1. Introduction

Food insecurity, which involves the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods [

1], is an ongoing challenge that imposes detrimental public health and sustainability consequences on societies worldwide [

2]. Greater than 10 percent of the U.S. population experiences food insecurity [

3], and poor health outcomes related to food insecurity pose a persistent public health burden [

4]. Food insecurity creates tenuous circumstances for both human and social sustainability by contributing to the development and perpetuation of human health and societal inequities [

5]. The United Nations (UN) listed (1)

No Poverty, (2)

Zero Hunger, and (3)

Good Health and Wellbeing at the top of their 2023 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) [

6].

In being relevant to three of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, preventing food insecurity could yield manifold benefits for health and sustainability. Achieving the UN’s first SDG of

No Poverty would be exceedingly beneficial toward widespread alleviation and prevention of food insecurity, as eliminating food insecurity requires a successful “upstream” elimination of poverty, which is the primary contributor to food security [

7]. Accomplishing the UN’s first SDG would also have a monumental impact on the second SDG of

Zero Hunger, as the most severe poverty produces the most extreme levels of food insecurity involving hunger [

8]. Succeeding in the third SDG of

Good Health and Wellbeing will require food security to be pervasive enough that health equity is also realized across the financial income spectrum. Among humans, widespread attainment and maintenance of good health and wellbeing is contingent on regular access to and consumption of healthy food (e.g., food security) [

9].

The negative impact of food insecurity on health is often the result of nutritional deficiencies and/or imbalances that increase the risk of chronic diseases. As a social determinant of health, food insecurity has been connected to unhealthy behaviors and poor health outcomes, which can include disordered eating [

10], low physical activity levels [

11], cognitive difficulties [

12], nutritional deficiencies [

13], overweight and obesity [

14], type-2 diabetes [

15], heart disease [

16], and cancer [

17]. Food insecurity disparities in the U.S. persist among individuals who are low-income; Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC) [

18]; female [

19]; and/or are a single parent [

20]. These vulnerable individuals live with a greater risk of experiencing food insecurity and are more likely to encounter barriers when attempting to purchase healthy food and access food assistance resources.

Various federal and non-profit food assistance programs exist that are designed to address food insecurity, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; The Emergency Food Assistance Program; community food banks and food pantries; and community gardens. However, for those who either do not qualify for federal food assistance or want to further supplement their access to healthy food, there are networks of food banks in the U.S. that facilitate the distribution of free food to individuals experiencing food insecurity who otherwise would not be able to access a sufficient amount of healthy food for themselves or their families [

21]. Most food banks operate using a warehouse model to collect and store donated food for distribution to food pantries and other non-profit organizations that serve on the frontline in low-income communities [

22]. Understandably, the prevalence of food insecurity among food pantry clients in the U.S. is substantially higher when compared to the general population [

23].

A majority of food insecurity interventions conducted among food pantry clients in the U.S. have aimed to eliminate skill-related barriers relating to obtaining food and meal preparation through nutrition education and instructional cooking classes [

24,

25]. However, individuals experiencing food insecurity encounter several other barriers that prevent them from accessing healthy food and have been seldom addressed with research interventions. The most pervasive of these barriers include inadequate finances [

26], unreliable transportation [

27], low skills related to identifying and preparing healthy food [

28], and insufficient information concerning the availability of food assistance resources [

29]. A study that examined the impact of barriers to food assistance resources has highlighted how the prevalence of food insecurity was higher among individuals who experienced barriers to accessing food assistance in comparison to those who reported no barriers [

30]. In a separate study, it was determined that individuals who were experiencing food insecurity had greater odds of encountering barriers to accessing food assistance when compared to those who were food secure [

31].

Despite the advances that have been made concerning the removal of barriers to accessing healthy food among individuals who are food insecure, there has been limited progress toward removing the barrier of insufficient information that can prevent vulnerable individuals from accessing readily available food assistance. Nudging has emerged as a useful means of informing and guiding the behaviors of participants in research interventions that aim to improve health-related outcomes [

32]. In general, nudges are minor modifications in the environment that are simple, non-coercive, and feasible to implement [

33]. A minor modification in the environment that is initiated by a nudge could involve the communication of previously unknown information that details an available resource and subsequently prompts the recipient to utilize the specified resource. Research interventions using informational nudges have yielded improvements in dietary behaviors among adults [

34]. Keeping in mind the nutritional impact of food insecurity on people, it should be considered how informational nudges might influence behaviors (e.g., food assistance utilization) toward improved food security.

