Abstract

A crucial area in which information overload is experienced is news consumption. Ever increasing sources and formats are becoming available through a combination of traditional and new (digital) media, including social media. In such an information and media rich environment, understanding how people access and manage news during a global health epidemic like COVID-19 becomes even more important. The designation of the current situation as an infodemic has raised concerns about the quality, accuracy and impact of information. Instances of misinformation are commonplace due, in part, to the speed and pervasive nature of social media and messaging applications in particular. This paper reports on data collected using media diaries from 15 university students in the United Arab Emirates documenting their news consumption in April 2020. Faced with a potentially infinite amount of information and news, participants demonstrate how they are managing news overload (MNO) using a number of complementary strategies. Results show that while consumption patterns vary, all diaries indicate that users’ ability to navigate the news landscape in a way that fulfils their needs is influenced by news sources; platform reliability and verification; sharing activity; and engagement with news.

1. Introduction

“Power no longer resides in having access to information but in managing it”[1].

Statistics demonstrate the phenomenal amount of information and data available today [2]. This includes information we can access, as well as that which we are producing and sharing. Whilst, at a number of historical junctures, humans have marvelled at how much information they have created and are able to obtain, nothing compares with the existence and access to data and information in our contemporary information society. Yet, just as societies have been cautious about how much information we have had in the past, so too are commentators aware of the potential problems of information today.

“Drowning, buried, snowed under” [3]—various such expressions have been used to describe the situation of modern societies and individuals that have the infrastructure and resources (not ignoring the existence of a digital divide), that enable them to access information in a variety of forms. When the amount of information becomes difficult to process, this leads to information overload which can result in anxiety, feelings of powerlessness, loss of control [4], being overwhelmed, stressed, confused, distracted and frustrated [5]. In Bawden’s [6] earlier work, he identified with the idea that information overload may not have been rigorously researched and is not an easily measurable phenomenon. However, what more recent studies have shown is that perceptions and feelings about the amount of information a person can handle or manage are what results in the occurrence of overload. Savolainen [7] also notes that there is no consensus amongst researchers about the definition of overload or the significance of the problem. Davis (in [8]) states that information overload is mainly a social condition propagated by people which is partly caused by lack of filters or failure to apply the filters appropriately. As such, information overload is attributed not so much to the actual amount of information available, but to our inability to manage and perhaps process it. Not being able to efficiently access, manage, use and possibly disseminate this information results in feelings of information overload. Not surprisingly then, the experience of information overload varies from one person to another, and a considerable number of factors affect it. Age, gender, education, occupation, income and locality are amongst the main demographic factors that result in differing levels of information overload [9].

Just as new types of mass media increased feelings of being overloaded or overwhelmed historically, rapid developments in information and communication technology (ICT) over the past few decades have accelerated the degree to which people are experiencing overload. Firstly, ‘diversity’ of information is causing overload—the diversity of perspectives and therefore the volume of information, but also diversity in the formats through which information appears. In addition, the complexity, novelty and ubiquity of information is also adding to the potential of experiencing overload [10]. There is a perception that new ICTs, which are aimed at providing rapid and convenient access to information, are themselves responsible for a high proportion of the overload effect [4]. Thus, issues relating to the quantity and diversity of information available as well as changes in the information environment with the advent of Web 2.0 [4] are both important in examining information overload.

1.1. News Overload

Whether or not we can apply a scientific and robust method to identify and quantify information overload, several studies have shown that people recognise it as part of their everyday contexts and experiences. This is especially the case when examining news overload. Of the various types of information overload that can be experienced, news overload is arguably the one that affects a large proportion of the population. A recent Reuters Institute report [11] found that in the UK, 28% of respondents agreed that there is too much news and in the US it was 40%. “A common complaint is that users are bombarded with multiple versions of the same story or of the same alert” (p. 26). This speaks directly to Bawden’s [10] observation that diversity is represented by perspectives and platforms. Various surveys have been conducted to identify how overloaded by the news consumers feel [12] and describe experiences of “news and the overloaded consumer” [9]. Nordenson [3] writes about the findings of an in-depth study by the Associated Press, examining young adult news consumption around the world, and describes a vicious cycle of news production, consumption and avoidance. News organisations have increased their output, and this continues to grow exponentially. However, whilst the news is abundant and ubiquitous, it is causing news fatigue and people are feeling “debilitated by information overload and unsatisfying news experiences…The more overloaded or unsatisfied they were, the less effort they were willing to put in” [3] (p. 1). Subsequently, news organisations continue to produce even more output to bring consumers back through different channels and the pattern continues.

For news to fulfil its purpose and be useful it needs to be processed. However, in an age of constant, fast paced, breaking, exclusive, 24/7 news, where infinite amounts of news can be accessed, it is the processing of this news that can cause overload. Journalism has, in many instances, succumbed to the mantra of the digital era—more, faster, better—[3] but this has been at the expense of depth, context and analytical content. Colossal amounts of information, data, headlines and updates mean that we are unable to think and process much of what we are exposed to [3]. In many cases, the outcome is that we suffer from overload, experience fatigue, become passive and may finally withdraw from the news environment. Closely related to this issue in that of news avoidance, both a response to and a strategy to reduce overload. The Reuters 2019 [11] report found that, in early 2019, 32% of participants said they actively avoid the news—3 points more than when the question was last asked in 2017. News avoidance was highest in Croatia (56%) and lowest in Japan (11%). A number of factors were given in the UK to explain news avoidance, such as having an impact on mood (58%), ‘I don’t feel there is anything I can do’ (40%) and ‘can’t rely on it to be true’ (34%). The coverage of Brexit certainly affected the responses in the UK as 71% cited this as a reason for avoidance. Globally, the tendency to focus on negative events and issues could be a reason for avoiding news.

The explosion of online content has resulted in information and news overload but not everyone is affected equally or in the same way. Holton and Chyi [9] explore “how overloaded today’s news consumers feel and then consider the roles of demographics, news interest and multiplatform consumption in these feelings” (p. 619). Of the 767 survey participants, 73% “felt at least somewhat overloaded with the amount of news available today” (p. 621). Women; lower-income groups; younger people; those who did not enjoy seeking out news; and users of computers, e-readers and Facebook reported higher levels of overload. Schmitt et al. [13] found in their study that “the younger the participants were the more they reported information overload in the context of online news exposure” (p. 1159), though their results did not find any effect of gender. Dividing the possible indicators of information overload into source related predictors (online news source and time spent using it) and personal factors, the latter seemed to be the most influential in determining people’s perception of overload. Personal factors were “age, gender, motivations for news consumption, information-seeking self-efficacy as well as different online information retrieval strategies” (p. 1160). The concept of self-efficacy in the context of exposure to news relates to the “extent of positive confidence about how much a user can get news he or she wants and understands the meaning of” (p. 2). Thus, higher levels of self-efficacy can reduce overload, because of the ability to handle or manage news content. Conversely, Lee et al. [14] place less emphasis on demographics and suggest that perceived overall news overload is more likely to be determined by news topics (e.g., political or crime news) and news characteristics (e.g., ambiguity or intensity) than who the news consumer is. News enjoyment and levels of exposure to news were factors considered by York [12], whereby those who enjoyed keeping up with the news seem to be insulated from the effects of feeling overload. Here, the ability to navigate and process the deluge of news results in positive feelings and even pleasure, rather than being overwhelmed or overloaded. Whilst women in this study were also more likely to experience overload, it was older responders rather than younger ones that reported higher levels.

