Abstract

Using a qualitative research-based approach, this study aimed to understand (i) the way home-based teleworkers in France perceive and organize their professional activities and workspaces, (ii) their teleworking conditions, (iii) the way they characterize the modalities and the nature of their interactions with their professional circle, and more broadly (iv) their quality of life ‘at work’. We performed a lexical and morphosyntactic analysis of interviews conducted with 28 teleworkers (working part-time or full-time from home) before the COVID-19 crisis and the associated establishment of emergency telework. Our results confirm and complement findings in the literature. Participant discourses underlined the beneficial effects of teleworking in terms of professional autonomy, flexibility, concentration, efficiency, performance, productivity, and being able to balance their professional and private lives. Nevertheless, they also highlighted the deleterious effects of teleworking on temporal workload, setting boundaries for work, work-based relationships and socio-professional integration. Despite the study limitations, our findings highlight the need for specific research-based and practical strategies to support the implementation of a sustainable telework organization in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, the implementation of digital technologies has greatly contributed to the transformation of workspaces, alterations in the timing of work activities and their duration, as well as the structuring of technology-mediated work and remote working. In its contemporary sense, remote working has gradually become teleworking (i.e., work performed remotely which relies on new information and communication technologies). There is no consensus on a definition for teleworking; however, a remote work location and the use of information and communication technologies are two of the criteria most frequently cited [1,2]. With regards to the categorisation of teleworking, scholars are divided as to whether part-time work (as opposed to full-time), and whether self-employment (as opposed to working for an employer) should be considered [1]. Despite this discordance, researchers usually agree on three broad categories which depend on where the work is done: home-based teleworking, mobile or nomadic teleworking, and teleworking at a telecentre or satellite office.

In its current form, teleworking impacts the design, nature and spatiotemporal organization of work, organizational culture and the individual’s relationship with their work, the relational dynamics within work teams and, more broadly, the balance between working and private lives [2,3,4]. One consequence of this is the large number of studies focusing on teleworking using different approaches and scientific disciplines (e.g., ergonomics, work psychology, work sociology, economics and management, human resources, medicine). Despite the quality and quantity of studies conducted, results regarding the effects of teleworking on workers’ professional and personal spheres are varied and sometimes contradictory. In addition, most studies in this field adopt quantitative and extensive approaches, which are able to identify explanatory and generalizable mechanisms (e.g., cause and effect relationships). Qualitative studies attempting to understand teleworking situations as a whole are less frequent. Such studies make it possible to understand the most salient processes at play and the way they interact with each other.

In this context, using a comprehensive and systematic approach, we conducted a qualitative study of 28 home-based teleworkers in France in order to examine the impact of home-based teleworking on professional activity and the conditions under which it is conducted. Specifically, we investigated (i) the nature of teleworking-related activities, the spatiotemporal organization of teleworking at home (vs. the organization of non-work based activities at home), the quality of work, and conditions for teleworking at home, (ii) the nature and modalities of teleworkers’ relationships with their professional circle, and (iii) the way in which professional practices and psychosocial processes in the context of home-based telework potentially match those at the employer’s premises (“on-site” hereafter).

The study was conducted a few weeks before the COVID-19 health crisis began, and before the country’s first lockdown period. Therefore, this work did not investigate mandatory teleworking which was established in the initial period of the crisis.

As we shall see, this qualitative study identifies the benefits of teleworking from home and associated professional and psychosocial constraints and risks. In particular, it provides an in-depth systemic understanding of the choices which home-based teleworkers make in terms of work planning and task allocation. It also helps identify the psychological mechanisms that can explain the effects of teleworking from home on socio-professional integration and social cohesion, as well as its potentially deleterious impact on health. It constitutes a valuable study to interpret and combine existing research, to understand paradoxical findings in research on teleworking to date, and to identify opportunities for future research. Its results are of special importance given the current social context in health and healthcare and as a significant increase and acceleration of teleworking has been observed at the European and global levels even in the post-COVID-19 crisis era [5].

After reviewing the main research studies on the effects (both positive and negative) of teleworking in the professional field, we present the results of a lexical and morphosyntactic analysis of the study participant discourses. We then discuss these results with regard to the existing scientific literature and suggest future research opportunities which could increase knowledge in this field and inform policymaking on teleworking practices and measures to deploy inside organizations.

2. The Effects of Teleworking in the Professional Sphere

Results from studies conducted to date to determine the effects of teleworking in the professional sphere are varied and sometimes contradictory [1,2,3,6]. While some studies highlight positive effects, others are less categorical or highlight negative effects.

2.1. The Benefits of Teleworking in the Professional Sphere

The benefits of teleworking in the professional sphere include reduced interruptions during professional activities, fewer distractions, and the rest time necessary for work recovery. The result is better concentration, professional efficiency, performance and productivity [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Teleworking also fosters a feeling of control over one’s working time and flexibility, together with a greater perceived level of control in terms of task performance, organization and carrying out one’s daily work [10,12,13,14,15]. It reinforces a feeling of autonomy and strengthens motivation at work, as well as organizational commitment and job satisfaction [5,6,9,11,12,16]. Furthermore, teleworking not only reduces the perception of professional stress, but is a resource for coping with it, irrespective of whether this stress is the result of frequent interruptions in the usual work environment or very demanding professional situations [17].

The above-mentioned benefits have been qualified and refined in various studies. The meta-analysis conducted by Gajendra and Harrison [12] indicated that while teleworking fosters better performance—measured using objective indicators or supervisor appraisals—it has no significant effect on self-assessed performance. In their study of 245 employees in two large information and financial service organizations geographically distributed in the United States, Kossek, Lautsch and Eaton [18] highlighted that only formalised teleworking fosters greater supervisor-perceived performance in terms of quality of work, the number of errors made, and meeting the supervisor’s expectations. Based on interviews with 92 teleworkers, 72 non-teleworkers, and 33 supervisors in public Costa Rican institutions, Solís [19] showed that the positive influence of teleworking on in-role performance (i.e., activities related to employees’ formal role requirements), proactivity, and the adaptability of workers depend on the level of control which they perceive their superior has over their (i.e., the workers) professional activity; the less the perceived control, the greater is the teleworker’s efficiency. Other authors explain that the positive effects of teleworking in terms of results (quantity and quality of work, respecting deadlines) and attitudes at work (involvement, satisfaction) are especially present when employees have support from their superior, and when they perceive organizational support [20,21].

