1. Introduction

Greenwashing refers to the practice of businesses making misleading or false claims about the environmental benefits of their products, services, or operations. This deceptive marketing strategy exploits consumers’ growing preference for sustainable and ethically produced goods, leading them to believe they are making environmentally responsible choices when, in reality, they may not be [

1] Greenwashing therefore leads to a deterioration of trust in brands [

2]. This issue is particularly significant in the food industry, including seafood products such as tinned tuna, where sustainability claims can significantly influence purchasing decisions. Common greenwashing practices include vague labelling, misleading certifications, and self-produced ecolabels that lack third-party verification [

3]. By making misleading claims, these brands harm consumer trust and disadvantage businesses that are genuinely investing in sustainable practices. It is important to understand the implications for the broader planetary health context, recognising the critical interdependence between human wellbeing and the health of the planet’s ecological systems [

4,

5]. In addition, in marine food systems such as tuna fishing, misinformation through greenwashing impedes sustainable fishery management, undermining progress toward SDG 14 (life below water), and negatively impacts food system resilience and biodiversity conservation [

6].

Prior literature shows that the already available greenwashing indices are based on sustainability claims in company annual reports, sustainability reports, annual general meeting minutes, company websites, and analyst reports (for example, Gompers et al. [

7], Cheung et al. [

8]). None of these sources are easily accessible to an average consumer and are therefore unlikely to influence purchasing decisions. In addition, an index specifically designed for the tuna fishing industry is non-existent in the current literature.

In order to fill this gap, the primary objective of our study is to construct a greenwashing index, designed to measure the quality of on-pack disclosure practices of tuna brands in Australia. By using a structured yes/no response system, this index evaluates the on-pack sustainability claims of canned tuna products against the ACCC’s principles for making environmental claims [

9]. The ACCC’s report outlines eight principles for making trustworthy environmental claims, which can serve as a framework for assessing tuna brand labels.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [

9] identified greenwashing as a growing concern in the Australian market. In their report, the ACCC found that 57% of businesses surveyed were making environmental claims that raised concerns regarding their truthfulness, accuracy, or clarity. These concerns similarly ranged from vague and unqualified claims to misleading use of trust marks and third-party certifications. To address this issue, the ACCC is increasing its enforcement efforts under the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), aiming to hold businesses accountable for misleading or deceptive environmental claims. The commission has emphasised the need for businesses to provide clear, evidence-backed, and transparent sustainability claims that do not exaggerate environmental benefits or omit critical information.

The ACCC’s report outlines eight principles for making trustworthy environmental claims, which can serve as a framework for assessing tuna brand labels:

Make accurate and truthful claims—ensuring that sustainability statements are factually correct and not misleading.

Have evidence to back up claims—requiring brands to provide verifiable proof of their sustainability credentials.

Do not hide or omit important information—avoiding selective disclosure that creates an overly positive impression.

Explain any conditions or qualifications on claims—clarifying any limitations or specific conditions under which claims apply.

Avoid broad and unqualified claims—preventing misleading statements like ‘100% sustainable’ without context.

Use clear and easy-to-understand language—making labels accessible and comprehensible to consumers.

Ensure visual elements do not give the wrong impression—avoiding misleading use of colours, images, or logos that suggest greater sustainability than actually exists.

Be direct and open about sustainability transitions—encouraging transparency about future goals and current limitations.

We adapt the Gompers et al. [

7] scoring scheme to evaluate the extent to which tuna brands comply with seven of these eight Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s (ACCC) principles for environmental marketing claims. This study excluded the fourth ACCC principle—“Explain any conditions or qualifications on claims”—from the scoring process because, due to the underlying nature of this principle and the specific context of canned tuna labelling, we found it to be largely inapplicable. Principle 4 is most relevant where environmental claims are subject to clear qualifications relating to the actions and circumstances of the consumer (e.g., recyclability claims conditional on access to local facilities). By contrast, the sustainability claims assessed here focused primarily on fishing practices and sourcing standards, which relate to the brand’s responsibilities and are typically presented as absolute rather than conditional. In practice, we did not observe meaningful instances where these qualifications relating to consumers were apparent or could be evaluated, and therefore incorporating Principle 4 would have introduced no additional variation in scores across brands. For this reason, we restricted the analysis to the remaining seven principles, which were more directly relevant to the claims observed in this product category.

While these principles offer a comprehensive framework for identifying greenwashing, their application to the seafood sector necessitates contextual refinement. The unique complexities of seafood supply chains, such as the variability in fishing practices and certification standards, require a tailored approach. For example, claims of sustainable fishing can be assessed against verifiable third-party certifications like the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) or dolphin-safe programmes. However, the effectiveness of such labels depends on their clarity and the extent to which they are understood by consumers, who may not be familiar with the scope or limitations of these certifications. The findings underscore the limitations of a one-size-fits-all regulatory approach and highlight the need for ongoing refinement of these principles to better address sector-specific challenges. By applying the ACCC framework in this context, the study contributes to the development of more nuanced evaluative tools that enhance accountability and transparency in environmental marketing within the seafood industry.

