Reflecting on Social Inclusion Through Philosophical Discussion: A Sustainable Partnership Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- “Enhance collaboration between sectors and stakeholders”. This involves trust and collaboration.

- (2)

- “Building partnerships and platforms at the national level”. This is underpinned by support and mechanisms for engagement.

- (3)

- “Partnership skills and competencies”. This requires building capacity and perfecting systems and processes.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Reflecting on the Past

2.2. Cultural Landscape

3. Paving the Way to Social Inclusion Through Social Impact

3.1. Social Inclusion

3.2. Social Impact

4. Community Involvement Through Partnership

Sustainable Partnership Development

5. Philosophical Insight

5.1. Philosophical Definition

5.2. Moore’s (1903) [54] Argument

5.2.1. What Is the Open Question Argument?

5.2.2. Criticism of the Open Question Argument

6. The Real-World Challenges of Partnerships

7. Discussion

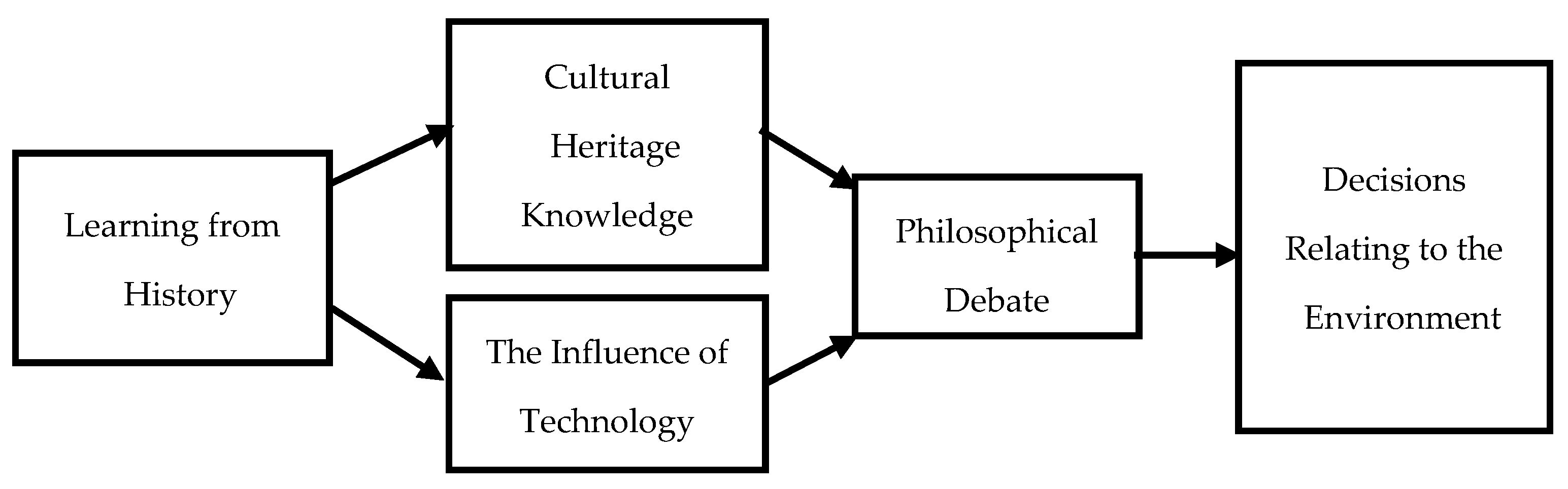

A Framework to Foster Global Partnerships

8. Practical Implications

8.1. How-to Implement the Framework

- The Symbolic Representation factors need to be harmonized across nations and policy makers need to be held to account for determining how cultural value systems are to be influenced and shaped, considering past achievements, current uses and future uses of technology, and important social factors such as the production and consumption of music.

- Collaborative knowledge needs to be viewed as being formed through two direct processes: (i) key influencers that draw on data and information from various sources and (ii) futurologists that are engaged by or contribute to a range of publications and events that are acknowledged by key influencers.

- Collaborative knowledge should be viewed as malleable in the sense that it is to be appraised through being challenged—‘right’ versus ‘wrong’.

- Cultural value systems need to allow new insights to be discussed and the attitudes and behaviour of people to be influenced and changed in an appropriate way.

- Equality is viewed from the perspective of social impact and measures must be developed to monitor the progress made in terms of social inclusion.

