The history of the kingdom of Khotan in the western part of the Tarim Basin (modern Xinjiang Uighurs’ Autonomous Region, China) is only partially known (

Figure 1). Ancient historical phases of Khotan are still too unclear, while Chinese chronicles and Tibetan Annals allowed a reconstruction of events after the conversion to Buddhism around the third century CE. Despite some early contacts with Buddhism having possibly already happened as early as the first century BCE (

De La Vaissière 2010, p. 86), Khotanese rulers adopted Buddhism some time later—as mentioned above, around the third century CE—and this remained the main religion of the entire kingdom until the Karakhanid conquest in the early eleventh century CE (

Kumamoto 2009).

Before the conversion to Buddhism, only archaeological material (especially coins) and some information kept in Chinese written sources could help not only in reconstructing the ancient history of Khotan but also its ancestral religion as well. There is some interesting information in the Hou Hanshu or the “Book of the Later [Eastern] Han” (presented to the court in 445 CE), specifically in the part concerning the biography of Ban Chao (班超).

This Chinese general, active in the second half of the first century CE, conquered the Tarim Basin, expelling the powerful Xiongnu, defeated the Kushans, and even sent envoys to the Parthians with the hope of reaching Da Qin, that is, the Roman Empire. In 73 CE, Ban Chao arrived in Khotan (Yutian 于田 in the text), whose king Guangde (廣德) did not treat the Chinese general according to his rank. Some “sorcerers” at his service suggested that Guangde keep good relations with the Xiongnu envoys, but not with the Han, and requested Ban Chao’s horse in order to sacrifice that animal to a non-specified Khotanese “irritated god”. Ban Chao pretended to agree and asked the leader of the sorcerers to come to him and personally obtain the horse of the Chinese general. However, Ban Chao beheaded the sorcerer and sent his head to Guangde along with his complaints about the bad treatment that he had suffered in Khotan. At that point, Guangde had all the Xiongnu envoys killed and performed an act of submission to Ban Chao, who then brought wonderful gifts to the king of Khotan and his subordinates (

Chavannes 1906, p. 221).

This episode of the biography of Ban Chao does not openly reveal the pre-Buddhist religion of Khotan. It is not completely clear if the sacrifice of the horse to a mysterious god, apparently irritated with the behaviour of Guangde, who was considered too benevolent towards the Chinese, could be just a further disrespectful act or even a literary invention. However, we should not dismiss the possibility that the information is somehow correct. In this latter instance, the horse sacrifice could point to some kind of Iranian-connected ritual also attested to among the Persians and other Central Asian peoples. Archaeological excavations at the Khotanese cemetery of Shanpula revealed at least two graves for horses that are possibly dated to the period between the second century BCE and the fourth CE. It is not clear if those horses were sacrificial animals, although they were accurately buried with several decorations (

Bunker 2001, pp. 36–38). In the Avesta, the holy book of Zoroastrianism, horse sacrifices performed for some deities appear often, such as in the Aban Yasht [5.108], where they were dedicated to the fertility goddess Anahita.

Reports about horse sacrifices among Iranian peoples, such as the Massagetes, Scythians, and Persians, have been appearing in Greek sources since ancient times. According to Herodotus, the magi (Zoroastrian priests), following the army of Xerxes, sacrificed a horse on the bank of a river that demarked the border between Europe and Asia in those days [Histories VII. 113]. The sacrifice by the river points to probable connections between this animal and water or the passage into the underworld. In fact, several tombs excavated in a wide area from Eastern Europe to Southern Siberia, associated with the highly mobile Scythians, revealed a great number of sacrificial horses (

Schiltz 1994, pp. 417–34). Another Greek author, Xenophon, mentioned generic horse and bull sacrifices in honour of Persian deities [Cyropedia VIII. 24], while, some time later, Arrian wrote that one horse was sacrificed during the funeral of the great Persian king Cyrus [Anabasis VI. 29]. At least one scholar argued that the horse sacrifice was not common among ancient Iranians, especially the Persian Achaemenids (ca. 550–330 BCE) (

Allen 2005, p. 194). However, one funerary monument of a Persian officer found in Egypt deserves special attention because of the decorative motifs carved in low relief on its surface. The dead appears lying on a bed wearing non-Egyptian garments and accessories (

Figure 2). Moreover, he has a long beard and hair. In the upper-left corner of this funerary scene, there is one desperate person who is conducting a riderless horse, possibly destined to some kind of sacrifice (

Boardman 2000, Figure 5.57).

