2. Climate Anxiety and Nature Connectedness: Complementary Approaches to Address Climate Change

Environmental conservation and the mitigation of the effects of climate change are associated with the rights of children and youth. Inadequate and insufficient measures to confront the climate crisis can be considered one of the major threats to the current young generation and will compromise the fundamental right to health and well-being of children [

18]. Recognizing the gravity of the problem, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child published the General Comment n.26 (2023) for the signatory countries about the rights of the child in relation to the environment, with a special emphasis on climate change. The document recognizes that environmental degradation, especially the climate crisis, jeopardizes the exercising of the rights proclaimed in the Convention on the Rights of the Child and reinforces the obligations of states to prevent and repair the damages caused by that degradation. As holders of rights, children should be protected against these violations and be fully recognized and respected as environmental actors.

A deep understanding of climate change-related phenomena and their intertwined effects are facilitated (and enhanced) by multidisciplinary fields of knowledge and practice. Its outcomes impact different aspects of lived experiences, affecting humans and others on multiple scales, varying according to cultural, social, economic, and geographical specificities.

In this article, the authors discuss young people’s perspectives on health-related issues, and how they impact their emotional responses to climate change, focusing on two rationales derived from recent developments. The first will focus on definitions of climate anxiety, while the second will explore definitions of nature connectedness as a tool to envision viable practices to establish reciprocal relations with the natural world. The article is also aligned with the guiding principles of decolonial studies [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], emblematic of the emergence of knowledge to rethink modes of resistance to Eurocentric theories and concepts [

25]. Decolonial theories play an important role in questioning/re-evaluating conventional narratives and the legacies of colonialism that still exist today despite the end of colonial rule. Decolonial practices have exposed the silencing and claims of groups that have been/are historically marginalized.

Climate change presents multiple consequences for children’s and youth’s lives, including their mental and physical health. The terminology of climate anxiety (or eco-anxiety) has been widely applied in attempts to focus the debate on the levels of distress caused by the environmental crisis. The term does not refer to a clinical condition and can be linked to a multiplicity of emotions, such as anger, stress, guilt, or despair, among others. However, it does not necessarily exclude positive feelings, such as hope and desire to promote change. Climate anxiety is defined as an overarching term for psychological symptoms associated with climate change [

26,

27].

According to Hickman et al. [

28], these mixed emotions are especially challenging because they occur during the child and youth developmental stages and may cause psychological, neurological, physical, and social effects, and/or exacerbate pre-existing mental conditions. Climate anxiety also adds to the vulnerability of younger generations, and even more so if we cross-reference with data regarding social and economic factors.

Analogous to the definition of climate change, the term nature-deficit disorder, i.e., a weakened ecological literacy, is a non-clinical terminology that addresses a pressing matter concerning the reduced (and declining) amount of time human beings spend in natural settings [

29]. The term was first applied by Richard Louv [

30] in the book ‘

Last Child in the Woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder’. According to the author, exposure to natural environments can promote a sense of place, lessen different types of stress, assist cognitive development, and represent sources of well-being to reduce the hazardous effects of urban lifestyles, such as prolonged screen time and diminished in-person socialization and time dedicated to physical activities. However, this terminology refers to one of the possibilities among others found in the literature that can also be applied to highlight the relevance of connection to green spaces, such as wild, rewild, wild at heart, green prescribing, environmental knowledge, and environmental attitude.

The terminology of nature-connectedness in this article addresses the theme of the disconnection of young people from nature, and the costs of alienating ourselves from nature [

30]. The effects and symptoms that reveal the increasing disconnection to natural environments have short-, medium-, and long-term consequences. Among them are the generational reproduction of disconnection due to the absence of memories and feelings of affection related to experiences in nature. When we consider the correlation between affective memories and environmental preservation actions and/or initiatives, both individual and collective, the relevance of this theme is accentuated.

Research on (dis)connection with nature spaces and climate anxiety offers an approach that is still little explored, especially concerning children and young people, permitting multiple ways of rethinking everyday strategies to address these challenges and foster new paradigms of interaction with the natural world.

The daily practices experienced in natural spaces, especially in the first years of life, may lead to future positive actions, both for the creation of affective memories and for stimulating engagement in actions aimed at environmental preservation. The greater the proximity to nature and access to green spaces, the more beneficial the relationship with improved quality of life [

31,

32,

33].

As highlighted by Tiriba [

34], there is a disconnection between social and ecological systems that can be addressed through the formulation of new ways of thinking, acting, and feeling. Awareness-raising processes are essential for the design of alternative models, structured through relationships of empathy and reciprocity with the natural world [

35]. Reciprocity encompasses an increased awareness of human responsibility for ecological preservation and the recognition of the interconnection between all life forms. At an institutionalized level, the concept of Nature’s Contribution to People (NCP) was introduced in 2017 as part of the Brazilian Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) to link policy, practice, and scientific discourse. NCP incorporates other worldviews on human–nature relations, such as indigenous knowledge, which is also an intrinsic principle of decolonial studies, questioning the reductionist and instrumental perception of nature as a source of economic benefits. The convergence between popular culture, scientific study, and practitioner engagement can lead to significant changes in childhood nature experiences [

36].

The approach based on the reciprocity of human–nature relations raise relevant questions in line with decolonial studies, which highlight ontological knowledge and traditional narratives that portray experiences based on a reciprocal relationship with the natural world, which have been overshadowed by colonization. The concept of reciprocity also entails three dimensions defined by Singh [

37] as affective ecologies, (1) thinking about the liveliness and interconnectedness of the world; (2) rethinking our conceptions of the human and human nature; and (3) reconceptualizing ecopolitics.

