Abstract

In the following, we characterize the contemporary conservative Evangelical movement as an example of contentious politics, a movement that relies on both institutional and noninstitutional tactics to achieve political outcomes. Examining multiple institutional and legislative outcomes related to the Faith Based Initiative, we seek to understand why some states have established state faith-based bureaucracies and passed significantly more faith-based legislation. We find that the influence of elite movement actors within state Republican parties has been central to these policy achievements. Furthermore, we find that the presence of movement-inspired offices increase the rate of adoption of legislation, and the passage of symbolic policies increases the likelihood of passage of more substantive faith-based legislation. We argue that the examination of multiple outcomes over time is critical to capturing second order policy effects in which new institutions, the diffusion of legislation and institutions, and increasing policy legitimacy may shape subsequent legislative developments.

1. Introduction

Religious groups have long played a crucial role in the delivery of social services [,] From short term needs such as food pantries and soup kitchens, to more long term activities like drug treatment and job training [], faith-based organizations have been a pillar of the social service sector [,,]. While these groups have long done these activities on their own, in the mid-1990s there was a new push by some conservative Republicans to make these groups the default purveyors of social services and severely limit the role of government in these services [,]. This effort, known as the faith-based initiative, may have long fallen off the front page, but remains an important feature of the political landscape for many religious organizations.

Faith-based initiatives encompass a variety of laws and practices aimed at increasing the role of religion in government-funded social services []. A domestic policy priority for the Bush administration, during the Bush years, faith-based organizations received over two billion a year in grants on average []. Beyond the money, the faith-based initiatives created a new seat at the table of government agencies for religious groups and allowed them access to government officials in a way they had never had before [], fundamentally altering how religious organizations and government interact.

Between 1996 and 2009, the most active years for the faith-based initiative, over 30 states created new faith-based liaison positions, state governments passed over 300 laws, and 11 federal government offices created faith-based offices. Conservative preferences for smaller government, a reduced welfare state, and privatization of public services have meshed nearly seamlessly with a genuine desire by many religious organizations to provide social services. In addition, this disposition has been supported aggressively by elements of the conservative Evangelical movement with an interest in fundamentally transforming the relationship between church and state. While less known than the battles over abortion or same sex marriage, we view these initiatives as extremely important developments in modern church/state relations.

In this paper, we trace the institutionalization and passage of faith-based initiatives at the state level from their inception in Texas under then Governor George Bush through his years as president during which the faith-based initiative was pursued with the most vigor at the state level. We examine multiple institutional and legislative outcomes related to faith-based initiatives, in order to better understand how Evangelical political elites and their allies have been so successful in creating faith-based institutions and uncover the drivers of the substantial variation in the volume of faith-based legislation passed within states over time. It is important to note that, while the Obama administration renamed the White House Office of Faith-Based Initiatives to include community and neighborhood partnerships, the office is intact, and all previously established federal faith-based government offices and liaisons have remained in place. Additionally, many states have maintained their faith-based bureaucracies even without the support of the Bush administration1. Thus, while the initiative certainly is not the domestic policy priority it once was, the supportive bureaucracies and policies remain largely in place.

To support the initiative, President Bush spent federal funds, created various federal level faith-based offices, and strongly encouraged states to follow his lead by enacting laws and policies in line with what he had done in Texas and at the federal level. Following the lead, 37 states created faith-based liaisons and enacted over 300 new laws that fundamentally reshaped how government interacts with religious groups []. This dramatic creation of a whole new area of public policy deserves our attention for several reasons. First, by examining the Faith-based Initiative, we begin to understand not just how faith-based policies became so popular over time, but also how and why other social policies can move to the forefront of a state’s policy agenda. Our findings emphasize the importance of the utilization, by movement actors and allies, of political institutions and the elevation of activists to governing positions as a tactic for the creation of favorable policy. We find that the creation of movement-inspired bureaucracies and policy diffusion increases the likelihood of the subsequent passage of faith-based legislation. In addition, the passage of largely symbolic policies is found to increase the likelihood of more substantive legislative outcomes down the road. We view these dynamics as central to understanding the political successes of the conservative Evangelical movement in this policy area.

Second, we contribute to a broader understanding of policy successes by the contemporary conservative movement. In recent decades, the conservative Evangelical movement has become an increasingly salient feature of the political landscape throughout the United States [,]. Encompassing a variety of organizational actors ranging from religious organizations and interest groups to traditional social movement organizations, this movement strives to increase the presence of a particular brand of Christianity in public life through both cultural and political change. These varied efforts are often issue specific, including support for anti-abortion legislation, school prayer, and anti-evolution initiatives. We use the term movement here, but the development and expansion of the Faith-based Initiative is not well described by a traditional social movement narrative. Rather the story is one of elite movement actors utilizing institutional tactics and existing political institutions to pursue movement goals. In essence, Evangelical movement actors and their allies have transformed the political opportunity structure and managed, through the creation of faith-based offices and liaisons, to literally incorporate movement goals into the bureaucratic fabric of the state. While this is distinct in many ways from the experience of a typical outsider social movement, we find this account to be consistent with, and even anticipated, by a broader contentious politics framework [] as we detail below.

Finally, our approach underlines the utility of taking a multifaceted and longitudinal perspective on policy developments and the benefits of attention to the manner in which political gains, even symbolic ones, may transform future opportunities for success. Given that for many the Faith-based Initiative has receded into obscurity, it bears emphasizing that this policy initiative represents an important and consequential shift in governing philosophy and practice in regards to church-state separation, as well as a codification of the desire to move social services out of the government sector and into the religious sector []. Furthermore, the faith-based initiatives are of enduring significance as the victories for Evangelical activists in this policy area in many ways paved the way for, and shaped the strategies of, subsequent campaigns in a variety of policy arenas.

1.1. Brief History of the Faith-Based Initiative

The original implementation of the Faith-based Initiative, then known as Charitable Choice, passed as a component of the 1996 Welfare Reform Act []. There were two underlying goals of this legislation, increasing cooperation between religious groups and government agencies and increasing the amount of funding going to religious groups providing social services [,,]. The passage of Charitable Choice and the subsequent Faith-based Initiative policies that followed in 2001 were the result of many years of lobbying by elite Evangelical movement activists who used their power within the Republican Party to promote these measures and create a new sustained state and federal level faith-based bureaucracy [,]. It cannot be overstated how central the efforts of conservative Evangelical actors were to early victories for the Faith-based Initiative at both the federal and state level. Unprecedented access was first gained in Texas under then-Governor George W. Bush who worked with Evangelical activists such as Marvin Olasky and Chuck Colson while creating these policies [,,,]. In 1996, Governor Bush created the first state faith-based liaisons and worked with state legislators to significantly alter state law regarding religion in the social service sector. Subsequently, other states, such as South Carolina, Oklahoma and New Jersey, followed suit with similar laws. Following the assumption of office by the Bush administration in 2001, significantly more states began to implement faith-based policies and practices in innovative ways, creating a wide variety of faith-based policies ranging from faith-based offices to special grant writing seminars, and even exclusive funding streams that were eventually declared unconstitutional [].

Unlike some previous social policy changes, such as Civil Rights legislation or the Equal Rights Amendment, which had their roots in broad-based movement activism, the institutionalization of faith-based policies did not emerge from a groundswell of bottom-up movement support [,,,]. There were no marches in the street or petitions being signed in churches demanding change in state and federal policy. The political backers of the Faith-based Initiative have had to create a supportive constituency for their policy after it was already in place. This push from movement activists at all levels of government has resulted in the implementation of some type of faith-based policy or practice in nearly every state [], with many states creating extensive faith-based bureaucratic structures that continue to exist long after initial efforts.