While this study focuses on the ACCC framework, the relevance of developing Greenwashing indices and investigating the performance of consumer brands extends well beyond the Australian context. The ACCC’s principles are closely aligned with international regulatory approaches, including the UK Competition and Markets Authority’s Green Claims Code, the EU’s proposed Green Claims Directive, and the U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s Green Guides. Each of these frameworks emphasises accuracy, evidence, clarity, and transparency in sustainability claims, reflecting a growing global consensus on tackling greenwashing. By grounding our analysis in the ACCC’s recently updated principles, we effectively provide a case study that demonstrates how such regulatory guidance can be operationalised within a high-risk sector like seafood. Importantly, the methods and findings here can inform comparative studies across jurisdictions and contribute to cross-national dialogue on strengthening consumer protection in sustainability labelling. In this way, our work not only advances the understanding of greenwashing in the Australian tuna market but also offers insights relevant to regulators and policymakers internationally.

This paper makes a significant contribution to the sustainability disclosure literature in the following ways. First, it contributes to the anthology of academic studies on the development of sustainability indices [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In creating an index that captures corporate sustainability, studies have utilised the Investor Responsibility Research Center (IRRC)’s corporate governance provisions and the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance to score sustainability claims in companies’ annual reports, sustainability reports, annual general meeting minutes, company websites, and analyst reports (for example, Gompers et al. [

7], Cheung et al. [

8]). Based on current literature, this paper is the first to construct a greenwashing index for the Tuna fishing industry using brands’ on-pack (labelling) sustainability claims. Our index differs from previous studies as we use on-pack claims that influence how customers spend their money. This paper, to our knowledge, is the first study of the on-pack environmental claims on tuna products in Australia. Second, we create items that could be relevant in assessing sustainability claims in other industries, such as electronics and home appliances; textiles, garments, and shoes; household and cleaning products; food and beverages; and cosmetics and personal care. The contributions from this study are important because inaccurate sustainability claims in tuna labelling risk masking unsustainable fishing practices that contribute to overfishing, bycatch, and ocean degradation—key threats to marine ecosystem health and, by extension, human nutritional security and coastal livelihoods. The findings and recommendations therefore hold direct implications for planetary health and SDGs 2 (zero hunger), 12 (responsible consumption and production), and 14 (life below water).

We organise the remainder of the paper as follows.

Section 2 reviews the inventory of studies on sustainability claims and disclosures. In

Section 3, we briefly discuss our sampling method and the rationale behind the choice of our weighting scheme.

Section 4 presents the results and a discussion of the findings. In the

Section 6, we conclude the study and document the limitations.

2. Literature Review

The term “greenwashing” originated in the last decades of the 20th century and the early 2000s [

13,

14]. Initially, greenwashing was primarily used to describe the contradictory behaviour of corporations that engaged in green marketing while simultaneously causing environmental harm [

14]. However, over the years, the concept of greenwashing has evolved, and its meaning has been widely expanded. Research presents different views on whether greenwashing is related to environmental performance and whether it damages the environment. Despite this, a widely accepted definition of greenwashing has not yet been established [

15].

One of the most recent and comprehensive literature reviews on greenwashing is by Huang et al. [

15]. According to the authors, the definition provided by Walker and Wan [

16] is the most comprehensive. This defines greenwashing as “a strategy that corporations adopt to engage in symbolic communications of environmental issues without substantially addressing them in actions ([

16] p. 3)”. In Australia, greenwashing has been defined by the courts as follows: ‘the misleading and deceptive disclosures employed by financial institutions to entice environmentally conscious investors into purchasing their financial products that, in reality, fall short of meeting the expected environmental, social, and governance (ESG) or green credentials’ [

17].

Literature contains a range of approaches to measuring greenwashing. Some studies measured greenwashing as the difference between the Green Practice Index (GPI) and Green Communication Index (GCI), naming it the Greenwashing Index [

16,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. For a detailed calculation of the Greenwashing Index, refer to Huang et al. [

15].

Others have adopted alternative methods, each with its own merits. Kim and Lyon [

27] identified the discrepancy between reported and actual emission reductions, highlighting the importance of information sources in measuring greenwashing. Marquis et al. [

28] assessed the extent to which corporations prioritise the disclosure of less significant information over more critical aspects, thus uncovering greenwashing behaviour that evades crucial issues. Darendeli et al. [

29] argue that an improvement in environmental ratings without a corresponding increase in green cost constitutes greenwashing, suggesting that their application of growth rate is more dynamic compared to other studies.

Lastly, a third group of studies used surveys and experimental research, with a primary focus on the perceptions by customers of greenwashing [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. These studies indicate that greenwashing not only occurs in information disclosure but also involves suggestive communications, such as misleading visuals or graphics, vague claims, and even the interactive design of websites [

15].

The problem of greenwashing is multidimensional and includes unfair competition, violation of consumer rights, discredit of corporate social responsibility, restriction of intellectual property, and underdevelopment of the market for environmentally friendly and organic products. [

35]. While greenwashing misleads consumers into believing they are making environmentally responsible choices, it also allows harmful practices to persist with no punishment. As a result, the potential for genuine progress in sustainability is undermined, leading to lasting impacts for ecosystems and public health [

36]. Greenwashing may undermine favourable perceptions [

37] and company profitability [

38], but more importantly, it can result in ethical harm [

33]. Recent research has specifically examined greenwashing in the food and seafood sectors, highlighting the risks of exaggerated environmental claims in industries closely tied to consumer trust. Devitt [

39] finds that while misleading sustainability claims in the Australian meat and seafood industries distort consumer behaviour, they also test the effectiveness of existing legal protections, underscoring the importance of regulatory enforcement in deterring greenwashing. This sector-specific evidence further illustrates how greenwashing erodes consumer confidence and creates gaps between industry practices and consumer expectations.

