1. Introduction1

This research undertakes a visual analysis of the figure of the witch, understood not only as a symbolic agent of evil, but also as an object of desire, transgression, and symbolic power. From illuminated manuscripts to Renaissance painting and early modern prints, visual culture has played a decisive role in shaping the ways in which the witch has been imagined, feared, and represented.

Throughout history, the witch has been constructed within a dual and contradictory imaginary: on one hand, deformed, aged, and terrifying women associated with dark wisdom and the demonic; on the other, young, beautiful, and dangerously seductive women whose bodies embody both temptation and threat. Within this broad spectrum of archetypes, the biblical and almost enigmatic figure of the Necromancer of Endor stands out with particular force. Although her appearance in the narrative of 1 Samuel

2 is brief, it is charged with theological, symbolic, and political tensions. Despite the limited information available about her, she has traditionally been interpreted through patriarchal frameworks that relegate her to the margins of the sacred, portraying her as a transgressor of divine law. Yet far from being a marginal or secondary character, the woman of Endor has functioned as a symbolic matrix that reappears across centuries of visual and textual discourses, shaping the shifting construction of the archetypal witch.

Adopting an interdisciplinary perspective that brings together cultural biblical studies, art history, and gender studies, this paper seeks to reassess the image and function of the Necromancer of Endor through well-established hermeneutical approaches. Within this framework, the methodology of visual exegesis

3 becomes especially relevant, integrating textual analysis with the iconographic interpretation of artistic representations. From this hermeneutical perspective, the image is not conceived as a mere illustration of the text but as an autonomous space of meaning production where biblical studies, aesthetics, and culture intersect. The aim is to offer alternative interpretations that recognize her agency, her role in spiritual mediation, and her power as a figure of female dissent.

2. A Cultural Genealogy of the Witch in Western Thought: From Myth to Persecution

The figure of the witch in Western culture is shaped through a complex web of myths, religious discourses, and visual representations extending from Antiquity to the early modern period. Tracing this genealogy reveals that the Witch of Endor is not an isolated episode in the Bible but a symbolic matrix that reappears and is reformulated in multiple contexts where the feminine, the spiritual, and the transgressive converge.

In the ancient Mediterranean world, characters such as Circe and Medea, among many others, embodied the ambivalence of female power—wise women and sorceresses capable of seduction, bodily transformation, and social disruption. Alongside them, nocturnal demons such as the lamiae and striges—child-devouring creatures associated with darkness—consolidated the idea of the feminine as a link between the erotic and the monstrous (

Graf 1997, pp. 21–26;

Ogden 2002, pp. 78–94). These figures provided a symbolic repertoire that would later be reactivated and reframed within a Christian key

4.

Biblical and patristic tradition reinforced this negative association. Deuteronomy condemned divination and necromancy (Deut 18: 10–12), defining a framework in which female mediators were excluded from the sphere of the sacred.

Augustine of Hippo (

1988) reinterpreted such practices as the work of the devil, asserting that all magic was a form of idolatry and demonic deception. This interpretation had far-reaching consequences: any form of feminine spiritual mediation was assimilated to heretical deviation, with medieval theologians referring to these women as

haeretici fascinarii,

sortilegi haereticales, or

secta strigarum (

Russell 1972, p. 219).

During the early Middle Ages, however, the official position remained ambivalent. The

Canon Episcopi (ninth–tenth centuries) denied the reality of nocturnal flights by women who followed the Roman goddess Diana or the biblical Herodias, considering them demonic illusions rather than verifiable events (

Cohn 2005). The emphasis was still on correcting popular superstitions rather than prosecuting them.

This fragile balance collapsed at the end of the Middle Ages, when the context of plague, war, and schism intensified the need for scapegoats. Between 1420 and 1430 the essential elements of the demonological imagination were established: the diabolical pact, flight, the sabbath, and infanticide. The

Malleus Maleficarum (1487), written by the Dominican inquisitors Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, consolidated this vision and emphasized its gendered dimension, claiming that women were more prone to witchcraft because of their supposed moral and physical weakness (

Kieckhefer 1976;

Levack 1987):

But since in our times witchcraft is found more often among women than among men, as experience has taught us, if anyone should wonder why, we may add the following: because of the weakness of their minds and bodies, it is not surprising that they fall more readily under the spell of witchcraft […]. For in matters concerning intelligence or the comprehension of spiritual things, they seem to be of a different nature than men, a fact confirmed by the reasoning of the authorities and supported by numerous examples from Scripture […]. Therefore, a wicked woman is naturally more ready to waver in her faith and thus to abjure it, which constitutes the very essence of witchcraft.

The construction of the witch was not merely discursive but profoundly visual. From the miniatures of moralized Bibles, where magical practices appeared in parallel with spiritual admonitions, to the engravings of the German painter Hans Baldung Grien in the sixteenth century, the witch became a body marked by nakedness, transgression, and spectral threat (

Clark 1999). These images were not mere illustrations; they functioned as pedagogical and spiritual devices intended to shape perceptions of sin and collective fear.

The background of this visual imagery was also linked to medieval conceptions of the afterlife. The Middle Ages developed a rich topography of the spectral—returning dead, apparitions, and mediations between the living and the deceased (

Le Goff 1984, pp. 52–60). Within this horizon, the biblical figure of the Witch of Endor is best understood as a liminal character: a mediator between worlds, capable of summoning the shades that rise from the earth and of challenging the boundaries between the sacred and the forbidden.