1.2. Coping with News in the Digital Era

As more and more news is consumed through social media [11], this has added another dimension to the existence and experiences of news overload. With an ever-increasing array of possible platforms and applications (apps), consumers reap the benefits of these new technologies, but also risk encountering several drawbacks. “We are thus faced with a paradox in contemporary news consumption, one that is expected to persist. On the one hand use of social media fuels information overload by exposing the individual to an ever-increasing barrage of news content. On the other, it has the potential to help the news consumer deal with information overload through socially mediated information selection and organisation” [15] (p. 212). Accessed predominantly via mobile devices (smartphones) and in combination with messaging apps, social media is often one of the main sources of news for many people. Around 66% of the combined sample in the Digital News Report [11] used a smartphone for news weekly with usage doubling in most countries over the last 7 years. ‘First news use’ on smartphones is generally shared between social media and messaging apps and news apps (43%), but in the UK almost half (44%) of under 35s start their news journey with social media. News content aggregators, alerts and notifications are also becoming increasingly important as people move towards customising their news feeds. However, the role and market share for social media as a news provider is definite and has increased in light of the recent pandemic. The diversity that causes information overload is only set to increase in the future, but concurrent with this are various approaches to managing information and news.

Figure 1 summarises some of the strategies that exist to manage news overload that are of relevance to the current COVID-19 situation. They have been identified in previous studies [4,7,14,15] as ways of managing and processing news and involve a number of techniques, including screening, filtering, processing and avoiding news. Ultimately, the objective of these strategies is to take control of news, allowing only that which is required by an individual to filter through and be consumed. This can occur in two distinct ways: the first relates to the news itself (production and consumption) and the second is determined by demographics (individual characteristics and experiences). These coping strategies apply during normal news consumption, but are especially relevant in times of increased media attention on a crisis, such as COVID-19, which is the focus of this paper.

Figure 1.

Strategies for managing news overload.

The always connected nature of social media means news is finding us 24 h each day, from a variety of direct and indirect sources (social media pages of news organisations, government/official organisations, notifications, apps etc.). Pentina and Tarafdar [15] list both the ways social media perpetuates, as well as mitigates, overload and demonstrate that it plays a nuanced role in online news consumption. This nuanced understanding is especially important because people have developed several strategies to reduce overload by deploying the social media itself, in particular ways. ‘Screening news stimuli’ and ‘processing and interpreting news information’ are two distinct aspects of sense-making that Pentina and Tarafdar [15] consider. The first involves determination by the news consumer of channels, sources and content of news, and the second focuses on the socially-mediated negotiation of meaning that evaluates the reliability and trustworthiness of news sources and content. They further divide these strategies for handling information overload into two sets of activities: those that reduce the amount of information, including, pruning, reducing, filtering—that is load adjustment. Secondly, activities that help to effectively process information for example sorting, ordering and prioritising so that processing is easier. Recognising the excessive amounts of information on social media, including constant news updates and pop-ups of breaking news, Park [16] examines the remedial tactics deployed to alleviate news overload focusing on news avoidance and social filtering. The degree to which either of these tactics are implemented is determined by an individuals’ self-efficacy, in this case “social media news efficacy” (p. 1). The results show that news overload leads to avoidance of news consumption and social media.

Two further strategies for coping with information overload are filtering and withdrawing [7]. By filtering, a person weeds out useless material from sources thereby focusing on the most useful content, especially in networked environments. Withdrawal involves protecting oneself from excessive bombardment of information by limiting sources to a minimum [7]. Savolainen [7] writes that in reality people adopt a combination of these two complementary strategies. This withdrawal strategy resonates with Chen and Chen’s [5] question about whether people “shut down or turn off?” as a response to being overloaded. They describe how news overload changes people’s news consumption behaviours, and that they tend to adopt strategies to control the news they consume. Their online survey of 342 American adults showed that approximately 90% felt somewhat overloaded by news and that nearly half (45.1%) reported mid-level to high-level overload. Using a multi-item measure, the study asked what attributes make up news overload and to what extent media types predict perceptions of overload. “Results showed that people are more likely to feel overloaded by the news when the use newer forms, such as mobile devices and search engines to search for news (active audience). On the contrary, watching television news led people to feel less overloaded (passive)” (p. 132). It is noteworthy that they make a distinction between mobile use/searches and online news, as the latter was not positively correlated with overload. Online news requires a different type of mental activity and engagement from the consumer. Multimedia stories in particular present data and information through text, audios, videos, visuals and graphics, and expect a certain level of interactivity from the ‘reader’. Not only are the audience processing information and learning content, but they are doing so in varying ways, which are enjoyable and interesting, increasing their motivation and, in turn, reducing negativity about the experience.

Making a distinction between different media types and platforms is essential in appreciating information and news overload. Obtaining news from the television is negatively associated with overload [15] as is the case with other traditional news media, such as print newspapers [7]. However, “the higher the level of attention participants paid to news through the newer media such as social media, smartphones and tablets, the more information overload they perceived” [17] (p. 6). This was the finding in a number of other studies [5,7,9], and links with Park’s [16] discussion about people avoiding news consumption on social media because they are overwhelmed by the excessive amount of information. Another crucial response to overload is the idea of satisficing [4,7]. This is a way of making decisions and choices that involve a consumer “taking just enough information to meet a need, rather than being overwhelmed by all of the information available: just enough information is good enough” [4] (p. 6). This decision making relates to assessing the credibility of sources—if a person limits or reduces their intake of information and news, they are more likely to home in on credible, reliable and trusted sources [15].

Just as we have become accustomed to dealing with immense amounts of information in the digital era, so too have we consciously and sub-consciously devised strategies to manage and control it. News media and ICTs have brought about the increase in availability of information and data, but these same tools can be utilised to streamline and negotiate our exposure to information, and specifically relating to news. In recent years, consumers have not needed to find news, the news has found them. Notifications, feeds and alerts that have been customised to the individuals’ needs have changed news consumption from a push to a pull model. People select what they are exposed to, and this is one example of how news exposure can, to an extent, be controlled. “Solutions to information overload…generally revolve around the principle of taking control of one’s information environment” [4] (p. 8). This consists of a variety of techniques from simple time management to critical thinking, media and digital literacy skills, self-efficacy, filtering, selecting, avoiding and ultimately shutting down or turning off [4,5,7,15].

