Abstract

Prior literature on a two-level supply chain has mainly focused on the game between one manufacturer and one supplier. Exploring group game behavior in a green supply chain (GSC), our research develops and studies a sequential GSC game model consisting of a single manufacturer and three suppliers based on the characteristics of the textile and apparel industry clusters. In our GSC model, the manufacturer is the leader of the supply chain and the suppliers are either homogeneous or complementary. Through equilibrium analysis, we identify critical conditions that influence the behavior of the manufacturer and suppliers to improve the green investment in the supply chain. Our study provides a theoretical basis and a decision-making reference for promoting the cooperation in GSCs and improving the performance of the government’s environmental policies.

1. Introduction

Having the world’s largest producer, consumer, and exporter of the textile and apparel industry, China takes more than 50% of the world’s total fiber processing and 40% of global textile and apparel exports (Statistical data of China Textile Economic Research Center in 2016). In recent years, China has raised great awareness of ecological environment protection. Since 2015, China has implemented the new Environmental Protection Law to encourage enterprises to practice green supply chains (GSC). Furthermore, the law aims to enhance supervision responsibility of governments, which poses enormous challenges to the textile industry in China.

In Zhejiang Province, for example, the total annual output of the textile and apparel industry accounts for 16.62% of the province’s total industrial output. The number of textile and apparel enterprises is 58,178, of which 97.56% are small and medium-sized enterprises (2016 Zhejiang Statistical Yearbook). In recent years, efforts in environmental protection have increased year by year. From the official data released by Zhejiang Environmental Protection Bureau, in 2017, more than 1000 environmental cases of this industry were investigated and penalized in Zhejiang. Large-scale and long-term suspension of production has seriously suppressed industrial development. Therefore, how to establish a sustainable development mode of inter-firm cooperation has become a topic of great concern to the industry and the government.

Green supply chain management (GSCM) is an effective way to improve the performance of industrial environment [1]. Incorporating sustainability into the supply chain is becoming a key priority for many textile and apparel companies. For example, H&M, Patagonia, and The North Face have incorporated various approaches to enhance their levels of sustainable supply chain management [2]. The prior studies have demonstrated that specific modes of collaboration can both enable effective GSCM and diminish barriers for policy implementation [3,4].

The textile and apparel industry in China is geographically clustered [5]. Based on the views of “2016 China Textile Industry Cluster Development Report” by China National Textile and Apparel Council (CNTAC), industry information inside the cluster is almost completely transparent, and there exists complex game behavior among supply chain partners that maintain complementary, competitive, or cooperative relationships with each other. Brands that occupy a central position are the leaders of the supply chain. The upstream and downstream SMEs act according to the leader’s requirements. Our investigation on the textile and apparel industry in Zhejiang also proved the above judgement. Therefore, it is of great practical significance to analyze the game behavior between suppliers and manufacturers in the GSC and explore the GSC governance mechanism, based on the reality of the textile and apparel industry in China.

The prior literature on a two-level supply chain has focused on the game between one manufacturer and one supplier. Research on group game behavior in GSC needs to be improved. For instance, the game between the manufacturer and the supplier group, and the game between the homogenous or complementary suppliers. Based on the characteristics of the textile and apparel industry clusters, this study develops a novel two-level GSC game model consisting of a single manufacturer and three suppliers and identifies some critical conditions for implementing green improvement in the GSC through equilibrium analysis. In particular, our model assumes that the manufacturer is the leader of the supply chain, and the suppliers are either homogeneous or complementary. Through game analysis, we derive the game equilibrium price and corresponding equilibrium conditions of the GSC. Our game model and findings make significant contributions to the literature by providing the strategic guidance for all parties to participate in the greening process and especially for GSC leader to make managerial decision to promote greening.

The rest of this study is organized as follows. The next section reviews prior related literature. Section 3 presents a two-level GSC game model consisting of a single manufacturer and multiple suppliers. In Section 4, through the model optimization analysis, we demonstrate the equilibrium conditions within the GSC and discuss their implications. The last section concludes the paper with practical recommendations.

2. Prior Literature

This section first reviews prior literature by focusing on the following two research streams: Textile and apparel GSCM and game between stakeholders in GSCs, and then highlight the differences of our research from prior studies.

