Abstract

Current state-of-the-art neural machine translation (NMT) architectures usually do not take document-level context into account. However, the document-level context of a source sentence to be translated could encode valuable information to guide the MT model to generate a better translation. In recent times, MT researchers have turned their focus to this line of MT research. As an example, hierarchical attention network (HAN) models use document-level context for translation prediction. In this work, we studied translations produced by the HAN-based MT systems. We examined how contextual information improves translation in document-level NMT. More specifically, we investigated why context-aware models such as HAN perform better than vanilla baseline NMT systems that do not take context into account. We considered Hindi-to-English, Spanish-to-English and Chinese-to-English for our investigation. We experimented with the formation of conditional context (i.e., neighbouring sentences) of the source sentences to be translated in HAN to predict their target translations. Interestingly, we observed that the quality of the target translations of specific source sentences highly relates to the context in which the source sentences appear. Based on their sensitivity to context, we classify our test set sentences into three categories, i.e., context-sensitive, context-insensitive and normal. We believe that this categorization may change the way in which context is utilized in document-level translation.

1. Introduction

NMT [1,2,3] is the mainstream method in MT research and development today. Interestingly, current state-of-the-art NMT systems (e.g., [3]) do not make use of context in which a source sentence to be translated appears. In other words, translation is performed in isolation while completely ignoring the remaining content of the document to which the source sentence belongs.

However, translation should not be performed in isolation as in many cases the semantics of a source sentence can only be decoded by looking at the specific context of the document. Human translators work in CAT tools where the sentence to be translated appears in the context of the surrounding sentences. In recent years, there have been a number of approaches that have tried to incorporate document-level context into state-of-the-art NMT models [4,5,6,7]. All this work demonstrated that the use of document-level context can positively impact the quality of translation in NMT.

In this work, we used HAN [6], a document-level NMT model, to see how (document-level) context of a source sentence to be translated can impact translation quality. HAN is a context-aware NMT architecture that models the preceding context of a source sentence in a document for translation, and significantly outperforms NMT models that do not make use of document-level context. In this work, we investigated why context-aware models like HAN perform better than vanilla baseline NMT systems that do not take context into account. We considered three different morphologically distant language-pairs for our investigation: Hindi-to-English, Spanish-to-English and Chinese-to-English. We summarize the main contributions of this paper as follows:

- It is a well-accepted belief that context (neighbouring sentences) in which a sentence appears would help to improve the quality of its translation, and document-level MT models are built based on this principle. We show how exactly context impacts translation quality in state-of-the-art document-level NMT systems.

- For our investigation we chose a state-of-the-art document-level neural MT model (i.e., HAN) and three different morphologically distant language-pairs, experimented with the formation of context, and performed a comprehensive analysis on translations. Our research demonstrates that discourse information is not always useful in document-level NMT.

- As far as document-level MT is concerned, our research provides a number of recommendations regarding the nature of context that can be useful in document-level MT.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, work related to our study is discussed. Section 3 details the data we utilized for our experiments. Our NMT models are discussed in detail in Section 4. We discuss our evaluation strategy and results in Section 5 and Section 6, respectively. Finally, Section 7 concludes our work by discussing avenues for future work.

2. Related Work

In recent years, there has been remarkable progress in NMT to the point where some researchers [8] have started to claim that translations by NMT systems of specific domains are on par with human translation. Nevertheless, such evaluations were generally performed at sentence-level [1,3], and document-level context was ignored in the evaluation task. Analogous to how human translators work, it should be the case that consideration of document-level context [9,10] will help in resolving ambiguities and inconsistencies in MT. There has been a growing interest in modeling document-level context in NMT. As far as this direction of MT research is concerned, most of the studies aimed at improving translation quality by exploiting document-level context. For example, refs. [5,6,7,11,12,13,14,15,16] have demonstrated that context helps in improving the translation including various linguistic phenomena such as anaphoric pronoun resolution and lexical cohesion.

Wang et al. [4] proposed the idea of utilizing a context-aware MT architecture. Their architecture used a hierarchical recurrent neural network (RNN) on top of the encoder and decoder networks to summarize the context (previous n sentences) of a source sentence to be translated. The summarized vector was then used to initialize the decoder, either directly or after going through a gate, or as an auxiliary input to the decoder state. They conducted experiments on large scale Chinese-to-English data and the outcome from those experiments clearly illustrates the significance of context in improving translation quality.

Tiedemann and Scherrer et al. [11] utilized an RNN-based MT model to investigate document-level MT. In their case, the context window was fixed to the preceding sentence and applied on a combination of both source and target sides. This was accomplished by extending both the source and target sentences to include the previous sentence as the context. Their experiments showed marginal improvements in translation quality.

Bawden et al. [12] utilized multi-encoder NMT models that leverage context from the previous source sentence and combine the knowledge from the context and the source sentence. Their approach also involves a method that uses multiple encoders on the source side in order to decode the previous and current target sentences together. Despite the fact that they reported lower BLEU [17] scores when considering the target-side context, they showed its significance by evaluating test sets for cohesion, co-reference, and coherence.

Maruf and Haffari et al. [5] proposed a document-level NMT architecture that used memory networks, a type of neural network that uses external memories to keep track of global context. The architecture used two memory components to consider context for both source and target sides. Experimental results show the success of their approach in exploiting the document context.

Voita et al. [7] considered the Transformer architecture [3] for investigating document-level MT, which they modified by injecting document-level context. They used an additional encoder (i.e., a context-based encoder) whose output is concatenated with the output of the source sentence-based encoder of the Transformer. The authors considered a single sentence as the context for translation, be it preceding or succeeding. They reported improvements in translation quality when the previous sentence was used as context, but their model could not outperform the baseline when the following sentence was used as the context.

