Abstract

Privacy policies are the main method for informing Internet users of how their data are collected and shared. This study aims to analyze the deficiencies of privacy policies in terms of readability, vague statements, and the use of pacifying phrases concerning privacy. This represents the undertaking of a step forward in the literature on this topic through a comprehensive analysis encompassing both time and website coverage. It characterizes trends across website categories, top-level domains, and popularity ranks. Furthermore, studying the development in the context of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) offers insights into the impact of regulations on policy comprehensibility. The findings reveal a concerning trend: privacy policies have grown longer and more ambiguous, making it challenging for users to comprehend them. Notably, there is an increased proportion of vague statements, while clear statements have seen a decrease. Despite this, the study highlights a steady rise in the inclusion of reassuring statements aimed at alleviating readers’ privacy concerns.

1. Introduction

Natural language privacy policies serve as the primary means of disclosing data practices to consumers, providing them with crucial information about what data are collected, analyzed, and how they will be kept private and secure. By reading these policies, users can enhance their awareness of data privacy and better manage the risks associated with extensive data collection. However, for privacy policies to be genuinely useful, they must be easily comprehensible to the majority of users. Lengthy and vague policies fail to effectively inform the average user, rendering them ineffective in ensuring data privacy awareness.

Research by Meier et al. [1] revealed that users presented with shorter privacy policies tend to spend more time understanding the text, indicating their willingness to engage with more concise information. Another study suggested that missing comprehension is a major burden for reading privacy policies. In the study, 18% of participants reported experiencing difficulty in understanding policies from popular websites, and over 50% did not actually understand the content [2]. Moreover, readability is essential for users’ trust, as other studies have emphasized [3].

Privacy policies are often excessive in length, requiring a substantial amount of time to read through. Estimates show that the average Internet user would spend around 400 h per year reading all encountered privacy terms [4]. This time investment may deter users from thoroughly reviewing policies, leading them to hurriedly click the “I agree” button without fully understanding the implications.

Addressing the significance of readability and privacy regulations, such as General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), mandate that privacy policies should be concise, easy to understand, and written in plain language. Additionally, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) emphasizes the need to present policies in a clear and straightforward manner, avoiding technical or legal jargon.

To enhance clarity and conciseness, the GDPR guidelines recommend the use of active voice instead of passive voice in writing [5]. The active voice directs the reader’s attention to the performer of the action, reducing ambiguity and making the text more straightforward.

Additionally, policies become less comprehensible due to ambiguity, which occurs when a statement lacks clarity and can be interpreted in multiple ways. The use of imprecise language in a privacy policy hinders the clear communication of the website’s actual data practices. For example, when websites summarize their data practices without specifying the exact conditions under which actions apply, vague policies emerge. Ambiguous policies allow websites to maintain flexibility in future changes to data practices without requiring policy updates [6].

The presence of language qualifiers like “may”, “might”, “some”, and “often” contributes to ambiguity, as noted by the European Commission’s GDPR guidelines [5]. Recent research suggests an increasing use of terms such as “may include” and “may collect” in privacy policies, which may result in policies becoming more ambiguous over time [7]. Vague language not only renders policies inaccurate but may also mislead readers, limiting their ability to interpret policy contents accurately. Consequently, ambiguity can erode users’ trust and raise privacy concerns, leading to reduced willingness to share personal information [8].

In addition to vague language, policies also contain expressions such as “we value your privacy” or “we take your privacy and security seriously”. Despite their intention to alleviate privacy concerns, these phrases do not convey crucial policy information. Positive language, at its best, redirects user focus away from privacy implications and, at its worst, can lead to misinformation.

This study examines the comprehensibility of English-language privacy policies between the years 2009 and 2019, utilizing natural language processing (NLP), machine learning and text-mining methods to analyze a large longitudinal corpus. The research focuses on the following indicators of clarity:

- Reading difficulty in terms of readability test and text statistics;

- Privacy policy ambiguity measured by the usage of vague language and statements;

- The use of positive phrasing concerning privacy.

The analysis encompassed several key factors: policy length, quantified through sentence count; passive voice index, indicating passive voice usage degree; and reading complexity, assessed via the new Dale–Chall readability formula, which considers semantic word difficulty and sentence length. Evaluating policy ambiguity involved identifying and counting vague terms from a defined taxonomy. Additionally, a pre-trained BERT model was utilized for multi-class sentence classification, predicting sentence vagueness levels within each policy. The study also explored the presence of positive phrasing related to privacy, examining the prevalence of phrases like “we value your privacy” or “we take your privacy and security seriously” across policies.

Some scholars have previously evaluated policy comprehensibility, focusing on shorter periods or single time points [4,7,9,10,11,12]. In contrast, this study advances the literature on consumer comprehension by conducting a large-scale analysis covering an extended period and a wide range of websites. It explores trends across website categories, top-level domains, and popularity ranks. Additionally, examining policy development in the context of the GDPR provides insights into the impact of regulations on policy writing practices. By shedding light on the lack of transparency in the privacy policy landscape, this research advocates for the design of more comprehensible and valuable privacy policy statements.

Wagner [4] examined length (words and sentences), passive voice, various readability formulas (Flesch Reading Ease (FRE), Coleman–Liau score (CL), and Simple Measure Of Gobbledygook (SMOG)). Srinath et al. [12] reported on the length of the privacy policy and the use of vague words in their private policy corpus. Compared to Srinath et al. [12], Libert et al. [13] and Wagner [4], the present work is based on the dataset of Amos et al. [7], which extends substantially over several years. Furthermore, herein the length and indeterminacy are analyzed in function of the GDPR, website category, popularity level, and domain.

The analysis of policy length reported by Amos et al. [7] in the form of a word-based analysis is complemented by a sentence-based analysis in this paper. Instead of the Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL) readability metric used by Amos et al. [7], Dale–Chall’s readability formula is used, which takes into account the semantic difficulty of words. In addition to analyzing the length based on the popularity of the website, our work considers additional aspects such as website category, GDPR and non-GDPR policies, and top-level domain. Although Amos et al. [7] found an increase in terms such as “may contain” and “may collect” in privacy policies in a general trend analysis and assumed that privacy policies become more ambiguous over time, this has not been systematically studied. This prompted us to investigate this specifically, based on the taxonomy of vague words by Reidenberg et al. [6] and a corpus of 4.5K sentences by Lebanoff and Liu [14] with a human-commented vagueness value to train a BERT classification model.

2. Regulatory Background

This section provides legal context to understand the foundation of privacy policies in the European Union and the United States. In the European Union, the Data Protection Directive (DPD) and its successor, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), have shaped the landscape of data privacy. In the United States, data privacy regulations have historically taken a sectoral approach, meaning that privacy laws and regulations have been developed for specific sectors or industries.

2.1. Data Protection in the European Union

The Data Protection Directive (DPD) of 24 October 1995 aimed to regulate the processing of personal data in the European Union, harmonizing data protection legislation across member states [15,16]. The law builds upon the concept of personal data, which is defined as “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (“data subject”); an identifiable person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, particularly with reference to an identification number or to one or more factors specific to their physical, physiological, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity” (Article 2). Such data include names, phone numbers, addresses and personal identification numbers.

The directive established supervisory authorities, data subject rights, and principles for data quality and processing. Special rules were introduced for sensitive data, prohibiting the processing of certain categories of information. Data controllers were required to provide transparent information to data subjects, often performed through privacy policies.

With the rise of the Internet and networked society, the need for enhanced data protection regulations became evident. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), adopted in 2016 and effective from 25 May 2018, replaced the Data Protection Directive. Unlike its predecessor, the GDPR was a regulation directly applicable in Member States without the need for national legislation.

Under the regulation, the definition of personal data should be interpreted as broadly as possible to reflect the ways that organizations collect data about individuals [17]. Personal data are defined as any information that can be used alone or together with other data to identify an individual. In the current technological context, this includes location data, IP addresses, device identifiers, biometric data, audio and visual formats and profiling based on browsing and purchasing behavior. Personal data do not need to be objective; it can also be data about opinions, preferences and posts on social media. The GDPR aims to give EU citizens more control over their data by requiring explicit consent (“opt-in”) and giving individuals the right to withdraw their consent and request the deletion of their data.

The GDPR also expanded its territorial scope, applying to all companies processing the personal data of EU residents, regardless of location. Privacy policies, a fundamental aspect of the GDPR’s transparency principle, must be easily accessible and written in clear and plain language. They should provide concise information about:

- The data retention period;

- The data subject’s rights;

- Information about the automated decision-making system, if used;

- The data controller’s identity and contact details;

- The data protection officer’s contact details, where applicable;

- All the purposes of and the legal basis for data processing;

- Recipients of the personal data;

- If the organization intends to transfer to a third country or international organization.

The GDPR emphasizes making privacy policies accessible and easy to understand. The information provided in them must be “in a concise, transparent, intelligible, and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language”. Furthermore, “the information shall be provided in writing, or by other means, including, where appropriate, by electronic means” (Article 12).

2.2. “Notice and Choice” in the United States

In the US, there is no single national law regulating the collection and use of personal information. The government has approached privacy and security by only regulating certain sectors: the so-called “sectoral” or “patchwork” approach. One of the first federal laws was the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) from 1998, which regulated online data collection of data from children under 13 years old.

The leading framework for Internet privacy in the US is guided by the fair information practice principles of the Federal Trade Commission, a set of guidelines for privacy-friendly data practices in the online marketplace [18]. They take the form of recommendations and are not legally enforceable. At the heart of these recommendations are the principles of “notice and choice”, also known as “notice and consent”. Companies are required to inform individuals about data collection and use through privacy notices, and individuals must consent to data processing before it takes place.

While no generally applicable law exists in the United States, some states have implemented legislation governing privacy policies. The California Online Privacy Protection Act (CalOPPA) of 2003, for instance, required commercial websites that collect personally identifiable information about California residents to include a privacy policy on their homepage.

A more recent and comprehensive law was the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which came into force in 2020. This law requires companies to explain their privacy practices in a notice and gives consumers more control over their personal information. The CCPA established privacy rights, including the right to know what personal information a business collects and how it is shared, the right to delete collected personal information upon request, and the right to opt-out of the sale of personal information. Similar laws will come into force in Colorado, Connecticut, Virginia and Utah from 2023.

3. Automated Privacy Policy Research

Automated privacy policy analysis, including machine learning methods, has grown in popularity during the last decade. The main goal was to grant users a better understanding of how their data are used and help them make informed decisions regarding their privacy. This section provides an overview of the recent research efforts with a focus on English language website policies.

3.1. Privacy Policy Datasets

Various privacy policy datasets have been made accessible to researchers (see Table 1), with the Usable Privacy Policy Project [19] playing a significant role in this regard. Their OPP-115 corpus [20] contains annotated segments from 115 website privacy policies, enabling advanced machine learning research and automated analysis. Another dataset from the same project is the OptOutChoice-2020 corpus [21], which includes privacy policy sentences with labeled opt-out choices types. PolicyIE [22] offers a more recent dataset with annotated data practices, including intent classification and slot filling, based on 31 web and mobile app privacy policies. Nokhbeh Zaeem and Barber [23] created a corpus of over 100,000 privacy policies, categorized into 15 website categories, utilizing the DMOZ directory. PrivaSeer [12] is a privacy policy dataset and search engine containing approximately 1.4 million website privacy policies. It was built using web crawls from 2019 and 2020, utilizing URLs from “Common Crawl” and the “Free Company Dataset”. Finally, Amos et al. [7] released the Princeton-Leuven Longitudinal Corpus of Privacy Policies, a large-scale longitudinal corpus spanning two decades, consisting of one million privacy policy snapshots from around 130,000 websites, enabling the study of trends and changes over time.

Table 1.

Publicly available privacy policy datasets.

3.2. Classification and Information Extraction

Classification and information extraction from privacy policies have been widely explored using machine learning techniques. Kaur et al. [11] employed unsupervised methods such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) and term frequency to analyze keywords and content in 2000 privacy policies. Supervised learning approaches have also been utilized, including classifiers trained on the OPP-115 dataset. Audich et al. [24] compared the performance of supervised and unsupervised algorithms to label policy segments, while Kumar et al. [25] trained privacy-specific word embeddings for improved results. Deep learning models like CNN, BERT, and XLNET have further enhanced their classification performance [26,27,28]. Bui et al. [29] tackled the extraction of personal data objects and actions using a BLSTM model with contextual word embeddings. Alabduljabbar et al. [30,31] proposed a pipeline called TLDR for the automatic categorization and highlighting of policy segments, enhancing user comprehension. Extracting opt-out choices from privacy policies has also been studied [21,32,33]. In the field of summarization, Keymanesh et al. [34] introduced a domain-guided approach for privacy policy summarization, focusing on labeling privacy topics and extracting the riskiest content. Several studies have worked on developing automated privacy policy question-answering assistants [35,36,37].

Furthermore, the PrivacyGLUE [38] benchmark was proposed to address the lack of comprehensive benchmarks specifically designed for privacy policies. The benchmark includes the performance evaluations of transformer language models and emphasizes the importance of in-domain pre-training for privacy policies.

3.3. Privacy Policy Applications for Enhancing Users’ Comprehension

Applications enhancing the comprehension of privacy policies have been developed to provide users with useful and visually appealing presentations of policy information. PrivacyGuide [39] employs a two-step multi-class approach, identifying relevant privacy aspects and predicting risk levels using a trained model on a labeled dataset. The user interface utilizes colored icons to indicate risk levels. Polisis [40,41] combines a summarizing tool, policy comparison tool, and chatbot. The query system employs neural network classifiers trained on the OPP-115 dataset and privacy-specific language models. PrivacyCheck is a browser extension that extracts 10 privacy factors and displays their risk levels through icons and text snippets [42,43,44,45]. Opt-Out Easy is another browser extension that utilizes the OptOutChoice-2020 dataset to identify and present opt-out choices to users during web browsing [21,46].

3.4. Regulatory Impact

User research has also focused on evaluating privacy policies for regulatory compliance, particularly in response to the implementation of General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe. The tool Claudette detects unfair clauses and evaluates privacy policy compliance with GDPR [47,48]. KnIGHT (“Know your rIGHTs”) utilizes semantic text matching to map policy sentences to GDPR paragraphs [49]. Cejas et al. [50] and Qamar et al. [51] leveraged NLP and supervised machine learning to identify GDPR-relevant information in policies and assess their compliance. Similarly, Sánchez et al. [52] used manual annotations and machine learning to tag policies based on GDPR goals, offering both aggregated scores and fine-grained ratings for better understanding. Degeling et al. [53] and Linden et al. [54] examined the effects of GDPR on privacy policies through longitudinal analysis, observing updates and changes in policy length and disclosures. Zaeem and Barber [55] compared pre- and post-GDPR policies using PrivacyCheck, highlighting deficiencies in transparency and explicit data processing disclosures. Libert [56] developed an automated approach to audit third-party data sharing in privacy policies.

3.5. Comprehensibility of Privacy Policies

Studies on privacy policy comprehensibility have examined deficiencies in readability, revealing that privacy policies are difficult to read and demonstrating correlations between readability measures [9,10]. Furthermore, researchers have examined the changes in length and readability of privacy policies over time [4,7].

Other scholars have studied ambiguous content in privacy policies. Kaur et al. [11] and Srinath et al. [12] analyzed the use of ambiguous words in a corpus of 2000 policies. Furthermore, Kotal et al. [57] studied the ambiguity in the OPP-115 dataset and showed that ambiguity negatively affects the ability to automatically evaluate privacy policies. Srinath et al. [12] reported on privacy policy length and the use of vague words in their PrivaSeer corpus of policies. Lebanoff and Liu [14] investigated the detection of vague words and sentences using deep neural networks. The present work improved the prediction performance regarding sentence classification using a BERT architecture. This paper also contributed to the literature by providing a longitudinal analysis of trends related to ambiguity.

3.6. Mobile Applications

While the focus of the present overview is on website policies, the research community has also examined privacy policies in the context of mobile applications, establishing several corpora of mobile app privacy policies [58,59]. Those policies are well-suited for compliance analysis, because they are studied along with the app code and the traffic generated by the app [59,60].

4. Data and Methods

4.1. The Princeton-Leuven Longitudinal Corpus of Privacy Policies

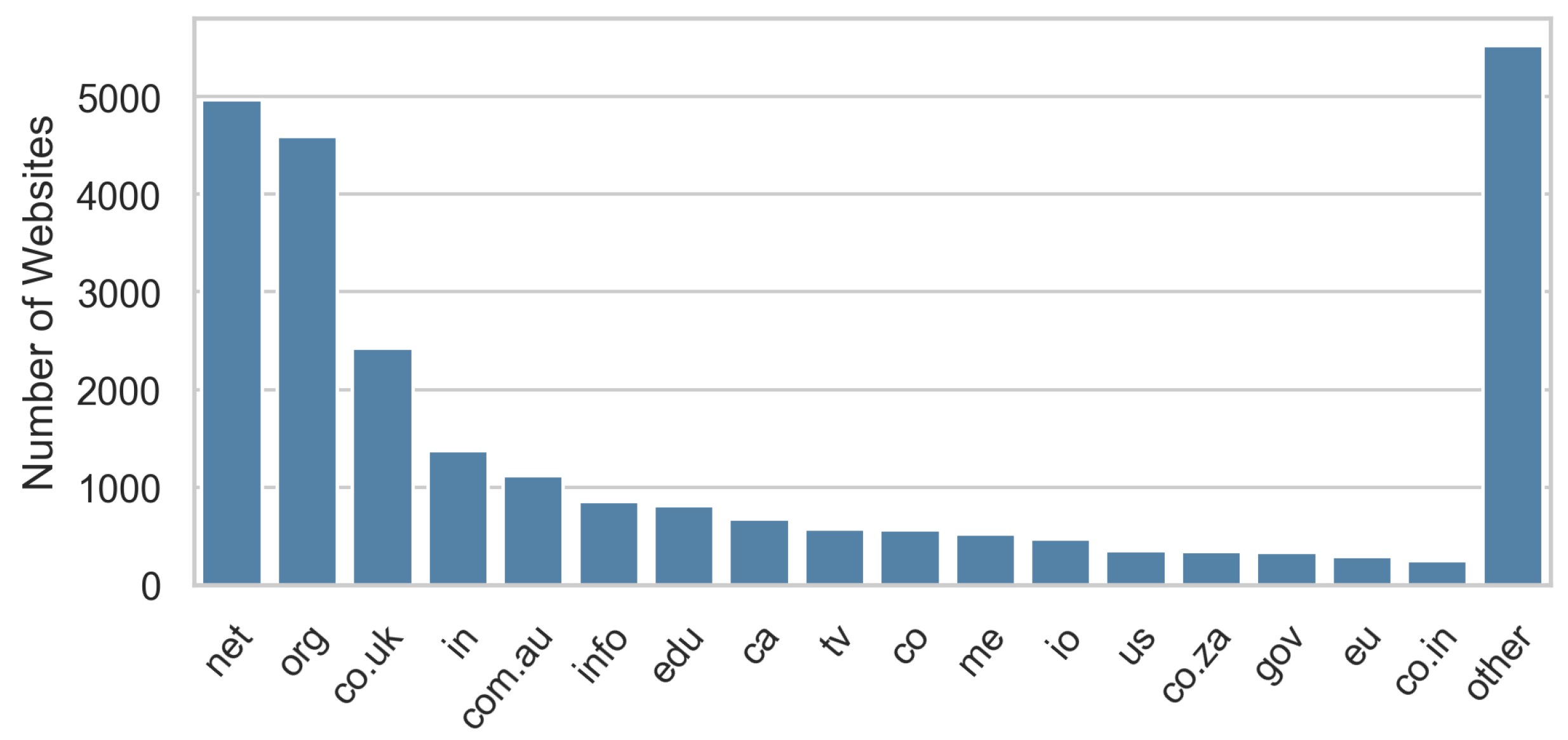

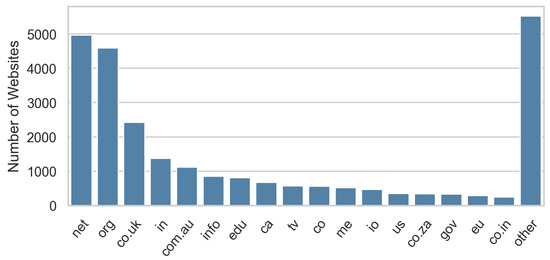

This analysis of the privacy policy landscape is based on the Princeton-Leuven Corpus, a historical dataset of English-language privacy policies spanning over two decades [7]. It contains 910,546 policy snapshots of 108,499 distinct websites, which have been selected based on the Alexa’s top 100,000 lists between 2009 and 2019. The original dataset consisted of 1,071,488 policy snapshots of over 130,000 sites. In the course of additional quality control, Amos et al. [7] removed real policies that might lead to a biased analysis (e.g., the policies of domain-parking services). The remaining dataset they refer to as the “analysis subcorpus”, which is the one used in this study. The websites are distributed over 575 different top-level domains, with “.com” being the most frequent (76% of the websites). Figure 1 shows the distribution across the remaining domains.