2.1. Textile and Apparel Green Supply Chain Management

In 1996, the Institute of Manufacturing Research at Michigan State University proposed the concept of GSCM. Through a systematic literature review/bibliometric analysis of GSCM articles published from 2006 to 2016, De Oliveira et al. [6] analyzed the subject’s and identified that the textile/manufacturing, automotive and electronic sectors were the most discussed.

Both qualitative and quantitative approaches are available to explore GSCM policies. Stefan [7] reviewed more than 300 representative papers related to green or sustainable supply chains, of which about 50 applied quantitative models, including life cycle assessment, equilibrium analysis models, multi-objective decision making, and analytic hierarchy processes [8,9,10]. An early GSCM case study was also conducted from the perspective of qualitative analysis [11]. In addition, scenario planning model is a popular qualitative model in GSCM research, for instance, Chen et al. [12] proposed a two-tier scenario planning model, consisting of scenario development and policy portfolio planning, to demonstrate the environmental sustainability policy planning process.

In the area of textile and apparel sustainable supply chain management, Shen et al. [2] introduced the fifteen articles published and found that typical approaches include sustainable product strategy, sustainable investment, sustainable performance evaluation, corporate social responsibility, and environmental management system adoption [4,13,14,15,16].

2.2. Game Between Stakeholders in Green Supply Chain

The main reason for the environmental pollution is the conflict between the maximization of the company’s own interests and the overall interests of society. Game theory provides a theoretical solution to the problem of environmental pollution. From the late 1980s, game theory has been widely used to solve various conflict relationships in environmental problems. GSCM is a complex process that involves many internal and external stakeholders, suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, retailers, central government, local governments, consumers [17,18]. Different players have different interests and different attitudes towards SC greening, which leads to the game between GSC stakeholders. The green measures adopted by enterprises are the game results of all stakeholders. Using game theory to study GSCM problems, there are large amounts of literature [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34], which have been mainly conducted from the following three perspectives.

The first is the game analysis of internal stakeholders in the GSC. For instance, Ji et al. [19] used evolutionary game theory to analyze the dynamic cooperative game relations between the manufacturer and the supplier in the GSC and obtained the critical conditions of adopting the ecological strategy simultaneously. Ghosh and Shah [20] built game theoretic models and show how greening levels, prices and profits are influenced by channel structures, and used a two-part contract to coordinate the GSC. Liu [21] established a GSC game model between a single manufacturer and a single supplier, taking a government subsidy and outside option into consideration. In addition, it discussed what the supplier should do when the leading manufacturer implements internalization of the environmental cost. Liu [22] constructed a supply chain pricing strategy game model based on the internalization of environmental costs and used the net present value (NPV) model to generate a reasonable value of government subsidies. Jiang and Sui [23] built a game model consisting of a single manufacturer and a single retailer under the revenue sharing contract and explored the optimal range of revenue sharing coefficients. Raj et al. [24] proposed a generalized analytical model for GSC and obtained a new type of hybrid contract RGCS (revenue and greening-cost sharing contracts).

The second is the game analysis of GSC and external stakeholders. Typically, Zhu and Dou [25] formulated a game theoretic model to study the costs and benefits of core enterprises in the GSC under different environmental strategies. Jin et al. [26] constructed a game model with green products as variables in the context of two government incentive strategies: Subsidies based on recycling percentage or recycling amount. The best strategies for enterprises and the optimal incentives for governments in equilibrium situations were obtained.

The third is the game analysis of multi-stakeholders. For instance, Hu [27] built a two-level non-cooperative GSC game model, considering government and consumer supervision, to clarify the transmission mechanism of the environmental investment process in GSC. An et al. [28] established a game revenue function and strategy analysis model to explain the game strategy relationships from three levels, which are local government and enterprises, local government and central government, and enterprises and consumers. Liu et al. [29] selected the central government, local government and supply chain enterprises to establish a dynamic game model and explored the mechanism of supply chain environmental costs internalization. They further found the game equilibrium strategy and the interaction relationships between various stakeholders. Madani and Rasti-Barzoki [30] developed a competitive mathematical model of government as the leader and two competitive green and non-green supply chains as the followers, pricing policies, greening strategies and governance tariffs determining in supply chains competition under government financial intervals were discussed.

