Infodemic and Fake News Turning Shift for Media: Distrust among University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Disinformation, Fake News and Social Networks

1.2. Media and Audiences

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantitative Research

2.2. Qualitative Research

3. Results

3.1. Results for the Quantitative Analysis

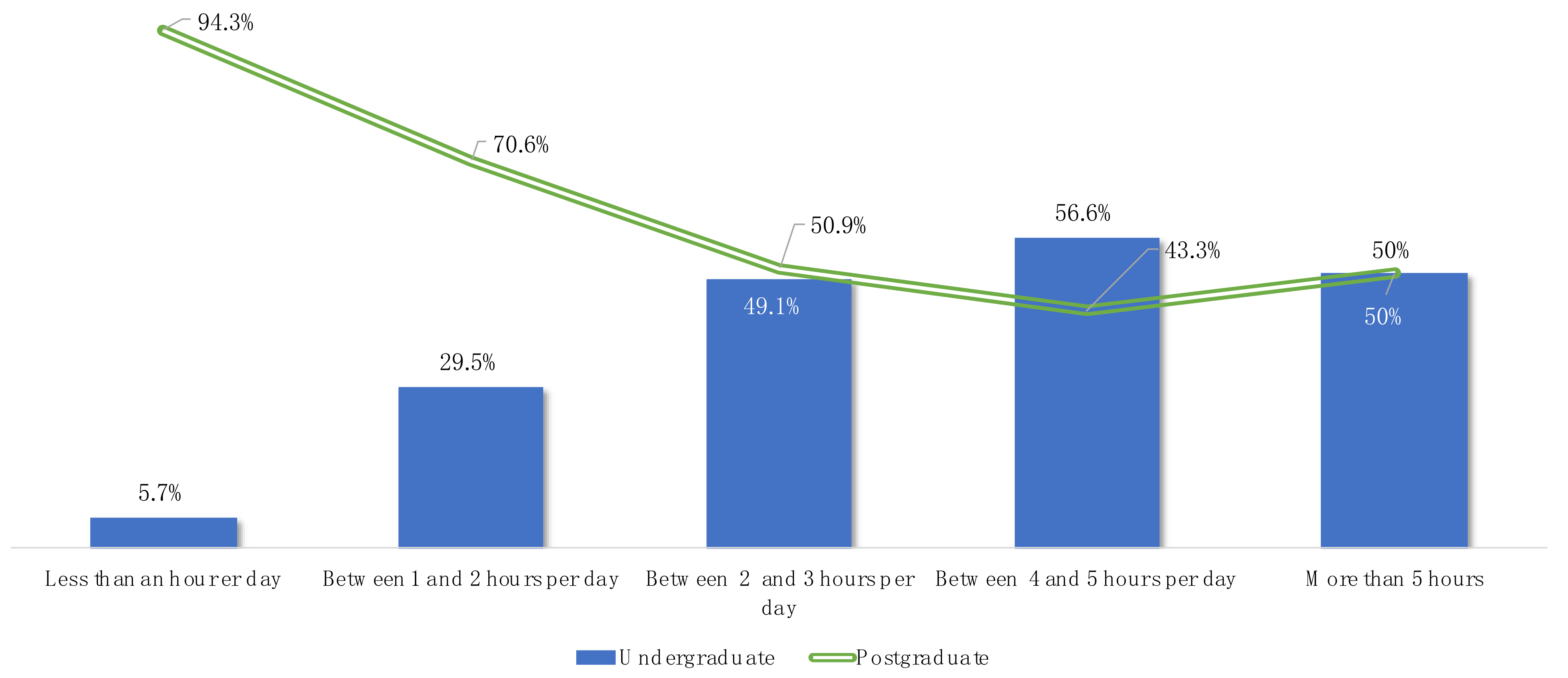

3.1.1. Social Media Use and Engagement

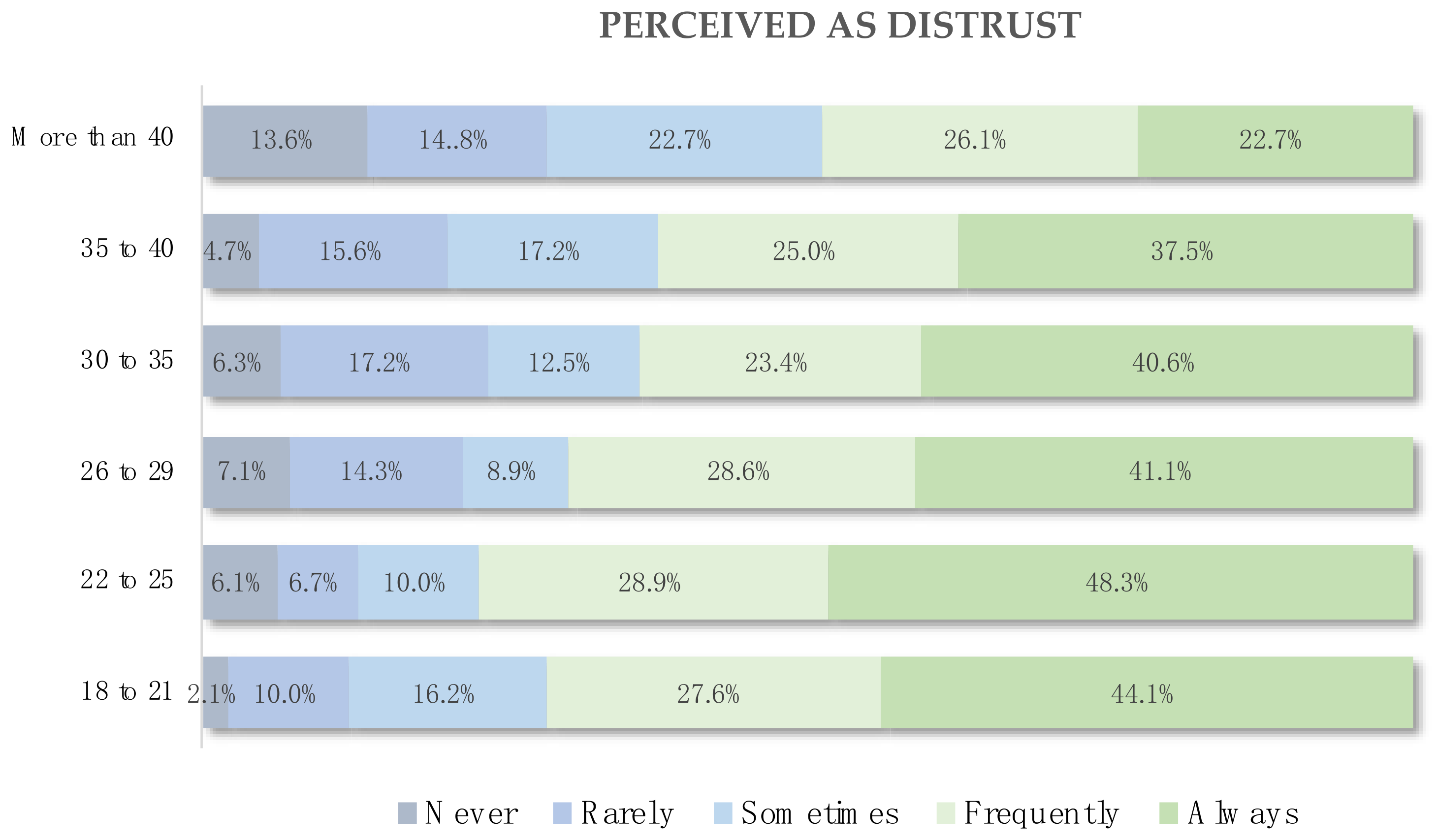

3.1.2. Fake News Perceptions

3.1.3. Trust in Media Outlets and Social Actors

3.2. Results for Qualitative Analyses

3.2.1. Overwhelmed by a Tsunami of Information

3.2.2. Distrust, Fake News and Insecurity in Media

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Casero-Ripollés, A. The impact of COVID-19 on journalism: A set of transformations in five domains. Comun. Soc. 2021, 40, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Promoting Healthy Behaviours and Mitigating the Harm from Misinformation and Disinformation. 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/3GbqeYw (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Tandoc, E.C., Jr.; Lim, Z.W.; Ling, R. Defining “Fake News”: A Typology of Scholarly Definitions. Digit. J. 2018, 6, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrero-Esteban, L.M.; Pérez-Escoda, A. Democracia y digitalización: Implicaciones éticas de la IA en la personalización de contenidos a través de interfaces de voz. RECERCA. Rev. Pensam. Anàlisi 2021, 26, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, J.; Schou, J. Post-Truth, Fake News and Democracy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Casero Ripollés, A.; García-Gordillo, M. La influencia del Periodismo en el ecosistema digital. In Cartografía de la Comunicación Postdigital: Medios y Audiencias en la Sociedad de la COVID-19; Pedrero-Esteban, L.M., Pérez-Escoda, A., Eds.; Aranzadi Thomson Reuters: Navarra, Spain, 2020; pp. 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escoda, A.; Pedrero-Esteban, L.M. Challenges for journalism facing social networks, fake news, and the distrust of Generation Z. Rev. Lat. De Comun. 2021, 79, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, N.R.; Pisa, P.S.; Lopez, M.A.; de Medeiros, D.S.V.; Mattos, D.M.F. Identifying Fake News on Social Networks Based on Natural Language Processing: Trends and Challenges. Information 2021, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.R.; Gupta, B. Multiple features based approach for automatic fake news detection on social networks using deep learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 100, 106983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasankari, S.; Vadivu, G. Tracing the fake news propagation path using social network analysis. Soft Comput. 2021, 26, 12883–12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Spezzano, F. Characterizing and predicting fake news spreaders in social networks. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2021, 13, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmo-Romero, J. Desinformación: Concepto y Perspectivas; Real Instituto El Cano: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/analisis/desinformacion-concepto-y-perspectivas/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Newman, N.; Fletcher, R. Bias, Bullshit and Lies: Audience Perspectives on Low Trust in the Media; Reuters Institute and University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Muñoz, L.; Casero-Ripollés, A. Populism Against Europe in Social Media: The Eurosceptic Discourse on Twitter in Spain, Italy, France, and United Kingdom During the Campaign of the 2019 European Parliament Election. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, R. The Post-Truth Era: Dishonesty and Deception in Contemporary Life; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Masip, P.; Suau, J.; Ruiz-Caballero, C. Percepciones sobre medios de comunicación y desinformación: Ideología y polarización en el sistema mediático español. El Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.E. Trust or Bust?: Questioning the Relationship Between Media Trust and News Attention. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2012, 56, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanitzsch, T.; Van Dalen, A.; Steindl, N. Caught in the Nexus: A Comparative and Longitudinal Analysis of Public Trust in the Press. Int. J. Press. 2017, 23, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsafati, Y. Online News Exposure and Trust in the Mainstream Media: Exploring Possible Associations. Am. Behav. Sci. 2010, 54, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Dong, H.; Popovic, A.; Sabnis, G.; Nickerson, J. Digital platforms in the news industry: How social media platforms impact traditional media news viewership. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2022, 32, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N.; Fletcher, R.; Schulz, A.; Andi, S.; Robertson, C.; Nielsen, R. Digital News Report 2021; Reuters Institute and University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2021; Available online: https://bit.ly/3Apw47e (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Loosen, W.; Reimer, J.; Hölig, S. What Journalists Want and What They Ought to Do (In)Congruences Between Journalists’ Role Conceptions and Audiences’ Expectations. J. Stud. 2020, 21, 1744–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelmann, N. Reviewing the Definitions of “Lurkers” and Some Implications for Online Research. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Pradhan, P. Trust Management. Int. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. Eng. Technol. 2020, 11, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Avilés, J.A.; Carvajal-Prieto, M.; Arias-Robles, F.; De Lara, A. Journalists’ views on innovating in the newsroom: Proposing a model of the diffusion on innovations in media outlets. J. Media Innov. 2019, 10, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoz-Aizpuru, A.; Pedrero-Esteban, L.M. Audio Storytelling Innovation in a Digital Age: The Case of Daily News Podcasts in Spain. Information 2022, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N.; Livingstone, S.; Markham, T. Media consumption and Public Engagement; Palgrave McMillan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Abdul, B.; Pérez-Escoda, A.; Núñez-Barriopedro, E. Promoting Social Media Engagement Via Branded Content Communication: A Fashion Brands Study on Instagram. Media Commun. 2022, 10, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escoda, A., Lena-Acebo; García-Ruiz, R. Digital competences for smart learning during COVID-19 in higher education students from Spain and Latin America. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2021, 40, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escoda, A.; Ortega Fernández, E.; Pedrero Esteban, L.M. Alfabetización digital para combatir las fake news: Estrategias y carencias entre los/as universitarios/as. Rev. Prism. Soc. 2022, 38, 221–243. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escoda, A.; Perlado Lamo de Espinosa, M.; Herrero de la Fuente, M. Redes sociales y AMI en la docencia universitaria: Cómo adecuar la iniciativa MIL CLICKS a las Facultades de Comunicación. Espejo Monogr. Comun. Soc. 2022, 9, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vilches, L. La Investigación en Comunicación. Métodos y Técnicas en la Era Digital; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sádaba-Chalezquer, C.; Pérez-Escoda, A. La generación “streaming” y el nuevo paradigma de la comunicación digital. In Cartografía de la Comunicación Postdigital: Medios y Audiencias en la Sociedad de la COVID-19; Pedrero-Esteban, L.M., Pérez-Escoda, A., Eds.; Aranzadi Thomson Reuters: Navarra, Spain, 2020; pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lazer, D.M.J.; Baum, M.A.; Benkler, Y.; Berinsky, A.J.; Greenhill, K.M.; Menczer, F.; Metzger, M.J.; Nyhan, B.; Pennycook, G.; Rothschild, D.; et al. The science of fake news. Science 2018, 359, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejkalová, A.N.; de Beer, A.S.; Berganza, R.; Kalyango, Y., Jr.; Amado, A.; Ozolina, L.; Láb, F.; Akhter, R.; Moreira, S.V.; Masduki, B. In media we trust journalists and institutional trust perceptions in post-authoritarian and post-totalitarian countries. J. Stud. 2017, 18, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Sampieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C.; Baptista Lucio, M.P. Metodología de la Investigación; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tsfati, Y.; Ariely, G. Individual and contextual correlates of trust in media across 44 countries. Commun. Res. 2014, 41, 760–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schranz, M.; Schneider, J.; Eisenegger, M. Media trust and media use. In Trust in Media and Journalism; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Tsfati, Y.; Cappella, J.N. Do People Watch what they Do Not Trust?: Exploring the Association between News Media Skepticism and Exposure. Commun. Res. 2003, 30, 504–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, J.M. The era of media distrust and its consequences for perceptions of political reality. In New Directions in Media and Politics; Ridout, T.N., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, K. The biggest challenge facing journalism: A lack of trust. Journalism 2018, 20, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, K.; Schützeneder, J.; García Avilés, J.A.; Valero-Pastor, J.M.; Kaltenbrunner, A.; Lugschitz, R.; Porlezza, C.; Ferri, G.; Wyss, V.; Saner, M. Examining the Most Relevant Journalism Innovations: A Comparative Analysis of Five European Countries from 2010 to 2020. J. Media 2022, 3, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Concepts | Conceptual Definition | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social media consumption | A new shift paradigm in communication field is assumed in which young people mostly consume information and interact in a digital environment fostered by social media [34]. | 9 | 0.78 |