1.3. The COVID-19 Infodemic

Being exposed to enormous amounts of news has become part of our daily existence, but the current pandemic, COVID-19, has accelerated and exaggerated this to an almost extreme degree. In the initial stages of the outbreak, online news sites were dedicated almost exclusively to coverage of the pandemic. Later, they created a COVID-19 or coronavirus section and continued to cover other local, national and international news. Not surprisingly, news use increased as people searched for information about the virus through a combination of media types [18]. The current global crisis is unprecedented because, although there have been pandemics before, none have been as mediated as this. It is for this reason that the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) Tedros Ghebreyesus stated “we’re not just fighting an epidemic, we’re fighting an infodemic” [19] and WHO launched an information platform called WHO Information Network for Epidemics (EPI-WIN). An infodemic (information epidemic) can be defined as an overload of (mis)information about a problem or crisis that makes finding a solution to the problem more challenging.

At times of crisis there is an expected peak in news use, albeit temporary, across different media types. At such times, the perception of overload could change, because people are in fact making a concerted effort to receive or consume more information and news. Conversely, extended and widespread coverage of the same event or situation can result in news fatigue. Austin et al. [20] studied the patterns of media use during a series of experimental crisis scenarios (e.g., bomb threat, riots, blizzards and disease outbreak) and found that audiences take into account both information sources (origin) and information form (type of media). Developing crisis communication theory, they demonstrate that both traditional and social media were accessed by participants but with different objectives. Traditional media (newspapers and TV news) was used primarily for education and an important characteristic used to describe it was credibility. Social media was used primarily for insider information and checking in with family/friends. What both of these media types had in common was convenience, as people accessed news from the source that was easily available or accessible in the first instance. Discussions and communications about crises were supported by social media but “once participants notice[d] a discussion trend in social media networks they [were] more likely to seek out traditional media coverage of these crises” [20] (p. 202). This is a similar finding to survey data in Nielsen et al [18] that shows not only do people have a mixed diet of news consumption (only 16% of respondents identified social media as their main source of news), but that they are also seeking ‘news’ and information from non-news organisations, such as governments, national and global health organisations, as well as scientists, doctors and health experts. Research in Canada concluded that more Canadians prefer to get their COVID-19 news from television (60%) than from social media (22%) [21].

Evidence suggests that when news is circulated through some social media accounts and particularly via messaging apps, people seek verification in traditional media (mainly newspapers and TV) [18]. One of the major issues during the COVID-19 epidemic has been the creation and dissemination of fake or false and misleading information—misinformation, disinformation or malinformation [22]. There is often misunderstanding about what each of these terms refers to and there is also overlap between them. However, at a practical level, people have an understanding of the idea as information that is inaccurate or false spread either maliciously or accidentally. During a health crisis the importance of accurate information is critical and there have been extreme consequences of incorrect information [23]. In fact, “one of the most relevant examples of this negative effect of false news can be found in the field of health” [1].

This is not the first time people have faced a media crisis alongside a health crisis (Ebola, H1N1 (bird flu), swine flu, Zika, SARS) however, a number of factors differentiate COVID-19 from previous crises, other than its obvious scale and severity. Baines and Elliot [22] propose the following initial take-aways about COVID-19:

- The infodemic is unprecedented in its size and velocity;

- Unexpected forms of false information are emerging daily;

- No global consensus exists on how best to classify the types of false messages being encountered.

During the current pandemic, various categories of misinformation have circulated relating to transmission; the effect of weather conditions, and; prevention and treatment/cure [5]. Brennen et al. [24] undertook a systematic content analysis of 225 fact-checked claims in social media data and analysed the types, sources and claims about COVID-19 misinformation. They found that reconfigured (spun, twisted, recontextualised and reworked) information is much more common than completely fabricated information in social media (87% compared to 12%). They show that both top-down (prominent figures) and bottom-up (ordinary people) misinformation is circulating and that the single largest (39%) misleading or false claim about COVID-19 is about the actions or policies of public authorities (including governments, WHO and the UN). In addition, several misleading rumours and conspiracy theories have also circulated about the origins of the virus [25] and research has shown that political orientation and right-leaning media can influence perceptions and facilitate misinformation about COVID-19 [26,27]. The director of Infections Hazards Management at WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme spoke about a ‘tsunami’ of information that accompanies every outbreak which brings in it, misinformation and rumours. “But the difference now with social media is that this phenomenon is amplified, it goes faster and further” like the virus itself, and this is what poses a new challenge [28]. Numerous commentators have echoed this idea by describing the infodemic as “a McLuhanesque disease: its symptoms are rumours and responses that spread across the global village in minutes” [29]; containing “misinformation that circumnavigates the planet in microseconds…[who’s] impact can be devastating” [30]; and, involving “the blazing spread of misinformation, lies and rumours” [31]. Counter information, myth-busting and fact-checking are seen as effective ways to stop the spread of this inaccurate information, but if this is not disseminated in a timely manner, the void that it leaves is easily and quickly filled with rumours and unsubstantiated claims. WHO has been at the forefront of dealing with the infodemic through several initiatives. They have also joined forces with media organisations, especially social media platforms, to raise awareness, direct people to reliable sources and provide evidence-based answers. Social media companies have also taken steps, although some would argue too little too late [32], to reduce the amount of false information being posted and spread on their platforms.

2. Methods

The data for the study was collected using media diaries and the research was framed within the practice of ethnography [33]. Solicited diaries are part of a research process, in which selected informants record and reflect on their own actions and experiences [34]. As a qualitative research method, this would enable the collection of detailed information about people’s news consumption habits and provide opportunities for informants to describe experiences using their own frames of reference. The objective was to understand media consumption habits relating to news (and information) about COVID-19. Fifteen participants completed a 7-day diary (any time between 7–20th April 2020), in which they documented all the media content they were exposed to or accessed in both traditional and new media, including social media. This could have been accessed on any device; available in English or Arabic; include reading, listening or viewing. An additional section on sharing was inserted because of the anticipated high levels of social media usage. Instructions were given to participants and some responded with sample entries via email to confirm the requirements before proceeding to complete the diary. However, there was still potential for instructions to be interpreted in different ways. Participants were paid for their diaries. Appendix A shows the diary template.