Finally, it should be stressed that this genealogy is traversed by the dimension of the female body. In medieval Christianity, women’s corporeality became laden with spiritual and ambivalent meanings—at once a site of sanctity and of suspicion. The witch thus embodies the diabolical inversion of that power, occupying the point at which female spirituality is rewritten as transgression (

Walker Bynum 1987,

1991).

In sum, the cultural genealogy of the witch weaves together ancient myth, patristic theology, devotional practice, jurisprudence, and artistic imagery. Within this intricate network, the Witch of Endor emerges as a privileged symbolic knot: not a marginal character but a precedent that feeds, redefines, and projects the image of the witch across centuries of art, spirituality, and religion.

3. The Female Body as Site of Sin and Temptation: From Eve to the Witch

One of the fundamental axes in the construction of the witch in Western tradition is the association of the female body with excess, temptation, and transgression. From biblical narratives to medieval and Renaissance iconography, women’s corporeality was conceived as ambivalent: simultaneously a source of life and a site of spiritual danger

5. This perception became a symbolic matrix that nourished later representations of the witch, shaping her image as the embodiment of carnal sin and the destabilizing power of femininity.

3.1. Eve as a Symbolic Matrix of the Fall

The first figure within this tradition is Eve. In the Genesis narrative (Gen 2–3), her role is not limited to an act of disobedience, but is articulated through listening, interpretation, and mediation: she engages the serpent’s discourse, evaluates the forbidden fruit, and transmits both word and action to the man. As numerous studies have shown, this configuration situates Eve as a mediating figure whose body and agency become implicated in the entrance of sin into the world (

Trible 1978;

Bal 1987). Early Christian reception accentuated this reading. Paul explicitly presents Eve as the archetype of the one who is deceived and thus becomes a paradigm for error and corruption (2 Cor 11: 3; 1 Tim 2: 13–14). Patristic thought accentuated this interpretation: Tertullian, in his treatise

De cultu feminarum,The Adornment of Women (

Tertullian 2001, I, 1), defines woman as

porta diaboli—the gate through which the devil enters the world. Medieval iconography reinforced this reading (

Bornay 2023, pp. 143–46): Eve appears naked, embracing or in contact with the serpent, emphasizing the union between body, temptation, and the Fall (

Miles 1989).

In this sense, Eve became a visual and theological paradigm of suspicion toward women, whose bodies—exposed, vulnerable, and generative of desire—were viewed as channels of spiritual corruption. It is no coincidence that many demonological treatises, including the Malleus Maleficarum, established a direct link between women’s supposed inclination toward evil and Eve’s legacy:

But the natural reason lies in the fact that [woman] is more carnal than man, as is evident in her carnal abominations. And note that there was a defect in the formation of the first woman, for she was made from a curved rib, that is, a rib of the chest that is bent, as it were, in the opposite direction from that of a man. Because of this defect, she is an imperfect animal, always deceitful […]. And this is evident in the case of Eve.

3.2. Salome and Herodias: Eroticism, Excess, and Death

Other biblical figures reinforced the association between femininity, flesh, and excess. Salome—whose dance led to the beheading of John the Baptist (Mk 6: 17–29; Mt 14: 3–11)—became a symbol of the dangerous woman whose bodily allure brings about destruction. Although the Gospel narrative does not mention her name, Christian tradition identified her as the embodiment of the

femme fatale, whose sensuality causes the prophet’s downfall (

Meltzer 1989). In medieval and Renaissance iconography, Salome appears as a seductive young woman, often depicted at banquets or holding the Baptist’s head, marking the union between eroticism and violence (

Expósito de Vicente 2024).

Her mother, Herodias, also played a key symbolic role. The

Canon Episcopi (ninth–tenth centuries), a foundational text in the medieval conception of witchcraft, claimed that some women believed they flew by night in the company of Diana or Herodias. Although the Church classified these experiences as demonic illusions, the association of Herodias with nocturnal female processions introduced a central motif in the future imagination of the witches’ sabbath (

Cohn 2005, pp. 209–10). The combination—and often iconographic confusion—of Salome and Herodias thus reinforced the idea of the female body as a space of erotic excess and spiritual subversion.

3.3. The Female Body as a Site of Suspicion

In scholastic theology, Thomas Aquinas held that woman was created as “a help to man in the work of generation” (

Aquinas 1958,

Summa Theologiae, I, q. 92, a. 1, ad 2), being

deficiens et occasionatus vir (I, q. 92, a. 1; I, q. 99, a. 2)—that is, an imperfect form of man, although sharing with him the same rational nature. This conception contributed to consolidating a hierarchical anthropology that, in later Christian tradition, associated the feminine with the weakness of the flesh and the sins of lust and gluttony.

In her studies of medieval spirituality,

Walker Bynum (

1987,

1991) has shown how the female body acquired a particularly charged meaning: a locus of mystical and holy experience (through fasting, vision, and ecstasy), but also a space suspected of instability and excess. In this sense, the witch represents the diabolical inversion of that sacred corporeality: instead of being an instrument of union with the divine, the female body is perceived as the channel through which the demonic enters.

3.4. Iconography of the Tempting and Demonic Body

Visual imagery played a decisive role in fixing these associations. In illuminated manuscripts and moralized Bibles, Eve often appears as a counterpoint to Mary, symbolizing fallen flesh in contrast to redemptive virginity (

Mocholí Martínez 2022, p. 24). Other biblical women, such as Salome, also suffered from patriarchal interpretations of their bodies and actions—represented as attractive young women whose gesture of holding the Baptist’s head underscores the violence of female seduction (

Bornay 2023, pp. 143–70).