Figure 1.

Distribution of top-level domains in the dataset (.com excluded).

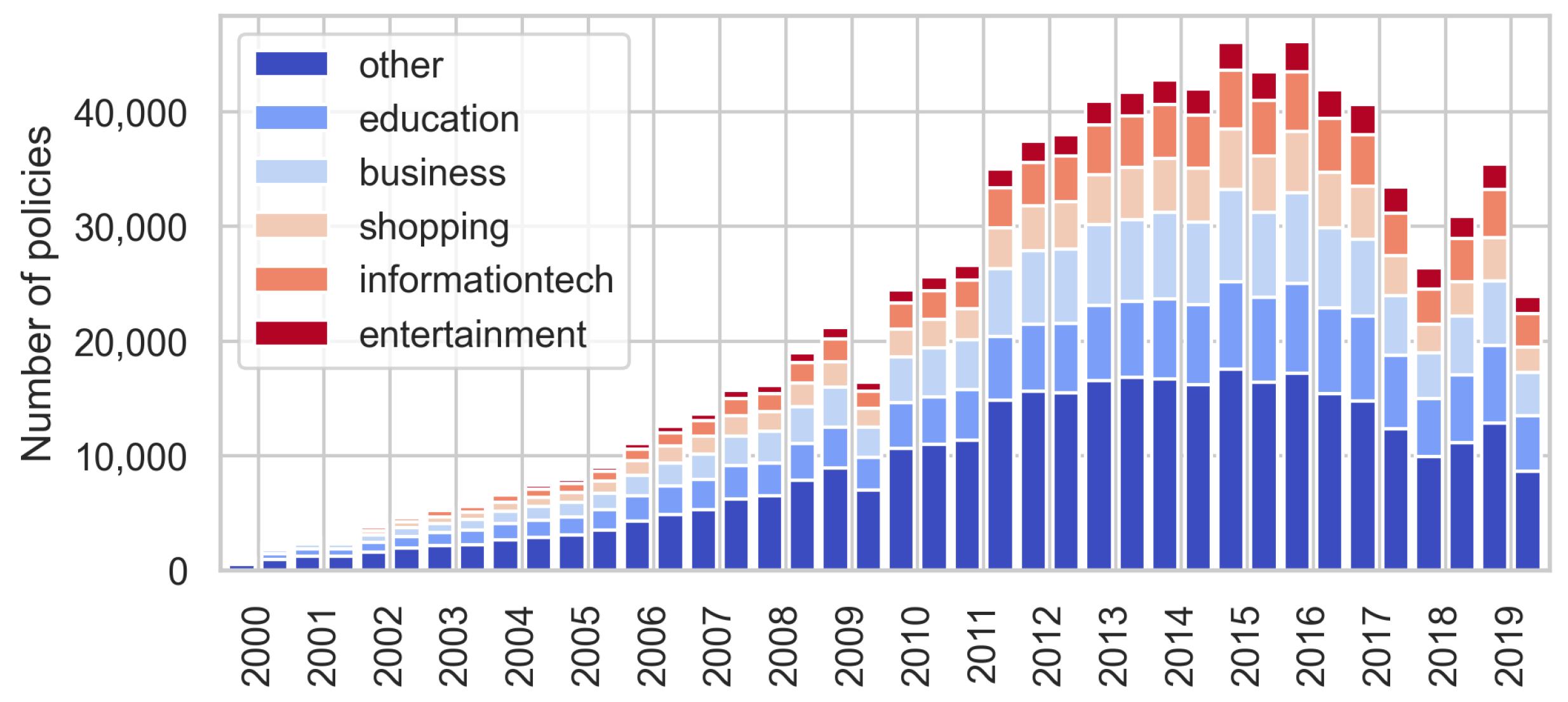

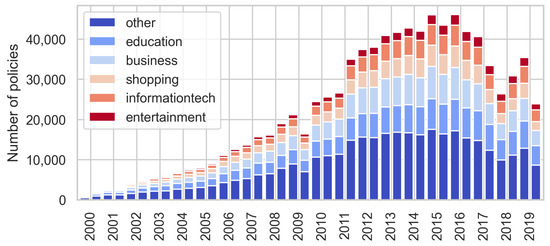

For each website, two snapshots per year were retrieved, creating a crawler that discovered, downloaded, and extracted archived privacy policies from the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine [61]. Available snapshots were included for the years before 2009 and up to the first year for which Internet Archive has crawls. One snapshot was retrieved from the first half of the year (January–June) and another from the second half (July–December). These six-month spans were referred to as intervals and they were the basic time units in the data analysis. After the crawling, there was a series of validation and quality control steps, including language checks to remove non-English policies. For detailed information about the data collection methodology, consult the original paper by Amos et al. [7]. Figure 2 presents the distribution of the policy snapshots over time and across the most frequent website categories.

Figure 2.

Distribution of policy snapshots per interval and category. Each bar represents an interval (two intervals per year).

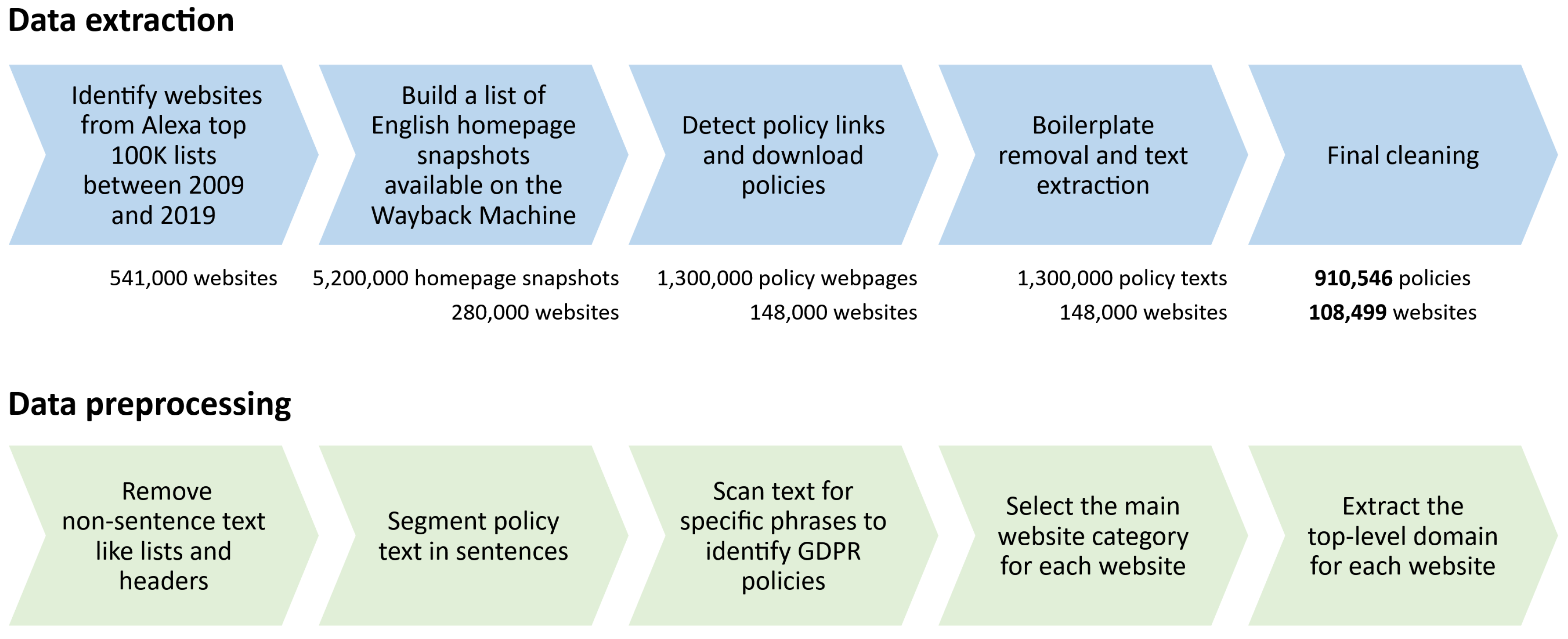

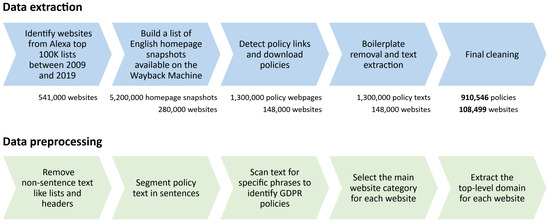

The analysis in this paper focuses on the period after 2009, as the majority of policies are from these years. Additionally, Alexa rank data are only available for this timeframe. Since the provided dataset only covers up to 2019, we do not consider the period beyond that. Our data preparation phase involved extracting only the sentence text from privacy policies. This step was necessary because the analysis relied on sentence counts and sentence classification. Non-sentence content such as headers, short lists, tables, and links was removed. After applying various data cleaning steps, each policy text was segmented into sentences using the sentence tokenizer from the NLTK library [62]. A manual check revealed that short sentences were mostly noisy, so those containing fewer than three words were removed. Data extraction and preparation stages are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Data extraction (by Amos et al. [7]) and further preprocessing (this study).

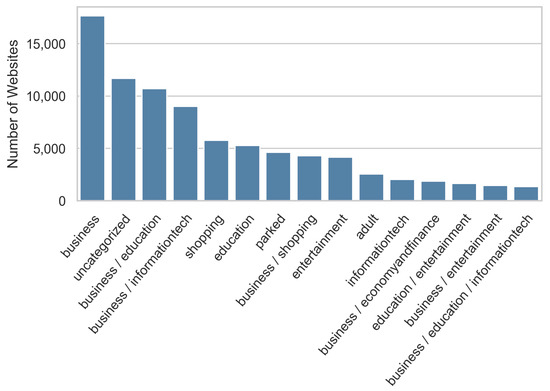

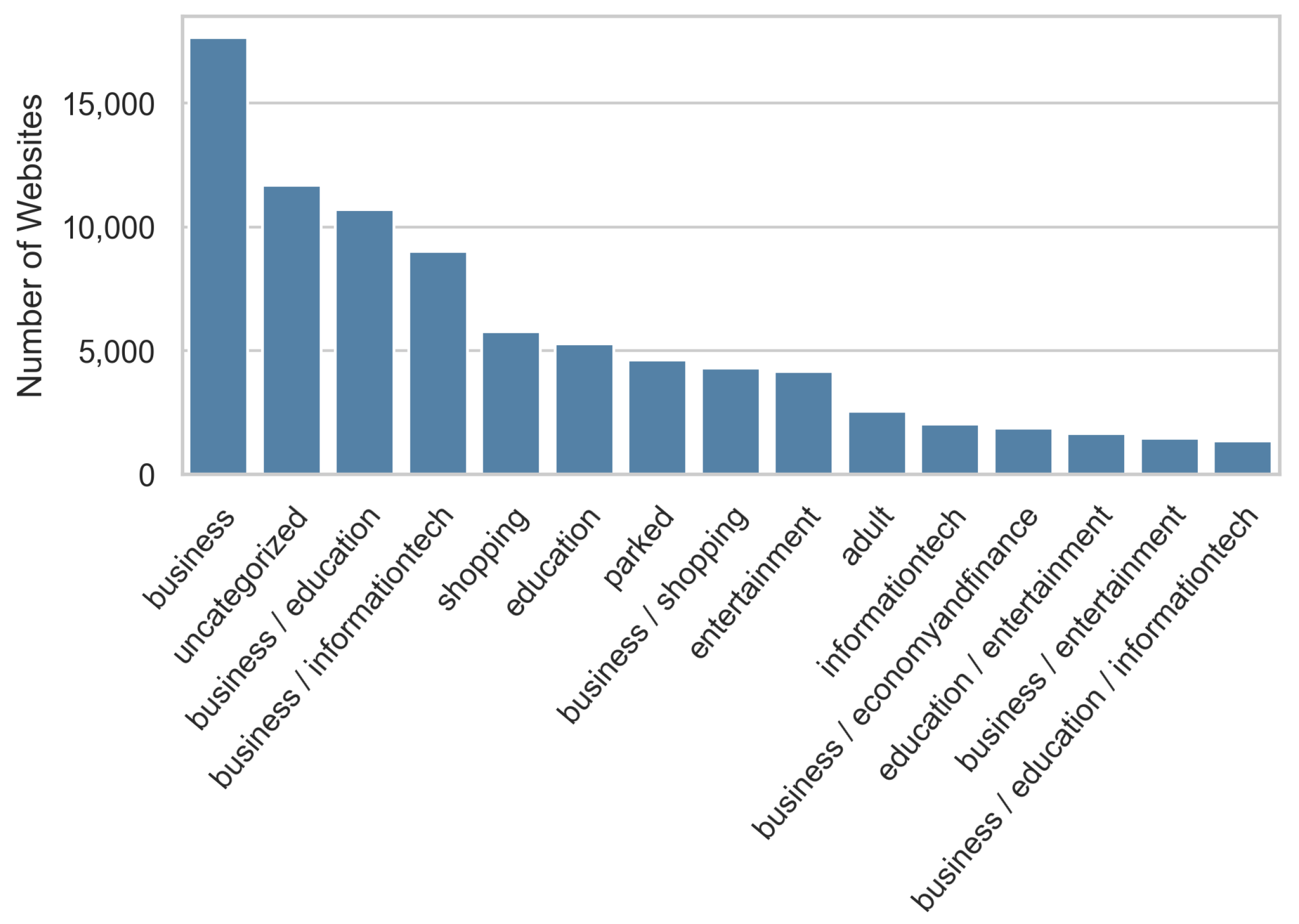

The dataset included information on website categories from the domain categorization API Webshrinker [63]. The websites were distributed over 481 unique combinations of 27 top-level categories like business, shopping, and education, but a small number of categories dominated the dataset.

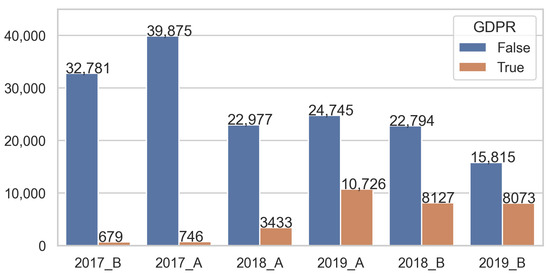

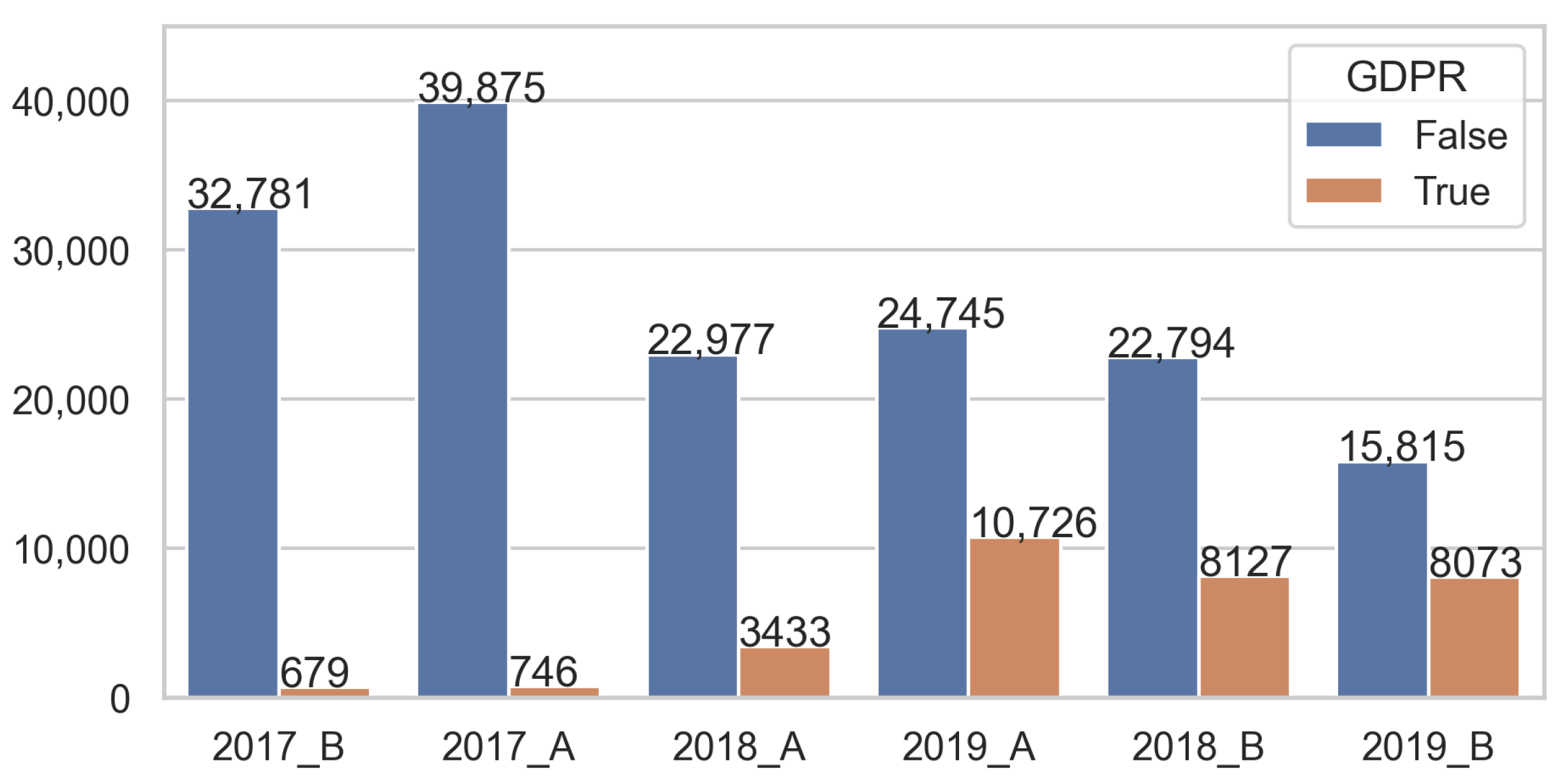

To identify GDPR policies, the text was scanned for “GDPR”, “General Data Protection Regulation” or one of the GDPR-related phrases provided by Amos et al. [7]. Refer to Appendix A for comprehensive information on category distribution and the measure of GDPR content.