Societies in general, and more specifically, urban environments, are faced with pressing challenges regarding the consequences of more (or fewer) opportunities to interact in natural spaces [

38,

39]. There is an acute demand to expand and deepen studies in this field specifically aimed at children and youth populations. Among the many challenges, the following are highlighted: (a) the impact generated by unequal access to green areas due to socio-economic, racial, gender, and intergenerational differences; (b) everyday experiences characterized by a lack of access to nature settings considering that disconnection tends to reproduce behavioral patterns experienced in childhood/youth [

40]; (c) the lack of affective memories interfering with interrelationships between peers, and with other forms of life, including plants and animals [

41] and, (d) the effects on mental and physical health [

42,

43].

3. Material and Methods

This study was based on a purposive sample aimed at fairly representing youth by age, sex, skin color, geography, and economic class. It included 200 young people between the ages of 12 and 18. Socio-economic diversity was achieved by choosing students from both public and private schools. In Brazil, students who go to private schools come from predominantly middle- and upper-class homes, and those that attend public schools are from lower-income households.

Subsamples were taken from major cities in Brazil, where CIESPI/PUC-Rio had previous contacts with nonprofit organizations and other institutions or universities. The selected cities represent the five regions of Brazil: Brasília and Goiânia (Center-West); São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (South East); Fortaleza and Salvador (North East); Curitiba and Porto Alegre (South); and Manaus and Belém (North). The last two cities are Amazonian cities where various programs are taking place to preserve the tropical rain forest and where the next meeting of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 30) will be held in November 2025, in the city of Belém.

We contacted ten interviewers in each location who were postgraduate students or qualified professionals to conduct twenty interviews in each respective city. Interviewers were instructed to seek out students living in different localities within the city to maximize geographic coverage. Each interviewer received an orientation and training manual about the project that included strategies for approaching participants and conducting the interviews. The interviews were taped and later transcribed by a specialist firm. The individual approach to students was dictated by the fact that accessing individual boards of education to obtain permission to interview students in schools is a fairly difficult task, and that there was a shortage of time, since schools would be out for the summer holidays at the beginning of December. In some instances, interviewers looked for students accompanied by parents at the exits of schools. In other cases, where interviewers had contacts with schools, they found their samples through the schools. The interviewers were also instructed to ask respondents to suggest other young people. There are elements of both random and non-random selection in these processes.

Most of the interviews were conducted in the period between September and December 2024. The sample process can be summarized as follows: (1) the respondents were not chosen through an online invitation to talk about climate change, a common method among other studies and one that would bend a sample in the direction of those with a previous interest in the topic; (2) the purposive sample sought to and succeeded in producing a balance by age, sex, color/ethnicity, socio-economic status, and national geographical region (within each city, geographical balance was not possible); (3) the interviewers received detailed instructions about how to put the sample together and how to conduct and record the interviews; and (4) the responses were taped and then transcribed, allowing the interviewers to concentrate on the interview itself.

The project, and all complementary documentation such as the forms for Free and Informed Consent and Free and Informed Assent are in accordance with the principles and values of the Reference Framework, Statute, and Regulations of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) concerning the responsibilities of its teaching and student body. The Research Ethics Chamber at PUC-Rio approved all stages of the project under the process number SGOC519239, approved on 27 August 2024.

