Validation of the SpREUK—Religious Practices Questionnaire as a Measure of Christian Religious Practices in a General Population and in Religious Persons

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Aim of the Study

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Enrolled Persons

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Engagement in Religious Practices (SpREUK-P)

- Religious practices (alpha = 0.82), i.e., praying, church attendance, religious events, religious symbols

- Existentialistic practices (alpha = 0.77), i.e., self-realization, reflections upon the meaning of life, trying to gain insight (also into myself)

- Prosocial-humanistic practices (alpha = 0.79), i.e., helping others, considering their needs, doing good, thoughts to those in need

- Gratitude/Awe (alpha = 0.77), i.e., feeling of gratitude, reverence, experiencing the beauty in life

- Spiritual (mind body) practices (alpha = 0.72), i.e., meditation (Eastern style), rituals (“from other religious traditions than mine”), reading spiritual/religious books.

2.2.2. Transcendence Perception (DESES-6)

2.2.3. Franciscan-Inspired Spirituality Questionnaire (FraSpir)

2.2.4. Life Satisfaction (SWLS)

2.2.5. Well-Being Index (WHO-5)

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Reliability and Factor Analysis of the SpREUK-P in Its Variant Version

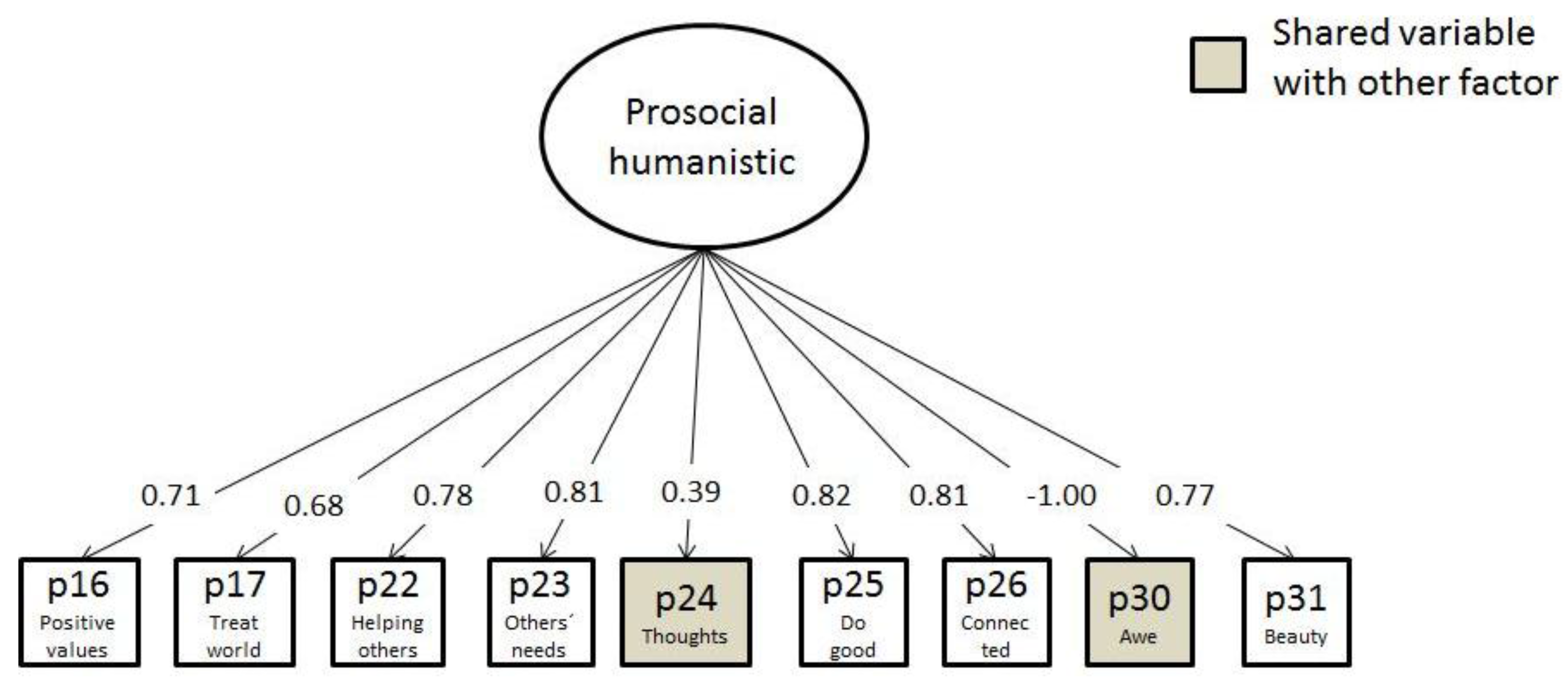

- The 8-item factor Prosocial-Humanistic practices (40% explained variance; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91) is comprised of five items from the primary “Prosocial-humanistic practices” scale, and items from other scales which all share the topic of conscious dealing with the world around and with others. The item p31 addressing the perception and the value of beauty in the world load on this factor, too.