When information is a prerequisite for individuals to access much-needed resources, informational nudges can serve as behavioral prompts that deliver essential insight about relevant and accessible resources. Informational nudges in the form of emails have been tested in a study among college students as an intervention method to remove information barriers to accessing basic needs [

35]. The informational nudges used in the study communicated the presence of a campus-based resource center, a physical address, the hours of operation, a list of available services, and an invitation for students to utilize the center. Outcomes from this study emphasized how the utilization rate of services at the resource center (e.g., food pantry, clothing closet, textbook lending) was higher among individuals who received the emails compared to those who were not emailed. A separate intervention study that aimed to address basic needs insecurity used informational nudges via text messages to determine whether communicating available financial support services could increase the utilization of emergency aid [

36]. Findings from this research highlighted that emergency aid application rates were greater among individuals who received the text messages when compared with those who did not receive the texts.

Informational support is vital for individuals and families who need access to critical resources that are vital for their basic needs [

37]. Regarding food assistance, information about accessible resources can be a key difference maker for vulnerable individuals when it comes to them being food secure or experiencing food insecurity [

38], as those who are at risk of food insecurity may have access to proximal food assistance (e.g., food pantries) while not knowing about the resources that are available to them [

29]. Individuals experiencing food insecurity have reported that the information they most commonly lack concerning food assistance involves the physical location of the resource, the hours of operation, and whether or not they are eligible to receive food assistance [

30]. Vulnerable people who lack essential resources typically require key information about available assistance that can help address their specific needs. Such key information can often be delivered using informational nudges via virtual messaging to communicate relevant details concerning assistance that can help alleviate resource-related shortcomings [

35].

Nudging is an increasingly common intervention approach used in research studies that have aimed to promote the adoption of behaviors that support a healthy lifestyle and good health [

32]. Text message-based informational nudging has emerged as a practical approach for achieving desired changes in behavioral health interventions through the tailoring of message content, the initiation of a messaging dialogue, and consistent correspondence to communication [

39]. A meta-analysis of intervention studies that aimed to improve health outcomes through informational nudges delivered via text messages determined that a sizeable majority of included studies were successful in achieving their desired outcomes concerning smoking cessation, weight loss, increased physical activity, reduced substance use, improved nutritional intake, healthier eating behaviors, and several other behavioral health outcomes [

40]. Findings from a separate meta-analysis of studies that tested the effect of nudges on dietary behavior indicated that nudging largely increased healthy eating behaviors [

34]. Although changes in food security status were not tracked, separate research involving a randomized controlled trial among adults who were food insecure was successful in applying nudges toward increased purchases of healthy fruits and vegetables [

41].

The extant literature elucidates the promising potential of using informational nudging to achieve desirable food security improvements toward enhanced human health and behavior. Therefore, the aim of this qualitative study (Phase 1) was to construct and test a text message for use as an informational nudge in a feasibility study (Phase 2) designed to estimate the limited efficacy and acceptability of the food insecurity intervention. The anticipated end product of this phase 1 study was a finalized informational nudge (e.g., text message) tailored to promote food security among adults residing in an urban southwest U.S. community.

3. Results

Community members (

n = 10) who participated in the interview process for testing the text messages as informational nudges (

Table 1) had an average age of 33.2 (SD = 13.9) years old, and most participants were male (60%), non-White (70%), and college graduates (90%).

The first question that participating community members were asked during their interviews was “What do you think the message is trying to convey?” Participant 1 stated, “The message is pretty informative. It gives you everything about like when [NourishPHX] is open from what time to what time its open and where it is.” Shorter responses included “It’s trying to let people know about this SNAP food benefits” (Participant 8) and “That help is available” (Participant 9). Other answers included details that were included in the text message, like “The times available to visit the food pantry and the address” (Participant 4) and “The hours of operation, the location, and the name of the business” (Participant 6), along with “It’s trying to convey not only operational information, like time, address, whatever, but also the fact that there are SNAP food benefits” (Participant 7). Participant responses to this question frequently mentioned how the message was conveying specific details concerning the availability of food assistance resources.

