On Intermediality of the Medicine Sutras and Their Imagery During the Sui Dynasty at Dunhuang

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The Sutra on the Initiation to Remove Unwholesome Deeds and Attain Salvation from Birth and Death Taught by the Buddha (Foshuo guanding bachu guozui shengsi dedujing 佛說灌頂拔除過罪生死得度經) by Śrīmitra 帛尸梨密多 in Eastern Jin Dynasty (東晉 317–420);

- The Medicine Buddha Lapis Lazuli Light Sutra (Yaoshi liuliguang jing 藥師琉璃光經) translated by Huijian 慧簡 in the Liu Song Dynasty (劉宋 420–479) (now lost);

- The Medicine Buddha Tathagata Original Vow Sutra (Foshuo yaoshi rulai benyuan jing 藥師如來本願經) by Dharmagupta (達摩笈多) in the Sui Dynasty (581–619);

- Medicine Buddha Lapis Lazuli Light Tathagata Original Vow Merit Sutra (Bhaiṣajyaguru-vaiḍūryaprabha-rāja-sūtra 藥師琉璃光如來本願功德經) by Xuanzang (玄奘 602–664) in the Tang Dynasty (618–907); and

- The Medicine Buddha Lapis Lazuli Light Seven Buddhas Original Vow Merit Sutra (Saptatathāgatapūrvapraṇidhānaviśeṣ 藥師琉璃光七佛本願功德經) by Yijing (義淨 632–713) of the Tang Dynasty.

2. Textual Analysis

2.1. Time, Locations, and Other Major Information of When the Sutra Was Been Orated

2.2. The Twelve Great Vows

- 1.

- All the nice physical attributes of a Buddha, mahā-puruṣa lakṣaṇa (32 marks of greatness), will be manifested to emit boundless, bright light to countless realms.

- 2.

- The body will radiate light of clear and pure lapis lazuli, and dwell in the web of light that is brighter than the sun and the moon. The beings in the dark will be awakened and be capable of engaging in matters according to their wishes.

- 3.

- With a Buddha’s wisdom and skillful means, all sentient beings will be granted abundant properties.

- 4.

- All sentient beings walk on the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path.

- 5.

- All sentient beings will be able to observe precepts, cultivate wholesome deeds, and avoid falling into the woeful paths.

- 6.

- Those with less than perfect physical faculties will become healthy again and be free from suffering.

- 7.

- When the less privileged and marginalized people hear my name, their illnesses and afflictions will be alleviated.

- 8.

- With peaceful and joyful minds, they will achieve the Supreme Bodhi eventually.

- 9.

- All who were caught by the dark force will be able to acquire the right views and walk the right path, cultivate the Bodhisattva practice, and realize the Ultimate Bodhi.

- 10.

- By the Buddha’s virtues and power, those who were subject to injustice and oppression will be free from mental and physical sufferings.

- 11.

- Ample of delicious food and drinks will be available to those who committed unwholesome deeds due to deprivation of food and water in previous lives. Then they will dwell in ultimate peace and joy with the “food of Dharma.”

- 12.

- Fine clothing will be available to those who do not have cloth to cover themselves so they can protect themselves from severe bad weather.

