Healing Anthropocene Syndrome: Planetary Health Requires Remediation of the Toxic Post-Truth Environment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Term Post-Truth

3. Developmental Origins of the Post-Truth Era (DOPE)

“Public credulity seems to be the mark of our age. We’re ready to swallow anything shown on television, whether it has any basis in fact or not…when people are searching for a name for the age we live in, they sometimes call it the Age of Anxiety. How about…the Age of Fraudulence?”Barbara W. Tuchman, 1988 [35].

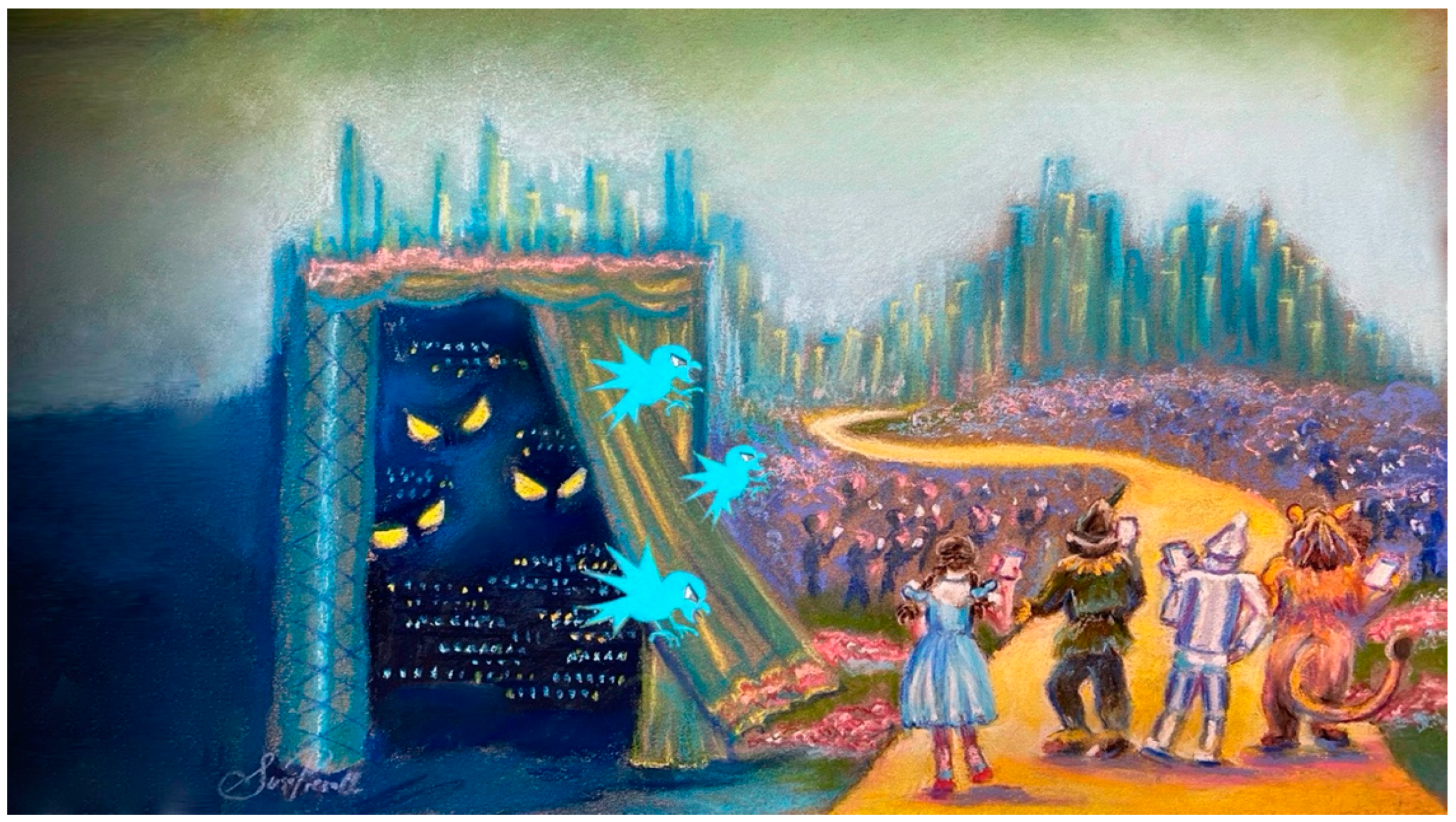

“Post-truth is pre-fascism...when we give up on truth, we concede power to those with the wealth and charisma to create spectacle in its place...if we lose the institutions that produce facts that are pertinent to us, then we tend to wallow in attractive abstractions and fictions. Truth defends itself particularly poorly when there is not very much of it around: [Social media] supercharges the mental habits by which we seek emotional stimulation and comfort, which means losing the distinction between what feels true and what actually is true”wrote Professor Timothy Snyder, recently, in the New York Times, on the social climate of 2021 [78].

4. Contagion of Misinformation

5. Marketing—Upstream in the Anthropocene

“The traditional [American] method of Advertisement suggests a credulity, a love of sensation and an absence of background in the submissive, hypnotized public...but that method is now in universal use...the world in which Advertisement dwells is a one-day world. It is necessarily a plane world without depth”Wyndham Lewis, Time and Western Man. 1927 [91]

“By using [some] accurate details to imply a misleading picture of the whole, the artful propagandist makes truth the principle form of falsehood”Christopher Lasch. The Culture of Narcissism. 1979.

