Spiritual Aspirations of American College Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Pervasiveness of Spirituality

1.1.1. Family and Spirituality

1.1.2. Friends and Spirituality

1.1.3. Academics and Spirituality

1.2. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Measures and Procedures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ariff, Nor Balqis Binti, and Ratna Roshida Ab Razak. 2022. Influence of spirituality and prosocial behaviour on psychosocial functioning among international students the midst of COVID-19. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 12: 139–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astin, Alexander W., Helen S. Astin, and Jennifer A. Lindholm. 2010. Cultivating the Spirit: How College Can Enhance Students’ Inner Lives. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, Cezimar Correia, Patrícia Roberta dos Santos, Polissandro Mortoza Alves, Renata Custódio Maciel Borges, Giancarlo Lucchetti, Maria Alves Barbosa, Celmo Celeno Porto, and Marcos Rassi Fernandes. 2021. Association between spirituality/religiousness and quality of life among healthy adults: A systematic review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 19: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burchett, Matthew, and Perry Glanzer. 2020. How student affairs education limits spiritual, religious, and secular identity exploration: A qualitative study of graduate students’ educational experiences. Journal of College and Character 21: 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, Rajasekhar, Sharda Singh, Neuza Ribeiro, and Daniel Roque Gomes. 2022. Does spirituality influence happiness and academic performance? Religions 13: 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito Sena, Marina Aline, Rodolfo Furlan Damiano, Giancarlo Lucchetti, and Mario Fernando Prieto Peres. 2021. Defining spirituality in healthcare: A systematic review and conceptual framework. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 756080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mamani, Amy Weisman, Stephanie Wasserman, Eugenio Duarte, Vamsi Koneru, and Katiah Llerena. 2010. An examination of subtypes of spirituality and their associations with family cohesion in US college students. Revista Interamericana de Psicología/Interamerican Journal of Psychology 44: 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers, Alethea, Brien S. Kelley, and Lisa Miller. 2011. Parent and peer relationships and relational spirituality in adolescents and young adults. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollahite, David C., and Loren D. Marks. 2019. Positive youth religious and spiritual development: What we have learned from religious families. Religions 10: 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollahite, David C., Loren D. Marks, and Greg J. Wurm. 2019. Generative devotion: A theory of sacred relational care in families of faith. Journal of Family Theory & Review 11: 429–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duche-Pérez, Aleixandre Brian, Cintya Yadira Vera-Revilla, Olger Albino Gutiérrez-Aguilar, Sandra Chicana-Huanca, and Bertha Chicana-Huanca. 2024. Religion and spirituality in university students: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Society, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwonye, Angela U., Nastehakeyf Sheikhomar, and Vy Phung. 2020. Spirituality: A psychological resource for managing academic-related stressors. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 23: 826–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esat, Gulden, Syed Rizvi, Caroline Mousa, Kimberly D. Smoots, Ester Shaw, Chase R. Phillip, Meliza Vasquez, Arifa Habib, Elizabeth Vu, and Bradley H. Smith. 2021. Mindful Ambassador Program: An acceptable and feasible universal intervention for college students. Journal of Yoga & Physiotherapy 8: 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes, Al, and Kelley Dugan. 2021. Spirituality through the lens of students in higher education. Religions 12: 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeson, Jeffrey M., Daniel M. Webber, Moria J. Smoski, Jeffrey G. Brantley, Andrew G. Ekblad, Edward C. Suarez, and Ruth Quillian Wolever. 2011. Changes in spirituality partly explain health-related quality of life outcomes after Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 34: 508–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greeson, Jeffrey M., Moria J. Smoski, Edward C. Suarez, Jeffrey G. Brantley, Andrew G. Ekblad, Thomas R. Lynch, and Ruth Quillian Wolever. 2015. Decreased symptoms of depression after mindfulness-based stress reduction: Potential moderating effects of religiosity, spirituality, trait mindfulness, sex, and age. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 21: 166–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, Caroline. 2020. Existential configurations: A way to conceptualise people’s meaning-making. British Journal of Religious Education 42: 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Todd W., Evonne Edwards, and David C. Wang. 2016. The spiritual development of emerging adults over the college years: A 4-year longitudinal investigation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 8: 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamka, Khusnul Khatimah, Sunariyo, Dian Putriana, and Sudarman. 