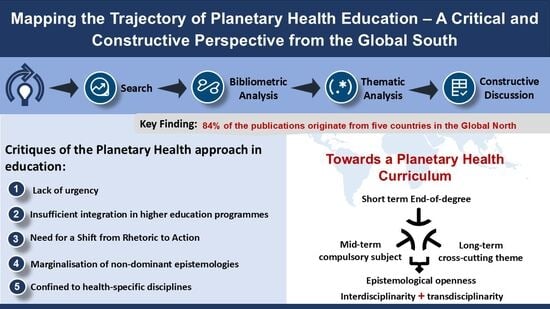

Mapping the Trajectory of Planetary Health Education—A Critical and Constructive Perspective from the Global South

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Architecture

2.1. Critical Theory: A Reflexive Lens

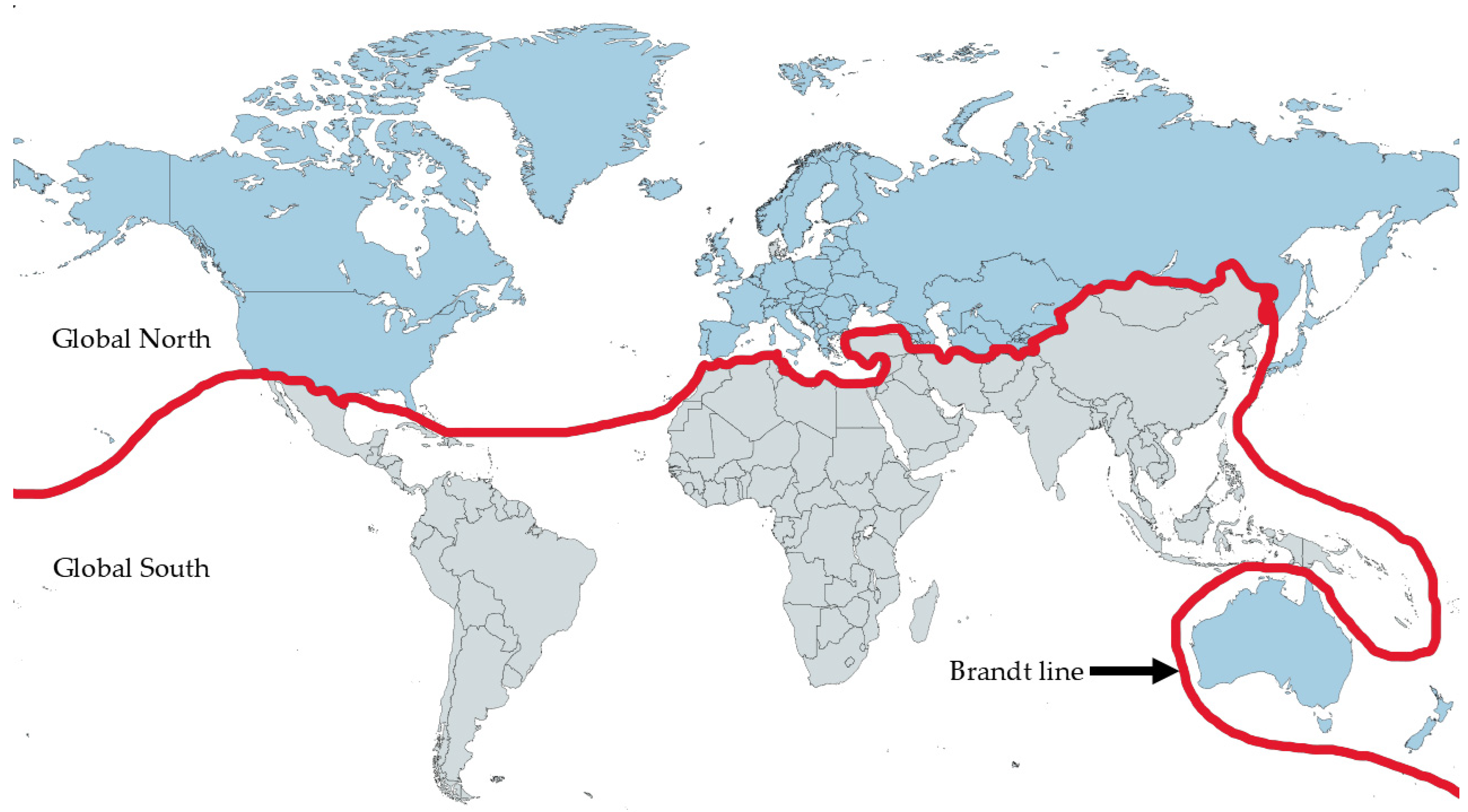

2.2. The Global South: An Epistemic Frontier

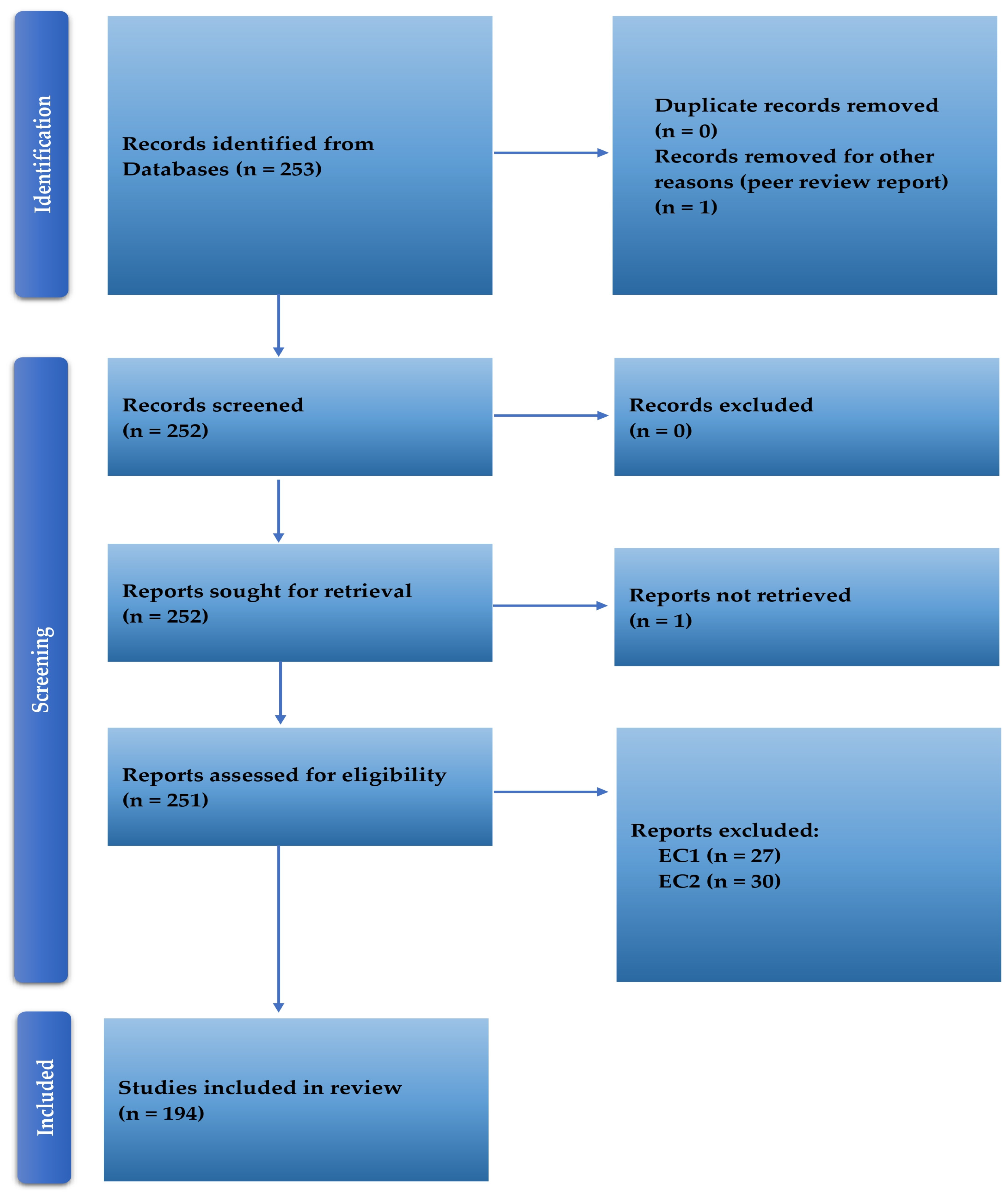

3. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- We classified a sample of studies according to predefined analytical categories (deductive) based on the North–Global–South geopolitical heuristic classification. We selected only articles documenting concrete initiatives applying the planetary health approach in the context of university education or socio-formative community practices, using dialogue-based or participatory methods for adults. A total of 29 articles were selected.