With regard to increased work satisfaction, Virick, DaSilva and Arrington [22] showed that this benefit depends above all on the proportion of work performed remotely from the company premises. They highlighted that the least-satisfied teleworkers in a global telecommunications organization in the US were those who worked from home for the fewest days a week and for the most days a week (inverted U-shaped relationship). The study by Bentley and al. [23] conducted on teleworkers in 28 organizations in New Zealand showed that irrespective of the proportion of teleworking in their overall working time (hereafter “intensity”), organizational support—such as social support from superiors and colleagues—fostered job satisfaction in teleworkers and reduced work-based stress. Similar results were found by Nakrošienė, Bučiūnienė, and Goštautaitė’s study [24] in a study of 128 home-based teleworkers from the IT, insurance and telecommunication sectors in Lithuania. Specifically, they showed that workers’ overall satisfaction with teleworking was predicted by their supervisor’s trust and the suitability of the working place at home.

Finally, teleworking was associated with lower absenteeism rates, lower intention to leave rates (versus employee retention), and lower staff turnover rates [4,9,12]. With regard to intention to leave, Golden’s [25] results from a survey of 393 professional-level teleworkers in a large corporation indicate that the effects of teleworking depend on its intensity. More specifically, the author found that the more employees had a high proportion of teleworking in their working time, the more they were involved in their company, the less emotionally exhausted they were, and the less likely they were to leave. Finally, in their study conducted on the Big Four Accounting Firms (Deloitte, Ernst & Young, KPMG, and PricewaterhouseCoopers), Greer and Payne [26] found that the decrease observed in “intention to leave” in teleworkers was especially noticeable for workers who had discussed their transition to teleworking in depth with their family.

2.2. The Negative Effects of Teleworking in the Professional Sphere

A large number of studies highlight the negative effects of teleworking on workload and health as well as on teleworkers’ relationships with their professional sphere. Below, we describe the various findings in different sub-sections.

2.2.1. Teleworking, Workload and Teleworkers’ Health

For some authors, the results observed in terms of gains in teleworkers’ productivity, efficiency and quality of work are in reality due to an extension, an intensification and a densification of their working time [8,9,15,27,28,29]. They suggest that since teleworking reduces commuting and allows more flexible professional organization, teleworkers tend to increase their weekly working time and allocate the time they previously spent on travel to their professional activities [13,14,30,31,32]. Kelliher and Anderson’s [16] study of three organizations in the UK private sector found that this increase in working time may also be explained by social exchange theory. As teleworking in many companies is considered a privilege which is not accessible to everyone, teleworkers may feel indebted to their organization and accordingly may put more effort into paying this debt.

Echoing the studies cited above, several authors have raised the problem of the deleterious effects of teleworking on health. Considering that teleworkers are exposed to certain occupational risks for a longer time (e.g., fewer interruptions and less frequent breaks), teleworking can accentuate the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders [14]. Teleworking is also a source of overwork, workaholism, professional stress and professional burnout [14,31,33,34]. In their study of 303 executives working in a service company in France, Metzger and Cléach [31] found that under the pressure of “internalized guilt” (i.e., guilt about being able to work while escaping certain routine work-based constraints such as travel time, office noise, etc.), there are no limits to teleworkers’ working time. Bentley et al. [23] indicated that teleworkers’ perception of professional isolation fosters perceived professional stress. Based on qualitative research conducted with 63 Quebec teleworkers, Montreuil and Lippel [15] described the situation of a group of teleworkers who received no information from their supervisor about their professional objectives or about the criteria used to evaluate their work; they felt they were being side-lined, and feared they would no longer be offered interesting cases or tasks. All this led to such a degree of uncertainty and anxiety that they had long periods of sick leave because of professional burnout. Similar trends have also been seen in recent reports which observed a significant and positive link between the growth of teleworking and exposure to psychosocial risks in various work organizations (e.g., unpredictable schedules, perception of excessive workload, tension with colleagues and supervisors [34]).

2.2.2. Teleworking and Relationships with One’s Professional Sphere

Despite the potential of communication technologies and remote collaboration, studies examining the impact of teleworking on relationships with one’s professional sphere mainly mention its negative effects. They consider that teleworking harms communication and cooperation within work teams [35]. More specifically, they show that teleworkers’ exchanges and discussions with their colleagues and superiors are less frequent and of lower quality when they work remotely from their company [10,12]. Teleworkers’ physical separation from work colleagues also entails psychological separation, and a feeling of exclusion from the work organization, both of which negatively affect their satisfaction and performance [34,36,37]. Indeed, the risk of professional and social isolation as well as fragmentation of work groups is often emphasized in the literature [32,38,39]. Empirical studies support these statements, highlighting a lack of informal and spontaneous interactions with colleagues, as well as teleworkers’ feelings of loneliness [10,40].

Because of this physical separation, teleworkers are also less exposed to the norms, rules and values of the company, and consequently are less attached, less engaged, and more independent. Their sense of belonging is less strong, and they identify less with their work organization [4,15,38,41]. A survey conducted by Walrave and De Bie [42] in five European countries found that professional isolation is felt more strongly by teleworkers who work remotely from their professional sphere (i.e., who work from home) than by those who telework in dedicated spaces where they have the opportunity to work with other members of their organization (e.g., telecentres).

Moreover, several studies show that teleworkers face social pressure from their professional circle. They consequently develop specific strategies in order to remain “accessible” and visible to their colleagues, and to prove to the latter that they are working despite their physical absence [26,35]. Social representations about teleworking are often associated with negative connotations in the professional sphere: a lack of understanding, mistrust or even a certain hostility can show through comments emanating from colleagues, superiors and clients who no longer have the usual visual indicators to gauge teleworkers’ professional investment or the activities they perform [26].

2.3. The Effects of Teleworking on Work–Life Balance

A very large number of empirical studies have sought to determine the influence of teleworking on work–life balance with mixed results.

Some place greater focus on the positive impact of telework on the work–life balance. Gajendra and Harrison’s meta-analysis highlighted this [12]. More specifically, they found that teleworking was associated with having more time for family activities and relationships (which in turn is the result of less stress and saving time previously spent on travel), greater control over the times during the day devoted to work, and greater temporal flexibility [13,15,31,43]. These temporal benefits make it possible to better prioritize, manage and organize different activities in the various areas of their life. In turn, this leads to greater reconciliation of one’s multiple roles (worker, parent, etc.).

Other studies have placed more emphasis on the negative consequences of teleworking on the work–life balance. Noonan and Glass’s study [44], which was based on two national probability samples in the USA, highlighted that teleworking does not lead to a better work–life balance. Other authors highlighted that teleworkers found it difficult to simultaneously cope with professional and family demands and to respond to requests from the latter (needs which become all the more pressing when teleworking from home) [45,46]. In other studies, teleworkers reported the difficulties they had keeping an eye on the amount of time they spent at work every day, and not letting themselves be taken over by it [10,19,43]. Furthermore, they considered that the spatiotemporal entanglement of their professional and personal activities at home prevented them from adequately performing these activities [10,31,32,39]. Studies focusing on the work–life balance also highlight a perception by teleworkers that the boundaries between their different areas of life are blurred [43]. In addition, the emergence of misunderstandings, tensions and conflicts with family and friends, as well as an increase in stress in the private sphere are frequently observed, both from the point of view of teleworkers and their loved ones [43].