In summary, the previous research on GSCM has covered the connotation, driving and obstacle factors, the game relationship optimization among various stakeholders, and policy recommendations. Most of the existing literature has mainly analyzed the game relationship based on the supply chain structure of a single manufacturer and a single supplier. However, the Chinese textile and apparel industry presents a regional clustered distribution, which means there are complex game relationships between core manufacturers and multiple suppliers, between each other of the homogeneous or complementary suppliers. Our targeted GSC mechanism research towards this scenario, therefore, has special theoretical and practical value. Specifically, our study makes the following main contributions to the existing literature: (1) We develop a one-to-three sequential game model by incorporating the characteristics of homogeneous and complementary suppliers; (2) we investigate the group game behavior in GSC of textile and apparel industry with our analytical model; (3) we derive the equilibrium under three different scenarios, which quantify and define the scope of regulation acceptable to all parties, helping to develop the best GSC strategies.

3. Model of Green Supply Chain

This section presents a two-level GSC game model consisting of a single manufacturer and multiple suppliers. We first describe the model setting and sequence, and then show the basic game model along with the manufacturer and suppliers’ decision before and after green investment.

3.1. Model Setting

The supply chain of the textile and apparel industry mainly includes raw material suppliers (providing cotton, silk and wool), suppliers of primary products (providing clothing fabric), manufacturer of garments, and retailers. This process is accompanied by a variety of ancillary support links, including auxiliary material suppliers, manufacturing equipment suppliers, and so on. According to the industry, this study abstracts a two-level GSC structure consisting of one manufacturer and three suppliers (two homogeneous suppliers and one complementary supplier). We develop a manufacturer-led game model to explore its multi-party game relationship, and to obtain the equilibrium prices when benefits are maximized. The research assumptions are as follows:

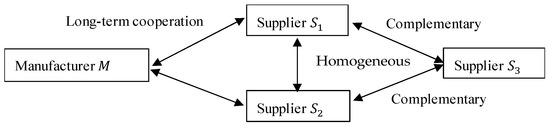

(1) Both the manufacturer and suppliers are risk-neutral, and the goal of their decisions is to maximize profits. Assume that the manufacturer only involves the operation of two raw materials, the main material and the auxiliary material . The supplier and the supplier . are homogenous suppliers, providing the raw material . The supplier , as a complementary supplier of the supplier . and the supplier , provide the raw material . The manufacturer . and the supplier have established a stable cooperative relationship in long-term procurement. The auxiliary material supplier passively adopts the same decision-making options as the main material suppliers. Relationships between the model’s main players are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Relationships between the model’s main players.

(2) Referring to Jiang and Sui [23] and Zhu and Dou [25], the demand is positively correlated with the total market demand and the product’s greening level , and negatively correlated with the unit price of the product. The demand function is represented as . Consumers who prefer “cheap and good quality” products tend to buy green products at a low price. is the price sensitivity coefficient and . is the coefficient representing the sensitivity of a consumer to a product’s greening level, where . Referring to Zhu and Dou [31], it is assumed that the price of ordinary products before greening is , and its greening level is . is the lowest greening level of the admission to the market. The price of products after greening is , and its greening level is . Obviously, , i.e., the higher the greening level of the product, the more environmentally friendly. In the textile and apparel industry, the greening level of the product can usually be measured by the solvent toxicity and recyclability in the production process, the carbon label and the degree of natural degradation of the discarded clothes.

(3) This study focuses on the analysis of game relationships within GSC, and subsequent research can be extended to the analysis of game relationships with external stakeholders. Therefore, we assume that external stakeholders have reached a game equilibrium, that is, consumers are willing to purchase green products produced by manufacturers, and the government will supervise manufacturers to implement green investment. Manufacturers are motivated to develop green products, the costs of which includes production process improving, procurement of related equipment, and R&D of new products. Referring to D’Asprement’s approach [32], the product R&D cost formula is , where is the R&D adjustment factor and . Supplier and are free to decide whether to respond to the manufacturer’s green investment. R&D costs are all borne by the manufacturer, and suppliers only bear additional green processing costs.