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

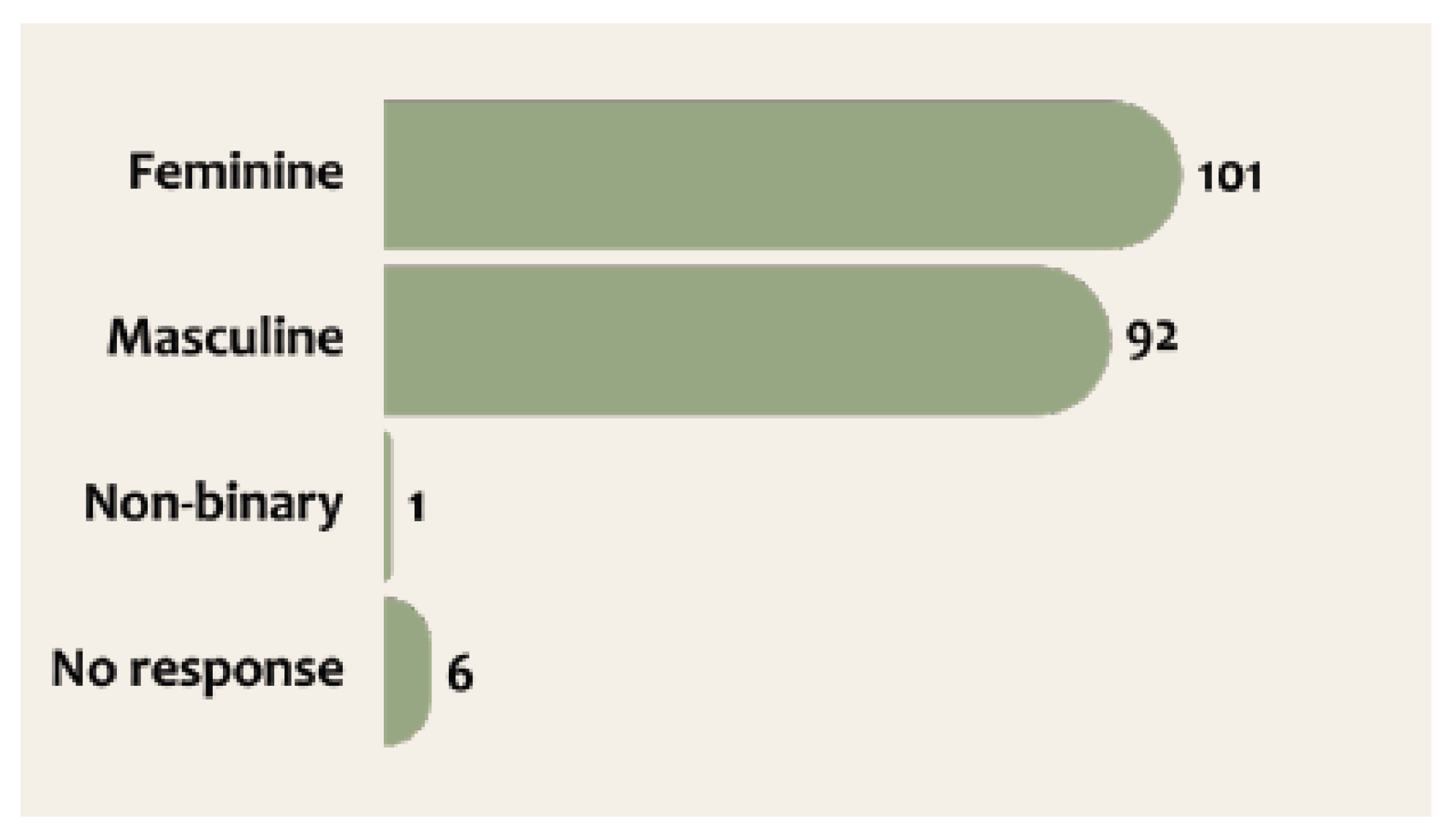

3.1.1. Participants by Gender

The sample sought to include an equal number of young men and young women, although the information on sex and ethnicity was self-declared. The sample was composed of 50.5% female, 46% male, 0.5% non-binary, and 3% who did not answer the question (

Figure 1).

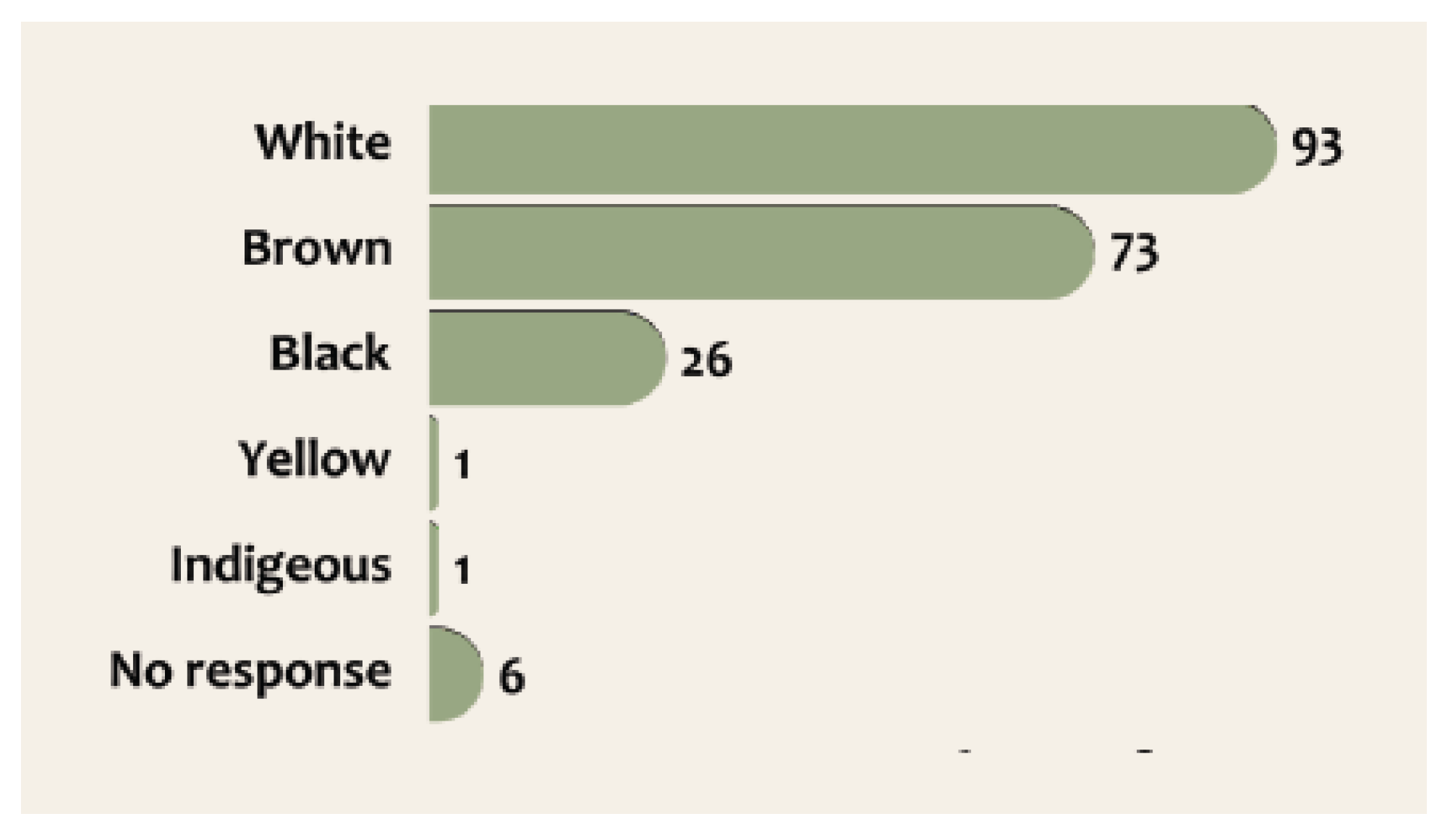

3.1.2. Participants by Race/Skin Color

Skin color and race were determined from the self-declaration of the respondents. In Brazil, ethnicity in the national census is self-determined by skin color (IBGE—Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). In our study, 46.5% of the participants self-declared as White participants, 36.5% Mixed Race, 13% Black, 0.5% Asian, 0.5% Indigenous, and 3% of participants did not answer the question (

Figure 2).