2025. Social support, self-efficacy and spirituality in reducing academic stress of students in Indonesia. Health Education 125: 535–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Craig E., Emma Anderson-White, Eli S. Gebhardt, Beata Krembuszewski, Kessie Mollenkopf, Jamey Crosby, Susan E. Henderson, Treston Smith, and Adam Frampton. 2024. Daily variation in religious activities, spiritual experiences, alcohol use, and life satisfaction among emerging adults in the USA. Journal of Religion and Health 63: 3580–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higher Education Research Institute. 2005. The Spiritual Life of College Students: A National Study of College Students’ Search for Meaning and Purpose. Available online: https://www.spirituality.ucla.edu/docs/reports/Findings_Summary_Pilot.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imron, Imron, Imam Mawardi, and Ayşenur Şen. 2023. The influence of spirituality on academic engagement through achievement motivation and resilience. International Journal of Islamic Educational Psychology 4: 314–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, Kurt. 1951. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers. Edited by Dorwin Cartwright. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Lima das Chagas, Fernanda Augusta, and Antonio Muñoz-García. 2023. Examining the influence of meaning in life and religion/spirituality on student engagement and learning satisfaction: A comprehensive analysis. Religions 14: 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, Annette, Daniel D. Flint, and James S. McGraw. 2020. Spirituality, religion, and marital/family issues. In Handbook of Spirituality, Religion, and Mental Health. Edited by David H. Rosmarin and Harold G. Koenig. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 159–77. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery-Goodnough, Angelique, and Suzanne J. Gallagher. 2007. Review of research on spiritual and religious formation in higher education. In Proceedings of the Sixth Annual College of Education Research Conference: Urban and International Education Section. Edited by S. M. Nielsen and M. S. Plakhotnik. Ho Chi Minh City: International University, pp. 60–65. Available online: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?params=/context/sferc/article/1261/&path_info=montgomery_1_.gallagher.final_p.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Morris, Jason, Mimi Barnard, Greg Morris, and Julie Williamson. 2010. A qualitative exploration of student spiritual development in a living-learning community. Growth: The Journal of the Association for Christians in Student Development 9: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Niemiec, Christopher P., Richard M. Ryan, and Edward L. Deci. 2009. The path taken: Consequences of attaining intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations in post-college life. Journal of Research in Personality 43: 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandya, Samta P. 2024. College students with high abilities in liberal arts disciplines: Examining the effect of spirituality in bolstering self-regulated learning, affect balance, peer relationships, and well-being. High Ability Studies 35: 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Annette Mahoney, Julie J. Exline, James W. Jones, and Edward P. Shafranske. 2013. Envisioning an integrative paradigm for the psychology of religion and spirituality. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality: Vol. 1. Context, Theory, and Research. Edited by K. I. Pargament. (Editor-in-Chief). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 1999. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research 34: 1189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. 2023. Spirituality Among Americans; Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2023/12/07/spirituality-among-americans/ (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Riley, Allison C. 2018. Soul Sisters and Brothers: Sanctification and Spiritual Intimacy as Predictors of Friendship Quality Between Close Friends in a College Sample. Master’s thesis, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sezer, Ovul, Michael I. Norton, Francesca Gino, and Kathleen D. Vohs. 2016. Family rituals improve the holidays. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 1: 509–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoppa, Tara M. 2017. “Becoming more a part of who I am:“ Experiences of spiritual identity formation among emerging adults at secular universities. Religion & Education 44: 154–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, John William. 2023. Friendship and spiritual learning: Seedbed for synodality. Religions 14: 592. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370455919_Friendship_and_Spiritual_Learning_Seedbed_for_Synodality (accessed on 19 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Tanner, Jennifer Lynn. 2006. Recentering during emerging adulthood: A critical turning point in lifespan human development. In Emerging Adults in America: Coming of Age in the 21st Century. Edited by Jeffery Jensen Arnett and Jennifer Lynn Tanner. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 21–55. [Google Scholar]

