Abstract

This paper expands on the anthropocentric focus of the Self-Directed Flourishing (SDF) framework by introducing the Eco-Systemic Flourishing (ESF) framework. The primary contribution of the ESF is the integration of ecological systems thinking, place-based education, and regenerative learning into existing flourishing frameworks. Methodologically, the paper synthesizes interdisciplinary perspectives from developmental psychology, systems theory and sustainability education and to propose a transformative educational approach. The results outline how the ESF framework positions education as a crucial driver for fostering relational awareness and ecological literacy, thus promoting both human and planetary flourishing. The framework’s implications are significant, offering a scalable model for sustainability integration in educational systems, curriculum design, and policy development. Future empirical validation, through longitudinal studies, is recommended to evaluate ESF’s effectiveness in enhancing educational outcomes and ecological stewardship.

Keywords:

education; learning; flourishing; thriving; well-being; ecosystemic; relational; regenerative; ecology; spirituality 1. Introduction

Recent discussions in educational reform, such as those proposed in Mountbatten-O’Malley and Morris’s “Self-Directed Flourishing” (SDF) framework [1], have underscored the need for a more adaptive, participatory, and student-centered approach to learning. The approach is presented as a conceptual meta-framework designed to address the “Educational Malaise” afflicting 21st-century education—characterized by reductive, performative systems that suppress learner agency and creativity. Grounded in humanistic, constructivist, and philosophical traditions, SDF reframes flourishing not as an externally imposed aim but as a value rooted in learner autonomy, moral reasoning, and adaptive capacity. It rests on three core pillars: recognizing learners as inherently rational, language-using beings (Homo loquens); fostering self-directed learning as the foundation for lifelong adaptability; and positioning flourishing as a condition nurtured through ethical, empowering pedagogy. The framework is animated by three conceptual anchors: co-creativity (value), courage (virtue), and conceptual insight (virtuosity)—equipping learners to navigate complexity, think critically, and co-shape more just, regenerative futures. While the SDF framework rightly challenges outcome-driven educational paradigms, its focus remains human centric. From the perspective of this paper, this neglects the inextricable link between personal flourishing and ecological sustainability, which is a criticism that has also been made towards influential frameworks such as the Harvard Human Flourishing Program (HFP), which defines flourishing in terms of happiness, health, meaning, character, and relationships but neglects ecological and systemic factors [2]. There is increasing global acknowledgement that true flourishing necessitates the recognition that human well-being is inextricably bound to the health of ecological systems [3].

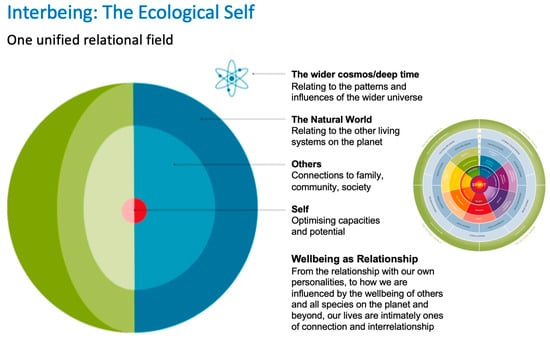

This paper introduces the Eco-Systemic Flourishing (ESF) framework as a transformative approach that integrates human and ecological well-being. ESF extends current human-focused models by embedding ecological awareness and relational thinking at its core. Flourishing is presented as a dynamic, lifelong process shaped by interactions between individuals and their environments. Central to this framework is the idea of relational “Interbeing”, reflecting the interconnectedness of human and ecological systems. The concept of interbeing, originally introduced as a philosophical concept rooted in the Zen Buddhist tradition and popularized by Thich Nhat Hanh [4], is increasingly being supported by interdisciplinary research, including ecological science, quantum physics, systems theory, and Indigenous knowledge systems, all of which emphasize deep interconnectedness as foundational to understanding life and sustainability.

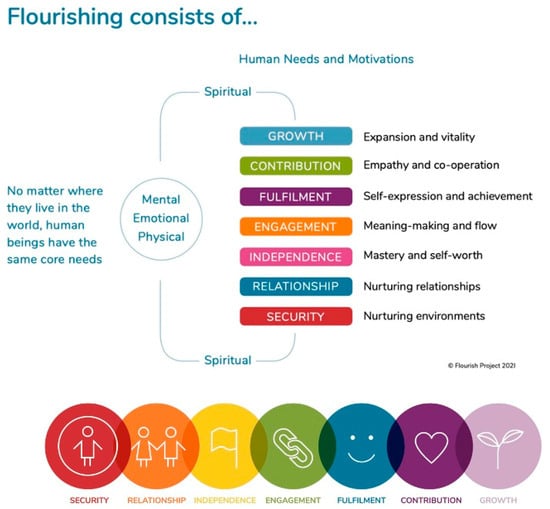

Unlike prevailing paradigms that prioritize human interests often at the expense of environmental integrity, ESF integrates human learning and development with a profound relational consciousness. Flourishing within this framework is characterized not as a static state but rather as an ongoing, dynamic, and interactive life process that begins pre-birth and that is subsequently shaped through lived experience into the values, beliefs, and motivations that underpin human worldviews, behaviors, and decision making. At the core of the system sits the spirit of the child, which is constantly seeking an integrated state of balance and wholeness but that has to respond to the demands of the external systems within which it exists. The ESF framework emphasizes the continual balancing and reciprocal interaction between the internal and external aspects of human developmental needs and defines the seven core aspects shared universally by all human cultures as security, relationship, independence, engagement, fulfilment, contribution, and growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flourish model—human developmental needs and motivations.