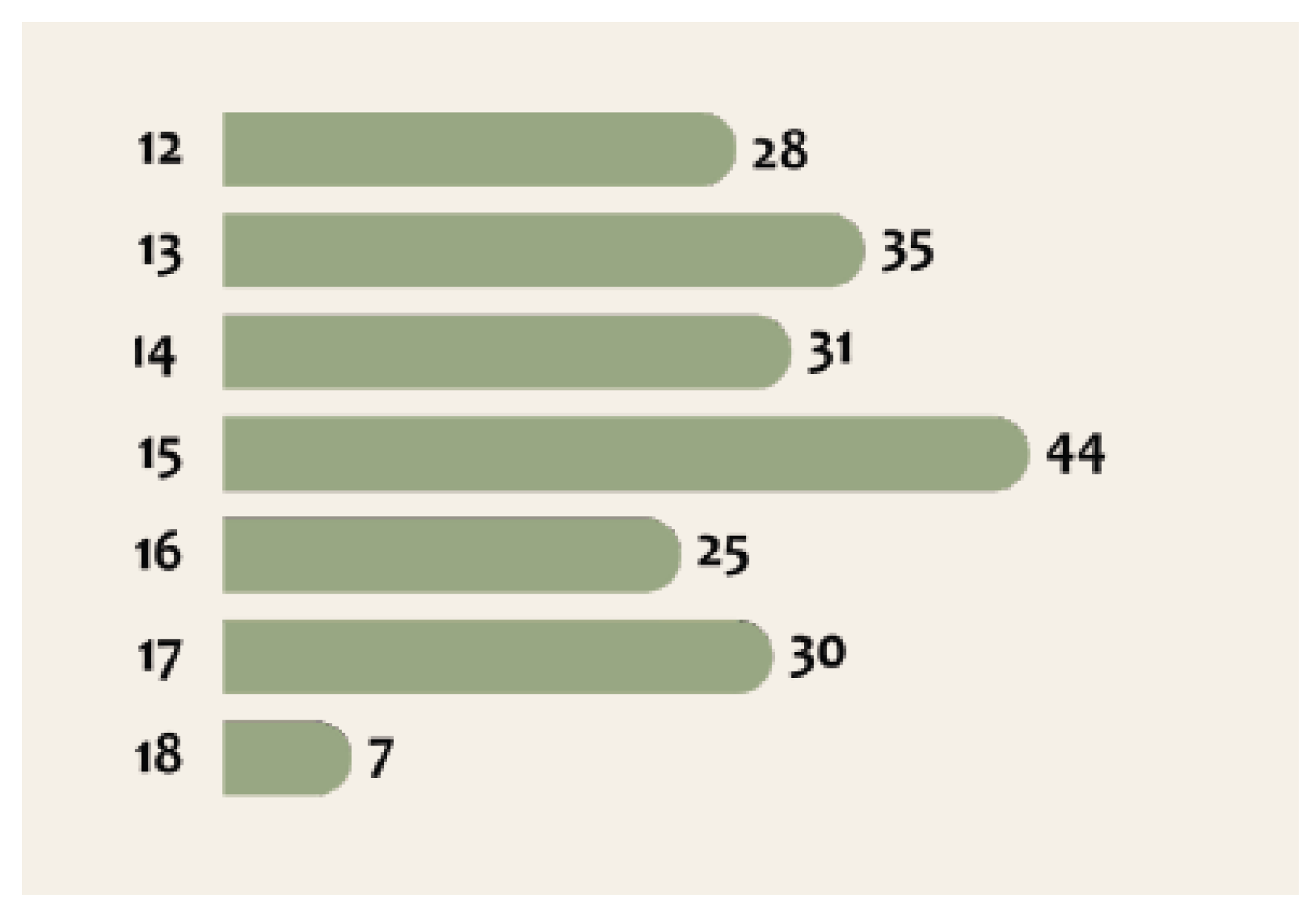

3.1.3. Participants by Age

In terms of age, the interviewees were distributed as shown in the following graph. We noticed a greater concentration in the age group between 13 and 15 years old. They account for 55% of the total sample, while those aged 18 are a minority, at 3.5% (

Figure 3).