“By what right do a self-selected group of druggists, biscuit makers, and computer designers become the architects of the new world?... Marketing is now recognized as the science of needs creation”Scholars Richard J. Barnet and Ronald E. Muller in Global Reach. 1974 [93].

6. Finding Solutions—Education, Empowerment

“If you are working to improve public health and the environment, you need to know what your opponents are up to”Professor Rob Moodie, 2017 [110].

- Bandwagon: Create the illusion that everybody—your neighbors, your fellow citizens, your colleagues and contemporaries—is agreeing with/doing/seeing/loving “it”.

- Card Stacking (aka Cherry Picking): careful selection of the best (or the worst) facts, figures, quotations and comments while eliding those that conflict with the message or prove it to be untrue; provide letters of support, such as “Fifty leading experts have signed support...”, while, in reality, far greater numbers of more suitable experts have provided consensus on the subject.

- GlitteringGenerality: the use of familiar, likeable words (referred to as “virtue words”) that key emotions—e.g., “freedom”, “justice”, “prosperity” and “heritage”.

- NameCalling: giving something or someone a bad name (e.g., smears). The aim is to cause dislike or ridicule of the subject without depth of analysis or query.

- PlainFolks: The messenger is positioned as standing eye-to-eye with “the people” and their needs; the messenger aims to be seen as simply voicing his/her own thoughts back to them; the messenger is “one of them” and not an outsider.

- Testimonial: direct use (or indirect via quotation) of well-known figures or a presumably trusted source to elevate the message; alternatively, use the name of, or quote a disgraced or nefarious person or outfit in a manipulative way so as to cause the reader/listener/viewer to think that not supporting the endgame is, by default, egregious.

- Transfer: associate the communication with revered and trusted symbols and/or institutions in order to transfer a level of respect to the message; the symbols of science are often co-opted for this purpose.

- AttackLegitimate Science: To achieve this aim, many of the seven devices of propaganda are used, including cherry-picking of less reliable but conveniently conflicting research, name-calling by labeling high-quality research as “junk”, and creating uncertainty by referring to complexity of causation and funding researchers sympathetic to the corporate cause.

- Attackand Intimidate Scientists: To achieve this aim, name-calling and smears against researchers/institutes is the primary tactic; Plain Folk is also used, as scientists are painted as out-of-touch elites; the words of Glittering Generality are used to attack evidence-based public health policies—”nanny state”, “attack on our freedoms”, etc.

- CreateArms-Length Front Organizations: According to the 1939 definition, the heart of propaganda is often the concealed individual or group; front organizations utilize all seven of the primary propaganda devices and engage in what Moodie calls “information laundering”; front groups often employ Transfer, effectively utilizing the trusted symbols of science. For example, the front organization, which might be financed by a soft drink lobby group, takes on the appearance of a group concerned with nutrition and produces materials that suggest junk food/drinks “are all part of a balanced diet”. Front groups also engage in “astroturfing”—well-funded “movements” that appear to be grassroots, community-driven efforts supportive of the propaganda message [118].

- Manufacture False Debate and Insist on Balance: Divert attention away from unhealthy products by ginning up controversy and debate; focus on corporate “social responsibility” efforts—for example, promoting a community “fitness campaign” while the corporation’s primary business is serving up calorie-dense, nutrient-poor ultra-processed foods; pressure journalists to continuously provide the “other side” viewpoint, even though volumes of evidence indicate there is little in the way of debatable points.

- Frame Key Issues in Highly Creative Ways: Here the skills of propagandists are employed on a large scale; fundamentally this is diversion, a tactic that runs the gamut from using creative imagery to diminish the seriousness of health problems in question; provide an optimistic outlook that technological advances (e.g., a phone app rather than regulation or policy changes) and new product innovation will provide solutions; focus exclusively on personal responsibility.

- FundIndustry Disinformation Campaigns: Here there is intentional introduction of falsehoods through various channels; often this activity occurs via the primary propaganda device Testimonial. Advertising abounds with compensated pitchpersons who may or not be celebrities—teeth made six shades whiter, or pillow provided the best sleep, are the more obvious variants; less obvious are compensated “expert” witnesses and “scientific” gatherings promoting a targeted, often commercial agenda [119].

- Influencethe Political Agenda: This is the arena in which propagandists often intersect; since propaganda is used within spheres of politics and product, campaign donations and heavy investments in lobbying efforts can help get a seat at the policy table with the long-game of adjusting policy, maintaining self-regulation/low oversight and crafting the messages surrounding policy efforts.

