Addressing the Environmental, Community, and Health Impacts of Resource Development: Challenges across Scales, Sectors, and Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Context

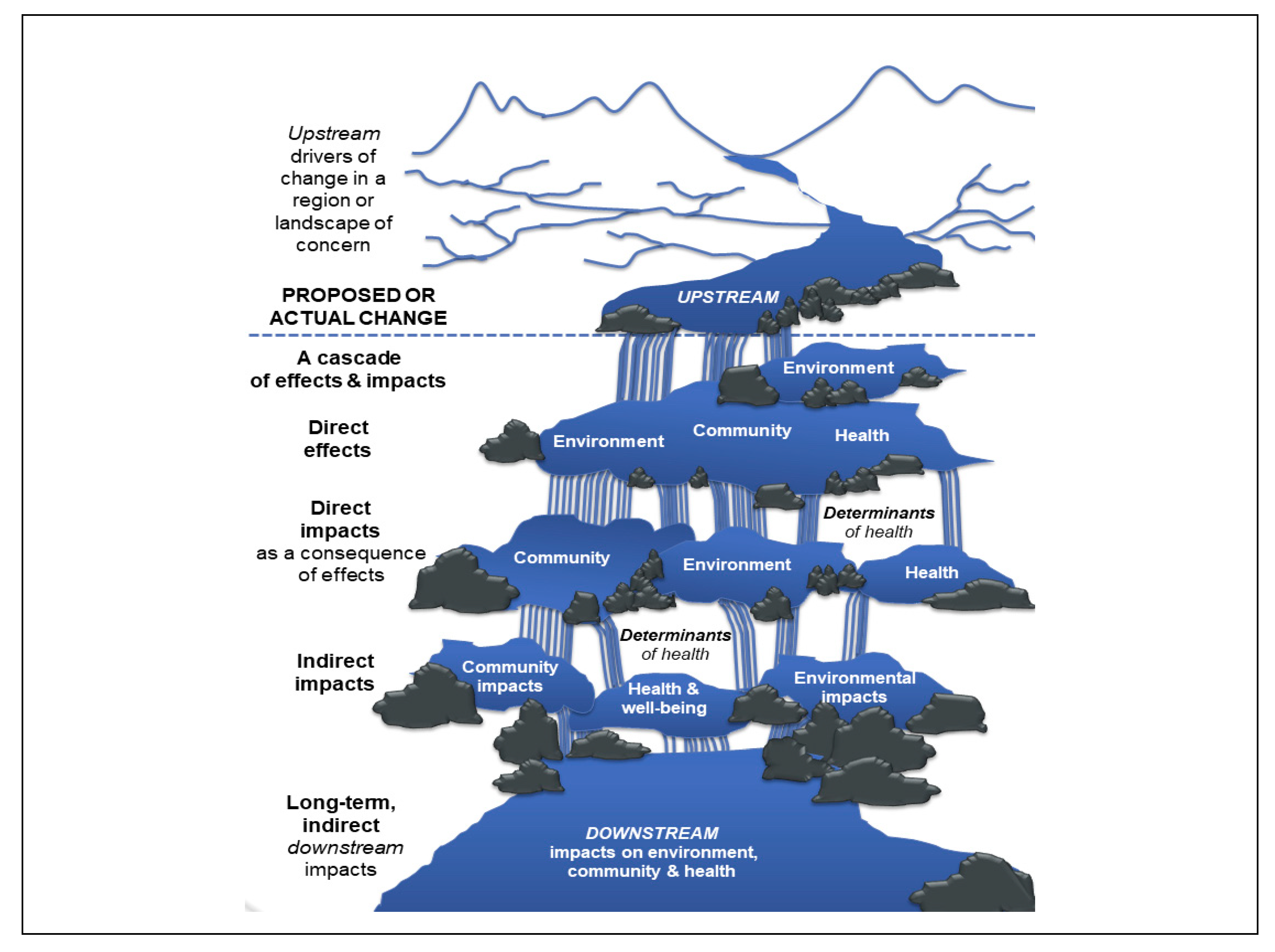

2.1. Cumulative Thinking, Resource Development, and Health

“… a commitment to conceptualizing the full range of spatial and temporal scales as well as impacts that occur as a result of human-caused changes to coupled social–ecological systems. A cumulative thinking perspective demands recognition that impacts are not just environmental, they are not just large development projects, and they are not all easily identified and quantified. Furthermore, past experience tells us to expect interactions”[24], p. 222.

2.2. Canadian Responses to Planetary Dilemmas: Assessments, Observatories, Intersectoral Prevention

“Trends demonstrate that Canada ranks low amongst peer countries on the environment and risks falling further behind. The 2013 Conference Board of Canada Report Card on the Environment showed that Canada ranked 15th (among 17 peer countries) on fourteen indicators including air quality; water quality and quantity; biodiversity and conservation; climate change and natural resource management”.[15]