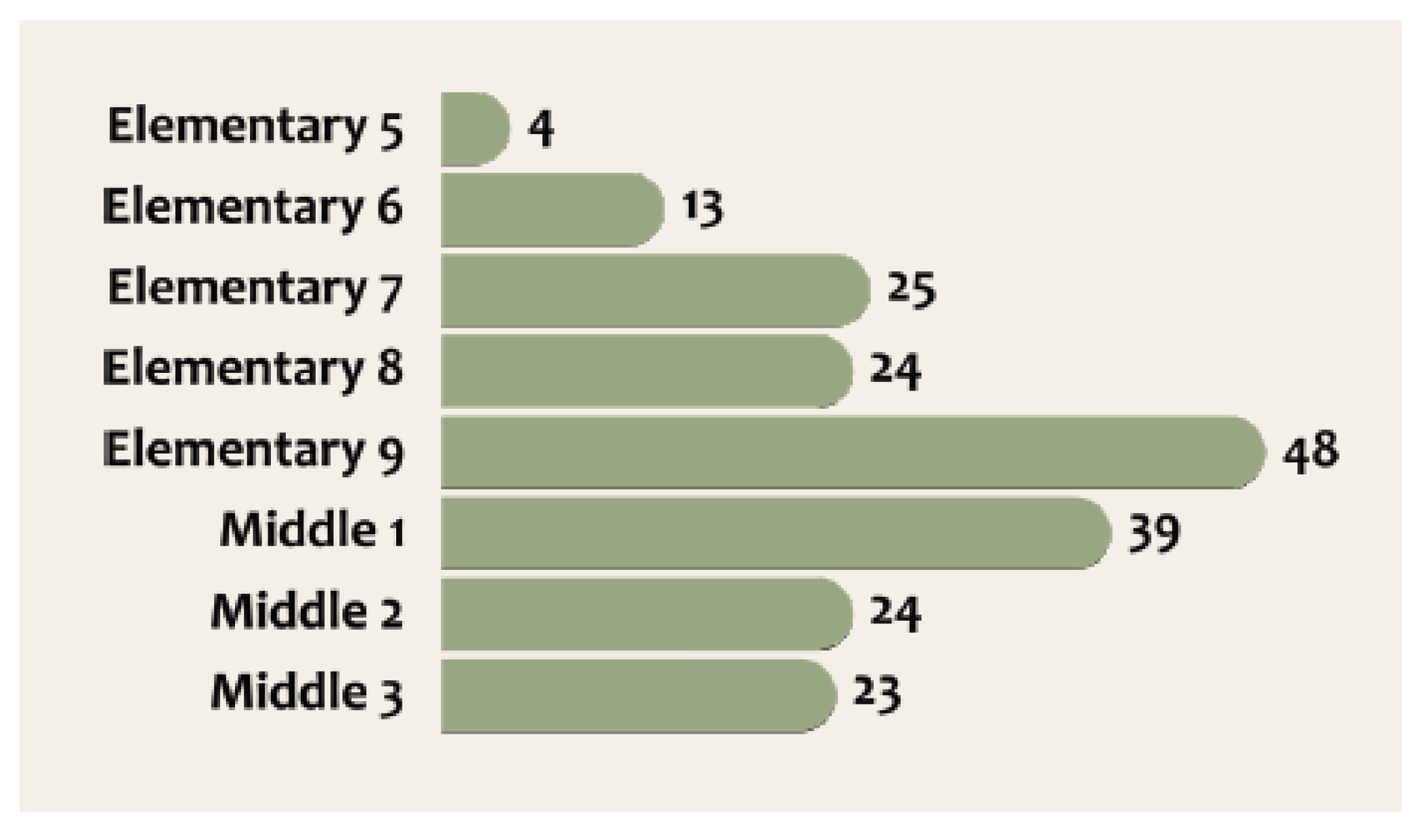

3.1.4. Participants by Educational System

The sample included 51.5% of students enrolled in private schools, and 48.5% enrolled in the public education system.

3.1.5. Participants by School Grade

The majority of respondents were in their final year of elementary school (24%) and first year of high school (19%) (

Figure 4). Although the objective was to have an age and sex equilibrium, due to challenges of arranging in-person interviews and the need for authorization by parents (especially for the younger participants), it was not always possible to guarantee this balance.

Based on the data, the sample ensured diversity in the profiles of the participants. However, although the distribution by color or race reflects the percentages of identification of the Brazilian population in the last IBGE Census (2022), we believe that our analysis could have been enriched with the inclusion of a greater number of Indigenous students, given that Indigenous peoples have historically played a fundamental role in defending the environment and resisting climate change.

3.2. Results

The complete questionnaire included 10 questions, including open-ended and closed questions. In questions 4, 5, and 10, respondents could choose one or more options.

Have you heard about climate change?

Did you learn anything about climate change at school?

‘Climate change worries me’. How do you relate to this statement?

Strongly disagree; Agree; I do not agree nor disagree; Agree; Strongly agree.

- 4.

Climate change causes:

Anxiety; fear; insecurity; other feelings: which_____; does not cause me any negative feelings.

- 5.

How does climate change affect your community?

Heavy rains; landslides; high temperatures; drought; forest fires; other? _____; no impact.

- 6.

Do you think some young people are more affected by climate change than others?

Yes (). No (). If yes, how and in which ways?

- 7.

Can anything be done to reduce the impacts of climate change?

Yes (). No (). If yes, could you give me examples?

- 8.

Do you do anything in your daily life to preserve the environment?

Yes (). No (). If yes, could you give me examples?

- 9.

Do you participate in any group, organization or social movement that works on the problem?

Yes (). No (). If yes, could you give me examples?

- 10.

Where do you get informed about climate change?

Websites; WhatsApp; TikTok; Instagram; YouTube; Twitter/X; television; school; other? _______.

Considering the primary intent of this article, i.e., to discuss young people’s perspectives on climate change and the role of (re)connection with natural spaces to promote increased health and well-being indicators for children and adolescents—such as immunity, learning ability, sociability, and physical capacity, we concentrate on the results from questions 3, 4, and 6.

All responses were tabulated in Excel spreadsheets and the results were tallied.