3.2. Modelling Thoughts

With reference to Ding and Shen [33] and Wang [34], in the early stage of enterprise investment in green product research, subsidies and supervision given by local governments are the main driving force. Consumers’ acceptance of green products motivates further R&D investment.

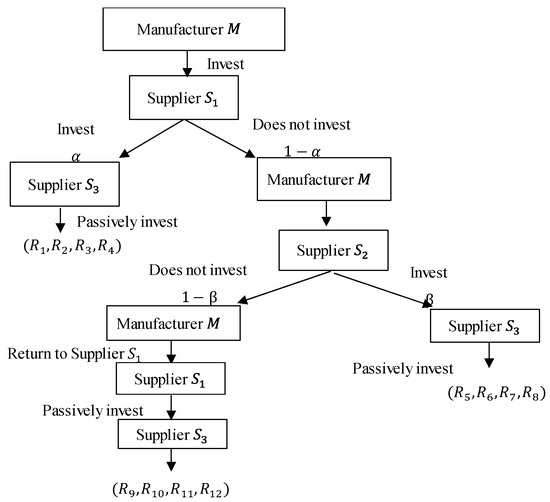

In this study, according to the current environmental policy of the textile and apparel industry in China, we assume that local governments adopt supervision and punishment policy first on the manufacturer. After taking the lead in implementing the green investment, the manufacturer puts forward higher environmental requirements to its upstream suppliers. The supplier , the long-term partner of the manufacturer , faces the game choice of whether to implement green investment. If the supplier chooses to invest, its partnership with the manufacturer continues. The complementary supplier of the supplier passively participates in green investment.

If the supplier chooses not to respond to the manufacturer , the manufacturer seeks a new supplier . At this point, the supplier faces the game choice of whether to implement the green investment. If the supplier chooses to invest, they reach a partnership. The manufacturer needs to pay extra purchase costs. The complementary supplier of the supplier passively participates in green investment.

If the supplier chooses not to respond, the manufacturer returns to the original supplier . Here, the supplier keeps the same cost structure as before greening, but the manufacturer needs to pay additional raw material processing costs. The complementary supplier of the supplier passively participates in green investment.

The game relationships and process are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The manufacturer-led one-to-three green supply chain (GSC) game model.

3.3. Decisions Before and After Green Investment

(1) Before the implementation of the green investment, the unit price of the main material provided by the supplier and is , and there is a linear relationship of between the price and the sales volume. Here, is the total demand of and is the price sensitivity coefficient, where . The unit price of the auxiliary material provided by the supplier is , and there is a linear relationship of between the price and the sales volume, in which is the total demand of , is the price sensitivity coefficient, and . The processing cost of the manufacturer’s unit product is . The unit price of the manufacturer’s product is , and there is a linear relationship of between the price and the sales volume. Each unit of the product needs units of main material and units of auxiliary material , that is, and .

(2) After the implementation of green investment, the unit price of the manufacturer’s product is . Since the products are improved only in the greening level, the relationship between the price and sales volume still satisfies . The unit price of the main material provided by the supplier and is , and there is a linear relationship of between the price and the sales volume. The unit price of the auxiliary material provided by the supplier is , and there is a linear relationship of between the price and the sales volume. The processing cost of the manufacturer’s unit product is . Each unit of the product still needs units of and units of , that is, . To simplify the analysis, it is assumed that the operating costs, except the processing costs of the suppliers and manufacturers, do not change after the implementation of the green investment.

(3) After the manufacturer implements the green investment, if the original supplier does not cooperate, the manufacturer will purchase from the supplier . The purchase price is still , but the manufacturer M has to bear an additional purchase cost . Meantime, the supplier needs to sell the raw materials to other manufacturers, and each unit of material generates additional sales expenses . If the supplier does not cooperate, the manufacturer returns to purchase raw materials from the original supplier . The purchase price is , but the manufacturer needs to pay an additional processing fee per unit product.

(4) After the manufacturer implements the green investment, if the original supplier and the substitute supplier do not respond to the investment, and the manufacturer still purchases the raw materials from the original supplier , the purchase price per unit is still , but it will incur additional processing costs per product for manufacturer .

