Abstract

The central image of Yakushi Nyorai in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji is a statue closely associated with the imperial household. This study centers on the iconography of the Four Directional Deities and grotesque figures on the pedestal of this statue, while drawing comparative references to related imagery from both China and Japan, in order to reassess the intended meaning behind the iconographic program and, by extension, the original purpose of the statue’s creation. The analysis suggests that the twelve grotesque figures, enclosed within bell-shaped niches on all four sides of the pedestal’s midsection, likely represent the Twelve Divine Generals, who collectively symbolize the Pure Land of Yakushi in conjunction with the Medicine Buddha above. The grotesque figures situated outside the niches on the north and south faces take on the posture of supportive yakṣa and additionally carry the iconographic attributes of beast-demons. Positioned at the lowest register, the Four Directional Deities are interpreted as forming a directional entourage of ascension—either to immortality or to rebirth in the Pure Land. Taken together, these visual elements strongly suggest that the central image of Yakushi Nyorai may have been created as a posthumous votive offering for the soul of Empress Jitō.

1. Introduction

Yakushi-ji, located in Nishikyo-cho, Nara City, is recognized as one of the Seven Great Temples of Nara. According to the Nihon Shoki (日本書紀, Chronicles of Japan), in the ninth year of Emperor Tenmu’s reign (AD 680), Emperor Tenmu 天武天皇 initiated the construction of Yakushi-ji in the capital Fujiwara-kyō 藤原京, dedicating the temple as a votive act for the recovery of his ailing empress, who later ascended the throne as Empress Jitō 持統天皇, and ordained one hundred monks as part of the vow.1 Following Emperor Tenmu’s death in AD 686, the responsibility for supervising the temple’s construction passed to Empress Jitō. Under her patronage, the temple had reached near completion by the second year of Monmu (AD 698).2 In 710, the capital was transferred from Fujiwara-kyō to Heijō-kyō 平城京. Subsequently, Yakushi-ji was likewise relocated to Heijō-kyō in 718.3 The original Yakushi-ji constructed in Fujiwara-kyō is now referred to as Hon-Yakushi-ji 本薬師寺 and is located in present-day Kashihara City, Nara Prefecture, where now only a few foundation stones and remnants of small-scale constructions remain.

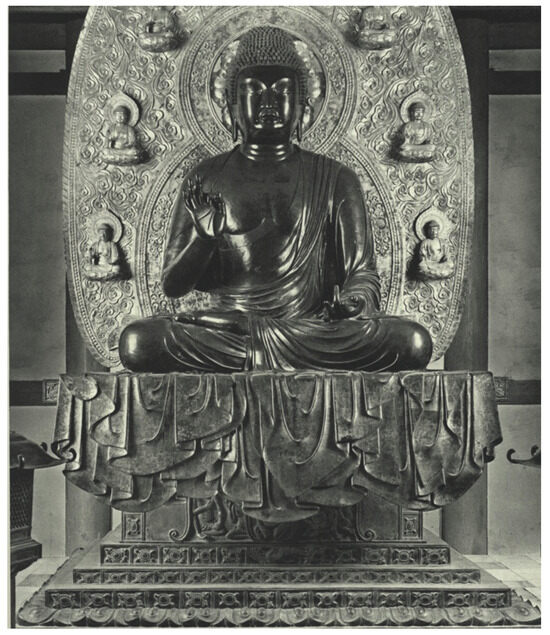

The most renowned sculptural ensemble at Yakushi-ji is the Yakushi Triad enshrined in the Kondō 金堂, comprising a seated central figure of Yakushi Nyorai 薬師如来 (Bhaiṣajyaguru) (Figure 1) flanked by standing statues of the attendant Bodhisattvas Nikkō (Sūryaprabha) and Gakkō (Candraprabha). All three statues are cast in gilded bronze, exhibiting exceptional craftsmanship and are remaining in a well-preserved condition. They are widely regarded as among the finest examples of gilt-bronze Buddhist statues in Japan. Previous scholarship has engaged in considerable debate regarding the dating of these statues. In a separate article, I have undertaken a comparative analysis of their stylistic and formal characteristics in relation to contemporary Buddhist sculptures from the Tang dynasty and early Japan. This study concludes that the statues were likely completed after the relocation of Yakushi-ji to Heijō-kyō in AD 718, a position that corresponds with the fifth interpretive view in prior scholarship, more specifically, the Yōrō to Shinki periods (AD 718–726) (Yao 2022, pp. 71–82).

Figure 1.

Statue of Yakushi Nyorai (Central Buddha) at the Kondō, Yakushi-ji, Nara. Retrieved from: Nara Rokudaiji Taikan Kankōkai (1970). The Great View of the Six Major Temples of Nara: Yakushi-ji, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, p. 72.

In addition to the exquisite central Buddha statue itself, the pedestal upon which it rests warrants particular attention. Cast in copper, the pedestal is structured in the “Xuan” character base 宣字座 and features iconography on all four sides, including depictions of the Four Directional Deities 四神 and grotesque figures 異形像. Such visual elements are unparalleled in extant Buddhist sculptural works in either China or Japan, marking this pedestal as a singular example within the corpus of East Asian Buddhist art. The meaning of this iconographic program has been the subject of considerable discussion. Scholars such as Masaaki Matsuura 松浦正昭 (Matsuura 2004, pp. 78–79). and Arisu Tobana 戸花亜利州 (Tobana 2009, pp. 51–74) have focused on the grotesque figures, interpreting the pedestal as a visual expression of themes from the Suvarṇaprabhāsottama Sūtra (Golden Light Sūtra). Cynthea J. Bogel (Bogel 2021, pp. 141–66) has proposed that the pedestal was a carefully constructed “cosmic scene” to visually express articulation of a sinicized imperial consciousness as developed by the Japanese court at the turn of the eighth century. As mentioned, the statues are intimately connected to the imperial household, and their design likely adhered to a carefully devised program. It is thus reasonable to infer that the imagery adorning the pedestal bears a direct relationship to the underlying intent behind the statues’ creation. Accordingly, this paper centers on the Four Directional Deities and the grotesque figures depicted on the pedestal of the central Buddha in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji. Through a close examination of their iconography, and in conjunction with the historical context surrounding the statue’s creation, it aims to reassess the original intent behind the production of this imperially sponsored image.

1.1. Iconographic Composition of the Pedestal for the Yakushi Nyorai Statue, the Central Buddha in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji

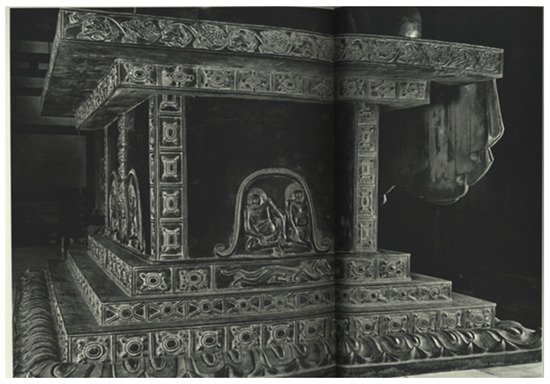

The pedestal of the central Yakushi Buddha (Figure 2) in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji consists of three components: the upper frame, the waist section, and lower frame. The overall form of the pedestal takes the shape of an eight-tiered “Xuan” character base 宣字座. The upper frame is subdivided into two distinct sections: the upper part is ornamented with grapevine arabesque motifs, while the lower portion features a decorative band of patterns. The lower frame, including some gem-like patterns, is composed of five distinct sections. The upper segment is adorned with a band identical to that which appears in the lower portion of the upper frame. Encircling the four sides of the pedestal’s waist are fourteen carved grotesque figures, each rendered in a variety of dynamic poses. The uppermost section of the lower frame connects to the waist, with low-relief figures of Four Directional Deities in the center: Vermilion Bird 朱雀, Azure Dragon 青龍, Black Tortoise 玄武, and White Tiger 白虎.

Figure 2.

Pedestal of the Central Buddha, Yakushi-ji, Nara. Retrieved from: Nara Rokudaiji Taikan Kankōkai (1970), The Great View of the Six Major Temples of Nara: Yakushi-ji, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, pp. 104–5.

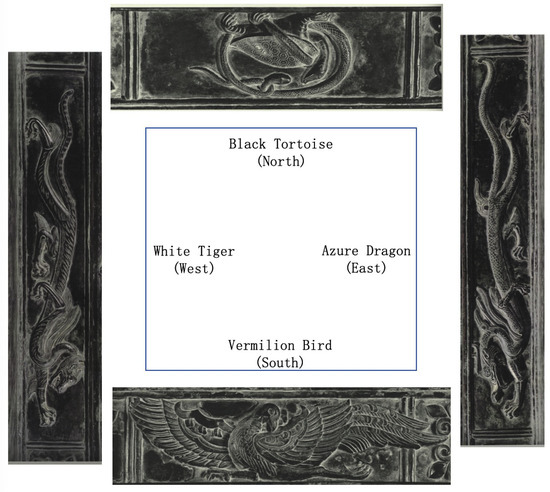

1.2. The Four Directional Deities (Figure 3)

Taking the Vermilion Bird (South) positioned on the front face of the pedestal as the point of reference, the placements of Azure Dragon (East), Black Tortoise (North), and White Tiger (West) align perfectly with the cardinal directions traditionally symbolized by the Four Directional Deities.

The Vermilion Bird, positioned on the front (south) side of the pedestal, is depicted in a frontal stance with three tail feathers behind it. Its head is turned back toward the left, in the direction of its eastward-pointing tail. The wings are fully outspread and the legs extended, capturing the dynamic moment of takeoff. This depiction of the Vermilion Bird in the act of taking flight closely parallels representations found in the Kitora Tomb キトラ古墳, a point that will be discussed later in this study.

On the right side of the pedestal, which corresponds to the east and situated to the right of the central deity, the Azure Dragon is depicted facing south toward the Vermilion Bird and rendered with scales. Its antlers bifurcate like those of a deer, and its upper lip is raised to reveal a long tongue that protrudes outward, with the tip curling upward. and features a single pronounced bend, adorned with an X-shaped necklace. Positioned behind the neck is a fire pearl. Wings emerge where the front legs join the body, with additional short wings located at the joints of both the front and rear legs. Another fire pearl is situated above the midsection of the body. The tail is long and extends backward. This depiction diverges notably from those found in the Kitora Tomb and the Takamatsuzuka Tomb 高松塚古墳, where the Azure Dragon’s tail typically curls around the hind legs and ascends upward.

