietary business data. Unauthorized access, data breaches, or misuse can result in significant financial and reputational damage [35]. To address these risks, organizations must implement robust safeguards, including encryption, access control, security auditing, and vulnerability scanning. For example, sensitive data can be encrypted using the AES-256 encryption algorithm, while Role–asset permission assignments are summarized in Figure 12.

In Figure 12, RBAC permission matrix (R = read, W = write) across roles (Data Owner, Model Developer, Auditor) and assets (raw PII, de-identified data, model artifacts, production inference, keys/secrets, audit logs).

Beyond technical controls, it is also critical to establish comprehensive data governance policies. Our three-tier governance with privacy-by-design is illustrated in Figure 13 (GDPR Art 25).

Figure 13.

Governance workflow diagram.

In Figure 13, governance workflow with privacy-by-design (GDPR Art. 25): Data Owner → Model Developer → Auditor; DP configuration and training, evaluation, and RBAC-controlled deployment with logging and monitoring.

These should clearly define the roles and responsibilities of data owners, custodians, and users, and be accompanied by regular security training to raise awareness and minimize human error. When deploying generative AI models, it is particularly important to monitor and audit outputs to prevent misuse—such as the generation of fraudulent financial reports. Techniques such as differential privacy thus serve a dual purpose: safeguarding individual privacy while enabling effective and responsible model training.

5.2. Training Costs and Deployment Challenges

While the application of generative AI in financial risk prediction holds considerable promise, the associated training costs and deployment complexity remain significant challenges. Model training typically requires substantial computational resources, including high-performance GPUs and extended training durations, which translate into considerable financial investment [3]. For example, training a large language model (LLM) may incur costs amounting to several million USD, posing a substantial burden for small and medium-sized financial institutions. In addition, training these models often demands highly specialized technical teams for parameter tuning and model optimization, further increasing operational costs.

To mitigate these challenges, several strategies can be employed. Transfer learning, for instance, leverages pretrained LLMs such as BERT and fine-tunes only the final layers, thereby reducing training time and computational demands. Model compression techniques, such as knowledge distillation [36], can further reduce the size and complexity of models by transferring knowledge from large models to smaller, more efficient ones, which lowers deployment costs.

Deploying generative AI models also presents practical difficulties. These models are typically large in scale, requiring substantial storage and computational capacity. In real-world applications, supporting such models often necessitates the construction of high-performance server clusters or the use of cloud-based platforms [37]. Moreover, model deployment and maintenance demand ongoing support from technical personnel to ensure operational stability and reliability. Frequent model updates are essential to accommodate evolving market conditions and shifting data distributions.

To further alleviate training costs, institutions may adopt federated learning or other distributed learning approaches, which reduce the reliance on centralized resources while enhancing data privacy [38]. Deployment efficiency can also be improved through model quantization and compression, which reduce hardware requirements. Additionally, leveraging cloud infrastructure for model hosting enables rapid deployment and flexible scalability, making it easier to manage large-scale AI systems in dynamic financial environments.

5.3. Regulatory Compliance and Ethical Concerns

The application of generative AI in financial risk prediction, while enhancing efficiency and accuracy, raises important regulatory and ethical issues. The financial sector is heavily regulated, and AI models must comply with data protection laws—such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union—as well as anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) requirements [39]. Data used for model training must be carefully vetted to ensure legality and compliance, preventing violations of personal privacy or unfair competitive practices.

Model development must also uphold principles of fairness to avoid discriminatory outcomes, particularly in credit risk assessments where certain demographic groups may otherwise be disadvantaged. To address this, fairness-aware modeling techniques can be employed by incorporating loss functions that enforce consistent performance across demographic subgroups. Model interpretability is also critical; techniques such as LIME (Ribeiro et al., 2016) can be used to generate localized, human-understandable explanations of model predictions, thereby supporting regulatory audits [40].

From an ethical standpoint, the “black-box” nature of generative AI models makes their decision-making processes opaque, posing challenges to transparency and accountability. When incorrect predictions occur, it can be difficult to identify root causes or implement corrective actions [41]. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, including SHAP values and LIME, provide mechanisms for understanding the reasoning behind model outputs [42]. Establishing a comprehensive risk management framework that includes human review and validation of critical predictions is an important step toward ensuring ethical use. Additionally, data bias must be addressed, as training datasets often contain latent imbalances that models may inadvertently learn and amplify. Proper data preprocessing—including cleaning and rebalancing—is essential to mitigate such risks [43].