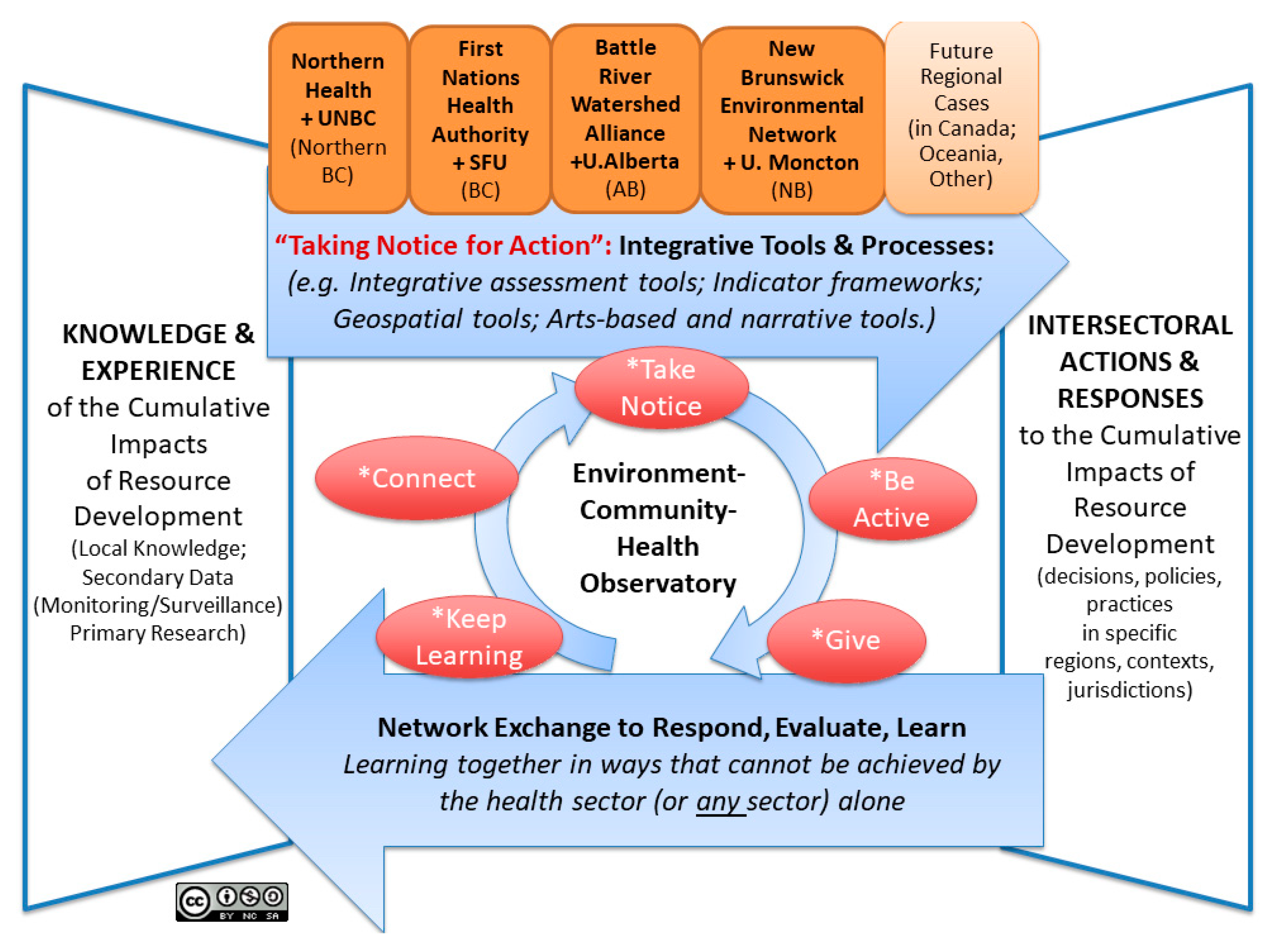

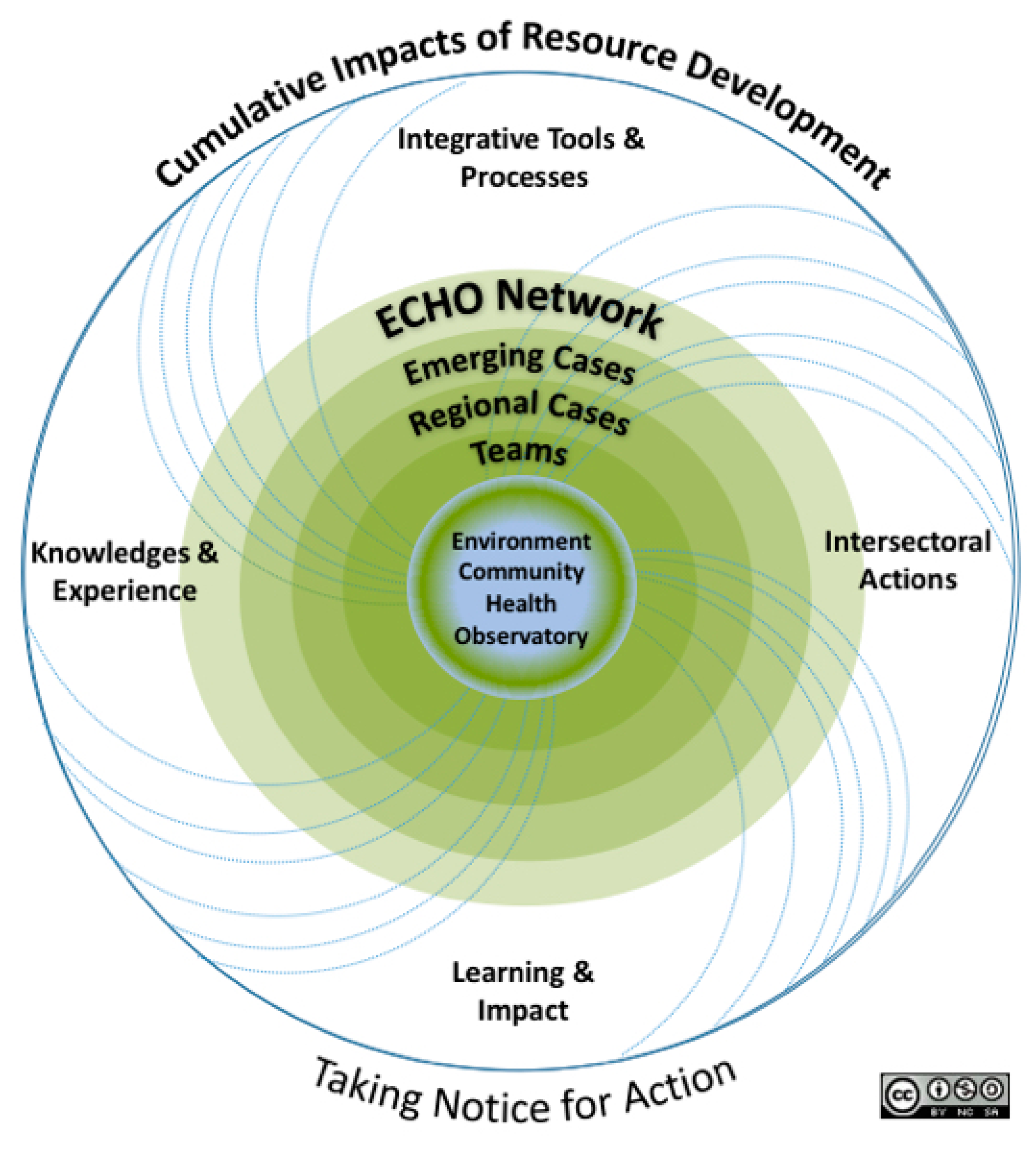

3. Approach: Influences on Research Design, the ECHO Framework, and Governance

3.1. Methodological Influences and Intersectoral Prevention Research

3.2. The ECHO Network Framework

- To make evidence-based recommendations on the form and function of a cross-jurisdictional ECHO, consisting of a suite of tools and processes designed to improve integrative understanding of and responses to the cumulative impacts of resource development and health.

- To inform, enable, empower, and evaluate intersectoral strategies to address the cumulative determinants of health impacts arising from resource development by targeting actions and responses that cannot be achieved by the health sector alone.

3.3. Foundations for Learning and Exchange: Regional Cases and ECHO Network Governance

4. Discussion: Emerging Insights from Working across Scales, Sectors, and Sites

4.1. Working with Scale

4.2. The Hidden and the Obvious

4.3. “Staying with the Trouble”

5. Concluding Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brisbois, B.W.; Reschny, J.; Fyfe, T.M.; Harder, H.G.; Parkes, M.W.; Allison, S.; Buse, C.G.; Fumerton, R.; Oke, B. Mapping research on resource extraction and health: A scoping review. Extract. Ind. Soc. 2018, 6, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrecker, T.; Birn, A.-E.; Aguilera, M. How extractive industries affect health: Political economy underpinnings and pathways. Health Place 2018, 52, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, S.L.; Logan, A.C. Larger Than Life: Injecting Hope into the Planetary Health Paradigm. Challenges 2018, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliano, M. Planetary Health: Are We Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution? Challenges 2018, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, C.G.; Oestreicher, J.S.; Ellis, N.R.; Patrick, R.; Brisbois, B.; Jenkins, A.P.; McKellar, K.; Kingsley, J.; Gislason, M.; Galway, L.; et al. Public health guide to field developments linking ecosystems, environments and health in the Anthropocene. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2018, 72, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkes, M.W.; Morrison, K.E.; Bunch, M.J.; Hallström, L.K.; Neudoerffer, R.C.; Venema, H.D.; Waltner-Toews, D. Towards Integrated Governance for Water, Health and Social-Ecological Systems: The Watershed Governance Prism. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sula-Raxhimi, E.; Butzbach, C.; Brousselle, A. Planetary health: Countering commercial and corporate power. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e12–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessing, M.; Howlett, M.; Summerville, T. Canadian Natural Resource and Environmental Policy: Political Economy and Public Policy, 2nd ed.; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Halseth, G.R.; Gillingham, M.; Johnson, C.J.; Parkes, M.W. Cumulative Effects and Impacts: The Need for a More Inclusive, Integrative, Regional Approach. (Chapter 1). In The Integration Imperative: Cumulative Environmental, Community and Health Impacts of Multiple Natural Resource Developments; Gillingham, M.P., Halseth, G.R., Johnson, C.J., Parkes, M.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Chief Medical Officer of Health (OCMOH). Chief Medical Officer of Health’s Recommendations Concerning Shale Gas Development in New Brunswick; New Brunswick Department of Health: Fredericton, NB, Canada, 2012.

- Kinnear, S.; Kabir, Z.; Mann, J.; Bricknell, L. The Need to Measure and Manage the Cumulative Impacts of Resource Development on Public Health: An Australian Perspective. In Current Topics in Public Health; Rodriguez-Morales, A., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2013; Chapter 7; pp. 125–144. ISBN 978-953-51-1121-4. [Google Scholar]

- Teegee, T. Take Care of the Land and the Land Will Take Care of You: Resources, Development, and Health (Chapter 11). In Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ Health in Canada: Beyond the Social. Canadian Scholars Press; Greenwood, M., de Leeuw, S., Lindsay, N.M., Reading, C., Eds.; Canadian Scholars Press: Toronto, ON, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, M.W. Cumulative Determinants of Health Impacts in Rural, Remote, and Resource-Dependent Communities (Chapter 5). In The Integration Imperative: Cumulative Environmental, Community and Health Effects of Multiple Natural Resource Developments; Gillingham, P.M., Halseth, R.G., Johnson, J.C., Parkes, W.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 117–149. ISBN 978-3-319-22123-6. [Google Scholar]

- CIHR. Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Intersectoral Prevention Research Teams. Available online: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50310.html (accessed on 28 January 2019).

