EU Digital Communication in Times of Hybrid Warfare: The Case of Russia and Ukraine on X

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

2.1. Digital Institutional Communication: A Shift from Traditional Models to the 3.0 Ecosystem

2.1.1. The Evolving Role of EU Communication Offices in the Digital Landscape

2.1.2. Social Media Strategies and Practices Among EU Institutions and Leaders

2.2. The State of Hybrid Warfare in the Disinformation Era

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Objectives

3.2. Hypotheses

- EU institutions tend to adopt a politically symbolic rhetoric when addressing international conflict, whereas their representatives on social media often favour a more procedural and administrative style of communication.

- Combating disinformation and enhancing citizens’ understanding of European matters are central pillars in the communication strategies pursued by EU institutions and their leaders during periods marked by hybrid threats.

- Institutional posts related to the Russia–Ukraine conflict generally exhibit a polished and professional audiovisual presentation.

- EU institutions and leaders regularly engage in digital exchanges with international organisations and prominent political figures, while their interactions with media professionals, scholars, and civil society actors are more selective and occasional.

- Posts published by European representatives on X attract higher levels of audience engagement compared to those shared through the official accounts of EU institutions.

3.3. Content Analysis

3.3.1. Sampling Selection Criteria

3.3.2. Procedure for the Content Analysis

- Ukraine

- Russia

- Ukraine’s

- Russia’s

- Ukrainian

- Russian

- Ukrainians

- Russians

- Kyiv

- Kremlin

- Kiev

- Putin

- Zelensky

- Zelenski

- Poland

- Hungary

- Mariupol

- Donetsk

- Luhansk