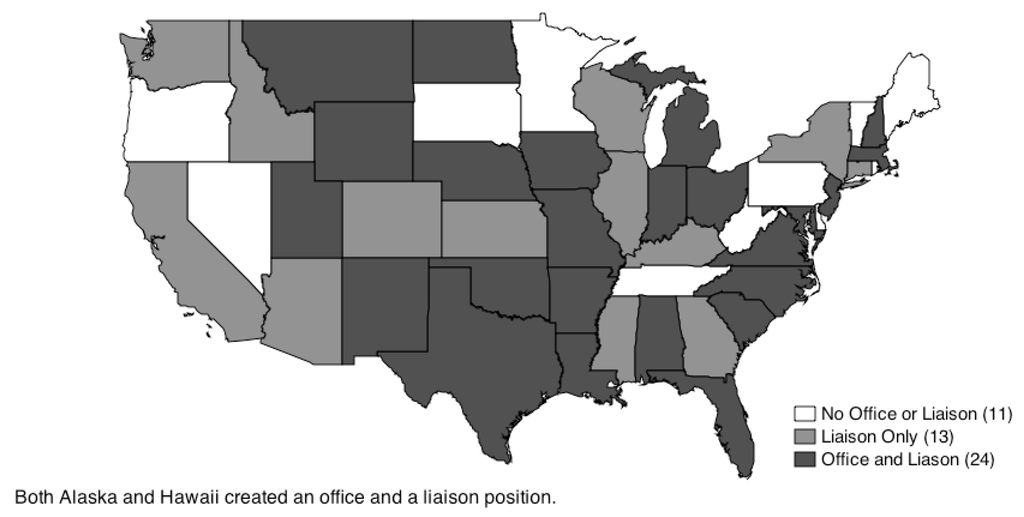

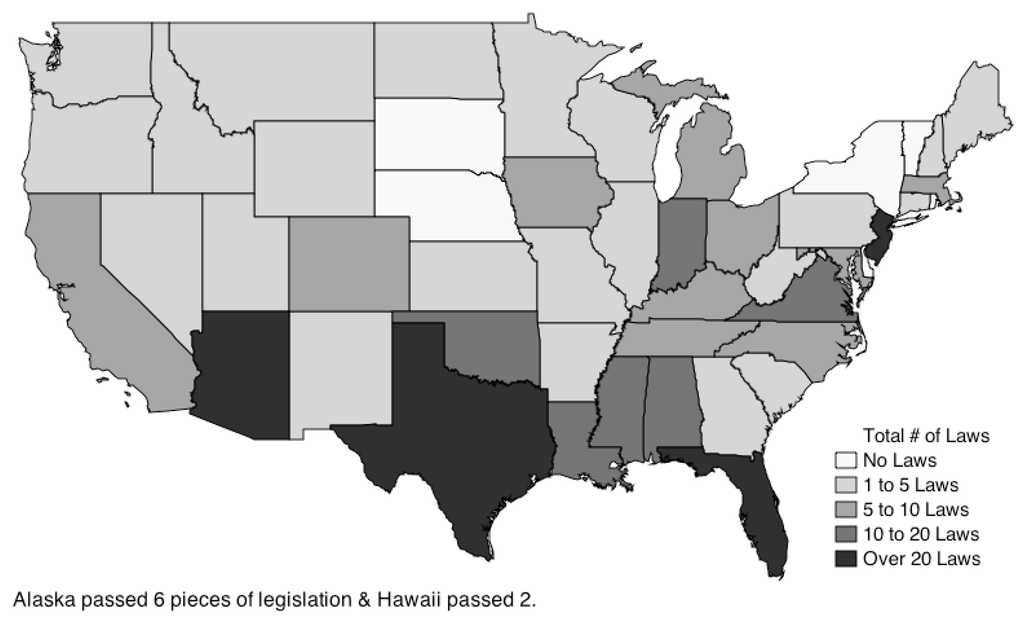

Since 1996, 37 states have created a faith-based liaison position, and 24 of these states also created a faith-based office (see Figure 1)2. In general, these offices have offered assistance and outreach to faith-based groups, as well as some help connecting with state organizations and navigating the federal government’s grants systems []. Interviews with faith-based liaisons suggest that these offices and liaisons became either witting or unwitting insider movement activists [] In one study, which involved interviews with 30 of 34 state faith-based liaisons between 2002 and 2005, all liaisons interviewed discussed reaching out to state legislators, state agencies, or working with governors to access funds directly or indirectly []. In addition to the proliferation of offices and liaison positions, the increase in state-level faith-based legislation was dramatic. Between 1996 and 2000, only 41 laws passed in a total of 10 states. Between 2001 and 2009 an additional 347 laws passed in 44 states (see Figure 2). During these years, the Faith-based Initiative became well established in the legal landscape of many states.

Figure 1.

State creation of offices of faith-based and community initiatives and faith-based liaisons 1996–2009.

Figure 2.

Faith-based legislation 1996–2009.

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. The Conservative Evangelical Movement and the Faith Based Initiative

In implementing faith-based policies across state bureaucracies and legislative landscapes, the conservative Evangelical movement met the twin goals of creating social policy based on conservative Christian ideals and attempting to shift the burden of care away from the government and to religious groups [,]. To effectively implement policy and change government bureaucracy, the conservative Evangelical movement relied on a number of non-traditional movement tactics that sought to transform the character of government institutions in order to implement these policies []. While social movements are traditionally viewed as outsiders, in reality, social movements often use a wide range of both institutional and noninstitutional tactics. Public interest groups may engage on occasion in noninstitutional tactics (such as organizing protest events), and many movements have institutionalized over time into hybrid interest group/social movement organizations []. This latter type of organization may function more like a social movement during issue campaigns and more like a public interest group during periods of demobilization. Central to these phenomena are coordinated efforts by actors with shared interests to influence governments [].

Tarrow [] argues that the long history of American religious social movements is distinctly characterized by repeated entry into the realm of conventional politics, more so than any other category of social movement. From this perspective, the contemporary conservative Evangelical movement is not an anomaly, but directly in line with historical precedents. We view the conservative Evangelical “movement” as a complex phenomenon comprised of a diverse and ever-shifting range of organizations and issue campaigns. Traditional social movement organizations utilizing noninstitutional tactics do make up a portion of this social and political movement, but these are neither the elements nor tactics that have driven the development of the Faith-based Initiative. Thus, while there is a long rich history of populist evangelical movements and issue campaigns [,], we are focusing here on a specific effort and policy development that is particularly elite-driven and, we argue, better understood from a perspective that emphasizes the use of institutional and insider tactics.

1.2.2. Conservative Evangelical Movement and Institutional Tactics

It has been argued that a hallmark of recent conservative social movements is that they often do not utilize protest or disruption []. Rather, these movements rely more heavily on traditional institutional tactics (mobilizing voters, lawsuits, petitions, and lobbying) and efforts to transform the political culture and climate by electing their own members to public office [,,,,,,,].

This specific tactic of entry into institutional political arenas has been critical to the policy accomplishments of the conservative Evangelical movement, as it has provided access to elite political institutions [,]. Such access has long been conceptualized as key to movement influence and success []. For more traditional “outsider” movements, access to, and influence upon, political institutions may be sought through activities such as lobbying, protest, or attempts to shape public opinion []. For the movement actors involved in the promotion of the Faith-based Initiative, access has been cultivated by merging, in a sense, with political and state institutions through the election and appointment of movement actors to office and through the creation of new government institutions charged with the pursuit of movement goals [,,].

Members of many social movements have pursued this specific approach of effecting social change and achieving movement goals by holding either political or bureaucratic positions within the state []. Santoro and McGuire [] refer to such individuals as “institutional activists” who use their insider status to promote outsider goals and highlight the roles of such activists in influencing the content of policies pursued by the civil rights and women’s movements. While not unique to the conservative Evangelical movement [], we believe it fair to argue that this movement has been uniquely successful in the use of this particular tactic. Since at least the 1980s, many elite movement actors explicitly advocated entry into governing institutions as an effective route to achieving social and political change [,,,]. From school boards to state level elections, and finally to the presidential election in 2000, movement leaders focused on creating friendly political environments to achieve their goals by electing movement members as political leaders [,,,]. The role of evangelical influence on social policy is then better conceptualized as not about religion per se, but rather about how religion influences mediating mechanisms, such as political parties, into shifting public policy [].

Entry by Evangelical movement actors into political institutions appears to have been the most successful and enduring at the level of state political parties, specifically Republican state parties. Orchestrated through a complex array of alliances and direct participation, religious conservatives have achieved increasing success and acceptance in the Republican Party [,]. A 1994 Campaign & Elections article suggested that the presence of movement-identified members and their allies was so substantial in some areas that the Christian Right “had a working majority in the principle state party organ” in eighteen states ([], p. 118; []). In addition to using their individual positions to advance movement priorities, movement actors have been successful in many states in reshaping local party institutions and agendas to serve movement ambitions; movement activists became political actors and movement goals became items on party platforms.