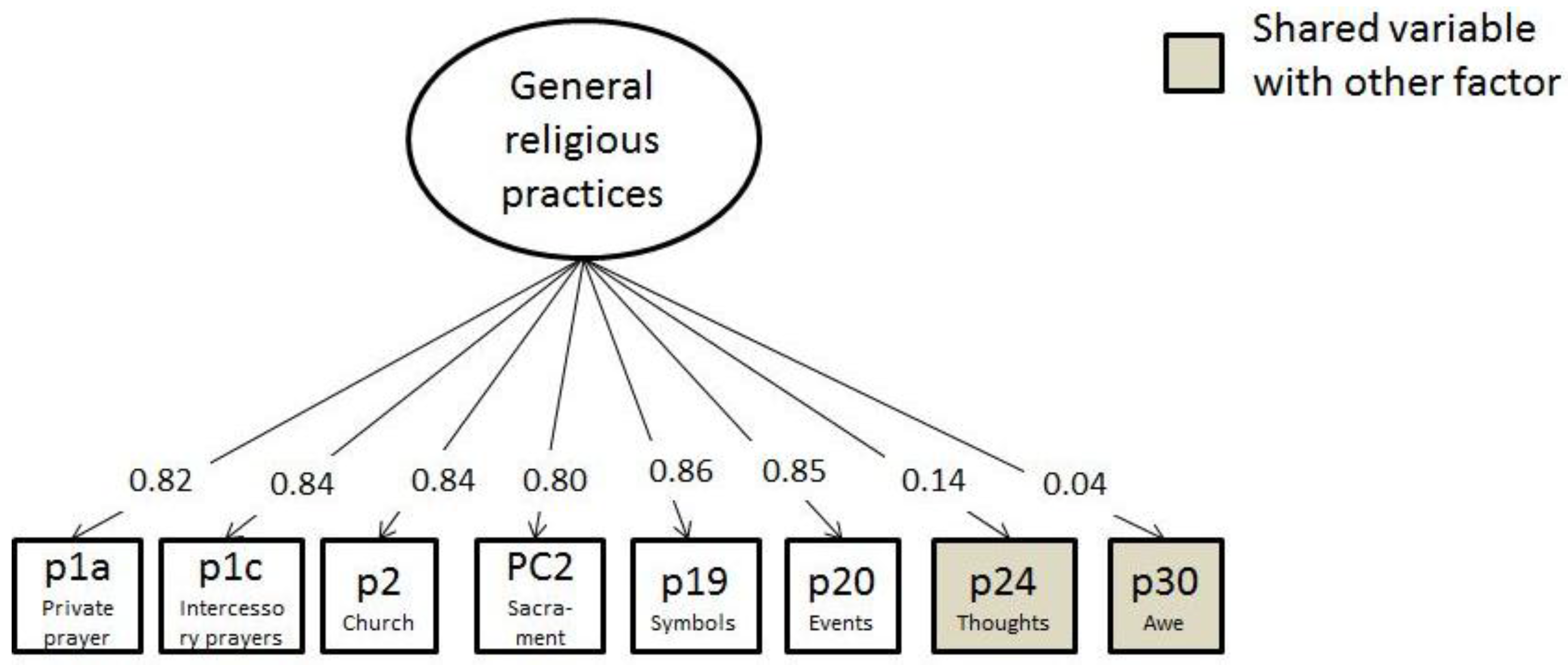

- The 6-item factor General religious practices (22% explained variance; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94) uses four items from the primary “Religious practices” scale and two new items.