2.3. The Bodhisattva Sun, and the Bodhisattva Moon

2.4. Eight Bodhisattvas

2.5. The Four Heavenly Kings

2.6. Lamps and the Long Flags That Prolong People’s Lives

2.7. Twelve Demigods

3. On the Imagery of the Medicine Buddha Sutra in Dunhuang During the Sui Dynasty

3.1. General Description of the Caves

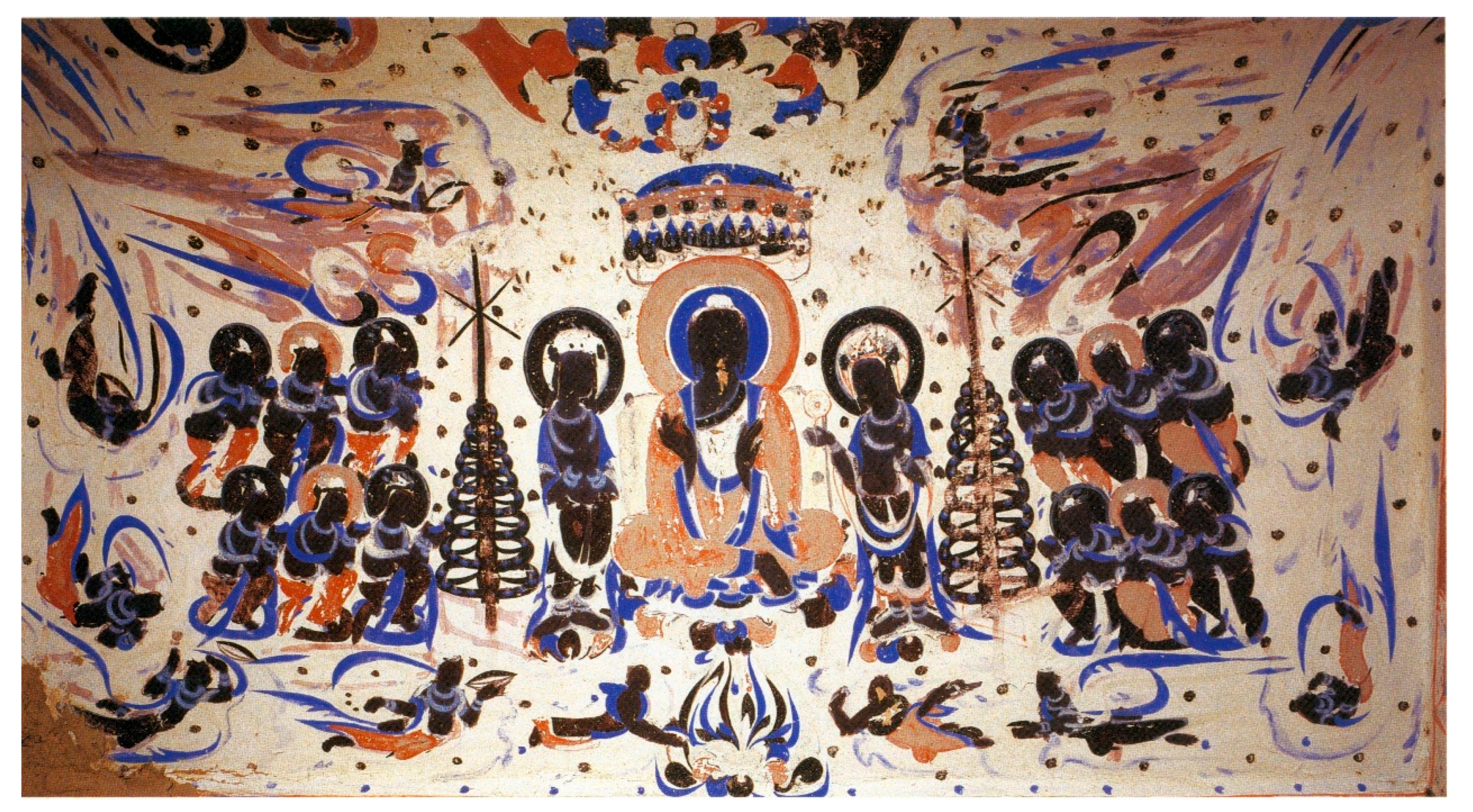

3.1.1. On the Ceiling Behind the Niche in the West Wall in Cave 417

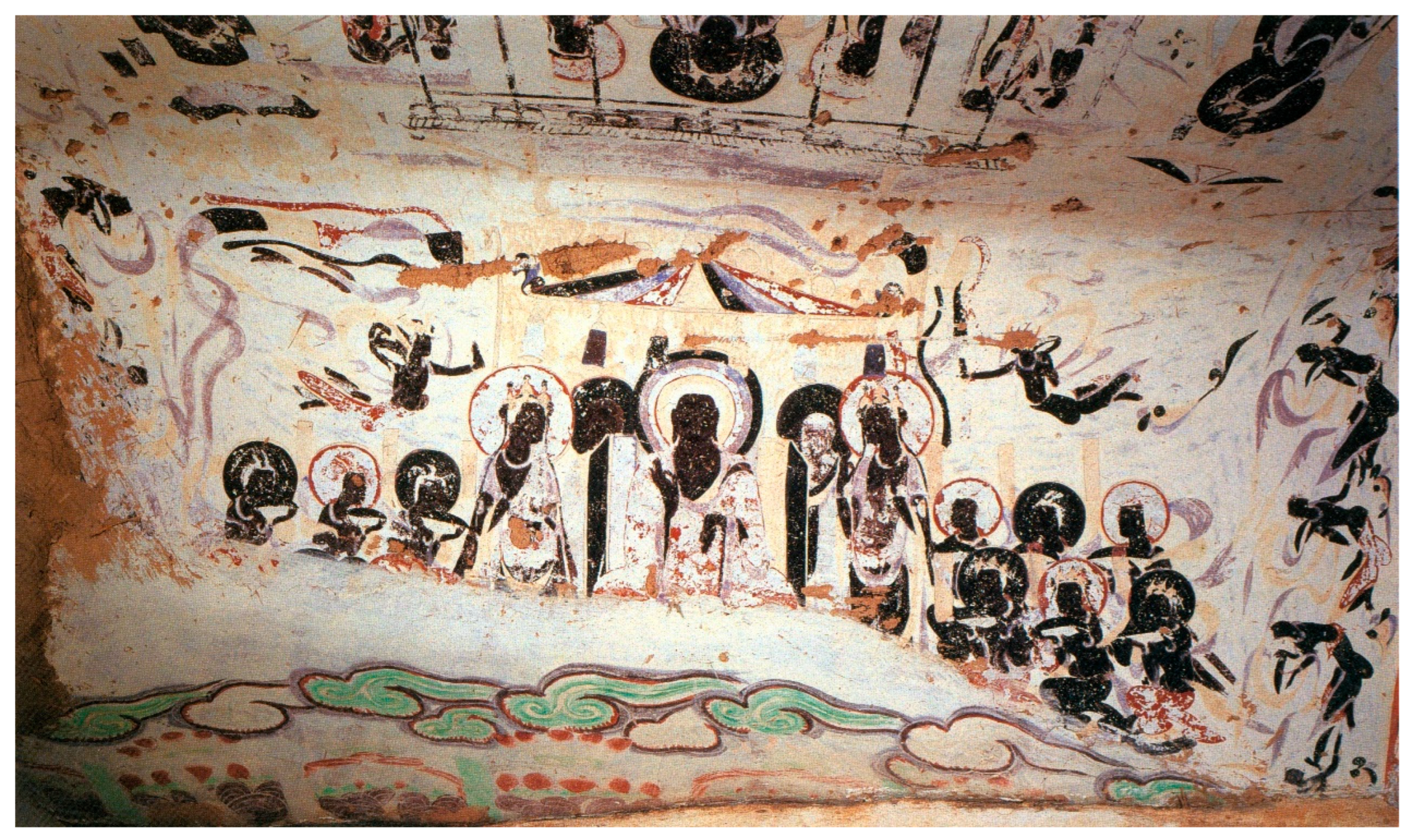

3.1.2. On the East Slope of the Ceiling of the West Wall of Cave 433

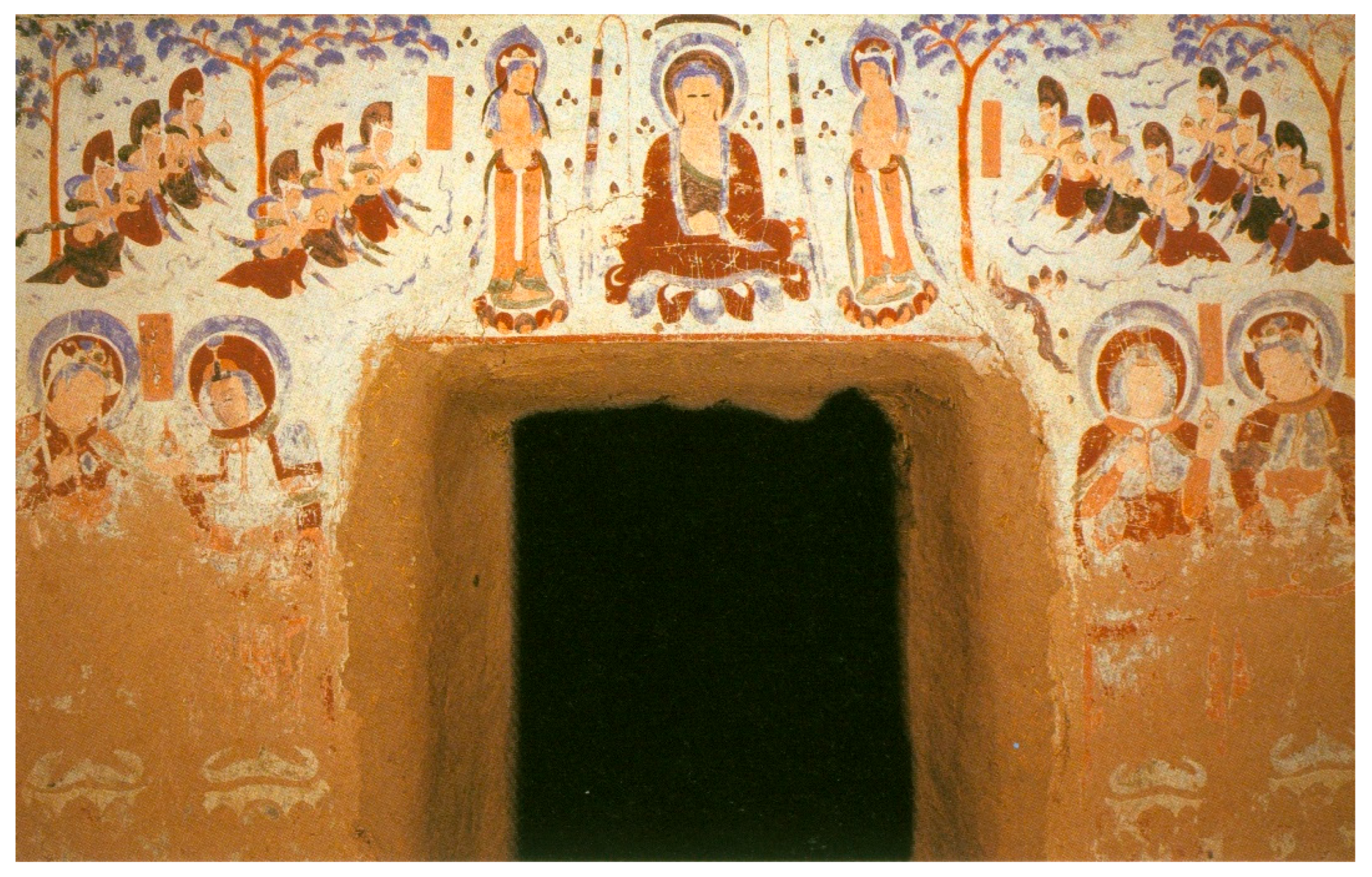

3.1.3. On the East Slope of the Ceiling of the West Wall of Cave 436

- (a)

- The grand canopy that sheltered the Buddha, Bodhisattvas, and monks is decorated in a modern and colorful design. It almost gives out a flavor of a circus.

- (b)

- The multi-paneled screen is a new addition in this cave.

- (c)

- The dynamic “Dharma-preaching” mudra with the left hand pointing to the feet becomes the convention of the Medicine Buddha and this is the earliest appearance in Dunhuang Grottos.

- (d)

- The emergence of the monks in this cave showed the inception of a standard Buddha’s full retinue in the future.

- (e)

- Another new addition, the cartouches for the Demigods, indicates either the rising inquiry of the identities of these twelve Demigods from the audience, or the unfamiliarity of the craftsmen and/or monks responsible for this cave of these Demigods. Even though none of the names remains visible now, it is clear that the cartouches are not big, and sometimes there is probably not enough room to write their entire names.

- (f)

- It is interesting that neither 417, 433, nor 436 presented both the lamps and flags that are mentioned in all the Medicine Buddha Sutras. On the other hand, these three caves showed a progressive process from the lamps to the flags.