“The blocking of one’s capacity for wonder and the loss of the capacity to appreciate mystery can have serious effects upon our psychological health, not to mention the health of our whole planet”Rollo May, PhD. 1992 [124]

7. Positive Social Contagion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benatar, S. Politics, Power, Poverty and Global Health: Systems and Frames. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2016, 5, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCoy, D. Critical Global Health: Responding to Poverty, Inequality and Climate Change Comment on “Politics, Power, Poverty and Global Health: Systems and Frames”. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2017, 6, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bowles, J.; Larreguy, H.; Liu, S. Countering misinformation via WhatsApp: Preliminary evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserman, H.; Madrid-Morales, D. An Exploratory Study of “Fake News” and Media Trust in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. Afr. J. Stud. 2019, 40, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.M.; Yousuf, M.; Shatil Alam, A.; Saha, P.; Ishtiaque Ahmed, S.; Hassan, N. Combating Misinformation in Bangladesh: Roles and Responsibilities as Perceived by Journalists, Fact-checkers, and Users. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2020, 130, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyunjin, S.; Thorson, S.; Blomberg, M.; Appling, S.; Bras, A.; Davis-Roberts, A.; Altschwager, D. Country Characteristics, Internet Connectivity and Combating Misinformation: A Network Analysis of Global North-South. In Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2021; pp. 2966–2975. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/70975 (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Valenzuela, S.; Halpern, D.; Katz, J.E.; Miranda, J.P. The Paradox of Participation Versus Misinformation: Social Media, Political Engagement, and the Spread of Misinformation. Digit. J. 2019, 7, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Rose, C.M.; Buszkiewicz, J.; Ko, L.K.; Mou, J.; Cook, A.; Aggarwal, A.; Drewnowski, A. Characterising percentage energy from ultra-processed foods by participant demographics, diet quality and diet cost: Findings from the Seattle Obesity Study (SOS) III. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.; Hofman, K.; Moubarac, J.C.; Thow, A.M. Public health response to ultra-processed food and drinks. BMJ 2020, 369, m2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrinis, G. Ultra-processed foods and the corporate capture of nutrition-an essay by Gyorgy Scrinis. BMJ 2020, 371, m4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, U.O. The Global South Facing the Challenges of an Engendered, Sustainable and Peaceful Transition in a Hothouse Earth. In Earth at Risk in the 21st Century: Rethinking Peace, Environment, Gender, and Human, Water, Health, Food, Energy Security, and Migration; Spring, U.O., Ed.; Pioneers in Arts, Humanities, Science, Engineering, Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, L. Mean Girl: Ayn Rand and the Culture of Greed; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, T. Evidence mounts on the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L.; Wegienka, G.; Logan, A.C.; Katz, D.L. Dysbiotic drift and biopsychosocial medicine: How the microbiome links personal, public and planetary health. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2018, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamer, M.; Kivimaki, M.; Gale, C.R.; Batty, G.D. Lifestyle risk factors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19 hospitalization: A community-based cohort study of 387,109 adults in UK. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smirmaul, B.P.C.; Chamon, R.F.; de Moraes, F.M.; Rozin, G.; Moreira, A.S.B.; de Almeida, R.; Guimarães, S.T. Lifestyle Medicine During (and After) the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, A.C. Dysbiotic drift: Mental health, environmental grey space, and microbiota. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2015, 34, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loef, M.; Walach, H. The combined effects of healthy lifestyle behaviors on all cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World health statistics 2020: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332070/9789240005105-eng.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Pullar, J.; Allen, L.; Townsend, N.; Williams, J.; Foster, C.; Roberts, N.; Rayner, M.; Mikkelsen, B.; Branca, F.; Wickramasinghe, K. The impact of poverty reduction and development interventions on non-communicable diseases and their behavioural risk factors in low and lower-middle income countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguilera, R. The best medicine? RSA J. 2020, 165, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Belanger, M.J.; Hill, M.A.; Angelidi, A.M.; Dalamaga, M.; Sowers, J.R.; Mantzoros, C.S. Covid-19 and Disparities in Nutrition and Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, W.D. The Century Dictionary: An Encyclopedic Lexicon of the English Language; The Century Company: New York, NY, USA, 1899; Volume 7, p. 4774. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H. Meanings of propaganda. In Propaganda! The War for Men’s Minds; Klein, H., Ed.; Los Angeles City College Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1939; pp. 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Machiavelli, N. The Prince. Unabridged Edition; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Postman, N. Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business; Penguin Books: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tesich, S. A Government of Lies. Nation 1992, 1, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, R. The Post-Truth Era: Dishonesty and Deception in Contemporary Life; St Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries Post-Truth (Adjective). Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/post-truth (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Higgins, K. Post-truth: A guide for the perplexed. Nature 2016, 28, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.W.; Lee, E.J.; Shin, S.Y. What Debunking of Misinformation Does and Doesn’t. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Who falls for fake news? The roles of bullshit receptivity, overclaiming, familiarity, and analytic thinking. J. Pers. 2020, 88, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinberg, N.; Joseph, K.; Friedland, L.; Swire-Thompson, B.; Lazer, D. Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 US presidential election. Science 2019, 363, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, S.L.; Logan, A.C. Narrative Medicine Meets Planetary Health: Mindsets Matter in the Anthropocene. Challenges 2019, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sachs, S. Historian Admonishes Modern Novelists in Address to Librarians; The Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1988; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- McKernon, E. Fake news and the public. Harper’s 1925, 151, 528–536. [Google Scholar]

- Harper’s Magazine Foundation. Sell the papers! Harper’s 1925, 151, 1–9.