Tan et al. [15] proposed a hierarchical model that utilizes both local and global contexts. Their approach uses a sentence encoder to capture local dependency and a document encoder to capture global dependency. The hierarchical architecture propagates the context to each word to minimize mistranslations and to achieve context-specific translations. Their experiments showed significant improvements in document-level translation quality for benchmark corpora over strong baselines.

Unlike most approaches to document-level MT that utilize dual-encoder structures, Ma et al. [18] proposed a Transformer model that utilizes a flat structure with a unified encoder. In this model, the attention focuses on both local and global context by splitting the encoder into two parts. Their experiments demonstrate significant improvements in translation quality on two datasets by using a flat Transformer over both the uni-encoder and dual-encoder architectures.

Zhang et al. [13] proposed a new document-level architecture called Multi-Hop Transformer. Their approach involves iteratively refining sentence-level translations by utilizing contextual clues from the source and target antecedent sentences. Their experiments confirm the effectiveness of their approach by showing significant translation improvements, and by resolving various linguistic phenomena like co-reference and polysemy on both context-aware and context-agnostic baselines.

Lopes et al. [19] conducted a systematic comparison of different document-level MT systems based on large pre-trained language models. They introduced and evaluated a variant of Star Transformer [20] that incorporates document-level context. They showed the significance of their approach by evaluating test sets for anaphoric pronoun translation, demonstrating improvements for the same and overall translation quality.

Kim et al. [21] investigated advances in document-level MT using general domain (non-targeted) datasets over targeted test sets. Their experiments on non-targeted datasets showed that improvements could not be attributed to context utilization, but rather the quality improvements were attributable to regularization. Additionally, their findings suggest that word embeddings are sufficient for context representation.

Stojanovski and Fraser [14] explored the extent to which contextual information of documents is usable for zero-resource domain adaptation. The authors proposed two variants of the Transformer model to handle a significantly large context. Their findings on document-level context-aware NMT models showed that document-level context can be leveraged to obtain domain signals. Furthermore, the proposed models benefit from significant context and also obtain strong performance in multi-domain scenarios.

Yin et al. [22] introduced Supporting Context for Ambiguous Translations (SCAT), an English-to-French dataset for pronoun disambiguation. They discovered that regularizing attention with SCAT enhances anaphoric pronoun translation implying that supervising attention with supporting context from various tasks could help models to resolve other sorts of ambiguities.

Yun et al. [23] proposed a Hierarchical Context Encoder (HCE) to exploit context from multiple sentences using a hierarchical attentional network. The proposed encoder extracts sentence-level information from preceding sentences and then hierarchically encodes context-level information. The experiments for increasing contextual usage show that their approach of using HCE performs better than their baseline methods. In addition, a detailed evaluation of pronoun resolution shows that HCE can exploit contextual information to a great extent.

Maruf et al. [16] proposed a hierarchical attention mechanism for document-level NMT, forcing the attention to focus on keywords in relevant sentences in the document selectively. They also introduced single-level attention to utilizing sentence- or word-level information in the document context. The context representations generated are integrated into the encoder or decoder networks. Experiments on English-to-German translation show that their approach significantly improves over most of the baselines. Readers interested in a more detailed survey on document-level MT can consult the paper by [24].

To summarize, numerous architectures have been proposed for incorporating document-level context in recent times. In their approach, Wang et al. [4], Maruf and Haffari [1], Tiedemann and Scherrer [11], and Zhang et al. [13] mainly relied on modeling local context from previous sentences of the document. Some papers [5,25] use memory networks, a type of neural network that uses external memories or cache memories to keep track of the global context. Others [7,12,16,18,22] have focused on giving more importance to the usage of the attention mechanism. [6,15,23] use hierarchical networks to exploit context from multiple sentences. Miculicich et al. [6] proposed HAN which uses hierarchical attention networks to incorporate previous context into MT models. They modeled contextual and source sentence information in a structured way by using word- and sentence-level abstractions. More specifically, HAN considers the preceding n sentences as context for both source- and target-side data. Their approach clearly demonstrated the importance of wider contextual information in NMT. They show that their context-aware models can significantly outperform sentence-based baseline NMT models.

Usage of context in document-level translation were thoroughly investigated by [21]. Their analysis showed that improvements in translation were due to regularization and not context utilization. Lopes et al. [19] found that context-aware techniques are less advantageous in cases with larger datasets with strong sentence-level baselines when they systematically compared different document-level MT systems. Although the experiments by Miculicich et al. [6] show that context helps improve translation quality, it is not evident why their context-aware models perform better than those that do not take the context into account. We wanted to investigate why and when context helps to improve translation quality in document-level NMT. Accordingly, we performed a comprehensive qualitative analysis to better understand its actual role in document-level NMT. The subsequent sections first detail the dataset used for our investigation, describe the baseline and document-level MT systems, and present the results obtained.

3. Dataset Used

In this section, we detail the datasets that we used for our experiments for three language pairs.

3.1. Hindi-to-English

We used the IIT-Bombay (https://www.cfilt.iitb.ac.in/~parallelcorp/iitb_en_hi_parallel/, accessed on 27 March 2022) parallel corpus [26] for building our NMT systems. For development we took 1000 judicial domain sentences from the parallel corpus. For testing we used the term-annotated judicial domain test set (https://github.com/rejwanul-adapt/EnHiTerminologyData, accessed on 27 March 2022) released by [27]. We used the Moses toolkit (https://github.com/moses-smt/mosesdecoder, accessed on 27 March 2022) [28] to tokenize the English sentences. The Hindi sentences were tokenized using the tokenizer of the IndicNLP toolkit (https://anoopkunchukuttan.github.io/indic_nlp_library/, accessed on 27 March 2022). Since there was no discourse delimitation present in the Hindi-to-English test set, we manually annotated it with delimitation information, which is required for our experiments. The data statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Corpus statistics for Hindi-to-English.