Some other Greek written sources mentioned horse sacrifices among the Persians in less-ancient periods, such as during the Sasanian Dynasty (224–651). According to George of Pisidia (seventh century CE), Zoroastrian priests requested Persian Christian nobles to abjure and re-convert to their original creed by performing some rituals, including the worship of an enigmatic “harnessed horse” (

‘ένοπλος ‘ίππος) (

Pertusi 1971, pp. 616, 625–26). Even though it does not seem that such horses referred to the sacrifice of the animal, it is noteworthy that from the Achaemenid to the late Sasanian period, Persians paid special attention to sacred horses, as witnessed by Greek authors.

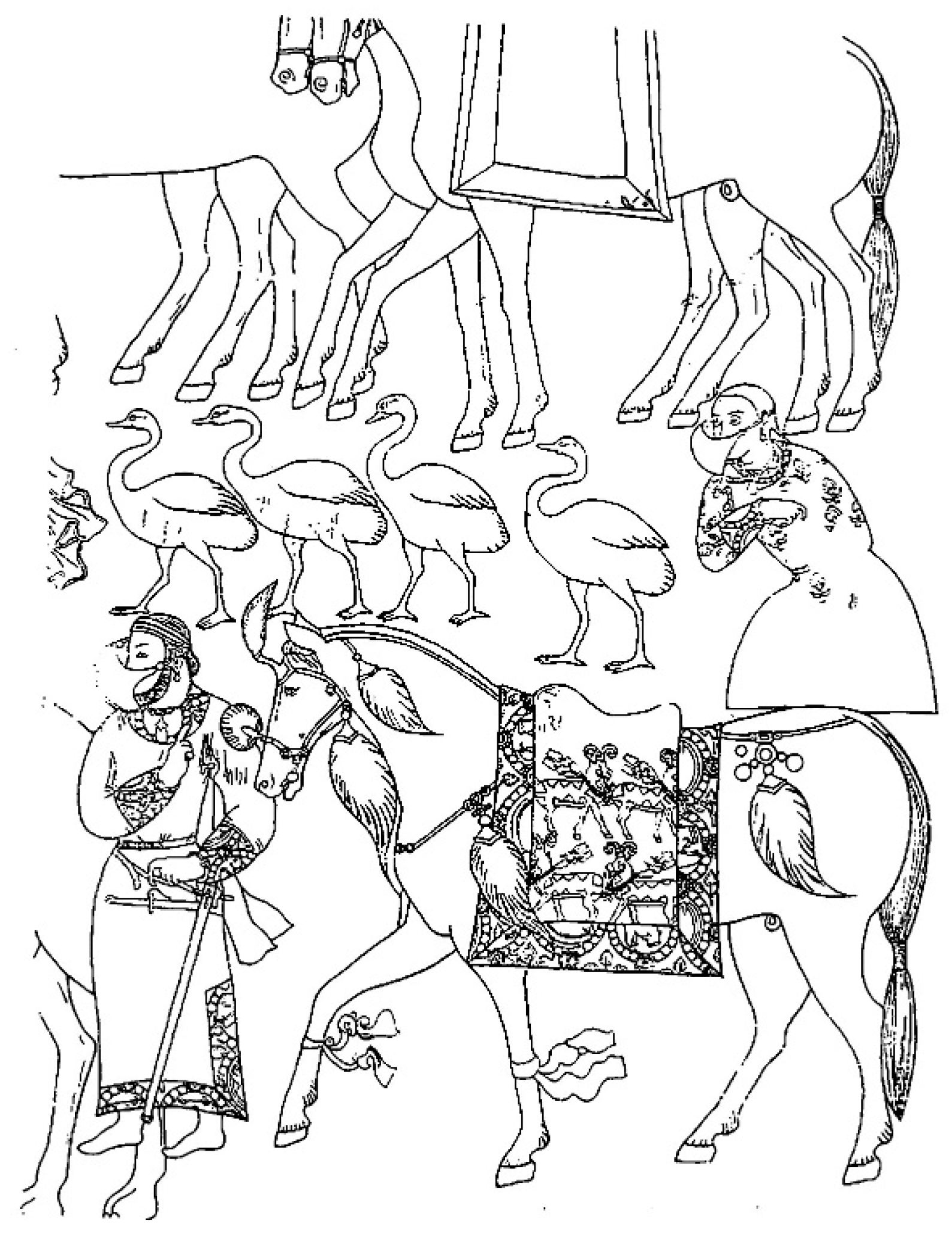

Eastern Iranians, such as the Sogdians, probably used to sacrifice horses to their deities, which referred to the local version of Zoroastrianism followed in pre-Islamic Central Asia that was quite different from the other forms of this religion observed in Persia or the Caucasus. One sacrificial harnessed and riderless horse appears among the animals depicted on the southern wall of the seventh century Afrasyab (Samarkand) paintings (

Figure 3) (

Compareti 2016, pp. 132–39). According to Frantz Grenet (

Grenet 1993, p. 61), another similar sacrificial horse can be observed in the lower part of an unexcavated ossuary from Sivas (Uzbekistan), which, at present, is kept in the History Museum in Tashkent and possibly dated to the seventh century (

Figure 4), as are some excavated fragmentary ones from Yumalaktepa (

Figure 5) (

Berdimuradov et al. 2008).

Important deities of the so-called “Zoroastrian” religion, followed by ancient Iranian peoples in Persia and Central Asia, could appear in visual arts as riding a horse or sitting on a throne shaped with horse protomes. A good example of the first case is the early Sasanian rock relief at Naqsh-i Rustam, where a trilingual inscription (Parthian, Middle Persian, and Greek) on the chest of the horse reveals the name of the deity mounted on it as Ahura Mazda, the supreme god of Persian Zoroastrianism (