One of the potential solutions to the problem of greenwashing is increased government regulations. A study by He et al. [

40] suggests that insufficient government regulation triggers greenwashing in terms of both environmental behaviours and communication. In addition, a high government regulation capacity effectively curbs poor environmental behaviours. Liu, C. et al. [

41] and Brandon Stewart [

42] suggest that governments can effectively prevent greenwashing behaviours by increasing punishment and penalties. While Li, R. et al. [

20] provide significant evidence that penalties for environmental violations prevent firms from engaging in greenwashing. Secondly, improving information transparency can also help in discouraging greenwashing behaviours. Governments should establish strict environmental disclosure standards and regulations to ensure that companies provide truthful and accurate information when communicating the environmental attributes of their products or services [

36].

ESG factors are becoming increasingly important in corporate and investment decision-making. By incorporating ESG considerations, investors, asset managers, and companies can align their interests to build more responsible financial products and contribute to a more sustainable world [

43,

44]. ESG scores and indices are applied in a range of contexts such as disclosure, assessing firm performance, shaping investment decisions, and ensuring that companies adhere to sustainable and socially responsible practices [

45,

46]. By offering a more comprehensive assessment than traditional financial disclosures, ESG evaluations provide better guidance for investment institutions in making informed decisions [

47]. Investors increasingly rely on ESG ratings to assess risk and identify sustainable investment opportunities, influencing capital allocation decisions [

48].

While ESG scores and indices are valuable tools for promoting sustainability, challenges remain in their application. The lack of standardisation and transparency in ESG rating methodologies can lead to inconsistencies and misinterpretations, as evident from the study conducted by Dorfleitner et al. [

44]. These authors compare different approaches to rating corporate social performance using the ESG scores of three different sustainability rating providers. The results indicate that the different ratings neither coincide in distribution nor in risk. Additionally, a study by Tehrani et al. [

49] focuses specifically on the comparison between Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSIs) and S&P Global ESG scores, particularly for German companies from 2018 to 2023. The paper highlights that these two sustainability measures do not align, indicating discrepancies in the sustainability practices of companies listed on the DJSIs versus those with high ESG scores. Thus, the inconsistencies in rating methodologies and data quality can hinder the effectiveness of ESG rating, raising questions about their reliability across different contexts [

48,

50].

In contrast, this study adapts and applies the Gompers Governance Index or the G-Index developed by Gompers, Ishii, and Metrick [

7]. This is one of the most widely used and well-established ESG evaluation frameworks for ensuring systematic and unbiased assessment of sustainability claims. It quantifies corporate governance quality through a composite score derived from 24 specific provisions, primarily focusing on anti-takeover measures. The index has been applied in finance literature to reveal that firms with more democratic governance structures tend to exhibit higher valuations, establishing a positive correlation between governance quality and firm performance. The index’s construction is based on the simple idea where a firm receives a score of one for every provision that reduces shareholder rights. The Governance Index (“G”) is therefore the sum of one point for the existence (or absence) of each positive (negative) provision. The index has been extensively applied in finance research to generate important insights in that field. Examples include: (i) Cheung et al. [

8] transparency index, where firms receive a 1 if they either omit or do not comply with a specific weighting criterion, a score of 2 if they meet the minimum compliance standard, and 3 (“higher” score) if companies exceed minimum disclosure requirements and/or meet international standards; (ii) Corporate governance ratings developed by Credit Lyonnais Securities Asia (CLSA) used by Durnev and Kim [

51], Khanna et al. [

52], Klapper and Love [

53], Chen et al. [

54], Friedman et al. [

55], and Mitton [

10]. The ratings are such that each of the issues first receive a yes/no response and firms are then given a composite rating based on their scores in the areas of management discipline, transparency, independence, accountability, responsibility, fairness, and social responsibility.

This literature review therefore highlights the conceptual complexity of greenwashing, the diversity of methods used to measure it, and the sector-specific challenges that arise in the context of seafood. Building on these approaches, this study contributes by adapting the well-established Gompers Governance Index framework to assess sustainability claims against the ACCC’s regulatory principles. In doing so, it offers a systematic and transparent method for evaluating greenwashing practices in consumer markets, extending the literature on measurement while also providing an applied case study that can inform regulatory and industry responses.

3. Methods

Our sample consists of 14 major tuna brands sold in Australia. These brands were selected based on their availability across major supermarket chains (Coles, Woolworths, Aldi, IGA) and their visibility in consumer sustainability reports (e.g., Greenpeace, MSC).

Table 1 details the market share and ownership status of selected brands. The selection includes both domestic and international brands and provides a comprehensive coverage of approximately 98% of the total Australian canned tuna market, based on estimated market share data from Future Market Insights [

56] and SeafoodNews.com [

57].

The 14 brands examined are Coles, Coles Simply, Woolworths, Aldi, IGA, John West, Sirena, Safcol, Greenseas, Little Tuna, Fish4Ever, The Stock Merchant, Walker’s, and Aldi. These brands were chosen to capture a cross section of both private-label supermarket offerings and independent or international brands with significant presence in the Australian market. Products assessed were the standard canned tuna items most commonly available to consumers, ensuring consistency in comparing on-pack sustainability claims. The timeframe for data collection was late 2023 to early 2024, chosen deliberately to align with the release of the ACCC’s Greenwashing by Businesses in Australia guidelines (2023). This timing allows the study to assess how brands’ current labelling practices measure up against the most up-to-date regulatory guidance, ensuring the findings are both relevant and contemporaneous.