4.2. Measuring Readability of Privacy Policies

The analysis of privacy policy readability focused on three key factors: policy length, passive voice usage, and reading difficulty, as measured by the Dale–Chall readability formula. To assess the policy length, the mean and median sentence counts were reported for each interval. Passive voice usage was quantified using a passive voice index. This index was derived by dividing the number of passive voice structures by the total number of sentences in a given policy. In essence, the passive voice index represents the average number of passive voice structures per sentence. The identification of passive voice structures in the policy text followed a methodology similar to that presented by Linden et al. [54].

Many readability metrics, such as the Flesch Readability Ease Score (FRES), the Flesh-Kincaid Grade Level (FKG), the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG), rely on word complexity measured by the number of characters or syllables and sentence length. A drawback of most of these formulas is their failure to account for the semantic difficulty of the words used [7].

To analyze the development of policies’ reading complexity, we used the new Dale–Chall readability formula (see Equation (1)). Unlike other formulas, the Dale–Chall uses a count of semantically difficult words, classified as such because they do not appear on a list of common words familiar to most fourth-grade students. The new Dale–Chall formula expanded the list of the initial 763 familiar words to 3000 words [64]. The expanded list of words is available here: https://readabilityformulas.com/word-lists/the-dale-chall-word-list-for-readability-formulas (accessed on 15 November 2023). An adjusted version of the Dale–Chall score was converted to US grade level based on a correction table (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Readability grades according to the new Dale–Chall formula.

Please consult Appendix B for the outlier analyses of the calculated measures presented in this and the following section.

4.3. Measuring Ambiguity in Privacy Policies

4.3.1. Taxonomy of Vague Terms

Qualifiers like “may”, “can”, “could”, and “possibly” introduce uncertainty, creating imprecision and ambiguity. This study refers to these words as “vague terms”. Similarly, phrases such as “depending”, “as needed”, and “as applicable” indicate conditional validity, complicating readers’ ability to discern specific circumstances for described processes. For instance, “We may disclose your personal information if necessary to enforce our User Agreement”.

Additionally, phrases like “including” and “such as” within lists imply incomprehensive specification (refer to example in Table 3). Generalizing terms like “generally” or “usually” lead to abstraction, hampering precise information identification, as seen in “Generally we will store and process your information within the UK”.

Table 3.

Taxonomy of vague terms. Adapted from Reidenberg et al. [6].

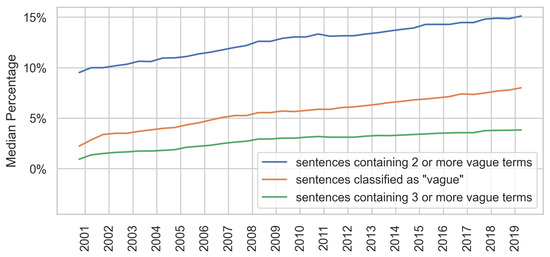

In their research on “Ambiguity in Privacy Policies and the Impact of Regulation”, Reidenberg et al. [6] developed a comprehensive vague term taxonomy. Analyzing 15 policies across different sectors, they categorized 40 vague terms into four types, as illustrated in Table 3. This taxonomy served as a foundation for ambiguity measurement in privacy policies. For each policy, the number of sentences containing at least one, two, or three vague terms was divided by the overall number of sentences. To show the progression of ambiguity over time, we used the median number of all policies for each time interval.

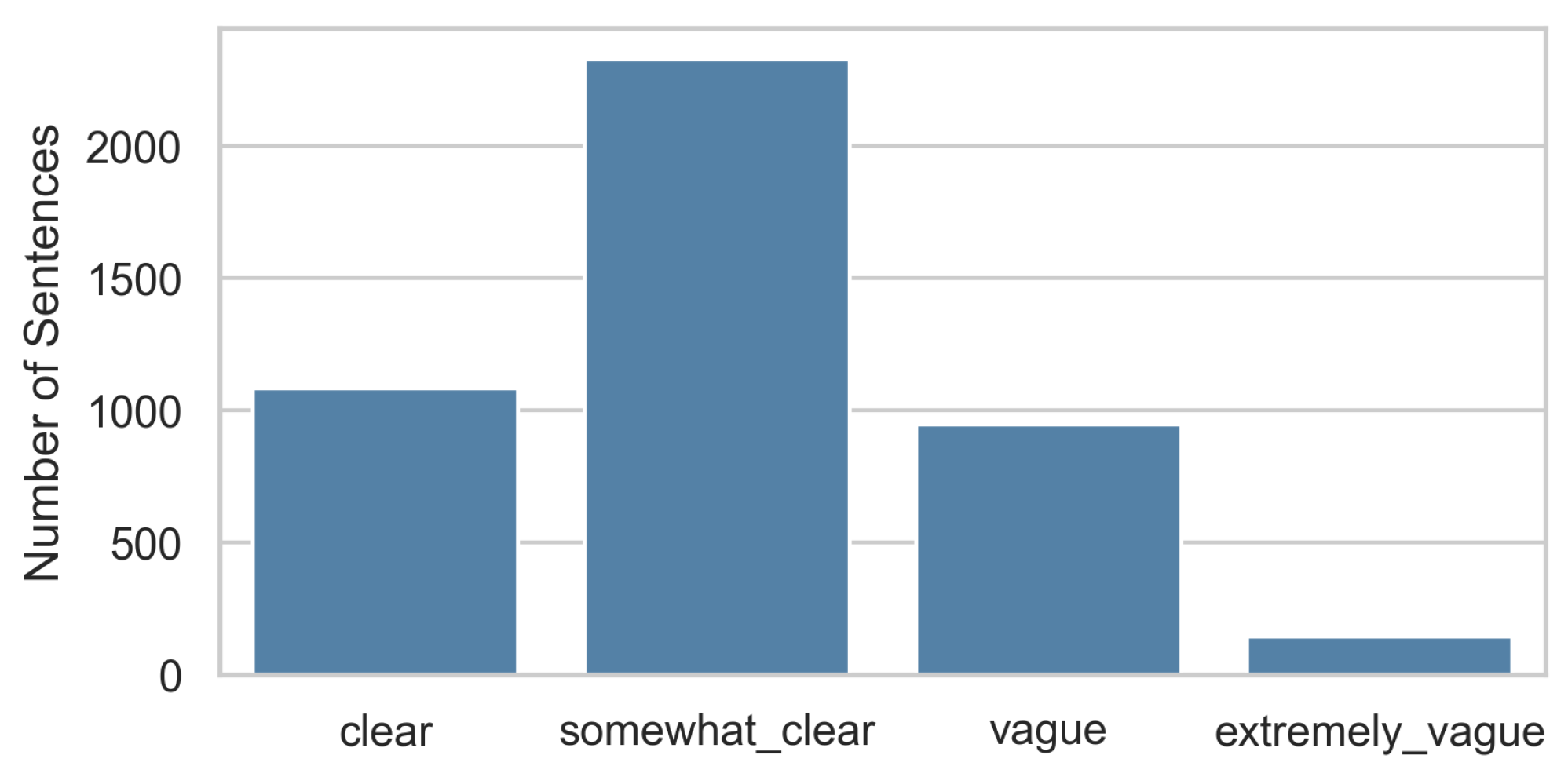

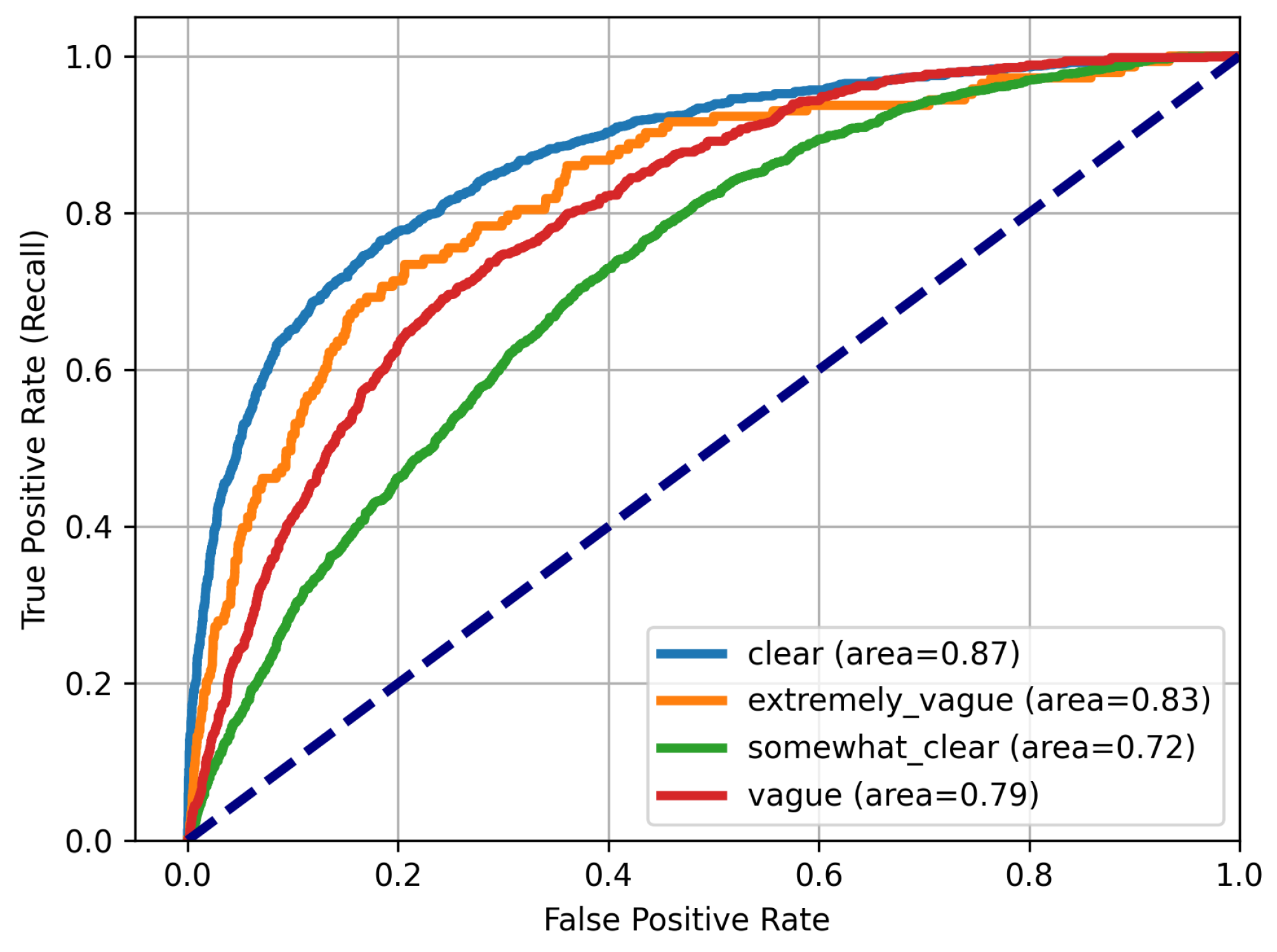

4.3.2. Language Model for Vagueness Prediction

A further evaluation of the ambiguity was conducted using the corpus on vagueness in privacy policies made available by Lebanoff and Liu [14]. The corpus consisted of human-annotated sentences extracted from 100 privacy policies. A group of five annotators were instructed to rate the sentences on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 meant “clear” and 5 meant “extremely vague”. The authors only selected potentially vague sentences to help balance the dataset using the taxonomy of vague words introduced in this section. Sentences containing at least 1 of the 40 cue words were considered to have a higher chance of being labeled as vague by the annotators. The overall size of the corpus amounted to 4500 sentences.

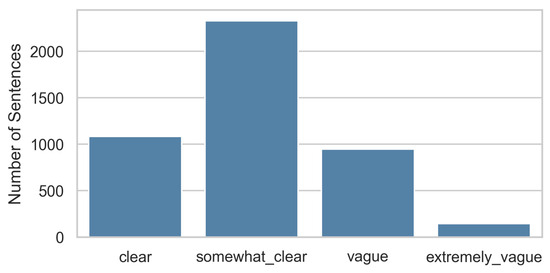

To predict the vagueness of the sentences, a language model was trained on these data. The annotations were aggregated according to the majority voting rule: if three or more annotators agreed on a given score, it was considered the final score. In the case of disagreement between the annotators, the average of the five scores was taken. Following the methodology of Lebanoff and Liu [14], the aggregate score s was grouped into four categories:

- → clear

- → somewhat clear

- → vague

- → extremely vague

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the categories. An “ambiguity score” for each policy snapshot in the longitudinal dataset illustrates the development of ambiguity over time. This score represents the number of sentences classified either as vague or extremely vague and normalized by the total number of sentences in the policy (i.e., the percentage of vague sentences). Another metric we reported was the percentage of sentences, labeled as clear.

Figure 4.

Distribution of vagueness categories.

Predicting the vagueness level of a sentence is a multi-class sentence classification task that we approached using transfer learning with a pre-trained BERT model.

The model was fine-tuned using Fast-BERT, a deep learning Python library for training BERT-based models for text classification. The library repository is located at https://github.com/utterworks/fast-bert (accessed on 15 November 2023). Fast-BERT is built on the foundations of the Hugging Face BERT PyTorch interface [65]. For this study, we used the “BertForSequenceClassification” model, a BERT model with an added linear layer for classification, as a sentence classifier. The small “BERT base” version was used in particular; it consists of twelve layers, each including 768 hidden units and 12 attention heads resulting in a total of 110 million parameters.

Devlin et al. [66] suggested fine-tuning only on few parameters: the epochs, learning rate, and batch size. They recommended training for just two to three epochs with the Adam optimizer and a batch size of 16 or 32. Table 4 shows the training parameter chosen after manual evaluation. The tokenized input sequence was limited to 256-word piece tokens. Taking into account the length of the sentence, this was sufficient to capture almost all the information it contained.

Table 4.

BERT fine-tuning parameters.

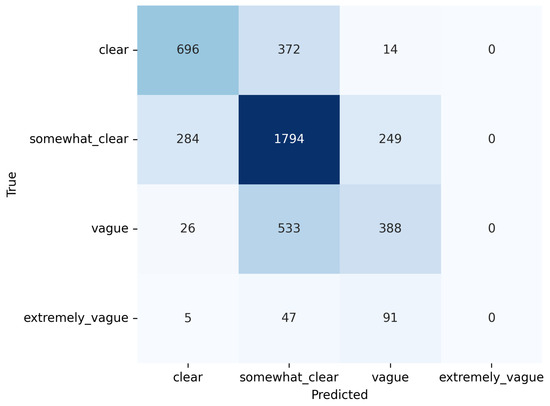

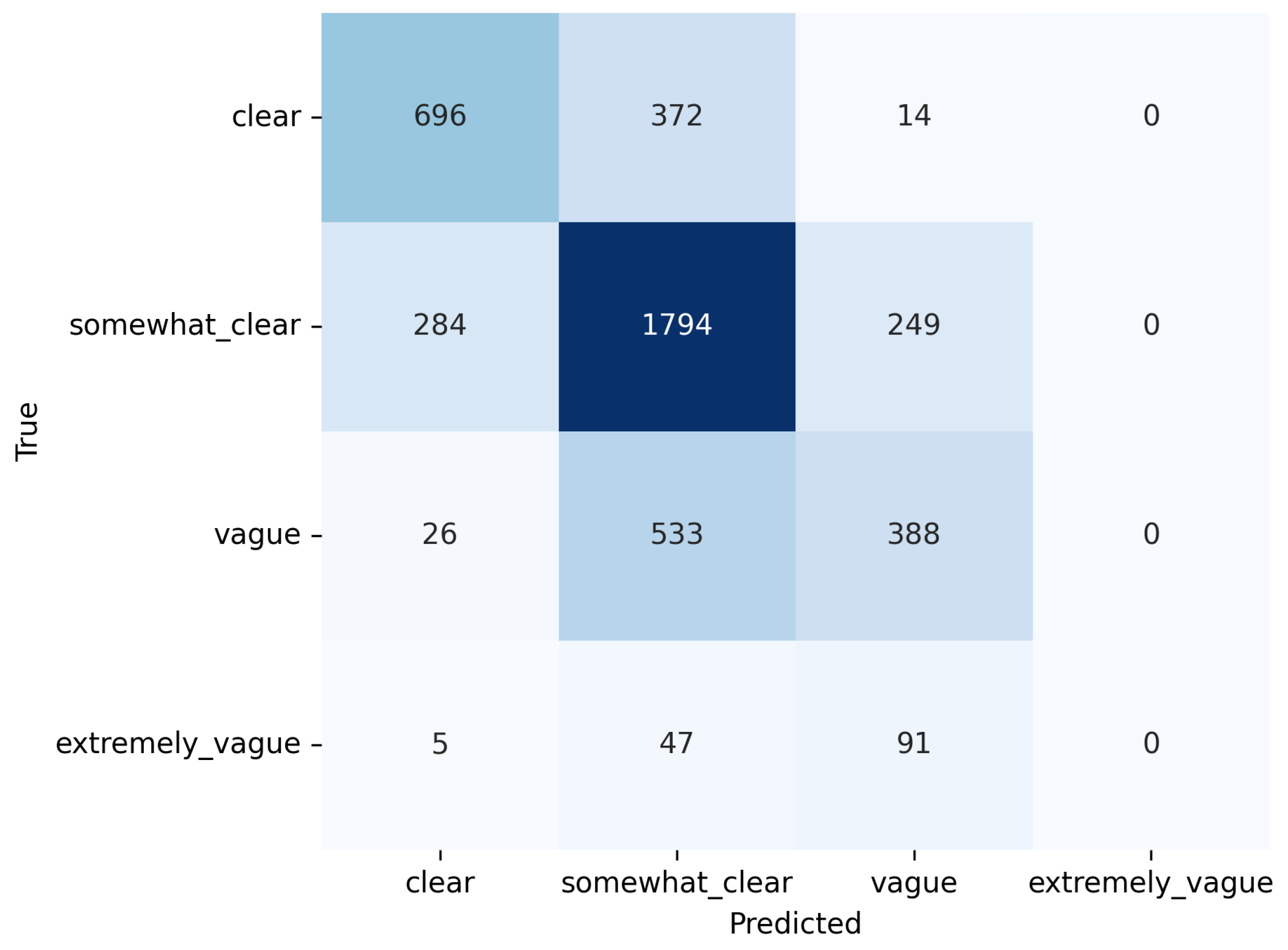

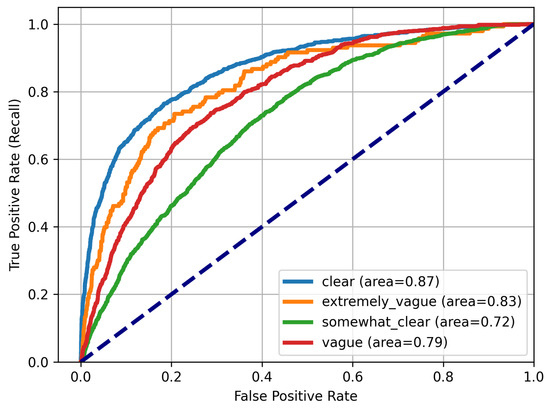

For the fine-tuning, the dataset was divided into the train, test, and validation sets, each the size of, respectively, 3499, 500, and 500 sentences. As Figure 4 shows, the sentences were very unevenly distributed across the four categories. For an imbalanced classification problem, accuracy is not the most suitable measure, because high accuracy is achievable through even a simple model only predicting the majority class. For this kind of problem, the F1 score, composed of precision and recall, is more appropriate. We report those metrics in Table 5.

