Technology Standardization for Innovation: How Google Leverages an Open Digital Platform

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Setting

3.2. Data

3.3. Analytical Approach

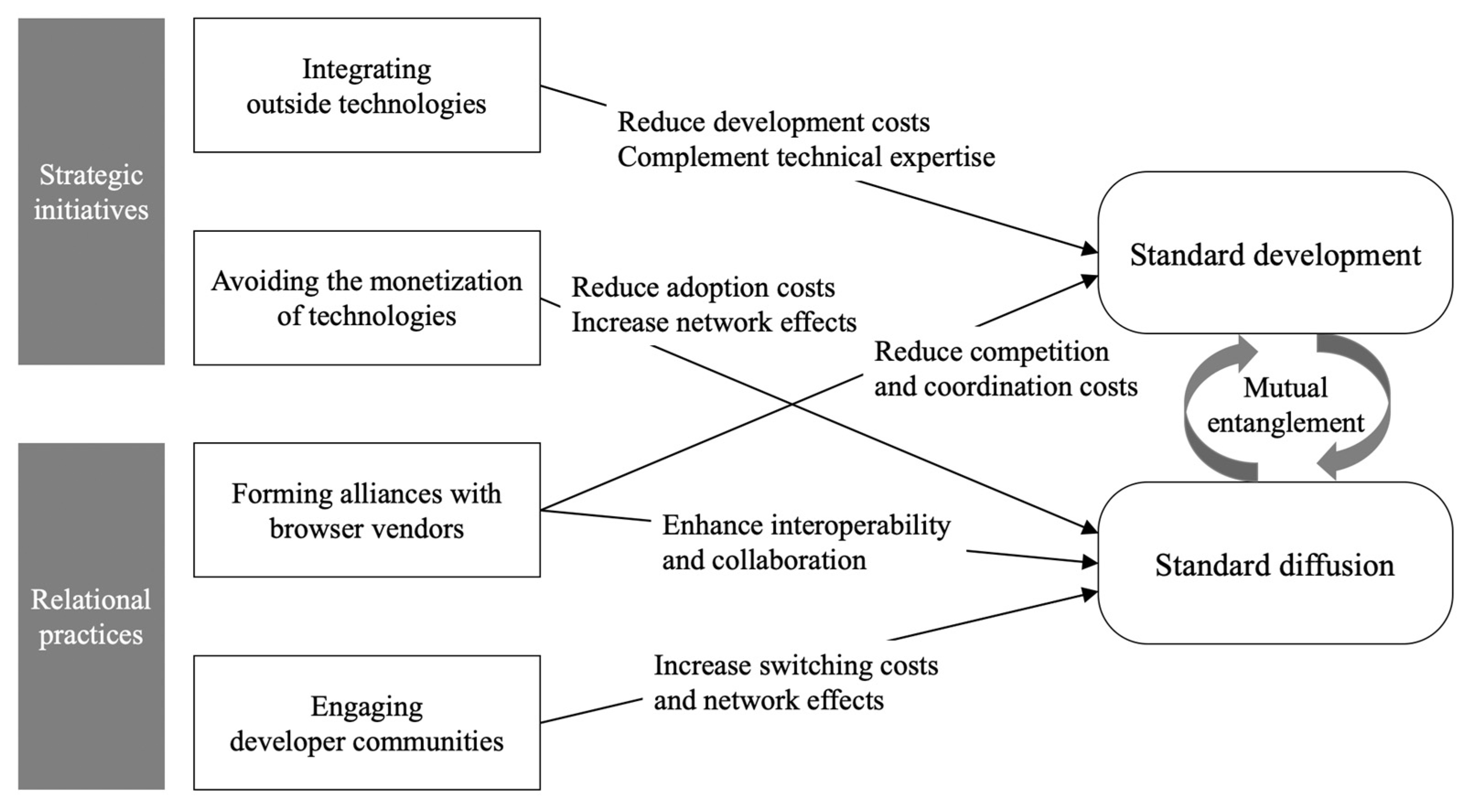

4. Results

4.1. Integrating Outside Technologies

4.2. Avoiding the Monetization of Technologies

HTML5 is a new set of proposed extensions to HTML that radically improve the capabilities of web applications. However, without implementations in a majority of browsers, these proposals remain just that, and out of reach for developers. The Gears mission is to begin implementing these APIs today, across as many browsers as possible, as quickly as possible. In this talk, I’ll explain why we are doing this, what our motives are, and show how implementing web standards is good for Google and good for the web.[39]