(5) After the manufacturer implements the green investment, the probability that the supplier cooperates is , where . After the manufacturer implements the green investment, the probability that the supplier cooperates is , where .

The main decision variables before and after green investment are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Decision variables before and after green investment.

3.4. Basic Game Model

In the game between the manufacturer and its suppliers ,,, the decision-making behavior of the participants has a sequence and all participants can obtain the historical information of the game, then making their own decisions optimal. Therefore, the manufacturer-led one-to-many sequential game is a complete information dynamic game system. With the deepening of the supply chain greening, the game is played repeatedly. As the game evolves, the system will continue to optimize and improve until the Pareto optimality is achieved. The manufacturer takes the lead in implementing a green investment, and the supplier chooses to cooperate. The profit of the manufacturer is the revenue of the product minus the processing cost of the product, the purchase cost of the material and , and the R&D cost . The profit of the supplier , is the revenue of main material minus the raw material cost and the raw material processing cost. The profit of the supplier , is the revenue of auxiliary material minus the raw material cost and raw material processing cost. At this point, the profit of the supplier , in the original supply chain, is the revenue of the material minus the raw material cost, and the raw material processing cost. The functions are as follows:

The manufacturer takes the lead in implementing a green investment. If the supplier chooses not to cooperate, the manufacturer achieves cooperation with the supplier . Then, the profit of the manufacturer , is the revenue of the products minus the processing cost of the product, the additional procurement cost, the procurement cost of the materials and , and the R&D cost . The profit of the supplier is the revenue of the main material minus the raw material cost and raw material processing cost. The profit of the supplier , is the revenue of the auxiliary material minus the raw material cost and raw material processing cost. At this point, the profit of the supplier , is the revenue of the material minus the raw material cost, the raw material processing cost and the additional sales cost. The functions are as follows:

The manufacturer takes the lead in implementing a green investment and fails to reach cooperation with the supplier after refused by the supplier . Then the manufacturer returns to cooperate with the original supplier . Thus, the profit of the manufacturer is the revenue of the product minus the product processing cost, the procurement cost of the materials and , the additional processing cost and the R&D cost . The profit of the supplier is the revenue of the main material minus the raw material cost and raw material processing cost. The profit of the supplier , is the revenue of the auxiliary material minus the raw material cost and raw material processing cost. At this point, the profit of the supplier is the revenue of the main material minus the raw material cost and the raw material processing cost before green investment. The functions are as follows:

4. Analysis and Discussion

We next show the conditions that influence the equilibriums that can be reached and discuss their implications.

4.1. Game Equilibrium When the Manufacturer Takes the Lead in Bidding

Proposition 1.

In the game of complete information, if the manufacturertakes the lead in bidding, an equilibrium purchase priceexists, which maximizes the expected profits of the manufacturer. The achievement of equilibrium state depends on the benefits conditions of the players at this price.

Proof.

The expected profit of manufacturer is,

Formula (13) is substituted by Formulas (1), (5), and (9), that is,

To simplify the formula, Let , .

Formula (14) is substituted by , , , , , that is, .

The first derivative is taken with respect to , that is,

We let the first derivative be zero, hence, when the manufacturer maximizes the profits, the optimal price of is,

The manufacturer has the maximum expected profits, when the purchase price of the main material is . □

Proposition 1 shows that in the manufacturer-led supply chain, the manufacturer has the right to bid first. The rational manufacturer tends to choose the price where its expected profits are maximum. In the next orderly game, the supplier needs to choose whether to accept the price by comparing the benefits in different situations. If , the rational supplier will choose to accept the price and implement the green investment. The supply chain reaches equilibrium here. If not, the supplier will refuse to cooperate. Then, the manufacturer bids to the supplier . Then the supplier needs to choose whether to accept the price. The supplier compares the benefits in different situations. If is greater than obtained by its original cooperation with other manufacturers, the supplier will choose to accept the price and implement the green investment. The supply chain reaches equilibrium here. If not, the supplier will refuse to cooperate, and the manufacturer returns to cooperate with the original supplier at the price of . The supply chain regains equilibrium. Therefore, in the game in which the manufacturer takes the lead in bidding, the equilibrium price of the green investment cooperation reached the price of . Nevertheless, which point to reach depends on the benefits conditions of the players at this price.