Table 5.

BERT for sentence classification: model evaluation.

The BERT model was compared to a baseline model and the Auxiliary Classifier Generative Adversarial Networks (AC-GAN) used in the original paper by Lebanoff and Liu [14]. The baseline model is a simple rule-based model that always predicts the majority class. In this case, for every sentence in the validation and test datasets, the “somewhat clear” class is assigned, because this is the most common category in the training dataset. The prediction power of BERT was by far greater than a baseline model and also showed an improvement over the AC-GAN model. However, the results are not directly comparable, because they use a slightly different annotations aggregation scheme. Lebanoff and Liu [14] did not use majority voting and simply took the average of all the annotators. More details about the performance of the model are presented in Appendix C.

4.4. Unveiling Positive Framing in Privacy Policies

Many Internet users have likely encountered phrases like “we value your privacy” or “we take your privacy and security seriously” while using online services. These phrases, aimed at alleviating privacy concerns, are not essential policy information. Positive language, at best, diverts user attention from privacy implications, and at worst, can mislead.

Libert et al. [13] investigated the prevalence of such potentially insincere statements and found that they occur more frequently in privacy policies than in documents such as terms of use. Our study built on this by manually identifying additional phrases beyond those examined by Libert et al. [13]. These phrases were then matched within policy texts using regular expression patterns. The aim was to identify trends in the use of positive phrases, but not to create an exhaustive list. Table 6 provides the illustrative examples of those phrases, while the complete list can be found in Appendix D.

Table 6.

Examples of pacifying statements concerning privacy and security.

5. Results

5.1. Readability

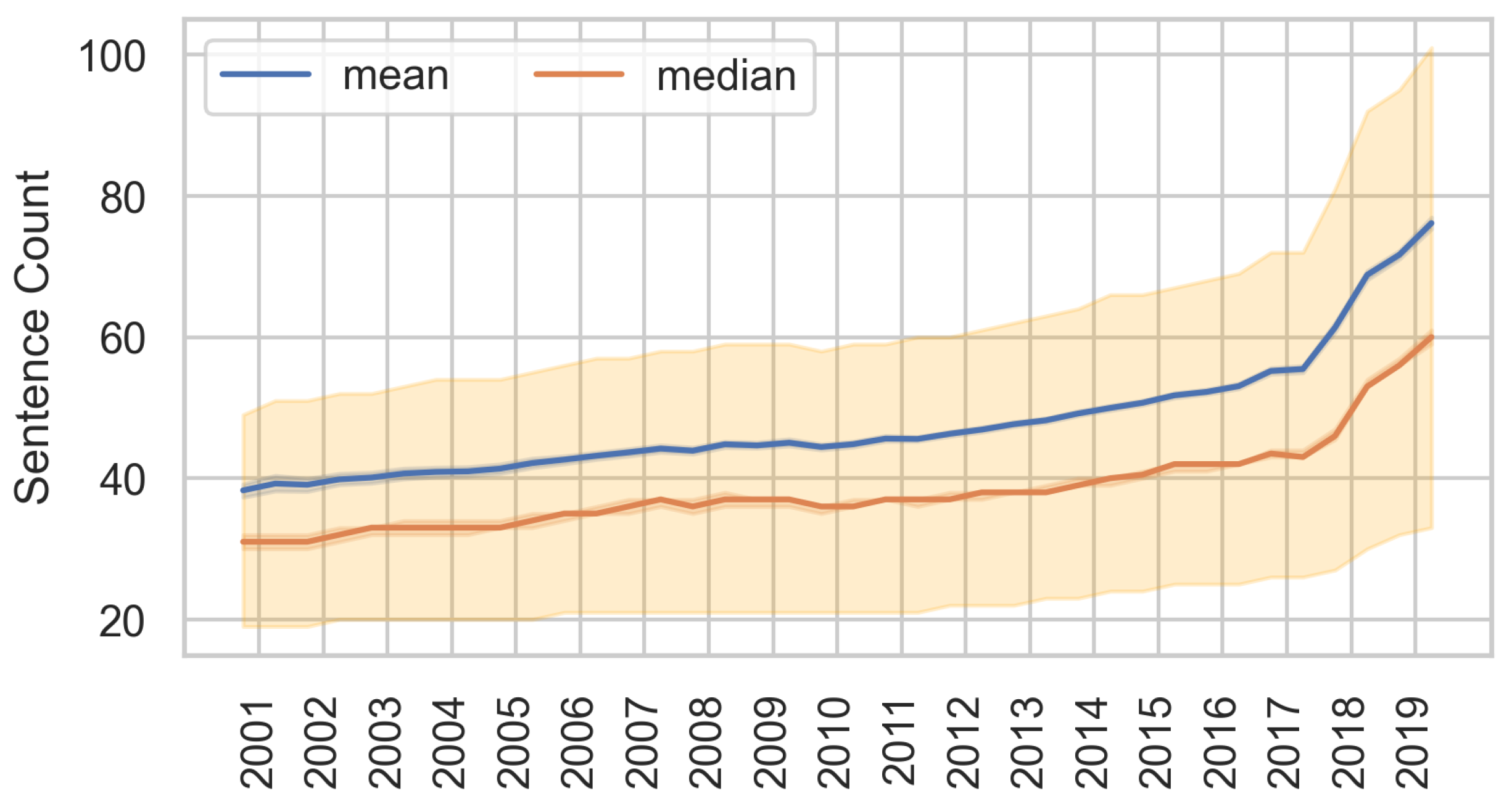

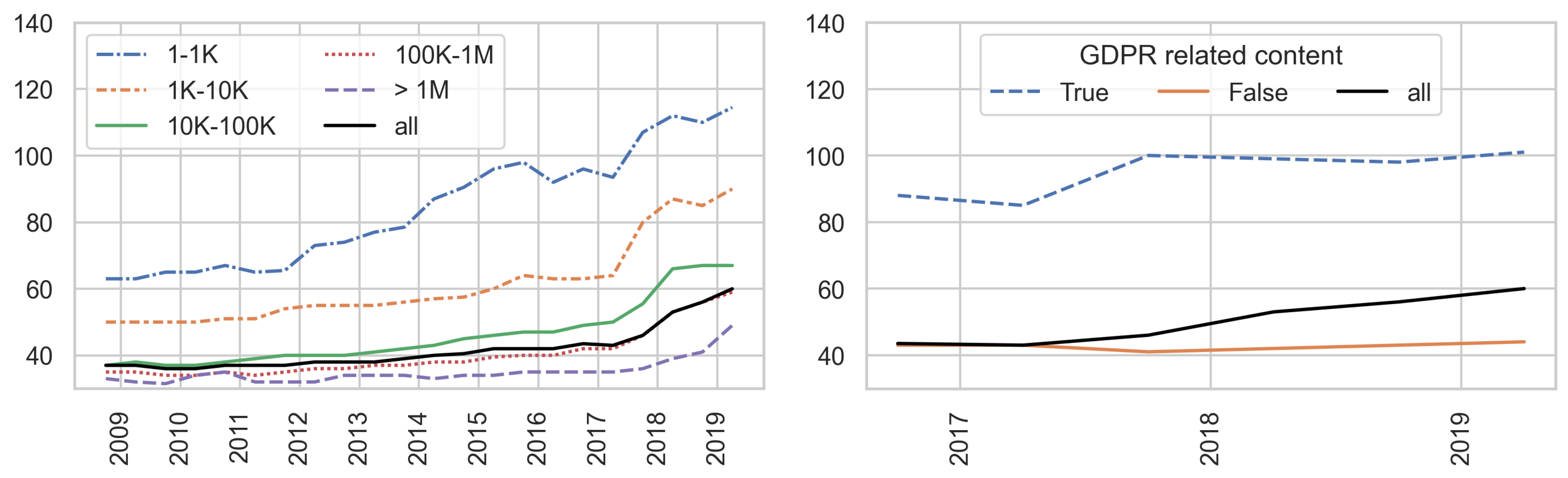

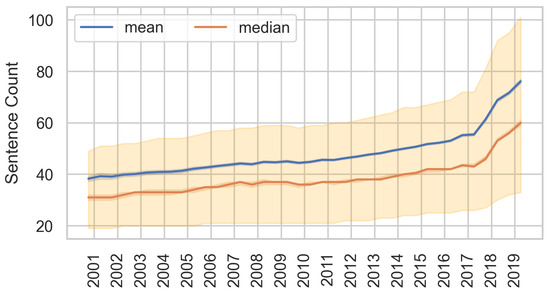

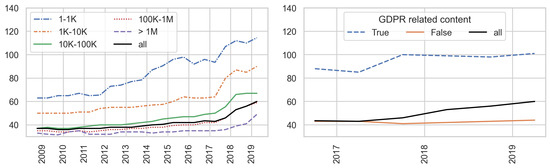

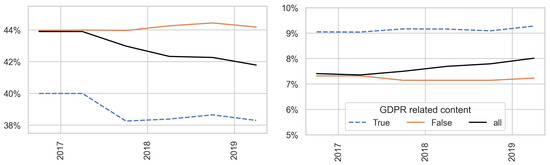

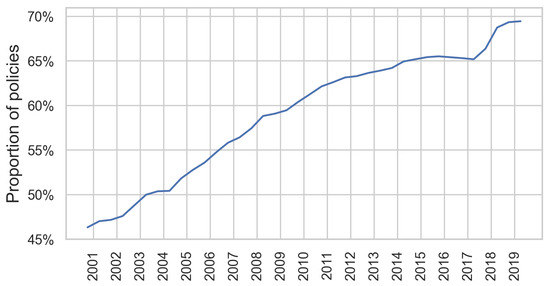

Figure 5 shows the mean and median sentence counts for every interval since 2001. Over 19 years, the average policy length has doubled, with around 30 sentences in 2001 rising up to 60 by 2019. Policy lengths increased more steeply after the first interval of 2018, when the GDPR came into force. Indeed, the length of policies mentioning the GDPR or related phrases was on average double that of those classified as “non-GDPR” (Figure 6-right).

Figure 5.

Sentence count of privacy policies over time. The shaded area indicates the data between the 25th and 75 percentiles.

Figure 6.

Median sentence count of privacy policies by Alexa ranking (left) and by GDPR content (right).

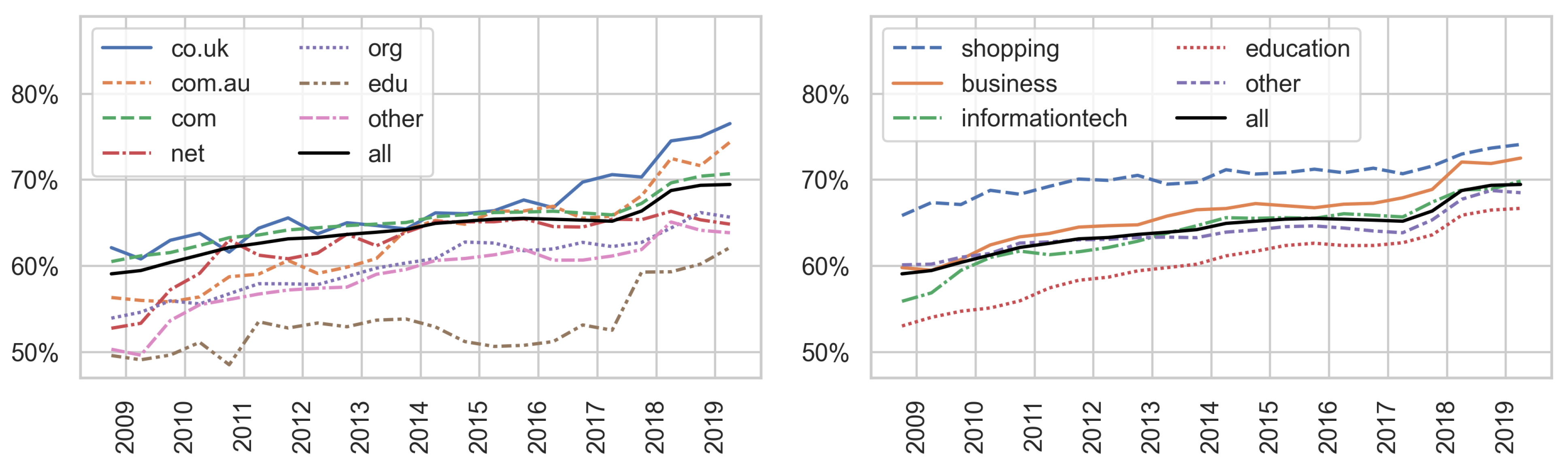

The trend of increasing length remains true across different rank tiers, website top-level domains, and categories. However, the results confirm previous findings that sites ranked higher by Alexa tend to have longer policies [56] and this trend has remained stable over time (Figure 6-left). In 2019, the median length of the top 1000 ranked policies in the dataset was 114.5 sentences, nearly twice the length of website policies with rankings between 100,000 and 1,000,000 (59 sentences).

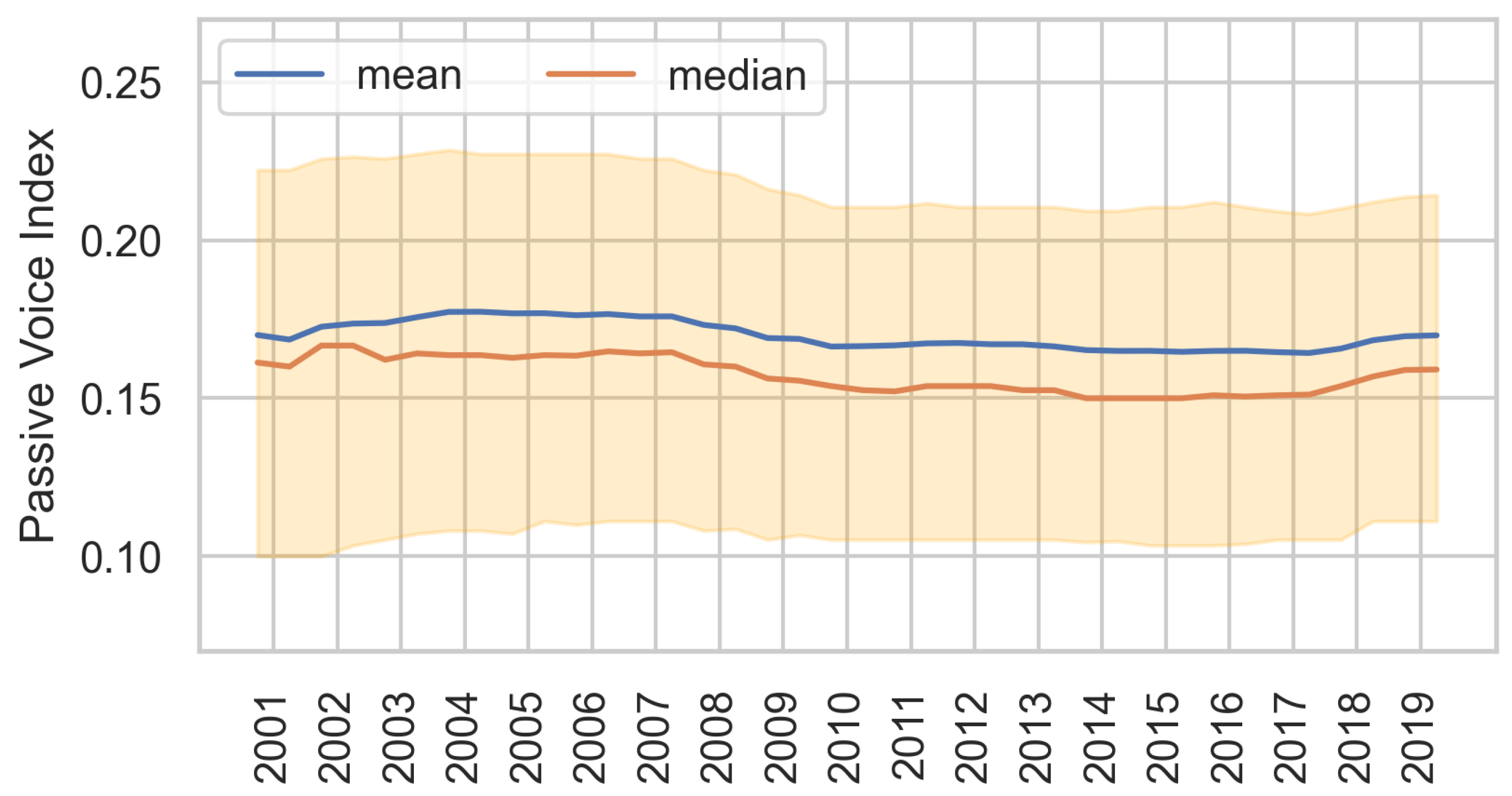

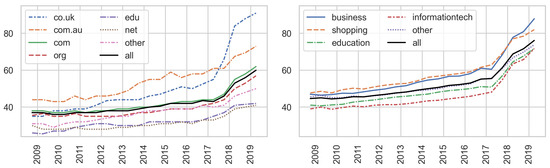

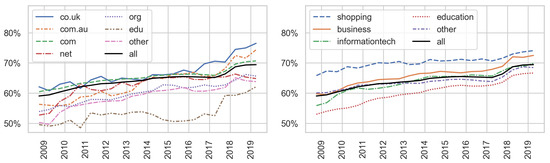

Regarding the top-level domain, the holders of the co.uk and com.au domains provide policies of above-median lengths. These domains are typically used for UK and Australian commercial websites. In contrast, .edu and .net websites have the shortest policies, averaging around 40 sentences in 2019 (Figure 7-left). We also analyzed the policy length of the most frequent categories of websites present in the dataset. Shopping and business websites have longer policies, whereas information tech sites’ policies are shorter on average. However, the results showed that the differences between categories remain small in size (Figure 7-right).

Figure 7.