The White Tiger, located on the left, corresponding to the west and the central Buddha’s left-hand side, initially appears strikingly similar to the Azure Dragon in form. However, its entire body is covered with fur rather than scales. The head is facing southward, facing the direction of the Vermilion Bird, with its mouth open to reveal sharp, prominent teeth. Long whiskers flow backward from behind the ears, and a mane of fur is present where the front legs connect to the body. Short fur also appears at the joints of both the front and rear legs. As with the Azure Dragon, the tail extends backward without curling around the back legs and rising upward.

On the back (north) face of the pedestal is the Black Tortoise, depicted with the turtle’s head facing west and the snake’s head entwined around it in a confrontational posture. The snake’s body coils around the turtle once, with its head and tail intertwined. This configuration is consistent with the representations of the Black Tortoise figures depicted in the Kitora and Takamatsuzuka Tombs, which will be elaborated later.

In addition to the pedestal of the central Buddha at Yakushi-ji, other extant examples of early representations of the Four Directional Deities in Japan include the mural paintings in both ancient Japanese tombs, as previously noted. The following discussion will examine the Four Directional Deities as depicted in these two funerary contexts.

Figure 3.

The Four Directional Deities on the pedestal, Yakushi-ji, Nara. Author’s arrangement based on Nara Rokudaiji Taikan Kankōkai (1970), The Great View of the Six Major Temples of Nara: Yakushi-ji, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, pp. 59–61+108.

1.3. Grotesque Figures

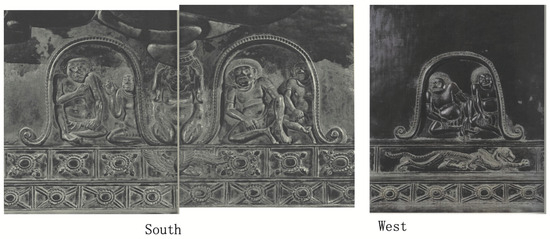

A total of fourteen grotesque figures are carved around the four sides of the pedestal’s waist section, which may be broadly categorized into two types. The first type comprises figures enclosed within bell-shaped niches 風字型龕 (Figure 4): on the east and west sides, each face contains a single panel housing two grotesque figures; on the south and north sides, two panels appear on each face, with two figures positioned within each panel. The second type consists of figures located outside the panels (Figure 5): situated between the two panels on the south and north sides is a single grotesque figure, kneeling and holding an object resembling a sacred pillar with both hands.

Figure 4.

Grotesque figures in the bell-shaped niches, Yakushi-ji, Nara. Author’s arrangement based on Nara Rokudaiji Taikan Kankōkai (1970), The Great View of the Six Major Temples of Nara: Yakushi-ji, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, pp. 106–7.

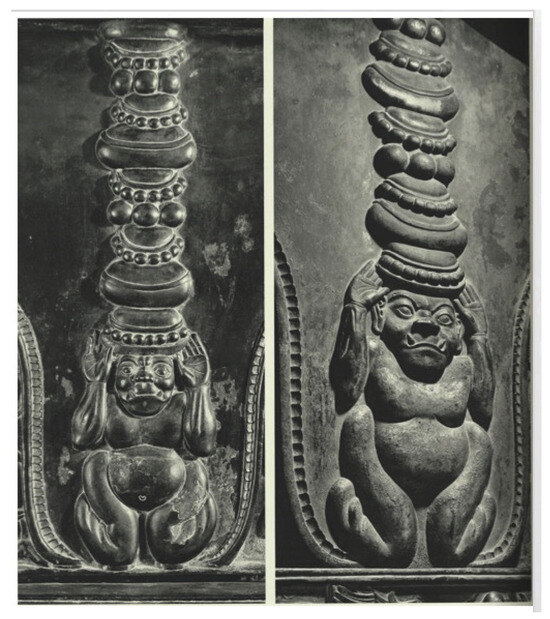

Figure 5.

Grotesque figures outside the bell-shaped niches, Yakushi-ji, Nara. Nara Rokudaiji Taikan Kankōkai (1970), The Great View of the Six Major Temples of Nara: Yakushi-ji, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, p. 109.

The twelve grotesque figures enclosed within the niches are unarmed and exhibit a range of hand gestures: some place their hands on their chests, others raise them, while still others rest them on their knees. Though dressed in loincloths, these figures are nearly nude. They are characterized by backward-combed curly hair, wide-open eyes, and prominently flaring nostrils. Several figures wear chest ornaments, armlets, and wristbands. While their bodily forms approximate human anatomy, a number of them possess sharp, exaggerated teeth, lending them a non-human or demonic appearance. In contrast, the two grotesque figures located outside the panels, which centrally positioned on the south and north sides, differ markedly in both posture and appearance. Unlike those within the niches, they are not dressed in loincloths and are rendered in peculiar kneeling poses, particularly in the lower limbs, where the legs from knee to toe resemble the hind flippers of a fur seal. Their hands possess five fingers, closely resembling human hands. Nevertheless, their heads are obscured by the raised arms and the pillar-like objects they grasp, making it impossible to determine the presence or absence of hair.

In general, the grotesque figures within and outside the bell-shaped niches exhibit notable differences in form and iconographic detail, indicating that they likely fulfilled distinct symbolic or functional roles within the overall sculptural program.

1.4. Additional Motifs

In addition to the Four Directional Deities images and grotesque figures, the pedestal of the central Buddha in the Kondō also features a rich array of decorative motifs, including grapevine arabesque patterns (tangcao 唐草) as well as several decorative, gem-like designs. The upper section of the pedestal’s upper frame is carved with grape vine, though on the front face this decoration appears only partially, as portions are concealed beneath the central Buddha’s hanging robe. Ryōichi Hayashi 林良一 has noted that this peculiar grapevine arabesque motif also appears on the silver-inlaid phoenix-and-beast-patterned mirror from the Hakutsuru Fine Art Museum, which is dated to the late early Tang period,4 as well as on the ceiling mural of Cave 217 (AD 707–710) at the Mogao Caves. Based on these parallels, he argues that such motif design on the pedestal of the central Buddha in the Kondō reflects the characteristic of such style in the Wu Zhou period (AD 684–705) during the late early Tang Dynasty (Hayashi 1959, p. 351). Shirō Itō 伊東史朗, drawing on comparative analysis with early Tang artifacts, such as the epitaph of Yŏn Namsaeng (dated to AD 679) and the flower-and-branch patterned mirror from the Sen-oku Hakukokan Museum, reaches a similar conclusion, identifying the grapevine arabesque motif on the Yakushi-ji pedestal as reflective of styles prevalent during the early Tang to the High Tang (Itō 1987, p. 13).

Moreover, the lower section of the upper frame on both the sides and rear faces of the pedestal, the vertical framing elements at the four corners of the waist section, and the upper, middle, as well as lower segments of the lower frame on all four sides are all embellished with rectangular bands. Within these rectangles, relief carvings of gem-like motifs, either rectangular or diamond-shaped, are consistently utilized, further contributing to the pedestal’s ornamental coherence.

2. The Four Directional Deities Imagery in Early Japan

The earliest documented reference to the Four Directional Deities in Japanese historical texts appears in the Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀, specifically in an entry dated to the first month of the first year of Emperor Monmu’s Taibō reign (AD 701).5 Additionally, the Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 records the appearance of an auspicious omen in AD 680.6 From these texts, it may be inferred that the concept and iconography of the Four Directional Deities had already transmitted to Japan by the late seventh century.

Among the extant examples in Japan, aside from the Four Directional Deities images depicted on the pedestal of the central Buddha at Yakushi-ji, the most renowned early representations are the murals found in the Kitora and Takamatsuzuka Tombs. Both tombs are located in Asuka Village, Nara, situated approximately one kilometer apart. Generally dated to the late Kofun period, their construction is estimated to have taken place between the late seventh and early eighth centuries.7 Owing to their rarity as mural tombs in Japan, along with the richness and refinement of their pictorial programs, these sites have long attracted considerable attention.

2.1. Four Deities Mural Paintings in the Kitora and Takamatsuzuka Tombs

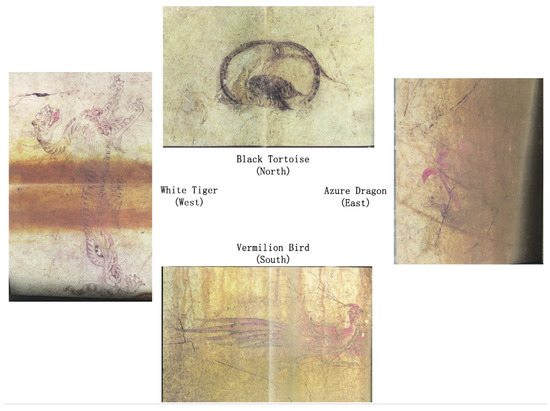

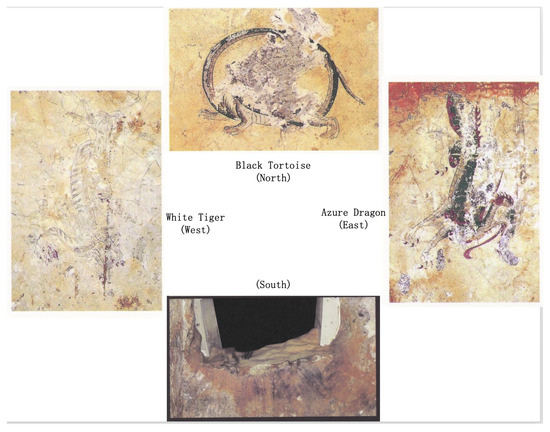

The murals of the Kitora Tomb are distributed across the ceiling and four walls. The ceiling depicts astronomical charts and representations of the Sun and Moon, while the four walls feature the Four Directional Deities (Figure 6) and the Chinese Zodiac Signs. At the center of each wall, a deity is depicted in its corresponding cardinal direction: the Azure Dragon in the east, the Vermilion Bird in the south, the White Tiger in the west, and the Black Tortoise in the north. Beneath each of the Four Directional Deities are three anthropomorphic figures with animal heads, representing the Chinese Zodiac Signs. On the east wall, the Azure Dragon faces rightward, oriented toward the Vermilion Bird on the south wall; conversely, the White Tiger on the west wall is depicted facing toward the Black Tortoise on the north wall. This cyclical arrangement among the Four Deities distinguishes the Kitora murals from conventional representations in Chinese tomb iconography, where the Azure Dragon and White Tiger typically face forward, in the direction of the Vermilion Bird situated on the south wall.

Figure 6.

The Four Directional Deities of the Kitora Tomb, Nara. Author’s arrangement based on Asuka Historical Museum (2006), Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Independent Administrative Institution, The Kitora Tomb and Unearthed Murals, Asuka Historical Museum, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Independent Administrative Institution, p. 15.