- (b)

- We grouped the findings around new, inductively constructed analytical categories. First, we categorised the 29 initiatives according to their degree of institutionalisation. We distinguished between initiatives that promote greater institutionalisation of PHAE and those that promote emancipatory visions or focus on the participation and creativity of their interlocutors.

- (a)

- Motivation dimension: This is about the desire to promote change. In this study, we aim to reconcile the emphasis on describing phenomena with the need to intervene in order to achieve improvements.

- (b)

- Legitimacy dimension: This refers to the researcher’s acceptance of the legitimacy of the status quo, i.e., the socio-economic structures that influence the phenomenon under study. In this case, we adopt an intermediate position between fully accepting and rejecting the status quo in the planetary health approach.

- (c)

- Epistemological dimension: This refers to the researcher’s understanding of the nature of research and truth. In this case, we assume that we can ascribe plausibility to different positions on the planetary health approach, regardless of whether they assume the status quo or alternative epistemologies.

4. Results

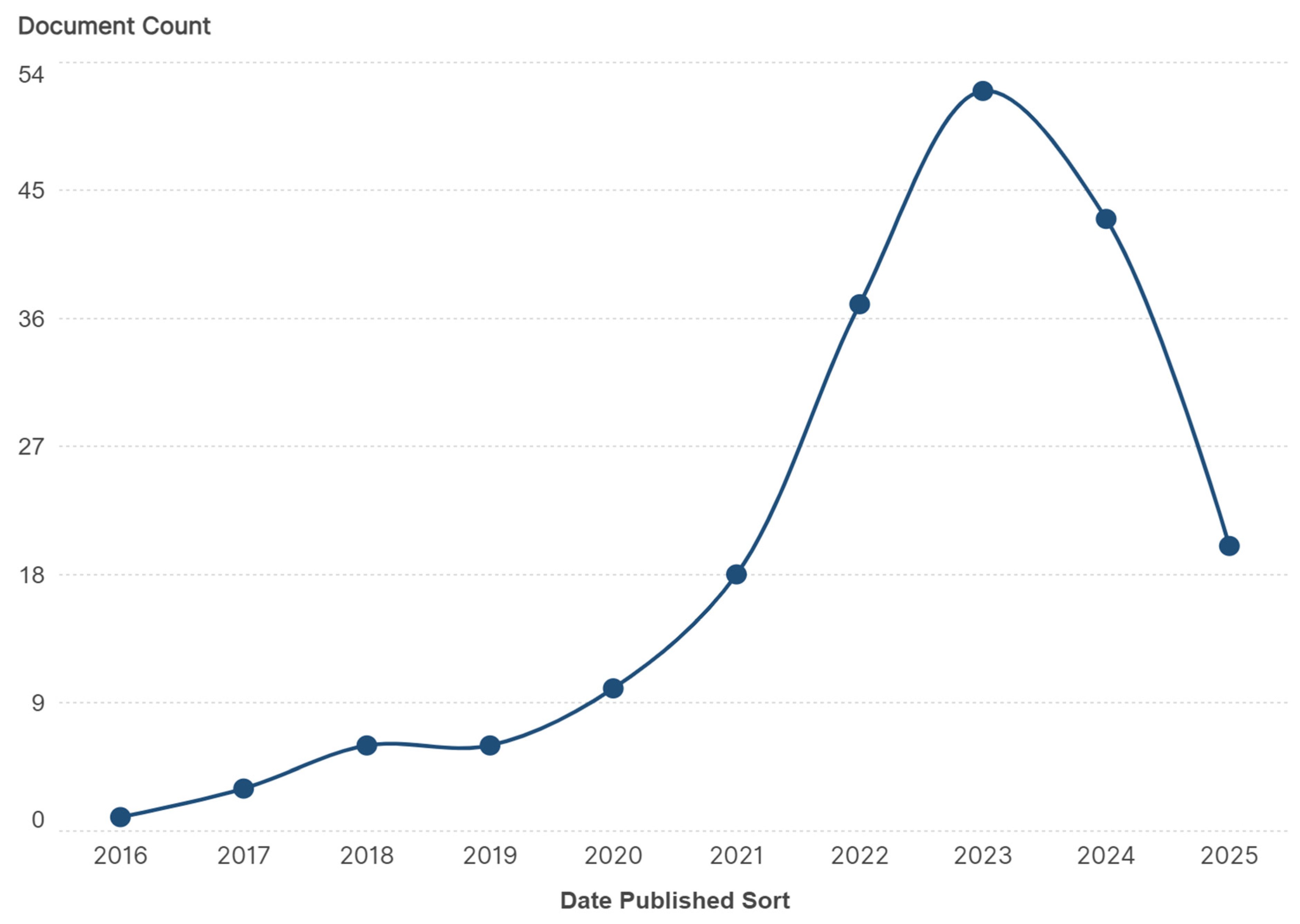

4.1. Bibliometric Analysis

4.1.1. Scholarly Works over Time

4.1.2. Type of Articles

4.1.3. Most Active Countries/Regions

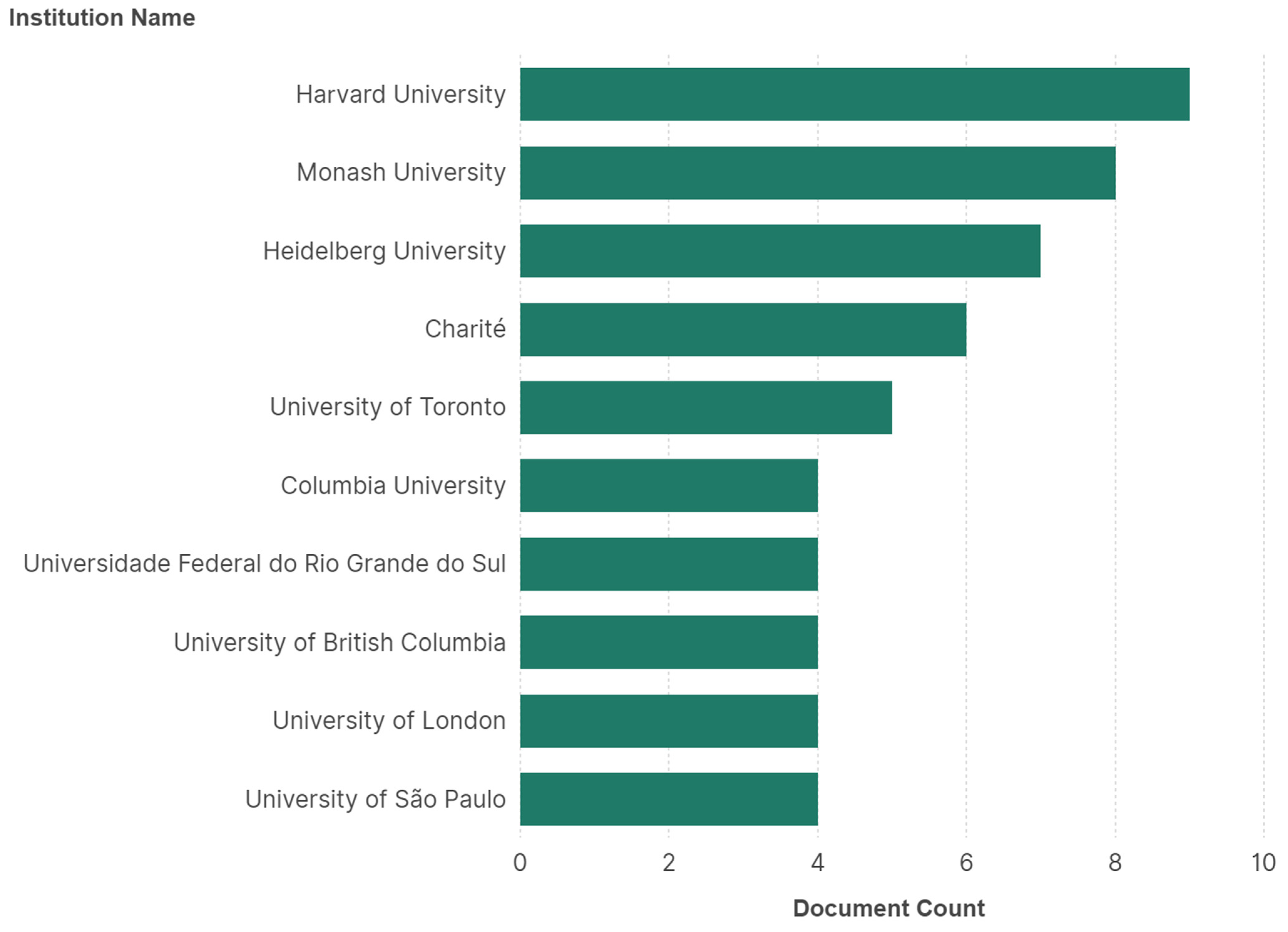

4.1.4. Top Institutions

4.1.5. Co-Occurrence Analysis

4.1.6. Citation Analysis

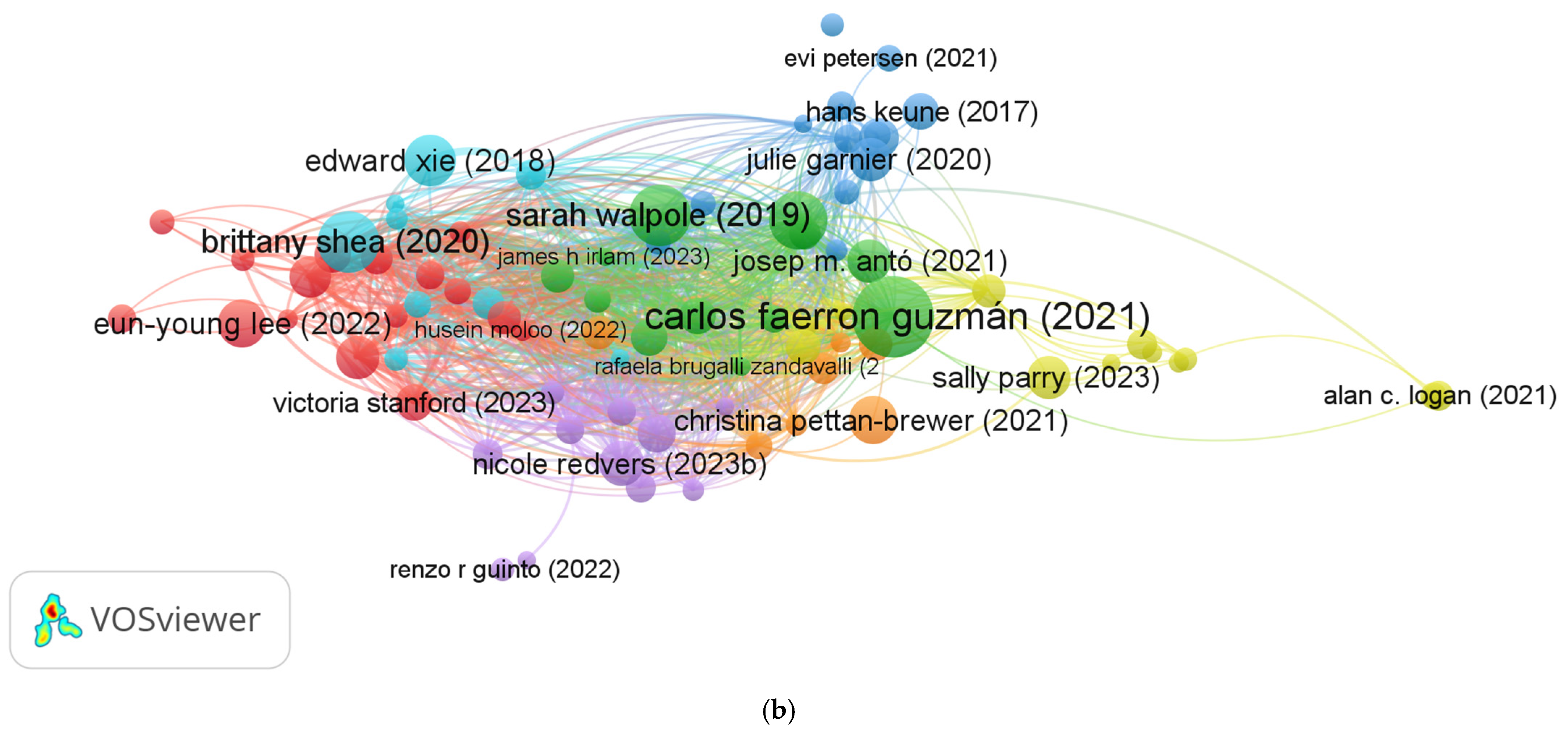

4.1.7. Bibliographic Coupling

4.2. Thematic Analysis

- (a)