The diaries were structured [34] and participants were encouraged to complete entries synchronously, or at least at regular time intervals to ensure accuracy. The diary was initially for 10 days, but after some negotiation with participants it was reduced to 7, with the objective of minimising participant burden [35] and the probability of incomplete diaries or participants dropping out. It was better to obtain more comprehensive information regarding media use for 7 days, rather than extending the time to 10 days. This way quality of information rather than quantity is stressed, and participants were also given flexibility about when their 7 days started. The advantages of diary research are that it is a more natural way of collecting data using the respondents’ own language, so that the researcher can see the world through his/her eyes [33]) and yields greater detail about media habits [33]. Diaries reduce the probability of forgetting, ignoring or recalling inaccurate information because of the immediacy of data gathering [36], as well as ensuring distance between researcher and diarist, enabling greater autonomy and less pressure to give ‘correct’ answers during an interview [34].

One of the disadvantages of using the media diary method is that it requires a considerable amount of input and commitment from diarists as it is time-consuming. Even if respondents begin well, they may lose interest and motivation or fill in details intermittently. Berg and Düvel [37] note that being a tool for quantitative data collection, the diary often fails to “deliver details on how and why people engage in particular (communicative) activities and how they access them” (p. 7). In order to overcome this issue, participants were sent a follow-up reflective exercise, in which they were asked questions about patterns of use, overload, management, avoidance and the infodemic (see Appendix B). Combining the two documents generated data that could be tabulated, though not representative, as well as reflexive and expressive. Using the two corresponding types of data provided a snapshot of media use by the cohort in the study.

Data was analysed manually by tabulating each reference in the media diaries according to source and platform. In addition, coding was used to identify sharing activity, as these three variables formed the main column headings in the media diary template. A further question was asked about device use via email. Similarly, reflective exercises were manually coded for responses about information and news; infodemic: fake or false information/news; overload; and avoidance. Evidence and examples are taken from the data to report on these themes, and these are connected to other studies in the field [33]. The study thus examines data collected from media diaries and focuses on news consumption patterns; reports on how participants have engaged with; and managed news at a time when receiving and processing information is critical. Whilst not a large-scale study, it provides useful information about how news overload is managed by a cohort that is frequently associated with particular news media and ICT habits. It is an exploratory study that is related to a broader project assessing digital literacy practices of undergraduate students in the UAE. The findings about digital literacy are reported elsewhere [38], but this paper focuses on news overload.

Participants

The participants in this study were 15 undergraduate (or recently graduated) students at a university in the Gulf state of the United Arab Emirates (UAE). They were aged between 18–25, 11 were female and 4 were male. This is a fairly accurate representation of the gender balance at the university (80% female and 20% male), and whilst the group was not homogeneous, several characteristics and demographics were shared by them and the rest of the university population, including experiences of ICTs and use of digital technology. All students were in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, with the exception of one from Science and another from Education. A number of them were studying Political Science, and were mainly students of the researcher, either current or past, on a media writing course. Whilst there was no connection to this research and their undergraduate studies, there may have been some bias, due to the relationship with students adjusting their diary entries to reflect what they felt were more acceptable sources or stories. All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion in the research before they were sent the media diary and reflection exercise to complete. Sixteen female and ten male students were invited to take part in the research from the highest achieving students (highest GPA), as a way of ensuring they could manage both their studies and the completion of the diaries. Informal discussions took place prior to commencing the work, in order to ensure students understood what was involved and expected of them. Those who were comfortable and confident agreed to proceed and there was no pressure or obligation to do so. Whilst there may be potential to cause feelings of anxiety about overload by participating in such a study, these students were not considered vulnerable in any way and the research connected well with the course they were already enrolled in (Writing for the Media), which involved continuous engagement with the news media. A number of respondents mentioned that they had enjoyed and benefited from taking part in the study as it enabled them to think about their own media use. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the College Ethics Committee for project G00002655.

Research by Head et al. [39] shows that students are a group that are exposed to and engaging with news from the moment they wake and throughout the day, both in a private and educational context. Their pathways to news vary and do not consist of social media alone—a stereotype often associated with younger consumers. They are both multimodal (a blend of headlines, stories, videos, alerts, online) and multisocial (different social platforms as well as face-to-face). The participants in this research were chosen because they display the same demographics and characteristics, albeit in a different setting, and the timing of the study provides an opportunity to examine news consumption behaviour in an unusual (infodemic) context. Furthermore, it is often young people in several studies cited above who are seen as suffering disproportionately from news overload, and this research enables us to assess the extent to which this applies to the respondents in this study. Finally, access to participants was assured because of the relationship between the researcher and the researched.

3. Results

It would be unusual if, at the time of such a global crisis as COVID-19, people were not accessing news to a greater extent than normal. Furthermore, the changes in daily routines meant that, apart from the need to be informed, people had much more time available to them to be able to consume news, because of the lockdown [40]. The results from the media diaries show that, whilst all participants were consuming news about COVID-19, the amounts varied. Clearly, some people were more active news consumers, whilst others appeared to be accessing more moderate or essential amounts to stay informed. Of the individual entries for daily consumption, the highest was 21 and the lowest was 1 (excluding days on which news was avoided altogether). Some participants had a routine of checking news both in terms of times and sources, whilst others were consuming in a more unstructured manner, possibly reflecting routines prior to the pandemic. In describing his pattern of media use, one male participant noted: “Consistent. Every day, I use almost the same sources and the same time. But [in this] latest period, because of the pandemic the content I consume differs from my regular interest”. At the other end of the spectrum, a female described her pattern as “very diverse”. The fewest number of entries in an media diary was 7 and the highest was 102. Subsequently, the total time spent on news relating to COVID-19 for the 7-day period varied significantly from 23 to 966 minutes (just over 16 h).

Table 1 shows the ‘traditional’ sources (now predominantly accessed online) for news that participants were using by frequency. Every entry was included in this analysis, and the most frequently accessed are represented here demonstrating a preference for well known, well established and trusted sources—both national and international.

Table 1.

Most frequently used sources.

Looking specifically at social media accounts, Table 2 shows the most frequently used. All of these accounts belong to government bodies or official media organisations. It is worth noting that across the total of 284 entries for social media, there is considerable variety, with some accounts (48) only being used once.

Table 2.

Most frequently accessed social media accounts (by platform).

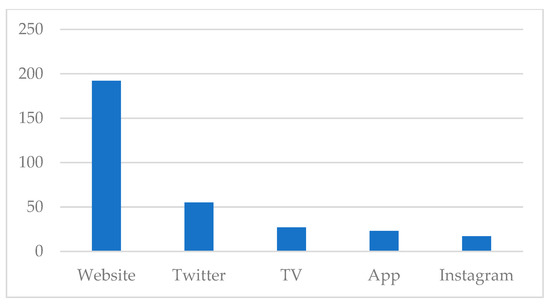

How all media sources were accessed (by top 5 platforms) is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Top five platforms used to access all media.