3.2. Spanish-to-English

We used data from the TED talks (https://www.ted.com/talks, accessed on 27 March 2022). In our experiments, we used datasets provided by [29,30]. As suggested in [6], for development we used dev2010 and for testing we combined the tst2010, tst2011 and tst2012 test sets. For tokenizing English and Spanish words we used the tokenizer scripts available in Moses. The data statistics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Corpus statistics for Spanish-to-English.

3.3. Chinese-to-English

Like Spanish-to-English, we used data from the TED talks [29,30] (https://wit3.fbk.eu/2015-01, accessed on 27 March 2022). As suggested in [6], for validation we used dev2010 data and for evaluation against existing works we used a combined test set consisting of tst2010, tst2011, tst2012, and tst2013. We used the Moses tokenizer to tokenize the English sentences. As for Chinese, we used the Jieba segmentation toolkit (https://github.com/fxsjy/jieba, accessed on 27 March 2022). The data statistics are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Corpus statistics for Chinese-to-English.

4. The NMT Models

4.1. Transformer Model

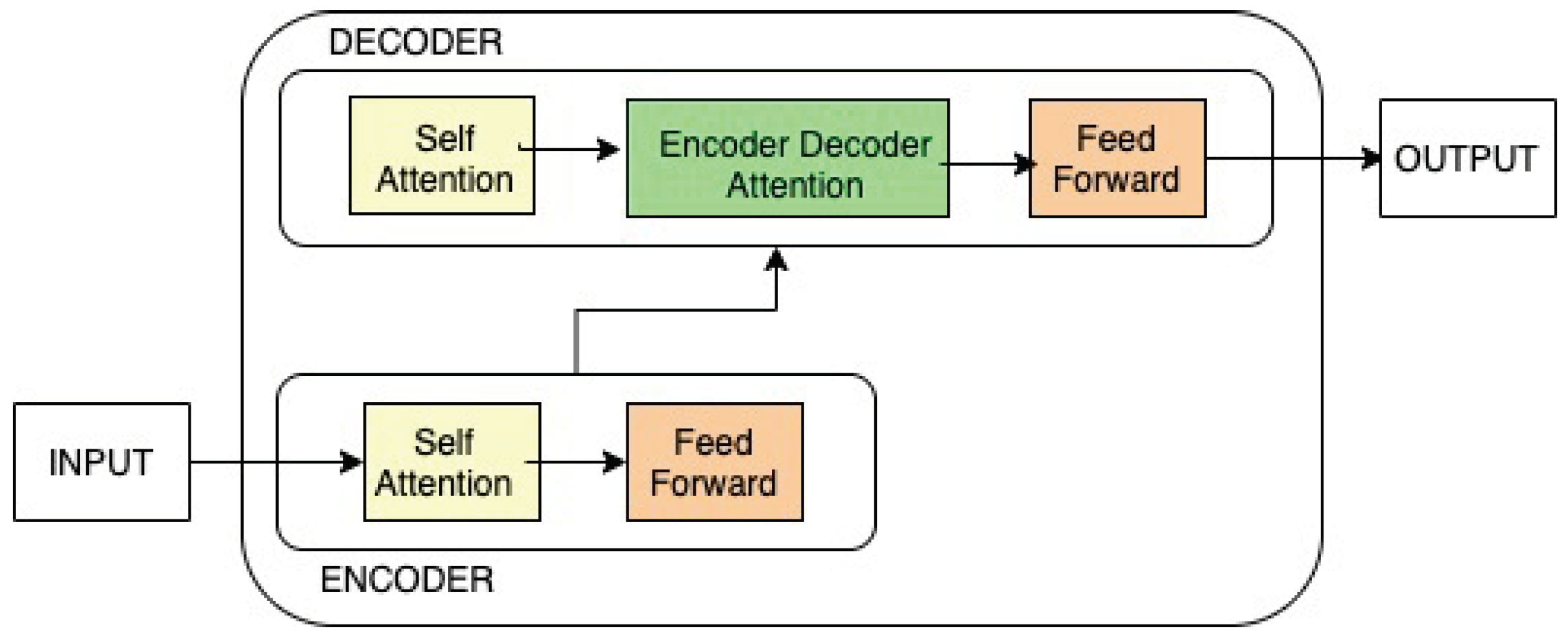

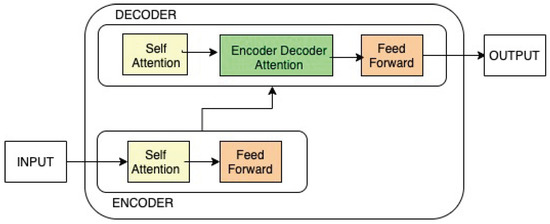

Transformer [3] has become the de facto standard baseline architecture for most Natural Language Processing tasks. The architecture utilizes neural networks to perform MT tasks. As shown in Figure 1, this model comprises two components: an encoder and a decoder. The encoder’s input is first routed through a self-attention layer, which allows the encoder to consider other words in the input sentence while encoding a specific word. Then, the output of the self-attention layer is fed to a feed-forward neural network, which is independently applied to each position. Both these layers are included in the decoder. Moreover, in between them is an attention layer that assists the decoder in focusing on relevant parts of the input sentence in order to generate the most appropriate target translation.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the Transformer architecture based on Figure 1 in [3].

