Abstract

Acclaimed as one of the great filmmakers of the 20th century, Ingmar Bergman is for many an arch-modernist, whose work is characterized by a high degree of self-conscious artistry and by dark, even nihilistic themes. Film critics increasingly identify him as a kind of philosopher of the human condition, especially of the dislocations and misery of the modern human condition. However, Bergman’s films are not embodiments of philosophical theories, nor do they include explicit discussions of theory. Instead, he attends to the concrete lived experience of those who, on the one hand, suffer from doubt, dislocation, and self-hatred and, on the other, long for confession and communion. In the middle of his career, especially in his famous faith trilogy of the early 1960s, Bergman investigated the lived experience of the absence of God. It is commonly thought that after this period, the question of God disappeared. However, in his last two films, Faithless and Saraband, Bergman explores the lived experience of the absence of God. Indeed, he moves beyond a simple negation to explore the complex interplay of absence. He even illustrates the possibility of a kind of communion for which so many of his characters—early, middle and late—long.

Of the mid-century work of the Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, Francois Truffaut stated in 1973, “there is no body of work of the caliber and integrity of Bergman’s since the war” ([1], p. 34). Acclaimed as one of the great filmmakers of the 20th century, Ingmar Bergman is for many an arch-modernist, whose work is characterized by a high degree of self-conscious artistry and by dark, even nihilistic themes. Bergman seems increasingly to be identified as a kind of philosopher of the human condition, especially of the dislocations and misery of the modern human condition [2,3,4,5].1 In this, his work reflects the philosophical dilemmas of nihilism. As with many European filmmakers of the last century, he is quite self-conscious about his own artistry; indeed, such self-consciousness seems obligatory in those who aspire to artistic greatness. However, Bergman’s films are not embodiments of philosophical theories, nor do they include explicit discussions of theory. Instead, he attends to the concrete lived experience of those who, on the one hand, suffer from doubt, dislocation, and self-hatred and, on the other, long for confession and communion. In the middle of his career, especially in his famous faith trilogy of the early 1960s, Bergman investigated the lived experience of the absence of God. It is commonly thought that after this period, the question of God disappeared. However, in his last two films, Faithless [6] and Saraband [7], Bergman explores the lived experience of the absence of God. Indeed, he moves beyond a simple negation to explore the complex interplay of absence. He even illustrates the possibility of a kind of communion for which so many of his characters—early, middle and late—long. After a brief examination of Bergman and nihilism, we will turn to these two, final films in Bergman’s corpus.

1. Bergman, Nietzsche and Nihilism

One of his most famous films, Persona (1966), whose working title was Kinematografi, includes shots of rolls of film, a projector, and even a scene in which the film itself unravels. Pasolini once remarked that the sign of the new cinema was the “felt presence of the camera”; Susan Sontag adds that Bergman’s films introduce the “felt presence of the film as object” [8,9]. However, his enduring impact goes well beyond matters of filmmaking technique. As Brian Baxter put it in an obituary for The Guardian, Bergman “astonished people with his willingness to recognize cruelty, death and above all the torment of doubt” [10]. Where film is self-reflective in Bergman, the intent is to do more than merely call attention to the medium. Unlike many modernists, who exhibit distaste for ordinary life, Bergman features characters who are often quite ordinary and invites us to find them endlessly fascinating. For all of the philosophical interest Bergman’s films have garnered, his characters are remarkably free of interest in, or capacity for, speculative reasoning. As he describes them, “The people in my films are exactly like myself—creatures of instinct, of rather poor intellectual capacity, who at best only think while they’re talking. Mostly their body, with a little hollow for the soul” ([11], p. 190). Bergman traces not the development or dialectic of argument, but lived realities. In Bergman’s case, the diagnosis of modern malaise remains open to a quest. As Paisley Livingston comments, the “desire for alternatives motivates even his darkest moments” ([5], p. 76). Bergman does not entirely abandon the quest for alternatives even as he recurs to the mysteries of mortality, sin, guilt, grief, and the longing for reconciliation and communion.

Like Nietzsche, Bergman takes the loss of God more seriously than most believers take God’s existence. In a famous passage from The Gay Science, Nietzsche writes a sort of parable of a man who enters the marketplace to announce the death of God:

The insane man jumped into their midst and transfixed them with his glances. “Where is God gone?” he called out. “I mean to tell you! We have killed him, you and I! We are all his murderers! But how have we done it? How were we able to drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the whole horizon? What did we do when we loosened this earth from its sun? Whither does it now move? Whither do we move? Away from all suns? Do we not dash on unceasingly? Backwards, sideways, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an above and below? Do we not stray, as through infinite nothingness? Does not empty space breathe upon us? Has it not become colder? Does not night come on continually, darker and darker? Shall we not have to light lanterns in the morning? Do we not hear the noise of the grave-diggers who are burying God? Do we not smell the divine putrefaction?—for even Gods putrefy! God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him!([12], section 125)

The madman proceeds to pose questions: “How shall we console ourselves, the most murderous of all murderers? The holiest and the mightiest that the world has hitherto possessed has bled to death under our knife; who will wipe the blood from us? With what water could we cleanse ourselves?...Is not the magnitude of this deed too great for us?” [12]. The assertion of the death of God meets with bemused silence. The audience is prepared neither for the proclamation nor for its consequences. The madman, we should note, does not present the death of God as a welcome relief or as requiring minor adjustments in human life. Instead, the impact of the death of God is a devastating and debilitating loss of all foundations, of any proper perspective. The result is psychic vertigo. This vision of the death of God as involving the erosion of human self-understanding, even the dissolution of self, fits quite well the universe of many of Bergman’s films. Bergman seems also to have sensed that dwelling on nihilism will not do and that overcoming nihilism would require something other than the assertion of artistic will. The philosopher Robert Pippin sums up the fundamental problem for Nietzsche’s project. The very notion of an overcoming of nihilism, once it has been invited to destroy all existing foundations, is unlikely. Pippin remarks, “It is as if he thinks by defeating this legacy, or hastening its internal collapse, a new one could be created. We are not part of anything that could be continued, that is worth continuing” [13].