- CIHR. Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Environments and Health: Overview. Available online: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48465.html (accessed on 28 January 2019).

- ECHO Network/Réseau ECHO. About the ECHO Network. Available online: https://www.echonetwork-reseauecho.ca/about/ (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Oestreicher, J.S.; Buse, C.; Brisbois, B.; Patrick, R.; Jenkins, A.; Kingsley, J.; Távora, R.; Fatorelli, L. Where ecosystems, people and health meet: Academic traditions and emerging fields for research and practice. Sustentabilidade Debate 2018, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallström, L.K.; Guehlstorf, N.; Parkes, M.W. Convergence and Diversity: Integrating Encounters with Health, Ecological and Social Concerns. In Ecosystems, Society and Health: Pathways through Diversity, Convergence and Integration; Hallström, L.K., Guehlstorf, N.P., Parkes, M.W., Eds.; McGill Queens University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Healing the web of life: On the meaning of environmental and health equity. Int. J. Public Health 2018, 64, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salk, J.D. Planetary Health: A New Reality. Challenges 2019, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillingham, M.P.; Halseth, G.R.; Johnson, C.J.; Parkes, M.W. The Integration Imperative: Cumulative Environmental, Community and Health Impacts of Multiple Natural Resource Developments; Springer International Publishing AG: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- APSC. Tackling Wicked Problems: A Public Policy Perspective; Contemporary Government Challenges; Australian Public Services Commission, Australian Government: Sydney, Australia, 2007.

- Brown, V. Collective Decision-Making Bridging Public Health, Sustainability Governance and Environmental Management. In Sustaining Life on Earth: Environmental and Human Health through Global Governance; Soskolne, C., Westra, L., Kotzé, L.J., Mackey, B., Rees, W.E., Westra, R., Eds.; Lexington Books: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.J.; Gillingham, M.P.; Halseth, G.R.; Parkes, M.W. A Revolution in Strategy, Not Evolution of Practice: Towards an Integrative Regional Cumulative Impacts Framework (Chapter 8). In The Integration Imperative: Cumulative Environmental, Community and Health Effects of Multiple Natural Resource Developments; Gillingham, P.M., Halseth, R.G., Johnson, J.C., Parkes, W.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 217–242. ISBN 978-3-319-22123-6. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, M.W.; Johnson, C.J.; Halseth, G.R.; Gillingham, M.P. An Imperative for Change: Towards an Integrative Understanding (Chapter 7). In The Integration Imperative: Cumulative Environmental, Community and Health Effects of Multiple Natural Resource Developments; Gillingham, P.M., Halseth, R.G., Johnson, J.C., Parkes, W.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 193–216. ISBN 978-3-319-22123-6. [Google Scholar]

- CIRC Cumulative Impacts Research Consortium. What Are Cumulative Impacts? Available online: http://www.unbc.ca/cumulative-impacts/about-circ (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Stephens, C.; Willis, R.; Walker, G. Using Science to Create a Better Place. Addressing Environmental Inequalities: Cumulative Environmental Impacts. Science Report: SC020061/SR4; Environment Agency: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zinsstag, J.; Schelling, E.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Tannera, M. From “one medicine” to “one health” and systemic approaches to health and well-being. Prevent. Vet. Med. 2011, 101, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, P.; Finlayson, C.M. Wetlands as settings for human health: Incorporating ecosystem services and health impact assessment into wetland and water resource management. Bioscience 2011, 61, 678–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.E. Parks and Other Green Environments: Essential Components of a Healthy Human Habitat; National Recreation and Park Association: Ashburn, VR, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maller, C.; Henderson-Wilson, C.; Townsend, M. Rediscovering Nature in Everyday Settings: Or How to Create Healthy Environments and Healthy People. EcoHealth 2009, 6, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, C.G.; Smith, M.; Silva, D. Attending to scalar ethical issues in emerging approaches to environmental health research and practice. Monash Bioeth Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, B.; Aguirre, A.A.; Daszak, P.; Horwitz, P.; Martens, P.; Parkes, M.; Patz, J.; Waltner-Toews, D. EcoHealth: A Transdisciplinary Imperative for a Sustainable Future. EcoHealth 2004, 1, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, J.; Mergler, D.; Parkes, M.W.; Saint-Charles, J.; Spiegel, J.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Yassi, A.; Woollard, R.F. Tools for Thoughtful Action: The role of ecosystem approaches to health in enhancing public health. Can. J. Public Health 2010, 101, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Charron, D.F. Ecosystem Approaches to Health for a Global Sustainability Agenda. EcoHealth 2012, 9, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charron, D.F. Ecohealth Research in Practice: Innovative Applications of an Ecosystem Approach to Health; Springer: New York, NY, USA; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, M.W.; Horwitz, P. Ecology and Ecosystems as Foundational for Health. In Environmental Health: From Global to Local; Frumkin, H., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, C.; Burns, T.; Riviere-Cinnamond, A. Pragmatism (or Realism) in Research: Is There an Ecohealth Scope of Practice? EcoHealth 2016, 13, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, C.; Cooper, D.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Maiero, M.; Karesh, W.; Hunter, D.; Golden, C. (Eds.) Connecting Global Priorities: Biodiversity and Human Health, a State of Knowledge Review; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland; Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD): Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/health/SOK-biodiversity-en.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Horwitz, P.; Kretsch, C.; Jenkins, A.; Hamid, A.R.A.; Batal, M.; Burls, A.; Carter, M.; Henwood, W.; Lovell, R.; Lee, L.C.M.; Moewaka-Barnes, H.; Montenegro, R.A.; Parkes, M.W.; Patz, J.; Roe, J.J.; Sitthisuntikul, K.; Stephens, C.; Townsend, M.; Wright, P. Contribution of biodiversity and green spaces to mental and physical fitness, and cultural dimensions of health (Chapter 12). In Connecting Global Priorities: Biodiversity and Human Health, a State of Knowledge Review; Romanelli, C., Cooper, D., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Maiero, M., Karesh, W., Hunter, D., Golden, C., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; Convention on Biological Diversity: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/health/SOK-biodiversity-en.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Povall, S.L.; Haigh, F.A.; Abrahams, D.; Scott-Samuel, A. Health equity impact assessment. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picketts, I.M.; Parkes, M.W.; Déry, S.J. Climate change and resource development impacts in watersheds: Insights from the Nechako River Basin, Canada. Can. Geogr./Le Géographe Canadien 2016, 61, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroleum Services Association of Canada Industry Overview|PSAC. Available online: https://www.psac.ca/business/industry-overview/#upstream (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Hoogeveen, D. Fish-hood: Environmental assessment, critical Indigenous studies, and posthumanism at Fish Lake (Teztan Biny), Tsilhqot’in territory. Environ. Plan. D 2016, 34, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, N.; Gleeson, B. Chapter 6: Ecological Justice, Rethinking the bases. In Justice, Society, and Nature: An Exploration of Political Ecology; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-415-14516-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S. Ontologies of Indigeneity: The politics of embodying a concept. Cult. Geogr. 2014, 21, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, J. Decolonizing posthumanist geographies. Cult. Geogr. 2014, 21, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, Z. An Indigenous Feminist’s Take On The Ontological Turn: ‘Ontology’ Is Just Another Word For Colonialism. J. Hist. Sociol. 2016, 29, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, N. Cumulative Environmental, Community and Health Impacts of Multiple Natural Resource Developments in Northern British Columbia: Focus on First Nations. (Vignette 7, in Chapter 6). Exploring Cumulative Effects and Impacts Through Examples. In The Integration Imperative: Cumulative Environmental, Community and Health Impacts of Multiple Natural Resource Developments; Gillingham, M.P., Halseth, G.R., Johnson, C.J., Parkes, M.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 170–173. [Google Scholar]