| Gender | Missing | ||||||

| Male | Female | Preferred not to disclose | |||||

| 30 (26.55%) | 75 (66.37%) | 1 (0.88%) | 7 (6.19%) | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| European American | African American | American Indian | Asian American | Hispanic/Latino American | Other | ||

| 19 (16.81%) | 12 (10.62%) | 0 | 24 (21.24%) | 50 (44.25%) | 1 (0.88%) | 7 (6.19%) | |

| Religious Affiliation | |||||||

| Christian | Muslim | Buddhism | Hinduism | Other | Prefer not to disclose | No Religion | |

| 58 (51.33%) | 5 (4.42%) | 6 (5.31%) | 3 (2.65%) | 9 7.96% | 5 (4.42%) | 20 (17.70%) | 7 (6.19%) |

| 1. Describe how you would like to experience your spirituality in your relationships with family. |

| 2. Describe how you would like to experience your spirituality with friends. |

| 3. Describe how you would like to experience your spirituality when involved in academic work (lectures and assignments). |

| 4. Describe how you would like to experience your spirituality in general. |

| Questions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

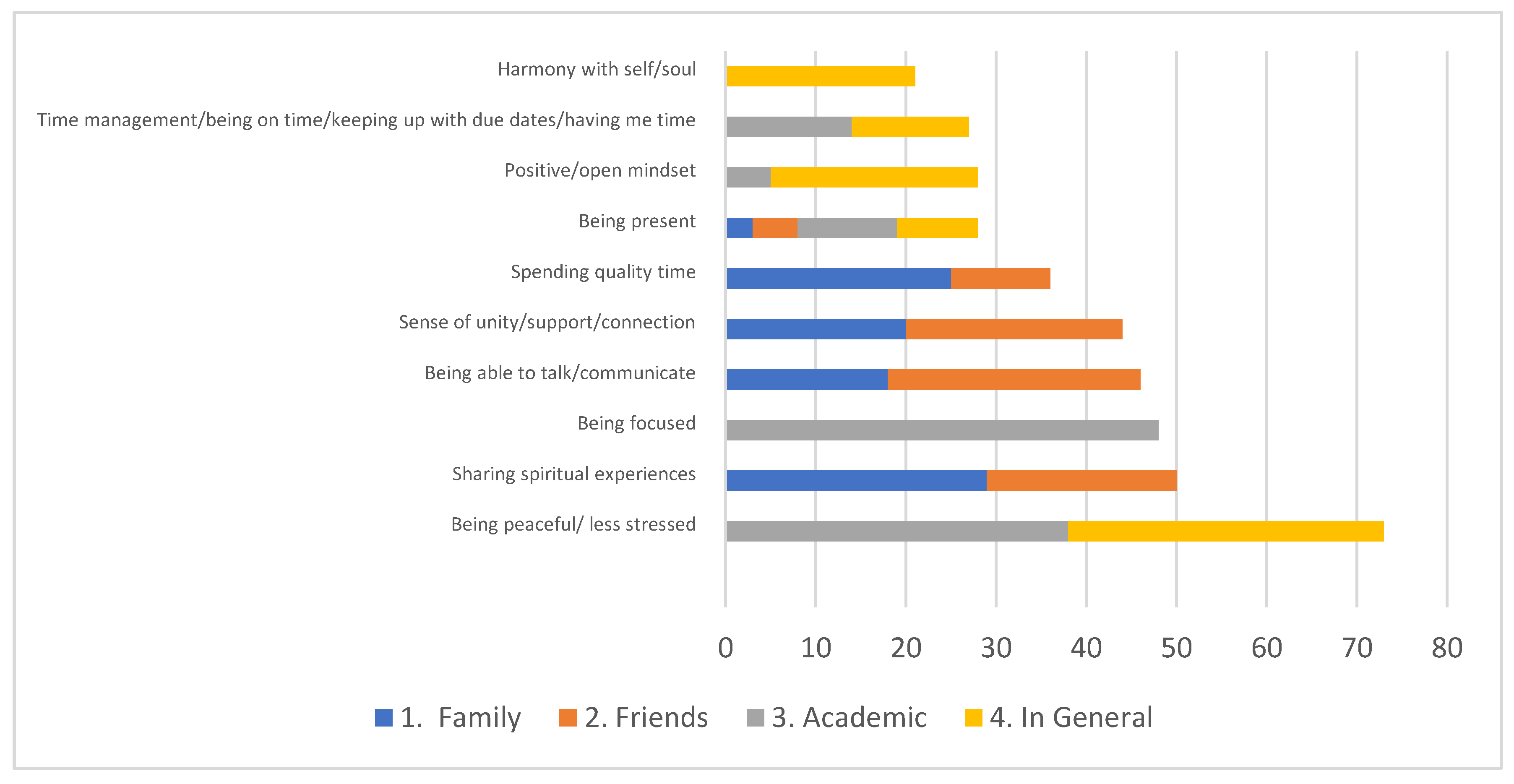

| 1. Family | 2. Friends | 3. Academic | 4. In General | Total Frequency | |

| Being peaceful/ less stressed | 38 | 35 | 73 (66.4%) | ||

| Sharing spiritual experiences | 29 | 21 | 50 (45.5%) | ||

| Being focused | 48 | 48 (43.6%) | |||

| Being able to talk/communicate | 18 | 28 | 46 (41.8%) | ||

| Sense of unity/support/connection | 20 | 24 | 44 (40.0%) | ||

| Spending quality time | 25 | 11 | 36 (32.7%) | ||

| Being present | 3 | 5 | 11 | 9 | 28 (25.5%) |

| Positive/open mindset | 5 | 23 | 28 (25.5%) | ||

| Time management/being on time/keeping up with due dates/having “me time” | 14 | 13 | 27 (24.5%) | ||

