Abstract

Through a focus on the early history of a mass mediated ritual practice, this essay describes the “apparatus of belief,” or the specific ways in which individual religious belief has become intimately related to tele-technologies such as the radio. More specifically, this paper examines prayers that were performed during the immensely popular Healing Waters Broadcast by Oral Roberts, a famous charismatic faith healer. An analysis of these healing prayers reveals the ways in which the old charismatic Christian gesture of manual imposition, or laying on of hands, took on new somatic registers and sensorial attunements when mediated, or transduced, through technologies such as the radio loudspeaker. Emerging from these mid-twentieth century radio broadcasts, this technique of healing prayer popularized by Roberts has now become a key ritual practice and theological motif within the global charismatic Christian healing movement. Critiquing established conceptions of prayer in the disciplines of anthropology and religious studies, this essay describes “belief” as a particular structure of intimacy between sensory capacity, media technology, and pious gesture.

As if the rite of touching a sacred object, like every contact with the divinity, were not equally a communication with God!Marcel Mauss, On Prayer (1908) [1].

Every Sunday throughout the 1950s, millions of Americans were tuning-in their radios to hear Oral Roberts’ Healing Waters Broadcast. In addition to an extensive network of radio stations within the United States, this charismatic faith-healing program encircled the globe via transmitters strategically located throughout Europe, Africa and India. Roberts claimed that he was divinely inspired to name the broadcast after an old hymn that he recalled from his childhood days when he attended brush arbor revivals with his family. In addition, the healing evangelist made an explicit connection between the old camp meeting song and the biblical story from the book of John (5:1–15) that describes how the lame, blind and crippled were healed by dipping into the effervescent waters of the Bethesda pool. The therapeutic currents of this pool were activated at certain seasons of the year when an angel descended to “trouble the waters.”

In a special radio issue of his Healing Waters Magazine, Roberts summed up the significance of the title of the broadcast: “I thought of the ‘Healing Waters,’ of waters troubled by an angel, but above all, of the Master standing at the water’s edge with His healing touch” ([2], p. 15).1 A chorus accompanied by piano brought the program on the air, and the words of the broadcast’s eponymous theme song resounded through a soft haze of static:

- Where the healing waters flow,

- Where the joy celestial glow,

- Oh there’s peace and rest and love,

- Where the healing waters flow!

With these liquid resonances in mind, this essay explores how the radio organized new possibilities for the somatic flows of Pentecostal prayer. The phrase somatic flow describes the physical sensation of warmth, electricity, tingling, etc. that circulates through both the body of the patient and the healer during the performance of charismatic healing touch. With these embodied flows in mind, this essay describes how essential theological and performative elements of charismatic Christian prayer such as the anointing, baptism in the spirit, and the laying on of hands became intimately linked with the radio apparatus in the formative years of mass-mediated healing rituals. By tracing the development of a mass mediated prayer technique, this essay describes how individual religious experience has been organized through an “apparatus of belief” that binds sensory capacities and physical gestures with, and through, media technology.

The most important segment of the Healing Waters Broadcast occurred toward the end of the thirty-minute program, when after several songs, some testimonies of miraculous healing by faith, and a brief sermon, Oral Roberts delivered the healing prayer during what was referred to as the “prayer time” of the program. As a specific technique of prayer, the prayer time of the broadcast was structured around what Roberts termed “the point of contact.” Now a ubiquitous term in the global language of Pentecostal and charismatic Christian healing prayer, Oral Roberts developed this technique specifically in relation to the radio apparatus.2 According to Roberts, the radio as a point of contact allowed the patient to “turn loose” or “unleash” a kind of standing reserve or potentiality of faith that resided within the interior of the religious subject. Throughout his ministry, Roberts used technological metaphors to explain this charismatic technique of prayer:

A point of contact is a means of sending your faith to God. A point of contact is something tangible, something you do, and when you do it you release your faith toward God. All sources of power have a point of contact through which they can be reached or tapped. You flip a light switch, and what happens? The light comes on. You step on the starter of your automobile and the motor hums. You turn a hydrant and the water comes out. In each case, whatever you do to start the flow of energy becomes your point of contact.3[5]

Once again, it is not mere coincidence that Roberts was constantly invoking metaphors of technology to describe the point of contact, as the first explicit formulation of this new prayer-gesture emerged within the context of his popular radio broadcast. In his article entitled, “The Story Behind Healing Waters,” Roberts explains the basic ideas behind the radio as a point of contact:

I conceived the idea of placing my hand over the microphone while people put their hands on the radio cabinet and by these two actions forming a double point of contact. From the very beginning of the Healing Waters Broadcast, I have felt led to offer a healing prayer at the close of each program…My preaching is to help people reach a climax in their faith and then I bring the sermon to a quick close and offer the healing prayer. At this time people gather around their radios and place their hands on their radio cabinets while I place mine over the microphone as a point of contact in lieu of placing my hands upon them…It has been amazing how many thousands of people have caught on to this idea and have turned their faith loose. They have believed while I prayed and in their believing, have been healed. Some very powerful miracles have been wrought through the broadcast and still even greater miracles are being wrought from week to week.4[1]