3.1.4. On the East Wall of Cave 394

- (a)

- As the first representation of the Four Heavenly Kings in the Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableau in Dunhuang, not only they and the Twelve Demigods are depicted in different areas on the wall, but the two beings are shown in totally different attires and postures. However, probably due to the similar Dharma-protecting functions of the Heavenly Kings and the Demigods, they are portrayed together in later periods in Dunhuang.

- (b)

- The most central ensemble of “Medicine Buddha + two leading Bodhisattvas + two magical long flags” emphasizes the importance of these powerful flags since they are closer to the Buddha than the Twelve Demigods.

3.2. Discussions of Themes

3.2.1. Locations

3.2.2. Thematic Imagery

- (1)

- The Medicine Buddha

- a.

- Clothing: Three (Caves 417, 433, and 394) out of four depictions of the Medicine Buddha during the Sui Dynasty in Dunhuang dress in red robes while the other one’s (Cave 436) robe is faded into whitish color.

- b.

- Mudras: Three (Caves 417, 433, and 436) out of four depictions of the Medicine Buddha during the Sui Dynasty in Dunhuang are in the dynamic Dharma-preaching” mudra while Cave 436 is the first cave that shows the Medicine Buddha in His conventional mudra with His left hand facing downward. Yet, in Cave 394, the Medicine Buddha is shown with a static dyana mudra. As the first 3 out of the long 65 decades that the Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableaux are depicted, minor variations in details show that these four representations are in their early inaugurating stage.

- (2)

- Attendant Bodhisattvas:

- a.

- Only the earliest Cave 417 shows the Eight Bodhisattvas as the attendant Bodhisattvas, which make the composition more rectangular. The Eight Bodhisattvas are there to receive the newly deceased and show them their ways to the Pure Lands of their choosing.

- (3)

- Twelve Demigods

- (4)

- Lamps and Long Flags

4. Conclusions

4.1. Texts

- The time, locale, and the major participants of this said Dharma talk: Under the musical tree at Vaiśālī, Bodhisattva Manjushri initiated this Dharma talk by asking Buddha questions.

- The Twelve Great Vows: The sequence and the contents of these twelve vows are highly consistent yet there is a minor variation in the content of the eighth one. In the earliest translation, edition S, the eighth vow is to set all sentient beings free from ignorance, while Dharmagupta, the Sui Dynasty monk pioneer translates that all women are to be reborn into men in their future lives. And yet, all four of them all vow to reach the same goal, to comprehend the Dharma, and obtain the ultimate wisdom.

- The two foremost Bodhisattvas: Even though the translated names of them are not identical, they are all related to the Sun Light and the Moon Light. And again, the Sui Dynasty translation is the first to specify that these two Bodhisattvas are the most senior two out of all the numerous Bodhisattvas.

- The Eight Bodhisattvas: All four editions agree that the function of these eight Bodhisattvas is to lead the newly deceased to the Amitabha Buddha’s Pure Land of the West. All four editions describe the grandeurs lotus pond as the future local of rebirth, yet edition D rendered in the Sui Dynasty is the first to clarify that their future destination would be Amitabha’s Pure Land of the West. When first trying to introduce the Medicine Buddha to Dunhuang during the Sui Dynasty, evoking the Amitabha Buddha’s Pure Land seems like a good tactic. Nonetheless, the Medicine Buddha’s Pure Land of the East does not seem to gain any foothold as the Medicine Buddha Sutra become more popular.

- The Four Heavenly Kings: All four translations explain their roles as the Dharma protectors. The Sui Dynasty edition D shows the earliest record that these Kings can resurrect the dead.

- The lamps and long flags, the magical instruments that prolong people’s lives:

- (1)

- Seven-layered lamp with seven candles on each layer,

- (2)

- Five-colored flags which are 49 chi in length.

- 7.

- The Twelve Demigods: All four editions reassure devotees that those who recite the Medicine Buddha Sutra will be well-protected by these twelve Demigods. Despite slight variations in transliterating the names of these Demigods, the latter two editions translated in the Tang Dynasty seem to follow edition D quite closely.

4.2. Imagery

- List of caves in chronological sequence: 417, 433, 436, and 394.

- Locations: (1). The earlier three are depicted on the ceilings of the niches on the west wall while the last one is painted on the east wall. (2). The variation in sizes and height of the representations indicates the development phase of this theme in Dunhuang.

- The Medicine Buddha: (1). The three earlier ones are in red clothing while the last one is in faded whitish clothing. (2). Murda: The three earlier ones are in dynamic Dharma-preaching mudra while the last one is in dyana mudra.

- Attendant Bodhisattvas: The first one is the Eight Bodhisattvas while the latter three become the two leading Bodhisattvas.

- Twelve Demigods: All four depictions show these Twelve Demigods and suggest that they are essential to this sutra.

- Four Heavenly Kings: The latest Cave 394 portrays the Four Heavenly Kings by the entrance to embody their Dharma-protecting nature. To present the Four Heavenly Kings with the Twelve Demigods together further emphasize their function to secure the Dharma.

- Lamps and flags: Even though they sound very powerful in the sutra, the earlier two caves only depict lamps while the latter two only portray flags. Therefore, during the Sui Dynasty, the flags replace the lamps to represent the imagery as the magical instrument.

4.3. Conjecture of the Textual Source of the Imagery in Dunhuang

- Cartouches of the Twelve Demigods in Cave 436. Even though the inscriptions are all gone, the outlines of the cartouches are still visible. Judging from the small-sized cartouches, the names would not be too long. Therefore, it is more likely that the image is based on edition S which has the shorter names for Demigods, only three characters.