In the Renaissance, artists such as Hans Baldung Grien took this imagery to a new level. His engravings of witches (

ca. 1510–1525) depict naked female bodies, both young and old, in explicitly sexual or grotesque postures. These images express the gender anxieties of the time, projecting onto the female body both desire and fear (

Roper 2004, pp. 151–59). Baldung also establishes a visual parallel between Eve and the witch: both appear nude, accompanied by animal and demonic symbols—both mediators of an evil transmitted through the body.

The trajectory from Eve to Renaissance witch iconography shows how the female body became increasingly loaded with negative meanings within the Christian imaginary. Certain biblical women, viewed through the patriarchal lens, functioned not only as symbolic precedents but also as frameworks of suspicion in which female corporeality was associated with temptation, lust, and idolatry

6. Within this horizon, late medieval and Renaissance images of witches—such as those by Hans Baldung Grien—did not emerge ex nihilo, but condensed centuries of theological interpretations, biblical narratives, and visual tropes. The female body, transformed into a stage for excess and transgression, became a privileged site for the construction of the demonic, preparing the ground for the witch to embody, once and for all, the tension between the sacred and the forbidden.

4. The Witch as Mediator Between Worlds: From Psychopompos to “Summoner of Demons”

The religious imagination of Antiquity conceived without difficulty the possibility of transit between the living and the dead. The role of the

psychopompos—the guide of souls—was associated with liminal divine figures such as Hermes, Hecate, or Persephone, linked to threshold crossings and to practices of necromancy (

Ogden 2001, p. 8;

Johnston 1999). Literary scenes such as the

Nekyia of the Odyssey—the opening of a threshold between realms that enables communication with the dead—in which Odysseus consults the departed under the instruction of Circe, illustrate how this mediation formed part of a cultural repertoire articulating the relationship between the living and the memory of the dead (

Graf 1997, pp. 101–5). Far from being considered necessarily illicit, these practices could perform legitimate religious functions.

With Christian patristics, mediation between the living and the dead acquired a very different meaning. The Church Fathers established a clear boundary between legitimate cult and necromancy, considering communication with the deceased as an area prone to demonic deception. In Augustinian thought, communication with the dead had to be approached with extreme caution. In

De divinatione daemonum (ch. 3) (

Augustine of Hippo 1956, PL 40, 582, p. 705), the theologian maintains that apparitions attributed to the departed are not true manifestations of their souls but illusions produced by demonic spirits seeking to deceive humankind. Complementarily, in

De cura pro mortuis gerenda (ch. 10) (

Augustine of Hippo 1956, PL 40, 601–602, p. 732) he warns that such phenomena must be interpreted with prudence, for “not everything that is seen is true”. Both treatises thus consolidate a theological attitude of distrust toward mediation with the beyond, one that would shape subsequent Christian tradition. This reading transferred the ancient mediating functions into the realm of error and idolatry, reinforcing the idea that women engaged in magical or divinatory practices were not guides of souls but agents of the devil (

Caciola 2003, pp. 7–9, 33–36).

In parallel, medieval Christian theology elaborated a rich topography of the afterlife: the emergence of purgatory as an intermediate place multiplied accounts of apparitions and spectral returns, always subjected to ecclesiastical discernment (

Le Goff 1984, pp. 130–33). Communication with the dead thus became a field of tension—simultaneously fascinating, perilous, and institutionally controlled.

Within this cultural background are also inscribed certain biblical narratives that recount attempts to access voices from beyond through female mediation. These scenes reveal the persistence of a liminal, ambivalent figure situated between the sacred and the forbidden. In later centuries, both Christian exegesis and visual culture would tend to reinterpret these mediators not as ritual guides of the souls’ passage but as “summoners of demons,” thereby fixing one of the central matrices in the construction of witchcraft in the West.

The Necromancer of Endor: “The Dead Who, Like Gods, Rise from the Earth and Speak”

The episode of the woman of Endor, narrated in 1 Samuel 28: 3–25, is one of the most enigmatic accounts in the Hebrew Bible. In it converge theological, social, and gender tensions that destabilize the normative framework of ancient Israel. King Saul, abandoned by the legitimate means of communication with God—the dreams, the Urim and Thummim

7, or the prophets—secretly turns to a woman medium at the darkest moment of his leadership. With this gesture he directly contradicts his own policy of expelling diviners from the land (1 Sam 28: 3), revealing the profoundly human character of his despair.

The narrative context, set amid the conflicts with the Philistines toward the end of the eleventh century BCE, introduces a marginal figure—

ʾēšet baʿalat-ʾov, or “female necromancer”

8—who paradoxically plays a central role in transmitting the divine will. Despite the explicit prohibition of the Law against necromancy (Lev 19: 31; Deut 18: 11), the story admits not only the persistence of such practices in Israel but also their efficacy. Yet the narrative itself underscores the woman’s awareness of the legal and political danger surrounding her practice. Before performing the rite, she explicitly reminds Saul of his own crackdown on mediums and spirit-diviners and asks why he would “entrap” her and expose her to death (1 Sam 28: 9). Saul responds not only with reassurance but with a formal oath, swearing by God that “no guilt” will come upon her because of this act (v. 10). As

Hamori (

2015, p. 119) observes, the exchange foregrounds the woman’s caution and agency: she does not function as a reckless transgressor, but as a practitioner who recognizes the risk and negotiates the conditions under which she will proceed. The woman succeeds in “bringing up” the prophet Samuel, described as “a divine being coming up out of the earth” (1 Sam 28: 13), underscoring the numinous and liminal character of the apparition (

McCarter 1980, pp. 420–24).

