Moral and Cultural Awareness in Emerging Adulthood: Preparing for Multi-Faith Workplaces

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. Religiosity, Spirituality, and Morality in the Workplace

2.2. Modernity, Morality, and Religiosity

2.3. Generational Changes and Emerging Adulthood

2.4. Moral Development

2.5. Moral and Cultural Awareness

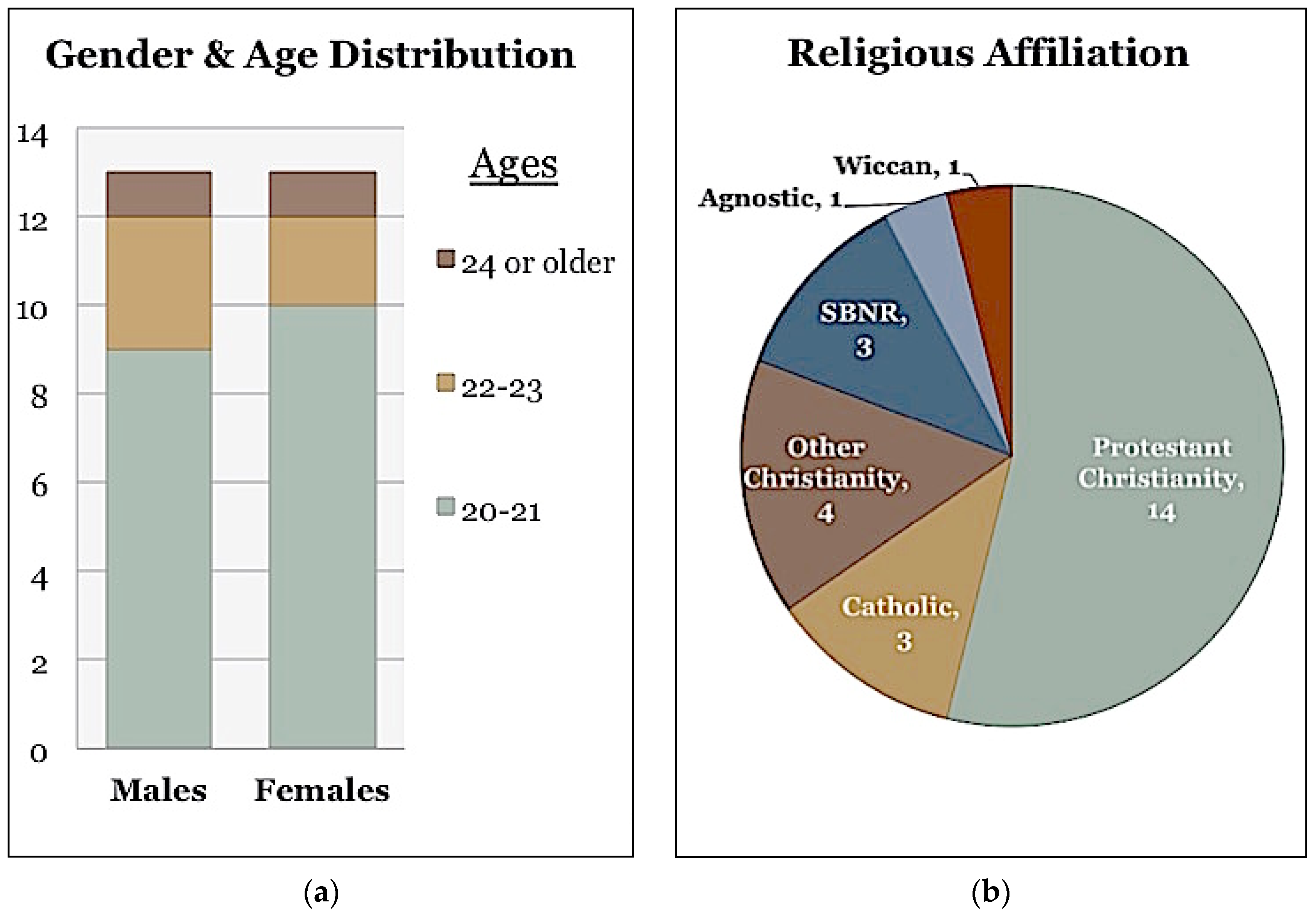

3. Methodology

3.1. National Comparison

3.2. Control Comparison

4. Results

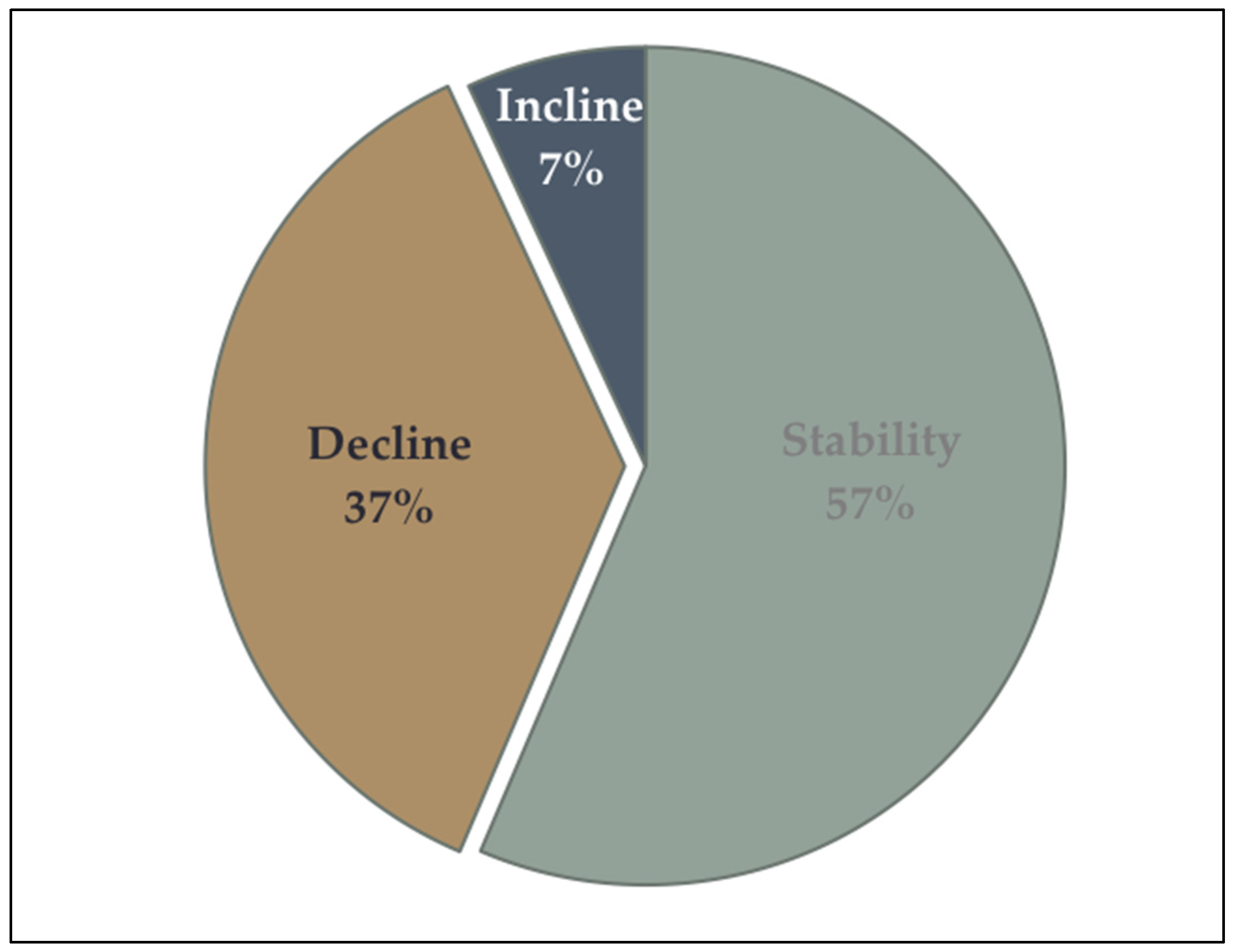

4.1. Control Group Changes

4.2. Personal Mission Statements

Another example of a personal mission statement, and one that evidences a connection between pre-defined moral values and potential changes to ethical decision-making, is:[My mission is] being an authentic, genuine and reliable leader that others can admire, look up to and aspire to be. Establish and create a work environment that is welcoming and accepting of all people who come from different backgrounds, experiences and walks of life. Challenge myself to seek opportunities to try or learn something new as often as possible. Vow to surround myself with individuals different from myself, ask questions and search for answers in order to cultivate growth.

While the data for this study are collected while students are still in college, the personal mission statements written by students often evidenced the potential for the preparations of this course to impact the kind of work they will do once employed, especially by this student about to graduate:To choose the ethical approach by making a personal commitment to honesty and integrity. To find opportunities to use my natural talents such as patience, self-control, sincerity, and logic through my job as a CPA. To strive to be worthy of the respect and admiration of family, friends, and business associates. To find happiness, fulfillment, and value in living.