The primary objective of our study is to construct a greenwashing index, designed to measure the quality of on-pack disclosure practices of tuna brands in Australia. The scoring methodology evaluates on-pack sustainability claims of canned tuna products against the ACCC’s principles for making environmental claims (2023) by using a structured yes/no response system. The ACCC’s principles are particularly relevant in this context because, in addition to providing consumer protection, the principles contribute to planetary health by enforcing accountability in environmental claims, ensuring that branding aligns with practices that protect ecosystems and promote intergenerational equity.

Each principle is translated into a set of items representing questions.

Appendix A sets out the items for each Principle and provides supporting literature for this approach. In relation to each question, a “yes” (positive attribute) receives a score of 1, while a “no” (negative attribute) or lack of sufficient information results in a 0. This polarity-based approach reduces subjectivity in assessment. The scores are then combined for each principle as described below with the individual scores leading to higher or lower overall values. This approach is an adaptation of the highly regarded “Gompers Governance Index”, used for Governance evaluation in ESG metrics. One of the challenges around building sustainability disclosure indices is that there is no unique methodology. However, the approach created here adapts and applies a methodology that is already a well-established ESG evaluation framework. It provides a systematic and unbiased assessment of sustainability claims. Although other weighting schemes appear in the sustainability disclosure literature, they do not bear direct relevance to the context of tuna packaging. Examples of other weightings in the finance literature include the following: (i) Cheung et al.’s [

8] 1 to 3 scoring system, where 1 goes to firms that either omit or do not comply with a specific weighting criterion, a score of 2 to firms that have minimal compliance, and 3 to companies exceeding minimum disclosure requirements and/or meet international standard; and (ii) 10–15% weighting in [

10], where management discipline, transparency, independence, accountability, responsibility, and fairness each obtain a 15% composite weighting score, while social responsibility is weighted 10%. In both these cases, the different approaches do not apply in the current case because (i) they introduce subjectivity and (ii) they relate to management discipline, accountability, responsibility, and social responsibility.

To illustrate the implementation, consider the opposing contexts of exaggerations and truthful environmental claims. Exaggerated claims are obviously a negative attribute, and truthful claims are obviously a positive attribute. The answer to the question “Are there exaggerated environmental benefits on the packaging?” can be yes or no. A yes answer is negative and receives a 0 value. In contrast, if the given product does not exaggerate the environmental benefit, a no response is a desirable attribute, and therefore it receives a value of 1. As indicated earlier, a default value of 0 is assigned to a given item/question if there is not enough relevant information available to discern a response.

Table 2 sets out the scores for answers to individual items in line with applications encountered in ESG literature [

58] and applied by practitioners [

59] (Refinitiv, 2022).

A standard score is produced for each principle by adding the scores and dividing by the number of questions/items identified for that principle. This helps reduce any bias attributed to the number of questions/items emanating from the descriptions of the principles contained in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [

9]. This study excluded the fourth ACCC principle, “Explain any conditions or qualifications on claims”, from the scoring process because, in the specific context of canned tuna labelling, the conditions and qualifications relating to consumer actions and situations were found to be largely inapplicable. As a result, the individual scores for seven principles are added together for each brand. The range for scoring is a maximum of seven and minimum of zero; tuna brands with low greenwashing practices have higher scores. It is worth noting that two-thirds of the authors rated the on-label sustainability claims of the brands, while one-third cross-checked the raters for consistency. To mitigate bias in the scoring process, the researchers also met regularly to resolve conflicts and reach consensus on how the scoring of the on-pack claims best reflected the ACCC principles.