Our NMT systems are Transformer models, and we used the OpenNMT framework [31] for training. We carried out a series of experiments in order to find the best hyperparameter configuration for our baseline model and observed that the following configuration lead to the best results: (i) size of the encoder and decoder: 6, (ii) heads for multi-head attention: 8, (iii) vocabulary size: 30,000, (iv) choice of optimizer: Adam [32], and (v) dropout was set to 0.1. The remaining set of hyperparameters are identical to those used in [3].

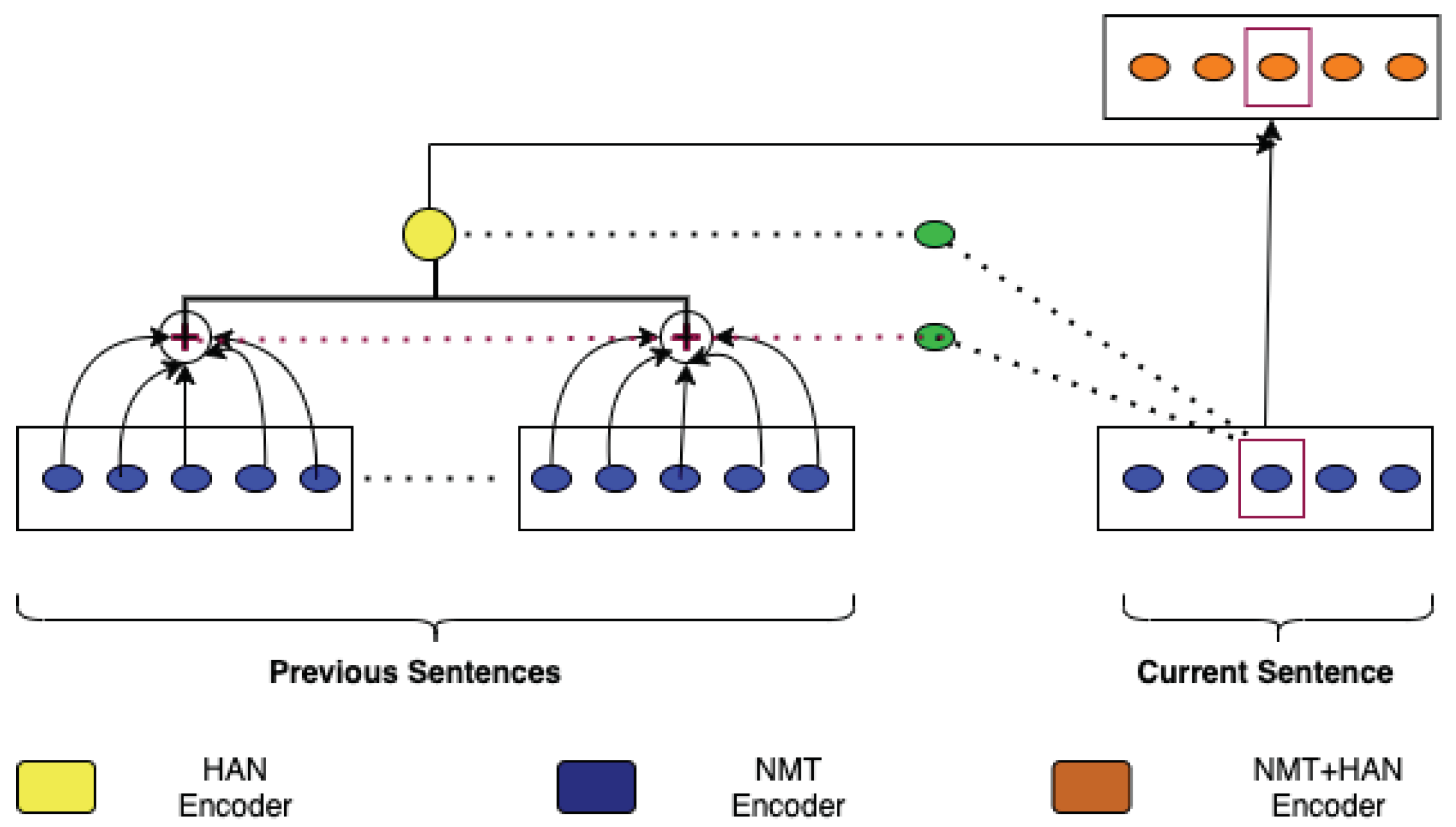

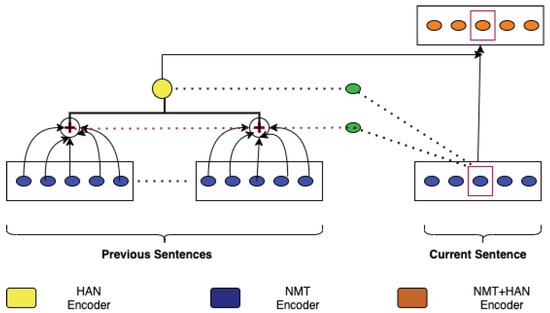

4.2. Context-Aware HAN Model

HAN is a context-aware NMT model that uses hierarchical attention to incorporate previous context. HAN models contextual and source sentence information in a structured way by using word- and sentence-level abstractions. For each predicted word, the hierarchical attention offers dynamic access to the context by selectively looking at different sentences and words. More specifically, HAN considers the preceding n sentences as context for both source and target data. As shown in Figure 2, context integration is accomplished by combining hidden representations from both the encoder and decoder of past sentence translations, as well as supplying input to both the encoder and decoder for the current translation. This kind of integration allows the model to optimize for numerous sentences at the same time. We used HAN in order to build our context-aware NMT models (we considered n = 3, i.e., context is formed with the previous three sentences as in [6]). For training HAN, we used the same hyperparameter configuration that we used to train our baseline Transformer MT systems (see Section 4.1).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the HAN architecture based on Figure 1 in [6].