- The earliest Cave 417 depicted Eight Bodhisattvas rather than the two leading Bodhisattvas. Śrīmitra states that the two foremost Bodhisattvas are the Ekajātipratibaddha Bodhisattvas without explaining who they are. On the other hand, he explains in detail that the Eight Bodhisattvas can lead the newly deceased to the Pure Land of their choice without being through eight Ordeals. This suggests that the monks and painters are more familiar with the Eight Bodhisattvas rather than the two leading Bodhisattvas.

- When it comes to the magical life-prolonging instruments, the earliest edition S is the only one that does not mention the seven statues of Medicine Buddha in the festival. All the Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableaux made after the Sui Dynasty depict seven Medicine Buddha statues indicates that the Dharmagupta edition is only available in the Dunhuang area after the Tang Dynasty. In other words, Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableaux made during the Sui Dynasty were based on the earliest edition S.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Sanskrit is from the sutras found in Gilgit in 1937. See Tsai Yaoming’s lecture notes on the Sanskrit Sutra of Medicine Buddha, https://homepage.ntu.edu.tw/~tsaiyt/pdf/f-2020-16.pdf. Last retrieved on 23 September 2025. |

References

- Bai, Wen 白文. 2010. Guanzhong Tangdai Yaoshi fo zaoxiang tuxiang yanjiu 關中唐代藥師佛造像圖像研究 [On the Medicine Buddha Imagery in the Guanzhong Area during the Tang Dynasty]. Shanxi Shifan Daxue Xuebao (Zhexue Shehui Kexye Ban) 陜西師範大學學報 (哲學社會科學版) Journal of the Shanxi Normal University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition) 2: 148–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Qing 常青. 2021. Chengdu Wanfosi Yaoshi foxiang yu Nanbeichao Yaoshi fo xinyang 成都萬佛寺藥師佛像與南北朝藥師佛信仰 [The Medicine Buddha Imagery at the Wanfo Temple in Chengdu and the Medicine Buddha Belief During the North and South Dynasties]. Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 Palace Museum Journal 7: 4–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jia 陳佳, Lin Chen 林晨, and Zhuannan Chen 陳轉男. 2022. Sichuan Jiajiang Niuxian si Xinjian Yaoshi bian kanxiang kaoshi 四川夾江牛仙寺新見「藥師變」龕像考釋 [On the New Found Medicine Buddha Tableau in the Niuxian Temple, Jia River, Sichuan]. Fayin 法音 Dharma Sound 10: 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, Yanni 黨燕妮. 2013. Zhonggu shiqi Dunhuang diqu de Yaoshi fo Xinyang 中古時期敦煌地區的藥師佛信仰 [The Medieval Chinese Medicine Buddha Belief at Dunhuang]. Nanjing Xiaozhuang Xueyuan Xuebao 南京曉莊學院學報 Journal of Nanjing Xiaozhuang College 6: 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Guangchang 方廣錩. 2012. Guotu Dunhuang yishu ‘Yaoshiliuliguang rulai benyuan gongde jing’ xulu 國圖敦煌遺書 《藥師琉璃光如來本願功德經》敘錄 [Medicine Buddha Lapis Lazuli Light Tathagata Original Vow Merit Sutra in the Dunhuang Documents collection at the National Library]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 Dunhuang Research 3: 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Guangchang 方廣錩. 2014. Yaoshi fo tanyuan—dui ‘Yaoshifo’ hanyi fodian de wenxianxue kaocha 藥師佛探源——對「藥師佛」漢譯佛典的文獻學考察 [On the Medicine Buddha, a Textual Research on the Chinese Translation of the ‘Medicine Buddha’]. Zongjiaoxue Yanjiu 宗教學研究 Religious Studies 4: 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Guangchang 方廣錩. 2015. Guanyu Han, Fan Yaoshi jing de ruogan wenti 關於漢、梵《藥師經》的若干問題 [Issues on the Chinese and Sanskrit Medicine Buddha Sutras]. Zongjiao Xue Yanjiu 宗教學研究 Religious Studies 2: 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Guangchang 方廣錩. 2016. Zaitan guanyu Han, Fan Yaoshi jing de ruogan wenti 再談關於漢、梵《藥師經》的若干問題 [Issues on the Chinese and Sanskrit Medicine Buddha Sutras Revisited]. Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 Studies in World Religions 6: 189–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Yongli 符永利. 2015. Chuanyu diqu Tangsong Yaoshi fo kanxiang de chubu kaocha 川渝地區唐宋藥師佛龕像的初步考察 [The First Inquiry of the Medicine Buddha Imagery During the Tang and the Song Dynasties in the Sichuan Area]. Shikusi Yanjiu 石窟寺研究 Studies of the Cave Temples 6: 48–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Wenhe 胡文和. 1988. Sichuan moyai zaoxiang zhong de Yaoshi bian he Yaoshi jingbian 四川摩崖造像中的《藥師變》和《藥師經變》[The Medicine Buddha Tableau and the Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableau in the Cliff Imagery in Sichuan]. Wenbo 文博 Relics and Museology 2: 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Rong 黃蓉. 2017. Shengtang ‘Yaoshi yongyang yishi’ tuxiang yanjiu—yi Dunhuang yisiba ku weili 盛唐「藥師供養儀式」圖像研究——以敦煌莫高窟第一四八窟為例 [A Case Study of the Cave 148 of the Dunhuang Grottos, On the Image of the Medicine Buddha Offering Ritual]. Rongbao Zhai 榮寶齋 Rong Bao Zhai 4: 148–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Yongjun 霍永軍. 2011. Xixia bihua Yaoshi foxiang de chuxian yu zaoxiang tedian 西夏壁畫藥師佛像的出現與造像特點 [The Emergence and the Characteristics of the Medicine Buddha Imagery in Xixia]. Duzhe Xinshang (Likun Ban) 讀者欣賞 (理論版) Readers Appreciation (Theory Edition) 1: 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Lin 江琳. 1990. Mogao ku Tubo, Guiyijun Zhang shi shiqi Yaoshijingbian zhong yuewu de yanjiu 莫高窟吐蕃、歸義軍張氏時期《藥師經變》中樂舞的研究 [On the Dancers and Musicians in the Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableau During the Tibet and the Guiyi Prefecture Zhang Periods at the Mogao Grottos]. Dunhuangxue Jikan 敦煌學輯刊 Journal of Dunhuang Studies 2: 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yu-min 李玉珉. 1986. The Pensive Imagery Revisited, The National Palace Museum Research Quarterly, 3rd ed. Taipei: National Palace Museum Research Quarterly, vol. 3, pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yu-min 李玉珉. 1990. Dunhuang Yaoshi jingbian yanjiu 敦煌藥師經變研究 [On the Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableaux]. Gugong Xueshu Jikan 故宫學術季刊 The National Palace Museum Research Quarterly 7: 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xiaorong 李小榮. 2002. Lun Sui Tang Wudai zhi Songchu de Yaoshi xinyang—yi Dunhuang wenxian we zhongxin 論隋唐五代至宋初的藥師信仰——以敦煌文獻為中心 [Medicine Buddha Faith in Suei-Tang and Five Dynasties: A Dung Huang Literature Review]. Pumen Xuebao 普門學報 Universal Gate Buddhist Journal 11: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Wendong 劉文東. 2012. Daying bowuguan can juanhua Yaoshi jingtubian zhi pusaxingxiang kaoxi 大英博物館藏絹畫 《藥師凈土變》 之菩薩形象考析 [The Bodhisattva Images of the Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableau Silk Painting of the British Museum]. Meishu Xuebao 美術學報 Art Journal 4: 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yanhong 劉豔紅. 2015. Dunhuang ben “Yaoshi liuliguang rulai benyuan gongde jing” xieben kao 敦煌本《藥師琉璃光如來本願功德經》寫本考 [On the Copies of the Medicine Buddha Lapis Lazuli Light Tathagata Original Vow Merit Sutra from Dunhuang Grottos]. Shuoshi Lunwen 碩士論文 [Master’s thesis], Zhejiang Shifan Daxue Zhongguo Gudian Wenxianxue 浙江師範大學中國古典文獻學 [Department of the Chinese Classics, Zhejiang Normal University], Jinghua, China. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Huaqing 羅華慶. 1989. Dunhuang bihua zhong de Dongfang Yaoshi jingbian 敦煌壁畫中的 《東方藥師凈土變》 [The Medicine Buddha Pure Land of the East Tableaux in Dunhuang Grottos]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 Dunhuang Studies 2: 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, Defang 米德昉. 2013. Dunhuang bihua xifang jingtubian yu Yaoshi jingtubian duizhi chengyin fenxi 敦煌壁畫西方凈土變與藥師凈土變對置成因分析 [Analysis of the Pure Land of the West Tableaux and the Medicine Buddha Pure Land Tableaux in Relations to Their Opposite Locations at Dunhuang Grottos]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 Dunhuang Studies 5: 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Xueyang. 2025. Visualizing the Spirit Consciousness: Reinterpreting the Medicine Buddha Tableau in Mogao Cave 220 (642 CE). Religions 16: 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Wutian 沙武田. 2015. Yifu zhenguide Tang Changan yejian wuyue tuan—yi Mogaoku di 220 ku Yaoshijingbian yuewutu zhong deng weizhongxin de jiedu 一幅珍貴的唐長安夜間樂舞圖——以莫高窟第220窟藥師經變樂舞圖中燈為中心的解讀 [A Precious Night Entertainment at Changan Painting of the Tang Dynasty, An Interpretation Focusing on the Lamps in the Music and Dancing Scene of the Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableau in Mogao Cave 220]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 Dunhuang Studies 5: 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Wenyao 史文瑤. 2014. Tangdai Sichuan Anyue shiku Zhong de Yaoshibian he Yaoshijingbian yanjiu 唐代四川安岳石窟中的《藥師變》和《藥師經變》研究 [On the Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableaux and the Medicine Buddha Sutra in the Tang Dynasty Anyue Grottos]. Shuoshi Lunwen 碩士論文 [Master’s thesis], Huadong Shifan Daxue Yishushi Yanjiusuo 華東師範大學藝術史研究所 [Department of Art History, East China Normal University], Shanghai, China. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Yaoming. 2020. Study on the Sanskrit Bhaiṣajyaguru-vaiḍūryaprabha-rāja-sūtra. Available online: https://homepage.ntu.edu.tw/~tsaiyt/pdf/f-2020-16.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Wang, Huimin 王惠民. 1998. Dunhuang yishu zhong de Yaoshijingbian bangti digao jiaolu 敦煌遺書中的藥師經變榜題底稿校錄 [Collation of the Inscriptions in the Dunhuang Documents]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 Dunhuang Studies 4: 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Huimin 王惠民. 1999. ‘Dunhuang yishu zhong de Yaoshijingbian bangti digao jiaolu’ buyi 《敦煌遺書中的藥師經變榜題底稿校錄》補遺 [Addendum to the ‘Collation of the Inscriptions in the Dunhuang Documents]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 Dunhuang Studies 4: 161–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Huimin 王惠民, ed. 2002. Dunhuang Shiku Quanji 6 Milejing Huajuan 敦煌石窟全集6彌勒經畫卷 [The Complete Collection of Dunhuang Grottoes, Volume 6, Maitreya Sutra Painting Scroll]. Xianggang: Shangwu Yinshuguan 商務印書館 [Commercial Press]. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Huimin 王惠民. 2004. Dunhuang jingbianhua de yanjiu chengguo yu yanjiu fangfa 敦煌經變畫的研究成果與研究方法 [On the Results and Research Methods of the Sutra Tableaux at Dunhuang Grottos]. Dunhuangxue Jikan 敦煌學輯刊 Journal of Dunhuang Studies 2: 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Lijun 王麗君, and Jing Yu 余靖. 2022. Sichuan Anyue Muyushan xin faxian de Yaoshi jingbian kanxiang 四川安岳木魚山新發現的藥師經變龕像 [The Imagery of the Newly Found Medicine Buddha Niche in Muyu Mountain, Anyue, Sichuan]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 Dunhuang Studies 3: 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Meng 王夢. 2014. “Yaoshijing” yanjiu—yi “Yaoshi liuliguang benyuan gongdejing” weizhu 《藥師經》研究——以《藥師琉離光本願功德經》為主 [The Medicine Buddha Sutra, Focusing on the Medicine Buddha Lapis Lazuli Light Tathagata Original Vow Merit Sutra. Shuoshi Lunwen 碩士論文 [Master’s thesis], Sichuansheng Kexueyuan Minzu yu Zongjiao Yanjiusuo 四川省社科院民族與宗教研究所 [Research Institute of Nationalities and Religions, Sichuan Academy of Social Science], Chengdu, China. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yanyun 王艷云. 2003. Xixia bihua zhong de Yaoshi jingbian yu Yaoshi fo xingxiang 西夏壁畫中的藥師經變與藥師佛形象 [The Medicine Buddha Sutra Tableaux and the Imagery of the Medicine Buddha in Xixia]. Ningxia Daxue Xuebao (Renwen Shehui Kexue Ban) 寧夏大學學(人文社會科學版) Journal of Ningxia University (Social Science Edition) 1: 14–34. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Zhibin 謝志斌. 2018. Shier yaocha Xinyang de zucheng ji qi zhongguo hua xingtai 十二藥叉信仰的組成及其中國化形態 [The Twelve Yakshas Belief and Its Sinification]. Zongjiaoxue Yanjiu 宗教學研究 Studies on Religion 4: 137–47. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Liquan 許立權. 2014. Zhongguo Yaoshi fo xinyang yanjiu 中國藥師佛信仰研究 [Studies of the Medicine Buddha Belief in China]. Shuoshi Lunwen 碩士論文 [Master’s thesis], Shanxi Shida Zongjiaosuo 陝西師大宗教所 [Religious Studies, Shanxi University], Xian, China. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Weizhong 楊維中. 2014. Yaoshijing fanyi xinkao 《藥師經》翻譯新考 [Translation of the Medicine Buddha Sutra Revisited]. Xinan Minzu Daxue Xuebao 西南民族大學學報 (人文社會科學版) Journal of the Southwest Minzu University (Humanities and Social Science Edition) 6: 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Chongxin 姚崇新. 2015. Jingtu de xiangwang haishi xianshi de xiji?—zhonggu Zhongguo Yaoshi Xinyang neihan zaikao 淨土的嚮往還是現世的希冀?——中古中國藥師信仰內涵再考察 [Longings for the Pure Land or the Worldly Wishes? Medieval Chinese Medicine Buddha Belief Revisited]. Dunhuang Tulufan Yanjiu 敦煌吐魯番研究 Journal of the Dunhuang and Turfan 2: 321–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yongquan 張湧泉, Yanhong Liu 劉艷紅, and Yu Zhang 張宇. 2014. Dunhuang benYaoshi ruliguang rulai benyuan gongde jing 敦煌本 《藥師琉璃光如來本願功德經》 殘卷綴合研究 [Fragments of the Medicine Buddha Lapis Lazuli Light Tathagata Original Vow Merit Sutra from Dunhuang Grottos]. Zhejiang Shifan Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) 浙江師範大學學報(社會科學版) Zhejiang Normal University Journal (Social Science Edition) 6: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