The second interview question that participants were asked was “On a scale from 1–5, with 5 being the best, how persuasive or convincing do you think this message would be for food pantry clients?”, which was followed by “Why did you choose this rating?” Starting with the lowest rating, Participant 5 provided a rating of 2 and stated, “I don’t see an immediate benefit on why I should do this.” Five participants provided a rating of 3 (Participants 2, 3, 6, 7, and 9) and commented that “It’s a two hour window through just Monday through Friday, so I feel like it makes it hard for people” (Participant 2); “It’s not persuasive, just more informational” (Participant 3); and “It would have been a 5 if it would have detailed some more of the benefits” (Participant 6). Two participants gave a rating of 4 (Participants 8 and 10), and one of those participants stated, “It’s pretty convincing. Everything is very clear, but maybe in the message [you] could let people know more about what SNAP food benefits entailed” (Participant 8). Two separate participants gave the highest rating of 5 (Participants 1 and 4) while saying, “It’s really incentivizing for people to look into it” (Participant 1) and “It gives all the information needed” (Participant 4). The average rating provided by the participant sample was a mean score of 3.5 (SD = 0.97). This rating suggested that modifications to the text message could improve how persuasive or convincing it would be when communicated to food pantry clients. Participants frequently stressed the need for greater detail about the available food assistance resources.

The third interview question that participants were asked was, “On a scale from 1–5, with 5 being the best, how personally relevant do you think this message would be for food pantry clients?”, which was followed by “Why did you choose this rating?” Beginning with the lowest rating, Participant 5 provided a score of 2 while stating, “It’s generic.” Participant 8 gave a rating of 3 and said, “[I don’t know] what SNAP food benefits entail.” Three participants provided a rating of 4 (Participants 2, 3, and 9) while mentioning, “People that need the food, they can go out there and get it” (Participant 2) and “Very relevant” (Participant 3). The five remaining participants provided a rating of 5 (Participants 1, 4, 6, 7, and 10) and commented, “You can register for the SNAP food benefits. So I think it’s pretty relevant” (Participant 1); “If they’re looking for food then I don’t think it could be more relevant” (Participant 5); “It’s such an important benefit and asset to people in need” (Participant 6); and “Very beneficial and relevant, especially if you’re someone who is frequently visiting food pantries” (Participant 10). The average rating provided by the participant sample was a mean score of 4.2 (SD = 1.03). This rating indicated that, from the hypothetical perspective of a food pantry client, the information within the text message was perceived as relevant while still showing room for improvement. The high relevance of food-related assistance for food pantry clients was frequently mentioned during interview responses to this question.

The fourth interview question asked participants, “Was this message clear?”, followed by “Why not?” if an answer of no was provided. One participant (Participant 2) indicated “No” and followed the initial response with “It could be clearer. I think that maybe adding a picture showing exactly where the address is.” The other nine participants (Participants 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) stated “Yes”. Aside from one participant desiring that a visual aid accompany the message, a large majority of participants reported that the message was communicated in a clear manner.

The fifth interview question asked participants, “Was there anything about this message that you particularly liked?” A primary theme that emerged from participant responses to the fifth interview question highlighted the usefulness of the informational content within the text messages, as certain replies to this question included, “How many details the message actually covers” (Participant 1) and “This is who it’s from, and, you know, a greeting is always nice that their name is known” (Participant 4), along with “It presented the key elements of the information such as the hours of operation and location” (Participant 6). Responses also emphasized how participants liked the structure of the messages, as answers to this question included “That it was short and to the point” (Participant 5), “I liked the flow of the message. The fact that it was brief” (Participant 6), and “I like that it was short.” (Participant 10). Another theme that emerged from the fifth interview question included participants liking the friendly tone of the text message. Participants particularly liked the “Take care” sendoff at the end of the message (Participants 3, 4, and 7), and another participant liked how the nudge was “inviting me to come in” (Participant 6). Participants also suggested that they liked that the name was included in the message by stating, “It’s good to have the name” (Participant 9). A separate participant stated, “You’re trying to help people out in the community” (Participant 2). Overall, participants frequently highlighted how they liked the text message’s informational content, its wording structure, and how it was communicated in a friendly way.