Median sentence count of privacy policies by top-level domain (left) and by website category (right).

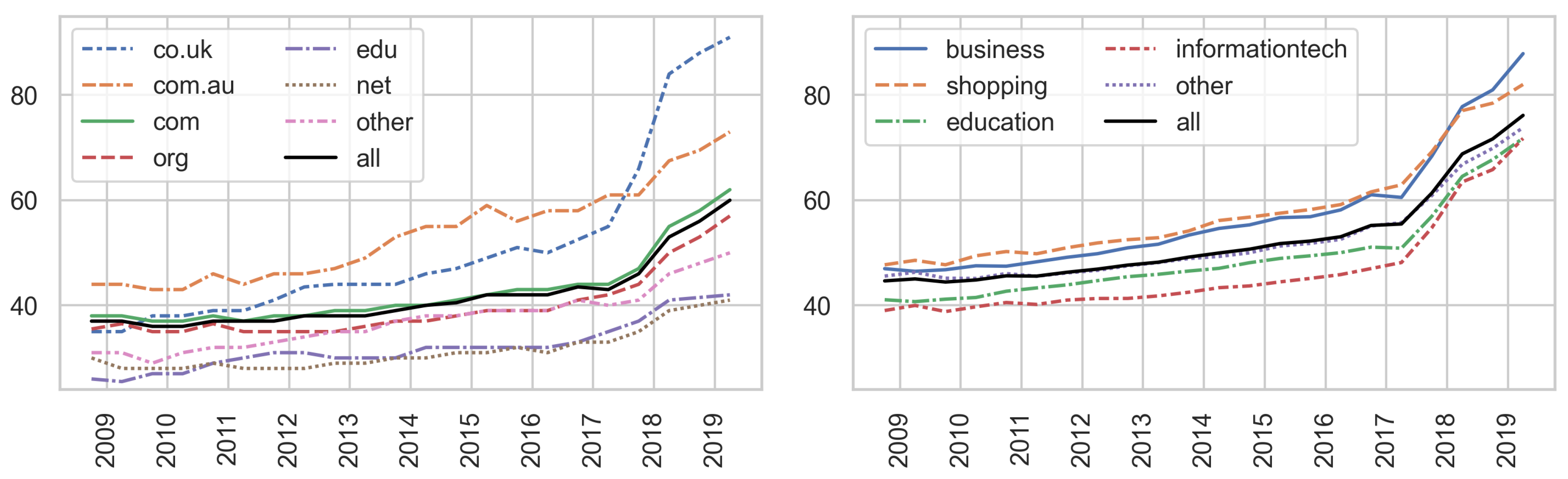

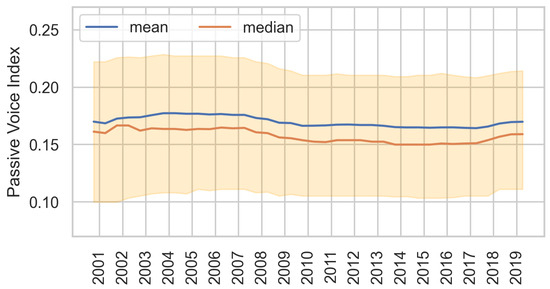

Concerning passive voice structures, the results showed that their usage remained stable over time, with values of 0.15–0.16 (Figure 8). These index values signified the use of one passive voice structure every six sentences on average. The index did not vary considerably across different domains.

Figure 8.

Average passive voice index of privacy policies. The shaded area indicates the interquartile range.

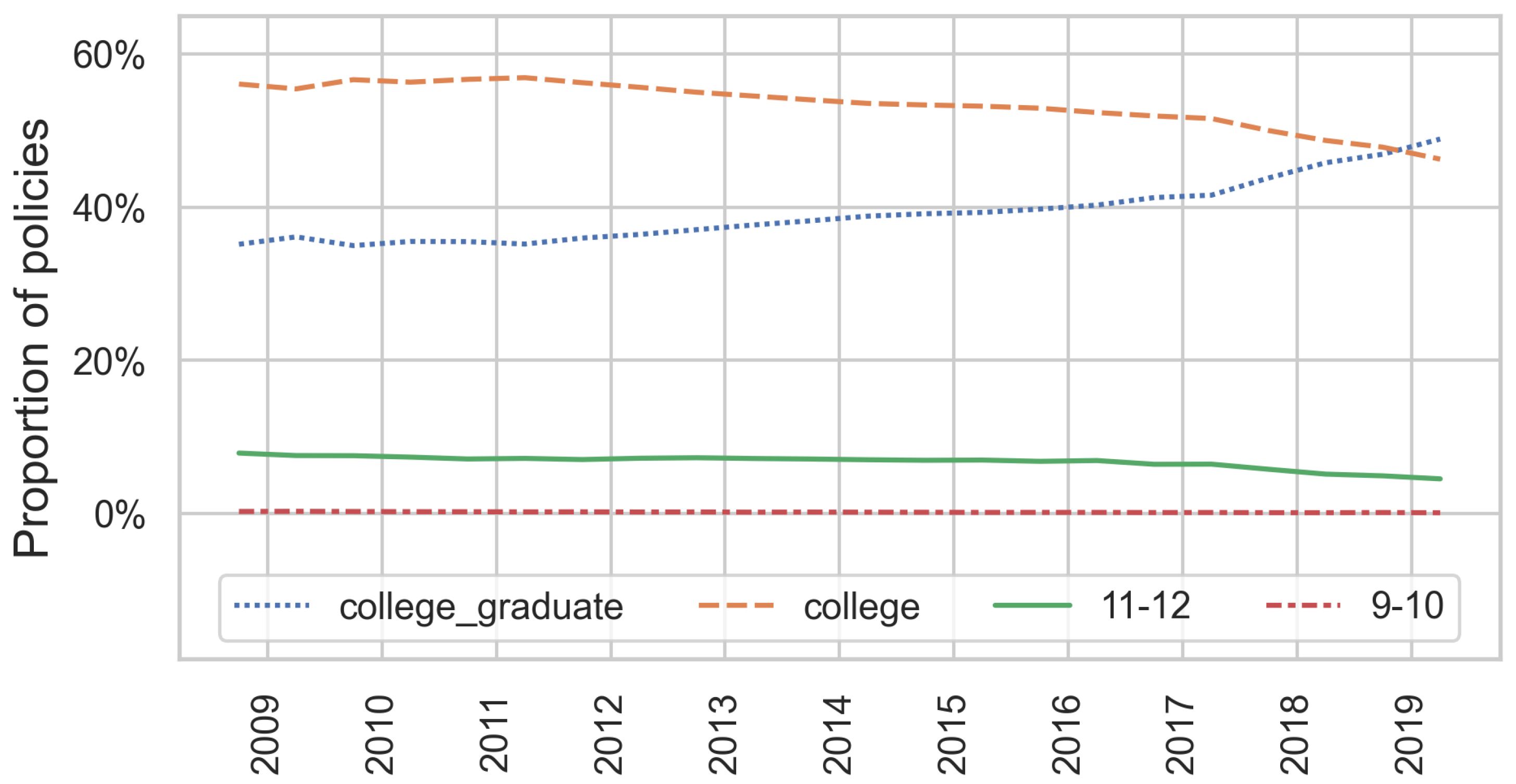

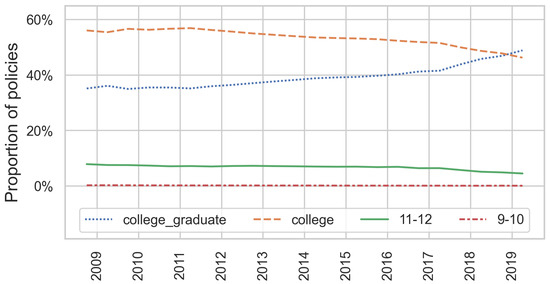

Figure 9 shows the distribution of polices across reading grades over time. The analysis only included polices with more than 100 words, as this metric is not suitable for shorter policies. Furthermore, the 61 policy snapshots requiring 7th or 8th high-school grade are excluded from the visualization (they comprise less than 0.00001% of all snapshots).

Figure 9.

Distribution of the Dale–Chall reading grade levels of privacy policies.

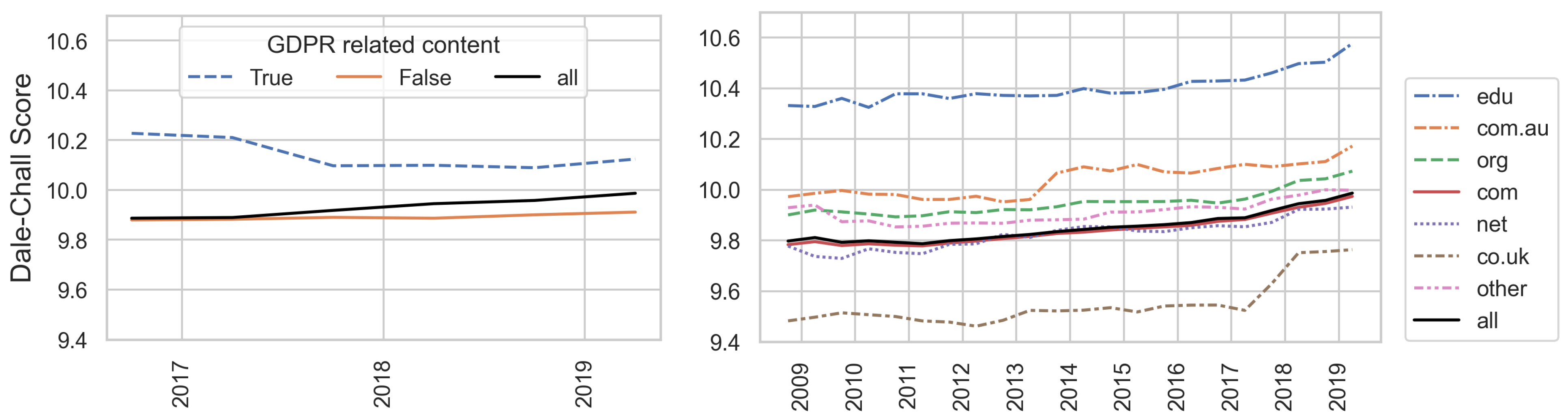

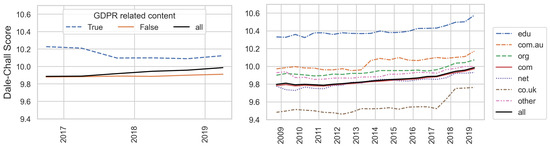

More than 90% of the policies in the dataset were at the reading level of a college student or college graduate. Indeed, 2019 was the first year in which the proportion of polices requiring a college degree was higher than all other groups. These results confirmed the previous findings that privacy policies are difficult to comprehend. This has been shown to be true across all popularity ranks, website categories, and domains. The median DC score increased slightly over time, from 9.8 to 10 over a 10 year span. The GDPR’s policies were shown to be less readable with a DC score of about 0.2 higher than the median. Policies in the .edu domain were also less readable (scoring about 0.6 higher than the median). See Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Median Dale–Chall readability score of privacy policies by GDPR content (left) and by top-level domain (right).

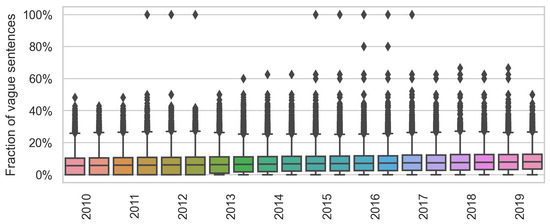

5.2. Ambiguity

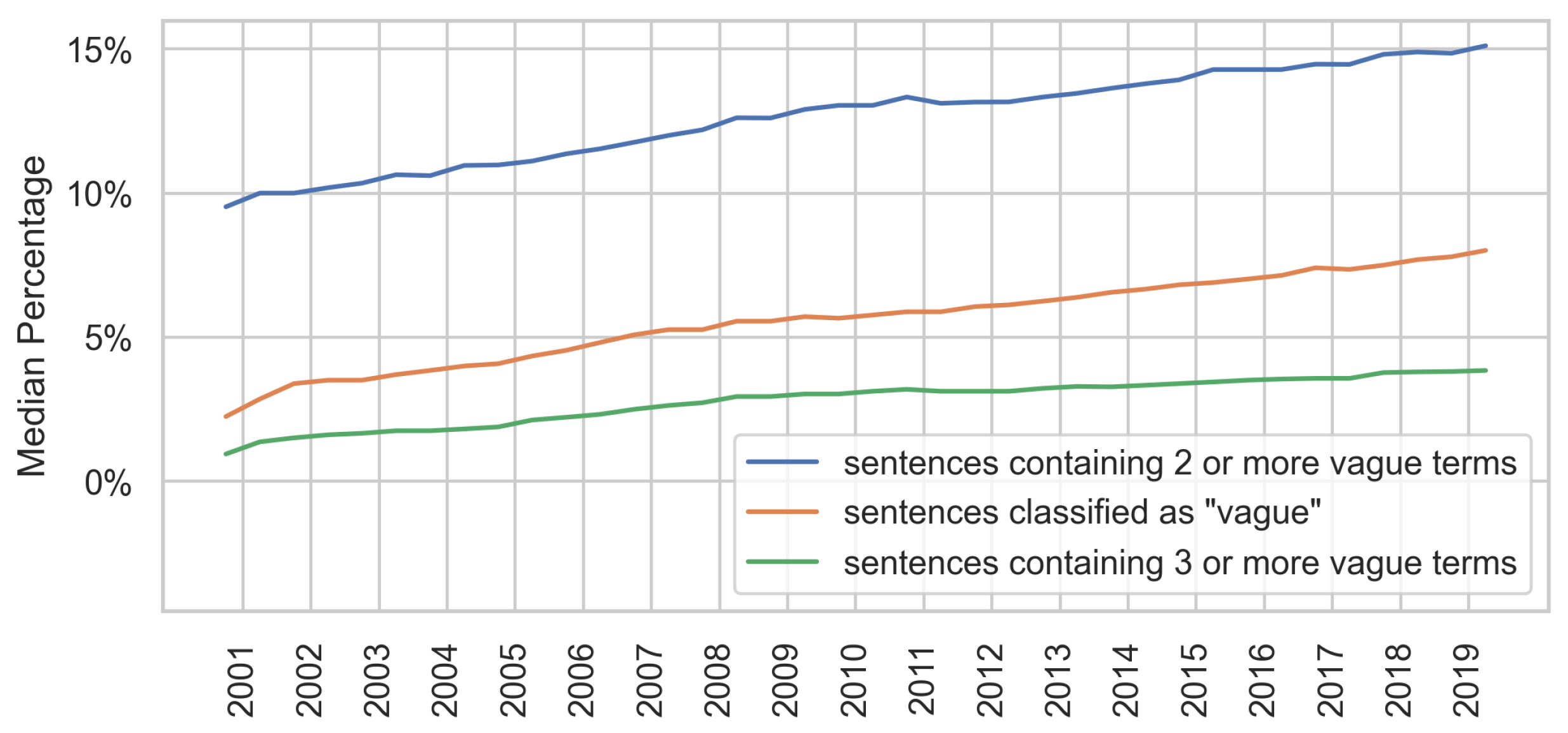

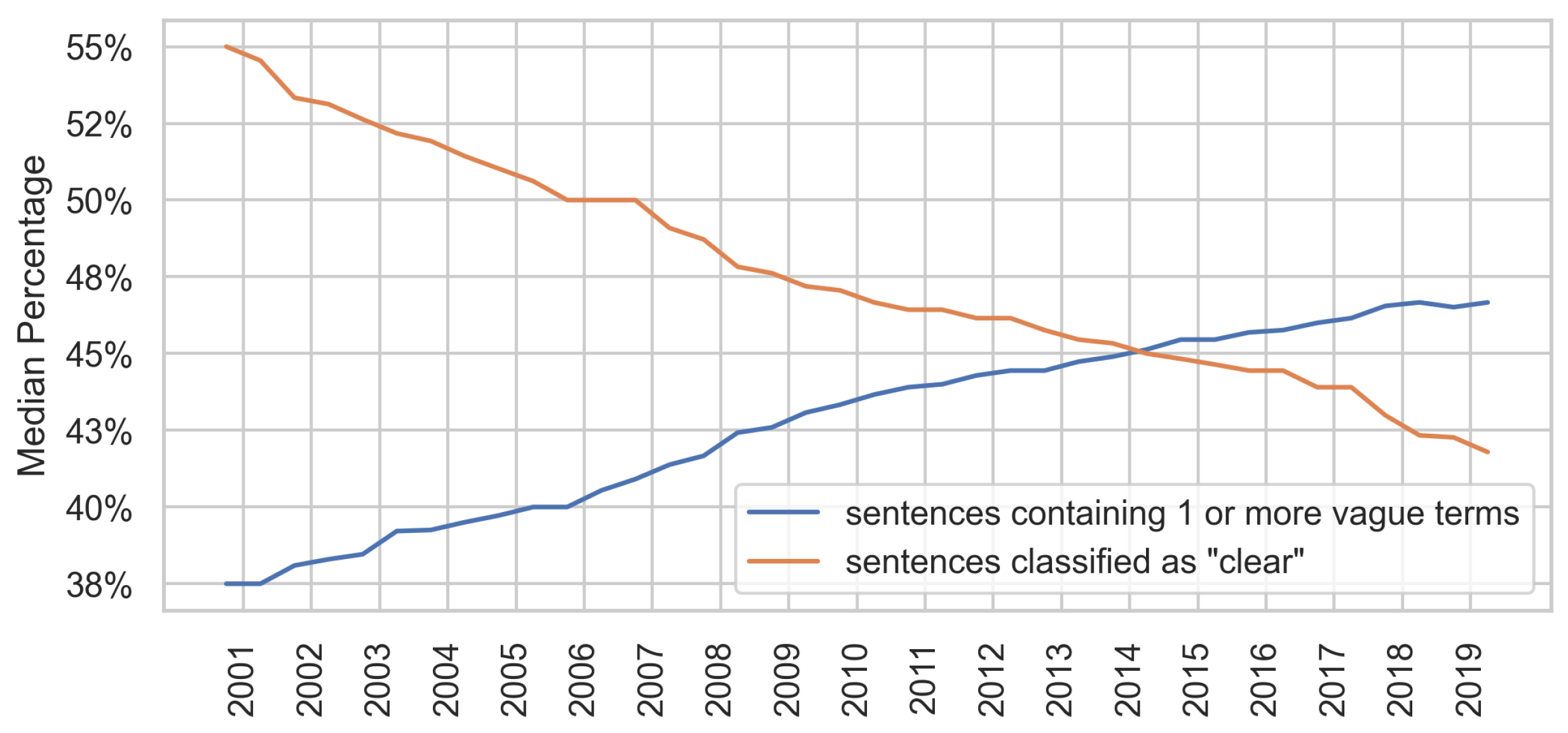

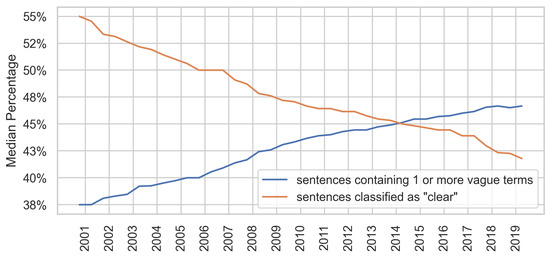

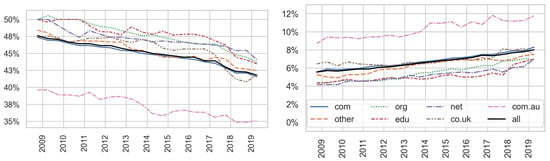

The results showed that the proportion of sentences containing vague terms increased (Figure 11 and Figure 12). The fraction of sentences containing at least one vague term rose constantly over time, from 38% in 2001 to 47% in 2019. On average, nearly every second sentence in a policy contained at least one vague term. The percentage of the sentences the model classified as vague also increased, while clear sentences decreased. Those findings paint a similar picture of the results of Srinath et al. [12] between the years 2019 and 2020.