- Institutional perspective: these initiatives are characterised by a high degree of curricular institutionalisation, with a predominance of formal university formats such as clinical modules, electives, simulations, serious games, and digital platforms. These experiences integrate planetary health as interdisciplinary content in medical degree programmes, with a focus on climate literacy, hospital sustainability, and clinical competencies. Emphasis is placed on developing emotional resilience, systems thinking, and sustainable decision-making in clinical settings. Most projects are carried out at established universities, which provide access to technological resources and employ active research methods.

- (b)

- Rhizomatic perspective: The initiatives included here favour participatory, community-based, and interprofessional approaches. They are oriented towards social change and ecological–ethical leadership, combining local knowledge, environmental justice, and professional action. They emphasise curriculum co-design, national audits, teacher training, and the use of visual aids in rural areas. Although some of them are linked to universities, their implementation is more emergent and contextualised. They propose transformative models with strong territorial and ethical anchors.

5. Discussion: Towards a Planetary Health Curriculum

- Motivation Dimension

- Legitimacy Dimension

- Epistemological Dimension

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHAE | Planetary Health Approach in Education |

| CT | Critical theory |

| EC | Exclusion Criteria |

| MeSAGE | Medical Student Alliance for Global Education |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| OSCE | Objective Structured Clinical Examination |

| CoPEH-Canada | Canadian Community of Practice in Ecosystem Approaches to Health |

| WONCA | World Organization of Family Doctors |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ECHO | Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes |

| MOOC | Massive Open Online Course |

References

- Prescott, S.L.; Logan, A.C.; Albrecht, G.; Campbell, D.E.; Crane, J.; Cunsolo, A.; Holloway, J.W.; Kozyrskyj, A.L.; Lowry, C.A.; Penders, J.; et al. The Canmore Declaration: Statement of Principles for Planetary Health. Challenges 2018, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, A.C.; Berryessa, C.M.; Callender, J.S.; Caruso, G.D.; Hagenbeek, F.A.; Mishra, P.; Prescott, S.L. The Land That Time Forgot? Planetary Health and the Criminal Justice System. Challenges 2025, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyoud, S.; Zyoud, S.H. One Health and Planetary Health Research Landscapes in the Arab World. Sci. One Health 2025, 4, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L.; Logan, A.C. Planetary Health: From the Wellspring of Holistic Medicine to Personal and Public Health Imperative. Explore 2019, 15, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, C.D. Grand (Meta) Challenges in Planetary Health: Environmental, Social, and Cognitive. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1373787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsan, F.R.; Bloomfield, J.G.; Monrouxe, L.V. Triple Planetary Crisis: Why Healthcare Professionals Should Care. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1465662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskopf, S.R.; Isbell, F.; Arce-Plata, M.I.; Di Marco, M.; Harfoot, M.; Johnson, J.; Lerman, S.B.; Miller, B.W.; Morelli, T.L.; Mori, A.S.; et al. Biodiversity Loss Reduces Global Terrestrial Carbon Storage. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiens, J.J.; Saban, K.E. Questioning the Sixth Mass Extinction. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2025, 40, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, R.A.; Wilcove, D.S. Global Biodiversity Loss from Outsourced Deforestation. Nature 2025, 639, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.S.; Pivor, J.I.; Saraiva, A.M. The São Paulo Declaration on Planetary Health. Lancet 2021, 398, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternova, L.; Verger, L.; Nagy, G.J. Reviewing Planetary Health in Light of Research Directions in One Health. Res. Dir. One Health 2024, 2, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Welton, A.; Chen, J.J.; Byg, B.; Malani, K.; Li, M.L.; Martin, K.D.; Warrier, S. A Grassroots Approach for Greener Education: An Example of a Medical Student-Driven Planetary Health Curriculum. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1013880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, E.; Arfeen, Z.; Chan, C.; Gallivan, S.; Rashid, A. Experiences of Introducing Planetary Health Topics to Medical School Curricula: A Meta-Ethnography. Med. Teach. 2025, 47, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, A.; Nona, F.; Lo, S.N.; Capon, A. Planetary Health: Increasingly Embraced but Not yet Fully Realised. Public Health Res. Pract. 2025, 35, PU24002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiovanni, A. Critical Theory, Ideal Theory, and Conceptual Engineering. J. Soc. Philos. 2025, 56, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, T. Beyond the Nonideal: Why Critical Theory Needs a Utopian Dimension. J. Soc. Philos. 2025, 56, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, P. Introduction to Special Issue: The Critical Theory of Society. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2023, 26, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skillington, T. Thinking beyond the Ecological Present: Critical Theory on the Self-Problematization of Society and Its Transformation. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2023, 26, 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayvon, J.C. Action against Inequalities: A Synthesis of Social Justice & Equity, Diversity, Inclusion Frameworks. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.R. Epistemic Limitations & the Social-Guiding Function of Justice. J. Moral Philos. 2023, 21, 270–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.E.B. Critical Environmental Injustice: A Case Study Approach to Understanding Disproportionate Exposure to Toxic Emissions. Toxics 2024, 12, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahri, M.T. Evidence of the Digital Nomad Phenomenon: From “Reinventing” Migration Theory to Destination Countries Readiness. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H. Theoretical Innovations in International Relations from the Perspective of “Global South”. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, M.; Sergi, B.S.; Muszynski, R.J. Shifting Equilibria: A New Framework Assessing Changing Power Dynamics Between the Global North and Global South. World 2025, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira de Oliveira, T.; Bomfim, M.V.d.J. Funding of Research Agendas about the Global South in Latin America and the Caribbean: Lexicometric and Content Analysis in Latin American Scientific Production. Tapuya Lat. Am. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2023, 6, 2218260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economics. GDP Rankings: 2025. Available online: https://www.worldeconomics.com/Rankings/Economies-By-Size.aspx (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- MapChart. World Map: Simple. Available online: https://www.mapchart.net/world.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Benuyenah, V. Economies as “Makers” or “Users”: Rectifying the Polysemic Quandary with a Dualist Taxonomy. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 3100–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledgerwood, A.; Lawson, K.M.; Kraus, M.W.; Vollhardt, J.R.; Remedios, J.D.; Westberg, D.W.; Uskul, A.K.; Adetula, A.; Leach, C.W.; Martinez, J.E.; et al. Disrupting Racism and Global Exclusion in Academic Publishing: Recommendations and Resources for Authors, Reviewers, and Editors. Collabra Psychol. 2024, 10, 121394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, S. Latin American Participation in the Current Process of Economic Globalization. J. Glob. Aware. 2024, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, A.C. Shaping the Global Future: The Strategic Influence of the Emerging Global South in the New International Order (2022). J. Int. Coop. Dev. 2024, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, J.; ten Brink, T. Causal Mechanisms in the Analysis of Transnational Social Policy Dynamics: Evidence from the Global South. Soc. Policy Adm. 2021, 55, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.d.S. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781315634876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, F.; Ostermann, F.; Guerra, A. South Epistemologies to Invent Post-Pandemic Science Education. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2021, 16, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herber, O.R.; Bradbury-Jones, C.; Okpokiri, C.; Taylor, J. Epistemologies, Methodologies and Theories Used in Qualitative Global North Health and Social Care Research: A Scoping Review Protocol. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, G.; Balzano, M.; Caputo, A.; Pellegrini, M.M. Guidelines for Bibliometric-Systematic Literature Reviews: 10 Steps to Combine Analysis, Synthesis and Theory Development. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2025, 27, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B.C. Critical Responsible Innovation—The Role(s) of the Researcher. J. Responsible Innov. 2024, 11, 2300162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lens Patents and Scholarly Works Database. Available online: https://www.lens.org/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Haddaway, N.R.; Grainger, M.J.; Gray, C.T. Citationchaser: A Tool for Transparent and Efficient Forward and Backward Citation Chasing in Systematic Searching. Res. Synth. Methods 2022, 13, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lens Patents and Scholarly Works Database. Collection: Mapping the Trajectory of Planetary Health Education. Available online: https://www.lens.org/lens/search/scholar/list?collectionId=238231 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, C.A.F.; Aguirre, A.A.; Astle, B.; Barros, E.; Bayles, B.; Chimbari, M.; El-Abbadi, N.; Evert, J.; Hackett, F.; Howard, C.; et al. A Framework to Guide Planetary Health Education. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e253–e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.; Knowlton, K.; Shaman, J. Assessment of Climate-Health Curricula at International Health Professions Schools. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e206609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpole, S.C.; Barna, S.; Richardson, J.; Rother, H.-A. Sustainable Healthcare Education: Integrating Planetary Health into Clinical Education. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e6–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, S.L.; Nusrat, A.; Scott, R.; Nelson, D.; Rogers, H.H.; El-Sherbini, M.S.; Bisram, K.; Vizina, Y.; Warber, S.L.; Webb, D. The Earthrise Community: Transforming Planetary Consciousness for a Flourishing Future. Challenges 2025, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.; Canham, R.; Hughes, K.; Tallentire, V.R. Simulation-Based Education and Sustainability: Creating a Bridge to Action. Adv. Simul. 2025, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Horton, G.; Guppy, M.; Brown, G.; Boulton, J. Pedagogical Strategies for Supporting Learning and Student Well-being in Environmentally Sustainable Healthcare. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1446569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoumou, G.B.; Koppold, D.A.; Wenzel, L.; Schirmaier, A.; Breinlinger, C.; Pörtner, L.M.; Jordan, S.; Schiele, J.K.; Hanslian, E.; Koppold, A.; et al. An Interactive Course Program on Nutrition for Medical Students: Interdisciplinary Development and Mixed-Methods Evaluation. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.P.; Chong, W.; Londono, R.; Cubillo, B.; McCartan, J.; Barbour, L. Equipping Our Public Health Nutrition Workforce to Promote Planetary Health: A Case Example of Tertiary Education Co-Designed with Students. Public Health Nutr. 2025, 28, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, T.; Compagnone, J.; Sudershan, S.; Yunus, M.; Ghouti, L.; Tran, A.; Munro, J.; Haroon, B.; Shetty, N. Planetary Health Rounds: A Novel Educational Model for Integrating Healthcare Sustainability Education into Postgraduate Medical Curricula. J. Clim. Change Health 2025, 22, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwienhorst-Stich, E.-M.; Schlittenhardt, C.; Leutritz, T.; Kleuser, H.; Parisi, S.; König, S.; Simmenroth, A. Pre-Post Evaluation of the Emotions and Motivations for Transformative Action of Medical Students in Germany after Two Different Planetary Health Educational Interventions. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8 (Suppl. 1), S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judson, S.D.; Ripp, K.; Benzekri, N.A.; LaBeaud, A.D.; Veidis, E.; Xie, M.; Tin, A.; Barry, M.; Rabinowitz, P. Medicine for a Changing Planet: Online Clinical Cases in Planetary Health and Infectious Diseases. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, ofae691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais Rodrigues, C.; Papageorgiou, E.; McLean, M. Development of a Suite of Short Planetary Health Learning Resources by Students for Students as Future Health Professionals. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1439392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, M.; Israel, A.; Nusselder, A.; Mattijsen, J.C.; Chen, F.; Erasmus, V.; van Beeck, E.; Otto, S. Drawing a Line from CO2 Emissions to Health—Evaluation of Medical Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Climate Change and Health Following a Novel Serious Game: A Mixed-Methods Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parchure, R.; Ghanekar, A.; Kulkarni, V. Using Participatory Approaches in Climate and Health Education: A Case Report from Rural India. J. Clim. Change Health 2024, 18, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenau, N.; Neumann, U.; Hamblett, S.; Ellrott, T. University Students as Change Agents for Health and Sustainability: A Pilot Study on the Effects of a Teaching Kitchen-Based Planetary Health Diet Curriculum. Nutrients 2024, 16, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichgräber, U.; Ingwersen, M.; Sturm, M.-J.; Giesecke, J.; Allwang, M.; Herzog, I.; von Gierke, F.; Schellong, P.; Kolleg, M.; Lange, K.; et al. Objective Structured Clinical Examination to Teach Competency in Planetary Health Care and Management—A Prospective Observational Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irlam, J.; Reid, S.; Rother, H.-A. Education about Planetary Health and Sustainable Healthcare: A National Delphi Panel Assessment of Its Integration into Health Professions Education in South Africa. Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. 2024, 16, e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, H.B.; Kohlhoff, J.; Lanphier, K.; Yazzie, A.; Kennedy, E.G.; Hoysala, S.; Whitehead, C.; Sircar, M.L.; Gribble, M.O. Tribally Led Planetary Health Education in Southeast Alaska. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e951–e957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.; Raez-Villanueva, S.; Carrière, P.D.; Beauchamp, A.-A.; Bell, I.; Day, A.; Elton, S.; Feagan, M.; Giacinti, J.; Lukusa, J.P.K.; et al. Transformative Learning for a Sustainable and Healthy Future Through Ecosystem Approaches to Health: Insights from 15 Years of Co-Designed Ecohealth Teaching and Learning Experiences. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e86–e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGushin, A.; de Barros, E.F.; Floss, M.; Mohammad, Y.; Ndikum, A.E.; Ngendahayo, C.; Oduor, P.A.; Sultana, S.; Wong, R.; Abelsohn, A. The World Organization of Family Doctors Air Health Train the Trainer Program: Lessons Learned and Implications for Planetary Health Education. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e55–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıyak, Y.S. Blockchain and Holochain in Medical Education from Planetary Health and Climate Change Perspectives. Rev. Española Educ. Médica 2023, 4, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, J.; Mumm, A.; König, S.; Zirkel, J.; Schwienhorst-Stich, E.-M. Concept and Implementation of the Longitudinal Mosaic Curriculum Planetary Health at the Faculty of Medicine in Würzburg, Germany. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2023, 40, Doc33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flägel, K.; Manke, M.; Zimmermann, K.; Wagener, S.; Pante, S.V.; Lehmann, M.; Herpertz, S.C.; Fischer, M.R.; Jünger, J. Planetary Health as a Main Topic for the Qualification in Digital Teaching—A Project Report. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2023, 40, Doc35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, K.; Davy, C.; Maurier, J.; Smith, K.F. Planetary Health—Global Environmental Change and Emerging Infectious Disease: A New Undergraduate Online Asynchronous Course. Challenges 2023, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, R.; Creutzig, F.; Sovacool, B.K.; Shuckburgh, E. Harnessing Human and Machine Intelligence for Planetary-Level Climate Action. npj Clim. Action 2023, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzman, N.F.; Pandey, N.; Norsworthy, K.; Maury, J.-M.; Lord, S.; Tomedi, L.E. Healthcare Sustainability: Educating Clinicians through Telementoring. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasheim, E.T.; Bhopal, A.S.; O’Brien, K.; Lie, A.K.; Nakstad, E.R.; Andersen, L.F.; Hessen, D.O.; Samset, B.H.; Banik, D. Climate Change and Health: A 2-Week Course for Medical Students to Inspire Change. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e12–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattijsen, J.C.; van Bree, E.M.; Brakema, E.A.; Huynen, M.M.T.E.; Visser, E.H.; Blankestijn, P.J.; Elders, P.N.D.; Ossebaard, H.C. Educational Activism for Planetary Health—A Case Example from The Netherlands. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e18–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floss, M.; Abelsohn, A.; Kirk, A.; Khoo, S.-M.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; Umpierre, R.N.; McGushin, A.; Yoon, S. An International Planetary Health for Primary Care Massive Open Online Course. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e172–e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gepp, S.; Jung, L.; Wabnitz, K.; Schneider, F.; Gierke, F.V.; Otto, H.; Hartmann, S.; Gemke, T.; Schulz, C.; Gabrysch, S.; et al. The Planetary Health Academy—A Virtual Lecture Series for Transformative Education in Germany. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e68–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, I.M.; Rupp, I.; de Graaf, I.M.; Kapitein, B.; Timmermans, A.; Weiland, N.H.S. Putting Planetary Health at the Core of the Medical Curriculum in Amsterdam. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e15–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilleczek, K.C.; Terry, M.; MacDonald, D.; Orbinski, J.; Stinson, J. Towards Youth-Centred Planetary Health Education. Challenges 2023, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, F.; Parisi, S.; Simmenroth, A.; Eichinger, M.; Zirkel, J.; König, S.; Jünger, J.; Geck, E.; Schwienhorst-Stich, E.-M. Planetary Health Education in Undergraduate Medical Education in Germany: Results from Structured Interviews and an Online Survey within the National PlanetMedEd Project. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1507515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmqvist, E.; Oudin, A. Bridging Disciplines-Key to Success When Implementing Planetary Health in Medical Training Curricula. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1454729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokmic-Tomkins, Z.; Barbour, L.; LeClair, J.; Luebke, J.; McGuinness, S.L.; Limaye, V.S.; Pillai, P.; Flynn, M.; Kamp, M.A.; Leder, K.; et al. Integrating Planetary Health Education into Tertiary Curricula: A Practical Toolbox for Implementation. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1437632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, O.B.; Walsh, A.; Stanistreet, D. Factors Influencing the Integration of Planetary Health Topics into Undergraduate Medical Education in Ireland: A Qualitative Study of Medical Educator Perspectives. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.J.; Ardoin, N.M.; Eames, C.; Monroe, M.C. Agency in the Anthropocene: Education for Planetary Health. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e117–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, G.; Wise, S.; Bedi, G.; Kickett, R. Embedding Indigenous Knowledges and Voices in Planetary Health Education. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e97–e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redvers, N.; Lokugamage, A.U.; Barreto, J.P.L.; Bajracharya, M.B.; Harris, M. Epistemicide, Health Systems, and Planetary Health: Re-Centering Indigenous Knowledge Systems. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manteaw, B.O.; Enu, K.B. Mindscapes and Landscapes: Framing Planetary Health Education and Pedagogy for Sustainable Development in Africa. Glob. Transit. 2025, 7, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbonizio, J.; Ho, S.S.Y.; Reid, A.; Simmons, M. Women’s Leadership Matters in Education for Planetary Health. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2024, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, G.H.; Rech, R.S.; Stein, A.T. Planetary Health Curriculum in Higher Education: Scoping Review. Int. Health Trends Perspect. 2023, 3, 316–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeiro-Silva, Y.; Ferrada, M.T.; Silva, I.; Ramirez, J. Global Environmental Change and Planetary Health in the Curriculum of Undergraduate Health Professionals in Latin America: A Review. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irlam, J.H.; Scheerens, C.; Mash, B. Planetary Health and Environmental Sustainability in African Health Professions Education. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2023, 15, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, P.A.; Jannavada, H. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Medical Students in a Metropolitan City on the Role of Planetary Health in Medicine and the Impact of Climate Change on Health through a Survey. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2023, 10, 3756–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P.; Paucar-Caceres, A.; Cavalcanti-Bandos, M.F.; Nunes, C.; Vílchez-Román, C.; Quispe-Prieto, S.; Brandli, L.L. Planetary Health and Health Education in Brazil: Towards Better Trained Future Health Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidu, T.; Ramani, S. Transforming Global Health Professions Education for Sustainability. Med. Educ. 2024, 58, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, M.; Phelps, C.; Moro, C. Medical Students as Advocates for a Healthy Planet and Healthy People: Designing an Assessment That Prepares Learners to Take Action on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Med. Teach. 2023, 45, 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaduzzaman, M.; Ara, R.; Afrin, S.; Meiring, J.E.; Saif-Ur-Rahman, K.M. Planetary Health Education and Capacity Building for Healthcare Professionals in a Global Context: Current Opportunities, Gaps and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeder, T.M. (Re)Conceptualising Coach Education and Development: Towards a Rhizomatic Approach. Sports Coach. Rev. 2024, 13, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; Dias, B.F.d.S.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G.J.; Lescher Soto, I.; Vidal, B.; Verger, L. Planetary health: A flexible health, environmental and social sciences curriculum approach is needed. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2025; accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Redvers, N.; Yellow Bird, M.; Quinn, D.; Yunkaporta, T.; Arabena, K. Molecular Decolonization: An Indigenous Microcosm Perspective of Planetary Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Morales, S.; Fröberg, A. Towards a More Sustainable Future: Simple Recommendations to Integrate Planetary Health into Education. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e868–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochem, C.; von Sommoggy, J.; Hornidge, A.-K.; Schwienhorst-Stich, E.-M.; Apfelbacher, C. Planetary Health Literacy: A Conceptual Model. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 980779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, D. In the Company of the Unknown: Cultivating Curiosity for Ecological Renewal. Challenges 2025, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankema, E.; de Haas, M.; van Waijenburg, M. Inequality Regimes in Africa from Pre-Colonial Times to the Present. Afr. Aff. 2023, 122, 57–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajpeyi, A. A history of caste in South Asia: From pre-colonial polity to biopolitical state. In Shared Histories of Modernity; Huri, H., Perdue, P.C., Eds.; Routledge: New Delhi, India, 2020; pp. 299–320. [Google Scholar]