The sixth interview question asked participants, “Was there anything about this message that you particularly disliked?” Five participants responded with “No” (Participants 1, 4, 6, 7, and 10). One participant stated, “I kind of wish the format was a little spaced out more” (Participant 9). Two participants were uncertain what the acronym SNAP meant (Participants 5 and 8), as they commented, “The acronym SNAP. People might not know what SNAP means” (Participant 5), and “It doesn’t tell me what SNAP food benefits is about. I’d like it to give me a little bit more of something” (Participant 8). The need for a more comprehensive description of SNAP benefits was a frequent point of emphasis in participant responses to this interview question.

The seventh and final interview question asked participants, “What are your overall thoughts on the message that I just discussed with you?” Three participants shared thoughts that centered on SNAP (Participants 4, 7, and 10). One participant mentioned, “It takes me a minute to get to the SNAP food part. I almost wonder if it’s even the spacing. Like, if it’s as simple as that, just spacing it out more, but it took me a second read to understand that, okay, the overall goal is to understand that, yes, there are SNAP food benefits offered” (Participant 7). Two participants highlighted the need to clarify what SNAP is and why it is beneficial, saying, “I’m not sure what SNAP is” (Participant 4), and “The message is clear and concise and simple, but I could just see again where there may need to be more clarity for the SNAP benefits” (Participant 10). Again, the need for more information about SNAP was the most frequent theme that arose in participant responses.