The murals of the Takamatsuzuka Tomb are painted on the ceiling and the east, west, and north (rear) walls of the stone chamber. The visual program includes secular figures, the Sun and Moon, the Four Directional Deities (Figure 7), and celestial imageries. On the east wall, running from south to north, appear a group of male characters, the Azure Dragon with the Sun positioned above it, and a group of female characters. The west wall mirrors such arrangement, but at its center is the White Tiger, accompanied by the Moon above. The north wall (rear wall) features the Black Tortoise. Although the southern mural is currently absent because of robbery during the Kamakura period, it is believed to have originally depicted the Vermilion Bird. Based on this hypothesis, the orientations of the Azure Dragon and White Tiger—on the east and west walls, respectively—would face toward the presumed Vermilion Bird on the southern wall, thereby conforming to the standard iconographic arrangement of the Four Directional Deities commonly found in ancient Chinese funerary murals.

Figure 7.

The Four Directional Deities of the Takamatsuzuka Tomb, Nara. Author’s arrangement based on Asuka Historical Museum (2006), Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Independent Administrative Institution, The Kitora Tomb and Unearthed Murals, Asuka Historical Museum, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Independent Administrative Institution, p. 15.

As noticed, the mural motifs of the Kitora Tomb and the Takamatsuzuka Tomb exhibit considerable thematic similarity, and their construction is generally believed to have occurred within a close chronological range. However, the Chinese Zodiac images appear exclusively in the Kitora Tomb, while representations of secular figures are found only in the Takamatsuzuka Tomb. Further, although the Four Directional Deities in both tombs share iconographic affinities, critical divergences in their formal depiction are also evident.

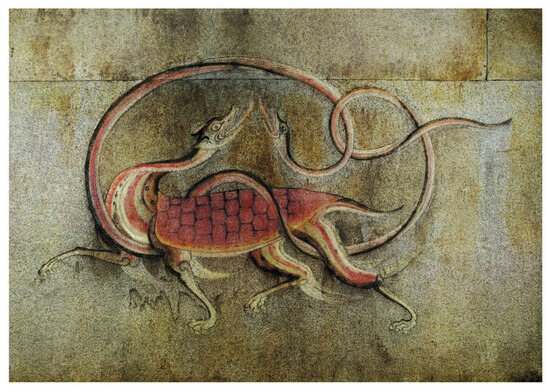

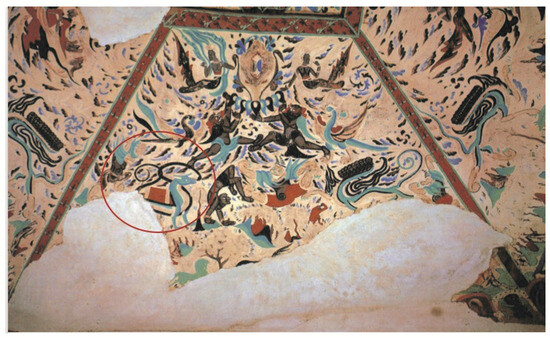

It is noteworthy that in the Four Directional Deities murals at both the Takamatsuzuka Tomb and the Kitora Tomb, the depiction of the Azure Dragon and White Tiger includes a distinctive feature: their tails curl around the hind legs and rise upward. This motif also appears in the White Tiger mural from the Tomb of Su Dingfang 蘇定方墓 (also known as the Tomb of Su Jun 蘇君墓) in Shaanxi Province, dated to 667 (Figure 8), as well as in White Tiger images found on the epitaphs at the Tomb of Feng Junheng 馮君衡墓 (AD 729) and other eighth-century Tang dynasty burial contexts. However, this particular representation is not found in the Four Directional Deities images in Goguryeo funerary sites. Scholars such as Akio Donohashi 百橋明穂 have speculated that the motif of the Azure Dragon and White Tiger with tails curling around their hind legs likely originated in China in the mid-seventh century and became prevalent throughout the eighth century (Donohashi 2013, p. 232). Conversely, Yoshinori Aboshi 網干善教 has conducted a meticulous iconographical analysis of the Black Tortoise and Vermilion Bird in both the Takamatsuzuka and the Kitora tombs. He observes a consistent depiction of the Black Tortoise across the two tombs and the Yakushi-ji pedestal: a snake coiled around the turtle, its head and tail interlocked. This type is likewise found in the depiction of the Black Tortoise image from the Complex of Goguryeo Tombs (Figure 9) (Aboshi 2006, pp. 129–33). Regarding the Vermilion Bird, Yoshinori Aboshi has noted that the representations in the Kitora Tomb and on the Yakushi-ji pedestal share a common typology, depicting the bird in the dynamic moment of takeoff or landing. Comparable renderings also appear on the epitaphs of the Tomb of Shi Sili 史思禮墓 (AD 744) (Figure 10) and the Tomb of Dou Lujian 豆盧建 (AD 744), both of which portray the Vermilion Bird in similar animated postures (See (Aboshi 2006, pp. 175–81).

Figure 8.

The White Tiger, Tomb of Su Jun, Xianyang, Shaanxi. Shaanxi Provincial Academy of Social Sciences, Institute of Archaeology (1963), “Excavation of the Tang Dynasty Tomb of Su Jun in Xianyang, Shaanxi,” Kaogu, no. 9, figure 7.

Figure 9.

The Black Tortoise, Goguryeo Kangso Tomb Complex, North Korea. Junichi Kikutake (1998), World Art Compendium, Eastern Section 1, vol. 10, Tokyo: Shōgakukan, p. 47.

Figure 10.

Epitaph of the Tomb of Shi Sili, Xi’an. Hongxiu Zhang (1992), Selected Decorative Patterns from Tang Dynasty Epitaphs, Xi’an: Shaanxi Fine Arts Publishing House, p. 56.

The orientation of the Four Directional Deities in the Kitora Tomb is notably distinctive. In the tomb’s mural program, the White Tiger faces north, the Azure Dragon faces south, and the Vermilion Bird faces west, forming a clockwise circular arrangement that is highly unusual. In contrast, Chinese tomb murals typically adhere to a south-facing principle, wherein both the Azure Dragon and White Tiger are oriented toward the south, and no circular configuration is observed. On the other hand, in the Takamatsuzuka Tomb, both the Azure Dragon and the White Tiger face the southern wall, an orientation that accords with conventional Chinese tomb mural practices and likewise corresponds to the directional alignment of the Four Directional Deities on the pedestal of the central image.

2.2. The Origin of Four Deities Imagery in Early Japan

Some studies have proposed that the Four Directional Deities on the pedestal of the central Buddha at Yakushi-ji differ from those in the Kitora and Takamatsuzuka Tombs due to the temple’s earlier date. However, according to previous scholarship, the Kitora Tomb is dated to around 700, while the Takamatsuzuka Tomb is estimated to have been constructed between approximately during AD 706–719.8 As speculated, the central Buddha at Yakushi-ji’s Kondō is generally dated to the Yōrō and Shinki eras (AD 718–726), placing it in close chronological proximity to the tombs. The time span between the three is thus relatively narrow, with all falling within the earliest known examples of the Four Directional Deities in Japan. Despite variations in their iconographic treatment, notable commonalities persist, suggesting a shared or closely related origin.

Some scholars have suggested that the concept and iconography of the Four Directional Deities were introduced to Japan after the governances of Emperor Tenmu and Empress Jitō potentially in connection with the migration of Baekje and Goguryeo groups following the Battle of Baekgang (AD 663), or through subsequent Japanese diplomatic missions to Tang China (Donohashi 2013, p. 242). The fall of Goguryeo may have facilitated the transmission of local funerary practices and mural traditions through these migrant communities. Nevertheless, by the first half of the seventh century, imagery of the Four Directional Deities had largely disappeared from Goguryeo artistic production. As discussed above, comparative studies of the Four Directional Deities from the Kitora Tomb, Takamatsuzuka Tomb, and Yakushi-ji’s Kondō pedestal, with examples from China and the Korean Peninsula, reveal that the motif of the Dragon and Tiger with tails curled around their hind legs appear in Chinese visual tradition slightly earlier or contemporaneously, but is absent in Goguryeo depictions. The motif of the Vermilion Bird in a flying or landing posture is predominantly observed in eighth-century Chinese visual culture, and the depiction of the Black Tortoise entwined with a snake, with its head and tail interlocking, is a type attested in Goguryeo iconographical traditions.

Accordingly, the early imagery of the Four Directional Deities in Japan likely derived from both the Chinese mainland and the Korean Peninsula, rather than from a single source. Following the Battle of Baekgang (AD 663), migrants from Baekje and Goguryeo are believed to have introduced the iconography of the Four Directional Deities into Japan. In the early eighth century, with the resumption of diplomatic missions from Tang China, additional examples of Four Deities imagery from the mainland were also transmitted. The differences observed among the representations of the Four Directional Deities at Yakushi-ji, the Kitora Tomb, and the Takamatsuzuka Tomb are thus more plausibly attributed to the utilization of different prototypes rather than to chronological disparities. From a chronological standpoint, the immediate appearance of the Four Directional Deities imagery in murals following its introduction suggests that its early adoption in Japan was closely intertwined with mortuary practices and funerary belief systems.

3. The Four Deities Imagery in China

Archaeological evidence suggests that the conceptual origins of the Four Directional Deities as astral symbols can be traced to Tomb No. 45 at the Xishuipo site 西水坡遺址 in Puyang 濮陽, Henan 河南, dating to the Yangshao 仰韶 culture period. In this site, shell arrangements form the figures of a dragon and a tiger have been interpreted as the earliest known manifestation of the Four Directional Deities motif (Puyang City Cultural Relics Management Committee 1988, pp. 1–6). The practice of adorning tombs with images of the Four Directional Deities formally emerged during the Han dynasty and subsequently developed into a recurring theme within the broader tradition of Chinese funerary art.