Figure 6) (

Overlaet 2013;

Shenkar 2014, p. 52).

The situation was different among the Sogdians, since the main deity of their polytheistic pantheon was the Mesopotamian goddess Nanaya/Nana. One should not rule out the possibility that, in a funerary context, the fully harnessed and riderless horse could be interpreted as a symbol of the absence of the deceased. According to one polemic Manichaean fragmentary text in Sogdian found in Turfan (Xinjiang), usually referred to as M 549, there is mention of a funerary lamentation performed by mortals and deities, among whom Nana occurs too. In addition, a horse appears in the text as clearly destined to be sacrificed as part of the enigmatic funerary ritual (

Grenet and Marshak 1998, p. 7). Despite its fragmentary state, the Manichaen Sogdian text clearly mentions the role of the horse, and it should then be considered most likely a sacrificial animal connected to Nana and not a symbol of the absence of the dead. However, some eighth–ninth century Sogdian mural paintings present at least four deities associated with horses. In a seventh–eighth century burnt wooden frieze from the Sogdian site of Penjikent (Tajikistan), room 11/sector VII, the deity is sitting on a chariot in the typical position of Greco-Roman solar gods (

Figure 7). In fact, he is most likely Mithra or the Sogdian solar god Khwer (

Lurje 2023, p. 450). In at least one other case, in an early ninth-century Sogdian mural painting from Bunjikat (Tajikistan), an unidentified bearded deity possibly connected with Central Asian fluvial cults is sitting on a throne with legs that take the shape of a horse’s (