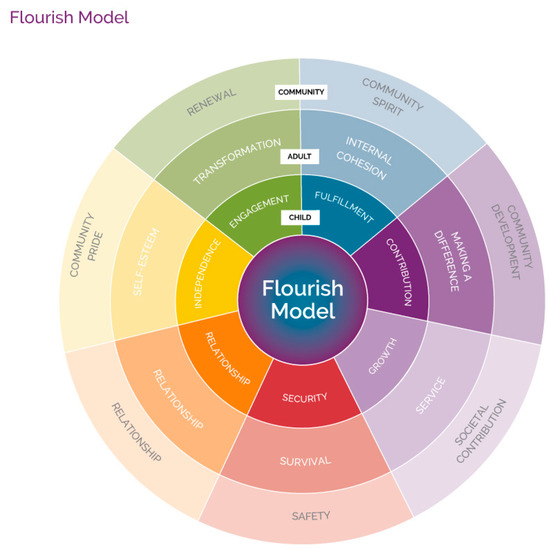

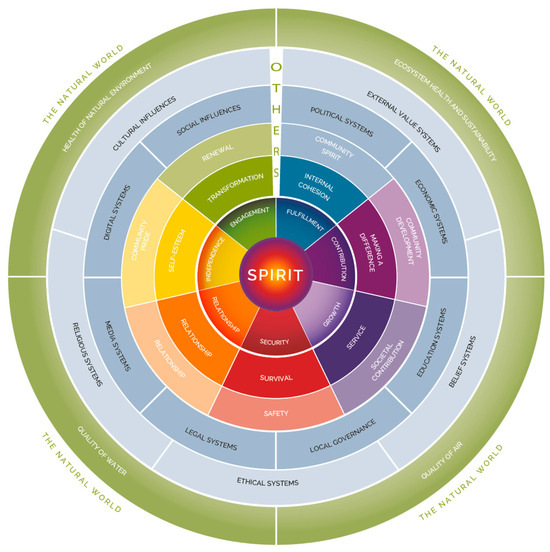

Originally inspired by Richard Barrett’s seven levels of consciousness model [5], the model was then further expanded to encompass early human development and the interconnected and nested nature of social, cultural, and ecological development (Figure 2). Thus, the ESF framework, as a further expansion of the Flourish Model, positions human flourishing within the broader context of ecosystem health, emphasizing interdependency and mutual enhancement as essential conditions for sustainable futures. (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Flourish model—nested human social systems.

Figure 3.

Ecosystemic flourishing framework (ESF).

Figure 4.

ESF framework—interbeing (people, place, and planet).

The framework shows the systemic relationship between the following four core categories of activity, aligning human well-being directly with ecological health and well-being economies that nurture both people and planet [6].

- THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT (NE) This refers to all aspects of the natural environment needed to support life and human activity. It includes land, soil, water, plants, and animals, as well as minerals and energy resources. It also includes the natural principles of interdependence, diversity, adaptability, co-operation, mutuality, reciprocity, circularity, homeostasis, and flow.

- CIRCULAR AND REGENERATIVE ECONOMICS (CRE) This includes all the things that make up a country’s physical and financial assets, which have a direct role in supporting incomes and material living conditions.

- CULTURAL VALUES AND IDENTITY (CVI) This includes the norms, values, and ways of knowing that underpin society and that promote cultural and spiritual health. It includes the study and design of political, economic, and cultural institutions, trust, pride in place, conflict, religion, belief systems, the rule of law, cultural identity, peace, and the connections between people and communities.

- HUMAN CAPACITIES AND POTENTIAL (HCP) This encompasses people’s dispositions, capacities, skills, and knowledge, together with their physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health. These are the things that enable people to participate fully in work and play, study, recreation, and society more broadly. It includes the impact of form, function, and aesthetics on human well-being.

Comparison with Other Ecological and Sustainability-Based Educational Models

The ESF framework significantly diverges from traditional Ecological Sustainability (ES) models such as UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), primarily through its fundamental shift from an anthropocentric orientation to a deeply ecocentric and relational perspective. Traditional ES models focus largely on sustaining human well-being and embedding sustainable practices within existing socio-economic structures, typically emphasizing individual behavioral changes and sustainability literacy. In contrast, ESF adopts an integrative and regenerative educational paradigm, embedding ecological consciousness at its core and emphasizing systemic interdependencies between humans and ecological systems. ESF integrates place-based education explicitly, facilitating deeper connections to local ecological and cultural contexts, whereas conventional ES models tend to maintain standardized, globalized sustainability approaches that may overlook specific local ecological relationships.

Additionally, while traditional ES frameworks minimally incorporate spirituality and diverse epistemologies, the ESF explicitly includes spiritual dimensions, ethical consciousness, and Indigenous knowledge systems. By doing so, ESF positions education as a regenerative force capable of restoring systemic health rather than merely sustaining it, therefore enriching global dialogues around education, ecological integrity, and societal transformation. This explicit incorporation of spirituality and diverse ways of being and knowing contrasts sharply with the generally secular and Western-centric orientation of traditional sustainability models. Consequently, ESF offers a transformative, holistic educational model that deeply aligns with the interconnected nature of global ecological and social challenges, significantly contributing to a richer and more inclusive global conversation (Table 1).

Table 1.

A comparison of traditional ecological and sustainability-based programs with the Ecosystemic Flourishing (ESF) framework.

2. The Current Global Context

The 21st century presents an era of unprecedented ecological, social, and technological change, challenging conventional paradigms of education and human development. Traditional education systems have remained heavily focused on individual success, market-driven outcomes, and human well-being, only recently, due to concerns about climate change, exploring the broader planetary context in which such learning occurs. This paper argues that a paradigm shift is required, integrating ecological systems thinking and regenerative education into models of human flourishing. While the Self-Directed Flourishing (SDF) framework acknowledges the importance of autonomy and adaptability, it falls short in embedding sustainability and ecological well-being into its principles, and this echoes recent criticisms of positive psychology, which, although it has made important contributions to the science of well-being, has increasingly been seen as incomplete, with critics arguing that it neglects structural, ecological, and cultural factors, reinforcing a hyper-individualistic model of flourishing that is detached from planetary realities [7,8]. By framing flourishing as an inherently relational and ecological process, rather than an individual pursuit, the ESF framework seeks to offer a more holistic, inclusive, and scientifically grounded perspective on human development.

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) Global Assessment Report (2019) highlights that human activities have significantly degraded ecosystems, pushing nearly one million species toward extinction, and that transformative changes in governance, education, and behavior are required to reverse this trend [9]. Fostering a right relationship with the planet requires shifting from an extractive and individualistic worldview to one that recognizes mutual interdependence and planetary stewardship. This aligns with the necessity to start living as nature, rather than from, with, or in nature. Models focused on self-direction or self-determination [10] highlight the role of human agency in learning, but they do not account for the dynamic relational contexts in which such learning always occurs. Research in planetary health and environmental psychology shows that well-being is fundamentally connected to ecological stability [11], with the field of human–earth system interactions an area of increasing global interest [12]. The IPBES assessment further stresses that human well-being depends on ecosystem services and that education must reflect this interdependence.

Educational models that neglect the environment risk perpetuating the very crises—climate instability, biodiversity loss, and unsustainable economic models—that education should help solve [13]. The biophilia hypothesis suggests that humans have an innate connection to nature and that engagement with natural environments enhances cognitive function, emotional resilience, and creativity [14]. Studies have shown that students engaged in place-based and nature-immersed education demonstrate improved academic performance, problem-solving skills, and mental health [15,16]. This evidence suggests that education should not only foster personal development but also cultivate ecological literacy—an understanding of how systems interact within and beyond the human sphere [17]. Regenerative education argues that transformative learning must be rooted in nature’s principles, rather than imposed as an external human-driven framework [18].