3.1. The Four Deities Imagery in Chinese Funerary Art

Images of the Four Directional Deities began appearing in tombs as early as the Western Han period. Notably, the ceiling of the main chamber in the Tomb of Liang Wang 梁王墓 in Yongcheng 永城, Henan (dating to the early Western Han), features depictions of a dragon, a Vermilion Bird, a White Tiger, and an aquatic creature. (Yan 2001, pp. 115–17). At this stage, the northern deity nonetheless had not yet assumed a fixed iconographic form; prior to the emergence of standardized Black Tortoise image, murals frequently depicted alternative figures such as snakes or fisherwomen in its place. By the Eastern Han period, especially in its middle to late stages, the imagery of the Four Directional Deities underwent considerable development and reached a stage of iconographic maturity, gradually giving rise to a relatively standardized visual schema that would persist in subsequent Chinese funerary art. During the Three Kingdoms and Jin periods, the imagery of the Four Directional Deities became a frequent motif in tomb mural programs. Significant instances include the murals from the Eastern Jin Dynasty Tomb of Yuantaizi 袁台子東晉壁畫墓 in Chaoyang 朝陽, Liaoning 遼寧 (Cultural Relics Team of the Liaoning Provincial Museum 1984, pp. 29–45) and the Tomb of Huo Chengsi 霍承嗣墓 in Zhaotong 昭通, Yunnan 雲南 (Yunnan Provincial Cultural Relics Work Team 1963, pp. 1–6). This iconographic tradition experienced a marked resurgence from the Northern Dynasties through the Sui Dynasty, with the Four Directional Deities appearing in significant numbers across various funerary contexts. Examples include the tomb of Yuan Yi 元乂墓 in Luoyang 洛陽, Henan, from the second year of the Xiaochang era (AD 526) of the Northern Wei (Luoyang Museum 1974, pp. 53–55), the tomb of Princess Ru Ru 茹茹公主墓in Cixian 磁縣, Hebei 河北, from the eighth year of the Wuding era (AD 550) of the Eastern Wei (Cixian Cultural Center 1984, pp. 10–15), the Tomb of Lou Rui 東安王婁睿墓 in Taiyuan 太原, from the first year of the Wuping era (AD 570) of the Northern Qi (Shanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology 2006, pp. 78–79), the tomb of Cui Fen 崔芬墓 in Linqu 臨朐, Shandong 山東, from the second year of the Tianbao era (AD 551) of the Northern Qi (Shandong Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 2002, pp. 4–20), and the tomb of Xu Minxing 徐敏行 in Jiaxiang 嘉祥, Shandong, from the fourth year of the Kaihuang era (AD 584) of the Northern Qi (Shandong Museum 1981, pp. 28–33). In addition to mural-adorned tombs, the Four Directional Deities also prevailed as decorative elements on the exterior surfaces of stone sarcophagi and coffins in the meantime.

During the early Tang period, representations of the Four Directional Deities varied considerably across different regions, reflecting both inherited traditions and localized practices. In the Guanzhong 關中 region, the convention of depicting the Four Deities in tomb corridors which carried over from the Northern Dynasties was largely preserved. In this context, the Azure Dragon and White Tiger were typically painted on the east and west walls of the corridor, while images of the Four Deities ceased to appear within the main burial chamber. In the Taiyuan region, a different Northern Dynasties tradition was maintained: the Four Deities were painted on the ceiling of the burial chamber, but their depictions were absent from the tomb corridor walls. By contrast, mural tombs in the southern regions exhibited divergent practices. In the Tomb of Ran Rencai 冉仁才墓, for instance, the Four Directional Deities were painted along the walls of the passageway (Sichuan Museum 1980, pp. 503–4), while in the Tomb of Zhang Jiuling 張九齡墓, they appeared within the main burial chamber itself (Guangdong Provincial Cultural Relics Management Committee 1961, pp. 45–51).

The function of the Four Directional Deities in tomb mural programs has also been a subject of scholarly debate. Zhang Hongxiu 張鴻修 contends that their primary role is to mark the cardinal directions or to serve as apotropaic figures, warding off evil spirits and safeguarding the tomb (Zhang 2001, p. 367). In contrast, Li Xingming 李星明 argues for a more layered interpretation, asserting that the Four Directional Deities in funerary art embody multiple symbolic functions, including the simulation of a cosmic model, the salvation of the soul, alignment with the cosmic order of heaven and earth, communication with divine forces, exorcism, guidance in the ascent to immortality, fengshui considerations, and the protection of descendants (Li 2001, p. 321; Li 2003, p. 98).

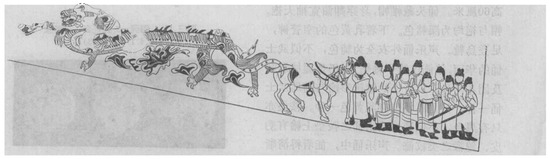

In addition to tomb murals, the Four Directional Deities images are also frequently found on epitaphs. Such depictions first appeared on select epitaphs during the Northern Wei period and became increasingly widespread throughout the Sui and Tang dynasties. According to Li’s research, over half of all epitaphs bearing engraved ornamentation include representations of the Four Directional Deities and the Chinese Zodiac signs. This prevalence suggests that, when integrated with epitaphs, these images conveyed widely recognized symbolic meanings associated with funerary beliefs and practices (Li 2005, p. 193). On most epitaph covers, the Four Directional Deities are arranged in a clockwise direction, with the Azure Dragon, Vermilion Bird, and Black Tortoise depicted in dynamic poses, either in motion or flight, while the White Tiger typically faces counterclockwise. However, notable exceptions exist in which both the Azure Dragon and White Tiger face toward the Vermilion Bird, as exemplified by epitaphs from the Tombs of Dugu Kaiyuan 獨孤開遠墓 (AD 642), Lady Tan 譚夫人墓 (AD 646), Feng Junheng 馮均衡墓, Zhang Quyi 張去逸墓, and Liu Yu 柳昱墓 (AD 805). Li has suggested that this arrangement conveys two symbolic meanings: firstly, it represents the cyclical nature of time, space, and the seasonal cycle; secondly, it evokes the “ascending formation” described in Han dynasty texts, wherein the Vermilion Bird leads forward, the Azure Dragon and White Tiger flank its sides, and the Black Tortoise occupies a protective position at the rear, thus creating a celestial formation symbolizing ascent or transcendence (Li 2005, p. 199).

3.2. The Four Directional Deities in Chinese Buddhist Art

Depictions of the Four Directional Deities are exceedingly rare in Chinese Buddhist art. Known examples are limited to a small number of murals in the Mogao Caves 莫高窟at Dunhuang 敦煌 and select relic containers dating from the Sui dynasty and subsequent periods. A relatively early example of the Four Directional Deities in Chinese Buddhist art is found in Cave 249 of the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang, dated to the Western Wei period. The ceiling of this cave is adorned with images of the Four Directional Deities. While scholarly debate continues regarding the precise positioning of each deity,9 it is clear that the Black Tortoise (Figure 11) is located on the eastern side, which is an arrangement that deviates from the conventional directional schema. This misalignment suggests that the Four Directional Deities in Cave 249 were not intended to represent the cardinal directions in the traditional sense. Rather, it is plausible that these figures were employed symbolically to evoke the Taoist celestial realm, reflecting a syncretic vision in which Taoist and Buddhist cosmologies coexist within the sacred space. Another example appears in Cave 442, a Northern Zhou period cave at Mogao. Beneath the west-facing central pillar, the Black Tortoise is depicted on the northern wall of the niche. The absence of the remaining three deities however indicates that this figure was not conceived as part of a complete Four Directional Deities ensemble.

Figure 11.

The Black Tortoise, East slop of Cave 249, Dunhuang. Ruiwen Shen (2023), “On the Muraled-Ceiling Images of Mogao Caves 249 and 285, Palace Museum Journal, no. 6, figure 3.

Additionally, starting from the Sui dynasty, images of the Four Directional Deities also present on relic containers. A representative example from this period is the stone reliquary discovered beneath the Shende Temple 神德寺 Pagoda in Yaoxian 耀縣, Shaanxi 陝西, whose slanted lid is carved with the Four Directional Deities. Similarly, within in the tomb complex at Longquan Temple 龍泉寺 in Taiyuan, Shanxi 山西, dating to the Wu Zhou 武周 period, a sarcophagus was unearthed bearing depictions of the Four Deities on all four sides, which is a design fully consistent with that found on conventional funerary artifacts. Ran Wanli 冉萬里 has then argued that the inclusion of the Four Directional Deities on such relic containers serves as a significant symbol of the integration of Buddhism with indigenous Chinese cultural traditions and represents a typical marker of the sinicization of Buddhist relic interment practices (Ran 2013, pp. 154–57). Given that relics are the cremated remains of the Buddha or eminent monks, the reliquary itself may be regarded as a specialized funerary artifact. Thus, the appearance of the Four Directional Deities on reliquaries during the Sui and Tang periods may be interpreted as closely aligned with broader funerary beliefs.

4. Grotesque Figures

Regarding the grotesque figures carved on the waist section of the pedestal of the central Buddha in the Kondō at Yakushi-ji, no direct counterparts have been identified in Chinese Buddhist art from the Tang dynasty or earlier. The unique iconography of these figures has prompted considerable discussion concerning their identity and symbolic significance.10

4.1. Discussion in Previous Scholarship

Tsutomu Kameda 亀田孜 has proposed that the twelve grotesque figures within the bell-shaped niches share visual and thematic resemblance to the Eight Legions 天龍八部 and the subdued spirits beneath the Four Heavenly Kings found in the aureole of the Eleven-Headed Kannon statue at the Nigatsudō 二月堂 of Tōdai-ji 東大寺, dating to the Nara period. He speculates that these figures likely represent the Twelve Yakṣa Generals 十二藥叉大將, the protective attendants of the Yakushi Nyorai. Moreover, Kameda argues that the iconographic divergence between these figures and later standardized representations of the Twelve Yakṣa Generals may be attributed to the direct appropriation of early imagery introduced from Tang China into the Japanese context (Kameda 1948, p. 13). Shoken Kojima 小島章見, by examining classical texts and related literary sources, offers a different interpretation. He identifies the two grotesque figures located outside the niches on the southern and northern sides as representations of the Earth Goddess Dṛḍha 堅牢地神 in Buddhism cosmology, who are believed to support Mount Meru. He further contends that the remaining twelve figures within the panel represent the original iconographic forms of the Twelve Divine Kings 十二神王 of Yakushi Nyorai (Kojima 1948, p. 17).

Other scholarly hypotheses have emphasized the influence of cultures beyond East Asia in interpreting the grotesque. Koichi Machida 町田甲一 argues that the two grotesque figures at the central positions of the southern and northern sides resemble dwarf figures holding small stupas or nude figures supporting pillars in Chinese Buddhist art. He traces their iconographic origins to Indian prototypes, particularly from the Bharhut and Sanchi Stupas, where yakṣa figures are depicted bearing stupas or thrones, suggesting that the remaining twelve figures were likely intended as ornamental motifs rather than specific iconographic beings (Machida 1988, p. 118). Takeshi Asanuma 淺湫毅 proposes that the appearance of the grotesque figures, particularly their curly hair, derives from representations of “Kunlun slaves” 崑崙奴 and Negroid individuals who were brought from Southeast Asia and encountered by the Chinese. In Tang China, Southeast Asian countries were associated with the realm of rākṣasas 羅刹國, and Kunlun slaves were often portrayed as cannibalistic demons. Thus, Asanuma interprets the grotesque figures as embodiments of malevolent spirits or rākṣasas, serving as fierce protectors of the Dharma (Asanuma 1993, p. 70). Ryūsaku Nagaoka 長岡龍作 notes that the two centrally positioned figures resemble those found in Chinese cave temples and image stelae, where such figures commonly support columns, jewels, or relic containers. As for the twelve figures within the niches, he posits that they embody a dual nature, representing both demonic spirits and inhabitants of the Southeast Asian, further reflecting a fusion of protective and foreign elements within the sculptural program (Nagaoka 2003, pp. 139–49).