5. Evaluation Strategy

The natural flow of sentences in a document provides contexts (e.g., previously appearing sentences) that are helpful for document-level MT (see Section 2). If one shuffles sentences in a document, that would usually disrupt the context in which the sentences appear. In this case, document-level MT would not naturally benefit from the context. In order to test the above hypothesis, we evaluated HAN on two different evaluation setups:

- 1.

- Original test set sentences: these are the set of sentences from the datasets whose statistics were shown in Section 3, and they maintain document-level contextual order. From now on, we call this test set OrigTestset.

- 2.

- Shuffled test set sentences: we randomly shuffle sentences of OrigTestset so that it does not maintain the original order of sentences. From now on, we call this test set ShuffleTestset. Note that OrigTestset and ShuffleTestset contain the same sentences but their contexts are different.

We translated both sets of sentences (i.e., OrigTestset, ShuffleTestset) using HAN in order to assess the impact of context on the quality of translations. For evaluation we used four standard benchmark automatic evaluation metrics: BLEU, chrF [33], METEOR [34] and TER [35]. The BLEU metric uses the overlap of n-grams between the reference sentences and translations by MT system. The chrF metric utilizes character n-grams and computes F-scores to assess the quality of translations produced by an MT system. To compute translation quality, Meteor metric uses flexible unigram matching, unigram precision, and unigram recall, as well as matching of basic morphological variants of each other. The Translation Edit Rate (TER) is a Levenshtein distance based metric that calculates the number of edit operations required to convert MT-output into a human reference. The scores for BLEU and TER metric range from 1 to 100, for chrF and METEOR they range from 0 to 1. High scores are an indication of better translation quality for BLEU, chrF and METEOR. When it comes to TER, lower scores indicate better translations.

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Results

We evaluated the MT systems (Transformer and HAN) on the Hindi-to-English, Spanish-to-English and Chinese-to-English translation tasks on OrigTestset, and present BLEU, chrF, TER and METEOR scores in Table 4. As can be seen from Table 4, HAN outperforms Transformer in terms of BLEU, chrF, TER and METEOR evaluation metrics. We performed statistical significance tests using bootstrap resampling [36]. We found the differences in scores statistically significant. This demonstrates that the context to be helpful when integrated into NMT models.

Table 4.

Baseline scores of NMT systems (HAN).

As mentioned above, in order to further assess the impact of context on translations produced by the HAN models, we randomly shuffled the test set sentences of OrigTestset five times, and created five different test sets, namely ShuffleTestsets. We evaluated the HAN models on these shuffled test sets (ShuffleTestsets) and report BLEU, chrF, TER and METEOR scores in Table 5. As can be seen from Table 5, the context-aware NMT model produces nearly similar BLEU, chrF, TER and METEOR scores across ShuffleTestsets. Although we see from the scores of Table 4 where context appeared to help in improving translation quality of HAN, the scores in Table 5 undermine the positive impact of context in HAN. We again carried out statistical significance tests using bootstrap resampling and found the differences in scores to be statistically significant.

Table 5.

Performance of NMT systems (HAN) on shuffled data.

Furthermore, we analyzed the translation scores (BLEU, chrF, TER and METEOR) generated by HAN and found that 14%, 16% and 17% of translations of the sentences significantly vary across five shuffles (i.e., five ShuffleTestsets) for Hindi-to-English, Spanish-to-English, and Chinese-to-English, respectively. We also observed that 58%, 64% and 61% of translations of the sentences do not vary or remain the same across the five shuffles (i.e., five ShuffleTestsets) for Hindi-to-English, Spanish-to-English, and Chinese-to- English, respectively.