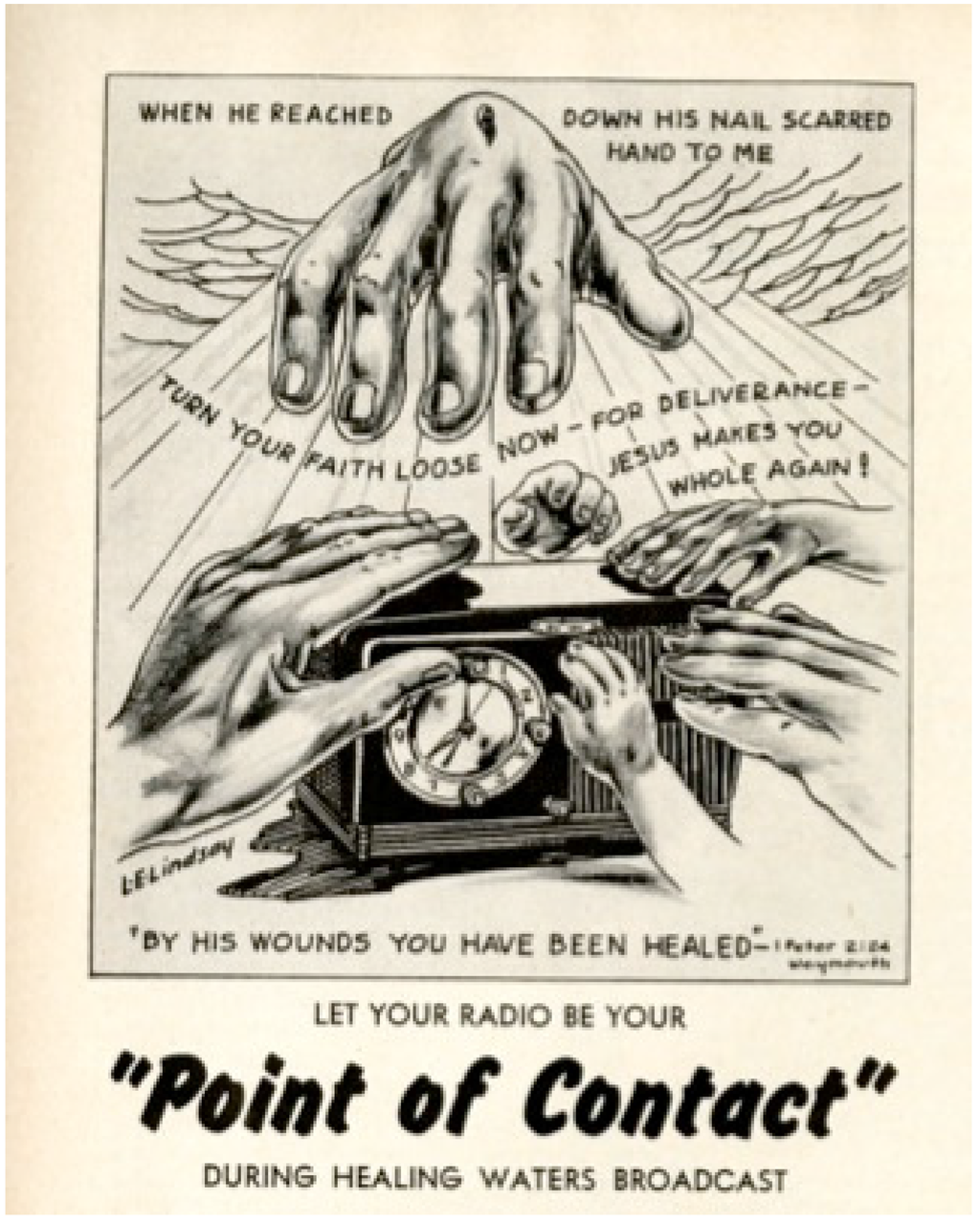

In its earliest formulations, the point of contact was imagined as a technological supplement to the charismatic sensations of tactility and the communication of healing power actuated through the ancient ritual gesture of handlaying. Throughout the history of Christianity, the ritual gesture of placing or pressing the hand upon various parts of the body has been practiced as a form of political initiation, consecration and miraculous healing.5 As millions of listeners tuned-in to the “prayer time” of the broadcast, audiences began to experience the distanced voice-in-prayer on a new somatic register (Figure 1). The radio loudspeaker translated the praying voice into a series of warm vibrations that were manually experienced as listeners laid their hands upon the “radio cabinet” as a point of contact between the everyday and the sacred. In this way, technical reproduction allowed for a new tactile sensation of the warm vibrations of the voice through the hand, signaling a shift in the pious sense of “touching-hearing” attuned through the practice of prayer. Thus, the early Christian ritual of handlaying (manus imposito) for the efficacious communication of healing virtue, prestige and power was, quite literally, interfaced with the apparatus [9]. In addition to the somatic vibrations of language, the large glass tubes of the older model “radio cabinets” would have created a warm electromagnetic field that also enlivened the mediated reverberations of prayer with an auratic presence. In this way, the ecstatic “climax” of prayer that was previously referred to by Roberts is intimately related to the visceral sensations of sound generated through the apparatus itself.

Figure 1.

Illustration from Healing Waters Magazine.

Transcriptions from the prayer time of the Healing Waters Broadcast will help evoke the specific textures of what Bruno Reinhardt, in his analysis of the pedagogical practice of “soaking in tapes” in a Ghanaian seminary, aptly terms the “haptic voice” [10]. These visceral testimonies, in turn, will shed light on the specific implications of this tactile radio voice for Pentecostal rituals of faith healing.6

1. Healing Waters Broadcast, 25 May 1952

[25:30] Heavenly father, in the name of Jesus of Nazareth I come to thee for the deliverance of every man, woman and child who is believing thee around their radio cabinets right now. Father, I believe God. I believe that you can do for us what no man can do. And that right now, there is no power like the power of God. Grant me this miracle according to the power of God in heaven, that every single one of them shall feel the healing presence of God going through every fiber of their mortal bodies, through their soul and mind. And that right now they shall be made whole from the crown of their head to the soles of their feet. Father heal this little girl; heal this little boy. Heal this dad, this mother. Let them feel the presence of Jesus; let it go through them to heal them in the name of the Lord. Now father I command the diseases to go: in the name of Christ COME OUT of them. And now neighbor, be thou made WHOLE! In the name of Jesus, be thou made WHOLE from HEAD to TOE by the POWER of Jesus Christ and through the name of the son of God. Glory to his precious name. Believe and believe right now. Right now. And God doth make thee whole from the crown of your head to the soles of your feet. In Jesus’ name, Amen.

[27:02] song “Only Believe”

- Only believe, only believe,

- All things are possible, only believe.

- Only believe, only believe,

- All things are possible, only believe.

At that pivotal moment during the performance of prayer when the healer commands the disease to leave the body of the patient, Roberts enunciates specific words with a percussive punch. These percussive poetics are indicated in the textual transcription through the use of bold, capital letters. The development of this percussive inflection during special sections of the performance is part of a long tradition of charismatic poetics of breath that signals to the congregation that the “anointing,” or power of the Holy Ghost, has possessed the speaker’s faculties of vocalization.7 What I want to emphasize here are the specific ways in which this anointed poetics of breath is transduced through the radio loudspeaker. Expanding upon the work of cultural historian Jonathan Sterne and anthropologist Stefan Helmreich, I define transduction as the transformation of “sound into something else and that something else back into sound” ([12], p. 22).8 Like a percussive instrument in a rite of passage, the electromagnetic diaphragm of the radio loudspeaker becomes a drum, sounding out the curative technique in disjointed bursts [14].