| Date/Period | Translator | Title | Volume | Taisho CBETA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eastern Jin (317–322) | Śrīmitra | Foshuo guanding bachu guozui shengsi dedujing (Foshuo guandingjing) (edition S) | 1 | V. 21 N.1331 |

| 2 | Liu Song (457) | Huijian | Yaoshi liuliguang jing | 1 | N/A |

| 3 | Sui (615) | Dharmagupta | Foshuo yaoshi rulai benyuan jing (edition D) | 1 | 14 N. 449 |

| 4 | Tang (650) | Xuanzang | Bhaiṣajyaguru-vaiḍūryaprabha-rāja-sūtra (edition X) | 1 | 14 N. 450 |

| 5 | Tang (707) | Yijing | Saptatathāgatapūrvapraṇidhānaviśeṣavistara (edition Y) | 2 | 14 N. 451 |

| Element | Edition S | Edition D | Edition X | Edition Y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | time | One time一時 | One time一時 | One time一時 | One time一時 |

| 2 | location | Vaiśālī 維耶離 Under the musical tree 音樂樹下 | Vaiśālī 毘舍離國 Under the tree of music 樂音樹下 | Vaiśālī 廣嚴城 Under the tree of music 樂音樹下 | Vaiśālī 廣嚴城 Under the tree of music 樂音樹下 |