Nietzsche was of course given to grand narratives or genealogies of nihilism. He was also fascinated with the prospect of Grand aristocratic characters who stand beyond good and evil and create values. By contrast, Bergman’s focus is anti-theoretic and on ordinary characters. Bergman is less interested in philosophical argument, the construction of genealogies, or even generalized psychological analyses than he is in the lived experience of this loss. The religious element in Bergman’s films is mostly depicted as a lack or an absence—a distinctively post-Enlightenment “void” that remains “after material welfare has been taken care of” and the big questions have apparently been resolved or reduced to meaninglessness [14]. In this too he follows Nietzsche who thought the death of God encapsulated the deflation of ultimate demise of all ideals including the secular ideals of progress, liberty, science, and reason.

Long after he purportedly gave up on the God-question, religious language and imagery figure prominently. This is true of his final two contributions to film: the script for Faithless (2000), a film directed by his long-time collaborator Liv Ullmann, and Saraband (2007). Such themes are present in Bergman’s work from start to finish, as is clear from a newly released retrospective interview, Bergman’s Island, conducted by Marie Nyerod not long before his death. The interview is included in a new Criterion Collection edition of Bergman’s most famous movie, The Seventh Seal (1957), the film for which he earned his reputation as a philosophical filmmaker. Bergman’s interest in the big questions began with Seal [15], in which a medieval knight (Max von Sydow), returning from the Crusades, questions his faith and, in a scene as often mocked as imitated, plays chess with death. It peaks with his famous faith trilogy in the early 1960s, after which he claimed to have lost interest in such questions. Bergman remains preoccupied with questions of guilt, particularly guilt over marital infidelity, with the obstacles to self-knowledge and truthful speech, and with the human yearning for reconciliation through confession.

In his films, he portrays an absence in the very bodies of his characters, in the ways they struggle to perceive and communicate the dislocation and suffering, the inexplicable longings and seemingly imminent madness that is characteristic of life in advanced modern civilization. Of course, the ability to mark or name the absence means that one is still haunted by a presence. Here Bergman may have anticipated in art some of the insights of contemporary philosophers who have wrestled with Nietzschean nihilism and discovered not darkness but light. As the philosopher William Desmond observes, thorough-going nihilism is never possible, even if a variety of trends in modern philosophy, politics, and culture seem inevitably to “return to zero, coming to nothing” ([16], p. 28). However, Desmond speculates: “Can our return to zero enliven again out taste for the ethos of being and its signs of transcendence?” ([16], p. 31). Even after we are driven to one sense or another of nothingness, we must acknowledge that something still is. God and the religious categories of traditional belief endure after God’s alleged demise in Bergman’s films, perhaps especially in Faithless. The enduring presence of absence also leaves open the possibility of a richer experience of the presence of God, a possibility Bergman explores quite subtly, if concisely, in Saraband.

2. Faithless

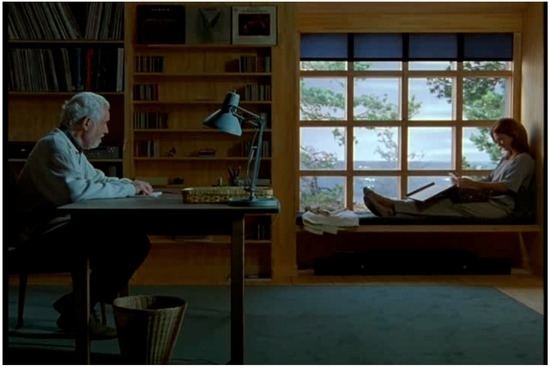

In the opening of Faithless, a character named Bergman (Erland Josephson) sits in the study of his home on the coast of Faro (where Bergman lived for many years and where the footage for Bergman’s Island was shot). As he sits at his desk he conjures up an actress, who takes the name Marianne (Lena Endre), to help him work through his latest script (Figure 1). Prompted by Bergman, Marianne relates the story of her affair with David (Krister Henriksson), a divorced director and close friend of her husband, Markus (Thomas Hanzon), an internationally renowned orchestra conductor and father their nine-year-old daughter, Isabelle (Michelle Gylemo). In various ways and at various points in the film, it is made clear that the actress, Marianne, is identical to the Marianne of the script and that Bergman himself is an older version of David.

Figure 1.

Bergman and Marianne write her story.

Bergman here deploys his craft to explore the connection between art and life, to excavate the past in search of self-knowledge. The desire, as much a perverse form of self-laceration as a hope for justice, involves seeing one’s life more truthfully and facing more directly those whom one has harmed. The very shape of the film raises questions about the possibility and purpose of confession.

