Factors Affecting the Formation of False Health Information and the Role of Social Media Literacy in Reducing Its Effects †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on False Health Information on Social Media before COVID-19

2.2. Research on False Health Information on Social Media during COVID-19

3. Model Development

3.1. RQ1: What Are the Factors Making People Believe False Health Information?

3.2. RQ2: What Are the Factors That Make People Generate False Health Information?

3.3. RQ3: What Methods Can Reduce the Impact of False Health Information?

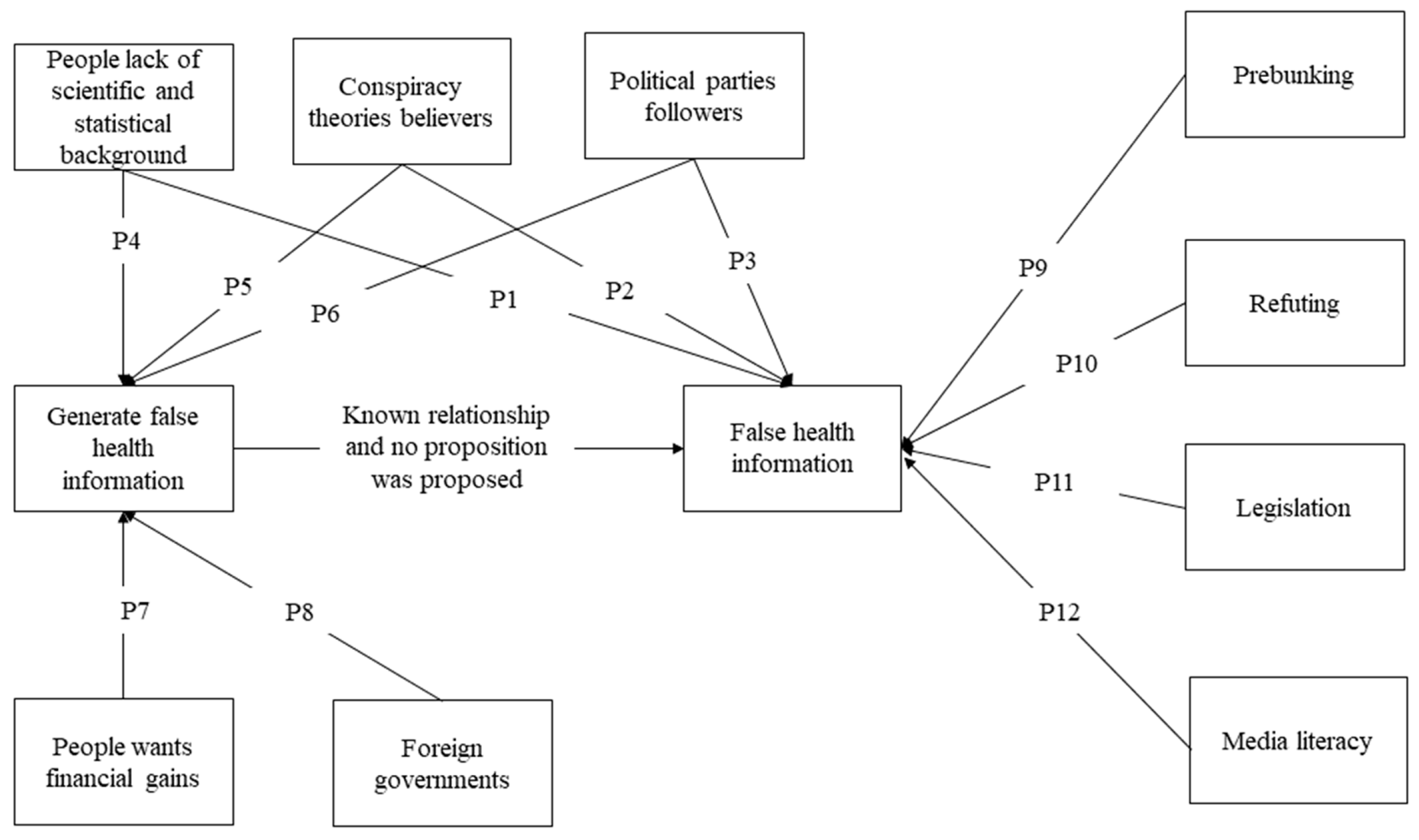

3.4. Proposed Theoretical Model

4. Discussion

4.1. General Discussion

4.2. Using Social Media Literacy to Reduce the Impact of False Health Information on Society

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, S.Y.; Ho, K.K.W.; Wakabayashi, K.; Kato, Y. Relationship between university students’ emotional expression on tweets and subjective well-being: Considering the effects of their self-presentation and online communication skills. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 594. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, Y.M.; de Moura, G.A.; Desidério, G.A.; de Oliveira, C.H.; Lourenço, F.D.; de Figueiredo Nicolete, L.D. The impact of fake news on social media and its influence on health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Public Health 2023, 31, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.W.; Chiu, D.K.W.; Au, C.H.; Dalisay, F.; So, S.; Yamamoto, M. Fake News, misinformation and privacy: How the COVID-19 pandemic changes our society and how blockchain and distributed ledger technologies reduce their effects? Distrib. Ledger Technol. Res. Pract. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.W.; Chan, J.Y.; Chiu, D.K.W. Fake news and misinformation during the pandemic: What we know, and what we don’t know. IT Prof. 2022, 24, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.W.; Chiu, D.K.W.; Sayama, K.L.C. When privacy, distrust, and misinformation cause worry about using COVID-19 contact-tracing apps. IEEE Internet Comput. 2023, 27, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 263, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, C.H.; Ho, K.K.W.; Chiu, D.K.W. Stopping healthcare misinformation: The effect of financial incentives and legislation. Health Policy 2021, 125, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapantai, E.; Christopoulou, A.; Berberidis, C.; Peristeras, V. A systematic literature review on disinformation: Toward a unified taxonomical framework. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 1301–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, L.; Vraga, E.K. See something, say something: Correction of global health misinformation on social media. Health Commun. 2017, 33, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, K.K.W.; Ye, S.Y.; Factors influencing the formation of false health information. In ICEB 2023 Proceedings, Chiayi, Taiwan, Paper 77. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/iceb2023/77 (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Bougioukas, K.I.; Bouras, E.C.; Avgerinos, K.I.; Dardavessis, T.; Haidich, A.-B. How to keep up to date with medical information using web-based resources: A systematized review and narrative synthesis. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2020, 37, 254–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, L.H.; Hoang, P.A.; Pham, H.C. Sharing health information across online platforms: A systematic review. Health Commun. 2023, 38, 1550–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waszak, P.M.; Kasprzycka-Waszak, W.; Kubanek, A. The spread of medical fake news in social media—The pilot quantitative study. Health Policy Technol. 2018, 7, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.E.; Wood, T. Medical conspiracy theories and health behavior in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; McKee, M.; Torbica, A.; Stuckler, D. Systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 240, 112552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrieri, V.; Madio, L.; Principe, F. Vaccine hesitancy and (fake) news: Quasi-experimental evidence from Italy. Health Econ. Lett. 2019, 28, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.; Middleton, J. Information wars: Tackling the threat from disinformation on vaccines. BMJ 2019, 365, 12144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kata, A. Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm—An overview of tactics and tropes used online by anti-vaccination movements. Vaccine 2012, 30, 3778–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeStefano, F. Vaccines and autism: Evidence does not support a causal association. Vaccines 2007, 82, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, M.; Attwell, K.; Casigliani, V.; Taylor, J.; Quattrone, F.; Lopalco, P. Legitimising a ‘zombie idea’: Childhood vaccines and autism—The complex tale of two judgments on vaccine injury in Italy. Int. J. Law Context 2021, 17, 548–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klofstad, C.A.; Uscinski, J.E.; Connolly, J.M.; West, J.P. What drives people to believe in Zika conspiracy theories? Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, D.; Simas, C.; Larso, H.J. An epidemic of uncertainty: Rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pummerer, L.; Böhm, R.; Lilleholt, L.; Winter, K.; Zettler, I.; Sassenberg, K. Conspiracy theories and their societal effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2022, 13, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.; Brooks, J.J.; Saucier, C.J.; Suresh, S. Evaluating the impact of attempts to correct health misinformation on social media: A meta-analysis. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipidza, W.; Akbaripourdibazar, E.; Gwanzura, T.; Gatto, N. Topic analysis of traditional and social media news coverage of the early COVID-19 pandemic and implications for public health communication. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 1881–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Naeem, S.; Bhatti, R.; Khan, A. An exploration of how fake news is taking over social media and putting public health at risk. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2021, 38, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melki, J.; Tamim, H.; Hadid, D.; Makki, M.; El Amine, J.; Hitti, E. Mitigating infodemics: The relationship between news exposure and trust and belief in COVID-19 fake news and social media spreading. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Tosevska, A.; Klager, E.; Eibensteiner, F.; Tsagkaris, C.; Parvanov, E.D.; Nawaz, F.A.; Völkl-Kernstock, S.; Schaden, E.; Kletecka-Pulker, M.; et al. Medical and health-related misinformation on social media: Bibliometric study of the scientific literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e28152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, E.K.; Fazel, S.S.; Peters, C.E. The Instagram infodemic: Conbranding on conspiracy theories, Coronavirus Disease 2019 and authority-questioning beliefs. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.-C.; Rao, A.; Zhong, Q.; Wojcieszak, M.; Lerman, K. #RoeOverturned: Twitter dataset on the abortion rights controversy. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 2023, 17, 997–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli, M.; De Francisci Morales, G.; Galeazzi, A.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Starnini, M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023301118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallone, R.P.; Ross, L.; Lepper, M.R. The hostile media phenomenon: Biased perception and perceptions of media bias in coverage of the Beirut massacre. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, M.D.; Sundar, S.S.; Le, T.; Lee, D. “Fake News” is not simply false information: A concept explication and taxonomy of online content. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021, 65, 180–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Qian, F.; Jiang, H.; Ruchansky, N.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y. Combating fake news: A survey on identification and mitigation techniques. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2019, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichocka, A. To counter conspiracy theories, boost well-being. Nature 2020, 587, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vraga, E.K.; Bode, L. Using expert sources to correct health misinformation in social media. Sci. Commun. 2017, 39, 621–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mheidly, N.; Fares, J. Leveraging media and health communication strategies to overcome the COVID-19 infodemic. J. Public Health Policy 2020, 41, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S. Fake news, disinformation, manipulation, and online tactics to undermine democracy. J. Cyber Policy 2018, 3, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanco-Levicán, K.; Salvo-Garrido, S. Understanding social media literacy: A systematic review of the concept and its competences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Shimoura, K.; Nagai-Tanima, M.; Aoyama, T. The relationship between information sources, health literacy, and COVID-19 knowledge in the COVID-19 infodemic: Cross-sectional online study in Japan. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, 238332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, K.; Shibuya, K.; Tokuda, Y. COVID-19 infodemic about nucleic acid amplification tests in Japan. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2022, 23, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoda, T.; Suksatit, B.; Tokuda, M.; Katsuyama, H. The relationship between sources of COVID-19 vaccine information and willingness to be vaccinated: An Internet-based cross-sectional study in Japan. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, T. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and media channel use in Japan: Could media campaigns be a possible solution? Lancet Reg. Health—West Pac. 2022, 18, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.W.; Nishikawa, M. Effects of health literacy in the fight against the COVID-19 infodemic: The case of Japan. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 1520–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Jang, S.M.; Mortensen, T.; Liu, J. Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021, 65, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesi, M. Understanding fake news during the Covid-19 health crisis from the perspective of information behaviour: The case of Spain. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2021, 53, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.Y.; Toshimori, A.; Horita, T. Causal relationships between media/social media use and Internet literacy among college students: Addressing the effects of social skills and gender differences. Educ. Technol. Res. 2017, 46, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.Y.; Ho, K.K.W. Would you feel happier if you have more protection behaviour? A panel survey of university students in Japan. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 38, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Details | References |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of scientific and statistical background | People who do not have sufficient knowledge to understand health information and misunderstand health information available on social media. | [4] |