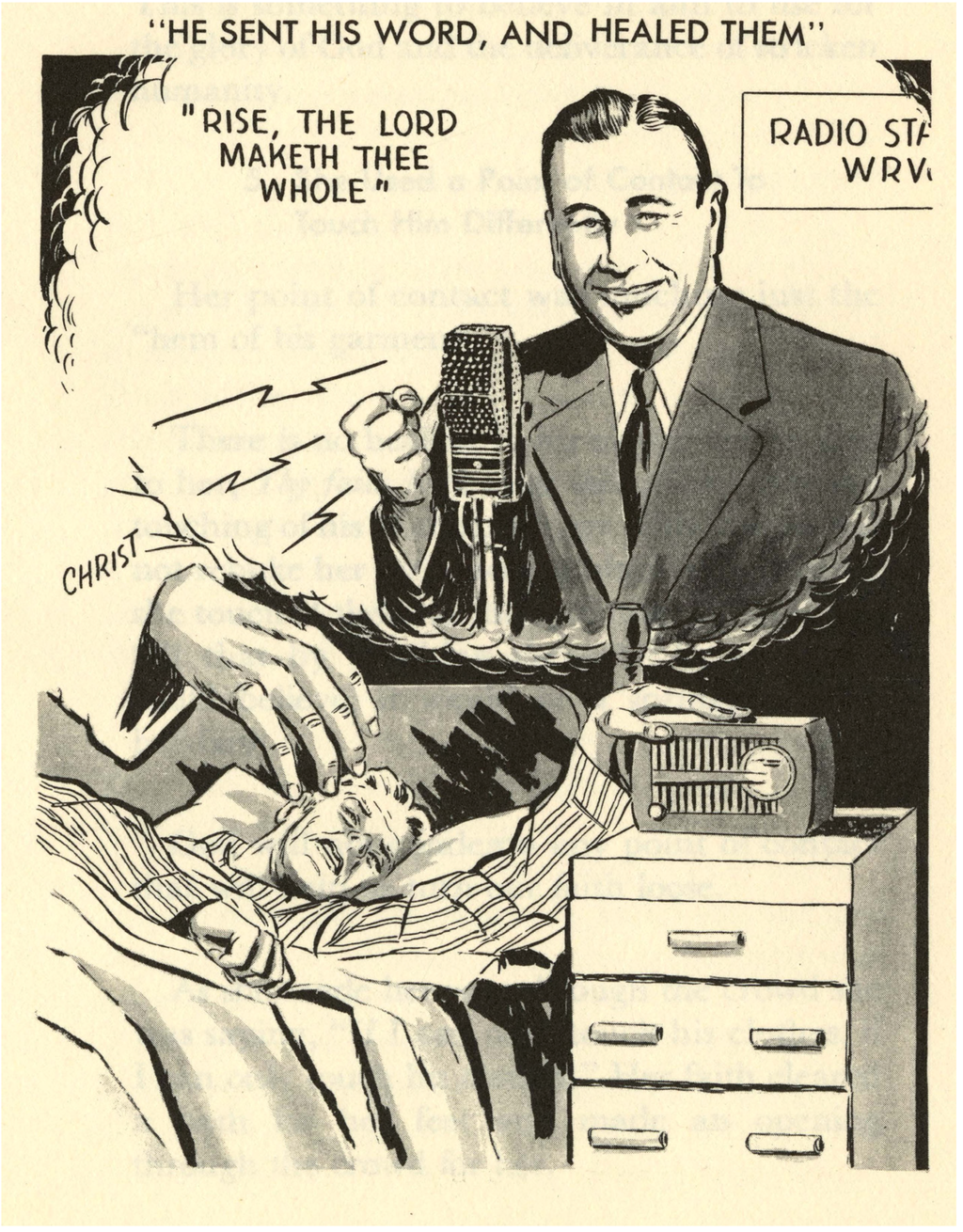

In this way, a charismatic technique of breath is transduced into a series of percussive pressures that literally resonated upon the hand of the patient. The radio apparatus affects the anointed voice-in-prayer in specific ways that cannot be abstracted from the medium of sound reproduction. In these formative years of mass-mediated ritual, the radio is not merely a passive instrumentality for the transmission of a discretely self-contained religious message, but the apparatus itself enlivens the performance of charismatic prayer with an auratic presence in excess of any stable representational content. The sound of prayer is translated into a tactile sensation of heat, pressure, and undulation; and thus the healing waters flow at that miraculous point where the capacities of the hand are augmented through the loudspeaker (Figure 2). One might summarize the ritual inversions and sensory disjunctures inherent in this performance of mass mediated healing prayer in the playful rhyme:

- The mouth of the speaker allowed the hand to hear,

- And the patient touched the radio to bring the healer near.

Figure 2.

Cartoon illustration from If You Need Healing Do These Things.

Note how the ritual preparations and prayer itself repeatedly invoke an awareness of bodily boundaries, both in terms of a proprioceptive sensation of “wholeness from the crown of their heads to the souls of their feet,” and the demonic egresses of disease through the “mortal body.” Moreover, the miraculous quickening of the body resounds at precisely that moment when the sensory capacities of the mortal flesh are extended and attuned by the augmentations of the radio apparatus. It is at this “point” where the body is able to feel the reverberations of prayer-through-the-hand that the excess of “healing presence” inundates the patient. Or, to put this another way, the body is exorcised of illness-causing demons and achieves a sensation of wholeness in the curative moment when the hand is placed upon the radio and the boundaries of the mortal body are augmented by a technological prosthesis.

2. Healing Waters Broadcast, 15 March 1953

[23:33] And now comes that wonderful moment of prayer in the Healing Waters Broadcast when something like two million people this time each week gather around their radio cabinets for my healing prayer. You come too, unsaved man, unsaved woman. You sick people come. Some kneel, some raise their hands, some touch their radio cabinets as a point of contact. But I’m going to pray for God to save ya, for God to heal ya. Believe now. Just after they sing “Only Believe” I’m going to pray.

[24:07] song “Only Believe”

- Only believe, only believe,

- All things are possible, only believe.

- Only believe, only believe,

- All things are possible, only believe.

[24:32] Now Heavenly father, thousands and thousands of people are gathered around their radio cabinets for this healing prayer, for thy salvation, for thy healing, for thy deliverance. Grant me the miracle of their salvation. Grant me the miracle of their souls being transformed from sin, saved by thy power. And now father grant me the miracle of healing for the mortal bodies of every man, woman and child who is looking to thee right now with faith in God. Here father is a man who’s been sick for years, a woman who’s been bedfast, a little child who is crippled and afflicted. Hear my prayer, and grant their healing in the name of Jesus. Thou foul tormenting sickness, thou foul affliction and disease, I come against you in the name of the savior. In the name of Jesus of Nazareth, not by my name, but by the name and power of the son of God. And I take authority over you in the name of Jesus; and I charge you loose them. LOOSE THEM! COME OUT! COME OUT in the name of Jesus of Nazareth! And now neighbor, be thou made whole. Be thou made WHOLE! In the name of Jesus, be thou LOOSED from thy AFFLICTIONS! Rise and praise God and be made whole. Amen, and amen. Believe now with all your heart.

[26:02] song “Only Believe”

- Only believe, only believe,

- All things are possible, only believe.

- Only believe, only believe,

- All things are possible, only believe.