The scene unfolds in three narrative moments: first, Saul’s despair and his decision to consult the medium (vv. 3–7); then the nocturnal encounter and Samuel’s evocation (vv. 8–20); and finally, the woman’s gesture of hospitality as she feeds the defeated king before his last battle (vv. 21–25). Each part contributes to building a tension between prohibition and necessity, between ritual illegality and prophetic truth. The second act is particularly revealing: despite the risk of death, the woman grants Saul’s request, demonstrates ritual competence, and succeeds in mediating between worlds. Samuel’s oracle—devastating and irrevocable—confirms Saul’s fate. Yet the third act offers an unexpected contrast: the woman tends to and feeds the king in a gesture at once profoundly human and ritual. The closing scene further reinforces this narrative asymmetry. Saul collapses in fear and exhaustion, while the woman stands over him and speaks with authority: “I listened to you … now you listen to me”; and ensures that he eats (vv. 20–25). Her authority is not diminished by any narrative assignment of guilt; on the contrary, Saul’s oath explicitly frames her as not bearing guilt (v. 10), a nuance often softened in translation (

Hamori 2015, pp. 127–28).

Exegetical tradition has oscillated between interpreting the episode as a genuine

redivivus of Samuel or as a demonic illusion permitted by God, in line with patristic and scholastic readings. Other modern interpreters, however, have emphasized the literal meaning of the text, which leaves no doubt about the ritual’s efficacy (

McCarter 1980, pp. 420–24). This hermeneutical ambiguity precisely reflects the tension between an ancient form of ritual mediation and its later demonization within Christian tradition. This attention to the narrative dynamics of 1 Samuel 28 complicates the long-standing interpretive tendency to cast the woman of Endor as the primary object of condemnation. The Samuel narrative displays remarkably little interest in denouncing either the act of necromancy or the necromancer herself. The message delivered by Samuel’s ghost rebukes Saul for his prior disobedience—most notably in the matter of the Amalekites—rather than for consulting the necromancer, and the text nowhere registers an explicit divine objection to the consultation as such (

Hamori 2015, pp. 127–28). From a narrative perspective, Saul emerges as increasingly disqualified from kingship, while the necromancer, by contrast, is portrayed as a competent and authoritative mediator who successfully provides access to knowledge when dreams, prophets, and the Urim fail (

Hamori 2015, p. 129). This contrast becomes particularly evident when the episode is read alongside its retelling in 1 Chronicles 10: 13–14, where Saul’s consultation of the necromancer is explicitly reframed as a decisive transgression. As

Hamori (

2015, pp. 129–30) notes, this later account reveals how subsequent interpretive traditions intensify a condemnatory reading that the Samuel narrative itself does not foreground.

From a gender perspective, the woman of Endor aligns with other female figures in the Samuel cycle—Hannah, the prophet’s mother (1 Sam 1), or the wise woman of Tekoa (2 Sam 14), who enters the scene after the devastating episode of Tamar, King David’s daughter—who, from marginal positions, mediate in decisive moments of history. Her body and her voice become channels of revelation, exercising a symbolic authority that exceeds the limits of a patriarchal and centralized system. Far from being a mere anonymous medium, her actions articulate a triple role: prophetic, ritual, and compassionate.

In the broader horizon of the history of religions, the ʾēšet baʿalat-ʾov of Endor emerges as a paradigmatic liminal figure: she connects life and death, power and vulnerability, judgment and care. At the same time, her ambiguous position between what is permitted and what is forbidden anticipates the later construction of the witch as a dangerous mediator between worlds. Her story serves—among many subsequent discourses—as a hinge for examining how theological and visual traditions projected onto her, and onto analogous figures, the imaginary of witchcraft in which the sacred and the demonic become entwined.

5. Rising Shadows: The Aesthetics of the Spectral in the Necromancer of Endor

While the biblical narrative allows the woman of Endor to emerge as a remarkably agentive figure—one who recognizes the dangers of her practice, negotiates the terms of the encounter, and ultimately mediates access to knowledge when royal and prophetic channels have failed—Western visual reception tends to reverse this asymmetry. In the longue durée of Christian and post-medieval imagination, the authority that 1 Samuel 28 implicitly grants to this female ritual mediator is progressively displaced, re-coded, and finally neutralized: rather than being remembered as a practitioner who “comes off well” in contrast to Saul, she is increasingly absorbed into the collective iconography of witchcraft. This shift is not merely terminological but visual and ideological. The medium’s mediating function—her capacity to stand at the threshold, to address the dead, and to manage the encounter—often becomes secondary to signs that mark her as transgressive, suspicious, or demonic. The pictorial tradition frequently relocates agency away from her body and speech and into external forces: the apparition dominates the scene, male witnesses frame the action, or the woman’s presence is reduced to a sinister catalyst rather than a decisive interlocutor. In this way, the Western artistic afterlife of Endor participates in a broader process by which female mediation is rendered illegible as authority and reinterpreted as heterodoxy: what the biblical text presents as a complex and narratively productive form of female dissent is visually transformed into an emblem of illicit power, and eventually into an heir of the witch archetype itself. It is precisely in the formal strategies of representation—placement within the pictorial space, gesture and gaze, the distribution of attention between bodies, and the iconographic coding of “the forbidden”—that this gradual delegitimation of Endor can be traced.