| Believe in conspiracy theories and lack of trust in authorities | Some people believe in conspiracy theories and think governments and authorities hide the truth. This is also related to a low level of trust in authorities internationally. | [5,18] |

| Follow their political party line | Political party supporters believe (false) health information agreed upon by their political party line. | [4,6,30] |

| Factors | Details | References |

|---|---|---|

| Act in good faith | Some people generate false health information, intentionally and unintentionally, as they believe such alternative or incorrect views are correct. These people may misunderstand the correct information and misrepresent it. They can also be conspiracy theory believers or people supporting a political party that supports false health information, and they want to generate “evidence” to support the false information and conspiracy theories in which they believe. | [31,32] |

| Financial gain | Some people generate false health information to obtain financial gain, such as suggesting people purchase their medical products or services or driving online traffic to their sites to earn advertising revenue. | [33,34] |

| Foreign country influence | A prior study showed that some countries tried to use bots or Internet water armies to influence another country’s political environment, such as helping a political party that was more friendly to them to gain political advantage or more influence in the international arena. | [17] |

| Methods | Details | References |

|---|---|---|

| Prebunking | As it is more difficult to refute a conspiracy theory after it spreads, authorities should warn people about false health information they anticipate before it starts to spread. | [35] |

| Refuting by authorities | It is possible that corrective responses provided by authorities, with the help of communication specialists, could help to refute false health information. | [17,25,36,37] |

| Legislation against the spreading of false health information | While some countries plan to implement legislation to deter people from spreading false information, its effect is questionable. | [7,38] |

| Education on media literacy | It is essential to provide more education on media literacy and identifying false information in society to help citizens identify false health information and avoid spreading it. | [26,27] |

| Proposition | Representative Citations |

|---|---|

| People believe false health information (P1 to P3): | |

| [4] |

| [5,18] |

| [4,6,30] |

| People generate false health information in good faith (P4 to P6): | |

| [4,31,32] |

| [5,16,31,32] |

| [4,6,30,31,32] |

| People generate false health information to obtain financial gain (P7) | [33,34] |

| Foreign governments generate false health information to obtain political influence over other countries (P8) | [17] |

| Possible methods for reducing the impacts of false health information (P9 to P12): | |

| [35] |

| [17,25,36,37] |

| [7,38] |

| [26,27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ho, K.K.W.; Ye, S. Factors Affecting the Formation of False Health Information and the Role of Social Media Literacy in Reducing Its Effects. Information 2024, 15, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15020116

Ho KKW, Ye S. Factors Affecting the Formation of False Health Information and the Role of Social Media Literacy in Reducing Its Effects. Information. 2024; 15(2):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15020116

Chicago/Turabian StyleHo, Kevin K. W., and Shaoyu Ye. 2024. "Factors Affecting the Formation of False Health Information and the Role of Social Media Literacy in Reducing Its Effects" Information 15, no. 2: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15020116

APA StyleHo, K. K. W., & Ye, S. (2024). Factors Affecting the Formation of False Health Information and the Role of Social Media Literacy in Reducing Its Effects. Information, 15(2), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15020116