1.2.3. Faith-Based Initiatives and New Political Institutions

When social movements are successful in gaining protections or new advantages, these gains are occasionally accompanied by the creation of new institutions tasked with monitoring or administering these protections. Two prominent examples include the creation of the National Labor Relations Board and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Such institutions can provide new points of access for movements and, more broadly, may shift the balance of power between groups in conflict outside of the state. Scholars such as Burstein, Einwohner, and Hollander [] characterize these types of outcomes as “structural” gains in which the degree of access available to movements is increased in a significant and enduring fashion. In the case of the Faith-based Initiative, the creation of state faith-based offices and liaison positions represents not just an additional point of access, but a set of long-standing and government funded positions, staffed in some cases by movement actors, charged with the pursuit of movement goals []. Once in place, these offices and positions create a durable link between state governments and religious organizations.

1.2.4. Policy Diffusion as a Movement Outcome

Scholars have long noted that neo-institutional theory may provide an especially fruitful framework for understanding social and political change [,]. Gross, Medvetz, and Russell assert specifically that neo-institutional theory is useful in that “it offers a theory of change qua the diffusion of practices across organizational fields” ([], p. 338). In particular, they give the example of accounts of neoliberal policy reform that rely heavily on models of diffusion and isomorphism. We find these conceptual frames useful in the case of the Faith-based Initiative and suggest that while diffusion may occur somewhat “mechanically”, it is also the case that diffusion may be an explicit movement strategy and goal. In a top-down fashion, the White House under President Bush was instrumental in the diffusion of the initiative using conferences, monthly conference calls, and letters to governors to specifically encourage states to create partnerships and relationships with each other in order to increase faith-based practices. Subsequently, as more states passed legislation related to the Faith-based Initiative and created faith-based offices and liaisons, this in and of itself increased the acceptance and legitimacy of such activities – creating legal and cultural changes that legitimated political developments originally argued to be illegitimate and unconstitutional [,].

1.2.5. Movement Outcomes: Acceptance, Inclusion, and New Advantages

Finally, in a classic formulation of movement outcomes, Gamson [] identifies two major categories of successful movement outcomes: acceptance and new advantages. Subsequent scholars have extended and detailed the nature of these outcomes within a political and legislative context. Acceptance in this context “meant some basic acknowledgement by government officials that the challenger was legitimate” ([], p. 463). New advantages include outcomes such as the passage of policies reflecting movement goals, the actual enforcement and implementation of legislated gains, or even just the entry of such legislation into the political agenda []. The outcome of acceptance is often viewed as a critical precursor to substantive legislative victories []. However, Amenta et al. [] note that, because democratic governments usually recognize movements and interest groups as legitimate challengers, scholars have largely moved beyond viewing acceptance as a movement outcome, preferring instead to focus on “a modified version of Gamson’s “inclusion”, or challengers who gain state positions through election or appointment, which can lead to collective benefits” ([], p. 291). As we noted above, the conservative Evangelical movement has been widely acknowledged as being exceptionally successful at both entering and developing an enduring bond with the GOP (Grand Old Party, or Republican Party) []. The movement has achieved an enviable degree of inclusion, but in the specific case of the faith-based initiative, we view the notion of “acceptance” as a movement outcome as pertinent because the basic premise of the initiative is one whose constitutionality was initially uncertain. The initiative gained a major boost in legitimacy when the Bush administration issued several executive orders that allowed states to pursue the creation of liaisons and offices in response to an official federal initiative [,].

In a related vein, we consider it significant that much of the legislative activity at the state-level has been largely symbolic. Since 1995, 132 individual state laws outlined provisions stating that state contracts and agencies should partner with, or include, faith-based organizations. It is important to note that these organizations had in fact partnered with state governments in all fifty states even before such laws were established []. These policies were created not of necessity, but out of a desire to symbolically establish the importance of faith-based social service organizations in the law. Such symbolic policies are consequential due to the signals they send to both those in power and the public [,,]. In their research on congressional hearings, King et al. [] find that attention to rights issues was enhanced by the cumulative number of previous hearings on such issues. They suggest that this is a function of increasing issue legitimacy, where issues or policies with analogous predecessors are more readily assumed to be within the scope of legitimate governmental authority [,]. In the case of policies related to the Faith-based Initiative, we believe that the aggregation of symbolic polices has contributed to establishing and increasing acceptance of religious organizations as legitimate, and in some cases preferred, recipients of government contracts and funds. In fact, many of these symbolic policies are explicitly and specifically concerned with exactly this issue: establishing the status of religious organizations as legitimate recipients or participants.

2. Data and Methods

To explore the determinants of various faith-based policy developments, we used multiple sources of data and statistical approaches. Data on faith-based policies were collected from two main sources. First, data on all legislation related to the Faith-based Initiative were gathered using the LexisNexis search engine. This is a standard tool used in legal research and contains data on all laws passed in every state between 1996 and 2009, including the content of each law passed, as well as its author and date of passage. Using search terms related to the faith-based initiative such as “faith-based” and “charitable choice”, we have compiled a reasonably complete record of legislative implementation related to the Faith-based Initiative. Additional data on state faith-based liaisons was collected from LexisNexis, personal interviews, and the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives. Data compiled from these three sources provide a comprehensive picture of both state faith-based liaison and office creation.

2.1. Types of State Legislation

In this section, we outline the various types of faith-based legislation that states have passed between 1996 and 2009. After detailed examination of over 300 laws, it was determined that the legislation could be divided into roughly nine different categories of laws (provided in Table 1). Broadly, the goal of this varied legislation was to create a new legal culture that would facilitate more openness to faith-based organizations (FBOs). This has been pursued through the passage of what we have categorized here as two types of legislation: symbolic and “concrete”. The nine categories of laws were constructed so as to identify the primary impact of each law. The distinction between symbolic and concrete was made by assessing whether such laws would alter the allocation of resources for, or substantively change, existing policy practices in regards to FBOs. The first type, symbolic laws, are those that suggest states work with FBOs, use language that encourages participation, or create an atmosphere that suggests greater friendliness, without mandating extra participation. This category also includes laws that set up faith-friendly structures such as state administrative boards to work with FBOs. These are not laws that direct action, but rather suggest action.

Table 1.

Type and number of Faith-based Initiative laws benefiting faith-based organizations.

On the other hand, concrete legislation is that which creates greater access for faith-based groups and expands faith-based practices by directing that specific actions be taken. While these laws do not necessarily create an advantage for faith-based groups (although some argue that they might), they do target FBOs for special help and explicit inclusion in the public sphere. These laws include creating funding streams geared toward the state Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives (OFBCI) or other “faith-based efforts”, laws specifically requiring faith-based programs, or laws that require representatives from faith-based groups be appointed to state advisory boards. Table 1 lists the types of laws, the number of each, and whether we have categorized them as symbolic or concrete. In addition, there were a number of bills which were difficult to categorize (regulations regarding tax status) or that would present methodological complications if included in the analyses (those laws creating faith-based offices and liaison positions). The laws concerning tax status regulations are included in counts of total laws, but not those of symbolic or concrete legislation. The pieces of legislation creating faith-based offices and liaison positions are not included in any of the analyses of passed legislation below because the presence of these offices and positions is examined as an independent variable in those models (see Table 2).

Table 2.

State legislation by year. Number of faith-based laws passed by Year (1996–2009).

2.2. Statistical Models and Dependent Variables

In the following, we employ two different statistical approaches on a variety of dependent variables related to implementation of the Faith-based Initiative. Each method allows the exploration of a different type of outcome and different specific research questions.

2.2.1. Event History Analysis

Our first set of analyses examine the factors associated with a greater likelihood of a state creating an OFBCI or a faith-based liaison position. We use discrete time event history analysis [] to analyze longitudinal data on a dichotomous dependent variable indicating whether a state had created an OFBCI or appointed a faith-based liaison in a given year. Once a state had created an office or a liaison position, subsequent observations were removed from the analysis, as the state was no longer at risk of one of these events. Using a variety of techniques, we identified Alaska as an overly influential outlier on a number of variables. We have dropped Alaska from all analyses, resulting in models based on 531 state-year observations.