4. Results

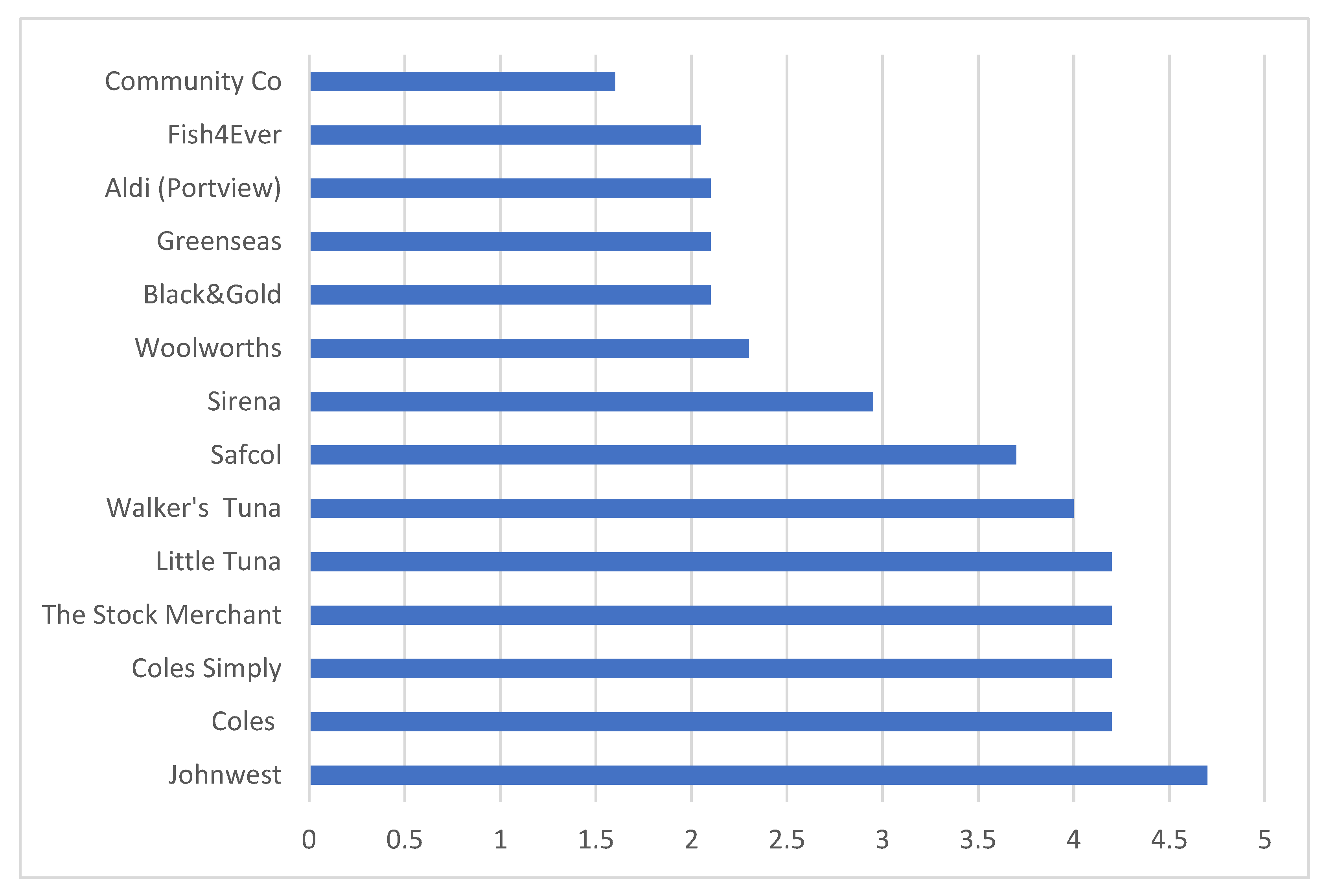

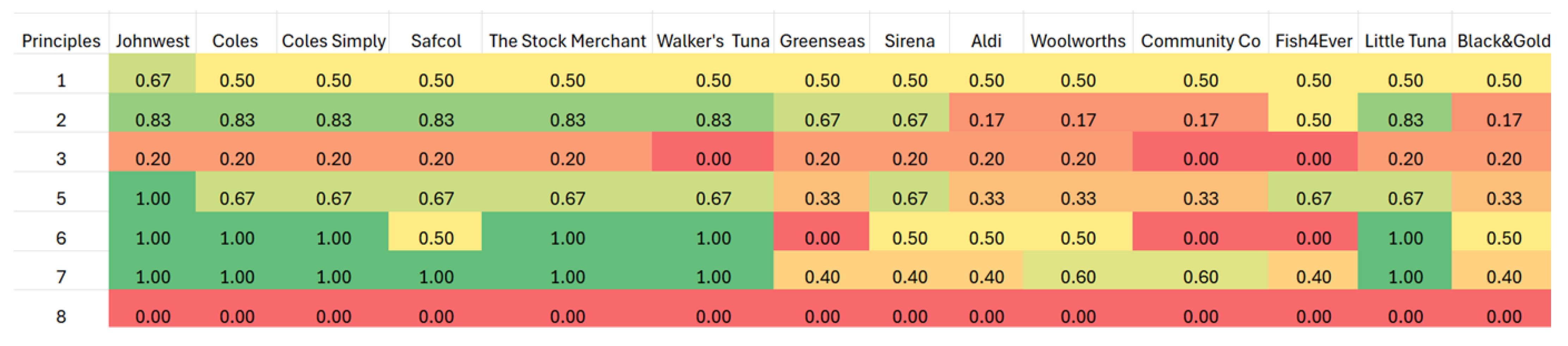

The analysis of tuna brand labels reveals significant variations in satisfying the essence of the ACCC principles. The overall performance of the brands forms two reasonably distinct groups—one at a high level of successfully reflecting the principles and a second group with notable opportunities to improve on their sustainability communication and transparency. Based on total scores, the higher-ranked cluster achieved scores between 3.7 and 4.7. John West leads the group with the highest score of 4.7. Coles, Coles Simply, The Stock Merchant, and Little Tuna each had a score of 4.2, and Walker’s Tuna and Safcol complete this highly ranked group with scores of 4 and 3.7, respectively. The second cluster has scores ranging from 1.6 to 2.95 with the bulk of this group tightly ranging between 2.1 and 2.3. There is therefore a notable gap between the top-performing brands and those that display potential to improve on how they reflect the sustainability communicating principles of the ACCC. A deeper examination of individual sustainability principles shows mixed performances leading to the total scores. Brands generally performed well in making truthful claims and providing sufficient evidence to support these claims. However, there are issues with respect to omitting information and communicating any qualifications associated with the stated claims. General communication clarity was also divided—while some brands effectively conveyed their sustainability claims, others used complex language. A high level of transparency in regard to future sustainability transitions was universally absent, as no brand outlines their future goals for improving environmental impact. The heat map visualisation highlights these discrepancies: John West, Coles, Coles Simply, The Stock Merchant, Little Tuna and Walker’s Tuna emerge as the most sustainable brands. This form of analysis also helps pinpoint the principles where the other brands can potentially build on their current scores to lift their performance.