In 1973, when Arne Naess first coined the term “deep ecology”, he aimed to unify two core ecological principles: the imperative for sustainability and robust environmental ethics that included humanity’s relationship with nature [19]. Additionally, Naess explored an ecological philosophy he called “Ecosophy”, described as a philosophy centered on balance and harmony. He believed deeply in humanity’s innate potential to transcend individual ego, fostering a profound connection with other beings and the broader natural world. This concept was further elaborated by Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi in their work, “The Systems View of Life” [20]:

“Deep ecology views humans and all other forms of life as inherently interconnected within the natural environment. Rather than perceiving the world as a collection of separate entities, it understands existence as an interwoven web of interdependent phenomena. Recognizing intrinsic worth in all life forms, deep ecology positions humans merely as one component within this complex web. Such ecological consciousness is fundamentally spiritual—where the human spirit is understood as a mode of consciousness involving a profound sense of belonging and interconnectedness to the entire cosmos.”(p.12)

Such interconnected worldviews have been intrinsic to ancient and Indigenous societies for millennia. Although it has taken humanity nearly reaching ecological crisis to recognize the importance of reciprocal relations, both political and economic systems are now beginning to reflect an acknowledgment of this critical shift. Quantum theory highlights the fundamental connectedness between observer and observed and the holistic nature of phenomena [21]. Similarly, Indigenous knowledge emphasizes the indivisible unity between the individual and the collective, matter and spirit, and humanity and nature [22]. Thus, individual well-being is inherently linked with the well-being of the greater ecological system, deriving directly from harmonious relationships with nature.

Biological, cognitive, social, and ecological studies illustrate the inherent interdependency of all life, revealing that no organism exists in isolation. Indeed, plants, animals, and microorganisms collectively regulate the biosphere, of which humans are merely a component. A systemic approach suggests that flourishing arises when individual needs align harmoniously with external circumstances, allowing individuals to engage authentically, express their talents, and enhance physical, emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions of life. Thus, flourishing provides profound meaning and purpose, integrating both personal and creative engagement within broader ecosystems. Flourishing is not static but dynamically contextual, demanding continuous adaptation and integration. Adults who achieve integrated health, maintaining a sustainable balance between personal needs and external demands, experience enhanced vitality and overall wellness. Conversely, fragmented health often leads to languishing, characterized by low vitality, emotional emptiness, stagnation, and a pervasive lack of purpose. While languishing is commonly discussed within the realm of mental health, from a systemic perspective, it signals a broader failure to achieve necessary balance and integration essential for holistic well-being. Thus, addressing human flourishing requires recognizing the deeply interconnected nature of life, in which humans represent one species among many within a vibrant relational web [23].

Evolutionary science underscores the comprehensive nature of human flourishing, extending beyond psychological well-being. Optimal human functioning involves physical security, nurturing relationships, personal autonomy, positive environmental interactions, creative expression, lifelong learning, and a profound sense of belonging, purpose, and contribution. Human infants naturally seek warmth, physical closeness, and supportive communities [24]. Right relationship, emphasizing interconnectedness, mutual respect, reciprocity, and harmony, is a foundational principle inherent to all living systems and echoed across various human cultures and philosophies. We inhabit a relational universe, one defined primarily by interconnected processes rather than isolated entities, and our discussions about nature inherently reflect back upon ourselves.

In essence, maintaining equilibrium and harmony within our internal experiences through healthy relational practices with others and the natural world is vital [25]. This equilibrium necessitates cultivating self-awareness and moral capacities that foster sustainable futures. Although the ESF approach acknowledges the influential contributions of leading well-being theorists, it also cautions against an excessive focus solely on individual psychological health. Comprehensive well-being incorporates physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual dimensions, forming a balanced state of existence. Individual wellness inherently includes broader social and ecological contexts, and research consistently shows that emphasizing personal achievements without contributing meaningfully to something larger ultimately leads to superficial success lacking deeper fulfilment. Helen Street highlights this perspective clearly in “Contextual Wellbeing: Creating Positive Schools from the Inside Out” (2018) [26]:

“Well-being transcends the individual’s internal states of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors—it cannot be pursued in isolation. It equally encompasses our relationships, purposeful activities, and broader societal interactions. Well-being involves our existence as social, not merely human, beings, thriving through healthy social contexts and positive interactions. Sustainable happiness and well-being are far less dependent on individual capacities than commonly perceived, and significantly more reliant on the connections and relationships we cultivate.”

3. The Spiritual Core

“The essential quality of the infinite is its subtlety, its intangibility. This quality is conveyed in the word spirit, whose root meaning is ’wind or breath. ‘That which is truly alive is the energy of spirit, and this is never born and never dies.”—David Bohm, Infinite Potential [27]

The term spirit is derived from the Old French espirit, which traces back to the Latin spiritus, meaning “breath”, “soul”, “courage”, or “vital energy”, and is linked to spirare—“to breathe” [28]. Across many ancient and Indigenous belief systems, the act of breathing has symbolized more than a physiological function—it represents the animating force of life. In traditions such as Greek (pneuma), Hebrew (ruach), and Sanskrit (prana), breath is often seen as a manifestation of consciousness, divine presence, or life force [29,30]. This universal symbolism is echoed in the biological interplay between humans, animals, and plants. While animals inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, plants take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen during photosynthesis—a reciprocal exchange that exemplifies the deep interconnection and regeneration inherent in life systems. Even at night, when photosynthesis ceases, plant tissues respire similarly to animal cells, highlighting the cyclical dance of breath and life across all beings.

Although science and spirituality often operate within different epistemological frameworks, there is growing recognition of their complementary roles. Scientists seek to describe physical phenomena through empirical inquiry, whereas spiritual and religious teachers often focus on existential meaning, personal transformation, and altered states of consciousness [31]. Mystical experiences—commonly described as direct, non-intellectual encounters with a greater reality—are frequently associated with feelings of awe, humility, and deep interconnectedness. These moments of “heightened aliveness” may serve as portals into broader understandings of the self and the cosmos [32,33]. As Einstein wrote in 1950 [34]:

“A human being is part of the whole called by us universe, a part limited in time and space. We experience ourselves, our thoughts and feelings as something separate from the rest. A kind of optical delusion of consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from the prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty. The true value of a human being is determined by the measure and the sense in which they have obtained liberation from the self. We shall require a substantially new manner of thinking if humanity is to survive.”

Many of the world’s greatest scientists have expressed such feelings, as their work has led them to explore a deeper, unified, informational reality, and many belief systems and religions recognize this overwhelming sense of wonder as connected to the wholeness of nature. It is a state of relational awareness that is common to young children as they start exploring the world with openness and curiosity [35]. Modern Western spirituality tends to center on contemplative practice and the core values and meanings by which people live. For many this embraces the idea of an ultimate or immaterial reality and envisions an inner path enabling a person to discover the essence of his or her being. This often follows from a profound experience of such a reality beyond normal everyday experience, i.e., a direct and non-intellectual experience of reality that is not bounded by cultural and historical context. Such experiences enable people to transcend the limitations of their adopted personalities and conditioning and often facilitate deep shifts in previously predictable life courses, towards more meaningful, compassionate and purposeful forms of existence. Interestingly, such experiences are often accessed and initiated through bodily feelings and sensations, so the body and the mind both play important roles in giving access to the energetic dynamic of the spirit. It is the successful integration of body, mind and spirit that facilitates the greatest expansion and growth. And it is being able to then authentically express this in ways that have meaning and purpose to us as individuals that facilitates the dynamic of what we might call “Love in Action”. As Dr Scherto Gill says in her 2023 book “Lest we Lose Love” [36].