- Harder, H.G. Mental Health and Well-Being Implications of Resource Development (Box 5.4). Cumulative Determinants of Health Impacts in Rural, Remote, and Resource-Dependent Communities (Chapter 5). In The Integration Imperative: Cumulative Environmental, Community and Health Impacts of Multiple Natural Resource Developments; Parkes, M.W., Gillingham, M.P., Halseth, G.R., Johnson, C.J., Parkes, M.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 139–141. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G.A.; Higginbotham, N.; Cashman, P.; Flint, K. Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Aust. Psychiatry 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunsolo Willox, A.; Harper, S.; Edge, V.; Landman, K.; Houle, K.; Ford, J. The Rigolet Inuit Community Government, The Land Enriches the Soul: On Environmental Change, Affect, and Emotional Health and Well-Being in Nunatsiavut, Canada. Emot. Space Soc. 2013, 6, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northern Health. Part 1: Understanding the State of Industrial Camps in Northern BC:A Background Paper; Northern Health: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Northern Health. Part 2: Understanding Resource and Community Development in Northern British Columbia: A Background Paper; Northern Health: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell-Foster, K.; Gislason, M.K. Lived Reality and Local Relevance: Complexity and Immediacy of Experienced Cumulative Long-Term Impacts. (Vignette 6, in Chapter 6). Exploring Cumulative Effects and Impacts Through Examples. In The Integration Imperative: Cumulative Environmental, Community and Health Impacts of Multiple Natural Resource Developments; Gillingham, M.P., Halseth, G.R., Johnson, C.J., Parkes, M.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Duinker, P.N.; Greig, L.A. The Impotence of Cumulative Effects Assessment in Canada: Ailments and Ideas for Redeployment. Environ. Manag. 2006, 37, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duinker, P.N.; Burbidge, E.L.; Boardley, S.R.; Greig, L.A. Scientific dimensions of cumulative effects assessment: Toward improvements in guidance for practice. Environ. Rev. 2012, 21, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Public Health Association. Global Change and Public Health: Addressing the Ecological Determinants of Health. CPHA Discussion Paper. May 2015; Canadian Public Health Association, Ed.; Canadian Public Health Association: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Northern Health. Chief Medical Health Officer’s Status Report on Child Health; Northern Health: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, C.; Hirsch Hadorn, G. Methodological challenges of transdisciplinary research. Nat. Sci. Soc. 2018, 16, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E.; Walker, G. Caution! Transitions Ahead: Politics, Practice, and Sustainable Transition Management. Environ. Plan. A 2007, 39, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M.; Somers, G.; Wilson, J.E.; Tanna, R.; Chung, C.; Duro, D.C.; Seitz, N. Scale, assessment components, and reference conditions: Issues for cumulative effects assessment in Canadian watersheds. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2013, 9, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, N.J.; Gregory, R.; Brooks, C.; Failing, L.; Satterfield, T. From invisibility to transparency: Identifying the implications. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, B.; Udofia, A. Protectors of the Land: Toward an EA Process that Works for Aboriginal Communities and Developers; MacDonald-Laurier Institute Publication: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shandro, J.A.; Jokinen, L.; Kerr, K.; Sam, A.M.; Scoble, M.; Ostry, A. Ten Steps Ahead: Community Health and Safety in the Nak’al Bun/Stuart Lake Region During the Construction Phase of the Mount Milligan Mine; University of Victoria, Norman B. Keevil Institute of Mining Engineering, Monkey Forest Social Performance Consulting, Fort St James DistricSt, Nak’azdli Band Council: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mahboubi, P.; Parkes, M.W.; Chan, H.M. Challenges and Opportunities of Integrating Human Health into the Environmental Assessment Process: The Canadian Experience Contextualised to International Efforts. J. Environ. Assmt. Pol. Mgmt. 2015, 17, 1550034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, L.C.; Ollson, C.A.; Stefanovic, I.L. Advancing the practice of health impact assessment in Canada: Obstacles and opportunities. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 55, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, P.; Parkes, M.W. Scoping Health Impact Assessment: Ecosystem services as a framing device. In Handbook on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in Impact Assessment; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northhampton, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 62–85. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, F.C. Cumulative effects assessment: Theoretical underpinnings and big problems. Environ. Rev. 2016, 24, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, M.K.; Morgan, V.S.; Mitchell-Foster, K.; Parkes, M.W. Voices from the landscape: Storytelling as emergent counter-narratives and collective action from northern BC watersheds. Health Place 2018, 54, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, P.; Neely, A.H. Triangulating health: Toward a practice of a political ecology of health. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 39, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada, Environment Canada. The 2012 Canadian Nature Survey: Awareness, Participation and Expenditures in Nature-Based Recreation, Conservation, and Subsistence Activities. Available online: http://biodivcanada.ca/2A0569A9-77BE-4E16-B2A4-C0A64C2B9843/2012_Canadian_Nature_Survey_Report%28accessible_opt%29.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- First Nations Health Authority; Northern Health. Northern First Nations Caucus Overview of Sub-regional Engagement Sessions. Health and Resource Development Impacts and Overview. Fall 2015 Summary Report. Available online: http://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-Northern-First-Nations-Caucus-Overview-Fall-2015-Summary-Report.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Northern Health. Health and Safety during the Opioid Overdose Emergency: Northern Health’s Recommendations for Industrial Camps; Northern Health: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Observatory WHO|Local Health Observatories. Available online: http://www.who.int/kobe_centre/measuring/urban_health_observatory/local_observatories/en/ (accessed on 17 June 2016).