While Markus is away, David makes one of his regular visits with Marianne and Isabelle. When late in the evening he proposes sex to Marianne, she laughs and dismisses the idea as folly. However, the suggestion takes root and Marianne begins to plan an adulterous liaison in Paris. When David hesitates, Marianne shrugs him off, saying the affair could be “simple and fun...Life need not be a series of disasters”. She could not be more wrong. David is self-absorbed, self-pitying and, even when he is playful or charming, he is inevitably self-serving. Eventually his violent jealousy, predictably followed by bouts of remorse, comes to dominate the relationship. As they “sink deeper” into the abyss, Marianne likens her life to a “dream where what we fear most happens over and over again”. Void of affection and pleasure, she and David share a “friendship in damnation.” The low point for her occurs when, in the midst of a bitter custody battle, Markus calls to suggest they work things out more amicably. When they meet, he is blunt: “If you fuck me, I’ll give you custody.” He then subjects her to a series of humiliating sexual acts. Shaken, she returns to David, reluctant to tell him what has occurred. His jealousy piqued, David becomes enraged and spends the entire night interrogating Marianne, forcing her to confess every excruciating detail. Here confession is forced, unwelcome, and at the service of the prurient and cruel desires of David. Revelation involves humiliation and the subjection of the confessor to the vampiric desire of another, a former lover who sucks the life out of her [5,8,17].2

Pregnant with David’s child, she opts for an abortion. The physical and verbal abuse of Marianne is not, however, the most heart-wrenching sequence in the film. The film pivots on the scene where Markus confronts David and Marianne, a scene Marianne retrospectively describes as the beginning of the “tragedy“. However, the tragedy actually begins in the very next scene, when Marianne tells Isabelle that she’s leaving her and her father to live with David. Informed that she will have to stay with her grandmother, Isabelle plaintively asks why she can’t come live with David. Marianne sobs convulsively as she recalls the conflict within her, wishing to embrace and assure her daughter they’ll “always be together.” What she actually says is, “there’s no room.” Marianne’s internal sundering over the harm she knows she’s doing to her daughter is subtly intimated in the movie’s most exquisitely filmed scene. The audience sees Marianne doubled, both Marianne and her reflection in a mirror; then Isabelle appears, reflected in the mirror and seen from the audience’s perspective between the two images of Marianne (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). As is true of this scene, so too throughout the film, the daughter appears in the film mostly in the background, typically alone in her bedroom where she overhears the virulent arguments of the adults. Her role is scripted perfectly to reinforce her status as an innocent victim of adultery and divorce. Bergman’s portrayal of the impact of adult vice on children has never been more dramatically expressed than in the script for Faithless. Music from a child’s music box, now in Bergman’s possession, begins and ends the film and accentuates the sense of innocence irrevocably lost.

Figure 2.

Marianne battles with herself, Isabelle in the midst.

Figure 3.

Marianne battles with herself, Isabelle in the midst.

Figure 4.

Marianne battles with herself, Isabelle in the midst.

Figure 5.

Marianne battles with herself, Isabelle in the midst.

At the outset, Bergman/David evokes Marianne’s character and she appears. On the basis of various promptings from him, she retells the story of her affair. One of the peculiar features of this film is that the female character initiates the infidelity that propels the action of the plot, even if it becomes clear that the men are even more self-absorbed than she. Most of the film is her own narrative, her confession. She certainly feels guilt but, as time passes, the more prominent experience is that of helpless grief: the aching sense that “every day is wrong” and that she has “lost the ability to make rational decisions.” The film is a compelling portrait of the way sin is its own punishment. It is also brutally honest about the nature of jealousy, about envy as a middle term between lust and rage. Under the sway of vice, freedom becomes an illusion, and pleasure vanishes.

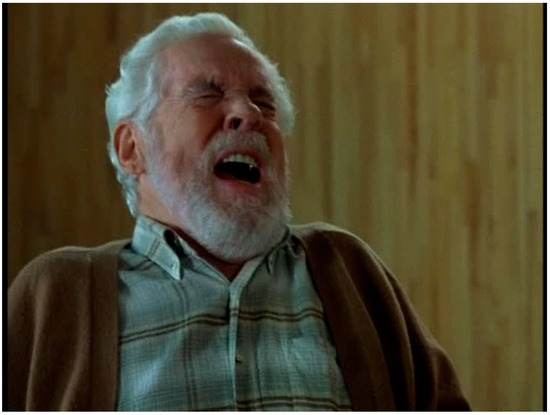

Consumed with their lusts and rivalries, the adults are but dimly and fleetingly aware of their impact on Isabelle. There is a terrifying scene in which Isabelle alone in her room relates to one of her dolls the following nightmare. Although the season is summer, it is cold and snowing. She encounters a lady who wears her mother’s fur coat and who, she soon discovers, is eating children. “There is no way out”, she says, and she is “very scared”. Images of the violation of the natural order run through the dream, which Isabelle narrates with chilling dispassion. Even more chilling is the way in which the scene emerges from a scene of David, in one of his moments of wrathful envy. The two scenes are cut in such a way that David nearly merges with Isabelle or rather Isabelle’s nightmare emerges from David (Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 6.

David retreats...

Figure 7.

…to sleep.

Figure 8.

Isabelle emerges…

Figure 9.

…telling of a nightmare.

Bergman’s attention to children has little in common with the modern, romantic celebration of childhood. Indeed, Hollywood films increasingly present divorce as a norm and suggest that overcoming its effects is simply a matter of liberating the creative and sensitive impulses of children. Bergman’s insistence on multi-generational conflict and on the way the sins of the parents are visited upon the next generation is more akin to the Old Testament and the novels of Dostoevsky. If there is a weakness to Bergman’s portrayal of family dissolution, it has to do with his reversal of Tolstoy’s dictum in the opening of Anna Karenina: all happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. For Bergman, unlike Tolstoy, all unhappy families are unhappy in the same way: through infidelity, jealousy, and vengeful rage. If this renders Bergman’s treatment of the family rather repetitive, it also allows him to offer a diagnosis of the peculiar afflictions and fears of the modern psyche. A theme prominent in Bergman and again reminiscent of Dostoevsky is that of laceration, the irrational habit of self-imposed suffering. A perverse form of asceticism, laceration mimics self-sacrifice and repentance, even as it turns violence inward. Instead of freeing one for others, laceration keeps one trapped in oneself.