3.3.3. Research Variables

3.4. In-Depth Interviews

4. Results

4.1. European Commission (@EU_Commission)

4.1.1. Narrative Level

4.1.2. Interaction Level

4.1.3. Engagement Level

4.2. European Parliament (@Europarl_EN)

4.2.1. Narrative Level

4.2.2. Interaction Level

4.2.3. Engagement Level

4.3. European Council (@EUCouncil)

4.3.1. Narrative Level

4.3.2. Interaction Level

4.3.3. Engagement Level

4.4. Ursula von der Leyen (@vonderleyen)

4.4.1. Narrative Level

4.4.2. Interaction Level

4.4.3. Engagement Level

4.5. Roberta Metsola (@EP_President)

4.5.1. Narrative Level

4.5.2. Interaction Level

4.5.3. Engagement Level

4.6. Charles Michel (@eucopresident)

4.6.1. Narrative Level

4.6.2. Interaction Level

4.6.3. Engagement Level

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Study Limitations

6.2. Future Reseach Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Code Designed for the Content Analysis

- Aid sent to Ukraine

- Invasion, explosions or attacks on territories

- Population displacement

- Scarcity of goods and services

- Energy crisis

- Sanctions against Russia

- Ukraine’s joining the EU

- Conferences or meetings with international leaders

- Disinformation

- Other

- Solidarity with Ukraine

- Against violence

- Conflict-related

- Related to Ukraine’s joining the EU

- Migration/refugees/poverty-related

- Energy crisis-related

- Other #

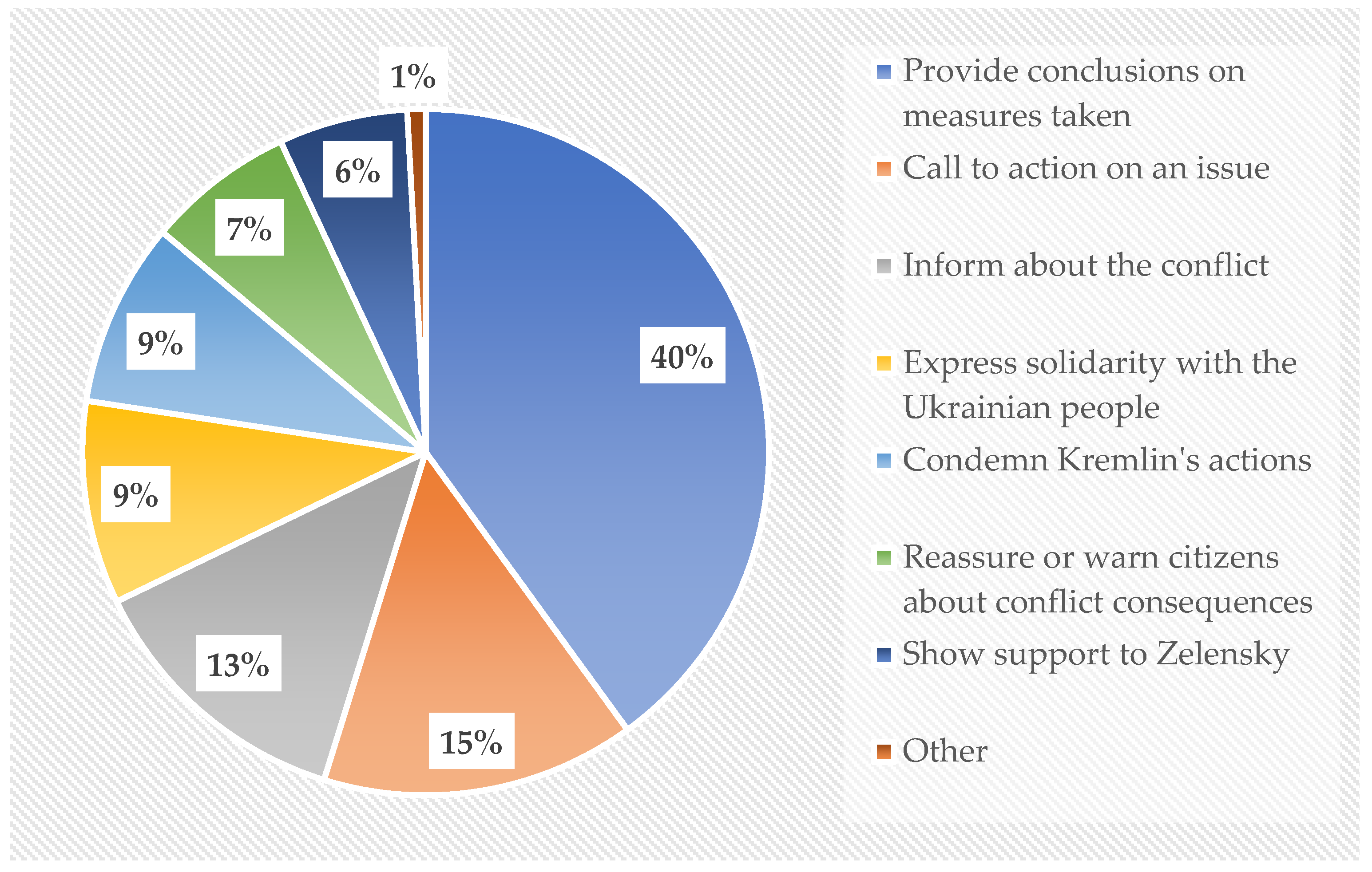

- Express solidarity with the Ukrainian people

- Condemn Kremlin’s actions

- Show support to Zelensky

- Inform about the conflict

- Call to action on an issue

- Reassure or warn citizens about conflict consequences

- Provide conclusions on measures taken

- Other

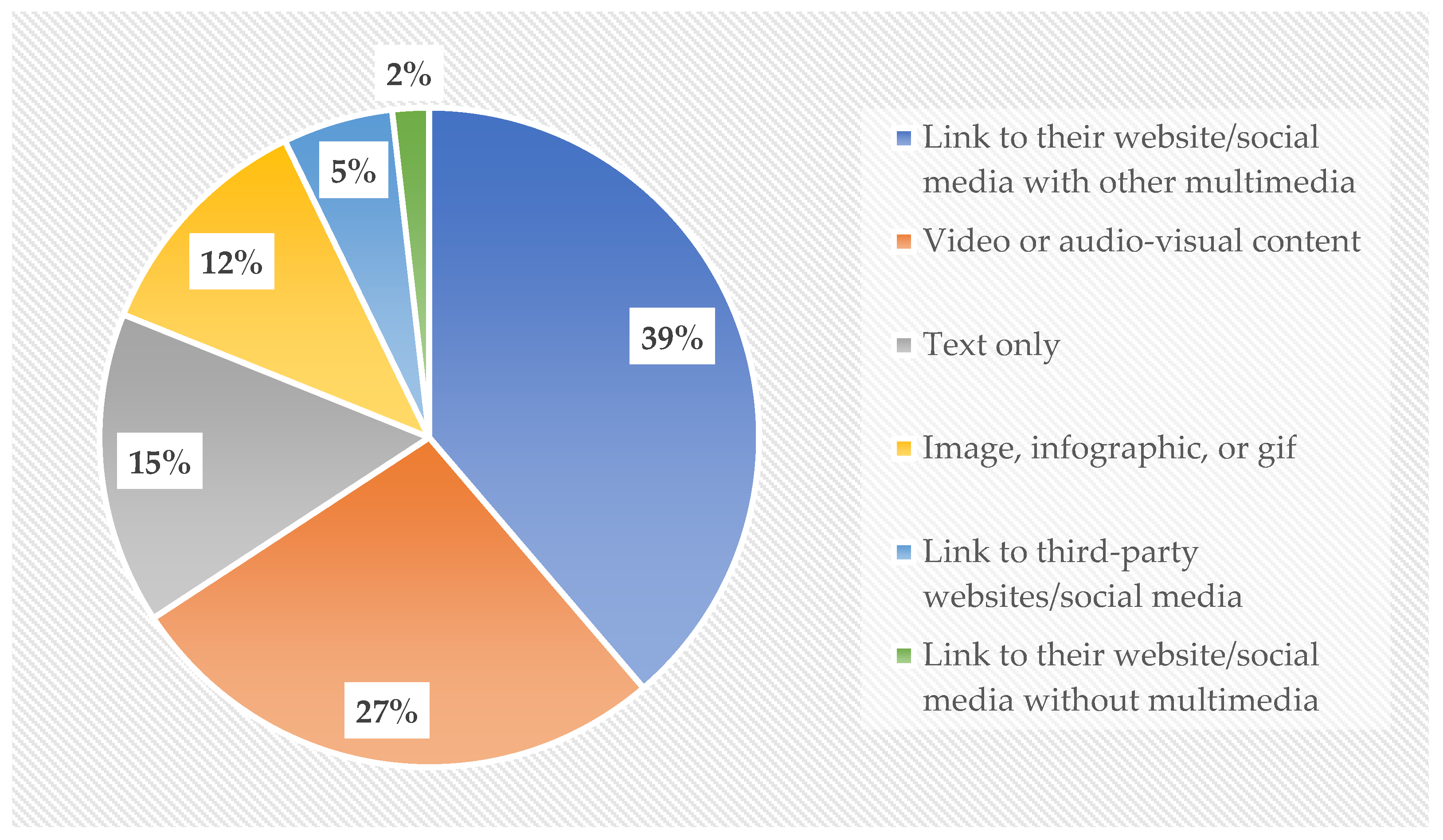

- Link to their website/social media without multimedia

- Link to their website/social media with other multimedia