Like the rituals of entry and exit described by Hubert and Mauss in their classic work, Sacrifice: Its Nature and Function [1898], it is interesting to consider why the performance of healing prayer is bracketed by the repetitions of the song “Only Believe.” In other words, why must the proscriptions of the curative technique exclude the material exigencies of the point of contact in the selfsame performance wherein these material conduits are essential elements for the opening of communicative relays between the everyday and the sacred? Why the insistence on an abstracted and spiritual practice of Protestant “belief” when the material point of contact is a crucial aspect of the performance and its curative efficacy? At the very heart of the curative technique, this performance of revelation and concealment discloses the objectile dimension of prayer. The objectile of Pentecostal prayer connotes an irreducible materiality that is necessary for the appearance of faith, yet denied or disavowed during the ritual enactment of healing (hence the term objectile also resonates with the words projectile and abject). As the crucial performative and experiential dimension of prayer, the objectile can neither be attributed to a Pentecostal hypocrisy or anxiety in the face of “things of this world,” nor to an instrumental interpretation that describes the way credulous audience members are duped through the technological artifice of the healer. Instead of these typical explanations, the objectile of prayer suggests that the force or efficacy of the ritual hinges upon this simultaneous revelation and concealment of the material medium [15]. In other words, the objectile is not some anxious appendage or qualification to the performance of prayer, but intrinsic to the organization of ritual efficacy itself.

The concept of ritual efficacy is here limited to a description of the opening or organization of specific experiential frameworks in-and-through the performance of prayer. In this way, the efficacy of prayer emerges from its specific attunements of the senses. This organization of somatic experience, in turn, “heals” or enframes bodily experience, the classification of suffering, and the structures of everyday life in a profoundly different frequency. The proscriptions that characterize the objectile of prayer “set-up” the religious subject to experience the ritual environment—an environment that emerges, or is structured by material objects and media technologies—in a particularly compelling, perhaps even shocking, way. To deny or dismiss the very medium that is structuring an appearance of sacred presence amplifies the basic sensory experience of technological mediation with an even greater immediacy or actuality. This is not simply a logic of oscillation between two poles, of explicit awareness of the material infrastructure of healing on the one hand, or forgetting on the other, but a doubled awareness, that, like the objectile itself, experiences an excessive presence through the material medium precisely because it is a reproduction. In this ritual milieu, presence becomes doubled—simultaneously immediate and actual within the private space of the home or automobile, yet emerging from a displaced space somewhere else. The objectile of prayer thematizes this doubled awareness of the material infrastructure, and through this ritual performance organizes new structures of awareness and embodiment.

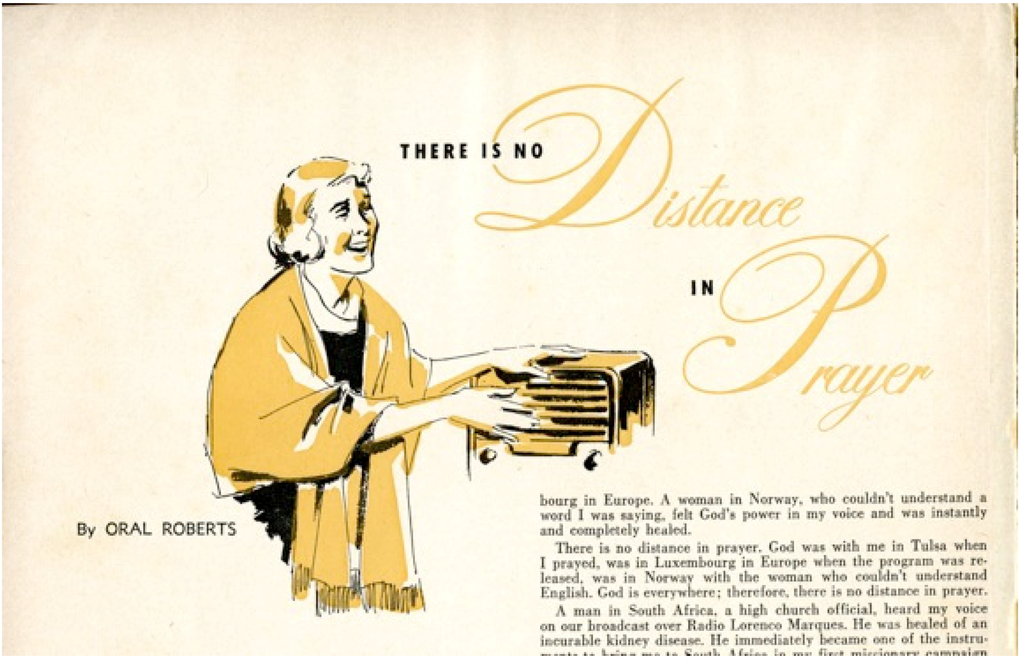

Since the beginning of the Healing Waters Broadcast in 1947, hundreds of thousands of letters were sent to the Oral Roberts headquarters in Tulsa, Oklahoma by listeners claiming to have been miraculous healed during the prayer time of the program. Many of these testimonies were reproduced in Roberts’ popular Healing Waters Magazine, and were intended to help cultivate a sense of belief in the reading audience. The following testimonies have been selected from the healing magazine and are representative of the general spirit of the healing narrative and its relation to the prayer-gesture of the radio as a point of contact (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Illustration from the Healing Waters Magazine.

PLACES HAND ON RADIO AND HEARS AGAIN

Dear Brother Roberts,

During your healing campaign in Jacksonville I was listening to your radio program. As you prayed for the sick I laid my hand and head upon the radio, and was healed of deafness in my left ear, which I had not heard out of in thirty years. I do praise God for what he has done for me. You may use this testimony in any way that others might believe God still hears.

L.D. Lowery,

3019 Dillon St.,

Jacksonville, Fla. ([16], p. 9).

NAZARENE MINISTER HEALED THROUGH BROADCAST

Dear Brother Roberts:

For years I have been bothered with bad tonsils. I had been holding a revival near Mineral Wells, Texas and had developed a serious case of tonsillitis. I had been taking Sulfa drug but to no avail. My fever was high, pulse irregular and my throat was swelled so inside until I could hardly swallow.

I was driving home that night after services and was suffering considerably. Brother Roberts’ program was coming over my car radio and when he asked those in radio-land to lay their hand on the radio if they wanted healing, I did so. As he prayed, I prayed, and suddenly it seemed that something turned loose in my throat, and I swallowed and found the swelling was all gone. My temperature was normal and my pulse was regular. That has been nearly four years ago, and I have never had a sore throat since that time. Praise God for his healing power!

Rev. J. Royce Thomason

Nazarene Minister

Eldorado, Oklahoma ([17], p. 9).

HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE HEALED

Dear Brother Roberts:

I want to write and tell you how God wonderfully healed my body through your prayers. I have been troubled with high blood pressure for years and I also had a bad kidney ailment. I had to go to bed as I was so sore I could not rest day or night. I was taking fourteen doses of medicine a day but, hallelujah to Jesus, I put my hand on the radio Sunday as you prayed for the sick and the healing power of God surged through my whole body and I was instantly healed! I arose in the name of Jesus and have not had any pain since. I do praise God for healing me. Enclosed is an offering to help on the broadcast.

A sister in Christ,

Frances Baker,

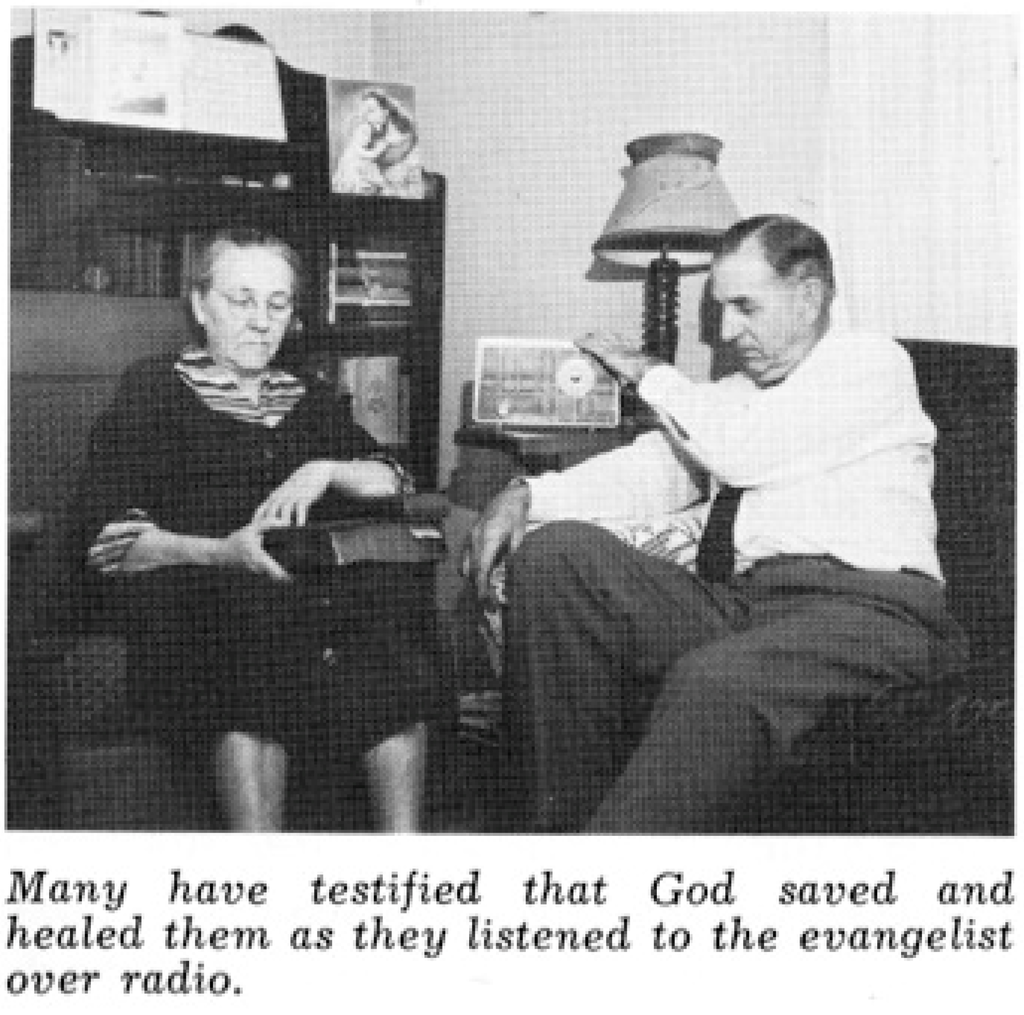

Fuquay Springs, N. C. ([18], p. 9) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Image from a pamphlet issued by the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association.

I Danced With Joy

Although I have been a minister of the gospel in England for 30 years, I have been unable since 1954 to follow my calling. In that year rheumatic fever struck me twice leaving me with locked joints in my shoulders and arms. I became almost helpless and my wife had to assist me even to dress. We listen to your radio program here in England over Luxembourg, 208 meters, at 11 p.m. each Tuesday and it has become the highlight of the week for us. One Tuesday night in April this year, as you were praying for the sick, I placed my still locked arms on the radio and claimed the healing power of Jesus Christ. The power of God swept through my body—I was drenched with perspiration as the poisonous acids left me. My joints were instantly loosed and set free. I threw both arms above my head and danced with joy for complete liberation. Now, at 64 years of age, I am in perfect health and re-entering the ministry. I have purchased a piano-accordion for my work and since my glorious healing I play it lustily without the slightest twinge of pain. May God continue his blessings upon you and your wonderful work for Him.

Rev. Robert Williams, Walton-on-Naze, Essex, England [19].

With these somatic surges of divine power and miraculously loose body parts in mind, I would like to contrast the description of radio prayer I am here elaborating with Thomas Csordas’ ground breaking work on practices of Charismatic Catholic healing. Because of the relevance to the current analysis, Csordas’ Presidential Address to the Society for the Anthropology of Religion (2002) is worth quoting at length.

This intimate alterity appears again in the Charismatic practice of “resting in the spirit,” in which a person is overwhelmed by divine power/presence and falls, typically from a standing position, into a sacred swoon…I also suggested that the experience is constituted in the bodily synthesis of preobjective self processes. This is to say that the coming into being of “divine presence” as a cultural phenomenon is an objectification of embodiment itself. Consider the heaviness of limbs reported by people resting in the spirit. Quoting Plugge, R. M. Zaner points out that “within the reflective experience of a healthy limb, no matter how silent and weightless it may be in action, there is yet, indetectably hidden, a certain ‘heft’” [20], p. 56. This thing like heft of our bodies in conjunction with the spontaneous lift of customary bodily performances defines our bodies as simultaneously belonging to us and estranged from us, and hence the alterity of the self is an embodied otherness. While resting in the spirit, the heft is always there for us indeterminately and preobjectively is made determinate and objectified. Its essential alterity becomes an object of somatic attention within the experiential gestalt defined as divine presence.([21], pp. 169–70)

As a specific technique of charismatic healing, the radio as a point of contact marks an “exteriorization” of the “intimate alterity” and “primordial aspect of the self” described by Csordas. As a bodily prosthesis that extends the capacities of hearing into the field of touch (a kind of supra-sensitive hearing), the point of contact, like the Charismatic Catholic healing practices described by Csordas, also thematizes an embodied doubling; yet, this alterity resonates at the interface between everyday sensory capacities and their extension through material objects and media technologies. Indeed, given the etymological resonances of the term “prosthesis” with the Eucharistic elements and the theme of miraculous transformation, we might substitute Csordas’ “preobjective” with “prosthetic” in our description of the production of divine presence [22].