| Fake news reception and perception | Based on the perception of consuming and receiving misleading or incorrect information that is passed off as real information [35]. | 21 | 0.86 |

| Trust | It is considered as a subjective and relational concept, built on experience or, in its absence, on the expectation that the interaction with the trustee (media) would lead to gains for the trustor (audience) [36] (p. 4). | 7 | 0.71 |

| Social Network | M | SD | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Frequently | Always | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.89 | 1.144 | 50.6% | 26.5% | 10.8% | 7.5% | 4.5% | 849 | |

| 3.63 | 1.387 | 13.0% | 9.3% | 15.9% | 25.6% | 36.3% | 849 | |

| TikTok | 1.92 | 1.31 | 58.7% | 14.6% | 9.4% | 10.4% | 6.9% | 849 |

| 2.47 | 1.415 | 33.5% | 26.7% | 12.4% | 14.1% | 13.3% | 849 | |

| 4.31 | 0.913 | 0.2% | 5.4% | 13.2% | 25.0% | 56.2% | 849 | |

| YouTube | 3.12 | 1.103 | 4.2% | 29.6% | 28.9% | 24.3% | 13.1% | 849 |

| Slot Ages | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Frequently | Always | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 21 | 48.6% | 40.8% | 41.3% | 34.8% | 34.8% | 340 |

| 22 to 25 | 24.3% | 17% | 22% | 26.7% | 26.1% | 180 |

| 26 to 29 | 8.6% | 11.9% | 13.8% | 14.9% | 21.7% | 112 |

| 30 to 35 | 7.1% | 6.2% | 7.8% | 10.6% | 6.5% | 64 |

| 35 to 40 | 2.9% | 11.6% | 4.1% | 6.2% | 4.3% | 64 |

| More than 40 | 8.6% | 12.5% | 11% | 6.8% | 6.5% | 88 |

| TOTAL | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 849 |

| Slot Ages | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Frequently | Always | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 21 | 10% | 42.4% | 26.5% | 16.5% | 4.7% | 340 |

| 22 to 25 | 9.4% | 33.3% | 26.7% | 23.9% | 6.7% | 180 |

| 26 to 29 | 5.4% | 37.5% | 26.8% | 21.4% | 8.9% | 112 |

| 30 to 35 | 7.8% | 34.4% | 26.6% | 26.6% | 4,7% | 64 |

| 35 to 40 | 3.1% | 64.1% | 14,1% | 15.6% | 3.1% | 64 |

| More than 40 | 6.8% | 50% | 27.3% | 12.5% | 3.4% | 88 |

| Total | 8.3% | 41.6% | 25.7% | 19% | 5.4% | 100% |

| N | 70 | 353 | 218 | 161 | 46 | 849 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Escoda, A. Infodemic and Fake News Turning Shift for Media: Distrust among University Students. Information 2022, 13, 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13110523

Pérez-Escoda A. Infodemic and Fake News Turning Shift for Media: Distrust among University Students. Information. 2022; 13(11):523. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13110523

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Escoda, Ana. 2022. "Infodemic and Fake News Turning Shift for Media: Distrust among University Students" Information 13, no. 11: 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13110523

APA StylePérez-Escoda, A. (2022). Infodemic and Fake News Turning Shift for Media: Distrust among University Students. Information, 13(11), 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13110523