4.2. Game Equilibrium When the Supplier Takes the Lead in Bidding

Proposition 2.

In the game of complete information, if the supplier takes the lead in bidding, equilibrium pricesandexist, which maximizes the expected profits of the supplierandrespectively.

Proof.

(1) The expected profit of supplier is,

Formula (15) is substituted by Formulas (2), (8), and (10), that is,

Formula (16) is substituted by , and the first derivative is taken with respect to , that is,

We let the first derivative be zero, hence, when the supplier maximizes the profits, the optimal price of is,

It shows that the supplier has the maximum expected profits after the green investment, when the purchase price of the main material is .

(2) The expected profit of the supplier is,

Formula (17) is substituted by Formulas (4), (6), and (12), that is,

Formula (18) is substituted by , and the first derivative is taken with respect to , that is,

We let the first derivative be zero, hence, when the supplier maximizes the profits, the optimal price of is,

It shows that the supplier has the maximum expected profits after the green investment, when the purchase price of the main material is . □

Proposition 2 demonstrates that to motivate the suppliers to participate in green investment, the manufacturer should allow the supplier to bid first, or allow the supplier to bargain. The supplier will then tend to choose the equilibrium price , where its expected profits are maximum. The basic conditions for the manufacturer to accept the price of the supplier are and . Otherwise, the manufacturer will turn to the supplier . The supplier will then tend to choose the equilibrium price , where its expected profits are maximum. The basic condition for the manufacturer to accept the price of the supplier is . Otherwise, the manufacturer will switch back to the supplier and reach cooperation under the equilibrium price . In a real scenario with known data conditions, the final game equilibrium will be determined by one of the three participants. In the case of a supplier’s first bid, if the manufacturer intends to cooperate with a specific supplier, it needs to bargain with the supplier to make its expected benefits meet the critical condition for cooperation.

4.3. Expected Benefit Analysis of the Supplier

Proposition 3.

Although the supplieris passively cooperative, an optimal supply priceof the auxiliary materialstill exits, where the expected profits of the supplierare maximum in the GSC.

Proof.

The expected profit of supplier is,

Formula (19) is substituted by Formulas (3), (7) and (11), that is,

Formula (20) is substituted by , and the first derivative is taken with respect to , that is,

We let the first derivative be zero, hence, when the supplier maximizes the profits, the optimal price of is,

It shows that the supplier has the maximum expected profits after the green investment, when the purchase price of the auxiliary material is . □

Proposition 3 indicates that regardless of which of the suppliers or chooses to cooperate with the manufacturer , the cooperation of the supplier is required. According to the premise, the complementary supplier in this study is passively cooperative. However, if the benefits of the supplier is and , or and , the supplier will tend to promote the suppliers and to cooperate with the manufacturer. On the contrary, if and , the supplier will tend to support the suppliers to refuse the green investment. The closer the equilibrium purchase price of material is to , the more inclined will support the implementation of green investment.

4.4. The Implications of the Study

In this study, according to the actual situation of China’s textile and apparel industry, we consider the research scenario where the government adopts a punishment-based governance strategy (i.e., production will be suspended until the environmental standards are met). In this context, the leader of the supply chain (manufacturer) is trying to get suppliers involved in the greening of the supply chain. Our study provides a clear conceptual framework for the players to get involved in the greening process.

In particular, we focus on the decision-making process of the manufacturer-led supply chain, and define the decision-making scope in the sequential game. Proposition 1 obtain three possible game equilibriums under the optimal conditions of the manufacturer’s expected benefits. In a single game process, equilibrium can only be one of them. Hence, the manufacturer can encourage the suppliers to participate in greening by partly bearing the green processing costs for the suppliers, or allow the suppliers to take the lead in bidding, which might be more effective. Therefore, in Proposition 2 and Proposition 3, we further discuss the game equilibrium and conditions in the case when suppliers take the lead in bidding. In this case, the suppliers tend to get optimal benefits, and it is more conducive to achieving greening cooperation.