This term, moreover, foregrounds the concern of charismatic Christianity with the gift (charism) of discernment, or an infilling of the Holy Spirit that allows the subject to register that which eludes the everyday sensory capacities. Troubling the subject with a presence that persists just beyond capacities of the ‘natural’ or ‘unarmed’ sensory faculties, in an age of mass-mediated ritual sacred presence is revealed at that “point” between the body and its technological attunements.

This technological artifice at the heart of the curative technique recalls “the moment of prestidigitation” described by Mass and Hubert in their classic work, A General Theory of Magic (1902):

Imagine for a moment—if you possibly can—the state of mind of a sick Australian Aborigine who calls on a sorcerer…Beside him the shaman dances, falls into a cataleptic fit, has dreams. His dreams take him up into the other world and when he comes back, deeply affected by his long journey into the world of souls, animals and spirits, he cunningly extracts a small pebble from the patient’s body, which he says is the evil spell which has caused the illness. Obviously there are two subjective experiences involved in these facts. And between the dreams of one and the desires of the other there is a discordant factor. Apart from the sleight of hand at the end, the magician makes no effort to make his ideas coincide with the ideas and needs of the client. These two individual states coincide only at the moment of prestidigitation. There is, then, no longer at this unique moment a truly psychological experience, either on the side of the magician, who cannot delude himself at this point, or on that of the client, because the alleged experience of the latter is no more than an error of perception, beyond a state of critical resistance, and thus beyond being repeated if not supported by tradition or by and act of constant faith.9[23]

Mauss and Hubert’s analysis of the curative rite need not be limited to the “primitive” procedures of the Australian Aborigine, but is directly relevant to the current description of the therapeutic environment organized through the radio as a point of contact. Here, the moment of prestidigitation (pesto = quick/nimble, digit-us = finger: sleight of hand, legerdemain, delusion, illusion), and the coincidence of two disparate individual states that it marks, seems en route to an account of religious experience and its relation to technologically mediated “special effects” that are constantly outpacing the everyday structures of awareness [25]. Moreover, the “error of perception” described in this classic account evokes the sensory disjunctures and extensions that are orchestrated in mass-media ritual contexts such as the prayer time of the Healing Waters Broadcast. The radio as a point of contact is a moment of prestidigitation that “quickens” the force of ritual language with a presence in excess of its representational content. This sensory disjuncture between the sound of language and its tactile resonances facilitates a therapeutic transformation into a new mode of somatic awareness and understanding of illness, disease, and suffering.

Roberts often emphasized the temporal dimensions organized through the point of contact. For example, in the popular instructional book, How to Find Your Point of Contact with God, he describes how this particular prayer-gesture “sets the time” of the miraculous cure:

If I said, “I’ll meet you,” and you said, “When?” and I said, “Anytime,” and you said, “Where?” and I said, “Anywhere,” more than likely we would never meet. But if I said, “Meet me tomorrow at 2:00 PM at the front entrance of the main post office in your town,” then we would have set the time and the place, and we would expect to meet. When you set a time for something to take place, you reach of point of expectation. The bible teaches you to expect a miracle if you want it to happen.([5], p. 8)

Like the clocks that were often built into the radio sets of the time, the radio as point of contact instantiated a specific charismatic temporality by cultivating a sense of immediacy for the patient. Yet, this temporal awareness actuated by the radio as a point of contact is not merely a stable and fixed time signaled by a clock. To be sure, the point of contact “sets the time,” however, this charismatic temporality organized through the apparatus is sustained by what Victor Turner, in his analysis of the disproportionate, grotesque, and off-kilter elements of the ritual form, terms “anti-temporality” [26]. This ritual anti-temporality connotes a rupture in the habitual rhythms of everyday life. Thus, the sense of immediacy produced during the “Prayer Time” of the Healing Waters Broadcast is doubled, both in terms of a distant and public voice resonating within the private space, and as a special effect of sound-prayer registered through the hand [27]. In this disjointed ritual environment, sensations of divine presence and miraculous healing are organized through the radio apparatus.

As a comparative foil to the specific claims I am making about the off-kilter temporalities of radio ritual and the concomitant shifts in the performance and sensation of healing prayer structured therein, let us briefly turn to another crucial objectile in the history of Pentecostal prayer, the “anointed handkerchief.” Since the early days of Pentecostalism, these fragments of anointed fabric (also termed “prayer cloths,” “blest cloths,” “faith cloths,” etc.) have been circulated through personal exchanges of hand and postal relays for the purposes of divine healing, protection, and miraculous accumulation. Following the etymological accounts of the ancient term “belief” (cred/credo) by de Certeau and Benveniste, the “belief” organized through the circulation of prayer cloths follows a classic economic model of temporal articulation [28]. More specifically, through a series of exchanges, deferrals and delays, the circulation of the prayer cloth structures a particular experience of belief for the patient.

In contradistinction to this temporal articulation of belief through exchange, the radio as point of contact articulates its miraculous temporality through a technologically produced special effect, or particular attunement of the sensory faculties. In this way, the radio inaugurated a new apparatus of belief that parasitically subsisted upon the specific sensory disjunctures of prayer through the radio.

Concepts such as the “apparatus of belief” and the “objectile” that I have employed to describe formative moments in the history of mass-mediated healing challenge longstanding and entrenched understandings of prayer in the disciplines of anthropology and religious studies. Emerging during the formative years of these disciplines circa 1900, these influential accounts describe prayer as a history of progressive abstraction from the material world into the silent recesses of a cognitive interiority.10 I have deployed these concepts as a critique against this model, one which persists and continues to orient many of the basic assumptions behind the academic study of prayer.11 The organization of new prayer-gestures such as the radio as point of contact suggest a new direction in the study of prayer that attends to the particular material and technological ”exteriorizations” that sustain and enliven the contemporary performance of belief. Indeed, Oral Roberts maps these new technological orientations quite well when he emphasizes that the prayer of faith can only be “loosed” when the subject makes tactile contact with an apparatus that extends the limited sensory faculties. In this way, “belief” itself is literally made sensible through an apparatus that interfaces media technology with older forms of ritual healing gestures and performances of prayer. This essay has demonstrated how the undercurrents of flow that orient key elements in the Pentecostal and charismatic Christian performance of prayer (the communication of power through handlaying, the poetic capacities of the anointing, the sensation of immersion, etc.) are enlivened in special ways through modern media technology (Figure 5 and Figure 6). From the dark electro-magnetic depths of the radio cabinet, the angel of transduction troubles the healing waters.