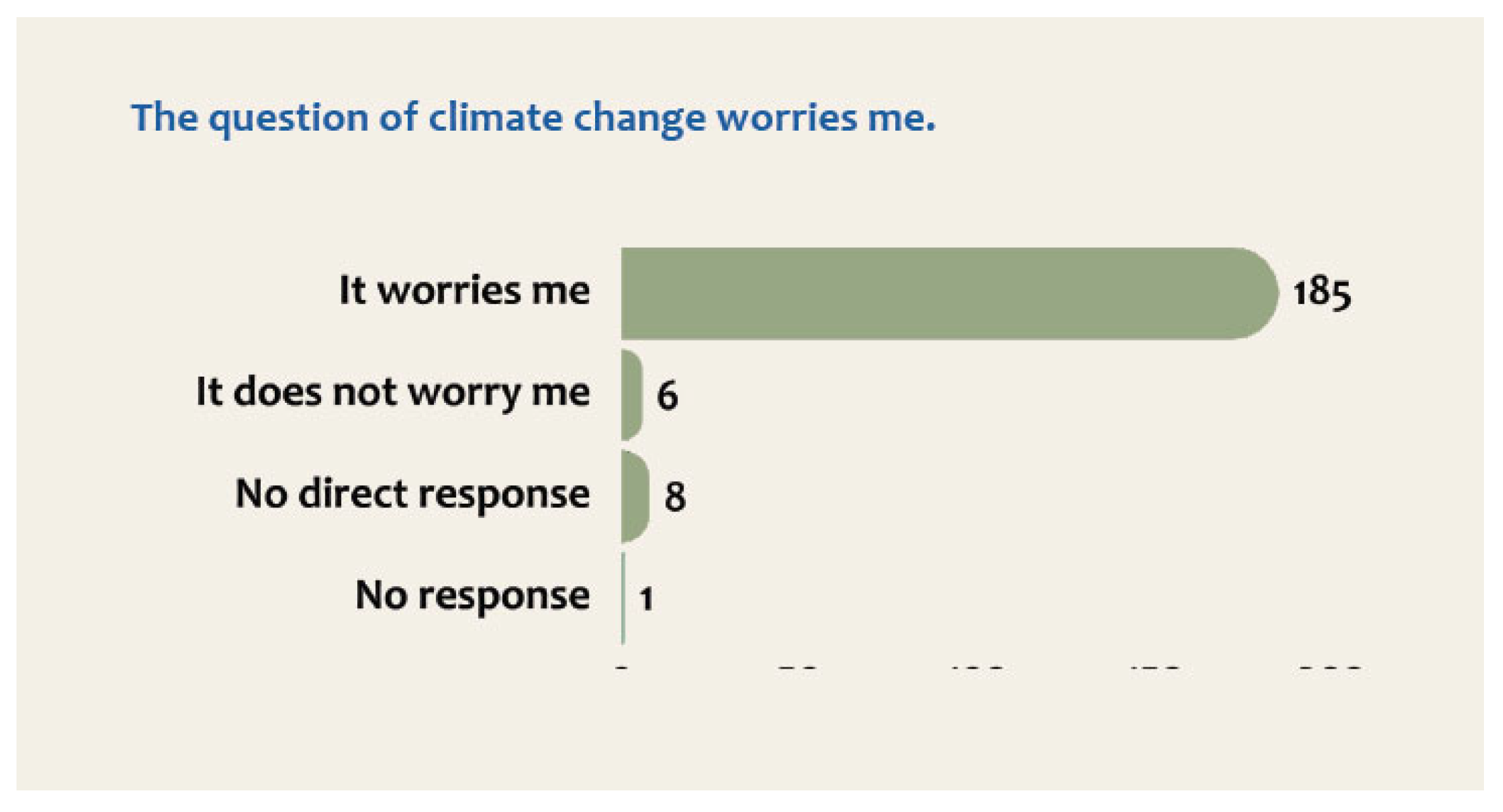

3.2.1. ‘Climate Change Worries Me’. How Do You Relate to This Statement?

More than 90% said they were worried, and only 3% said they were not worried (

Figure 5). A large number, 59, were focused on the future. They were worried about the next generation: “I am worried about the people here in this world in the future when I won’t be here... but there will be other people and I want to leave a good place for them to be”. Eleven students cited the end of the planet or the extinction of life on earth: “Because in the long run I think the world will cease to exist”. Thirty-nine respondents mentioned specific impacts that concerned them, such as the various impacts on ecosystems. There were preoccupations with the air: “I worry, I worry because of changes in the air which we need to breathe. And the oxygen comes from plants and fires make the plants die. And the smoke affects people. It can impact animals’ homes”. Worries about global temperatures were mentioned by 26 respondents, while 30 young people mentioned problems with health: “Because there are people with asthma and many respiratory diseases which can make them sick and send them to the hospital”.

Respondents noted the relationship between global warming and environmental disasters: “So, the principal climatic change is global warming. I worry that the ozone layer is getting smaller, and there is an increase in droughts, and that will kill what little of the forests remains”. A small number of respondents gave more detailed responses, and that small number suggest the need for deepening the debate; only two respondents mentioned inaction by government agencies.

While the majority of respondents recognized that some people were more affected by climate change than others, four respondents were eloquent on the topic: “Because it can invade the territory of indigenous people and end up killing half the population”, “Sometimes I worry about people living on the streets”, “Because it will worsen the lives of those in the poorest communities where life is not good”, “What worries me is that those most harmed are those who are in need or do not have any income. Like people who live on their agricultural plots, which are not particularly good places to live, and then when the rains come, everything gets flooded”.

3.2.2. Feelings About Climate Change

Question number 4 (

Figure 6) asked interviewees whether climate change caused feelings such as anxiety, fear, or insecurity. Respondents could also indicate other feelings and/or sensations freely. They could check more than one option, mention any other feeling, or indicate that they did not feel any negative effects. Most interviewees mentioned feelings of anxiety, fear, or insecurity in their answers (68.5%). In addition, another 11.5% mentioned feeling worry, anguish, sadness, anger, and revolt. Among the respondents, 17.5% said they did not have any negative feelings regarding climate change.

The question of how they felt about climate change included five different options (respondents could check more than one): Anxiety; fear; insecurity; other feelings; and the last option included the alternative that climate change did not cause any negative feelings. One of the choices was open-ended, where respondents could include their own response.

In total, 80% of the young people said that they felt anxiety, insecurity, fear, or other negative feelings due to the impact of climate change on their lives, their communities, and beyond, and most participants referred to the future: “It causes fear, as I said, it causes fear for the future of what might come”, but some highlighted current events when talking about how they felt: “Because when the fires happened, I couldn’t breathe, so I was very scared, right? I saw my family getting sick, my brothers are becoming ill, so it is a feeling of fear, right? Especially because at that time the hospitals were full here in Brasília. You see, it got complicated…”.

Insecurity was also associated with feelings about the future: “It makes me feel a certain insecurity, because I don’t know if tomorrow will be here, or if it will be something totally catastrophic”, or “It makes me feel insecure because I know that many people have already died because of this. So, I can be quite worried about whether this could happen to me one day.” One respondent expressed concern about society’s lack of awareness of the issue. “Yes and no, because while there is a way for us to still be able to reverse it, even though it is already late, what makes me feel most insecure is seeing that most people don’t care about it. What makes me most curious is to see where it will lead”.

For those who expressed no concern, the reasons varied from distancing themselves from the problem, “it will occur in the faraway future”, to that the problem was a shared responsibility.