Although the studies in the field of teleworking presented in the previous paragraphs provide information about potential related changes in practices in the professional sphere (see Table 1), research is relatively sparse, and results are varied and sometimes contradictory. This makes it difficult to understand the direct and indirect effects of teleworking, as well as the factors that moderate these effects. Our objective was to complement existing scientific work in this field, which is more anchored in quantitative and extensive approaches, with a qualitative study using a comprehensive and a systemic approach. This approach provides the simultaneous understanding of the practices and psychosocial processes at play in the home-based teleworking context, and their potential links with the on-site working context.

Table 1.

Summary of the effects of teleworking in the professional sphere and on the work–life balance.

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Study Objectives

The present study aimed to describe how home-based teleworkers (i) define their work activities, organize their work space and working times (i.e., when, where, how, and for how long) and therefore their private space and time, (ii) interact and work with colleagues (whether teleworkers or not), qualify their relationships with other members of their professional sphere and, more generally, (iii) perceive these work activities and social interactions, and the conditions under which these interactions occur in relation to their on-site activities, relationships and decisions.

3.2. Procedure

In order to meet our research objectives, we conducted a qualitative, heuristic-type study of home-based employees who were teleworking either full-time or part-time—as these are the most common types of teleworking e.g., [23]—and who were teleworking on a formal basis (i.e., where teleworking was stipulated in a contract and/or was part of an agreement and/or recognized as part of the organizational system)

Participants were solicited through announcements posted on specialized teleworking forums, messages sent to HR managers of targeted companies, and word of mouth (mobilization of the professional sphere).

Semi-structured telephone interviews were performed by one of the study researchers. After discussing their professional career, the reasons why they were teleworking and the modalities of their telework, participants were invited to: (a) describe the organization and spatiotemporal management of their daily and weekly individual and group-based professional activities; (b) compare their relationships with their professional sphere (teammates, colleagues, superiors, etc.) when teleworking with on-site work; (c) describe work–life changes they had noticed since moving to teleworking; (d) list the main advantages and disadvantages of teleworking compared with on-site work.

All volunteers who met the inclusion criteria were surveyed until data saturation.

3.3. Participant Characteristics

Twenty-eight teleworkers, all employees in the private sector and on permanent contracts, participated in the study. Fifteen and thirteen were teleworking part-time and full-time, respectively. The vast majority of the former (12/15) worked from home between 1 and 2 days a week. The average time teleworking (whether part-time or full-time) was 5 years (range 1 to 14 years).

The participants worked in various business sectors (banking and insurance, computing, telecommunications, information technology, marketing, tourism, climate control engineering, environmental safety quality, market research and opinion polls) with different jobs and positions (e.g., graphic designer, lawyer, management controller, IT engineer, technical support analyst, business manager, data protection officer).

Fewer than half (11/28) had a room in their home dedicated exclusively to their professional activity. Five others had set up a workspace in a room used for another purpose (e.g., living room or bedroom) while the remaining 12 reported they have no specific workspace.

The study population comprised 17 women and 11 men. Mean age was 41 years (ranging from 25 to 55). Of those, 7 participants lived alone, 7 with a partner, 10 with a partner and children, and 4 only with their children; 6 of the 14 teleworkers with dependent children at home had children aged over 12 years old.

3.4. Data Analysis

We performed a lexical and morphosyntactic analysis of the transcribed participant discourses using the Alceste software package [47]. One of the major advantages of this technique for textual data analysis is the inductive nature of the process. Moreover, the implementation of the Alceste methodology allows a systematization of the textual analysis, which avoids any biases linked to researcher subjectivity when units of analysis are defined during manual processing.

Alceste makes it possible to identify the main “lexical universes” (i.e., the speaker’s universes of thought) present in a corpus. It emphasizes the similarities and dissimilarities in the vocabulary in order to identify polarity in the use of vocabulary and to describe the distribution of vocabulary in the studied text. This makes it possible to identify the presence of discourse classes each of which comprises a set of statements called Elementary Context Units (ECU) which are homogeneous in terms of co-occurrence of the vocabulary that comprises them. These classes differ significantly from each other.

Alceste first categorizes participant responses based on Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC). It then tries to establish a correspondence between the answers of an individual and those of other individuals or groups of individuals from illustrative variables (in our case, teleworking worktime, number of years teleworking, characteristics of the workspace at home, age, sex, family members living at home).

After recording these indications, the researcher’s task is to attribute a meaning to each of the classes identified from the corresponding semantic field.