This is the self-destructive grief in which Marianne finds herself ensnared. In Bergman’s films, adult characters, who often describe themselves as undergoing a kind of damnation, vacillate between the active pursuit of selfish pleasure and the retreat to paralyzing regret. This is but one of many illustrations in Bergman’s films of his belief in the existence of a “virulent evil,” caused not by the “environment or heredity.” He comments, “Call it original sin or whatever you want, anyway, it is an active evil, present only in human beings” ([11], p. 40).

At various points in Faithless Marianne weeps, as does Bergman/David, alone with his remorse, near the end of the film. The best art can do is to attempt to give shape to the chaos, to articulate the quest for meaning and, since redemption is not at hand, to gain some consolation from the activity of articulating pain, loss, and regret. In Faithless and many other Bergman films, there is a sense of foreboding and a pervasive fear. The issue of God and his absence is not approached through theoretical argument or even direct discussion, but rather though the lived, felt experience of guilt and condemnation, however inexplicable. Irving Singer astutely places this film in the mythic tradition of romantic love, exemplified in the medieval and modern versions of the myth of Tristan and Isolde, in which romantic love inevitably leads to death. Of course, in the typical telling of that myth, romantic love is an ideal that mixes passion and danger, transformation and destruction, elevation and debasement. Faithless leaves out the first and positive element in each pair; it is a devastating anti-romantic myth ([4], p. 99). It is also anti-romantic in its refusal to allow art to replace religion. There is no transformation of love through memory or art in Faithless, despite the efforts of its conjuring protagonist (Bergman).

Because Faithless is quite consciously a film about an artist calling to life characters who in turn narrate and question one another about events, there is a greater emphasis on speech than is typically true of Bergman’s films. However, what is shown is often more powerful than what is said. Indeed, the film begins and ends with the director, Bergman, alone, with images of him in an empty house or on a barren coastline, framed by the seemingly endless sea (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Solitary beginning.

Figure 11.

Solitary ending.

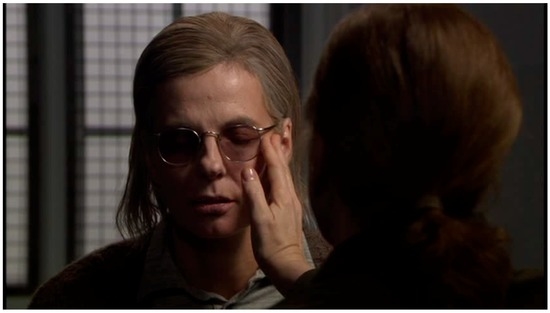

The only exception to the film’s introductory and valedictory silence is not the spoken word, but the sound of the child’s music box that plays in Bergman’s office near the conclusion of the film. The closest the film comes to some sort of reconciliation or expression of communion is in a powerful scene in which Bergman the director conjures the presence of David, his younger self. In every other scene in which David appears, he appears as part of Marianne’s narration. In this one instance, David is conjured by Bergman and appears as a persona existing temporally between the time of the action Marianne narrates and Bergman’s present. He confesses that he wishes he “could be sent to punishment”; instead, he has a strange “life sentence” from which he can “never escape”. At this moment, Bergman reaches out in a gesture of affection and gently touches David’s face. David then disappears and Bergman, in isolation, weeps (Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14). Here physical touch, shown rather than verbally described, embodies the longing of the characters for compassion and re-union.

Figure 12.

Reflexive Touch: Bergman/David.

Figure 13.

Reflexive Touch: Bergman/David.

Figure 14.

Reflexive Touch: Bergman/David.

Even if the balance of saying to showing tilts a bit more to the former than the latter in Faithless, this film, perhaps most dramatically in this scene between Bergman and David, supports Truffaut’s claim about Bergman, namely, that “no one draws so close to the human face.” Truffaut adds that, in many of Bergman’s films, “there is nothing more than mouths talking, ears listening, eyes expressing curiosity, hunger, panic” (qtd. in Koskinen [14], p. 36). This is certainly true of the most wrenching images in Faithless.

In his interpretation of the film, Singer thinks that in other films, but not in Faithless, Bergman embraces an alternate myth, in which active love transforms, and notes that this alternative form is “inherently religious” ([4], p. 99). What Singer does not see or at least does not note, is that the anti-romanticism of Faithless is equally religious. The questions raised in the film are not as explicitly religious as in some of Bergman’s earlier films, perhaps most notably in The Seventh Seal; nor is God put to the test. Instead, there is the burden of sin and judgment in the absence of God. The title itself (Faithless) is striking. Bergman’s script begins with a blunt stipulation: “Divorce is no common failure…with one cut it slices more deeply than life itself”. The film, an extended confession of an affair that leads to divorce, is a devastating presentation of the human cost of infidelity. The vices of lust and pride initiate a descent, almost by a kind of mechanical necessity, into a world of misery and violence against others and oneself. Why does infidelity matter? Why should we, who have thrown off religious belief and practice, be plagued with guilt over one’s past misdeeds, over the harms inflicted on others? Why be burdened with a need to confess? Why the insatiable desire for forgiveness? Why should fidelity, a decidedly theological notion, remain normative for us? And what are we to make of the ambiguous status of art, its ability to help us face the past and its inability to effect reconciliation or salutary repentance? Despite his claim that, after the faith trilogy, he simply dropped the religious issue, religious questions endure into Bergman’s final period. This is a strange world indeed, one in which God is nowhere present but in which the religious language of divine judgment haunts the characters no matter where they turn.