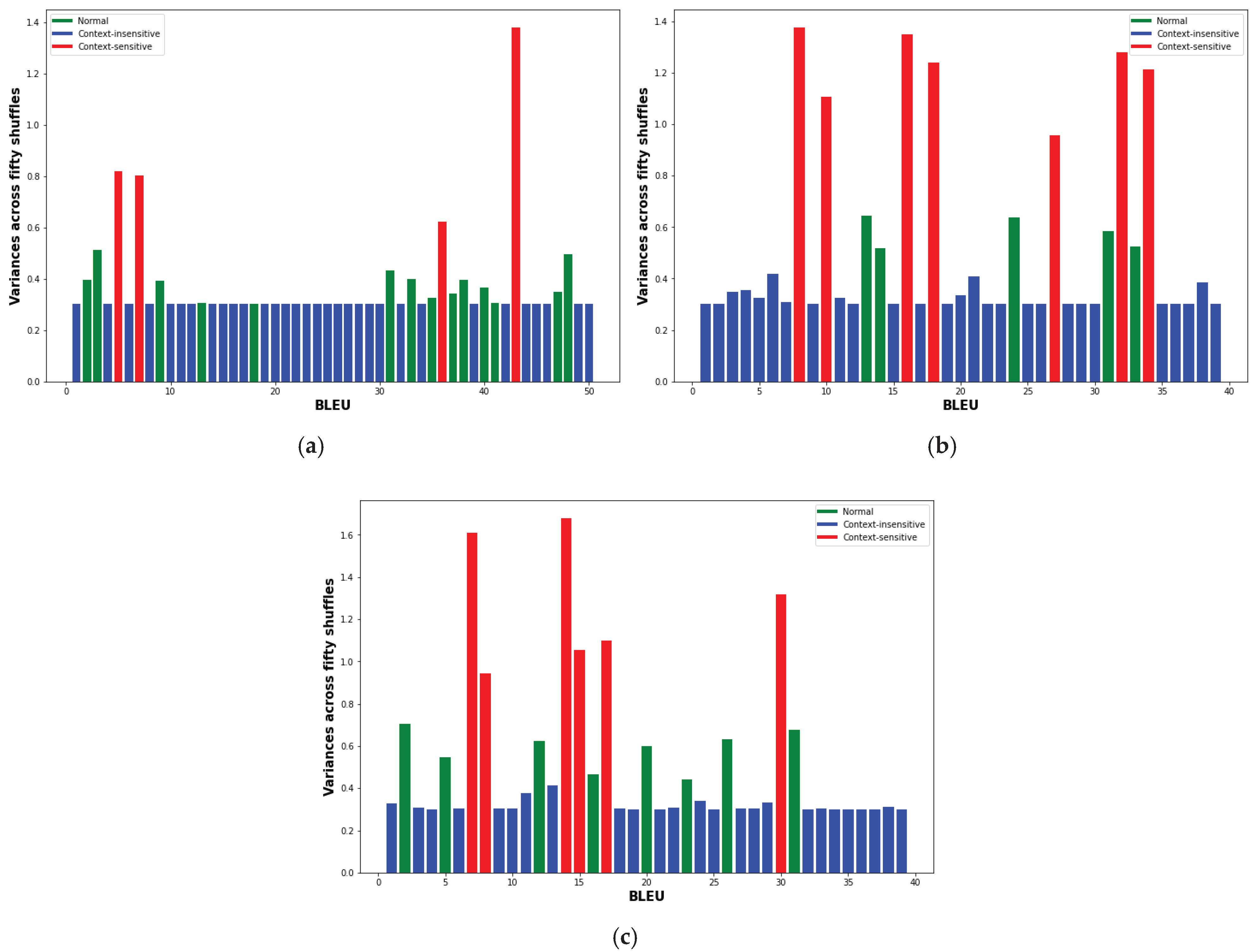

These findings encouraged us to scale up our experiments, so we increased the number of samples in order to obtain further insights. For this, we shuffled our test data fifty times and this provided us with fifty ShuffleTestSets. We computed the mean of the variances for each sentence in the discourse over the fifty ShuffleTestSets. From now on, we call this measure MV (mean of the variance). This resulted in a single MV score for each sentence in the test set. We then calculated the sample mean () and standard deviation (s) from the sampling distribution i.e., the MV scores, and the 95% confidence interval of the population mean () using the formula: = = . (The mean of the sampling distribution of equals the mean of the sampled population. Since the sample size is large (n = 50), we will use the sample standard deviation, s, as an estimate for in the confidence interval formula).

The last row of Table 6 shows the 95% confidence interval of BLEU, chrF, TER and METEOR obtained from the sampling distribution of MV scores of the test set sentences. The above method leads us to classify the test set sentences into three categories: (i) context-sensitive, (ii) context-insensitive, and (iii) normal. We focused on investigating sentences that belong to the two extreme zones (the first two categories), i.e., context-sensitive and context-insensitive. We now explain how we classified the test set sentences with an example. We selected two sentences from the test set of the Spanish-to-English task, and show the variances that were calculated from the distribution of the BLEU, chrF, TER and METEOR scores in the first two rows of Table 6. As can be seen from Table 6, variances of both sentences lie outside the confidence interval (CI). The one with a value higher than CI is classified as a context-sensitive sentence and a value lower than CI is classified as a context-insensitive sentence.

Table 6.

Mean variances of two sentences across fifty shuffles. They were selected from the test set of the Spanish-to-English task.

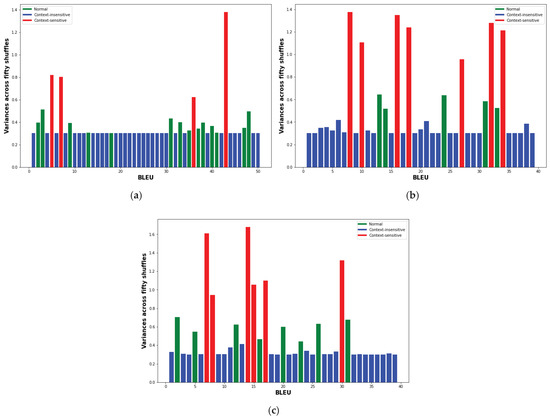

We also show the variances obtained for BLEU in Figure 3a–c, for Hindi-to-English, Spanish-to-English and Chinese-to-English, respectively. The green, blue and red bars represent normal, context-insensitive and context-sensitive sentences, respectively. The figures clearly separates distributions of sentences over the three classes.

Figure 3.

Mean variances of the test set sentences for BLEU and their corresponding classes (green: normal, blue: context-insensitive and red: context-sensitive). (a) Hindi-to-English (b) Spanish-to-English (c) Chinese-to-English.

Furthermore, we manually checked the translations of the sentences of context-sensitive and context-insensitive categories. We observed that contextual information indeed impacts the quality of the translations for the sentences of the context-sensitive class. We also observed that the quality of the translations mostly remains unaltered for the sentences of the context-insensitive class across shuffles.

6.2. Context-Sensitive Sentences

Context-sensitive sentences are those that are most susceptible to contextual influence. Their translations usually significantly vary with a change in preceding context. We observed that in such cases, the context either helps to improve the translations or degrades them. In Table 7, we report the maximum, mean and minimum scores of the set of context-sensitive sentences in a test set. Note that these statistics were calculated over all fifty ShuffleTestsets. We can clearly see from Table 7 that the translations of context-sensitive sentences are impacted by contextual information.

Table 7.

Evaluation scores for the set of context-sensitive sentences.