4. Results

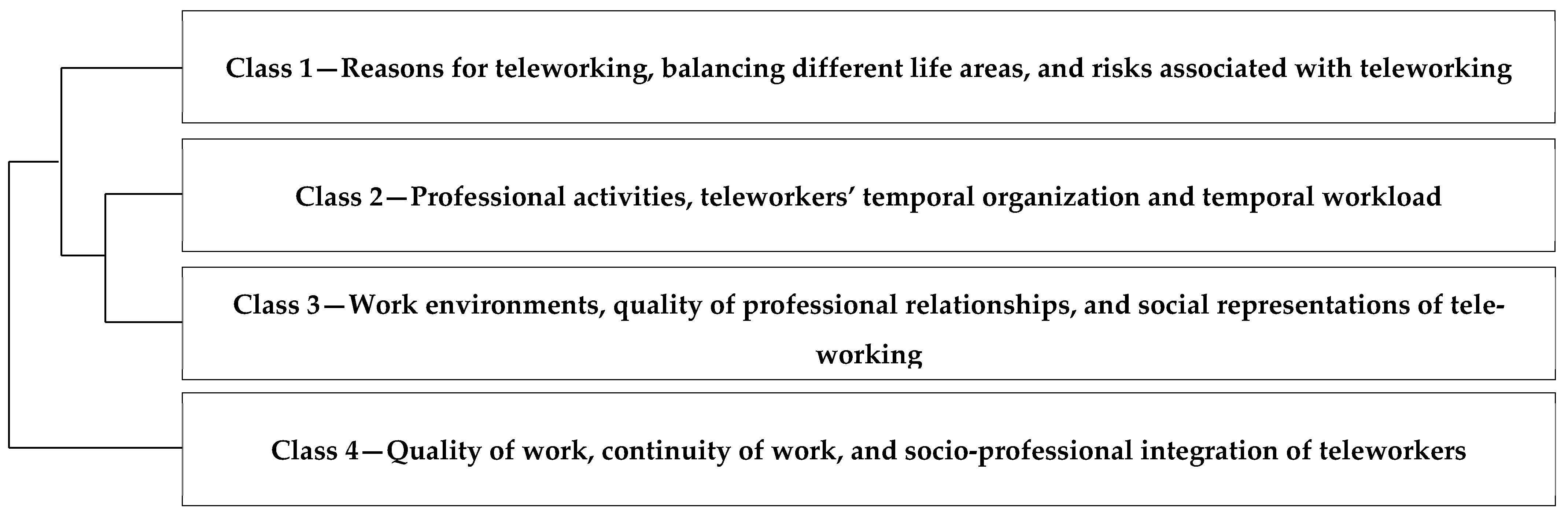

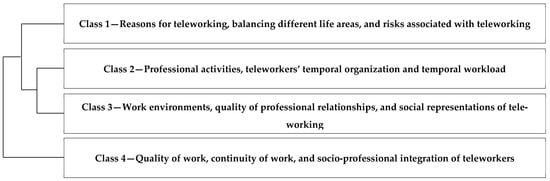

In our study, the DHC showed that the corpus could be divided into four classes. These classes represented the great majority of all the interviewee discourses (94.19% of the corpus, or 2772 ECU).

In the dendrogram (see Figure 1), we can see that Classes 1, 2, and 3 are very distant from (i.e., are very dissimilar to) Class 4. The first three classes focus on the nature of professional activities, tools, temporality, and the interconnection of professional activities (individual and collective) as well as the conditions for performing these activities. Instead, Class 4 focuses more on the results of activities and the risks inherent in working remotely.

Figure 1.

Dendrogram of the stable classes identified from the Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC). Alceste uses the chi-square measurement of association to assess the extent to which the interviewee discourses, according to their attributes, is or is not associated with a particular class of vocabulary.

We used the following three indices: specific vocabulary (χ2), ECU and the illustrative variables significantly associated with each of these classes allowed us to describe them (i.e., the four classes) in greater detail. In order to present our results more clearly, all the while ensuring anonymity, we assigned each teleworker a fictitious first name. Results for the four classes are described below.

4.1. Class 1—Reasons for Teleworking, Balancing Different Life Areas, and Risks Associated with Teleworking

Class 1 included 985 ECU (35.3% of the analyzed corpus). The discourses of home-based teleworkers with children (χ2 = 13.55; p < 0.01) and those of teleworking women (χ2 = 11.34; p < 0.01) were over-represented. This class covered the reasons behind the move to teleworking, the spatiotemporal organization of home-based teleworking and its benefits—particularly in terms of other life areas—and the risks associated with spatiotemporal organization of teleworking at home (vs. not teleworking at home) in terms of professional and health inequalities (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Themes associated with the specific vocabulary of Class 1.

With regard to the reasons (“reason”; p < 0.01) for the move to teleworking, the vast majority of home-based teleworkers (22/28) explained that they requested it on their own initiative. The most frequently cited reason for requesting teleworking (13/22) was linked to commuting (not only in terms of travel time, but also poor travel conditions and heavy traffic). Nine (9/22) teleworkers also mentioned familial reasons (geographic mobility to be able to join a spouse who relocated for work, birth of children, health problems of a family member requiring presence and/or geographic mobility). In addition, 7 of the 22 teleworkers who requested teleworking mentioned the chance to have a “calmer” working environment and to escape from harmful working conditions. For six respondents (6/28), teleworking was proposed or requested by their employer either at the time they were hired or following closure or relocation of a work site.

As well as the reasons given to explain the move to teleworking, the discourses most characteristic of Class 1 related mainly to the effects of teleworking from home on the temporal organization of work and on the work–life balance (see Table 2).

Home-based teleworkers repeatedly mentioned the benefits associated with the elimination of commuting.

“It’s really a plus to have one and a half hours of transport less in the morning and one and a half hours less in the evening!”(Cristina)

“In the evening I’m more relaxed, less tired, less stressed, so yes, teleworking makes life at home easier”(Emma)

They also evoked the gains in terms of flexibility and autonomy in the organization an interconnection of their various activities. The benefits of teleworking at home in terms of time saved were reinvested:

- in the familial sphere:“I can take a lot more care of my son and that’s very important to me; I go to pick him up from school, I play with him, I can reconcile my career with my family; it’s a much better quality of life”(Marine)

- in the personal sphere:“I have more time for myself; I’m less stressed, less anxious; I smile more”(Gwendoline)

- and in the social sphere:“I have more time to do a lot of other things, it’s brought me closer to my friends; we try to do something at lunchtime, or go for a drink after work; so it helps me to keep good relationships”(Amandine)

Almost all the women participating in the study (14/17) devoted part of their teleworking day to quick household activities, often during ‘breaks’. Allocating time to these types of tasks was rarer in men’s discourses (4/11).

“At noon I eat quickly; I take the opportunity to do some dusting”.(Nadège)

“I’m the one that does a lot; my boyfriend does less than when I wasn’t teleworking because… of course the cleaning, the shopping; I’ve got a lot more time now, so much more that I’m the one who does all that”.(Gwendoline)

Although our study population was very small, participants’ comments suggested that teleworking at home was likely to reinforce gender inequalities in terms of the distribution of household chores.

Finally, in the discourses of the majority of participants (16/28), teleworking was seen as a source of intensification of work and extension of the working day, dimensions which were linked to difficulties in keeping an eye on the amount of time they spent at work every day.

“But actually, with teleworking, you put yourself under much more pressure; you say to yourself ‘I absolutely have to finish this tonight’ and if you don’t finish it, well you don’t feel so good […]; It’s not that it’s important; actually, more than anything, it’s that I can’t detach myself from work […]; so it’s pretty intense, teleworking, yeah”.(Nadège)

“At first, I wasn’t able to manage my work and I would work on [i.e., go on working after working hours], so in the evening after eating, I would go back at my computer […]; Above all, you shouldn’t let yourself be overwhelmed by work at any time of the day or night”.(Christian)

Echoing these remarks, the health risks associated with the increase in the temporal workload could be inferred from the participant discourses.

“You quickly get into never lifting your head [from the screen] and never taking breaks, something which you don’t do too much when you’re at work [i.e., on-site]”.(Gwendoline)

“I work more, and I take fewer breaks, and I don’t look up all day […]; either I don’t eat or I have lunch in front of my computer”.(Marine)

Furthermore, although 11 teleworkers mentioned having a separate room dedicated to teleworking, and 5 teleworkers declared they had set up a workspace in a room used for other purposes, it is important to emphasize that none of the 28 teleworkers interviewed were provided support by their company to set up a workstation. Some equipment was provided by some employers, but it was always installed by the employees.

All these findings raise questions about the increased risks of musculoskeletal disorders associated with teleworking.