Yes, we are not driving forward in any meaningful way [on Gears]. We’re very focused on moving HTML5 forward, and that’s where we’re putting all of our energy.[40]

With all (application caches, IndexedDB API, File API, geolocation, notifications, and web worker APIs) this now available in HTML5, it’s finally time to say goodbye to Gears. Now that these features have all been adopted by browsers and have official W3C specs, they are available to more developers than we could have reached with Gears alone.[41]

4.3. Forming Alliances with Browser Vendors

- (1)

- backward compatibility with a clear migration path;

- (2)

- well-defined error handling;

- (3)

- no exposure of users to authoring errors;

- (4)

- open process [42].

4.4. Engaging Developer Communities

We tried to make as many engineers use Google’s technologies as possible and encouraged them to post blog entries about their technologies.[An executive of Abidarma, Inc.]

I have obtained knowhow on managing grassroots engineering communities at meetings of API Experts. I think that Google and I obtain a mutual benefit, and therefore my employer allows me to participate in this program. I feel that I have contributed to my employer through this program.[An engineer of NTT Communications]

With the work that we’re doing with Internet Explorer, we’re trying to make that a whole lot simpler for you. With Internet Explorer 9, we made our focus on a couple of things: No. 1, doing HTML5—standards-based HTML5—really, really, really well. And No. 2, asking the question: How do we improve on the user experience for HTML5 applications based upon the fact that we know Internet Explorer runs on Windows?[44]

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiegmann, P.M.; de Vries, H.J.; Blind, K. Multi-Mode Standardisation: A Critical Review and a Research Agenda. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 1370–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Kumaraswamy, A. Changing Competitive Dynamics in Network Industries: An Exploration of Sun Microsystems’ Open Systems Strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blind, K.; Petersen, S.S.; Riillo, C.A.F. The Impact of Standards and Regulation on Innovation in Uncertain Markets. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, N.; Dai, Q.; Walden, E.A. The More, the Merrier? How the Number of Partners in a Standard-Setting Initiative Affects Shareholder’s Risk and Return. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fukami, Y.; Shimizu, T. Innovating through standardization: How Google leverages the value of open digital platforms. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Second Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 29 June 2018; pp. 2273–2285. [Google Scholar]

- Garud, R.; Jain, S.; Kumaraswamy, A. Institutional Entrepreneurship in the Sponsorship of Common Technological Standards: The Case of Sun Microsystems and Java. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 196–214. [Google Scholar]