- Link to media outlets

- Link to third-party websites/social media

- Image, infographic, or gif

- Video or audio-visual content

- Text only

- Other

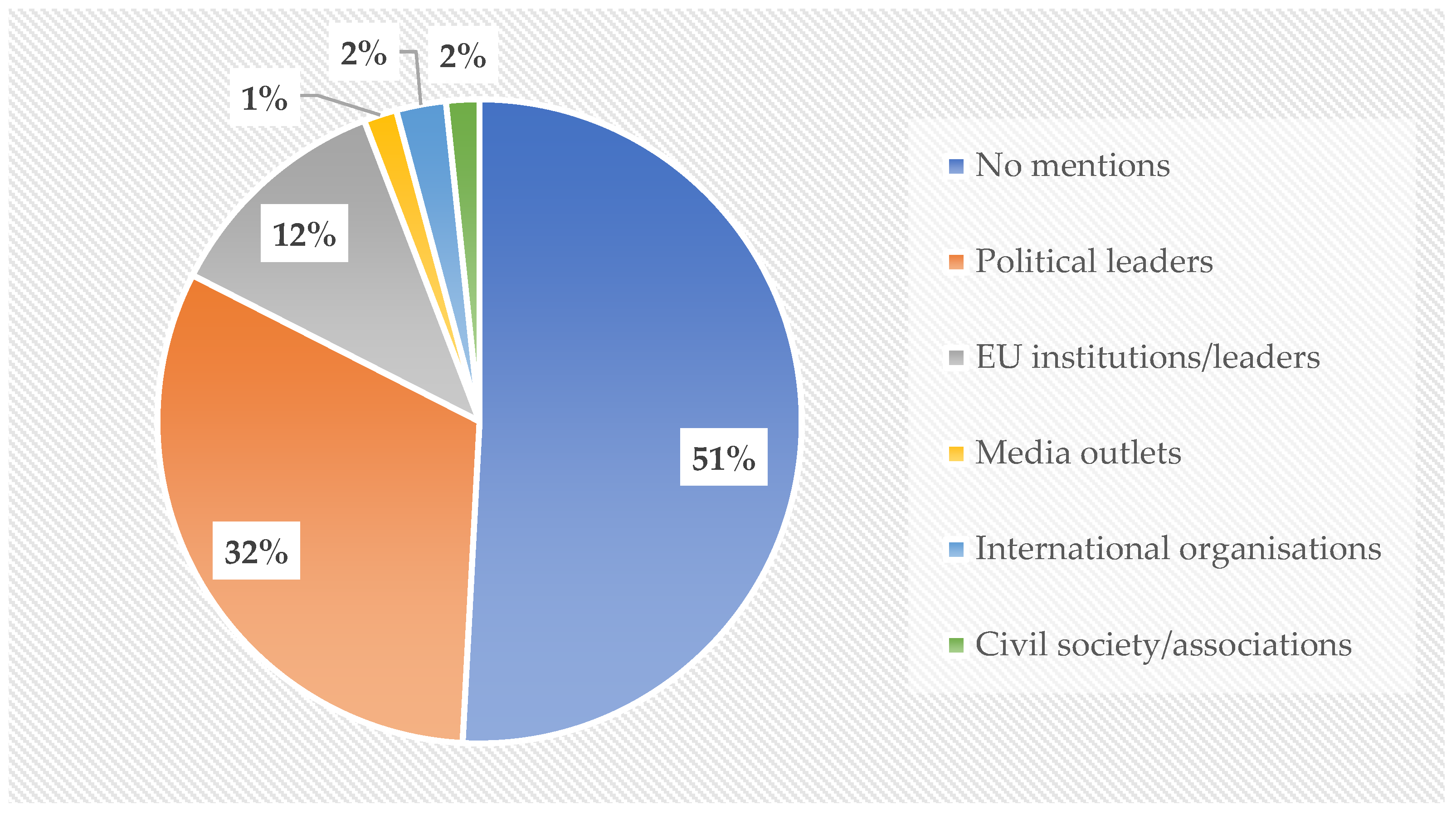

- No mentions

- EU institutions/leaders

- International organisations

- Political leaders

- Academics/researchers/scientists

- Civil society/associations

- Media outlets

- Other actors

- No quotation

- Tweet from EU institutions/leaders

- Tweet from EU Member States’ institutions

- Tweet from political leaders

- Other quotations

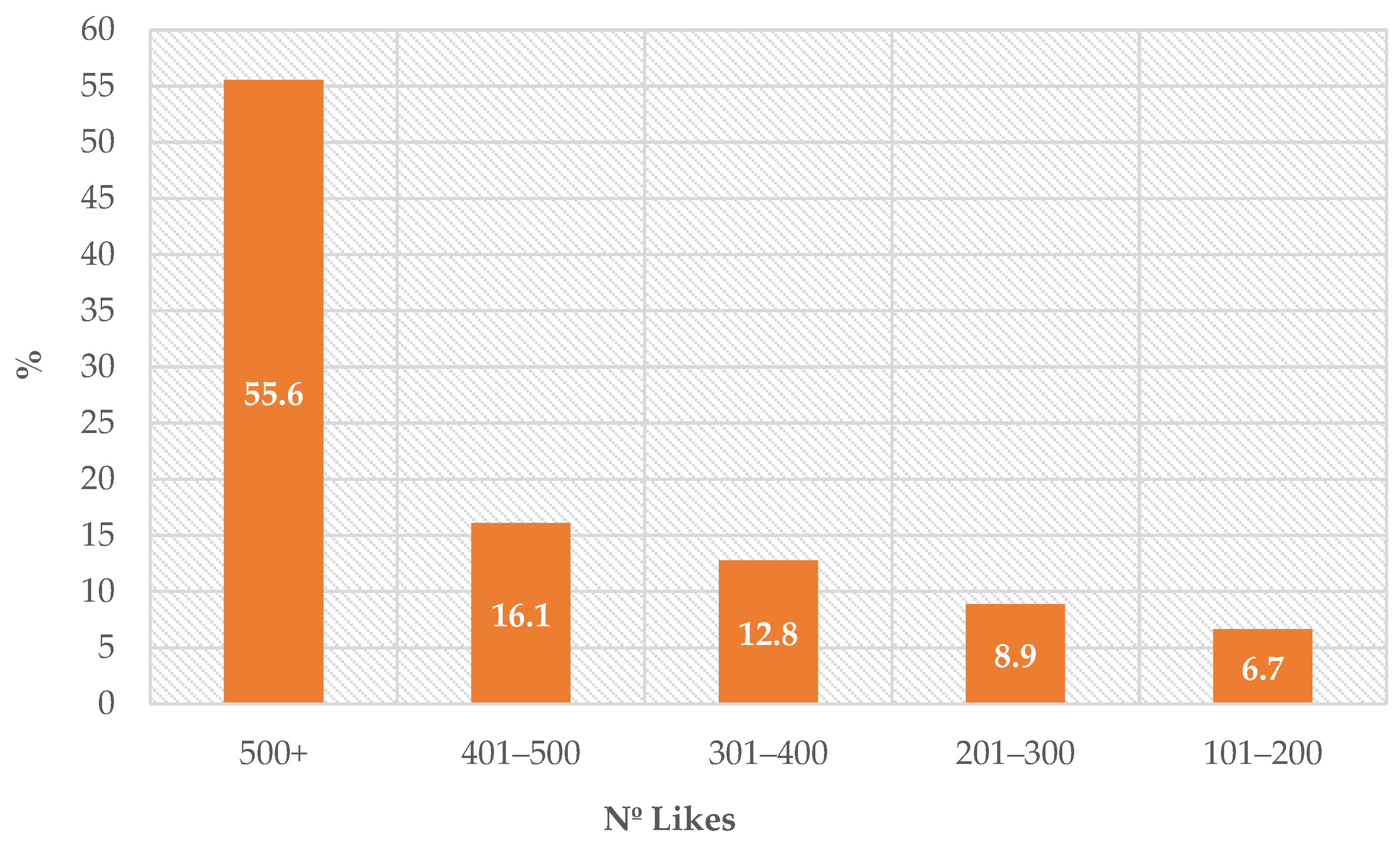

- 1–5

- 6–25

- 26–100

- 101–200

- 201–300

- 301–400

- 401–500

- +500

- 0

- 1–5

- 6–25

- 26–100

- 101–200

- 201–300

- 301–400

- 401–500

- +500

- 0

- 1–5

- 6–25

- 26–100

- 101–200

- 201–300

- 301–400

- 401–500

- +500

- 0

Appendix B. Classification and Description of Interviewees’ Profiles for the Research

| Representative | Profile | Position and Institution | Date | ID Code |

| Academics and experts | Political communication, public sphere, and disinformation in the EU | Professor at the Université Libre de Bruxelles and member of various Jean Monnet European Chairs | 3 May 2023 | CON-1 |

| European institutions | EU communication and digital policies | Spokesperson of European Parliament Office in Spain, Public Relations and Institutional Affairs at DG COMM | 1 June 2023 | CON-2 |

| European institutions | Information and communication on EU policies | Assistant in political communication at DG COMM in the European Commission | 31 May 2023 | CON-3 |

| European institutions | Information and communication on EU policies | Member of Press team at DG COMM in the European Council | 25 March 2023 | CON-4 |

| Media | International communication and European politics | European politics analyst and international correspondent at Spanish newspapers | 3 May 2023 | CON-5 |