2.2.2. Multilevel Model for Change

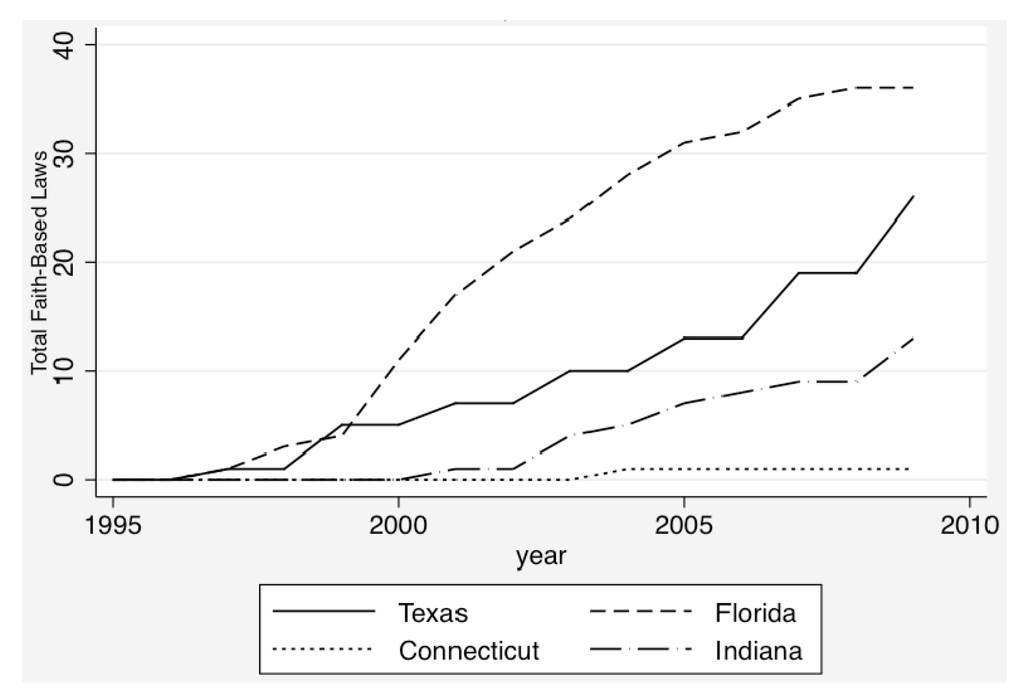

In our second set of analyses, we use a multilevel model for change (MMC), or hierarchical linear modeling for change [], to explore the factors associated with increasing passage of legislation over time. The dependent variable in these analyses is the year-to-year cumulative count of faith-based legislation in each state. Each time a state passes another piece of legislation, the cumulative count increases; this creates a dependent variable that characterizes what can be thought of as trajectories of growth in faith-based legislation. As an illustration, Figure 3 displays trends in this dependent variable within four states: Texas, Connecticut, Florida and Indiana. In the cases of Texas and Florida, there is a clear pattern of consistent passage of new legislation over time. As this modeling strategy may be unfamiliar to some, we will explain the structure of the model in more detail below.

Figure 3.

Cumulative count of faith-based legislation for selected states, 1995–2009.

2.3. Independent Variables

A number of factors may have influenced whether a state implemented particular aspects of the Faith-based Initiative. These include the size of a state’s Evangelical constituency, the local strength of the conservative Evangelical social movement, a state’s political environment, and policy diffusion.

2.3.1. Indicators of Evangelical Social Movement Resources

Measuring the strength of the Evangelical movement at the state level over time has proved to be an exceedingly difficult task. Within the movement, a number of different organizations (such as the Christian Coalition or Focus on the Family) have both risen and faded in influence and prominence over time. The challenges to constructing state-level estimates using membership or organizational data for such groups have proven insurmountable (and to our knowledge have not been overcome elsewhere). Consequently, we utilize a set of measures that do not measure the conservative Evangelical movement directly, but rather are indicators that previous research and social movement theory would lead us to expect to be strongly associated with movement strength: the percent of a state’s population that identifies as Evangelical and the proportion of congregations in a state that are Evangelical.

These measures are drawn from data compiled by the Association of Religious Data Archives that draw upon the 1990, 2000, and 2010 waves of the Religious Congregations & Membership in the United States survey (RCMS) published by the Glenmary Research Center [,,]. These data provide the best subnational estimates of religious adherence by religious tradition currently available []. In addition to the estimated percentage of the state population that identifies as Evangelical, we construct a measure that identifies the proportion of all surveyed congregations that identify themselves as Evangelical. While these two factors are highly correlated, we expect that they might tap different important aspects of both potential movement resources and religious political culture within states. The annual values for these factors, used in the event history analyses, are estimated using a linear interpolation between survey wave years.

Two important limitations to these measures bear mentioning, one empirical and one theoretical. The empirical limitation is that the RCMS suffers from significant undercounts of particular denominations, especially historically African-American denominations []. As such, we consider our measures of Evangelical adherents and congregations throughout as primarily measures of white Evangelical adherents and congregations. The second limitation is that while we expect the number of adherents and congregations to be directly related to the resources upon which the Evangelical movement can and does draw, we cannot distinguish whether the political impact of, for example, a larger proportion of Evangelical state residents is a result of movement activity or political actors responding to, or reflecting, constituent preferences. As this is a rather serious limitation, we will return to this issue in the discussion.

2.3.2. Political Opportunity Structure

Politics-driven policy. We also examine multiple characteristics of the state political opportunity structure. First, we assess the impact of the overall political ideology of a state’s legislature and governor using Berry et al.’s measure of state government ideology3 []. We expect states with more ideologically conservative governments will be more likely to implement legislation related to the Faith-based Initiative. Higher values on this measure indicate more ideologically liberal state governments.

Strength of the Evangelical movement within state Republican parties. It has been widely argued that, broadly speaking, entry into and influence within state Republican parties has been critical to legislative and political success for the conservative Evangelical movement. In order to investigate whether this is true in the specific case of the Faith-based Initiative, we use a variable characterizing the degree of influence and presence of the Evangelical movement within state Republican parties. This index of Evangelical movement influence was developed by Green and his colleagues [,]. Ranging from 1 (least influential) to 5 (most influential), the scale incorporates several measures derived from interviews and other data. In 1994, data were collected from a Campaigns and Elections study that relied upon two types of informants: state-level political insiders and Evangelical movement activists. This study was repeated in similar fashion in 2000. While not perfect, this work provides the only measure of this important aspect of Evangelical movement strength. We expect a stronger degree of influence in state Republican parties will be positively associated with both the institutionalization of, and a higher volume of legislation related to, the Faith-based Initiative.

Problem-driven policy. Advocates for faith-based initiatives are often driven by a genuine desire to facilitate the capacity of faith-based organizations to provide social services to their target populations, often the poor. As such, it is entirely possible that more extensive implementation of the Faith-based Initiative may develop, at least in part, as a response to the severity of poverty within a state. In order to assess this possibility, we include the Census Bureau’s state poverty rates.

The Bush Administration. Finally, in our Event History analyses, we include a dummy variable indicating the years in which the Bush Administration was in office. The Bush administration used multiple approaches to encourage states to create their own faith-based institutions. We expect that this alone significantly increased the likelihood of any state taking such steps.

2.3.3. Second Order Policy Effects

Institutionalization. In our MMC analyses, we also examine the influence that institutionalization of the Faith-based Initiative at the state level may have on subsequent legislative developments. We include a dummy variable indicating whether a state has created a faith-based liaison position or faith-based office. As state liaisons have reported working with governors and state legislators to propose and pass faith-based initiatives, we expect the presence of offices and liaisons to increase the likelihood of adoption of faith-based legislation. In a small number of cases, pieces of legislation were primarily concerned with the creation of a faith-based office or liaison position (most offices and liaison positions were established by governors). In order to avoid artificially inflating the association between legislative passage and the presence of an office or liaison, we have removed these 11 laws from the cumulative count of total legislation4.

Institutional Duration. Furthermore, we expect that newer offices or liaisons may face a greater challenge in overcoming institutional inertia. Conversely, more established offices or liaisons may be more likely to have cultivated the connections, relationships, and institutional legitimacy necessary to get things done. In order to test this, we include a measure of institutional duration, which is the annual count of the number of years since the establishment of a faith-based office or liaison.