Masaaki Matsuura proposes that the two grotesque figures positioned at the southern and northern centers that depicted in the nude carry a strong resemblance to figures found in Gandhāran and Mathuran sculptures. He interprets these two figures as symbolic deities tasked with supporting the Buddhist Pure Land. Matsuura further draws upon the Suvarṇaprabhāsottama Sūtra, specifically the section concerning the Earth Goddess Dṛḍhas, to argue that these figures represent the Earth Goddess Dṛḍhas as described in the sutra. As for the remaining twelve grotesque figures within the niches, he identifies them as yakṣas positioned around Mount Meru (Matsuura 2004, pp. 78–79).

Arisu Tobana also interprets these grotesque figures in the light of the Suvarṇaprabhāsottama Sūtra. He identifies the two central grotesque figures as representations of the Vajra Earth Gods described in the sutra’s section on those deities, the beings who are said to “conceal themselves beneath the pedestal and place their feet on the top of their bodies.” The twelve grotesque figures within the niches, according to Tobana, correspond to guardians of the Suvarṇaprabhāsottama Sūtra and are derived from the chapter of the yakṣa Saṃjñaya, which describes beings who “accompany the twenty-eight generals, travel there, and protect those monks” (Tobana 2009, pp. 67–68).

4.2. Discussion on the Identity of the Grotesque Figures

Based on previous research, although no definitive consensus has been reached, the two grotesque figures positioned at the southern and northern centers of the pedestal exhibit notable similarities in both form and function to yakṣa figures in Chinese Buddhist art, which are often depicted in supportive or bearing postures (Figure 12). We concur with this interpretation; however, whether these figures specifically represent the Dṛḍhas remains open to further investigation. In addition, we have observed that these two grotesque figures closely resemble the demonic figures depicted on the lower walls of the central pillar in Cave 9 (Northern Cave) of the Beixiangtang Mountain Caves 北響堂山石窟 in Hebei. Although the figures in the Kondō lack wings, their kneeling postures are nearly identical to those of the demons at Beixiangtang (Figure 13). This visual correspondence suggests that the two central grotesque figures in the Kondō may also embody a demonic character, layering complexity to their potential symbolic meaning.

Figure 12.

Statue of supporting yakṣa at the bottom of the central pillar’s south side, Cave 3, Gongxian Caves 鞏縣石窟. Editorial Committee for the Complete Collection of Chinese Cave Sculpture (2001), Complete Collection of Chinese Cave Sculpture: Six Northern Provinces, Chongqing: Chongqing Publishing House, p. 15.

Figure 13.

Demonic figure, bottom of the east wall, Cave 9, North side of Xiangtangshan Caves 響堂山石窟. Photography by Haruo Yagi.

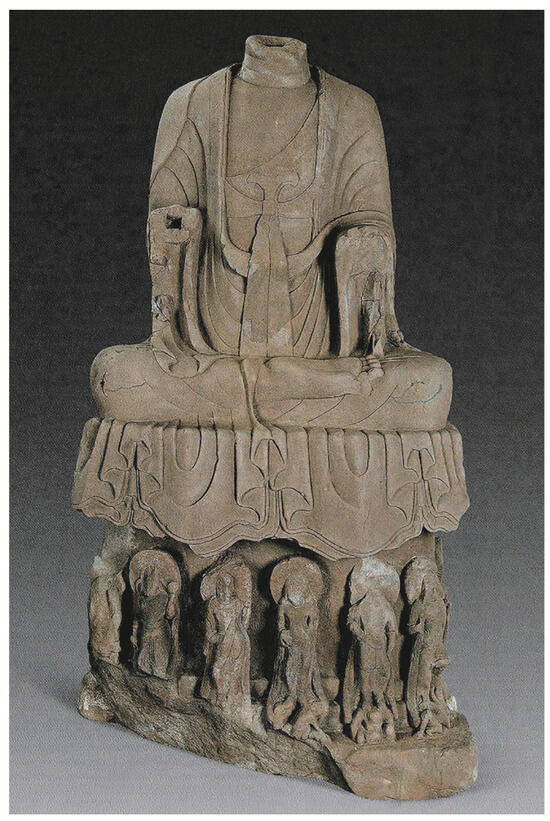

The remaining twelve grotesque figures within the niches are commonly interpreted in prior scholarship as the representations of “Twelve Divine Kings” or “Twelve Yakṣa Generals” described in the Yakushi Nyorai Sūtra (Bhaiṣajyaguru Sūtra). Although no exact counterparts survive in Chinese sculptures, the pairing of Yakushi Nyorai with the Twelve Divine Kings likely dates back to the Southern Dynasties. At the site of Wanfo-si 萬佛寺 in Chengdu 成都, Sichuan 四川, a seated Buddha image (No. 21838, Sichuan Museum) was discovered, surrounded by twelve standing guardian deities around its throne (Figure 14). Changqing 常青compared these figures with the deity images on the pedestal (No. 21829, Sichuan Museum) also excavated at the Wanfosi site and identified the ensemble as a representation of Yakushi Nyorai and the Twelve Divine Kings based on the Fo Shuo Guan Ding Jing 佛説灌頂經 (Consecration Sūtra) translated by the Eastern Jin monk Śrīmitra of Kuchea 帛尸梨蜜多羅 (Chang 2021, pp. 4–23). While these two Sichuanese examples differ markedly in appearance from the grotesque figures on the Kondō pedestal at Yakushi-ji, they may share a comparable iconographic function.

Figure 14.

Seated Buddha, Wanfo-si, Chengdu. Sichuan Museum et al. (2013), Buddhist Statues of the Southern Dynasties Excavated in Sichuan, Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, figure 17-1.

As noted by Asanuma and others, the appearance of these twelve grotesque figures within the bell-shaped niches closely resembles that of the yakṣa figures trampled beneath the feet of the Heavenly Kings. For instance, the figures beneath the Heavenly Kings on the left and right walls of the Fengxian Temple 奉先寺 at the Longmen Grottoes 龍門石窟 (Figure 15), as well as the figure underfoot there, exhibit similarly exaggerated features, such as glaring eyes, flared nostrils, and bared teeth. Given these visual parallels, interpreting the twelve grotesque figures as the Twelve Yakṣa Generals is a plausible reading. Although various texts render their titles differently (“Twelve Divine Kings,” “Twelve Yakṣa Generals,” or “Twelve Yakṣa Kings”), their essential nature remains that of yakṣa. Thus, the adoption of iconographic conventions associated with Tang dynasty yakṣa imagery appears entirely reasonable.

Figure 15.

Yakṣas beneath the feet of the Guardian Kings on both side walls, Fengxian Temple, Longmen Grottoes, Henan. Photograph by the author.

5. The Cremation of Emperor Jitō

Before turning to the purpose behind the creation of the central Yakushi Nyorai in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji, it is necessary to note that Empress Jitō was cremated after her death. This detail offers critical insight into the intended meaning of the statue’s pedestal and the broader motivations behind the commissioning of this Buddha image.

In the late seventh century, under the growing influence of Buddhist concepts and the reforms initiated during the Taika era, cremation was introduced to Japan and gradually became the prevailing funerary practice. According to historical records, the first recorded instance of cremation in Japan was that of the Buddhist monk Dōshō 道昭, founder of Gangō Temple 元興寺. In the fourth year of Emperor Monmu’s reign (AD 700), Dōshō passed away at the age of seventy-two, and his disciples, in accordance with his testaments, carried out his cremation at Ōbara Temple 粟原寺. Noted in the Shoku Nihongi, this event marked the beginning of cremation in Japan.11 Further, Emperor Jitō was the first sovereign to be cremated. She passed away in the second year of Daibō (AD 702) and was cremated in the following year. Her remains were later interred alongside Emperor Tenmu in the same imperial tomb.12

6. Examination of the Pedestal’s Iconographic Significance and the Purpose Behind the Central Buddha Creation in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji

The central Yakushi Buddha statue enshrined in the Yakushi-ji was originally commissioned in AD 680 by Emperor Tenmu as a votive offering for the recovery of his ailing consort, who would later ascend the throne as Empress Jitō. However, Empress Jitō passed away in AD 702 and was cremated in the next year. Following the relocation of the capital to Heijō-kyō in AD 710, the triad statue was recast and enshrined in the newly constructed Yakushi-ji. With Empress Jitō’s death, the Buddha image, which originally intended as a prayer for healing, likely assumed a transformed ritual function. As the first Japanese sovereign to undergo cremation, her death marked a moment of profound ritual and symbolic transition. The introduction of this funerary innovation brought with it a sense of spiritual and ceremonial uncertainty, potentially reconfiguring the statue’s significance within a funerary and commemorative framework.

The Four Directional Deities are traditional guardians of the four cardinal directions rooted in the cosmology of China’s wuxing 五行 philosophy and have traditionally been interpreted as protective figures marking the cardinal directions. However, as noted at the beginning of this article, there are no known examples in either Japan or China where the Four Directional Deities are arranged directly on the pedestal of a Buddha statue. In Chinese Buddhist contexts, the integration of the Four Directional Deities into Buddhist visual program is rare and generally limited to a small number of Northern Dynasties murals at the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang and to reliquary from the Sui dynasty onward. Among the Dunhuang caves, only the Black Tortoise is depicted, and thus these images should not be regarded as complete displays of the Four Directional Deities, nor as symbolic markers of the four directions. By contrast, reliquaries from the Sui and Tang periods more frequently feature full sets of the Four Directional Deities, often with relatively complete iconography. Since relics are the cremated remains of the Buddha or eminent monks, the containers serve as specialized funerary objects. In this context, the inclusion of the Four Directional Deities may be more closely associated with funerary and protective symbolism than with cosmological orientation alone.

When examining early representations of the Four Directional Deities in Japan, whether in the Kitora Tomb, Takamatsuzuka Tomb, or the pedestal of the central Yakushi Buddha in the Kondō, it becomes evident that these examples are closely clustered in date, all dating to the early eighth century. Yakushi-ji was founded by imperial decree, and the occupants of the tombs were likely individuals of high social rank. It is thus reasonable to infer that by this time, Japanese aristocrats were already familiar with the iconography of the Four Directional Deities as transmitted from China and the Korean Peninsula, and that they understood its symbolic significance. The early introduction of the Four Directional Deities’ concept and visual form into Japan likely occurred in conjunction with the dissemination of funerary art and burial practices, reinforcing their association with cosmological order, protection, and posthumous transcendence.