The episode of Endor, with its evocation of the dead and its transgression of normative boundaries, becomes a privileged site for artistic experimentation, particularly in periods when the prophetic, the supernatural, and the marginal feminine converge as charged symbolic categories. Artistic representations of the Necromancer of Endor consistently portray the woman as a visual threshold between worlds, the realm of the living and that of the dead, the divine and the forbidden. Her image is charged with tension: she is central to the narrated event yet often displaced within the pictorial frame, a reflection of the cultural ambivalence toward feminine mediation

9. Across the corpus analyzed below, Endor’s agency is repeatedly negotiated through a set of codified visual strategies: the partial concealment of the woman’s face or body (veil, shadow, back-turned posture), the selective exposure of male figures to the viewer’s gaze, and the redistribution of ritual agency from the woman’s speech and gesture to the apparition itself or to male witnesses who frame and authorize the scene.

5.1. William Blake: Vision, Expressivity, and the Breaking of Canons

Among William Blake’s most remarkable works stands the watercolor

The Ghost of Samuel Appearing to Saul (

ca. 1800) (

Figure 1). The English artist, known for his visionary spirituality and his rejection of academic tradition, often turned to biblical episodes that were rarely depicted in Western iconography, from prophetic visions such as Ezekiel’s to narrative scenes like Jacob’s ladder or the entombment of Christ.

In this work, Blake situates the female figure in a prominent compositional position, emphasizing her mediating role, while the scene accentuates gesture to heighten the drama of the encounter: the open hands of Saul and the woman, their intense gazes and slightly parted lips. Expressive force prevails over naturalistic representation, reflecting Blake’s visionary spirit in contrast to academic convention. The woman’s conspicuous visibility, her face, hands, and bodily orientation offered to the viewer, functions here as a visual authorization of her mediating role, in sharp contrast to later images in which that role will be progressively displaced or obscured.

By contrast, a work in dialogue with Henry Fuseli’s interpretation of the same episode,

The Spirit of Samuel Appearing to Saul (1783) (

Figure 2), shares with Blake’s version a visionary sensibility that transcends the biblical narrative. The medium does not completely kneel nor adopt an attitude of submission; her inclined body, almost suspended in the air, maintains her as an axis uniting both worlds. Her tense gesture and the radiance rising from the ground position her as a mediator of an ambiguous energy—both feared and necessary. Fuseli conceives necromancy not as moral transgression but as a liminal experience in which the feminine embodies the passage between the visible and the invisible. Yet even in Fuseli, the medium’s authority remains precarious: her body becomes the site where terror and necessity converge, while the apparition’s radiance begins to claim the visual primacy that later traditions will use to eclipse her agency.

5.2. Benjamin West: Dramatism, Theatricality, and Old Age

In

Saul and the Witch of Endor (1783) (

Figure 3), Benjamin West approaches the same episode through a neoclassical lens. The Anglo-American history painter was distinguished by his ability to dramatize biblical and political episodes in a moralizing key—such as the sacrifice of Isaac, the expulsion from paradise, or Christ healing the sick.

In West’s version, the scene of Endor unfolds with restrained drama, characteristic of late eighteenth-century neoclassical moralism. The composition is organized around three focal points: the medium, on the left, holds a staff and initiates the conjuration; in the center, the spectral figure of Samuel, wrapped in a white veil and surrounded by vapors, emerges with an admonitory gesture; and to the right, Saul collapses to his knees, his face hidden, while his attendants recoil in terror into the shadows. Crucially, the composition distributes visibility along gendered lines: Saul and his men are staged as spectators of the miracle and, simultaneously, as figures displayed to the viewer in a theatre of fear, whereas the woman’s ritual labor is reduced to a functional trigger at the edge of the scene. The supernatural light emanating from the prophet divides the space between revelation and darkness, intensifying the contrast between the divine and the forbidden. West avoids visionary exaltation and opts instead for moral theatricality: the scene does not glorify magic but transforms the prodigy into a lesson on the despair of power separated from God.