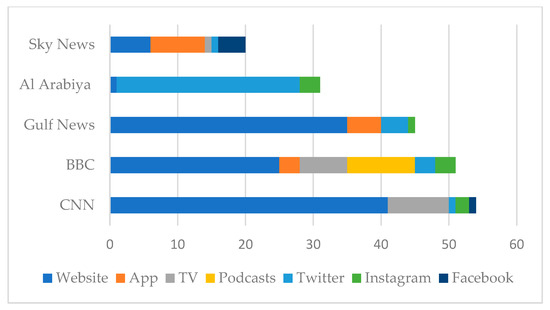

Websites were one of the most popular platforms for accessing news and this is not surprising when we correlate this with device use. Laptops were the most frequently cited as the best device to use for longer news stories which are mainly produced by the top sources. Figure 3 shows a detailed breakdown of the top five traditional sources by platform.

Figure 3.

Top five traditional sources by platform.

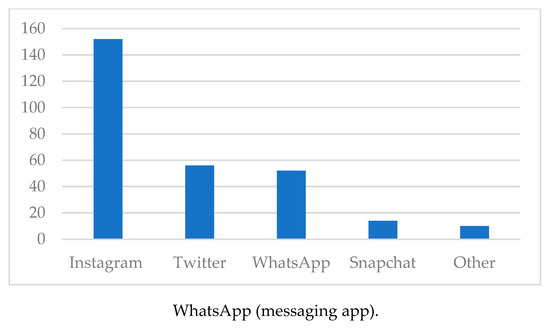

Across the total range of sources, social media was a popular way of accessing news, as shown in Figure 4, with Instagram being by far the most used.

Figure 4.

Most popular social media platforms.

Platform use shows that both traditional and new/social media are being used and participants have a multi-platform approach but social media (284) and online access (192) are the most popular. Device use demonstrates that news is consumed primarily on smartphones (14) and laptops (10) (see Table 3). The smartphone is often the ‘first news use’ device, after which laptops were utilised to read the full story in detail or to search for further information relating to the story. The follow up section in the media diaries shows this is done for a number of stories that readers are interested to know more about. Alerts and notifications compose a fair proportion of this first contact for news and use of apps means sources such as BBC are initially accessed on smartphones.

Table 3.

Device use (primary and secondary).

Sharing activity showed no obvious or consistent pattern, either for individual participants or between the sample. However, some media diaries showed considerable amounts of sharing, for example, one female who read/watched 16 news items, shared 12 of them. Sharing was done in both traditional ways (calling mum and sister on the phone) and through the more expected methods (Instagram, Snapchat and WhatsApp). Some would share based on the location of the story, e.g., a story about the USA would be sent to a friend there, because it was deemed to be of interest.

Much of the sharing was done with either individual family members (including grandmothers) or via a family group. Interestingly, several references were made to offline sharing—that is, discussions that took place face to face about news that had been received or shared. The following comments demonstrate this; “called my mum to watch with me” or “did not share link on social media but did discuss the number of cases and current situation during breakfast with my dad who works at the police”. As a simple classification, there were some ‘heavy’ sharers, who probably shared up to 80% of the news they consumed, then, there were those who shared the occasional item (one or two, and only one male participant who did not share anything at all), and the rest of the diarists were somewhere in between sharing about 40–60% (not exact calculations) of items. The tendency to share information and news would have increased significantly during the COVID-19 period because of the nature of the crisis. Even if people were previously not inclined to share news, they would have done so as a social responsibility.

Table 4 shows the attitudes and the experiences of news and information during the crisis in response to questions 5, 8 and 9 in the reflection exercise. Whilst they are not statistically significant, they clearly represent negative aspects of news consumption and are likely to influence each other. “Only in this period I avoid the news because it will effect [sic] my mental [state] and my studies” or “it is good to stay updated but sometimes seeing such news all the time can be exhausting and brings negativity”. When asked their opinion about the amount of information they have been exposed to during COVID-19, respondents used the following words; immense, huge, enormous, a lot, more than, enough, many details, massive, many leads, too much and so much, indicating that the volume of material has been extraordinarily large compared to any other time. One respondent wrote, “I think COVID-19 will go down as ‘the most written about subject in journalism history’”. Most of the descriptions of fake or false news related to prevention and cures for the virus (“weird information about how to protect yourself”); numbers of cases and deaths; and rumours about people who were thought to be infected. There was also an example of a video that was circulating in social media, but it was in fact unrelated to COVID-19.

Table 4.

Ignore/avoid; overload; fake/false information.

Two questions (Q6 & Q7) asked the participants to think about the concept of an infodemic. The first was to gauge whether they had heard of the term and the second to understand whether they felt we were currently experiencing an infodemic. Eight people had heard of the word, four had not and three found a meaning for it online. One participant, the only one to include BBC podcasts in his diary, said it was discussed in one of the podcasts.

Only one respondent felt that we were currently not experiencing an infodemic; 11 believed we were, and three others wrote about related issues. A secondary aspect of this question asked whether individuals had been able to manage news and information during this period and responses were evenly split for those who answered. Five people said ‘yes’ they had been able to manage and seven said they had not although some method of management or control was apparent in most diaries. Details of these management strategies and experiences are given in the Discussion.

4. Discussion

The data obtained for this study has presented an understanding of how an extreme example of information and news overload has been experienced in the digital media environment. By referring to the findings of previous studies and strategies in the literature, the discussion will explore how participants are managing news overload by implementing different techniques; using existing media knowledge and ICT skills to make informed decisions; and developing coping strategies. These ‘managing news overload’ (MNO) strategies are similar to those utilised by participants in a number of previous studies.

4.1. MNO by Source

The first decision that participants had taken was to access credible, reliable sources. Table 1 consists of global names in the news world—CNN, BBC, Sky News, as well as national newspapers Gulf News and Khaleej Times. As a source-related factor [13], choosing certain news outlets and organisations ensures consumers are receiving credible news. By doing so they are withdrawing and “keeping the number of daily information sources at a minimum in order to shelter ... from excessive bombardment of information” [7]. A number of media diaries showed use of TV as a news source reflecting the findings of Nielsen et al. [18] and the Reuters Digital News Report for 2020 [41]. This was unusual for the young sample who are normally associated with new and social media and supports the proposition that they are realigning their sources to include traditional, more reputable ones [11]. It may also reflect the changing domestic dynamics in which families are together during lockdown and family TV viewing has increased (for both English and Arabic news). This increase in TV as a news source does not detract from the considerable increase in social media usage. However, within this social media usage, people were relying on a number of official or government accounts, such as Abu Dhabi Police. There was also a clear pattern of using local and international health organisations (social media accounts and websites) to access information and news (such as the Omani, Bahraini, Iranian and Lebanese Health Ministries; Cleveland Hospital; and the Italian Medical Association) a similar finding to other, large scale studies [18,40].