Figure 8) (

Shenkar 2014, pp. 111, 130). In addition, goddesses could present the horse as their symbolic animal. In one eighth-century Sogdian painting from the so-called Temple I at Penjikent, there is an image of a goddess holding a small horse under her arm who, according to experts on pre-Islamic Central Asian arts, could be the Avestan patroness of cattle Druvaspa (

Figure 9) (

Shenkar 2014, p. 97). Horses probably played an important role in Temple I, since another mural painting from that religious building presents another unidentified god standing in front of a fully harnessed horse (

Figure 10) (

Shkoda 2009, Figure 118). The funerary role of this animal should not be underestimated, since riderless horses appear often in funerary monuments that belonged to powerful Sogdians who emigrated to Northern China in the sixth century, which were recently excavated mainly around Xi’an and Taiyuan (

Lerner 2005, pp. 17–18).

The brief list presented above seems to point to the horse as an important animal that could be the victim of sacrifices, an animal to be worshipped, and the symbol of several deities of the Persians and Central Asian peoples during the pre-Islamic period. Horses among ancient Iranian peoples had connections with the sun and water, exactly like in Classical art and culture, where, as it is well known, Helios, Apollo, and Poseidon could appear on a chariot drawn by horses. In India, too, the horse could be the

vahana (vehicle or symbol) of Vedic deities such as the solar god Surya (

Frenger 2020). As it is well known, all the peoples just mentioned had ancient common linguistic and cultural roots that, in some instances, specialists of religious and mythological studies (such as Jaan Puhvel) (

Puhvel 1987) have cautiously compared and examined.

Khotan belonged linguistically to the group of eastern Middle Iranian languages that also included Sogdian, Bactrian, and Chorasmian. It would then be worth searching for local deities who had the horse as their symbolic animal or any connection with it in Khotanese art and religion.

However, it is worth observing that even in the case of a deity who could have the horse as a sacrificial animal, they should not be considered almost automatically associated with equines. In fact, any generic deity of a polytheistic religious system could have a horse (or another animal) sacrificed without any specific connection with it. Big animals such as horses, sheep, or, in Central Asia, camels seemed to be sacrificial victims of relevant deities such as—at least in the case of the Sogdian religion—the enigmatic deity reported in Chinese written sources of the Sui period (589–618) with the name Dexi (得悉), which is probably an epithet reconstructed as Takhsich (“the revenant”) (

Compareti 2016, pp. 254, 281). According to F. Grenet, Takhsich was a goddess who presented associations with the Mesopotamian Geshtinanna (

Grenet 2020, p. 30). However, in this writer’s opinion, that epithet does not present any gender connotation and could then refer to the god married to the great goddess of Sogdiana Nana, who had Mesopotamian origins too. Sogdians knew him as

tyδr, which is pronounced Tish (

Compareti 2024, pp. 55–56, 82).

Parades of haloed deities riding a spotted or reddish horse appear quite often in Khotanese Buddhist paintings. Stein took a photo of a mural painting from a small temple at Dandan Oilik, now irremediably lost, that depicted some horse riders close to a naked lady, bathing together with a child in a pond (

Figure 11) (

Rowland 1974, p. 127;

Compareti 2020, pp. 103–4). More recently, Chinese archaeologists have excavated haloed deities similar to the ones that embellish the wooden tablets found by Stein, and now kept in the British Museum (

Figure 12), at Dandan Oilik Temple CD4 (

Figure 13) and Domoko Temple 2 (

Figure 14) (

Xinjiang Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, China and The Academic Research Organisation for the Niya Ruins of Buk-kyo University, Japan, 2009, pl. 37.2, 77.2;

Compareti 2020, p. 104). Each riding deity does not present just a halo behind the head, floating ribbons, and a moustache, but also a black bird that seems to fly into the cup that is held in one hand by those deities. Unfortunately, it is not possible to identify them, nor is it possible to propose any clear meaning for such attributes, although one could assume that they point to the superhuman nature of those horse riders. Even the Khotanese inscription appearing in the painting on the northern wall of Temple CD4 does not help to shed light on the identity of any local god appearing in a Buddhist frame. That inscription mentioned enigmatic “eight spirits” who could be the protectors of Khotan, as reported in some written sources (

Rong and Zhu 2019).