- Hemmings, J.; Wilkinson, J. What is a public health observatory? J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2003, 57, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saskatoon Health Region. Evidence, Action, Equity: Making Population Health Information Count’ Saskatoon Health Region’s Public Health Observatory; Saskatoon Health Region: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. Public Health Observatories: Learning from Our World Neighbours; National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health: Antigonish, Nova Scotia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Provincial Health Services Authority BC Observatory for Population & Public Health. Available online: http://www.bccdc.ca/our-services/programs/bc-observatory-for-pop-public-health (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Parkes, M.; Panelli, R. Integrating Catchment Ecosystems and Community Health: The Value of Participatory Action Research. Ecosyst. Health 2001, 7, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, R.M.; Stephen, C.; Copes, R. Strategies for Collaboration in the Interdisciplinary Field of Emerging Zoonotic Diseases. Zoonoses Public Health 2012, 59, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, M.W. ‘Just Add Water’: Dissolving Barriers to Collaboration and Learning for Health, Ecosystems and Equity. In Ecosystems, Society and Health: Pathways through Diversity, Convergence and Integration; Hallström, L., Guehlstorf, N., Parkes, M.W., Eds.; McGill Queens University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015; pp. 184–222. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, M.W.; Bienen, L.; Breilh, J.; Hsu, L.-N.; McDonald, M.; Patz, J.A.; Rosenthal, J.P.; Sahani, M.; Sleigh, A.; Waltner-Toews, D.; et al. All Hands on Deck: Transdisciplinary Approaches to Emerging Infectious Disease. EcoHealth 2005, 2, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser Basin Council. Identifying Health Concerns Relating to Oil & Gas Development in Northeastern BC: Human Health Risk Assessment—Phase 1 Report; BC Ministry of Health: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2012.

- Potvin, L. Intersectoral action for health: More research is needed! Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CIHR. Canadian Instiutes for Health Research (CIHR) Intersectoral Prevention Research. Team Grant: Environments and Health. Available online: https://www.researchnet-recherchenet.ca/rnr16/vwOpprtntyDtls.do?prog=2283&view=currentOpps&org=CIHR&type=EXACT&resultCount=25&sort=program&all=1&masterList=true (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Brown, V.; Harris, J.A.; Russell, J.Y. Tackling Wicked Problems: Through the Trandisciplinary Imagination; Earthscan: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Best, A.; Holmes, B. Systems thinking, knowledge and action: Towards better models and methods. Evid. Policy A J. Res. Debate Pract. 2010, 6, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.; Graham, I.D. Integrated Knowledge Translation. In Knowledge Translation in Health Care: Moving from Evidence to Practice; Straus, S., Tetroe, J., Graham, I.D., Eds.; BMJ Books: West Sussez, UK, 2013; ISBN 1-118-41358-X. [Google Scholar]

- CIHR. Guide to Knowledge Translation Planning at CIHR: Integrated and End-of-Grant Approaches; Canadian Institutes for Health Research: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012.