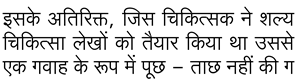

In Table 8, we give some examples of context-sensitive sentences for Hindi-to-English, Spanish-to-English, and Chinese-to-English for source, target, and various shuffle iterations. We see translations of the Hindi word  (examined) are “examined”, “questioned”, “questioned” in shuffle1, shuffle2, and shuffle3 sets, respectively. Similarly for Spanish-to-English, we see that the word Beethoven in the Spanish sentence is translated incorrectly to “symphony” in shuffle2, correctly in shuffle1 and produces no translation in shuffle3. In the case of Chinese-to-English, translation of the word 交响乐 is “Symphony” (target). In the case of shuffle1, we see that the MT system produces the correct translation for that Chinese word. As for shuffle2 and shuffle3, we see that the translations do not include the target counterpart of the Chinese word 交响乐.

(examined) are “examined”, “questioned”, “questioned” in shuffle1, shuffle2, and shuffle3 sets, respectively. Similarly for Spanish-to-English, we see that the word Beethoven in the Spanish sentence is translated incorrectly to “symphony” in shuffle2, correctly in shuffle1 and produces no translation in shuffle3. In the case of Chinese-to-English, translation of the word 交响乐 is “Symphony” (target). In the case of shuffle1, we see that the MT system produces the correct translation for that Chinese word. As for shuffle2 and shuffle3, we see that the translations do not include the target counterpart of the Chinese word 交响乐.

(examined) are “examined”, “questioned”, “questioned” in shuffle1, shuffle2, and shuffle3 sets, respectively. Similarly for Spanish-to-English, we see that the word Beethoven in the Spanish sentence is translated incorrectly to “symphony” in shuffle2, correctly in shuffle1 and produces no translation in shuffle3. In the case of Chinese-to-English, translation of the word 交响乐 is “Symphony” (target). In the case of shuffle1, we see that the MT system produces the correct translation for that Chinese word. As for shuffle2 and shuffle3, we see that the translations do not include the target counterpart of the Chinese word 交响乐.

(examined) are “examined”, “questioned”, “questioned” in shuffle1, shuffle2, and shuffle3 sets, respectively. Similarly for Spanish-to-English, we see that the word Beethoven in the Spanish sentence is translated incorrectly to “symphony” in shuffle2, correctly in shuffle1 and produces no translation in shuffle3. In the case of Chinese-to-English, translation of the word 交响乐 is “Symphony” (target). In the case of shuffle1, we see that the MT system produces the correct translation for that Chinese word. As for shuffle2 and shuffle3, we see that the translations do not include the target counterpart of the Chinese word 交响乐.

Table 8.

Context-sensitive sentence example for the three language pairs.

6.3. Context-Insensitive Sentences

Context-insensitive sentences are those that are least susceptible to contextual influence. This category of sentences maintain their translation quality irrespective of the context provided. In Table 9, we report the maximum, mean and minimum scores for the set of context-insensitive sentences in a test set. We can clearly see from Table 9 that the context-insensitive sentences are less impacted by contextual information as compared with the context-sensitive sentences.

Table 9.

Evaluation scores for the set of context-insensitive sentences.

We observed that the BLEU and chrF scores remain almost constant across the shuffles regardless of the different contexts. Therefore, we can conclude that context has little or zero impact on the translation quality of context-insensitive sentences.

6.4. Discussion

We carried out our experiments to see how context usage by HAN impacts the quality of translation. We presented our results in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 7. The scores in the tables clearly indicate as expected that the HAN architecture is sensitive to context. This finding corroborates our analysis at the sentence level. In our sentence-level analysis, NMT systems produce different translations for each of the context-sensitive sentences when they are provided with different contexts. Furthermore, we also observed from the scores presented in Table 4 that context is useful in improving the overall translation quality.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we investigated the influence of context in NMT. Based on our results of the experiments we carried out for Hindi-to-English, Spanish-to-English, and Chinese-to-English, we found that, as expected, the HAN model is sensitive to context. This is indicated by our observations that the context-aware NMT system significantly outperforms the context-agnostic NMT system in terms of BLEU, chrF, TER and METEOR. We probed this and found this is due to the context-sensitive class of sentences that is impacting the translation quality the most.

These findings also lead us to categorize the test set sentences into three classes: (i) context-sensitive (ii) normal and (iii) context-insensitive sentences. While the translation quality of context-sensitive sentences is affected by the presence or absence of the correct contextual information, the translation quality of context-insensitive sentences is not sensitive to context. We believe that investigating this problem (i.e., identifying correct context for context-sensitive sentences) could positively impact discourse-level MT research. In future, we plan to examine the characteristics of contexts of the source sentences in the context-sensitive class in order to better understand why the translation of these sentences is so sensitive to context.

We also plan to build a classifier that can recognize the context-sensitive sentences of a test set. Our next set of experiments will focus on identifying and providing the correct context to the sentences of the context-sensitive class. We also aim to investigate how the presence of terminology in context or in the source sentence can impact the quality of translations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.N., R.H., J.D.K. and A.W.; methodology, P.N., R.H., J.D.K. and A.W.; experiment implementation, P.N.; analysis, P.N., R.H., J.D.K. and A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N. and R.H.; writing—review and editing, R.H., J.D.K. and A.W.; funding acquisition, A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was conducted with the financial support of the Science Foundation Ireland Centre for Research Training in Digitally-Enhanced Reality (d-real) under Grant No. 18/CRT/6224 and Microsoft Research Ireland.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this work is freely available for research. We have provided url link for each of the data sets used in our experiments in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Luong, T.; Pham, H.; Manning, C.D. Effective Approaches to Attention-based Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Lisbon, Portugal, 17–21 September 2015; pp. 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.U.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Tu, Z.; Way, A.; Liu, Q. Exploiting Cross-Sentence Context for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 7–11 September 2017; pp. 2826–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maruf, S.; Haffari, G. Document Context Neural Machine Translation with Memory Networks. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miculicich, L.; Ram, D.; Pappas, N.; Henderson, J. Document-Level Neural Machine Translation with Hierarchical Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018; pp. 2947–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voita, E.; Serdyukov, P.; Sennrich, R.; Titov, I. Context-Aware Neural Machine Translation Learns Anaphora Resolution. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.; Aue, A.; Chen, C.; Chowdhary, V.; Clark, J.; Federmann, C.; Huang, X.; Junczys-Dowmunt, M.; Lewis, W.D.; Li, M.; et al. Achieving Human Parity on Automatic Chinese to English News Translation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.05567. [Google Scholar]