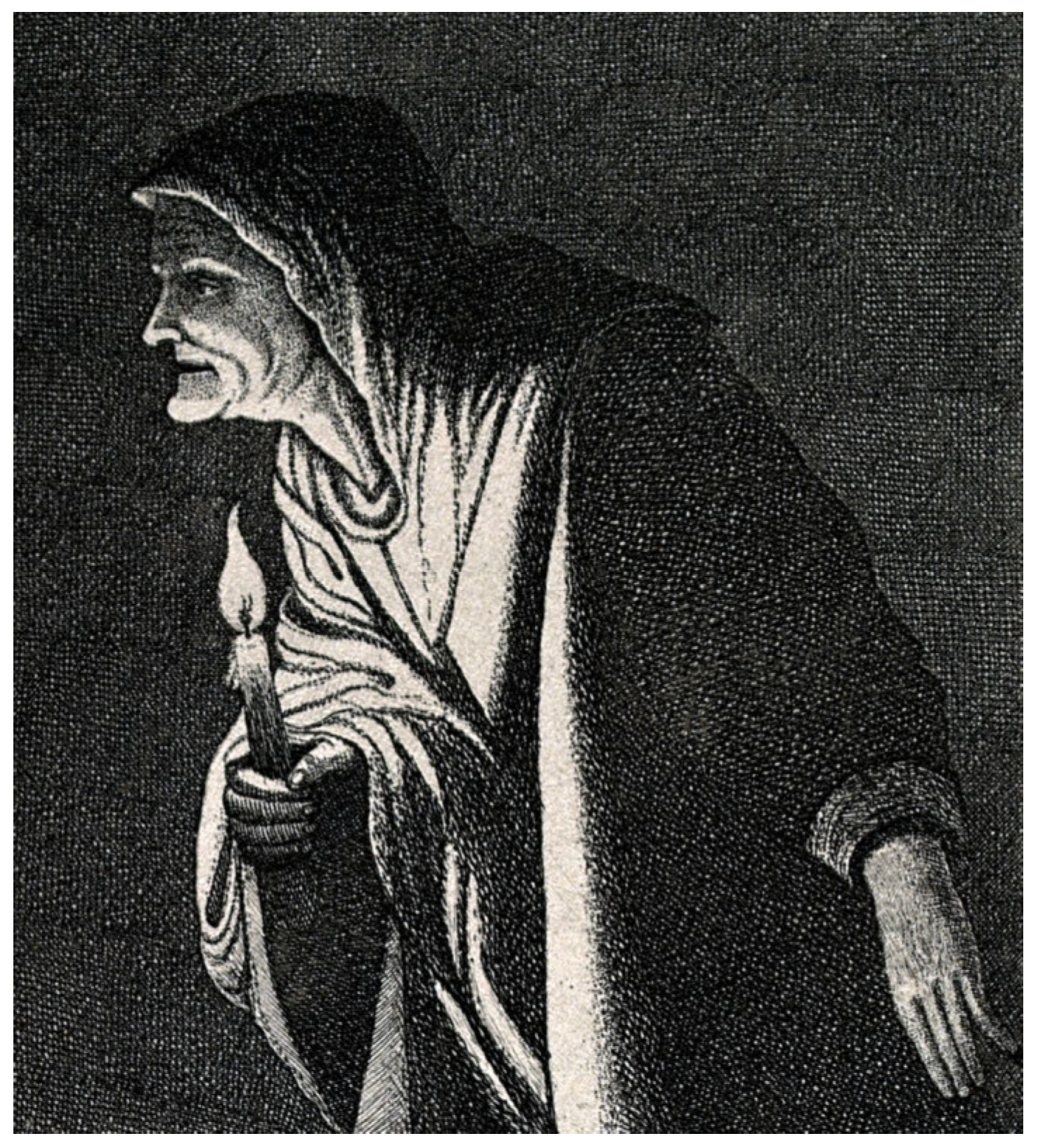

The image of the female mediator as an elderly woman, with sharp features and a disturbing gaze, coincides with the biblical interpretation of Adam Elsheimer, later engraved by John Kay at the beginning of the nineteenth century (

Figure 4). The engraving technique enhances the representation of old age and physical deformity as visual signs of transgression, reinforcing the association between occult knowledge, the female body, and moral decay. Still more terrifying are representations such as Gabriel Ehinger’s print (mid-seventeenth century)

10, in which the episode reaches an almost macabre intensity. At the center of a crypt or funerary chamber, the specter of Samuel rises from the ground still wrapped in burial shrouds. Before him, Saul bends in terror, body recoiled and face hidden, while the witch, in the foreground—her body almost disproportionate compared to the other figures and her torso bare—extends her hand in a gesture of invocation. Her face, furrowed by deep wrinkles and hollow eyes, verges on the inhuman. Her right hand, bony and outstretched, traces the conjuration gesture on the ground with an olive branch, while her left grips a small wand. In these prints, the medium’s body becomes an iconographic surface on which the moral meaning of the scene is inscribed: age, exposure, and distortion do not merely “characterize” her, but convert her into a readable emblem of transgression for a public that is positioned, like Saul’s men, as a consumer of spectacle and as an implicit participant in the moral judgment of the scene.

The scene is populated with signs of the uncanny: nocturnal animals (owls, snakes, lizards), spectral figures floating in the sky, and funerary architectures that transform the space into a threshold between the world of the living and that of the dead. Elements linked to the iconography of magic and ritual reinforce its spectral quality, as in the works of Philip James de Loutherbourg (1791) or Edward Henry Corbould in the nineteenth century.

5.3. Salvator Rosa: The Sublime, the Irrational, and the Liminal

Already in the seventeenth century, Salvator Rosa had addressed the theme in

The Shade of Samuel Appears to Saul (ca. 1668) (

Figure 5). Rosa, associated with the Italian Baroque, was particularly interested in the sublime, the irrational, and the fantastic, pushing beyond the boundaries of traditional history painting.

In Rosa’s version, the role of the witch differs radically from that offered by later artists. Here she is not a mere intermediary but a powerful figure, shrouded in shadow, who seems to command the energy of conjuration. Rosa’s witch does not simply mediate; she commands visually (upright, central, and legible) so that the spectator is compelled to read agency in her posture rather than in the apparition alone. Her upright body and gesture of invocation place her at the center of an atmosphere charged with supernatural tension, while around her demonic forms erupt, struggling to emerge from the abyss. Rosa represents the witch as a liminal space between the world of shadows and of light, of darkness and revelation. The specter of Samuel, bathed in cold light, radiates a clarity that does not redeem but delineates. Unlike Benjamin West’s moral equilibrium, Rosa explores the unsettling side of the biblical narrative and inscribes it within the Baroque imaginary of witchcraft and the demonic, where the marginal and the forbidden acquire their own aesthetic intensity.