Figure 1 depicts the individual total sustainability score for each brand. This figure clearly shows the seven leading brands creating a cluster separate from the remaining brands. John West has the highest score of 4.7, and Coles, Coles Simply, The Stock Merchant and Little Tuna achieved the same score of 4.2, while Walker’s Tuna and Safcol sit slightly lower at 4 and 3.7. Most of the remaining brands are closely ranged from Fish4Ever at 2.05 to Woolworths at 2.3, with Community Co a little lower at 1.6, and Sirena at a reasonably higher step up of 2.95.

The grouping of the brands into two distinct clusters was validated by applying the elbow method of comparing within-cluster sum of squares [

60] (Ketchen & Shook, 1996). The drop off in within-cluster sum of squares from 1 to 2 clusters is an impressive shift from 15.51 to 1.51 with little significant improvement from adding additional clusters.

Figure 2 provides a detailed breakdown of the minimum, maximum, and average scores across the ACCC principles. In the figure, the bold line inside the boxes represents the median score, and the cross represents the mean score. The boxes span from Q1 (25th percentile) to Q3 (75th percentile) for each principle’s scores. A wider box indicates high variability, and a narrow box means a tighter pattern of scoring across brands. Finally, the “whiskers” capture a more complete range of the pattern of scores—e.g., where the maximum or minimum of the scoring pattern were outside the highest and lowest quartiles. The individual dots show any outliers to the pattern of the majority of the scores. An example of an outlier is where almost all brands achieved a score of 0.5 for Principle 1, but John West was alone in scoring a higher result of 0.67 for this principle. This figure helps reveal key patterns of how the brands perform in specific areas. Overall, the data suggests that while brands tend to make claims that are likely to be accurate, they frequently lack sufficient evidence to support these claims and can omit some information. Additionally, the clarity of communication varies significantly, and there is a widespread practice across the brands of not including transparent information about future sustainability transition plans.

Regarding Principle 1 (Making accurate and truthful claims), most brands scored 0.5, with John West standing out as an exception at 0.67. This suggests that, in general, brands make sustainability claims that are likely to be factually correct. However, this principle also reveals an aspect of the aspirational standard setting which ACCC is applying, and that full success here will require brands to include robust scientific evidence for their claims (and potential to include aspects of future sustainability progress). In Principle 2 (Having evidence to back up claims), the scores widely range from 0.17 to 0.83, with most brands scoring above 0.5. This indicates that, in general, brands provide sufficient supporting evidence to ensure the credibility of the claims they make. The wide range suggests there is scope for some brands to improve in this area, particularly with respect to providing independent scientific evidence, providing data on supply chains, and obtaining third-party certification.

Principle 3 (Not hiding important information) is a particularly challenging principle to score well in. This is illustrated by most brands scoring 0.2 and a few outliers on 0. This principle seeks to ensure consumers are fully aware of the context of a brand’s sustainability actions and requires brands to provide a comprehensive overview of its environmental impact—including both positive and negative aspects. This principle therefore displays further aspirational standard setting by the ACCC and may require the industry to further invest in revealing more details on their labels (and potential additional monitoring systems to support this information). In contrast, most brands were careful in specifying the stages of their product lifecycle that their claims relate to. This means the implied extent of their sustainability practices in their messaging was clearly represented.

Regarding Principle 5 (Avoiding unqualified and broad claims), although most brands scored 0.67 and above, some of the brands stand at 0.33. This indicates that apart from a few brands (that consistently scored low across principles), most brands performed well in terms of clear and well-defined sustainability claims. Similarly, in Principle 6 (Using clear and easy-to-understand language), communication clarity was another area in which brands mostly performed well. With a few exceptions, brands were split between 0.5 and 1. While most brands effectively communicate their claims in simple language, some employ technical jargon or overly complex wording, which therefore makes these claims more difficult to interpret by consumers.

Brands showed a wider range of performance on Principle 7 (Avoiding misleading visual elements), with scores varying from 0.4 to 1. While most brands avoided the potential for deceptive visuals and explained the details of labels, symbols, trust marks and certifications, some inconsistencies remain. In contrast, Principle 8 (Being direct and open about sustainability transition) is not a common feature, with all brands scoring 0 in relation to the ACCC’s current expectations. This is the most aspirational of the principles and, not surprisingly, no brands yet provide clear information about their long-term sustainability commitments, goals and steps for future improvements. However, the absence of clear sustainability transition pathways raises concerns about the ability of tuna brands to contribute meaningfully to long-term ecological resilience—an essential component of planetary health.

Overall, the findings indicate that an impressive number of brands, including John West, Coles, Coles Simply, The Stock Merchant, Little Tuna and Walker’s Tuna, demonstrate strong alignment with the ACCC principles. Sirena is also progressing to achieving stronger alignment. The other brands have specific elements they can improve upon to achieve a better reflection of these principles. Most brands have performed well in stating and presenting their environmental claims in an accurate and supported way. However, there is further scope to improve and more fully align with the ACCC principles, including the potential to provide further information on their future sustainability plans.