4.2. Class 2—Professional Activities, Teleworkers’ Temporal Organization and Temporal Workload

Class 2 grouped together 413 ECU (14.9% of the analyzed corpus). While more characteristic of respondents who were single (χ2 = 40.45) and of male respondents (χ2 = 14.78), it did not exclude the discourses of those living with a partner or those of female respondents.

The discourse themes which most characterized this class regarded the nature of the professional activities performed during periods of teleworking from home, as well as the organization of (tele)working and (tele)workload (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Themes associated with the specific vocabulary of Class 2.

First, the content of the work and the type of activities performed while teleworking at home were relatively varied (see Table 3). They fell under the following categories: (a) communicational and relational domains (telephone calls, management of e-mails, meetings and travel); (b) research, recording and exploitation of information or data (examination/management of dossiers, data entry, conducting studies, computerized data processing, etc.); (c) production of documents (notes, summaries, reviews, reports).

It is interesting to note that teleworkers who also commuted (i.e., part-time teleworkers) distributed the work-based activities by simultaneously considering their degree of complexity and their own way of working:

“I deal with all my new dossiers when I’m teleworking, while I work on existing dossiers on-site, at the company; I keep the complicated part for when I’m teleworking”.(Catherine)

“Often I have to think about technical subjects that require a great deal of concentration; that’s why I do it when I’m teleworking”.(Antoine)

Teleworkers reported that they enjoyed significant autonomy in the way they organized their day-to-day work, in terms of the choice of activities to perform, the order these activities were carried out, and prioritizing.

“When I start in the morning, I already know what I’m going to do and how I’m going to organize myself; I have an overall view, I know what my priorities are”.(Robert)

“So, I’m the one who allocates my time, and I set my priorities according to the objectives I have […]; for example, if it’s really something urgent or if I know that it’s something that’s going to take me a long time, I will prioritize it, and if not, I’ll do it later, as I go along”.(Anthony)

The organization of work was based on different temporalities and contexts. For some participants, work was precisely defined and the objectives to achieve were set on a daily basis:

“My work arrives every morning; I have a list that comes in the morning and shows me what I have to do; but I’m the one that manages it”.(Colette)

Others seemed to have more leeway. They had to meet weekly or monthly goals:

“I’ve tasks to do during the month; I’ve deadlines, things to send back; I’ve things to do every month which are roughly on the same dates, reports to return, for example five days after the beginning of the month”.(Marie)

According to the participants, the autonomy they were given and the organization of work according to objectives set by the employer meant that depending on the period, there was a significant temporal workload that was sometimes difficult to manage.

4.3. Class 3—Work Environments, Quality of Professional Relationships and Social Representations of Teleworking

Class 3 comprised 907 ECU (32.72% of the analyzed corpus). No illustrative variable was significantly associated with this class: it therefore represented the discourse of all the interviewees.

This class was mostly characterized by (see Table 4): (a) work environments and communication-based work interactions, and (b) the quality of relationships with one’s professional sphere and colleague representations of teleworking and teleworkers.

Table 4.

Themes associated with the specific vocabulary of Class 3.

Home-based teleworkers in this class referred to all the tools and technologies they used to perform their work and to interact on a daily basis. Electronic messaging was the main daily communication tool. Synchronous communication devices (telephone, videoconferencing, instant messaging) were complementary, and were used for urgent exchanges and/or communication with close members of one’s professional sphere.

“We talk to each other by phone every day, even several times a day, and also on Zoom with team members that I’m close to; with colleagues I’m less close to, it’s a lot of emails”.(Alexis)

All 28 participants described the same characteristics at their on-site work environment. They all mentioned the greater number of interruptions, distractions and noise pollution that characterized their on-site work environment compared with their teleworking environment, and reported that the latter was more conducive to concentration.

“[when teleworking] I don’t have a phone, nobody comes to see me, it’s easier to make progress […]; I’m not disturbed and I can concentrate much more on my tasks […]; it is clearly an advantage, especially when you work in an open-plan space”.(Gwendoline)

“I find there’s better concentration when you’re teleworking, less disturbance, there’s less external interference, the bosses take up less of your time […]; when teleworking, you’re not bothered by requests; you’re constantly being asked things when you’re on site”.(Robert)

Although the majority of teleworkers also mentioned mutual aid, cooperation and the fact that their team was close-knit, they explained that remote and technology-mediated work relationships did not promote these work dimensions.

“There’s more mutual aid and cooperation on site; at home that is not possible; you can’t help someone who’s on-site”.(Catherine)

Furthermore, the discourses representative of this class highlighted that remote and technology mediated work had a negative impact on the frequency of exchanges with colleagues at work.

“[about superiors] When I’m teleworking, usually I don’t have any contact with them except when there’s something wrong”.(Leo)

“[about colleagues] We don’t call each other; we hardly ever send each other emails except if there’s an emergency; but really, when I’m teleworking, I don’t have any contact with them; we don’t have any exchanges; we don’t phone each other”.(Gwendoline)

Participants also stressed the importance of face-to-face exchanges, physical encounters and meetings, as well as the value of more informal and social moments with their professional sphere in order to maintain close relationships.

“I am less close to my operational teams; there’s a big gap there; teleworking necessarily creates a gap, or at least a bit of a distance from colleagues; when you’re teleworking, you talk less about things that aren’t work-related; there’s less confiding in people, less social interaction; you’ve less informal conversations; it’s just more formal”.(Jessica)

“[about meetings] It really allows you to create social and human links [...]; I find that seeing each other helps to defuse situations a little when they start to get a little stressful”.(Antoine)

Finally, one recurring element that emerged in interviewee discourses was the negative social representations concerning teleworking. Home-based teleworkers mentioned the stereotypes which they were the target of, whether these were conveyed by their superior or their colleagues, or whether they were more widely shared socially.

“The disadvantage of teleworking is ‘out of sight, out of mind’; I think that the further you are from your boss, the more quickly he forgets you; on the other hand, if things aren’t going well any more, he’ll check up on you […]; [About colleagues] Some have stupid ideas like ‘Yeah, you live on the French Riviera, you’re at the beach’, even though I’ve never gone swimming during a working day”.(Alexis)

“Teleworking suffers from its reputation, so socially you’re a little less well regarded and I feel that more and more […]; You still feel that there is a lack of trust in teleworking […]; Management doesn’t trust teleworkers […]; sometimes, they’ve got clichés and may think that you’re not working”.(Nadège)

4.4. Class 4—Quality of Work, Continuity of Work and Socio-Professional Integration of Teleworkers

Class 4 included 467 ECU (16.85% of the analyzed corpus) and although it was characterized more by discourses of respondents who were teleworking at home on a part-time basis, it did not exclude full-time teleworker discourses. The remarks in this class addressed the issue of the quality of the work done when teleworking from home, and the fact that permanent teleworking is possible and should be considered a norm. They also highlighted the risk of professional and social isolation inherent in working remotely (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Themes associated with the specific vocabulary of Class 4.