Policy Diffusion. The creation of faith-based offices or the passage of faith-based legislation in nearby states may increase the likelihood of a state adopting similar institutions and policies. In order to uncover evidence of state-level diffusion, we examine the impact of the count of contiguous states with faith-based offices or liaison positions within the Event History analyses. In the MMC analyses, we explore the impact of the count of faith-based legislation passed in contiguous states in the previous year on the passage of new legislation in a state.

Policy Legitimacy. Finally, in one set of MMC analyses, we examine whether the aggregation of symbolic legislation within a state increases the likelihood of the passage of more concrete legislation. This variable is operationalized as a state’s cumulative count of symbolic faith-based legislation lagged by one year. Extending King at al.’s concept of issue legitimacy to policies themselves, it may be the case that recurrent passage of such legislation enhances the legitimacy of policy developments in this specific area and in doing so lays the groundwork for more substantive, if initially controversial, legislation. However, it may also be the case that symbolic legislation may be passed as a substitute for concrete action, as was suspected by some in the case of the Faith-based initiative [,,].

2.4. Control Variables

In addition to these theoretically relevant variables, policy research suggests that particular socio-demographic and economic characteristics of states should be taken into account [,,].

Economic. States with fewer economic resources may be less likely to appoint faith-based liaisons or create offices, as such innovations may be perceived as too costly []. This factor is included as a control in all models, in the form of real state revenue per capita. Revenue data are from the Statistical Abstract of the United States [].

Religiosity. Second, we control for the overall level of religiosity in a state with a measure of estimated total religious adherents (to any religion) in a state relative to the state population. We expect that states with larger proportions of religious adherents may be more supportive of faith-based policies regardless of the efforts of Evangelical movement actors. In order to control for this possibility, we include this variable in all models. These data are also drawn from the Religious Congregations & Membership in the United States survey and are interpolated between survey wave years (1990, 2000, and 2010).

3. Results

3.1. Event History Analyses

Institutional Impacts: The Creation of Faith-Based Offices and Liaisons

This first set of analyses examines the state-level factors associated with the creation of either a faith-based office or liaison position. Table 3 contains the results of six Event History models. The first four models are reduced models examining the impact of a variety of movement and political factors individually in models containing only control variables. Our full models 5 and 6 include all factors and introduce our two highly correlated measures of Evangelical movement resources separately. Within both of these full models, the following factors are significantly associated with an increased likelihood of state creation of an office or liaison: the variable characterizing the influence of the Christian Right in the state Republican Party, the Bush administration dummy variable, and our measure of policy diffusion. It is noteworthy that, controlling for other factors, neither the size of a state’s Evangelical community in terms of adherents or organizational presence appear to be significantly related to whether a state established a faith-based office or liaison. Indeed, the only characteristic internal to states related to this outcome is the strength of movement actors within the state Republican Party. The two remaining factors, the Bush Administration dummy and the diffusion variable, both capture pressures and processes originating outside of states.

Table 3.

Event History Analysis of State Creation of a Faith-Based Liaison Position and/or Office of Faith-Based Community Initiatives: 1998–2007 *.

The Bush administration dummy variable is the single most influential factor in these analyses indicating that the odds of any state creating an office or liaison were nearly nine times higher following the 2000 election. The second most influential factor is the Christian Right influence variable, which ranges from 1 (weak influence) to 5 (great influence). The results of Model 6 indicate that states in which the Christian Right are characterized as having great influence on the state Republican Party have an estimated odds of creating an office or liaison that is three times larger than those in a state with weak Christian Right influence. Finally, the odds of a state creating an office or liaison when two neighboring states have done so are roughly 50% higher than a state with no such developments in contiguous states.

In summary, beyond the nationwide promotion of the creation of faith-based institutions by the Bush administration, the strength of the Christian Right within Republican state parties and policy diffusion appear to be the central drivers of state adoption of faith-based offices and liaison positions.

3.2. Multilevel Model for Change Analyses

3.2.1. Legislative Impacts: The Passage of Faith-Based Legislation

In the following set of analyses, we explore the factors influencing trajectories of change in the cumulative count of state faith-based legislation using a multilevel model for change. We find this approach both appropriate and highly useful for a number of reasons. First, this approach allows us to examine whether developments within states over time, such as the creation of faith-based institutions or shifts in the ideological composition of state governments, are associated with legislative outcomes. Simultaneously, we can assess whether relatively stable state characteristics, such as the proportion of Evangelicals in a state, drive substantially different overall trends of legislative activity between states. This is important, as we do not expect within-state variation in such factors to matter, that is, minor changes over time in the percent of Evangelical residents are not expected to drive trends. Rather, it is the influence of stable differences across states that are of interest. Such assessments are not possible in the context of either fixed-effects or first-differenced time series approaches, which are often used to examine legislative outcomes5.

In this two-level model, states are the larger, level II units and the cumulative counts of state legislation over time are the level I units. The level I model describes how states change over time, while the level II model describes how these changes vary across states []. The following is our level I model for cumulative faith-based legislation, Y, for each state s at time t:

Yts = π01 + π1sTIMEts + π2sOFFICEorLIAISONts + π3sGOVIDEOts +… … πqsXqts + ets.

Annual state levels of cumulative legislation are a function of an intercept (π01, the grand mean of cumulative legislation across states when all predictors are set to mean values), TIME (π1s), the presence of a state OFBCI or liaison (OFFICEorLIAISON) at time t (π2s), while controlling for other variables included in the level I analysis (πqs).

Using only time-varying independent variables, the level I analysis attempts to explain within-state year-to-year change in state faith-based legislation. Specifically, given the construction of the dependent variable as a cumulative count, the variable will either stay the same year-to-year, meaning no passage of legislation, or it can increase indicating the passage of legislation. The level II analysis, on the other hand, utilizes a set of time-invariant independent variables and examines the manner in which largely stable state characteristics predict the value of both the intercept and the slope of an individual state’s entire trajectory of change in cumulative legislation over the period examined. The outcome variables in the level II model are the π parameters from the level I model:

For example, we hypothesize that states with a stronger Christian Right influence in state Republican parties will experience more substantial increases in cumulative faith-based legislation over the entire 1996–2009 period.

The level II model assesses factors that impact initial values (the intercept) and rates of increase or decline in the dependent variable over the entire period examined (literally, the slopes in Figure 3). In 1996, no state had passed any faith-based legislation. As a consequence, the initial values, or the intercept for the MMC model, for all states is zero. As such, we will not be examining or discussing determinants of initial values in the following. The trajectory of change in total legislation for each state over the entire period examined is characterized in π1s and is regressed upon a measure of Christian Right party influence (CRSTRENGTH) and a vector “Xqs” of our other time-invariant predictors. The other time-invariant variables in the following analyses, all in the form of their average over the period studied, are % white Evangelical, % congregations Evangelical, and % religious adherents.

3.2.2. Determinants of Year-to-Year Change in Total Faith-Based Legislation

Models 1–5 in Table 4 present our reduced models that contain all control variables and introduce each independent variable individually. Models 6 and 7 are our full models that contain all variables and introduce our correlated measures of Evangelical strength individually. First, we discuss the variables that are examined at level I of the models, those which predict change year-to-year in cumulative legislation.

Table 4.

MMC Analysis of Cumulative Faith-Based Legislation on State Charateristics: 1996–2009.

Beginning with our measure of institutionalization, we find that annual change in legislation is strongly influenced by the presence of either a state OFBCI or the presence of a faith-based liaison. Based on an examination of the predicted values for Model 66, a hypothetical state with average values on all variables and an office or liaison would pass roughly two more pieces of faith-based legislation every three years than an identical hypothetical state lacking an office or liaison. In addition, the likelihood of a state passing legislation increases substantially the longer a state has had a faith-based office or liaison. We can only speculate on the mechanisms driving this effect. This may represent some combination of faith-based liaisons deepening their relationships with legislators, finding ways to overcome institutional inertia, or a consequence of the increasing institutional legitimacy of more longstanding offices or liaisons. We should mention that these two measures, presence of an office or liaison and the number of years such offices or positions have existed, are unavoidably highly correlated. However, both factors consistently remain highly statistically significant (p < 0.000), and have nearly identical impacts, in the absence of one another in both full and reduced models.

Turning to one aspect of a state’s political context, we find that states with more conservative state governments are more likely to pass legislation year-to-year. Finally, our diffusion variable (total faith-based legislation passed in contiguous states as of the previous year) is highly significant, indicating that states with neighbors that are actively pursuing a faith-based legislative agenda are more likely to pass such legislation themselves.