Figure 11.

Median percentage of “vague” sentences in privacy policies.

Figure 12.

Median percentage of “vague” and “clear” sentences in privacy policies.

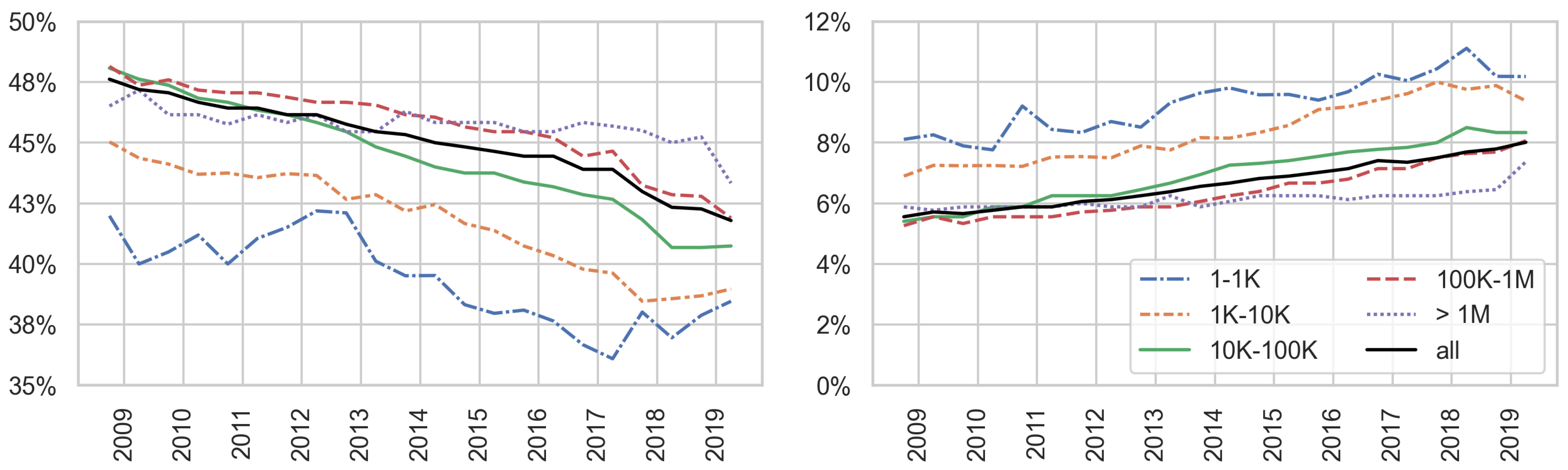

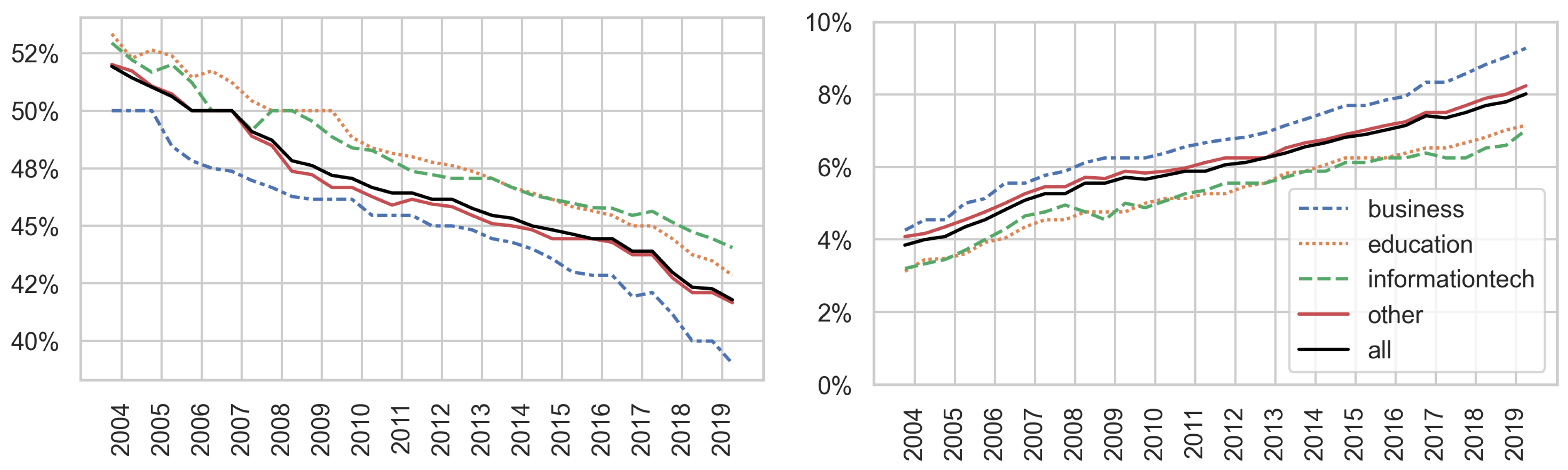

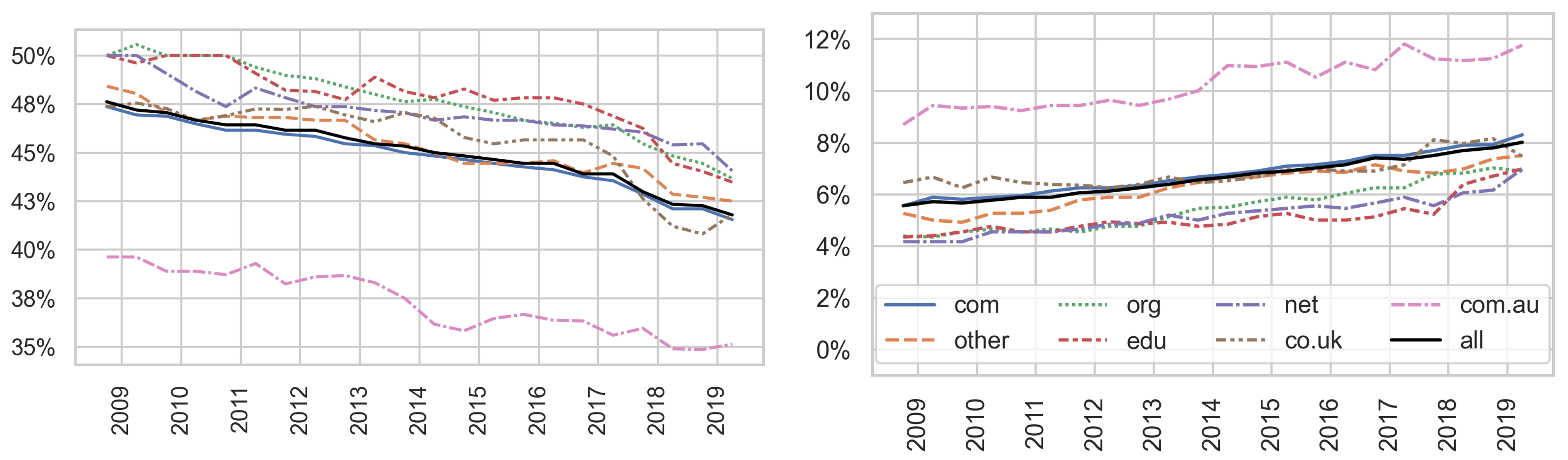

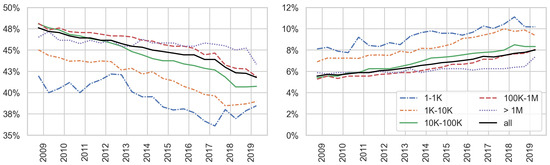

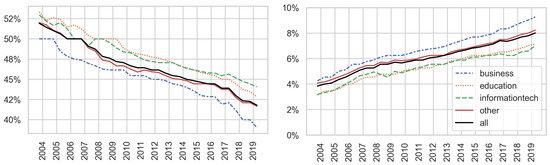

The results also confirm the assumption that privacy policies are becoming more ambiguous over time [7]. This trend holds for different website categories, top-level domain, and popularity ranks. Figure 13 illustrates that popular websites tend to have a higher number of vague and less clear sentences. The different categories of websites followed the overall trend of increasing policy ambiguity. However, for education and information technology websites, it was generally higher, while for business websites, it was lower. Nevertheless, those differences were not particularly large (Figure 14). It is noteworthy that the holders of Australian commercial websites (com.au domain) provided more ambiguous polices. The fraction of clear sentences in those policies was consistently around 8% lower than the median fraction for all websites (35% versus 42% in 2019). The opposite trend was visible the vague sentences, as can be seen in Figure 15.

Figure 13.

Median proportion of sentences classified as “clear” (left) and as “vague” (right) by Alexa rank.

Figure 14.

Median proportion of sentences classified as “clear” (left) and as “vague” (right) by website category.

Figure 15.

Median proportion of sentences classified as “clear” (left) and as “vague” (right) by top-level domain.

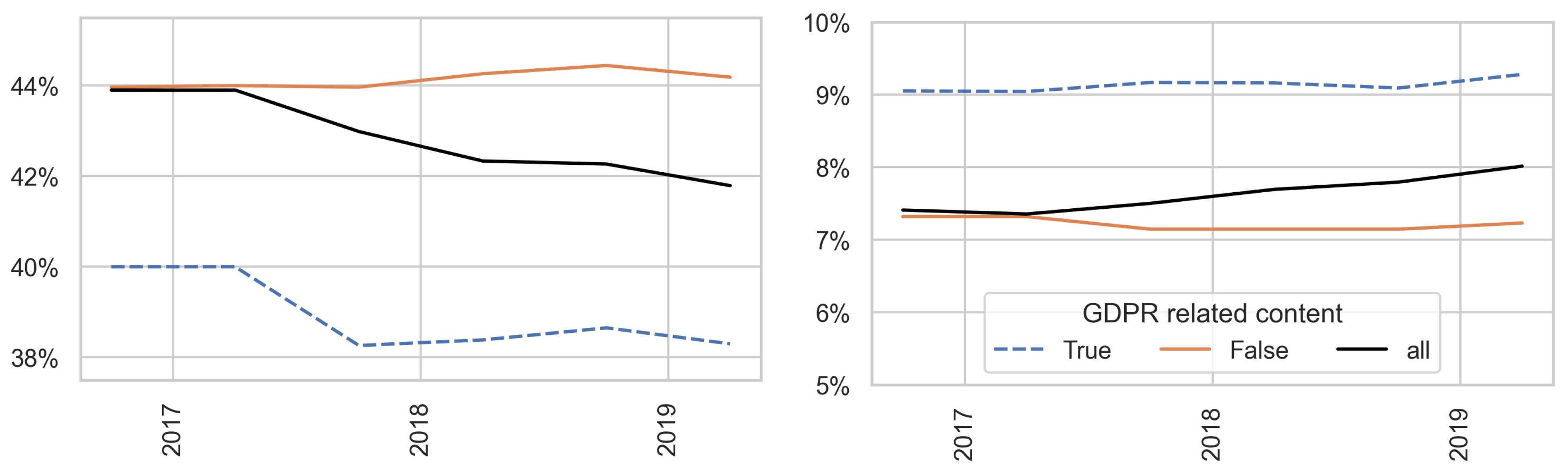

To analyze whether GDPR policies are ambiguous, Figure 16 shows the fraction of clear and vague sentences grouped by whether the policy contains some GDPR key terms or not. The results indicate that the GDPR policies have a lower fraction of clear sentences of about 2%. In contrast, the fraction of vague ones is higher.

Figure 16.

Median proportion of sentences classified as “clear” (left) and as “vague” (right) by GDPR content.

5.3. Positive Phrases

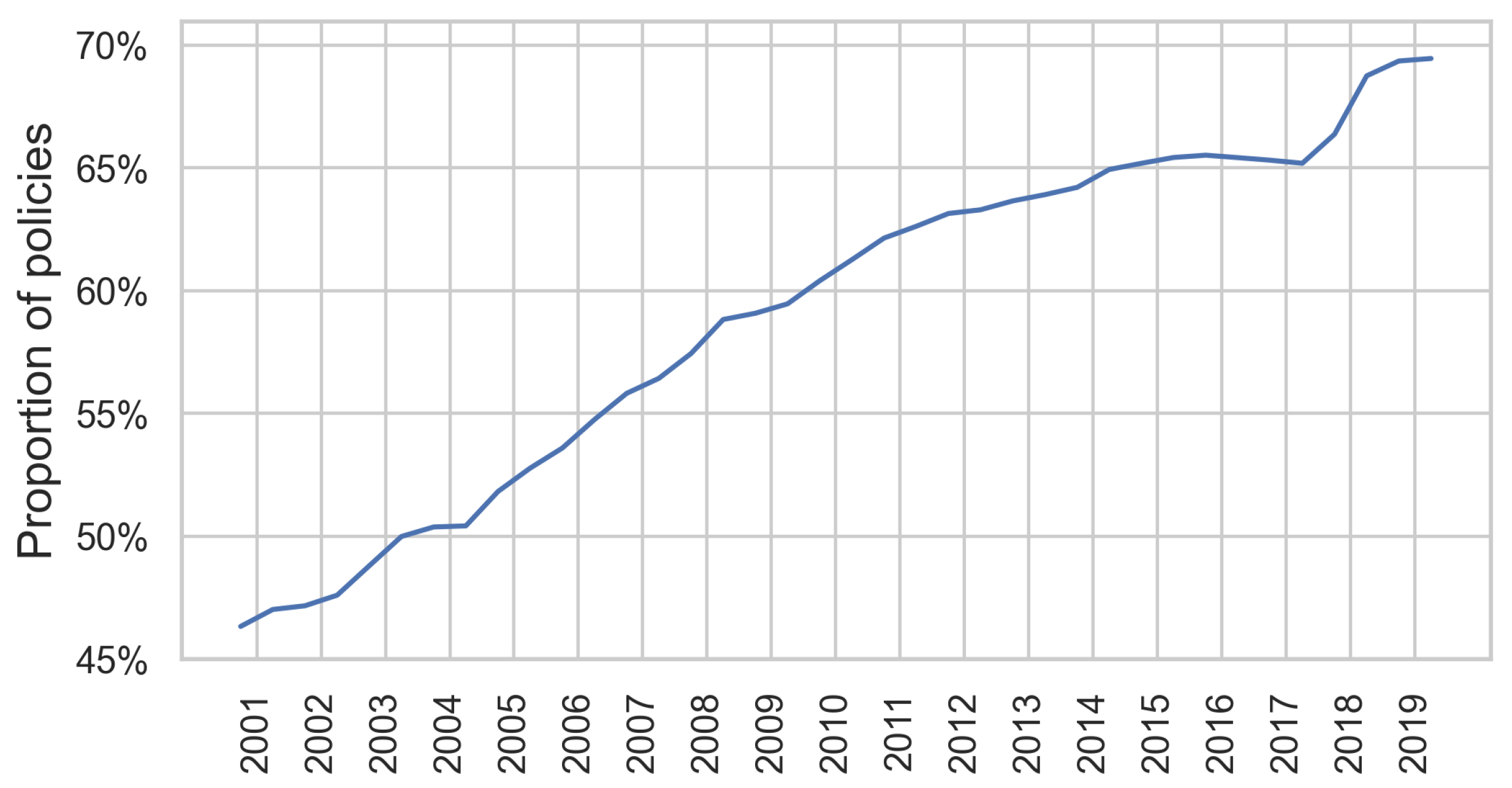

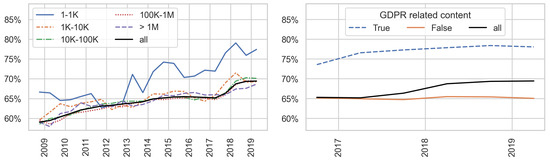

Figure 17 displays a large increase in policies using positive language. In 2019, two-thirds of privacy policies contained at least one of the listed phrases. This is more than double the result reported by Libert et al. [13] for the year 2021, which may be due to the fact that we added more words to the list of pacifying phrases. The findings indicated that the policies of the top 1000 websites more often contained such phrases than less popular websites (Figure 18-left). Furthermore, Figure 18-right shows that, in 2019, 78% percent of GDPR policies contained positive framing, whereas for the “non-GDPR” polices, this fraction was only 65%. Considering the top-level domain and website categories, this illustrated the fact that educational websites use those positive statements less often in their policies (Figure 19).

Figure 17.

The proportion of policies containing one or more pacifying phrases.

Figure 18.

Proportion of policies containing one or more pacifying phrases by Alexa ranking (left) and by GDPR content (right).

Figure 19.

Proportion of policies containing one or more pacifying phrases by top-level domain (left) and by website category (right).

6. Discussion

The longitudinal analysis of more than 900,000 policy snapshots showed a concerning picture of the privacy policy landscape. To begin with, these policies were shown to be long and difficult to read. Since 2001, the average policy length has doubled, and nearly half the policies in the dataset required a college degree. In the age of information overload, the increasing complexity of privacy policies forces Internet users into a “transparency paradox” [67]. Transparency requires the detailed explanations of all data practices and user rights, which might result in terms that are lengthy and difficult to understand. Alternatively, summarizations lead to more ambiguous notices. The policies an average user encounters on a daily basis are simply too extensive and too long. When faced with yet another one, users most simply click “accept” and hope for the best.

Moreover, policies mentioning the GDPR or related wording were double the length of “non-GDPR” ones. This result confirmed findings from previous studies, indicating that the rise in policy length in recent years is likely connected to the regulation. A possible explanation is that policies were required to add information on data sharing practices, users rights, contact information, and other areas. Furthermore, to ensure compliance with the new regulations, lawyers might have used more detailed and lengthy legal language. This contradicts the GDPR’s transparency guidelines, which require that websites avoid the need for users to scroll through large amounts of text, causing information fatigue. Furthermore, “the quality, accessibility, and comprehensibility of the information is as important as the actual content”.

The key finding of this study was that privacy policies have become more ambiguous over time. They are increasingly using vague terms; in 2019, on average, nearly every second sentence in a policy contained at least one vague term. The results of the language model showed that the fraction of vague statements in policies has increased over time, while clear statements have decreased. This is troubling because it indicates that the policies fail to clearly communicate websites’ actual practices. This in turn limits not only the ability of human readers to precisely interpret their contents, but also machines’ ability to “understand” them. Kotal et al. [57] found that NLP-based text segment classifiers are less accurate for policies that are more ambiguous.