3. Saraband

Although not a comic or happy film, the film following Faithless and Bergman’s last film, Saraband presents the question of God and human love more richly, marked by a suggestive interplay of presence and absence. The film is at once a sort of nostalgia piece and a retrospective of the kind of story Bergman most liked to tell. It stars two of Bergman’s favorite actors, Ullmann and Erland Josephson, who reprise their roles from one of Bergman’s most accessible productions, Scenes from a Marriage (1973). However, as the title indicates, it is an ambitious statement about art, suggestive of the notion that film is the great integrative art form of the modern world, the artistic medium in which music and theater find their completion. A Saraband is a musical piece for dance; the film features musicians; and its structure, in ten acts with a prologue and an epilogue, mirrors the theater. Moreover, at least one significant scene suggests a deep connection between religion and art.

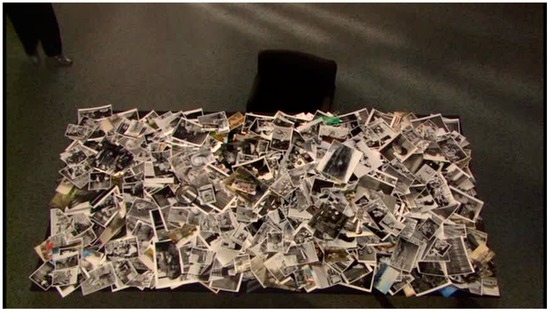

The film begins and ends with Marianne (Ullman) holding family photographs and directly addressing the camera (Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17). At the outset, pictures of her life with her former husband Johan (Josephson) prompt her to plan a visit to see him, after years of estrangement. We learn early on that they had two daughters together, one of whom Martha, has drifted into a catatonic state and lives in an institution. Marianne’s direct address to the camera constitutes a kind of private, intimate confession. The telling of the story is prompted by reflection on images, which make the absent present or at least recall them to memory. These are typical mechanisms and motifs in Bergman. The opening of Scenes from a Marriage, which Saraband recalls directly and indirectly, features an apparently happily married couple being interviewed about their marriage for local TV and is instructive. The couple responds jovially to the superficial questions of the popular media, but Bergman’s film will take us beneath the surface to reveal tortured souls.

Figure 15.

Marianne, her photos, and us.

Figure 16.

Marianne, her photos, and us.

Figure 17.

Marianne, her photos, and us.

Johan now lives near his son, Henrik, from another marriage and Henrik’s daughter Karin, both of whom are gifted musicians. Henrik, Karin, and even Johan remain in mourning over the death of Henrik’s wife (and Karin’s mother) Anna, who is described as a pure and loving person and whose photograph is treated with reverence by everyone who knew her. Johan and Henrik despise one another and exhibit the cold, remote and manipulative traits typical of Bergman’s male characters. After her arrival, Marianne finds herself in the middle of the tensions, not just between Johan and Henrik, but also between Henrik and his daughter, Karin. At one point, Marianne enters a small chapel where Henrik is playing Bach’s St. John’s Passion on the organ; the music, we should note, is being played in the setting for which it was intended.

The allusion here, concerning the connection between art and religion, is gentle but it calls to mind one of Bergman’s most revealing statements: “Art lost its basic creative drive the moment it was separated from worship” [18]. He also associated his art with the anonymous craftsmen of the great medieval cathedrals. Moreover, the description of the source of late twentieth-century alienation given in Persona remains a viable interpretation of the world depicted in Bergman’s entire corpus: our anxious terror, the evidence of our forlornness and our terrified unexpressed silence is rooted in our loss of faith. Excruciating, alienating silence is the lived experience of the absence of God and of the failure of modernity’s surrogates for God. A not unreasonable interpretation of certain types of silence in Bergman’s films is as an illustration of Nietzsche’s pithy claim that we haven’t rid ourselves of God because we have been unable to rid ourselves of grammar [19].3 In so far as language still provides a means of communication between individuals about a common world, we quite naturally assume a transcendent basis for such intelligibility. Bergman has described his desire to make films as arising from a need for human contact, of mutual recognition that, despite the confusion and angst of the human condition, we still hold in common the most important matters of the human soul. In these films, as Jerry Gill has argued in his Ingmar Bergman and the Search for Meaning, “the quest”, however unfulfilled, is for a certain type of communal existence [20]. This is precisely the quest of Marianne throughout and of other characters at least intermittently.

Henrik soon ceases playing and joins Marianne for a conversation that starts out in a friendly enough fashion but soon turns hostile. Henrik vilifies Johan, going so far as to say that he would like to watch him die a slow, torturous death. Marianne offers some defense of Johan and, after Henrik departs, finds herself alone in the church. What follows is one of the most remarkable scenes in Bergman’s entire corpus.