Many students explicitly religious based moral values in their personal statements, as exampled:I will be a positive force in the lives of others by taking time to get to know those who cross my path and helping them in any way that I can. I will not ask anything of anyone that I am not willing to do myself. I have an opportunity to apply these principles in the managerial position I am starting at the end of this month. One of my goals is to advance in my career so that I can touch the lives of as many people as possible. Another goal is to continuously improve myself, and to help others improve themselves.

In other cases, students who expressed having high levels of religiosity in their survey did not write their personal mission statements in ways that were explicitly religious, as evidenced here:I want my life, as seen by others and my creator, to exemplify the servant leadership, joy, and grace that Jesus showed the world.

Honesty—being truthful with others but most importantly myself. Healthy—keeping a healthy mind and body is very important. Humble—having respect for others and never seeing myself as boastful. Transparency—staying open and honest with myself and others Self-knowledge—strive to know who I truly am. PMS: I will strive to create my own path to happiness, not follow others’ paths, while surrounding myself with people who sharpen me into a stronger more sophisticated individual, and to one day leave a legacy for my family and children.

4.3. Student Descriptions of Course Impacts

Additionally exemplified in the above quote, is a recurrent theme of students reporting learning about other religions with which they had minimal or no prior exposure. For example, on student stated:This class helped me grow as a person. One of the reasons I took this class was to learn about other religions and how to interact with them, be more accepting, and be able to understand where they are coming from.

Some students explicitly tied these increases in cultural awareness of diverse religions to gains in workplace skills. This student, for instance, describes a new ability for teamwork:I was very interested in the idea of learning more about the world religions and how they hold power over the hearts and minds of so many people. In doing so I had hoped to strengthen my own beliefs as well. I feel as though I have accomplished both of these initiatives. Learning from the many speakers we have had has been incredibly insightful. The Buddhist monk was especially interesting to me. His illustration of Logic and reason as a sort of salvation from the world was incredible. While I disagree with him in this it was an amazing experience to hear from him about his beliefs. I wish that I had more time to talk with him, but I am grateful for the time he provided to us.

In describing what particular aspects of the course facilitated changes in their moral awareness, students often described improvements from the process of writing and reflection, such as this:For strictly religious individuals without this concept, it is difficult to respect others who do not share similar beliefs because these people do not understand that values can be similar for people with different beliefs. I had this problem coming into this class. With this thought, a multi-faith team would rarely accomplish anything. Their conversations would continuous revolve around beliefs that are much less likely to change as opposed to values. Understanding this concept will assist me as an authentic leader with diverse teams.

Increases in cultural awareness were alternatively linked to guest speakers from diverse religions:The journal posts, especially about the different religions really helped me to write my thoughts down as well as teach me about other religions. I found that I agreed with a lot of the teachings of other religions. I think that Huston Smith’s chapter about Hinduism had the biggest impact on me, as well as on my mission. I liked that the Hindu religion taught people to do what they desired and that everything anyone gets is well deserved. I have always believed that what goes around comes around, and this “motto” if you will, helped me to develop my first draft of my mission. I always have and always will want to help others. I want to make the best impression I can on each person I meet and always respect others.

Some students described how these increases in cultural awareness improved their emotive skills:Another big part of our class this semester were the guest speakers, and honestly at first I wasn’t sure what to expect from these times, but I found myself very enthralled by what they had to say and was propelled with that knowledge…Being familiar with other religions is a great tool to have, to be well rounded instead of ignorant.

Others described gains in the cognitive, logical processing skills from the moral awareness efforts:Hearing about the views and beliefs of people who were raised in different cultures opened my eyes. The two Buddhist speakers relayed the importance of happiness in life and the potential rewards for having control over our thoughts. Differentiating between feeling angry and admiring feelings of anger rising can make all of the difference in our lives. If I can start to notice when anger or sadness is rising within me, then I can faster take control of those feelings so that I will not be as affected by them.

Relating the different course tasks to each other was described by some students as providing deeper impact through applying the learning into expressed practices. For example:The lectures helped to define and differentiate between faith, religion and spirituality. In my mind I had always assumed that these ideals were relatively all the same and could be used interchangeably. I had never grasped the true meaning behind these words and what they stood for. Through the lectures I was better able to recognize the differences and understand how I apply each of them to my life. I used to attribute faith to a theistic belief, but I have learned that it is our “overarching, integrating and grounding trust in a center of value and power which enables us to find coherence and meaning.”

In summary, many students described the kind of in-depth changes this course was designed to create, and quite a few were able to explicitly link the content of the course to the kind of workplace leader they want to be after completing the course and graduating. As one student eloquently said:While practicing difficult conversations, I discovered that having a personal mission statement will really help me in business practice. With these tricky situations, if someone had asked why I believe what I do, I would have never been able to definitively explain. Now, because I have a mission statement, I know how to articulate my values and express why I believe one way or another. The mission statement will help me not only in dealing with difficult conversations, but in my business career as a whole.