8.2. How to Use the Framework

9. Theoretical Contribution

10. Limitations

11. Future Research

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kirby, A. The right to make mistakes? The limits to adaptive planning for climate change. Challenges 2022, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L.; Logan, A.C.; Bristow, J.; Rozzi, R.; Moodie, R.; Redvers, N.; Haahtela, T.; Warber, S.; Poland, B.; Hancock, T.; et al. Exiting the Anthropocene: Achieving personal and planetary health in the 21st century. Allergy 2022, 77, 3498–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The concept of sustainable development: From its beginning to the contemporary issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. Collaboration and partnership in question: Knowledge, politics and practice. J. Educ. Policy 2000, 14, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Harrison, J.S. Stakeholder theory at the crossroads. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell-Bennett, R.; Polonsky, M.J.; Fisk, R.P. SDG commentary: Services that sustainably manage resources for all humans—The regenerative service economy framework. J. Serv. Mark. 2024, 38, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertson, K.; Fox, C.; O’Leary, C.; Painter, G. Towards a theoretical framework for social impact bonds. In NonProfit Policy Forum; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2020; p. 20190056. [Google Scholar]

- Bexell, M.; Jönsson, K. Responsibility and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. Forum Dev. Stud. 2017, 44, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, D. Introduction to Critical Theory: Horkheimer to Habermas; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Till, R. Songs of the stones: An investigation into the acoustic culture of Stonehenge. J. Int. Assoc. Study Pop. Music 2010, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, J. The archaeology of sound and music. World Archaeol. 2014, 46, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nordgren, A. Artificial intelligence and climate change: Ethical issues. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2023, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, A.; Ahmad, A.; Abbas, S.; Inairat, M.; Al-kassem, A.H.; Rasool, A. How artificial intelligence is promoting financial inclusion? A study on barriers of financial inclusion. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Business Analytics for Technology and Security (ICBATS), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 16–17 February 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, S.; Qing, L.; Mehmood, U.; Almulhim, A.A.; Aljughaiman, A.A. From digital advancement to SDGs disruption: How artificial intelligence without inclusion threatens sustainable development in G7 economies. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djatmiko, G.H.; Sinaga, O.; Pawirosumarto, S. Digital transformation and social inclusion in public services: A qualitative analysis of E-government adoption for marginalized communities in sustainable governance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpemon, P. Chapter 14: The philosophy of music: Formalism and beyond. In The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics; Kivy, P., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 254–275. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keeffe, T. Performance, materiality, and heritage: What does an archaeology of popular music look like? J. Pop. Music Stud. 2013, 25, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Ruiz, E.; Asano, M.; Ryu, J.; Kirby, H.; Abernathy, D.; Rosholt, M. Preference or choice? Relationships among college students’ music preference, personality, stress, and music consumption. Arts Psychother. 2025, 93, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers-Melnick, S.N.; Gunzler, D.; Love, T.E.; Koroukian, S.M.; Beno, M.; Dusek, J.A.; Rose, J. Impact of sociodemographic, clinical, and intervention characteristics on pain intensity within a single music therapy session. J. Pain 2025, 36, 105556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.J.; Chong, M.C.; Tan, M.P.; Chua, Y.P. Tai Chi with music improves quality of life among community-dwelling older persons with mild to moderate depressive symptoms: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Geriatr. Nurs. 2019, 40, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, H. Understanding social inclusion and its meaning for Australia. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2010, 45, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licsandru, T.C.; Cui, C.C. Subjective social inclusion: A conceptual critique for socially inclusive marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, D. Social inclusion: A philosophical anthropology. Politics 2005, 25, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, H. The Contexts of Social Inclusion. DESA Working Paper No. 144. (ST/ESA/2015/DWP/144); Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxoby, R. Understanding Social Inclusion, Social Cohesion, and Social Capital; Economic Research Paper: 2009-09; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Odena, O.; Scharf, J. Music education in Northern Ireland: A process to achieve social inclusion through segregated education? Int. J. Music Educ. 2022, 40, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charity Commission. The Promotion of Social Inclusion; Charity Commission: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Le, H.; Polonsky, M.; Arambewela, R. Social inclusion through cultural engagement among ethnic communities. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkiamäki, R.; O’Dare, C.E. Intergenerational friendship as a conduit for social inclusion? Insights from the “book-ends”. Soc. Incl. 2021, 9, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Strnadová, I.; Loblinzk, J.; Danker, J.C.; Cumming, T.M. The role of mobile technology in promoting social inclusion among adults with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 34, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brik, A.B.; Brown, C.T. A critical review of conceptualisation and measurement of social inclusion: Directions for conceptual clarity. Soc. Policy Soc. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brik, A.B.; Brown, C.T. Global trends in social inclusion and social inclusion policy: A systematic review and research agenda. Soc. Policy Soc. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkert, C.; Köhler, K.; von Kutzleben, M.; Hochgräber, I.; Cavazzini, C.; Völz, S.; Palm, R.; Holle, B. Social inclusion of people with dementia—An integrative review of theoretical frameworks, methods and findings in empirical studies. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 773–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidley, J.M.; Hampson, G.P.; Wheeler, L.; Bereded-Samuel, E. Social inclusion: Context, theory and practice. Aust. J. Univ. Community Engagem. 2010, 5, 6–36. [Google Scholar]