5. Conclusions

The textile and apparel industry in China is at a critical stage of green upgrading. The fulfillment of GSCM is a dynamic game process with complete information. Faced with the constraints imposed by different strategic choices from different stakeholders, stakeholders need to make scientific and rational decisions to address the main issues in the green process. Based on the reality of the textile and apparel industry, this study develops a one-to-three sequential GSC game model, in which the manufacturer is the leader. Through game analysis, the game equilibrium price and equilibrium conditions of the GSC are defined, which provides the strategic space for all parties to participate in the greening process and especially help the GSC leader to make managerial decision to promote greening. Our game analysis makes the following specific contributions to the existing literature.

(1) We find that the equilibrium price of the GSC game is and there are three possible equilibrium states under this price. In a manufacturer-led sequential game, the manufacturer has the right to bid first. The game equilibrium price can be achieved under the condition of the manufacturer’s first bid. At this price, the manufacturer has the maximum expected benefits, and one of the three game equilibrium states, i.e., , , and , can be reached. We obtain the strategic boundary of each equilibrium state. In a real scenario with known data conditions, it is not difficult to deduce the final game equilibrium based on the results of our model.

(2) If the manufacturer intends to cooperate with a specific supplier at the price of , this equilibrium can be reached by adjusting the supplier’s cost conditions to meet its decision boundaries. For example, in the first round of the game, to promote the supplier to select the cooperation strategy, the manufacturer can partly bear the processing cost () of the green material for the supplier, which can thus increase the supplier’s expected return to meet the critical condition for cooperation (as described in Proposition 1).

(3) If the manufacturer intends to maximize the supplier’s willingness to cooperate, the supplier may be allowed to take the lead in bidding. This situation usually occurs at the initial stage when the manufacturer pushes the greening of the supply chain. We assume that the suppliers could take the lead in bidding and obtain equilibrium prices and , as well as possible equilibrium states and equilibrium conditions. This result provides useful guidance to effectively encourage suppliers to participate in GSC.

(4) The influence of complementary suppliers on the decision-making of the main material supplier cannot be ignored. The strategy of adjusting the purchase price can encourage complementary suppliers to support greening. We consider the complementary supplier of auxiliary materials in this study, analyze the optimal expected benefits of the complementary supplier, and obtain the optimal supply price , which helps for interpreting the behavior of such suppliers.

In summary, each stakeholder has the best behavior strategy in the GSC game. There must be differences between these optimal strategies. Controlling the differences within the acceptable range of all the players is the key to achieving the equilibrium of cooperative games. Quantifying these differences and defining the scope of regulation acceptable to all parties is the focus of this study.

The limitation of this study is that the scenarios and conditions considered are still not comprehensive. First, we only consider the GSC game model under the complete information and does not consider the case of incomplete information. Second, we assume the ex-factory price of the product as the retail price and have not considered the impact of the retailer on the supply chain pricing. In addition, this game is only carried out within the supply chain, without considering the situation where external stakeholders, i.e. local governments, central government and consumers, have not achieved a balanced interest. Third, if the government still adopts the environmental policy of “who pollutes who governs” and shifts from “punishment-based” to “subsidy-based” in policy measures, the government will subsidize SMEs directly and it will be unclear what types of the game equilibrium of the GSC can be achieved. Fourth, future research needs to conduct numerical analysis with actual manufacturer and supplier behaviors to clearly indicate the conditions of the different types of equilibrium, which will test the model and help practitioners better understand the strategies they should select in a real scenario. Finally, as different countries implement different environment-protection policies and initiatives, it will be interesting to further evaluate how our model might fit different policy settings in different countries.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the development and completion of this paper. Conceptualization and Framework Design, Q.L.; Methodology, Q.L. and W.X.; Data Collection, W.R.; Data Curation W.X. and L.J.; Review & Editing, Z.Z. All authors conducted the revisions and approved the publication.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by MOE (Ministry of Education of China) Project of Humanities and Social Science Foundation (19YJA790041), Zhejiang Social Science Planning Project (19NDJC280YB), Ningbo Social Science Planning Project (G18-ZN10), and Zhejiang University Students’ Science and Technology Innovation Program (2018R420004).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Darnall, N.; Jolley, G.J.; Handfield, R. Environmental management systems and green supply chain management: complements for sustainability? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Li, Q.; Dong, C.; Perry, P. Sustainability issues in textile and apparel supply chains. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, S.; Lee, Y.; Memon, M. A sustainable outsourcing strategy regarding cost, capacity flexibility, and risk in a textile supply chain. Sustainability 2016, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelze, N. Sustainable supply chain management implementation—enablers and barriers in the textile industry. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.Q.; Wang, S. Research on the Evaluation of Innovation Capability of China’s Textile Industry Clusters. Sci. Manag. Res. 2017, 35, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira, U.R.; Espindola, L.S.; da Silva, I.R.; da Silva, I.N.; Rocha, H.M. A systematic literature review on green supply chain management: Research implications and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, S. A review of modeling approaches for sustainable supply chain management. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 54, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar]