- Backhouse, J.; Hsu, C.W.; Silva, L. Circuits of Power in Creating de Jure Standards: Shaping an International Information Systems Security Standard. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, M.L.; Steinfield, C.W.; Wigand, R.T. Industry-Wide Information Systems Standardization as Collective Action: The Case of the U.S. Residential Mortgage Industry. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nickerson, J.V.; zur Muehlen, M. The Ecology of Standards Processes: Insights from Internet Standard Making. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, R.J.; McAndrews, J.; Wang, Y.M. Opening the “Black Box” of Network Externalities in Network Adoption. Inf. Syst. Res. 2000, 11, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Kraemer, K.L.; Gurbaxani, V.; Xu, S.X. Migration To Open-Standard Interorganizational Systems: Network Effects, Switching Costs, and Path Dependency. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bala, H.; Venkatesh, V. Assimilation of Interorganizational Business Process Standards. Inf. Syst. Res. 2007, 18, 340–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hovav, A.; Patnayakuni, R.; Schuff, D. A Model of Internet Standards Adoption: The Case of IPv6. Inf. Syst. J. 2004, 14, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzel, T.; Beimborn, D.; Koenig, W. A Unified Economic Model of Standard Diffusion: The Impact of Standardization Cost, Network Effects, and Network Topology. MIS Quartely 2006, 30, 489–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botzem, S.; Dobusch, L. Standardization Cycles: A Process Perspective on the Formation and Diffusion of Transnational Standards. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 737–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uotila, J.; Keil, T.; Maula, M. Supply-Side Network Effects and the Development of Information Technology Standards. MIS Quartely 2017, 41, 1207–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Qualls, W.J.; Zeng, D. Standardization Alliance Networks, Standard-Setting Influence, and New Product Outcomes. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2020, 37, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, R.T. Understanding the Role of Digital Commons in the Web; The Making of HTML5. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1438–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrock, A.R. HTML5 and Openness in Mobile Platforms. Continuum 2014, 28, 820–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. From Sectoral Systems of Innovation to Socio-Technical Systems: Insights about Dynamics and Change from Sociology and Institutional Theory. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.A.; Greenstein, S. The Economics Of Compatibility Standards: An Introduction To Recent Research. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 1990, 1, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcoe, T. Standard Setting Committees: Consensus Governance for Shared Technology Platforms. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 305–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytinen, K.; King, J.L. Standard Making: A Critical Research Frontier for Information Systems Research. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanseth, O.; Jacucci, E.; Grisot, M.; Aanestad, M. Reflexive Standardization: Side Effects and Complexity in Standard Making. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, K.; Xia, M.; Shaw, M.J. What Motivates Firms to Contribute to Consortium-Based E-Business Standardization? J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2011, 28, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, R.; Mitchell, W.; Thomas, R.E.; Bennett, D.S.; Bruderer, E. Coalition Formation in Standard-Setting Alliances. Manag. Sci. 1995, 41, 1493–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leiponen, A.E. Competing Through Cooperation: The Organization of Standard Setting in Wireless Telecommunications. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1904–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.L.; Shapiro, C. Technology Adoption in the Presence of Network Externalities. J. Polit. Econ. 1986, 94, 822–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Oh, S. A Standards War Waged by a Developing Country: Understanding International Standard Setting from the Actor-Network Perspective. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Xia, M.; Shaw, M. An Integrated Model of Consortium-Based E-Business Standardization: Collaborative Development and Adoption with Network Externalities. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 23, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanseth, O.; Bygstad, B. Flexible Generification: ICT Standardization Strategies and Service Innovation in Health Care. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, A. Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, R.K. Case study research: Design and methods. In Applied Social Research Methods Series; Bickman, L., Rog, D.J., Eds.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani, K.R.; Panetta, J.A. The Principles of Distributed Innovation. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2007, 2, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburger, A.M.; Nalebuff, B.J. Co-Opetition; Doubleday Business: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Yoffie, D.B. Wintel: Cooperation and Conflict. Manag. Sci. 2007, 53, 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.; Chen, M.L.; Marchak, M. Google Developers Blog: Google I/O 2009—Day 1 Recap. Available online: https://developers.googleblog.com/2009/05/google-io-2009-day-1-recap.html (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Dutton, S. Chrome Dev Summit: Open Web Platform Summary. Available online: https://developers.google.com/web/updates/2014/01/Chrome-Dev-Summit-Open-Web-Platform-Summary (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Boodman, A. HTML5, Brought to You by Gears. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/io/html5-brought-to-you-by-gears (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Hachman, M. Google Gears Is Dead; Long Live HTML 5.0. Available online: http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2356492,00.asp (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Boodman, A. Stopping the Gears. Available online: http://gearsblog.blogspot.jp/2011/03/stopping-gears.html (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Mozilla; Opera. Position Paper for the W3C Workshop on Web Applications and Compound Documents. Available online: https://www.w3.org/2004/04/webapps-cdf-ws/papers/opera.html (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Lynn, L.H.; Reddy, N.M.; Aram, J.D. Linking Technology and Institutions: The Innovation Community Framework. Res. Policy 1996, 25, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballmer, S. Steve Ballmer: PDC10 (Record of Keynote at Professional Developers Conference 2010). Available online: http://news.microsoft.com/2010/10/28/steve-ballmer-pdc10/ (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Fedushko, S.; Ustyianovych, T.; Syerov, Y.; Peracek, T. User-Engagement Score and SLIs/SLOs/SLAs Measurements Correlation of e-Business Projects through Big Data Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Quantity | Detail | |

|---|---|---|

| Formal semi-structured interviews | 13 people (120 min per interview on average) | W3C staff, 3; Google staff, 5; developers, 5 |

| Meeting observation | 57 meetings | W3C department meeting, 50; W3C headquarter staff meeting, 4; W3C plenary meeting, 3 |