“In between transcendence and immanence, there are many variations in the way love animates the good life. This suggests that a paradigm of love must not privilege merely the divine vision, nor solely the humanistic ideal, but instead, it must seek an equilibrium between these two. Only love can integrate transcendence and immanence; only love can connect the cosmos, divine, human and nature.“(9)

Our personal well-being is deeply interwoven with the health of the greater whole, emerging from a state of resonance and alignment with the natural environment. Life unfolds across interconnected biological, cognitive, social, and ecological layers, all of which highlight that no organism thrives in isolation. From the tiniest microbe to vast ecosystems, every species—including humans—is embedded in a shared regulatory system that sustains the biosphere. Even our individual human bodies consist of multitudes [37].

4. Uniting Inner and Outer Worlds

Human beings, like all living organisms, inherently seek growth and thriving through a dynamic balance between their internal needs and external environmental demands [38,39]. This fundamental orientation toward flourishing is actualized when nurturing and supportive contexts enable individuals to fulfil essential needs, thereby fostering personal well-being, happiness, enriching relationships, and respect for both others and the natural environment [40,41]. Such conditions naturally cultivate an inclination toward harmony, altruism, and aesthetic appreciation, primarily rooted in secure and loving attachments [42,43]. Conversely, adverse early conditions characterized by trauma, neglect, or inconsistent care can disrupt this innate trajectory. These negative experiences may lead to the suppression of core needs, difficulties in forming trusting relationships, and behaviors harmful to oneself, others, and the environment. Early life conditions thus play a pivotal role, shaping individual values and beliefs that either support or constrain adult flourishing [44,45]. The way societies structure early childhood and caregiving profoundly influences the development of belief systems, power dynamics, and social behaviors. The systems scientist Riane Eisler argues that violence, inequality, and ecological destruction are not inevitable but are often culturally conditioned—beginning with how children are treated. Her Four Cornerstones approach includes family and social structure, gender roles and relations, economic and social relations, and narratives and language [46]. She emphasizes that nurturing, egalitarian environments in early life are essential to cultivating more peaceful, equitable, and sustainable societies.

Childhood development inherently involves navigating the interplay between one’s internal disposition and external influences, driven by curiosity, play, and the willingness to explore. Such exploratory behavior fosters core competencies, aligning with biological tendencies and intrinsic interests. Optimal growth is experienced through focused engagement, vitality, and the rewarding pursuit of mastery. However, external pressures can introduce fears and limitations, disrupting this developmental flow. A continual tension exists between individual identity and the broader collective experience. The human journey begins with an undifferentiated sense of self at conception, evolving through stages of differentiation into a distinct individual identity and ideally culminating in a mature, integrated recognition of interconnectedness and interdependence. This developmental progression aligns with Richard Barrett’s concept of moving from co-dependence through independence to interdependence, emphasizing an evolution from differentiation toward integration [47]. Abraham Maslow originally believed that the highest level of psychological development was the “self-actualization” of full personal potential. But towards the end of his life, he added the further step of “self-transcendence”, which aligns with the need to go beyond the confines of the self:

“Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos.”[48]

Educational institutions significantly influence personal and collective flourishing. Schools shape cultural values, motivations, and personal agency, either nurturing or restricting individual aspirations. Advancing education systems toward more integrative and ecosystemic approaches has immense potential to enhance personal, societal, and planetary health [49]. Such models encourage young people to participate meaningfully in their communities, contributing to equitable opportunities, social harmony, and sustainable futures. The influential Dasgupta Review (2021) [50] underscored the urgency of transforming institutional structures, especially in education and finance, to foster sustainability and preserve natural ecosystems. This transformation requires recognition of the intrinsic and moral value of biodiversity and the necessity of embedding ecological consciousness within economic and social practices.

In alignment with current global initiatives, balancing the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with the Inner Development Goals (IDGs) [51] highlights the importance of exploring internal and external dimensions of societal well-being. Understanding personal experiences, values, and emotions (inside-out) and recognizing how external systemic pressures impact individual well-being (outside-in) are both crucial for sustainable and meaningful human flourishing. As Wilson-Strydom and Walker explore in their 2015 article [52], there are both personal and relational aspects that always need to be taken into account:

Flourishing “in” education requires consideration of the well-being and agency of students. Flourishing “through” education draws attention to the role of education in promoting well-being and flourishing beyond its walls by fostering a social and moral consciousness among students.

Ultimately, flourishing occurs in contexts where individuals feel authentically connected, valued, and empowered within their communities, supported to continually express their unique capabilities in alignment with the broader ecological system.

5. Socio-Ecological Systems and ESF

The Socio-Ecological Systems (SES) framework, developed by Elinor Ostrom and her colleagues, offers a comprehensive method to analyze the intricate interactions between human societies and their surrounding ecosystems [53]. This framework dissects complex systems into four primary subsystems:

- Resource Systems: Encompassing the physical or biological units, such as forests, lakes, or fisheries, that provide resources.

- Resource Units: The specific elements or products derived from resource systems, like timber, fish, or water.

- Governance Systems: The institutions, rules, and norms governing the use and management of resources.

- Users: Individuals or groups who utilize the resources for various purposes.

These subsystems are interconnected and influenced by broader social, economic, political, and ecological contexts. The SES framework’s nested, multilevel structure allows for a nuanced examination of variables affecting system sustainability and resilience.

The ESF framework emphasizes the dynamic interplay between individuals, communities, and the environment. It integrates insights from systems science, developmental psychology, and other disciplines to highlight how personal development and collective well-being are interdependent. The model underscores the significance of early developmental experiences and the cultivation of the sense of interbeing with oneself, others, and the natural world. When juxtaposed, the SES framework and the ESF framework share a foundational systems-based perspective:

- Holistic Perspective: Both frameworks recognize that well-being and sustainability emerge from the complex interactions within and between social and ecological components.

- Nested Structures: They acknowledge multiple levels of influence, from individual or resource units to broader societal or ecosystem contexts.

- Dynamic Interactions: Emphasis is placed on the continuous feedback loops and adaptive processes that shape system outcomes.

By applying the SES framework’s analytical lens to the ESF approach, one can systematically explore how governance structures, resource availability, and user behaviors influence individual and communal flourishing. Conversely, the ESF framework enriches the SES approach by integrating a developmental and well-being-oriented focus, emphasizing how early life experiences and personal growth trajectories impact and are impacted by broader social-ecological dynamics. In essence, the integration of these frameworks fosters a comprehensive understanding of how nurturing individual and collective well-being is intrinsically linked to the sustainable management of our social and ecological environments.