- Mago, A.; Dhali, A.; Kumar, H.; Maity, R.; Kumar, B. Planetary Health and Its Relevance in the Modern Era: A Topical Review. SAGE Open Med. 2024, 12, 20503121241254231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, S.S.; Potter, T.; Wagner, J.; Xie, M. Clinicians for Planetary Health. One Earth 2022, 5, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Parisi, S.; Wabnitz, K.; Simmenroth, A.; Schwienhorst-Stich, E.-M. Ten Characteristics of High-Quality Planetary Health Education-Results from a Qualitative Study with Educators, Students as Educators and Study Deans at Medical Schools in Germany. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1143751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardani, J.; Bos, J.J.A.; Ramirez-Lovering, D.; Capon, A.G. Towards a Practice Framework for Transdisciplinary Collaboration in Planetary Health. Glob. Sustain. 2024, 7, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redvers, N.; Celidwen, Y.; Schultz, C.; Horn, O.; Githaiga, C.; Vera, M.; Perdrisat, M.; Plume, L.M.; Kobei, D.; Kain, M.C.; et al. The Determinants of Planetary Health: An Indigenous Consensus Perspective. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e156–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redvers, N.; Lockhart, F.; Zoe, J.B.; Nashalik, R.; McDonald, D.; Norwegian, G.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Tonkin-Crine, S. Indigenous Elders’ Voices on Health-Systems Change Informed by Planetary Health: A Qualitative and Relational Systems Mapping Inquiry. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e1106–e1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, S.B.; Myers, S.S.; Golden, C.D. Cross-Cutting Principles for Planetary Health Education. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e192–e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, F.; Wilhelm, O. What You Need to Know about the World. Toward a Taxonomy of Planetary Health Knowledge. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1564555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astle, B. The Triple Planetary Health Crisis: Nursing Leadership in Championing the Integration of Planetary Health in Canadian Nursing Education. Qual. Adv. Nurs. Educ. Avancées Form. Infirm. 2024, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Salazar, C.; Marín-Carvajal, I.; García, M.A.; Fox, K.; Chilton, M. Earth Rights for the Advancement of a Planetary Health Agenda. Health Educ. Behav. 2024, 51, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jochem, C.; von Sommoggy, J.; Hornidge, A.-K.; Schwienhorst-Stich, E.-M.; Apfelbacher, C. Planetary Health Literacy as an Educational Goal Contributing to Healthy Living on a Healthy Planet. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1464878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Article | No. |

|---|---|

| Original research articles | 60 |

| Review articles | 36 |

| Theory articles, essays and perspectives | 21 |

| Comments | 20 |

| Viewpoints | 19 |

| Case reports | 13 |

| Opinion articles | 7 |

| Conference reports | 6 |

| Abstracts | 4 |

| Editorials | 4 |

| Meeting Abstracts | 3 |

| Short Communications | 1 |

| Total | 194 |

| Rank | Source | Documents | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Lancet. Planetary Health | 29 | 709 |

| 2 | Frontiers in public health | 16 | 251 |

| 3 | Challenges | 15 | 67 |

| 4 | Sustainability | 5 | 65 |

| 5 | The Journal of Climate Change and Health | 5 | 64 |

| 6 | Sustainable Earth Reviews | 5 | 56 |

| 7 | BMC Medical Education | 8 | 33 |

| 8 | Frontiers in Medicine | 6 | 9 |

| Analytical Category (Deductive) | Initiative | Country | Source | Description | Analytical Category (Inductive) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global North | The Earthrise Community | International | [46] | A contemplative community fostering cultural and spiritual transformation for planetary health through storytelling, emotional intelligence, ancestral wisdom, and creative practices. It convenes monthly forums, creative workshops, and intercultural dialogues to cultivate ecological belonging and regenerative educational practices. | Rhizomatic perspective |

| Global North | Sustainable Simulation-Based Education Toolkit | United Kingdom | [47] | A toolkit helping educators embed planetary health into simulation-based learning, reduce environmental impact, and model sustainable clinical behaviours through scenario design, resource audits, faculty training, waste reduction, and low-carbon simulation practices. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Sustainable Healthcare Curriculum–Joint Medical Program | Australia | [48] | A four-week course integrating planetary health into medical education, addressing climate-related risks, eco-anxiety, and sustainable practice. Grounded in Self-Determination Theory, it includes modules on ecosystems, clinical adaptation, and health policy leadership. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Nutrition and Planetary Health–Elective Course | Germany | [49] | A two-week course linking nutrition to planetary health, exploring food systems, sustainable diets, and culinary medicine. It employs interactive, interdisciplinary methods, including case-based learning, simulation, and self-experimentation, to address the clinical, ecological, and sociopolitical dimensions of nutrition. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Planetary Health Workshop–Monash University | Australia | [50] | A co-designed workshop for nutrition students to build advocacy skills and integrate Indigenous perspectives into public health nutrition through reflection tasks, scenario-based dialogue, and interactive activities fostering values-driven, practice-oriented learning. | Rhizomatic perspective |