- Goldsmith, B. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol; Harcourt: San Diego, CA, USA, 1975; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, J.M. Why Americans Hate the Media and How It Matters; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, S.; Lelkes, Y.; Levendusky, M.; Malhotra, N.; Westwood, S.J. The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2019, 22, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Honeycutt, N.; Prislin, R.; Sherman, R.A. More Polarized but More Independent: Political Party Identification and Ideological Self-Categorization Among U.S. Adults, College Students, and Late Adolescents, 1970–2015. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 42, 1364–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brenan, M.B. Americans’ Trust in Mass Media Edges Down to 41%. Gallup Social Survey. 2019. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/267047/americans-trust-mass-media-edges-down.aspx (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Boorstin, D.J. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America; Harper Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. Post-truth and science. Lancet 2017, 389, 497–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosz, C. Nobel Lecture, 8 December 1980. Georgia Rev. 1995, 49, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Weisman, S.R. Reagan Misstatements Getting Less Attention. New York Times Magazine, 15 February 1983; 20. [Google Scholar]

- Engstron, J. Supermarket specials—Addict makes pilgrimage to unreal world of tabloids. Calgary Herald (Calgary, AB, Canada), 10 June 1984; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, D.J. Technological Media, from Message to Metaphor: An Essay Review of Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. J. Thought 1987, 22, 58–60. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, S.L. A butterfly flaps its wings: Extinction of biological experience and the origins of allergy. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 125, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohoe, M. Corporate Front Groups and the Abuse of Science. Z Magazine, October 2007; 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, A.C.; Prescott, S.L. Astrofood, priorities and pandemics: Reflections of an ultra-processed breakfast program and contemporary dysbiotic drift. Challenges 2017, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKee, M.; Diethelm, P. Reading between the Lines How the growth of denialism undermines public health. Br. Med. J. 2010, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M. Internet addiction: A new disorder enters the medical lexicon. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1996, 154, 1882–1883. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, A.C.; Selhub, E.M. Vis Medicatrix naturae: Does nature “minister to the mind”? Biopsychosoc. Med. 2012, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brashier, N.M.; Marsh, E.J. Judging Truth. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2020, 71, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hasher, L.; Goldstein, D.; Topinno, T. Frequency and the conference of referential validity. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1977, 16, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.T.; Krull, D.S.; Malone, P.S. Unbelieving the Unbelievable—Some Problems in the Rejection of False Information. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.T. How Mental Systems Believe. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, E.; Nass, C.; Wagner, A.D. Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 15583–15587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baumgartner, S.E.; van der Schuur, W.A.; Lemmens, J.S.; te Poel, F. The Relationship Between Media Multitasking and Attention Problems in Adolescents: Results of Two Longitudinal Studies. Hum. Commun. Res. 2018, 44, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanbonmatsu, D.M.; Strayer, D.L.; Medeiros-Ward, N.; Watson, J.M. Who Multi-Tasks and Why? Multi-Tasking Ability, Perceived Multi-Tasking Ability, Impulsivity, and Sensation Seeking. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.T.; Tafarodi, R.W.; Malone, P.S. You can’t not believe everything you read. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D.; Tice, D.M. The strength model of self-control. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rayport, J.F. Advertising’s New Medium: Human Experience. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 76–82, 84, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, M.R.; Ahn, R.J.; Ferguson, G.M.; Anderson, A. Consumer exposure to food and beverage advertising out of home: An exploratory case study in Jamaica. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Freeman, B.; King, L.; Chapman, K.; Baur, L.A.; Gill, T. The normative power of food promotions: Australian children’s attachments to unhealthy food brands. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2940–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Norman, J.; Kelly, B.; Boyland, E.; McMahon, A.T. The Impact of Marketing and Advertising on Food Behaviours: Evaluating the Evidence for a Causal Relationship. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2016, 5, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buchanan, L.; Kelly, B.; Yeatman, H. Exposure to digital marketing enhances young adults’ interest in energy drinks: An exploratory investigation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delobelle, P. Big Tobacco, Alcohol, and Food and NCDs in LMICs: An Inconvenient Truth and Call to Action Comment on “Addressing NCDs: Challenges from Industry Market Promotion and Interferences”. Int. J. Health Policy 2019, 8, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangcharoensathien, V.; Chandrasiri, O.; Kunpeuk, W.; Markchang, K.; Pangkariya, N. Addressing NCDs: Challenges from Industry Market Promotion and Interferences. Int. J. Health Policy 2019, 8, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, M. Health professionals must uphold truth and human rights. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, S.L. Medicine, public health and the populist radical right. J. R. Soc. Med. 2017, 110, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.K.H.; Seifert, C.M.; Schwarz, N.; Cook, J. Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychol. Sci. Publ. Int. 2012, 13, 106–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Newman, E.; Leach, W. Making the truth stick & the myths fade: Lessons from cognitive psychology. Behav. Sci. 2016, 2, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert, C.M. The continued influence of misinformation in memory: What makes a correction effective? Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 2002, 41, 265–292. [Google Scholar]