As these quotes evidence, one of the aspects of the course that had the greatest impact was exposure to multiple faiths via speakers who were devout in each of the five wisdom traditions and an ethical secular humanist speaking about how their faith affects them and their workplace behaviors. In response, emerging adults in the class evidence learning more about their own moral values and about the values of other cultures. In-depth reading of essays and personal mission statements reveals that changes need to be understood in reference to different starting positions.I will be a more effective leader in a multi-faith workplace when I understand more of my coworkers’ culture: it shows that I care about them, and it keeps me from unintentionally offending someone. The speakers were not just supplemental to the reading; they were necessary to my understanding of the different wisdom traditions. The book gave me a good basis, but the speakers allowed me to understand the religion from a personal view and gave me a comfortable place to ask honest questions.

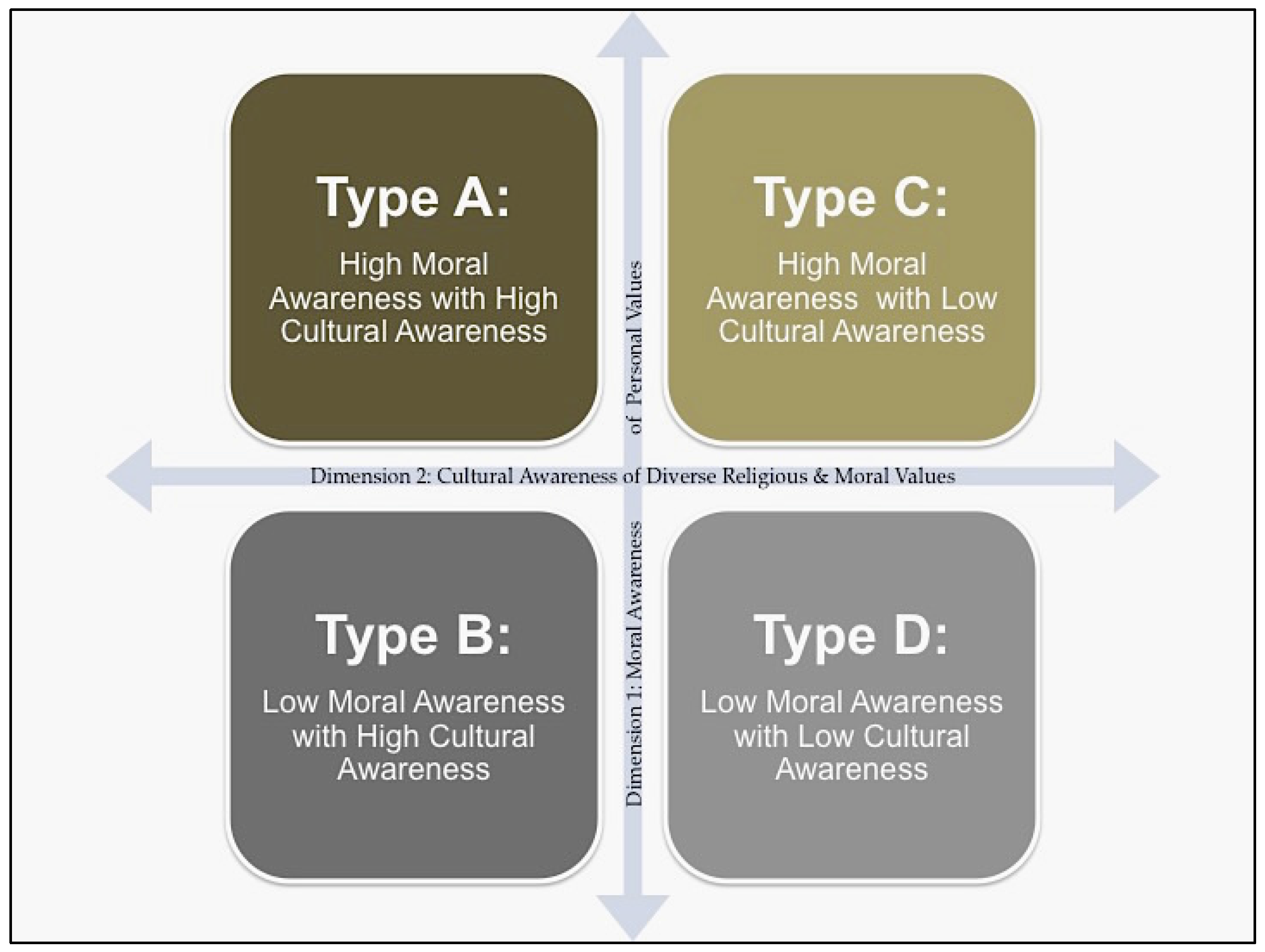

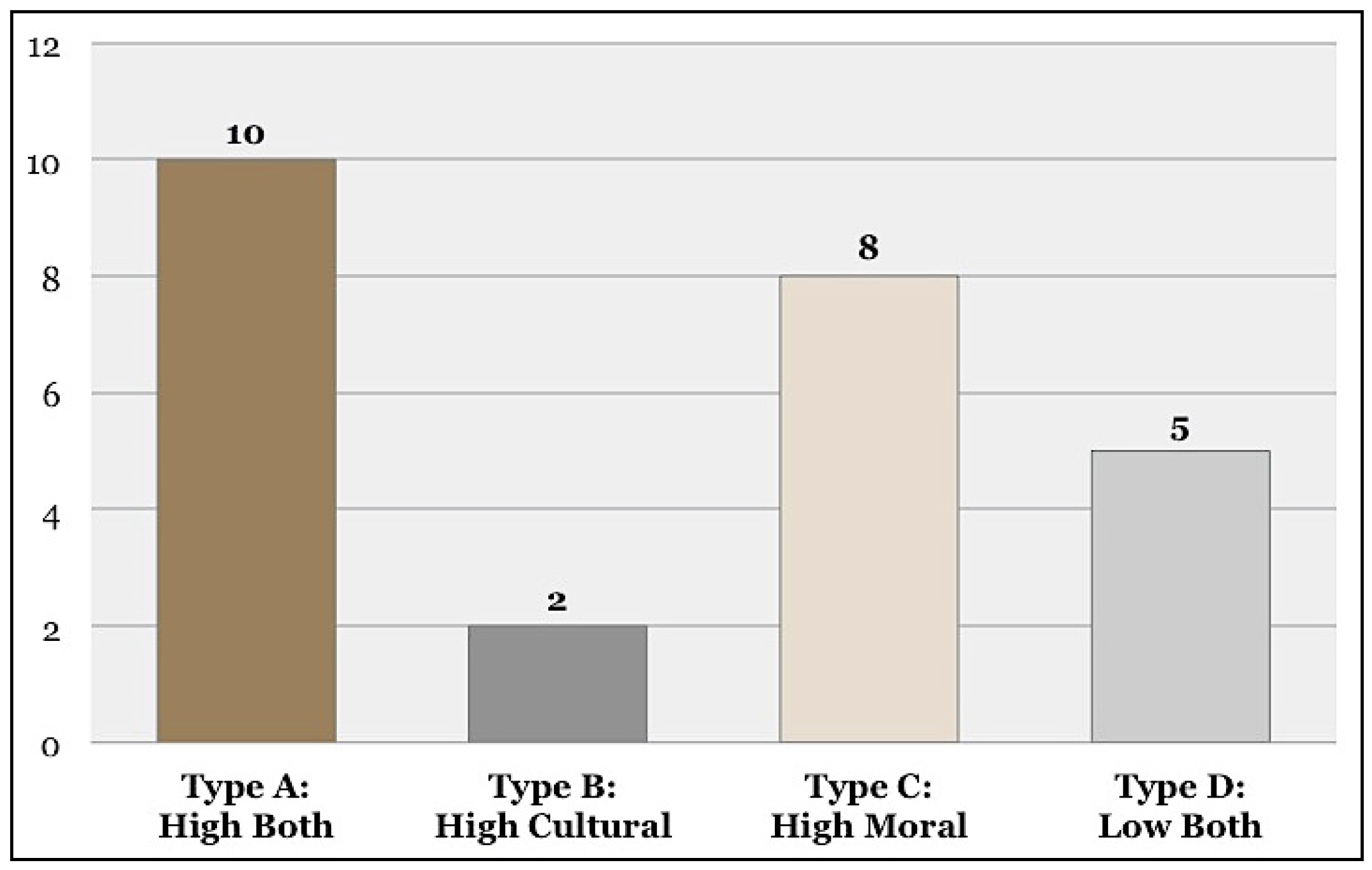

4.4. Understanding Changes Relative to Different Starting Points

In contrast, a student with a similar level of personal moral awareness but with a remaining low level of cultural awareness at the end of the semester—a Type C student—reported:I’ve been a Christian for many years, and hearing about other faiths brought me closer to God. I’ve known about other religions, but they were presented to me as “those people are wrong, but if we know what they believe then we can more easily convert them.” This instilled in me an unconscious prejudice towards anyone who follows a different wisdom tradition than I do, and in order to be truly genuine, I’ve had to overcome that.