Therefore, it is clear that the Four Directional Deities depicted on the pedestal of the central Yakushi Buddha in the Yakushi-ji, while traditionally interpreted as guardians of the four cardinal directions, also embody the additional function of guiding the soul to the heavens and protecting the deceased, paralleling their role in ancient Chinese funerary contexts. The grotesque figures positioned at the southern and northern centers of the pedestal, rendered in a supportive posture and exhibiting beast-like characteristics, may likewise contribute to this protective schema. In conjunction with the Four Directional Deities, these figures collectively serve a funerary function, safeguarding the deceased within the ritual and cosmological framework of the monument.

Moreover, Yakushi Nyorai himself is closely associated with the concept of the Pure Land of Amitābha. Some scholars have mentioned that the description of Yakushi Nyorai’s Pure Land in Bhaiṣajyaguru sūtras invites comparison with the Amitābha Pure Land, as the text explicitly states that the realm of Bhaiṣajyaguru is “not different” from the Pure Land of Amitābha.16 The texts further affirm that devotees of Yakushi Nyorai, should they wish to be reborn in the Pure Land of Amitābha, will be welcomed at the moment of death by eight Bodhisattvas.17 It hence may be inferred that devotion to Yakushi Nyorai in the Tang dynasty included a salvific dimension, particularly one oriented toward rebirth. This association underscores the possibility that Yakushi Nyorai was not only venerated as a healing deity but also as a figure capable of mediating rebirth in a paradisiacal realm (Bai 2010, pp. 149–50).

From this perspective, the combination of Yakushi Nyorai enshrined in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji and the Twelve Divine Generals depicted on the pedestal may be interpreted as a symbolic representation of the Lapis Lazuli Pure Land. Meanwhile, the Four Directional Deities can be understood as forming a celestial configuration that signifies ascension to immortality or rebirth in the Pure Land. Taken together, this sculptural program may have expressed a votive prayer for the deceased Empress Jitō, demonstrating the aspiration for her rebirth in the Pure Land under the salvific protection of Yakushi Nyorai.

A comparable example of a shift in the potential intention of a Buddhist statue can be found the Shakyamuni Triad enshrined in the Kondō of Hōryū-ji Temple. The inscription on this statue offers a detailed account of its creation and contextual significance. In 621, Lady Tachibana 橘夫人, the mother of Prince Shōtoku, passed away. In the following year, on the twenty-second day of the first month, Prince Shōtoku 聖徳太子 fell gravely ill and became unable to eat, while his consort was also ill. In response, Prince Shōtoku, his consort, and several court ministers vowed to cast a statue of Shakyamuni modeled after the prince, with the hope of invoking the Buddha’s healing power. Should the illness prove fatal, the statue would serve instead as a vehicle for prayers for his rebirth in the Pure Land. On the twenty-first day of the second month, the consort passed away, and the prince himself died the following day. In 622, the statue of Shakyamuni was completed by the sculptor Tori Busshi. The statue’s constructional purpose thus shifted from one of healing to a posthumous function: to commemorate Prince Shōtoku and his consort and to receive the ritual offerings on their behalf.18 Hence, the precedent of the Shakyamuni statue in the Kondō of Hōryū-ji supports the hypothesis that the intended function of the central Yakushi Buddha in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji analogously changed following Empress Jitō’s death.

7. Conclusions

The iconographic scheme of the pedestal beneath the central Buddha in the Kondō at Yakushi-ji is highly distinctive within the context of East Asian Buddhist art. It may be regarded as a creative synthesis of Buddhist ritual iconography and funerary visual language within the East Asian cultural sphere, offering valuable insight into the transregional transmission and adaptation of Buddhist visual forms.

The intended purpose behind the construction of the central image of the Medicine Buddha (Bhaiṣajyaguru) in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji underwent a significant transformation: from Emperor Tenmu’s prayer for the recovery of his ailing empress to a posthumous offering following Empress Jitō’s death. This shift in intention is visually articulated in the iconographic program of the central Buddha’s pedestal. The twelve grotesque figures in the waist section are interpreted as the Twelve Divine Generals of Bhaiṣajyaguru, collectively symbolizing the Pure Land of Bhaiṣajyaguru in conjunction with the central Buddha. The two kneeling figures situated beneath the pillars on the north and south sides, which are identified as both yakṣas and mythical beasts, fulfill a dual role: they support the Buddhist realm architecturally while also serving a protective function for the soul of the deceased. At the lowest tier, the Four Directional Deities not only delineate the cardinal directions but, as in Chinese funerary tradition, embody a ritual function by guiding the soul’s ascent and safeguarding the dead. Taken together, the imagery of the pedestal may be interpreted as a visualized prayer for Empress Jitō’s rebirth and ascension in the Western Pure Land.

Regarded as a coherent program, the pedestal’s imagery constitutes a carefully orchestrated visual prayer on behalf of Empress Jitō after death. It signals a deliberate reorientation of the statue’s function: from an image of healing intercession to a votive work directed toward securing her rebirth in the Western Pure Land. In both its conceptual scope and iconographic specificity, the pedestal exemplifies how Buddhist art could be recalibrated to meet changing ritual needs within a specific historical and imperial context.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Project of the National Social Science Founda-tion of China (Grant No. 23&ZD278).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| FGJ | Foshuo guanding jing 佛説灌頂經 (Consecration Sūtra) |

| NS | Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 (The Chronicles of Japan) |

| SN | Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀 |

| SE | Shoseki Engishū 諸寺縁起集 (Collected Temple Origin Stories) |

| JHTI | Japanese Historical Text Initiative |

Notes

| 1 | “12th day. The Empress-consort was unwell. (The Emperor,) having made a vow on her behalf, began the erection of the Temple of Yakushiji, and made one hundred persons enter religion as priests. In consequence of this she recovered her health. (癸未。皇后。體不豫。則爲皇后誓願之。初興薬師寺。仍度一百僧。由是得安平。(NS, 720, book 29, para. 3, 1760; JHTI ed.). |

| 2 | “Winter 10th month 4th day. The construction of the Yakushiji being nearly completed, an Imperial Command was given to the priests, to occupy their quarters in this temple. (冬十月庚寅。以薬師寺構作畧了。詔衆僧令住其寺。)” (SN, 797, book 2, para. 5, 17; JHTI ed.). |

| 3 | Shoseki Engishū (Collected Temple Origin Stories, 諸寺縁起集), Daigo-ji manuscript, includes the Yakushiji Engi 薬師寺縁起, which records: “In the second year of Yōrō (718), Year of the Wu-Wu, the Retired Emperor relocated the monastic complex (garan) to Heijō-kyō. (太上天皇養老二年午戊移伽藍於平城京。)” (SE, Muromachi period.). |

| 4 | Hayashi refers to the late Gaozong period through the Wu Zhou era. |

| 5 | “The first year of Taiho, Spring first month, the first day being Otsugai. (Kinoto-i). The Emperor proceeded to the Daigokuden and received the Court. At this ceremony the crow’s shape banner was placed at the front gate. At the left the sun-banner, the banners of the Blue Dragon and the Red Sparrow; at the right the moon-banner, the banners of the Black Turtle and the White Tiger. (大寳元年春正月乙亥朔。天皇御大極殿受朝。其儀於正門樹烏形幢。左日像青龍朱雀幡。右月像玄武白虎幡。)” (SN, 797, book 2, para. 5, 17; JHTI ed.). |

| 6 | “Tenth day. A red bird perched on the Southern Gate. (癸未。朱雀在南門。)” (NS, 720, book 29, para. 8, 1757; JHTI ed.). |

| 7 | The depiction of clothing worn by the male and female figures in the mural of the Takamatsuzuka Tomb has served as a critical indicator for determining the date of its production. The terminus post quem is established by the left-overlapping robes (sajin左衽) worn by both male and female figures. In AD 719, a governmental decree mandated that all subjects wear right-overlapping garments (ujin 右衽); thus, the mural must have been executed prior to this date. The terminus ante quem is suggested by the broad sleeves and collars worn by the figures, which contrast with sartorial regulations issued in AD 708, stipulating that sleeve openings be no wider than one shaku and no narrower than eight cun (approximately 23.7–29.5 cm in Tang measurement), and that collars be long and narrow. By AD 712, noncompliance with this standard was regarded as a serious breach of decorum. In addition, the male figures are depicted wearing white trousers (shirobakama 白袴), a style formally instituted by decree in AD 706, which replaced earlier leg coverings (habakimo 脛裳). Based on these clothing-related details, prior scholarship has generally concluded that the mural of the Takamatsuzuka Tomb was produced between AD 706 and AD 719. By contrast, the mural program of the Kitora Tomb displays strong visual and compositional affinities with that of Takamatsuzuka, though certain stylistic features suggest an earlier date. Notably, the depiction of the Vermilion Bird in the Kitora Tomb reveals the traditional style, while the rendering of the zodiac animals Tiger (yin 寅) and Horse (wu 午) lacks the technical refinement characteristic of the Takamatsuzuka murals. As such, the Kitora Tomb is generally considered to predate Takamatsuzuka slightly, and is typically dated to around the year AD 700. See (Asuka Historical Museum 2006, pp. 21–22). |

| 8 | See note 7 above. |

| 9 | Scholars hold differing views regarding the positioning of the Four Directional Deities on the ceiling of Mogao Cave 249. He Shizhe notes only that all four slopes of the ceiling are adorned with images of the Four Deities, without specifying their precise locations. Saitō Rieko, however, asserts that both the Vermilion Bird and the Black Tortoise appear on the east slope. In contrast, Shen Ruiwen offers a comprehensive allocation of each deity to a cardinal orientation: the Vermilion Bird on the west slope, the Black Tortoise on the east, the Azure Dragon on the south, and the White Tiger on the north. See (Duan 2007, p. 322; Saitō 2001, pp. 155–56; and Shen 2023, p. 4). |

| 10 | Prior research on the grotesque figures carved around the constricted waist of the pedestal beneath the central image in Yakushi-ji’s Kondō has been partially surveyed by Shimotsuke Suzuko. For details, see (Shimotsuke 2000, pp. 120–24). |

| 11 | The records write, “Third month tenth day. The priest Dōshō died. The Emperor was greatly grieved and sent a messenger to convey his condolences…At the time he was three score and twelve. His disciples, in conformity with instructions he left behind, incinerated him in Ōbara. This is the origin of cremation in the Realm. (三月己未。道照和尚物化。天皇甚悼惜之。遣使弔賻之……時年七十有二。弟子等奉遺教。火葬於粟原。天下火葬従此而始也。)” (SN, 797, book 1, para. 8–10, 12–13; JHTI ed.). |