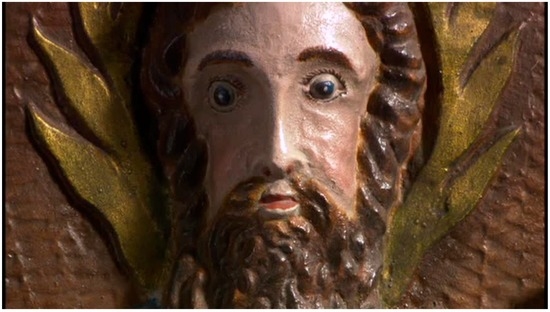

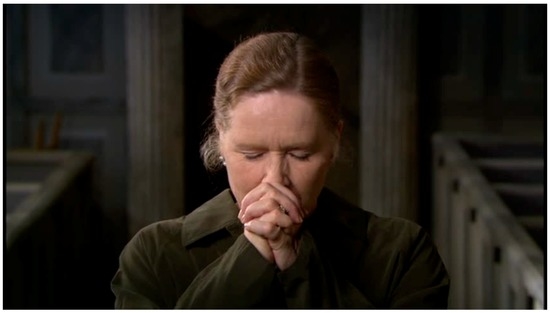

Heading down the aisle toward the exit, she stops, turns back around and faces the altar. As she does so, light floods in through a window in a descending diagonal and bathes her in light. Marianne concentrates her attention on a porcelain tableau of the Last Supper at the center of which is the beloved disciple John reclining upon Jesus. Eyes still focused on the Last Supper, she makes a gesture of prayer (Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22). Here is precisely the note of divine love and communion that is so often absent in Bergman’s films.4 It also seems to move beyond what Bergman described as the conflict between his childhood piety and the harsh rationalism of adult life. The appearance of an encompassing light is significant. As William Desmond observes, nihilism makes the light itself strange. Were nihilism the ultimate truth, we would expect no light, and yet there is light. We see the “truth” of nihilism in a light that nihilism, were it true, would render impossible? What is that light? Is it something in which we are, in the more primal ethos of being, which we do not bring to be, but rather we are simply what we are as participants in it ([16], p. 33)?

Figure 18.

Light, Art, Prayer.

Figure 19.

Light, Art, Prayer.

Figure 20.

Light, Art, Prayer.

Figure 21.

Light, Art, Prayer.

Figure 22.

Light, Art, Prayer.

One way to formulate the theological problem in Bergman is this. It is a common opinion among critics that, by focusing on the absence of God, Bergman’s early films exemplify the crisis of religious belief in the modern world. However, that is not quite accurate. Bergman’s films often illustrate the presence of a certain sort of God, an intimidating, scolding, authoritarian God, who manifests himself not in wisdom and beauty but in arbitrary acts of will. Recall the violent spider God from Through a Glass Darkly. Bergman describes “God as something destructive and fantastically dangerous, something filled with risk for the human being and bringing out in him dark destructive forces” ([11], p. 164). Bergman seems to have been trapped in a partial and distorted truth about God [21].5 This is a strange God but perhaps not strange enough. For, it is an all too familiar conception of paternal authority, a God made in the image and likeness of the distant, insecure, power-hungry father figures that populate so many of Bergman’s films. This is a God with whom love and communion is neither possible nor desirable, even if those under the sway of such cruel paternalism seem doomed to try to fulfill such a futile quest.

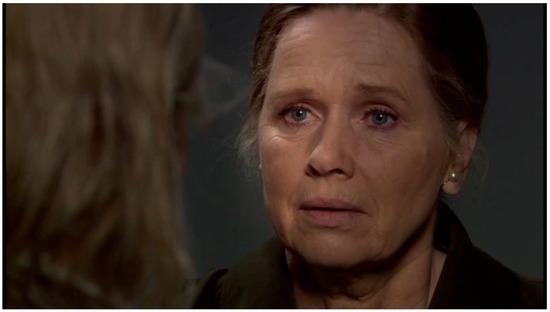

Marianne’s prayers, or at least her intentions to bring reconciliation between family members, are not answered, at least not the way in which she intends when she stands in reverence in the chapel. In the epilogue, as she again peruses photographs, she says she tried to stay in contact with Johan but that he gradually quit responding. We might say that he slipped away just as Martha is described as doing. However, his slipping away is volitional, a species of conscious avoidance. The themes of isolation and absence are prominent in nearly all Bergman’s films. The retreat to the margins of the human community has complex sources. In this film, it is clear that the catatonic daughter Martha suffers an extreme form of what all human beings suffer to varying degrees and what we all potentially suffer at any moment. However, she does not represent simple absence. Indeed, in this film, the two most influential characters are never present in the ordinary sense in which we use the term: the first is Martha, while the second is Anna, the beloved and deceased mother and wife, who exercises an influence over all the other characters. Reflecting on Anna’s love, Marianne is prompted to visit the other absent character, her daughter Martha, whose face she touches for the first time. In their wordless silence, there is an intimation of love and communion (Figure 23, Figure 24 and Figure 25). There is rich material here, I think, for rethinking the notion of disability in a theological light. Communion here is not an abstract idea or an object of discussion; it is not so much said as it is shown in the ritual practice of human touch, a gesture of affection.

Figure 23.

Silence, Touch, Communion.

Figure 24.

Silence, Touch, Communion.

Figure 25.

Silence, Touch, Communion.

Saraband is a late example of what are known as Bergman’s chamber plays, in which scenes of two characters in dialogue dominate. In such a context, silence is as important as speech and the face itself becomes a vehicle of expression. Bergman has identified close-ups of human faces as the “highest point” of the art of film ([5], p. 148). Paisley Livingston rightly underscores the importance of a passage from a Bergman essay in 1959, “Each Film is My Last”:

There are many filmmakers who forget that the human face is the point of departure for our work…Proximity to the human face is without a doubt the cinema’s most special feature and mark of distinction. We should draw the conclusion from this that the actor is our most precious instrument and that the camera is only a means of registering that instrument’s reactions…We should realize that the best means of expression the actor has at his or her command is the gaze…The objectively composed, perfectly directed and played close-up is the director’s most powerful means of influencing the audience. It is also the most flagrant proof of his competence or incompetence. The lack or wealth of close-ups shows in an uncompromising way the temperament of the film director and the extent of his interest in people.([5], p. 148)

The passage, which fits well Bergman’s own practice as a filmmaker, reinforces the claim made above about Bergman’s interest in ordinary humanity, in capturing the wordless communication of the human face in its inscrutable materiality.