| Social media outreach | EU information | Public Affairs consultant Brussels and content creator on European Affairs on social media | 4 May 2023 | CON-6 |

| European institutions | Information and communication on EU policies | Communication representative at the European Parliament | 9 June 2023 | CON-7 |

References

- Gleason, B. Thinking in hashtags: Exploring teenagers’ new literacies practices on X. Learn. Media Technol. 2018, 43, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canel, M.J.; Sanders, K. Government communication: An emerging field in political communication research. Sage Handb. Political Commun. 2012, 2, 85–96. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/y32huxav (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Rodríguez-Guillén, D. La Comunicación en los Gabinetes de Comunicación en la UE en el Siglo XXI: El uso de las TICs. Máster’s Thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2013. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/5n9yzczj (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Jiménez-Alcarria, F.; Tuñón-Navarro, J. EU digital communication strategy during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign: Framing, contents and attributed roles at stake. Commun. Soc. 2023, 36, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freelon, D.; Karpf, D. Of big birds and bayonets: Hybrid X interactivity in the 2012 presidential debates. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18, 390–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, J.; Carral, U. X como solución a la comunicación europea. Análisis comparado en Alemania, Reino Unido y España. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2019, 74, 1219–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherpereel, J.; Wohlgemuth, J.; Schmelzinger, M. The adoption and use of X as a re-presentational tool among members of the European Parliament. Eur. Politics Soc. 2016, 18, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänska, M.; Bauchowitz, S. Can social media facilitate a European public sphere? Transnational communication and the Europeanization of X during the Eurozone crisis. Soc. Media Soc. 2019, 5, 2056305119854686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gordillo, M.; Ramos-Serrano, M.; Rivas-de-Roca, R. Beyond Erasmus. Communication of European Universities alliances on social media. Prof. Inf. 2023, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, Z.; Popa, S.A.; Schmitt, H.; Barberá, P.; Theocharis, Y. Elite-public interaction on X: EU issue expansion in the campaign. Eur. J. Political Res. 2021, 60, 376–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, E.K.; Hammargård, K. The rhetoric of the President of the European Commission: Charismatic leader or neutral mediator? J. Eur. Public Policy 2016, 23, 550–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom-Piella, G. ¿El auge de los conflictos híbridos? Pre-Bie3 2014, 5, 43. Available online: https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_opinion/2014/DIEEEO120-2014_GuerrasHibridas_Guillem_Colom.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- European Commission Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council. Joint Framework on Countering Hybrid Threats: A European Union Response JOIN/2016/018 Final. 2016. Available online: https://bit.ly/3pi30b4 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Lesaca, J. La disrupción digital en el contexto de las guerras híbridas. Cuad. Estrateg. 2018, 197, 159–196. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.S.; Moncayo, O.E.; Conroy, K.M.; Jordan, D.; Erickson, T.B. The landscape of disinformation on health crisis communication during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ukraine: Hybrid warfare tactics, fake media news and review of evidence. J. Sci. Commun. 