- Allman, D. The sociology of social inclusion. SAGE Open 2013, 3, 2158244012471957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, S.C.; Kraneveld, A.D.; van Dijk, J.; Kalfagianni, A.; Knulst, A.C.; Lelieveldt, H.; Moors, E.H.M.; Müller, E.; Pieters, R.H.H.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; et al. Towards healthy planet diets—A transdisciplinary approach to food sustainability challenges. Challenges 2020, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, S.; Swartz, S. Profits with Purpose: How Organizing for Sustainability can Benefit the Bottom Line; McKinsey: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, S.L.; Pawankar, R.; Allen, K.J.; Campbell, D.E.; Sinn, J.K.H.; Fiocchi, A.; Ebisawa, M.; Sampson, H.A.; Beyer, K.; Lee, B.-W. A global survey of changing patterns of food allergy burden in children. World Allergy Organ. J. 2013, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, S.; Ojala, M.; Soler, M. Promoting social inclusion counting with everyone: Learning Communities and INCLUD-ED. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2011, 21, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trim, P.R.J.; Lee, Y.-I. A strategic approach to sustainable partnership development. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2008, 20, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlile, P.R. Transferring, translating, and transforming: An integrative framework for managing knowledge across boundaries. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, A.; Currall, S. The coevolution of trust, control, and learning in joint ventures. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraiappah, A.K.; Munoz, P. Inclusive wealth: A tool for the United Nations. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2012, 17, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Phillips, R.; Sisodia, R. Tensions in stakeholder theory. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, J.; Sachs, S.; Leinonen, H.; Heikkinen, A.; Lause, D. Stakeholder engagement: Past, present and future. Bus. Soc. 2022, 61, 1136–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresford-Dey, M. Educational leadership: Enabling positive planetary action through regenerative practices and complexity leadership theory. Challenges 2025, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, A. Chapter 1: Definition. In The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Music; Gracyk, T., Kania, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tett, L. Partnerships, community groups and social inclusion. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2005, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stålbrand, I.S.; Brissman, I.; Nyman, L.; Sidenvall, E.; Tranberg, M.; Wallin, A.; Wamsler, C.; Jacobsen, J. An interdisciplinary model to foster existential resilience and transformation. Challenges 2025, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1922; Reprint; Available online: https://fair-use.org/g-e-moore/principia-ethica/s.10 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Yakubu, O.H. Delivering environmental justice through environmental impact assessment in the United States: The challenge of public participation. Challenges 2018, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowring, J. The Works of Jeremy Bentham; William Tait: Edinburgh, UK, 1841. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, B.J.E. The open question argument. In Just the Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Arguments in Western Philosophy; Verbeek, B.J.E., Bruce, M., Barbone, S., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 237–239. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, J. The Naturalistic Fallacy. Richmond J. Philos. 2006, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, A.C. Hume on ‘is’ and ‘ought’. In The Is-Ought Question: A Collection of Papers on the Central Problem in Moral Philosophy; Hudson, W.D., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1969; pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty, J.; Norman, W.; Heath, J. Business ethics and (or as) political philosophy. Bus. Ethics Q. 2010, 20, 427–452. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, F. The open question argument: What it isn’t; and what it is. Philos. Issues 2005, 15, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfler, V.; Ackermann, F. Understanding intuition: The case for two forms of intuition. Manag. Learn. 2012, 43, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freehling, W.W. The Reintegration of American History: Slavery and the Civil War; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Veresiu, E.; Giesler, M. Chapter 11: Neoliberalism and consumption. In Consumer Culture Theory; Arnould, E.J., Thompson, C.J., Eds.; Sage Publications Limited: London, UK, 2018; pp. 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.G.; Spitzeck, H. Measuring the impacts of NGO partnerships: The corporate and societal benefits of community involvement. Corp. Gov. 2011, 11, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.S. Resources in emerging structures and processes of change. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L.; Webb, D. A new vision for Challenges: A transdisciplinary journal promoting planetary health and flourishing for all. Challenges 2024, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.; Freeman, R.E. Stakeholders, social responsibility, and performance: Empirical evidence and theoretical perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, M.; Helfen, M. The foundations of social partnership. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2016, 54, 334–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellè, N. Leading to make a difference: A field experiment on the performance effects of transformational leadership, perceived social impact, and public service motivation. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2013, 24, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baily, P.; Farmer, D.; Jessop, D.; Jones, D. Purchasing Principles and Management; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Henrysson, M.; Swain, R.B.; Swain, A.; Nerini, F.F. Sustainable development goals and wellbeing for resilient societies: Shocks and recovery. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: The centrepiece of competing and complementary frameworks. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trim, P.R.J.; Trim, R.C.L. Reflecting on Social Inclusion Through Philosophical Discussion: A Sustainable Partnership Framework. Challenges 2025, 16, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16040054

Trim PRJ, Trim RCL. Reflecting on Social Inclusion Through Philosophical Discussion: A Sustainable Partnership Framework. Challenges. 2025; 16(4):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16040054

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrim, Peter R. J., and Richard C. L. Trim. 2025. "Reflecting on Social Inclusion Through Philosophical Discussion: A Sustainable Partnership Framework" Challenges 16, no. 4: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16040054

APA StyleTrim, P. R. J., & Trim, R. C. L. (2025). Reflecting on Social Inclusion Through Philosophical Discussion: A Sustainable Partnership Framework. Challenges, 16(4), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16040054