The attention to faces, to their images and their realities, might be said to be a kind of vocation of Marianne in Saraband. Such attention opens for her a new path of active love. Her new opportunity provides an occasion for viewers to rethink God in Bergman. At one point, Johan reads Kierkegaard’s Either/Or. Kierkegaard’s tripartite division of ways of life (aesthetic, ethical, and religious) here reduces to two: the aesthetic and the religious, even if that is not as well defined here as in Kierkegaard. Johan, it seems, has opted to remain a jaded isolated aesthete, one who avoids commitment and the hard work of active love. Marianne herself pursues that very path, the practice of active love of another. Of course, this path is one that very few Bergman characters ever follow. Instead, for most characters, union with another evokes guilt, anxiety, and fear of self-dissolution.

That is what makes Marianne’s epiphany in the church exceptional. Here communion is certainly desirable: Marianne’s posture of peaceful, receptive, contemplation; the flood of warm light; and the nourishing, sacramental image of the Last Supper—all of these are positive notes. However, she has not been actively seeking or troubled by doubts and questions. Somehow she is receptive, open to the gift of peace and grace being offered in this moment in this church. The scene and Marianne’s subsequent physical gesture of affection toward her comatose daughter suggest a way of overcoming the dialectic between absence and presence, or at least a way of holding the paradox together. It underscores the different ways of being absent: one can die, fall into a coma, or willingly depart. It also suggests that those who are absent can continue to exercise an influence on those they have left behind; the absent can even be an occasion for grace and communion. Such possibilities have theological implications that render the topic of divine absence more nuanced and fertile than has typically been acknowledged.

In Marianne’s visit to her daughter, we find further confirmation of Truffaut’s observation about Bergman’s art and its attentiveness to the human face. We have already noted Truffaut’s claim that Bergman’s films are often “nothing more than mouths talking, ears listening, eyes expressing curiosity, hunger, panic” (qtd. in Koskinen [14], p. 36). This much is true of Faithless. However, there is something different in Saraband, an almost sacramental presentation of the human face, evident in the maternal gesture of love toward her daughter’s face. This is the answer to what Irving Singer identifies as the “problem of getting in touch, being in touch, with another person, whose presence manifests itself in her face and through her face’s accessibility to the tactile capacity of someone’s hand”. Bergman attends to what Singer calls the human face as an “icon of personhood” ([4], p. 176). Marianne thus moves from an icon of the Last Supper to the icon of personhood in her daughter’s face.

The reference to the icon is instructive and suggests a way to reconceive presence and absence and to envision communion. Instead of a cold, detached, and idolatrous distancing of the observer from the comprehended object of the gaze, the encounter with an icon involves a subversive process whereby the one seeking and looking is discovered and beheld. The face as icon is not an idolatrous object to be manipulated to satisfy our wishes—the very trap into which so many of Bergman’s characters fall. Instead, the face looks back. In Bergman, the looking back often occasions a vampiric battle of wills between the two gazes. By contrast, in the experience of the icon, one touches and is touched; one is receptive, as Marianne is both in the church and with her daughter, to being affected by another [22,23].6 The prospect of union is no longer a paralyzing peril or an anxiety-producing hazard but a welcome vulnerability to another.

Bergman may go one better than the theorists of the icon by focusing on touch rather than sight. Sight is the least embodied of the senses, which is why from Plato on it has provided the chief sensible analogy to philosophical contemplation. By contrast, touch is the most embodied. While sight enables us, if we so choose, to keep our distance, in touch we cannot not be affected by that which we encounter. Instructively this is also true in the icon of the Last Supper that occasions Marianne’s moment of grace. In that icon, the beloved disciple is not satisfied to hear the words and watch the gestures of Jesus; he leans in to make physical contact with Jesus, to touch his very body. Of course, in the Eucharistic feast, what is presented is not just touched and tasted but physically devoured. In the course of his two final cinematic creations, Bergman moves from a depiction of the damnation of infidelity to the quiet communion of fidelity toward those entrusted to one’s care.

4. Conclusions

We have moved well beyond Bergman’s depiction of the lived experience of communion to a quasi-theoretical account of the function of the icon. If it is even partially true that, as is increasingly the consensus among scholars, Bergman’s films reflect philosophical debates at the level of drama and appropriately prompt philosophical questioning in viewers, then it is also true that Bergman’s films should make us acutely aware of risks of such theorizing. What is significant in the encounter of an icon, as with the meeting of human persons, is not what we say about it, much less the coherence of our theories. The significance rather is embedded and embodied in the concrete, lived reality of the encounter. This is better shown or exhibited than said or talked about [24,25].7 This is Bergman’s craft, to display the “wordless secrets that only cinema can discover” [26].

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Francois Truffaut. “On Ingmar Bergman.” In Ingmar Bergman: An Artist’s Journey. Edited by Robin G. Oliver. New York: Little, Brown and Co., 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Geoffrey Macnab. Ingmar Bergman: The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director. London: IB Tauris, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- John Orr. The Demons of Modernity: Ingmar Bergman and European Cinema. Oxford: Berghahn, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Irving Singer. Ingmar Bergman, Cinematic Philosopher. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Paisley Livingston. Cinema, Philosophy, Bergman: On Film as Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Faithless, Directed by Liv Ullmann. Stockholm: AB Svensk Filmindustri, 2000.