2020, 19, AO2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos, R.; Smith, H. Digital communication and hybrid threats. Rev. ICONO 14 Rev. Científica Comun. Tecnol. Emerg. 2021, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Serrano, S. From bullets to fake news: Disinformation as a weapon of mass distraction. What solutions does International Law provide? Span. Yearb. Int. Law 2020, 24, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Comunicación y Poder; Editorial UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Herráez, P. Comprender la guerra híbrida…¿ el retorno a los clásicos? Boletín IEEE 2016, 2, 304–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J. How Democracies Can Overcome the Challenges of Hybrid Warfare and Disinformation. CIDOB. 2022. Available online: https://www.cidob.org/en/articulos/cidob_report/n_8/how_democracies_can_overcome_the_challenges_of_hybrid_warfare_and_disinformation (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Bennett, W.L.; Kneuer, M. Communication and democratic erosion: The rise of illiberal public spheres. Eur. J. Commun. 2023, 39, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W.L.; Segerberg, A.; Knüpfer, C.B. The democratic interface: Technology, political organization, and diverging patterns of electoral representation. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 21, 1655–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, J. Desinformación y fake news en la Europa de los populismos en tiempos de pandemia. In Manual de Periodismo y Verificación de Noticias en la era de las Fake News; Elías, C., Teira, D., Eds.; Ediciones UNED: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 249–284. [Google Scholar]