In 1993 [54], Val Plumwood’s call for an “Ecological Self” critiques the Western philosophical tradition that separates humans from nature, reinforcing hierarchies that justify domination over the environment and marginalized groups. In 1999 Paul Maiteny’s “Balance in the Ecosphere” [55] strengthens the case for rethinking education and social structures through an ecosystemic lens, ensuring long-term planetary regeneration and collective human well-being. Similarly, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass (2013) [56] illustrates how Indigenous knowledge is interwoven with scientific understanding, fostering a deep mutuality and reciprocity with the natural world. And in 2017, Laszlo et al. [57] advocate for a radical rethinking of education as a laboratory for societal transformation, challenging the industrial, market-driven paradigm that currently dominates educational systems, with Jude Currivan’s 2023 paper [58] further endorsing the need for a unitive worldview and narrative.

All these approaches align well with the Eco-Systemic Flourishing (ESF) framework, emphasizing education as a means to foster planetary consciousness, relational intelligence, and collective well-being. They champion the move toward a wisdom-based society, where education serves planetary flourishing rather than economic imperatives. This includes the argument expressed by Jennifer Gidley in her 2013 paper “Global Knowledge Futures: Articulating the Emergence of a New Meta-level Field” [59] that universities should foster postformal reasoning—complex thinking that embraces paradox, creativity, and deep systems awareness. In contrast to knowledge as an economic commodity, she emphasizes the intrinsic human capacities for imagination, dialogue, and co-creative knowledge production, positioning education as a catalyst for planetary well-being rather than merely individual success. Otto Scharmer’s recent article “Universities as Innovation Ecologies for Human & Planetary Flourishing” echoes this call, along with the need for it to be “solidly grounded not only in the reality of our challenges but also the essence of our humanity, i.e., the intertwined regeneration of soil, society, and self.” [60]

This reinforces the urgent need to move beyond individualistic flourishing models and adopt an ecosystemic perspective that integrates education, well-being, and planetary health into a unified framework. Through all of these perspectives, we see that the principle of right relationship emphasized in the ESF framework involves not only recognizing interdependence but also honoring the diverse ways of knowing that can guide us towards a more sustainable and just future.

This kind of eco-systemic thinking was embedded in the People’s Pact for the Future [61], which was adopted on 22 September 2024, during the United Nations Summit of the Future held in New York and that included a Global Digital Compact and a Declaration on Future Generations. The Summit brought together over 4000 individuals from heads of state and government, observers, intergovernmental organizations, the UN system, civil society, and non-governmental organizations. The approach acknowledges that cultural contexts and worldviews are fundamental in shaping societal norms and behaviors, influencing how communities interact with their environment and each other, and aims to modernize international cooperation frameworks, ensuring they are equipped to tackle current and future global issues effectively.

6. Eco-Systemic Flourishing (ESF) as a Framework for Regenerative Learning

ESF builds upon the strengths of anthropocentric models and frameworks by embedding ecological consciousness as part of the process (Table 2).

Table 2.

Eco-Systemic Flourishing (ESF) as a framework for regenerative learning.

In doing so, it promotes:

Empirical research consistently supports the idea that ecological literacy and education positively influence sustainability behaviors, further emphasizing the role of meaningful connections with nature in enhancing human flourishing. Studies such as McBride et al. (2013) [88] indicate that higher ecological literacy significantly predicts pro-environmental behaviors among individuals, underscoring the transformative potential of targeted educational interventions. Additionally, Otto and Pensini (2017) [89] demonstrated that experiential nature-based education not only fosters ecological awareness but also strengthens participants’ emotional connections with nature, leading to enhanced sustainability actions. Supporting the link between human flourishing and environmental connectedness, Capaldi et al. (2014) [90] provided compelling evidence that individuals who frequently engage with natural environments experience greater psychological well-being, increased positive affect, and lower stress levels. Similarly, Howell et al. (2011) [91] found that emotional engagement with nature positively correlated with eudaimonic well-being, indicating that fostering personal connections with the natural world is integral to both environmental sustainability and personal fulfillment. These findings align with Chawla and Derr’s (2012) [92] assertion that childhood interactions with nature through educational settings significantly shape lifelong ecological behaviors and overall well-being, reinforcing the critical role of educational programs in promoting sustainable living and human flourishing.

6.1. Recommendations for Educators

- Early Human Development: Integrate transdisciplinary approaches in early education programs to holistically nurture physical, cognitive, emotional, social, and spiritual health, emphasizing nature-based experiences and supportive relationships. Recognize that investments in early childhood profoundly shape lifelong trajectories of health, relational skills, and ecological consciousness.

- Place-Based Learning: Root educational experiences in local ecological and cultural contexts, fostering deep emotional and intellectual connections to community environments, enhancing students’ sense of responsibility and relational intelligence.

- Interdisciplinary Integration: Employ curricula that explicitly connect ecological literacy with traditional academic disciplines, helping students grasp the systemic interconnectedness of ecological, social, and ethical challenges.

- Project-Based Regeneration: Facilitate practical, hands-on regenerative projects where learners actively participate in ecological restoration and sustainable community initiatives, nurturing applied skills and ecological stewardship.

- Cultural and Epistemological Diversity: Incorporate diverse knowledge systems—including Indigenous wisdom, traditional ecological knowledge, and spirituality—within curricula, supporting a deeper relational understanding of interconnectedness with nature and society.

- Reflective and Spiritual Practices: Regularly integrate reflective, ethical, and contemplative practices, promoting emotional intelligence, ecological ethics, and spiritual connections to community and planet.

6.2. Recommendations for Policymakers

- Early Human Development Policies: Prioritize comprehensive early childhood policies and robust funding mechanisms supporting holistic development from infancy onwards, recognizing that investing in early-life experiences yields substantial long-term societal benefits, enhanced individual potential, and sustained ecological awareness.

- Educational Policy Alignment: Align national and regional educational frameworks with ecological literacy and regenerative education principles, embedding ecosystemic flourishing as central to lifelong education. Ensure the adoption of well-being frameworks that reflect an integrative approach to both human and planetary flourishing.

- Cross-sectoral Collaboration: Foster collaborations across educational, environmental, health, and community sectors to create coherent, ecosystemically integrated early childhood and lifelong learning initiatives.

- Assessment and Research Reform: Transition to inclusive assessment methods that measure holistic educational outcomes—including integrated development, ecological consciousness, relational skills, and spiritual growth—and support longitudinal research into the effectiveness of early developmental investments.

- Professional Development: Provide extensive professional development programs in ecological systems thinking, early human flourishing, regenerative educational practices, and culturally responsive methodologies to build educator capacity for meaningful systemic change.

- Infrastructure and Resource Allocation: Ensure adequate resources and infrastructure development for experiential and nature-rich learning environments, fostering immersive educational experiences that encourage active ecological engagement from early childhood through lifelong learning.