| 12 | “22nd day. The retired Empress died. She left orders that it was not necessary to wear mourning and to weep. Civil and military officers in and out of the capital were to perform their duties as usual the burial to be simple. (甲寅。太上天皇崩。遺詔。勿素服挙哀。内外文武官釐務如常。喪葬之事務従儉約。)” (SN, 797, book 2, para. 2, 32; JHTI ed.). “Seventeenth day. Takima no Mabito Chitoko, ju-shi-i-jo, at the head of all princes and officials, read an address in praise of the decreased Empress. The posthumous name of Oyamatoneko Ama no Hironu Hime no Mikoto was bestowed upon her. This day she was cremated on the Asuka- hill. (癸酉。従四位上當麻眞人智徳。率諸王諸臣。奉誄太上天皇。謚曰大倭根子天之廣野日女尊。是日。火葬於飛鳥岡。)” (SN, 797, book 3, para. 9, 37; JHTI ed.). |

| 13 | “15th day. The Emperor passed away. He left behind an Imperial Rescript: Lamenting for three days, mourning dress one month. (辛巳。天皇崩。遺詔。挙哀三日。凶服一月。)” (SN, 797, book 3, para. 10, 54; JHTI ed.). “11th month, 12th day. Taima no Mabito Chitoko, ju shi i jo, at the head of the people appointed to read valedictory addresses, read an address in praise of the deceased Emperor and gave him his posthumous name: Yamatoneko Toyo Ochi no Tenno. The same day he was cremated, on the Asuka hill. (十一月丙午。従四位上當麻眞人智徳率誄人奉誄。謚曰倭根子豊祖父天皇。即日火葬於飛鳥岡。)” (SN, 797, book 3, para. 2, 55; JHTI ed.). “On the twentieth day he was buried in the Mausoleum at Ako, Hinokuma. (甲寅。奉葬於桧隈安古山陵。)” (SN, 797, book 3, para. 2, 55; JHTI ed.). |

| 14 | “丁亥。太上天皇召入右大臣從二位長屋王。參議從三位藤原朝臣房前。詔曰。朕聞。萬物之生。靡不有死。此則天地之理。奚可哀悲。厚葬破業。重服傷生。朕甚不取焉。朕崩之後。宜於大和國添上郡蔵寶山雍良岑造灶火葬。莫改他處。謚號稱其國其郡朝庭馭宇天皇。流傳後世。又皇帝攝斷萬機。一同平日。王侯・卿相及文武百官。不得輙離職掌。追從喪車。各守本司視事如恆。其近侍官並五衛府。務加嚴警。周衛伺候。以備不虞。” (SN vol.8, 797, p. 33; National Diet Library Digital Collections ed.). |

| 15 | “丁卯。勅、天下悉素服。是日、火葬太上天皇於佐保山陵。” (SN vol.8, 797, p. 12; National Diet Library Digital Collections ed.). |

| 16 | “此藥師琉璃光佛本願功德如是。我今為汝略説其國莊嚴之事。此藥師琉璃光如來國土清淨,無五濁、無愛欲、無意垢,以白銀琉璃為地,宮殿樓閣悉用七寶,亦如西方無量壽國無有異也。有二菩薩:一名日曜、二名月淨,是二菩薩次補佛處。諸善男子及善女人,亦當願生彼國土也。” (FGJ, T1331, book 12, 533a14–20; Taishō 21, 1924). |

| 17 | Ibid., p. 533c1-8. “願欲往生西方阿彌陀佛國者,憶念晝夜,若一日二日三日四日五日六日七日,或復中悔聞我說是《藥師琉璃光佛本願功德》,盡其壽命,欲終之日,有八菩薩……皆當飛往,迎其精神,不經八難,生蓮華中,自然音樂而相娯樂。”. |

| 18 | “In the Hōkō gan sanjūichi year, the year Shin-shi, in the twelfth month, the empress dowager [believed to refer to Prince Shōtoku’s mother] passed away. On the twenty-second day of the first lunar month in the following year, Kamitsumiya Hōō [Prince Shōtoku] was confined to bed due to illness. His consort fell sick as well due to exhaustion. Various people, including his consort, princes and ministers vowed to make a statue of Shaka Buddha the size of Prince Shōtoku. By means of this vow, may the health of the prince be restored and his life extended, may he live peacefully in the world. Should it be his karmic destiny to depart the world, may he ascend to the Pure Land and swiftly attain the ultimate wisdom. On the twenty-first day of the second lunar month, the consort passed away and on the following day Prince Shōtoku died. In the third month of the year Ki-bi, the statue of the Shaka Buddha and the attendant bodhisattvas were completed. In humble benevolence, this congregation of lay believers will live the present life in peace and may they continue to serve the three lords after the end of this life to perpetuate the glory of the Three Treasures of Buddhism. May all beings of the six paths be free from suffering and together obtain transcendent wisdom. Shiba Kuratsukuri Obito Tori-busshi (the sculptor Tori of the Shiba family, Chief of the Saddlers’ Guild) made the statue. (法興元卅一年歲次辛巳十二月、鬼前太后崩。明年正月廿二日、上宮法王枕病弗悆乾食。王后仍以勞疾、並著於床。時王后王子等及與諸臣、深懷愁毒、共相發願。仰依三寶、當造釋像尺寸王身。蒙此願力、轉病延壽、安住世間。若是定業、以背世者、往登淨土、早升妙果。二月廿一日癸酉、王后即世。翌日、法皇登遐。癸未年三月中、如願敬造釋迦尊像並俠侍及莊嚴具竟。乘斯微福、信道知識、現在安穩、出生入死、隨奉三主、紹隆三寶、遂共彼岸、普遍六道、法界含識、得脫苦緣、同趣菩提。使司馬鞍首止利佛師造。)” See (Wu 2024, p. 127). |

References

Primary Source

Foshuo guanding jing 佛説灌頂經 (Consecration Sūtra). 1924. 大正新修大藏経 (Taishō Tripiṭaka). Tokyo: Taishō Issaikyō Kankōkai.Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 (The Chronicles of Japan). Translated by W. G. Aston. In Japanese Historical Text Initiative. Berkeley: Center for Japanese Studies, University of California, n.d. Available online: https://jhti.studentorg.berkeley.edu/Nihon%20shoki.html (accessed on 4 August 2025).Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀. Translated by J. B. Snellen. In Japanese Historical Text Initiative. Berkeley: Center for Japanese Studies, University of California, n.d. Available online: https://jhti.studentorg.berkeley.edu/Nihon%20shoki.html (accessed on 4 August 2025).Dōshin 道振. Shoseki Engishū 諸寺縁起集. Muromachi period.Sugano no Mamichi 菅野真道 (AD 741–814), et al. Meiji period (AD 1868–1912). Shoku Nihongi, vol. 8 続日本紀巻8. Osaka: Zōgeya Jirōbee 象牙屋治郎兵衛. Available online: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/1089500/1/54 (accessed on 4 August 2025).Secondary Source

- Aboshi, Yoshinori 網干善教. 2006. Hekiga Kofun no Kenkyu 壁画古墳の研究 (A Study of Painted Tombs). Tokyo: Gakuseisha 学生社. [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma, Takeshi 淺湫毅. 1993. Yakushiji kondo honzon daiza no igyozō ni tsuite 薬師寺金堂本尊台座の異形像について (On the Grotesque Figures on the Pedestal of the Main Icon in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji). Bukkyō Geijutsu 仏教芸術 (Buddhist Arts) 208: 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Asuka Historical Museum, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Independent Administrative Institution 独立行政法人文化財研究所奈良文化財研究所飛鳥資料館. 2006. Kitora Kofun to Hakkutsu Sareta Hekiga Tachi キトラ古墳と発掘された壁画たち (The Kitora Tomb and Unearthed Murals). Nara: Asuka Historical Museum, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Independent Administrative Institution 独立行政法人文化財研究所奈良文化財研究所飛鳥資料館. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Wen 白文. 2010. Guanzhong tangdai Yaoshifo zaoxiang tuxiang yanjiu 關中唐代藥師佛造像圖像研究 (On the Images of Sculptures of the Pharmacist Buddha in Guanzhong in the Tang Dynasty). Shaanxi Shifan Daxue Xuebao 陝西師範大學學報 (Journal of Shaanxi Normal University) 39: 148–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bogel, Cynthea J. 2021. Un cosmoscape sous le Bouddha: Le piédestal de l’icône principale de Yakushi-ji, soutien de l’empire des souverains (A Cosmoscape beneath the Buddha: The Pedestal of the Main Icon of Yakushi-ji, Support of the Sovereigns’ Empire.). Perspective 1: 141–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Qing 常青. 2021. Chengdu Wanfosi Yaoshifoxiang yu Nanbeichao Yaoshifo xinyang 成都萬佛寺藥師佛像與南北朝藥師佛信仰 (The Bhaiṣajyaguru Image of Chengdu Ten-Thousand Buddha Monastery and the Bhaiṣajyaguru Worship of the Southern Northern Dynasties). Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 (Palace Museum Journal) 7: 4–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cixian Cultural Center 磁縣文化館. 1984. Hebei Cixian Dongwei Ruru gongzhumu fajue jianbao 河北磁縣東魏茹茹公主墓發掘簡報 (Brief Report on the Excavation of the Eastern Wei Tomb of Princess Ruru in Cixian, Hebei). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 4: 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Relics Team of the Liaoning Provincial Museum 遼寧省博物館文物隊. 1984. Chaoyang Yuantaizi Dongjin bihuamu 朝陽袁台子東晉壁畫墓 (The Eastern Jin Mural Tomb at Yuantaizi, Chaoyang). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 6: 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Donohashi, Akio 百橋明穂. 2013. Guihugufen de Sishentu 龜虎古墳的四神圖 (The Four Divine Beasts in the Kitora Tomb). In Dongying Xiyu––Baiqiao Mingsui Meishushi Lunwenji 東瀛西域––––百橋明穗美術史論文集(Eastern Seas and Western Regions: Collected Art Historical Essays of Donohashi Akio). Shanghai: Shanghai Calligraphy and Painting Publishing House 上海書画出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Wenjie 段文傑. 2007. Daojiao ticai shi ruhe jinru fojiao shiku de––Mogao ku di 249 ku kuding bihua neirong tantao 道教題材是如何進入佛教石窟的––––莫高窟第249窟窟頂壁畫內容探討 (How the Daoist Subject Entered the Buddhist Grottoes—A Study of the Murals on the Ceiling in Cave 249 of Mogao Grottoes). In Dunhuang Shiku Yishu Yanjiu 敦煌石窟藝術研究 (A Study of Dunhuang Cave Art). Lanzhou: Gansu Renmin Chubanshe 甘肅人民出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Committee for the Complete Collection of Chinese Cave Sculpture 中國石窟雕塑全集編輯委員會. 2001. Zhongguo Shiku Diaosu Quanji: Beifang Liusheng 中國石窟雕塑全集·北方六省 (Collection of Chinese Cave Sculpture: Six Northern Provinces). Chongqing: Chongqing Chubanshe 重慶出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Guangdong Provincial Cultural Relics Management Committee 廣東省文物管理委員會. 1961. Tangdai Zhangjiuling mu fajue jianbao 唐代張九齡墓發掘簡報 (Brief Report on the Excavation of the Tang Dynasty Tomb of Zhang Jiuling). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 6: 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, Ryōichi 林良一. 1959. Yakushiji kondo honzon daiza no budō karakusa monyō 薬師寺金堂本尊台座の葡萄唐草紋様 (The Grapevine Arabesque Motif on the Pedestal of the Main Icon in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji). Kokka 国華 810: 341–52. [Google Scholar]