- Clift, R. Metrics for supply chain sustainability. Clean Technol. Environ. 2003, 5, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukidwe, N.U.; Bakshi, B.R. Flow of natural versus economic capital in industrial supply networks and its implications to sustainability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 9759–9769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.N. Sustainable supply chains: a study of interaction among the enablers. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2010, 16, 508–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J. Greening the Supply Chain; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.Y.; Huang, C.J. A two-tier scenario planning model of environmental sustainability policy in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagurney, A.; Yu, M. Sustainable fashion supply chain management under oligopolistic competition and brand differentiation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D.; Altuntas, C. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: An analysis of corporate reports. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M.; Micheletti, M. Introducing the sustainability challenge of textiles and clothing. J. Consum. Policy 2016, 39, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, D.; Strähle, J.; Müller, M.; Freise, M. Social sustainable supply chain management in the textile and apparel industry—A literature review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barari, S.; Agarwal, G.; Zhang, W.J.C.; Mahanty, B.; Tiwari, M.K. A decision framework for the analysis of green supply chain contracts: An evolutionary game approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 2965–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Govindan, K.; Zhu, Q. A system dynamics model based on evolutionary game theory for green supply chain management diffusion among Chinese manufacturers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 80, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.J.; Zhang, R.X. Economic Supply Chain Purchasing Management Based on Evolutionary Game. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 1, 26–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, D.; Shah, J. A comparative analysis of greening policies across supply chain structures. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Game Analysis between Supplier and Manufacturer in the Environmental Cost Internalization of Supply Chain. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering and Business Management, Beijing, China, 26–28 October 2012; pp. 994–997. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Supply chain environmental cost internalization pricing strategy-based on manufacturer-led secondary supply chain research. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.Y.; Sui, C. Green supply chain game model and revenue sharing contract considering product greenness. China Manag. Sci. 2015, 6, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, A.; Biswas, I.; Srivastava, S.K. Designing supply contracts for the sustainable supply chain using game theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.H.; Dou, Y.J. Evolutionary game model of government and core enterprises in green supply chain. System Eng. Theor. Prac. 2007, 12, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.F.; Cao, E.B.; Lai, M.Y. Analysis of Green Marketing Evolution Game in Duopoly Retail Market. J. Syst. Eng. 2012, 3, 383–389. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, A.L. Analysis of corporate environmental investment decision based on internalization of supply chain and environmental costs. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- An, Z.R.; Ding, H.P.; Hou, H.Q. Game analysis and strategy research of environmental performance stakeholders. Inq. Econ. Issues 2013, 3, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Ding, H.P.; Hou, H.Q. Investigation on the choice of stakeholder behavior choice in internal supply chain environmental costs. China Popul. Res. Env. 2014, 6, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Madani, S.R.; Rasti-Barzoki, M. Sustainable supply chain management with pricing, greening and governmental tariffs determining strategies: A game-theoretic approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 105, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.H.; Dou, Y.J. Green supply chain management game model based on government subsidy analysis. J. Manag. Sci. China 2011, 6, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aspremont, C.; Alexis, J. Cooperative and noncooperative R & D in duopoly with spillovers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1988, 78, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.P.; Shen, J.S. Internalization of transportation social costs and marketization of electric vehicles in China. J. Beijing Jiaotong Univ. 1999, 23, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. Analysis of the game between ecological environment cost and enterprise internalization. J. Tianjin Univ. 2008, 10, 393–396. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).