A sense of liminality also appears with great visual clarity in Dmitry Martynov Nikiforovich’s

The Shade of Samuel Invoked by Saul (1857) (

Figure 6). To the left, the woman, standing and wrapped in a dark veil, raises both hands toward the apparition, as if channeling the supernatural light emanating from the specter. Her upright body acts as an axis of communication between two planes: the earthly, dominated by Saul’s reddish mantle and reinforced by a diagonal composition, and the spiritual, enveloped in a translucent luminosity, conveyed through the vertical arrangement. Yet Nikiforovich’s most revealing device is the woman’s orientation: she is turned away from the viewer, her face withheld, while the male figures (with the exception of the specter) remain fully exposed to the public gaze. The scene thus stages a gendered economy of visibility. Endor performs the rite, but her identity is visually bracketed; male bodies (fearful, reactive, and theatrically legible) become the privileged carriers of meaning. In this configuration, the woman’s agency is present yet veiled: it operates as a necessary condition of the apparition while being denied the representational visibility that would allow it to read as authority. A similar visual strategy can be observed in nineteenth-century Russian painting, for example, in Nikolai Ge’s

The Witch of Endor (ca. 1856)

11, where the woman’s posture and partial withdrawal from the viewer’s gaze contrast with the expressive centrality of Saul, reinforcing a gendered hierarchy of visibility.

Through these examples of the aesthetics of the spectral, the figure of the Necromancer of Endor is rewritten in very different keys: visionary and expressive, sinister and obscure, liminal and ritual. Yet in all of them, one element remains constant: the woman as a visual mediator between worlds, caught in the ambivalence of being at the center of the event and, at the same time, at the margins of representation. This ambivalence also manifests in the aesthetic construction of the witch’s figure—oscillating between old age and youth, between servitude and visionary authority, between the degraded body and the symbolic potency of one who sustains contact with the invisible. The aesthetics of the spectral thus reveal both the fascination with the supernatural and the cultural anxieties surrounding feminine knowledge and the transgression of religious boundaries.

6. Reemergence and Reformulation of the Myth

When analyzing the representations of the Necromancer of Endor in visual and theological history, one might assume that the myth and stigma of witchcraft have been confined to the past. Yet the twentieth century does not simply “leave behind” the demonological image forged in earlier periods; rather, it reworks it through new regimes of meaning. If early modern visual culture often displaced Endor’s agency by aligning spectatorship with male fear and by relocating ritual authority to the apparition, modern and contemporary contexts increasingly interrogate precisely those mechanisms of marginalization—visibility, voice, and the inscription of violence on the female body. For an early twentieth-century example of the motif’s persistence prior to the feminist reappropriations of the 1960s, see Adalbert Trillhaase,

Die Hexe von Endor (ca. 1927)

12. A closer examination of Trillhaase’s

Die Hexe von Endor complicates any assumption that increased visibility necessarily entails a positive re-evaluation of the figure. Although the woman occupies the foreground of the composition and commands immediate visual attention, her presence remains firmly inscribed within a negative iconographic register. Particularly striking is her yellow garment, a chromatic choice that resonates with a long visual tradition in which yellow functions as a marker of moral ambiguity, marginality, and suspicion, frequently associated with figures such as Judas Iscariot or, in more ambivalent ways, Mary Magdalene. As studies of medieval and early modern color symbolism have shown, yellow often carries a stigmatizing or morally ambivalent valence, especially in contexts of social or religious deviance (

Pastoureau 2006, pp. 228–38). Rather than signaling rehabilitation, this chromatic coding aligns the Witch of Endor with inherited visual languages of stigma, suggesting continuity rather than rupture with earlier representations. In this sense, Trillhaase’s work exemplifies how early twentieth-century reinterpretations could intensify the visibility of the female figure while still reproducing the symbolic structures that cast her as morally compromised and socially othered.

However, since the second half of the twentieth century we have witnessed a profound process of re-signification

13. The 1960s, marked by movements of social and political liberation, saw the figure of the witch reclaimed as an emblem of emergent feminism. The famous slogan of the radical collective

W.I.T.C.H. (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell, founded in 1968) encapsulated this shift: the witch ceased to be merely an object of persecution and became a political subject—a banner of resistance and of female empowerment—in line with the work of

Federici (

2019).

In this new horizon, the witch is no longer a passive subject onto whom social fears are projected, but an active, assertive, and intellectual body. Contemporary visual culture echoes this transformation by exploring the figure of the witch as a space of memory, dissidence, and alternative spirituality.

A paradigmatic example is Kiki Smith’s sculpture

Woman on Pyre Kneeling (2002) (

Figure 7), an artist who has consistently worked on the relationship between body, spirituality, and memory. The piece explicitly alludes to women burned at the stake—both within the historical context of the witch hunts and in its archetypal dimension. Yet instead of depicting a defeated body, Smith presents a figure that accepts her fate with defiant serenity. The sculpture does not seek to provoke facile compassion but rather to elicit an uncomfortable reflection on how social and institutional violence has been inscribed upon female bodies (

Posner 2005). In this sense, the body becomes a container of memory, history, and spirituality: the body on the pyre stands not merely as a victim but as a witness to the wounds of history.

Read against the long iconographic tradition in which Endor’s agency is visually neutralized, Smith’s kneeling figure reverses the logic of spectacle: the female body is no longer a readable emblem of transgression for public consumption, but a site of testimony that resists the viewer’s power to classify and condemn.