Figure 3 is a heat map visualisation which provides a clear depiction of how well different tuna brands scored in relation to the individual ACCC principles. In this figure, green signifies strong alignment with the principles, yellow indicates moderate alignment, and red represents weak adherence. Moreover, the highest score (i.e., 1) is represented by the colour green, median score (i.e., 0.5) by yellow and lowest score (i.e., 0) by red. When moving from the highest score towards the median, the colour changes from dark green to light green to yellow. This means that the darker the green, the stronger the alignment of the brands with the ACCC principles. In contrast, when moving from the median score to the lowest, the colour changes from yellow to orange to red. This in turn means that the darker the red, the weaker the alignment of the brands to the principles. These colour-coded results reveal significant disparities between brands, with the leading brands identified earlier demonstrating a stronger commitment to sustainability, while others have opportunities to improve in multiple areas.

The top-performing brands, John West, Coles, Coles Simply, The Stock Merchant, Little Tuna and Walker’s Tuna, show predominantly green values across multiple principles. These results are consistent with

Figure 1, but the heat map shows greater detail on where these brands adhere to sustainability best practices: providing accurate claims, avoiding misleading statements, and ensuring transparency in their communications. Their strong alignment sets a benchmark for industry-wide practice. In contrast, other brands show frequent challenges in aligning with the ACCC principles, as reflected in their multiple red values and lower overall scores. These brands miss criteria, particularly in areas such as disclosure of information. Their results therefore suggest that there is potential to improve transparency and evidential support for their environmental claims.

A closer investigation of the specific principles highlights areas where brands can improve. Principle 8 (Transparency in sustainability transition) and Principle 3 (Disclosure of important information) both showed significant opportunity for further improvement. As yet, no brands are communicating their long-term sustainability plans, and most are avoiding disclosing details of qualifications and limitations in relation to their environmental claims. This, in turn, can affect the ability for consumers to make fully informed choices. In contrast, Principle 7 (Visual clarity) yielded distinctly mixed results, with scores ranging widely. While some brands excelled in ensuring that their sustainability messaging was visually clear and not misleading, others performed somewhat inconsistently. Despite this variation, most brands generally adhered to best practice in this area, with green values outweighing orange. It is evident that most of the brands scored highly on Principles 5 (Avoiding vague claims) and 6 (Clear language) by making well-defined claims and using straightforward, accessible language. However, some of the lower-scoring brands missed the mark through using broad and unqualified statements or more technical jargon that made their claims difficult to interpret.

The details of the heat map also reveal the relative scoring benefits correspond with brands attaining third-party certification. All the brands with predominantly green scoring are certified by external sustainability evaluating organisations (e.g., MSC, Dolphin Safe, etc.). While some specific elements of the ACCC principles relate to a brand achieving certification, other elements of the principles can also be explicitly supported by the requirements of third-party certification (e.g., verifying supply chains and providing online details to support claims, etc.). However, there is scope for the ACCC principles to recognise the thorough vetting of brands’ sustainability practices and the directions third-party certifiers provide on clear communication. The positive influence they bring is evident by the degree to which the certified brands achieve positive scores on issues not directly relating to certification. Further, where scoring was carried out on brands before and after a brand’s certification, a significant overall improvement was observed. It is also likely that third-party certification creates a solution to the problem that too much information is difficult for consumers to process (especially while shopping). The key benefit here is that certification enables consumers to be confident that the issues reflected in the ACCC principles have already been assessed and evaluated by a knowledgeable, well-resourced and independent source of assurance.

Overall, the heat map highlights a clear divide between brands that have succeeded in aligning with the ACCC principles and those that are yet to achieve significant alignment. The findings emphasise the need for improved disclosure, clearer sustainability messaging, and the potential for stronger commitments to long-term environmental goals across the industry.

5. Discussion

Greenwashing has been shown to weaken public trust, damage customer loyalty, and reduce purchase intention (see, for example, Testa et al. [

23]). Our findings show that while some tuna brands demonstrate compliance with sustainability disclosure guidelines, others continue to make vague and unverifiable environmental claims, highlighting concerns that greenwashing remains a systemic issue in food and fishery markets in Australia. Our findings give insights into the importance of independent certification, clear disclosure, and transparent governance in aligning tuna industry practices with ACCC principles on the disclosure of environmental claims. We find a reasonable level of compliance with a group of brands, including John West, Little Tuna, The Stock Merchant, Coles, Coles Simply, Walker’s Tuna and Safcol, ranking above the industry average. A possible explanation is that these brands hold relevant third-party sustainability certifications, supporting scholarly literature showing that third-party certification enhances the credibility of corporate sustainability disclosure and reduces consumer scepticism [

61,

62]. This finding also aligns with another stream of literature arguing that credible certification schemes reduce firms’ opportunities for greenwashing, highlighting compliance with the principles of consumer protection [

63].

We also document that top-ranking brands perform strongly across multiple ACCC principles, including avoiding vague claims and unclear language, showing that well-defined claims and clear communication reduce greenwashing practices. These findings align with the literature that well-defined, unambiguous claims and specific disclosures improve consumer trust and comprehension [

64]. Further, we show that there are material gaps in the disclosure of important information and the transparency of sustainability transition. Most of the tuna brands in our sample fail to disclose their long-term sustainability strategies or disclose the limitation of their environmental claims, undermining the ability for consumers to make informed choices. This aligns with studies arguing that incomplete disclosures trigger the erosion of consumer trust [

28].