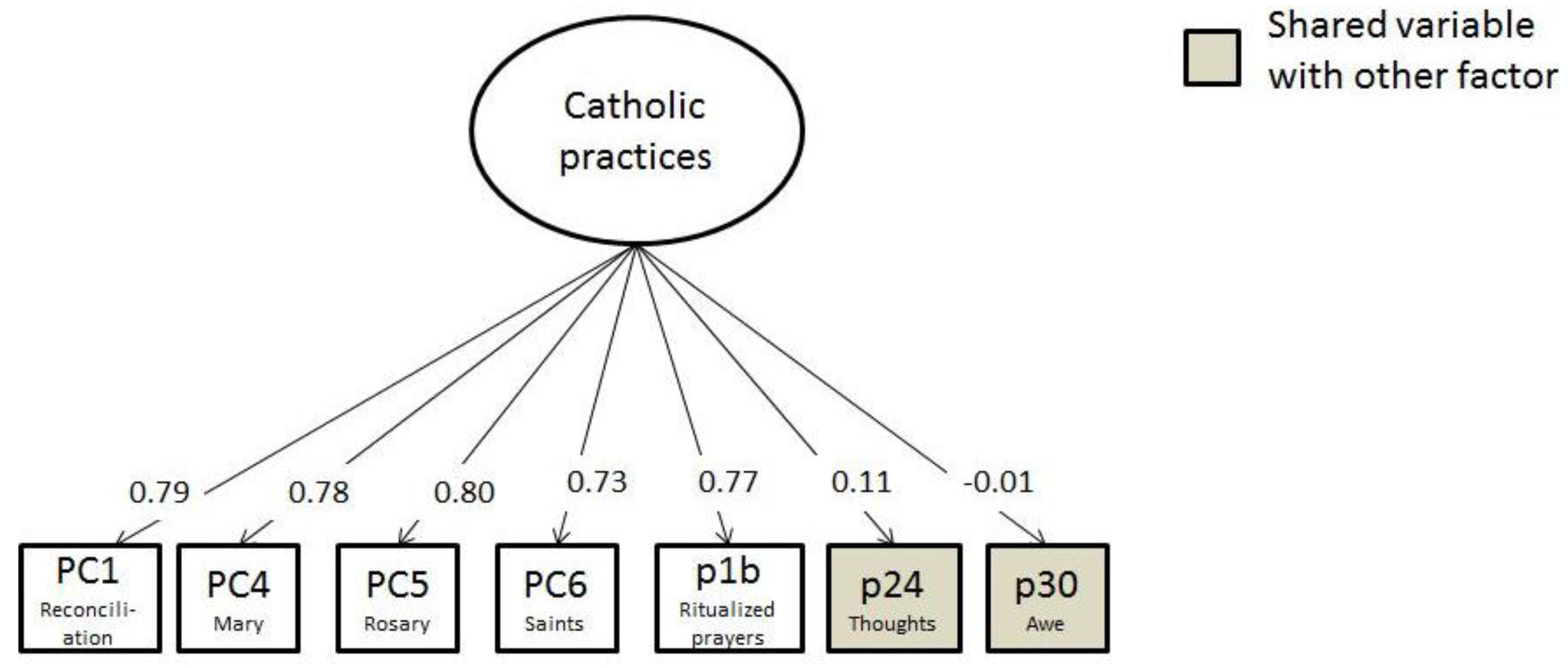

- The 5-item factor Catholic religious practices (5% explained variance; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90) is comprised of five ‘Catholic’ items.