- Pathways to Application and Empirical Validation of the ESF Framework: A core advantage of the ESF framework lies in its use of clearly defined domains and levels of well-being that are both scalable and context sensitive. Specifically, the framework organizes developmental outcomes across seven nested human needs—security, relationship, independence, engagement, fulfilment, contribution, and growth—each of which can be evaluated in terms of individual experience, community interaction, and systemic support. These are mapped across four interdependent domains: the natural environment (NE), circular and regenerative economy (CRE), cultural values and identity (CVI), and human capacities and potential (HCP). This multidimensional mapping enables the design of assessment tools that are flexible enough for school settings, yet robust enough for regional and national policy integration.

To establish the ESF framework as both a transformative philosophy and a practical framework for education, there is an urgent need to now initiate empirical pathways that explore its validity, adaptability, and scalability across diverse contexts. The richness and interdisciplinary scope of the ESF model invite a multi-tiered research agenda, rooted in participatory, transdisciplinary, and regenerative inquiry.

6.3. Focus on Early Nurture

The framework is unique in that it places the developmental well-being of young children at the center of the system. Through evidence-based strategies, large-scale policy advocacy, and community-driven interventions, the initiative will seek to:

- Emphasize the spiritual nature of childhood and the innate qualities of harmony, co-operation, and wholeness that underpin natural human development.

- Empower parents, caregivers, and educators with practical tools for fostering healthy brain development, secure attachments, and emotional well-being.

- Strengthen the evidence base supporting the case for baby and child developmental rights and the focus on the flourishing of future generations.

- Reimagine early childhood education with nature-based, relational, and trauma-informed approaches.

- Influence global policies to reflect the science of nurture, driving investment in early life development as a catalyst for sustainable economic and social progress.

- Leverage technology ethically to enhance human connection and minimize digital distraction in childhood.

- Partner with global leaders across disciplines to ensure that nurturing practices are at the core of societal transformation.

6.4. Pilot School Implementation

During its early development period, and without any external funding, the Flourish Project has already achieved considerable success through having its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Inner Development Goals (IDGs) Handbooks for Schools, which were made freely available online, adopted by early years settings, primary/elementary schools and leading practitioners in more than 30 countries worldwide:

ZIMBABWE, ENGLAND, SCOTLAND, INDIA, AUSTRALIA, SOUTH KOREA, VIETNAM, MONGOLIA, NEPAL, TAIWAN, SOLOMON ISLANDS, MALTA, COLOMBIA, SPAIN, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES, JAPAN, CHINA, RWANDA, SWEDEN, CAMBODIA, MALAYSIA, CROATIA, SOUTH AFRICA, PHILIPPINES, INDONESIA, BRAZIL, TANZANIA, DENMARK, GERMANY, PERU, NETHERLANDS.

It is currently exploring the development of an online resource platform that would enable pilot programs to be initiated in diverse school contexts, from preschool/nursery settings to primary/elementary schools, middle schools, high schools, universities and teacher training colleges. In this way, educators and researchers could design and co-evaluate interventions using action research methodologies. Indicators of success could include improved student agency, ecological engagement, increased sense of purpose, and demonstrable pro-social behaviors aligned with regenerative principles and planetary stewardship. Supportive partners could include organizations that are at the forefront of new paradigm thinking about how we can create a more caring, peaceful and sustainable world.

6.5. Framework-Embedded Assessment Tools

To assess the practical efficacy of the model, new evaluative instruments are needed that measure flourishing beyond standard academic outcomes. This includes tools for mapping developmental integration across the ESF’s four core domains and seven levels, including indicators for ecological attunement, community involvement, and spiritual literacy. What has become clear in the early development period of the project is that, rather than presenting the ESF primarily as an alternative framework in its own right, it instead provides a way of measuring the level of integrated thinking behind existing frameworks and suggests ways of expanding and optimizing their approaches to encompass a more ecosystemic understanding of flourishing. Such an approach, particularly through the use of digital technology, would align well with the current interest in developing national well-being indicators for schools, such as that being called for through the BeeWell Initiative and the UK’s Our Well-being, Our Voice Campaign [93].

6.6. Cross-Cultural and Place-Based Adaptability

Given ESF’s emphasis on context and relational identity, research should explore how the model adapts to different cultural, ecological, and linguistic communities. Participatory ethnographic approaches and Indigenous research methodologies can ensure the model remains grounded in local knowledge systems while retaining its global relevance.

6.7. Practitioner Training and Reflective Praxis

The successful application of ESF depends heavily on the training and disposition of educators. Professional development programs should be co-developed with teachers and community leaders, emphasizing reflective praxis, ecological systems thinking, and contemplative pedagogy. Evaluative studies could measure changes in educator mindset, relational pedagogy, and classroom culture following such training.

6.8. Integration with Socio-Ecological Systems Research

The ESF model can be systematically linked with Ostrom’s Socio-Ecological Systems (SES) framework to examine governance, resource use, and human development in educational and community settings. Such integration allows for systemic mapping of feedback loops between individual flourishing, institutional structures, and environmental stewardship—creating robust case studies and policy-oriented insights.

6.9. Citizen Science and Regenerative Learning Projects

Learners can become researchers of their own communities through citizen science and local ecological restoration projects. These experiences not only ground abstract principles but also offer measurable environmental impacts and foster eco-social resilience. These projects can serve as living laboratories for validating the “regenerative learning” aspect of the ESF framework.

6.10. Toward a New Research Paradigm: From Measuring Outputs to Cultivating Wholeness

Ultimately, the empirical testing of the ESF framework will require a new research paradigm—one that honors both quantifiable outcomes and the qualitative, subjective, and relational dimensions of human experience. Such a paradigm must embrace systems dynamics, narrative inquiry, and ethical reflexivity as part of a holistic evidence base. The goal is not only to validate flourishing as a systemic process but also to co-create environments where individuals, communities, and the planet are mutually enriched.

Recent global developments reflect an accelerating shift toward systemic, multidimensional approaches to well-being measurement, particularly in the domains of public policy and education. National frameworks such as New Zealand’s Living Standards Framework [94] and Well-being Budget, Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index [95], the United Kingdom’s ONS Measures of National Well-being [96], Canada’s Canadian Index of Well-being [97], and Finland’s inclusive well-being models [98] have begun to reframe policy planning around human and ecological thriving rather than economic output alone. The OECD’s Better Life Index [99] and the UNDP’s expansion of the Human Development Index [100] similarly point toward more holistic metrics of progress. In Canada, the Nova Scotia Quality of Life Index [101] represents a leading example of community-led, place-based well-being measurement, tracking 40+ indicators and supporting participatory governance at regional levels. Within education, school-focused initiatives such as the UK’s BeeWell Programme [102], New Zealand’s Wellbeing@School toolkit [103], UNESCO’s Happy Schools Framework [104], and CASEL’s social-emotional assessment tools in the United States [105] demonstrate practical pathways for embedding wellbeing into curricula and institutional design. Youth-led campaigns, including the UK’s Our Well-being, Our Voice initiative [106], are further mobilizing efforts to make well-being measurement statutory within schools.