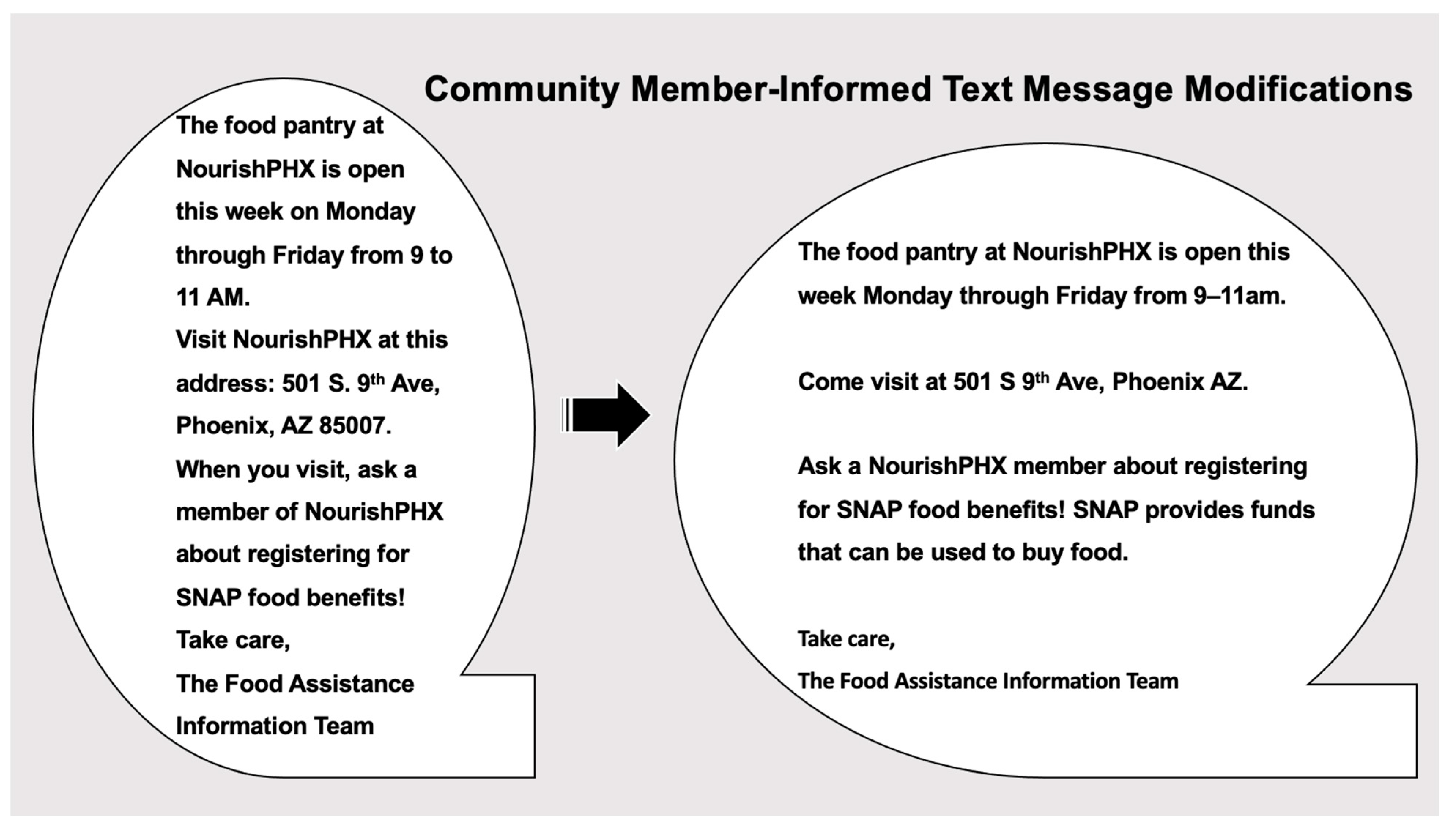

The 10 community members who were interviewed to test the text message to be used as an informational nudge in the intervention shared favorable opinions about the message and provided useful suggestions for improving it. These suggestions informed necessary modifications to produce the following finalized message: “The NourishPHX food pantry is open this week Monday through Friday from 9–11 a.m. Come visit at 501 S 9th Ave, Phoenix, AZ. Ask a NourishPHX member about registering for SNAP food benefits! SNAP provides funds that can be used to buy food. Take care, The Food Assistance Information Team”. Changes to the original message included a brief explanation detailing the benefits of SNAP and additional spacing by inserting a blank row in between each sentence of the message (

Figure 1). The text message was then used as an informational nudge for a food insecurity intervention among food pantry clients in Phase 2 of the study.

4. Discussion

This first phase of a feasibility study was conducted by composing, testing, and modifying a text message that was to be used as an informational nudge in a novel food insecurity intervention. The informational nudge is geared toward promoting food security by aiming to remove informational barriers that were potentially preventing individuals who were food insecure from accessing healthy food. This research added to the growing collection of food insecurity interventions that have been designed to eliminate barriers to accessing healthy food among individuals who are food insecure. Food insecurity interventions have seldom targeted the removal of information barriers, while a limited number of known studies have used informational nudges to promote basic needs security [

35,

36].

Basic needs security differs from food insecurity in encompassing consistent access to not only food but also shelter, clothing, utilities, childcare, finances, and physical safety [

49]. Since informational nudges that were used in previous basic needs insecurity interventions have yielded increased rates of accessing resource center services [

35] and emergency aid [

36], it is plausible that similar outcomes could be achieved in a food insecurity intervention that is crafted to increase utilization rates of food assistance resources. Despite most basic needs security studies having been conducted among college students, a similar method of using informational nudges to promote food security via targeting messaging could be transferrable from one food insecure population (i.e., college students) to another (i.e., food pantry clients).

Testing the informational nudge intervention through one-on-one interviews with community members was a useful method for modifying the text message in an effort to optimize its efficacy and acceptability among an eventual target population of food pantry clients. By testing the original conceptualization of the informational nudge in the first phase of this research study, unique interpretations and viewpoints of the text message that were communicated by community member interviewees shed light on aspects of the message that needed to be improved through specific alterations. As has been done using the same questions in past food security research [

46], obtaining the perspectives of local community members regarding the informational nudge text message used in this food insecurity intervention was a vital step in appropriately tailoring the message to the eventual recipients of the message who were also members of the community.