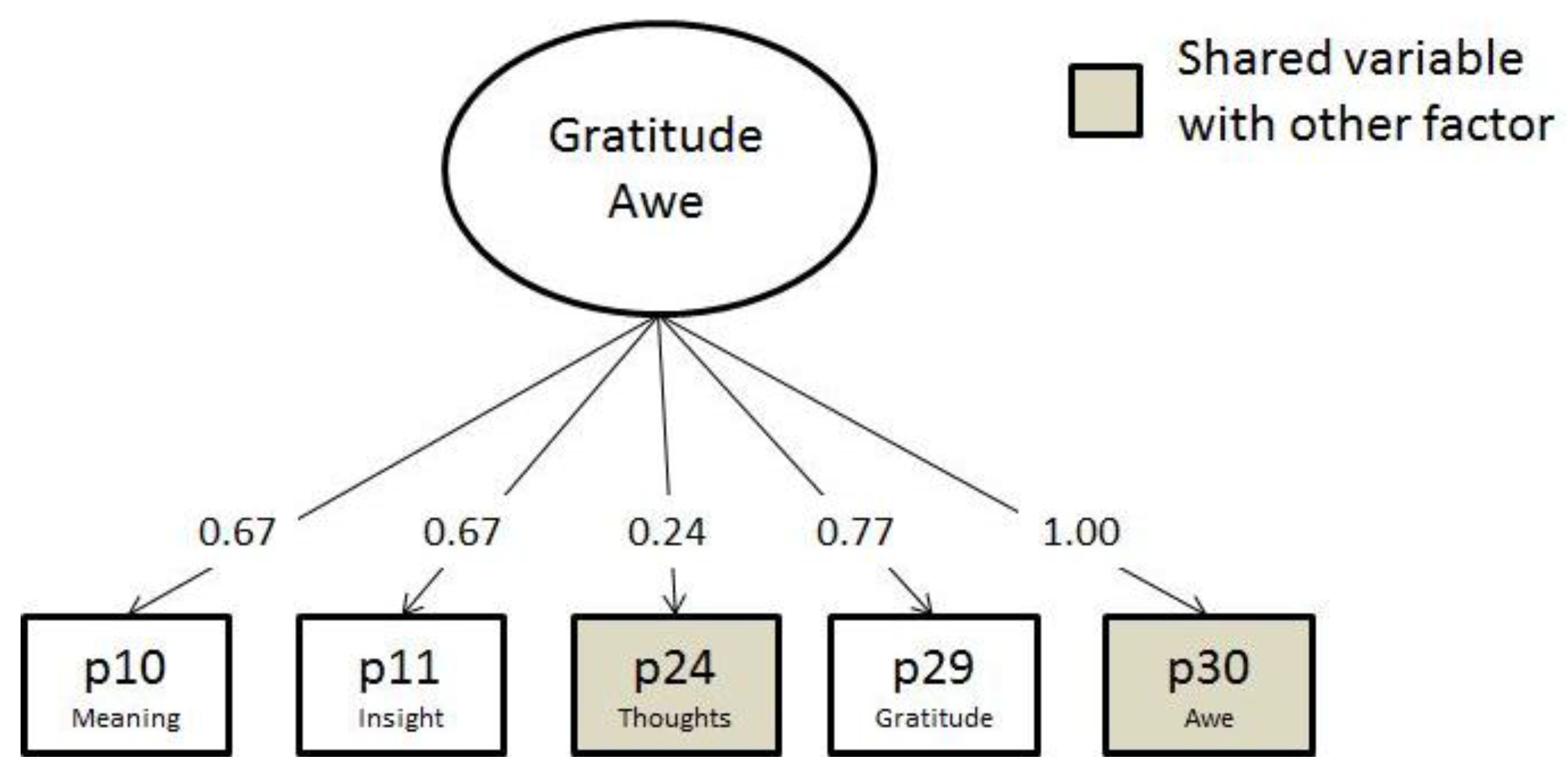

- The 4-item factor Existentialistic practices/Gratitude and Awe (4% explained variance; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) combines two existentialistic items and two items from the primary “Gratitude/Awe scale”.