Among the 22 teleworkers whose discourses were significantly associated with this class, when comparing home-based teleworking with on-site working, 20 considered they performed better, 13 thought they were more “productive” and 7 reported being more efficient. Once again, differences between the on-site and home working environments were emphasized. Respondents mentioned that when they worked from home there were no requests to hamper them from performing their activities. They also mentioned distancing themselves from a social climate likely to generate stress.

“When you’re teleworking, you go full-throttle, a little more than when you’re on-site […]; it’s easier in teleworking; you’re more productive […]; when teleworking, I’m really focused on my work and I make better progress with my work […] I’m more efficient”.(Catherine)

“I am under less pressure, I work much more serenely than when I was on-site […]; in the open-plan office, I felt other people’s stress, and so I find that it’s less serene than working at home, on my own, in peace […]; there [at home], I’m more concentrated, so more productive”.(Marine)

The gains in efficiency, performance, and productivity reported by teleworkers were reinforced, in their opinion, by another benefit for the employer which is inherent in home-based teleworking. Specifically, they explained that when they were not in the best state of health, they avoided taking sick leave. Working from home, they used all the energy they had, despite feeling unwell, to get their work done.

“Because if you take sick leave while teleworking, the employer will say to you ‘yeah, but you’re at home so you can work!’. And it’s seen much more negatively, whereas if I was sick at the office, they would say to me ‘go home or you’ll give it to everyone’. From this point of view, it’s the teleworker who loses out, because he’s still going to work, even if he feels very weak; and all this so that you’re not seen in a bad light”.(Stéphane)

Finally, irrespective of whether they teleworked full time or part time, participants also mentioned a feeling of exclusion, marginalization and professional and social isolation.

“Sometimes you feel a little marginalized, and yeah, you feel a little removed from the company; you feel a little isolated, especially if you don’t go out and you stay all alone at home all day; there’s a risk of feeling lonely and depressed”.(Amandine)

5. Discussion

The objective of this study was to use an exploratory and comprehensive approach to identify and analyze the way in which home-based teleworkers define and organize their activities and professional relationships, and more broadly, the way in which they characterize telework, its positive and negative effects on work conditions and on quality of life at work and outside of work. The four classes which emerged from the lexical and morphosyntactic analysis we performed enabled the identification of the benefits, constraints and risks of teleworking.

With regard to the benefits, the working environment at home was a recurrent theme in participant discourses (Classes 3 and 4). Although rare, some studies in the field have suggested that teleworking from home constitutes a kind of alternative to the poorly perceived conditions associated with working on-site [4,7]. More specifically, it allows employees to escape from a work environment which they consider to be detrimental to being able to adequately perform their professional activities (i.e., an environment marked by interruptions, interference, requests, distractions, noise pollution, a certain degree of pressure and a climate of stress). Under these conditions, according to our study participants, teleworking fosters greater concentration, efficiency, performance and productivity. This result puts findings from previous research in this field into perspective [9,10,11,27] by demonstrating that these positive effects are not necessarily direct effects of teleworking.

The discourses of the teleworkers interviewed in our study also underlined the variety and specificity of work tasks performed at home. Specificity was particularly noticeable in the comments of part-time teleworkers who commuted to work (Class 2). These participants explained that they decided which activities they would perform when teleworking at home (vs. on-site) according to the complexity of the activity, as they perceived that working at home was more conducive to cognitive work and intellectual activities. With the exception of some qualitative studies, e.g., [48] which showed that different work activities are not equally suitable for teleworking, few studies have investigated the specific dimension of selecting and matching on-site versus teleworking tasks. Accordingly, our result needs to be verified and refined in future investigations in order to provide a more detailed contextualised understanding of work practices and teleworking arrangements. Such research is all the more important in the current context where work organizations are still trying to arrange post-COVID-19 health crisis hybrid working.

The benefits associated with home-based teleworking—not only increased autonomy, freedom and flexibility (choice of activities, ways to perform work, prioritization, duration, etc.) but improved work-life balance (Classes 1 and 2). This result reflects previous findings which revealed the positive impact of teleworking on the feeling of control over one’s working time, and the way tasks are performed, making it possible to better reconcile the multiple roles needed in daily life [13,14,15,31,43].

With regard to the constraints and risks inherent in teleworking, the first major theme that emerged from our results concerned the intensification and densification of work as well as the extension of the study participants’ working day, all of which were associated with a significant increase in the temporal workload (Classes 1 and 2). From the teleworker discourses we understand that the autonomy granted to them provided them with full responsibility over the setting of boundaries for their own working time when they were not working on-site. However, establishing these boundaries was not a simple matter. Discourses revealed the difficulties they had keeping an eye on the amount of time they spent at work every day (Class 1). Concomitantly, continuing to work, irrespective of their state of health, underlined the omnipresence of work when they worked from home (Class 4). Finally, the stereotypes and prejudices about teleworkers coming from their professional sphere reinforced their overinvestment in their work, insofar as they strove to deconstruct these same stereotypes and prejudices by working even harder (Class 3). However, there is a gap in the literature on this subject. To our knowledge, no study to date has sought to understand and identify the effects of intergroup relationships within organizations on working conditions, social cohesion and occupational health, considering teleworkers vs. on-site workers.

All of these findings lead us to question not only the effects of home-based teleworking in terms of musculoskeletal disorders (e.g., reduction in the number and duration of breaks, prolonged postures, inappropriately equipped workstations), but also in terms of psychological health (overwork, stress, work addiction, and professional burnout). Although some studies have already highlighted the deleterious effects of teleworking on workload, working time [13,14,15,27,31,32] and teleworker health [14,23,31,35], our study provides a greater understanding of the interactions of psychosocial mechanisms at work which lead to these phenomena. Our results strongly suggest the need to continue and increase research on the direct and indirect effects of teleworking on psychological health. This is especially important in the current context where the COVID-19 pandemic created anxiety-provoking and deleterious home working and living conditions [49,50].