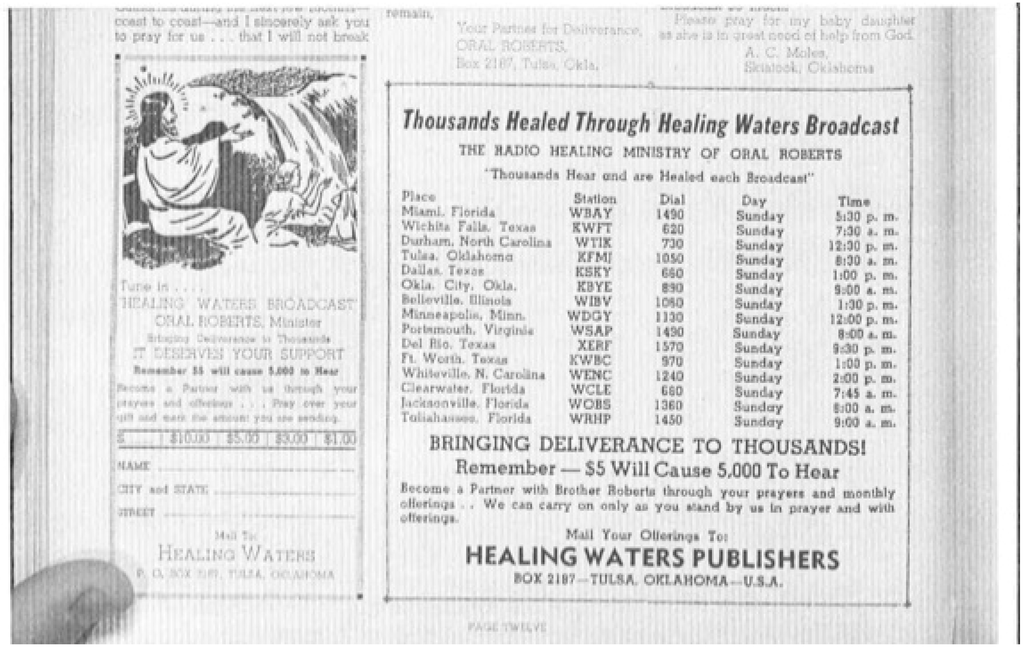

Figure 5.

Advertisement from the Healing Waters Magazine.

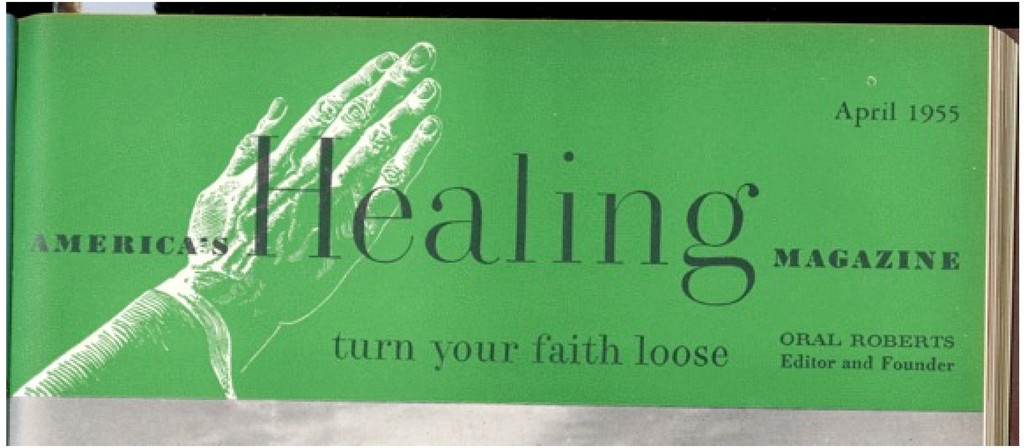

Figure 6.

This image of a spectral hand was featured on many of the front covers of America’s Healing Magazine.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Marcel Mauss. On Prayer. New York: Berghahn, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Oral Roberts. “The Story behind Healing Waters.” Healing Waters Magazine, June 1952, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Blanton. “Radio Prayers in Appalachia: The Prosthesis of the Holy Ghost and the Drive to Tactility.” In Radio Fields: Anthropology and Wireless Sound in the 21st Century. Edited by Lucas Bessire and Daniel Fisher. New York: New York University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas Bessire, and Daniel Fisher. Radio Fields: Anthropology and Wireless Sound in the 21st Century. New York: New York University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oral Roberts. How to Find Your Point of Contact with God. Tulsa: Y&N Publications, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Oral Roberts. If You Need Healing Do These Things. Tulsa: Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Tona J. Hangen. Redeeming the Dial: Radio, Religion, and Popular Culture in America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament. Mothership Connection, Casablanca Records, 1975.

- Michael Whitehouse. “Manus Impositio: The Initiatory Rite of Handlaying in the Churches of Early Western Christianity.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Notre Dame, 4 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno Reinhardt. “Soaking in tapes: The haptic voice of global Pentecostal pedagogy in Ghana.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 20 (2014): 315–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria José A. De Abreu. “Goose Bumps All Over: Breath, Media, and Tremor.” Social Text 26 (2008): 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan Sterne. The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stefan Helmreich. “An Anthropologist Underwater: Immersive Soundscapes, Submarine Cyborgs, and Transductive Ethnography.” American Ethnologist 34 (2007): 621–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodney Needham. “Percussion and Transition.” Man New Series 2 (1967): 606–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael Taussig. “Viscerality, Faith, and Skepticism: Another Theory of Magic.” In Magic and Modernity: Interfaces of Revelation and Concealment. Edited by Birgit Meyer and Peter Pels. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- L. D. Lowery. “Testimony Section.” Healing Waters Magazine 2 (1949): 9. [Google Scholar]

- Royce Thomason. “Testimony Section.” Healing Waters Magazine 15 (1952): 9. [Google Scholar]

- Frances Baker. “Testimony Section.” Healing Waters Magazine 4 (1949): 9. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Williams. “Testimony Section.” Abundant Life Magazine 5 (1957): 9. [Google Scholar]

- Richard M. Zaner. “The Context of Self: A Phenomenological Inquiry Using Medicine as a Clue.” Athens: University of Michigan Press, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Csordas. “Asymptote of the Ineffable: Embodiment, Alterity and the Theory of Religion.” Cultural Anthropology 45 (2004): 163–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan Buck-Morss. “The Cinema Screen as Prosthesis of Perception: A Historical Account.” In The Senses Still: Perception and Memory as Material Culture in Modernity. Edited by Nadia Seremetakis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- M. Mauss. A General Theory of Magic. New York: Norton, 1975, (my italics). [Google Scholar]