The empirical results of this study offer material contributions to the inventory of academic studies on the development of sustainability indices and the implications of greenwashing on consumer trust and planetary health efforts (see, for example, Gompers et al. [

7], Mitton [

10], Gjølberg [

11], Cheung et al. [

8], Le Folcalvez et al. [

12]). Our study expands the current literature by using brands’ labelling sustainability claims to construct a greenwashing index for the tuna fishing industry. By concentrating on labelling claims that influence customers spendings, our methodology differs from the previous studies measuring sustainability claims in corporate reports and websites using the IRRC and the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance (see Gompers [

7], Cheung et al. [

8]). Our study develops relevant items that can be adapted to assess the extent of greenwashing in other industries; researchers and policymakers could apply this principle-based scoring methodology to identify inaccurate sustainability claims. This approach has direct implications for planetary health, and supports progress toward Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDG12 on responsible consumption and production.

While our analysis is grounded in the ACCC framework, the relevance of developing greenwashing indices and evaluating brand performance extends beyond the Australian market. The ACCC’s principles are closely aligned with international initiatives such as the UK Competition and Markets Authority’s Green Claims Code, the EU’s proposed Green Claims Directive, and the U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s Green Guides, which collectively signal a global regulatory consensus on the need for accurate, transparent, and verifiable sustainability claims. As such, our findings not only provide insights into greenwashing practices in the Australian tuna industry but also offer a transferable case study that can inform comparative research and policy design across jurisdictions.

Our findings have material policy implications. First, the absence of Principle 8—transparent transition strategies—across the various brands suggests the need to sufficiently enforce the current regulatory expectations. The ACCC should strengthen their framework by requiring the various tuna brands in Australia to disclose future sustainability goals, such as brands having clearly communicated specific goals for improving environmental sustainability. Second, policymakers should engage in frequent random label audits, with penalties for vague claims, and compulsory disclosure of evidence sources, mitigating under-disclosure, ensuring the clarity of claims, and aligning with the principles of consumer protection. Third, our study highlights the positive implication of third-party certification, underscoring the need for the ACCC and other relevant regulators to explicitly compel various tuna brands to have third-party certifications. This would reward compliant tuna brands and also reduce consumer information overload, as trusted certification would act as a shorthand for regulatory compliance.

6. Conclusions

Based on the ACCC’s principles for trustworthy environmental claims, our paper creates an index to access the environmental claims made by tuna brands in Australia. We create a scoring scheme that breaks down seven (of the original eight) principles into 30 items. The findings reveal that canned tuna brands can be categorised into two distinct clusters: one exhibiting a notably high level of achievement and the other characterised by significant potential for improvement in sustainability communication and transparency. Furthermore, the analysis identifies critical trends, notably a pervasive inadequacy in disclosing future sustainability transition strategies across the majority of brands. A thorough examination of the scoring framework indicates that brands with third-party sustainability certifications generally demonstrate a greater alignment with ACCC principles than their non-certified counterparts.

The ACCC’s framework is an important step toward reducing greenwashing. However, it has limitations. First, the lack of mandatory sustainability labelling regulations means businesses can still make vague claims without facing immediate penalties unless consumers or competitors challenge them. Additionally, the ACCC’s reliance on consumer complaints and investigations may not proactively prevent misleading claims from reaching the market.

The one-size-fits-all approach to different industries is also a challenge as it may not fully capture the nuances of environmental claims in complex supply chains (e.g., seafood). Clear labelling is important, but some sustainability claims rely on complex fishery management practices that most consumers may not understand. This issue extends to the evolving capacity for consumers to follow up by accessing and evaluating information available on the internet (i.e., beyond what is on the packaging). This dimension is beyond the scope of the current research but may motivate and extend future studies. There are also related limitations around how the principles are scored, e.g., the limit to widely known certifications, and consumer’s awareness of technical terms, etc. The focus of the current study is necessarily limited to what the consumer sees on the grocery store shelf (i.e., in the brand packaging) and to the technical knowledge accessible by a preliminary internet search. However, these dimensions may evolve and be extended in future studies. Future analyses should consider an ongoing collection of relevant data concerning the tuna industry to unravel the implications of this greenwashing index on market valuation, consumer purchasing behaviour, and the financial performance of tuna brands. Future research could also explore longitudinal changes post third-party certification.

Our paper leads to three major policy implications. Firstly, there is potential to achieve comprehensive alignment with the ACCC principles through increased enforcement measures. Greater enforcement and increased penalties (e.g., for repeated or severe violations) will ensure businesses take their responsibilities seriously, potentially requiring an overall revision of the principles and their interpretation. Secondly, our results provide useful insights for tuna brands to design and communicate environmental claims that follow the ACCC’s framework. This helps companies to comply with government mandates designed to curtail greenwashing and ensures the accurate representation of sustainability claims to consumers. Thirdly, and most significantly, addressing greenwashing in marine food systems extends beyond consumer rights—it is central to planetary health governance. Effective responses should integrate food system resilience, marine biodiversity protection, and equitable access to sustainable seafood into both regulatory frameworks and corporate accountability mechanisms.