- Lavis, J.N. Research, public policymaking, and knowledge-translation processes: Canadian efforts to build bridges. J. Cont. Educ. Health Prof. 2006, 26, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrizi, P.; Heid Thompson, E.; Coffman, J.; Beer, T. Eyes Wide Open: Learning as Strategy Under Conditions of Complexity and Uncertainty. Found. Rev. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, M.W.; Charron, D.; Sanchez, A. Better Together: Field-building Networks at the Frontiers of Ecohealth Research. In Ecohealth Research in Practice: Innovative Applications of an Ecosystem Approach to Health; Charron, D., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, V.A. Collective Inquiry and Its Wicked Problems. In Tackling Wicked Problems: Through the Trandsiciplinary Imagination; Brown, V.A., Harris, J., Russel, J., Eds.; Earthscan: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, F.; Saint-Charles, J.; Lucotte, M.; Mergler, D. Emergence and Robustness of a Community Discussion Network on Mercury Contamination and Health in the Brazilian Amazon. Health Educ. Behav. 2008, 35, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, R.; Röling, N.; Watson, D. Challenges to science and society in the sustainable management and use of water: Investigating the role of social learning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2007, 10, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, W.; Fenemor, A.; Kilvington, M.; Harmsworth, G.; Young, R.; Deans, N.; Horn, C.; Phillips, C.; Montes de Oca, O.; Ataria, J.; et al. Building collaboration and learning in integrated catchment management: The importance of social process and multiple engagement approaches. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2011, 45, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K.; FitzGibbon, J.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Hallström, L.K.; Guehlstorf, N.P.; Parkes, M.W. Situated Learning, Community Development, and Ciguatera Fish Poisoning in Cuban Fishing Villages. In Ecosystems, Society, and Health: Pathways through Diversity, Convergence, and Integration; McGill-Queens University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015; pp. 227–255. [Google Scholar]

- Gross Stein, J.; Stren, R.; Fitzgibbon, J.; MacLean, M. Networks of Knowledge: Collaborative Innovation in International Learning; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2001; ISBN 0802048447. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, J.; Ewers, R.M.; Anderson, L.; Aragao, L.E.O.C.; Baker, T.R.; Boyd, E.; Feldpausch, T.R.; Gloor, E.; Hall, A.; Malhi, Y.; et al. Using learning networks to understand complex systems: A case study of biological, geophysical and social research in the Amazon. Biol. Rev. 2011, 86, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKellar, K.A.; Pitzul, K.B.; Yi, J.Y.; Cole, D.C. Evaluating Communities of Practice and Knowledge Networks: A Systematic Scoping Review of Evaluation Frameworks. EcoHealth 2014, 11, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, J.W.; Takaro, T.K.; Song, L.; Weaver, M. The Seattle-King County Healthy Homes Project: A Randomized, Controlled Trial of a Community Health Worker Intervention to Decrease Exposure to Indoor Asthma Triggers. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woollard, R.F. Caring for a common future: Medical schools’ social accountability. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, K.; Parkes, M.; Ramasubramanian, L. Participatory Environmental Health Research in Aotearoa/New Zealand: Constraints and Opportunities. Health Educ Behav. 2000, 27, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaro, T.; Kreiger, J.; Song, L.; Sharify, D.; Beaudet, N. The Breathe-Easy Home: The impact of asthma-friendly home construction on clinical outcomes and trigger exposure. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkes, M.W.; Saint-Charles, J.; Cole, D.C.; Gislason, M.; Hicks, E.; Le Bourdais, C.; McKellar, K.; St-Cyr Bouchard, M.; Canadian Community of Practice in Ecosystem Approaches to Health Team. Strengthening collaborative capacity: Experiences from a short, intensive field course on ecosystems, health and society. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2016, 36, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, B.; Kothari, U. Participation: The New Tyranny? Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- De Leeuw, S.C.; Cameron, E.S.; Greenwood, M.L. Participatory and community-based research, Indigenous geographies, and the spaces of friendship: A critical engagement. Can. Geogr./Le Géographe Canadien 2012, 56, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C. What is progress in Transdisciplinary Research. Futures 2011, 43, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperrider, D.L.; Whitney, D. Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change. In The Change Handbook: The Definitive Resource on Today’s Best Methods for Engaging Whole Systems; Holman, P., Devane, T., Cady, S., Eds.; BK Publishers: Hatfield, Pretoria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkness, V.; Barnhardt, R. First Nations and higher education: The four R’s - respect, relevance, reciprocity, and responsibility. J. Am. Indian Educ. 1991, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oakes, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 1-4129-7517-4. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples; University of Otago Press: Dunedin, New Zealand, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S.; Smith, L.T. Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Leipert, B.D.; Reutter, L. Women’s health in northern British Columbia: The role of geography and gender. Can. J. Rural Med. 2005, 10, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Chasey, S.; Duff, P.; Pederson, A.P. Taking a Second Look: Analyzing Health Inequities in British Columbia with a Sex, Gender, and Diversity Lens; Provincial Health Services Authority: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Northern Health. Where Are the Men? Chief Medical Health Officer’s Report on the Health & Wellbeing of Men and Boys in Northern BC; Northern Health: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eckford, C.; Wagg, J. The Peace Project: Gender Based Analysis of Violence against Women and Girls in Fort St. John; Fort St John Women’s resoURCE Society: Fort St John, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gislason, M.K.; Buse, C.; Tosh, J.; Woollard, R.W.; Parkes, M.W. Women and Children in Resource Extracting Communities: An approach to understanding climate change, labour and health. In Gender, Climate Change and Work in Rich Countries; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Charles, J.; Rioux-Pelletier; Mongeau, P.; Mertens, F. Diffusion of environmental health information: the role of sex- and gender-differentiated pathways. In What a Difference Sex and Gender Make: A Gender, Sex and Health Research Casebook; Canadian Institutes of Health Research: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Developmental Evaluation. Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.C.; Parkes, M.W.; Saint-Charles, J.; Gislason, M.; McKellar, K.; Webb, J. Evolution of Capacity Strengthening: Insights from the Canadian Community of Practice in Ecosystem Approaches to Health. Transform. Dial. Teach. Learn. J. 2018, 11, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, S.; Aked, J. Five Ways to Wellbeing: New Applications, New Ways of Thinking; New Economics Foundation, Centre for Well-Being: London, UK, 2011; Available online: https://neweconomics.org/2011/07/five-ways-well-new-applications-new-ways-thinking (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Aked, J.; Marks, N.; Cordon, C.; Thompson, S. Five Ways to Wellbeing: The Evidence. A Report Presented to the Foresight Project on Communicating the Evidence Base for Improving People’s Well-Being; New Economics Foundation, Centre for Well-Being: London, UK, 2008; Available online: https://www.ids.ac.uk/publications/five-ways-to-wellbeing-the-evidence/ (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Buse, C.; Lai, V.; Cornish, K.; Parkes, M. Towards environmental health equity in health impact assessment: Innovations and opportunities. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraway, D. Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene. In Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 30–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, D.; Adger, W.N.; Berkes, F.; Garden, P.; Lebel, L.; Olsson, P.; Pritchard, L.; Young, O. Scale and Cross-Scale Dynamics: Governance and Information in a Multilevel World. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.P.; Leitner, H.; Marston, S.A.; Sheppard, E. Neil Smith’s Scale: Neil Smith’s Scale. Antipode 2017, 49, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, S.A. The social construction of scale. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, B. A New Biopolitics of Environmental Health: Permeable Bodies and the Anthropocene. In The SAGE Handbook of Nature: Three Volume Set; Marsden, T., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd: Thousand Oakes, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 216–230. [Google Scholar]