- Toral, A.; Castilho, S.; Hu, K.; Way, A. Attaining the Unattainable? Reassessing Claims of Human Parity in Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Third Conference on Machine Translation: Research Papers, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–1 November 2018; pp. 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Läubli, S.; Sennrich, R.; Volk, M. Has Machine Translation Achieved Human Parity? A Case for Document-level Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018; pp. 4791–4796. [Google Scholar]

- Tiedemann, J.; Scherrer, Y. Neural Machine Translation with Extended Context. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Discourse in Machine Translation, Copenhagen, Denmark, 8 September 2017; pp. 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bawden, R.; Sennrich, R.; Birch, A.; Haddow, B. Evaluating Discourse Phenomena in Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018. Volume 1 (Long Papers). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Yang, B.; Ye, W.; Zhang, S. Multi-Hop Transformer for Document-Level Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Online. 6–11 June 2021; pp. 3953–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovski, D.; Fraser, A. Addressing Zero-Resource Domains Using Document-Level Context in Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Domain Adaptation for NLP, Kyiv, Ukraine, 19–20 April 2021; pp. 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, D.; Zhou, G. Hierarchical Modeling of Global Context for Document-Level Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruf, S.; Martins, A.F.T.; Haffari, G. Selective Attention for Context-aware Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 3092–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. Bleu: A Method for Automatic Evaluation of Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 7–12 July 2002; pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, M. A Simple and Effective Unified Encoder for Document-Level Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online. 5–10 July 2020; pp. 3505–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.; Farajian, M.A.; Bawden, R.; Zhang, M.; Martins, A.F.T. Document-level Neural MT: A Systematic Comparison. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation, Lisboa, Portugal, 3–5 November 2020; pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Qiu, X.; Liu, P.; Shao, Y.; Xue, X.; Zhang, Z. Star-Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Tran, D.T.; Ney, H. When and Why is Document-level Context Useful in Neural Machine Translation? In Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Discourse in Machine Translation (DiscoMT 2019), Hong Kong, China, 3 November 2019; pp. 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Fernandes, P.; Pruthi, D.; Chaudhary, A.; Martins, A.F.T.; Neubig, G. Do Context-Aware Translation Models Pay the Right Attention? In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), Online. 1–6 August 2021; pp. 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Hwang, Y.; Jung, K. Improving Context-Aware Neural Machine Translation Using Self-Attentive Sentence Embedding. Proc. Aaai Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 9498–9506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruf, S.; Saleh, F.; Haffari, G. A Survey on Document-Level Neural Machine Translation: Methods and Evaluation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shi, S.; Zhang, T. Learning to Remember Translation History with a Continuous Cache. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2018, 6, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunchukuttan, A.; Mehta, P.; Bhattacharyya, P. The IIT Bombay English-Hindi Parallel Corpus. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), Miyazaki, Japan, 7–12 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, R.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Way, A. Investigating Terminology Translation in Statistical and Neural Machine Translation: A Case Study on English-to-Hindi and Hindi-to-English. In Proceedings of the RANLP 2019: Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing, Varna, Bulgaria, 2–4 September 2019; pp. 437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Koehn, P.; Hoang, H.; Birch, A.; Callison-Burch, C.; Federico, M.; Bertoldi, N.; Cowan, B.; Shen, W.; Moran, C.; Zens, R.; et al. Moses: Open Source Toolkit for Statistical Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics Companion Volume Proceedings of the Demo and Poster Sessions, Prague, Czech Republic, 25–27 June 2007; pp. 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Cettolo, M.; Girardi, C.; Federico, M. WIT3: Web Inventory of Transcribed and Translated Talks. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual conference of the European Association for Machine Translation, Trento, Italy, 28–30 May 2012; pp. 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Cettolo, M.; Niehues, J.; Stuker, S.; Bentivogli, L.; Cattoni, R.; Federico, M. The IWSLT 2015 evaluation campaign. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Spoken Language Translation, Da Nang, Vietnam, 3–4 December 2015; pp. 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, G.; Kim, Y.; Deng, Y.; Senellart, J.; Rush, A. OpenNMT: Open-Source Toolkit for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the ACL 2017, System Demonstrations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017; pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. San Diego 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, M. chrF: Character n-gram F-score for automatic MT evaluation. In Proceedings of the Tenth Workshop on Statistical Machine Translation, Lisbon, Portugal, 17–18 September 2015; pp. 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Lavie, A. METEOR: An Automatic Metric for MT Evaluation with Improved Correlation with Human Judgments. In Proceedings of the ACL Workshop on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Evaluation Measures for Machine Translation and/or Summarization, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 29–30 June 2005; pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Snover, M.; Dorr, B.; Schwartz, R.; Micciulla, L.; Makhoul, J. A Study of Translation Edit Rate with Targeted Human Annotation. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference of the Association for Machine Translation in the Americas: Technical Papers, Cambridge, MA, USA, 8–12 August 2006; pp. 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Koehn, P. Statistical Significance Tests for Machine Translation Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2004 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Barcelona, Spain, 25–26 July 2004; pp. 388–395. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).