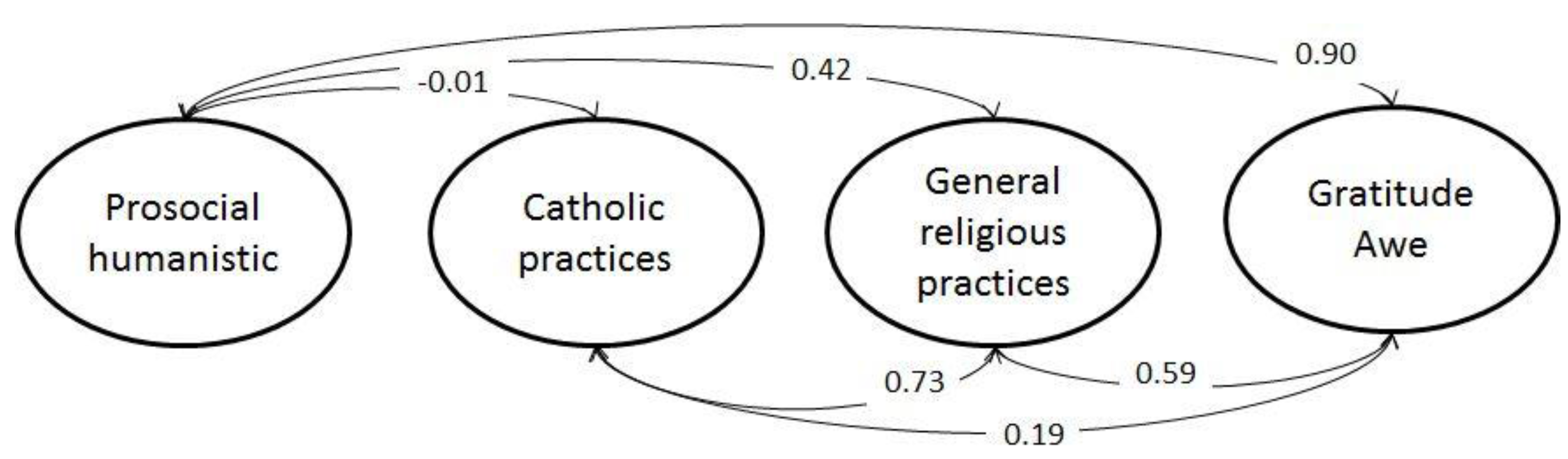

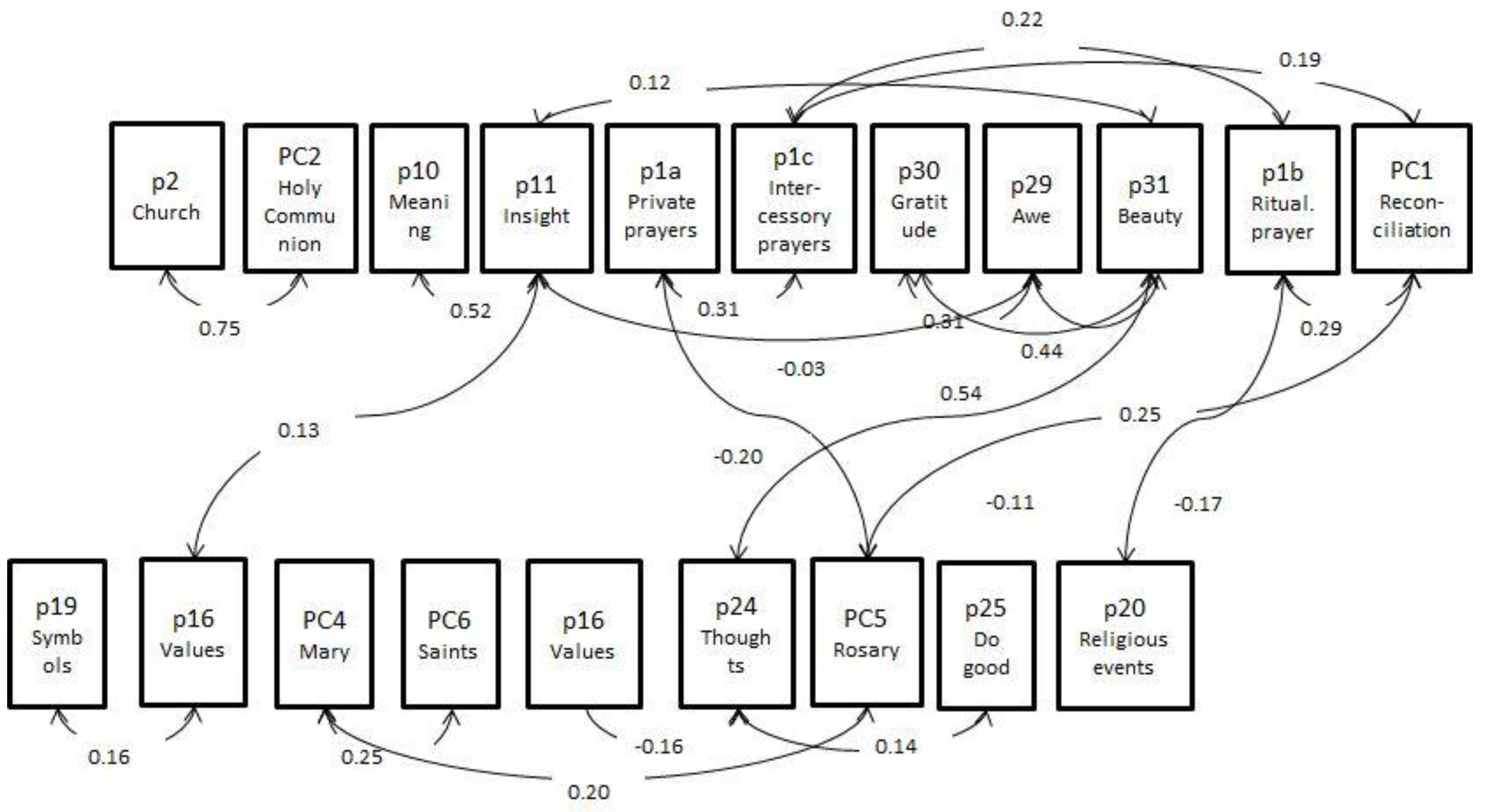

3.3. Structured Equation Model

3.4. Correlations with Life Satisfaction, Well-Being and Transcendence Perception

3.5. Expression of SpREUK-RP Scores in the Sample

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asparouhov, Tihomir, and Bengt Muthén. 2009. Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling 16: 397–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, Per, Lis Raabaek Olsen, Mette Kjoller, and Niels Kristian Rasmussen. 2013. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the SF-36 mental health subscale and the WHO-Five well-being scale. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 12: 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Peter F. Matthiessen, and Thomas Ostermann. 2005. Engagement of patients in religious and spiritual practices: Confirmatory results with the SpREUK-P 1.1 questionnaire as a tool of quality of life research. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 3: 53. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16144546 (accessed on 26 September 2005).