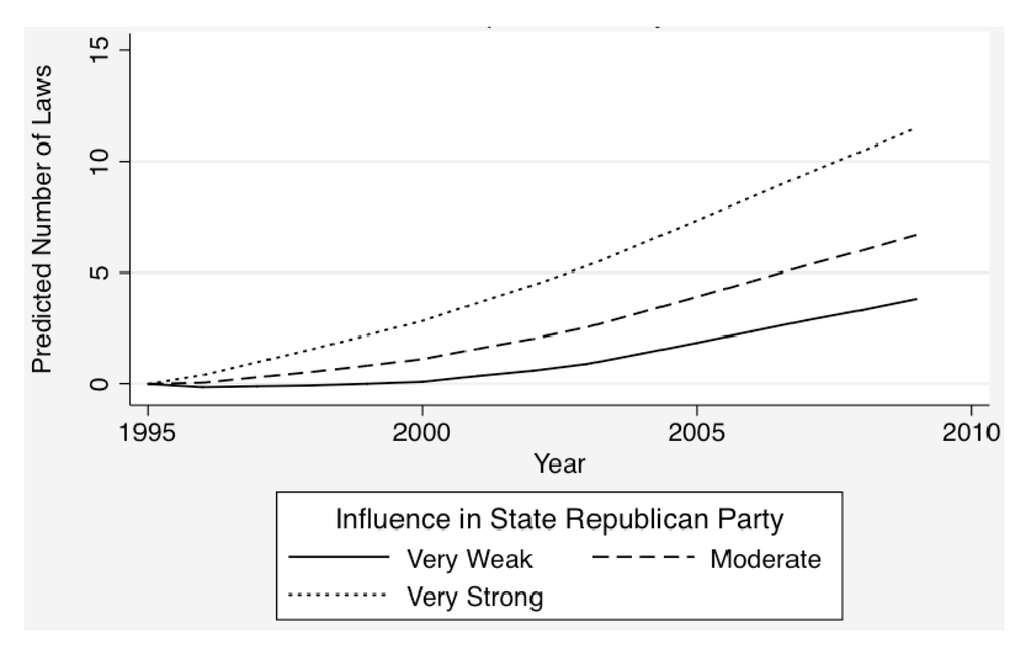

3.2.3. Determinants of Overall Trends in Total Faith-Based Legislation

Of the level II variables examined, only one factor emerges as significantly influential of overall trajectories of change in cumulative legislation consistently across models: the strength of the Christian Right within the state Republican Party. Using the coefficients from Model 6, Figure 4 displays the predicted values of cumulative legislation for three states where the Christian Right has very weak, moderate, and very strong influence within the state Republican Party (all other variables set to mean values). The magnitude of this effect suggests that this factor is one of the most influential in these analyses.

Figure 4.

Predicted cumulative faith-based legislation for states containing Christian right social movements with weak, moderate, & strong influence within the State Republican Party

The only other level II variable that is significant in any model is the percent of state congregations that are Evangelical (reduced Model 3). This suggests, as expected, that states with larger numbers of Evangelical congregations have passed more faith-based legislation. The proportion of Evangelical congregations is positively correlated with Christian Right influence in state Republican parties (r = 0.61). Not surprisingly, on average, the Christian Right has more influence in Republican parties in states where there is a larger Evangelical presence. In order to assess the extent to which this collinearity is impacting these estimates, models 6 and 7 were run omitting the Christian Right party influence variable (see Model 2, Table 5). These models indicate that, controlling for non-collinear factors, the measure of Evangelical congregations is highly significant and positively associated with a larger volume of faith-based legislation in the absence of the state Republican Party influence variable. Overall then, states with larger proportions of Evangelical congregations and more Evangelical influence in state Republican parties are more likely to pass legislation, and, in many cases, these are the same states7.

Table 5.

MMC Analysis of Cumulative Total, Symbolic, and Concrete Faith-Based Legislation on State Charateristics: 1996–2009.

3.2.4. Determinants of Trends in Total Symbolic and Concrete Faith-Based Legislation

In our final set of analyses, we examine the determinants of two different dependent variables: total cumulative symbolic and total cumulative concrete faith-based legislation. Models 3–7 in Table 5 examine these dependent variables. Model 1 in Table 5 is Model 6 from Table 4. Model 2 is Model 7 from Table 4 with the collinear Evangelical influence variable dropped, both provided for comparison. In all models, we find that the presence of an office or liaison is significantly associated with year-to-year increases in both symbolic and concrete legislation. Also consistent across models is the finding that the passage of faith-based legislation is more likely the longer an office or liaison has been established. Similarly, in all but Model 7, more ideologically conservative state governments are more likely to pass faith-based legislation of either type.

There are a number of noteworthy differences in the factors that are significantly associated with symbolic and concrete legislative outcomes. In the absence of one another, the measures of Evangelical congregations and Evangelical influence in Republican parties are significantly associated with a larger volume of both total and symbolic legislation, but not with concrete legislation (although % Evangelical congregations is significant at the level of a one-tailed test in Model 6). Similarly, our measure of policy diffusion is significantly associated with a higher volume of symbolic, but not concrete legislation (in this case, the diffusion variable indicates whether the passage of symbolic legislation in neighboring states is associated with the passage of symbolic legislation within states, and the same for concrete legislation). This reveals that the significant effects of policy diffusion, Evangelical congregations, and Evangelical party influence on total legislation are primarily driven by patterns of adoption of more symbolic legislation. On the other hand, the adoption of more concrete legislation appears to be determined primarily by characteristics of state governments, specifically their ideological composition and the presence and longevity of faith-based institutions.

There may be multiple reasons for this. One interpretation is that symbolic policies offer a low-risk (and no cost) way for politicians to signal affiliations or support for particular constituencies. As such, the political calculus surrounding support for symbolic policies is likely distinct from that associated with more substantive legislation. In addition, it is often the case that more substantive legislation is more controversial and correspondingly more difficult to pass. The combination of political conditions necessary to pass such legislation do not necessarily line up neatly with state-level indicators of social movement strength or patterns of policy diffusion. Alternatively, these results are consistent with a scenario in which the efforts of faith-based liaisons, and their offices are the central driver of the passage of more concrete legislation, a task made easier in the context of more ideologically conservative governments.

Finally, in Model 7, one additional independent variable is added to these analyses: a state’s cumulative count of symbolic faith-based legislation lagged by one year. We include this model to investigate a final question: does the passage of symbol legislation increase the likelihood of subsequent passage of concrete legislation? This variable is highly significant and positive indicating that year-to-year states that have previously passed more symbolic legislation are more likely to pass concrete legislation. We interpret this as an indication that the recurrent passage of symbolic legislation enhances the legitimacy of policy developments related to faith-based initiatives and consequently increases the likelihood of subsequent adoption of more substantive legislation.

4. Discussion

In the big picture, these results identify where and when states were more likely to pass measures that implemented the conservative Evangelical movement goals of reshaping church/state relationships and fostering the devolution of the welfare sector to religious groups. Our findings suggest that both institutional activism and the creation of movement-inspired state institutions have been extremely effective means of pursuing these outcomes. We find in these analyses a direct effect of elite movement actors on the passage of legislation. States where the Evangelical movement has made the biggest inroads into state Republican parties have passed a larger volume of faith-based legislation. These states are also more likely to create state faith-based offices and liaisons institutionalizing access and attention to a set of movement issues. In both sets of analyses, patterns of state creation of faith-based institutions and the passage of faith-based legislation are better predicted by the degree of influence held by movement actors within state Republican parties than the composition of states’ religious communities. Once established, the presence of these liaisons and offices has resulted in an enduring increase in the likelihood of the subsequent passage of faith-based legislation. Transforming the political opportunity structure itself, this partial outsourcing of movement activity to the state results in second order policy effects that subsequently further movement goals.

We also find that another self-reinforcing dynamic, diffusion, has greatly aided the expansion of the Faith-based Initiative. In addition to the top-down diffusion process captured in the Bush administration’s appeal to governors nationwide to create OFBCIs, states were more likely to both create office and liaison positions and pass symbolic faith-based legislation if their neighbors were doing so. In this context, we think it is reasonable to consider the diffusion of institutions and policies, in part, as a second-order policy outcome. Again, given the real concerns about the constitutionality of early legislative efforts related to the Faith-based Initiative, the existence of policies and institutions elsewhere provides assets, in terms of both practical models and policy legitimacy, to movement actors attempting to garner support for similar policies.