Collectively, these models signal a growing consensus around the need for integrated, regenerative indicators that account for human, social, and ecological interdependence. The Flourish Project’s ESF framework builds on and extends these initiatives by:

- Adding ecological and spiritual dimensions

- Embedding child/youth development from early years through intergenerational systems

- Providing a systemic map across natural, economic, cultural, and human capacities

- Offering the possibility of modular, co-designable tools suitable for schools, cities, and nations

This positions the ESF as a second-generation well-being framework—not just measuring current status, but nurturing transformation and regeneration.

7. Conclusions

In an era of unprecedented environmental and social challenges, rethinking education through an ecological lens is not merely an option but a necessity. The Eco-Systemic Flourishing (ESF) framework, as outlined in this paper, offers a transformative alternative to traditional educational models by integrating self-directed learning with ecological consciousness. It builds upon human-centric approaches by embedding sustainability, regenerative education, and relational well-being core principles. Education should no longer be confined to the narrow metrics of individual success and economic productivity; rather, it must cultivate an understanding of interdependence, planetary health, and systemic responsibility. This requires a paradigm shift from extractive, outcome-driven learning to regenerative, place-based, and community-embedded education.

By aligning educational models with ecological systems thinking, we ensure that learning contributes not only to individual growth but also to the resilience and vitality of the broader socio-ecological landscape. The principles of right relationship, biophilia, and regenerative learning underscore that human flourishing is inseparable from planetary flourishing. As the Dasgupta Review (2021) and the IPBES Global Assessment (2019) highlight, achieving a sustainable future requires a fundamental reorientation of education toward ecological and ethical imperatives. By embedding Eco-Systemic Flourishing into educational policies, curricula, and pedagogies, we can empower future generations to act as stewards of both their own development and the planet’s well-being. Schools and learning environments must be reimagined as ecosystems of care, creativity, and community engagement, where education serves not only as a means of individual empowerment but also as a catalyst for planetary regeneration.

As nations increasingly seek to implement holistic well-being frameworks, including those linked to the SDGs and Future Generations initiatives, the ESF framework provides an integrative measurement and design tool that aligns ecological, cultural, economic, and human developmental dimensions into one coherent system. It translates philosophical principles into measurable action, enabling diverse actors—from policymakers to educators—to embed relational and regenerative priorities into daily practice. Additionally, the ESF’s alignment with both the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the evolving Inner Development Goals (IDGs) underscores its unique ability to unite external policy goals with internal human capacities—ensuring that the path to planetary regeneration is both systemic and human centered.

In sum, the ESF framework presents a compelling vision for education that is integrative, dynamic, and future-oriented, ensuring that learning is deeply connected to the social, environmental, and ethical dimensions of human existence. If we are to navigate the 21st century’s complexities with wisdom and resilience, education must evolve beyond its human-centric focus to embrace the interconnected reality of life itself. Only then can we truly expand the paradigm and foster a flourishing world for all. As Vanessa de Oliveira Andreotti explores in her book Hospicing Modernity (2021) [107], this includes ways of thinking and knowing that cannot be easily captured by the conditioned modern mind and senses: non-anthropocentric, non-teleological, non-dialectical, non-universal and non-Cartesian possibilities, such as those expressed through the “Other” narrative developed by a global education center in Pincheq, a tiny village between Pisac and Cuzco in Peru:

The Apu Chupaqpata Global Education Centre’s Global Education Principles

1. The entire planet Earth (i.e., Pachamama) is my home and country; my country is my mother, and my mother knows no borders.

2. We are all brothers and sisters: humans, rocks, plants, animals and all others.

3. Pachamama is a mother pregnant with another generation of non-predatory children who can cultivate, nurse, and balance forces and flows and who know that any harm done to the planet is harm done to oneself.

4. The answers are in each one of us, but it is difficult to listen when we are not in balance; we hear too many different voices, especially in the cities.

5. The priority for life and education is balance: to act with wisdom, to balance material consumption, to learn to focus on sacred spiritual relationships, and to work together with the different gifts of each one of us with a sense of oneness. Our purpose is to learn, learn and learn again (in many lives) to become better beings.

6. There is no complete knowledge; we all teach, learn and keep changing: it is a path without an end. There is knowledge that can be known and described, there is knowledge that can be known but not described and there is knowledge that cannot be known or described.

7. Our teachers are the Apus (the mountains-ancestors), Pachamama, the plants, what we live day by day and what has been lived before, the animals, our children, our parents, the spirits, our history, our ancestors, the fire, the water, the wind, and all the different elements around us.

8. The serpent, the puma and the condor are symbols of material and non-material dimensions, of that which can be known, of that which cannot be known or determined, and of the connections between all things.

9. The traditional teachings of generosity, of gratitude, and of living in balance that are being lost are very important for our children—it is necessary to recover them.

10. The world is changed through love, patience, enthusiasm, respect, courage, humility and living life in balance. The world cannot be changed through wars, conflicts, racism, anger, arrogance, divisions and borders. The world cannot be changed without sacred spiritual connections.

(Apu Chupaqpata Global Education Centre, 27 July 2012).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Mountbatten-O’Malley, E.; Morris, T.H. Self-directed flourishing: A conceptual meta-framework for dealing with the challenges of 21st-century learning and education. Qual. Educ. All 2025, 2, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willen, S.S. Flourishing and health in critical perspective: An invitation to interdisciplinary dialogue. SSM—Ment. Health 2022, 2, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, A. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hanh, T.N. Interbeing: Fourteen Guidelines for Engaged Buddhism; Parallax Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, R. The Metrics of Human Consciousness; Lulu: Morrisville, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fioramonti, L.; Coscieme, L.; Costanza, R.; Kubiszewski, I.; Trebeck, K.; Wallis, S.; Roberts, D.; Mortensen, L.F.; Pickett, K.E.; Wilkinson, R.; et al. Wellbeing economy: An effective paradigm to mainstream post-growth policies? Ecol. Econ. 2022, 192, 107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marecek, J.; Christopher, J.C. Cultural critique and positive psychology: Are they compatible? Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2217. [Google Scholar]