- Büssing, Arndt, Franz Reiser, Andreas Michalsen, and Klaus Baumann. 2012. Engagement of patients with chronic diseases in spiritual and secular forms of practice: Results with the shortened SpREUK-P SF17 Questionnaire. Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal 11: 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, Arndt. 2012. Measures of Spirituality in Health Care. In Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare. Edited by Mark Cobb, Christina M. Puchalski and Bruce Rumbold. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 323–31. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, Arndt, Eckhard Frick, Christoph Jacobs, and Klaus Baumann. 2016. Health and Life Satisfaction of Roman Catholic Pastoral Workers: Private Prayer Has a Greater Impact Than Public Prayer. Pastoral Psychology 65: 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt. 2017. Messung spezifischer Aspekte der Spiritualität/Religiosität. In Spiritualität. Auf der Suche nach ihrem Ort in der Theologie. Edited by Thomas Möllenbeck and Ludger Schulte. Münster: Aschendorf-Verlag, pp. 138–64. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, Arndt, Markus Warode, Mareike Gerundt, and Thomas Dienberg. 2017. Validation of a novel instrument to measure elements of Franciscan inspired Spirituality in a general population and in religious persons. Religions 8: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Robert A. Emmons, Randy J. Larsen, and Sharon Griffin. 1985. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personal Assessment 49: 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, Geoffrey. 1998. Seeing Christ in Others. An Anthology of Worship, Meditation and Mission. Norwich: Canterbury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, Lynn G. 2002. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Development, Theoretical Description, Reliability, Exploratory Factor Analysis, and Preliminary Construct Validity Using Health-Related Data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24: 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, Lynn G. 2011. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Overview and Results. Religions 2: 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwingmann, Christian, Constantin Klein, and Arndt Büssing. 2011. Measuring Religiosity/Spirituality: Theoretical Differentiations and Characterizations of Instruments. Religions 2: 345–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Faith/Experience | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| tradition | spiritual experience | ||

| Attitudes | |||

| Cognition: beliefs, afterlife convictions, ideals etc. | Emotion: unconditional trust, hope, etc. | ||

| Behaviors | |||

| Ethics: charity, etc. | Rituals: prayer, meditation, etc. | Altruism: charity, etc. | |

| Scores | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (Mean ± SD) | 44.0 ± 18.8 | 18–88 |

| Gender (%) | ||

| Women | 37.5 | |

| Men | 62.5 | |

| Educational level (%) | ||

| Secondary school (Haupt-/Realschule) | 14.1 | |

| High school (Gymnasium) | 70.0 | |

| other | 15.9 | |

| Religious denomination (%) | ||

| Catholic | 65.1 | |

| Protestant | 20.0 | |

| Other | 4.1 | |

| None | 10.8 | |

| Profession (%) | ||

| Students | 22.1 | |

| Medicine/psychology | 14.6 | |

| Pedagogy | 13.8 | |

| Theology | 8.8 | |

| Other | 21.1 | |

| Religious community | 20.6 | |

| Life satisfaction (SWLS) (Mean ± SD) | 27.7 ± 4.7 | 4–35 |

| Well-being (WHO-5) (Mean ± SD) | 60.7 ± 17.3 | 12–100 |

| Transcendence perception (DSES-6) (Mean ± SD) | 21.4 ± 7.8 | 6–36 |

| Mean ± SD (Range 0–3) | Difficulty Index (1.59/3 = 0.53) | Corrected Item–Scale Correlation | α if Item Deleted (α = 0.931) | Factor Loading | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prosocial-HUMANISTIC Practices | General Religious Practices | Catholic Religious Practices | Existentialistic Practices/Gratitude and Awe | ||||||

| Primary Scale | Cronbach’s alpha | 0.906 | 0.940 | 0.896 | 0.838 | ||||

| Eigenvalue | 90.2 | 50.0 | 10.1 | 10.0 | |||||

| PHP | p25 try to do good | 2.25 ± 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.496 | 0.927 | 0.840 | |||

| PHP | p23 consider the needs of others | 2.27 ± 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.488 | 0.927 | 0.827 | |||

| PHP | p22 try to actively help others | 2.14 ± 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.495 | 0.927 | 0.819 | |||

| PHP | p26 feel connected with others | 2.14 ± 0.87 | 0.71 | 0.588 | 0.926 | 0.728 | |||

| / | p17 be aware of how I treat the world around | 2.27 ± 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.379 | 0.929 | 0.654 | 0.338 | ||

| GA | p31 have learned to experience and value beauty | 2.30 ± 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.468 | 0.928 | 0.646 | 0.490 | ||

| PHP | p24 thoughts are with those in need | 1.82 ± 0.84 | 0.61 | 0.636 | 0.925 | 0.640 | 0.382 | ||

| ExP | p16 convey positive values and convictions to others | 2.07 ± 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.469 | 0.928 | 0.640 | 0.421 | ||