- Hopf, H.; Krief, A.; Mehta, G.; Matlin, S.A. Fake science and the knowledge crisis: Ignorance can be fatal. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 190161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nichols, T. The Death of Expertise; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, T. The American Abyss. New York Times Magazine, 9 January 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/09/magazine/trump-coup.html(accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandoc, E.C.; Jenkins, J.; Craft, S. Fake News as a Critical Incident in Journalism. J. Pract. 2019, 13, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, E.; Ramsay, N.; Kantner, J.; Pezdek, K.; Abed, E. Nonprobative Photos Increase Truth, Like, and Share Judgments in a Simulated Social Media Environment. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2019, 8, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, E.J.; Zhang, L. Truthiness: How non-probative photos shape belief. In The Psychology of Fake News Accepting, Sharing, and Correcting Misinformation; Greifeneder, R., Jaffe, M., Newman, E., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 90–114. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, E.J.; Garry, M.; Bernstein, D.M.; Kantner, J.; Lindsay, D.S. Nonprobative photographs (or words) inflate truthiness. Psychon. B Rev. 2012, 19, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chakraborty, A.; Paranjape, B.; Kakarla, S.; Ganguly, N. Stop Clickbait: Detecting and Preventing Clickbaits in Online News Media. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining Asonam, San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–21 August 2016; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rashidian, N.; Brown, P.; Hansen, E.; Bell, E.; Albright, J.; Hartstone, A. Friend and Foe: The Platform Press at the Heart of Journalism; Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Faiq, M.A.; Pandey, S.N.; Pareek, V.; Mochan, S.; Kumar, P.; Dantham, S.; Raza, K. Addictive Influences and Stress Propensity in Heavy Internet Users: A Proposition for Information Overload Mediated Neuropsychiatric Dysfunction. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2017, 13, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.K.M.N.; Islam, M.N.; Whelan, E. What drives unverified information sharing and cyberchondria during the COVID-19 pandemic? Eur. J. Inform. Syst. 2020, 29, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; McPhetres, J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Lu, J.G.; Rand, D.G. Fighting COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media: Experimental Evidence for a Scalable Accuracy-Nudge Intervention. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bago, B.; Rand, D.G.; Pennycook, G. Fake News, Fast and Slow: Deliberation Reduces Belief in False (but Not True) News Headlines. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2020, 149, 1608–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition 2019, 188, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, W. Time and Western Man; Chatto and Windus: London, UK, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, S.E.; Zimmerman, F.J.; Adler, G.J. Increasing public support for food-industry related, obesity prevention policies: The role of a taste-engineering frame and contextualized values. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 156, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barnet, R.; Muller, R. Global Reach; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lasch, C. The Culture of Narcissism; Warner Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ewen, S. Captains of Consciousness: Advertizing and the Roots of Consumer Culture; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.A. Endangered childhoods: How consumerism is impacting child and youth identity. Media Cult. Soc. 2011, 33, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K Kelly, B.; Boyland, E.; King, L.; Bauman, A.; Chapman, K.; Hughes, C. Children’s Exposure to Television Food Advertising Contributes to Strong Brand Attachments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Healt 2019, 16, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fritz, A.M. “Buy everything”: The model consumer-citizen of Disney’s Zootopia. J. Child. Media 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazijn, B. “Planet of the Humans” Documentary of Jeff Gibbs and Michael Moore: Who’s Afraid of Vandana Shiva? Available online: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/8676580 (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Blumenthal, M. ‘Green’ billionaires Behind Professional Activist Network that Led Suppression of ‘Planet of the Humans’ Documentary. The Grayzone, 7 September 2020. Available online: https://thegrayzone.com/2020/09/07/green-billionaires-planet-of-the-humans/(accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Yenneti, K.; Day, R. Procedural (in)justice in the implementation of solar energy: The case of Charanaka solar park, Gujarat, India. Energy Policy 2015, 86, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, R.; Birkenholtz, T. The sun and the scythe: Energy dispossessions and the agrarian question of labor in solar parks. J. Peasant Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, R.; Birkenholtz, T. Photons vs. firewood: Female (dis)empowerment by solar power in India. Gender Place Cult. 2020, 27, 1628–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swim, J.K.; Clayton, S.; Howard, G.S. Human Behavioral Contributions to Climate Change Psychological and Contextual Drivers. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moloney, K. Rethinking Public Relations; Routledge Pubishing: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M.A.; Wilkie, J.E.B.; Kim, J.K.; Bodenhausen, G.V. Cuing Consumerism: Situational Materialism Undermines Personal and Social Well-Being. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittmar, H.; Bond, R.; Hurst, M.; Kasser, T. The Relationship Between Materialism and Personal Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 107, 879–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gu, D.; Gao, S.Q.; Wang, R.; Jiang, J.; Xu, Y. The Negative Associations Between Materialism and Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: Individual and Regional Evidence from China. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 611–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Kasser, T. Generational Changes in Materialism and Work Centrality, 1976-2007: Associations with Temporal Changes in Societal Insecurity and Materialistic Role Modeling. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B 2013, 39, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moodie, A.R. What Public Health Practitioners Need to Know About Unhealthy Industry Tactics. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 1047–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Immunizing the public against misinformation. World Health Organization Newsroom, 25 August 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/immunizing-the-public-against-misinformation(accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Shao, C.C.; Ciampaglia, G.L.; Varol, O.; Yang, K.C.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F. The spread of low-credibility content by social bots. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pennycook, G.; Bear, A.; Collins, E.T.; Rand, D.G. The Implied Truth Effect: Attaching Warnings to a Subset of Fake News Headlines Increases Perceived Accuracy of Headlines Without Warnings. Manag. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cantril, H. Propaganda analysis. English J. 1938, 27, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Lee, E. The Fine Art of Propaganda; Harcourt Brace: New York, NY, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, K.; Zain-ul-Abdin, K. Post-truth propaganda: Heuristic processing of political fake news on Facebook during the 2016 US presidential election. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. A perspective on judgment and choice—Mapping bounded rationality. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 697–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, C.W. The roots of astroturfing. Contexts 2010, 9, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hiltzik, M. Exposed: The chemical Industry’s Fake Grassroots Lobbying for Fire Retardants. Los Angeles Times, 15 May 2015. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-mh-a-look-inside-the-chemical-industry-20150515-column.html(accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Collier, R.M. The Effect of Propaganda upon Attitude Following a Critical Examination of the Propaganda Itself. J. Soc. Psychol. 1944, 20, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, W.W. An experiment in teaching resistance to propaganda. J. Exp. Educ. 1939, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, S.; Roozenbeek, J. Psychological inoculation against fake news. In The Psychology of Fake News Accepting, Sharing, and Correcting Misinformation; Greifeneder, R., Jaffé, M.E., Newman, E.J., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.R. Some comments on propaganda analysis and the science of democracy. Public. Opin. Quart. 1941, 5, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R. The Loss of Wonder. In Dialogues: Therapeutic Applications of Existential Philosophy. Publication of students of the California School of Professional Psychology, Berkeley/Alameda campus). 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Edward_Mendelowitz/publication/297709628_The_Mystery_of_Being/links/56e1f28808ae3328e076b282/The-Mystery-of-Being.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition Emotion 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, V.E.; Datta, S.; Roy, A.R.K.; Sible, I.J.; Kosik, E.L.; Veziris, C.R.; Chow, T.E.; Morris, N.A.; Neuhaus, J.; Kramer, J.H.; et al. Big smile, small self: Awe walks promote prosocial positive emotions in older adults. Emotion 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcangeli, M.; Sperduti, M.; Jacquot, A.; Piolino, P.; Dokic, J. Awe and the Experience of the Sublime: A Complex Relationship. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, M.; Vohs, K.D.; Aaker, J. Awe Expands People’s Perception of Time, Alters Decision Making, and Enhances Well-Being. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiota, M.N.; Keltner, D.; Mossman, A. The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition Emotion 2007, 21, 944–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cappellen, P.; Saroglou, V. Awe Activates Religious and Spiritual Feelings and Behavioral Intentions. Psychol. Relig. Spirit 2012, 4, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stellar, J.E.; John-Henderson, N.; Anderson, C.L.; Gordon, A.M.; McNeil, G.D.; Keltner, D. Positive Affect and Markers of Inflammation: Discrete Positive Emotions Predict Lower Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines. Emotion 2015, 15, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, K.J. Awe: More than a lab experience—A rejoinder to “Awe: ‘More than a feeling’” by Alice Chirico and Andrea Gaggioli. Humanistic Psychol. 2020, 48, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.J. The Depolarizing of America. A Guidebook for Social Healing; University Professors Press: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, J.M.; Laux, L.F.; Lorimor, R.; Thornby, J.I.; Vallbona, C. Authoritarianism′s role in medicine. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1995, 310, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kashima, Y.; Fernando, J. Utopia and ideology in cultural dynamics. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2020, 34, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, J.W.; O’Brien, L.V.; Burden, N.J.; Judge, M.; Kashima, Y. Greens or space invaders: Prominent utopian themes and effects on social change motivation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 50, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, V.; Miller, S.J.; Dunne, L. Increasing the Advertising Literacy of Primary School Children in Ireland: Findings from a Pilot RCT. Int. J. Digital Soc. 2019, 10, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J.; Yeager, D.S.; Hinojosa, C.P.; Chabot, A.; Bergen, H.; Kawamura, M.; Steubing, F. Harnessing adolescent values to motivate healthier eating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10830–10835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, B.; Molina, Y.; Viswanath, K.; Warnecke, R.; Prelip, M.L. Strategies to Empower Communities to Reduce Health Disparities. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1424–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, C.J.; Yeager, D.S.; Hinojosa, C.P. A values-alignment intervention protects adolescents from the effects of food marketing. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, H.; Scully, M.; Wakefield, M.; Kelly, B.; Pettigrew, S.; Chapman, K.; Niederdeppe, J. Can counter-advertising protect spectators of elite sport against the influence of unhealthy food and beverage sponsorship? A naturalistic trial. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 266, 113415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noone, C.; Bunting, B.; Hogan, J. Does Mindfulness Enhance Critical Thinking? Evidence for the Mediating Effects of Executive Functioning in the Relationship between Mindfulness and Critical Thinking. Front. Psychol. 2016, 6, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burgess, D.J.; Beach, M.C.; Saha, S. Mindfulness practice: A promising approach to reducing the effects of clinician implicit bias on patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanter, J.W.; Rosen, D.C.; Manbeck, K.E.; Branstetter, H.M.L.; Kuczynski, A.M.; Corey, M.D.; Maitland, D.W.M.; Williams, M.T. Addressing microaggressions in racially charged patient-provider interactions: A pilot randomized trial. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstin, L.H. Inoculation against propaganda. Clearing House 1949, 23, 432. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R.V.; Bradac, J.J.; Barnhart, S.A.; Kraft, E. The effect of learning about techniques of propaganda on subsequent reaction to propagandistic communications. Speech Teach. 1970, 19, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.J. Some contemporary approaches (persuasion inoculation). Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1964, 1, 191–229. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, A.M.; Miller, C.H. Inoculation message treatments for curbing non-communicable disease development. Rev. Panam. Salud. Publica 2013, 34, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Palmedo, P.C.; Dorfman, L.; Garza, S.; Murphy, E.; Freudenberg, N. Countermarketing Alcohol and Unhealthy Food: An Effective Strategy for Preventing Noncommunicable Diseases? Lessons from Tobacco. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2017, 38, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chittamuru, D.; Daniels, R.; Sarkar, U.; Schillinger, D. Evaluating values-based message frames for type 2 diabetes prevention among Facebook audiences: Divergent values or common ground? Patient Educ. Counsel. 2020, 103, 2420–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.N.; Bond, C. A preregistered replication of “Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change”. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, J.Y.D.; Zhang, J.W. Feeling angry: The effects of vaccine misinformation and refutational messages on negative emotions and vaccination attitude. J. Health Commun. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compton, J.; Jackson, B.; Dimmock, J.A. Persuading Others to Avoid Persuasion: Inoculation Theory and Resistant Health Attitudes. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McGuire, W.J.; Papageorgis, D. The relative efficacy of various types of prior belief-defense in producing immunity against persuasion. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1961, 62, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, W.J. The Effectiveness of Supportive and Refutational Defenses in Immunizing and Restoring Beliefs Against Persuasion. Sociometry 1961, 24, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szybillo, G.J.; Heslin, R. Resistance to Persuasion—Inoculation Theory in a Marketing Context. J. Marketing Res. 1973, 10, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banas, J.A.; Rains, S.A. A Meta-Analysis of Research on Inoculation Theory. Commun. Monogr. 2010, 77, 281–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, J. Prophylactic versus therapeutic inoculation treatments for resistance to influence. Commun. Theory 2020, 30, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, A.C.; Berman, S.H.; Berman, B.M.; Prescott, S.L. Project Earthrise: Inspiring Creativity, Kindness and Imagination in Planetary Health. Challenges 2020, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Cantu, S.M.; van Vugt, M. The Evolutionary Bases for Sustainable Behavior: Implications for Marketing, Policy, and Social Entrepreneurship. J. Public Policy Mark. 2012, 31, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M.; Schultz, P.W.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. Normative social influence is underdetected. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B 2008, 34, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christakis, N.A.; Fowler, J.H. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fowler, J.H.; Christakis, N.A. Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: Longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2008, 337, a2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moreno, M.A.; Christakis, D.A.; Egan, K.G.; Jelenchick, L.A.; Cox, E.; Young, H.; Villiard, H.; Becker, T. A Pilot Evaluation of Associations Between Displayed Depression References on Facebook and Self-reported Depression Using a Clinical Scale. J. Behav. Health Ser. R 2012, 39, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, A.L.; Lawrence, S.A.; Troth, A.C.; Jordan, P.J. Group affective tone: A review and future research directions. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, S43–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitta, L.; Probst, T.M.; Ghezzi, V.; Barbaranelli, C. Economic stress, emotional contagion and safety outcomes: A cross-country study. Work 2020, 66, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Christakis, N.A.; Fowler, J.H. Dueling biological and social contagions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christakis, N.A.; Fowler, J.H. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2249–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Klepper, M.; Sleebos, E.; van de Bunt, G.; Agneessens, F. Similarity in friendship networks: Selection or influence? The effect of constraining contexts and non-visible individual attributes. Soc. Netw. 2010, 32, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T.; Kiuru, N.; Degol, J.L.; Salmela-Aro, K. Friends, academic achievement, and school engagement during adolescence: A social network approach to peer influence and selection effects. Learn. Instr. 2018, 58, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Christakis, N.A. Network multipliers and public health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1032–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christakis, N.A.; Fowler, J.H. Social contagion theory: Examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Stat. Med. 2013, 32, 556–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Busic-Sontic, A.; Fuerst, F. Does your personality shape your reaction to your neighbours’ behaviour? A spatial study of the diffusion of solar panels. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prescott, S.L.; Logan, A.C. Each meal matters in the exposome: Biological and community considerations in fast-food-socioeconomic associations. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2017, 27, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissell, P.; Peacock, M.; Holdsworth, M.; Powell, K.; Wilcox, J.; Clonan, A. Introducing the idea of “assumed shared food narratives” in the context of social networks: Reflections from a qualitative study conducted in Nottingham, England. Sociol. Health Ill 2018, 40, 1142–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.D.I.; Guillory, J.E.; Hancock, J.T. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8788–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coviello, L.; Sohn, Y.; Kramer, A.D.I.; Marlow, C.; Franceschetti, M.; Christakis, N.A.; Fowler, J.H. Detecting Emotional Contagion in Massive Social Networks. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Finkenauer, C.; Vohs, K.D. Bad is Stronger than Good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razran, G.H.S. Conditioned response changes in rating and appraising sociopolitical slogans. Psychol. Bull. 1940, 37, 481. [Google Scholar]