- Itō, Shirō 伊東史朗. 1987. Budō monyō no ittenkai––yakushiji kondo daiza no monyō o megutte 葡萄文様の一展開: 薬師寺金堂台座の文様をめぐって (A Development of the Grape Motif: On the Patterns of the Pedestal in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji). Gakusō 学叢 9: 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kameda, Tsutomu 亀田孜. 1948. Zuzō toshite mita Yakushi Nyorai 図像として見た薬師如来 (Interpreting Yakushi Nyorai as Iconography). Nihon Bijutsu Kōgei 日本美術工芸 (Japanese Arts and Crafts) 114: 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kikutake, Junichi 菊竹淳一. 1998. Sekai bijutsu taikei: Tōyō hen 1 世界美術大全集 東洋編1 (World Art Compendium, Eastern Section 1). Tokyo: Shōgakukan 小学館. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, Shoken 小島章見. 1948. Yakushiji kondo honzon daiza ni tsukite 薬師寺金堂本尊台座につきて (On the Pedestal of the Main Icon in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji). Nihon Bijutsu Kōgei 日本美術工芸 (Japanese Arts and Crafts) 114: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xingming 李星明. 2001. Tangmu Bihua Kaoshi 唐墓壁畫考識 (An Investigation into Tang Tomb Murals). In Tangmu Bihua Yanjiu Wenji 唐墓壁畫研究文集 (Collected Essays on the Study of Tang Tomb Murals). Edited by Zhou Tianyou 周天游. Xi’an: Sanqin Chubanshe 三秦出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xingming 李星明. 2003. Beichao Tangdai bihuamu yu muzhi de xingzhi he yuzhou tuxiang zhi bijiao 北朝唐代壁畫墓與墓誌的形制和宇宙圖像之比較 (A Comparison of the Formal Design and Cosmological Imagery of Murals and Epitaphs in Tombs of the Northern Dynasties and Tang Dynasty). Meishu Guancha 美術觀察 (Art Observation) 6: 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xingming 李星明. 2005. Tangdai Mushi Bihua Yanjiu 唐代墓室壁畫研究 (A Study of Tang Dynasty Tomb Murals). Xi’an: Shanxi Renmin Meishu Chubanshe 陝西人民出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Luoyang Museum 洛陽博物館. 1974. Henan Luoyang Beiwei Yuancha mu diaocha 河南洛陽北魏元乂墓調査 (Report on the Tomb of Yuan Ai of the Northern Wei in Luoyang, Henan). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 12: 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Machida, Kōichi 町田甲一. 1988. 薬師寺 (The Yakushi-ji). Tokyo: Graph-sha グラフ社. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, Masaaki 松浦正昭. 2004. Nihon No Bijutsu 455: Asuka Hakuhō No Butsuzō 日本の美術455: 飛鳥白鳳の仏像 (Japanese Art 455: Buddhist Sculptures of the Asuka and Hakuhō Periods). Tokyo: Shibundō 至文堂. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka, Ryūsaku 長岡龍作. 2003. Shumiza kō––yakushiji kondo Yakushi Nyorai-zō no daiza o megutte 須弥座考―薬師寺金堂薬師如来像の台座をめぐって (A Study of the Statue Pedestal: On the Pedestal of the Yakushi Nyorai Statue in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji). In Nihon Jōdai ni Okeru Butsuzō no Shōgon Kenkyū Seika Hōkokusho 日本上代における仏像の荘厳研究成果報告書 (Report on Research Results Concerning the Ornamentation of Buddhist Images in Early Japan). Nara: Nara National Museum, pp. 139–49. [Google Scholar]

- Nara Rokudaiji Taikan Kankōkai 奈良六大寺大観刊行会. 1970. Nara Rokudaiji Taikan Kankōkai 奈良六大寺大観刊行会 Nara Rokudaiji Taikan·Hōryūji·2 奈良六大寺大観·法隆寺·二 (Comprehensive Survey of the Six Great Temples of Nara: Hōryū-ji, Vol. 2). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten 岩波書店. [Google Scholar]

- Puyang City Cultural Relics Management Committee 濮陽市文物管理委員會. 1988. Henan Puyang Xishuipo yizhi fajue jianbao 河南濮陽西水坡遺址發掘簡報 (Report on the Excavation of the Xishuipo Site in Puyang, Henan). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 3: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, Wanli 冉萬里. 2013. Zhongguo Gudai Sheli Yimai Zhidu Yanjiu 中國古代舍利瘞埋制度研究 (A Study of the Burial Systems of Relics in Ancient China). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Saitō, Rieko 斎藤理恵子. 2001. Dunhuang di 249 ku tianjing Zhongguo tuxiang neihan de bianhua 敦煌第249窟天井中國圖像內涵的變化 (Changes in the Chinese Iconographic Content of the Ceiling in Dunhuang Cave 249). Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 (Dunhuang Research) 68: 154–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shaanxi Provincial Academy of Social Sciences, Institute of Archaeology 陝西省社會科學院考古研究所. 1963. Shaanxi Xianyang Tang Sujun mu fajue 陝西咸陽唐蘇君墓發掘 (Excavation of the Tang Dynasty Tomb of Su Jun in Xianyang, Shaanxi). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 9: 493–98. [Google Scholar]

- Shandong Museum 山東省博物館. 1981. Shandong Jiaxiang Yingshan 1 hao Sui mu qingli jianbao––Suidai mushi bihua de shouci faxian 山東嘉祥英山一號隋墓清理簡報––––隋代墓室壁畫的首次發現 (Report on the Clearance of Sui Tomb No. 1 at Yingshan, Jiaxiang, Shandong: The First Discovery of Sui Dynasty Tomb Murals). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 4: 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shandong Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 山東省文物考古研究所. 2002. Shandong Linqu Beiqi Cuifen bihuamu 山東臨朐北齊崔芬壁畫墓 (The Mural Tomb of Cui Fen of the Northern Qi in Linqu, Shandong). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 4: 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology 山西省考古研究所. 2006. Beiqi Donganwang Lourui Mu 北齊東安王婁睿墓 (The Tomb of Lou Rui, Prince of Dong’an of the Northern Qi). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Ruiwen 沈睿文. 2023. Dunhuang 249, 285 ku de kuding tuxiang 敦煌249、285窟的窟頂圖像 (On the Muraled-Ceiling Images of Mogao Caves 249 and 285). Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 (Palace Museum Journal) 6: 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Shimotsuke, Suzuko 下野鈴子. 2000. Kondō Yakushi Nyorai-zō daiza 金堂薬師如来像台座 (The Pedestal of the Yakushi Nyorai Statue in the Kondō). In Yakushiji Sen Sanbyaku-nen no Seika––Bijutsushi Kenkyū no Ayumi 薬師寺千三百年の精華––美術史研究のあゆみ (The Splendor of 1300 Years of Yakushi-ji: Milestones of Art Historical Research). Tokyo: Ribon Publishing 里文出版. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan Museum 四川省博物館. 1980. Sichuan Wanxian tangmu 四川萬縣唐墓 (Tang Dynasty Tomb in Wanxian, Sichuan). Kaogu Xuebao 考古學報 (Acta Archaeologica Sinica) 4: 503–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan Museum 四川省博物館, Chengdu Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 成都文物考古研究所, and Sichuan University Museum 四川大学博物馆. 2013. Sichuan Chutu Nanchao Fojiao Zaoxiang 四川出土南朝佛教造像 (Buddhist Statues of the Southern Dynasties Excavated in Sichuan). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Tobana, Arisu 戸花亜利州. 2009. Yakushiji kondo Yakushi Nyorai-zō daiza igyōzō to konkōmyōkyō 薬師寺金堂薬師寺如来像台座異形像と金光明経 (The Grotesque Figures on the Pedestal of the Yakushi Nyorai Statue in the Kondō of Yakushi-ji and the Golden Light Sūtra). Nara Gaku Kenkyū 奈良学研究 (Nara Studies) 11: 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hong. 2024. Rethinking Asuka Sculpture: A Revised Conception of Buddhist Spread in East Asia, 538-710. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Genqi 閻根齊, ed. 2001. Mangdangshan Xihan Liangwang Mudi 芒碭山西漢梁王墓地 (The Tomb Complex of King Liang of the Western Han at Mangdang Mountain). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Yao 姚瑶. 2022. Riben Yaoshisi Jintang Yaoshisanzunxiang yu xiangguan Tangdai fojiao zaoxiang yanjiu 日本藥師寺金堂藥師三尊像與相關唐代佛教造像研究. (A Study on the Triad of Buddhist Statues in the Main Hall of the Yakushi-ji Temple in Japan and Similar Statues from the Tang Dynasty). Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 (Dunhuang Research) 3: 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yunnan Provincial Cultural Relics Work Team 雲南省文物工作隊. 1963. Yunnan Zhaotong Houhaizi Dongjin bihuamu qingli jianbao 雲南省昭通後海子東晉壁畫墓清理簡報 (Report on the Clearance of an Eastern Jin Mural Tomb at Houhaizi, Zhaotong, Yunnan Province). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 12: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Hongxiu 張鴻修. 1992. Tangdai Muzhi Wenshi Xuanbian 唐代墓誌紋飾選編 (Selected Decorative Patterns from Tang Dynasty Epitaphs). Xi’an: Shaanxi Meishu Chubanshe 陝西美術出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Hongxiu 張鴻修. 2001. Tangmu bihua yishu jiqi linmo 唐墓壁畫藝術及其臨摹. In Tangmu Bihua Yanjiu Wenji 唐墓壁畫研究文集 (Collected Essays on the Study of Tang Tomb Murals). Edited by Zhou Tianyou 周天游. Xi’an: Sanqin Chubanshe 三秦出版社. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).