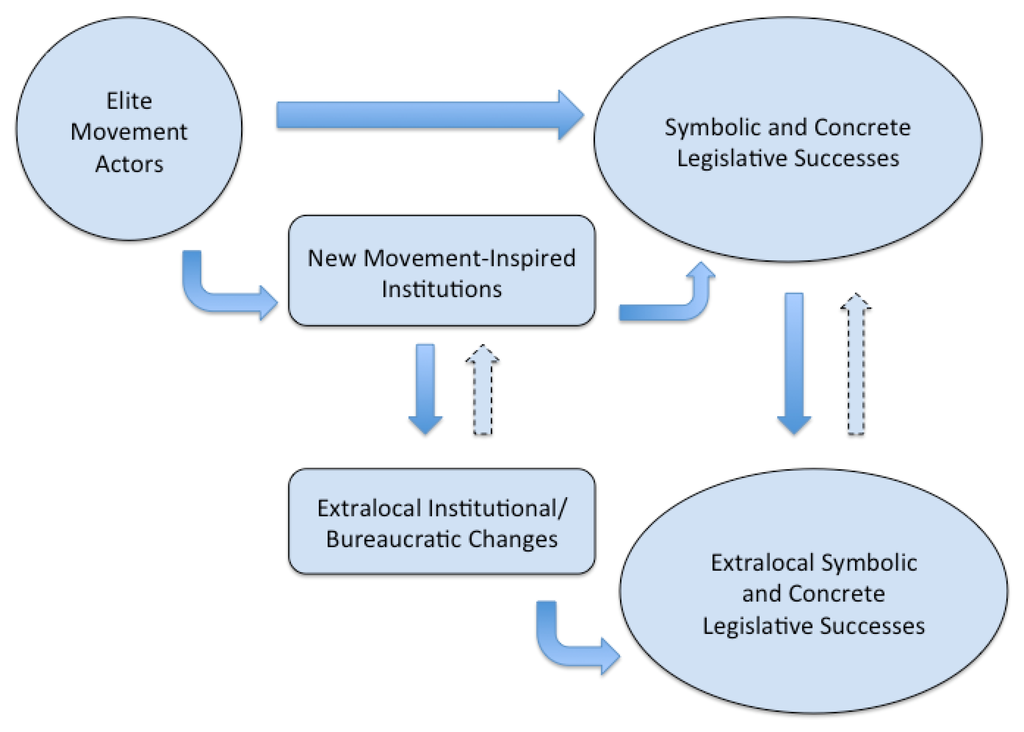

Finally, we find the previous passage of symbolic faith-based legislation is associated with a greater likelihood of subsequent passage of concrete policy outcomes. The passage of these initial unfunded, suggestive, and symbolic policies were viewed by many as low risk political pandering to the conservative religious base []. However, our findings suggest that these policies have had a very real impact, significantly reshaping political culture in regards to the legitimacy of church-state interactions in the domain of social services. In Gamson’s [] classic terms, symbolic policies have won increased acceptance of FBOs as legitimate potential recipients of funds and laid the groundwork for subsequent actual receipt of this new advantage. Perhaps most interesting is the fact that while indicators of Evangelical movement strength and influence are not directly associated with the adoption of more concrete legislation, they are strongly related to the creation of faith-based institutions and the passage of more symbolic legislation, both of which are among the very few factors which increase the likelihood of passage of more concrete legislation (see Figure 5). More substantive policy outcomes are then a second order outcome resulting from institutionalization of movement goals and actors and enhanced policy legitimacy via the recurrent passage of symbolic legislation.

Figure 5.

Model of long-term and second order policy impacts.

5. Conclusions

While movement actors and allies were clearly successful in the years examined here, what is perhaps more surprising is how much of the initiative remains. At the national level, the renamed White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships has continued under the Obama administration to partner with faith-based groups in the hopes of expanding their social service work. While the name change highlighting the more formal inclusion of community groups has been viewed as a signal to Evangelicals that they no longer dominate the White House agenda, Obama has still not rescinded Bush’s order on allowing religious groups to discriminate in hiring even when receiving federal funds (perhaps the most important legal decision impacting church/state relations from either president). Both of these actions suggest that the changes made to church/state relationships under Bush administration have not been fully diminished. Additionally, over twenty states still maintain state offices of faith-based initiatives that have pursued a variety of efforts to bring religious groups into greater partnership with government agencies, with two states, Delaware and Arizona, either creating or further codifying their offices after President Bush left office. While several states, such as Alaska and Minnesota, have closed their faith-based offices, the vast majority remains, and both the ideas and bureaucracy of the faith-based initiative have continued largely intact at the state and federal level.

The influence of the Evangelical movement has been widespread, impacting not only faith-based policy, but also a wide range of policy domains including education, marriage, health policy, and reproductive rights. These successes have been achieved through the use of a diverse set of both noninstitutional and institutional tactics, and, especially through effective utilization of an existing political institution, the Republican Party. The effectiveness of this institutional activism is rivaled only by the successes associated with the creation of new government institutions tasked with pursuing movement goals. While this tactic may have been utilized in an exceptionally consequential manner in the case of the Faith-based Initiative, access gained through new institutions is not unique to the Evangelical movement and is, in our opinion, an underdeveloped area in our understanding of long-term policy outcomes. Attention to the longer-term second order impacts of policy developments requires taking a perspective on policy outcomes that is both long-term and multifaceted. We expect such a perspective to be valuable for understanding developments in other policy arenas in which the Evangelical movement has focused its efforts and a broader set of policy achievements by the contemporary conservative movement writ large.

Author Contributions

Rebecca Sager and Keith Bentele contributed equally to the preparation and writing of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mark Chaves. Congregations in America. Boston: Harvard University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wuthnow. Saving America? Faith-Based Services and the Future of Civil Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Chaves. “Religious Congregations and Welfare Reform: Who Will Take Advantage of the Faith-Based Initiatives? ” American Sociological Review 64 (1999): 836–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecca Sager. Faith, Politics and Power: The Politics of Faith-Based Initiatives. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wineburgm, Brian Coleman, Stephanie Boddie, and Ram Cnaan. “Leveling the Playing Field: Epitomizing Devolution through Faith-Based Organizations.” Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 35 (2008): 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Derek H. Davis. “George W. Bush and church-state partnerships to administer social service programs: Cautions and concerns.” In Religion and Social Problems. Edited by Titus Hjelm. New York: Routledge, 2011, Available online: http://site.ebrary.com/id/10447670 (accessed on 1 January 2015).

- Michael Lindsay. Faith in the Halls of Power: How Evangelicals Joined the American Elite. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Lindsay. “Evangelicals in the Power Elite: Elite Cohesion Advancing a Movement.” American Sociological Review 73 (2008): 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidney Tarrow. Power in Movement. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Charles Colson, and Nancy Pearcy. How Now Shall We Live? Carol Stream: Tyndale House, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph Loconte. “Keeping the Faith.” First Things 123 (2002): 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin Olasky. Renewing American Compassion: How Compassion for the Needy Can Turn Ordinary Citizens into Heroes. New York: Free Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- David Kuo. Tempting Faith: An Inside Story of Political Seduction. New York: Free Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Helen R. Ebaugh. The Faith-Based Initiative in Texas: A Case Study, Report of the Roundtable on Religion and Social Welfare Policy. Albany: Rockefeller Institute of Government, State University of New York, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jo Renee Formicola, Mary C. Segers, and Paul Weber, eds. Faith-Based Initiatives and the Bush Administration: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

- Robert Wineburg. A Limited Partnership: The Politics of Religion, Welfare, and Social Science. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- John Bartkowski, and Helen Regis. The Faith-Based Initiatives: Religion, Race, and Poverty in the Post-Welfare Era. New York: New York University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- John Bartkowski, and Helen Regis. “Religious Civility, Civil Society, and Charitable Choice: Faith–Based Poverty Relief in the Post–Welfare Era.” In Faith, Morality, and Civil Society. Edited by Dale McConkey and Peter Lawler. Lexington: Lanham, Md., 2003, pp. 132–48. [Google Scholar]