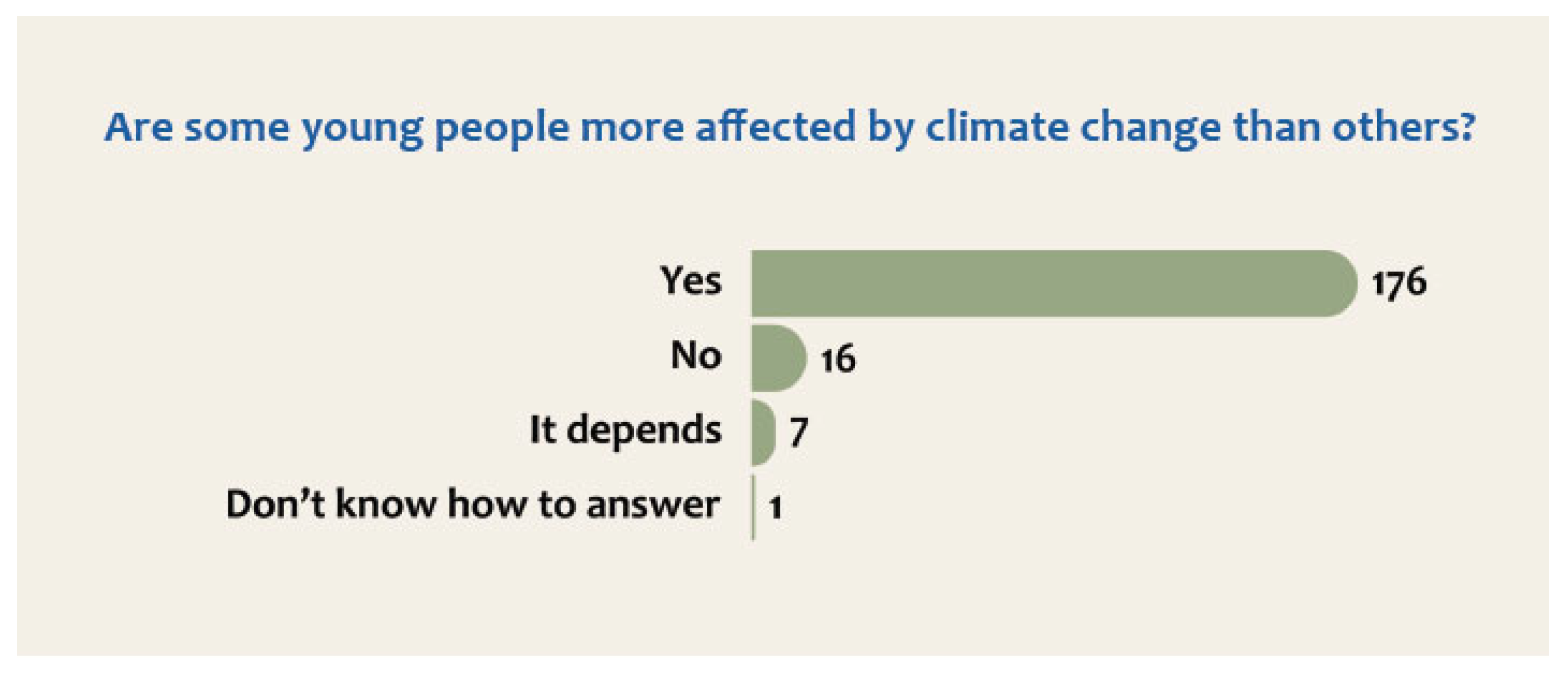

3.2.3. Social Dimension of Climate Change

Figure 7 illustrates a perception among 88% of the respondents that the consequences of climate change affect populations differently, especially young people living in poorer areas/communities. Sixty-seven young people said that the poor were most affected, while fifty-seven indicated that the home’s location was critical, and another fifty-seven mentioned that those with health problems were most impacted. “I think that for young people who have the most resources, who live in a better place, a better context, they are not so affected, but the people like me who live in communities on the periphery, they see these realities very close, they see the lack of basic sanitation, the neglect”.

In general, respondents did not mention age as a factor, except for the five who pointed out the difficulties of studying when experiencing heavy rains, high temperatures, or fires. Other relevant social issues that were highlighted by participants were the inattention of the public sector to favelas and communities located on the periphery of cities, while seven respondents mentioned health issues: “The folk who have more anxiety, these things cause fear. And it depends on individual reactions. Because there are folk who worry more about this and others who at times do not know what is happening”. Or as another respondent put it: “Indeed, everyone is affected. But some ignore the fact, they are in a bubble of ignorance”.

4. Discussion

UNICEF’s Children’s Climate Risk Index [

44] highlights the impact of climate change on the lives of the youngest populations. Approximately 1 billion children and adolescents, or almost half of the world’s 2.2 billion girls and boys, live in one of the 33 countries classified as “extremely high risk”. The report also reveals a disconnect between where greenhouse gas emissions are generated and where children and adolescents are experiencing the most significant climate impacts. The 33 “extremely high risk” countries collectively emit only 9% of global CO

2 emissions. In contrast, the ten countries with the highest emissions collectively account for almost 70% of global emissions. Only one of these countries is classified as “extremely high risk” in the index.

In Brazil, multidimensional poverty in childhood and adolescence affects 63.1% of the population up to 17 years of age [

45], that is, 32 million children and adolescents, out of a total of 50.8 million. This scenario has been aggravated by the COVID pandemic. The study also points out that multidimensional poverty has a greater impact on those who are already living in situations of greater vulnerability, such as women residents of the northern and northeastern regions, and Black and Indigenous populations, which according to data from the National Census [

46], totals 1,693,535 (that is, 0.83% of the country’s population), with more than half (53.97%) living in urban areas. These factors, combined with socio-economic challenges, impact quality of life, which can lead to malnutrition, increased disease, and negative effects on mental health [

47,

48].

The responses to question 6 of the questionnaire ‘Do you think some young people are more affected by climate change than others?’ indicate that children and adolescents are aware of the socio-economic dimension of the climate crisis. Another aspect linked to socio-economic factors is access to reliable information. The study has shown that among the 200 interviewees, 199 stated that they had heard about climate change, and for 92.5%, it aroused feelings of concern or great concern. The examples range from increases in temperature, heavy rains, forest and urban fires, and deforestation. Health conditions in general, and particularly young people’s health, were also highlighted by 90% of interviewees as a source of concern, and as a direct consequence of climate change in everyday lived experiences due to socio-economic disparities and places of residence. It is important to mention that, among those who said they did not feel any negative effects, three justified their answers by indicating that the impacts of climate change were still far away.