| Harmony with self/soul | 21 | 21 (19.1%) | |||

| Being calm and patient in interactions | 9 | 6 | 15 (13.6%) | ||

| Love and care | 11 | 4 | 15 (13.6%) | ||

| Being understanding | 9 | 5 | 14 (12.7%) | ||

| Respectful of differences/nonjudgement | 7 | 7 | 14 (12.7%) | ||

| Experiencing trust | 3 | 9 | 12 (10.9%) | ||

| Better learning/enjoying learning | 11 | 11 (10.0%) | |||

| Being fun and cheerful | 5 | 5 | 10 (9.1%) | ||

| Putting more/best effort in | 9 | 1 | 10 (9.1%) | ||

| Mental and physical health/ happiness | 10 | 10 (9.1%) | |||

| Gratitude | 5 | 2 | 1 | 8 (7.3%) | |

| Motivated/engaged | 8 | 8 (7.3%) | |||

| Live more spiritually/value-oriented | 7 | 7 (6.4%) | |||

| Honesty | 2 | 1 | 3 (2.7%) | ||

| Success | 3 | 3 (2.7%) | |||

| Awareness of purpose | 3 | 3 (2.7%) | |||

| Kindness | 2 | 2 (1.8%) | |||

| Being able to express self | 2 | 2 (1.8%) | |||

| Better organized | 2 | 2 (1.8%) | |||

| God consciousness | 1 | 1 (0.9%) | |||

| Being able to ask for assistance | 1 | 1 (0.9%) | |||

| Understanding expectations | 1 | 1 (0.9%) | |||

| Apply the knowledge learned | 1 | 1 (0.9%) | |||

| Volunteering | 1 | 1 (0.9%) | |||

| Not sure how to answer | 1 | 1 (0.9%) | |||

| Spirituality is not applicable to this area | 2 | 6 | 8 (7.3%) | ||

| Unclear response | 5 | 5 (4.5%) | |||

| Not spiritual | 3 (2.7%) | ||||

| No response | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 | |

| The total percentage of the sample who reported the theme is provided in parentheses. | |||||

| Dimensions of Spirituality | Themes | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Equanimity | Being peaceful/ less stressed | 73 (66.4%) |

| Being present | 28 (25.5%) | |

| Mental and physical health/ happiness | 10 (9.1%) | |

| Gratitude | 8 (7.3%) | |

| Live more spiritually/value-oriented | 7 (6.4%) | |

| God consciousness | 1 (0.9%) | |

| Equanimity—Action Oriented * | Being focused | 48 (43.6%) |

| Time management/being on time/keeping up with due dates/having “me time” | 27 (24.5%) | |

| Better learning/enjoying learning | 11 (10.0%) | |

| Being fun and cheerful | 10 (9.1%) | |

| Putting more/best effort in | 10 (9.1%) | |

| Motivated/engaged | 8 (7.3%) | |

| Success | 3 (2.7%) | |

| Being able to express self | 2 (1.8%) | |

| Better organized | 2 (1.8%) | |

| Apply the knowledge learned | 1 (0.9%) | |

| Spiritual Quest | Harmony with self/soul | 21 (19.1%) |

| Awareness of purpose | 3 (2.7%) | |

| Connection—Reciprocal * | Sharing spiritual experiences | 50 (45.5%) |

| Being able to talk/communicate | 46 (41.8%) | |

| Sense of unity/support/connection | 44 (40.0%) | |

| Spending quality time | 36 (32.7%) | |

| Experiencing trust | 12 (10.9%) | |

| Being able to ask for assistance | 1 (0.9%) | |

| Understanding expectations | 1 (0.9%) | |

| Ethical Engagement | Being calm and patient in interactions | 15 (13.6%) |

| Love and care | 15 (13.6%) | |

| Being understanding | 14 (12.7%) | |

| Honesty | 3 (2.7%) | |

| Kindness | 2 (1.8%) | |

| Ecumenical Worldview | Positive/open mindset | 28 (25.5%) |

| Respectful of differences/nonjudgement | 14 (12.7%) | |

| Charitable Involvement | Volunteering | 1 (0.9%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esat, G.; Enriquez, S.K. Spiritual Aspirations of American College Students. Religions 2025, 16, 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091157

Esat G, Enriquez SK. Spiritual Aspirations of American College Students. Religions. 2025; 16(9):1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091157

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsat, Gulden, and Samantha K. Enriquez. 2025. "Spiritual Aspirations of American College Students" Religions 16, no. 9: 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091157

APA StyleEsat, G., & Enriquez, S. K. (2025). Spiritual Aspirations of American College Students. Religions, 16(9), 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091157