Another Khotanese deity associated with horses embellishes a non-excavated wooden tablet from the Dandan Oilik Buddhist site that is, at present, kept in the Overseas Museum in Bremen (Germany). On that tablet, an almost completely faded haloed deity is standing between two antithetic horses, although details are unclear because of the poor state of preservation of the object (

Figure 15) (

Mode 1991–1992, Figure 18.h). More recently, Chinese archaeologists found a very similar image among the paintings of Temple CD4 at Dandan Oilik (

Figure 16) (

Compareti 2020, pp. 108–10). However, the mural painting could only reveal that the deity had a beard. There is, unfortunately, no inscription nor other hints to propose any identification for this deity that does not seem to belong to the Indian milieu, as is obvious to expect in Buddhist art. This god is not multi-armed either, such as in the case of the so-called “god of sericulture” that embellishes at least six other wooden tablets from Dandan Oilik (

Figure 17) (

He 2024).

As this writer has already proposed that, in another study dedicated to non-Indian Khotanese deities, the god standing between antithetic horses presents interesting parallels with an unusual representation of the sun depicted in one Persian astrological manuscript dated to the Islamic period and at present kept in Paris (Paris Bibliothèque National de France, Supplément Persan 332, folio 21v) (

Compareti 2020, pp. 110–11). In that book illustration, each planet is accompanied by a text that helps to identify it. A crowned angel holding a large disc in front of him appears between two confronting horses as a personification of the sun (

Figure 18). The French expert on astrological iconographies, Anna Caiozzo, dedicated an important paper to this astrological manuscript and could not find any clear parallel in Persian art. For this reason, she argued that there could be Central Asian elements that, however, she did not investigate (

Caiozzo 2003). If the sun appeared in a human shape between confronted horses in at least one Persian manuscript with a strong Central Asian background, it could then be obvious to imagine that such Iranian traditions could have reached Khotan as well.

It is noteworthy that, in Khotanese, the sun was called

urmaysde (

Bailey 1982, p. 29), a term clearly connected with the Avestan god Ahura Mazda, who is considered by the Persians to be the main deity at the head of their pantheon, or a “king of gods”. In the Sasanian rock relief from Naqsh-i Rustam mentioned above, the god riding a horse is called Ahura Mazda in the Parthian and Middle Persian versions of the inscription, while, in Greek, he is referred to as Zeus (in genitive case ΔIOC ΘEOΥ), who is another well-known “king of gods” (

Back 1978, p. 282). Therefore, there could be some indirect evidence to argue that the deity between the two confronted horses could be a local version of a (solar?) god accepted into the Buddhist pantheon of Khotan. He could be an important pre-Buddhist deity of the ancestral Khotanese religion who continued to appear along with other local gods in the act of worshipping Buddha, as has already happened to Vedic deities in the art of Mathura, or in Gandhara since the very early representations of the Enlightened One in India.

There is no definitive evidence that could allow us to propose any precise identification between the irritated deity who requested that the horse of Ban Chao be sacrificed to him and the (solar?) god between antithetic horses observed in Khotanese paintings. In fact, they could be two separate divine entities. One could merely speculate that the Khotanese god with horses had some astrological connotations. Other enigmatic deities appearing in Khotanese paintings, such as the gods riding a horse with a cup in hand where a black bird seems to be directed, the so-called “sericulture god”, and the god(s) riding a camel, could find possible identifications in the astrological sphere as well.

More archaeological excavations and dedicated research would be necessary in the fascinating field of pre-Buddhist Khotanese studies in order to obtain conclusive identifications.