While these students evidenced a quantitatively similar high level moral awareness, the differences in their cultural awareness made them interpret the meaning of their moral awareness in distinct ways: the Type A student toward respecting different moral values and the Type C toward better conversion to a homogenous set of moral values.As a Christian, a very big part of my life is sharing the truth of Jesus. With that being said, an understanding of what people of other religions believe is a necessary tool if I hope to ever lead anyone to Christ who practices another religion. Being familiar with other religions is a great tool to have.

Alternatively, a Type B student who reported increasing in cultural awareness but did not evidence increases in moral awareness described this somewhat confusing personal mission statement:I never really understood the true significance of writing down your values on paper. [Now I see that] it enables me to reflect on what is truly important to me and my life and concretize these values to make them meaningful and representative of who I am. I learned more about myself than I ever thought I could in such a short amount of time. It has been a satisfying and fulfilling experience that I will take with me through my journey in life.

This quote helps highlight the category of student who has high cultural awareness with low moral awareness, resulting in a desire to have a great deal of respect for different perspectives but seemingly lacking any sort of “moral yardstick” by which to evaluate conflicting views. The implication is that this sort of student would take the path of least resistance in a workplace setting, which is likely to be non-desirable for organizations seeking high levels of moral engagement. Nevertheless, the increase in cultural awareness evidences improvement relative to a student showing low levels of moral and cultural awareness, such as this example:Our set of core values are being respectful, being honestly, being open minded, and being motivated. Being respectful is going to be the main solution to the toxic environment that exist within the team. If each team member has a sense of respect for each other and is able to step back and put their emotions aside to possibly compromise with others then there will be a better atmosphere for everyone to work. Personally being respectful is one of the most important values to have when leading or working with a group because if you do not respect others, then others will not have respect for you.

This Type D student evidences a minor increase in moral and cultural awareness that may represent a greater level of cultural sensitivity and awareness of possible moral clarity to what existed prior, and which is what the student reported. However, the end result by the conclusion of the course shows a qualitatively distinct meaning that the moral and cultural awareness changes reported for the other types of students, and it remains unclear what if any impact will be had on the ethical decision-making of this student when in their future workplace.Since I came to the first class this semester I knew this class was different than the other ones I was attending, it was more about learning what you want out of life, ways to help you achieve it, and that we as humans all undergo this same process and we need to be respectful towards others and understanding that people have different ways of doing the same things.

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Future Studies

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations:

| NSYR | National Study of Youth and Religion |

References

- Jeffrey J. Arnett. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Arum, and Josipa Roksa. Aspiring Adults Adrift: Tentative Transitions of College Graduates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Smith, and Patricia Snell. Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Celia Moore. “Moral Disengagement in Processes of Organizational Corruption.” Journal of Business Ethics 80 (2008): 129–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan D. Duffy, Laura Reid, and Bryan J. Dik. “Spirituality, Religion, and Career Development: Implications for the Workplace.” Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion 7 (2010): 209–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles B. Schaeffer, and Jacqueline S. Mattis. “Diversity, Religiosity, and Spirituality in the Workplace.” Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 9 (2012): 317–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancy E. Day. “Religion in the Workplace: Correlates and Consequences of Individual Behavior.” Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 2 (2005): 104–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaret Benefiel, Louis W. Fry, and David Geigle. “Spirituality and Religion in the Workplace: History, Theory, and Research.” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6 (2014): 175–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengt B. Arnetz, Matthew Ventimiglia, Pamela Beech, Valerie DeMarinis, Johan Lökk, and Judith E. Arnetz. “Spiritual Values and Practices in the Workplace and Employee Stress and Mental Well-Being.” Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 10 (2013): 271–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André L. Delbecq. “The Impact of Meditation Practices in the Daily Life of Silicon Valley Leaders.” In Contemplative Practices in Action: Spirituality, Meditation, and Health. Goleta: ABC-CLIO, 2010, pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Vandenberghe. “Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Commitment: An Integrative Model.” Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 8 (2011): 211–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mario Fernando, and Brad Jackson. “The Influence of Religion-Based Workplace Spirituality on Business Leaders’ Decision-Making: An Inter-Faith Study.” 2006. Available online: http://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/165 (accessed on 10 October 2015).