- Fryberg, S.A.; Covarrubias, R.; Burack, J.A. Cultural models of education and academic performance for Indigenous and Latino students. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mago, A.; Dhali, A.; Kumar, H.; Maity, R.; Kumar, B. Planetary health and its relevance in the modern era: A topical review. SAGE Open Med. 2024, 12, 20503121241254231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Human Earth System Interactions. 2025. Available online: https://www.pnnl.gov/human-earth-system-interactions (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap. United Nations Educational; Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rickinson, M. Learners and Learning in Environmental Education: A critical review of the evidence. Environ. Educ. Res. 2001, 7, 207–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, D.W. Ecological Literacy: Education and the Transition to a Postmodern World; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ellyatt, W. Optimising Worldviews for a Flourishing Planet: Exploring the Principle of Right Relationship. Challenges 2024, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, A. The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement. A summary. Inq. Interdiscip. J. Philos. 1973, 16, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P.L. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. Wholeness and the Implicate Order; Routledge: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, G. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence; Clear Light Publishers: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, T. The Ecological Thought; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Narvaez, D. Returning to Evolved Nestedness, Wellbeing, and Mature Human Nature, an Ecological Imperative. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2024, 28, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H.; Verden-Zoller, G. The Biology of Love. In Focus Heilpadagogik; Opp, G., Peterander, F., Eds.; Ernst Reinhardt: Munchen, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Street, H. Contextual Wellbeing, Creating Positive Schools from the Inside Out; Wise Solutions: Plymouth, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Infinite Potential: The Life and Ideas of David Bohm. Available online: https://www.infinitepotential.com/the-film (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Harper, D. Online Etymology Dictionary. 2024. Available online: https://www.etymonline.com/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Eliade, M. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion; Harcourt: Hong Kong, China, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein, G. The Yoga Tradition: Its History, Literature, Philosophy and Practice; Hohm Press: Chino Valley, AZ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tarnas, R. Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View; Plume: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- James, W. The Varieties of Religious Experience; Longmans, Green & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, J.N. Revisioning Transpersonal Theory: A Participatory Vision of Human Spirituality; SUNY Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. Letter to Dr. Robert S. Marcus, 12 February 1950. In The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, D.; Nye, R. Investigating Children’s Spirituality: The Need for a Fruitful Hypothesis; Routledge: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, S. Lest We Lose Love; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, E. I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life, 1st ed.; Ecco, An Imprint of Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.R. On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner, D. Born to Be Good: The Science of a Meaningful Life; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss; Volume 1: Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk, B. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Narvaez, D.; Panksepp, J.; Schore, A.N.; Gleason, T.R. Evolution, Early Experience and Human Development: From Research to Practice and Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler, R. Building a Caring Democracy: Four Cornerstones for an Integrated Progressive Agenda. Interdiscip. J. Partnersh. Stud. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barrett, R. Love, Fear and the Destiny of Nations; Lulu: Morrisville, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature; Viking Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971; p. 269. [Google Scholar]

- Ellyatt, W. Education for Human Flourishing—A New Conceptual Framework for Promoting Ecosystemic Wellbeing in Schools. Challenges 2022, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasury, H.M. The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review; HM Treasury: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Inner Development Goals. Available online: www.innerdevelopmentgoals.org (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Wilson-Strydom, M.; Walker, M. A capabilities-friendly conceptualisation of flourishing in and through education. J. Moral Educ. 2015, 44, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumwood, V. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maiteny, P. Balance in the Ecosphere: A Perspective. Eur. Jud. 1999, 32, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, R. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants; Milkweed Editions: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo, A. Leadership and systemic innovation: Socio-technical systems, ecological systems, and evolutionary systems design. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2018, 28, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currivan, J. How an emergent cosmology of a nonlocally unified, meaningfully in-formed and holographically manifested Universe can underpin and frame the biological embodiment of quantum entanglement. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2023, 185, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidley, J. Global Knowledge Futures: Articulating the Emergence of a New Meta-level Field. Integral Rev. 2013, 9, 145–172. [Google Scholar]

- Scharmer, O. Universities as Innovation Ecologies for Human & Planetary Flourishing; Medium: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Peoples Pact for the Future; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024.

- Margulis, L.; Fester, R. (Eds.) Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D.J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene; Duke University Press: Durham, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, D.W. Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect; Island Press: Washington, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Biggs, R.; Norström, A.V.; Reyers, B.; Rockström, J. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Sacred Ecology; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, G. Look to the Mountain: An Ecology of Indigenous Education; Kivaki Press: Durango, CO, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, D.C. Designing Regenerative Cultures; Triarchy Press: Dorset, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mang, P.; Reed, B. Regenerative Development and Design: A Framework for Evolving Sustainability; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, J. Regenerative Capitalism: How Universal Principles and Patterns Will Shape Our New Economy; Capital Institute: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. All About Love: New Visions; William Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, C. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Held, V. The Ethics of Care: Personal, Political, and Global; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: Hartford, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Sustainable Education: Re-Visioning Learning and Change; Green Books: Dartington, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, D. Place-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities; Orion Society: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald, D.A.; Smith, G.A. Place-Based Education in the Global Age: Local Diversity; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, C. Educating for Hope in Troubled Times: Climate Change and the Transition to a Post-Carbon Future; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World; Island Press: Washington, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Continuum: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Benkler, Y. The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens, G. Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. Int. J. Instr. Technol. Distance Learn. 2005, 2, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, B.B.; Brewer, C.A.; Berkowitz, A.R.; Borrie, W.T. Environmental literacy, ecological literacy, ecoliteracy: What do we mean and how did we get here? Ecosphere 2013, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J.; Dopko, R.L.; Passmore, H.-A.; Buro, K. Nature connectedness: Associations with well-being and mindfulness. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.; Derr, V. The development of conservation behaviors in childhood and youth. In The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology; Clayton, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 527–555. [Google Scholar]

- Our Wellbeing, Our Voice Campaign. 2025. Available online: https://www.ourwellbeingourvoice.org (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- New Zealand Treasury. The Wellbeing Budget 2019. Available online: https://www.treasury.govt.nz (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Ura, K.; Alkire, S.; Zangmo, T.; Wangdi, K. A Short Guide to Gross National Happiness Index; Centre for Bhutan Studies: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Statistics. Measuring National Wellbeing: Quality of Life in the UK. 2023. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Canadian Index of Wellbeing (CIW). How Are Canadians Really Doing? University of Waterloo: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2016.

- Hämäläinen, T.J. Towards a Sustainable Wellbeing Society; Sitra: Ruoholahti, Helsinki, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2011–2024). Better Life Index. Available online: https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Report 2020: The Next Frontier—Human Development and the Anthropocene; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Engage Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia Quality of Life Initiative. 2023. Available online: https://nsqualityoflife.ca/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Layard, R.; De Neve, J.-E. BeeWell Project Overview; Manchester Institute of Education: Manchester, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, S.; Wylie, C. Wellbeing@School: Evaluation and Toolkit; New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER): Wellington, NZ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Bangkok. Happy Schools: A Framework for Learner Wellbeing in the Asia-Pacific; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, J.; Weissberg, R.P.; Durlak, J.A.; O’Brien, M.U. SEL Assessment Guide; Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL): Chicago, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Global Action Plan & Youth Wellbeing Coalition. Our Wellbeing, Our Voice Report; Global Action Plan: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira Andreotti, V. Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and Implications for Social Activism (Sample Chapters); North Atlantic Books: Berkeley CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).