| Other field observations | 4 years of observations | W3C internship observation (May 2009–March 2013), HTML5j.org meeting, 20; engage with developer communities |

| W3C official published documents | 51 documents | W3C specifications; WHATWG specifications; press release |

| W3C Internal communications | 31 listservs | W3C member-only listserv; W3C internal meeting minutes; W3C public listserv |

| Media articles | 28 documents | Articles of Google and other stakeholders; blogs |

| Year | Major Events |

|---|---|

| 1999 | W3C publishes a working draft of the Modularization of XHTML (a new version of HTML). W3C updates the standardization process document (adopting implementation-oriented policy). |

| 2001 | Paul Buchheit starts the project of Gmail development at Google. |

| 2003 | Ian Hickson (Opera) submits “XHTML Module: Extensions to Form Controls” to the W3C. W3C adopts the patent-free policy. |

| 2004 | Google launches the Gmail (the first real-time Web application in the history). W3C holds the Workshop on Web Applications and Compound Documents. At the workshop, the specification proposal of the next generation HTML by Opera and Apple is rejected. The WHATWG is established by engineers at Apple, Opera, and Mozilla as an open community for Web engineers. WHATWG publishes the Web Forms 2.0 (an extension to the HTML functions). The Editor (Ian Hickson) plans to incorporate this to the W3C standardization process. |

| 2005 | Google hires Goodger and Fisher (Mozilla’s lead engineers). Google supports the development of Mozilla Firefox. Google launches the Google Maps (a key Web application to engage with other application developers). Google acquires Android Inc. (developing an operating system for mobile devices). WHATWG publishes the working draft of Web Application 1.0 (features to HTML). Google hires Ian Hickson (Editor of Web Forms 2.0 and an engineer at Opera). |

| 2006 | WHATWG starts the specification development of HTML5. Google launches Google Docs and Spreadsheets (strengthens its Web application offerings). |

| 2007 | W3C starts the new working group (the HTML5 WG) with Google, Apple, Mozilla, and Opera. Microsoft joins the HTML5 WG and sends Chris Wilson as a co-chair of the WG. Mozilla, Opera, and Apple collectively proposes the WHATWG specifications as a draft of HTML5 specifications. Microsoft launches the Silverlight (a multi-media native application, not Web application). W3C decides to adopt the WHATWG specifications as the draft of HTML5. Google launches Gears version 0.1 (add-on software for Web applications). |

| 2008 | The first working draft of HTML5 is published by W3C. (Editors: Hickson (Google) and Hyatt (Apple).) Google starts the API Expert Program for application developers. Google launches Google Chrome Beta. |

| 2009 | Google heavily promotes HTML5 at the conference (Google I/O). A HTML5 developer community (HTML5-developers-jp) is founded with the support of Google. Microsoft starts to join the development of HTML5 specifications. Microsoft asks users to update the older version of Internet Explorer (IE6) to accommodate the HTML5. |

| 2010 | Microsoft launches the Internet Explorer 9 Public Beta (HTML5-compatible). Steve Ballmer (CEO of Microsoft) makes a keynote speech on HTML5. Google hires key software engineers to promote HTML5 development (Silvia Pfeiffer at Mozilla and Chris Willson at Microsoft). |

| 2011 | All the main Web browsers (including Internet Explorer 9) becomes HTML5-compatible. The HTML5 WG calls for broad review of HTML5 (last call for working draft). |

| 2012 | W3C announces the completion of HTML5 development and moves to implementation and testing. |

| 2014 | W3C publishes an official recommendation of HTML5. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fukami, Y.; Shimizu, T. Technology Standardization for Innovation: How Google Leverages an Open Digital Platform. Information 2021, 12, 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12110441

Fukami Y, Shimizu T. Technology Standardization for Innovation: How Google Leverages an Open Digital Platform. Information. 2021; 12(11):441. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12110441

Chicago/Turabian StyleFukami, Yoshiaki, and Takumi Shimizu. 2021. "Technology Standardization for Innovation: How Google Leverages an Open Digital Platform" Information 12, no. 11: 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12110441

APA StyleFukami, Y., & Shimizu, T. (2021). Technology Standardization for Innovation: How Google Leverages an Open Digital Platform. Information, 12(11), 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12110441