The second major theme that emerged from our analyses of the negative effects of teleworking regards the deterioration in the quality of relationships with one’s professional sphere, specifically in terms of work groups (Class 3). Despite the variety and quality of the tools used to interact with colleagues and superiors, teleworkers mentioned a decrease in the frequency of exchanges and in the quality of relationships, less mutual assistance and cooperation, as well as a reduction in moments of socialising (e.g., informal conversations) due to the distancing of working relationships and the fact that they are technology mediated. The importance and necessity of physical encounters was very clearly highlighted in interviewee remarks. A feeling of differentiation and being marginalised (reinforced by their colleagues’ negative representations of home-based teleworking) and, more broadly, professional isolation and even social isolation also emerged from their discourses (Class 4). Although these findings reflect those already established in the literature on this field [10,12,32,36,38,39], the present study allowed us to identify the various psychosocial processes at work and how they interconnect. Identifying these processes also provides a base for reflection about the effects of home-based teleworking on organizational socialization, the transmission and sharing of information, and the knowledge and skills within organizations that implement teleworking [51]. This research topic, which has not yet been fully investigated, is particularly relevant in terms of future employees as hybrid work becomes increasingly common.

Moreover, all 28 participants—including part-time teleworkers, who were over-represented in Class 4—in our study felt disconnection and psychological alienation from the organization they worked for. This result contradicts the findings from other studies which estimated that part-time teleworking had no significant impact on professional relationships in terms of social integration into a team and more generally into an organization, e.g., [27]. Furthermore, it highlights that it is not only the proportion of time working remotely that leads to feelings of isolation and exclusion, but the very fact of working at a distance from one’s organization and colleagues [52].

Finally, our results suggest the risk of inequality in terms of the distribution of domestic tasks to the detriment of women who telework (Class 1). While gender inequalities in teleworking were particularly salient during the COVID-19 crisis [53], to our knowledge, few studies to date have compared the nature or organization of professional teleworking activities according to gender. Any future scientific research work in this field should also include gender equality in professional opportunities.

The results of this qualitative study of factors moderating the effects of teleworking (an area of research suggested by Vega et al. [11]) provide useful information for expanding the identification of some moderating factors and revealing the way in which these factors operate.

6. Limitations and Research Perspectives

The study has limitations. First, its design did not allow us to establish whether significant cause-and-effect relationships existed or to identify the weights of factors at the origin of the benefits and risks associated with teleworking. Second, the sample size was small, leading to poor study power. The results cannot be considered as representative of all teleworking situations and contexts.

Our study observations, the current literature in the field of teleworking, and, of course, our study limitations underline the importance of conducting additional empirical studies. These could focus on understanding the challenges of teleworking and its effects on teleworkers, their individual and collective working behaviour, their professional activities (content, ways to perform, to organization and to evaluate tasks, etc.), their professional relationships, their relationship to work and work organization, as well as the effects of teleworking on their quality of life and their health. From our point of view, the simultaneous use of various and complementary methods (e.g., observations, interviews, questionnaires, work tracking analysis) in a longitudinal context (i.e., questions being asked both before and after the switch to teleworking, logbooks filled in daily, weekly and/or monthly) would make it possible to objectify the evaluation of the effects of teleworking on people and on those in their professional sphere.

Similarly, if we wish to describe the impact of teleworking in spheres of life other than the professional sphere, additional studies need to be conducted using a multi-faceted approach so that the points of view of all the stakeholders involved can be recorded and analyzed. Comparative studies which differentiate teleworkers from non-teleworkers or which seek to identify the different effects of different forms of teleworking (i.e., full-time or part-time from home, in a “third place” specifically dedicated to working, or in the context of nomadic or mobile practices) could also help to better understand and explain the contrasting effects of teleworking highlighted by previous scientific work in the field.

As teleworking is likely to continue to spread throughout work organizations, especially during the current post-COVID-19 pandemic phase and in the future, it is important that the scientific community continue to develop research in this field.

7. Conclusions

On a theoretical level, our study adds to existing research in that we adopted a systemic framework. This framework allowed us to investigate the behaviours and psychosocial processes associated with teleworking. In order to obtain a greater understanding of the changes and adjustments associated with home-based teleworking, researchers must not limit themselves to examining home-based work independently of on-site work. Overall, our results show that implementing home-based teleworking involves potentially negative effects which impact temporal workload, relationship to work, communication and cooperation within teams, relationships and socio-professional integration, socialization within the employee’s organization, as well as physical and psychological health.

On a practical level, organizations must initiate a major transformation to prevent these potentially deleterious effects. This involves the development of a genuine company teleworking policy, the creation of spaces for dialogue about the conditions regarding the deployment of teleworking, the development of formal support systems for teleworkers, an evolution of managerial practices, and the redefining of the processes used for evaluating efficiency, performance and commitment [26,54]. Several authors have emphasized the need for organizations to develop concrete teleworking support and assistance policies, and the importance of establishing a climate of fairness and of non-discrimination in terms of possibilities for promotion and career advancement and in terms of work schedules, work duration, and the conditions for adequately performing professional activities [20,54]. In addition, companies would benefit from implementing human resource policies that strengthen the inclusion, identification and sense of belonging of teleworkers. Some examples are keeping everyone informed about the latest organization-wide changes, creating opportunities for connecting with members of the professional community and continuing established office traditions, and insuring that managers are attentive to teleworker concerns and difficulties. Organizational social support systems which not only encourage social interactions and trustful and supportive relationships between teleworkers and on-site workers, but also ensure that information, knowledge and skills are shared and disseminated within the organization, could help achieve such policies [21,23,24,51].