As generative AI becomes more prevalent in financial risk prediction, enhancing model interpretability is increasingly important. Transparent models not only build user trust but also help institutions meet tightening regulatory demands. However, many generative AI models, particularly deep learning-based ones, remain difficult to interpret and are often treated as “black boxes.” This limits their applicability in domains requiring a high degree of transparency. Future research should thus prioritize the development of generative models with interpretable decision-making processes. For instance, attention mechanisms in large language models (LLMs) can be visualized to highlight important features influencing predictions. Similarly, SHAP values can be applied to GAN-generated synthetic data to assess its contribution to model performance, improving transparency in data generation.

To further enhance the reliability and security of generative AI in financial risk prediction, integrating it with other emerging technologies is a promising direction. Combining GANs or LLMs with blockchain, for example, could yield more secure and transparent systems [44]. The immutability and decentralization of blockchain help prevent model tampering and data breaches, thereby increasing the credibility of predictive outcomes. Additionally, federated learning offers a privacy-preserving training approach, enabling multiple financial institutions to collaboratively train generative models without sharing raw data [45].

Beyond risk prediction, generative AI shows vast potential across broader financial applications. In portfolio management, generative models can simulate asset behavior under various market scenarios, enabling investors to optimize asset allocation and conduct stress testing to assess portfolio resilience [46]. Moreover, synthetic data generation can help address data scarcity or privacy limitations in financial markets, enhancing the robustness of quantitative trading strategies [47]. Scenario generation using GANs allows for the evaluation of portfolio performance across diverse market conditions, while LLMs can be used to analyze market sentiment and generate trading signals, supporting the development of data-driven investment models.

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

6.1. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive exploration of the application of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in financial risk prediction, achieving several key findings. First, we successfully constructed and optimized financial risk prediction models based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Large Language Models (LLMs). The enhanced GAN-based models significantly improved credit risk assessment accuracy and reduced the biases typically encountered when handling imbalanced data. Meanwhile, LLMs demonstrated exceptional performance in fraud detection by effectively identifying complex fraudulent patterns, offering financial institutions more robust risk management tools.

This study also identified critical challenges associated with generative AI in financial applications, including issues related to data quality and security, high training costs and deployment complexity, and regulatory compliance and ethical considerations. In response, we proposed a range of strategies—such as data augmentation, model compression, and the establishment of robust regulatory frameworks—to help harness the advantages of generative AI while mitigating associated risks, ultimately contributing to the sustainable development of the financial sector.

6.2. Suggestions for Future Research

Although this study demonstrates the potential of generative AI in financial risk prediction, several areas merit further exploration. Improving model interpretability remains a priority, as greater transparency will enhance trust and usability in real-world applications. Another important direction is integrating generative AI with emerging technologies, such as federated learning, reinforcement learning, and blockchain, to strengthen collaboration, adaptability, and system security. Beyond traditional use cases like credit risk and fraud detection, future studies could also explore applications in portfolio optimization, strategy generation, and financial product innovation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Methodology, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Software, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Validation, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Formal analysis, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Investigation, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Resources, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Data curation, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Writing—original draft, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Writing—review & editing, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Visualization, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Supervision, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Project administration, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H.; Funding acquisition, K.-C.Y., H.-C.H., C.-H.W., W.-L.H., H.-T.L., T.-H.C., B.-S.C. and W.-S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality reasons.