Informational nudge testing participants perceived that the message was trying to convey to recipients the availability of food assistance resources in their community, which aligned with the intended purpose of the text message. Responses from several participants emphasized the need to provide more details about what SNAP food benefits entail. The high frequency of feedback regarding the need for more details about SNAP benefits prompted modifications to the message that aimed to strike a balance between delivering a concise message that still had sufficient details about SNAP. Overall, participants liked various aspects of the message, including how the intention of the message was to help people in the community, how the message covered key information while remaining short and to the point, and how the message was worded in a friendly manner. These positive remarks were considered when modifying the text message to retain the favorable aspects of the message. When questioned about anything that participants disliked about the message, concerns resurfaced about them not knowing what SNAP is and how the message was not adequately spaced in its initial format. These voiced concerns strengthened the case for enhancing the text message by better explaining SNAP benefits and integrating more spacing in the message format.

Important modifications were made to improve the message by providing a brief explanation clarifying the general benefits of SNAP and editing the format of the message to make it concise and more spaced out. Integrating community-based participation in the creative process of constructing the informational nudge used in this study was a critical step in the process of delivering a text message-based food insecurity intervention to food pantry clients in the community. Similar to past community-based research efforts [

50], it was important to account for the cultural values, social norms, and lived experiences of individuals residing in the same community as the study location so that this intervention component could undergo necessary modifications to be well received by individuals from the same community as the interviewees.

Strengths and Limitations

This study contained a few notable strengths in its design and implementation. First, this research addressed a critical knowledge gap through qualitative research methods that allowed for an accumulation of community member input pertaining to the establishment of a novel food insecurity intervention using targeted text messages as informational nudges. Second, this study performed a novel application of informational nudges in a study focusing on food insecurity, as no other known study had used informational nudges to exclusively promote food security. Third, although the participant sample size was small, the sampled participants were racially diverse, as a majority of interview respondents were non-White. Having a racially diverse participant sample provided important and informative context to the interview responses given by participants with unique perspectives from various backgrounds.

This study also possessed several limitations. First, the participant sample for this study consisted of only 10 participants. This first study phase comprised the initial research activities of a two-phase feasibility study. It was decided that the recruitment of a small sample of research participants was most appropriate for this study phase to prevent wasting resources, as this was a feasibility study to assess a novel intervention for which there was no certain benefit. The sample size being restricted to 10 participants could have resulted in qualitative themes going undetected that otherwise would have been detected if a larger sample of participants were interviewed. However, the negative impact of having a small study sample was lesser since this study was qualitative by design and did not require a certain sample size to be adequately powered. Second, this research excluded all individuals who were not fluent in English by way of the participant inclusion criteria. Since the focus of this study was the development of a text message that would be acceptable to use as an informational nudge among U.S. adults, it was necessary for the message to be in a language that most U.S. adults could read and comprehend. That said, an English language informational nudge cannot be used among U.S. adults who are food insecure and are not fluent in English, which may diminish the impact of the intervention by excluding vulnerable people groups due to their lack of English language fluency. Third, the participant sample that was recruited for this study phase was largely Asian or White, and all but one participant had a college education. This lack of racial/ethnic and education diversity may have resulted in interview responses being captured that were not representative of individuals who are more likely to experience food insecurity, as individuals who are BIPOC and have less than a college education are at a greater risk of experiencing food insecurity [

18,

51]. Given this limitation, there is a chance that certain improvements to the text message were not applied due to a lack of representation across racial/ethnic and educational groups. Fourth, text message-based informational nudges require recipients to have regular access to a mobile phone that can receive text messages, which prevents some of the most vulnerable individuals experiencing the most severe cases of food insecurity from eventually being nudged toward accessing available food assistance. Despite a large proportion of the U.S. adult population having access to a cell phone, those who are suffering from the most extreme forms of economic hardship and food insecurity are unlikely to be able to afford a mobile phone, let alone a monthly cellphone plan that includes text messaging. Fifth, there was potential for experimenter expectancy bias and social desirability bias, as the participants may have responded to the interview questions and prompts in accordance with what they interpreted to be a desirable or socially acceptable answer. Efforts to minimize experimenter expectancy bias and social desirability bias included having the interviewer maintain consistency between each interview by only asking and stating what was on the interview script.