In conclusion, it is important to underline that while the knowledge resulting from scientific work in the field is able to inform and guide choices relating to the modalities of teleworking in the post-COVID-19 health crisis era, these choices are the responsibility of each organization, and must be defined collectively according to individual and group needs, requirements and constraints related to the task, activity, profession and work organization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, É.V.; methodology, É.V.; software, É.V.; validation, É.V. and C.M.-M.; formal analysis, É.V.; investigation, É.V.; resources, É.V.; data curation, É.V.; writing—original draft preparation, É.V., F.C. and A.-S.M.; writing—review and editing, É.V., F.C., A.-S.M. and N.O.; visualization, É.V., F.C., A.-S.M. and N.O.; supervision, É.V. and C.M.-M.; project administration, É.V. and C.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as the research involved anonymized records. Particular attention was paid during the collection and processing of data to ensure accordance with the European General Data Protection Regulation (RGPD-2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Athanasiadou, C.; Theriou, G. Telework: Systematic literature review and future research agenda. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vayre, E. Les incidences du télétravail sur le travailleur dans les domaines professionnel, familial et social. Trav. Hum. 2019, 82, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, T.A.; Basile, K.A.; Canónico, E. Telework: Outcomes and facilitators for employees. In The Cambridge Handbook of Technology and Employee Behavior; Landers, R.N., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 511–543. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, J.A. Managing Telework Programs Effectively. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2007, 19, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Teleworking in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Trends and Prospects. Tackling Coronavirus (COVID-19)—Browse OECD Contributions. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/teleworking-in-the-covid-19-pandemic-trends-and-prospects-72a416b6/ (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Wibowo, S.; Deng, H.; Duan, S. Understanding digital work and its use in organizations from a literature review. Pac. Asia J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2022, 14, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, M.; van Veldhoven, M. When control becomes a liability rather than an asset: Comparing home and office days among part-time teleworkers. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 1317–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Liang, J.; Roberts, J.; Ying, Z.J. Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2015, 130, 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.H.; MacDonnell, R. Is telework effective for organizations? A meta-analysis of empirical research on perceptions of telework and organizational outcomes. Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, D.; Rackensperger, T.; Dorn, D.; Wilson, N. Home is at work and work is at home: Telework and individuals who use augmentative and alternative communication. Work 2014, 48, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, R.P.; Anderson, A.J.; Kaplan, S.A. A Within-Person Examination of the Effects of Telework. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendra, R.S.; Harrison, D.A. The good, the bad and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Hopkinson, P.G.; James, P.W. A multivariate analysis of work-life balance outcomes from a large-scale telework programme. N. Technol. Work Employ. 2009, 24, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montreuil, S.; Lippel, K. Telework and occupational health: A Quebec empirical study and regulatory implications. Saf. Sci. 2003, 41, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, S.R.; Sharma, D.; Golden, T. Impact of Telework on Exhaustion and Job Engagement: A Job Demands and Job Resources Model. N. Technol. Work Employ. 2012, 27, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, L.; Halinski, M. When more is less: An examination of the relationship between hours in telework and role overload. Work 2014, 48, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Lautsch, B.A.; Eaton, S.C. Telecommuting, control and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control, and work–family effectiveness. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís, M. Moderators of telework effects on the work-family conflict and on worker performance. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 26, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, A.; Martínez, M.J.; Pérez, C. Telework and Work-Life Balance: Some Dimensions for Organisational Change. J. Workplace Rights 2012, 16, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, H.; Tummers, L.; Bekkers, V. The benefits of teleworking in the public sector: Reality or rhetoric? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2018, 39, 570–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virick, M.; DaSilva, N.; Arrington, K. Moderators of the curvilinear relation between the extent of telecommuting and job and life satisfaction: The role of performance outcome orientation and worker type. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, T.A.; Teo, S.T.T.; McLeod, L.; Tan, F.; Bosua, R.; Gloet, M. The role of organisational support in teleworker wellbeing: A socio-technical systems approach. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakrošienė, A.; Bučiūnienė, I.; Goštautaitė, B. Working from home: Characteristics and outcomes of telework. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D. Avoiding depletion in virtual work: Telework and the intervening impact of work exhaustion on commitment and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, T.W.; Payne, S.C. Overcoming telework challenges: Outcomes of successful telework strategies. Psychol. Manag. J. 2014, 17, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.E.; Kurland, N.B. A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felstead, A.; Henseke, G. Assessing the growth of remote working and its consequences for effort, well-being and work-life balance. N. Technol. Work Employ. 2017, 32, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupietta, K.; Beckmann, M. Working from Home. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2018, 70, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.; Tramontano, C.; Michailidis, E. Systematically reviewing remote e-workers’ well-being at work: A multidimensional approach. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, J.-L.; Cléach, O. Le télétravail des cadres: Entre suractivité et apprentissage de nouvelles temporalités. Sociol. Trav. 2004, 46, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, L.; Devos, V. Paradoxes from the individualization of human resource management: The case of telework. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 62, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.; Wetzels, C.; Tijdens, K.G. Telework: Timesaving or Time-Consuming? An Investigation into Actual Working Hours. J. Interdiscip. Econ. 2008, 19, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DARES. La Prévention des Risques Professionnels. Les Mesures Mises en Oeuvre par les Employeurs Publics et Privés. DARES Analyses. 2016. Available online: https://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/pdf/2016-013_v.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Taskin, L.; Edwards, P. The possibilities and limits of telework in a bureaucratic environment: Lessons from the public sector. N. Technol. Work Employ. 2007, 22, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D.; Veiga, J.F.; Dino, R. The impact of professional isolation on teleworker job performance and turnover intentions: Does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face, or having access to communication enhancing technology matter? J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spilker, M.A.; Breaugh, J.A. Potential ways to predict and manage telecommuters’ feelings of professional isolation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 131, 103646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, D.; Axtell, C. The neglect of spatial mobility in contemporary studies of work: The case of telework. N. Technol. Work Employ. 2007, 22, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilton, R.D.; Páez, A.; Scott, D.M. Why do you care what other people think? A qualitative investigation of social influence and telecommuting. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2011, 45, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Kurland, N.B. Telecommuting, professional isolation and employee development in public and private organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D. Applying technology to work: Toward a better understanding of telework. Organ. Manag. J. 2009, 6, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walrave, M.; De Bie, M. Teleworking @ Home or Close to Home? Attitudes towards and Experiences with Teleworking. Survey in Flanders, The Netherlands, Italy, Ireland & Greece; (Research Report); Université d’Anvers: Antwerp, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vayre, E.; Pignault, A. A systemic approach to interpersonal relationships and activities among French teleworkers. N. Technol. Work Employ. 2014, 29, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, M.C.; Glass, J.L. The hard truth about telecommuting. Mon. Labor Rev. 2012, 135, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, T.D.; Veiga, J.F.; Simsek, Z. Telecommuting’s differential impact on work-family conflict: Is there no place like home? J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tietze, S.; Musson, G. Recasting the home-work relationship: A case of mutual adjustment? Organ. Stud. 2005, 26, 1331–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, M. Alceste, une méthodologie d’analyse des données textuelles et une application: Aurélia de Gérard de Nerval. Bull. Méthodol. Sociol. 1990, 26, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boell, S.K.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D.; Campbell, J. Telework paradoxes and practices: The importance of the nature of work. N. Technol. Work Employ. 2016, 31, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, I.; Coelho, F.; Ferrajão, P.; Abreu, A.M. Telework and Mental Health during COVID-19. Int. J. Env. Res Public Health 2022, 19, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carillo, K.; Cachat-Rosset, G.; Marsan, J.; Saba, T.; Klarsfeld, A. Adjusting to Epidemic-Induced Telework: Empirical Insights from Teleworkers in France. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, L.; Bridoux, F.M. Telework: A challenge to knowledge transfer in organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 2503–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, L. La déspatialisation: Enjeu de gestion. Rev. Française Gest. 2010, 3, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.; Girard, V.; Guéraut, E. Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Working Mothers in France. Front. Sociol. 2021, 17, 732580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayre, E.; Devif, J.; Gachet-Mauroz, T.; Morin Messabel, C. Telework: What is at Stake for Health, Quality of Life at Work and Management Methods? In Digitalization of Work. New Spaces and New Working Times; Vayre, E., Ed.; Wiley-ISTE Ltd.: London, UK, 2022; pp. 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).