The greatest lack of overall clarity, however, was found in the policies of popular websites—in other words, in those that accounted for a larger portion of web traffic. However, the bigger part of these policies contained pacifying statements. One possible explanation is that those websites are using user data in a greater variety of ways and require more exhaustive policies. It could also be that the popular sites are the only ones with the resources to afford teams of lawyers to write complex policy texts. There appears to be a lack of incentives to make privacy policies not only beneficial for their writers, but also useful for their readers. While companies “take your privacy very seriously”, they have failed to take the effective communication of data practices seriously enough.

The presented readability analysis focused on specific aspects such as sentence count for length, passive voice usage, and the Dale–Chall readability score. However, it has limitations as it does not encompass other factors that can influence the overall comprehension difficulty of the text. Policy features such as highlighting relevant information, the organization of the text, and formatting are equally important. One possible direction for research is the examination of the overall user-friendliness, including the question of whether policies are easily accessible and if they contain additional media such as videos or images. Furthermore, the use of specific legal jargon should be explored as it may make the text less understandable.

Concerning ambiguity, the frequency of vague terms in a text may indicate ambiguous content. Nevertheless, to achieve accurate results, it is important to study the context in which those words are used. The presented key terms can be used in a way that is not vague or in a context that is not relevant for the analysis, for example, in descriptions. One possibility for the future research is to identify sentences in which vague terms are used in tandem with relevant content, for example, data sharing practices (e.g., the co-occurrences of “may” and “share”).

As part of an additional measurement of ambiguity, a BERT model was trained. However, there are several limitations regarding the training data. First, the corpus is based on privacy policies from the year 2014. There is no evidence for whether the model trained with these data can be applied on policies from 2009 to 2019. The policy content or phrasing might change in the course of the time and this could distort the predictions. Second, with only 4500 sentences, the corpus is relatively small and very unbalanced. This makes it difficult to train accurate classifiers, especially regarding the “vague” category. A larger and more balanced annotated dataset is necessary to further improve the overall performance of the model. Third, annotations are made on a sentence basis. However, the context beyond the scope of the single sentence may be important for annotators to judge the clarity of the statements. Lastly, the concept of vagueness is a very subjective one and even human annotators often disagree. The underlying pattern may be too complex for a language model to accurately reproduce.

Furthermore, the relationship between GDPR policies and ambiguity should be investigated in future work to obtain more decisive results. Another open question is why the policies of Australian commercial websites (com.au) are on average longer and more ambiguous. This might be due the local legal framework or specific language characteristics of Australian English.

With respect to pacifying language, the heuristic approach of matching pacifying statements in privacy policies has revealed that their use is increasing. User studies and more complex NLP techniques such as sentiment analysis are needed to gain a deeper understanding of how policy authors influence the user’s perception of privacy risks.

Furthermore, recent advancements in NLP methodologies underscore the potential of large language models (LLMs) for the future analysis of privacy policies. Recent papers by Chanenson et al. [68] and Tang et al. [69] exemplify this potential.

7. Conclusions

The key finding of this study was that privacy policies have become more ambiguous over time. They are increasingly using vague terms; in 2019, on average, nearly every second sentence in a policy contained at least one vague term. The results of the language model showed that the fraction of vague statements in policies has increased over time, while clear statements have decreased. This is troubling because it indicates that the policies fail to clearly communicate the websites’ actual practices. This, in turn, limits not only the ability of human readers to precisely interpret their contents but also machines’ ability to “understand” them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B., T.E. and B.F.; methodology, V.B., T.E. and B.F.; software, V.B.; validation, V.B., T.E. and B.F.; formal analysis, V.B.; investigation, V.B.; resources, V.B.; data curation, V.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B.; writing—review and editing, V.B., T.E. and B.F.; visualization, V.B.; supervision, T.E. and B.F.; project administration, B.F.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The corpus of policies is available at https://github.com/citp/privacy-policy-historical (accessed on 15 November 2023). To get access to the data in the form of an SQL-database, send an email to privacy-policy-data@lists.cs.princeton.edu stating your name and affiliation. The dataset containing vague statements used for training the sentence classificator is available here: https://loganlebanoff.github.io/mydata (accessed on 15 November 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Website Categories and GDPR Content

Figure A1 illustrates the distribution of categories among websites. During the analysis phase, if a website was linked to multiple categories, including “business”, the last one was removed, leaving only the more descriptive categories. This enabled the better visualization of trends across categories.

Figure A1.

Website count per category. If no category information is available, the “uncategorized” bin applies.

Figure A1.

Website count per category. If no category information is available, the “uncategorized” bin applies.

Figure A2.

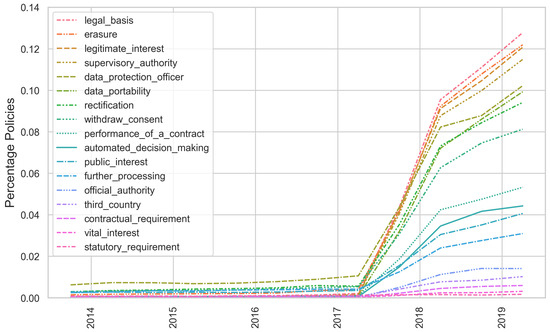

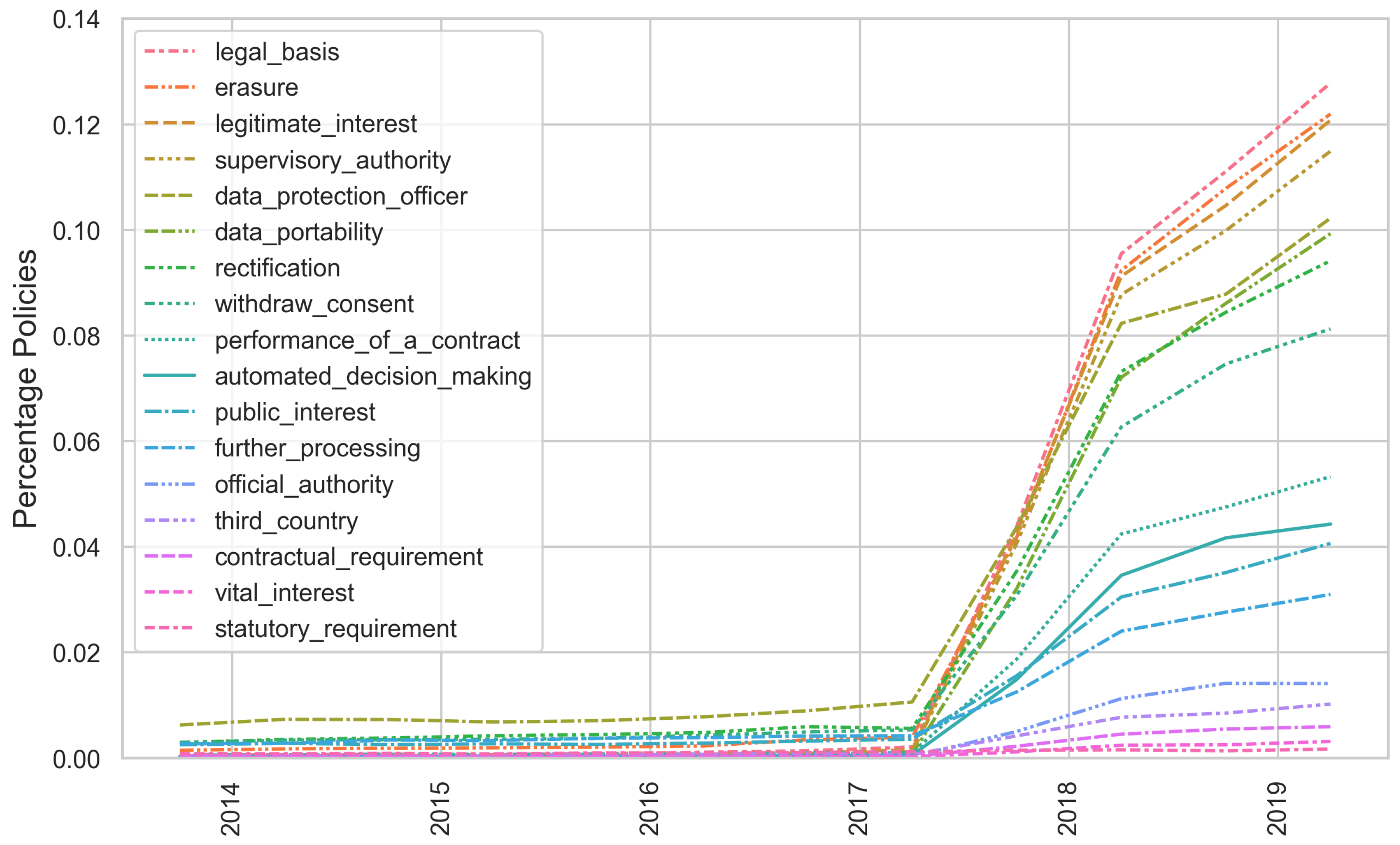

Usage of phrases specific to the GDPR (selection based on Amos et al. [7]).

Figure A2.

Usage of phrases specific to the GDPR (selection based on Amos et al. [7]).

The data repository by Amos et al. [7] contains a list of potential keywords that are frequently used with GDPR policies, a subset of which is shown in Figure A2. Also inspired by a similar approach, namely that of Degeling et al. [53], and further testing, the final set of phrases we selected are: legal basis, erasure, legitimate interest, supervisory authority, data portability, performance of a contract, automated decision making, public interest, further processing, and withdraw consent.

Figure A3.

Distribution of GDPR and non-GDPR policies per interval.

Figure A3.

Distribution of GDPR and non-GDPR policies per interval.

Appendix B. Outlier Analysis

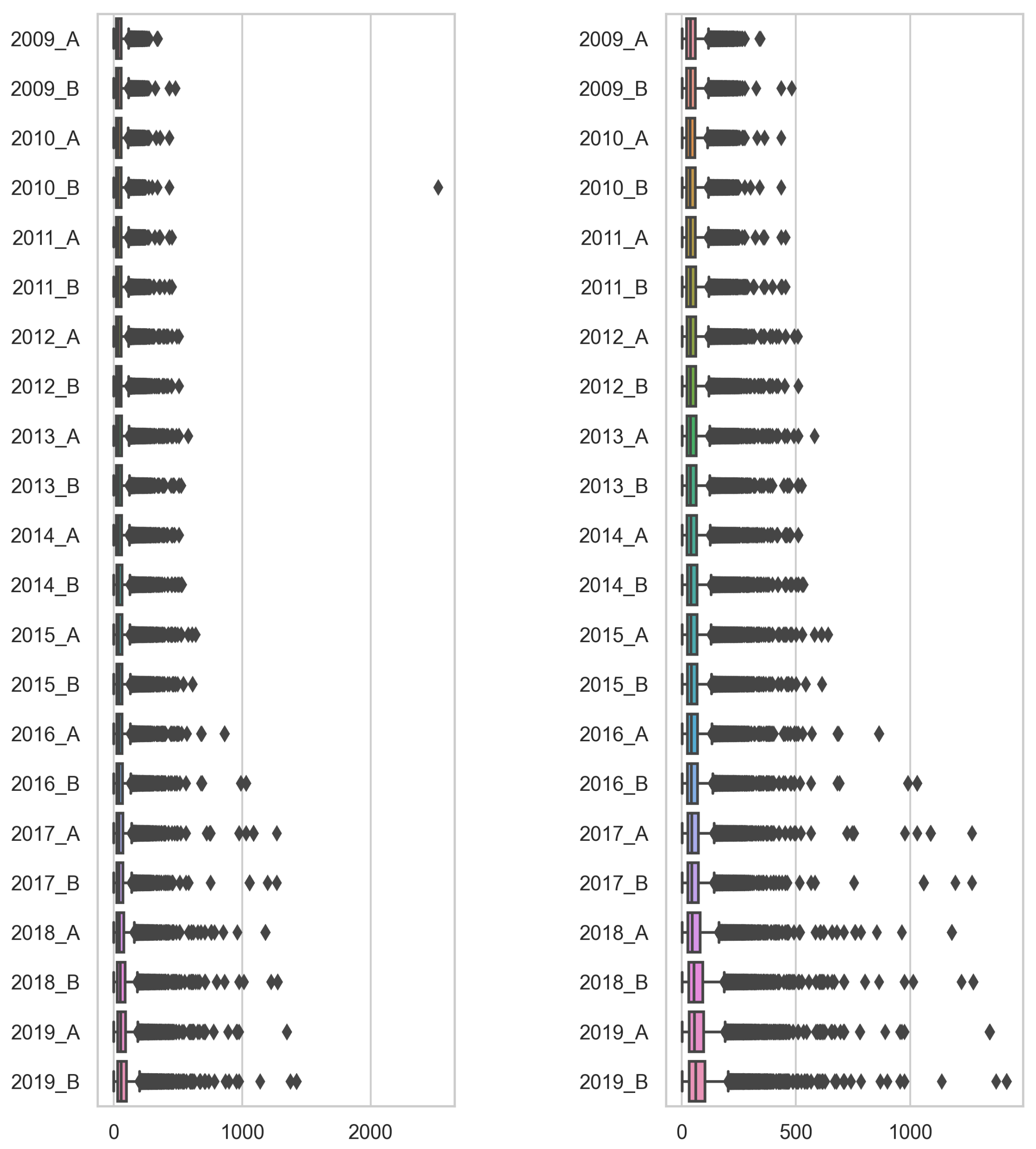

Appendix B.1. Policy Length

The outlier analysis pointed out one unusually long policy. This policy contained 25 times the same text and it was manually adjusted to its regular length.

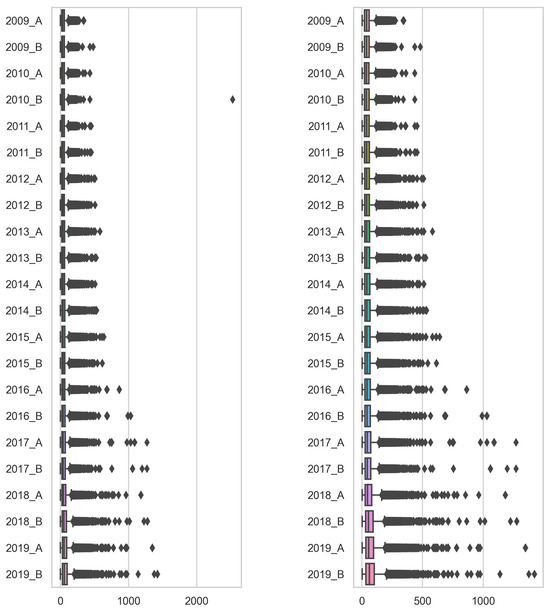

Figure A4.

Sentence count distribution: original (left) and after cleaning (right).

Figure A4.

Sentence count distribution: original (left) and after cleaning (right).

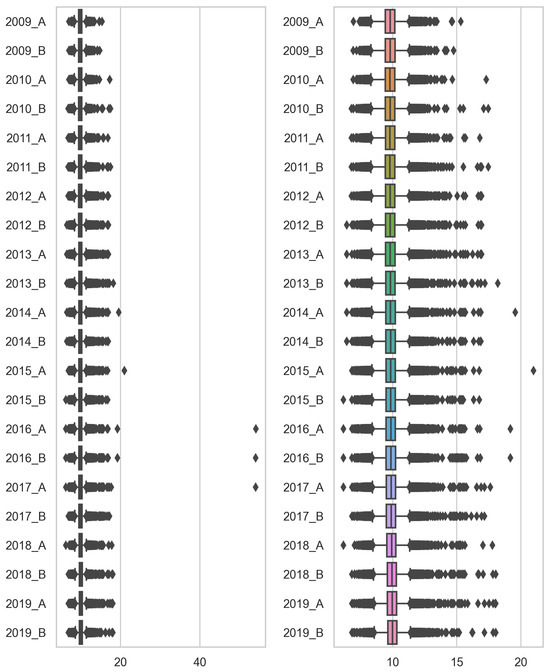

Appendix B.2. Readability Score

A manual check showed that the content of three policies that scored unusually high on the Dale–Chall test is not valid and those policies had to be removed.

Figure A5.

Dale–Chall score distribution: (left) and after cleaning (right).

Figure A5.

Dale–Chall score distribution: (left) and after cleaning (right).