| RP | p20 participate in religious events (regardless of obligations) | 1.33 ± 1.10 | 0.44 | 0.744 | 0.923 | 0.796 | |||

| RP | p2 celebrating the Eucharist | 1.22 ± 1.25 | 0.41 | 0.751 | 0.923 | 0.796 | 0.405 | ||

| new | p1c intercessory prayer | 1.30 ± 1.17 | 0.43 | 0.769 | 0.922 | 0.790 | 0.334 | ||

| RP | p1a private praying (for myself, for others) | 1.55 ± 1.17 | 0.52 | 0.773 | 0.922 | 0.779 | |||

| new | PC2 receive the Holy Communion | 1.29 ± 1.28 | 0.43 | 0.725 | 0.923 | 0.763 | 0.400 | ||

| RP | p19 In my private area, religious symbols are important to me | 1.27 ± 1.14 | 0.42 | 0.772 | 0.922 | 0.715 | 0.354 | ||

| new | PC5 praying the Rosary | 0.56 ± 0.91 | 0.19 | 0.413 | 0.928 | 0.873 | |||

| new | PC1 Sacramental Confession | 0.59 ± 0.94 | 0.20 | 0.481 | 0.927 | 0.828 | |||

| new | PC4 ask the “Mother of God” for help and support | 0.90 ± 1.04 | 0.30 | 0.524 | 0.927 | 0.793 | |||

| new | PC6 strong relation to special saints | 0.71 ± 1.00 | 0.24 | 0.449 | 0.928 | 0.727 | |||

| new | p1b praying the Liturgy of Hours | 0.65 ± 1.13 | 0.22 | 0.568 | 0.926 | 0.419 | 0.708 | ||

| ExP | p11 try to get insight (also into myself) | 2.17 ± 0.88 | 0.72 | 0.476 | 0.927 | 0.433 | 0.714 | ||

| ExP | p10 reflect upon the meaning of life | 2.16 ± 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.465 | 0.928 | 0.416 | 0.704 | ||

| GA | p30 feeling of wondering awe | 1.61 ± 1.01 | 0.54 | 0.642 | 0.925 | 0.400 | 0.690 | ||

| GA | p29 feeling of great gratitude | 1.96 ± 0.93 | 0.65 | 0.640 | 0.925 | 0.487 | 0.303 | 0.573 | |

| Excluded items | |||||||||

| new | PC3 Sacrament worship | 0.76 ± 1.05 | |||||||

| SpP | p4a meditation (Christian style) | 0.89 ± 1.09 | |||||||

| SpP | p4b meditation (Eastern style) | 0.56 ± 0.94 | |||||||

| SpP | p6 reading religious/spiritual books | 1.34 ± 1.10 | |||||||

| SpP | p7 work on a mind-body discipline (i.e., yoga, qigong, mindfulness etc.) | 1.17 ± 1.08 | |||||||

| SpP | p8 perform distinct rituals (originated in other religious/spiritual traditions than mine) | 0.60 ± 0.94 | |||||||

| ExP | p13 work on my self-realization | 1.96 ± 0.88 | |||||||

| / | p21 believe in (my) guardian angel | 1.61 ± 1.14 | |||||||

| / | p9 turn to nature | 1.81 ± 0.97 | |||||||

| / | p27 volunteer work for others | 1.61 ± 1.01 | |||||||

| Religious Practices (SpREUK-RP) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prosocial-Humanistic Practices | General Religious Practices | Catholic Religious Practices | Existentialistic Practices/Gratitude and Awe | |

| Spiritual-religious practices (SpREUK-P SF17) | ||||

| Religious practices | 0.491 ** | 0.988 ** | 0.689 ** | 0.505 ** |

| Prosocial-humanistic practices | 0.887 ** | 0.448 ** | 0.189 ** | 0.596 ** |

| Existentialistic practices | 0.589 ** | 0.201 ** | −0.015 | 0.794 ** |

| Gratitude/Awe | 0.804 ** | 0.524 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.891 ** |

| Spiritual Mind-Body practices | 0.119 | 0.030 | 0.181 ** | 0.254 ** |

| Spiritual-religious Attitudes and Perceptions | ||||

| Transcendence Perception (DSES-6) | 0.392 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.496 ** | 0.417 ** |

| Live from the Faith/Search for God (FraSpir) | 0.366 ** | 0.693 ** | 0.658 ** | 0.454 ** |

| Life satisfaction/Well-being | ||||

| Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) | 0.307 ** | 0.073 | −0.024 | 0.168 ** |