The results of this study demonstrate that both information source (where the crisis information originates from) and information forms (how the information is transmitted) [20] are both critical in decisions people make about keeping informed. This decision process whereby consumers are carefully selecting their sources is the first and most obvious way to manage overload. The ‘more and faster is better’ model is not being adopted because fewer, high quality, trusted sources are in fact more useful for well-informed individuals. The following quotes from reflections emphasise the importance of MNO by source:

- “I was able to manage between the news and misleading news that was spreading. Since you depend on credible sources, you will never believe WhatsApp or social media news”.

- “I only read from credible sources and valid news websites and avoid those with no sources”.

- “I have been able to manage the news information by reading from reliable sources”.

4.2. MNO by Inter-Platform Verification

One of the critical aspects of the COVID-19 crisis has been the issue of misinformation. The existence of misinformation (real and perceived) is directly related to feelings of overload and, because so much information and news has been produced, processing it has become overwhelming. Patterns in the media diaries show that participants are filtering the amount of news they actually read by using a process of inter-platform verification. As much of the news is received via social media, they then refer to traditional media sources (including websites) for verification. Rather than read the initial news post on the social media platforms, they are often searching for it on the world wide web, and only reading it if it has been reported on in a trusted newspaper or TV channel. This process helps with reducing overload because information that is regarded as surplus, due to its unreliability, filters out a percentage of the news. The extensive use of messaging apps, mainly WhatsApp (compare to [11]) has also contributed to circulation of misinformation, which has resulted in fatigue: a symptom of overload. Of the media diary entries related to ignoring news, most were those sent via WhatsApp, either from individuals or group chats (including voice messages), and this trend was confirmed by notes made in the reflection exercise. A total of 59% of respondents in a Canadian survey stated that they encountered COVID-19 misinformation on messaging apps at least sometimes [21] and Nielsen et al. [18] found that concern for misinformation is focused on social media and messaging apps.

The original source of news in WhatsApp messages was not mentioned in most cases, but participants made an informed decision (depending on claims, content, previous knowledge, feeling etc.) about whether the news seemed believable. Depending on this they would decide what action to take. Social media, on the other hand, was not associated with such levels of mistrust or perceived misinformation in the media diaries. The reason for this is probably because Instagram accounts were for government institutions, news media organisations or other trusted sources and Twitter, which was not used as extensively, was also linked to credible sources (27 tweets for Al Arabiya News).

An interesting relationship in this inter-platform verification was that whilst it is not unexpected that consumers were moving between messaging apps (WhatsApp) and traditional media, they were sometimes moving from messaging apps to social media to check the accuracy of news. Examples of these patterns are given in Table 5 and are similar to ‘information searching efficiency’, which helps in alleviating the likelihood of encountering information overload [42].

Table 5.

Examples of inter-platform verification.

Related to this inter-platform aspect of MNO are choices regarding device use. The two most frequently used devices were the smartphone and laptop—not an unusual pattern for the younger cohort in this study. What is apparent though is that this device use acts as another layer of filtering and managing news content. News apps and notifications from social media platforms were received on the smartphone—“I check my phone first because it is always with me”. At this stage, participants decided whether or not to follow up the story on the laptop stating that they did so to read stories in detail and watch longer videos. In this way MNO by device use can also be added to the way respondents are streamlining news content that they actually want to engage with.

4.3. MNO by Sharing/Not Sharing

The key function of social media, to share information, has become even more prominent during the COVID-19 crisis for both private/personal contacts and among formal/official networks. Data from the media diaries shows a considerable amount of sharing of news and information, but what it also reveals is that people are consciously not sharing. They are acting as social filters [10] to reduce the amount of false or dubious news passed on to others. By recognising the questionable nature of news, they are not only protecting themselves from it and, thus, from the related overload, but they are also acting as gatekeepers for others. Similar behaviour has been identified in other studies [7,10]. In Newman et al. [11], on average 29% of survey respondents said they decided not to share a ‘dubious’ news article (35% USA, 61% Brazil, 40% Taiwan and 13% Netherlands, but this was not during COVID-19). When analysing false and evidence-based information during COVID-19, Pulido et al. [1] show that false information is tweeted more but retweeted less than source-based or fact-checking tweets, pointing to increased levels of awareness during a health emergency, especially because so much debate about the dangers of misinformation has been taking place.

Numerous entries in the media diaries note that posts or messages (in particular) were not read or shared, and often deleted. This pattern demonstrates that participants are applying their knowledge and critical thinking to the news they are receiving rather than circulating it without any thought. With increasing attention on false information or misinformation and responses from social media platforms to tackle the issue (Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp, amongst others, have responded to these problems with various initiatives often in collaboration with WHO [31]), there is much greater awareness amongst the general public. In the UAE, this has been increased even further because of legislation against the sharing of unsubstantiated or potentially false information [43]. Table 6 illustrates some examples of sharing/not sharing that participants reported on.

Table 6.

Examples of sharing activity.

4.4. Limitations and Further Research

A number of limitations exist in this research study and its findings. The first of these is that this is an exploratory study, with the data analysed collected from only 15 diaries. As such, it is not possible to see the results as being representative of undergraduate Emirati students, or indeed even undergraduate students at this institution. Only by increasing the sample size could generalisations be made. The findings can, however, be considered preliminary research, which has the potential to be developed further in terms of the sample size, as well as probing for details and depth in areas that are of greatest significance in determining overload. A number of studies cited here have examined particular characteristics of respondents, in order to determine whether these affect their experiences of overload (for example, demographic factors). The natural progression from this research to a larger scale study would be to include a sizeable sample in which these factors can be correlated against feelings of overload. While there were some indications that source and platform usage link with overload and misinformation, greater confidence in the findings could be achieved through identifying a statistically significant correlation between those factors. A larger sample size may also provide a clearer understanding of how a range of other variables, such as current academic discipline; prior educational experiences and language of instruction; knowledge or training in media or information literacy; or self-efficacy have an impact on managing overload.

It is also of note that the media diaries analysed did not record other types of news consumption (though the likelihood of reading non-COVID-19 news was probably low), neither did they provide details of other media consumption (entertainment). Had the diaries been kept for a longer period or all news consumption been included the data set would have been richer. Notwithstanding these limitations, many of the findings relating to news overload are the same as those for larger scale national and international studies, and contribute to our understanding of how young people are employing different techniques and strategies to manage their news media consumption and are taking measures to reduce the feelings and effects of overload.