| Global North | Planetary Health Rounds–Residency Curriculum | Canada | [51] | Case-based sessions where residents estimate Greenhouse Gas emissions from clinical care using lifecycle analysis tools and real-world converters, fostering sustainable decision-making and critical reflection on avoidable interventions. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Planetary Health Education–Würzburg University | Germany | [52] | A university programme combining lectures and optional courses that improved students’ emotional resilience and climate motivation through action-oriented content, values-based reflection, and interactive formats fostering agency and planetary health engagement. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Medicine for a Changing Planet–Online Series | United States | [53] | A free online curriculum using clinical cases to teach planetary health, zoonoses, and pandemic preparedness. It features 11 case studies designed around Bloom’s taxonomy, integrating social–environmental history, host–environment dynamics, and actionable steps for achieving sustainable and equitable healthcare. | Institutional perspective |

| Both | Planetary Health Bricks–ScholarRx/Medical Student Alliance for Global Education (MeSAGE) | International | [54] | 14 short online modules co-developed by students from 11 countries, covering air pollution, climate migration, and sustainable systems. Hosted on ScholarRx, these open-access bricks utilise multimedia, case-based learning, and peer-driven content to teach foundational concepts in planetary health, promote equity, and support flexible curricular integration across global health education programmes. | Rhizomatic perspective |

| Global North | Drawing a Line from Carbon Dioxide (CO2) to Health–Serious Game | Netherlands | [55] | A game embedded in medical training to teach climate–health links through experiential learning and peer discussion. Using visual cards and collaborative rounds, students explore causal pathways between environmental change and health outcomes, reflect on emotional responses, and examine their professional responsibilities in climate adaptation, mitigation, and advocacy. | Institutional perspective |

| Global South | Participatory Climate and Health Education | India | [56] | A community-based initiative in rural villages using visual tools to empower local climate–health action. Through participatory dialogues, pictorial storytelling, causal loop diagrams, and timeline mapping, communities explored lived vulnerabilities, prioritised local concerns, and co-developed micro-scale adaptation strategies such as early warning systems and protective measures for agricultural workers. | Rhizomatic perspective |

| Global North | Planetary Health Diet Curriculum | Germany | [57] | A pilot course combining seminars and cooking sessions to teach sustainable eating based on the EAT-Lancet diet. Delivered over seven weeks, the programme utilised a flipped-classroom model and a teaching kitchen to enhance planetary health literacy, reformulate student recipes for lower carbon footprints, and foster self-efficacy through hands-on practice and communal reflection. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Planetary Health Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) Elective Course | Germany | [58] | An OSCE-based course trains students to counsel on climate-related health risks and sustainable prescribing. Combining online modules, peer-led workshops, and simulated clinical stations, the programme builds planetary health competencies and communication skills through experiential learning, actor-based roleplay, and structured feedback. Scenarios include dietary advice, prescribing alternatives, and public health dialogue on vector-borne disease. | Institutional perspective |

| Global South | Education for Sustainable Healthcare Delphi Panel Study | South Africa | [59] | Aligns planetary health learning with African Medical Education Standards (AfriMEDS), serving as a strategic tool for curricular reform and eco-ethical leadership. Through a Delphi-based consensus process, South African educators identified context-relevant learning objectives, activities, and assessments to embed planetary health and sustainable care into health professions education, fostering systemic thinking and interprofessional engagement. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Sitka Tribe of Alaska Summer Internship Programme | United States | [60] | Sitka Tribe of Alaska’s paid summer planetary health internship fuses Tlingit mentorship, environmental toxin monitoring, laboratory research, and community engagement. Rooted in Indigenous knowledge and scientific practice, the programme empowers youth to address shellfish toxin risks, develop culturally grounded research projects, and pursue careers in planetary health through intergenerational learning and place-based stewardship. | Rhizomatic perspective |

| Global North | Canadian Community of Practice in Ecosystem Approaches to Health (CoPEH-Canada) Ecosystem Health Training | Canada | [61] | A transdisciplinary programme using land-based and hybrid formats to teach systems thinking and Indigenous knowledge. Developed over 15 years by CoPEH-Canada, it blends place-based case studies, talking circle methods, and experiential learning to foster ecohealth competencies. Its iterative pedagogy—centred on Head, Hands, and Heart—invites learners as co-creators, continuously refining content through reflection, dialogue, and real-world engagement. | Rhizomatic perspective |

| Both | World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) Air Health Train-the-Trainer | International | [62] | A pilot programme training professionals in low- and middle-income countries on air pollution and climate, enabling 370+ educational activities including workshops, clinical rounds, school programmes, media outreach, citizen science, and advocacy. | Institutional perspective |

| Global South | Web3 Technologies in Medical Education | Turkey | [63] | A conceptual proposal advocating for decentralised, energy-efficient technology in medical education, aligned with planetary health. Drawing on sustainability concerns, it recommends Holochain over energy-intensive blockchain models, promoting agent-centric architectures that enhance data integrity, privacy, and scalability. The proposal urges educators and policymakers to adopt Web3 technologies that minimise environmental impact while supporting secure, transparent, and equitable learning ecosystems. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Longitudinal Mosaic Curriculum | Germany | [64] | A curriculum integrating planetary health across all semesters and disciplines at Würzburg’s Faculty of Medicine. The mosaic model embeds content through curricular mapping, interdisciplinary consultations, and strategic injection points across 26 specialities. It follows a spiral structure, fostering a holistic understanding of environmental change and health, with visual markers to enhance thematic coherence. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Planetary Health in Medical Education (ME Elective) | Germany | [65] | An online elective empowering students to design seminars and promote interdisciplinary learning. Implemented across 13 medical faculties in Germany, the course trains students in planetary health content, digital pedagogy, and peer-led teaching. Using flipped-classroom methods and supervised lesson planning, it fosters curricular innovation, interfaculty networking, and the development of student-led planetary health education through a structured, four-phase model. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | BIOL 1455–Planetary Health: Global Environmental Change and Emerging Infectious Disease Course | United States | [66] | An asynchronous online undergraduate course exploring links between environmental change and infectious disease, designed to foster planetary health literacy across disciplines. Delivered at Brown University, it employs an inclusive, project-based pedagogy—utilising micro-lectures, literature analysis, and student-designed public communication—to foster systems thinking and solution-oriented engagement. Evaluations show increased competence and a shift from pessimism to cautious optimism. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Human and Artificial Intelligence (AI) for Climate Action Epistemic Web | International | [67] | A framework proposing human-in-the-loop AI for equitable climate mitigation and planetary health knowledge. It calls for aligning machine intelligence with global epistemic networks to reduce bias, embed data justice, and support socially grounded decision-making. By integrating diverse human perspectives and recognising social tipping points, the approach enables low-carbon, trustworthy AI systems that foster inclusive, context-sensitive climate action. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO)–Climate Change Telementoring Series | United States | [68] | A virtual programme educating health professionals on climate-health impacts and healthcare decarbonisation. Delivered through an eight-week telementoring series, the programme utilised case-based learning and live simulation to develop knowledge, communication skills, and interprofessional collaboration. Participants explored evidence-based strategies for sustainable clinical practice, workplace advocacy, and systemic change, forming a community of practice to advance low-carbon healthcare. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Climate Change and Health–2-week Course | Norway | [69] | A multidisciplinary course combining lectures, workshops, and student projects to inspire climate action. Delivered online over two weeks at the University of Oslo, it explored climate-health links through interdisciplinary teaching, stakeholder dialogue, and student-led communication projects. Designed to empower future clinicians as planetary health advocates, the course emphasised effective messaging, systems thinking, and real-world engagement with diverse voices and lived experiences. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | GREENER Collective | Netherlands | [70] | A grassroots movement advocating for planetary health in Dutch healthcare curricula through policy and education. GREENER, a decentralised and multidisciplinary collective, advances this mission through curriculum audits, national conferences, stakeholder roadmaps, and strategic advocacy. By mobilising students, clinicians, and educators, it fosters systemic transformation towards sustainable, resilient healthcare education rooted in civic responsibility and scientific evidence. | Rhizomatic perspective |