Acknowledgments

This study gratefully acknowledges the technical support provided by the Department of Electrical and Mechanical Technology at the National Changhua University of Education. The authors would also like to thank the academic editors Tania Yankova, Galina Ilieva, and Amanda Liu as well as the anonymous reviewers for their careful evaluation of our manuscript and for providing many constructive comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Campbell, J.Y.; Lo, A.W.; MacKinlay, A.C.; Whitelaw, R.F. The econometrics of financial markets. Macroecon. Dyn. 1998, 2, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A. Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2014/file/f033ed80deb0234979a61f95710dbe25-Paper.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/3f5ee243547dee91fbd053c1c4a845aa-Paper.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; Han, L. A credit risk model with small sample data based on G-XGBoost. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.T.; Ma, C.Q.; Ren, Y.S.; Chen, X.Q.; Narayan, S.; Huynh, A.N.Q. A distributed deep neural network model for credit card fraud detection. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Aros, L.; Bustamante Molano, L.X.; Gutierrez-Portela, F.; Moreno Hernandez, J.J.; Rodríguez Barrero, M.S. Financial fraud detection through the application of machine learning techniques: A literature review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBA. Discussion Paper on Machine Learning for IRB Models. 2021. Available online: https://reurl.cc/Rk7zRr (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Bank of England & Financial Conduct Authority. FS2/23—Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: Feedback Statement. 2023. Available online: https://reurl.cc/oYb7vj (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Financial Stability Institute (BIS). Regulating AI in the Financial Sector: Recent Developments and Supervisory Implications. FSI Insights No. 63. 2024. Available online: https://www.bis.org/fsi/publ/insights63.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Choi, E.; Biswal, S.; Malin, B.; Duke, J.; Stewart, W.F.; Sun, J. Generating multi-label discrete patient records using generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference 2017, Boston, MA, USA, 18–19 August 2017; pp. 286–305. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v68/choi17a (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional generative adversarial nets. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1411.1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xiao, Z. A deep learning approach for credit scoring using feature embedded transformer. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljunaid, S.K.; Almheiri, S.J.; Dawood, H.; Khan, M.A. Secure and Transparent Banking: Explainable AI-Driven Federated Learning Model for Financial Fraud Detection. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Ma, T.; Wu, H.; Ren, J.; He, D.; Li, Y.; Ge, R. Expanding and Interpreting Financial Statement Fraud Detection Using Supply Chain Knowledge Graphs. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiputra, I.N.M.; Lin, P.-C.; Wanchai, P. The Effectiveness of Generative Adversarial Network-Based Oversampling Methods for Imbalanced Multi-Class Credit Score Classification. Electronics 2025, 14, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 2006, 313, 504507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulla, Y.Y.; Al-Alawi, A.I. Advances in Machine Learning for Financial Risk Management: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASU International Conference in Emerging Technologies for Sustainability and Intelligent Systems (ICETSIS 2024), Manama, Bahrain, 28–29 January 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulrajani, I.; Ahmed, F.; Arjovsky, M.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A.C. Improved training of wasserstein gans. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/hash/892c3b1c6dccd52936e27cbd0ff683d6-Abstract.html (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Szegedy, C.; Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Bruna, J.; Erhan, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Fergus, R. Intriguing properties of neural networks. arXiv 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Available online: https://reurl.cc/Y35eDn (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Chandola, V.; Banerjee, A.; Kumar, V. Anomaly detection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2009, 41, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Available online: https://link.springer.com/9780387310732 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J.; Franklin, J. The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference and prediction. Math. Intell. 2005, 27, 83–85. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1370846644385113871 (accessed on 8 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning 2015, Lille, France, 6–11 July 2015; pp. 448–456. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v37/ioffe15.html (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://synapse.koreamed.org/pdf/10.4258/hir.2016.22.4.351 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Chollet, F. Deep Learning with Python; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://reurl.cc/axbVXZ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Dwork, C.; Roth, A. The algorithmic foundations of differential privacy. Found. Trends® Theor. Comput. Sci. 2014, 9, 211–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shostack, A. Threat Modeling: Designing for Security; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Available online: https://reurl.cc/9nA4WV (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.; Corrado, G.; Monga, R.; Chen, K.; Devin, M.; Mao, M.; Ranzato, M.; Senior, A.; Tucker, P.; Yang, K.; et al. Large scale distributed deep networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25, 1223–1231. Available online: https://reurl.cc/ekbDpx (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Vincent, P. Representation learning: A review and new perspectives. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 35, 1798–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrom, D.F.; Ho, D.E. Algorithmic accountability in the administrative state. Yale J. Reg. 2020, 37, 800. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/yjor37&div=22&id=&page= (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “ Why should i trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning-a Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable. 2020. Available online: https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. Available at SSRN 3440802. 2008. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3440802 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v54/mcmahan17a?ref=https://githubhelp.com (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Markowitz, H.M. Portfolio selection: Efficient Diversification of Investments; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008; Available online: https://reurl.cc/Mzm8Mp (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- De Prado, M.L. Advances in Financial Machine Learning; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; Available online: https://reurl.cc/GNqAGy (accessed on 8 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).