Studies suggest that, when recognizing the global dimension of the problem, many people see their individual actions as insufficient to generate a significant impact, which can result in inaction, especially when there is a lack of effective structures to facilitate engagement. This effect is reinforced by the perception of temporal and spatial distance, that is, the more a problem is seen as remote and affecting other populations, or occurring only in the future, the less likely it is to generate immediate mobilization [

49].

In addition to the research data, the literature on the subject indicates that one of the ways to reduce the impacts of climate change among children and young people is precisely through participation and action [

50,

51]. It is important to highlight that several of the young people expressed their interest and willingness to do more—they just did not know how. Access to knowledge and information that takes into consideration young people’s perspectives is an important part of the framework of children’s rights. In a study conducted in Brazil and Mexico by the Center for Defense of Childhood-Grupo Marista (2022) with 457 young people between the ages of 10 and 18, 90% of the Brazilian respondents said that they had heard about the rights of children, such as the right to education, health, and participation in decisions about their lives. The study also showed that 60% of the participants were worried about the consequences of the climate crisis, and that 79% believed that its effects could jeopardize future generations. However, 64% of the respondents said that they did not think their views were respected or taken into consideration.

The study Childhood (UNICEF-Gallup, 2023) [

45], carried out with young people between the ages of 15 and 24 in 55 countries including Brazil, investigated both the understanding young people had about climate change and their main sources of information on the topic. A total of 56%of the Brazilians interviewed correctly defined climate change, and 71% said that social networks were their principal sources of information. While platforms such as Instagram and Tik Tok were mentioned, there is no public data about young people’s ranking of sites or about the content of the information accessed. These results indicate a need to reach out to younger generations more intensely, and by using different approaches and methodologies.

However, our study showed different results, which indicated schools as the primary source of information, followed by television, and thirdly, social networks. Schools and teachers were mentioned prominently in 61% of the responses, as was television, in 51%. Among social networks, Instagram (40%) and TikTok (37.5%) stood out. It was surprising that for participants, television was so prominent in the responses. One of the factors that might explain this result could be limited access to the Internet, particularly for low-income students. If we consider that almost 90% of the participants mentioned that there were alternatives and actions that might diminish the negative impacts of climate change, access to reliable information is of utmost relevance, particularly if we bear in mind that 72% said that they put into practice daily activities toward environmental preservation [

52].

While these young people try to contribute through small-scale individual actions, such as the proper treatment and disposal of waste, saving electricity and water, and caring for plants, the vast majority do not engage in any collective action. Only six participants said that they were involved in any kind of collective initiative, organization, and/or social movement related to environmental issues, including school projects. We would like to emphasize this enormous potential for engagement in initiatives that allow them to expand their knowledge about environmental issues and their connection with nature, since the establishment of positive relations with and memories of nature arouse participation in activities to preserve the environment throughout their life.

Nonetheless, in urban Brazil, it is a challenging task. A total of 80% of Brazilian children live in urban centers and have limited access to green areas. Recent data [

53] on access to green spaces indicated that 20,635 public and private elementary schools located in capital cities are within 500 m of favelas and urban communities, highlighting the connection between inequalities and climate factors. The differences in terms of skin color are also striking; the majority of students in these schools (51%) are Black, a percentage that drops to just 4.7% in schools with students who declare themselves as White. The study also demonstrated that 4 out of 10 schools do not have green areas (37.4%).

Among the contributions of this study, we highlight firstly the age range of the target audience, that is, children and adolescents under 18 years old whose points of view about the climate crises remain understudied. Listening to and the active participation of children and young people are essential components for (re)thinking alternative models for environmental preservation. As Arola et al. [

54] point out, proximity to natural environments is linked to how younger generations perceive their relationship with nature, hence the role of this relationship in improving their quality of life. Other studies emphasize different aspects, such as that action and participation help to reduce the symptoms of stress, anxiety, and fear related to climate change [

55], and can contribute to improving quality of life [

56].

We also stress the connection between the climate crisis and the importance of (re)connection with nature as part of a set of practices and ideas that promote actions of participation and the engagement of children and young people to preserve the environment. According to Richardson et al. [

57] “Bringing about a new relationship with nature needs interventions and approaches that affect large changes at scale across complex systems” [p.387]. For this purpose, the production of situated knowledge plays a central role in addressing large-scale challenges through local demands. Carrying out research aimed at children and youth, considering the multiplicity of childhood(s) and youth, and their localized experiences [

58] is of fundamental relevance for advising on the development of policies and practices to mitigate the effects of climate change and deepen knowledge and the scope of action for/by younger generations.

Limitations

We have argued that studies in Brazil and elsewhere that include the perspectives of children and youth are relevant to a broader perspective on the theme. There are some limitations to these, especially related to sampling procedures. A considerable number of studies are based on questionnaires delivered virtually through such means as Google Forms, and through social media, electronic messaging, or e-mail. On one hand, these methods increase the range of the study, allowing a larger number of people to have access to the questionnaires. On the other hand, they restrict participation to those who have online capacity (both the equipment and reliable access to the internet), potentially excluding a significant section of the young population. Some of these studies are also more likely to attract respondents who already have a previous interest in the topic, because often, the nature of the study is advertised in advance to recruit participants. An online study makes it difficult to verify the identity and characteristics of the sample. It also lacks a mediator, an in-person interviewer who can deal with divergent interpretations of the questions and imprecise responses.

The current analysis does not include an in-depth assessment of differences based on gender, age, public or private schooling, socio-economic factors, or regional distinctions among Brazilian cities. This data set is still under analysis.

The response categories did not include scales. We thought it may be difficult for children and adolescents to differentiate complex feelings, especially younger respondents.