| 3 | speaker | The Buddha 佛 | Bhagavat 婆伽婆 | Bhagavat 薄伽梵 | Bhagavat 薄伽梵 |

| 4 | enquirer | Manjushri 文殊師利 Knelt on both knees, palms joined together with interlocking thumbs 長跪叉手合掌 | Manjushri 曼殊室利 Knelt on the right knee with palms joined together while bowing 右膝著地, 合掌曲躬 | Manjushri 曼殊室利 Knelt on the right knee, bowed with palms joined together 右膝著地, 曲躬合掌 | Manjushri 曼殊室利 Knelt on the right knee with palms joined together 右膝著地,合掌 |

| Lamps | Flag | |

|---|---|---|

| Edition S | Seven-layered lamp… There are seven candles in each layer, and each layer is like the wheel of a cart… 49 lamps | the long, 5-colored flag that could prolong lives |

| Edition D | Light 49 lamps… have seven Medicine Buddha’s statues made, each with seven lamps as big as the wheel of a cart in the front, or keep the lamps lit for 49 days. | Make the long, 5-colored flag in 49 chi long |

| Edition X | Light the Seven-layered lamp… light 49 lamps…have seven Medicine Buddha’s statues made, each with the seven lamps each as big as the wheel of a cart in front for 49 days. | Hang up the 5-colored long flag that could prolong lives. The flag is 49 vitastf long. |

| Edition Y | Light 49 lamps… Have seven Medicine Buddha’s statues made, each with seven lamps each in the shape of the wheel of a cart in front, keep the lamps lit until the night of the 49the day. | Make the colorful flags in 49 chi long. |

| Edition S Demigods | Edition D Yakṣa Generals | Edition X Yakṣa Generals | Edition Y Yakṣa Generals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Kiṃbhīro | 金毗羅 Jinpiluo | 宮毘羅大將 Gongliluo dajiang | 宮毘羅大將 Gongpiluo dajiang | 宮毘羅大將 Gongliluo dajiang |

| 2. Vajro | 和耆羅 Heqiluo | 跋折羅大將 Bazheluo dajiang | 伐折羅大將 Anzheluo dajiang | 跋折羅大將 Bazheluo dajiang |

| 3. Mekhilo | 安陁羅 Anyiluo | 迷佉羅大將 Miquluo dajiang | 迷企羅大將 Miqiluo dajiang | 迷企羅大將 Miqiluo dajiang |

| 4. Antilo | 摩尼羅 Moniuo | 安捺羅大將 Annailuo dajiang | 安底羅大將 Andiluo dajiang | 頞儞羅大將 Anniluo dajiang |

| 5. Anilo | 宋林羅 Songlinluo | 安怛羅大將 Antaluo dajiang | 頞儞羅大將 Anniluo dajiang | 末儞羅大將 Moniluo dajiang |

| 6. Saṇṭhilo | 弥祛羅 Miquluo | 摩涅羅大將 Monieluo dajiang | 珊底羅大將 Shandiluo dajiang | 娑儞羅大將 Suoniluo dajiang |

| 7. Indalo | 婆那羅 ponaluo | 因陀羅大將 Intuoluo dajiang | 因達羅大將 Yindaluo dajiang | 因陀羅大將 Yindaluo dajiang |

| 8. Pāyilo | 摩𠇾羅 Moxiuluo | 波異羅大將 Poyiluo dajiang | 波夷羅大將 Poyiluo dajiang | 波夷羅大將 Poyiluo dajiang |

| 9. Mahālo | 照頭羅 Zhaotuoluo | 摩呼羅大將 Mohuluo dajiang | 摩虎羅大將 Mohuluo dajiang | 薄呼羅大將 Bohuluo dajiang |

| 10. Cidālo | 毗伽羅 Piqieluo | 真達羅大將 Zhendaluo dajiang | 真達羅大將 Zhendaluo dajiang | 真達羅大將 Zhendaluo dajiang |

| 11. Caundhulo | 囙持羅 Jiongteluo | 招度羅大將 Zhaoduluo dajiang | 招杜羅大將 Zhaoduluo dajiang | 朱杜羅大將 Zhuduluo dajiang |

| 12. Vikalo | 真陁羅 Ahenyiluo | 鼻羯羅大將 Bijieluo dajiang | 毘羯羅大將 Pijieluo dajiang | 毘羯羅大將 Pijieluo dajiang |

| Cave | Location | Attendant Bodhisattvas | Twelve Demigods | Lamp | Flag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 417 | Ceiling of the Niche, West wall | N/A | Y | 1 | N/A |

| 433 | East slope of the Niche, West wall | Y | Y | 2 | N/A |

| 436 | East slope of the Niche, West wall | Y | Y | N/A | 2 |

| 396 | East wall, above the entrance | Y | Y | N/A | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chien, P.-c. On Intermediality of the Medicine Sutras and Their Imagery During the Sui Dynasty at Dunhuang. Religions 2026, 17, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel17010069

Chien P-c. On Intermediality of the Medicine Sutras and Their Imagery During the Sui Dynasty at Dunhuang. Religions. 2026; 17(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel17010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleChien, Pei-chi. 2026. "On Intermediality of the Medicine Sutras and Their Imagery During the Sui Dynasty at Dunhuang" Religions 17, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel17010069

APA StyleChien, P.-c. (2026). On Intermediality of the Medicine Sutras and Their Imagery During the Sui Dynasty at Dunhuang. Religions, 17(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel17010069