- Forgas, J.P. Happy Believers and Sad Skeptics? Affective Influences on Gullibility. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 28, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.; Forestell, C.A. Mindfulness, Mood, and Food: The Mediating Role of Positive Affect. Appetite 2020, 158, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberts, H.J.E.M.; Otgaar, H.; Kalagi, J. Minding the source: The impact of mindfulness on source monitoring. Legal Criminol. Psychol. 2017, 22, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, G.; Weinschenk, A. Something Real about Fake News: The Role of Polarization and Social Media Mindfulness. In Proceedings of the Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS), Online, 10–14 August 2020; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2020/social_computing/social_computing/8/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Sebastião, L.V. The Effects of Mindfulness and Meditation on Fake News Credibility. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2019. Available online: https://www.lume.ufrgs.br/handle/10183/197895 (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Poon, K.T.; Jiang, Y.F. Getting Less Likes on Social Media: Mindfulness Ameliorates the Detrimental Effects of Feeling Left Out Online. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabielkov, M.; Ramachandran, A.; Chaintreau, A.; Legout, A. Social Clicks: What and Who Gets Read on Twitter? In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMETRICS/IFIP Performance, Antibes Juan-les-Pins, France, 14–18 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Houli, D.; Radford, M. An exploratory study using mindfulness meditation apps to buffer workplace technostress and information overload. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomantonio, M.; De Cristofaro, V.; Panno, A.; Pellegrini, V.; Salvati, M.; Leone, L. The mindful way out of materialism: Mindfulness mediates the association between regulatory modes and materialism. Curr. Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Z.; Liu, L.; Tan, X.Y.; Zheng, W.W. The moderating effect of dispositional mindfulness on the relationship between materialism and mental health. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2017, 107, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandra, T.K. Achieving triple dividend through mindfulness: More sustainable consumption, less unsustainable consumption and more life satisfaction. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 161, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.; Dube, E.; Driedger, M. Vaccine Hesitancy: In Search of the Risk Communication Comfort Zone. PLoS Curr. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J.; Richey, S.; Freed, G.L. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: A randomized trial. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e835–e842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jimenez, A.V.; Stubbersfield, J.M.; Tehrani, J.J. An experimental investigation into the transmission of antivax attitudes using a fictional health controversy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 215, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.A.; Hwong, A.R.; Stafford, D.; Hughes, D.A.; O’Malley, A.J.; Fowler, J.H.; Christakis, N.A. Social network targeting to maximise population behaviour change: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bristow, J. Mindfulness in politics and public policy. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hall, N. The Kardashian index: A measure of discrepant social media profile for scientists. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zenger, B.; Swink, J.M.; Turner, J.L.; Bunch, T.J.; Ryan, J.J.; Shah, R.U.; Turakhia, M.P.; Piccini, J.P.; Steinberg, B.A. Social media influence does not reflect scholarly or clinical activity in real life. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2020, 13, e008847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, G.R. Before the Kardashian Index. Science 2014, 346, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcik, S.; Hughes, A. Sizing up Twitter users. Pew Research Center, 24 April 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/04/24/sizing-up-twitter-users/(accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Benatar, S.; Upshur, R.; Gill, S. Understanding the relationship between ethics, neoliberalism and power as a step towards improving the health of people and our planet. Anthropocene Rev. 2018, 5, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencucha, R.; Thow, A.M. How Neoliberalism Is Shaping the Supply of Unhealthy Commodities and What This Means for NCD Prevention. Int. J. Health Policy 2019, 8, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sweet, E. “Like you failed at life”: Debt, health and neoliberal subjectivity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 212, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, M.; Gough, B.; Wearing, S.; Deville, A. Social Psychology, Consumer Culture and Neoliberal Political Economy. J. Theor. Soc. Behav. 2017, 47, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bucy EP, N.J. Fake news finds an audience. In Journalism and Truth; Katz, J.E., Mays, K.K., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, E.N. Can public service broadcasting survive Silicon Valley? Synthesizing leadership perspectives at the BBC, PBS, NPR, CPB and local U.S. stations. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonbely, S.; Weber, M.S.; Satullo, C. Innovation in Public Funding for Local Journalism: A Case Study of New Jersey’s 2018 Civic Information Bill. Digit. J. 2020, 8, 740–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croco, S.E.; McDoanld, J.; Turitto, C. Making them pay: Using the norm of honesty to generate costs for political lies. Electoral Stud. 2021, 69, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimpel, C.; Von Scheidt, C.; Jose, G.; Sonntag, U.; Stefano, G.B.; Michalsen, A.; Esch, T. Changes and Interactions of Flourishing, Mindfulness, Sense of Coherence, and Quality of Life in Patients of a Mind-Body Medicine Outpatient Clinic. Forsch. Komplementmed. 2014, 21, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, S.K.; Alexander, M.; Torres, M.; Irwin, M.R.; Christakis, N.A.; Nishi, A. Mindfulness Meditation Activates Altruism. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Logan, A.C.; Berman, S.H.; Berman, B.M.; Prescott, S.L. Healing Anthropocene Syndrome: Planetary Health Requires Remediation of the Toxic Post-Truth Environment. Challenges 2021, 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe12010001

Logan AC, Berman SH, Berman BM, Prescott SL. Healing Anthropocene Syndrome: Planetary Health Requires Remediation of the Toxic Post-Truth Environment. Challenges. 2021; 12(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe12010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleLogan, Alan C., Susan H. Berman, Brian M. Berman, and Susan L. Prescott. 2021. "Healing Anthropocene Syndrome: Planetary Health Requires Remediation of the Toxic Post-Truth Environment" Challenges 12, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe12010001

APA StyleLogan, A. C., Berman, S. H., Berman, B. M., & Prescott, S. L. (2021). Healing Anthropocene Syndrome: Planetary Health Requires Remediation of the Toxic Post-Truth Environment. Challenges, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe12010001