- Vincent Crapanzano. “The Moment of Prestidigitation: Magic, Illusion, and Mana in the Thought of Emile Durkheim.” In Prehistories of the Future: The Primitivist Project and the Culture of Modernism. Edited by Elazar Barkan and Ronald Bush. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hent De Vries. “Of Miracles and Special Effects.” In Religion and Media. Edited by Hent de Vries and Samuel Weber. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Victor Turner. “Images of Anti-Temporality: An Essay in the Anthropology of Experience.” Harvard Theological Review 75 (1982): 243–65. [Google Scholar]

- Theodor W. Adorno. Current of Music: Elements of a Radio Theory. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Michel De Certeau. “What We Do When We Believe.” In On Signs. Edited by Marshall Blonsky. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Ranulph Marett. “Spell to Prayer.” Folklore 15 (1904): 132–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel Mauss. Techniques, Technology and Civilization. New York: Durkheim Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- “Material and Visual Cultures of Religion.” Available online: http://mavcor.yale.edu/sites/default/files/Morgan-Syllabus-Religion-and-Materiality_0.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2016).

- “Reverberations.” Available online: http://forums.ssrc.org/ndsp/category/materiality/ (accessed on 15 March 2016).

- 1This essay utilizes research methods from the fields of media studies and cultural anthropology to explore the phenomenon of mass mediated healing prayer. I would like to thank Charles Hirschkind, Bruno Reinhardt, Michael J. Thate and two external peer reviewers for insightful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this essay. The shortcomings and flaws within this analysis, of course, are entirely my own.

- 2For a contemporary ethnography of the radio as a point of contact see: [3,4]. (see the comments in the References)

- 3For more explanations and instructions on the point of contact, see Roberts’ famous treatise on faith healing: [6].

- 4As is often the case with faith healers, it is likely that Roberts was refining a practice that was actually pioneered a decade earlier by Sister Aimee McPherson. From her powerful radio station KFSG, located within the Angelus Temple in Los Angeles, Sister Aimee would instruct her pious audience: “listeners kneel by the radio and place [your] hands on it to receive long-distance cures…As I lay my hands on this radio tonight, Lord Jesus, heal the sick, bridge the gap between and lay your nail-pierced hand on the sick in Radioland…” (Quoted In [7]). Although Roberts did not pioneer this practice, he was the first to explicitly formulate this technological prayer-gesture as the centerpiece of the ritual form. The somatic force of this new technique was quickly adopted by other prominent faith healers such as A. A. Allen and become so ubiquitous a phenomenon in the landscape of popular culture that the American funk band Parliament mimicked this faith healing technique in the song “Make My Funk the P-Funk” from their influential album, Mothership Connection (Casablanca Records, 1975):

We see in this album a powerful transduction of the poetic force of Charismatic Christianity.- Now this is what I want y’all to do:

- If you got faults, defects or shortcomings,

- You know, like arthritis, rheumatism or migraines,

- Whatever part of your body it is,

- I want you to lay it on your radio, let the vibes flow through.

- Funk not only moves, it can re-move, dig?

[8] - 5Cf. James 5:14 “Is any sick among you? Let him call for the elders of the church; and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord.”

- 6I would like to thank Steve Weiss and the archival technicians at the media laboratory of the Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for their generous assistance in digitizing these rare radio transcription discs. In terms of the basic infrastructure of the Healing Waters Broadcast, hundreds of large vinyl discs had to be sent out to individual stations throughout the world after they had been initially “cut” at a radio studio in Tulsa, Oklahoma. In turn, each station broadcast the pre-recorded program during a scheduled time each Sunday. Based on the thousands of listener testimonies that were sent to the Oral Roberts organization, the fact that these programs were “re-broadcast” does not seem to have detracted from the sense of immediacy and “presence” produced by this faith healing program.

- 7For an excellent account of a charismatic technique of breath, see: [11].

- 8For an anthropological analysis of the phenomenon of transduction, see also: [13].

- 9The second portion of this translation is taken from: [24].

- 10For a representative example of this logic of abstraction see for instance: [29] Marcel Mauss, whom I have invoked throughout this essay, is not immune to this narrative of progressive intellectualization and spiritualization from the world of material devotion. See for example certain sections of his early work On Prayer:

How different an account of prayer and its relation to the body Mauss delivers during his famous lecture (1934) on “Techniques of the Body”! It should be noted, however, that Mauss was already struggling with this question in his doctoral dissertation On Prayer. This is revealed in a more robust quotation of the passage that commenced this essay:Thus by tracing the development of prayer, it is possible to discern all the great trends which have influenced religious phenomena as a whole. It is known in fact, at least generally, that religion has undergone a double evolution. Firstly, it has become more and more spiritual. Whereas religion originally consisted of mechanical rites of a precise and material nature, or strictly formulated beliefs composed almost exclusively of tangible images, it has tended in the course of its history to give greater place to consciousness. Rites have becomes attitudes of the soul rather than those of the body and have become enriched by mental elements, sentiments and ideas. Beliefs for their part become intellectualized and, growing less and less material and detailed, are being reduced to an ever smaller number of dogmas, rich and varied in meaning.([1], pp. 23–24)

I read the emphasis on these sentences with the use of exclamation marks as indicative of Mauss’ struggle with technology, materiality and the body in his early work.For Sabatier, prayer is the essence of religion. “Prayer,” he says, ‘there you have religion in action’. As if every rite did not have this characteristic! As if the rite of touching a sacred object, like every contact with the divinity, were not equally a communication with God! Thus ‘the inner bonding of the soul to the God who is within’, such as takes place in the meditative prayer (ρρητος νωςις) of an ultra-liberal Protestant, becomes the generic type of prayer, the essential act of every religion.([30], p. 31) - 11Of course, important exceptions can be made to this general narrative of abstraction. The work of scholars such as Asad, Morgan, Meyer and Hirschkind, among others, and the burgeoning group of scholars in the field of anthropology and religious studies who have been influenced and inspired by their work, have begun the long process of bringing attention to the role disciplinary practices, body techniques, and material/media objects play in the organization of religious “belief.” For an useful reading list on this material turn in anthropology and religious studies, see David Morgan’s syllabus available on the Material and Visual Cultures of Religion Website (under the directorship of Sally Promey): [31]. For more explorations of prayer and its intimate relation to media technologies and devotional objects, including actual sound recordings from the Healing Waters Broadcast, see my curated Materiality of Prayer Collection within the Reverberations website sponsored by the Social Science Research Council: [32].

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).