Read within this horizon, the figure of the Necromancer of Endor acquires renewed strength. Just as Smith’s sculpture summons silenced victims to transform them into witnesses, the nameless woman of 1 Samuel 28 allows us to look beyond the boundaries imposed by official religion and by patriarchal interpretations dominant in exegetical history. As

Trible (

[1984] 2022) proposed in her seminal Texts of Terror, and later Ivone Gebara from Latin American feminist theology (1999), a feminist reading of Scripture entails recovering the silenced voices and attending to the women who inhabit the margins of the biblical narrative. Within this hermeneutical horizon—and from the experiences of women, Afro-descendant peoples, or marginalized communities—this biblical medium may also be understood as a prophetic, mediating, and caregiving figure, a bearer of a spirituality long denied yet persistently alive.

Her final gesture—feeding the fallen king on his last night (1 Sam 28: 21–25)—interrupts, however briefly, the logic of war and power. Against the patriarchal and militaristic narrative culminating in Saul’s death, the biblical story offers the unexpected hospitality of an outcast woman. That gesture, often overlooked in traditional readings, reveals an alternative dimension of revelation: a theology from the margins, from the night, from the excluded bodies. These figures of “terror” in official discourse may become sources of hope and subversion when read from below and through other hermeneutical keys.

Traditional interpretations that brand the woman of Endor as fraudulent or demonic reveal more about institutional fears than about the truth of the text. Recognizing her as a legitimate mediator means challenging the systems that determine who can and cannot speak with God. In this sense, her figure approximates what Ivone Gebara and other Latin American theologians have described as a spirituality of resistance: a mode of knowing that arises from the lived experiences of women and marginalized communities, offering a liberating reading in the face of oppression (

Gebara 1999). The Woman of Endor does not act from deceit, but from compassion. She does not represent chaos, but an alternative order—one grounded in care, in the bond with the dead, in the listening to a divine voice that escapes institutional control.

The contemporary resurgence of the witch myth and its reformulation as a figure of resistance ultimately allows for a rereading of the woman of Endor as part of this broader genealogy. Her memory embodies the persistence of forms of knowledge and spirituality that, though persecuted, remain alive within our communities—caring until the end, resisting oblivion, breaking the boundaries between the sacred and the profane.

7. Epilogue

Read through historical–theological, artistic, and gendered lenses, the figure of the Necromancer of Endor reveals how the margins of the biblical tradition can become sites of symbolic resistance and alternative spirituality. Far from being an anecdotal episode within the narrative of 1 Samuel 28, this nameless woman embodies a constitutive tension in Western culture: the dispute over who may mediate between the human and the divine, who holds legitimacy to transmit the sacred, and who is condemned to silence or suspicion.

The historical and artistic trajectory traced in these pages has shown that the construction of the witch in the West is neither an isolated nor a late phenomenon, but one deeply rooted in a web of ancient genealogies, reinforced by patristic discourse and consolidated within late medieval and early modern iconography. This background allows us to situate the Necromancer of Endor in a pivotal position: not merely as a precursor to the demonized witch, but as a counter-figure that resists absolute categorization. In her ambiguity, she opens a liminal space where the forbidden and the sacred coexist, challenging the boundaries imposed by religious institutions.

The visual representations of this episode attest to the aesthetic power of the spectral. In them, the woman of Endor appears as an embodied threshold, a mediator between the living and the dead, between a fallen king and a reawakened prophet, between patriarchal order and the irruption of the feminine as a locus of power. Images of witches condense the fears and desires of societies in crisis, and for that very reason their persistence in art and collective imagination remains profoundly significant. Across the images analyzed here, this negotiation is not only thematic but formally encoded: who is made visible, whose face is withheld, how the viewer’s gaze is aligned with male witnesses, and where the scene locates ritual efficacy, all determine whether Endor reads as authority or as threat. The “witch” that emerges from these works is therefore not a stable figure but a historical construct—recast from period to period in accordance with shifting anxieties about gender, spiritual power, and religious boundaries.

The contemporary resurgence of the witch as a feminist and spiritual emblem reinforces this intuition. Artists such as Kiki Smith have reinterpreted the memory of the witch hunts and the violence inscribed on women’s bodies, resignifying them as spaces of testimony, resistance, and wisdom. This shift converges with the work of feminist and postcolonial theologies that have insisted on the need to listen to silenced voices and to recognize the margins as legitimate sources of revelation. Within this horizon, the woman of Endor may be read as a symbolic matrix for alternative spiritualities—not fraudulent or demonic, but mediating, nurturing, and bearer of subversive knowledge.

The aesthetics of the spectral, present in the biblical account and in its multiple artistic reinterpretations, reveal more than a fascination with the supernatural: they expose a cultural anxiety to control access to spiritual power. The mediator of Endor, however, demonstrates that mediation does not belong exclusively to institutions or official prophets. In her marginality, she makes visible the voice of the dead, feeds the fallen king, and offers, for an instant, a theology of care in the face of a theology of power.

In conclusion, the Necromancer of Endor constitutes a liminal figure whose symbolic force traverses centuries of religion, art, and politics. Her image challenges the rigid opposition between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, between the sacred and the profane, showing that religious experience can also emerge from what has been excluded. To recognize her place in the visual and spiritual history of the West is not only to reread the past, but also to imagine futures in which mediation, care, and the wisdom of the margins regain their legitimacy, no longer veiled by the regimes of visibility that once converted female dissent into an icon of fear. Like a shadow rising from the earth, the woman of Endor continues to speak to us—not as a ghost of fear, but as a figure of memory, resistance, and hope.