An aspect of this research that can be explored further is understanding the relationship between UAE’s media landscape and experiences of news overload. The government has been proactive in managing information and controlling misinformation (‘say no to rumours’ and a link to WHO’s myth-busting page on its portal [44]). Study participants were aware of the initiatives being taken by the government, including imposing fines and temporary imprisonment for those found guilty of circulating fake news [45]. They were also aware that the government has been monitoring social media to combat false or misleading information and reduce its negative impact. Media diary entries show that students have been conscious of using official government sources and so, examining news use and overload in this context would provide an interesting case study, which could be compared to other countries, both with similar media environments as well as with those that differ.

5. Conclusions

Studying information and news overload during the current global outbreak may in fact give rise to two paradoxical consequences. Firstly, the proportion of the world’s population that is connected to digital networks is being exposed to tremendous amounts of information—written, audio-visual, graphic, data journalism, multimedia etc. Some of these news consumers are choosing to switch off and avoid this deluge altogether. Conversely, it is a time when many news consumers are purposefully increasing the amount of news and information they can access. Keeping informed and up-to-date can in extreme circumstances be a matter of life or death. Both of these scenarios can lead to feelings and experiences of news overload. In the first case, people are deciding to remove themselves from the news environment—perhaps only for a short period, and almost certainly on a temporary basis. They may be choosing to focus only on a limited number of sources, so as to alleviate the burden of news overload, especially in light of the intensity and focus on news about COVID-19 for the first few weeks of the outbreak. People may have felt overwhelmed, due to the similarity of all news stories and the intensity of reporting on one issue. “The flow of information is massive about this pandemic. It’s hard to spot any information that does not have a connection to coronavirus. Scrolling through my feed in Instagram will have all sources of information… which is a bit of overkill” and “it has been stressful because I would get so many notifications, posts, articles sent to me on a daily basis this past month only about the virus… for a while the information just kept repeating and I was bored of hearing the same thing”.

In the second instance, people are seeking out more and more information as anxiety and uncertainty about the disease has left a void in our understanding, thus creating in the most extreme cases, the possibility of cyberchondria. Cyberchondria is defined as constant online searching for health information which is fuelled by an underlying worry about health that results in increased anxiety (Starcevic and Berle, 2013 in [46]). Eventually, this self-exposure to information can result in overload. Ultimately, news consumers need to manage news overload by striking a balance between the need to be informed about the virus, its impact and how to respond to it, and being overwhelmed by excessive, unnecessary and irrelevant information and news. Media refusal/resistance, news avoidance and selective scanning are possible behavioural responses to information overload [14] and coping strategies that help with managing, processing and using the information and news effectively. Participants in this study made decisions that resulted in coping behaviours and strategies to manage news overload. Thus, whilst all except one said they believed this was a time of information overload, and, indeed, all at some point avoided or ignored the news, they still continued to access and consume the news. Each individual participant’s management solutions to news overload will be determined by their natural disposition to news consumption; pre-COVID-19 media habits; motivations for consuming news; levels of media and digital literacy; self-efficacy; demographics; and personal factors.

The different methods of managing news overload (MNO) have, in practice, interconnected and overlapped and helped participants to control their news diet and deal with potential, perceived and real occurrences of overload. Both the quantity and variety of news entries in the media diaries point to respondents satisficing. In line with the uses and gratifications model, it indicates they are taking from news media what they need (pull) and at times the news media is giving them (push) what it thinks they need. Their personal choices prior to the pandemic continue to reflect current news consumption patterns but, inevitably, modifications have been made to deal with the abnormal situation. The findings of this research have confirmed patterns in international studies conducted prior to and during the current infodemic, contributing to our understanding of managing information and news overload in an information rich society. It is likely that the patterns ascertained from the media diaries in this study could apply to participants with similar demographics, especially in other Gulf states, but they may also relate to trends further afield both geographically and for respondents with slightly different characteristics. Research has shown that patterns of media use and news consumption are similar for young people in different parts of the world, so it can be reasonably assumed that the approach to dealing with overload, especially in times of crisis, may also be comparable. By exploring this further using both qualitative and quantitative research, it may be possible to determine the extent of shared experiences of the global infodemic.

Funding

This research was funded by United Arab Emirates University (UAEU), grant number G00002655.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the participants of this research for completing the media diaries, reflections and being supportive of the project. I also appreciate the hard work of my Research Assistants, Nur Ahmed and Shihab Ahmad.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Media Diary Template

| Instructions |

|

Media Diary

| Day/Date | Time and Duration (mins) | Media Type (Specify News Article, WhatsApp Message, Instagram Picture, Tweet, etc.). | Details | Follow-Up | Shared (Specify Media e.g., WhatsApp, Instagram etc.) | Thoughts about and Review of Information |

| Sun/29 March | 08:15/10 | bbc.com (news website) https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-52076293 | Skimmed headlines and read story “Lockdown, what lockdown? Sweden’s unusual response to coronavirus” | Checked global update on C-19 cases from WHO website | Sent link to my friend in Sweden using email and uploaded to Facebook | Interesting to know about different a country. Credible website, useful facts and stats |

| Sun/29 March | 09:45/1 | WhatsApp message from my mum about ‘How to Stay Safe during Covid-19’ | Did not read | Deleted because I wasn’t interested |

Appendix B

Media Diary—Reflection Exercise

| Media Diary—Reflections |

| 1. Having kept a media diary, how would you describe your pattern of media use? |

2. How would you rate your ability to do the following with the news and information you consumed?

|

| 3. During the time you completed the media diary, did you ever create any content? (for example, website, blog post, article, comments, upload photos etc.). If yes, please give details. |

| 4. With the current COVID-19 situation, what is your opinion about the amount of information you have been exposed to? Please explain your answer. |

| 5. During this period, have you ever tried to avoid/ignore news? Why or why not? |

| 6. Have you heard of the idea of ‘infodemic’? If yes, what is your understanding of it? |

| 7. Do you feel we are in a time of an infodemic? Have you been able to manage the news and information? |

| 8. Do you feel this period has been a time of information overload (too much information)? |

| 9. Have you experienced any issues relating to fake news or false information about COVID-19? Please give details and your response. |