- Redondo, M. La Doctrina del Post. Posverdad, Noticias Falsas… Nuevo Lenguaje Para Desinformación Clásica. ACOP. 2017. Available online: https://compolitica.com/la-doctrina-del-post-posverdad-noticias-falsas-nuevo-lenguaje-para-desinformacion-clasica/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Rodríguez-Fernández, L. Desinformación y comunicación organizacional: Estudio sobre el impacto de las fake news. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2019, 1714–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, L.C.; Chan Olmsted, S.; Fantapié Altobelli, C. Understanding Video Engagement on Global Service Networks—The Case of X Users on Mobile Platforms. In Dienstleistungen 4.0; Bruhn, M., Hadwich, K., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien: Rapperswil-Jona, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 391–409. [Google Scholar]

- Giglietto, F.; Selva, D. Second screen and participation: A content analysis on a full season dataset of tweets. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, D.; Renedo-Farpón, C.; Díez-Garrido, M. Podemos in the Regional Elections 2015: Online Campaign Strategies in Castille and León. Rev. Investig. Políticas Sociológicas 2017, 16, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-García, S. Las Redes Sociales Como Herramienta de Comunicación Política. Usos Políticos y Ciudadanos de X e Instagram. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Jaume I, Castelló, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, J.; López, S. Marcos comunicativos en la estrategia online de los partidos políticos europeos durante la crisis del coronavirus: Una mirada poliédrica a la extrema derecha. Prof. Inf. 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Sáez, J. Comunicación Política y Populismos. Análisis de la Estrategia Digital en Twitter de Podemos Durante las Campañas Europeas de 2014 y 2019. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Getafe, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tuñón-Navarro, J.; Bouzas-Blanco, A. Extrema derecha europea en Twitter. Análisis de la estrategia digital comunicativa de Vox y Lega durante las elecciones europeas de 2014 y 2019. Rev. Mediterránea Comun. Mediterr. J. Commun. 2023, 14, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Alcarria, F. Análisis, Impacto y Recepción de la Estrategia de Comunicación Digital en Twitter de la UE Durante la Campaña de Vacunación Contra la COVID-19. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Getafe, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Congosto, M.; Basanta-Val, P.; Sánchez-Fernández, L. T-Hoarder: A framework to process X data streams. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 83, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallón-Rosa, R. Nuevos formatos de verificación. El caso de Maldito Bulo en Twitter. Sphera Publica 2018, 1, 41–65. Available online: http://sphera.ucam.edu/index.php/sphera-01/article/view/341 (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Basurto, A.; Domínguez, M. ¿Quién Hablará en Europeo?: El Desafío de Construir una Unión Política sin una Lengua Común; Clave Intelectual: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Incertis, R.; Tuñón-Navarro, J. European Institutional Discourse Concerning the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the Social Network X. Journal. Media 2024, 5, 1646–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartín-Arce, R. La entrevista en el trabajo de campo. Rev. Antropol. Soc. 2000, 9, 105. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/457e6k72 (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Gaitán, J.A.; Piñuel, J.L. Técnicas de Investigación en Comunicación Social. Elaboración y Registro de Datos; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Domínguez, E.; Renedo-Farpón, C.; Calvo, D.; Díez-Garrido, M. Robot Strategies for Combating Disinformation in Election Campaigns: A Fact-checking Response from Parties and Organizations. In Politics of Disinformation: The Influence of Fake News on the Public Sphere; López-García, G., Palau-Sampio, D., Palomo, B., Campos-Domínguez, E., Masip, P., Eds.; Willey Blackwell: London, UK, 2021; pp. 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; Baptista-Lucio, P. Recolección y análisis de los datos cualitativos. In Metodología de la Investigación; Hernández-Sampieri, R., Fernández-Collado, C., Baptista-Lucio, P., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 418–425. [Google Scholar]

- Tuñón, J. La comunicación europea en contexto. In Comunicación Europea. ¿A Quién Doy Like Para Hablar con Europa? Tuñón, J., Bouza, L., Carral, U., Eds.; Editorial Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sádaba, C.; Salaverría, R. Combatir la desinformación con alfabetización mediática: Análisis de las tendencias en la UE. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2023, 81, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez del Vas, R.; Tuñón-Navarro, J. Disinformation on the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine War: Two sides of the same coin? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Incertis, R.; Sánchez del Vas, R.; Tuñón-Navarro, J. Análisis comparado de la desinformación difundida en Europa sobre la muerte de la reina Isabel II. Rev. Comun. 2024, 23, 507–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capati, A. The Personalisation of Politics in the Age of Social Media: What Risks for European Democracy? Ist. Aff. Internazionali 2019. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/bp6hddh9 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Deželan, T.; Maksuti, A.; Prodnik, J. Personalization of political communication in social media: The 2014 Slovenian national election campaign. In Social Media and Politics in Central and Eastern Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bouza, L.; Tuñón, J. Personalización, distribución, impacto y recepción en X del discurso de Macron ante el Parlamento Europeo el 17/04/18. Prof. Inf. 2018, 27, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Incertis, R.; Tuñón-Navarro, J. EU Digital Communication in Times of Hybrid Warfare: The Case of Russia and Ukraine on X. Information 2025, 16, 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100825

Ruiz-Incertis R, Tuñón-Navarro J. EU Digital Communication in Times of Hybrid Warfare: The Case of Russia and Ukraine on X. Information. 2025; 16(10):825. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100825

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Incertis, Raquel, and Jorge Tuñón-Navarro. 2025. "EU Digital Communication in Times of Hybrid Warfare: The Case of Russia and Ukraine on X" Information 16, no. 10: 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100825

APA StyleRuiz-Incertis, R., & Tuñón-Navarro, J. (2025). EU Digital Communication in Times of Hybrid Warfare: The Case of Russia and Ukraine on X. Information, 16(10), 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100825