| Well-being (WHO-5) | 0.248 ** | 0.007 | −0.051 | 0.124 |

| Prosocial-Humanistic Practices | General Religious Practices | Catholic Religious Practices | Existentialistic Practices/Gratitude and Awe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | n | 411 | 412 | 412 | 410 |

| Mean | 70.74 | 44.27 | 22.89 | 65.75 | |

| SD | 21.19 | 34.65 | 28.35 | 25.34 | |

| Skewness | −1.14 | 0.19 | 1.22 | −0.64 | |

| SE to Skewness | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| Kurtosis | 1.47 | −1.44 | 0.41 | −0.21 | |

| SE to Kurtosis | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | |

| All | z-Mean | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| z-SD | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Women (n = 150) | z-Mean | −0.13 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.11 |

| z-SD | 0.92 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 0.98 | |

| Men (n = 261) | z-Mean | 0.07 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.06 |

| z-SD | 1.04 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 1.01 | |

| F-value | 3.97 | 0.22 | 1.19 | 2.53 | |

| p-value | 0.047 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Educational level | |||||

| Secondary school (n = 58) | z-Mean | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.11 |

| z-SD | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.19 | 1.05 | |

| High school (n = 279) | z-Mean | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.11 | −0.04 |

| z-SD | 1.01 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 1.00 | |

| Others (n=65) | z-Mean | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.06 |

| z-SD | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.92 | |

| F-value | 0.09 | 5.93 | 8.84 | 0.56 | |

| p-value | n.s. | 0.003 | <0.0001 | n.s. | |

| Age groups | |||||

| <30 years (n = 131) | z-Mean | −0.05 | −0.72 | −0.59 | −0.23 |

| z-SD | 0.85 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.92 | |

| 30–40 years (n = 44) | z-Mean | −0.11 | −0.19 | −0.07 | −0.09 |

| z-SD | 0.89 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.01 | |

| 40–50 years (n = 55) | z-Mean | 0.08 | 0.15 | −0.08 | 0.23 |

| z-SD | 0.96 | 0.87 | 0.69 | 0.99 | |

| 50–60 years (n = 87) | z-Mean | −0.08 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.05 |

| z-SD | 1.23 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 1.01 | |

| >60 years (n = 80) | z-Mean | 0.15 | 0.59 | 0.72 | 0.17 |

| z-SD | 1.01 | 0.88 | 1.19 | 1.04 | |

| F-value | 0.93 | 41.39 | 30.47 | 3.30 | |

| p-value | n.s. | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.011 | |

| Religious congregation | |||||

| No (n = 324) | z-Mean | 0.08 | −0.18 | −0.36 | 0.03 |

| z-SD | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.95 | |

| Yes (n = 85) | z-Mean | −0.31 | 0.69 | 1.38 | −0.14 |

| z-SD | 1.47 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 1.17 | |

| F-value | 10.43 | 58.07 | 402.34 | 2.12 | |

| p-value | 0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | n.s. | |

| Religious denomination | |||||

| Catholics (n = 262) | z-Mean | −0.02 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.03 |

| z-SD | 1.09 | 0.98 | 1.06 | 1.02 | |

| Protestants (n = 83) | z-Mean | 0.11 | −0.48 | −0.64 | −0.08 |

| z-SD | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.95 | |

| Other (n = 17) | z-Mean | 0.46 | −0.12 | −0.46 | 0.71 |

| z-SD | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.71 | |

| None (n = 45) | z-Mean | −0.36 | −1.05 | −0.70 | −0.37 |

| z-SD | 0.79 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.92 | |

| F-value | 3.53 | 43.72 | 39.95 | 5.26 | |

| p-value | 0.015 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Büssing, A.; Recchia, D.R.; Gerundt, M.; Warode, M.; Dienberg, T. Validation of the SpREUK—Religious Practices Questionnaire as a Measure of Christian Religious Practices in a General Population and in Religious Persons. Religions 2017, 8, 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120269

Büssing A, Recchia DR, Gerundt M, Warode M, Dienberg T. Validation of the SpREUK—Religious Practices Questionnaire as a Measure of Christian Religious Practices in a General Population and in Religious Persons. Religions. 2017; 8(12):269. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120269

Chicago/Turabian StyleBüssing, Arndt, Daniela R. Recchia, Mareike Gerundt, Markus Warode, and Thomas Dienberg. 2017. "Validation of the SpREUK—Religious Practices Questionnaire as a Measure of Christian Religious Practices in a General Population and in Religious Persons" Religions 8, no. 12: 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120269

APA StyleBüssing, A., Recchia, D. R., Gerundt, M., Warode, M., & Dienberg, T. (2017). Validation of the SpREUK—Religious Practices Questionnaire as a Measure of Christian Religious Practices in a General Population and in Religious Persons. Religions, 8(12), 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120269