- Scott J. Vitell. “The Role of Religiosity in Business and Consumer Ethics: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Business Ethics 90 (2009): 155–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward Soule. “Managerial Moral Strategies—In Search of a Few Good Principles.” Academy of Management Review 27 (2002): 114–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chase E. Thiel, Zhanna Bagdasarov, Lauren Harkrider, James F. Johnson, and Michael D. Mumford. “Leader Ethical Decision-Making in Organizations: Strategies for Sensemaking.” Journal of Business Ethics 107 (2012): 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig V. VanSandt, Jon M. Shepard, and Stephen M. Zappe. “An Examination of the Relationship between Ethical Work Climate and Moral Awareness.” Journal of Business Ethics 68 (2006): 409–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe Kum-Lung, and Lau Teck-Chai. “Attitude towards Business Ethics: Examining the Influence of Religiosity, Gender and Education Levels.” International Journal of Marketing Studies 2 (2010): 225–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William Phanuel Kofi Darbi. “Of Mission and Vision Statements and Their Potential Impact on Employee Behaviour and Attitudes: The Case of A Public But Profit-Oriented Tertiary Institution.” International Journal of Business and Social Science 3 (2012): 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Mark R. Bandsuch, and Gerald F. Cavanagh. “Integrating Spirituality into the Workplace: Theory & Practice.” Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion 2 (2005): 221–54. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy James Bowman. “An Ideal Type of Spiritually Informed Organizations: A Sociological Model.” Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion 5 (2008): 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céleste M. Brotheridge, and Raymond T. Lee. “Hands to Work, Heart to God: Religiosity and Organizational Behavior.” Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion 4 (2007): 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahira M. Probst, and Paul Strand. “Perceiving and Responding to Job Insecurity: A Workplace Spirituality Perspective.” Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion 7 (2010): 135–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan M. Saks. “Workplace Spirituality and Employee Engagement.” Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion 8 (2011): 317–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacqui Chaston, and Marjolein Lips-Wiersma. “When Spirituality Meets Hierarchy: Leader Spirituality as a Double-Edged Sword.” Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion 12 (2015): 111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janet Groen. “Spirituality within a Religious Workplace: Is it So Different? ” Journal of Management, Sprirituality, and Religion 4 (2007): 310–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland Robertson. “Individualism, Societalism, Worldliness Universalism: Thematizing Theoretical.” Sociology of Religion 38 (1977): 281–308. [Google Scholar]

- Steven Seidman. “Modernity and the Problem of Meaning: The Durkheimian Tradition.” Sociology of Religion 46 (1985): 109–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus H. Schafer. “Ambiguity, Religion, and Relational Context: Competing Influences on Moral Attitudes? ” Sociological Perspectives 54 (2011): 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan W. Husted, and David B. Allen. “Toward a Model of Cross-Cultural Business Ethics: The Impact of Individualism and Collectivism on the Ethical Decision-Making Process.” Journal of Business Ethics 82 (2008): 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Translated by Emile Durkheim, and Karen Fields. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. New York: Free Press, 1995.

- Lisa D. Pearce, and Melinda Lundquist Denton. A Faith of Their Own: Stability and Change in the Religiosity of America’s Adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Smith, Kari Christoffersen, Hilary Davidson, and Patricia Snell Herzog. Lost in Transition: The Dark Side of Emerging Adulthood. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kenda Creasy Dean. Almost Christian: What the Faith of Our Teenagers Is Telling the American Church. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Smith, and Melina Lundquist Denton. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tom Smith. “Generation Gaps in Attitudes and Values from the 1970s to the 1990s.” In On the Frontier of Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Public Policy. Edited by Richard A. Settersten Jr., Frank F. Furstenberg and Rubén G. Rumbaut. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005, pp. 177–224. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wuthnow. After the Baby Boomers: How Twenty- and Thirty-Somethings Are Shaping the Future of American Religion. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wuthnow. America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey J. Arnett. “Emerging Adulthood: What Is It, and What Is It Good For? ” Child Development Perspectives 1 (2007): 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary C. Waters, Patrick J. Carr, Maria J. Kefalas, and Jennifer Holdaway, eds. Coming of Age in America: The Transition to Adulthood in the Twenty-First Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- Douglas Hartmann, and Teresa Toguchi Swartz. “The New Adulthood? The Transition to Adulthood from the Perspective of Transitioning Young Adults.” Advances in Life Course Research, Constructing Adulthood Agency and Subjectivity in Adolescence and Adulthood 11 (2006): 253–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Bynner. “Rethinking the Youth Phase of the Life-Course: The Case for Emerging Adulthood? ” Journal of Youth Studies 8 (2005): 367–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James E. Cote. Arrested Adulthood: The Changing Nature of Maturity and Identity. New York: NYU Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne D. Osgood, Gretchen Ruth, Jacquelynne S. Eccles, Janis E. Jacobs, and Bonnie L. Barber. “Six Paths to Adulthood: Fast Starters, Parents without Careers, Educated Partners, Educated Singles, Working Singles, and Slow Starters.” In On the Frontier of Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Public Policy. Edited by Richard A. Settersten, Frank F. Furstenberg and Rubén G. Rumbaut. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005, pp. 320–55. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew J. Cherlin. “The Deinstitutionalization of American Marriage.” Journal of Marriage and Family 66 (2004): 848–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston Domina, and Josipa Roksa. “Should Mom Go Back to School? Post-Natal Educational Attainment and Parenting Practices.” Social Science Research 41 (2012): 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard Settersten, and Barbara E. Ray. Not Quite Adults: Why 20-Somethings Are Choosing a Slower Path to Adulthood, and Why It’s Good for Everyone. New York: Bantam, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seth J. Schwartz, Byron L. Zamboanga, Koen Luyckx, Alan Meca, and Rachel A. Ritchie. “Identity in Emerging Adulthood Reviewing the Field and Looking Forward.” Emerging Adulthood 1 (2013): 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich Beck. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- James W. Fowler. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. San Francisco: HarperOne, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen Parker. “Research in Fowler’s Faith Development Theory: A Review Article.” Review of Religious Research 51 (2010): 233–52. [Google Scholar]