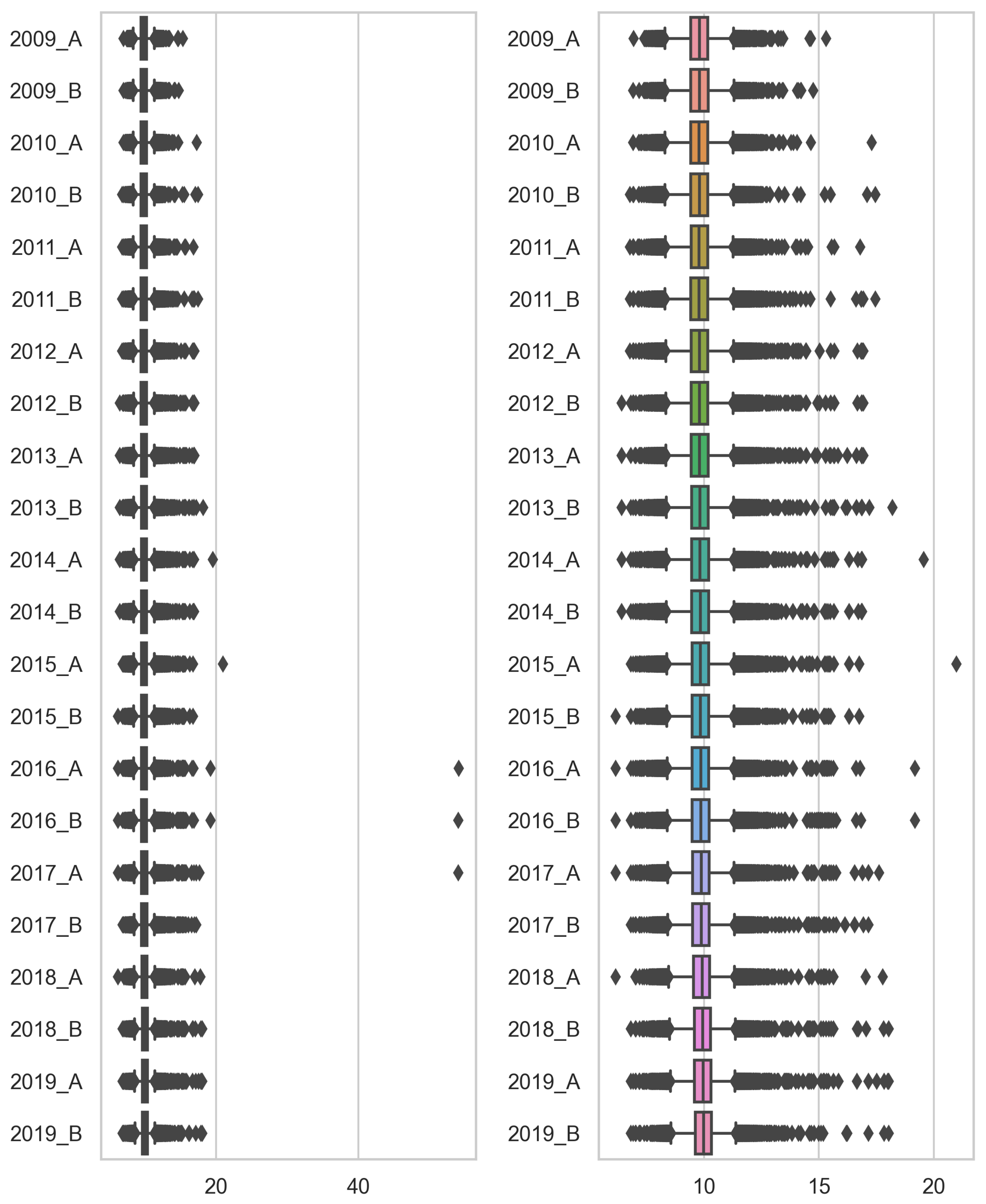

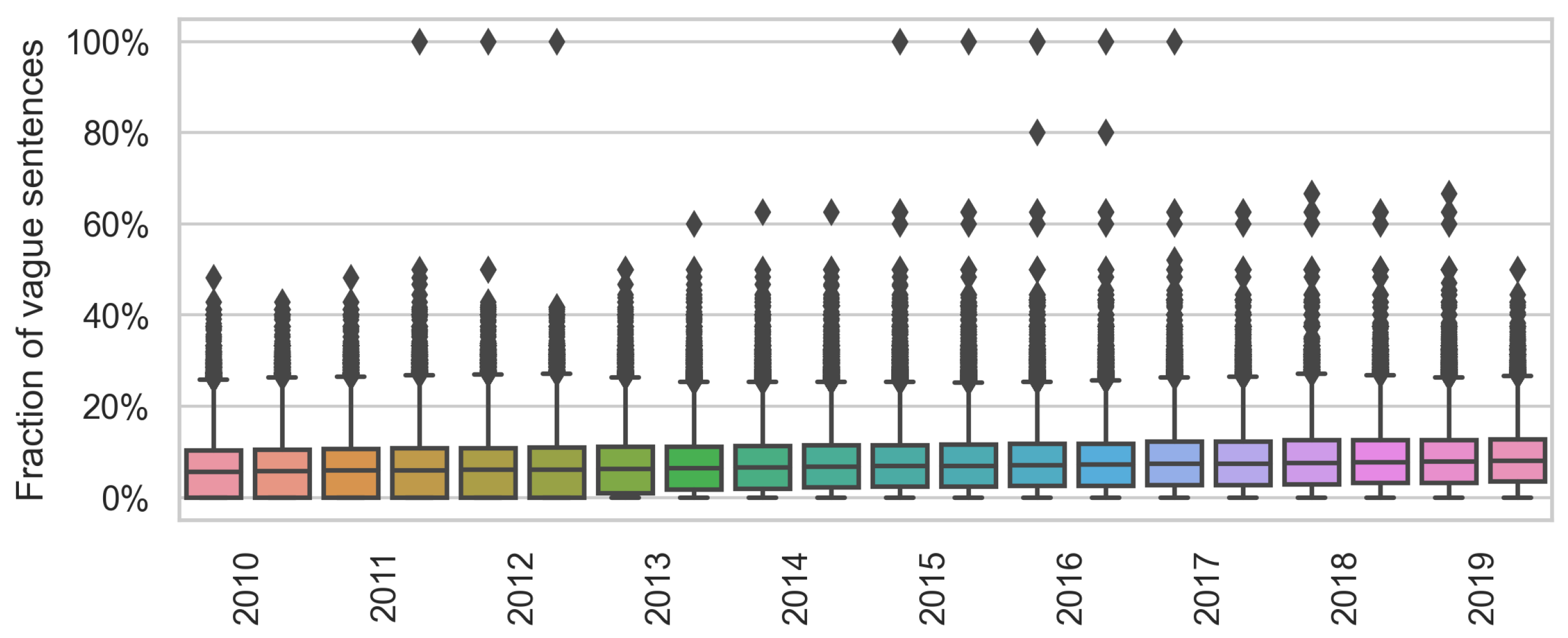

Appendix B.3. Vague Sentences

Some policies contain almost no vague sentences and some only contain vague sentences. The manual evaluation of the policies in the two extremes of the distribution showed that most of them are very short, but they are valid and remained in the corpus.

Figure A6.

Vagueness score distribution.

Figure A6.

Vagueness score distribution.

Appendix C. Model Performance

Figure A7.

BERT performance evaluation: confusion matrix (stronger color indicates higher numbers).

Figure A7.

BERT performance evaluation: confusion matrix (stronger color indicates higher numbers).

Figure A8.

BERT performance evaluation: ROC curves.

Figure A8.

BERT performance evaluation: ROC curves.

Appendix D. Positive Phrasing

Table A1.

Positive phrases identified in privacy policies.

Table A1.

Positive phrases identified in privacy policies.

| we value | transparency | protect your (personal) information |

| we respect | trust us | protect your (personal) data |

| we promise | safe and secure | protect your privacy |

| care about | committed to protecting | provides protection |

| with care | committed to safeguarding | serious about your privacy |

| responsibly | committed to respecting | takes your security (very) seriously |

| important to us | respect your privacy | takes your privacy (very) seriously |

References

- Meier, Y.; Schäwel, J.; Krämer, N. The Shorter the Better? Effects of Privacy Policy Length on Online Privacy Decision-Making. Media Commun. 2020, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibdah, D.; Lachtar, N.; Raparthi, S.M.; Bacha, A. “Why Should I Read the Privacy Policy, I Just Need the Service”: A Study on Attitudes and Perceptions Toward Privacy Policies. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 166465–166487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakova, T.; Krasnova, H.; Fabian, B. Exploring the Impact of Readability of Privacy Policies on Users’ Trust. In Proceedings of the 24th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS 2016), Istanbul, Turkey, 12–15 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, I. Privacy Policies Across the Ages: Content and Readability of Privacy Policies 1996–2021. Technical Report. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.08739. [Google Scholar]

- Article 29 Working Party: Guidelines on Transparency under Regulation 2016/679. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/article29/items/622227/en (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Reidenberg, J.R.; Bhatia, J.; Breaux, T.; Norton, T. Ambiguity in Privacy Policies and the Impact of Regulation; SSRN Scholarly; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, R.; Acar, G.; Lucherini, E.; Kshirsagar, M.; Narayanan, A.; Mayer, J. Privacy Policies over Time: Curation and Analysis of a Million-Document Dataset. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 2165–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, J.; Breaux, T.D.; Reidenberg, J.R.; Norton, T.B. A Theory of Vagueness and Privacy Risk Perception. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 24th International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE), Beijing, China, 12–16 September 2016; pp. 26–35, ISSN 2332-6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, B.; Ermakova, T.; Lentz, T. Large-scale readability analysis of privacy policies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Intelligence (WI ’17), Leipzig, Germany, 23–26 August 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakova, T.; Fabian, B.; Babina, E. Readability of Privacy Policies of Healthcare Websites. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik, Osnabrück, Germany, 4–6 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, J.; Dara, R.A.; Obimbo, C.; Song, F.; Menard, K. A comprehensive keyword analysis of online privacy policies. Inf. Secur. J. Glob. Perspect. 2018, 27, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinath, M.; Sundareswara, S.N.; Giles, C.L.; Wilson, S. PrivaSeer: A Privacy Policy Search Engine. In Proceedings of the Web Engineering; Brambilla, M., Chbeir, R., Frasincar, F., Manolescu, I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libert, T.; Desai, A.; Patel, D. Preserving Needles in the Haystack: A Search Engine and Multi-Jurisdictional Forensic Documentation System for Privacy Violations on the Web. 2021. Available online: https://timlibert.me/pdf/Libert_et_al-2021-Forensic_Privacy_on_Web.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Lebanoff, L.; Liu, F. Automatic Detection of Vague Words and Sentences in Privacy Policies. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Association for Computational Linguistics, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018; pp. 3508–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data, Movement of Such. Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data. Off. J. L 1995, 281, 0031–0050. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, N.; Graux, H.; Botterman, M.; Valeri, L. Review of the European Data Protection Directive; Technical report; RAND Corporation: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- GDPR-Personal Data. Available online: https://gdpr-info.eu/issues/personal-data/ (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Federal Trade Comission, Privacy Online: A Report to Congress. Federal Trade Commission, 1998. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/privacy-online-report-congress/priv-23a.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Usable Privacy Policy Project. Available online: https://usableprivacy.org/ (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Wilson, S.; Schaub, F.; Dara, A.A.; Liu, F.; Cherivirala, S.; Giovanni Leon, P.; Schaarup Andersen, M.; Zimmeck, S.; Sathyendra, K.M.; Russell, N.C.; et al. The Creation and Analysis of a Website Privacy Policy Corpus. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; Association for Computational Linguistics: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 1330–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannihatti Kumar, V.; Iyengar, R.; Nisal, N.; Feng, Y.; Habib, H.; Story, P.; Cherivirala, S.; Hagan, M.; Cranor, L.; Wilson, S.; et al. Finding a Choice in a Haystack: Automatic Extraction of Opt-Out Statements from Privacy Policy Text. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2020, Virtural, 20–24 April 2020; ACM: Taipei, Taiwan, 2020; pp. 1943–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.U.; Chi, J.; Le, T.; Norton, T.; Tian, Y.; Chang, K.W. Intent Classification and Slot Filling for Privacy Policies. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.00123. [Google Scholar]

- Nokhbeh Zaeem, R.; Barber, K.S. A Large Publicly Available Corpus of Website Privacy Policies Based on DMOZ. In Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, Virtual, 26–28 April 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audich, D.; Dara, R.; Nonnecke, B. Privacy Policy Annotation for Semi-Automated Analysis: A Cost-Effective Approach. In Trust Management XII. IFIPTM 2018. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.B.; Ravichander, A.; Story, P.; Sadeh, N. Quantifying the Effect of In-Domain Distributed Word Representations: A Study of Privacy Policies. In AAAI Spring Symposium on Privacy-Enhancing Artificial Intelligence and Language Technologies. 2019. Available online: https://usableprivacy.org/static/files/kumar_pal_2019.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Liu, F.; Wilson, S.; Story, P.; Zimmeck, S.; Sadeh, N. Towards Automatic Classification of Privacy Policy Text. Technical Report, CMU-ISR-17-118R, Institute for Software Research and Language Technologies Institute, School of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University, 2018. Available online: http://reports-archive.adm.cs.cmu.edu/anon/isr2017/CMU-ISR-17-118R.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Mousavi, N.; Jabat, P.; Nedelchev, R.; Scerri, S.; Graux, D. Establishing a Strong Baseline for Privacy Policy Classification. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Conference on ICT Systems Security and Privacy Protection, Maribor, Slovenia, 21–23 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mustapha, M.; Krasnashchok, K.; Al Bassit, A.; Skhiri, S. Privacy Policy Classification with XLNet (Short Paper). In Data Privacy Management, Cryptocurrencies and Blockchain Technology; Garcia-Alfaro, J., Navarro-Arribas, G., Herrera-Joancomarti, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12484, pp. 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.; Shin, K.G.; Choi, J.M.; Shin, J. Automated Extraction and Presentation of Data Practices in Privacy Policies. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2021, 2021, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabduljabbar, A.; Abusnaina, A.; Meteriz-Yildiran, U.; Mohaisen, D. Automated Privacy Policy Annotation with Information Highlighting Made Practical Using Deep Representations. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Virtual, 15–19 November 2021; CCS ’21. Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 2378–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabduljabbar, A.; Abusnaina, A.; Meteriz-Yildiran, U.; Mohaisen, D. TLDR: Deep Learning-Based Automated Privacy Policy Annotation with Key Policy Highlights. In Proceedings of the 20th Workshop on Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society, Virtual, 15 November 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyendra, K.M.; Schaub, F.; Wilson, S.; Sadeh, N.M. Automatic Extraction of Opt-Out Choices from Privacy Policies. In AAAI Fall Symposia, 2016, Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence. 2016. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:32896562 (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Sathyendra, K.M.; Wilson, S.; Schaub, F.; Zimmeck, S.; Sadeh, N. Identifying the Provision of Choices in Privacy Policy Text. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 7–11 September 2017; Association for Computational Linguistics: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017; pp. 2774–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keymanesh, M.; Elsner, M.; Parthasarathy, S. Toward Domain-Guided Controllable Summarization of Privacy Policies. In Proceedings of the 2020 Natural Legal Language Processing (NLLP) Workshop, Virtual Event/San Diego, CA, USA, 24 August 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ravichander, A.; Black, A.W.; Wilson, S.; Norton, T.; Sadeh, N. Question Answering for Privacy Policies: Combining Computational and Legal Perspectives. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.00841. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, W.U.; Chi, J.; Tian, Y.; Chang, K.W. PolicyQA: A Reading Comprehension Dataset for Privacy Policies. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.02557. [Google Scholar]

- Keymanesh, M.; Elsner, M.; Parthasarathy, S. Privacy Policy Question Answering Assistant: A Query-Guided Extractive Summarization Approach. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.14638. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, A.; Waldis, A.; Bless, C.; Andueza Rodriguez, M.; Mazzola, L. PrivacyGLUE: A Benchmark Dataset for General Language Understanding in Privacy Policies. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, W.B.; Hofmann, P.; Nakamura, T.; Kiyomoto, S.; Serna, J. PrivacyGuide: Towards an Implementation of the EU GDPR on Internet Privacy Policy Evaluation. In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM International Workshop on Security and Privacy Analytics, Tempe, AZ, USA, 19–21 March 2018; IWSPA ’18. Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkous, H.; Fawaz, K.; Lebret, R.; Schaub, F.; Shin, K.G.; Aberer, K. Polisis: Automated Analysis and Presentation of Privacy Policies Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 27th USENIX Security Symposium, Baltimore, MD, USA, 15–17 August 2018; USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 531–548. [Google Scholar]

- PriBOT. Available online: https://pribot.org/ (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Zaeem, R.N.; German, R.L.; Barber, K.S. PrivacyCheck: Automatic Summarization of Privacy Policies Using Data Mining. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2018, 18, 53:1–53:18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokhbeh Zaeem, R.; Anya, S.; Issa, A.; Nimergood, J.; Rogers, I.; Shah, V.; Srivastava, A.; Barber, K.S. PrivacyCheck v2: A Tool that Recaps Privacy Policies for You. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual, 19–23 October 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020. CIKM ’20. pp. 3441–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokhbeh Zaeem, R.; Ahbab, A.; Bestor, J.; Djadi, H.H.; Kharel, S.; Lai, V.; Wang, N.; Barber, K.S. PrivacyCheck v3: Empowering Users with Higher-Level Understanding of Privacy Policies. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Virtual, 21–25 February 2022; WSDM ’22. Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1593–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privacy Lab|Center for Identity. Available online: https://identity.utexas.edu/privacy-lab (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Opt-Out Easy. Available online: https://optouteasy.isr.cmu.edu/ (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Contissa, G.; Docter, K.; Lagioia, F.; Lippi, M.; Micklitz, H.W.; Pałka, P.; Sartor, G.; Torroni, P. Claudette Meets GDPR: Automating the Evaluation of Privacy Policies Using Artificial Intelligence; SSRN Scholarly; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepina, R.; Contissa, G.; Drazewski, K.; Lagioia, F.; Lippi, M.; Micklitz, H.; Palka, P.; Sartor, G.; Torroni, P. GDPR Privacy Policies in CLAUDETTE: Challenges of Omission, Context and Multilingualism. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Automated Semantic Analysis of Information in Legal Text (ASAIL 2019), Montreal, QC, Canada, 21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, N.; Scerri, S.; Lehmann, J. KnIGHT: Mapping Privacy Policies to GDPR. In Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management; Faron Zucker, C., Ghidini, C., Napoli, A., Toussaint, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11313, pp. 258–272. [Google Scholar]

- Cejas, O.A.; Abualhaija, S.; Torre, D.; Sabetzadeh, M.; Briand, L. AI-enabled Automation for Completeness Checking of Privacy Policies. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2021, 48, 4647–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, A.; Javed, T.; Beg, M.O. Detecting Compliance of Privacy Policies with Data Protection Laws. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.12362. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, D.; Viejo, A.; Batet, M. Automatic Assessment of Privacy Policies under the GDPR. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeling, M.; Utz, C.; Lentzsch, C.; Hosseini, H.; Schaub, F.; Holz, T. We Value Your Privacy … Now Take Some Cookies: Measuring the GDPR’s Impact on Web Privacy. In Proceedings of the 2019 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 24–27 February 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, T.; Khandelwal, R.; Harkous, H.; Fawaz, K. The Privacy Policy Landscape After the GDPR. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1809.08396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaeem, R.N.; Barber, K.S. The Effect of the GDPR on Privacy Policies: Recent Progress and Future Promise. ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2020, 12, 2:1–2:20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libert, T. An Automated Approach to Auditing Disclosure of Third-Party Data Collection in Website Privacy Policies. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference on World Wide Web-WWW ’18, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotal, A.; Joshi, A.; Pande Joshi, K. The Effect of Text Ambiguity on creating Policy Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Intl Conf on Parallel & Distributed Processing with Applications, Big Data & Cloud Computing, Sustainable Computing & Communications, Social Computing & Networking (ISPA/BDCloud/SocialCom/SustainCom), New York City, NY, USA, 30 September–3 October 2021; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmeck, S.; Story, P.; Smullen, D.; Ravichander, A.; Wang, Z.; Reidenberg, J.; Cameron Russell, N.; Sadeh, N. MAPS: Scaling Privacy Compliance Analysis to a Million Apps. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2019, 2019, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, P.; Zimmeck, S.; Ravichander, A.; Smullen, D.; Wang, Z.; Reidenberg, J.; Russell, N.; Sadeh, N. Natural Language Processing for Mobile App Privacy Compliance. In Proceedings of the PAL: Privacy-Enhancing Artificial Intelligence and Language Technologies AAAI Spring Symposium, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 25–27 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, S.S.; Waheed, N.; Tangari, G.; Ikram, M.; Smith, S. Longitudinal Compliance Analysis of Android Applications with Privacy Policies. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.10035. [Google Scholar]

- Internet Archive: Wayback Machine. Available online: https://archive.org/web/ (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- NLTK: nltk.tokenize Package. Available online: https://www.nltk.org/api/nltk.tokenize.html (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Webshrinker. Available online: https://webshrinker.com/ (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Chall, J.S.; Dale, E. Readability Revisited: The New Dale-Chall Readability Formula; Brookline Books: Brookline, MA, USA, 1995; Google-Books-ID: 2nbuAAAAMAAJ. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M.; et al. HuggingFace’s Transformers: State-of-the-art Natural Language Processing. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1910.03771. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Nissenbaum, H. A Contextual Approach to Privacy Online. Daedalus 2011, 140, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanenson, J.; Pickering, M.; Apthorpe, N. Automating Governing Knowledge Commons and Contextual Integrity (GKC-CI) Privacy Policy Annotations with Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:cs.CY/2311.02192. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; Liu, Z.; Ma, C.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhu, D.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; et al. PolicyGPT: Automated Analysis of Privacy Policies with Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:cs.CL/2309.10238. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).