- Roger Finke, and Christopher Scheitle. “Accounting for the Uncounted: Computing Correctives for the 2000 RCMS Data.” Review of Religious Research 47 (2005): 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark Ragan, and David Wright. Scanning the Policy Environment of Faith-Based Social Services in the United States: What Has Changed Since 2002? Albany: Rockefeller Institute of Government, State University of New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth D. Wald, and Jeffrey C. Corey. “The Evangelical Movement and Public Policy: Social Movement Elites as Institutional Activists.” State Politics and Policy Quarterly 2 (2002): 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles Tilly, and Sidney Tarrow. Contentious Politics. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sidney Tarrow. “‘The Very Excess of Democracy’: State Building and Contentious Politics in America.” In Social Movements and American Political Institutions. Edited by Anne Costain and Andrew McFarland. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 1998, pp. 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chip Berlet, and Matthew Lyons. Right-Wing Populism in America: Too Close for Comfort. New York: Guilford Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Robert D. Woodberry, and Christian S. Smith. “Fundamentalism et al.: Conservative Protestants in America.” Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1998): 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberly Conger. A Matter of Context: Christian Right Influence in State Republican Parties. Ames: Iowa State University, 2008, Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly Conger, email text “Moral Values Issues and Policy Party Organizations: Cycles of Conflict and Accommodation of the Christian Right in State-Level Republican Parties” to author, 2008.

- Kimberly Conger, and John Green. “Spreading out and Digging in: Christian Conservatives and State Republican Parties.” Campaigns and Elections Magazine, 28 February 2002. [Google Scholar]

- David Domke, and Kevin Coe. The God Strategy: How Religion Became a Political Weapon in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- John C. Green, James L. Guth, and Clyde Wilcox. “Less Than Conquerors: The Christian Right in State Republican Parties.” In Social Movements and American Political Institutions. Edited by Anne Costain and Andrew McFarland. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 1998, pp. 117–35. [Google Scholar]

- John Green, Mark Rozell, and Clyde Wilcox. The Evangelical Movement in American Politics: Marching to the Millennium. Washington: Georgetown University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth Andrews. “Social Movements and Policy Implementation: The Mississippi Civil Rights Movement and the War on Poverty, 1965 to 1971.” American Sociological Review 66 (2001): 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timo Bohm. “Activists in Politics: The Influence of Embedded Activists on the Success of Social Movements.” Social Problems 62 (2015): 477–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne A. Santoro, and Gail M. McGuire. “Social Movement Insiders: The Impact of Institutional Activists on Affirmative Action and Comparable Worth Policies.” Social Problems 44 (1997): 503–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher Scheitle, and Bryanna Hahn. “From the Pews to Policy: Specifying Evangelical Protestants Influence on States Sexual Orientation Policies.” Social Forces 89 (2011): 913–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John F. Persinos. “Has the Christian Right taken over the Republican Party? ” Campaigns & Elections 15 (1994): 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Burstein, Rachel L. Einwohner, and Jocelyn A. Hollander. “The Success of Political Movements: A Bargaining Perspective.” In The Politics of Social Protest. Edited by J. Craig Jenkins and Bert Klandermans. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995, pp. 275–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sarah Soule. “The Student Divestment Movement in the United States and the Shantytown: Diffusion of a Protest Tactic.” Social Forces 75 (1997): 855–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah Soule, and Yvonne Zylan. “Runaway Train? The Diffusion of State-Level Reform in ADC/AFDC Eligibility Requirements, 1950–1967.” American Journal of Sociology 103 (1997): 733–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil Gross, Thomas Medvetz, and Rupert Russell. “The Contemporary American Conservative Movement.” Annual Review of Sociology 37 (2011): 325–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark Chaves, and William Tsitsos. “Congregations and Social Services: What They Do, How They Do It, and with Whom.” Non-Profit Voluntary Sector Quarterly 30 (2001): 660–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Wineburg. Faith-Based Inefficiency: The Follies of Bush’s Initiatives. Westport: Greenwood, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- William Gamson. The Strategy of Social Protest. Homewood: Dorsey, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Edwin Amenta, Neal Caren, Elizabeth Chiarello, and Yang Su. “The Political Consequences of Social Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (2010): 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwin Amenta, and Neal Caren. “The Legislative, Organizational, and Beneficiary Consequences of State-Oriented Challengers.” In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. Edited by David Snow, Sarah Soule and Hanspeter Kriesi. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004, pp. 461–89. [Google Scholar]

- John Micklethwait, and Adrian Wooldridge. The Right Nation: Conservative Power in America. New York: Penguin, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Amy Black, Douglas L. Koopman, and David K. Ryden. Of Little Faith: The Politics of George W. Bush’s Faith-Based Initiatives. Washington: Georgetown University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- George W. Bush. “Executive Order 13199 of January 29, 2001: Establishment of White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives.” Federal Register 66 (2001): 8499–50. [Google Scholar]

- Murray Edeleman. The Symbolic Use of Politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Murray Edeleman. Politics as Symbolic Action. Chicago: Markham, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Deborah Stone. The Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making. New York: Norton, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Brayden King, Keith Bentele, and Sarah Soule. “Protest and Policymaking: Explaining Fluctuation in Congressional Attention to Rights Issues, 1960–1986.” Social Forces 86 (2007): 137–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy B. Peters. American Public Policy: Promise and Performance. London: Chatham House Publishers, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Allison. Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide. Cary: SAS Institute, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Judith Singer, and John Willett. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Martin B. Bradley, Norman M. Green Jr., Dale E. Jones, Mac Lynn, and Lou McNeil. Churches and Church Membership in the United States. Nashville: Glenmary Research Center, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Glenmary Research Center. Religious Congregations Membership Study 2000. Cincinnati: Glenmary Home Missioners, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford Grammich, Kirk Hadaway, Richard Houseal, Dale E. Jones, Alexei Krindatch, Richie Stanley, and Richard H. Taylor. 2010 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations & Membership Study. Nashville: Glenmary Research Center and the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (ASARB), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- William D. Berry, Evan J. Ringquist, Richard C. Fording, and Russell L. Hanson. “Measuring Citizen and Government Ideology in the American States, 1960–93.” American Journal of Political Science 42 (1998): 327–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleen Grogan. “Political and Economic Factors Influencing State Medicaid Policy.” Political Research Quarterly 47 (1994): 589–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Nice. Policy Innovation in State Government. Ames: Iowa State Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- “U.S. Census Bureau. 1993–2006. Statistical Abstracts. ” Available online: http://www.census.gov/prod/www/abs/statab.html (accessed on 1 January 2011).

- Sarah Soule, and Susan Olzak. “What Is the Role of Social Movements in Shaping Public Policy? The Case of the Equal Rights Amendment.” American Sociological Review 69 (2004): 473–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1While the White House no longer tracks offices, the majority of states that created faith-based offices have maintained those offices or have maintained some level of faith based bureaucracy within the government. Twenty-three states currently with faith-based offices or liaisons in various agencies are: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Illinois, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Virginia. There are very likely additional liaisons, however, without a singular agency tracking liaisons their identification is significantly more difficult.

- 2Currently, 23 of these states still have offices; however, it is unclear how many still have liaisons since many liaisons are in a variety of government offices, and the White House is no longer tracking which states have liaisons.

- 3This measure was created using the roll call voting records of state legislators, the partisan divisions of the elected bodies, the outcomes of congressional elections, and the party of the state governor [].

- 4Our institutionalization dummy variable indicates the presence of an office or liaison in the year after the passage of such legislation. We also ran these analyses including these 11 laws and find that the results are identical in all substantive respects.

- 5In addition, pooled cross-sectional analyses often raise serious problems in terms of high levels of autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity, both of which are present in these data. The error structure of the MMC model allows residuals to be both autocorrelated and heteroskedastic within the larger level II units (states, in this analysis), which allows more efficient use of the data []. Finally, one key assumption of the MMC is that unobserved panel level effects are not related with the variables in the analyses. Using a Hausman test, it was determined that that this assumption is satisfied in the dataset and the use of an MMC approach is appropriate.

- 6This is the full model with the best fit in these analyses.

- 7Given the high collinearity between these two variables, we cannot adjudicate between or assess the relative contributions of these two factors. However, across a wide range of models and while controlling for other indicators of Evangelical movement strength, the Evangelical party influence variable consistently emerges as a better predictor of faith-based legislative activity.

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).