- Carolyn McNamara Barry, and Mona M. Abo-Zena, eds. Emerging Adults’ Religiousness and Spirituality: Meaning-Making in an Age of Transition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Ofra Mayseless, and Einat Keren. “Finding a Meaningful Life as a Developmental Task in Emerging Adulthood the Domains of Love and Work across Cultures.” Emerging Adulthood 2 (2014): 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cynthia Kimball, Kaye Cook, Chris Boyatzis, and Kathleen Leonard. “Meaning Making in Emerging Adults’ Faith Narratives: Identity, Attachment, and Religious Orientation.” Journal of Psychology and Christianity 32 (2013): 221–33. [Google Scholar]

- Marie Good, and Teena Willoughby. “Adolescence as a Sensitive Period for Spiritual Development.” Child Development Perspectives 2 (2008): 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolyn McNamara Barry, and Larry J. Nelson. “The Role of Religion in the Transition to Adulthood for Young Emerging Adults.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 34 (2005): 245–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong Hyun Jung. “Sense of Divine Involvement and Sense of Meaning in Life: Religious Tradition as a Contingency.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54 (2015): 119–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel H. Barkin, Lisa Miller, and Suniya S. Luthar. “Filling the Void: Spiritual Development among Adolescents of the Affluent.” Journal of Religion and Health 54 (2015): 844–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicola Madge, Peter Hemming, and Kevin Stenson. Youth on Religion: The Development, Negotiation and Impact of Faith and Non-Faith Identity. New York: Routledge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Helen S. Astin, and Anthony Lising Antonio. “The Impact of College on Character Development.” New Directions for Institutional Research 122 (2004): 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James Weber, and David Wasieleski. “Investigating Influences on Managers’ Moral Reasoning the Impact of Context and Personal and Organizational Factors.” Business & Society 40 (2014): 79–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey N. Godwin. “Examining the Impact of Moral Imagination on Organizational Decision Making.” Business & Society 54 (2015): 254–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “National Study of Youth and Religion.” Available online: http://youthandreligion.nd.edu/ (accessed on 12 June 2015).

| Importance of Faith | Religion is Private |

|---|---|

| 75%—Primary (n = 26) | 21%—Primary (n = 26) |

| 58%—Controls (n = 83) | 47%—Controls (n = 83) |

| 56%—National (n = 315) | 52%—National (n = 315) |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herzog, P.S.; Beadle, D.A.T.; Harris, D.E.; Hood, T.E.; Venugopal, S. Moral and Cultural Awareness in Emerging Adulthood: Preparing for Multi-Faith Workplaces. Religions 2016, 7, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7040040

Herzog PS, Beadle DAT, Harris DE, Hood TE, Venugopal S. Moral and Cultural Awareness in Emerging Adulthood: Preparing for Multi-Faith Workplaces. Religions. 2016; 7(4):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7040040

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerzog, Patricia Snell, De Andre’ T. Beadle, Daniel E. Harris, Tiffany E. Hood, and Sanjana Venugopal. 2016. "Moral and Cultural Awareness in Emerging Adulthood: Preparing for Multi-Faith Workplaces" Religions 7, no. 4: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7040040

APA StyleHerzog, P. S., Beadle, D. A. T., Harris, D. E., Hood, T. E., & Venugopal, S. (2016). Moral and Cultural Awareness in Emerging Adulthood: Preparing for Multi-Faith Workplaces. Religions, 7(4), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7040040