- Veltmeyer, H. The political economy of natural resource extraction: a new model or extractive imperialism? Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2013, 34, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRIP United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 2007. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Daigle, M. The spectacle of reconciliation: On (the) unsettling responsibilities to Indigenous peoples in the academy. Environ. Plan. D 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, E. Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, anniversary ed.; Monthly Review Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, L.; Desmeules, M. Les minorités linguistiques du Canada et la santé. Healthcare Policy/Politiques de Santé 2013, 9, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckley, T.M. New Brunswick. State of rural Canada 2015. 2015, pp. 53–56. Available online: http://sorc.crrf.ca/nb/ (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- Jenkins, A.; Capon, A.; Negin, J.; Marais, B.; Sorrell, T.; Parkes, M.; Horwitz, P. Watersheds in planetary health research and action. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e510–e511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisbois, B.W.; Delgado, A.B.; Barraza, D.; Betancourt, Ó.; Cole, D.; Gislason, M.; Mertens, F.; Parkes, M.; Saint-Charles, J. Ecosystem approaches to health and knowledge-to-action: Towards a political ecology of applied health-environment knowledge. J. Political Ecol. 2017, 24, 692–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbés-Blázquez, M.; Feagan, M.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Parkes, M. The need for heuristics in ecosystem approaches to health. EcoHealth 2014, 11, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Northern Health; Parkes, M.W.; LeBourdais, C.; Beck, L.; Paterson, J.; Rose, C.; Zirul, C.; Yarmish, K.; Chapman, R.C. Northern Health Position on the Environment as a Context for Health; Northern Health and the University of Northern British Columbia: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mollett, S.; Faria, C. The spatialities of intersectional thinking: Fashioning feminist geographic futures. Gender Place Cult. 2018, 25, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau, D. Roots, Rhizomes, Networks and Territories: Reimagining Pattern and Power in Political Ecologies; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 70–88. [Google Scholar]

- De Leeuw, S.; Parkes, M.W.; Sloan Morgan, V.; Christensen, J.; Nicole, L.; Mitchell Foster, K.; Russell Jozkow, J. Going Unscripted: A Call to Critically Engage Storytelling Methods and Methodologies in Geography and the Medical-Health Sciences. Can. Geogr./Le Géographe canadien 2017, 61, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L.; Logan, A.C. From Authoritarianism to Advocacy: Lifestyle-Driven, Socially-Transmitted Conditions Require a Transformation in Medical Training and Practice. Challenges 2018, 9, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parkes, M.W.; Allison, S.; Harder, H.G.; Hoogeveen, D.; Kutzner, D.; Aalhus, M.; Adams, E.; Beck, L.; Brisbois, B.; Buse, C.G.; et al. Addressing the Environmental, Community, and Health Impacts of Resource Development: Challenges across Scales, Sectors, and Sites. Challenges 2019, 10, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe10010022

Parkes MW, Allison S, Harder HG, Hoogeveen D, Kutzner D, Aalhus M, Adams E, Beck L, Brisbois B, Buse CG, et al. Addressing the Environmental, Community, and Health Impacts of Resource Development: Challenges across Scales, Sectors, and Sites. Challenges. 2019; 10(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe10010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleParkes, Margot W., Sandra Allison, Henry G. Harder, Dawn Hoogeveen, Diana Kutzner, Melissa Aalhus, Evan Adams, Lindsay Beck, Ben Brisbois, Chris G. Buse, and et al. 2019. "Addressing the Environmental, Community, and Health Impacts of Resource Development: Challenges across Scales, Sectors, and Sites" Challenges 10, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe10010022

APA StyleParkes, M. W., Allison, S., Harder, H. G., Hoogeveen, D., Kutzner, D., Aalhus, M., Adams, E., Beck, L., Brisbois, B., Buse, C. G., Chiasson, A., Cole, D. C., Dolan, S., Fauré, A., Fumerton, R., Gislason, M. K., Hadley, L., Hallström, L. K., Horwitz, P., ... Vaillancourt, C. (2019). Addressing the Environmental, Community, and Health Impacts of Resource Development: Challenges across Scales, Sectors, and Sites. Challenges, 10(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe10010022