| 10. If you have any other comments, please provide here. |

| THANK YOU |

References

- Pulido, C.M.; Villarejo-Carballido, B.; Redondo-Sama, G.G.A. COVID-19 infodemic: More retweets for science-based information on coronavirus than for false information. Int. Sociol. 2020, 35, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, C. Big Data Statistics. 2020. Available online: https://techjury.net/blog/big-data-statistics/#gref (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Nordenson, B. Overload! Journalism’s battle for relevance in an age of too much information. In Columbia Journalism Review (CJR); Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Available online: https://archives.cjr.org/feature/overload_1.php (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Bawden, D.; Robinson, L. The dark side of information: Overload, anxiety and other paradoxes and pathologies. J. Inf. Sci. 2009, 35, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.Y.; Chen, G.M. Shut down or turn off? The interplay between news overload and consumption. Atl. J. Commun. 2020, 28, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawden, D. Perspectives on information overload. In Aslib Proceedings; MCB UP Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 1999; Volume 51, pp. 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen, R. Filtering and withdrawing: Strategies for coping with information overload in everyday contexts. J. Inf. Sci. 2007, 33, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltay, T. Information Overload, Information Architecture and Digital Literacy. Bull. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 2011, 38, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, A.; Chi, H.I. News and the Overloaded Consumer: Factors Influencing Information Overload Among News Consumers. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawden, D.; Robinson, L. Information Overload: An Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; Available online: https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-1360?rskey=pGstwF&result=1#acrefore-9780190228637-e-1360-div2-2 (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Newman, N.; Fletcher, R.; Kalogeropoulos, A.; Nielsen, R.K. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- York, C. Overloaded by the News: Effects of News Exposure and Enjoyment on Reporting Information Overload. Commun. Res. Rep. 2013, 30, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.B.; Debbelt, C.A.; Schneider, F.M. Too much information? Predictors of information overload in the context of online news exposure. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2018, 21, 1151–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.M.; Holton, A.; Chen, V. Unpacking overload: Examining the impact of content characteristics and news topics on news overload. J. Appl. J. Media Stud. 2019, 8, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentina, I.; Tarafdar, M. From “information” to “knowing”: Exploring the role of social media in contemporary news consumption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.S. Does Too Much News on Social Media Discourage News Seeking? Mediating Role of News Efficacy Between Perceived News Overload and News Avoidance on Social Media. Soc. Media Soc. 2019, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Kim, K.S.; Koh, J. Antecedents of News Consumers’ Perceived Information Overload and News Consumption Pattern in the USA. Int. J. Contents 2016, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.K.; Fletcher, R.; Newman, N.; Brennen, S.J.; Howard, P.N. Navigating the ‘Infodemic’: How People in Six Countries Access and Rate News and Information about Coronavirus; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Munich Security Conference, Munich, Germany. 15 February 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/munich-security-conference (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Austin, L.; Fisher Liu, B.; Jin, Y. How Audiences Seek Out Crisis Information: Exploring the Social-Mediated Crisis Communication Model. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2012, 40, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzd, A.; Mai, P. Inoculating Against an Infodemic: A Canada-Wide COVID-19 News, Social Media, and Misinformation Survey; Ryerson University Social Media Lab.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, D.; Elliot, R.J.R. Defining misinformation, disinformation and malinformation: An urgent need for clarity during the COVID-19 infodemic. Discuss. Pap. 2020, 20, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, A. Coronavirus: 700 Dead in Iran after Drinking Toxic Methanol Alcohol to ‘Cure Covid-19’. 28 April 2020. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/coronavirus-iran-deaths-toxic-methanol-alcohol-fake-news-rumours-a9487801.html (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Brennen, S.; Simon, F.M.; Howard, P.N.; Nielsen, R.K. Types, Sources, and Claims of COVID-19 Misinformation. 7 April 2020. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Depoux, A.; Martin, S.; Karafillakis, E.; Preet, R.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Larson, H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, M.; Stecula, D.; Farhart, C. How Right-Leaning Media Coverage of COVID-19 Facilitated the Spread of Misinformation in the Early Stages of the Pandemic in the U.S. Can. J. Political Sci. 2020, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook, G.; McPhetres, J.; Bago, B.; Rand, D.G. Attitudes about COVID-19 in Canada, the U.K., and the U.S.A.: A Novel Test of Political Polarization and Motivated Reasoning. Working Paper. 3 June 2020. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/zhjkp/ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Zarocostas, J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coxe, D. The New ‘Infodemic’ Age; Maclean’s: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, L. The art of medicine—COVID-19: The medium is the message. Lancet 2020, 395, 942–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richtel, M. W.H.O. Fights a Pandemic Besides Coronovuris: An ‘Infodemic’; Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/06/health/coronavirus-misinformation-social-media.html (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Wong, J.C. Tech Giants Struggle to Stem ‘Infodemic’ of False Coronavirus Claims; The Guardian: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/10/tech-giants-struggle-stem-infodemic-false-coronavirus-claims (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Wimmer, R.D.; Dominick, J.R. Mass Media Research. An Introduction; Thomson Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, R.; Milligan, C. Engaging with diary techniques. In What is Diary Method? Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2020; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Vandewater, E.A.; Lee, S.J. Measuring Children’s Media Use in the Digital Age: Issues and Challenges. Am. Behav. Sci. 2009, 52, 1152–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, K.; Peil, C. The mobile instant messaging interview (MIMI): Using WhatsApp to enhance self-reporting and explore media usage in-situ. Mob. Media Commun. 2020, 8, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.; Duvel, C. Qualitative media diaries: An instrument for doing research from a mobile media ethnographic perspective. Interact. Stud. Commun. Cult. 2012, 3, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.T.; Roche, T. Making the connection: Examining the role of undergraduate students’ digital literacy skills and academic success in an English Medium Instruction (EMI) university. Forthcoming.

- Head, A.J.; Wihbey, J.; Metaxas, P.T.; MacMillan, M.; Cohen, D. How Students Engage with News: Five Takeaways for Educators, Journalists, and Librarians; Project Information Literacy Research Institute, 16 October 2018; Available online: http://www.projectinfolit.org/uploads/2/7/5/4/27541717/newsreport.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Mejia, C.R.; Delgado-Zegarra, J.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Arce-Esquivel, A.A.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J.; del Portal, M.R.; Villegas, L.F.; Curioso, W.H.; Sekar, M.C.; et al. The Peru Approach against the COVID-19 Infodemic: Insights and Strategies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, D.; Newman, N.; Fletcher, R.; Kalogeropoulos, A.; Nielsen, R.K. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020; Report of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qihao, J.; Sypher, U.; Ha, L. The Role of News Media Use and Demographic Characteristics in the Prediction of Information Overload. Int. J. Commun. 2014, 8, 699–714. [Google Scholar]

- Sabah, D. UAE to Fine Citizens up to $5,500 for COVID-19 Fake News. 20 April 2020. Available online: https://www.dailysabah.com/world/mid-east/uae-to-fine-citizens-up-to-5500-for-covid-19-fake-news (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- The UAE Government Portal. 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). Available online: https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/justice-safety-and-the-law/handling-the-covid-19-outbreak/2019-novel-coronavirus (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Sebugwaawo, I. Coronavirus: Spreading Rumours in UAE Could Get You Jailed, Fined. 9 March 2020. Available online: https://www.khaleejtimes.com/coronavirus-outbreak/coronavirus-spreading-rumours-in-uae-could-get-you-jailed-fined-1 (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.N.; Islam, M.N.; Whelan, E. What drives unverified information sharing and cyberchondria during the COVID-19 pandemic? Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).