| Global South | Planetary Health for Primary Care–Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) | Brazil | [71] | A free MOOC using creative arts and case studies to train primary care professionals in planetary health. Developed for a global audience in the Global South, the course combines clinical and community interventions with rhizomatic, spiral learning to foster critical reflection and transdisciplinary action. Through modules on climate-sensitive diseases, mental health, and sustainable food systems, it equips frontline practitioners with inclusive, context-aware strategies for planetary health advocacy and care. | Rhizomatic perspective |

| Global North | Planetary Health Academy–Online Lecture Series | Germany | [72] | A free lecture series promoting ecological awareness and advocacy through interactive sessions. The Planetary Health Academy offers open-access virtual conferences and workshops designed to foster transformative learning, ecological responsibility, and engagement in the health sector. Through interdisciplinary content, reflective dialogue, and community-led action strategies, it empowers participants to reduce ecological footprints and expand their handprints—mobilising knowledge, imagination, and implementation for systemic change. | Rhizomatic perspective |

| Global North | Planetary Health Module–University of Amsterdam | Netherlands | [73] | A module embedded in clinical training using blended learning to foster climate literacy and resilience. Developed at the University of Amsterdam, it combines flipped classroom strategies, Bloom’s taxonomy, and practical hospital-based assignments to integrate planetary health into everyday clinical practice. Through interdisciplinary teaching, ecological footprint analysis, and student-led infographics, the module equips future health professionals with the tools, mindset, and agency to lead sustainable transformation in healthcare systems. | Institutional perspective |

| Global North | Planetary Health Film Lab | Canada | [74] | A week-long Canadian programme empowering young adults to produce documentaries that illuminate planetary health challenges and advocate climate justice. Rooted in transdisciplinary and youth-centred pedagogy, the Planetary Health Film Lab combines critical reflection, community storytelling, and Freirean conscientisation to foster ecological awareness and political agency. Participants engage in intensive workshops and produce short films that are disseminated through the Youth Climate Report, a United Nations-affiliated platform designed to influence global climate policy. | Rhizomatic perspective |

| Analytical Category | Descriptors | Country | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited curricular integration | Most planetary health instruction is delivered through non-compulsory modules. | Germany | [75] |

| In some institutions, the time allocated for teaching planetary health is limited or altogether absent. | International | [76] | |

| Lack of specific accreditation standards | International | [77] | |

| Lack of scalability | Planetary health courses reach only a minority of students | Germany | [75] |

| Knowledge of the subject is often tied to a specific individual or to personal experience. | International | [76] | |

| Institutional inertia | Lack of explicit support from senior leadership is a crucial factor in legitimising curricular change. Perceived lack of relevance of planetary health | Ireland | [78] |

| Faculty members often lack the knowledge to teach this emerging subject | International | [76] | |

| Lack of interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity | Artificial disciplinary boundaries have inhibited students’ learning and participation. | International | [79] |

| Lack of urgency | The overall sense of urgency is weak and fragmented. | Netherlands | [70] |

| Lack of Advanced Cognitive Skills. | Deficits in transformative competencies such as climate communication, scientific communication, transdisciplinary collaboration, project management, and sustainable healthcare. | Germany | [75] |

| Need for a Shift from Rhetoric to Action | Lack of concrete sustainability plans. Need to empower meaningful, measurable, and achievable actions. | International | [47] |

| Inconsistency between knowledge and sustainable application. Teaching about problems without addressing possible solutions is ineffective. | Canada | [61] |

| Analytical Category | Descriptors | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Technoscientific reductionism | Traditional technocratic and reductionist approaches fail to account for the profound interconnections between human well-being and ecological systems. Scientific knowledge is essential for understanding the complexity of the Anthropocene, but it is insufficient on its own to inspire the profound and systemic changes required. | [46] |

| Marginalisation of non-dominant epistemologies | The knowledge imparted in PHAE has primarily been limited to specific forms of understanding rooted in Western epistemology. | [80] |

| Epistemicide is an ongoing process that discredits knowledge beyond the Euro-Western sphere, while reinforcing the legitimacy and elevating the status of Eurocentric epistemic traditions. | [81] | |

| Dominant epistemological perspectives reproduce unsustainable values—materialism, individualism, and the exploitation of nature for economic gain—which have fuelled both environmental degradation and social inequalities. | [46] | |

| Need to decolonise learning through the integration of Indigenous knowledge systems and voices. | [80] | |

| Overemphasis on human-centred domains | Colonial educational legacies, rooted in anthropocentric paradigms, overlook the interconnection between human and non-human systems, promoting skewed visions of development that undermine systemic interdependence. | [82] |

| Forced disconnection between health systems and Nature. | [81] | |

| Suppression of emotional and spiritual dimensions | Emotional disconnection and a lack of care, alongside selfishness and greed, constitute profound dimensions of the environmental crisis that cannot be addressed solely through logic and science. | [46] |

| Crisis-centred environmental messaging | Much of the climate and environmental discourse is framed in terms of crisis and catastrophe, often eliciting anxiety, despair, and a sense of helplessness. | [46] |

| Lack of ecofeminist perspectives | Planetary health scholarship has underexplored the narratives and contributions of women leading transformative change within the field. | [83] |

| Analytical Category | Description | Country/Region | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curricular Peripheralization | Documented planetary health approach curricula in Global South universities are scarce and primarily result from collaborations with institutions in the Global North. | Global South | [84] |

| Curricular Underdevelopment | Latin American universities lack planetary health courses, and environmental education is insufficient, with a minimal focus on climate change and environmental health. | Latin America | [85] |

| Systemic Disempowerment | The planetary health approach lacks educational leadership, public awareness, and curricular integration, leaving professionals ill-equipped to drive transformative environmental health action. | Africa | [86] |

| Epistemological constraints | Colonial educational legacies, erosion of Indigenous knowledge, cognitive disconnection from ecological systems, disciplinary fragmentation, and limited curricular links between human and ecosystem health persist across PHAE. | Africa | [82] |

| Institutional Apathy and Pedagogical Weakness | Faculty training is weak, thematic coverage is limited, and institutional interest is low; active engagement in PHAE remains minimal. | India | [87] |

| Curricular Stagnation and Governance Barriers | The integration of the planetary health approach in undergraduate and postgraduate education is slow, lacking curricular guidelines and hindered by governance barriers and contextual disparities that deepen health education inequalities. | Brazil | [88] |

| Symbolic Marginalisation and Pedagogical Disengagement | Planetary health approach lacks trained educators, staff interest, and leadership; academic structuring is weak, and hidden curricula often undermine its urgency and educational legitimacy. | South Africa | [59] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soto, I.L.; Vidal, B.; Verger, L.; Nagy, G.J. Mapping the Trajectory of Planetary Health Education—A Critical and Constructive Perspective from the Global South. Challenges 2025, 16, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16040050

Soto IL, Vidal B, Verger L, Nagy GJ. Mapping the Trajectory of Planetary Health Education—A Critical and Constructive Perspective from the Global South. Challenges. 2025; 16(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoto, Isaías Lescher, Bernabé Vidal, Lorenzo Verger, and Gustavo J. Nagy. 2025. "Mapping the Trajectory of Planetary Health Education—A Critical and Constructive Perspective from the Global South" Challenges 16, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16040050

APA StyleSoto, I. L., Vidal, B., Verger, L., & Nagy, G. J. (2025). Mapping the Trajectory of Planetary Health Education—A Critical and Constructive Perspective from the Global South. Challenges, 16(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16040050