- Saraband, Directed by Ingmar Bergman. Stockholm: Sveriges Television, 2003.

- Susan Sontag. “Bergman’s Persona.” In Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, Cambridge Film Handbooks. Edited by Lloyd Michaels. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 62–85. [Google Scholar]

- Susan Sontag. “Bergman’s Persona.” In Styles of Radical Will. New York: Picador, 2002, pp. 123–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brian Baxter. “Ingmar Bergman.” The Guardian, 30 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stig Bjorkman, Torsten Manns, and Jonas Simma. Bergman on Bergman: Interviews with Ingmar Bergman. Translated by Paul Austin. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich Nietzsche. The Gay Science. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Pippin. Modernism as a Philosophical Problem: On the Dissatisfactions of European High Culture. Malden: Blackwell, 1991, p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Maaret Koskinen. “The Typically Swedish in Ingmar Bergman.” In Ingmar Bergman: An Artist’s Journey. Edited by Robin G. Oliver. New York: Little, Brown and Co., 1995, p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- The Seventh Seal, Directed by Ingmar Bergman. Stockholm: AB Svensk Filmindustri, 1957.

- William Desmond. God and the Between. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Frank Gado. The Passion of lngmar Bergman. Durham: Duke University Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ingmar Bergman. Four Screenplays of Ingmar Bergman. Translated by Lars Malmström, and David Kushner. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1960, p. xxii. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich Nietzsche. “The Twlight of the Idols.” In The Portable Nietzsche. Edited by Walter Kaufmann. London: Penguin, 1982, p. 483. [Google Scholar]

- Jerry Gill. Ingmar Bergman and the Search for Meaning. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1969, p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Terry Eagleton. Reason, Faith, and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009, p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Luc Marion. God without Being. Translated by Thomas A. Carlson. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991, p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Hibbs. Aquinas and Philosophy of Religion. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Peter T. Geach. “Saying and Showing in Frege and Wittgenstein.” In The Philosophy of Wittgenstein. Edited by John V. Canfield. New York: Garland Publishing, 1986, vol. 3, pp. 54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jerry Gill. “Saying and Showing: Radical Themes in Wittgenstein’s ‘On Certainty’.” Religious Studies 10 (1974): 279–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingmar Bergman. Images: My Life in Film. Translated by Marianne Ruuth. New York: Arcade, 1994, pp. 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- 1Recent books that locate Bergman at the center and summit of 20th century filmmaking include those by Geoffrey Macnab [2] and John Orr [3]. Two recent books argue for and probe the philosophical import of his films: Irving Singer [4] and Paisley Livingston [5].

- 2Bergman is acutely aware of the link between eros and thanatos, between sex and violence, but he mixes Freudian themes with theological language of damnation and the longing for confession and forgiveness. There are numerous psychoanalytic elements in Bergman’s films; yet, Susan Sontag’s statement, in her famous piece on Persona, that Bergman’s art is “beyond psychology” just as it is “beyond eroticism,” is apt. See Sontag, ([8], p. 69). For a psychoanalytic reading of Bergman’s films, see Frank Gado [17]. For a critique of that position, see Livingston [5]. Arguing that Bergman’s philosophical vision of the world is informed by the philosophical psychology of Eino Kaila, Livingston shows that Bergman resisted the mechanistic and reductionistic elements in psychoanalysis.

- 3“I am afraid that we are not rid of God because we still have faith in grammar.” [19].

- 4Not entirely absent of course; there is communion meal of the knight in The Seventh Seal with Jon and Marie and the opening and closing communion ceremonies in Winter Light, a film whose initial working title was “The Communicants”.

- 5As Terry Eagleton observes in his book on the new atheists, the conception of God whose existence is purportedly disproven in their writings, is, according to traditional Christian theology, not God at all, but rather a first cause in a series or the highest member of a set. These beings would not meet the criteria of divine transcendence articulated in the writings of Thomas Aquinas or one of his astute contemporary interpreters, Herbert McCabe. Appealing to Thomas and McCabe, Eagleton shows that God is not the big, bad daddy in the sky, “the largest and most powerful creature”. Neither is theology intended to explain the operations of nature. But it does respond to questions concerning “why there is anything in the first place, or why what we do have is actually intelligible to us”. Surveying the scene of popular religion in the West, in which the Gospel of Success is prominent, Terry Eagleton wonders what place there is for the teaching of the Gospels that the “truth of history” is a “mutilated body” of a “tortured innocent”. Although Bergman was not a believer, his depiction of the human condition focuses on the themes of psychic “mutilation” and “torture” inflicted by others or by the self on itself. However deficient his most common conceptions of God may be, Bergman is a counter both to the happy-go-lucky consumerist nihilism increasingly on the rise in the West and to the self-congratulatory rhetoric of the Gospel of success. See Eagleton ([21], p. 27).

- 6In explicitly theological language, Jean-Luc Marion describes the icon thus: “Here our gaze becomes the optical mirror of that at which it looks, only finding itself more radically looked at; we become a visible mirror of an invisible gaze that subverts us in the measure of its glory…Thus in contrast to the idol, …the icon displaces the limits of our visibility to the measure of its own—its glory. It transforms us in its glory by allowing this glory to shine on our face as its mirror,” ([22], p. 22). Marion’s thought is complex and mobile. For a discussion of the development of his writing about God and an assessment of its strengths and weakness, see Aquinas and Philosophy of Religion [23].

- 7I use the distinction between saying and showing as it occurs in ordinary language but of course the contrast calls to mind Wittgenstein. See Peter T. Geach [24] and Jerry Gill [25].

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).